Benchmarking Protein Structure Prediction Tools: From Monomeric Accuracy to Complex Challenges in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of modern protein structure prediction tools, addressing critical needs for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Benchmarking Protein Structure Prediction Tools: From Monomeric Accuracy to Complex Challenges in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of modern protein structure prediction tools, addressing critical needs for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles underpinning AI-driven structure prediction, evaluate methodological approaches for single-chain and complex structures, identify key challenges and optimization strategies, and establish rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing findings from recent benchmarking studies and Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, this review offers practical guidance for tool selection while highlighting persistent gaps in predicting multi-chain complexes, dynamic conformations, and functionally relevant structural features essential for drug discovery applications.

The Protein Structure Prediction Revolution: From AlphaFold Breakthroughs to Current Landscape

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, biennial blind experiment established to objectively assess the state of the art in predicting protein 3D structure from amino acid sequence [1]. Since 1994, CASP has served as the gold-standard benchmark for the field, providing rigorous testing through targets whose experimental structures are known but not yet public [2] [3]. The fundamental challenge, often referred to as the "protein folding problem," has been to computationally achieve atomic-level accuracy—a goal that had remained elusive for five decades despite intensive research [4] [5].

The fourteenth CASP experiment (CASP14), conducted in 2020, marked a historic turning point. The AlphaFold2 system developed by DeepMind demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental methods for the majority of targets, leading CASP organizers to declare the protein folding problem for single chains essentially "solved" [3] [6]. This paradigm shift has profound implications for structural biology, biomedical research, and drug development, establishing a new benchmark for what computational methods can achieve.

Quantitative Assessment: AlphaFold2's Unprecedented Accuracy in CASP14

In CASP14, AlphaFold2's performance substantially exceeded all competing methods. The official CASP assessment uses z-scores based on Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) for ranking, which measures the percentage of amino acid residues within a threshold distance from their correct positions [7] [5].

Table 1: CASP14 Final Group Rankings by Summed Z-Scores

| Group Rank | Group Code | Group Name | Domains Count | Sum Z-Score (>-2.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 427 | AlphaFold2 | 92 | 244.0 |

| 2 | 473 | BAKER | 92 | 90.8 |

| 3 | 403 | BAKER-experimental | 92 | 89.0 |

| 4 | 480 | FEIG-R2 | 92 | 72.5 |

| 5 | 129 | Zhang | 92 | 67.9 |

AlphaFold2 achieved a median domain GDTTS of 92.4 across all targets, with predictions exceeding GDTTS of 90 (considered competitive with experimental accuracy) for 58 out of 92 domains [8]. The system produced high-accuracy structures (GDT_TS > 70) for 87 domains [8]. This performance was unmatched, with AlphaFold2 scoring nearly three times higher than the next best group in summed z-scores [7].

Accuracy Across Target Difficulty Categories

CASP categorizes targets by difficulty, from TBM-easy (template-based modeling with clear templates) to FM (free modeling, with no detectable homology to known structures) [3]. Historically, accuracy sharply declined for more difficult targets, but AlphaFold2 dramatically reduced this gap.

Table 2: AlphaFold2 Performance by CASP14 Target Category

| Target Category | Description | Median GDT_TS | Performance Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBM-Easy | Straightforward template modeling | ~95 | Near-experimental accuracy |

| TBM-Hard | Difficult homology modeling | ~90 | Competitive with experiment |

| FM/TBM | Remote structural homologies | ~87 | High accuracy |

| FM | No detectable homology | ~85 | High accuracy |

The most remarkable aspect was AlphaFold2's performance on free modeling (FM) targets, where it achieved a median GDT_TS of 87.0 [5]. This demonstrated that the system could accurately predict structures even without evolutionary information from homologous proteins.

Atomic-Level Accuracy and Confidence Estimation

Beyond backbone accuracy, AlphaFold2 achieved unprecedented all-atom precision, including side-chain conformations. The all-atom accuracy was 1.5 Å RMSD₉₅ (root-mean-square deviation at 95% residue coverage) compared to 3.5 Å RMSD₉₅ for the best alternative method [4].

The system's internal confidence measure, predicted lDDT-Cα (pLDDT), reliably estimated the actual per-residue accuracy (lDDT-Cα) of predictions [8] [4]. This allowed researchers to identify regions of higher uncertainty within otherwise accurate structures.

The AlphaFold2 Architecture: Core Technical Innovations

AlphaFold2 represented a complete redesign from the CASP13 system, implementing a novel end-to-end deep neural network architecture that directly produces atomic-level protein structures from sequence data [8] [4].

The AlphaFold2 system processes multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and template structures through several specialized components to generate refined 3D coordinates.

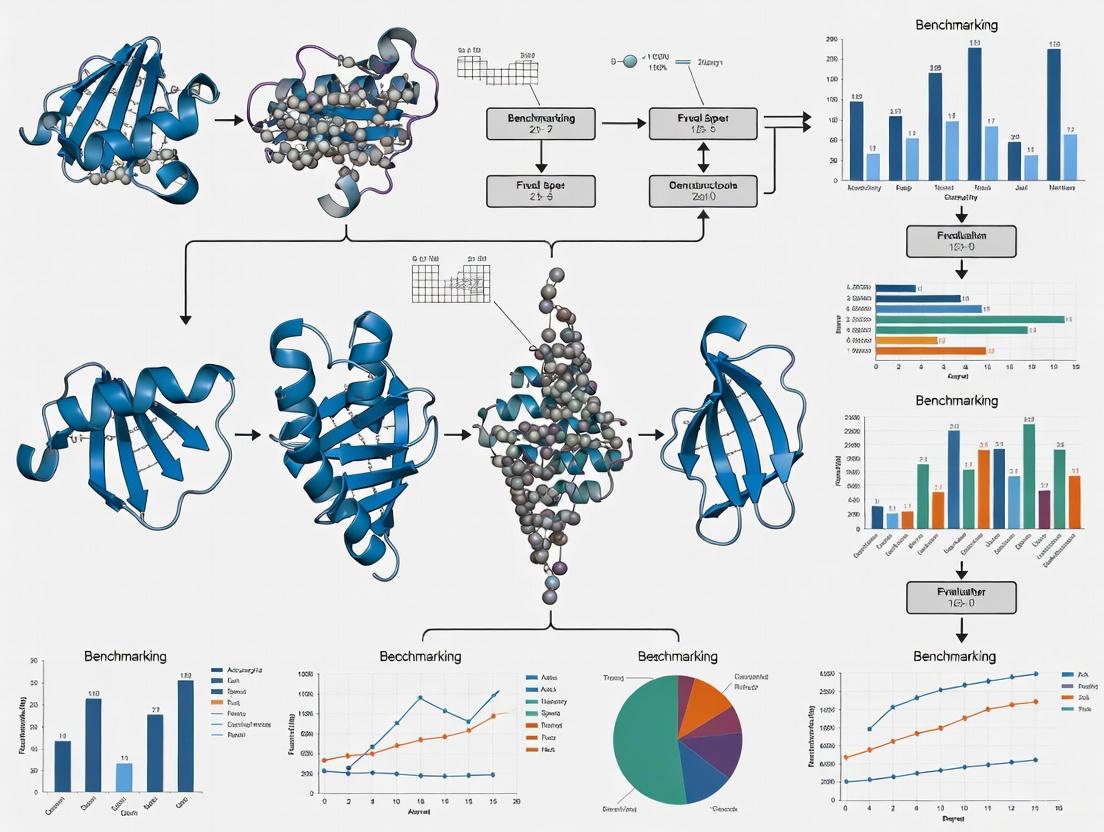

Diagram 1: AlphaFold2 End-to-End Architecture. The system processes sequence and evolutionary information through specialized modules to directly produce 3D atomic coordinates with confidence estimates.

