Benchmarking Protein Structure Prediction Servers: From AlphaFold to DeepSCFold

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical evaluation of protein structure prediction servers.

Benchmarking Protein Structure Prediction Servers: From AlphaFold to DeepSCFold

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical evaluation of protein structure prediction servers. We explore the foundational principles of protein structure prediction, from traditional homology modeling to revolutionary deep learning systems like AlphaFold. The content details practical methodologies for server application, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and presents a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of prediction tools using established benchmarks like CASP and EVA. By synthesizing insights from continuous benchmarking initiatives, this guide aims to empower scientists to select and utilize the most appropriate computational tools for their specific research needs in structural biology and drug discovery.

The Evolution of Protein Structure Prediction: From Experimental Methods to AI Revolution

For over 50 years, the "protein folding problem" – predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence – stood as one of the greatest challenges in biology [1] [2]. Understanding protein structure is fundamental to elucidating function, yet experimental structure determination through techniques like X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy has been time-consuming, costly, and technically demanding, creating a massive gap between known protein sequences and solved structures [3] [4]. This sequence-structure gap significantly hampered research across life sciences, from basic molecular biology to rational drug design.

Recent revolutionary advances in computational methods, particularly deep learning-based structure prediction, have fundamentally transformed this landscape. This guide provides an objective comparison of current protein structure prediction servers, evaluating their performance against experimental benchmarks to help researchers select appropriate tools for their specific needs.

The Computational Revolution in Structure Prediction

From Physical Principles to Deep Learning

The field of computational structure prediction has evolved through distinct phases. Early approaches relied on physical simulations of molecular driving forces or statistical approximations thereof, but proved computationally intractable for most proteins [1]. Template-based methods, including comparative modeling and homology modeling, leveraged evolutionary relationships to predict structures based on solved homologs, maturing into automated pipelines that significantly expanded structural coverage [3].

A paradigm shift occurred with the introduction of deep learning methods. The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, community-wide blind tests conducted biennially, documented steady progress until a breakthrough in the 14th edition (CASP14) in 2020 [1] [4]. AlphaFold2, developed by DeepMind, demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental structures in most cases, greatly outperforming all other methods and leading CASP organizers to declare the protein folding problem largely solved [1] [2].

The AlphaFold Breakthrough and Ecosystem

AlphaFold2 employs a novel neural network architecture that incorporates physical and biological knowledge about protein structure while leveraging multi-sequence alignments [1]. Its architecture consists of two key components: the EvoFormer, which processes input sequences and alignments through attention mechanisms, and a structure module that explicitly generates atomic coordinates through iterative refinement [1] [4].

The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, a collaboration between DeepMind and EMBL-EBI, provides open access to over 200 million structure predictions, dramatically expanding structural coverage of the protein universe [5]. This resource has become a standard tool for the research community, enabling structure-based approaches across diverse biological applications.

Performance Comparison of Structure Prediction Servers

Accuracy Metrics and Benchmarking Framework

Protein structure prediction servers are evaluated using standardized metrics that quantify similarity to experimentally determined reference structures:

- lDDT (local Distance Difference Test): A superposition-free score evaluating local distance consistency of residues (0-100 scale, higher is better)

- CAD-score: Measures global topology similarity through contact area difference

- TM-score: Assesses global fold similarity while accounting for protein size

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Measures average distance between corresponding atoms after superposition (lower is better)

- pLDDT: AlphaFold's predicted confidence score per residue (0-100 scale)

The Continuous Automated Model Evaluation (CAMEO) project provides independent, weekly assessments of prediction servers using recently solved structures not yet publicly available, offering real-time performance benchmarks [6].

Server Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance of major prediction servers based on CAMEO-3D benchmark data, using Naive AlphaFoldDB as a reference for comparison:

| Server Name | Avg. lDDT | Avg. CAD-score | Avg. lDDT-BS | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive AlphaFoldDB | 93.45 | 86.21 | - | Reference server with high accuracy |

| Phyre2 | +28.38 | +27.83 | +10.04 | Template-based modeling method |

| RoseTTAFold | +12.51 | +9.86 | +17.43 | Deep learning method using similar principles to AlphaFold |

| IntFOLD6-TS | +12.40 | +11.06 | +3.05 | Integrated protein structure prediction server |

| SWISS-MODEL | -2.10 | -0.81 | -0.84 | Well-established homology modeling server |

| OpenComplex | -8.98 | -5.40 | -1.08 | Designed for complex biomolecular assemblies |

| SAIS-Fold | -3.72 | -2.11 | -0.15 | Alternative deep learning approach |

Table 1: Performance comparison of protein structure prediction servers based on CAMEO-3D benchmark data (2025-01-04). Values represent differences from Naive AlphaFoldDB reference (higher positive values indicate better performance). Adapted from CAMEO-3D server comparison data [6].

Performance Across Protein Types

Prediction accuracy varies significantly across different protein classes:

Globular Proteins: Most deep learning methods achieve high accuracy (lDDT > 80) for well-characterized protein families with sufficient homologous sequences [1] [4].

Membrane Proteins: Prediction remains challenging due to limited experimental structures for training, though methods like AlphaFold2 have shown reasonable performance for transmembrane helices [7] [8].

Peptides: Short peptides (10-40 amino acids) present unique challenges. AlphaFold2 predicts α-helical, β-hairpin, and disulfide-rich peptides with reasonable accuracy but shows limitations with non-helical secondary structures, solvent-exposed peptides, and precise Φ/Ψ angle recovery [8]. Performance comparison on peptide benchmarks shows deep learning methods generally outperform specialized peptide predictors:

| Prediction Method | Peptide Type | Normalized Cα RMSD (Å/residue) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | α-helical membrane-associated | 0.098 | Poor Φ/Ψ angle recovery |

| AlphaFold2 | α-helical soluble | 0.119 | Struggles with helix-turn-helix motifs |

| AlphaFold2 | Mixed structure membrane | 0.202 | Fails to predict unstructured regions |

| AlphaFold2 | β-hairpin peptides | 0.139-0.177 | Varies by solvent exposure |

| AlphaFold2 | Disulfide-rich | 0.138-0.292 | Disulfide bond pattern inaccuracies |

| OmegaFold | Various peptides | Comparable to AF2 | No MSA requirement |

| PEP-FOLD3 | Various peptides | Generally higher RMSD | De novo folding approach |

| APPTEST | Various peptides | Generally higher RMSD | Combines neural networks with MD |

Table 2: Performance of prediction methods on peptide structure benchmarks (10-40 amino acids). RMSD values normalized per residue. Data compiled from McDonald et al. [8].

Intrinsically Disordered Regions: Both AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 show limitations in predicting highly flexible or disordered regions, often resulting in low confidence scores (pLDDT) for these segments [4] [8].

