Benchmarking Multimer Prediction Tools: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions

Accurately predicting the structure of multimeric protein complexes is a cornerstone of modern biology, with profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating drug discovery.

Benchmarking Multimer Prediction Tools: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

Accurately predicting the structure of multimeric protein complexes is a cornerstone of modern biology, with profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating drug discovery. While AI-driven tools like AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 have revolutionized the field, assessing their accuracy and limitations remains a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. This article provides a systematic evaluation of state-of-the-art multimer prediction tools, exploring their foundational principles, methodological applications, and common pitfalls. We synthesize findings from recent benchmarks, including CASP15 and specialized studies on antibody-antigen complexes, to deliver a comparative analysis of predictive performance. Finally, we outline future directions for enhancing accuracy and reliability in biomedical research.

The Multimer Prediction Landscape: From Core Challenges to Key Concepts

Why Multimer Prediction is Inherently More Difficult Than Monomer Prediction

In structural biology, predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins from their amino acid sequence is a fundamental challenge. While the prediction of single-chain monomer structures has seen revolutionary advances, accurately modeling multimer structures—complexes of two or more interacting protein chains—remains a formidable frontier. The ability to predict these complexes is crucial, as most proteins perform their essential functions not in isolation but by interacting to form multimeric assemblies that drive cellular processes such as signal transduction, immune responses, and metabolism [1] [2]. Understanding the inherent difficulties in multimer prediction is therefore vital for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage computational tools for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions.

Although deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 have made remarkable breakthroughs in monomer prediction, accurately capturing inter-chain interaction signals and modeling the structures of protein complexes continues to present significant challenges [1]. This article examines the fundamental reasons behind this performance gap, compares the capabilities of state-of-the-art prediction tools, and details the experimental protocols driving progress in the field.

Fundamental Differences Between Monomer and Multimer Prediction

Data Availability and Problem Complexity

The prediction of protein multimers is fundamentally more complex than monomer prediction due to several interconnected factors, beginning with data availability and the intrinsic complexity of the problem itself.

Limited Experimental Data: As of December 2024, the UniProt database contained 254 million amino acid sequences, while the Protein Data Bank (PDB) had released just over 220,000 protein structures, with approximately 115,000 being structures of protein multimers or complexes [2]. This disparity creates a significant data bottleneck for training and validating multimer-specific prediction tools.

Expanded Prediction Scope: Monomer prediction focuses primarily on the single-chain folding process. In contrast, multimer prediction must accurately model not only the folding of individual monomers but also their assembly state, interaction interfaces, spatial symmetry, and the dynamic behavior of subunits [2]. Success requires optimizing the relative positions of multiple chains to facilitate binding through specific interfaces, forming a stable complex [2].

Conformational Flexibility: The formation of a multimer is frequently accompanied by substantial conformational changes and adaptive adjustments [2]. This inherent flexibility, critical for biological function, presents a major challenge for computational prediction, as it requires modeling dynamic interactions between monomers.

Key Physical and Technical Distinctions

The table below summarizes the core distinctions that make multimer prediction a uniquely challenging computational problem.

Table 1: Core Technical Differences Between Monomer and Multimer Prediction

| Aspect | Monomer Prediction | Multimer Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Folding of a single polypeptide chain into its 3D structure. | Assembly of multiple folded chains into a stable complex. |

| Interactions Modeled | Intra-chain covalent bonds and non-covalent interactions. | Both intra-chain and inter-chain non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) [2]. |

| Evolutionary Signals | Relies on co-evolutionary signals within a single sequence MSA. | Requires paired MSAs to capture inter-chain co-evolution, which is often weak or absent [1]. |

| Conformational Sampling | Sampling the conformational space of one chain. | Sampling the combinatorial space of multiple chains' relative orientations. |

| Quality Assessment | Evaluation of global fold accuracy (e.g., pLDDT). | Must assess both global topology and local interface accuracy [3]. |

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Multimer Prediction Tools

Quantitative Benchmarking on Standardized Datasets

The performance gap between monomer and multimer prediction is clearly demonstrated by benchmarking state-of-the-art tools on standardized datasets like CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction). The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Advanced Multimer Prediction Tools

| Tool | Core Methodology | Reported Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer [1] | Extension of AlphaFold2 tailored for multimers; uses paired MSAs for inter-chain co-evolution. | Baseline performance on CASP15 multimer targets. | Accuracy remains considerably lower than AlphaFold2 for monomers [1]. |

| AlphaFold3 [1] | End-to-end diffusion model for predicting biomolecular complexes. | Outperformed by DeepSCFold on CASP15 targets (10.3% lower TM-score) and antibody-antigen interfaces (12.4% lower success rate) [1]. | Struggles with complexes lacking clear co-evolutionary signals [1]. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | Predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) and interaction probability (pIA-score) from sequence to build enhanced paired MSAs. | Achieves 11.6% and 10.3% higher TM-score than AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 on CASP15, respectively. Improves antibody-antigen interface prediction by 24.7% and 12.4% over the same [1]. | Relies on AlphaFold-Multimer for final structure generation; performance depends on initial monomer MSA quality. |

| AF/EvoDOCK Symmetric Assembly [4] | Combines AlphaFold2/Multimer with all-atom symmetric docking (EvoDOCK) to build large symmetrical complexes. | Successfully assembled 27 cubic systems with a median TM-score of 0.99; 21 systems had high-quality TM-scores >0.9 [4]. | Limited to complexes with symmetry; requires accurate AF/AFM subcomponent prediction as a starting point [4]. |

The Critical Role of Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Processing

A central challenge in multimer prediction is the construction of effective paired Multiple Sequence Alignments (pMSAs). While monomer prediction uses MSAs to capture co-evolution within a single chain, multimer prediction requires pMSAs to identify co-evolving residues across different chains, which provides crucial signals for inter-chain interactions [1].

Standard sequence search tools (e.g., HHblits, Jackhammer) are designed for monomeric MSAs and cannot directly construct pMSAs [1]. This limitation is particularly acute for complexes like antibody-antigen or virus-host systems, which often lack clear inter-chain co-evolution due to the absence of species overlap [1]. Methods like DeepSCFold attempt to overcome this by using deep learning to predict structural complementarity and interaction probability directly from sequence, thereby generating pMSAs based on structural awareness rather than sequence co-evolution alone [1].

Experimental Protocols for Multimer Prediction

The DeepSCFold Protocol for Enhanced Complex Modeling

The DeepSCFold protocol exemplifies a modern, advanced workflow designed to overcome the limitations of existing multimer prediction tools. Its methodology is detailed below.

