Benchmarking RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows: A qPCR Validation Framework for Reliable Gene Expression Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-Seq analysis workflows using qPCR.

Benchmarking RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows: A qPCR Validation Framework for Reliable Gene Expression Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-Seq analysis workflows using qPCR. It explores the foundational need for benchmarking in transcriptomics, methodically compares the performance of popular alignment and quantification tools, and outlines optimization strategies to address common pitfalls. By synthesizing evidence from large-scale multi-center studies and presenting a framework for comparative analysis, the content equips scientists with the knowledge to achieve accurate and reproducible gene expression data, a critical foundation for robust biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Need for Benchmarking RNA-Seq Against qPCR Gold Standards

RNA-Seq as the Modern Transcriptome Standard and its Inherent Complexities

RNA sequencing has unequivocally established itself as the modern standard for transcriptome analysis, revolutionizing our capacity to explore gene expression landscapes in health and disease. This technology provides unprecedented detail about the RNA repertoire within biological samples, enabling comprehensive characterization of transcriptional activity across different conditions, time points, and cellular populations. However, beneath its transformative potential lies a complex framework of methodological choices, analytical pipelines, and technical variations that significantly impact data reliability and biological interpretation.

The complexities inherent to RNA-seq are particularly relevant when contextualized within benchmarking frameworks against quantitative PCR (qPCR), long considered the gold standard for targeted gene expression validation. While RNA-seq offers an unbiased, genome-wide perspective, its performance must be rigorously assessed against established metrics to ensure analytical validity, especially as it transitions from research tool to clinical application. This guide objectively compares RNA-seq methodologies and their performance characteristics, drawing upon recent large-scale benchmarking studies to provide evidence-based recommendations for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating this powerful yet complex technological landscape.

RNA-Seq Technology Landscape: Methodological Comparisons

The RNA-seq ecosystem has diversified into multiple specialized approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal applications. Understanding these methodological divisions is essential for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation.

Short-Read vs. Long-Read RNA Sequencing

Short-read RNA-seq (primarily Illumina-based) remains the workhorse for transcriptome profiling, providing high accuracy and depth for gene-level expression quantification. However, long-read RNA-seq technologies (Nanopore and PacBio) are emerging as powerful complementary approaches that enable full-length transcript sequencing, overcoming short-read limitations in isoform resolution [1].

A comprehensive benchmark of Nanopore long-read RNA sequencing demonstrated its robust performance in identifying major isoforms, detecting novel transcripts, characterizing fusion events, and profiling RNA modifications [2]. The Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project systematically compared five RNA-seq protocols across seven human cell lines, reporting that long-read protocols more reliably capture complete transcript structures, with PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing requiring the least input RNA and direct RNA sequencing providing information about native RNA modifications [2].

Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Bulk RNA-seq profiles the averaged transcriptome across cell populations, while single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) resolves cellular heterogeneity by capturing transcriptomes of individual cells. Within scRNA-seq, two primary approaches exist:

- Whole Transcriptome Sequencing: An unbiased, discovery-oriented method that aims to capture expression of all genes, ideal for de novo cell type identification and atlas construction [3].

- Targeted Gene Expression Profiling: Focuses sequencing resources on a predefined gene set, achieving superior sensitivity and quantitative accuracy for specific pathways or signatures, though it is blind to genes outside the panel [3].

Targeted vs. Whole Transcriptome Approaches

Targeted RNA-seq enriches for specific genes or transcripts of interest, enabling deeper coverage and enhanced detection of low-abundance targets. A recent evaluation of targeted RNA-seq for detecting expressed mutations in precision oncology demonstrated its ability to uniquely identify clinically actionable variants missed by DNA sequencing alone, with carefully controlled false positive rates ensuring high accuracy [4]. This approach is particularly valuable in clinical contexts where specific biomarker detection is paramount.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major RNA-Seq Technologies

| Technology | Optimal Applications | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations | qPCR Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read RNA-Seq | Gene-level differential expression, splicing analysis, large cohort studies | High accuracy, cost-effective, well-established tools, high throughput | Limited isoform resolution, inference required for transcript assembly | High for moderate to highly expressed genes |

| Long-Read RNA-Seq | Full-length isoform detection, novel transcript discovery, fusion characterization, RNA modifications | End-to-end transcript sequencing, eliminates assembly challenges, direct RNA modification detection | Higher error rates, lower throughput, higher input requirements, developing analytical tools | Requires validation for isoform-specific quantification |

| Single-Cell Whole Transcriptome | Cell atlas construction, novel cell type discovery, developmental trajectories, heterogeneous tissue mapping | Unbiased cellular census, detects novel cell states and populations | High cost per cell, gene dropout effect (false negatives), computational complexity, data sparsity | Lower concordance for low-abundance transcripts due to dropout |

| Single-Cell Targeted | Validation studies, pathway-focused interrogation, clinical biomarker assessment, large-scale screens | Superior sensitivity for panel genes, reduced dropout, cost-effective at scale, streamlined analysis | Limited to predefined genes, discovery potential constrained | High concordance for targeted genes due to increased read depth |

| Targeted RNA-Seq (Bulk) | Expressed mutation detection, clinical diagnostics, low-abundance transcript quantification, fusion detection | Enhanced detection of rare variants, high coverage of targets, cost-effective for focused questions | Restricted to panel content, design challenges for novel targets | Excellent concordance when targets are expressed |

The translation of RNA-seq into clinical diagnostics requires ensuring reliability and cross-laboratory consistency, particularly for detecting subtle differential expression between disease subtypes or stages. A landmark multi-center RNA-seq benchmarking study, part of the Quartet project, systematically evaluated performance across 45 laboratories using reference samples with defined 'ground truth' [5].

Major Findings from Large-Scale Benchmarking

The study revealed significant inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expression, with experimental factors including mRNA enrichment methods and library strandedness emerging as primary sources of variation [5]. Bioinformatics pipelines also substantially influenced results, with each analytical step contributing to variability in gene expression measurements. The performance gap was particularly pronounced when analyzing samples with small biological differences (Quartet samples) compared to those with large differences (MAQC samples), highlighting the heightened challenge of detecting clinically relevant subtle expression changes [5].

The benchmark underscored the profound influence of experimental execution and provided best practice recommendations for experimental designs, strategies for filtering low-expression genes, and optimal gene annotation and analysis pipelines [5]. These findings emphasize that rigorous standardization is indispensable for reliable RNA-seq implementation, especially in clinical contexts.

Experimental Factors Influencing RNA-Seq Performance

Table 2: Key Experimental Factors Contributing to RNA-Seq Variability

| Experimental Process | Impact on Data Quality | Recommendations from Benchmarking Studies |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction & Quality | Integrity, purity, and fragmentation affecting library complexity and bias | Implement rigorous QC (RIN > 8), standardize extraction protocols across samples |

| mRNA Enrichment | Efficiency influences 3' bias, transcript coverage, and detection dynamic range | Evaluate poly-A selection vs. rRNA depletion based on application; maintain consistency |

| Library Preparation | Strandedness, adapter design, and amplification introduce significant technical variation | Use stranded protocols; minimize PCR cycles; employ unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) |

| Sequencing Depth | Directly affects gene detection sensitivity and quantitative accuracy | 20-30M reads per sample for standard differential expression; increase for isoform detection |

| Spike-in Controls | Enable technical variation monitoring and cross-sample normalization | Use ERCC or sequin spike-ins for quality control and normalization reference [6] [2] |

Best Practices for RNA-Seq Workflow Optimization

Analytical Pipeline Considerations

A comprehensive workflow optimization study systematically evaluated 288 analysis pipelines using different tool combinations across multiple fungal, plant, and animal datasets [7]. The results demonstrated that different analytical tools show significant performance variations when applied to different species, challenging the common practice of applying similar parameters across diverse organisms without customization [7].