Evoformer: Integrating Evolutionary and Structural Information

The Evoformer is a novel neural network block that constitutes the core of AlphaFold2's reasoning engine [4]. It jointly processes the MSA and pairwise residue representations through multiple attention mechanisms and update operations:

- MSA Representation: An Nseq × Nres array encoding evolutionary information across sequences

- Pair Representation: An Nres × Nres array encoding residue-residue relationships

- Triangular Attention: Self-attention mechanisms that enforce geometric constraints by considering triplets of residues

- Information Exchange: Continuous bidirectional information flow between MSA and pair representations

The Evoformer develops and refines a concrete structural hypothesis through its layers, enabling the system to reason about spatial and evolutionary relationships simultaneously [4].

Structure Module: From Representations to 3D Coordinates

The Structure Module generates explicit 3D atomic coordinates using a rotationally and translationally equivariant architecture [8] [4]. Key innovations include:

- Frame Representation: Each residue is represented as a rigid body frame (rotation and translation)

- Equivariant Transformers: Process the frame representations while preserving geometric symmetries

- Side-Chain Prediction: Implicit reasoning about unrepresented side-chain atoms

- Iterative Refinement: Repeated processing through "recycling" to progressively improve accuracy

The structure module is initialized with all residues at the origin but rapidly develops a highly accurate protein structure through multiple iterations [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CASP14 Assessment Protocol

The CASP14 experiment followed a rigorous blind assessment protocol [2] [3]:

- Target Selection: 52 proteins with recently solved but unpublished structures were provided as sequences

- Prediction Period: Participants had approximately three weeks to submit models

- Evaluation: Predictions were compared to experimental structures using metrics including GDT_TS, RMSD, and lDDT

- Categories: Targets were divided into difficulty categories based on similarity to known structures

AlphaFold2 Implementation and Training

AlphaFold2 was trained on publicly available data including ~170,000 structures from the Protein Data Bank and large databases of protein sequences with unknown structure [5]. The training process incorporated:

- Multi-task Learning: Joint training on structure, distograms, and pLDDT

- Recycling: Iterative refinement where outputs are fed back into the same modules

- Masked MSA Loss: Training on corrupted MSAs to improve robustness

- Physical Constraints: Incorporation of stereochemical knowledge through the structure module

The system used approximately 16 TPUv3s (equivalent to ~100-200 GPUs) over several weeks for training [5].

Model Selection and Ranking Strategy

For CASP14 submissions, AlphaFold2 employed a specific prediction protocol [8]:

- Multiple Predictions: Five models generated using different parameter sets

- Confidence Ranking: Models ranked by predicted lDDT (pLDDT)

- Template Clustering: For targets with conformational diversity (e.g., T1024), templates were clustered to generate structurally diverse predictions

- Relaxation: Gradient descent using Amber99sb to remove stereochemical violations

This approach ensured that the highest-confidence models were submitted while maintaining diversity where appropriate.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource/Component | Type | Function in Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides >200 million pre-computed structures for known protein sequences | Publicly available at alphafold.ebi.ac.uk [9] |

| Evoformer | Algorithm | Neural network architecture for joint processing of MSA and pairwise information | Open source code available [4] |

| Structure Module | Algorithm | Equivariant network for generating 3D atomic coordinates | Open source code available [4] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Data Input | Evolutionary information from homologous sequences | Generated from sequence databases (UniProt) [4] |

| pLDDT (predicted lDDT) | Metric | Per-residue confidence estimate for predictions | Generated by AlphaFold2 system [8] [4] |

| Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) | Assessment | Primary metric for overall structure accuracy | Used in CASP evaluation [1] [7] |

| Template Structures | Data Input | Known structures from PDB for homology information | Retrieved from Protein Data Bank [8] |

Case Study: T1024 - Handling Conformational Diversity

The prediction for target T1024 (active transporter LmrP) demonstrated AlphaFold2's capabilities and limitations when dealing with proteins exhibiting multiple conformations [8].

Initial Analysis and Challenges

Initial predictions for T1024 showed:

- High MSA coverage (5702 alignments) and good templates

- Low pLDDT in the linker region around residue 200, suggesting flexibility

- Lack of diversity in five initial predictions (all TM score >0.99 to one another)

- Unrealized inter-domain contacts in the expected distance matrix

Intervention Strategy

The AlphaFold team implemented a manual intervention to capture alternate conformations [8]:

- Template Clustering: Templates were clustered by conformational state (inward-facing vs. outward-facing)

- MSA Limitation: Reducing MSA to top 30 sequences to increase template influence

- Diverse Prediction Generation: Creating extra predictions using different template clusters

This case highlighted both the system's ability to detect uncertainty and the potential need for targeted interventions in complex cases.

Implications for Structural Biology and Drug Development

Immediate Applications and Validation

AlphaFold2 predictions have already proven valuable in practical structural biology:

- Molecular Replacement: Models successfully used to solve crystal structures through molecular replacement [10] [3]

- Membrane Proteins: Accurate predictions for challenging membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize [5]

- Structure Correction: Identification and correction of local errors in experimental structures [10]

Professor Andrei Lupas, a CASP assessor, noted that "AlphaFold's astonishingly accurate models have allowed us to solve a protein structure we were stuck on for close to a decade" [5].

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the breakthrough, AlphaFold2 has limitations that represent future research directions:

- Protein Complexes: Limited capability for predicting protein-protein interactions and complexes

- Dynamics: Does not capture conformational dynamics and multiple states

- Conditional Effects: Cannot model environmental influences on structure

- Ligand Interactions: Limited ability to predict binding sites and small molecule interactions

The CASP14 results represent a beginning rather than an endpoint, opening new research avenues in structural biology and computational biophysics [3] [6].

AlphaFold2's performance at CASP14 represents a paradigm shift from incremental progress to transformative accuracy. By achieving atomic-level precision competitive with experimental methods for most single-protein targets, the system has effectively solved the classical protein folding problem that stood for 50 years [4] [3].

This breakthrough was enabled by several key innovations: the Evoformer architecture for joint reasoning about evolutionary and structural information; an equivariant structure module for direct coordinate generation; and iterative refinement through recycling [8] [4]. The system's performance, with a median GDT_TS of 92.4 and overwhelming dominance in CASP14 assessment, establishes a new benchmark for the field [7] [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, AlphaFold2 and its open-access database provide immediate resources for structural insight, particularly for proteins resistant to experimental determination [9] [5]. As the methods continue to develop and address remaining challenges like complex prediction and conformational dynamics, the impact on biological research and therapeutic development is expected to grow substantially in the coming years.

The prediction of protein three-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences represents a cornerstone of modern computational biology. Accurate structural models provide an indispensable bridge between genomic information and biological function, enabling mechanistic insights at the molecular level. The field has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of deep learning-based methods, notably AlphaFold2, which achieve accuracy comparable to some experimental structure determination methods [11] [12]. This advancement has fundamentally altered the landscape of structural biology, providing researchers with unprecedented access to reliable protein models for diverse applications. These computed structure models (CSMs) have transitioned from theoretical curiosities to practical tools that drive discovery across biological disciplines, from fundamental biochemistry to applied drug design [12].

The utility of these predictions is systematically evaluated through community-wide initiatives such as the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP), which provides rigorous blind testing of methodology performance [13] [14]. As the accuracy and accessibility of prediction tools continue to improve, their integration into biological research workflows accelerates, enabling scientists to generate testable hypotheses about protein function, interaction networks, and molecular mechanisms underlying health and disease. This technical guide examines the key biological applications of protein structure prediction, focusing on the experimental validation protocols and quantitative benchmarks that establish their reliability for research and development.