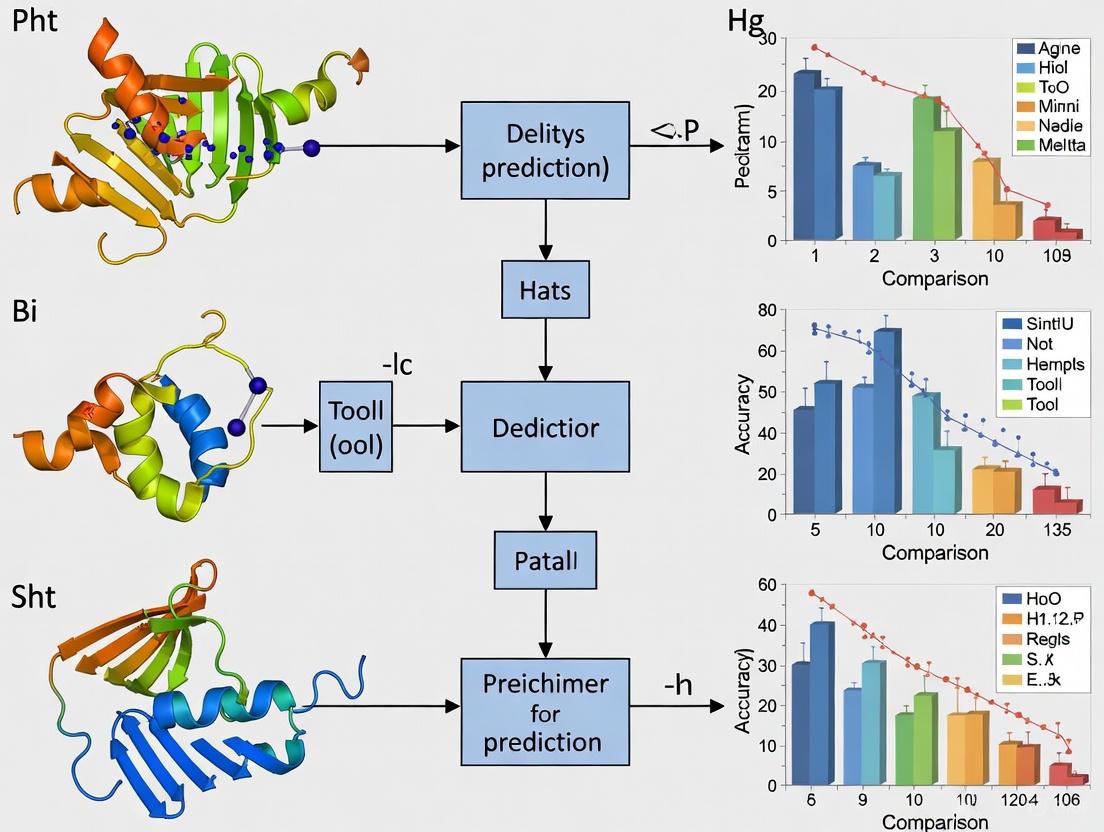

Diagram 1: DeepSCFold Workflow. This workflow integrates deep learning-based structural and interaction predictions to enhance paired MSA construction.

The protocol involves several critical steps:

- Input and Initial MSA Generation: The process begins with the input protein complex sequences. DeepSCFold first generates monomeric Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) for each subunit from multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, MGnify, etc.) [1].

- Deep Learning-Based Feature Prediction: Two key deep learning models are employed. The first predicts a pSS-score, which quantifies the structural similarity between the input sequence and its homologs in the monomeric MSAs. The second predicts a pIA-score, which estimates the interaction probability for pairs of sequence homologs from distinct subunit MSAs [1].

- MSA Processing and Paired MSA Construction: The predicted pSS-score is used as a complementary metric to traditional sequence similarity to rank and filter the monomeric MSAs. Subsequently, the pIA-scores are used to systematically concatenate monomeric homologs from different chains, constructing biologically relevant paired MSAs [1].

- Structure Prediction and Model Selection: The series of constructed paired MSAs are used by AlphaFold-Multimer to generate an ensemble of complex structure models. The top model is selected using an in-house quality assessment method (DeepUMQA-X) and is then used as an input template for a final iteration of AlphaFold-Multimer to produce the output structure [1].

The Symmetric Docking Protocol for Large Assemblies

For large complexes with symmetry, a hybrid approach that combines deep learning and physics-based docking has proven effective. The following diagram illustrates the workflow for predicting the structure of complexes with cubic symmetry.

Diagram 2: Symmetric Assembly Workflow. This protocol combines deep learning-predicted subunits with symmetric docking for large complexes.

This protocol involves three distinct application scenarios:

- Global Assembly: This is a true ab initio prediction from sequence. AF/AFM predicts subcomponent structures (e.g., dimers, trimers), which are then assembled by EvoDOCK without prior structural information, requiring a global search of rigid body parameters [4].

- Local Assembly: This approach uses a starting model (e.g., from Cryo-EM at low resolution) to provide the initial rigid body orientation, but uses AF/AFM-predicted subunit structures. EvoDOCK then refines the model [4].

- Local Recapitulation: Starting from the native assembly model and a bound subunit, this method optimizes rigid-body and side-chain degrees of freedom to characterize the energy landscape and improve model energetics [4].

The symmetric EvoDOCK algorithm uses a memetic algorithm that combines differential evolution with Monte Carlo local search. It optimizes a population of individuals, each defined by a backbone from the ensemble and six rigid-body parameters describing the symmetric assembly. Optimization is guided by the all-atom Rosetta energy function to achieve an energetically favorable final model [4].

Successful multimer prediction relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table catalogs key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multimer Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Multimer Research |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer [1] | Software Tool | End-to-end deep learning model for predicting protein complex structures from sequence. |

| AlphaFold3 [1] [5] | Software Tool | Expands prediction to include protein-ligand and protein-nucleic acid complexes using a diffusion model. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | Software Pipeline | Enhances paired MSA construction using sequence-derived structural complementarity and interaction probability. |

| EvoDOCK [4] | Software Tool | All-atom symmetrical docking algorithm for assembling large complexes from predicted subunits. |

| UniProt [2] | Database | Comprehensive repository of protein sequences and functional information for MSA construction. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] | Database | Archive of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes; essential for training and validation. |

| UniRef30/90 [1] | Database | Clustered sets of protein sequences from UniProt; used for efficient, non-redundant MSA generation. |

| DeepUMQA-X [1] | Software Tool | Complex model quality assessment method for selecting the most accurate predicted structure. |

Multimer prediction remains inherently more challenging than monomer prediction due to a confluence of factors: scarce experimental data, the combinatorial complexity of modeling multiple chains, the dynamic nature of protein interfaces, and the difficulty in capturing weak or absent inter-chain co-evolutionary signals. While innovative tools like DeepSCFold and hybrid AF/docking methods are pushing the boundaries of accuracy—demonstrating significant improvements over baseline AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 on standardized benchmarks—substantial challenges persist. Future research must focus on improving predictions for flexible complexes, transient interactions, and systems lacking evolutionary signals. Overcoming these hurdles will be key to unlocking a deeper understanding of cellular function and accelerating structure-based drug design.

Key Physical and Evolutionary Principles Governing Protein Complex Assembly

Protein complexes are the workhorses of the cell, executing nearly every essential biological process, from signal transduction to metabolism. The precise assembly of these complexes is critical for their function, and alterations in these protein-protein interactions (PPIs) can be a direct cause of disease [6]. Understanding the principles that govern how these complexes form—their assembly pathways—is therefore a fundamental pursuit in structural biology and has profound implications for drug development, as disrupting or stabilizing PPIs is gaining pharmacological relevance [6]. These principles can be broadly categorized into physical constraints, which dictate the spatial and chemical compatibility between interacting subunits, and evolutionary constraints, which are imprinted in the genetic sequences of proteins and revealed through patterns of co-evolution. This article frames these principles within the context of a critical modern challenge: accurately predicting the three-dimensional structures of protein complexes, known as multimer prediction. We will assess the performance of state-of-the-art computational tools, exploring how they leverage these fundamental principles to bridge the gap from amino acid sequence to quaternary structure.

Fundamental Principles of Assembly

The assembly of protein complexes is not a random process but follows a set of definable principles that can be systematically organized and even predicted.

Physical Principles and the "Periodic Table" of Complexes

Structurally, the vast majority of protein complexes adhere to a limited set of quaternary structure topologies. Research has shown that most assembly transitions can be classified into three basic types, which can be used to exhaustively enumerate a large set of possible quaternary structure topologies. This organization enables a natural classification of protein complexes into a conceptual "periodic table," which can accurately predict the expected frequencies of various quaternary structure topologies, including those not yet observed [7]. This framework reveals that complex assembly is governed by a finite set of physical rules concerning symmetry and geometry.

A key physical determinant of assembly is structural complementarity. The three-dimensional shapes of interacting proteins must fit together, much like a lock and key, though often with conformational adjustments in an "induced fit" model [1]. This complementarity is driven by the physicochemical properties of the amino acids at the binding interfaces, involving hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic complementarity. The stability of a complex is a direct result of the sum of these physical interactions across the PBI.