For differential expression analysis, benchmarking evidence indicates that performance depends critically on biological effect size and replicate number. When biological effect size is strong, methods like NOISeq or GFOLD effectively detect differentially expressed genes even in unreplicated experiments. However, with mild effect sizes (more representative of clinical scenarios), triplicate replicates are essential, and methods with high positive predictive value (PPV) such as NOISeq or GFOLD are recommended [8]. At larger replicate sizes (n=6), DESeq2 and edgeR show superior PPV and sensitivity trade-offs for systems-level analysis [8].

Computational Considerations for Large-Scale Data

As dataset sizes grow, computational efficiency becomes increasingly important. Benchmarking of large-scale single-cell RNA-seq analysis frameworks revealed that scalability depends critically on both algorithmic and infrastructural factors [9]. GPU-based computation using rapids-singlecell provided a 15× speed-up over the best CPU methods, with moderate memory usage [9]. For principal component analysis—a critical step in many workflows—ARPACK and IRLBA algorithms were most efficient for sparse matrices, while randomized SVD performed best for HDF5-backed data [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA transcripts at known concentrations for quality control and normalization | Evaluates technical performance, enables cross-platform normalization [5] |

| Sequins Spike-ins | Synthetic, spliced RNA spike-in controls with sequence similarity to human transcriptome | Benchmarking isoform detection and quantification accuracy in complex backgrounds [6] |

| Quartet Reference Materials | RNA from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines with well-characterized, subtle expression differences | Assesses performance in detecting clinically relevant subtle differential expression [5] |

| MAQC Reference Samples | RNA from cancer cell lines (MAQC A) and brain tissues (MAQC B) with large expression differences | Benchmarking for experiments with large anticipated effect sizes [5] |

| GIAB Reference Samples | Well-characterized reference genomes and transcriptomes (e.g., GM24385) | Analytical validation and proficiency testing for clinical RNA-seq [10] |

| Stranded mRNA Prep Kits | Library preparation with strand orientation preservation | Accurate transcript assignment, anti-sense transcription detection |

| Ribo-depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA and non-coding RNA | Enhances sequencing efficiency for non-polyA transcripts or degraded samples |

| Single-Cell Isolation Kits | Partitioning individual cells for scRNA-seq library preparation | Enables cellular heterogeneity resolution, available for whole transcriptome or targeted |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Protocol 1: Clinical RNA-Seq Validation for Mendelian Disorders

A comprehensive clinical validation study established a diagnostic RNA-seq framework using 130 samples (90 negative, 40 positive) with known molecular diagnoses [10]. The protocol employs:

- Sample Processing: Fibroblasts cultured in high-glucose DMEM with supplements; blood samples stored in PAXgene tubes at -80°C before RNA extraction [10].

- RNA Extraction: Using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) with on-column genomic DNA removal, followed by quality assessment with Qubit RNA HS assay kit [10].

- Library Preparation: Illumina Stranded mRNA prep kit for fibroblasts and lymphoblastoid cells; Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus for whole blood to remove human globin RNA and rRNA [10].

- Sequencing: Illumina NovaSeqX platform, paired-end 150 bp reads, target depth of 150 million reads per sample [10].

- Data Processing: Alignment to GRCh38 with STAR, duplicate marking with Picard, quantification with RNA-SeQC and RSEM, annotation with GENCODE v39 [10].

- Validation Framework: Uses a 3-1-1 reproducibility design (triplicate preparations intra-run, two inter-runs) on reference materials (GM24385, K562) [10].

Protocol 2: In Silico Mixtures for Long-Read Tool Benchmarking

To address the challenge of benchmarking without established ground truth, researchers developed an innovative approach using in silico mixtures:

- Cell Lines and Controls: Two human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (H1975 and HCC827) profiled in triplicate with synthetic, spliced spike-in RNAs ("sequins") [6].

- Sequencing: Deep sequencing on both Illumina short-read and Oxford Nanopore Technologies long-read platforms [6].

- In Silico Mixtures: Computational creation of mixture samples from pure RNA samples to enable performance assessment without true positives/negatives [6].

- Benchmarking Workflow: Systematic comparison of 6 isoform detection tools, 5 differential transcript expression tools, and 5 differential transcript usage tools [6].

- Key Findings: StringTie2 and bambu outperformed for isoform detection; DESeq2, edgeR and limma-voom excelled for differential transcript expression; no clear front-runner for differential transcript usage analysis [6].

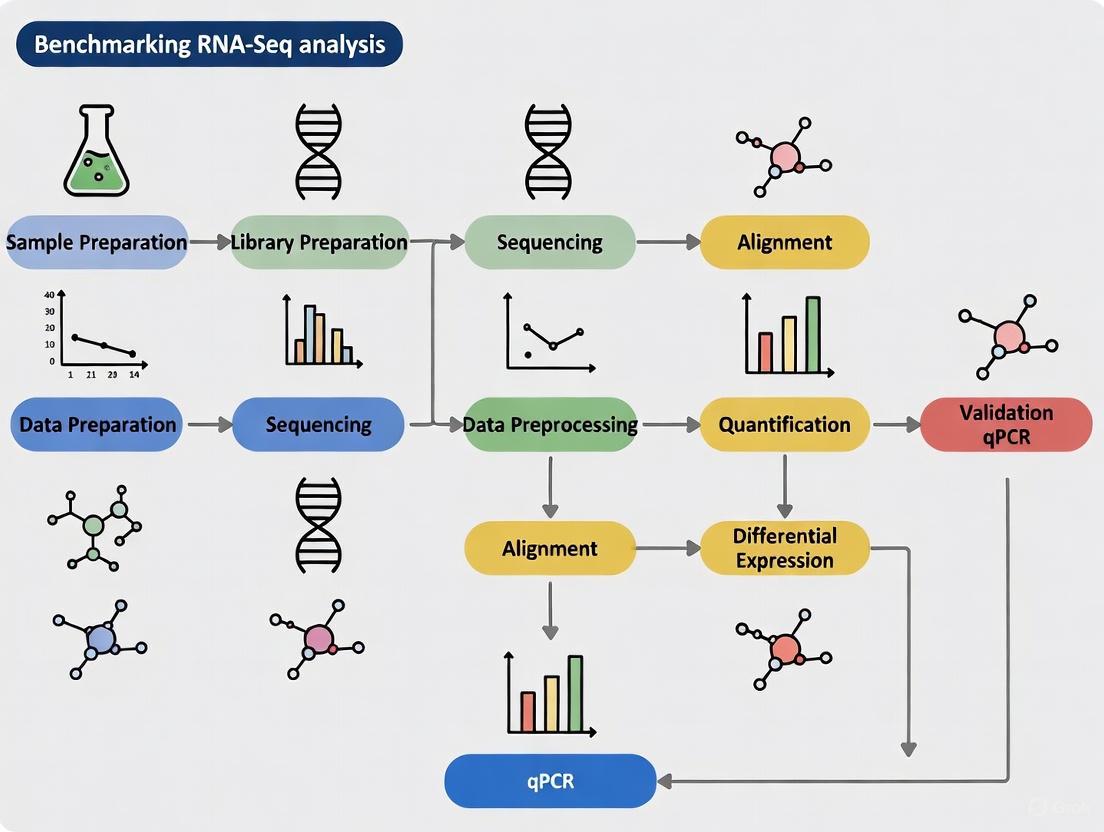

Visualization of RNA-Seq Benchmarking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive framework for benchmarking RNA-seq analysis workflows, integrating experimental and computational components:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive RNA-Seq Benchmarking Framework. This workflow integrates reference materials with known ground truth, standardized experimental protocols, diverse sequencing platforms, and multiple bioinformatics pipelines to generate performance metrics that inform best practices.

RNA-seq maintains its position as the modern standard for transcriptome analysis, but its inherent complexities demand rigorous benchmarking and standardization, particularly when contextualized against qPCR validation. The evidence from large-scale multi-center studies indicates that both experimental and computational factors introduce substantial variability, especially when detecting subtle differential expression with clinical relevance.

