Beyond Housekeeping: The Critical Role of Reference Genes in Accurate qPCR Normalization

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone of gene expression analysis in biomedical and biological research, but its accuracy is entirely dependent on proper normalization.

Beyond Housekeeping: The Critical Role of Reference Genes in Accurate qPCR Normalization

Abstract

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone of gene expression analysis in biomedical and biological research, but its accuracy is entirely dependent on proper normalization. This article provides a comprehensive guide to reference genes, detailing their foundational importance, the methodologies for their selection and application, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous validation protocols. Drawing on recent, high-impact studies across diverse organisms—from wheat and sweet potato to human tongue carcinoma and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—we synthesize current best practices to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals avoid costly errors and generate reliable, reproducible gene expression data.

Why Your Housekeeping Gene is Failing You: The Foundational Importance of Reference Genes

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) stands as one of the most sensitive and reliable techniques for gene expression analysis. However, its accuracy is critically dependent on the careful control of technical variability introduced during experimental workflows. This technical guide elaborates on the principle of normalization as a fundamental process to correct for this non-biological variation, ensuring that observed differences in gene expression reflect true underlying physiology. Framed within the critical context of reference gene research, this paper details the necessity of using stable, validated internal controls for rigorous qPCR experimentation. We provide a comprehensive overview of standard normalization methodologies, with a particular focus on the selection and validation of reference genes using multiple algorithmic approaches, and present summarized experimental data and protocols to aid researchers and drug development professionals in implementing these practices.

The exquisite sensitivity of qPCR, which allows for the detection of minute quantities of nucleic acids, also renders it susceptible to substantial technical noise. This variability can arise from multiple sources throughout the experimental process, including differences in RNA integrity and concentration across samples, inefficiencies in cDNA synthesis, variations in pipetting accuracy, and inconsistencies in PCR amplification efficiency [1] [2]. Without proper correction, these technical artifacts can obscure true biological differences or create false positives, leading to invalid conclusions.

Normalization is the statistical process of correcting for this technical variation to allow for accurate biological comparisons. The primary goal is to distinguish true changes in target gene expression from non-biological fluctuations. Among the various normalization strategies, the use of internal control genes, or reference genes, has become the most prevalent method for relative quantification in qPCR studies [3] [4]. This method relies on the stability of the reference gene's expression across all samples and experimental conditions within the study. The validity of the entire experiment hinges on the fundamental assumption that the expression of this control gene remains constant, making the informed selection and rigorous validation of these genes arguably the most critical step in the qPCR workflow.

The Critical Role of Reference Genes in Normalization

Reference genes, traditionally referred to as "housekeeping genes," are presumed to maintain consistent expression levels regardless of experimental conditions. They serve as an internal baseline, allowing researchers to adjust for variations in the amount of starting material, sample quality, and overall cDNA synthesis efficiency between different samples [3].

The use of an unstable reference gene for normalization can introduce significant error and lead to misleading biological interpretations. For instance, in a study on wheat, expression analysis of a developmentally expressed gene, TaIPT5, showed significant differences between absolute and normalized values in most tissues when an inappropriate reference was considered. However, normalization using validated reference genes Ref 2 and Ta3006 produced consistent and reliable results [3]. This underscores that the classic concept of "housekeeping" genes is often flawed; the expression of many commonly used references, such as GAPDH and β-actin, can vary significantly with experimental treatment, tissue type, and developmental stage [1] [3]. Consequently, the practice of selecting a reference gene based solely on convention or literature from dissimilar systems is strongly discouraged. Instead, reference genes must be empirically validated for each specific experimental system.

Methodologies for Reference Gene Selection and Validation

A robust validation process involves selecting a panel of candidate reference genes and evaluating their expression stability across the entire set of experimental samples. This process leverages specific algorithms to rank the candidates based on their stability.

Selection of Candidate Genes

The first step is to assemble a panel of candidate genes. These are often selected from scientific literature, with studies in related species or conditions serving as a starting point. For example, a sweet potato study selected its candidate panel by evaluating five previous studies and choosing the six best-classified genes (IbCYC, IbARF, IbTUB, IbUBI, IbCOX, and IbEF1α), while also including four commonly used genes (IbPLD, IbACT, IbRPL, and IbGAP) for comparison [1].

Stability Analysis with Statistical Algorithms

The expression stability of the candidate genes is then analyzed using specialized algorithms. Using multiple algorithms provides a more comprehensive assessment, as each employs a different statistical approach [1] [3]. The most widely used tools include:

- geNorm: This algorithm calculates a gene stability measure (M) based on the average pairwise variation between all genes in the panel. A lower M value indicates greater stability. geNorm also determines the optimal number of reference genes by calculating the pairwise variation (V) between sequential ranking steps [1] [3].

- NormFinder: This method evaluates stability by considering both intra-group and inter-group variation, making it particularly suitable for experiments with distinct sample groups [1] [3].

- BestKeeper: This algorithm utilizes the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of the raw quantification cycle (Cq) values. Genes with lower SD and CV are considered more stable [1] [3].

- RefFinder: This is a comprehensive web-based tool that integrates the results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCq method. It generates an overall final ranking of candidate genes, providing a consensus view of their stability [1].

Experimental Data and Validation

The following table summarizes the findings of two recent studies that validated reference genes in sweet potato and wheat, demonstrating how stability is tissue-specific and not guaranteed for traditional "housekeeping" genes.

Table 1: Validation of Reference Gene Stability in Different Plant Species

| Species | Experimental Context | Most Stable Reference Genes | Least Stable Reference Genes | Primary Validation Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) [1] | Different tissues (fibrous root, tuberous root, stem, leaf) | IbACT, IbARF, IbCYC | IbGAP, IbRPL, IbCOX | RefFinder |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) [3] | Various tissues of developing plants | Ta2776, Cyclophilin, Ta3006, Ref 2 (ADP-ribosylation factor) | β-tubulin, CPD, GAPDH | BestKeeper, NormFinder, geNorm, RefFinder |

The sweet potato study highlights that traditionally used genes like IbGAP (GAPDH) and IbRPL (ribosomal protein) were among the least stable, whereas IbACT (Actin) was highly stable across tissues [1]. Similarly, the wheat study found GAPDH and β-tubulin to be less reliable, while Ref 2 (ADP-ribosylation factor) and Ta3006 showed high stability [3]. These findings consistently demonstrate that stability must be tested, not assumed.

Experimental Protocol for Reference Gene Validation

The following is a detailed protocol for validating reference genes, synthesizing methodologies from cited studies.

Sample Preparation and RT-qPCR

- Design Experiment: Define all sample types (tissues, treatments, time-points) and collect a minimum of three biological replicates per group to account for biological variation [2].

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: Extract total RNA from all samples using a standardized protocol. Assess RNA integrity and quantity. Synthesize cDNA using a reverse transcription kit with a consistent amount of input RNA (e.g., 1 µg) across all samples.

- qPCR Amplification: Design and optimize primer pairs for each candidate reference gene and target of interest. Perform qPCR reactions using a suitable master mix. The reaction should include a passive reference dye (e.g., ROX) to correct for well-to-well variations [2]. Run all samples in technical triplicates to assess system precision.

Data Analysis and Stability Ranking

- Calculate Cq Values: Extract the quantification cycle (Cq) values for all reactions. The mean Cq value for each biological replicate is used for subsequent analysis.

- Assess Expression Level: Review the mean Cq values for each gene across samples to ensure they are within an acceptable range (typically ~15-30 cycles).

- Run Stability Algorithms:

- Input the Cq data matrix into the different stability analysis tools (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper).

- geNorm: The output will provide a stability measure (M) for each gene and suggest the optimal number of reference genes via the pairwise variation Vn/Vn+1. A common threshold is V < 0.15, below which the inclusion of an additional reference gene is not necessary.

- NormFinder: This will rank genes based on their stability value, with lower values indicating higher stability.