Evolutionary Principles and Co-translational Assembly

From an evolutionary perspective, the sequences of interacting proteins often contain correlated mutations—a phenomenon known as co-evolution. When two residues at a protein-protein interface are physically linked, a mutation in one residue may be compensated by a complementary mutation in its binding partner to preserve the interaction over evolutionary time. These co-evolutionary signals, derived from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of homologous proteins, provide a powerful indirect readout of spatial proximity and are a cornerstone of modern deep learning-based structure prediction tools [8].

Beyond evolutionary history inscribed in sequences, the assembly process itself is mechanistically linked to translation. Recent work demonstrates that co-translational assembly—where a protein subunit begins to interact with its partner while still being synthesized by the ribosome—is a prevalent and governed mechanism. This process is associated with specific structural characteristics of complexes, particularly involving mutually stabilized subunits that are unstable in isolation. Such subunits exhibit synchronized expression and proteostasis with their partner, and the entire process can be predicted using structural signatures, influencing mRNA co-localization and gene expression [9]. This reveals a profound connection between protein structure, complex assembly, and the central dogma of biology.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationships between these fundamental principles and the assembly process.

Experimental Methods for Probing Assembly

While computational predictions are powerful, they require validation and are often informed by experimental data. A key modern method for probing protein complex dynamics is FLiP-MS (serial Ultrafiltration combined with Limited Proteolysis-coupled Mass Spectrometry) [6].

Detailed Protocol: FLiP-MS Workflow

FLiP-MS is a structural proteomics workflow designed to generate a library of peptide markers specific to changes in PPIs by probing differences in protease susceptibility between complex-bound and monomeric forms of proteins.

- Lysate Preparation: A cell lysate is prepared under native conditions to preserve endogenous protein complexes. To account for RNA-binding proteins and RNA-protein complexes, lysates can be incubated with RNases to destabilize RNA-dependent complexes before size separation.

- Serial Ultrafiltration: The native lysate is loaded onto a series of molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) filters for size-based fractionation. A typical protocol sequentially uses 100-kDa, 50-kDa, 30-kDa, and 10-kDa MWCO filters. This results in four fractions enriched for proteins and protein assemblies of progressively decreasing molecular weight.

- Limited Proteolysis (LiP): Each protein fraction is subjected to limited proteolysis using a broad-specificity protease (e.g., Proteinase K). The key is to use a low protease-to-protein ratio and short digestion time so that protease accessibility reflects protein conformation and complex assembly state rather than just sequence.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: The proteolyzed peptides from each fraction are analyzed by quantitative liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). This identifies and quantifies the peptides generated from each fraction.

- Marker Library Generation: Peptides that show significant differences in abundance between the high-MW (complex-bound) and low-MW (monomeric) fractions are identified. These peptides are "PPI markers," as their protease accessibility changes with the assembly state. These markers often map directly to PBIs or to regions undergoing allosteric changes upon complex formation.

- Application to Perturbations: The generated library of PPI markers can be integrated with standard LiP-MS data from cells under different conditions (e.g., drug treatment, disease state). This allows for global profiling of specific PPI changes, rather than all conformational changes, directly from unfractionated lysates at high throughput [6].

The workflow for this key experimental method is detailed below.

The Computational Toolkit for Multimer Prediction

The revolutionary progress in protein monomer structure prediction, led by AlphaFold2, has paved the way for tackling the more formidable challenge of predicting the structures of protein complexes (multimers). Several tools have been developed, each with distinct approaches and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Protein Complex Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Key Input(s) | Strengths | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer [10] | Extension of AlphaFold2, trained on protein complexes. Uses MSA-derived co-evolution. | Single or multiple sequences (for complexes). | Optimized for protein-protein complexes; 'full' AlphaFold algorithm. | Lower accuracy than AF2 on monomers; slow due to exhaustive MSA step [10] [1]. |

| ColabFold [10] | Leverages faster MMseqs2 for MSA generation; built on AlphaFold2/AlphaFold-Multimer. | Single polypeptides or multiple sequences. | 3X-5X faster than AlphaFold2/AlphaFold-Multimer; convenient for single chains and complexes. | Slightly different results from AlphaFold due to different MSA tools [10]. |

| AlphaFold3 [1] | End-to-end deep learning model for biomolecular systems (proteins, nucleic acids, ligands). | Sequences of multiple biomolecules. | Generalist model capable of predicting various interaction types. | In CASP15 benchmark, achieved lower TM-score than DeepSCFold [1]. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | Predicts sequence-derived structural complementarity and interaction probability to build paired MSAs. | Protein complex sequences. | Significantly increases accuracy; effective for targets with weak co-evolution (e.g., antibody-antigen). | Requires construction of complex pMSAs, which can be computationally intensive. |

| OmegaFold [10] | Neural network that operates directly on input sequence, without multiple sequence alignments. | Single amino acid sequence. | Much faster; does not require extensive sequence coverage; handles longer sequences (up to 4096 aa). | For proteins with large sequence coverage, may perform worse than MSA-based tools [10]. |

| IgFold [10] | Specialized deep learning model for antibody structures. | Sequence of antibody Fab region. | Performs better than AlphaFold on predicted Fab structures of antibodies. | Works only on Fab structures, not general protein complexes [10]. |

Performance Benchmarking on Standardized Datasets

Quantitative benchmarking on standardized datasets like those from the CASP competitions provides an objective measure of tool performance. The table below summarizes key metrics from recent evaluations.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarking of Multimer Prediction Tools

| Tool | Test Dataset | Global Structure Metric (TM-score) | Interface Accuracy Metric | Key Comparative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [1] | CASP15 Multimer Targets | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | Achieved an 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | CASP15 Multimer Targets | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | Achieved a 10.3% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold3. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | SAbDab Antibody-Antigen Complexes | N/A | Success Rate for Binding Interface Prediction | Enhanced success rate by 24.7% over AlphaFold-Multimer. |

| DeepSCFold [1] | SAbDab Antibody-Antigen Complexes | N/A | Success Rate for Binding Interface Prediction | Enhanced success rate by 12.4% over AlphaFold3. |

| AlphaFold2 [8] | CASP14 Monomer Targets | Median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (Cα r.m.s.d.) | N/A | Greatly outperformed other methods, establishing new level of accuracy. |

To conduct research in this field, scientists rely on a combination of computational databases, software tools, and experimental resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Complex Studies

| Category | Item / Resource | Function and Utility in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | UniProt [1] | A comprehensive repository of protein sequence and functional information, essential for building multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | The single worldwide archive of experimental 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes; used for training, template-based modeling, and validation. | |

| ColabFold DB [1] | A pre-computed database of MSAs and protein templates, integrated into the ColabFold suite for rapid structure prediction. | |

| Predictomes [11] | A classifier-curated database of over 40,000 AlphaFold-Multimer predictions for human genome maintenance proteins; enables hypothesis generation. | |

| Software & Tools | HHblits/JackHMMER/MMseqs2 [1] | Sensitive sequence search tools used to build multiple sequence alignments from large sequence databases, a critical input for AlphaFold and related tools. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [11] [1] | A widely used deep learning model specifically fine-tuned for predicting structures of protein complexes from sequence. | |

| SPOC Classifier [11] | A machine learning classifier that filters AlphaFold-Multimer predictions to separate true from false positive protein-protein interactions in proteome-wide screens. | |

| Experimental Methods | FLiP-MS [6] | A structural proteomics workflow to generate peptide markers reporting on protein complex assembly states, enabling global profiling of PPI dynamics from lysates. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) [6] | Used to separate protein complexes by their hydrodynamic radius, often coupled with other techniques to analyze complex size and composition. |

The assembly of protein complexes is governed by a finite set of physical and evolutionary principles, including structural complementarity, conserved interaction modes, and co-evolutionary signals. The emergence of deep learning has created a paradigm shift in our ability to predict the structures of these complexes from sequence alone. However, as the quantitative benchmarks show, the accuracy of multimer prediction tools varies significantly. While AlphaFold-Multimer and ColabFold provide robust and accessible platforms, specialized next-generation tools like DeepSCFold demonstrate that moving beyond purely sequence-based co-evolution to incorporate sequence-derived structural complementarity can yield substantial improvements, especially for challenging targets like antibody-antigen complexes. The field is moving towards an integrated future where high-throughput experimental methods like FLiP-MS and computationally curated databases like Predictomes will work in concert with increasingly sophisticated AI models. This synergy will be crucial for achieving a proteome-wide structural understanding of protein complexes, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and our fundamental knowledge of cellular machinery.