The trajectory of RNA-seq development points toward increased specialization—with long-read technologies solving isoform resolution challenges, targeted approaches enhancing clinical applicability, and single-cell methods resolving cellular heterogeneity. Successful navigation of this landscape requires careful matching of technology to biological question, adherence to benchmarking best practices, and implementation of standardized workflows validated against appropriate reference materials. As the field advances, the integration of DNA and RNA sequencing approaches promises to further strengthen molecular diagnostics, ultimately enhancing precision medicine and improving patient outcomes through more reliable and comprehensive genetic analysis.

The Role of qPCR as a Validation Benchmark in Transcriptomics

In the field of transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification [11]. However, this technology relies on complex computational workflows for data processing, creating a critical need for robust validation using an independent, highly accurate method. Among available technologies, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has emerged as the established benchmark for validating RNA-seq findings due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [12] [13]. This review examines the experimental evidence establishing qPCR's role as a validation tool, provides direct performance comparisons between major RNA-seq workflows, and offers best practices for employing qPCR in verification studies.

qPCR Fundamentals and Methodological Advantages

Technical Principles of qPCR

qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, enables accurate quantification of nucleic acid sequences by monitoring PCR amplification in real-time using fluorescent detection systems [12]. When used for gene expression analysis (RT-qPCR), RNA is first reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified and quantified. Unlike traditional PCR that provides end-point detection, qPCR focuses on the exponential amplification phase where the quantity of target DNA doubles with each cycle, providing the most precise and accurate data for quantification [12]. The critical measurement in qPCR is the threshold cycle (CT), which represents the PCR cycle at which the sample's fluorescent signal exceeds background levels, correlating inversely with the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid [12].

Advantages Over Other Technologies

qPCR offers several distinct advantages that make it ideal for validation studies:

- Exceptional sensitivity: Capable of detecting down to a single copy of a DNA sequence [12]

- Wide dynamic range: Can quantify targets across a concentration range of 6-8 orders of magnitude [12]

- High precision: Can detect small fold-changes in gene expression that other technologies might miss [12]

- Minimal sample requirement: Can generate reliable data from limited starting material [14]

These technical advantages position qPCR as the preferred method for confirming gene expression patterns identified through high-throughput screening technologies like RNA-seq.

Experimental Benchmarking: qPCR Versus RNA-Seq Workflows

Large-Scale Comparative Studies

A comprehensive benchmarking study compared five popular RNA-seq processing workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for 18,080 protein-coding genes using the well-established MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples [11] [15]. The research evaluated both alignment-based workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq) and pseudoalignment methods (Kallisto, Salmon), with gene expression measurements compared to wet-lab validated qPCR assays.

The results demonstrated high correlation between all RNA-seq methods and qPCR data, with Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from R² = 0.798 (Tophat-Cufflinks) to R² = 0.845 (Salmon) [11]. When comparing gene expression fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples, approximately 85% of genes showed consistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR data across all workflows [11] [15].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Workflows Against qPCR Benchmark

| RNA-Seq Workflow | Expression Correlation (R²) | Fold Change Correlation (R²) | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 18.2% |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 17.8% |

Another independent study using the MAQC dataset found that RNA-seq relative expression estimates correlated with RT-qPCR measurements in the range of 0.85 to 0.89, with HTSeq exhibiting the highest correlation [16].

Method-Specific Discrepancies and Consistent Patterns

Each RNA-seq method revealed a small but specific set of genes with inconsistent expression measurements compared to qPCR data [11] [15]. A significant proportion of these method-specific inconsistent genes were reproducibly identified in independent datasets, suggesting systematic rather than random errors. These problematic genes were typically characterized by shorter length, fewer exons, and lower expression levels compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [11].

Experimental Design and Methodological Protocols

Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

Proper sample handling is critical for generating reliable qPCR data. In benchmarking studies, RNA is typically extracted using commercially available kits such as the mirVana RNA Isolation Kit or TIANGEN RNAprep Plant Kit [14] [17]. For tissue samples, preservation in RNAlater followed by storage at -80°C helps maintain RNA integrity [14]. RNA quality assessment should be performed using methods such as BioAnalyzer 2100 to ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 6 or distinct ribosomal peaks [14].

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Setup

For reverse transcription, either oligo d(T)₁₆ or random primers can be used, with the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit being a common choice [13]. The qPCR reactions typically use SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry, with reactions run in technical replicates on systems such as the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus or QuantStudio platforms [18] [17].

A standard 20μL reaction might contain:

- 10μL of 2× SYBR Green PreMix

- 0.6μL of each primer (10 nM concentration)

- 2μL of diluted cDNA template

- 6.8μL of RNase-free water [17]

The thermal cycling conditions typically include an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 minute [17].

Essential Experimental Controls

Appropriate controls are vital for validation experiments:

- No-template controls: To detect contamination

- No-reverse transcription controls: To assess genomic DNA contamination

- Reference genes: For normalization (see Section 5.1)

- Melting curve analysis: To verify amplification specificity [13] [17]

Critical Factors for Reliable qPCR Validation

Reference Gene Selection and Normalization

The choice of appropriate reference genes (RGs) is arguably the most critical factor in obtaining accurate qPCR results. Reference genes should demonstrate stable expression across all experimental conditions, but numerous studies have shown that commonly used "housekeeping" genes can vary significantly under different physiological or pathological conditions [19] [13] [17].

Table 2: Stable Reference Genes for Different Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Most Stable Reference Genes | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Canine GI tissues | RPS5, RPL8, HMBS | GeNorm, NormFinder |

| Human glioblastoma | RPL13A, TBP | ΔCt method |

| Lotus plant tissues | TBP, UBQ, EF-1α | GeNorm, NormFinder |

| General recommendation | Global Mean (GM) of ≥55 genes | CV analysis |

A 2025 study on canine gastrointestinal tissues demonstrated that the global mean (GM) method, which uses the average expression of all tested genes, outperformed traditional reference gene normalization when profiling larger gene sets (>55 genes) [19]. For smaller gene panels, using a combination of 2-3 validated reference genes such as RPS5, RPL8, and HMBS provided the most stable normalization [19].

Specialized algorithms such as GeNorm and NormFinder are recommended for assessing reference gene stability [19] [13] [17]. These tools rank candidate reference genes based on their expression stability across samples, enabling evidence-based selection of the most appropriate normalizers for specific experimental conditions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

For relative quantification, the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method is widely used [12]. This approach normalizes target gene CT values to reference genes (ΔCT) and then compares these values between experimental and control groups (ΔΔCT). The final fold-change is calculated as 2^(-ΔΔCT).

When comparing RNA-seq and qPCR data, researchers should focus on relative expression changes (fold changes between conditions) rather than absolute expression values, as this is the most biologically relevant metric and shows better concordance between technologies [11].

Advanced Applications and Recent Innovations

qPCR in Diagnostic Assay Development

Recent advances have demonstrated qPCR's potential in clinical applications. A 2025 study developed a qPCR-based algorithm using platelet-derived RNA for ovarian cancer detection, achieving 94.1% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity [14]. This approach utilized intron-spanning read counts rather than conventional gene expression levels, enhancing detection of cancer-specific splicing events while reducing interference from contaminating genomic DNA.

Comparison of Instrument Platforms

Several qPCR systems are available with varying capabilities:

Table 3: Comparison of qPCR Instrument Platforms

| Instrument | Best For | Key Features | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 | Routine qPCR | User-friendly interface, cloud connectivity | 96-384 wells |

| Bio-Rad CFX Opus96 | High-performance qPCR | Advanced data analysis, BR.io cloud integration | 96 wells |

| Bio-Rad QX200 AutoDG | Digital PCR applications | Absolute quantification, rare mutation detection | Automated droplet generation |

| Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus | Budget-conscious labs | Compact footprint, proven reliability | 96 wells |

The selection of an appropriate platform depends on application requirements, throughput needs, and budget constraints [18].