Foundational Technologies and Methods

Modern protein structure prediction relies on two primary computational approaches: template-based modeling for sequences with recognizable homology to experimentally determined structures, and template-free modeling for novel folds [12]. The breakthrough in template-free modeling came from integrating evolutionary information derived from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) with deep learning architectures. AlphaFold2 implements an end-to-end deep neural network that simultaneously processes co-evolutionary information through a specialized transformer (Evoformer) and amino acid geometry through a structural module [11]. This approach leverages the observation that amino acids in close spatial proximity often exhibit correlated evolutionary patterns, allowing for accurate inference of residue-residue contacts [11] [15].

RoseTTAFold from the Baker group represents another significant advancement, producing predictions approaching AlphaFold2 accuracy [11]. Recently, protein language models such as ESMFold have demonstrated capability to predict structures from single sequences without explicit MSAs, potentially by memorizing motifs derived from co-evolutionary information during training [11]. For challenging targets with few homologs, ESMFold can sometimes outperform MSA-dependent methods [11].

The confidence of predicted models is typically quantified using per-residue local distance difference test (pLDDT) scores, which estimate the reliability of local structure predictions on a scale from 0 to 100 [12]. Regions with pLDDT > 70 are generally considered confident predictions, while lower scores may indicate unstructured regions or prediction uncertainties [12] [16]. For multimetric assemblies, methods like DeepSCFold have advanced complex structure prediction by incorporating sequence-derived structure complementarity and interaction probability metrics, demonstrating significant improvements in interface accuracy [17].

Table 1: Key Protein Structure Prediction Tools and Their Applications

| Tool | Methodology | Primary Application | Key Output | Confidence Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Deep learning with MSAs and structural modules | Monomeric protein structures | Atomic coordinates | pLDDT (0-100) |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Extension of AlphaFold2 for complexes | Multi-chain protein complexes | Atomic coordinates | pLDDT, interface score |

| RoseTTAFold | Deep learning with three-track architecture | Monomeric structures | Atomic coordinates | pLDDT |

| DeepSCFold | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | Protein complexes with low co-evolution | Atomic coordinates | TM-score, interface metrics |

| ESMFold | Protein language model without explicit MSAs | Structures with limited homologs | Atomic coordinates | pLDDT |

Key Biological Applications and Experimental Validation

Drug Design and Target Identification

Protein structure predictions have profound implications for structure-based drug design, particularly for targets lacking experimental structures. Accurate models of drug targets enable virtual screening of compound libraries, identification of binding pockets, and rational design of inhibitors with optimized interactions. The reliability of these applications depends on high-confidence predictions, particularly in binding sites and functional regions.

For the human dopamine transporter, homology modeling using the fruit fly structure as a template (55% sequence identity) generated a reliable CSM that highlighted structural differences in a key loop region [12]. This model provided insights for inhibitor design despite variations in loop length between species. Similarly, for the Kir7.1 potassium channel, a disease-associated mutant (T153I) was modeled to understand its impact on potassium conduction, revealing how the mutation within the inner pore affects ion transport [18]. These examples demonstrate how CSMs bridge structural information between homologs to facilitate drug discovery.

Functional Annotation of Proteins and Domains

A primary application of structure prediction is the functional annotation of proteins of unknown function. Structural similarity often reveals functional relationships even in the absence of sequence similarity, enabling transfer of functional insights from well-characterized proteins to unannotated ones.

The application to centrosomal and centriolar proteins exemplifies this approach. For CEP44, a protein with essential roles in centrosome and centriole biogenesis, AF2 predicted a Calponin Homology (CH) domain structure with remarkable accuracy (RMSD 0.74 Å compared to subsequent experimental structure) [16]. The prediction revealed a conserved basic patch on the domain surface, which subsequent mutagenesis confirmed as essential for microtubule and centriole association [16]. Similarly, for CEP192, AF2 correctly predicted the structure of its Spd2 domain, including a unique 60-residue insertion that defines a cradle-like conformation critical for function [16]. In both cases, the predictions provided insights years before experimental structures were determined.

Elucidating Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

Understanding cellular function requires knowledge of how proteins assemble into complexes. Predicting the structures of protein-protein interactions remains challenging but has seen significant advances. DeepSCFold, for instance, uses sequence-based deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability, constructing deep paired multiple-sequence alignments for complex structure prediction [17].

This approach proved particularly valuable for elucidating the Chibby1-FAM92A complex, for which no structural information was previously available [16]. The prediction enabled hypothesis-driven experiments that validated the interaction and provided insights into its regulatory mechanism. Similarly, AF2 predictions elucidated previously unknown features in the structure of TTBK2 bound to CEP164, with important implications for understanding the regulation and function of this complex in centriole biology [16]. For antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, DeepSCFold enhanced the prediction success rate for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [17].

Characterization of Disease Mutations

Protein structure models enable mechanistic interpretation of genetic variations by mapping mutations to structural contexts. This approach helps distinguish pathogenic mutations from benign polymorphisms by assessing their potential to disrupt protein stability, interaction interfaces, or functional sites.

In the Src oncoprotein, CSMs reveal a multi-domain architecture with flexible regions that adopt different conformations in active versus inactive states [12]. The C-terminal tail contains a key tyrosine residue (Tyr-529) whose phosphorylation status regulates activity through conformational changes [12]. Modeling disease-associated mutations in this context provides insights into how they might alter regulatory mechanisms. Similarly, for the HINT1 protein associated with axonal motor neuropathy, structural predictions facilitated understanding of its function as a zinc- and calmodulin-regulated cysteine SUMO protease [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarks of Prediction Tools for Biological Applications

| Application Domain | Evaluation Metric | AlphaFold2 | AlphaFold-Multimer | DeepSCFold | ESMFold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer Structures | TM-score (CASP15) | 0.89 | - | - | 0.79 |

| Protein Complexes | TM-score (CASP15) | - | 0.76 | 0.85 | - |

| Antibody-Antigen Interfaces | Success Rate (%) | - | 68.3 | 85.9 | - |

| Challenging Targets | Improvement over AF2 | - | - | +11.6% TM-score | Varies |

| Prediction Speed | Sequences/day | ~100 | ~50 | ~40 | ~1000 |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

X-ray Crystallography Verification

Purpose: To experimentally validate the accuracy of predicted protein structures and provide atomic-level insights into functional mechanisms.

Methodology:

- Protein Expression and Purification: Clone the gene of interest into an appropriate expression vector. Express the protein in a suitable system (e.g., E. coli, insect cells). Purify using affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography [16].

- Crystallization: Screen crystallization conditions using commercial screens. Optimize initial hits. For CEP44 CH domain and CEP192 Spd2 domain, crystals were obtained at 20°C using sitting-drop vapor diffusion [16].

- Data Collection and Structure Determination: Collect X-ray diffraction data at synchrotron sources. For CEP44: 2.3 Å resolution, experimentally phased. For CEP192 Spd2: 2.1 Å resolution, experimentally phased [16].

- Model Building and Refinement: Build atomic models into electron density maps. Refine using phenix.refine or similar software [16].

- Validation: Compare experimental structures with predictions using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculations. For CEP44 CH domain: 116 residues superposed with RMSD of 0.74 Å. For CEP192 Spd2: 273 residues superposed with RMSD of 1.83 Å [16].

Functional Characterization Through Mutagenesis

Purpose: To validate functional insights derived from predicted structures by assessing the consequences of targeted mutations.

Methodology:

- Identification of Functional Regions: Analyze predicted structures to identify conserved surface patches, potential binding sites, or critical structural elements [16].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Design mutants to disrupt identified regions. For CEP44, mutate residues constituting the conserved basic patch (K41, R45, R79, R105) to alanine [16].

- Functional Assays: Assess the functional consequences of mutations. For CEP44, evaluate microtubule and centriole association through immunofluorescence and binding assays [16].

- Interpretation: Correlate structural features with functional data. For CEP44, mutations in the basic patch abolished microtubule binding, validating the functional importance of the predicted region [16].