Protein complexes represent the fundamental functional units in cellular processes, yet determining their precise three-dimensional structures remains a formidable challenge in structural biology. Experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) face significant limitations when applied to large, dynamic, or transient complexes [1] [12]. This experimental bottleneck has created a substantial data gap, impeding our understanding of critical biological mechanisms and hindering drug discovery efforts.

The emergence of computational prediction tools has revolutionized structural biology by offering alternatives to bridge this gap. This guide provides an objective comparison of modern multimer prediction systems, examining their performance across different complex types, detailing their methodological approaches, and presenting quantitative benchmarking data to inform researchers in structural biology and drug development.

The Experimental Bottleneck in Complex Structure Determination

Experimental structure determination faces inherent limitations that contribute to the current data gap. Protein-protein interactions often involve large, flexible assemblies that resist crystallization, while cryo-EM struggles with complexes exhibiting structural heterogeneity [13]. Additionally, many biologically important complexes such as antibody-antigen systems and virus-host interactions lack clear co-evolutionary signals at the sequence level, making them particularly challenging targets [1]. These limitations have created an imbalance in structural databases, with interfaces involving disordered protein regions being significantly underrepresented [14].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Multimer Prediction Tools

Global and Local Accuracy Metrics

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals significant differences in performance across current multimer prediction tools. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics from recent evaluations:

Table 1: Global Accuracy Metrics for Multimer Prediction Tools

| Prediction Tool | TM-score Improvement | Interface Accuracy | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | +11.6% vs. AF-Multimer, +10.3% vs. AF3 [1] | High (24.7% improvement for antibody-antigen interfaces) [1] | Excels in complexes lacking co-evolution signals |

| AlphaFold3 | Limited global gains over AF2 [15] | Superior for antigen-antibody complexes [15] | Versatile across biomolecular systems |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline for comparisons | Moderate | Established methodology |

| AF_unmasked | High when templates available [13] | High (DockQ >0.8 with templates) [13] | Effective for large complexes (>10k residues) |

Performance Across Complex Types

Different prediction tools exhibit varying strengths depending on the biological context and available input data:

Table 2: Performance Across Complex Types

| Complex Type | Best Performing Tools | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| General Protein Complexes | DeepSCFold, AlphaFold3 [1] [15] | AF3 shows limited global accuracy gains [15] |

| Antibody-Antigen Complexes | DeepSCFold, AlphaFold3 [1] [15] | Both outperform AF-Multimer significantly [1] |

| Peptide-Protein Complexes | AlphaFold3, AlphaFold-Multimer (comparable) [15] | Nearly indistinguishable performance [15] |

| Large Multimeric Assemblies | AF_unmasked [13] | Standard AF struggles beyond 10k residues [13] |

| RNA-Containing Complexes | AlphaFold3 [15] | Superior to RoseTTAFoldNA [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DeepSCFold: Sequence-Derived Structure Complementarity

DeepSCFold introduces a novel approach that leverages structural complementarity information directly from sequence data, rather than relying solely on co-evolutionary signals [1].

DeepSCFold Workflow: Integrating structural similarity and interaction probability predictions

The protocol involves four key stages:

Monomeric MSA Generation: Initial multiple sequence alignments are constructed from diverse databases including UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, and the ColabFold DB [1].

Structural Similarity Prediction: A deep learning model predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) between query sequences and their homologs, enhancing traditional sequence similarity metrics [1].

Interaction Probability Estimation: A separate model predicts interaction probabilities (pIA-scores) for sequence pairs across different subunit MSAs [1].

Paired MSA Construction: pSS-scores and pIA-scores guide the systematic concatenation of monomeric homologs into paired MSAs, incorporating species annotations and known complex data [1].

AF_unmasked: Integrating Experimental Data

AF_unmasked addresses AlphaFold's limitation in utilizing quaternary structural information by modifying template input mechanisms without retraining the neural network [13].

AF_unmasked Workflow: Leveraging quaternary templates for enhanced prediction

Key methodological innovations:

Cross-Chain Template Utilization: Unlike standard AlphaFold, AF_unmasked preserves and utilizes distance constraints across protein chains in templates [13].

Structural Inpainting: The method can fill missing regions in incomplete experimental structures by integrating evolutionary restraints from MSAs [13].

Experimental Integration: Imperfect experimental structures with clashing interfaces or missing components can be used as starting points for refinement [13].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| UniProt [1] | Database | Protein sequence and functional information |

| Protein Data Bank [16] [17] | Database | Experimentally determined structural templates |

| ColabFold DB [1] | Database | Pre-computed multiple sequence alignments |

| CASP Benchmark Sets [1] [13] | Evaluation | Standardized datasets for method validation |

| SAbDab Database [1] | Specialized Database | Antibody-antigen complex structures for benchmarking |

| HHblits/JackHMMER [1] | Software Tool | Multiple sequence alignment construction |

| P2Rank [17] | Software Tool | Binding pocket prediction in multimeric complexes |

| AutoDock Vina [17] | Software Tool | Enzyme-substrate docking validation |

The current landscape of multimer prediction tools demonstrates significant progress in addressing the experimental data gap in structural biology. DeepSCFold excels in scenarios with limited co-evolutionary signals, particularly in antibody-antigen systems, while AF_unmasked provides robust solutions for integrating experimental data and modeling large complexes. AlphaFold3 offers versatility across diverse biomolecular systems but shows limited global accuracy improvements for standard protein complexes.

The choice of tool depends heavily on the specific biological context, with structural complementarity approaches (DeepSCFold) outperforming for challenging interfaces lacking co-evolution, and template-integration methods (AF_unmasked) providing superior results when partial structural information exists. As these tools evolve, their increasing accuracy and specialization promise to further bridge the experimental data gap, enabling researchers to explore previously inaccessible aspects of cellular machinery and accelerating structure-based drug design.

The revolutionary progress in artificial intelligence has dramatically improved our ability to predict the structures of multimeric protein complexes, moving the field's central challenge from structure generation to quality assessment. Accurately evaluating the reliability of predicted complex structures is now paramount for researchers in structural biology and drug development who depend on these models for functional analysis, protein engineering, and therapeutic design [18] [19]. Without known experimental structures for comparison, researchers must rely on confidence metrics generated by the prediction tools themselves, making it crucial to understand their strengths, limitations, and optimal application ranges [18].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of evaluation metrics for protein complex structures, categorizing them into global accuracy measures that assess the overall complex and interface-specific measures that focus on binding regions. We objectively analyze the performance of state-of-the-art prediction tools—including AlphaFold3, DeepSCFold, and ColabFold—using quantitative benchmarking data and detail the experimental protocols that yield these insights. Understanding this evolving landscape of assessment methodologies enables researchers to make informed decisions about which models to trust for specific biological applications.

Categorizing Accuracy Metrics

Global Structure Assessment Metrics

Global metrics provide an overall evaluation of a predicted protein complex's quality. The most established reference-based metric is DockQ, which combines interface quality, model completeness, and structural accuracy into a single score ranging from 0 to 1 [18] [20]. DockQ scores correlate with CAPRI (Critical Assessment of Prediction of Interactions) quality categories: incorrect (DockQ < 0.23), acceptable (0.23-0.49), medium (0.49-0.8), and high quality (> 0.8) [18].