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for benchmarking RNA-seq data using qPCR validation:

Diagram 1: RNA-seq Validation Workflow with qPCR Benchmarking

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for qPCR Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | High-quality RNA extraction | mirVana RNA Isolation Kit, TIANGEN RNAprep Plant Kit |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | cDNA synthesis from RNA | High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, FastQuant RT Kit |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification and detection | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan PreMix |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalization controls | Pre-validated primer/probe sets |

| qPCR Instruments | Amplification and detection | Applied Biosystems QuantStudio, Bio-Rad CFX Opus96 |

| RNA Quality Assessment | RNA integrity verification | BioAnalyzer 2100, TapeStation 4200 |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that qPCR serves as an essential validation benchmark for RNA-seq workflows, with correlation coefficients typically ranging from 0.80 to 0.93 depending on the specific workflow and analysis method [11] [16]. Based on current research, the following best practices are recommended:

- Validate reference genes for each specific experimental condition using algorithms like GeNorm or NormFinder [19] [13] [17]

- Focus on fold-change comparisons rather than absolute expression values when correlating RNA-seq and qPCR data [11]

- Exercise particular caution with genes that are shorter, have fewer exons, or show low expression levels, as these are more prone to quantification discrepancies [11] [15]

- Consider the global mean method for normalization when profiling larger gene sets (>55 genes) [19]

- Utilize appropriate instrumentation matched to throughput needs and application requirements [18]

When properly implemented, qPCR validation provides an essential quality control measure that strengthens the reliability of transcriptomic studies and enables more confident biological conclusions.

The translation of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) from a research tool to a clinically viable technology hinges on the rigorous benchmarking of its performance against established quantitative methods. While RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for targeted gene expression quantification due to its sensitivity, dynamic range, and established reproducibility [11]. Consequently, a comprehensive comparison of these technologies requires well-defined metrics that assess both the consistency of absolute expression measurements and the accuracy of detecting expression changes between conditions. This guide objectively compares RNA-seq and qPCR performance using two cornerstone metrics—expression correlation and differential expression (DE) performance—providing researchers with a framework for evaluating RNA-seq workflow suitability for specific applications. The analysis is contextualized within a broader thesis on benchmarking RNA-seq workflows, leveraging experimental data from controlled studies to inform best practices for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Comparison Metrics

Expression Correlation

Expression correlation measures the concordance between absolute or relative expression levels obtained from RNA-seq and qPCR across a set of genes and samples. It is typically quantified using Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) or Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (rho), which assess linear and monotonic relationships, respectively.

High correlation indicates that RNA-seq can reliably reproduce the expression hierarchies established by qPCR. However, correlation can be influenced by factors including the expression level of genes (with low-abundance transcripts often showing poorer correlation), the specific RNA-seq quantification method used, and the normalization strategies applied to both datasets [11] [20].

Differential Expression (DE) Performance

Differential expression performance evaluates how well RNA-seq identifies genes with statistically significant expression changes between conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) compared to qPCR. This metric moves beyond absolute expression to assess the accuracy of detecting relative changes, which is the primary goal of many transcriptomic studies.

Key measures for DE performance include:

- Fold-Change Correlation: The correlation (often Pearson's R) of log2 fold-changes between RNA-seq and qPCR.

- Concordance/Non-Concordance Rates: The percentage of genes classified as differentially expressed by both methods (concordant) or by only one method (non-concordant) [11].

- Sensitivity and Specificity: The ability of RNA-seq to recover DEGs identified by qPCR (sensitivity) and to exclude non-DEGs (specificity), though this requires a defined "truth set" from qPCR.

Quantitative Performance Data

Benchmarking studies consistently reveal high overall concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR, though performance varies by the specific analytical workflow employed.

Table 1: Overall Performance of RNA-seq Workflows Against qPCR Benchmark

| RNA-seq Workflow | Expression Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Fold-Change Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | Pseudoalignment; fast; transcript-level quantification [11] |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | Pseudoalignment; fast; low computing resource demand [11] [20] |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | Alignment-based; high precision; gene-level quantification [11] |

| TopHat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | Alignment-based; established method [11] |

| TopHat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | Alignment-based; FPKM-based quantification [11] |

A landmark study by the Microarray Quality Control (MAQC) Consortium compared five RNA-seq workflows against a whole-transcriptome qPCR dataset of over 18,000 protein-coding genes. The results demonstrated high expression and fold-change correlations for all tested methods, with pseudoalignment tools (Salmon, Kallisto) and alignment-based count tools (HTSeq-based pipelines) performing comparably well [11]. Another independent study further confirmed that results are highly correlated among procedures using HTSeq for quantification [20].

Performance on Challenging Gene Sets

Despite strong overall performance, certain gene characteristics can lead to discrepancies between RNA-seq and qPCR.

Table 2: Performance on Challenging Gene Sets

| Gene Characteristic | Impact on RNA-seq/qPCR Concordance | Recommended Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Low Expression Level | Higher rates of discordance; genes with inconsistent measurements are often lower expressed [11]. | Apply a minimal expression filter (e.g., 0.1 TPM) to avoid bias from low-abundance genes [11]. |

| Extreme Expression Level | Major differences in expression values often come from genes with very high or very low levels [20]. | Be cautious when interpreting results for extreme outliers; consider validation. |

| Complex Gene Families (e.g., HLA) | Moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) due to extreme polymorphism and paralogous sequences [21]. | Use HLA-tailored bioinformatic pipelines that account for known diversity, rather than a standard reference genome [21]. |

| Small Gene Size / Fewer Exons | Genes with inconsistent expression measurements are often smaller and have fewer exons [11]. | Careful validation is warranted for this specific gene set [11]. |

A study focusing on HLA class I genes demonstrated that even with HLA-tailored pipelines, the correlation between qPCR and RNA-seq expression estimates was only low to moderate (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53). This highlights the significant technical challenges posed by highly polymorphic and complex genomic regions and underscores that performance can be gene-specific [21].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure a fair and accurate comparison between RNA-seq and qPCR, the following experimental and analytical protocols are recommended based on established benchmarking studies.

Sample Preparation and Platform Comparison

- Reference Samples: Well-characterized RNA reference samples are crucial. The MAQC project established two widely used samples: Universal Human Reference RNA (MAQCA/UHRR) and Human Brain Reference RNA (MAQCB/HBR) [11] [5]. For detecting subtle differential expression, newer materials like the Quartet reference samples are also valuable [5].

- Spike-In Controls: Synthetic RNA controls from the External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) should be spiked into samples prior to library preparation. These provide a built-in truth set for evaluating quantification accuracy and dynamic range [5].

- Tissue/Cell Selection: Use the same biological source material for both RNA-seq and qPCR assays. If a gene panel is the focus, ensure that the relevant genes are robustly expressed in the chosen tissue. For instance, one study found that over 79% of genes in an intellectual disability and epilepsy panel were expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [22].

- Replication: Include multiple technical and biological replicates to account for variability and enable robust statistical analysis.

Data Processing and Analysis

- qPCR Data Normalization: Use standard curve methods or the comparative Cq (ΔΔCq) method for qPCR analysis. Normalize Cq values to multiple stable reference genes.

- RNA-seq Alignment & Quantification: As shown in Table 1, multiple workflows perform well. STAR is a widely used aligner, and quantification can be done at the gene level (e.g., with HTSeq) or transcript level (e.g., with Salmon or Kallisto). For standard gene-level DE analysis, STAR-HTSeq and pseudoaligners are excellent choices [11] [20].

- Expression Filtering: Filter out lowly expressed genes prior to comparative analysis. A common threshold is a minimum of 0.1 TPM or 10 raw counts in a sufficient number of samples [11] [23].