Protein-Protein Interaction Validation

Purpose: To experimentally confirm predicted protein complexes and interaction interfaces.

Methodology:

- Complex Prediction: Use tools like AlphaFold-Multimer or DeepSCFold to predict the structure of protein complexes [17] [16].

- Interaction Assays: Validate predictions using co-immunoprecipitation, pull-down assays, or surface plasmon resonance [16].

- Interface Mutagenesis: Design mutations at predicted interface residues and test their impact on binding affinity [16].

- Functional Consequences: Assess how disrupting the interface affects biological function. For TTBK2-CEP164 and Chibby1-FAM92A complexes, validation provided insights into their regulation and function in centriole biology [16].

Workflow for protein structure prediction validation and application

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction Servers | NovaFold AI, NovaFold AI-Multimer, NovaFold AI Boltz | AI-based structure prediction | Monomeric and multimeric protein structure prediction |

| Protein Sequence Databases | UniRef30/90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify | Provide evolutionary information for MSAs | Input for co-evolutionary analysis in AlphaFold2 |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database, ModelArchive | Repository of experimental and predicted structures | Template-based modeling, comparative analysis |

| Specialized Resources | Big Fantastic Virus Database, Viro3D, SAbDab | Domain-specific structural information | Virus proteins, antibody-antigen complexes |

| Model Quality Assessment | DeepUMQA-X, pLDDT, TM-score | Evaluate prediction reliability | Model selection, confidence estimation |

| Visualization & Analysis | Protean 3D, NGLView, Biopython | 3D structure visualization and manipulation | Structural analysis, figure preparation |

| Experimental Validation | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, SPR, Mutagenesis kits | Experimental verification of predictions | Benchmarking and validating computational models |

Protein structure prediction has evolved from a challenging computational problem to a practical tool that drives biological discovery. The applications spanning drug design, functional annotation, protein-protein interactions, and disease characterization demonstrate the transformative impact of these technologies on biomedical research. As benchmarked through rigorous experimental validation, the accuracy of leading prediction tools now supports their integration into standard research workflows.

Future advancements will likely address current limitations, particularly for multimeric assemblies, flexible regions, and interactions with nucleic acids and small molecules. Emerging methods like DeepSCFold show promise in capturing structural complementarity beyond sequence co-evolution, offering improved performance for challenging targets such as antibody-antigen complexes [17]. The continued growth of experimental structures in the PDB and sequence databases will further enhance prediction accuracy, enabling even broader applications in structural biology and drug development.

For researchers, the key to successful application lies in understanding both the capabilities and limitations of these tools. Critical assessment of pLDDT scores, experimental validation when possible, and integration with complementary biochemical and biophysical approaches remain essential for deriving biologically meaningful insights from predicted structures. As the field continues to advance, protein structure prediction will increasingly serve as a fundamental technology bridging genomic information and biological function across diverse research applications.

The field of protein structure prediction has been revolutionized by the advent of sophisticated computational methods, particularly deep learning-based approaches. Independent, blind assessment is fundamental for establishing the state-of-the-art, identifying methodological limitations, and guiding future research and development [19]. The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments serve as the primary community-wide benchmark for the field, providing a rigorous, biennial evaluation of the accuracy of protein structure modeling methods based on amino acid sequence [10] [2]. These experiments are complemented by platforms like the Continuous Automated Model EvaluatiOn (CAMEO), which provides weekly, automated benchmarking of publicly available prediction servers, ensuring ongoing assessment between CASP rounds [19]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these frameworks is essential for critically evaluating the tools they may employ in their work. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the evolution, current state, and methodologies of these crucial assessment frameworks, contextualized within the broader landscape of benchmarking protein structure prediction tools.

The CASP Experimental Framework: Methodology and Evolution

Core Principles and Design

Since its inception in 1994, the fundamental design of CASP has been a blind prediction experiment. Organizers release amino acid sequences of proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but are not yet publicly available. Predicting groups worldwide submit their models, which are subsequently compared to the experimental reference structures by independent assessors [10] [2]. This blind design prevents bias and ensures a fair evaluation of a method's true predictive power. CASP has historically been a biennial experiment, with CASP16 scheduled for 2024 [10]. The assessment covers multiple categories of modeling, reflecting the different challenges in the field, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Prediction Categories in Recent CASP Experiments

| Category | Focus of Assessment | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| High Accuracy (HA) | Accuracy of models on domains where high accuracy is achievable [2]. | GDTTS, GDTHA |

| Topology (TO) | Accuracy of models for difficult targets with low accuracy [2]. | GDT_TS |

| Assembly | Accuracy in modeling domain-domain, subunit-subunit, and protein-protein interactions (a.k.a. quaternary structure) [10] [2]. | Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1), LDDTo |

| Refinement | Ability to improve the accuracy of near-native models [10] [2]. | GDT_TS improvement |

| Contact/Distance Prediction | Accuracy in predicting inter-residue contacts and distances [2]. | Precision |

| Accuracy Estimation | Reliability of model quality scores provided by predictors [2]. | Correlation between predicted and observed scores |

| Biological Relevance | Usefulness of models in answering biologically meaningful questions [2]. | Target provider-defined questions |

Quantifying Progress: Key Performance Metrics

The CASP assessment relies on robust, quantitative metrics to evaluate and compare submitted models. The Global Distance Test (GDT) is a central metric, expressed as GDTTS (Total Score) and GDTHA (High Accuracy). GDTTS estimates the average percentage of Cα atoms in the model that can be superimposed on the corresponding atoms in the experimental structure within a defined distance cutoff (typically 1, 2, 4, and 8 Å) [10]. A higher GDTTS indicates a more accurate model, with scores above ~90 considered competitive with experimental methods for many applications [10]. The Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT) is another key metric, a superposition-free score that evaluates local distance differences of atoms in a model, making it particularly useful for assessing models of multi-chain complexes [10]. For the Assembly category, the Interface Contact Score (ICS or F1) is used, which measures the precision and recall of inter-chain residue contacts in the model compared to the native structure [10].

The progression of these metrics across CASP experiments reveals the dramatic advances in the field. As shown in Table 2, the introduction of deep learning, particularly AlphaFold2, marked a step-change in performance.

Table 2: Evolution of Model Accuracy in CASP (Selected Highlights)

| CASP Edition (Year) | Key Methodological Development | Representative Performance Leap |

|---|---|---|

| CASP4 (2000) | Early ab initio modeling | First reasonable accuracy for small proteins (<120 residues) [10]. |

| CASP11 (2014) | Utilization of predicted contacts | First accurate model of a larger new fold protein (256 residues) [10]. |

| CASP13 (2018) | Advanced deep learning for contact/distance prediction | Average GDT_TS for free modeling targets increased from 52.9 (CASP12) to 65.7 [10]. |

| CASP14 (2020) | AlphaFold2 (end-to-end deep learning) | ~2/3 of targets reached GDTTS >90 (competitive with experiment); high accuracy (GDTTS>80) for ~90% of targets [10]. |

| CASP15 (2022) | Extension of deep learning to multimers | Accuracy of multimer models almost doubled in ICS and increased by 1/3 in LDDTo compared to CASP14 [10]. |

Complementary Benchmarking Platforms

The CAMEO Platform

The Continuous Automated Model EvaluatiOn (CAMEO) platform operates as a crucial complement to the biennial CASP experiments. CAMEO performs weekly, fully automated evaluations of protein structure prediction servers that are publicly accessible. Its continuous nature allows for real-time tracking of method performance on a larger set of targets, providing a valuable dynamic view of the field's progress [19]. CAMEO has also been extended to benchmark methods for predicting macromolecular complexes, mirroring the expanding scope of CASP [19].