In the absence of a known reference structure, predicted metrics are essential. The predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) measures per-residue local confidence on a scale from 0-100, with higher values indicating greater reliability [18]. The predicted Template Modeling Score (pTM) estimates the global fold quality, while the interface pTM (ipTM) specifically assesses the interaction interface by calculating a weighted combination of pTM and interface alignment scores [18]. The Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) represents a model's confidence in the relative positions of residue pairs, with lower error values indicating higher confidence [21].

Table 1: Key Global Assessment Metrics for Protein Complex Structures

| Metric | Type | Scale | Optimal Range | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DockQ | Reference-based | 0-1 | > 0.8 (High quality) | Overall complex quality assessment |

| pLDDT | Predicted | 0-100 | > 80 (High confidence) | Per-residue local structure confidence |

| pTM | Predicted | 0-1 | > 0.8 (High quality) | Global fold quality |

| ipTM | Predicted | 0-1 | > 0.8 (High quality) | Interface region quality |

| PAE | Predicted | Ångström | Lower values better | Relative residue position confidence |

Interface-Specific Assessment Metrics

Interface-specific metrics focus exclusively on the binding regions between chains, which are critical for understanding biological function. The interface pLDDT (ipLDDT) calculates the average pLDDT specifically for residues located at the protein-protein interface, providing a localized confidence measure [18]. The interface PAE (iPAE) examines the PAE matrix specifically between interacting chains rather than within them, highlighting confidence in relative chain positioning [18].

Several specialized interface scores have been developed specifically for complex assessment. The predicted DockQ (pDockQ) estimates the true DockQ score by considering the number of interfacial contacts and the average pLDDT of interacting residues [18]. Its successor, pDockQ2, was specifically optimized for multimeric protein complexes [18]. VoroIF-GNN utilizes graph neural networks and Voronoi tessellation to create interface graphs, generating contact-based accuracy estimates for entire interfaces [18].

Table 2: Specialized Interface Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Basis | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ipLDDT | Average pLDDT at interface residues | Easy to calculate, intuitive | Does not capture inter-chain geometry |

| iPAE | PAE between different chains | Directly assesses inter-chain confidence | Requires parsing complex matrix output |

| pDockQ2 | Number of contacts + residue quality | Specifically designed for multimers | May overestimate quality in some cases |

| VoroIF-GNN | Voronoi tessellation + GNN | Detailed, contact-based interface estimate | Computationally intensive |

Benchmarking Prediction Tools

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Tools

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies have quantitatively compared the performance of major protein complex prediction tools. A 2025 analysis of 223 heterodimeric complexes revealed significant differences in performance across methods when assessed using DockQ quality thresholds [18].

AlphaFold3 achieved the highest percentage of high-quality predictions at 39.8%, with the lowest rate of incorrect models (19.2%) [18]. ColabFold with templates performed similarly to AlphaFold3, producing 35.2% high-quality models [18]. In contrast, ColabFold without templates generated the lowest proportion of high-quality models (28.9%) and the highest percentage of incorrect models (32.3%) [18]. These results demonstrate that both the choice of prediction tool and the use of template information significantly impact output quality.

The recently developed DeepSCFold pipeline shows particular promise, demonstrating significant improvements over existing methods in CASP15 benchmarks. DeepSCFold achieved improvements of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [1]. For challenging antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, DeepSCFold enhanced the prediction success rate for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [1].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Protein Complex Prediction Tools

| Prediction Tool | High Quality Models | Medium Quality Models | Incorrect Models | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 | 39.8% | 41.0% | 19.2% | General biomolecular complexes |

| ColabFold (with templates) | 35.2% | 34.7% | 30.1% | Protein-protein complexes |

| ColabFold (without templates) | 28.9% | 38.8% | 32.3% | Template-free modeling |

| DeepSCFold | N/A | N/A | N/A | Antibody-antigen complexes |

Integrated Approaches and Specialized Applications

For particularly challenging targets, integrated approaches that combine deep learning with physics-based methods have shown enhanced success. The AlphaRED (AlphaFold-initiated Replica Exchange Docking) pipeline integrates AlphaFold with RosettaDock and replica exchange sampling to address cases involving significant conformational changes upon binding [20]. This hybrid approach successfully docks failed AlphaFold predictions, achieving CAPRI acceptable-quality or better predictions for 63% of benchmark targets where AlphaFold-Multimer alone failed [20]. Particularly impressive is its performance on challenging antigen-antibody complexes, where it demonstrated a 43% success rate compared to AlphaFold-Multimer's 20% [20].

For non-standard molecular interactions, specialized assessments reveal important limitations. In evaluating protein-carbohydrate complexes using the novel BCAPIN benchmark, current AI models achieved approximately 85% acceptable accuracy but showed declining predictive power with increasing carbohydrate polymer length [22]. This highlights the need for continued method development for specific interaction classes relevant to immunology and drug design.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

Robust evaluation of prediction tools requires standardized benchmarking protocols. A typical methodology begins with curating high-quality experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), focusing on heterodimeric complexes solved by X-ray crystallography at high resolution [18]. The benchmark set should exclude homodimers where AlphaFold2 generally performs better, instead focusing on more challenging heterocomplexes [18].

For each prediction tool, multiple models per target (typically five) should be generated using consistent hardware and software configurations [18]. ColabFold predictions generally employ three recycles followed by energy minimization [18]. All predictions should be performed using sequence databases available up to a specific cutoff date to ensure temporal validity and prevent data leakage [1].

The quality assessment pipeline should calculate both reference-based metrics (DockQ against experimental structures) and predicted metrics (pLDDT, pTM, ipTM, PAE, pDockQ2, VoroIF) for each model [18]. Results are then aggregated across the benchmark set to determine the percentage of models in each quality category and calculate statistical significance of performance differences.

Benchmarking Workflow for Prediction Tools

Advanced Integrated Protocols

For hybrid approaches like AlphaRED, the experimental protocol involves additional steps. First, AlphaFold confidence measures (particularly pLDDT) are repurposed to estimate protein flexibility and docking accuracy [20]. These metrics are then incorporated into the ReplicaDock 2.0 protocol, which performs replica exchange docking to extensively sample conformational space [20].

The process involves generating structural templates using AlphaFold, then applying physics-based refinement with RosettaDock to improve interface geometry [20]. This integrated protocol leverages both evolutionary information from deep learning and physicochemical realism from molecular mechanics, demonstrating that combined approaches can overcome limitations of purely AI-based methods, especially for flexible binding partners.

Table 4: Key Research Resources for Protein Complex Prediction and Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold3, DeepSCFold, ColabFold | Generate protein complex models | Web servers/Open source |

| Quality Assessment | pDockQ2, VoroIF-GNN, ipTM | Evaluate model accuracy without reference | Integrated/Standalone |

| Visualization & Analysis | ChimeraX, PICKLUSTER v.2.0 | Interactive model inspection and scoring | Open source plugins |

| Benchmark Datasets | BCAPIN, CASP targets | Standardized performance testing | Public repositories |

| Reference Metrics | DockQ | Ground truth quality assessment | Open source code |

Based on current benchmarking evidence, we recommend:

For general protein complex prediction, AlphaFold3 provides the highest overall accuracy, particularly for structures with standard binding motifs. Its integrated confidence measures (pLDDT, PAE) offer reliable guidance for model selection [21] [18].

For challenging antibody-antigen complexes or cases with limited co-evolutionary signals, DeepSCFold demonstrates superior performance by leveraging structural complementarity rather than relying solely on sequence co-evolution [1].

For complexes involving significant conformational changes, integrated approaches like AlphaRED that combine deep learning with physics-based sampling outperform purely AI-based methods [20].