Multi-protein Complexes and Ligand Interactions: AlphaFold3 demonstrates enhanced capability for predicting structures and interactions of proteins with other biomolecules (DNA, RNA, ligands), representing a significant advancement over previous versions [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Workflow

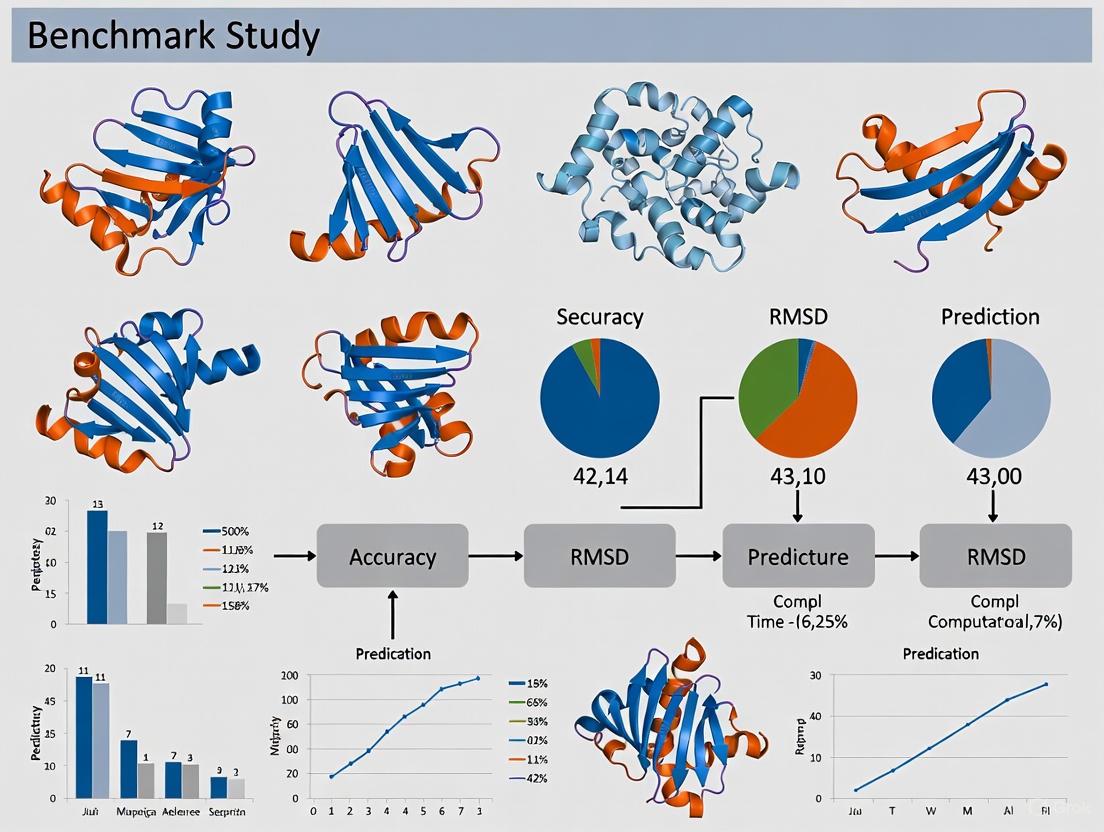

Diagram Title: Protein Structure Benchmarking Workflow

Data Collection: Benchmarking begins with curation of high-resolution experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). To prevent bias, structures determined after the training cut-off dates of prediction methods are preferentially selected [1] [8]. The benchmark set should represent diverse protein classes, including membrane proteins, peptides, and multi-domain proteins.

Structure Prediction: Each server generates predictions for the benchmark sequences using default parameters. For comprehensive evaluation, multiple runs with different configurations may be performed.

Structure Comparison: Predicted structures are compared to experimental references using multiple metrics (lDDT, RMSD, TM-score, CAD-score) to capture different aspects of structural accuracy [6] [8].

Statistical Analysis: Results are aggregated across the benchmark set, with particular attention to performance variation across different protein classes and structural features.

CAMEO-3D Evaluation Protocol

The CAMEO-3D project implements a continuous evaluation system:

- Target Selection: Weekly release of protein sequences with recently solved but unpublished structures

- Server Predictions: Participating servers submit structure predictions within specified time limits

- Blind Assessment: Independent evaluation using multiple metrics against experimental structures

- Performance Ranking: Regular publication of server performance rankings [6]

Essential Databases and Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Structure Database | Provides pre-computed AlphaFold predictions for 200+ million proteins | Public [5] |

| Protein Data Bank | Structure Repository | Archive of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids | Public [3] |

| UniProt | Sequence Database | Comprehensive resource of protein sequence and functional information | Public [9] |

| CAMEO-3D | Benchmarking Platform | Continuous evaluation of protein structure prediction methods | Public [6] |

| PEP-FOLD3 | Prediction Server | De novo peptide structure prediction for 5-50 amino acid peptides | Public [8] |

| RoseTTAFold | Prediction Server | Deep learning method for protein structure prediction | Public [8] |

| OmegaFold | Prediction Server | Deep learning method that operates without multiple sequence alignments | Public [8] |

Table 3: Essential resources for protein structure prediction and analysis.

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite remarkable progress, current prediction methods face several challenges:

Orphan Proteins: Performance remains limited for proteins with few homologous sequences ("orphans") or from underrepresented taxonomic groups [4].

Dynamic States and Conformational Changes: Static structure predictions cannot capture functional dynamics, allosteric transitions, or fold-switching behavior [3] [4].

Complex Assemblies: While AlphaFold3 shows improved performance for complexes, prediction of large multi-protein assemblies remains challenging [4].

Conditional Dependence: Current models do not account for environmental factors such as pH, temperature, or cellular context that influence protein structure [8].

Future developments will likely focus on integrating structural predictions with molecular dynamics simulations, incorporating environmental factors, and modeling conformational landscapes rather than single structures.

The field of protein structure prediction has undergone a revolutionary transformation, moving from a situation where the "structure knowledge gap" hampered research to one where structural information is accessible for the majority of amino acids in common model organism genomes [3]. Deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 and its successors have achieved accuracy competitive with experimental methods for many protein types, though significant limitations remain for specific classes including peptides, membrane proteins, and dynamic complexes.

Researchers should select prediction servers based on their specific needs, considering factors such as target protein type, required accuracy, and need for additional features like complex prediction. Continuous benchmarking through resources like CAMEO-3D provides essential guidance for method selection and development. As these tools continue to evolve, they promise to further bridge the sequence-structure gap, enabling new discoveries across structural biology, drug discovery, and protein design.

Proteins are fundamental macromolecules that perform a vast array of functions in living organisms, from catalyzing biochemical reactions to providing structural support and facilitating cellular communication [10]. The function of a protein is directly determined by its intricate three-dimensional structure, which arises from a hierarchy of organizational levels [11]. Understanding these structural levels—primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary—is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to elucidate biological mechanisms, predict protein behavior, and design effective therapeutics [12]. This hierarchical model provides a conceptual framework for understanding how a linear amino acid sequence folds into a complex, functional conformation, with each level of organization stabilized by distinct types of interactions and forces [13]. The precise three-dimensional arrangement of a protein enables specific interactions with other molecules, such as drugs, hormones, or DNA, making structural knowledge indispensable for rational drug design and understanding disease pathologies [12] [14]. In the context of modern computational biology, these structural definitions also form the basis for benchmarking protein structure prediction servers, which aim to bridge the gap between the vast number of known protein sequences and the relatively small number of experimentally determined structures [15] [10].

The Four Levels of Protein Structure

Primary Structure

The primary structure of a protein is the most fundamental level of its organization, defined as the unique, linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain [11] [14]. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are joined together by peptide bonds, which form between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of the next, releasing a water molecule in a dehydration condensation reaction [12] [10]. By convention, the primary structure is written and read from the amino-terminal (N-terminus) to the carboxyl-terminal (C-terminus) end [13] [14]. This sequence is genetically determined by the nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene [11]. There are 20 different standard L-α-amino acids used in protein synthesis, each with a unique side chain (R group) that confers specific chemical properties (e.g., acidic, basic, polar, or nonpolar) [12]. The primary structure is stabilized solely by covalent peptide bonds, which are particularly strong due to their partial double-bond character, limiting rotation and contributing to the planar nature of the peptide group [14]. Even a single amino acid substitution in the primary structure can have dramatic functional consequences, as exemplified by sickle cell anemia, where valine replaces glutamic acid in the hemoglobin β chain, leading to dysfunctional hemoglobin protein and misshapen red blood cells [11].

Secondary Structure

The secondary structure refers to the local, regular folding patterns that arise within segments of the polypeptide backbone, stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds between backbone functional groups [13] [11]. The two most common and stable secondary structures are the α-helix and the β-sheet.