- BestKeeper: This will output a ranking based on the standard deviation (SD) of the Cq values. Genes with SD > 1 are generally considered unstable.

- Generate Consensus Ranking: Use RefFinder to compile the results from all algorithms into a comprehensive, overall ranking of gene stability.

Normalization of Target Genes

Once the most stable reference genes are identified, they can be used to normalize the expression of target genes. The most common method is the 2–ΔΔCq method [4], which involves the following steps for each sample:

- ΔCq Calculation: Calculate the difference in Cq between the target gene and the reference gene(s): ΔCq = Cq(target) – Cq(reference).

- ΔΔCq Calculation: Calculate the difference between the ΔCq of the test sample and the ΔCq of the calibrator sample (e.g., control group): ΔΔCq = ΔCq(test) – ΔΔCq(calibrator).

- Fold Change Calculation: The normalized relative fold change in expression is given by 2–ΔΔCq.

It is critical to note that the 2–ΔΔCq method assumes near-perfect and equal PCR amplification efficiencies for both the target and reference genes [4] [5]. PCR efficiency should be validated prior to using this method.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Normalization

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality, intact total RNA from tissue or cells. | Prepare input material for cDNA synthesis from all biological replicates. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. | Convert 1 µg of total RNA to cDNA for each sample under consistent conditions. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, salts, and buffer. | Provides the core components for the amplification reaction; may include SYBR Green or probe. |

| Passive Reference Dye (e.g., ROX) | An inert dye included in the master mix that provides a stable fluorescence signal. | Used by the qPCR instrument to normalize for fluorescent fluctuations not related to amplification [2]. |

| Validated Primer Assays | Sequence-specific primers for candidate reference and target genes. | Amplify specific genes; must be validated for efficiency and specificity. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Water certified to be free of RNases and DNases. | Used to dilute samples and create reaction mixes without degrading nucleic acids. |

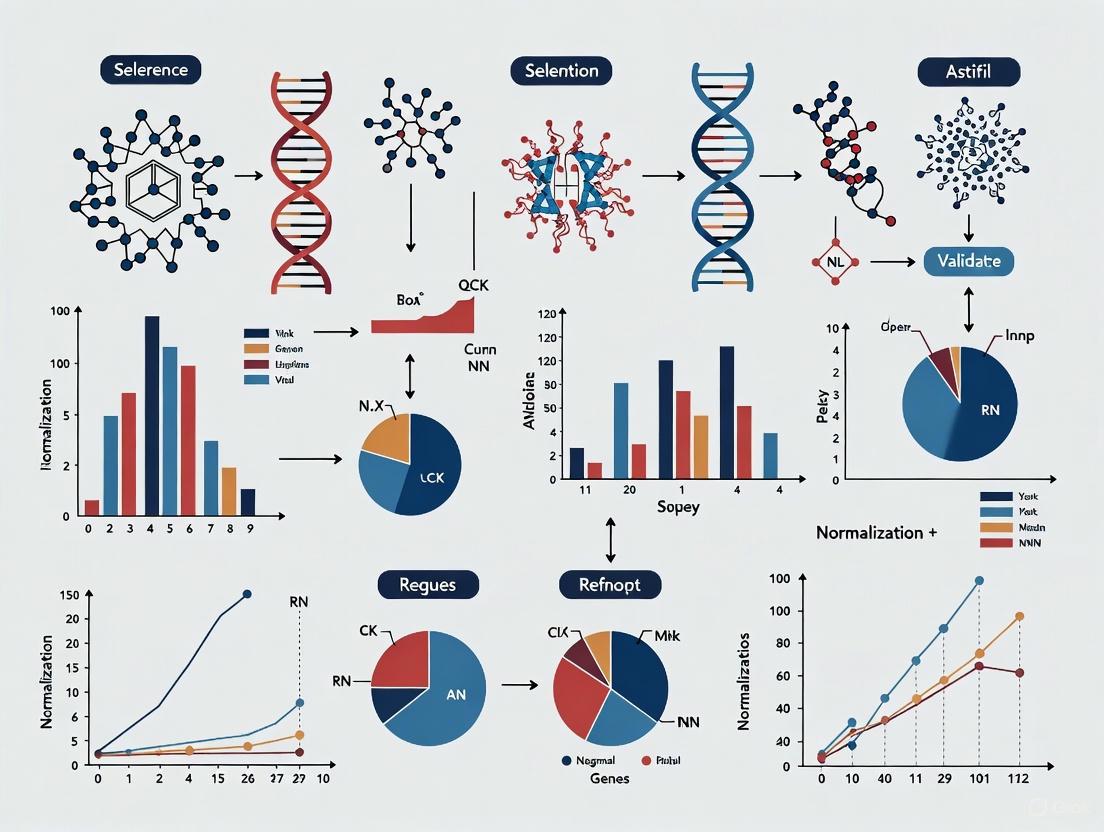

Workflow for Validating and Implementing Reference Genes

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of steps involved in the validation and use of reference genes for qPCR normalization.

Normalization to correct for technical variability is not merely a recommended step in qPCR analysis—it is an absolute prerequisite for generating accurate, reliable, and reproducible gene expression data. The principle of using internal reference genes is powerful but places the burden of proof on the researcher to demonstrate that the chosen controls are stable within their specific experimental context. As evidenced by the summarized data, the stability of a gene is not an intrinsic property; a gene that is stable in one tissue or condition may be highly variable in another. Therefore, the practice of systematic validation using a panel of candidates and multiple algorithmic tools must be integrated into the standard qPCR workflow. By adhering to these practices, researchers and drug developers can ensure that their conclusions about gene expression and its implications in drug response and disease mechanisms are built upon a solid and defensible experimental foundation.

Gene expression analysis using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has become a cornerstone of molecular biology, providing critical insights into gene regulation in diverse fields from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug development [6]. The accuracy of this technique, however, hinges entirely on proper normalization to control for technical variations in RNA quantity, quality, and reverse transcription efficiency [7]. For decades, scientists have relied on housekeeping genes (HKGs)—presumed to maintain constant expression across all tissues and experimental conditions—as internal controls for normalization [8]. Traditional HKGs such as GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), ACTB (β-actin), and 18S rRNA have been used ubiquitously based on this assumption [9] [8].

Mounting evidence now demonstrates that this assumption is fundamentally flawed. The expression of traditional HKGs is far from constant and can vary significantly with experimental conditions, tissue types, and disease states [8] [6]. This variability introduces substantial inaccuracies in gene expression quantification, potentially leading to erroneous biological interpretations and questionable research conclusions [6]. This technical review synthesizes recent evidence on the pitfalls of traditional HKGs, provides methodologies for their proper validation, and offers guidance for selecting appropriate reference genes within the broader context of robust qPCR normalization practices.

The Flawed Foundation: Why Traditional Housekeeping Genes Fail

The Myth of Constitutive Expression

The traditional concept of housekeeping genes originated from the understanding that certain cellular functions are essential for survival regardless of cell type or state [8]. These "maintenance genes" were presumed to produce a basal transcriptome necessary for fundamental cellular operations, leading to their adoption as internal controls for gene expression studies [8]. However, extensive transcriptomic analyses have revealed that gene expression is inherently dynamic, constantly responding to both internal programming and external stimuli [8].

The core problem lies in the misconception that HKGs are immune to regulatory changes. Contemporary research demonstrates that no single gene is universally stable across all experimental conditions [9]. Even genes involved in basic cellular processes are subject to regulation under different physiological and pathological states [8] [6]. A striking example comes from research on 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation, which found that reference gene expression changed over time even in non-differentiating cells, challenging the fundamental premise of invariant HKG expression [9].

Functional Complexity of Traditional HKGs

The instability of traditional HKGs becomes understandable when examining their diverse cellular roles beyond their canonical functions. GAPDH exemplifies this problem, as it participates in numerous non-glycolytic processes:

- Metabolic Regulation: Beyond glycolysis, GAPDH responds to insulin, growth hormone, and oxidative stress [8].