Benchmarking Specific Challenges

Specialized benchmarks have emerged to stress-test predictors in specific areas. For instance, the performance on peptide structures (typically 10-40 amino acids) has been systematically investigated using experimentally determined NMR structures as a reference. One such study benchmarked AlphaFold2 on 588 peptides across categories like α-helical membrane-associated, β-hairpin, and disulfide-rich peptides, finding high accuracy for α-helical and disulfide-rich peptides but shortcomings in predicting Φ/Ψ angles and disulfide bond patterns in some cases [20]. Similarly, the SPIRED method, a lightweight single-sequence predictor, was recently evaluated on CASP15 and CAMEO targets, achieving a TM-score of 0.786 on the CAMEO set, comparable to other state-of-the-art single-sequence methods like OmegaFold [21].

Quantitative Performance of State-of-the-Art Tools

The evolution of assessment frameworks has provided clear, quantitative evidence of the performance leap driven by new AI methods. The following table synthesizes recent benchmarking results for several leading protein structure prediction tools, highlighting their performance across different types of structural challenges.

Table 3: Benchmarking Performance of Modern Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool / Method | Benchmark Set | Reported Performance | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | CASP14 Targets | GDT_TS >90 for ~2/3 of targets; >80 for ~90% of targets [10]. | Revolutionized monomer prediction; accuracy competitive with experiment. |

| DeepSCFold | CASP15 Multimer Targets | Improvement of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [17]. | Focuses on protein complexes; uses sequence-derived structural complementarity. |

| AlphaFold3 | CASP15 Multimer Targets | Baseline for DeepSCFold comparison [17]. | Integrated model for proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, etc. |

| SPIRED | CAMEO (680 proteins) | Average TM-score = 0.786 (without recycling) [21]. | Lightweight, single-sequence-based model for fast inference. |

| OmegaFold | CAMEO (680 proteins) | Average TM-score = 0.778 (without recycling) [21]. | Single-sequence-based model. |

| ESMFold | CAMEO (680 proteins) | Outperformed SPIRED and OmegaFold [21]. | Single-sequence-based model with very large number of parameters. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The CASP Assessment Workflow

The CASP experiment follows a rigorous, multi-stage protocol to ensure a fair and comprehensive evaluation.

- Target Identification and Release: Experimentalists provide protein sequences for structures that will be made public after the prediction season. CASP organizers release these sequences to predictors over a period of several months [2].

- Model Submission: Predictors submit their 3D atomic coordinates for each target within a strict deadline. Each group can submit multiple models per target [2].

- Blind Assessment: As experimental structures become available, independent assessors (experts in each prediction category) evaluate the submissions using a range of metrics without knowing the identity of the predictor [2].

- Numerical Evaluation and Ranking: The Prediction Center processes the models to generate numerical evaluation results, which are used to rank the methods [10].

- Publication and Community Discussion: Results are published in a special issue of the journal Proteins, and findings are discussed at a public conference [2].

Protocol for Evaluating Complex (Multimer) Prediction

The protocol for assessing protein complex structures, a key focus in recent CASPs, involves specific steps:

- Target Selection: Include experimentally determined structures of protein-protein complexes, ensuring a variety of interface sizes and complexities [10] [17].

- Model Generation: Predictors use only the amino acid sequences of the constituent chains to generate a model of the assembled complex.

- Interface-Focused Evaluation: Assessors compare the predicted complex to the experimental reference using metrics that specifically evaluate the interface quality:

- Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1): Calculated by first identifying residue pairs from different chains that are in contact in both the model and the native structure (True Positives), those in contact only in the model (False Positives), and those in contact only in the native structure (False Negatives). Precision (TP/(TP+FP)), Recall (TP/(TP+FN)), and the F1-score (the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall) are then computed [10].

- LDDTo: A version of the lDDT score used specifically for evaluating the overall accuracy of oligomeric structures [10].

- Comparative Analysis: Performance is compared against baseline methods like AlphaFold-Multimer and earlier CASP results to quantify progress [10] [17].

Workflow Visualization: CASP and CAMEO Assessment Cycles

The following diagram illustrates the integrated and cyclical relationship between the CASP and CAMEO assessment frameworks, which together provide both intensive biennial checkpoints and continuous weekly monitoring of progress in the field.

The following table details key databases, software, and computational resources that are foundational for both developing and benchmarking protein structure prediction methods.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes; serves as the source of ground-truth data for benchmarking [17]. |

| UniProt (UniRef30/90) | Database | Comprehensive resource of protein sequences and functional information; used for constructing Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs), which are critical inputs for many prediction methods [17]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides open access to over 200 million predicted protein structures generated by AlphaFold; enables large-scale analysis and can serve as a source of predicted structural features for downstream tasks [9]. |

| ColabFold DB | Database | Combination of multiple sequence databases (UniRef, BFD, MGnify) optimized for fast, scalable MSA construction with ColabFold and AlphaFold2 [17]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software | An extension of AlphaFold2 specifically designed for predicting structures of protein complexes (multimers); a common baseline and framework for advanced complex prediction [17]. |

| ESMFold | Software | A single-sequence-based protein structure predictor that uses a protein language model; balances high speed with high accuracy, useful for high-throughput predictions [21]. |

| OmegaFold | Software | A deep-learning-based method that predicts structure from a single sequence without the need for MSAs; useful for orphan sequences with few homologs [21]. |

| DeepSCFold | Software | A pipeline for protein complex structure modeling that uses deep learning to predict structural complementarity from sequence, improving interface prediction [17]. |

The evolution of assessment frameworks like CASP and CAMEO has been instrumental in guiding the rapid progress of protein structure prediction. The shift from assessing small, single-domain proteins to evaluating complex multimers and the ability to answer biological questions reflects the field's growing maturity and expanding scope. The rigorous, blind nature of these benchmarks has provided undeniable evidence of the revolutionary impact of deep learning. As the field advances, benchmarks will continue to evolve, likely placing greater emphasis on functional insight, dynamics, and interactions with nucleic acids, ligands, and other molecules in complex cellular environments. For researchers and drug developers, a deep understanding of these assessment frameworks is no longer a niche interest but a critical tool for leveraging the power of modern protein structure prediction.

The field of protein structure prediction has been revolutionized by the advent of deep learning, transitioning from a challenging biological puzzle to a routine computational task. This transformation began in earnest with the breakthrough performance of AlphaFold2 at the CASP14 competition, where it demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental methods for the first time [22] [11]. The core problem—predicting a protein's three-dimensional atomic structure from its amino acid sequence—has implications spanning basic biological research, understanding disease mechanisms, and drug discovery.

Current state-of-the-art tools operate at the interface of biology, chemistry, and computer science, employing sophisticated neural networks trained on known protein structures and evolutionary information. These methods have largely superseded traditional approaches like homology modeling and protein-protein docking, though significant challenges remain in capturing protein dynamics, conformational diversity, and complex molecular interactions [23] [11]. This technical overview examines the architectural principles, methodological approaches, and performance characteristics of major prediction tools, with particular emphasis on their applicability in pharmaceutical research and structural biology.

Methodology: Comparative Framework for Tool Evaluation

Benchmarking Datasets and Metrics

To ensure consistent evaluation across prediction tools, researchers employ standardized datasets and assessment metrics. The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition provides the most rigorous framework, using recently solved experimental structures as blind targets [11]. Additional specialized benchmarks include the SAbDab database for antibody-antigen complexes [17] and curated sets of intrinsically disordered proteins [23].

