Benchmarking Microbial Genome Assemblers: A Comprehensive Guide to De Novo Tools for Researchers

De novo genome assembly is a critical first step in microbial genomics that significantly impacts downstream applications in drug development and clinical research.

Benchmarking Microbial Genome Assemblers: A Comprehensive Guide to De Novo Tools for Researchers

Abstract

De novo genome assembly is a critical first step in microbial genomics that significantly impacts downstream applications in drug development and clinical research. This comprehensive review systematically evaluates popular long-read assemblers—including Canu, Flye, NECAT, NextDenovo, wtdbg2, and Shasta—based on recent benchmarking studies. We examine their performance across key metrics: contiguity (N50), accuracy, completeness (BUSCO), computational efficiency, and misassembly rates. The analysis reveals that assembler selection and preprocessing strategies jointly determine assembly quality, with progressive error correction tools like NextDenovo and NECAT consistently generating near-complete assemblies, while ultrafast tools like Miniasm and Shasta provide rapid drafts requiring polishing. This guide provides actionable frameworks for selecting optimal assembly pipelines tailored to specific research needs in biomedical applications.

The Evolving Landscape of Microbial Genome Assembly: Technologies and Challenges

The field of microbial genomics has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. De novo genome assembly, the process of reconstructing an organism's genome without a reference sequence, has been particularly affected by this evolution, moving from fragmented drafts to complete, closed genomes [1] [2]. This progression from short-read to long-read sequencing technologies has fundamentally altered assembly strategies, performance expectations, and computational requirements.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate assembly approach has become increasingly complex. This guide provides an objective comparison of assembly performance across sequencing technologies, offering supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform experimental design and tool selection in microbial genomics research.

The Evolution of Sequencing Technologies in Assembly

From Short to Long Reads: A Technological Shift

The journey of sequencing technology began with Sanger sequencing, which produced long reads (up to 1 kb) but was limited by low throughput and high cost [3]. The advent of second-generation sequencing platforms (such as Illumina) brought dramatically reduced costs and increased throughput but at the expense of read length, generating fragments of just hundreds of bases [1] [4]. This short-read paradigm presented significant challenges for de novo assembly, particularly in resolving repetitive regions, often resulting in fragmented draft genomes.

Third-generation sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) circumvented these limitations by greatly increasing read length—producing reads that can span many thousands of bases—thereby providing the potential to resolve complex repeats and generate complete microbial genomes in a single contig [1] [5]. This technological shift necessitated the development of new assembly algorithms specifically designed to handle the distinctive characteristics of these long reads, particularly their higher per-read error rates compared to short-read technologies.

Impact of Read Length on Assembly Completeness

Long-read technologies transformed assembly outcomes by enabling the resolution of repetitive sequences that previously fragmented assemblies. While short reads often cannot uniquely map to repetitive regions longer than the read length, long reads can span entire repeat regions, allowing assemblers to correctly place sequences on either side [6]. This capability is crucial for producing complete bacterial chromosomes and plasmids without gaps [5].

The difference is evident in assembly statistics. Short-read assemblies of microbial genomes often result in dozens to hundreds of contigs, while long-read assemblies frequently achieve complete, circularized chromosomes and plasmids [7] [5]. This completeness has profound implications for downstream analyses, including accurate gene annotation, structural variant detection, and comparative genomics.

Comparison of Assembly Approaches and Performance

Hybrid vs. Non-Hybrid Assembly Strategies

Assembly methodologies have evolved alongside sequencing technologies, resulting in two primary approaches for utilizing long reads:

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine short and long reads to leverage the high accuracy of short reads with the long-range information of long reads [1]. Examples include ALLPATHS-LG, SPAdes, and SSPACE-LongRead. These methods typically use short reads to correct errors in long reads before or during assembly.

- Non-Hybrid Approaches: Rely exclusively on long reads, exploiting their length to resolve repeats and using self-correction algorithms to address their higher error rates [1]. Key implementations include the Hierarchical Genome-Assembly Process (HGAP), PacBio Corrected Reads (PBcR) pipeline via self-correction, Flye, Canu, and Miniasm.

[1] conducted a comprehensive comparison of these strategies, finding that while both can produce high-quality assemblies, non-hybrid approaches offer a simplified workflow requiring only one sequencing library.

Performance Metrics for Assembly Evaluation

Several key metrics are used to evaluate assembly quality:

- N50: The sequence length of the shortest contig at 50% of the total assembly length. Higher N50 values indicate more contiguous assemblies [8].

- NG50: Similar to N50 but uses 50% of the estimated genome size rather than the assembly size, allowing more meaningful comparisons between assemblies [8].

- Completeness: The percentage of a reference genome covered by the assembly, or the proportion of conserved single-copy orthologs identified (using tools like BUSCO) [6].

- Sequence Identity: The percentage of base matches between the assembly and a reference sequence after alignment [7] [5].

- Structural Accuracy: The correctness of large-scale genomic features, often assessed through circularization of replicons and proper resolution of repeats [7].

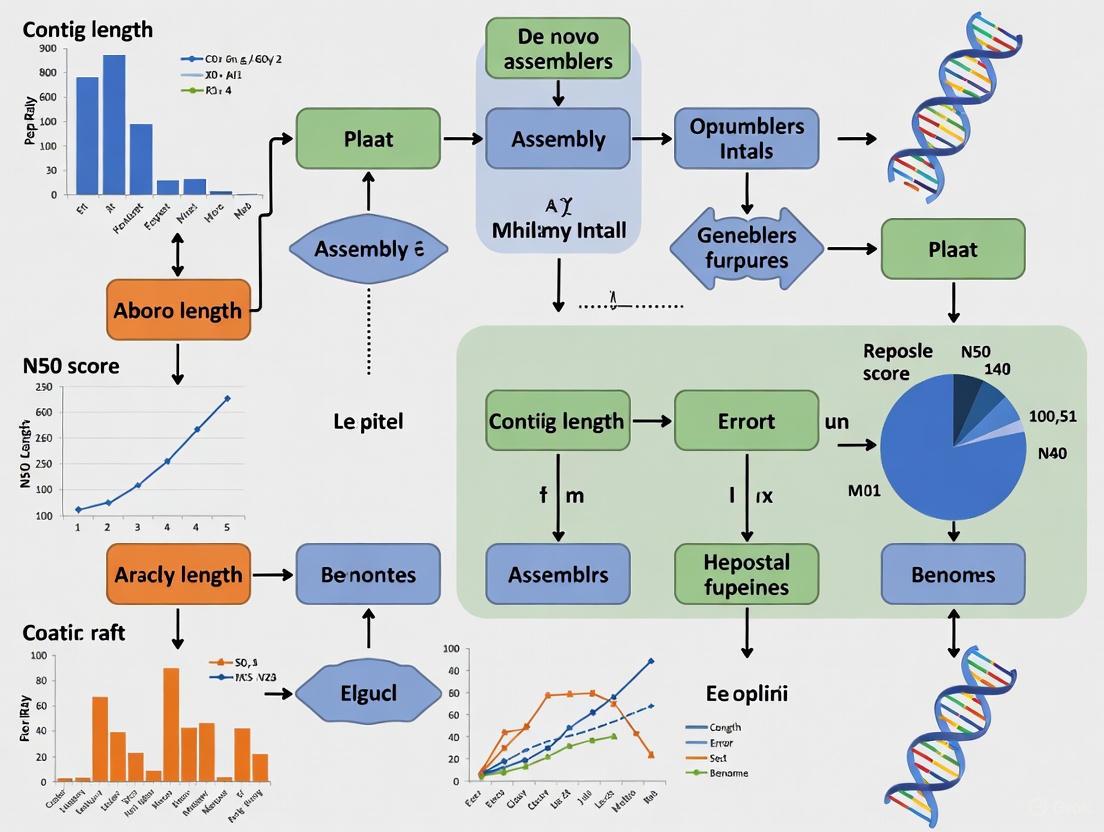

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between sequencing technologies, assembly strategies, and the resulting assembly characteristics:

Quantitative Comparison of Assembler Performance

Recent benchmarking studies provide comprehensive performance data for modern long-read assemblers. [5] evaluated eight long-read assemblers using 500 simulated and 120 real prokaryotic read sets, assessing structural accuracy, sequence identity, contig circularization, and computational resource usage.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Long-Read Assemblers for Prokaryotic Genomes

| Assembler | Structural Accuracy | Sequence Identity | Plasmid Assembly | Contig Circularization | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canu v2.1 | Reliable | High | Good | Poor | Long runtimes |

| Flye v2.8 | Reliable | Highest (smallest errors) | Good | Moderate | High RAM usage |

| Miniasm/Minipolish v0.3/v0.1.3 | Reliable | Moderate | Good | Best | Efficient |

| NECAT v20200803 | Reliable | Moderate (larger errors) | Good | Good | Moderate |

| NextDenovo/NextPolish v2.3.1/v1.3.1 | Reliable for chromosomes | High | Poor | Moderate | Moderate |

| Raven v1.3.0 | Reliable for chromosomes | Moderate | Poor for small plasmids | Issues | Efficient |

| Redbean v2.5 | Less reliable | Moderate | Variable | Variable | Most efficient |

| Shasta v0.7.0 | Less reliable | Moderate | Variable | Variable | Efficient |

[7] provided additional benchmarking of long-read assembly tools, confirming that Flye, Miniasm/Minipolish, and Raven generally performed well across multiple metrics, while noting that Redbean and Shasta offered computational efficiency at the potential cost of completeness.