- Nuclear Functions: GAPDH translocates to the nucleus where it influences apoptosis, transcription, and DNA repair [8].

- Oncogenic Roles: GAPDH has been implicated in tumor survival, angiogenesis, and hypoxic tumor growth [8].

This functional pleiotropy means GAPDH expression is frequently altered in precisely those experimental conditions commonly studied—such as cancer, metabolic interventions, and stress responses—making it particularly unsuitable as a normalizer in these contexts [8].

Table 1: Multifunctional Roles of Commonly Used Traditional Housekeeping Genes

| Gene | Primary Function | Additional Roles | Regulatory Influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Glycolysis | Apoptosis, membrane fusion, transcriptional regulation, DNA repair | Insulin, oxidative stress, hypoxia, tumor suppressors |

| ACTB | Cytoskeletal structure | Cell motility, division, intracellular transport | Serum stimulation, cell density, differentiation |

| 18S rRNA | Ribosomal component | Protein synthesis | Cellular growth state, proliferation rate |

| HPRT1 | Purine salvage pathway | Neuromodulation, cell signaling | Cellular differentiation, metabolic state |

Quantitative Evidence: Documented Instability Across Biological Contexts

Instability in Disease States

Recent studies across diverse pathological conditions consistently demonstrate the unsuitability of traditional HKGs. In endometrial cancer research, GAPDH has been identified as not merely an unstable reference but actually a pan-cancer marker whose expression is altered in disease states [8]. Using GAPDH for normalization in such contexts normalizes away biologically relevant changes, potentially obscuring important disease mechanisms.

In pulmonary tuberculosis, a 2025 comprehensive evaluation of eight common HKGs across tuberculomas and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) revealed striking instability in traditional reference genes. The study employed multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt method) and found:

- GAPDH and UBC ranked as the least stable genes across both sample types [10].

- PPIA, YWHAZ, and HPRT1 formed the most stable reference panel [10].

- Normalization with inappropriate HKGs could completely reverse interpretation of cytokine expression patterns [10].

Similar findings emerged from breast cancer research, where novel HKGs (EIF4H, GHITM, ATP5F1B, BRK1, and OS9) demonstrated significantly greater stability than traditional options like GAPDH and RPLP0 across cell lines and treatment conditions [11].

Instability in Developmental and Stress Conditions

Plant studies provide particularly compelling evidence of HKG variability across developmental stages and environmental challenges. A 2025 systematic investigation in Vigna mungo evaluated 14 candidate genes across 17 developmental stages and 4 abiotic stress conditions [12]. The research revealed:

- No single HKG performed optimally across all conditions [12].

- RPS34 and RHA were most stable across developmental stages [12].

- ACT2 and RPS34 proved optimal under abiotic stress conditions [12].

This tissue- and condition-specific pattern of HKG stability has been replicated in numerous other systems. In cotton, comprehensive evaluation identified:

- GhUBQ14 and GhPP2A1 as superior references for different plant organs [13].

- GhACT4 and GhUBQ14 for flower development [13].

- GhMZA and GhPTB for fruit development [13].

Table 2: Documented Instability of Traditional Housekeeping Genes Across Experimental Conditions

| Biological Context | Traditional HKG | Evidence of Instability | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipocyte Differentiation | GAPDH, ACTB | Significant expression changes in differentiating and non-differentiating cells over time [9] | Misinterpretation of differentiation markers |

| Plant Stress Responses | Common plant HKGs | High variability under drought, salt, aluminum, and cold stress [12] | Inaccurate quantification of stress-responsive genes |

| Tuberculosis Infection | GAPDH, UBC | Least stable in tuberculomas and PBMCs [10] | Altered immune response profiles |

| Cancer Studies | GAPDH, ACTB | Active regulation in tumor tissues; pan-cancer marker [8] | Masking of genuine oncogenic expression patterns |

| Lymphocyte Activation | HPRT, ACTB | Active regulation during immune activation [6] | Skewed cytokine and activation marker profiles |

Impact on Experimental Results

The use of inappropriate HKGs generates systematic errors that propagate through data analysis, potentially leading to completely reversed biological interpretations. A seminal demonstration of this effect showed that normalization of IL-4 expression in tuberculosis patients produced opposite conclusions depending on the reference gene used [6]:

- Normalization with HuPO showed increased IL-4 expression in TB patients versus controls [6].

- Normalization with GAPDH eliminated this difference [6].

- The apparent response to anti-TB treatment changed from non-significant decrease (HuPO) to significant increase (GAPDH) [6].

Such dramatic reversals in experimental conclusions highlight how improper normalization can completely undermine research validity. These effects are particularly concerning in translational research and drug development, where molecular signatures may inform clinical decisions.

Broader Implications for Research Reproducibility

The pervasive use of unvalidated traditional HKGs contributes significantly to the reproducibility crisis in biomedical research. When different laboratories use different unvalidated reference genes to study the same biological question, they may arrive at conflicting conclusions despite using technically sound methodologies [8]. This problem is exacerbated in meta-analyses attempting to synthesize findings across multiple studies.

In clinical diagnostics, particularly in molecular classification systems like the PAM50 breast cancer subtyping assay, inappropriate normalization can lead to incorrect tumor classification, potentially affecting treatment decisions [11]. The implementation of properly validated HKGs in such contexts becomes not merely a technical concern but an issue of diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Best Practices: Validating Reference Genes for Robust Normalization

Experimental Design for HKG Validation

Proper HKG validation begins with thoughtful experimental design. Key considerations include:

- Selecting Candidate Genes: Include multiple candidates (typically 6-10) from different functional classes to reduce the chance of co-regulation [12].

- Sample Composition: Ensure test samples represent the full range of experimental conditions (tissues, treatments, time points) under investigation [12] [13].

- Technical Replicates: Include sufficient biological and technical replicates to robustly estimate variability [12] [9].

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality RNA (A260/280 ratio ~2.0-2.1) with confirmed integrity [9] [7].

- PCR Efficiency: Validate primer efficiency (90-110%) and specificity (single peak in melting curve) for all candidates [9] [10].

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for proper reference gene validation:

Statistical Algorithms for Stability Assessment

Comprehensive HKG validation requires multiple statistical approaches, as each algorithm has distinct strengths and underlying assumptions:

- geNorm: Determines the most stable genes by stepwise exclusion of the least stable candidates; provides the optimal number of reference genes through pairwise variation analysis [9] [10].

- NormFinder: Employs a model-based approach to estimate intra- and inter-group variation; particularly effective for identifying the single most stable gene [10] [14].

- BestKeeper: Uses pairwise correlation analysis based on raw Cq values; can identify genes with excessive variability [9] [10].

- ΔCt Method: Compares relative expression of gene pairs; simple yet effective for initial assessment [15] [14].

- RefFinder: Integrates all four algorithms to generate a comprehensive stability ranking [12] [10].

Table 3: Comparison of Statistical Algorithms for Reference Gene Validation

| Algorithm | Methodology | Primary Output | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm | Pairwise comparison with stepwise exclusion | Stability measure (M); optimal gene number | Identifies best gene pairs; determines number needed | Cannot identify single best gene |

| NormFinder | Model-based variance estimation | Stability value (lower = more stable) | Accounts for sample subgroups; identifies single best gene | Less effective for identifying optimal pairs |

| BestKeeper | Correlation analysis of raw Cq values | Standard deviation, coefficient of variation | Direct analysis of raw data; identifies excessively variable genes | Requires high PCR efficiency for all genes |

| ΔCt Method | Direct comparison of ΔCt values | Standard deviation of pairwise variations | Simple implementation; no special software needed | Less sophisticated than other methods |

| RefFinder | Integration of multiple algorithms | Comprehensive ranking score | Combines strengths of all methods; consensus approach | Requires running all individual algorithms first |

Implementation of Validated HKGs

Following stability analysis, researchers should:

- Use Multiple Genes: Employ the top 2-3 most stable genes rather than a single reference [6] [10].