- Differential Expression Testing: For count-based data (from HTSeq, Salmon, etc.), use tools like DESeq2 or edgeR. For FPKM-based data (from Cufflinks), Cuffdiff2 can be used [20].

- Defining "Truth" and Calculating Metrics: Use the qPCR measurements as the benchmark. Calculate Pearson correlation of log2(TPM) values from RNA-seq with normalized Cq values from qPCR for expression correlation. For DE, calculate log2 fold-changes for both methods and assess their correlation and concordance based on significance calls.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following reagents, tools, and resources are essential for conducting robust comparisons of RNA-seq and qPCR performance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

| Category | Item | Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | MAQC (UHRR, HBR) RNA [11] [5] | Provides well-characterized, stable RNA samples with known expression profiles for platform calibration. |

| Quartet RNA Reference Materials [5] | Enables assessment of performance in detecting subtle differential expression between biologically similar samples. | |

| Spike-In Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix [5] | A set of 92 synthetic RNAs with known concentrations spiked into samples to evaluate quantification accuracy, sensitivity, and dynamic range. |

| Clinically Accessible Tissues (CATs) | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) [21] [22] | A minimally invasive tissue source; expresses a high percentage of genes from disease panels (e.g., ~80% for neurodevelopmental disorders). |

| Fibroblasts / Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines (LCLs) [22] [24] | Renewable cell sources suitable for functional assays and studying splicing defects or allele-specific expression. | |

| Critical Bioinformatics Tools | Pseudoaligners (Kallisto, Salmon) [11] | Fast, alignment-free tools for transcript quantification. Show high correlation with qPCR. |

| Aligner-Quantifiers (STAR-HTSeq) [11] | Alignment-based pipelines that provide high precision for gene-level differential expression analysis. | |

| Differential Analysis Tools (DESeq2, edgeR) [20] | Statistical packages for identifying differentially expressed genes from count-based data. | |

| Sashimi Plot Visualizations (ggsashimi) [24] | Visualizes RNA-seq read alignment across exon junctions, crucial for validating suspected splicing defects. |

The benchmarking of RNA-seq against qPCR using expression correlation and differential expression performance confirms that RNA-seq is a highly accurate and reliable technology for transcriptome analysis. When best practices are followed—including the use of standardized reference materials, appropriate bioinformatic workflows, and expression-level filtering—RNA-seq can achieve greater than 90% concordance with qPCR in fold-change detection [11]. However, researchers must remain aware of specific challenges, such as the accurate quantification of genes with low expression levels or those located in complex genomic regions like the MHC locus [21] [11]. For clinical applications, where detecting subtle expression differences is critical, quality control using reference materials designed for this purpose (e.g., Quartet samples) is strongly recommended [5]. Ultimately, the choice of RNA-seq workflow should be guided by the specific research question, available computing resources, and the need for gene-level versus transcript-level resolution. The data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a foundation for making these informed decisions.

The transition of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) from a research tool to a clinical diagnostic method requires demonstrating high reliability and cross-laboratory consistency, particularly for detecting subtle differential expression between similar biological states [5]. Foundational studies utilizing well-characterized reference materials have been instrumental in assessing the technical performance of transcriptomic technologies. The MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project, followed more recently by the Quartet Project, have generated comprehensive benchmark datasets and systematic frameworks for evaluating RNA-seq workflows [5] [11]. These initiatives provide critical insights into how experimental protocols and bioinformatics pipelines influence gene expression measurements, establishing best practices for the field.

This guide objectively compares the reference materials from these landmark projects, detailing their experimental designs, key findings regarding RNA-seq performance, and implications for detecting differential expression. By synthesizing data from multiple large-scale studies, we provide researchers with a structured comparison of these foundational resources and their applications in benchmarking RNA-seq analysis workflows against the gold standard of qPCR.

The MAQC Project

The MAQC project was a landmark effort assessing the reproducibility of microarray and sequencing technologies using two well-characterized RNA samples: MAQC-A (Universal Human Reference RNA, a pool of 10 cell lines) and MAQC-B (Human Brain Reference RNA) [11] [16]. These samples exhibit large biological differences, making them suitable for initial platform validation and ongoing quality control. The project design included matching TaqMan RT-qPCR data for numerous genes, providing a robust benchmark for evaluating gene expression measurements from different technologies [11] [16].

The Quartet Project

The Quartet Project represents a next-generation approach to quality control, utilizing multi-omics reference materials derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family of parents and monozygotic twin daughters [5] [25]. This design includes four well-characterized samples with small inter-sample biological differences that more closely mimic the subtle expression variations observed between different disease subtypes or stages [5]. The project incorporates multiple types of "ground truth," including built-in truths from known mixing ratios of samples and external reference datasets, enabling comprehensive assessment of transcriptome profiling accuracy [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Reference Material Projects

| Characteristic | MAQC Project | Quartet Project |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Samples | MAQC-A (Universal Human Reference RNA), MAQC-B (Human Brain Reference RNA) | Four samples from a family quartet (F7, M8, D5, D6) + defined mixture samples (T1, T2) |

| Nature of Biological Differences | Large differences between distinct tissue/cell types | Subtle differences between genetically related individuals |

| Primary Application | Platform validation, ongoing quality control | Assessing sensitivity for clinically relevant subtle differential expression |

| Ground Truth | TaqMan RT-qPCR datasets [11] | Multiple reference datasets, built-in truths from mixing ratios, ERCC spike-in controls [5] |

| Sample Stability | Well-established | Long-term stability monitoring integrated (15 months proteomics data) [25] |

Experimental Protocols

MAQC Experimental Protocol: The MAQC study utilized RNA samples with accompanying TaqMan RT-qPCR data for validation. Researchers typically extracted RNA from MAQC-A and MAQC-B samples, performed library preparation using various protocols (including both one-color and two-color platforms for microarray components), and conducted sequencing on available platforms [26] [16]. Bioinformatics workflows included alignment tools (TopHat, STAR), quantification methods (HTSeq, Cufflinks), and normalization approaches (FPKM, TPM) to derive gene expression estimates [11] [16].

Quartet Experimental Protocol: The Quartet project employed a distributed design where identical aliquots of reference materials were sent to multiple laboratories (45 for transcriptomics). Each laboratory performed RNA extraction, library preparation (with variations in mRNA enrichment, strandedness protocols), and sequencing on their preferred platforms [5]. Spike-in ERCC RNA controls were added to specific samples to enable absolute quantification assessment. For data analysis, both standardized pipelines and laboratory-specific workflows were applied, encompassing 26 experimental processes and 140 bioinformatics pipelines for comprehensive evaluation [5].

Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Workflows

Accuracy of Gene Expression Quantification

Studies comparing RNA-seq workflows against qPCR benchmarks have revealed important patterns in quantification accuracy. When comparing relative expression measurements (fold changes) between MAQC-A and MAQC-B samples, multiple RNA-seq workflows showed high concordance with qPCR data, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent differential expression calls between RNA-seq and qPCR [11]. The correlation coefficients for expression fold changes between RNA-seq and qPCR ranged from 0.927 to 0.934 across different workflows, demonstrating generally strong agreement [11].