Table 2: Historical Performance Comparison of Short-Read Assemblers

| Assembler | Algorithm Type | N50 Performance | Assembly Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAdes | De Bruijn graph | Highest at low coverage (<16x) | High | Moderate | Small genomes, low coverage |

| Velvet | De Bruijn graph | High | High | Moderate | General purpose |

| SOAPdenovo2 | De Bruijn graph | Lower | Lower | High (with parallelization) | Large genomes |

| ABySS | De Bruijn graph | Lower | Moderate | High (with parallelization) | Large genomes |

| DISCOVAR | De Bruijn graph | High | High | Moderate | General purpose |

| MaSuRCA | Hybrid | High | High | Moderate | Complex genomes |

| Newbler | OLC | High | High | Moderate | 454 sequencing data |

Data from [9] and [4] indicate that assemblers using the De Bruijn graph approach (like Velvet and SPAdes) generally outperformed greedy extension algorithms (like SSAKE) for short-read data, particularly in terms of computational efficiency and handling of larger genomes.

Experimental Protocols for Assembly Benchmarking

Standardized Assembly Assessment Methodology

To ensure fair and meaningful comparisons between assemblers, researchers should follow standardized benchmarking protocols:

Reference-Based Evaluation Pipeline:

- Read Set Preparation: Obtain or sequence standardized read sets from microbial isolates with known reference genomes.

- Assembly Execution: Run each assembler with optimized parameters, documenting computational resources.

- Quality Assessment: Use tools like QUAST to evaluate assembly contiguity (N50, NG50) and completeness against the reference [9].

- Error Analysis: Assess sequence identity and structural accuracy through alignment to reference genomes.

- Gene Completeness Check: Utilize BUSCO to quantify the presence of universal single-copy orthologs [6].

[5] implemented a rigorous version of this approach, using both simulated and real read sets. For real data, they employed a clever strategy to avoid circular reasoning by using hybrid assemblies (Illumina+ONT and Illumina+PacBio) created with Unicycler as ground truth, only including isolates where both hybrid assemblies were in near-perfect agreement.

Simulation-Based Benchmarking Approach

Simulated read sets provide controlled conditions for evaluating assembler performance across diverse parameters:

Data Simulation Protocol:

- Genome Selection: Curate a diverse set of reference genomes representing different taxonomic groups and genome complexities [5].

- Parameter Variation: Use read simulation tools (e.g., Badread) to generate datasets with varying depth (5x-200x), length (100-20,000 bp), and error profiles [7] [5].

- Assembly Execution: Run all assemblers on identical simulated datasets using standardized computational resources.

- Performance Metric Calculation: Quantify assembly completeness, accuracy, and resource usage relative to known reference.

This approach, utilized by both [7] and [5], allows researchers to systematically test how assemblers perform under specific challenging conditions, such as low coverage, short read length, or high error rates.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in a comprehensive assembly benchmarking experiment:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful genome assembly and benchmarking requires both computational tools and laboratory reagents. The following table details key solutions used in featured experiments:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Long-read Sequencing Kits | Generate long sequencing reads for assembly | PacBio SMRTbell, ONT Ligation Sequencing Kits |

| Short-read Sequencing Kits | Produce high-accuracy short reads | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep, Nextera DNA Flex |

| Assembly Algorithms | Reconstruct genomes from sequence reads | Flye, Canu, SPAdes, Velvet, Unicycler |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Evaluate assembly contiguity and completeness | QUAST, BUSCO, Mercury |

| Read Simulation Software | Generate synthetic datasets for benchmarking | Badread, ART, DWGSIM |

| Alignment Tools | Compare assemblies to reference genomes | Minimap2, MUMmer, BLAST |

| Computational Resources | Provide necessary processing power for assembly | High-performance computing clusters, Cloud computing services |

Based on information from [7] [5] [2], Illumina's PCR-free library preparation methods are particularly recommended for de novo microbial genome assembly as they reduce coverage bias and improve assembly continuity.

The transformation from short-read to long-read sequencing technologies has fundamentally changed genome assembly, enabling complete, closed microbial genomes as a routine outcome rather than an exception. Performance comparisons consistently show that while no single assembler excels across all metrics, tools like Flye, Miniasm/Minipolish, and Canu generally produce reliable long-read assemblies, whereas SPAdes and Velvet remain strong choices for short-read data.

The choice between hybrid and non-hybrid approaches involves trade-offs between accuracy, completeness, and computational demands. For most microbial genomics applications, long-read-only assemblies provide the best balance of completeness and efficiency, while hybrid approaches may be preferable when the highest base-level accuracy is required.

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, with read lengths increasing and error rates decreasing, assembly algorithms will likewise advance. The benchmarking methodologies and performance metrics outlined in this guide provide a framework for researchers to evaluate new tools as they emerge, ensuring optimal assembly strategy selection for specific research goals in microbial genomics.

The accurate reconstruction of microbial genomes from short sequencing reads is a cornerstone of modern genomics, enabling research into pathogenicity, drug resistance, and metabolic pathways. The two predominant computational strategies for this task are the Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) and De Bruijn Graph (DBG) approaches. These methods represent fundamentally different solutions to the complex puzzle of assembling millions of DNA fragments into a complete genomic sequence. The OLC method, which mirrors the original shotgun sequencing approach, employs an intuitive strategy of finding direct overlaps between longer reads [10] [11]. In contrast, the DBG method, developed to handle the massive data volumes of next-generation sequencing, breaks reads into shorter k-mers before assembly [10] [12]. For microbial genomics, the choice between these algorithms significantly impacts assembly accuracy, completeness, and computational efficiency, making a detailed comparison essential for researchers designing sequencing projects.

The historical development of these algorithms reflects evolving sequencing technologies. OLC assemblers like Celera Assembler and Phrap were instrumental in early genome projects using Sanger sequencing [10] [11]. The paradigm shift came with Pevzner's 2001 paper proposing the Euler algorithm, which used a DBG approach to better resolve repetitive regions that challenged OLC assemblers [13]. This innovation paved the way for assemblers like SOAPdenovo, which successfully demonstrated DBG's capability with large genomes using short-read Illumina data [10]. Contemporary assemblers often incorporate hybrid strategies, but the fundamental distinction between OLC and DBG remains relevant for understanding assembly performance in microbial genomics applications.

Algorithmic Foundations and Workflows

Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) Approach

The OLC method follows a logically straightforward three-stage process that mimics the natural approach to solving a jigsaw puzzle. In the initial Overlap phase, all reads are systematically compared against each other to find significant overlaps, typically requiring a minimum overlap length to ensure validity [10] [11] [12]. This all-against-all comparison generates a comprehensive map of how reads connect, which can be computationally intensive for large datasets. The computational burden stems from the need to perform approximate string matching between all read pairs, though strategies like prefix indexing can reduce this complexity.

In the Layout phase, the overlap information constructs a graph structure where nodes represent reads and edges represent overlaps [10]. This overlap graph is then analyzed to determine the most likely arrangement of reads that covers the entire genome. The process involves identifying a path through the graph that incorporates all reads with their overlapping relationships. Finally, the Consensus phase generates the actual genomic sequence by performing a multiple sequence alignment of the reads according to the layout and determining the most likely nucleotide at each position based on the quality scores and agreement of overlapping reads [11] [12]. This step effectively reconciles any discrepancies between reads to produce a final, high-confidence sequence.