- Verify Experimentally: Confirm the performance of selected HKGs with target genes of known expression patterns [12].

- Contextualize Application: Remember that HKG stability is context-specific; revalidate for new experimental conditions [6].

The following workflow illustrates the consequences of proper versus improper normalization strategies:

Successful implementation of proper normalization strategies requires specific reagents and methodological components:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues | Critical for accurate expression profiling; prevents degradation artifacts [7] |

| Quality-controlled RNA | Template for cDNA synthesis | Verify A260/280 ratio (2.0-2.1) and integrity via electrophoresis [9] [7] |

| DNA Removal Treatment | Eliminates genomic DNA contamination | Prevents false amplification; use DNase treatment or specialized kits [12] [9] |

| Efficiency-validated Primers | Gene-specific amplification | Confirm efficiency (90-110%) and specificity (single melting curve peak) [9] [10] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA | Use consistent methodology across all samples; control for efficiency [12] [9] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Amplification reaction components | Include reference dye if needed; ensure lot-to-lot consistency [9] [7] |

| Statistical Algorithms | Stability assessment | Use multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt) [12] [10] |

| Reference Gene Panels | Candidate HKGs for validation | Select 6-10 genes from diverse functional classes [12] [11] |

The evidence against traditional housekeeping genes as default normalization standards is overwhelming and consistent across biological systems. The assumption that genes like GAPDH, ACTB, and 18S rRNA maintain constant expression across experimental conditions is not merely simplistic—it is scientifically unsupported and methodologically hazardous. The consequences of improper normalization range from technical inaccuracies to completely reversed biological interpretations, with serious implications for both basic research and clinical applications.

Moving forward, the research community must adopt evidence-based normalization practices as a fundamental component of rigorous qPCR experimental design. This includes:

- Abandoning the use of unvalidated traditional HKGs as default normalizers.

- Implementing systematic validation of reference genes for each specific experimental context.

- Employing multiple statistical algorithms to identify optimal reference gene combinations.

- Reporting HKG validation methodologies transparently in publications.

These practices align with the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines and represent an essential step toward enhancing reproducibility in gene expression research [9]. As the field continues to recognize the critical importance of proper normalization, the development of context-specific reference gene panels will further support accurate gene quantification across diverse research applications.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for gene expression analysis due to its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. However, the accuracy of this technique is critically dependent on proper normalization using stably expressed reference genes. This technical guide examines the profound consequences of improper normalization on biological interpretation, framed within the broader context of reference gene validation in qPCR research. Through analysis of experimental evidence across diverse biological systems—from human cancer studies to plant-pathogen interactions—we demonstrate how unstable reference genes systematically distort gene expression data, leading to false conclusions and irreproducible findings. This review provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodologies for reference gene validation, statistical frameworks for stability assessment, and practical solutions to ensure data integrity in gene expression studies.

The Critical Role of Normalization in qPCR

Fundamental Principles of qPCR Normalization

In RT-qPCR, the amount of amplified product is monitored during the course of the reaction by measuring fluorescence during the annealing phase of each amplification cycle [16]. The purpose of normalization is to remove sampling noise (such as RNA differences in concentration and quality) to estimate gene expression accurately [16]. Due to the quantitative nature of qPCR, an appropriate normalization method is critical to achieve reliable results [16]. Normalization compensates for variations in sample quantity, RNA quality, and efficiency of the reverse transcription and amplification processes [17].

The most common normalization approach employs endogenous controls, also known as reference genes or housekeeping genes [17]. These genes are assumed to be constitutively expressed at stable levels across various experimental conditions, cell types, and treatments [17]. Ideally, reference genes should be involved in basic cellular functions necessary for cell survival and maintenance, such as metabolism, structure, or cell cycle regulation [17].

The Compositional Nature of qPCR Data

A fundamental challenge in qPCR data interpretation stems from the compositional nature of the measurements [18]. In RT-qPCR experiments, the total amount of RNA input is fixed, meaning any change in the amount of a single RNA will necessarily translate into opposite changes in all other RNA levels [18]. This constraint makes interpreting changes in single gene expression without reference impossible, as the data are intrinsically relative rather than absolute [18].

This compositional property explains why normalization is not merely an optional step but an absolute necessity for meaningful interpretation of qPCR results. Without proper normalization, observed expression changes may reflect nothing more than the compositional constraint of fixed total RNA rather than genuine biological regulation.

Consequences of Improper Normalization

Systematic Distortion of Expression Profiles

Failure to use an appropriate reference gene for normalization may result in biased gene expression profiles, as well as low precision, so that only gross changes in expression level are declared statistically significant or patterns of expression are erroneously characterized [19]. The use of inappropriate reference genes that change their expression under experimental conditions can completely reverse the apparent direction of regulation of target genes, leading to fundamentally incorrect biological interpretations [20].

Even small variations in reference gene stability can significantly impact data interpretation. A difference of 0.5 Ct values between samples equates to a 1.41-fold change in expression levels, while a 2 Ct difference represents a four-fold change, which would render a gene entirely unsuitable as a control [17]. Such variations can easily create the illusion of biologically significant regulation where none exists, or mask genuine expression changes.

Tissue and Condition-Specific Instability

Reference gene stability varies dramatically across tissues and experimental conditions. In ageing mouse brain studies, common reference genes showed striking structure-dependent variability [21]. For example, Hprt showed no statistical differences in expression during ageing in the hippocampus but varied significantly in the cortex, striatum, and cerebellum [21]. Similarly, Polr2a was stable in the cortex, hippocampus, and striatum but showed significant variation in the cerebellum during ageing [21].

This tissue-specific variability means that a reference gene validated for one tissue cannot be assumed appropriate for another, even within the same organism. Similar findings have been reported across species, with grasshopper studies showing clear differences in reference gene stability between tissues and among closely related species [20].

Impact on Comparative Studies

In comparative gene expression studies across multiple species—particularly valuable for evolutionary insights—the assumption that reference genes stable in one species will remain stable in related species often proves false [20]. When this assumption fails, subsequent inferences about expression levels of genes of interest can be incorrect, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions about evolutionary patterns of gene regulation [20].

Table 1: Documented Consequences of Improper Normalization Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Impact of Improper Normalization | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer studies | Biased gene expression profiles, low precision, only gross changes detected | [19] |

| Ageing mouse brain | Structure-dependent variability leading to incorrect conclusions about age-related changes | [21] |

| Grasshopper species comparison | Erroneous conclusions about evolutionary patterns of gene regulation | [20] |

| Tomato-Ralstonia interactions | Misidentification of pathogen response mechanisms | [22] |

| Human cancer cell lines | Inaccurate quantification of gene expression patterns across cancer types | [23] |

Methodologies for Reference Gene Validation

Experimental Design for Validation

Proper validation of reference genes requires testing candidate genes under conditions representative of the planned study [17]. The experimental workflow should include:

- Selection of candidate genes based on literature review and database mining [23]

- RNA extraction from all samples across different test conditions using the same method [17]

- cDNA synthesis using the same amount of RNA and the same method across all samples [17]

- qPCR analysis of each candidate gene across all experimental conditions in at least triplicate reactions [17]

- Stability analysis using multiple algorithms to rank genes by expression stability [18]

The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines emphasize that normalization against a single reference gene is not recommended unless clear evidence of its invariant expression is provided for specific experimental conditions [16]. The optimal number and choice of reference genes should be experimentally determined [16].