Different quantification tools show varying performance characteristics. One study reported that HTSeq exhibited the highest correlation with RT-qPCR measurements (R²=0.85-0.89), though it produced greater root-mean-square deviation from qPCR values compared to other tools [16]. Pseudoalignment tools like Salmon and Kallisto demonstrated performance comparable to alignment-based methods, with correlation coefficients of approximately 0.93 for fold-change comparisons [11].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows Against qPCR Benchmarks

| Analysis Workflow | Expression Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Fold Change Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Non-concordant Genes | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 [11] | 0.934 [11] | 15.1% [11] | High fold-change correlation but may produce greater deviation from qPCR values [16] |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 [11] | 0.933 [11] | ~15% (inferred) | Nearly identical to Tophat-HTSeq, minimal mapper impact [11] |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 [11] | 0.927 [11] | ~16% (inferred) | Transcript-level quantification, slightly lower correlation |

| Kallisto | 0.839 [11] | 0.930 [11] | ~17% (inferred) | Fast pseudoalignment, performance comparable to alignment methods |

| Salmon | 0.845 [11] | 0.929 [11] | 19.4% [11] | Highest expression correlation but highest non-concordance [11] |

Detection of Subtle Differential Expression

The Quartet Project revealed significant challenges in detecting subtle differential expression across laboratories. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on principal component analysis demonstrated that smaller intrinsic biological differences among Quartet samples were more challenging to distinguish from technical noise compared to the large differences in MAQC samples [5]. The average SNR values for Quartet samples (19.8) were substantially lower than for MAQC samples (33.0), with 17 of 45 laboratories producing low-quality data (SNR < 12) for the subtle differential expression condition [5].

Inter-laboratory variation was significantly more pronounced when analyzing Quartet samples compared to MAQC samples. Experimental factors including mRNA enrichment protocols, library strandedness, and each step in bioinformatics pipelines emerged as primary sources of variation [5]. This highlights the critical importance of standardized protocols when aiming to detect clinically relevant subtle expression differences.

Identification of Problematic Genes

Benchmarking studies have consistently identified specific gene sets that show inconsistent expression measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR. These method-specific inconsistent genes typically share common characteristics: they are smaller, have fewer exons, and are lower expressed compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [11]. A significant proportion of these problematic genes are reproducibly identified across independent datasets, suggesting systematic technological discrepancies rather than random errors [11].

Best Practice Recommendations

Experimental Design Considerations

Based on findings from both projects, the following experimental design considerations are recommended:

- Reference Material Selection: Use MAQC-style references for platform validation and initial quality control, but incorporate Quartet-like materials when assessing sensitivity to subtle expression differences [5].

- Spike-in Controls: Include ERCC RNA spike-in controls to monitor technical performance and enable absolute quantification assessment [5].

- Replication: Implement appropriate technical replication to distinguish biological signals from technical noise, particularly when studying subtle expression differences [5].

- Protocol Standardization: Prioritize consistent mRNA enrichment and library preparation methods across samples in a study to minimize technical variation [5].

Bioinformatics Pipeline Selection

- Quantification Tools: Select quantification tools based on priority of metrics; HTSeq for maximum correlation, but consider RSEM or IsoEM for potentially higher accuracy despite slightly lower correlation [16].

- Normalization Methods: Implement appropriate normalization strategies accounting for gene length and sequencing depth (FPKM, TPM) when comparing expression across samples [16].

- Quality Metrics: Incorporate signal-to-noise ratio calculations to identify potential quality issues, particularly for studies of subtle differential expression [5].

- Problematic Gene Filtering: Exercise caution when interpreting results for small, low-expressed genes with few exons, as these are more prone to inaccurate quantification [11].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reference Materials and Reagents for Transcriptomics Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| MAQC Reference Samples | Benchmarking platform performance, validating RNA-seq workflows | Large biological differences between samples, well-characterized with TaqMan qPCR data [11] |

| Quartet Reference Materials | Assessing sensitivity to subtle differential expression, cross-laboratory standardization | Small biological differences between genetically related samples, built-in truths from known relationships [5] |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Monitoring technical performance, enabling absolute quantification | Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations, added to samples before library preparation [5] |

| TaqMan qPCR Assays | Establishing ground truth for gene expression measurements | High-accuracy validation method for subset of genes, used for benchmarking high-throughput data [11] |

| Standardized RNA-seq Protocols | Minimizing technical variation across experiments and laboratories | Detailed methodologies for library preparation, sequencing, and analysis [5] |

The MAQC and Quartet Projects provide complementary resources for benchmarking RNA-seq workflows against qPCR data. While the MAQC reference materials remain valuable for platform validation and quality control, the Quartet samples address the critical need for assessing performance in detecting subtle differential expression more relevant to clinical applications [5]. The comprehensive benchmarking data from these initiatives demonstrate that both experimental and computational factors significantly impact RNA-seq accuracy and reproducibility. Researchers should select reference materials and analysis workflows aligned with their specific experimental goals, particularly considering whether they require detection of large or subtle expression differences. Continued development and implementation of such reference materials will be essential as RNA-seq progresses toward routine clinical application.

A Methodological Deep Dive: From RNA-Seq Workflows to qPCR Validation

The analysis of bulk RNA-seq data fundamentally relies on computational workflows to quantify gene expression from sequencing reads. These methods have converged into two dominant paradigms: alignment-based workflows and pseudoalignment approaches [11] [27]. Alignment-based methods, considered the traditional approach, involve mapping sequencing reads directly to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2, followed by counting reads that map to specific genomic features [28] [29]. In contrast, pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon employ a fundamentally different strategy by breaking reads into k-mers and matching them to a pre-indexed transcriptome without performing base-by-base alignment, thereby achieving substantial gains in computational efficiency [30] [27].

The selection between these approaches carries significant implications for downstream analyses, including differential expression testing, with performance varying based on experimental design and biological context [28] [11]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these workflow categories, emphasizing empirical performance data derived from controlled benchmarking studies that utilize qPCR validation as a ground truth standard. Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of each approach enables researchers to select optimal strategies for their specific experimental requirements and biological questions.

Workflow Architecture and Fundamental Differences

The architectural differences between alignment-based and pseudoalignment workflows stem from their divergent approaches to handling sequencing reads. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural distinctions between these two paradigms:

Alignment-based workflows employ a sequential, multi-step process that begins with quality control of raw sequencing data, including adapter trimming and quality filtering using tools such as Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp [7] [31]. The core alignment step utilizes splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2 to map reads to a reference genome, accommodating intron-spanning reads through specialized algorithms [29] [27]. This generates alignment files (BAM format) that undergo post-alignment quality assessment before read quantification with tools such as featureCounts or HTSeq, which count reads overlapping genomic features defined in annotation files [28] [16].

Pseudoalignment methods fundamentally streamline this process by eliminating the explicit alignment step. Tools like Kallisto and Salmon first build a transcriptome index from reference sequences, then employ k-mer-based matching to rapidly determine transcript compatibility for each read [30] [27]. Kallisto utilizes a "pseudoalignment" algorithm that ascertains whether reads could have originated from particular transcripts without determining base-level alignment coordinates, while Salmon implements "quasi-mapping" with additional bias correction models for sequence-specific and GC-content biases [28] [27]. This approach directly generates transcript abundance estimates in TPM (Transcripts Per Million) format, bypassing the intermediate alignment files entirely.

Performance Benchmarking Against qPCR Standards

Experimental Design for Method Validation

Robust benchmarking of RNA-seq quantification workflows requires carefully designed experiments that enable comparison against ground truth measurements. The Microarray Quality Control (MAQC) consortium has established reference RNA samples that serve as community standards for this purpose [28] [11]. These include Universal Human Reference RNA (MAQCA) and Human Brain Reference RNA (MAQCB), which are frequently mixed in known ratios (samples C and D) to create samples with predetermined expression fold-changes [28]. This design enables calculation of expected differential expression values for validation.

In comprehensive benchmarking studies, RNA-seq data derived from these reference samples are processed through multiple alignment-based and pseudoalignment workflows, with resulting expression measurements compared against quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) data generated for thousands of genes [11]. This experimental approach provides orthogonal validation through a method widely regarded as the gold standard for gene expression quantification [11] [31]. The qPCR validation typically encompasses 13,000-18,000 protein-coding genes, offering transcriptome-wide assessment of quantification accuracy [11]. Performance metrics include expression correlation coefficients (R²) between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements, root mean square error (RMSE) calculations, and concordance in differential expression detection between technically validated methods [28] [11] [16].