De Bruijn Graph (DBG) Approach

The DBG method employs a more abstract mathematical approach that efficiently handles the massive datasets generated by next-generation sequencers. The process begins with K-mer Decomposition, where all reads are broken down into shorter subsequences of length k (k-mers) [10] [11] [12]. The selection of k-value represents a critical parameter balancing sensitivity and specificity—shorter k-mers increase connectivity but exacerbate repeat collapse, while longer k-mers provide better specificity but may fragment the assembly.

Following k-mer decomposition, the Graph Construction phase creates a De Bruijn graph where nodes represent distinct k-mers and directed edges connect k-mers that overlap by k-1 nucleotides [10] [12]. This compact representation efficiently captures all possible sequence relationships without requiring all-against-all read comparisons. The next stage involves Graph Simplification, where computational artifacts and biological complexities are addressed. This includes removing tips (caused by sequencing errors), merging bubbles (resulting from minor variations or heterozygosity), and resolving cycles (caused by repeats) [10] [11].

The final Contig Generation phase identifies paths through the simplified graph where nodes have exactly one incoming and one outgoing edge, indicating unambiguous sequence connections [12]. These paths are then output as contigs—the assembled continuous sequences that represent regions of the genome. The DBG approach effectively transforms the assembly problem from one of read overlap to one of graph traversal, specifically finding Eulerian paths that visit every edge exactly once [10] [14].

Performance Comparison for Microbial Genomes

Table 1: Theoretical and Performance Characteristics of OLC and DBG Assemblers

| Characteristic | Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) | De Bruijn Graph (DBG) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Paradigm | Hamiltonian path problem [13] [10] | Eulerian path problem [13] [10] |

| Computational Complexity | NP-hard [13] | Polynomial-time solvable (theoretical) [13] |

| Optimal Read Type | Long reads (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) [11] [12] | Short reads (Illumina) [10] [11] |

| Memory Usage | High (stores all pairwise overlaps) [12] | Lower (compact k-mer representation) [12] |

| Handling of Sequencing Errors | More robust to errors in long reads [11] | Requires prior error correction or low-frequency k-mer filtering [10] |

| Repeat Resolution | Better with long reads due to spanning capability [11] | Challenging, depends on k-mer size and repeat length [10] |

| Typical Microbial Assemblers | Canu, Falcon, Celera Assembler [11] [14] | SPAdes, Velvet, SOAPdenovo [15] [14] |

Table 2: Experimental Assembly Performance Metrics for Microbial Genomes

| Performance Metric | OLC Assemblers | DBG Assemblers | Implications for Microbial Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contiguity (N50) | Higher with sufficient coverage and read length [11] | Generally lower, depends on k-mer selection and coverage depth [10] | OLC preferred for complete genome finishing; DBG sufficient for draft assemblies |

| Base Accuracy | High in consensus after multiple sequence alignment [11] | High in unique regions, errors in repeats [10] | Both suitable for gene annotation; OLC better for variant calling in repetitive regions |

| Scaffolding Performance | Excellent with long reads spanning repeats [11] | Dependent on mate-pair libraries and mapping [10] | OLC provides more complete chromosomal reconstruction |

| Heterozygosity Handling | Can assemble both alleles separately with sufficient coverage [11] | May collapse heterozygous regions causing consensus errors [11] | DBG may require specialized parameters for heterozygous microbial populations |

| Computational Resources | Memory-intensive, requires high-performance computing for large genomes [12] | More efficient memory usage, suitable for moderate computing resources [12] | DBG more accessible for high-throughput microbial sequencing projects |

The performance comparison between OLC and DBG assemblers reveals a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and assembly completeness. OLC assemblers demonstrate superior performance with long-read technologies, particularly for resolving repetitive regions and generating contiguous assemblies [11]. This advantage stems from the direct use of read length to span repetitive elements, allowing the algorithm to connect unique flanking regions unambiguously. In microbial genomics, this capability is crucial for assembling complete genomes without gaps, especially for organisms with repetitive elements such as CRISPR arrays or insertion sequences.

DBG assemblers excel in computational efficiency when working with high-coverage short-read data [10] [12]. Their k-mer-based approach avoids the memory-intensive all-against-all comparison of OLC, making them practical for large-scale microbial genomics projects. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of repeat resolution, as repeats longer than the k-mer size cause branching in the graph that typically leads to assembly fragmentation [10]. For many microbial applications where draft genomes suffice for gene content analysis or SNP calling, DBG assemblers provide a robust and resource-efficient solution.

The handling of sequencing errors differs substantially between the approaches. OLC assemblers inherently manage errors in long reads through the consensus phase, where multiple overlapping reads average out random errors [11]. DBG assemblers, in contrast, are highly sensitive to sequencing errors which create rare k-mers that branch the graph [10]. Consequently, DBG workflows typically require an explicit error correction step before assembly, using either k-mer frequency thresholds or comparative alignment approaches [10] [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Assembly Evaluation Framework

To objectively compare assembly performance, researchers should implement a standardized evaluation protocol that assesses both computational efficiency and biological accuracy. The recommended methodology begins with Data Preparation: select a well-characterized microbial reference genome (e.g., Escherichia coli K-12) and generate both Illumina short-read and PacBio/Oxford Nanopore long-read datasets [15] [14]. Alternatively, use simulated reads from a known reference to establish ground truth. Include both pure datasets and mixed datasets for hybrid assembly approaches.

The Assembly Execution phase should process the same dataset through multiple representative assemblers: Canu (OLC) and Falcon (OLC) for long reads; SPAdes (DBG) and Velvet (DBG) for short reads; and MaSuRCA (hybrid) for mixed datasets [14]. Use default parameters initially, then optimize based on genome characteristics. Record computational metrics including wall clock time, peak memory usage, and CPU utilization for each assembly.

For Quality Assessment, employ multiple complementary metrics: QUAST for assembly statistics (N50, contig count, largest contig) [15], BUSCO for gene completeness assessment [11], and reference-based alignment with tools like MUMmer for accuracy validation [15]. Additionally, perform taxonomic consistency checks using tools like CheckM for environmental microbes to identify potential contamination.

Hybrid Assembly Protocol for Complex Microbial Genomes

For complex microbial genomes with high repetition or heterozygosity, a hybrid assembly approach often yields superior results. The protocol begins with Data Preprocessing: correct long reads using tools like Canu's built-in correction or LoRDEC [11], and quality-trim short reads using Trimmomatic or FastP. Perform error correction on short reads using BayesHammer or Quake.

The Hybrid Assembly stage can follow multiple strategies: (1) use the long reads to scaffold a DBG assembly from short reads; (2) use corrected long reads for OLC assembly followed by polishing with high-accuracy short reads; or (3) perform a unified hybrid assembly using tools like MaSuRCA or Unicycler [14]. Each strategy offers different trade-offs between contiguity and accuracy.

Finally, conduct Validation and Gap Closing: validate assembly consistency by mapping RNA-Seq data or comparing with optical maps if available [11]. Use long reads to resolve gaps in the assembly, and employ multiple rounds of polishing with different technologies to minimize systematic errors. The final assembly should be evaluated using the same comprehensive metrics as in standardized evaluation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Assembly Experiments

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assembly Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina NovaSeq (short-read), PacBio Sequel II (long-read), Oxford Nanopore PromethION (long-read) [15] | Generate raw sequence data with different read length/accuracy trade-offs |

| OLC Assemblers | Canu, Falcon, Celera Assembler [11] [14] | Perform assembly using overlap-layout-consensus paradigm for long reads |

| DBG Assemblers | SPAdes, Velvet, SOAPdenovo [15] [14] | Perform assembly using de Bruijn graph approach for short reads |

| Hybrid Assemblers | MaSuRCA, Unicycler [14] | Combine short and long reads for improved assembly quality |

| Quality Assessment Tools | QUAST, BUSCO, CheckM [11] [15] | Evaluate assembly contiguity, completeness, and accuracy |

| Data Preprocessing Tools | Trimmomatic (quality control), BFC (error correction), Jellyfish (k-mer analysis) [11] | Prepare raw sequencing data for assembly by removing errors and artifacts |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and computational tools dramatically impacts assembly success. For microbial genomes, SPAdes has emerged as the DBG assembler of choice due to its multi-sized k-mer approach and specialized optimization for bacterial genomes [14]. For OLC assembly of microbial genomes, Canu provides a comprehensive workflow that includes read correction, trimming, and assembly specifically tuned for noisy long reads [14]. The modular nature of these tools enables researchers to mix components from different assemblers, such as using Canu for error correction followed by Falcon for assembly.