Stability Analysis Algorithms

Four main computational methods have been developed to determine reference gene stability:

- Comparative ΔCt method: Calculates stability of each gene by obtaining the standard deviation of Cq differences within each sample for each pairwise comparison with other genes [16]

- NormFinder: Takes into account both intra-group and inter-group gene variation to evaluate stability [16]

- GeNorm: Determines the pairwise standard deviation of Cq values of all genes, then excludes the gene with lowest stability, repeating the process until only two genes remain [16]

- BestKeeper: Ranks genes according to the standard deviation of their Cq values [16]

Each algorithm has strengths and limitations. One comprehensive evaluation found NormFinder to be the most reliable method, while GeNorm results proved less dependable [16]. Recent approaches also include equivalence testing coupled with graph theory, which uses statistical procedures to control the error of selecting inappropriate genes [18].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive reference gene validation

Innovative Approaches: Gene Combinations and Database Mining

Recent research demonstrates that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform standard reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization [24]. This approach involves finding a fixed number of genes whose individual expressions balance each other across all experimental conditions of interest [24]. Such optimal combinations can be identified in silico using comprehensive RNA-Seq databases, then validated experimentally [24].

This method represents a paradigm shift from seeking individually stable genes to identifying combinations that provide collective stability. The geometric mean of multiple internal control genes provides more accurate normalization of qPCR data than single references [24]. For tomato studies, using the TomExpress RNA-Seq database enabled identification of optimal gene combinations that outperformed classical housekeeping genes [24].

Best Practices and Recommendations

Reference Gene Selection Guidelines

Based on extensive research across multiple biological systems, we recommend:

- Always validate reference genes for each specific experimental system; do not rely on literature alone [20]

- Use multiple reference genes (at least two) for normalization [16] [21]

- Employ multiple algorithms for stability analysis to achieve consensus [16] [18]

- Select references with similar expression levels to your target genes [17]

- Consider using innovative approaches such as gene combinations identified from RNA-Seq databases [24]

- Report validation data comprehensively following MIQE guidelines [16]

Table 2: Stability Analysis Algorithms: Comparative Features

| Algorithm | Methodological Approach | Strengths | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NormFinder | Accounts for intra-group and inter-group variation | Distinguishes between groups, less likely to select co-regulated genes | [16] | |

| GeNorm | Pairwise comparison with stepwise exclusion | Provides optimal number of genes, visual interpretation | May select co-regulated genes, overestimate number needed | [16] |

| BestKeeper | Based on standard deviation of Cq values | Simple approach, incorporates efficiency data | Does not directly compare multiple conditions | [16] |

| Comparative ΔCt | Analyzes pairwise variations between genes | Simple calculation, no specialized software needed | Limited analytical depth | [16] |

| Equivalence Testing | Network approach with statistical equivalence tests | Controls error rate, handles compositional nature | Computationally intensive, requires specialized software | [18] |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation with DNA removal | Qiagen RNeasy with on-column DNase treatment [19] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | cDNA synthesis with consistent efficiency | Comparison of Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit vs. High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit [23] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification with consistent efficiency | SYBR Green I systems for any amplicon [16] |

| Pre-designed Assays | Standardized amplification of candidate genes | TaqMan Endogenous Control Plates (32 human genes) [17] |

| Stability Analysis Software | Reference gene validation | GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, Comparative ΔCt method [16] |

| RNA-Seq Databases | In silico identification of stable genes | TomExpress (tomato), TCGA (cancer), RNA HPA cell line data [23] [24] |

The consequences of improper normalization in RT-qPCR experiments extend far beyond technical artifacts to fundamentally skewed biological interpretations. Unstable reference genes systematically distort expression data, leading to false conclusions about gene regulation, disease mechanisms, and treatment responses. This problem is particularly acute in comparative studies, disease research, and evolutionary investigations where biological variability intersects with technical limitations.

The solution requires a paradigm shift from assuming stability to rigorously demonstrating it through systematic validation. By employing multiple reference genes, using robust statistical methods for stability analysis, and embracing innovative approaches like balanced gene combinations identified from RNA-Seq databases, researchers can ensure the reliability and reproducibility of their gene expression studies. As qPCR continues to be a cornerstone technology in biological research and drug development, adherence to these rigorous normalization practices remains essential for generating biologically meaningful data and drawing accurate scientific conclusions.

Diagram 2: Consequences of proper versus improper reference gene validation

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) stands as one of the most precise techniques for gene expression analysis, yet its accuracy is critically dependent on the use of stable internal reference genes for normalization. This case study, framed within a broader thesis on the importance of robust normalization in qPCR research, demonstrates how improper reference gene selection can lead to significantly misleading conclusions. Through a detailed investigation in wheat (Triticum aestivum), we show that while the expression profile of the TaIPT1 gene remains consistent regardless of normalization method, the expression patterns of TaIPT5 are profoundly distorted when normalized with unstable controls. Our findings, derived from rigorous statistical evaluation and validation, underscore the non-negotiable necessity of validating reference genes for specific experimental conditions to ensure data integrity in genetic research and drug development.

The fidelity of gene expression data generated via Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, functional genomics, and pharmaceutical development. This technique's sensitivity and specificity make it indispensable for elucidating gene function, particularly for developmentally regulated genes and those involved in stress responses [3]. However, the accuracy of RT-qPCR is inherently tied to a critical preliminary step: the normalization of results using appropriate internal control, or reference, genes. These genes are presumed to maintain consistent expression across various tissues, developmental stages, and experimental treatments. The selection of unstable reference genes introduces systematic errors and generates quantitatively unreliable data, potentially derailing subsequent conclusions and applications [25].

Within the complex genome of allohexaploid wheat, where most genes exist as homoeologs from the A, B, and D genomes, the challenge of accurate normalization is intensified [3]. Traditional housekeeping genes, such as those encoding actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), are frequently employed out of convention. Yet, a growing body of evidence confirms that the expression of these genes can vary significantly across different biological contexts, rendering them unsuitable as universal controls [3] [25]. The advancement of statistical algorithms like geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and RefFinder now provides a robust framework for empirically identifying the most stable reference genes for a given experimental system [3].

This case study examines the expression of two target, developmentally expressed genes in wheat, TaIPT1 and TaIPT5, to illustrate the pivotal role of proper normalization. We demonstrate that while the expression pattern of one gene may be resilient to normalization errors, the other can exhibit dramatically different profiles, thereby influencing biological interpretation. This serves as a critical object lesson for researchers and drug development professionals on the imperative to validate reference genes, reinforcing a core tenet of our broader thesis: that rigorous methodological foundations are prerequisite for meaningful scientific discovery.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The study utilized two spring wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum L.), Kontesa and Ostka. Seeds were germinated and seedlings were grown under controlled environmental conditions: long-day photoperiod (16 hours light at 20°C / 8 hours dark at 18°C) with a light intensity of 350 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ [3].

A comprehensive set of samples was collected from both cultivars in three biological replicates. The collected tissues included:

- 5-day-old seedling roots

- 4-week-old plant leaves (the longest, well-developed leaves)

- 5–6 cm long inflorescences

- Developing spikes harvested at 0, 4, 7, and 14 days after pollination (DAP)

- Flag leaves collected simultaneously with inflorescences and spikes

All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until RNA extraction [3].

Candidate Reference Genes and Primer Validation

A set of ten candidate reference genes was selected based on previous expression studies in wheat. The genes, their annotations, and primer sequences are detailed in Table 1. The specificity of all primer pairs was confirmed via 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and analysis of RT-qPCR melting curves, ensuring amplification of a single target product [3].

Table 1: Candidate Reference Genes and Primer Sequences

| Symbol | Gene Annotation | Forward/Reverse Primers (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|

| Ref 2/Ta2291 | ADP-ribosylation factor | F: GCTCTCCAACAACATTGCCAACR: GCTTCTGCCTGTCACATACGC |

| Ta3006 | Wings apart-like protein 2 | F: CTGTGGGTCTGTCTAAGAATGCGR: CAAGTTGTTGTTTGGAAGGCAGC |

| Actin | Actin | F: CACACTGGTGTTATGGTAGGR: AGAAGGTGTGATGCCAAAT |

| Ta2776/RLI | 68 kDa protein HP68 | F: CGATTCAGAGCAGCGTATTGTTGR: AGTTGGTCGGGTCTCTTCTAAATG |

| CPD | Cyclic phosphodiesterase-like protein | F: CGACTTCTTCTACCAGTGCGTR: GGGTTGATCTCTGAAACCCGA |

| Cyclophilin | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | F: CAGGTCGGGTTGTCATGGR: TCCCCTTGTAGTGGAGAGGC |

| Ta14126 | Scaffold-associated regions DNA-binding protein | F: GAGTCTGCCCACCCATTCGTAAR: GACATGCCATAGGTTTCAGCGAC |

| eF1a | Translation elongation factor EF-1 alpha | F: CAGATTGGCAACGGCTACGR: CGGACAGCAAAACGACCAAG |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Information extracted from source material [3] |

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from frozen samples. After quality assessment via agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratios of 1.8-2.0), RNA samples were treated with DNase to eliminate genomic DNA contamination [3].