- α-Helix: This structure is a right-handed coiled conformation, resembling a spring [13] [11]. The backbone atoms form the inner part of the helix, while the side chains radiate outward. Hydrogen bonds form between the carbonyl oxygen (C=O) of one amino acid and the amino hydrogen (N-H) of another located four residues further along the chain (i → i+4 bonding) [13] [11]. This pattern results in 3.6 amino acid residues per complete turn, with a rise of approximately 5.4 Å per turn [13]. The α-helix has an overall dipole moment, with a partial positive charge at the N-terminus and a partial negative charge at the C-terminus [13]. Amino acids such as alanine, glutamate, leucine, and methionine have a high propensity to form α-helices, while proline and glycine are helix disruptors [13].

- β-Sheet: Also known as the β-pleated sheet, this structure is formed by stretches of the polypeptide chain (β-strands) that are almost fully extended and aligned side-by-side [13] [11]. Hydrogen bonds form between the carbonyl oxygens and amino hydrogens of adjacent strands, stabilizing the sheet. The participating β-strands can be from segments that are not close to each other in the primary sequence [13]. β-Sheets can be parallel (adjacent strands run in the same N- to C-terminal direction), antiparallel (adjacent strands run in opposite directions), or mixed [13] [11]. The antiparallel arrangement is generally more stable due to more optimal hydrogen bond geometry [12]. The sheet has a characteristic right-handed twist when viewed along the strand direction [13].

Unlike tertiary and quaternary structures, secondary structure formation involves hydrogen bonding between atoms of the polypeptide backbone, not the amino acid side chains [10] [14]. These local structures are often depicted in molecular visualizations as ribbons (α-helices) and arrows (β-strands) [13].

Figure 1: Hierarchical organization of protein structure from amino acids to the final quaternary complex, showing the key structural elements and stabilizing interactions at each level.

Tertiary Structure

The tertiary structure describes the overall three-dimensional shape of a single, fully folded polypeptide chain, resulting from the folding and packing of secondary structure elements (α-helices, β-sheets, and connecting loops) into a specific globular or fibrous conformation [12] [10]. This level of structure is stabilized by various interactions between the amino acid side chains (R groups), which can be widely separated in the primary sequence but are brought into proximity by folding [12] [14]. The native, functional tertiary structure represents the most stable, low-energy state for the protein under physiological conditions [10]. The forces involved in stabilizing tertiary structure include:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Nonpolar, hydrophobic side chains (e.g., from phenylalanine, isoleucine, leucine, valine) tend to cluster in the interior of the protein, away from the aqueous environment, driving the folding process and providing stability through the hydrophobic effect and dispersion forces [12] [14].

- Hydrogen Bonding: Polar side chains can form hydrogen bonds with other polar groups or with water molecules on the protein's surface [12] [14].

- Salt Bridges: These are ionic interactions between positively charged (e.g., lysine, arginine) and negatively charged (e.g., aspartic acid, glutamic acid) side chains [12] [14].

- Disulfide Bridges: Covalent bonds formed between the sulfur atoms of cysteine residues that are in close proximity, which can securely link different parts of the polypeptide chain [12] [14].

- Van der Waals Forces: Weak attractive forces between closely packed atoms.

The tertiary structure fully defines the spatial location of every atom in the polypeptide chain, creating unique features such as active sites for enzymes and binding pockets for ligands, which are essential for the protein's biological function [10].

Quaternary Structure

The quaternary structure refers to the three-dimensional arrangement of multiple, independently folded polypeptide chains (called subunits) to form a larger, functional protein complex [13] [14]. Not all proteins possess quaternary structure; it is a feature of multisubunit proteins [14]. The subunits can be identical (forming a homodimer, homotrimer, etc.) or different (forming a heterodimer, etc.), as seen in hemoglobin, which consists of two α-globin and two β-globin subunits [11] [14]. The interactions that stabilize quaternary structure are the same non-covalent interactions that stabilize tertiary structure—hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges—occurring between the side chains of the different subunits [12] [14]. In some cases, disulfide bridges may also link subunits. The formation of quaternary structure can confer functional advantages, such as cooperativity (as in hemoglobin, where the binding of oxygen to one subunit increases the oxygen affinity of the remaining subunits), stability, and the creation of large, multifunctional complexes essential for complex cellular processes like signal transduction and transcription [16].

Experimental Methodologies for Structure Determination

Determining the precise three-dimensional structure of a protein is critical for understanding its function and for structure-based drug design. The following table summarizes the primary experimental techniques used, along with their key principles and limitations.

Table 1: Key Experimental Methods for Protein Structure Determination

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Application & Resolution | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Measures the diffraction pattern of X-rays passing through a protein crystal to calculate an electron density map [12]. | High-resolution atomic structures. Requires large, well-ordered single crystals [12]. | Challenging for membrane proteins and highly flexible proteins; crystal packing may not reflect the physiological state [12]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Utilizes the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei in solution to determine distances between atoms (via NOESY) and through bonds (via COSY), enabling 3D structure calculation [12]. | Solution-state structures of smaller proteins; studying protein dynamics and folding. | Generally limited to smaller proteins (< ~25-30 kDa); requires high protein concentration and solubility [12]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Involves flash-freezing protein samples in vitreous ice and using an electron microscope to capture thousands of 2D images, which are computationally reconstructed into a 3D model [16]. | High-resolution structures of large complexes, membrane proteins, and assemblies that are difficult to crystallize [16]. | Lower resolution for very flexible regions; requires significant computational resources and sample homogeneity. |

Beyond these high-resolution methods, other techniques provide insights into specific structural aspects. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy is used to estimate the proportion of secondary structure elements (α-helix, β-sheet, random coil) in a protein sample by measuring its differential absorption of left- and right-handed circularly polarized light in the far-UV region [12]. For analyzing the primary structure, techniques such as amino acid analysis, Edman degradation (for N-terminal sequencing), and mass spectrometry (for peptide fingerprinting and sequencing) are routinely employed [12].

Computational Protein Structure Prediction: A Benchmarking Perspective

The "structural gap" between the number of known protein sequences (over 254 million in UniProtKB/TrEMBL) and experimentally determined structures (around 230,000 in the PDB) has driven the development of computational structure prediction methods, which are now indispensable tools in structural biology [15] [10]. These methods can be broadly categorized, and their performance is rigorously evaluated in community-wide experiments like the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) [17].

Table 2: Categories of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Category | Core Principle | Key Tools / Examples | Key Challenges & Context in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Predicts structure by aligning the target sequence to one or more evolutionarily related proteins with known structures (templates) [10]. | MODELLER, SwissPDBViewer [10]. | Accuracy depends heavily on template availability and quality of sequence alignment; less useful for novel folds [10]. |

| Template-Free Modeling (TFM) | Uses deep learning on multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and other sequence-derived features to predict structures without relying on explicit global templates [10]. | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, TrRosetta [10] [17]. | Performance can drop for proteins with few homologous sequences or in modeling conformational diversity and complexes [15] [16]. |

| Ab Initio / De Novo Modeling | Predicts structure based solely on physicochemical principles and energy minimization, without using evolutionary information or templates [10]. | DMFold, RoseTTAFold [16]. | The most challenging category; historically limited to small proteins but has seen dramatic improvements with deep learning [17]. |

Benchmarking Insights from CASP and Recent Studies

The CASP experiments have documented the revolutionary progress in the field, particularly since the introduction of deep learning. CASP14 (2020) marked a paradigm shift with AlphaFold2, which produced models competitive with experimental accuracy for about two-thirds of the targets [17]. This trend has continued, with methods now tackling the more difficult challenge of predicting the structures of protein complexes (quaternary structure). In CASP15 (2022), the accuracy of multimer models almost doubled in terms of interface prediction compared to CASP14, thanks to new methods like AlphaFold-Multimer and DeepSCFold [16] [17].