Essential quality control reagents include k-mer analysis tools like Jellyfish for initial genome characterization [11], which helps determine optimal k-mer sizes for DBG assemblers and provides estimates of genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content. For assembly evaluation, BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) provides a biological relevance metric by assessing the completeness of essential genes that should be present in a particular taxonomic clade [11]. This is particularly valuable for microbial genomes where expected gene content is well-characterized.

The comparison between OLC and DBG assembly approaches reveals a nuanced landscape where technological progress has blurred historical distinctions. While DBG assemblers demonstrated clear advantages for short-read data in terms of computational efficiency [10] [12], the increasing prevalence of long-read sequencing technologies has driven OLC methods to the forefront for achieving complete, closed microbial genomes [11]. Nevertheless, DBG approaches remain relevant through hybrid strategies that leverage their accuracy in unique regions while using long reads to resolve repeats.

Future developments in assembly algorithms are likely to focus on integrated approaches that transcend the OLC/DBG dichotomy. Graph-based genome representations that preserve variation and uncertainty show particular promise for microbial population studies [15]. As single-cell sequencing and metagenomic applications expand, specialized assemblers that address the unique challenges of these data types will become increasingly important. For researchers conducting microbial genomics studies, the optimal approach involves selecting algorithms matched to both the characteristics of the sequencing data and the biological questions being addressed, with hybrid strategies often providing the most robust solutions for complex genomic landscapes.

De novo genome assembly is a cornerstone of modern genomics, enabling researchers to reconstruct the complete DNA sequence of organisms without a reference. However, despite significant advancements in sequencing technologies and computational methods, microbial genome assembly continues to face substantial challenges. Three persistent obstacles—repetitive regions, sequencing error rates, and coverage bias—routinely compromise assembly quality, leading to fragmented genomes, misassemblies, and incomplete data that hinder downstream biological interpretation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate assembly tool is critical, as the choice directly impacts the reliability of genomic data used in microbial characterization, pathogen surveillance, and therapeutic discovery. This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary de novo assemblers in addressing these challenges, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform your genomic workflows.

Challenge 1: Repetitive Regions and Segmental Duplications

The Assembly Bottleneck

Repetitive regions, including satellite DNA, transposons, and segmental duplications, are primary reasons de novo assemblies become fragmented and incomplete [16]. These regions pose a fundamental challenge because short reads cannot be uniquely placed when repeats exceed read length. Even with modern long-read technologies, highly identical repeats cause assemblers to collapse distinct genomic loci into single sequences. In microbial genomes, such regions can impact the analysis of virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance genes, which are often flanked by repetitive sequences.

Comparative Performance of Assemblers

Specialized tools have emerged to target complex repetitive regions. RAmbler, a reference-guided assembler exclusively using PacBio HiFi reads, employs single-copy k-mers (unikmers) to barcode and cluster reads before assembly [16]. This strategy has proven effective for assembling human centromeric regions, achieving quality comparable to manually curated Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) assemblies. In contrast, general-purpose assemblers like hifiasm, LJA, HiCANU, and Verkko struggle with identical repeats, though they perform adequately for less complex duplication patterns.

Table: Assembler Performance on Complex Repetitive Regions

| Assembler | Strategy | Read Type | Performance on Repeats | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAmbler | Reference-guided, unikmer barcoding | PacBio HiFi | Reconstructs centromeres to T2T quality [16] | Requires a draft reference; specialized for repeats |

| CentroFlye | Uses HORs/monomers | ONT/PacBio CLR | Designed for centromeres [16] | High RAM (~800 GB); requires pre-known repeat units [16] |

| hifiasm | De novo, graph-based | PacBio HiFi, ONT | General-purpose but over-collapses identical repeats [16] | Not specialized for complex repeats |

| Verkko | Hybrid, graph-based | PacBio HiFi, ONT | T2T consortium tool; improves continuity [16] | Can struggle with high-identity segmental duplications |

| SDA | Reference-guided | Various | Previously used for segmental duplications [16] | No longer maintained; outperformed by modern tools [16] |

Challenge 2: Sequencing Error Rates and Assembly Accuracy

Impact on Assembly Fidelity

Sequencing errors—including substitutions, insertions, and deletions—complicate the assembly process by creating branching in assembly graphs, leading to fragmented contigs and misassemblies. The high error rates of early long-read technologies (∼10-15%) presented significant challenges, though the introduction of PacBio HiFi reads (>99.8% accuracy) has markedly improved the situation [16]. The choice of assembly algorithm directly influences how errors are managed during the graph construction and consensus phases.

Hybrid Approaches and Error Correction

Hybrid metagenomic assembly, which leverages both long and short reads, has emerged as a powerful strategy to compensate for the weaknesses of individual technologies [17]. The typical workflow involves assembling long reads to create a contiguous backbone, then iteratively using short reads and error-correction tools to resolve sequencing errors. Studies show that iterative long-read correction followed by short-read polishing substantially improves gene- and genome-centric community compositions, though with diminishing returns beyond a certain number of iterations [17].

Table: Error Handling Across Assembly Strategies

| Assembly Strategy | Typical Workflow | Error Rate Handling | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-read first with polishing | Assemble long reads, then iteratively correct with short reads [17] | Resolves errors effectively; more contiguous output [17] | Microbial isolates; metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) |

| Short-read first with long-read scaffolding | Assemble short reads, then bridge gaps with long reads [17] | High base accuracy but less contiguous assemblies [17] | When accuracy is prioritized over contiguity |

| Pure long-read assembly | Direct assembly of PacBio HiFi or corrected ONT reads | HiFi reads (>99.8% accuracy) minimize need for correction [16] | Isolated microbes with sufficient DNA quality |

| Reference-guided de novo | Map reads to related reference, then de novo assemble partitioned reads [18] | Reduces complexity; improves accuracy for related species [18] | Genomes with available references from related species |

Experimental Protocol: Iterative Hybrid Error Correction

Methodology: [17]

- Long-read Assembly: Begin with long-read assembly using Flye or Miniasm.

- Long-read Correction: Apply long-read specific error correction tools (e.g., Medaka, Racon) using the same long-read dataset.

- Short-read Polishing: Map high-accuracy short reads to the corrected assembly using BWA or Bowtie2, then polish with tools like Pilon.

- Iteration: Repeat long-read correction and short-read polishing (typically 2-10 iterations).

- Quality Assessment: Use reference-free metrics like coding gene content completeness and read recruitment profiles to determine optimal stopping point.

Challenge 3: Coverage Bias and GC Content

Coverage bias in next-generation sequencing refers to the non-uniform distribution of reads across genomes, particularly affecting regions with extreme GC content. This bias primarily originates from library preparation protocols, particularly during PCR amplification steps [19]. In Illumina systems, GC-poor and GC-rich regions frequently exhibit low or no coverage, leading to gaps in assemblies and the potential loss of biologically important loci [20] [19].

Library Preparation Comparisons

Studies comparing library preparation kits reveal important considerations for assembly quality. When comparing Nextera XT and DNA Prep (formerly Nextera Flex) kits for Escherichia coli sequencing, the DNA Prep kit demonstrated reduced coverage bias, though de novo assembly quality, tagmentation bias, and GC content-related bias showed minimal improvement [20]. This suggests that laboratories with established Nextera XT workflows would see limited benefits in transitioning to DNA Prep if studying organisms with neutral GC content.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing GC Bias

Methodology: [19]

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using both traditional (Nextera XT) and bias-reduction (DNA Prep) kits.

- Sequencing: Sequence all libraries on the same Illumina platform with identical parameters.

- Read Mapping: Map resulting reads to a reference genome (e.g., E. coli K12 MG1655) using Bowtie2.

- Coverage Analysis: Calculate coverage at each position using SAMtools and identify regions with consistently low coverage (≤5x).

- GC Correlation: Plot coverage against GC content in sliding windows to quantify bias.