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a reverse transcription kit. The resulting cDNA samples were diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water before being used as templates in RT-qPCR reactions [3].

Stability Analysis of Reference Genes

The expression stability of the ten candidate reference genes was evaluated using four different algorithms:

- geNorm: Calculates a gene stability measure (M) based on the average pairwise variation between all genes. Lower M values indicate greater stability [3].

- NormFinder: Assesses both intra- and inter-group variation to determine expression stability [3].

- BestKeeper: Relies on the standard deviation and coefficient of variation of Ct values to determine the most stable genes [3].

- RefFinder: An integrative web-based tool that compiles results from geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper to generate a comprehensive stability ranking [3].

Absolute vs. Normalized Expression Analysis

To validate the impact of reference gene selection, the expression of two target genes, TaIPT1 and TaIPT5, was analyzed using both absolute quantification (without normalization) and relative quantification (normalized using stable and unstable reference genes). This direct comparison was designed to highlight discrepancies arising from normalization methods [3].

Results

Identification of Optimal Reference Genes

The stability of the ten candidate reference genes was assessed in two experiments. The results, synthesized by the RefFinder algorithm, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Stability Ranking of Reference Genes in Wheat Tissues

| Rank | Experiment 1 (Three Tissues) | Experiment 2 (Five Tissues) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Most Stable) | Ta2776 | Ta2776 |

| 2 | eF1a | Cyclophilin |

| 3 | Cyclophilin | Ta3006 |

| 4 | Ta3006 | Ref 2 |

| 5 | Ta14126 | Actin |

| 6 | Ref 2 | CPD |

| 7 | β-tubulin | - |

| 8 | CPD | - |

| 9 | GAPDH | - |

| 10 (Least Stable) | Actin | - |

In Experiment 1, Ta2776, eF1a, and Cyclophilin were consistently ranked as the most stable genes. In contrast, traditional housekeeping genes like β-tubulin, CPD, and GAPDH were among the least stable. Actin displayed the lowest stability in this experiment [3].

In Experiment 2, which involved a broader range of tissues, Ta2776, Cyclophilin, Ta3006, and Ref 2 demonstrated high stability, whereas CPD and Actin were again identified as less reliable [3].

Based on these comprehensive analyses, Ref 2 and Ta3006 were selected as the optimal reference genes for subsequent normalization across twelve diverse tissues/organs from both wheat cultivars. Their expression was confirmed to have no significant differences between cultivars, solidifying their suitability for broader gene expression studies in wheat [3].

Impact of Normalization on Target Gene Expression

The critical importance of reference gene selection was demonstrated by analyzing the expression of two target genes, TaIPT1 and TaIPT5, using different normalization strategies.

TaIPT1 Expression: This gene is specifically expressed in developing spikes. When its expression was analyzed, no significant differences were observed between the profiles generated by absolute quantification and those normalized using the stable reference genes Ref 2 or Ta3006. This indicates that for genes with highly tissue-specific expression, the normalization method may have a less pronounced effect on the overall interpretation [3].

TaIPT5 Expression: In stark contrast, TaIPT5 is expressed across all tested tissues. Its expression analysis revealed significant differences between absolute and normalized values in most tissues. Crucially, normalization using the stable genes Ref 2, Ta3006, or a combination of both produced consistent and reliable results. However, if an unstable gene had been used, the expression profile of TaIPT5 would have been dramatically and misleadingly altered [3].

These findings are summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3: Impact of Normalization on TaIPT1 and TaIPT5 Expression Profiles

| Target Gene | Expression Pattern | Absolute vs. Normalized Values | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaIPT1 | Specific (developing spikes) | No significant differences | Normalization choice less critical for tissue-specific genes |

| TaIPT5 | Ubiquitous (all tested tissues) | Significant differences in most tissues | Proper normalization is essential to avoid distorted expression profiles |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental process and the pivotal point where reference gene selection dictates analytical outcomes.

Discussion

The Non-Negotiable Need for Systematic Validation

This case study provides compelling evidence that the conventional practice of using traditional housekeeping genes like Actin or GAPDH for RT-qPCR normalization in wheat is fraught with risk. Our systematic validation, consistent with findings in other species such as Taihangia rupestris [25], clearly demonstrates that these genes are often among the least stable across different tissue types. Relying on them without prior validation, as was done in earlier studies on T. rupestris [25], can fundamentally compromise data integrity. The research community must, therefore, adopt the routine practice of validating reference genes for each specific experimental system—a standard that is critical for both basic research and the precise gene expression analyses underpinning drug development pipelines.

Consequences for Functional Gene Interpretation

The divergent outcomes observed for TaIPT1 and TaIPT5 expression serve as a critical lesson. The fact that TaIPT5 expression was profoundly affected by the normalization method highlights a perilous scenario: researchers could arrive at entirely erroneous conclusions about a gene's regulation and function. For instance, a peak in expression normalized with an unstable gene might be an artifact, while a true, biologically significant fluctuation could be masked. This is particularly relevant for gene families and polyploid species like wheat, where subtle, spatiotemporal expression patterns of homoeologs are key to understanding their distinct functions [3]. Using unstable references would obliterate the ability to discern these critical patterns, potentially misdirecting breeding or biotechnological applications.

A Robust Framework for Future Research

The integration of multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and RefFinder) provides a robust, consensus-based approach to reference gene selection, mitigating the biases inherent in any single method [3] [25]. The identification of Ref 2 and Ta3006 as stable genes across diverse wheat tissues and two cultivars offers a validated resource for the wheat research community. Their use will enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of future gene expression studies. Furthermore, the demonstrated reliability of a single reference gene (Ref 2) in this and previous studies [3] simplifies experimental design, though the option of using two genes (Ref 2 and Ta3006) remains for applications demanding the highest possible precision.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for RT-qPCR Normalization

| Item | Function / Role | Example from Study |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Reference Genes | Internal controls for normalizing target gene expression data; their stable expression is validated for the specific experimental condition. | Ref 2 (ADP-ribosylation factor), Ta3006 (Wings apart-like protein 2) [3] |

| Validated Primer Pairs | Oligonucleotides specifically designed to amplify the reference or target gene with high efficiency and specificity, confirmed by melt curve analysis. | Primers for Ref 2 and Ta3006 (see Table 1) [3] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For the isolation of high-quality, intact total RNA from tissue samples. | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) [3] |

| DNAse Treatment Reagent | To remove contaminating genomic DNA from RNA samples prior to cDNA synthesis, preventing false positives. | gDNA Eraser (Takara) [3] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | For synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. | Perfect Real Time RT reagent Kit (Takara) [3] |

| Statistical Algorithms | Software tools to objectively evaluate and rank the expression stability of candidate reference genes. | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder [3] |

This investigation unequivocally demonstrates that proper normalization is not a mere technical formality but a fundamental determinant of data veracity in RT-qPCR analysis. The significant differences in TaIPT5 expression revealed only through the use of validated reference genes underscore a central tenet of our broader thesis: the selection of internal controls must be driven by empirical, systematic validation within the specific experimental context, not by convention alone. The adoption of this rigorous approach is imperative for generating reliable, reproducible, and biologically meaningful gene expression data, thereby ensuring the integrity of scientific conclusions in both academic research and applied drug development.