However, systematic benchmarking reveals persistent limitations. A 2025 comprehensive analysis of nuclear receptors showed that while AlphaFold2 achieves high accuracy for stable monomeric conformations, it systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and often fails to capture the full spectrum of biologically relevant conformational states, particularly in flexible regions and in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functional asymmetry [15]. This highlights a key challenge for prediction servers: accurately modeling structural plasticity and ligand-induced conformational changes, which are critical for drug discovery.

For complex prediction, DeepSCFold represents a recent advance. It uses deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability from sequence, constructing improved paired multiple sequence alignments. In benchmarks, it achieved an 11.6% and 10.3% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, on CASP15 targets, and significantly improved the prediction of antibody-antigen interfaces [16]. This demonstrates that incorporating explicit structural complementarity signals can compensate for weak co-evolutionary signals in certain complexes.

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for modern deep learning-based protein structure prediction, illustrating the key steps from sequence input to final model selection.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Protein Structural Biology

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A central, worldwide repository for experimentally determined 3D structural data of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. Serves as the primary source of "ground truth" for training prediction algorithms and benchmarking their output [15] [10] [17]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provides open access to millions of predicted protein structures generated by AlphaFold, acting as a powerful hypothesis-generating tool for researchers when experimental structures are unavailable [15]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Databases (e.g., UniRef, BFD, MGnify) | Collections of protein sequences used to build MSAs, which are critical for extracting evolutionary constraints and co-evolutionary signals that guide deep learning-based structure prediction methods like AlphaFold2 and DeepSCFold [16] [10]. |

| Stabilization Buffers & Crystallization Screens | Chemical solutions used to maintain protein native state in solution (buffers) and to identify optimal conditions for growing diffraction-quality protein crystals, a major bottleneck in X-ray crystallography [12]. |

| Proteases (Trypsin, Chymotrypsin) | Enzymes used to cleave proteins at specific amino acid residues for peptide mapping and mass spectrometric analysis, which helps confirm primary structure and identify post-translational modifications [12]. |

| Detergents & Lipids | Essential for solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins, which are traditionally difficult targets for structural studies but are highly relevant for drug development [12]. |

The four-level hierarchy of protein structure provides an essential framework for understanding how sequence dictates function. For researchers and drug developers, mastery of these concepts is no longer confined to interpreting experimental data but is fundamental to leveraging the powerful computational tools that now dominate structure prediction. Benchmarking studies reveal that while modern AI-based servers have largely solved the problem of predicting static monomer folds for many targets, significant challenges remain. These include accurately modeling quaternary structures, capturing conformational dynamics and flexibility, and predicting the precise geometry of functional sites like ligand-binding pockets. The continued integration of robust experimental data with increasingly sophisticated computational models promises to further close the gap between sequence and function, accelerating discovery in basic biology and therapeutic development.

The determination of protein three-dimensional (3D) structures is fundamental to understanding biological function and driving drug discovery. Experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have been the traditional cornerstones of structural biology. Yet, despite their transformative impact, each technique possesses inherent limitations regarding the types of macromolecules they can study, the resolution they can achieve, and the operational challenges involved. For researchers conducting benchmark studies on protein structure prediction servers, a clear understanding of these experimental constraints is essential. Such knowledge provides the critical context for evaluating computational models, explaining discrepancies between predicted and experimentally determined structures, and guiding the selection of appropriate experimental data for validation. This guide objectively compares the performance, limitations, and methodological details of these three primary techniques to support rigorous structural bioinformatics research.

Core Limitations at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and limitations of X-ray crystallography, NMR, and cryo-EM.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Primary Protein Structure Determination Methods

| Feature | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Limitation | Requires high-quality crystals; struggles with flexible proteins or transient states [18] [19] | Rapidly becomes intractable for large proteins and complexes [19] | High instrument cost and complexity; potential model bias in low-resolution maps [20] [21] |

| Typical Sample State | Static, crystallized | Dynamic, in solution (near-native) | Vitrified, in solution (near-native) |

| Key Operational Challenge | "Crystallization bottleneck" – process is often time-consuming and unsuccessful [18] | Spectral overlap and interpretation complexity for large systems [22] | Extensive data processing required to overcome low signal-to-noise ratio [23] |

| Size Range | Versatile, from small to very large complexes | Best for small to medium-sized proteins (generally < 40-50 kDa) [19] | Ideal for large complexes (> 50 kDa); lower size limit is a challenge [23] |

| Insight into Dynamics | Limited; usually provides a single, static snapshot | Excellent; can probe dynamics across a wide range of timescales [24] | Moderate; can infer flexibility from heterogeneity analysis |

| Resolution Range | Atomic (typically < 2.0 Å) to low resolution | Atomic for well-structured regions of smaller proteins | Near-atomic to low resolution (varies significantly) |

Detailed Limitations and Methodologies

X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography has been a cornerstone of structural biology, responsible for determining the high-resolution structures of countless proteins. Its major strength lies in its ability to provide an atomic-resolution snapshot of a protein's structure. However, its path to a solved structure is fraught with specific challenges.

Key Limitations

- The Crystallization Bottleneck: The most significant limitation is the absolute requirement for high-quality, well-ordered crystals. Many proteins, particularly large, flexible, or membrane-bound macromolecules, are notoriously difficult or impossible to crystallize [18] [19]. This process is often time-consuming, expensive, and can require extensive screening of thousands of conditions.

- Static Snapshot and Crystal Packing Artifacts: The structure derived is a static average of millions of molecules packed in a crystal lattice. This environment may not reflect the protein's true conformation in solution and can be influenced by crystal packing forces, potentially stabilizing non-physiological conformations [19].

- The Phase Problem: A fundamental challenge in crystallography is the "phase problem"—diffraction experiments measure the intensity of X-rays (amplitudes) but lose the phase information, which is essential for calculating the electron density map. Solving this problem often requires additional experimental methods like molecular replacement or experimental phasing with heavy atoms, which can be non-trivial [25].

Representative Experimental Protocol

The general workflow for structure determination via X-ray crystallography involves several standardized steps:

- Protein Purification and Crystallization: The protein is purified to homogeneity and subjected to crystallization trials using vapor diffusion, batch, or other methods to find conditions that yield diffraction-quality crystals.

- Data Collection: A single crystal is flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen (cryo-cooling) and exposed to a high-intensity X-ray beam at a synchrotron source. The resulting diffraction pattern is recorded by a detector.

- Data Processing: The diffraction images are processed to determine the crystal's unit cell dimensions, space group, and to generate a list of structure factor amplitudes.

- Phasing: The phase problem is solved using methods like Molecular Replacement (if a similar structure is known) or experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD with selenomethionine).

- Model Building and Refinement: An atomic model is built into the experimental electron density map and iteratively refined against the diffraction data to improve its agreement and geometry.

Diagram 1: X-ray crystallography workflow. The major bottleneck (crystallization) is highlighted.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy uniquely enables the study of proteins and their dynamics in a solution environment that closely mimics physiological conditions. It is unparalleled in its ability to probe biomolecular motions across a wide range of timescales, which are critical for function [24].

Key Limitations

- Size and Complexity Barrier: As the molecular weight of a protein increases, the number of NMR signals grows and their resonance lines broaden, leading to severe spectral overlap and a rapid decline in the quality of data. While advancements continue, NMR is predominantly applicable to small and medium-sized proteins (typically under 40-50 kDa) [19].

- Spectral Assignment and Interpretation: The process of assigning thousands of NMR signals to specific atoms in the protein is labor-intensive, expertise-dependent, and becomes a major bottleneck for larger systems [22] [18].