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

The following table summarizes key performance metrics derived from controlled benchmarking studies that utilized qPCR validation as ground truth:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Workflows Against qPCR Validation

| Workflow | Expression Correlation (R²) with qPCR | Fold-Change Correlation (R²) with qPCR | Quantification Bias | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821-0.827 [11] | 0.933-0.934 [11] | Moderate | Robust for small RNAs and low-expression genes [28] | Computationally intensive; longer processing time [30] |

| Salmon | 0.845 [11] | 0.929 [11] | Low to moderate | Fast processing; good for large datasets [27] | Reduced accuracy for small RNAs [28] |

| Kallisto | 0.839 [11] | 0.930 [11] | Low to moderate | Extremely fast with low memory usage [30] | Systematic underperformance with low-abundance genes [28] |

| HISAT2-featureCounts | 0.827-0.872 [28] [7] | 0.920-0.935 [28] [7] | Moderate | Balanced performance across diverse RNA biotypes [28] | Intermediate computational requirements [7] |

When assessing differential expression detection, benchmarking studies reveal that approximately 85% of genes show consistent differential expression calls between RNA-seq workflows and qPCR data [11]. The alignment-based methods (STAR-HTSeq, HISAT2-featureCounts) demonstrate slightly better concordance (85.1-85.3%) compared to pseudoaligners (83.1-84.9%) when comparing MAQCA and MAQCB samples [11]. However, it is important to note that the majority of discordant genes (93%) show relatively small fold-change differences (ΔFC < 2) between methods [11].

Specialized Performance Considerations

Performance differences between workflow categories become more pronounced for specific biological contexts. Alignment-based methods significantly outperform pseudoaligners for small structured non-coding RNAs (tRNAs, snoRNAs) and low-abundance transcripts, demonstrating superior accuracy in total RNA-seq contexts where these RNA biotypes are represented [28]. This performance gap is attributed to the fundamental k-mer-based approach of pseudoaligners, which may not adequately handle the distinct characteristics of small RNAs.

The following table summarizes context-specific performance considerations:

Table 2: Context-Dependent Performance of RNA-Seq Workflow Categories

| Experimental Context | Alignment-Based Performance | Pseudoalignment Performance | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small RNA Quantification | Superior accuracy for tRNAs, snoRNAs, and other small structured RNAs [28] | Systematically poorer performance; potential for quantification inaccuracies [28] | Alignment-based recommended for total RNA-seq including small RNAs |

| Low-Abundance Genes | More robust detection and quantification [28] [11] | Reduced accuracy; higher rate of dropouts for low-expression genes [28] | Alignment-based preferred for studies focusing on lowly-expressed targets |

| Large-Scale Studies | Computationally challenging for thousands of samples [27] | Ideal for processing thousands of samples efficiently [27] | Pseudoalignment recommended when processing large sample batches |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Capable of identifying novel splice variants and unannotated features [29] | Limited to previously annotated transcriptomes [27] | Alignment-based essential for discovery-oriented research |

For standard protein-coding gene quantification, both workflow categories demonstrate high agreement with qPCR validation data, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.82-0.85 for expression levels and 0.93-0.94 for fold-change measurements [11]. This suggests that for common differential expression analyses focusing on mRNA, the choice between paradigms may be driven primarily by practical considerations rather than absolute performance differences.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Reference Sample Preparation

Benchmarking studies typically utilize well-characterized reference RNA samples to establish ground truth measurements. The MAQC consortium reference samples (Universal Human Reference RNA and Human Brain Reference RNA) are commonly employed, with preparation following standardized protocols [11] [16]. These samples are typically processed using the TGIRT (thermostable group II intron reverse transcriptase) protocol for RNA-seq library preparation, which enables more comprehensive recovery of full-length structured small non-coding RNAs alongside long RNAs in a single library workflow [28]. For qPCR validation, total RNA is reverse transcribed using oligo-dT primers or random hexamers, followed by amplification with TaqMan assays designed against protein-coding genes of interest [11] [31].

RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

RNA-seq libraries are prepared following standardized protocols such as the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA protocol, with sequencing typically performed on Illumina platforms to generate paired-end reads (2×101 bp) at sufficient depth (20-30 million reads per sample) to ensure statistical power for quantification accuracy assessment [31]. Quality control steps include RNA integrity measurement (RIN > 7.0) using Agilent Bioanalyzer and quantification via fluorometric methods to ensure input material quality [29].

Data Processing Protocols

For alignment-based workflows, the typical protocol involves:

- Read trimming using Trimmomatic or fastp with quality threshold Q>20 and minimum read length 50 bp [31]

- Alignment using STAR or HISAT2 with genome index and annotation GTF file [28] [27]

- Read quantification with featureCounts or HTSeq using "union" or "intersection-nonempty" modes [16]

- Generation of count matrices for downstream analysis

For pseudoalignment workflows, the standard protocol includes:

- Transcriptome index generation from reference FASTA and GTF files [27]

- Quantification using Kallisto or Salmon with bias correction flags enabled [28]

- Generation of transcript-level TPM values and estimated counts

- Aggregation to gene-level counts when necessary [11]

qPCR Validation Methodology

qPCR validation follows established best practices with:

- Reverse transcription of total RNA using SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System [31]

- Amplification with TaqMan assays in technical duplicates [11]

- Normalization using global median normalization approach for Ct values [31]

- Calculation of relative expression using ΔΔCt method with stable reference genes [31]

Table 3: Essential Resources for RNA-Seq Workflow Implementation

| Category | Resource | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | MAQC Reference RNAs (UHRR, HBRR) | Benchmarking standards for method validation | Universal Human Reference RNA, Human Brain Reference RNA [11] |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit | RNA-seq library construction | Includes ribosomal depletion, fragmentation, adapter ligation [31] |

| qPCR Validation | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Target-specific amplification for validation | FAM-labeled probes, pre-optimized for 18,080 protein-coding genes [11] |

| Computational Tools | nf-core/rnaseq | Automated pipeline for reproducible analysis | Incorporates STAR, Salmon, quality control metrics [27] |

| Alignment Software | STAR | Spliced alignment to reference genome | Requires genome index, handles junction mapping [27] |

| Pseudoalignment Software | Kallisto | Rapid transcript quantification | Uses k-mer matching, outputs TPM values [30] |

| Quality Control | FastQC | Quality assessment of sequencing data | Evaluates base quality, adapter contamination, GC content [32] |

Empirical benchmarking against qPCR validation reveals that both alignment-based and pseudoalignment RNA-seq workflows provide accurate gene expression quantification for standard protein-coding genes, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.82 for expression levels and 0.93 for fold-change measurements [11]. However, significant performance differences emerge for specific biological contexts, with alignment-based methods demonstrating superior capabilities for small RNA quantification and detection of low-abundance transcripts [28].

For researchers working with total RNA samples that include structured small RNAs, or when studying lowly-expressed genes, alignment-based workflows (STAR-HTSeq, HISAT2-featureCounts) provide more robust and accurate quantification [28]. For large-scale studies prioritizing processing efficiency with standard mRNA quantification, pseudoalignment tools (Salmon, Kallisto) offer excellent performance with substantially reduced computational requirements [30] [27]. A hybrid approach utilizing STAR alignment followed by Salmon quantification provides comprehensive quality assessment alongside efficient quantification, balancing the strengths of both paradigms [27].

The continuing evolution of both workflow categories ensures that benchmarking against orthogonal validation methods like qPCR remains essential for methodological advancements in RNA-seq analysis, ultimately enabling more accurate biological insights from transcriptomic studies.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification, enabling researchers to explore genetic regulatory networks and identify novel transcripts with unprecedented detail [11] [7]. As the technology has proliferated, so too has the complexity of analytical workflows designed to derive biological insights from sequencing data. These workflows generally fall into two methodological categories: alignment-dependent approaches that map reads to a reference genome (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks) and alignment-free methods that directly assign reads to transcripts using k-mer-based strategies (e.g., Kallisto, Salmon) [11]. Despite the critical importance of tool selection for research outcomes, the field lacks a standardized analysis pipeline, presenting researchers with a challenging decision landscape.