From Theory to Bench: A Methodological Guide to Selecting and Applying Reference Genes

The reliability of any quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) experiment hinges on effective normalization, a process critical for controlling technical variations that occur during sample preparation, RNA extraction, and amplification. Reference genes, often called housekeeping genes, serve as internal controls to correct for these non-biological variations, enabling accurate interpretation of target gene expression. The fundamental assumption is that these genes maintain constant expression across all test conditions. However, a growing body of evidence definitively shows that no universal reference genes exist; even classic housekeeping genes can exhibit significant expression variability depending on the biological context [26]. The use of an inappropriate reference gene can introduce substantial biases, leading to false conclusions, a concern particularly critical in pharmaceutical development and clinical research where decisions have significant ramifications [27] [28]. This guide provides a structured framework for building a robust candidate list of reference genes, a foundational step for generating credible gene expression data.

The Evidence: Why Validation is Non-Negotiable

The assumption that commonly used reference genes are stable across all experimental conditions is perhaps the most prevalent pitfall in RT-qPCR studies. Multiple systematic investigations across diverse organisms and tissues have demonstrated that expression stability is highly context-dependent.

Case Studies in Model Organisms

In wheat (Triticum aestivum), a 2025 study systematically evaluated ten candidate reference genes across different tissues and developmental stages. The results revealed a clear hierarchy of stability, with some genes performing well while others were unsuitable. The research demonstrated that normalization of the target gene TaIPT5 with unstable references produced significantly different results compared to normalization with validated genes, directly impacting biological interpretation [29].

In mouse models, a 2021 study focusing on the choroid plexus across developmental stages and sensory deprivation experiments found that the most stable genes were condition-specific. Rer1 and Rpl13a were optimal for developmental studies, whereas Hprt1 and Rpl27 were superior for sensory deprivation paradigms. Normalizing the choroid plexus marker Ttr with different reference genes produced markedly different expression profiles, underscoring the profound effect of this choice [30]. Similarly, a 2018 study on developing mouse gonads found that stability of 15 candidate genes fluctuated greatly depending on the developmental period and gender, recommending Ppia and Polr2a for wide developmental periods [31].

The table below synthesizes findings from recent studies, highlighting how the "best" reference genes are dictated by the specific experimental system.

Table 1: Stable and Unstable Reference Genes Across Different Experimental Systems

| Organism | Experimental Context | Most Stable Reference Genes | Less Stable Reference Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Developing organs [29] | Ta2776, eF1a, Cyclophilin, Ref 2, Ta3006 | β-tubulin, CPD, GAPDH |

| Mouse | Choroid Plexus, Development [30] | Rer1, Rpl13a | Sdha, Actb |

| Mouse | Choroid Plexus, Sensory Deprivation [30] | Hprt1, Rpl27 | Sdha, Actb |

| Mouse | Developing Gonads [31] | Ppia, Polr2a | Actb, Gapdh (varied with stage/sex) |

| Human | Peripheral Blood, X-ray Irradiation [32] | UBC, HPRT, GAPDH (stability was time-dependent) | ACTB (varied with culture time) |

The Problem with "Classic" Housekeeping Genes

Systematic reviews corroborate these findings. A 2024 review of reference gene selection in rodents concluded that classic genes like Actb (β-actin) and Gapdh, while frequently used, often demonstrate greater variability than less traditional candidates, reinforcing the necessity for experimental validation [33]. The underlying reason is biological: many classic housekeeping genes are involved in basic metabolic pathways (e.g., GAPDH in glycolysis) that can be profoundly influenced by the cellular state, disease, or external stimuli [27] [26]. Their high transcript abundance can also create a technical discrepancy when normalizing less abundant target genes [26].

Methodologies for Reference Gene Evaluation

A robust validation workflow involves selecting candidates, running an RT-qPCR experiment, and analyzing the resulting data with specialized algorithms to rank genes by their expression stability.

Experimental Workflow for Validation

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a reference gene validation experiment:

1. Select Candidate Genes: A panel of 8 to 15 candidate genes is recommended to avoid co-regulation artifacts. Select genes from diverse functional pathways (e.g., cytoskeleton, transcription, metabolism) to minimize the chance of coordinated expression changes [31] [30]. The list should include both traditional housekeeping genes and genes previously reported as stable in similar models.

2. RNA Extraction & QC: Extract high-quality, DNA-free total RNA. Quality and integrity should be verified using methods like the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), with a RIN ≥7.3 often considered a benchmark for reliable results [32].

3. cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe RNA into cDNA using a robust kit. Consistent input RNA amounts and the use of a mix of random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers are common practices to ensure comprehensive reverse transcription [29] [31].

4. RT-qPCR Run: Perform qPCR in technical replicates for all candidate genes across all biological samples. It is critical to determine primer efficiency (typically 90-110% is acceptable) using a standard curve from a serial dilution [32]. A single, specific amplification product should be confirmed via melt curve analysis [29] [30].

Stability Analysis Algorithms and Tools

After data collection, Cq (quantification cycle) values are analyzed using dedicated algorithms. Using multiple tools provides a more robust assessment than relying on a single method.

Table 2: Key Algorithms for Reference Gene Stability Analysis

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Output | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm [27] [30] | Pawise comparison of expression ratios to calculate a stability measure (M). | Ranks genes by M-value; lower M = more stable. Also determines optimal number of genes. | Cannot identify the single best gene; the final two are ranked equally. |

| NormFinder [30] | Models variation within and between sample groups to find stable genes. | Provides a stability value considering group variations. | Better suited for experiments with defined groups (e.g., treated vs. control). |

| BestKeeper [31] | Uses raw Cq values to calculate standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variance. | Ranks genes based on SD; lower SD = more stable. | Simple and direct, but does not account for co-regulation. |

| RefFinder [29] [32] | A comprehensive tool that integrates results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCq method. | Provides an overall final ranking based on geometric mean. | Offers a consensus view, mitigating biases of individual algorithms. |

Building Your Candidate List

A well-constructed candidate list is the first and most critical step toward successful validation. The following table provides a starting point, compiled from recent literature, which should be tailored to your specific research organism and context.

Table 3: Candidate Reference Genes for Different Organisms

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Reported Stability (Organism/Context) | Functional Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBC | Ubiquitin C | Human peripheral blood (2/12hr post-irradiation) [32] | Protein degradation |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyl-transferase | Human peripheral blood (2/12hr) [32]; Mouse sensory deprivation [30] | Purine synthesis |

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A | Developing mouse gonads [31] | Protein folding |

| POLR2A | RNA Polymerase II Subunit A | Developing mouse gonads [31] | Transcription |

| RPL13A | Ribosomal Protein L13a | Mouse choroid plexus development [30] | Translation |

| RPL27 | Ribosomal Protein L27 | Mouse choroid plexus development & sensory deprivation [30] | Translation |

| TBP | TATA-Box Binding Protein | Mouse choroid plexus [30]; Wound healing (mouse) [27] | Transcription |

| Ref 2 | ADP-ribosylation Factor | Developing wheat organs [29] | Vesicle trafficking |

| YWHAZ | Tyrosine 3-Monooxygenase | Mouse gonads [31]; Commonly assessed [27] | Signal transduction |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase | Human peripheral blood (2/24hr) [32] Note: Often unstable [29] [33] | Glycolysis |

| ACTB | Beta-Actin | Human peripheral blood (varied) [32] Note: Often unstable [33] [30] | Cytoskeleton |

| 18S rRNA | 18S Ribosomal RNA | Human peripheral blood (12/24hr) [32] | Ribosomal RNA |

Key Considerations for List Building

- Diversity is Key: Select candidates from various functional classes to reduce the risk of co-regulation. For example, do not choose only ribosomal proteins.

- Abundance Matching: Where possible, include genes with expression levels (Cq values) similar to your target genes. Normalizing a low-abundance target to a very high-abundance reference can introduce noise [26].