- Assembly Evaluation: Perform de novo assembly with SPAdes and evaluate with QUAST to compare contiguity and completeness metrics.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Assembly Challenges

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Long reads (10-25 kb) with >99.8% accuracy [16] | Resolving repetitive regions; reducing need for error correction |

| Illumina DNA Prep Kit | Library preparation with reduced coverage bias [20] | Sequencing GC-extreme genomes; improving coverage uniformity |

| CHM13/HG002 Cell Lines | Benchmarking standards for assembly validation [16] | Method development and comparative performance testing |

| PDBind+/ESIBank Datasets | Training data for enzyme-substrate prediction [21] | Drug discovery applications following genome assembly |

| Trimmomatic | Quality trimming and adapter removal [18] | Essential read preprocessing before assembly |

| Bowtie2 | Read mapping to reference genomes [20] [18] | Reference-guided approaches; coverage analysis |

| QUAST | Quality assessment of genome assemblies [20] [4] | Comparative evaluation of multiple assembly metrics |

Integrated Comparison: Assembler Performance Across Challenges

Different assemblers employ distinct strategies to overcome the trio of challenges in microbial assembly. The following table synthesizes performance data across multiple studies to provide a comprehensive comparison.

Table: Comprehensive Assembler Performance Across Microbial Assembly Challenges

| Assembler | Repetitive Regions | Error Rate Handling | GC Bias Resilience | Computational Demand | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAmbler | Excellent (uses unikmers) [16] | High (requires HiFi reads) [16] | Not specifically tested | Moderate | Complex repeats in finished genomes |

| hifiasm | Good (general-purpose) [16] | High (optimized for HiFi) [16] | Moderate | Moderate | Standard microbial isolates with HiFi data |

| SPAdes | Moderate | Excellent with hybrid approach [17] | Benefits from uniform coverage | Low to Moderate | Isolates with hybrid sequencing data |

| Velvet | Moderate | Moderate (De Bruijn graph) [4] | Sensitive to coverage variation [19] | Low | Small genomes with uniform coverage |

| SOAPdenovo | Moderate | Lower accuracy (De Bruijn graph) [4] | Similar to other graph-based | Low (but complex configuration) [4] | Large datasets with computational constraints |

| Edena | Good (OLC algorithm) [4] | High for small genomes [4] | Not specifically tested | Low | Small genomes with long reads |

| Reference-guided | Good for related species [18] | Improved by reference constraint [18] | Benefits from reference mapping | Variable | Genomes with close references available |

The ideal assembler for microbial genomics depends heavily on the specific challenges presented by the target genome and available sequencing data. For genomes dominated by complex repetitive regions, RAmbler offers specialized capabilities when a reference is available. For standard isolates sequenced with PacBio HiFi, hifiasm provides robust performance. When dealing with high error rates from long-read technologies, a hybrid approach with iterative correction delivers optimal results. To mitigate GC bias, careful attention to library preparation methods is equally important as algorithm selection. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the development of more sophisticated assemblers that simultaneously address these interconnected challenges will further advance microbial genomics and its applications in drug discovery and therapeutic development.

For researchers in microbial genomics, selecting the optimal de novo assembler is a critical decision that directly impacts the reliability of downstream biological interpretation. While the contiguity metric N50 is often the first number reported, a high-quality genome assembly requires a multi-faceted evaluation. This guide moves beyond a single number to objectively compare assembler performance based on the foundational "3C" principles: Contiguity, Completeness, and Correctness [22] [23]. We summarize quantitative data from systematic evaluations and detail the experimental protocols needed to generate robust, comparable results for microbial genome projects.

Core Concepts in Assembly Quality Assessment

The "3C" Principle: A Framework for Evaluation

A robust genome assembly is built on three interdependent properties:

- Contiguity: Measures how much of the assembly is reconstructed into long, uninterrupted sequences. It is a direct measure of assembly effectiveness and is primarily quantified using Nx statistics and the number of contigs or scaffolds [22].

- Completeness: Assesses whether the entire genomic sequence of the organism is present in the assembly. Methods include flow cytometry, k-mer spectra analysis, and the presence of highly conserved universal genes [22].

- Correctness: Defines the accuracy of each base pair and the larger genomic structures in the assembly. This can be evaluated at the base level through re-sequencing data and at the structural level through reference alignment or long-range data like Hi-C [22] [23].

Demystifying N50 and Related Metrics

The most common contiguity statistics are derived from sorting contigs by length and calculating the cumulative sum of their sizes.

Definition of Key Metrics:

- N50: The sequence length of the shortest contig at 50% of the total assembly length. It is a weighted median statistic such that 50% of the entire assembly is contained in contigs or scaffolds equal to or larger than this value [8].

- L50: The smallest number of contigs whose length sum makes up half of the genome size [8].

- NG50: Analogous to N50, but uses 50% of the estimated genome size as the threshold, allowing for more meaningful comparisons between assemblies of different sizes [8] [24].

- N90: The length for which the collection of all contigs of that length or longer contains at least 90% of the sum of the lengths of all contigs [8].

Table: Summary of Primary Contiguity Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| N50 | Length of the shortest contig at 50% of the assembly length. | Measures contiguity of the generated assembly. | Standard initial assessment. |

| NG50 | Length of the shortest contig at 50% of the estimated genome length. | Allows comparison between assemblies of different sizes. | More fair comparison between projects [8] [24]. |

| L50 | The count of contigs at the N50 point. | A lower L50 indicates a more contiguous assembly. | Complements N50; e.g., L50=1 is a single chromosome [8]. |

| N90 | Length of the shortest contig at 90% of the assembly length. | Describes the "tail" of the length distribution. | Indicates the uniformity of contig sizes. |

A Simple N50 Calculation Example: Consider an assembly with contigs of the following lengths: 80 kbp, 70 kbp, 50 kbp, 40 kbp, 30 kbp, and 20 kbp.

- The total assembly length is 80+70+50+40+30+20 = 290 kbp.

- 50% of the total length is 145 kbp.

- Adding from the largest contig: 80 kbp + 70 kbp = 150 kbp. This value (150 kbp) is greater than 145 kbp.

- The shortest contig in this set that pushes the cumulative sum over the threshold is the 70 kbp contig.

- Therefore, the N50 is 70 kbp, and the L50 is 2 contigs [8].

Experimental Protocols for Assembler Benchmarking

To generate comparable performance data, a standardized benchmarking approach is essential. The following workflow, applied in studies like the one on Haemophilus parasuis [25] and Piroplasm [26], outlines this process.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Assembler Benchmarking. This generic workflow involves sequencing from a single DNA source, assembling with different tools, and systematically evaluating the outputs.

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

The foundation of any assembly is high-quality sequencing data. The benchmark should ideally include data from both short- and long-read technologies.

- DNA Source: For microbial genomes, this is often from cultured colony isolates. Studies show that assemblies from colony isolates show a clearer relationship between N50/L50 metrics and quality compared to those from single-cell amplification methods like MDA, which produce more fragmented assemblies [24].

- Sequencing Platforms:

- Illumina (Short-read): Provides high-accuracy reads (~Q30) with high depth (e.g., 400x). Used for polishing and correctness assessment [25].

- PacBio SMRT (Long-read): Produces long reads (average ~9.6 kb in one study) with a higher raw error rate (~Q15). Excellent for resolving repeats [25].

- ONT (Long-read): Generates very long reads (over 125 kb possible) with a similar raw error rate to PacBio (e.g., ~Q13.2). Library preparation is rapid [25].

- Protocol: As performed in the H. parasuis study, the same genomic DNA sample is sequenced on all platforms to ensure the same genetic origin for a fair comparison [25].

Data Preprocessing

Raw sequencing data must be processed before assembly.

- Long-read Processing: Filter out low-quality reads and contaminants using tools like

NanoFiltandNanoLysefor ONT data [26]. - Short-read Processing: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools like

trim_galoreorTrimmomatic[26].

Assembly and Polishing Strategies

Different assembly strategies can be tested with the same preprocessed data.

- Independent Assembly: Use long-reads only with assemblers like Canu, Flye, or NECAT [25] [26].

- Hybrid Assembly: Use both long and short reads together in assemblers like Unicycler or MaSuRCA to improve accuracy [25].

- Polishing: The critical step of correcting small errors in a long-read assembly. This can be done:

Comparative Performance Data for Microbial Assemblers

Systematic evaluations provide the most reliable data for selecting an assembler. The following tables synthesize results from studies on bacterial and protozoan genomes.