Primary metrics for assessment include:

- TM-score: Measures global fold similarity (0-1 scale, where >0.5 indicates correct fold)

- pLDDT: Per-residue confidence score (0-100 scale, where >90 indicates high confidence)

- RMSD: Measures atomic distance differences between predicted and experimental structures

- Interface TM-score: Specialized version for evaluating protein-protein interactions

Technical Specifications of Major Prediction Tools

Table 1: Core architectural specifications of major protein structure prediction tools

| Tool | Developer | Core Architecture | Input Requirements | Confidence Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Google DeepMind | Evoformer + Structural Module | MSA + Templates | pLDDT, pTM |

| RoseTTAFold | Baker Lab | 3-track neural network | MSA (optional templates) | pLDDT |

| ESMFold | Meta AI | Transformer-based language model | Single sequence | pLDDT |

| OmegaFold | Oxford Protein Informatics | Transformer-based | Single sequence | pLDDT |

| EMBER3D | University of California | Geometric deep learning | Single sequence | Confidence score |

| SimpleFold | Apple | Flow-matching transformer | Single sequence | Ensemble variance |

Table 2: Performance characteristics and computational requirements

| Tool | Prediction Type | MSA Dependency | Disordered Region Handling | Typical Runtime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Monomer, Multimer (via AF-Multimer) | High | Moderate (low pLDDT indicates disorder) | Hours (MSA-dependent) |

| RoseTTAFold | Monomer, Complexes | Medium | Moderate | Moderate |

| ESMFold | Monomer | None | Limited | Minutes |

| OmegaFold | Monomer | None | Limited | Minutes |

| EMBER3D | Monomer | None | Limited | Fast |

| SimpleFold | Monomer (full-atom) | None | Good (via ensembles) | Variable |

Established Protein Structure Prediction Tools

AlphaFold2

Architectural Principles: AlphaFold2 employs a novel end-to-end deep neural network architecture that jointly embeds evolutionary information and structural constraints. The system consists of two primary components: the Evoformer, a specialized transformer that processes multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to extract co-evolutionary signals, and the Structural Module, which generates atomic coordinates using invariant point attention [22] [11]. This architecture enables the model to reason simultaneously about sequence relationships and spatial geometry.

Methodological Workflow: The standard AlphaFold2 pipeline begins with querying massive sequence databases (UniRef, MGnify) using tools like JackHMMER or MMseqs2 to construct deep MSAs. The Evoformer processes these alignments to produce pairwise distance and angle distributions, which the Structural Module translates into 3D atomic coordinates through iterative refinement. The system outputs both the predicted structure and per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT) that reliably indicate model quality [22].

Performance and Limitations: AlphaFold2 achieves remarkable accuracy, with a median RMSD of approximately 1.6Å on Cα atoms in CASP14, rivaling experimental methods for well-folded domains [22]. However, it exhibits limitations for intrinsically disordered regions (indicated by low pLDDT scores), conformationally flexible proteins, and cases with limited evolutionary information [23] [22]. Additionally, while AlphaFold-Multimer extends capability to complexes, performance remains lower than for monomers, particularly for antibody-antigen interactions where co-evolutionary signals are weak [17].

RoseTTAFold

Architectural Principles: RoseTTAFold implements a three-track neural network that simultaneously processes sequence, distance, and coordinate information, allowing information flow between different representation types [22]. This multi-track approach enables the model to integrate evolutionary coupling information with geometric constraints, though with a different architectural philosophy than AlphaFold2's Evoformer.

Methodological Workflow: The method can operate with or without deep MSAs, though accuracy improves with evolutionary information. RoseTTAFold employs an iterative refinement process where initial predictions inform subsequent updates across the three information tracks. This approach provides robustness when working with shallower MSAs or orphan sequences with limited homologs [23].

Performance Characteristics: While generally slightly less accurate than AlphaFold2 for targets with rich evolutionary information, RoseTTAFold demonstrates competitive performance with significantly reduced computational requirements. Its modular architecture has facilitated adaptations for specialized applications including protein-protein docking and de novo protein design [22].

ESMFold

Architectural Principles: ESMFold represents a paradigm shift from MSA-dependent methods, instead leveraging a protein language model (ESM-2) trained on millions of sequences through self-supervision [22] [24]. The model learns structural principles implicitly from sequence statistics without explicit evolutionary coupling analysis, using a standard transformer architecture to map sequence embeddings directly to 3D coordinates.

Methodological Workflow: ESMFold operates on single sequences without MSAs, dramatically reducing computational requirements from hours to minutes. The ESM-2 encoder produces contextual residue embeddings that capture structural and functional properties, which a structure module decodes into atomic coordinates using geometric transformations [24].

Performance and Applications: While generally less accurate than AlphaFold2 for proteins with rich evolutionary histories, ESMFold excels for orphan sequences with few homologs and enables rapid screening of metagenomic databases [22] [24]. Comparative studies show ESMFold models are superior to AlphaFold2 for approximately 49% of human proteins when predictions disagree, suggesting complementary strengths [24].

Emerging Contenders and Methodological Innovations

SimpleFold: Generative Approaches to Protein Folding

Architectural Innovation: SimpleFold represents a significant departure from established architectures, eliminating domain-specific components like MSA processing, pairwise representations, and triangular updates in favor of a general-purpose transformer backbone trained with flow-matching generative objectives [25]. This approach treats protein folding as a conditional generation task where the amino acid sequence serves as a prompt, analogous to text-to-image generation in computer vision.

Methodological Workflow: The system employs a linear interpolant between noise samples and all-atom positions, conditioned on the amino acid sequence. A transformer-based network learns to approximate the velocity field that moves noise to data through ordinary differential equation integration [25]. This generative approach naturally captures structural uncertainty and enables ensemble prediction, addressing limitations of deterministic methods.

Performance Advantages: SimpleFold-3B, trained on approximately 9 million distilled structures, achieves competitive performance with state-of-the-art baselines while demonstrating superior efficiency on consumer hardware [25]. The flow-matching framework particularly excels at generating structurally diverse ensembles, making it valuable for modeling conformational flexibility.

FiveFold: Ensemble Prediction Methodology

Consensus Architecture: FiveFold employs a meta-prediction strategy that combines outputs from five complementary algorithms: AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D [23]. This ensemble approach mitigates individual algorithmic limitations through weighted consensus building, leveraging the unique strengths of each component method.

Analytical Framework: The methodology introduces two innovative components: the Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC), which provides standardized structural representation enabling quantitative comparison, and the Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM), which systematically captures and visualizes conformational diversity [23]. This framework facilitates generation of multiple biologically plausible conformations rather than single static structures.

Therapeutic Applications: The ensemble approach demonstrates particular utility for intrinsically disordered proteins and dynamic systems relevant to drug discovery. By capturing conformational heterogeneity, FiveFold enables targeting of transient binding sites and allosteric pockets previously considered "undruggable" [23].

DeepSCFold: Advancements in Complex Prediction

Architectural Specialization for Complexes: DeepSCFold addresses the significant challenge of protein complex prediction by incorporating sequence-derived structural complementarity information. The method predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) and interaction probability (pIA-score) purely from sequence information, enabling more biologically relevant paired MSA construction [17].

Methodological Innovations: Unlike traditional approaches that rely primarily on sequence co-evolution, DeepSCFold leverages structural conservation patterns at interaction interfaces, which are more evolutionarily constrained than sequence motifs. This proves particularly valuable for systems lacking clear co-evolutionary signals, such as antibody-antigen and virus-host interactions [17].

Performance Benchmarks: DeepSCFold demonstrates substantial improvements over existing methods, achieving 11.6% and 10.3% TM-score improvements on CASP15 multimer targets compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [17]. For antibody-antigen complexes, success rates for interface prediction improve by 24.7% and 12.4% over the same benchmarks.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized Prediction Workflow

Input Preparation: For MSA-dependent methods, comprehensive sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, MGnify) must be searched using tools like HHblits, JackHMMER, or MMseqs2. MSA-independent methods require only the canonical amino acid sequence. Specialized applications may require additional inputs like template structures or interaction partners.

Model Configuration: Standard protocols employ default network parameters with 3-5 recycling iterations for refinement. For uncertainty estimation, multiple runs with different random seeds or dropout configurations provide confidence intervals. Ensemble methods typically generate 10-20 structures per target.