- Leverage Existing Data: Use public databases like Genevestigator, which allows identification of stable genes from microarray datasets for specific biological contexts, to discover novel, potentially more stable candidates [26].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Purify high-quality, genomic DNA-free total RNA. Kits with on-column DNase treatment are preferred. | RNeasy kits (QIagen) were used in mouse gonad [31] and choroid plexus [30] studies. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Synthesize first-strand cDNA from RNA templates. Kits with a mix of random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers ensure comprehensive coverage. | PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara) [31]; RevertAid Kit (Thermo Scientific) [29]. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mix containing SYBR Green dye, Taq polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient amplification. | HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Mix Plus (Solis BioDyne) [29]; SYBR Premix EX TaqII (Takara Bio) [31]. |

| Probe-Based qPCR Master Mix | A master mix optimized for hydrolysis probe (TaqMan) assays, offering higher specificity. | PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (IDT) [34]. |

| Pre-Designed qPCR Assays | Experimentally validated primer and probe sets for specific genes, guaranteeing performance. | RT2 qPCR Primer Assays (QIagen) [35]; PrimeTime qPCR Assays (IDT) [34]. |

| Stability Analysis Software | Tools and algorithms for calculating reference gene stability from Cq value data. | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comprehensive webtool RefFinder [29] [32]. |

The process of building and validating a candidate list for reference genes is not a mere technical formality but a fundamental component of rigorous RT-qPCR experimental design. As evidenced by numerous studies, reliance on unvalidated "classic" genes poses a significant risk to data integrity. By adopting a systematic approach—selecting a diverse panel of candidates, executing a careful validation experiment, and analyzing data with multiple algorithms—researchers can confidently identify the most stable normalizers for their specific biological context. This diligence is paramount in drug development and clinical research, where the accuracy of gene expression data can directly impact scientific conclusions and subsequent development decisions.

Accurate gene expression analysis using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) is fundamental to molecular biology, from basic research to drug development. A critical prerequisite for obtaining reliable results is effective data normalization to account for technical variations introduced during sample processing. The use of stable reference genes, also known as housekeeping genes (HKGs), is the most widely endorsed normalization strategy [36] [37]. However, a fundamental challenge is that no single biological gene is stably expressed across all cell types or experimental conditions [37]. The expression of commonly used HKGs can vary significantly depending on the organism, tissue, developmental stage, or specific experimental treatments such as abiotic stress, viral infection, or hypoxia [36] [38] [14].

To address this, several statistical algorithms have been developed to systematically identify the most stable reference genes for a given experimental system. The four most prominent are geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method, often integrated via the RefFinder platform [29] [39] [14]. These tools evaluate candidate reference genes based on their expression stability, enabling researchers to make an evidence-based selection. Employing these algorithms is now considered a best practice, as it minimizes normalization errors that could otherwise lead to misleading biological conclusions [40] [38]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core algorithms, their methodologies, and their practical application in ensuring the rigor and reproducibility of qPCR-based research.

Core Algorithm Principles and Methodologies

Each algorithm uses a distinct statistical approach to rank candidate genes based on their expression stability, measured through Cycle threshold (Ct) values.

geNorm

- Principle: geNorm operates on the principle that the expression ratio of two ideal reference genes should be constant across all samples. It uses a pairwise comparison model to determine the stability of all candidate genes [29] [39].

- Methodology: The algorithm calculates a stability measure (M) for each gene as the average pairwise variation of that gene with all other tested candidates. A lower M value indicates greater stability. Genes are progressively eliminated, starting with the highest M value. A key output of geNorm is the determination of the optimal number of reference genes required for robust normalization. This is achieved by calculating a pairwise variation (V) between sequential normalization factors (e.g., V2/3, V3/4). A commonly used threshold is V < 0.15, below which the inclusion of an additional reference gene is deemed unnecessary [29] [39].

NormFinder

- Principle: NormFinder is a model-based approach that evaluates expression stability not only within sample groups (intra-group variation) but also between different experimental conditions (inter-group variation) [29] [39] [14].

- Methodology: The algorithm computes a stability value for each gene, which is a direct measure of its combined intra- and inter-group variation. Like geNorm, a lower stability value indicates more stable expression. A significant strength of NormFinder is its ability to identify the best single reference gene and the best pair of genes, even if they are co-regulated, by considering variations across defined sample subgroups [29] [39].

BestKeeper

- Principle: BestKeeper assesses stability by analyzing the raw Ct values themselves, using descriptive statistics such as the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) [29] [38].

- Methodology: The tool calculates the geometric mean of Ct values for each candidate gene and then determines the SD and CV. A gene is considered stable if its SD is less than 1. BestKeeper can also create an index from the best-performing genes and evaluate the correlation of each candidate to that index. It provides a straightforward ranking based on the variability of raw Ct values [29] [38].

Comparative ΔCt Method

- Principle: This method evaluates stability by comparing the relative expression of pairs of genes within each sample [39] [14].

- Methodology: For each sample, the difference in Ct values (ΔCt) between every two candidate genes is calculated. The standard deviation of the ΔCt values is then computed for each gene pair. Genes with a lower average standard deviation across all pairings are considered more stable [39] [14].

RefFinder

- Principle: RefFinder is a web-based tool that integrates the four algorithms above to provide a comprehensive and robust ranking [39] [14].

- Methodology: RefFinder runs the analyses for geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method. It then assigns an appropriate weight to each gene based on its ranking from each algorithm and calculates the geometric mean of these weights to generate an overall final ranking. This integrative approach helps mitigate the limitations of any single algorithm [39] [14].

Table 1: Summary of Key Statistical Algorithms for Reference Gene Validation

| Algorithm | Underlying Principle | Key Output Metric | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm | Pairwise comparison of expression ratios | Stability Measure (M); Pairwise Variation (V) | Determines the optimal number of reference genes. |

| NormFinder | Model-based variance estimation (intra- & inter-group) | Stability Value | Accounts for variation between experimental groups; identifies best pair. |

| BestKeeper | Descriptive statistics of raw Ct values | Standard Deviation (SD) & Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Simple, direct analysis based on Ct value variability. |

| ΔCt Method | Pairwise comparison of ΔCt values | Average Standard Deviation of ΔCt | Simple and direct calculation without complex models. |

| RefFinder | Integrated ranking from the four methods | Geometric Mean of Ranks | Provides a comprehensive, consensus ranking. |

Experimental Protocol for Reference Gene Validation

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for identifying and validating stable reference genes, as applied in recent studies [36] [29] [14].

Experimental Design and Sample Collection

- Collect samples encompassing the entire range of conditions for the planned study (e.g., different tissues, developmental stages, drug treatments, stress conditions).

- Include a sufficient number of biological replicates (typically n ≥ 3) to ensure statistical power.

Selection of Candidate Reference Genes

- Select a panel of candidate genes (typically 8-14) based on literature reviews and genomic databases. Common candidates include genes involved in cytoskeletal structure (ACTB, TUB), glycolysis (GAPDH), protein synthesis (RPL13A, RPS23), and ubiquitination (UBQ10) [36] [38] [14].

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

- Extract total RNA using commercial kits (e.g., RNeasy Plant Mini Kit, Qiagen; TRIzol Reagent) and treat with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination [36] [29].

- Assess RNA quality and quantity via spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) and/or agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Synthesize cDNA from high-quality RNA using reverse transcription kits (e.g., RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Maxima H Minus Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit) [36] [29].

qRT-PCR Amplification

- Perform qPCR reactions in technical triplicates using EvaGreen or SYBR Green chemistry on a real-time PCR detection system (e.g., CFX384 Touch, Bio-Rad; LightCycler 480 II, Roche) [29] [14].

- Ensure primer specificity, confirmed by a single peak in the melting curve and a single band of the expected size on an agarose gel.

- Calculate PCR amplification efficiency for each primer pair using a standard curve from a serial cDNA dilution. Efficiency between 90% and 110% with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.990 is generally acceptable [29] [14].

Stability Analysis and Validation