- Intrinsic Computability and Sensitivity: Although NMR parameters like chemical shifts are computable from first principles, the computational cost for high-level quantum mechanical calculations on large molecules is substantial [22]. Furthermore, NMR is an inherently insensitive technique, often requiring high protein concentrations (e.g., ~1 mM for CEST experiments) and long acquisition times, which can be impractical for some targets [26].

Representative Experimental Protocol: CEST

Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) is a powerful NMR method for studying "invisible" minor conformational states that are in slow exchange with a major, visible state [24] [26]. The protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: A uniformly 15N-labeled protein sample is prepared in a suitable buffer.

- CEST Experiment: A series of 1D or 2D NMR spectra are acquired. In each, a weak radiofrequency pulse is applied at a specific offset frequency for a long duration (e.g., hundreds of milliseconds). This pulse selectively saturates (reduces the signal of) nuclei in conformations that resonate at that frequency.

- Titration of Saturation: The experiment is repeated with the saturation pulse applied across a wide range of offset frequencies, creating a "CEST profile" or "Z-spectrum".

- Data Analysis: The resulting dip in signal intensity in the major state, observed when the saturation pulse is on-resonance with the minor state, is analyzed using a model of chemical exchange to extract parameters of the minor state, including its population, lifetime, and chemical shift [26].

Diagram 2: NMR CEST experiment workflow for studying minor conformational states.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Cryo-EM has undergone a "resolution revolution," establishing itself as a primary method for determining structures of large, flexible complexes that are recalcitrant to crystallization [23] [19]. Its key advantage is the ability to analyze samples in a vitrified, near-native state without the need for crystals.

Key Limitations

- High Cost and Complexity: The initial capital investment for a high-end cryo-EM instrument, along with its maintenance and operation, is substantial, potentially limiting access for some laboratories [20].

- Sample Preparation and Preferred Size: Preparing a thin, homogeneous layer of vitreous ice containing well-dispersed particles is a critical and often difficult step. While excellent for large complexes, there is a lower size limit (currently around ~50 kDa), below which the signal-to-noise ratio becomes too low for high-resolution reconstruction [23].

- Resolution Heterogeneity and Model Bias: The achievable resolution is not uniform across a map; flexible regions may remain at low resolution or be invisible. For maps with a resolution worse than ~3.5 Å, building atomic models becomes challenging and can suffer from bias, especially if starting from an incorrect model [21].

Representative Experimental Protocol: Single-Particle Analysis

The dominant cryo-EM method for protein structure determination is single-particle analysis, which involves the following steps:

- Vitrification: A purified sample solution is applied to an EM grid, blotted to form a thin film, and rapidly plunged into a cryogen (like liquid ethane) to vitrify the water, embedding the particles in a glass-like ice layer.

- Data Acquisition: The grid is loaded into the cryo-electron microscope, and thousands to millions of low-dose micrograph images (2D projections) are collected automatically using a direct electron detector.

- Image Processing: This is a computationally intensive stage. It involves:

- Particle Picking: Automated software identifies individual protein particles in the micrographs.

- 2D Classification: Particles are grouped into classes representing different views.

- 3D Reconstruction: A low-resolution initial model is generated and then iteratively refined against the particle images to produce a final 3D electron density map.

- Atomic Model Building: For high-resolution maps (better than ~3.5 Å), atomic models can be built de novo. For lower-resolution maps, existing models or predicted structures (e.g., from AlphaFold) are often flexibly fitted into the density [21] [19].

Diagram 3: Cryo-EM single-particle analysis workflow.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The table below lists key reagents, software, and instruments critical for research in these structural biology methods.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Structural Biology

| Category | Item | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Isotopically Labeled Compounds (e.g., 15N, 13C) | Enables NMR studies of proteins by providing detectable nuclear spins [26]. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Commercial suites of chemical conditions to empirically identify initial protein crystallization conditions. | |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Specimen supports, often with a holy carbon film, used to hold and vitrify the sample for EM imaging. | |

| Instrumentation | High-Field NMR Spectrometer | The core instrument for acquiring NMR data; magnetic field strength (e.g., 600-1000 MHz) is key for sensitivity. |

| Synchrotron Beamline | Source of high-intensity, tunable X-rays for collecting high-quality diffraction data from crystals. | |

| Cryo-Electron Microscope | Microscope equipped with a direct electron detector and cryo-stage for imaging vitrified samples [19]. | |

| Software & Computation | Structure Refinement Suites (e.g., PHENIX, Refmac) | Software for refining atomic models against X-ray diffraction or cryo-EM map data. |

| NMR Data Processing (e.g., NMRPipe, TopSpin) | Programs for processing, analyzing, and visualizing multi-dimensional NMR data. | |

| Cryo-EM Processing Suites (e.g., RELION, cryoSPARC) | Software packages for the extensive computational processing required in single-particle analysis [21]. | |

| AI Prediction Servers (e.g., AlphaFold2) | Computational tools that predict protein structures from sequence, often used to guide or validate experimental models [18] [19]. |

The prediction of three-dimensional protein structures from amino acid sequences represents one of the most significant challenges in computational biology. For decades, the field was dominated by template-based modeling (TBM) approaches, which rely on evolutionary relationships to known structures. However, recent advances in artificial intelligence have catalyzed a fundamental shift toward template-free modeling (TFM), revolutionizing the field and earning recognition with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [27]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing methodologies, examining their underlying principles, performance characteristics, and practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals operating within the context of benchmark studies for protein structure prediction servers.

The core distinction between these approaches lies in their use of existing structural knowledge. TBM, also known as homology modeling, operates on the principle that evolutionarily related proteins share similar structures, constructing models based on identifiable templates from databases like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [28] [29]. In contrast, TFM methods (often called de novo or free modeling) predict structure directly from sequence, employing either physicochemical principles or deep learning algorithms to infer spatial relationships without explicit template reliance [28] [27]. While modern AI systems like AlphaFold are frequently described as "template-free," it is important to note that they are indirectly dependent on known structural information through training on large-scale PDB data, unlike pure ab initio methods based solely on physicochemical laws [28].

Methodological Foundations: A Comparative Analysis

Core Principles and Workflows

Template-Based Modeling (TBM) operates on the foundational biological principle that evolutionarily related proteins share structural similarities. The methodology requires identifying a template structure with sufficient sequence similarity to the target protein, typically through sequence alignment tools like BLAST or more sensitive profile-based methods [28] [29]. The quality of the resulting model is heavily dependent on the degree of sequence identity between target and template, with generally reliable models produced above 30% sequence identity [28]. The TBM workflow systematically progresses through template identification, sequence alignment, backbone model construction, loop and side-chain modeling, and finally structural refinement [28].

Template-Free Modeling (TFM) encompasses a spectrum of approaches united by their non-reliance on global template structures. Traditional TFM methods utilized fragment assembly and physicochemical principles to explore conformational space, while modern implementations leverage deep learning architectures trained on known protein structures [28] [27]. Systems like AlphaFold2 employ attention-based neural networks that process multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to predict spatial constraints including inter-residue distances and torsion angles, which are then converted into 3D coordinates [28] [30]. Notably, these AI-based methods do not explicitly use templates, though their models are trained on PDB data, creating an indirect dependency that distinguishes them from pure ab initio approaches [28].