When assessing model quality, interface-specific scores (ipTM, pDockQ2) provide more reliable evaluation of biological relevance than global scores alone [18]. For the most comprehensive assessment, researchers should consult multiple complementary metrics rather than relying on a single score.

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing developments in assessing diverse molecular interactions including carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and small molecules [22] [19]. As these methodologies mature, standardized assessment protocols and specialized benchmarks will remain essential for objectively measuring progress and guiding researchers toward the most appropriate tools for their specific applications.

A Deep Dive into State-of-the-Art Tools and Their Practical Use

The accurate prediction of multimeric protein complexes is crucial for advancing our understanding of cellular functions and for rational drug design. Within this research context, DeepMind's AlphaFold suite has emerged as a transformative tool. This guide provides a detailed objective comparison of two key iterations: AlphaFold-Multimer, an extension of AlphaFold2 specifically designed for protein-protein complexes, and AlphaFold3, a general-purpose model for predicting structures of complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, and more. We will dissect their architectures, inputs, outputs, and performance, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of assessing the accuracy of multimer prediction tools.

The architectures of AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 represent significant evolutionary stages in deep learning for structural biology. The core differences are visualized in the schematic below.

Architectural Workflow Comparison

AlphaFold-Multimer: A Specialized Extension

AlphaFold-Multimer builds directly upon the AlphaFold2 (AF2) framework. Its architecture retains the Evoformer module for processing Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) and the structure module that predicts atomic coordinates using a frame-based representation of amino acids, focusing on Cα atoms and side-chain torsion angles [23] [24]. Its primary adaptation for complexes was in the training procedure; it was trained on protein complexes and introduces a new loss function that prioritizes the accuracy of interfacial interactions, yielding the interface predicted TM (ipTM) score alongside the standard pTM [23] [25].

AlphaFold3: A Unified Diffusion-Based Framework

AlphaFold3 marks a substantial architectural departure. It replaces the Evoformer with a simpler Pairformer stack, which processes a paired representation of the input sequences and de-emphasizes the MSA representation [21] [24] [26]. Most notably, the frame-based structure module is replaced by a diffusion-based module that predicts raw atom coordinates directly [21]. This approach involves a generative process that starts with noise and iteratively refines the structure, allowing AF3 to natively handle proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, and ions without specialized parameterizations [21] [24]. This diffusion process also eliminates the need for explicit stereochemical penalty losses during training [21].

Inputs and Outputs: A Comparative Analysis

The capabilities of both systems are defined by their input requirements and the outputs they generate.

Input Requirements

- AlphaFold-Multimer: The primary input is a FASTA file containing the amino acid sequences of all protein chains in the complex [27] [25]. Users can optionally provide custom MSAs or template structures to guide the prediction [28].

- AlphaFold3: The input is more versatile, accepting protein sequences, nucleic acid sequences, and molecular definitions for ligands and modified residues using the SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) notation [23] [21]. This allows it to model a vast range of biomolecular complexes from sequence and chemical description alone.

Outputs and Confidence Metrics

Both systems output 3D atomic coordinates in PDB and mmCIF formats, accompanied by confidence metrics essential for interpreting prediction reliability [28] [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Outputs and Confidence Metrics

| Feature | AlphaFold-Multimer | AlphaFold3 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Structure of protein complexes [23] | Structure of general biomolecular complexes (proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, ions) [23] [21] |

| Local Confidence | pLDDT (per-residue local distance difference test) [28] | pLDDT (per-residue local distance difference test) [23] |

| Relative Domain Confidence | PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) matrix [28] | PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) matrix [21] |

| Complex-Specific Scores | pTM (predicted TM-score) and ipTM (interface pTM) for ranking models and assessing interface accuracy [25] | - |

| Additional Metric | - | PDE (Predicted Distance Error) matrix, estimating error in pairwise atom distances [21] |

Performance and Experimental Benchmarking

Independent benchmarking reveals the relative strengths and weaknesses of each tool across different biomolecular categories. A core protocol for evaluation involves comparing predicted models to experimentally determined ground-truth structures using metrics like DockQ (for interfaces) and TM-score (for global fold accuracy).

Performance on Protein Complexes

AlphaFold-Multimer set a new standard for protein-protein complex prediction. However, its performance can be inconsistent. It shows a bias towards interfaces formed by ordered protein regions, while struggling with interfaces involving disordered segments [14]. On the CASP15 benchmark, AlphaFold-Multimer serves as a strong baseline.

AlphaFold3 demonstrates substantially improved accuracy for certain types of protein-protein interactions, with one study reporting a significant leap in antibody-antigen prediction accuracy compared to AlphaFold-Multimer v.2.3 [21].

Performance on Diverse Biomolecules

This is where AlphaFold3's unified architecture shows its distinct advantage.

Table 2: Performance Across Biomolecular Interaction Types

| Complex Type | AlphaFold-Multimer Performance | AlphaFold3 Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein | State-of-the-art baseline, but struggles with disordered interfaces and antibodies [23] [14]. | Improved accuracy, particularly for antibody-antigen complexes [21]. |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | Not supported. Requires separate tools. | "Substantially higher accuracy" compared to previous nucleic-acid-specific predictors [21]. |

| Protein-Ligand | Not supported. Requires docking tools. | "Far greater accuracy" compared to state-of-the-art docking tools like Vina, even without using the protein's structure as input [21]. |

Recent independent benchmarking provides direct quantitative comparisons. In an evaluation on CASP15 multimer targets, DeepSCFold, a method that enhances AlphaFold-Multimer with sequence-derived structural complementarity, was reported to achieve an 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and a 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 [1]. In a more challenging test on antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, the same study found DeepSCFold enhanced the success rate for binding interfaces by 24.7% over AlphaFold-Multimer and 12.4% over AlphaFold3 [1]. This suggests that while AF3 is a powerful generalist, strategies that augment AF-Multimer with specialized information can still yield superior performance for specific tasks like antibody-antigen modeling.

Common Limitations and Failure Modes

Despite their advancements, both systems share fundamental limitations rooted in their training data and architecture:

- Dependence on Evolutionary Information: Both struggle to predict proteins with few homologs, such as antibodies [23].

- Static Structures: They predict a single, static structure and cannot model conformational changes or dynamics [23].

- Disordered Regions: Regions that are intrinsically disordered in reality may be predicted as structured or as unstructured "noodles" [23].

- Environmental Factors: Structures dependent on specific environmental conditions (e.g., membrane proteins in different states) are poorly captured [23].

- Hallucination Risk: AlphaFold3's diffusion decoder can sometimes "hallucinate" plausible-looking but incorrect secondary structures, particularly alpha-helices, in regions of low confidence. This makes consulting the pLDDT score critical [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Multimer Structure Prediction

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| FASTA Sequence File | A text-based file format for representing nucleotide or peptide sequences. | The primary input for both AlphaFold-Multimer (protein chains) and AlphaFold3 (protein/nucleic acid chains) [27] [25]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | A collection of evolutionary-related sequences aligned to highlight conserved regions. | Provides co-evolutionary signals; can be generated automatically or supplied by the user to guide predictions in AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 [28] [26]. |

| SMILES String | A line notation for encoding the structure of chemical molecules. | Required input for defining ligands, ions, and modified residues in AlphaFold3 [21]. |

| pLDDT (per-residue confidence) | A score between 0-100 representing local confidence at each residue position. | Critical for interpreting prediction quality. Residues with pLDDT > 90 are high confidence, while < 50 are very low confidence [23] [28]. |

| PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) Plot | A plot depicting the expected positional error between residues. | Used to assess inter-domain and inter-chain confidence. A low PAE between chains suggests high confidence in their relative orientation [28]. |

| PDB / mmCIF Format | Standard file formats for storing 3D structural data of biological molecules. | The standard output formats for predicted models, viewable in software like PyMOL or ChimeraX [28] [27]. |

In conclusion, the choice between AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 is context-dependent. AlphaFold-Multimer remains a highly specialized and effective tool for researchers focused exclusively on protein-protein complexes, especially when integrated into pipelines that enhance its MSA construction. Its well-defined protein-specific outputs like ipTM are valuable for dedicated interaction studies. In contrast, AlphaFold3 represents a monumental leap towards a unified predictive framework for structural biology. Its ability to model a vast spectrum of biomolecular interactions with high accuracy from sequence alone makes it an unparalleled tool for holistic cellular modeling and drug discovery efforts that involve ligands and nucleic acids.