Quality Assessment and Validation: pLDDT scores provide reliable per-residue confidence estimates, with values <70 indicating low confidence regions potentially corresponding to disorder or flexibility [22]. TM-score >0.5 indicates correct fold prediction, while RMSD <2.0Å indicates high atomic accuracy. Experimental validation through cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, or NMR provides ultimate confirmation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational resources and databases for protein structure prediction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | >200 million precomputed structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk [9] |

| ColabFold | Software Suite | Rapid MSA generation + AF2/ RoseTTAFold | https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold [11] |

| UniProt | Database | Reference protein sequences and annotations | https://www.uniprot.org [26] |

| PDB | Database | Experimental protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org [11] |

| AlphaSync | Database | Continuously updated predicted structures | https://alphasync.stjude.org [26] |

| FiveFold | Methodology | Conformational ensemble generation | Implementation required [23] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The rapid evolution of protein structure prediction tools has transformed structural biology from a bottleneck to a high-throughput endeavor. Current methods demonstrate remarkable accuracy for static monomeric structures, yet significant challenges remain in capturing conformational dynamics, protein-ligand interactions, and cellular context [11].

The emerging trend toward ensemble methods and generative approaches represents a paradigm shift from single-structure prediction to modeling structural landscapes. Methods like FiveFold and SimpleFold explicitly address conformational heterogeneity, providing more biologically realistic representations for drug discovery [25] [23]. Similarly, specialized tools like DeepSCFold extend capabilities to protein complexes, particularly for challenging cases like antibody-antigen interactions [17].

Future developments will likely focus on integrating temporal dynamics, environmental factors, and multi-scale representations bridging atomic to cellular resolution. The convergence of physical principles with data-driven approaches promises more physiologically relevant predictions, ultimately enhancing our understanding of biological function and accelerating therapeutic development.

For research implementation, tool selection should be guided by specific application requirements: AlphaFold2 for maximum accuracy with well-characterized proteins, ESMFold for orphan sequences or high-throughput screening, ensemble methods for conformational diversity assessment, and specialized complex predictors for interaction studies. As the field continues to evolve, these tools will increasingly become integrated components of comprehensive structural biology pipelines rather than standalone applications.

Methodologies in Practice: Single-Chain Predictions, Complex Modeling, and Specialized Approaches

The field of computational biology has been revolutionized by the advent of deep learning approaches to protein structure prediction. At the heart of this revolution lies the Evoformer network architecture and the paradigm of end-to-end structure learning, which together have enabled unprecedented accuracy in predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences. These architectural foundations represent a significant departure from previous computational methods that relied heavily on physical simulations or fragment assembly. Framed within the broader context of benchmarking protein structure prediction tools, the Evoformer's innovative design enables the seamless integration of evolutionary information with structural reasoning, allowing models to directly output accurate atomic coordinates. This technical guide examines the core architectural principles underlying these advances, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of the methodologies driving modern computational structural biology.

The Evoformer Architectural Framework

Core Components and Information Processing

The Evoformer constitutes the fundamental building block of AlphaFold2, serving as the primary engine for processing evolutionary and structural information. This novel neural network module was specifically designed to address the graph inference problem of protein structure prediction in three-dimensional space, where edges represent residues in spatial proximity [4]. Unlike traditional sequential architectures, the Evoformer employs a sophisticated multi-track design that simultaneously reasons about sequence patterns, inter-residue relationships, and three-dimensional structure.

The architecture maintains and processes two primary representations: an MSA representation shaped as an Nseq × Nres array (where Nseq is the number of sequences and Nres is the number of residues) and a pair representation shaped as an Nres × Nres array [4]. The MSA representation encapsulates information about individual residues across homologous sequences, while the pair representation encodes the relationships between residues. The key innovation of the Evoformer lies in its continuous exchange of information between these representations through a series of attention-based and non-attention-based operations that occur within each block of the network.

A crucial aspect of the Evoformer's design is its update operations that enforce geometric consistency constraints essential for producing physically plausible structures. The architecture incorporates triangle multiplicative updates that operate on triples of edges, effectively ensuring that the pairwise relationships satisfy triangle inequality constraints necessary for realizable three-dimensional structures [4]. This explicit enforcement of geometric consistency distinguishes the Evoformer from previous approaches and contributes significantly to its atomic-level accuracy.

Attention Mechanisms and Evolutionary Reasoning

The Evoformer employs specialized attention mechanisms that enable efficient reasoning about long-range dependencies in protein sequences and structures. Specifically, it utilizes axial attention operations within the MSA representation, where attention is applied along sequence and residue dimensions separately [27]. During the per-sequence attention in the MSA, the model projects additional logits from the pair representation to bias the MSA attention, creating a closed loop of information flow between different representations [4].

The attention mechanism follows the scaled dot-product formula:

Attention(Q,K,V) = softmax(QKᵀ/√dₖ)V

where Q, K, and V are query, key, and value matrices derived from residue features, and dₖ is the dimension of the keys, which prevents vanishing gradients in high-dimensional spaces [27]. This mechanism allows the model to query interactions between residues, effectively modeling how distant parts of the protein influence each other based on co-evolutionary signals present in the multiple sequence alignment.

The Evoformer's ability to jointly embed MSAs and pairwise features enables it to infer complex evolutionary and spatial relationships. By processing these information sources simultaneously, the network can identify co-evolution patterns where correlated mutations between residues suggest spatial proximity in the folded structure, providing rich implicit structural information without relying exclusively on templates [4]. This integrated reasoning capability represents a significant advancement over previous systems that processed evolutionary and structural information separately.

End-to-End Structure Learning Paradigm

From Distances to Direct Coordinate Prediction

Modern protein structure prediction has transitioned from predicting intermediate representations to direct atomic coordinate generation. Early deep learning approaches, including AlphaFold1, focused on predicting inter-residue distances and angles, which then required post-processing to generate 3D coordinates [27]. In contrast, AlphaFold2 introduced a fully differentiable architecture that directly outputs 3D atomic coordinates through an end-to-end learning approach [27] [4].

This end-to-end paradigm is implemented through two main network stages. The first stage consists of the Evoformer trunk, which processes input sequence alignments and templates. The second stage comprises the structure module, which introduces explicit 3D structure in the form of a rotation and translation for each residue of the protein [4]. These representations are initialized in a trivial state but rapidly develop into a highly accurate protein structure with precise atomic details through iterative refinement.

Key innovations enabling this end-to-end approach include:

- Equivariant Transformers: The structure module uses novel equivariant attention architectures that respect the symmetry of 3D space, allowing the network to implicitly reason about unrepresented side-chain atoms [4].

- Invariant Point Attention (IPA): A specialized attention mechanism that predicts rigid-body transformations for each residue while preserving rotational invariance [27].

- Iterative Refinement: The network employs a recycling mechanism where outputs are recursively fed back into the same modules, enabling continuous improvement of structural accuracy [4].

Integrated Sequence-Structure Learning

Recent advances have extended the end-to-end learning paradigm to encompass both structure prediction and sequence design. The E2EFold model demonstrates this integration by learning both tasks end-to-end in a discrete, stochastic autoencoder framework [28]. This approach enables significantly improved sequence design self-consistency, where the model reconstructs input backbones and predicts sidechain conformations while being guided by an auxiliary sequence recovery objective.

The RoseTTAFold-based ProteinGenerator (PG) further exemplifies this trend by implementing diffusion in sequence space rather than structure space [29]. Beginning from a noised sequence representation, PG simultaneously generates protein sequences and structures by iterative denoising, guided by desired sequence and structural attributes. This approach enables reasoning over both sequence and structure space, allowing the design of proteins with specific functional properties and amino acid compositions beyond the natural distribution [29].