Benchmarking studies traditionally relied on simulated data or validation with limited numbers of genes, but these approaches fail to capture the full complexity of real biological systems [11]. The most rigorous evaluations now utilize whole-transcriptome reverse transcription quantitative PCR (qPCR) data, which provides a trusted ground truth for method validation [15] [11]. This article presents a comprehensive benchmark of five popular RNA-seq analysis workflows—STAR-HTSeq, Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, Kallisto, and Salmon—evaluated against extensive qPCR datasets. By synthesizing evidence from multiple independent studies, we provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with data-driven guidance for selecting appropriate tools based on their specific research objectives and computational constraints.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Reference Datasets and qPCR Ground Truth

To ensure robust benchmarking, the evaluated studies utilized well-characterized RNA reference samples, primarily the MAQCA (Universal Human Reference RNA) and MAQCB (Human Brain Reference RNA) from the MAQC-I consortium [11]. These samples represent carefully controlled transcript mixtures that provide a consistent benchmark across laboratories and analytical methods. The key innovation in recent benchmarking efforts involves using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR assays targeting all protein-coding genes (approximately 18,080 genes) as validation data, moving beyond the limited gene sets that constrained earlier studies [11].

The qPCR data processing required careful alignment between transcripts detected by qPCR assays and those quantified by RNA-seq workflows. For transcript-level tools (Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon), gene-level TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values were calculated by aggregating transcript-level TPM values of transcripts detected by the respective qPCR assays [11]. For count-based workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, STAR-HTSeq), gene-level counts were converted to TPM values to enable cross-method comparison. To minimize bias from lowly expressed genes, researchers applied a minimal expression filter of 0.1 TPM across all samples and replicates [11].

Benchmarking Workflow Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive experimental approach used to evaluate the five RNA-seq workflows against qPCR validation data:

Experimental Workflow for RNA-Seq Tool Benchmarking. The diagram illustrates the comprehensive approach used to evaluate five RNA-seq workflows against qPCR validation data. RNA-seq raw reads are processed through either alignment-based or alignment-free methods, followed by gene/transcript quantification. Results are compared against qPCR data using multiple performance metrics.

Performance Evaluation Metrics

The benchmarking studies employed multiple complementary metrics to evaluate workflow performance:

- Expression Correlation: Pearson correlation between normalized RT-qPCR Cq-values and log-transformed RNA-seq expression values (TPM) for the same samples [11].

- Fold Change Correlation: Pearson correlation of gene expression fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples calculated from RNA-seq versus qPCR data [11].

- Rank Difference Analysis: Transformation of TPM and normalized Cq-values to gene expression ranks with calculation of absolute rank differences to identify outlier genes [11].

- Differential Expression Concordance: Classification of genes into concordant and non-concordant groups based on agreement between RNA-seq and qPCR differential expression calls [11].

- Computational Efficiency: Measurement of computational resource requirements including memory usage, processing time, and alignment rates [33] [34].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential reagents and resources used in the benchmark experiments:

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Provide standardized transcript mixtures for cross-method comparison | MAQCA (Universal Human Reference RNA), MAQCB (Human Brain Reference RNA) [11] |

| Reference Genomes/Annotations | Foundation for read alignment and transcript quantification | Ensembl release 75 (GRCh37/hg19) genome assembly, cDNA, and non-coding RNA sequences [33] |

| Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Assays | Generate validation data with coverage of protein-coding transcriptome | Assays targeting ~18,080 protein-coding genes [11] |

| Alignment-Based Tools | Map RNA-seq reads to reference genome | STAR [11], Tophat [11], HISAT2 [34] with various quantification approaches |

| Alignment-Free Tools | Direct transcript assignment without full alignment | Kallisto [11], Salmon [11] using k-mer-based pseudoalignment |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess read quality and preprocessing needs | FastQC [7], Fastp [7], Trim Galore [7] for quality metrics and adapter trimming |

Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Workflows

Expression Quantification Accuracy

When comparing gene expression values against qPCR measurements, all five workflows showed high correlation, though alignment-free methods demonstrated slightly superior performance. Salmon achieved the highest expression correlation (R² = 0.845), closely followed by Kallisto (R² = 0.839) [11]. Among alignment-based methods, Tophat-HTSeq (R² = 0.827) and STAR-HTSeq (R² = 0.821) showed comparable performance, while Tophat-Cufflinks had the lowest correlation (R² = 0.798) [11]. These results suggest that pseudoalignment methods provide marginally better agreement with qPCR measurements for absolute expression quantification.

A notable finding across all workflows was the identification of systematic discrepancies between technologies. Each method revealed a specific gene set (407-591 genes) with inconsistent expression measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR [11]. These "rank outlier genes" significantly overlapped across workflows and were characterized by significantly lower expression levels, suggesting that technological differences rather than algorithmic limitations explain most discrepancies.

Differential Expression Analysis Performance

For most research applications, accurate detection of differential expression between conditions represents the primary analytical goal. All workflows showed excellent fold change correlation with qPCR data (R² > 0.92), with minimal practical differences between methods [11]. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance metrics:

| Workflow | Expression Correlation (R²) | Fold Change Correlation (R²) | Non-Concordant Genes | Major Discordant Genes (ΔFC>2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% | 1.6% |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 16.9% | 1.4% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 17.4% | 1.4% |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% | 1.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% | 1.2% |

Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Workflows Against qPCR Validation. Expression correlation indicates Pearson correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR expression values. Fold change correlation represents Pearson correlation of gene expression changes between samples. Non-concordant genes show disagreement in differential expression calls. Major discordant genes have fold change differences >2 between methods [11].

When comparing differential expression calls between MAQCA and MAQCB samples, alignment-based methods (Tophat-HTSeq, STAR-HTSeq) showed a slightly lower fraction of non-concordant genes (15.1-15.3%) compared to pseudoaligners (16.9-19.4%) [11]. However, the majority of non-concordant genes showed relatively small fold change differences (ΔFC < 1), with only 1.1-1.6% of genes exhibiting major discrepancies (ΔFC > 2) [11]. This suggests that while the choice of workflow affects the specific genes identified as differentially expressed, the overall biological interpretation would likely be similar across methods.

Computational Efficiency and Resource Requirements

Computational performance varied substantially between workflows, with important implications for researchers with limited computational resources or processing large datasets. Kallisto-Sleuth demanded the least computing resources, while Cufflinks-Cuffdiff required the most substantial investment [34]. Salmon and Kallisto typically completed quantification within minutes, offering significant speed advantages over alignment-based methods [33].

Studies noted that HISAT2-StringTie-Ballgown showed higher sensitivity for genes with low expression levels, while Kallisto-Sleuth proved most effective for medium to highly expressed genes [34]. This differential performance across expression ranges suggests that research priorities should inform tool selection—if studying low-abundance transcripts is crucial, alignment-based methods may be preferable.

Technical Protocols and Implementation

Alignment-Based Workflow Implementation

For STAR-HTSeq and Tophat-HTSeq pipelines, the standard implementation begins with quality control checks using tools like FastQC or Fastp [7]. While some studies have questioned the necessity of trimming [33], quality assessment remains critical for detecting potential issues. The alignment step typically uses STAR or Tophat with reference genome indices, followed by read quantification with HTSeq-count using appropriate parameters for stranded libraries [11].

A critical consideration for alignment-based methods is the handling of multimapping reads. HTSeq employs a default strategy of discarding reads that align to multiple positions, while alternative tools like Rcount assign weights to each alignment [34]. For studies where paralogous genes or gene families are of interest, this handling strategy may significantly impact results and should be carefully considered.

Alignment-Free Workflow Implementation