However, the benchmarking data confirms that the field of multimer prediction is not settled. The performance of methods like DeepSCFold demonstrates that supplementing evolutionary signals with structural complementarity information can surpass a generalist model for specific challenges. Therefore, the assessment of accuracy must be ongoing, considering the specific biological question, the molecules involved, and the continual emergence of new specialized methods that build upon these foundational tools.

Predicting the three-dimensional structure of protein complexes, or multimers, is a fundamental challenge in structural biology with profound implications for understanding cellular functions and accelerating drug discovery. Unlike protein monomers, whose prediction was revolutionized by AlphaFold2, protein complexes require the accurate modeling of both intra-chain and inter-chain residue-residue interactions, presenting a significantly more difficult problem [1]. Although deep learning methods like AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 have advanced the field, their reliance on sequence-level co-evolutionary signals presents limitations, particularly for complexes lacking clear co-evolution, such as antibody-antigen systems [1]. This assessment evaluates a new generation of protein complex prediction tools, focusing on how DeepSCFold's innovative approach to leveraging sequence-derived structural complementarity addresses these limitations and enhances predictive accuracy.

Table 1: Core Protein Complex Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | Sequence-derived structural complementarity with paired MSA construction | Uses pSS-score and pIA-score to capture structural interaction patterns beyond co-evolution [1]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Extended AlphaFold2 architecture for multimers | Adapted for multiple chains but retains limitations in capturing inter-chain interactions [1]. |

| AlphaFold3 | End-to-end diffusion model for biomolecular complexes | Predicts complexes of proteins, nucleic acids, and more, but accuracy on protein complexes can be limited [1]. |

| Protein-Protein Docking | Assembling monomers based on shape complementarity | Exemplified by ZDOCK, HADDOCK; challenged by conformational sampling and interface flexibility [1]. |

DeepSCFold introduces a novel computational protocol that shifts the paradigm from relying solely on sequence co-evolution to explicitly leveraging structural complementarity inferred directly from sequence information. The pipeline integrates two key sequence-based deep learning models to construct superior paired Multiple Sequence Alignments (pMSAs), which are then used by AlphaFold-Multimer for final structure prediction [1] [29].

Protein-Protein Structural Similarity Prediction (pSS-score): This deep learning model predicts the Template Modeling score (TM-score)—a measure of structural similarity—between a query protein sequence and its homologs found in monomeric MSAs. The pSS-score integrates one-hot encoding, BLOSUM-62 substitution matrix, physicochemical features, and embeddings from the protein language model ESM2. The model architecture employs a multi-scale retention module to capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences, a criss-cross attention module to generate a sequence-pair representation, and a down-sample module for feature refinement [30]. This allows for ranking and selecting monomeric MSA homologs based on predicted structural similarity, not just sequence similarity.

Interaction Probability Prediction (pIA-score): This component predicts the probability of interaction between two protein sequences, again using only sequence-level features. It shares the same sophisticated architecture as the pSS-score model. The predicted pIA-scores are used to systematically concatenate sequence homologs from different subunit MSAs, thereby constructing biologically relevant paired MSAs that guide the structure prediction model toward accurate complex assembly [1] [30].

Integrated Paired MSA Construction and Complex Modeling: The pipeline starts by generating monomeric MSAs for each protein chain from multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB). The pSS-score refines these monomeric MSAs, and the pIA-score then pairs sequences across different MSAs. Additional paired MSAs are built using multi-source biological information like species annotation and known complex data from the PDB. This ensemble of high-quality pMSAs is fed into AlphaFold-Multimer. The top-ranked model, selected by an in-house quality assessment tool (DeepUMQA-X), is used as an input template for a final refinement iteration, producing the output structure [1] [29].

Diagram 1: The DeepSCFold prediction workflow.

Diagram 2: The deep learning model for pSS and pIA-score prediction.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

To objectively assess its performance, DeepSCFold was rigorously benchmarked against state-of-the-art methods using standard datasets. The evaluation metrics focused on both global structure accuracy (TM-score) and local interface quality (DockQ and interface success rate).

Table 2: Performance on CASP15 Multimeric Targets (TM-score) [1]

| Prediction Method | Average TM-score | Improvement over Baseline |

|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | To be reported | - |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline | - |

| AlphaFold3 | Baseline | - |

| Reported Improvement | DeepSCFold achieves an improvement of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively. |

Table 3: Performance on Antibody-Antigen Complexes (SAbDab Database) [1]

| Prediction Method | Interface Success Rate (DockQ > 0.23) |

|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | Highest Reported |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline |

| AlphaFold3 | Baseline |

| Reported Improvement | DeepSCFold enhances the success rate by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively. |

The experimental protocol for these benchmarks involved testing on a set of multimeric targets from the CASP15 competition. For each target, complex models were generated using protein sequence databases available up to May 2022, ensuring a temporally unbiased assessment. Predictions from other methods, including AlphaFold3 (via its online server), Yang-Multimer, MULTICOM, and NBIS-AF2-multimer, were retrieved from the CASP15 official website or generated via their public servers for a fair comparison [1]. A separate evaluation was conducted on antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, which are particularly challenging due to frequently absent inter-chain co-evolutionary signals [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

The following table details key resources and databases integral to running advanced protein complex prediction pipelines like DeepSCFold.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Databases for Complex Prediction

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| UniRef30/90, UniProt, BFD, MGnify | Sequence Databases | Provide the raw homologous sequences for constructing initial monomeric Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) [1] [29]. |

| ColabFold DB | Sequence Database | A curated database often used in conjunction with MMseqs2 for fast MSA construction [1]. |

| HHblits, Jackhammer, MMseqs2 | Sequence Search Tools | Software tools used to search sequence databases and generate the monomeric MSAs [1]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structure Database | Source of experimentally determined structures used for template-based modeling and for integrating biological information into paired MSA construction [1]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Structure Prediction Engine | The core deep learning model that generates 3D structure coordinates from the constructed paired MSAs [1] [29]. |

| DeepUMQA-X | Quality Assessment Method | An in-house model quality assessment method used by DeepSCFold to select the top-1 predicted structure for refinement [1] [29]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

DeepSCFold demonstrates that leveraging sequence-derived structural complementarity is a powerful strategy for enhancing protein complex prediction, particularly in scenarios where traditional co-evolutionary analysis fails. Its significant performance gains on challenging antibody-antigen complexes underscore the importance of capturing intrinsic and conserved protein-protein interaction patterns at the structural level [1]. This approach effectively compensates for the absence of inter-chain co-evolution, a common limitation in virus-host and antibody-antigen systems [1].

The field of multimer prediction continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing research focusing on predicting complexes of unknown stoichiometry, large supercomplexes, and dynamic conformational ensembles [19]. Future pipelines will likely integrate the strengths of various approaches, combining the physical realism of docking methods, the power of deep learning, and insights from structural bioinformatics to not only predict static structures but also enable functional interpretation of protein-protein interactions and reconstruct underlying biological mechanisms [19]. As these tools become more accurate and accessible, they are poised to dramatically accelerate research in structural biology, systems biology, and therapeutic development.