Key Methodological Differences

Table 1: Fundamental Methodological Distinctions Between TBM and TFM

| Aspect | Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Template-Free Modeling (TFM) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Leverages evolutionary relationship to known structures | Infers structure from sequence correlations or physical principles |

| Template Dependency | Requires identifiable template with >30% sequence identity | No explicit template requirement (though AI methods trained on PDB) |

| Computational Approach | Sequence alignment, comparative modeling, threading | Deep learning (AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold) or physical simulations |

| Key Input Data | Target sequence, template structure(s) | Target sequence, multiple sequence alignments (for AI methods) |

| Primary Output | Atomic coordinates based on template structure | De novo generated atomic coordinates |

| Strength Domain | High accuracy with good templates | Broad applicability across diverse protein classes |

| Automation Level | Often requires expert curation | Highly automated end-to-end prediction |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Accuracy Metrics and Assessment Protocols

Critical assessment of protein structure prediction methods employs standardized metrics, most notably the Global Distance Test (GDT), which measures the percentage of residues positioned within specific distance thresholds from their correct locations in the experimental structure. The CASP (Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction) experiments provide the most authoritative independent evaluations, with CASP16 (2024) reaffirming the dominance of deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, in overall accuracy [30].

Experimental protocols for benchmarking typically involve blind prediction of proteins with recently solved but unpublished structures, ensuring unbiased evaluation. Standardized assessment pipelines calculate multiple quality metrics including GDT_TS (global distance test total score), RMSD (root mean square deviation), and model quality assessment programs (MQAPs) that estimate model reliability [30] [27]. For protein complex prediction, additional interface-specific metrics such as interface RMSD (iRMSD) and fraction of native contacts (FN) provide specialized evaluation criteria [30].

Comparative Performance Data

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Based on CASP Assessments

| Performance Metric | Template-Based Modeling | Template-Free Modeling (AI) | Assessment Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average GDT_TS | 70-90 (high similarity templates) 40-70 (remote homology) | 80-95 (well-folded domains) | Single domain proteins |

| Sequence Identity Threshold | Requires >30% for reliable models | No minimum requirement | Method applicability |

| Model Accuracy Trend | Accuracy decreases with lower template identity | Consistently high across diverse folds | Broad benchmark |

| Complex Structure Prediction | Limited to components with templates | Moderate to high accuracy (AlphaFold3) | Protein-protein complexes |

| Flexible Regions | Poor accuracy in loops and inserts | Moderate accuracy, often underconfident | Dynamic segments |

| Multimeric Assemblies | Manual docking required | Emerging capabilities (AlphaFold3) | Quaternary structure |

Experimental Protocols and Method Implementation

Template-Based Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental protocol for template-based modeling:

Step 1: Template Identification – The target sequence is scanned against structural databases (PDB, Phyre2 library) using sequence comparison tools (BLAST, HHblits) to identify potential templates with significant sequence similarity or compatible folds [28] [29].

Step 2: Sequence Alignment – Optimal alignment between the target and template sequences is generated, accounting for mutations, insertions, and deletions. This alignment forms the foundation for mapping target residues to template positions [28].

Step 3: Backbone Construction – Coordinates from the template structure are transferred to the target sequence according to the sequence alignment, preserving the overall structural framework of the template [29].

Step 4: Loop Modeling – Regions with insertions or deletions (indels) relative to the template are modeled using fragment libraries from known structures or de novo generation techniques [29].

Step 5: Side-chain Placement – Side-chain conformations are predicted using rotamer libraries and optimization algorithms (e.g., SCWRL4) to minimize steric clashes and maximize favorable interactions [29].

Step 6: Model Refinement – Energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations are applied to relieve atomic clashes and improve stereochemistry [28].

Step 7: Quality Assessment – The final model is evaluated using geometric validation tools (MolProbity), energy functions, and comparison to experimental data when available [28] [29].

Template-Free Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental protocol for template-free modeling:

Step 1: Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Generation – The target sequence is aligned against large sequence databases (UniRef, MGnify) to identify homologous sequences and evolutionary coupling patterns [28].

Step 2: Feature Extraction – The MSA and target sequence are processed to extract features including position-specific scoring matrices, secondary structure predictions, and co-evolutionary signals [28].

Step 3: Neural Network Processing – Deep learning architectures (e.g., Evoformer in AlphaFold2, language models in ESMFold) process the input features to predict spatial relationships including distances, angles, and torsion angles [28] [30].

Step 4: Geometric Constraint Implementation – The predicted spatial restraints are converted into potential functions or directly into 3D atomic coordinates through specialized structure modules [28].

Step 5: 3D Structure Generation – The network generates atomic coordinates through either gradient-based optimization or direct coordinate inference, building the protein structure according to the learned constraints [28].

Step 6: Relaxation and Scoring – The initial structure undergoes energy minimization to relieve steric clashes, with confidence scores (pLDDT) assigned to each residue to indicate prediction reliability [5] [30].

Table 3: Key Databases and Tools for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Structure Database | Provides >200 million pre-computed AlphaFold predictions | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [5] |

| AlphaSync | Structure Database | Continuously updated predicted structures with additional annotations | https://alphasync.stjude.org/ [31] |

| Phyre2.2 | Modeling Server | Template-based modeling with integrated AlphaFold template selection | https://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/ [29] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structure Database | Primary repository for experimentally determined structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ [28] [29] |

| UniProt | Sequence Database | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ [5] [31] |

| ColabFold | Modeling Server | Accessible implementation of AlphaFold2 for custom predictions | https://colabfold.com [29] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Performance Analysis and Limitations

The benchmarking data reveals a nuanced performance landscape. While template-free AI methods demonstrate superior overall accuracy in CASP assessments, particularly for single-domain proteins, template-based approaches maintain relevance in specific scenarios [30]. TBM excels when high-quality templates exist, often producing more physiologically relevant models for specific conformational states (e.g., apo/holo forms) that may be underrepresented in AI training data [29]. Modern implementations like Phyre2.2 have adapted by incorporating AlphaFold predictions as potential templates, creating hybrid workflows that leverage the strengths of both approaches [29].

Both methodologies face fundamental challenges in capturing protein dynamics and conformational heterogeneity. The static nature of structural models, whether template-based or template-free, provides limited insight into the ensemble nature of protein structures in solution [27]. This limitation is particularly significant for intrinsically disordered regions, allosteric mechanisms, and conformational changes – areas where both approaches struggle to provide biologically complete representations [27]. Additionally, AI-based TFM methods show diminished accuracy for proteins with limited evolutionary information or unusual folds that are underrepresented in training datasets [28] [27].

Practical Implementation Considerations

For researchers selecting between these approaches, several practical considerations emerge. Template-based modeling offers greater interpretability and manual control, allowing experts to incorporate biological knowledge about specific conformational states or functional requirements [29]. The computational requirements for TBM are generally modest compared to the substantial resources needed for training and running large neural networks, though pre-computed databases like AlphaFold DB and AlphaSync have dramatically improved accessibility [5] [31].

Template-free methods provide broader coverage of protein fold space and have largely automated the prediction process, making high-quality structures accessible to non-specialists [28] [5]. However, the black-box nature of deep learning models can complicate result interpretation, and the field continues to address challenges including model confidence calibration, representation of uncertainty, and ethical implementation as these powerful tools become increasingly central to biological research and therapeutic development [27].

The computational shift from template-based to template-free modeling represents a paradigm change in structural bioinformatics, with deep learning approaches establishing new standards for accuracy and accessibility. However, template-based methods continue to offer unique advantages for specific applications, particularly when experimental knowledge of specific conformational states exists. The evolving landscape is characterized by convergence rather than replacement, with hybrid systems increasingly blurring the distinction between these approaches.

Future directions will likely focus on integrating both methodologies within unified frameworks that leverage their complementary strengths while addressing their shared limitations in representing dynamic structural ensembles. As the field progresses beyond single static structures toward predictive models of conformational dynamics and functional mechanisms, the synergy between template-based knowledge and template-free innovation will continue to drive advances in both basic research and therapeutic development.

The field of structural biology has undergone a revolutionary transformation through the integration of deep learning, fundamentally altering how researchers approach the decades-old "protein folding problem." For over 50 years, predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence remained one of the most significant challenges in molecular biology [1]. Traditional experimental methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy, while invaluable, are often time-consuming, expensive, and limited by protein complexity [32]. The advent of artificial intelligence has dismantled these barriers, enabling computational methods to achieve accuracy competitive with experimental techniques and providing insights into previously intractable biological questions [1] [32].