Table 1: Comparison of End-to-End Learning Approaches in Protein Structure Prediction

| Method | Primary Innovation | Training Approach | Key Outputs | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Evoformer with structure module | Supervised learning on PDB structures | 3D atomic coordinates | Protein structure prediction [4] |

| E2EFold | Discrete stochastic autoencoder | End-to-end reconstruction | Sequences and structures | Joint structure prediction and sequence design [28] |

| ProteinGenerator | Sequence space diffusion | Denoising diffusion probabilistic model | Sequence-structure pairs | Functional protein design [29] |

| BoltzGen | Unified protein design and structure prediction | Multi-task learning | Novel protein binders | Drug discovery for undruggable targets [30] |

Benchmarking and Performance Metrics

Accuracy Metrics and Validation

Rigorous benchmarking of protein structure prediction tools requires multiple complementary metrics that capture different aspects of structural accuracy. The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competitions have established standardized evaluation protocols that have become the gold standard in the field [27]. Key metrics include:

- Global Distance Test (GDTTS): Measures the percentage of residues aligned within distance cutoffs of 1, 2, 4, and 8 Å, scaled from 0 to 100. AlphaFold2 achieved a median GDTTS of 92.4 in CASP14, dramatically outperforming other methods [27].

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Quantifies the average atomic distance between superimposed predicted and native structures after optimal alignment. AlphaFold2 demonstrated a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD95 compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method in CASP14 [4].

- Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT): A per-residue confidence metric that reliably estimates the local accuracy of predictions. pLDDT values greater than 90 indicate high confidence, while values below 50 suggest low reliability [4] [31].

These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of prediction quality, with GDT_TS offering a global measure of fold correctness, RMSD quantifying atomic-level precision, and pLDDT providing residue-level confidence estimates.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Extensive benchmarking has demonstrated the revolutionary performance of Evoformer-based approaches. In the challenging CASP14 assessment, AlphaFold2 structures were vastly more accurate than competing methods, with accuracy competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases [4]. This performance advantage extends beyond the CASP benchmark to real-world applications, as evidenced by the rapid adoption of these tools in biological research.

The impact of these advances is quantifiable through large-scale studies of scientific output. Researchers using AlphaFold submitted approximately 50% more protein structures to the Protein Data Bank than a non-AlphaFold-using baseline of structural biology researchers [32]. Furthermore, the AlphaFold database has been accessed by approximately 3.3 million users in over 190 countries, with more than one million users coming from low- and middle-income countries, dramatically expanding global access to structural information [32].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Method | CASP14 GDT_TS (Median) | Backbone RMSD95 (Å) | All-Atom RMSD95 (Å) | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 92.4 [27] | 0.96 [4] | 1.5 [4] | High (GPU/TPU clusters) |

| Previous Best Method | ~50 (estimated) | 2.8 [4] | 3.5 [4] | Moderate to High |

| RoseTTAFold | Not reported in CASP14 | Not reported | Not reported | Moderate (gaming computer) [33] |

| Liteformer | Competitive with AlphaFold2 [34] | Similar to AlphaFold2 [34] | Not reported | 44% reduced memory vs Evoformer [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Network Training and Optimization

The training of Evoformer-based networks involves sophisticated methodologies that combine supervised learning with novel regularization techniques. AlphaFold2 was trained on experimentally determined protein structures from the Protein Data Bank, incorporating several key innovations [4]:

- Intermediate Losses: Application of loss functions at multiple stages of the network to achieve iterative refinement of predictions.

- Masked MSA Loss: Joint training with the structure prediction objective by randomly masking portions of the input MSA and training the network to reconstruct the original sequences.

- Self-Distillation: Learning from unlabeled protein sequences using the network's own predictions to expand the training dataset.

- Recycling: Repeatedly applying the final loss to outputs and feeding them recursively into the same modules, enabling progressive refinement.

The training process incorporates a frame-aligned point error (FAPE) loss that operates directly on the 3D atomic positions and orientations, placing substantial weight on the orientational correctness of residues [27]. This geometric loss function is crucial for achieving high all-atom accuracy, particularly for side-chain placement.

Architectural Variants and Efficiency Optimizations

While the original Evoformer architecture delivers exceptional accuracy, its computational demands have motivated research into more efficient variants. Liteformer addresses the Evoformer's high memory consumption, particularly concerning the computational complexity associated with sequence length (L) and the number of Multiple Sequence Alignments (s) [34]. The original Evoformer exhibits complexity of O(L³+sL²) due to attention mechanisms involving third-order MSA and pair-wise tensors.

Liteformer employs an innovative attention linearization mechanism, reducing complexity to O(L²+sL) through a bias-aware flow attention mechanism that seamlessly integrates MSA sequences and pair-wise information [34]. This optimization achieves up to a 44% reduction in memory usage and a 23% acceleration in training speed while maintaining competitive accuracy in protein structure prediction, making the technology more accessible for researchers with limited computational resources.

Diagram 1: Evoformer Architecture and Information Flow. This diagram illustrates the key components and information pathways in the Evoformer-based structure prediction network, showing how multiple sequence alignments, templates, and sequence information are integrated to produce 3D atomic structures with confidence estimates.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental implementation of Evoformer-based models requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential components for researchers seeking to utilize or build upon these architectural foundations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evoformer-Based Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 Code | Software | Reference implementation of Evoformer architecture | Open source (July 2021) [27] |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | Alternative three-track neural network for protein structure prediction | Open source via GitHub [33] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Experimental protein structures for training and validation | Public repository [35] [27] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Precomputed predictions for over 240 million protein structures | EMBL-EBI hosted [32] [27] |

| UniProt | Database | Protein sequences for multiple sequence alignment generation | Public repository [27] |

| Liteformer | Software | Optimized Evoformer variant with reduced memory footprint | Research implementation [34] |

| E2EFold | Software | End-to-end model for joint structure prediction and sequence design | Research implementation [28] |

| ProteinGenerator | Software | Sequence space diffusion model based on RoseTTAFold | Research implementation [29] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Complex Biomolecular Systems

The architectural principles established in Evoformer networks are being extended to model increasingly complex biological systems. AlphaFold3 demonstrates the capability to model joint structures and interactions of biomolecular complexes, including proteins with DNA, RNA, ligands, and ions, using a diffusion-based architecture for enhanced accuracy [27]. Similarly, tools like Umol predict the fully flexible all-atom structure of protein-ligand complexes directly from sequence information, achieving a success rate of 45% when pocket information is provided [31].

These advances enable new applications in drug discovery, where accurate prediction of protein-ligand interactions is crucial. Umol's confidence metrics (pLDDT) can distinguish between strong and weak binders, with ligand pLDDT values above 70 correlating with median affinities of 30 nM, compared to 500 nM for values below 60 [31]. This capability to predict interaction strength directly from sequence information represents a significant advancement toward AI-based drug discovery.

Integrated Design and Prediction Frameworks

The future of protein structure prediction lies in increasingly integrated frameworks that combine structure prediction with design capabilities. BoltzGen exemplifies this trend as the first model to unify protein design and structure prediction while maintaining state-of-the-art performance [30]. This model can carry out a variety of tasks and includes built-in constraints informed by wet-lab collaborators to ensure the creation of functional proteins that respect physical and chemical laws.

The ProteinGenerator framework demonstrates how sequence space diffusion enables the design of proteins with specific properties, such as controlled amino acid composition, isoelectric points, and hydrophobicity [29]. By guiding the diffusion process with sequence-based potentials, researchers can design proteins with evolutionarily undersampled amino acids that confer structural or functional properties, expanding the design space beyond natural proteins.

Diagram 2: Integrated Protein Design and Structure Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of protein design and validation using Evoformer-based architectures, showing how sequence, structural, and functional constraints inform the generation of novel proteins that undergo experimental validation.