Predicting the structures and interactions of multimers, such as antibody-antigen complexes and enzyme-substrate pairs, represents a frontier challenge in computational biology. While tools like AlphaFold2 revolutionized monomeric protein structure prediction, accurately capturing the inter-chain interactions that define functional complexes remains formidable [1]. These specialized interactions are crucial for understanding immune response, enzymatic activity, and developing novel therapeutics. This guide objectively compares the performance of cutting-edge computational tools designed for these specific prediction tasks, providing researchers with experimental data to inform their methodological selections.

Performance Comparison of Prediction Tools

The tables below summarize the key performance metrics of state-of-the-art tools for predicting antibody-antigen interactions and enzyme complex specificity, based on recent benchmark studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Antibody-Antigen Complex Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Approach | Key Performance Metric | Benchmark Dataset | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [1] | Sequence-derived structure complementarity with deep learning | 24.7% higher success rate on binding interfaces vs. AlphaFold-Multimer; 12.4% vs. AlphaFold3 [1] | CASP15 multimer targets, SAbDab antibody-antigen complexes [1] | Effectively captures conserved protein-protein interaction patterns without relying solely on co-evolution. |

| Graphinity [31] | Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN) on complex structures | Test Pearson’s correlation up to 0.87 on experimental ΔΔG prediction [31] | AB-Bind dataset (645 mutations), SyntheticFoldXΔΔG_942723 [31] | Directly learns from atomistic graphs of wild-type and mutant complexes; robust on large synthetic data. |

| MVSF-AB [32] | Multi-View Sequence Feature learning | Outperforms existing sequence-based approaches on antibody-antigen affinity prediction [32] | Unobserved natural antibody-antigen affinity data, mutant strains [32] | Fuses semantic and residue features from sequences, effective without structural data. |

| Fingerprint-based with pLDDT [33] | Incorporates ESMFold's pLDDT as flexibility proxy | 92% AUC-ROC for Ab-Ag interaction prediction; state-of-the-art paratope prediction [33] | Curated antibody-antigen dataset [33] | Uses pLDDT to model antibody flexibility, crucial for CDR loop interactions. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Enzyme Specificity and Function Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Approach | Key Performance Metric | Benchmark Dataset | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity [34] | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network | 91.7% accuracy identifying single reactive substrate vs. 58.3% for previous model [34] | Experimental validation with 8 halogenases and 78 substrates [34] | Integrates enzyme-substrate interaction data at sequence and structural levels. |

| SOLVE [35] | Interpretable ensemble ML (RF, LightGBM, DT) on sequence tokens | High accuracy from enzyme vs. non-enzyme classification down to L4 substrate prediction [35] | Custom enzyme function dataset, stratified 5-fold cross-validation [35] | Uses only primary sequence; provides interpretability via Shapley analysis for functional motifs. |

| CAPIM [17] | Integrates P2Rank (pockets), GASS (active sites), & AutoDock Vina (docking) | Provides residue-level activity profiles and functional validation via docking [17] | Case studies on characterized and unannotated multi-chain targets [17] | Unifies pocket identification, catalytic site annotation, and docking for multimers. |

| BEC-Pred [36] | BERT-based model using reaction SMILES sequences | 91.6% accuracy for EC number prediction, 5.5% higher than other ML methods [36] | Dataset of enzymatic reactions with SMILES substrates/products [36] | Leverages transfer learning from general chemical reactions to predict EC numbers. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Benchmarking Complex Structure Prediction

The evaluation of protein complex prediction tools like DeepSCFold follows a rigorous protocol to ensure fair comparison [1].

- Dataset Curation: Benchmark sets are compiled from international competitions like CASP15 for general protein multimers and specialized databases like SAbDab for antibody-antigen complexes. Temporal filters are applied to ensure no data used for training is included in the test sets.

- MSA Construction: DeepSCFold first generates monomeric Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) from databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, MGnify). It then uses two deep learning models:

- A pSS-score predictor ranks homologs by structural similarity to the query.

- A pIA-score predictor estimates interaction probability between sequences from different subunit MSAs.

- Paired MSA Generation: The pIA-scores, along with biological data (species, UniProt IDs), guide the systematic concatenation of monomeric homologs into complex-focused paired MSAs.

- Structure Prediction & Selection: The paired MSAs are fed into a structure prediction engine (e.g., AlphaFold-Multimer). The top-1 model is selected by a quality assessment tool (e.g., DeepUMQA-X) and can be used as a template for a final refinement iteration [1].

Protocol for Evaluating Antibody-Antigen Affinity Prediction

Accurately predicting the change in binding affinity (ΔΔG) upon mutation is critical for antibody engineering. The protocol for tools like Graphinity involves [31]:

- Data Sourcing and Splitting: The AB-Bind dataset (645 single-point mutations from 29 complexes) is a common standard. To test generalizability, a length-matched CDR sequence identity cutoff (e.g., 90-100%) is enforced between training and test folds, preventing mutations from the same complex from appearing in both.

- Graph Representation: Wild-type and mutant antibody-antigen complex structures are converted into atomistic graphs. Nodes represent non-hydrogen atoms, and edges connect atoms within 4 Å.

- Model Training with a Siamese EGNN: A Siamese Equivariant Graph Neural Network processes the paired (WT and mutant) graphs. This architecture learns to compare the two states and directly regress the ΔΔG value.

- Robustness Analysis: Performance is evaluated across multiple random folds and with varying sequence identity cutoffs to detect overtraining and ensure the model learns general principles of binding rather than complex-specific patterns.

Protocol for Validating Enzyme Substrate Specificity

Experimental validation of computational predictions is the ultimate test. The protocol for EZSpecificity is a prime example [34]:

- Tool Prediction: EZSpecificity is used to score the potential reactivity of a library of 78 diverse substrates against a set of 8 halogenase enzymes.

- Experimental Testing: The top-ranked enzyme-substrate pairs, along with negative controls, are selected for wet-lab experimentation. This typically involves incubating the purified enzyme with the substrate under optimal conditions.

- Product Analysis: The reaction mixtures are analyzed using techniques like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to detect the formation of catalytic products.

- Accuracy Calculation: The accuracy is calculated as the percentage of cases where the tool's prediction (reactive/non-reactive) matches the experimental outcome. EZSpecificity achieved 91.7% accuracy in identifying the single potential reactive substrate for each halogenase [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful computational prediction relies on a suite of software tools and databases. The table below lists key "reagents" for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multimer Prediction

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer [1] | Software | Core engine for predicting protein complex structures from sequences and MSAs. |

| AutoDock Vina [17] | Software | Molecular docking tool used to validate predicted binding sites and estimate binding affinity. |

| P2Rank [17] | Software | Machine learning-based tool for predicting ligand-binding pockets on protein structures. |

| GASS [17] | Software | Identifies catalytically active residues and assigns EC numbers using structural templates. |

| UniProt/Swiss-Prot [35] | Database | Provides expertly curated protein sequences and functional annotations for MSA construction. |

| SAbDab [31] | Database | The Structural Antibody Database; a key resource for antibody-antigen complex structures. |

| ESMFold [33] | Software | Rapid protein structure prediction tool from sequences alone; its pLDDT output can serve as a proxy for flexibility. |

The landscape of predicting antibody-antigen and enzyme complexes is rapidly advancing, with specialized tools now outperforming general-purpose models. Key takeaways for researchers are:

- For antibody-antigen complexes, integrating structural complementarity (DeepSCFold) or conformational flexibility (pLDDT-based methods) addresses key limitations of MSA-only approaches [1] [33].

- For enzyme specificity, models that jointly learn from sequence, structure, and chemical reaction data (EZSpecificity, BEC-Pred) show markedly higher accuracy than their predecessors [34] [36].

- A critical challenge remains the scarcity of high-quality experimental data for training and validation, particularly for antibody affinity changes (ΔΔG) [31].

Future progress will likely hinge on generating larger and more diverse experimental datasets, further refining integrative models that combine physical principles with deep learning, and improving the prediction of dynamic interactions beyond static structures.