This breakthrough is particularly impactful for drug discovery and development, where understanding protein structure is crucial for elucidating function and designing targeted therapies [33] [32]. The ability to accurately predict structures for the vast number of proteins with unknown experimental structures opens new frontiers for understanding biological mechanisms, designing novel enzymes, and developing personalized medicines [32]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the leading AI-driven protein structure prediction tools, evaluating their performance, technical capabilities, and practical applications for the scientific community.

Methodological Breakdown of Major AI Systems

Core Architectural Innovations

The breakthrough in prediction accuracy stems from novel neural network architectures that integrate evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints of protein structures.

AlphaFold2's Evoformer and Structure Module: AlphaFold2 introduced a completely redesigned architecture featuring two key components. The Evoformer is a novel neural network block that processes inputs through attention-based mechanisms to generate both a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) representation and a pair representation [1]. This enables the network to reason about evolutionary relationships and spatial constraints simultaneously. The Structure Module then introduces an explicit 3D structure, rapidly refining it from an initial state to a highly accurate atomic model with precise side-chain positioning [1]. A critical innovation is "recycling," where outputs are recursively fed back into the same modules for iterative refinement, significantly enhancing accuracy [1].

RoseTTAFold's Three-Track Network: Developed by David Baker's lab, RoseTTAFold employs a three-track architecture that simultaneously processes information on one-dimensional (sequence), two-dimensional (distance maps), and three-dimensional (spatial coordinates) levels [32]. This design allows information to flow back and forth between different dimensional representations, enabling the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates. The system achieves performance comparable to AlphaFold2 while offering flexibility for various modeling challenges [32].

ESMFold's Language Model Approach: Meta's ESMFold represents a paradigm shift by eliminating the need for multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). Instead, it uses a protein language model (pLM) trained on millions of protein sequences to predict structure directly from single sequences [33]. This approach leverages patterns learned from evolutionary relationships embedded in the language model weights, resulting in significantly faster predictions (up to 60 times faster than AlphaFold2 for short sequences) while maintaining respectable accuracy, though generally lower than MSA-dependent methods [33].

Evolution to Biomolecular Complexes

The latest generation of prediction tools has expanded capabilities beyond single proteins to model complex biomolecular interactions.

AlphaFold3: This iteration extends predictions to a broad range of biomolecules, including proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and post-translational modifications [34]. AlphaFold3 incorporates an improved Evoformer module and utilizes a diffusion network similar to those used in AI image generation, which helps in generating more accurate complex structures [32] [34]. This represents a significant advancement for drug discovery where understanding protein-ligand interactions is crucial.

RoseTTAFold All-Atom (RFAA): Similarly, RFAA can model full biological assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, and covalent modifications [32]. Trained on diverse complexes from the PDB, RFAA provides researchers with a comprehensive tool for studying molecular interactions, described by one researcher as "like switching from black and white to a colour TV" [32].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of Major AI Prediction Tools

| Tool | Primary Innovation | Input Requirements | Key Architectural Features | Output Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Evoformer & Structure Module | Amino acid sequence + MSA | Attention mechanisms, iterative recycling, template integration | Single-chain proteins, per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT) |

| RoseTTAFold | Three-track network (1D+2D+3D) | Amino acid sequence + MSA | Information integration across dimensional tracks, flexible architecture | Single-chain proteins, protein-protein interactions |

| ESMFold | Protein language model (pLM) | Single amino acid sequence only | Transformer-based sequence embeddings, no MSA requirement | Fast single-chain predictions, orphan protein structures |

| AlphaFold3 | Generalized biomolecular modeling | Sequence + molecular composition | Diffusion-based refinement, expanded Evoformer | Proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, modifications, complexes |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Comprehensive assembly modeling | Sequences + molecular components | Three-track architecture adapted for all atom types | Full biological assemblies with diverse components |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

CASP14: The Watershed Moment

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments serve as the gold-standard blind assessment for protein structure prediction methods. The 14th CASP competition in 2020 marked a turning point where AI-based methods demonstrated unprecedented accuracy [1].

AlphaFold2's Dominant Performance: AlphaFold2 achieved a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD95, approaching the width of a carbon atom (approximately 1.4 Å) and vastly outperforming the next best method, which had a median backbone accuracy of 2.8 Å RMSD95 [1]. In all-atom accuracy, AlphaFold2 reached 1.5 Å RMSD95 compared to 3.5 Å RMSD95 for the best alternative method [1]. The system demonstrated remarkable capability with long proteins, accurately predicting the structure of a 2,180-residue protein with no structural homologs [1].

Independent Validation: Subsequent validation against recently released PDB structures confirmed that AlphaFold2's high accuracy extends beyond the CASP14 proteins to a broad range of structures, with reliable per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT) that accurately predict local accuracy [1]. This transferability demonstrated the generalizability of the approach and its readiness for broad scientific application.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from CASP14 and Independent Studies

| Tool | Backbone Accuracy (Median Cα RMSD95) | All-Atom Accuracy (RMSD95) | Reference for Performance Data | Notable Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.96 Å | 1.5 Å | [1] | Competitive with experimental structures in majority of cases |

| RoseTTAFold | Similar to AlphaFold2 (CASP14) | Similar to AlphaFold2 (CASP14) | [32] | Comparable accuracy to AlphaFold2, excels at certain protein classes |

| ESMFold | Lower than AlphaFold2 (with MSA) | Lower than AlphaFold2 (with MSA) | [33] | 60x faster than AlphaFold2 for short sequences, reduced accuracy |

| DMPFold2 | Lower than AlphaFold2 | Lower than AlphaFold2 | [35] | 100x faster than AlphaFold2 on GPUs, suitable for high-throughput |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Rigorous benchmarking of protein structure prediction methods follows standardized protocols to ensure fair comparison and biological relevance.

CASP Assessment Protocol: The CASP experiments utilize blind prediction where recently solved structures that haven't been deposited in the PDB are used as targets [1]. This prevents methods from being trained on or having prior knowledge of the test structures. Participants submit their predictions, which are then compared to the experimental structures using metrics like Global Distance Test (GDT) and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) [1] [36].

Accuracy Metrics and Interpretation: Key metrics for evaluating prediction quality include:

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): A local superposition-free score that estimates the reliability of individual residues [1].

- Predicted lDDT (pLDDT): AlphaFold's internally calculated confidence measure that correlates strongly with actual accuracy [1].

- Template Modeling Score (TM-score): A metric for measuring global structural similarity, with values above 0.5 indicating generally correct topology [1].

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between equivalent atoms after optimal superposition, with lower values indicating better accuracy [1].

Diagram 1: Protein Structure Prediction Workflow (11 words)

Practical Implementation and Resource Considerations

Hardware Requirements and Performance Scaling

Practical implementation of these tools requires careful consideration of computational resources, with significant variations between different methods.

AlphaFold2 Hardware Profile: According to benchmarks from Exxact Corporation, AlphaFold2 shows limited scalability across multiple GPUs, with similar performance observed using 1, 2, or 4 GPUs [37]. However, the addition of any GPU provides approximately 5x speedup compared to CPU-only execution [37]. Surprisingly, different GPU models (tested with RTX A4500 and higher-performance RTX 6000 Ada) showed nearly identical performance, suggesting the algorithm isn't limited by raw GPU compute power but by other architectural factors [37].