Table: Comparative Assembly Performance of Different Strategies on a Bacterial Genome (H. parasuis) [25]

| Sequencing Platform | Assembler | Contigs | Largest Contig (bp) | N50 (bp) | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | SPAdes | 527 | 157,573 | 40,498 | 39.87 |

| PacBio | Canu | 25 | 2,351,556 | 2,351,556 | 40.01 |

| ONT | Canu | 1 | 2,360,091 | 2,360,091 | 40.02 |

| Illumina + ONT | Unicycler | 1 | 2,349,186 | 2,349,186 | 40.03 |

| Illumina + PacBio | Unicycler | 1 | 2,349,340 | 2,349,340 | 40.03 |

Key Insight: This data clearly shows the transformative impact of long-read technologies on contiguity. While the Illumina-only assembly resulted in hundreds of contigs, long-read assemblies with PacBio or ONT produced nearly complete genomes with N50 values over 2.3 Mbp [25].

Table: Systematic Comparison of ONT Assemblers on a Piroplasm (Babesia) Genome [26]

| Assembler | Number of Contigs | N50 (bp) | Genome Completeness | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NECAT | Information missing | Information missing | Highly contiguous | Designed for Nanopore raw reads. |

| Canu | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Robust but computationally heavy. |

| Flye | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Good for repetitive genomes. |

| wtdbg2 | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Fast assembly. |

| Miniasm | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Very fast but requires polishing. |

| General Trend | Varies dramatically | Varies dramatically | Closely related to correctness | >30x coverage needed; polishing with NGS is crucial. |

Key Insight: The study concluded that coverage depth (recommended >30x) significantly affects genome quality, the level of contiguity varies dramatically among tools, and the correctness of an assembled genome is closely related to its completeness. Polishing with NGS data was identified as a critical step for achieving a high-quality assembly [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

A successful genome assembly project relies on a suite of specialized tools and reagents.

Table: Essential Toolkit for De Novo Genome Assembly and Evaluation

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | High-quality genomic DNA extraction from blood. | Extracting DNA from blood-borne pathogens like Babesia [26]. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit | Library preparation for PacBio long-read sequencing. | Generating long reads for a bacterial genome project [25]. |

| ONT Ligation Kit (SQK-LSK109) | Library preparation for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. | Preparing a library for sequencing on a MinION or PromethION flow cell [26]. |

| Canu | De novo assembler for long reads. | Assembling a microbial genome from PacBio or ONT reads [25] [26]. |

| Unicycler | Hybrid de novo assembler. | Combining the accuracy of Illumina reads with the contiguity of long reads for a polished, complete assembly [25]. |

| QUAST | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. | Evaluating contiguity (N50, etc.) and, with a reference, misassemblies [24] [22]. |

| BUSCO | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs. | Assessing genome completeness by looking for the presence of highly conserved genes [6] [22] [23]. |

| Pilon | Genome polishing tool. | Using Illumina reads to correct small errors (SNPs, indels) in a long-read assembly [25]. |

Moving Beyond N50: A Holistic View of Assembly Quality

While N50 is a useful initial indicator of contiguity, it can be misleading if considered in isolation. A large N50 is not useful if the assembly is incorrect or incomplete [22] [23].

- The Danger of a High N50: It is possible to artificially inflate the N50 by simply removing the shortest contigs from an assembly, but this reduces completeness [8].

- The Importance of BUSCO for Completeness: A BUSCO score assesses the presence of expected universal single-copy genes. A complete score above 95% is generally considered good for a genome assembly [22] [23].

- The Critical Role of Correctness: For downstream analyses like variant calling or gene prediction, accuracy is paramount. Tools like

Merqury(k-mer based) andYakcan measure correctness without a reference genome, whileQUASTcan be used when a reference is available [23].

Selecting the best de novo assembler for a microbial genome is a nuanced decision. The evidence shows that long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio or ONT) are superior to short-reads alone for achieving highly contiguous assemblies, often producing nearly complete genomes in a single contig. For the highest accuracy, polishing a long-read assembly with high-fidelity short reads is an excellent strategy. While assemblers like Canu, Unicycler, and Flye have proven effective in comparative studies, the "best" tool can depend on the specific organism and data type.

Ultimately, a robust assembly is validated by a combination of high contiguity (N50), high completeness (BUSCO >95%), and demonstrated correctness. Researchers should therefore adopt a multi-metric approach grounded in the "3C" principles to ensure their microbial genome assemblies serve as a reliable foundation for future discovery.

The rapid evolution of microbial genomics has fundamentally transformed the landscape of drug development and clinical research. In an era of escalating multidrug resistance (MDR)—responsible for millions of infections and thousands of deaths annually—genomic approaches offer unprecedented opportunities for discovering novel antibacterial agents [27]. The sequencing of the first complete bacterial genome in 1995 marked a pivotal moment, introducing the concept of a "minimal gene set for cellular life" and providing a systematic approach to identifying genes essential for bacterial survival that could serve as potential drug targets [27]. Today, with more than 130,000 complete and near-complete genome sequences available in public databases, researchers can perform comparative genomic studies on an unprecedented scale to identify conserved, essential genes across pathogens—ideal targets for broad-spectrum antibiotic development [27].

Central to this genomic revolution are de novo genome assemblers, computational tools that reconstruct complete microbial genomes from sequencing fragments without reference templates. The performance of these assemblers directly impacts the quality of genomic data used for target identification, yet researchers face significant challenges in selecting appropriate tools given the diversity of sequencing technologies and algorithmic approaches [26] [28]. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of de novo assemblers, presenting experimental benchmarks to inform tool selection for microbial genomics applications in pharmaceutical development and clinical research.

Algorithmic Foundations of Genome Assembly

Genome assembly represents a computational process of reconstructing chromosomal sequences from smaller DNA segments (reads) generated by sequencing instruments [28]. Various algorithmic paradigms have been developed to address this complex task, each with distinct strengths and limitations relevant to microbial genomics research.

Primary Assembly Algorithms

Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC): This three-stage approach begins with calculating pairwise overlaps between all reads, constructs an overlap graph where nodes represent reads and edges denote overlaps, then identifies paths through this graph to generate genome sequences [28]. OLC excels with long-read technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) where high error rates preclude other methods, though computational demands increase significantly with dataset size [29] [28].

De Bruijn Graph (DBG): This approach fragments reads into shorter k-mers (substrings of length k), then constructs a graph where edges represent k-mers and nodes represent overlaps of length k-1 [28]. Assembly reduces to finding an Eulerian path through this graph. DBG implementations are computationally efficient for large datasets but sensitive to sequencing errors that introduce false k-mers [28]. They perform optimally with high-coverage, high-accuracy data from platforms like Illumina [28].

Greedy Extension: This intuitive method iteratively joins reads or contigs starting with best overlaps, continuing until no more merges are possible [28]. While simple to implement, this approach makes locally optimal choices that may not yield globally optimal assemblies, particularly in repetitive regions [28].

Comparative Assembly Approaches

Comparative or reference-guided assembly leverages previously sequenced genomes to assist reconstruction [28]. Reads are aligned against a reference genome, followed by consensus sequence generation. This approach excels at resolving repeats and achieves better results at low coverage depths, but effectiveness depends on availability of closely related reference sequences [28]. Significant divergence between target and reference genomes can introduce errors or fragmented assemblies [28].

Figure 1: Microbial Genome Assembly Workflow: From sample collection to downstream analysis for drug target identification, highlighting key decision points for sequencing technologies and assembly algorithms.

Benchmarking De Novo Assemblers for Microbial Genomes

Performance Evaluation of Short-Read Assemblers

Illumina short-read sequencing remains widely used in microbial genomics due to its high accuracy and cost-effectiveness. A comprehensive 2017 evaluation of nine popular de novo assemblers on seven different microbial genomes revealed significant performance differences under various coverage conditions (7×, 25×, and 100×) [30].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Short-Read Assemblers on Microbial Genomes

| Assembler | Algorithm Type | Best Coverage | NGA50 | Accuracy | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAdes | De Bruijn Graph | All coverages (7×, 25×, 100×) | Highest | High | Outstanding across all coverage depths [30] |

| IDBA-UD | De Bruijn Graph | All coverages (7×, 25×, 100×) | High | High | Excellent performance matching SPAdes [30] |

| Velvet | De Bruijn Graph | All coverages | Lowest | Lowest error rate | Most conservative, lowest NGA50 [30] |

The study demonstrated that assembler performance on real datasets often differs significantly from simulated data, primarily due to coverage bias in actual sequencing runs [30]. This highlights the importance of using biologically relevant datasets rather than idealized simulations when benchmarking tools for research applications.