ESMFold and DMPFold2 Efficiency: For researchers prioritizing speed over maximal accuracy, alternatives like ESMFold and DMPFold2 offer significantly faster performance. ESMFold achieves its speed by eliminating the computationally expensive MSA generation step, while DMPFold2 uses a more efficient neural network architecture that can run effectively on CPUs once the input MSA is generated [33] [35]. DMPFold2 is roughly two orders of magnitude faster than AlphaFold2 in head-to-head comparisons on GPUs [35].

Accessibility and Usage Modalities

The accessibility of these powerful tools varies significantly, impacting their adoption across different research environments.

Databases vs. Local Tools: For many applications, researchers can leverage pre-computed databases rather than running predictions locally. The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, a collaboration between DeepMind and EMBL-EBI, provides open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions [5]. This is particularly valuable for drug discovery pipelines where protein structure serves as the starting point for a given disease-target pair and doesn't need repeated prediction [33].

Access Restrictions and Open Alternatives: The release of AlphaFold3 sparked controversy as it was initially published without source code or weights, a departure from the open access provided with AlphaFold2 [32] [34]. This prompted development of fully open-source initiatives like OpenFold, which provides a trainable implementation of AlphaFold2 [32] [34], and Boltz-1 [34]. Similarly, while RoseTTAFold All-Atom code is MIT-licensed, its trained weights are only available for non-commercial use [34]. This landscape underscores the tension between proprietary development and open scientific progress.

Table 3: Practical Implementation and Resource Requirements

| Tool | Access Mode | Hardware Requirements | Typical Runtime | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Open source code + database | High-end GPU recommended | Minutes to hours (protein-dependent) | Highest accuracy single-chain predictions, research publications |

| AlphaFold3 | Limited webserver (non-commercial) | Not applicable (cloud-based) | Variable (server queue) | Biomolecular complexes, protein-ligand interactions |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Code: MIT License, Weights: non-commercial | High-end GPU recommended | Minutes to hours | Biomolecular assemblies, complex structures |

| ESMFold | Open source | Moderate GPU/CPU | Seconds to minutes | High-throughput screening, orphan proteins, antibody design |

| DMPFold2 | Open source | CPU or GPU | Seconds to minutes | Proteome-scale analysis, educational use, rapid prototyping |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing protein structure prediction in research requires both computational and data resources. Below are essential components for establishing a capable structural bioinformatics pipeline.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | Data Input | Provides evolutionary constraints for MSA-dependent tools | JackHMMER, MMseqs2 [1] |

| Structure Prediction Servers | Computational Tool | Web-based access without local installation | AlphaFold Server, RoseTTAFold Server [32] |

| Pre-computed Structure Databases | Data Repository | Access to pre-calculated predictions for known sequences | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [5] |

| Molecular Visualization Software | Analysis Tool | Visualization and analysis of predicted structures | ChimeraX, PyMOL [5] |

| Domain Segmentation Tools | Analysis Tool | Identifying structural domains in predicted models | Merizo (deep learning-based domain segmentation) [35] |

| Confidence Metrics | Quality Assessment | Evaluating prediction reliability at residue and global levels | pLDDT, pTM [1] |

The field of AI-powered protein structure prediction continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. As we look toward 2025 and beyond, key developments include increased focus on biomolecular complex prediction, the rise of open-source alternatives to proprietary models, and improved speed and accessibility for broader research communities [34].

The controversy surrounding AlphaFold3's limited release has stimulated development of fully open-source initiatives like OpenFold and Boltz-1, which aim to provide similar capabilities without usage restrictions [34]. Concurrently, established tools continue to expand their capabilities, with RoseTTAFold All-Atom demonstrating impressive performance on diverse biomolecular assemblies [32]. For researchers, the choice of tool increasingly depends on specific application requirements—whether prioritizing maximal accuracy (AlphaFold2), biomolecular complexes (AlphaFold3, RoseTTAFold All-Atom), or prediction speed (ESMFold, DMPFold2) [33] [35].

As these technologies mature, their integration into drug discovery pipelines and basic research will continue to accelerate, potentially reducing dependency on traditional experimental methods for initial structure determination. However, experimental validation remains crucial for confirming novel predictions, particularly for therapeutic applications where small structural errors can have significant implications. The ongoing collaboration between computational and experimental structural biology promises to further our understanding of biological mechanisms and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

A Practical Guide to Modern Protein Structure Prediction Servers and Tools

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of leading protein structure prediction systems—AlphaFold (including its variants AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3), AlphaFold-Multimer, DeepSCFold, and MULTICOM. It synthesizes data from independent benchmark studies to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate tools for their specific applications.

Performance Comparison of Prediction Systems

This section compares the core performance metrics of the featured prediction systems across different structure prediction tasks, from single chains to complex multimers.

Performance Metrics for Monomer and Complex Prediction

Table 1: Key performance metrics for monomer and protein complex structure prediction.

| Prediction System | Primary Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Performance | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [38] [39] | Single-chain proteins (Monomers) | RMSD, TM-score, pLDDT | Near X-ray resolution in CASP14; RMSD of 0.33Å for short loops (<10 residues) [38] | High accuracy for most monomer structures; excellent for short, structured regions. |

| AlphaFold3 [40] | Protein-protein & protein-ligand complexes | ipTM, Pearson Correlation (Rp), RMSE | Rp of 0.86 for predicting binding free energy changes; ipTM >0.8 indicates high confidence [40] | Broad applicability to complexes including proteins, DNA, and RNA. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [41] | Protein complexes (Multimers) | DockQ score, TM-score | Foundation for many complex prediction benchmarks and datasets [41] | Designed specifically for multimeric protein complexes. |

| MULTICOM4 [42] | Protein complexes (Multimers) | TM-score, DockQ score | TM-score of 0.797 and DockQ of 0.558 in CASP16 Phase 1 [42] | Integrates multiple AI engines; superior model ranking and handling of complex stoichiometry. |

Performance on Specific Structural Elements

Table 2: Performance of AlphaFold2 on specific peptide and loop structures.

| Structure Type | System | Performance | Specific Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Loops (≤10 residues) [38] | AlphaFold2 | High accuracy (Avg. RMSD: 0.33 Å; Avg. TM-score: 0.82) | --- |

| Long Loops (>20 residues) [38] | AlphaFold2 | Reduced accuracy (Avg. RMSD: 2.04 Å; Avg. TM-score: 0.55) | Accuracy decreases with increased length and flexibility. |

| Peptides (α-helical, β-hairpin, disulfide-rich) [39] | AlphaFold2 | High accuracy, outperforms dedicated peptide prediction tools | Shortcomings in predicting Φ/Ψ angles and disulfide bond patterns. |

| Flexible Complex Regions [40] | AlphaFold3 | Unreliable predictions | Not reliable for intrinsically flexible regions or domains. |

Benchmarking Experiments and Protocols

Independent validation is crucial for assessing the real-world performance and limitations of these AI-driven tools. The following outlines common benchmarking methodologies.

Key Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

Dataset Curation: Benchmarks rely on curated datasets of protein structures with known experimental coordinates (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB).

- For monomer/loop assessment: A dataset of 31,650 loop regions from 2,613 proteins was used to test AlphaFold2, ensuring proteins were deposited after AlphaFold2's training to prevent data leakage [38].

- For complex assessment: The SKEMPI 2.0 database, containing 317 protein-protein complexes and 8,338 mutations, is a standard for evaluating protein-protein interaction (PPI) predictions [40].

- For peptide assessment: A benchmark of 588 peptide structures (10-40 amino acids) with experimentally determined NMR structures was used [39].

Structure Prediction and Generation: The target system (e.g., AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3) is used to predict the structures for the sequences in the benchmark dataset. In truly blind tests like CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction), predictors generate models before the experimental structures are publicly available [41].

Structure Alignment and Metric Calculation: Each predicted structure is aligned to its corresponding experimental structure.

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between atoms (e.g., Cα atoms) of the aligned structures. Lower values indicate better accuracy [38].