Long-Read Assembler Performance Assessment

Long-read technologies from Oxford Nanopore and PacBio have revolutionized genome assembly by spanning repetitive regions that challenge short-read approaches. A systematic evaluation of nine long-read assemblers on Babesia parasites (phylum Piroplasm) with varying coverage depths (15× to 120×) revealed several critical considerations [26]:

- Coverage depth significantly impacts genome quality, with most assemblers requiring ≥30× coverage for reasonably complete genomes [26]

- Contiguity varies dramatically between different de novo tools despite similar input data [26]

- Assembly correctness correlates with completeness—higher quality assemblies typically achieve better genomic coverage [26]

- Polishing with NGS data substantially improves assembly quality for Nanopore-generated assemblies [26]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Long-Read Assemblers for Microbial Genomes

| Assembler | Algorithm | Optimal Coverage | Contiguity | Completeness | Accuracy | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flye | Bruijn Graph | 70×-100× | High | High | High with polishing | Moderate [31] [26] |

| NECAT | OLC-based | 50×-100× | High | High | High | Fast [26] |

| Canu | OLC-based | 70×-100× | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Memory intensive [26] |

| Miniasm | OLC-based | 50×-70× | Moderate | Moderate | Lower without polishing | Fast, low memory [26] |

| wtdbg2 | OLC-based | 50×-70× | High | High | Moderate | Fast, low memory [26] |

A 2016 benchmarking study specifically evaluating algorithmic frameworks for Nanopore data revealed that OLC-based approaches like Celera significantly outperformed de Bruijn graph and greedy extension methods, generating assemblies with ten times higher N50 values and one-fifth the number of contigs [29]. This established OLC as the preferred algorithmic framework for long-read assembly development.

Hybrid Assembly Approaches for Complete Microbial Genomes

Hybrid approaches combining long-read and short-read technologies have emerged as powerful strategies for completing microbial genomes. These methods leverage the contiguity of long reads with the accuracy of short reads to generate high-quality assemblies [32].

- ALLPATHS-LG: Requires Illumina paired-end reads from two libraries (short fragments and long jumps) combined with PacBio long reads [32]

- PBcR Pipeline: Uses short, high-fidelity reads to correct errors in long reads, increasing accuracy from ~80% to >99.9% before assembly [32]

- SPAdes Hybrid: Incorporates both short and long reads in a unified assembly pipeline [32]

- SSPACE-LongRead: Scaffolds draft assemblies from short reads using PacBio long reads [32]

Non-hybrid approaches using exclusively long reads (HGAP, PBcR self-correction) have also been developed, requiring 80-100× PacBio sequence coverage for effective self-correction without short reads [32]. These approaches simplify library preparation while still generating complete microbial genomes.

Experimental Design for Assembler Benchmarking

Standardized Evaluation Methodologies

Rigorous benchmarking of assembly tools requires standardized experimental designs and evaluation metrics. Based on multiple comprehensive studies, the following methodologies represent best practices for assembler evaluation:

Sequencing Data Preparation: For microbial genome assembly comparisons, researchers typically employ either:

- Mock microbial communities with defined compositions for controlled evaluations [33]

- Reference genomes with publicly available datasets from previous studies [32]

- Clinically derived samples from specific environments (e.g., hematopoietic cell transplantation patients) [34]

Data Processing Workflows: Comparative studies typically implement multiple assemblers on identical datasets using standardized parameters, followed by systematic quality assessment [30] [26]. For example, in long-read assembler evaluation, data is often subsampled to various coverage depths (15×, 30×, 50×, 70×, 100×, 120×) to assess performance across sequencing depths [26].

Quality Assessment Metrics: Comprehensive evaluators employ multiple complementary metrics:

- QUAST: Evaluates contiguity statistics (N50, contig counts) and reference-based quality metrics [31] [32]

- BUSCO: Assesses genomic completeness based on universal single-copy orthologs [31]

- Merqury: Evaluates assembly accuracy using k-mer spectra [31]

- r2cat: Generates dot plots against reference genomes to visualize assembly accuracy [32]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Microbial Genome Assembly

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Assembly Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Generate short-read (Illumina) or long-read (PacBio, Nanopore) data for assembly [26] [28] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QiAMP Stool Mini Kit, Gentra Puregene Yeast/Bacteria Kit | Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from microbial samples [34] |

| Library Preparation | 10X Genomics Gemcode/Chromium, Truseq DNA HT | Prepare sequencing libraries with appropriate fragment sizes for different platforms [34] |

| Assembly Algorithms | SPAdes, Flye, IDBA-UD, Canu, NECAT | Perform de novo genome assembly from sequencing reads [30] [31] [26] |

| Quality Assessment | QUAST, BUSCO, Merqury | Evaluate assembly contiguity, completeness, and accuracy [31] |

| Data Processing | NanoFilt, Trim Galore, Guppy | Filter and preprocess raw sequencing data before assembly [26] |

Figure 2: Algorithm Selection Framework: Decision pathway for selecting appropriate assembly algorithms based on sequencing technology and analytical requirements.

Applications in Clinical Research and Therapeutic Development

Strain-Resolved Analysis for Antimicrobial Resistance Tracking

Microbial genomics has enabled unprecedented resolution in tracking clinically relevant strains in human populations. Read cloud sequencing—a linked-read technology that preserves long-range information—has demonstrated particular utility in resolving strain-level variation within complex microbiomes [34].

In a landmark case study monitoring a hematopoietic cell transplantation patient over a 56-day treatment course, researchers observed dynamic strain dominance shifts in gut microbiota corresponding to antibiotic administration [34]. Through read cloud metagenomic assembly, they identified specific transposon integrations in Bacteroides caccae strains that conferred selective advantages during antibiotic treatment [34]. This strain-resolved approach enabled researchers to:

- Track fluctuating strain abundances over short clinical timescales [34]

- Identify specific genomic variations associated with increased antibiotic resistance [34]

- Validate predictions through in vitro antibiotic susceptibility testing [34]

Such applications demonstrate how advanced assembly methods can reveal evolutionary dynamics in clinical settings, providing insights for managing antibiotic resistance and understanding microbiome responses to therapeutic interventions.

Metatranscriptomic Assembly for Functional Insights

Beyond genomic applications, assembly algorithms play crucial roles in metatranscriptomic studies that characterize gene expression in microbial communities. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that assembly significantly improves annotation of metatranscriptomic reads, with Trinity assembler performing particularly well for this application [35].

Notably, total RNA-Seq approaches have shown advantages over metagenomics for taxonomic identification of active microbial communities, as they:

- Target actively transcribed genes rather than total DNA (including dormant/dead cells) [33]

- Enrich for ribosomal RNA markers (37-71% of reads) versus metagenomics (0.05-1.4%) [33]

- Provide equivalent accuracy at sequencing depths almost one order of magnitude lower [33]

These advantages make metatranscriptomic assembly particularly valuable for clinical ecology studies seeking to identify actively interacting community members rather than total microbial composition.

Genomic Strategies for Novel Antibiotic Discovery

Pharmaceutical companies have developed three primary strategies for leveraging bacterial genomics in antibiotic discovery:

- Target-Based Screening: Genomics identifies essential, conserved bacterial targets absent in humans, enabling rational drug design [27]

- Genomic Structure Screening: Uses three-dimensional protein structures for virtual screening and lead optimization [27]

- Whole-Cell Antibacterial Screening: Tests compounds against live bacteria, then uses genomics to identify mechanisms of action [27]

These approaches have yielded several promising targets including:

- Histidine Kinases (HKs): Critical components of bacterial two-component signal transduction systems [27]

- LpxC: Essential enzyme in lipid A biosynthesis for Gram-negative outer membranes [27]

- FabI: Enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase in bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis [27]

- Peptide Deformylase (PDF): Essential bacterial processing enzyme for protein maturation [27]

- Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases (AaRS): Essential enzymes for protein synthesis [27]

High-quality genome assemblies through appropriate de novo tools provide the foundation for identifying and validating such targets across multiple pathogenic species.

The microbial genomics revolution continues to transform drug development and clinical research, with de novo genome assembly serving as a critical enabling technology. As sequencing technologies evolve and computational methods advance, researchers must remain informed about performance characteristics of available assembly tools to select optimal approaches for specific applications.

Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies, SPAdes and IDBA-UD currently demonstrate superior performance for short-read microbial genome assembly [30], while OLC-based approaches like Flye and NECAT excel with long-read data [31] [26]. For the most complete, reference-quality assemblies, hybrid approaches combining long-read contiguity with short-read accuracy remain the gold standard [32].

Future developments will likely focus on improving assembly accuracy for complex metagenomic samples, enhancing computational efficiency for large-scale studies, and integrating multi-omic data for more comprehensive functional insights. As these tools mature, they will further accelerate the discovery of novel antimicrobial targets and enhance our understanding of microbial dynamics in clinical settings, ultimately supporting more effective therapeutic interventions in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance.

Practical Guide to Major De Novo Assemblers: Performance and Applications

De novo genome assembly is a foundational technique in genomics, enabling the reconstruction of genome sequences without a reference. The advent of third-generation long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio, has dramatically improved the ability to resolve complex and repetitive genomic regions. However, the high error rates inherent in these long reads, particularly from Nanopore platforms, present significant computational challenges. To address this, specialized assemblers employing progressive error correction strategies have been developed. Among these, NextDenovo and NECAT (Nanopore Erroneous reads Correction and Assembly Tool) have emerged as powerful tools designed to efficiently handle the complex error profiles of long-read data. Both implement a "correct-then-assemble" (CTA) strategy, which first corrects errors in the raw reads before performing the assembly, a method known to produce highly continuous and accurate assemblies, especially for complex, repeat-rich genomes [36] [37]. This guide provides an objective comparison of NextDenovo and NECAT, focusing on their performance, methodologies, and optimal use cases to inform researchers in microbial genomics and drug development.

While both NextDenovo and NECAT share the overarching CTA philosophy, their specific algorithmic approaches to error correction and graph construction differ, leading to variations in performance, resource consumption, and output quality. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Profiles of NextDenovo and NECAT

| Feature | NextDenovo | NECAT |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Strategy | "Correct-then-assemble" (CTA) | "Correct-then-assemble" (CTA) with two-stage assembly |

| Primary Correction Algorithm | Kmer Score Chain (KSC) with heuristic Low-Score Region (LSR) handling | Two-step progressive correction (LERS then HERS) with adaptive read selection |

| Handling of Problematic Regions | Identifies LSRs and applies multiple iterations of Partial Order Alignment (POA) and KSC | Uses adaptive selection of supporting reads based on global and individual error rate thresholds |

| Key Innovation | Efficient correction of ultra-long reads while maintaining integrity in repetitive regions | Designed for the broad error distribution of Nanopore reads, avoiding trimming of high-error-rate subsequences |

| Supported Read Types | ONT, PacBio CLR, HiFi (no correction needed for HiFi) [38] [39] | Optimized for Nanopore reads [40] [37] |

NextDenovo's Approach

NextDenovo is designed for high efficiency and accuracy with noisy long reads. Its pipeline begins with overlap detection, followed by filtering of repeat-induced alignments. The core of its correction module, NextCorrect, uses the Kmer Score Chain (KSC) algorithm for an initial rough correction. A key innovation is its heuristic detection of Low-Score Regions (LSRs), which often correspond to repetitive or heterozygous regions. For these LSRs, NextDenovo employs a more accurate hybrid algorithm combining Partial Order Alignment (POA) and KSC, applied over multiple iterations to produce a highly accurate corrected seed. This focused effort on difficult regions allows it to maintain the continuity of ultra-long reads while achieving an accuracy that rivals PacBio HiFi reads [36]. The subsequent assembly module, NextGraph, constructs a string graph and uses a "best overlap graph" algorithm alongside a progressive graph cleaning strategy to simplify complex subgraphs and produce final contigs [36] [39].

NECAT's Approach

NECAT is specifically engineered to overcome the complex and broadly distributed errors in Nanopore reads. Its strategy is built around two core ideas: adaptive read selection and progressive error correction. Unlike tools that use a single global error rate threshold, NECAT employs a dual-threshold system. It uses a global threshold to maintain overall quality and an individual threshold for each read (template read), calculated from the alignment differences of its top candidate supporting reads. This ensures that both low- and high-error-rate reads receive high-quality supporting data [37]. Its progressive correction first corrects Low-Error-Rate Subsequences (LERS) before tackling the High-Error-Rate Subsequences (HERS), preventing the trimming of HERS and thereby preserving read length—a critical advantage for assembly contiguity. Finally, NECAT's two-stage assembler first builds contigs from corrected reads and then bridges gaps using the original raw reads to fully leverage their extreme length [40] [37].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

Independent benchmarks and published studies have evaluated the performance of these assemblers in terms of computational efficiency, assembly continuity, and accuracy. The following tables synthesize quantitative data from these assessments.

Table 2: Computational Resource and Efficiency Comparison

| Metric | NextDenovo | NECAT | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correction Speed (vs. Canu) | 9.51x faster (real data) [36] | 2.5x - 258x faster than other CTA assemblers [37] | Both are significantly faster than Canu; direct comparison varies by dataset. |

| Human Genome Assembly (CPU hours) | Information Missing | ~7,225 CPU hours for a 35X coverage genome [40] [37] | NECAT is efficient for large genomes. |

| Memory Usage | "Requires significantly less computing resources and storages" [38] | Not explicitly quantified, but described as "efficient" [37] | NextDenovo is noted for low resource consumption. |

Table 3: Assembly Quality Output Based on Lepidopteran Insect Study [41]

| Metric (ONT Data) | NextDenovo | NECAT | wtdbg2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Size (Mb) | ~449-468 | Intermediate | Largest |

| Contig Count | 89-114 | Intermediate | Highest |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 10.0-13.8 | Lower than NextDenovo | Lowest |

| BUSCO Completeness | Most Complete | Less Complete than NextDenovo | Least Complete |

| Small-scale Errors | Least | Intermediate | Most |

| Structural Errors | Intermediate | Most | Least |

The data from the Lepidopteran insect study, which serves as a proxy for complex microbial eukaryotes, indicates that NextDenovo produces the most contiguous and complete assemblies (highest N50, lowest contig count, best BUSCO) with the fewest small-scale errors [41]. However, NECAT's strength in preserving full-length reads through its progressive correction can be crucial for projects where maximizing contiguity is the primary goal. Benchmarks on human data showed NECAT achieving an NG50 of 22-29 Mbp [40] [37], demonstrating its power on vertebrate-scale genomes.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear guide for researchers, this section outlines the standard experimental protocols for using NextDenovo and NECAT, based on the methodologies cited in the benchmarks.

NextDenovo Workflow

Title: NextDenovo Experimental Workflow

Protocol Details:

- Input Preparation: Prepare an

input.fofnfile listing the paths to all input read files (supports FASTA, FASTQ, gzipped formats) [39]. - Configuration: Modify a provided

run.cfgfile to set parameters such asseed_cutoff = 10k(optimized for seeds longer than 10kb) and specify computational resources [39]. - Execution: Run the pipeline with the command

nextDenovo run.cfg[39]. - Key Steps:

- Overlap & Filtering: The tool detects all-vs-all read overlaps and filters out those likely caused by repetitive sequences [36].

- Error Correction (NextCorrect): Applies the KSC algorithm. It heuristically identifies LSRs and corrects them using an iterative process that combines POA and KSC to generate high-accuracy corrected seeds [36].

- Assembly (NextGraph): Corrected seeds undergo two rounds of overlapping to find dovetail alignments. A directed string graph is built, followed by transitive edge removal, tip removal, and bubble resolution. A progressive graph cleaning strategy simplifies complex subgraphs [36].

- Output: The final assembly is found in

01_rundir/03.ctg_graph/nd.asm.fasta, with statistics in the corresponding.statfile [39].

NECAT Workflow

Title: NECAT Experimental Workflow

Protocol Details:

- Data Input: Provide a set of Nanopore reads.

- Adaptive Read Selection: For each read to be corrected (template read), NECAT selects 50 candidate supporting reads based on the Distance Difference Factor (DDF) score. It then calculates an individual overlapping-error-rate threshold (average alignment difference minus five times the standard deviation) for each template read [37].

- Progressive Error Correction:

- Two-Stage Assembly: