Beyond the Noise: Advanced Strategies for Validating Low-Expression Genes in Biomedical Research

Validating genes with low expression levels is a critical yet challenging frontier in genomics, single-cell transcriptomics, and drug discovery.

Beyond the Noise: Advanced Strategies for Validating Low-Expression Genes in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Validating genes with low expression levels is a critical yet challenging frontier in genomics, single-cell transcriptomics, and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental causes of low-expression signals—from technical dropouts to biological regulation. It reviews state-of-the-art computational methods and experimental optimizations designed to enhance detection sensitivity and accuracy. Furthermore, the article offers a rigorous framework for troubleshooting analytical pipelines and benchmarking validation performance against established ground truths, ultimately empowering scientists to confidently extract meaningful biological insights from subtle transcriptional signals.

Understanding the Low-Expression Challenge: From Technical Noise to Biological Signal

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the fundamental types of zeros in single-cell RNA-seq data? In scRNA-seq data, zeros are categorized into two distinct types:

- Biological Zeros: These represent genes that are genuinely not expressed in the cell at the time of sequencing. They are true negatives and carry meaningful biological information about the cell's state or type.

- Technical Zeros (Dropouts): These are artifacts where a gene is expressed in a cell but fails to be detected due to technical limitations like low mRNA capture efficiency, insufficient sequencing depth, or amplification bias [1] [2].

Why is accurately distinguishing between these zeros so critical for analysis? Misclassification between these zero types leads to significant misinterpretation:

- False Positives: Imputing a true biological zero (e.g., a gene silent in a specific cell type) can create false signals, blurring distinct cell identities [1] [3].

- Loss of Biological Signals: Treating all zeros as technical artifacts and filtering them out removes valuable information. Biological zeros are essential for defining cell types, and dropout patterns can themselves be used for clustering [4] [5] [3].

- Downstream Analysis Bias: Incorrect imputation confounds differential expression analysis, trajectory inference, and the identification of rare cell populations [6] [3].

My data has over 90% zeros. Is this normal, and does it mean my experiment failed? Extremely high sparsity (e.g., 90-97% zeros) is common in many scRNA-seq datasets, especially those from droplet-based protocols like 10X Genomics [4] [6]. This does not necessarily indicate a failed experiment. The key is to determine whether the zeros are structured (informative for cell identity) or random noise. Analytical methods are designed to handle this inherent sparsity [4] [5].

Can the pattern of dropouts itself be biologically informative? Yes. Instead of viewing dropouts solely as noise to be corrected, an alternative approach is to "embrace" them as a useful signal. Genes within the same pathway or specific to a cell type can exhibit similar dropout patterns across cells. This binarized (zero vs. non-zero) pattern can be as effective as quantitative expression for identifying cell types when analyzed with appropriate algorithms like co-occurrence clustering [4].

How does UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) barcoding change the dropout paradigm? UMI barcoding, used in protocols like 10X Genomics, helps mitigate amplification bias. Evidence suggests that in UMI data, particularly within a homogeneous cell population, the observed zeros often align with the expected sampling noise of a Poisson distribution, rather than requiring a model for "excessive" zero-inflation. This implies that for defined cell types, dropouts may be less of an issue than previously thought, and the major driver of zeros in mixed populations is often cell-type heterogeneity [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Clustering Results are Unstable or Do Not Align with Known Biology

Potential Cause: High dropout rates can break the assumption that biologically similar cells are always close neighbors in expression space. This disrupts the foundation of graph-based clustering algorithms, leading to unstable clusters and an inability to reliably identify fine-grained subpopulations [6].

Solutions:

- Leverage Dropout Patterns: Use computational methods that utilize the binary dropout pattern for initial clustering, which can be more robust to technical noise. Tools that employ iterative co-occurrence clustering of binarized data have been shown to effectively identify major cell types [4].

- Re-evaluate Pre-processing: Consider whether normalization or imputation applied to the entire dataset before resolving cell-type heterogeneity is introducing noise. One framework, HIPPO, suggests that clustering should be the foremost step, not following imputation [5].

- Benchmark Cluster Stability: Use simulated datasets with known ground truth to assess how stable your clustering pipeline is under increasing levels of dropout noise. This helps in choosing a robust method for your specific data [6].

Problem: Imputation is Blurring Cell-Type Boundaries

Potential Cause: Many imputation methods treat all zeros as missing data and can impute values for genes that are genuine biological zeros, effectively adding false expression signals to cell types where the gene should be silent [1] [3].

Solutions:

- Use Zero-Preserving Imputation: Employ methods specifically designed to preserve biological zeros. For example, ALRA (Adaptively thresholded Low-Rank Approximation) uses a low-rank approximation followed by a gene-specific thresholding step that sets values likely to be biological zeros back to zero [1].

- Incorporate External Information: Use network-based imputation methods (e.g., those in the ADImpute package) that leverage pre-existing gene-gene relationship networks (e.g., transcriptional regulatory networks) from independent, more complete datasets. This can provide a more reliable basis for imputing only technical zeros [2].

- Gene-Specific Imputation Strategy: Recognize that no single imputation method works best for all genes. Some tools allow for an adaptive approach where the best imputation method (including no imputation) is selected for each gene based on its characteristics [2].

Problem: Difficulty Validating Low-Expression Genes with RT-qPCR

Potential Cause: A failure to select stable reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization across your specific tissues or experimental conditions can lead to inaccurate relative quantification, making it impossible to reliably confirm the expression levels of your target low-expression genes [7] [8].

Solutions:

- Systematic Reference Gene Validation: Do not rely on "traditional" reference genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) without validation. Use algorithms like GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and Delta-Ct, integrated by tools like RefFinder, to identify the most stably expressed reference genes in your specific experimental system [7].

- Utilize RNA-seq Data: Your initial RNA-seq or scRNA-seq dataset can be a resource. Analyze it to identify new candidate reference genes that show highly stable expression across your samples [8].

- Experimental Design: Always validate multiple reference genes and use a geometric mean of at least two of the most stable ones for normalization in your RT-qPCR experiments [7].

The following table summarizes several computational approaches for handling dropouts, each with a different philosophy.

Table: Comparison of Computational Approaches for Handling Zeros in scRNA-seq Data

| Method / Approach | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Potential Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-occurrence Clustering [4] | Uses binarized data (0/1); clusters cells based on genes that "drop out" together. | Treats dropouts as signal; no imputation; effective for cell type identification. | Discards quantitative expression information. |

| ALRA [1] | Low-rank matrix approximation with adaptive thresholding to preserve biological zeros. | Explicitly designed to keep biological zeros at zero after imputation. | Requires a low-rank assumption for the true expression matrix. |

| Network-Based (ADImpute) [2] | Uses external gene-gene networks (e.g., regulatory networks) to guide imputation. | Leverages independent biological knowledge; performs well for lowly expressed regulators. | Quality depends on the relevance and accuracy of the external network. |

| HIPPO [5] | Uses zero proportions for feature selection and performs iterative clustering before any normalization. | Resolves cell-type heterogeneity first, avoiding noise introduction from premature processing. | Represents a significant shift from standard Seurat/Scanpy pipelines. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Zero-Preserving Imputation with ALRA

This protocol is adapted from the ALRA methodology, which is designed to impute technical dropouts while preserving biological zeros [1].

Objective: To recover missing expression values for genes affected by technical dropouts in a scRNA-seq count matrix, without imputing values for genes that are genuinely not expressed (biological zeros).

Materials and Input Data:

- A filtered scRNA-seq count matrix: Cells as columns, genes as rows. The matrix should be filtered for low-quality cells and genes but not normalized or log-transformed.

- Computing Environment: R or Python with the ALRA package/algorithm implemented.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Begin with the raw UMI count matrix. Ensure that the matrix is non-negative.

- Low-Rank Approximation:

- Perform a Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the observed count matrix or a normalized version of it.

- Determine the optimal rank k for the approximation. ALRA uses a method based on the singular values to automatically select k, which captures the significant biological signal.

- Compute the rank-k approximation of the original matrix. This step denoises the data but results in a matrix with (typically) no zero values.

- Adaptive Thresholding (Key Step for Preserving Zeros):

- For each gene (row) in the low-rank matrix, examine the distribution of imputed values across all cells.

- Theoretically, the values corresponding to true biological zeros are symmetrically distributed around zero.

- Identify the most negative value for the gene. Set all values smaller than the absolute value of this most negative value to zero. This step adaptively determines a gene-specific threshold to restore biological zeros.

- Output: The final output is an imputed, zero-preserved matrix ready for downstream analysis like clustering or differential expression.

Visual Workflows

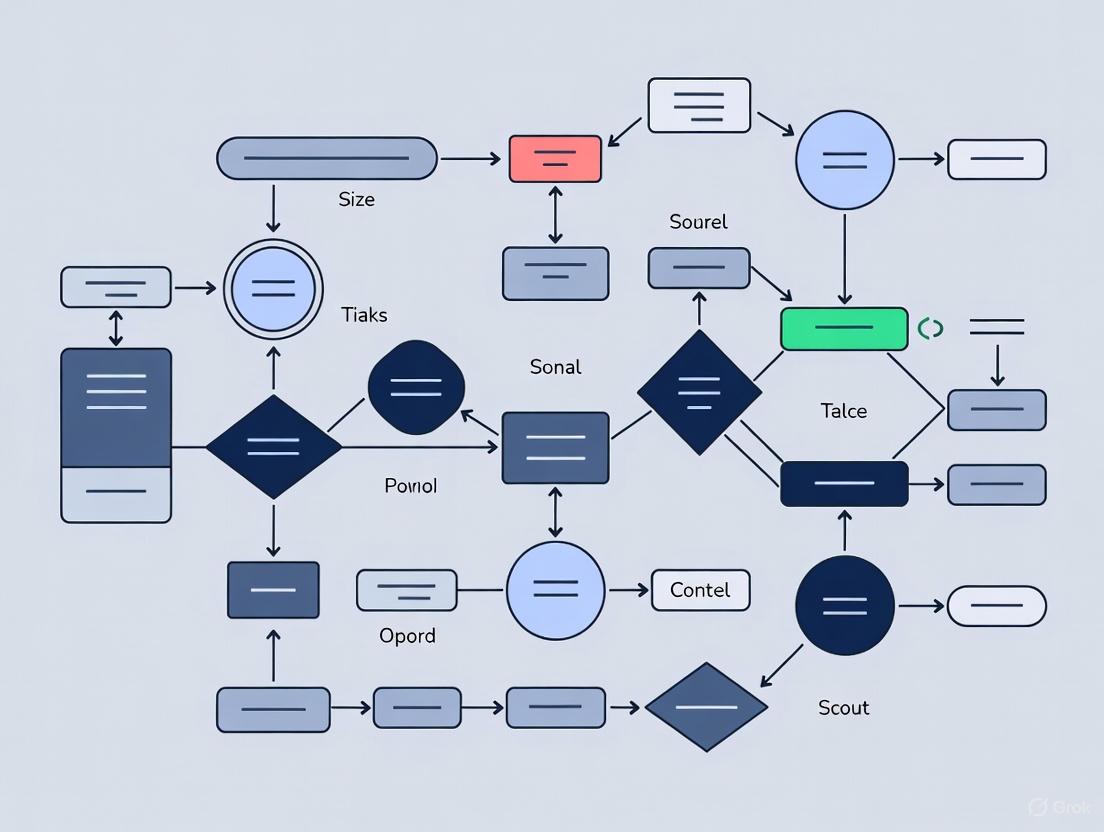

Diagram: Decision Framework for scRNA-seq Zero Analysis

Diagram: RT-qPCR Validation Workflow for Low-Expression Genes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Resources for scRNA-seq and Validation Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| UMI scRNA-seq Kit | Provides unique molecular identifiers to tag mRNA molecules, reducing amplification bias and allowing for absolute transcript counting. | 10X Genomics Chromium, Drop-seq, inDrops [4] [5]. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Essential stable genes for accurate normalization in RT-qPCR validation experiments. | Must be validated for your specific tissue/condition. Examples from literature: STAU1 (decidualization), IbACT/IbARF (sweet potato tissues) [7] [8]. |

| Stable Cell Type Markers | Well-characterized genes specific to a cell type; used as positive controls and for validating cluster identities. | e.g., PAX5 for B cells, NCAM1 (CD56) for NK cells [1]. |

| Transcriptional Regulatory Network Database | External resource of gene-gene relationships for network-based imputation and functional analysis. | Used by methods like ADImpute to improve dropout prediction [2]. |

| RefFinder Algorithm | Integrates multiple algorithms (GeNorm, NormFinder, etc.) to provide a comprehensive ranking of candidate reference gene stability [7]. | Critical for robust RT-qPCR experimental design. |

The Impact of Excessive Zeros in Single-Cell RNA-seq Data on Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main causes of excessive zeros in single-cell RNA-seq data?

Excessive zeros, often referred to as "dropout events," arise from two primary sources:

| Zero Type | Cause | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Zeros | True absence of a gene's transcripts in a cell [9] | Represents genuine biological signal; should be preserved |

| Technical Zeros | Technical limitations during library preparation and sequencing [9] [1] | Artificial missing data; should be addressed computationally |

Technical zeros occur due to:

- Low capture efficiency: Only a small fraction of transcripts are captured during library preparation [10]

- Limited sequencing depth: Insufficient reads to detect lowly expressed genes [9]

- Amplification bias: Stochastic variation in amplification efficiency [11]

- Cell quality issues: Stressed, broken, or dead cells contributing abnormal expression patterns [12]

How do excessive zeros impact downstream validation studies?

Excessive zeros significantly compromise key validation studies:

| Analysis Type | Impact of Excessive Zeros |

|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Reduces power to detect truly differentially expressed genes; one study showed much lower gene detection after downsampling [10] |

| Cell Type Identification | Obscures true cell identities and states; weakens evidence for cell subtypes [10] |

| Marker Gene Validation | Leads to false positives/negatives in candidate selection; not all top-ranked markers are functionally relevant [13] |

| Gene Correlation Studies | Dampens or obscures true biological correlations between genes [10] |

In one case study, functional validation revealed that only four of six high-ranking tip endothelial cell markers actually behaved as predicted, demonstrating how zeros can lead to inaccurate candidate prioritization [13].

What computational strategies effectively address excessive zeros?

Several computational approaches have been developed with different strengths:

| Method | Approach | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| SAVER | Borrows information across genes and cells using Poisson Lasso regression [10] | Recovering gene expression distributions and correlations |

| ALRA | Uses low-rank matrix approximation with adaptive thresholding [1] | Preserving biological zeros while imputing technical zeros |

| MAGIC | Uses data diffusion to impute missing values [10] [1] | General data denoising (but may introduce spurious correlations) |

| scImpute | Identifies likely technical zeros and imputes them [1] | When preserving biological zeros is critical |

ALRA preserves >85% of true biological zeros while completing technical zeros, outperforming other methods that either preserve fewer zeros or impute too aggressively [1].

How can I determine if zeros in my data are biological or technical?

Use these experimental and computational approaches:

Experimental Designs:

- UMI protocols: Reduce amplification bias but still have substantial dropout rates [9] [14]

- Spike-in controls: Help quantify technical noise and capture efficiency [12]

- CITE-seq: Simultaneous protein measurement helps validate transcriptomic findings [1]

- RNA FISH validation: Provides ground truth for expression patterns [10]

Computational Quality Control:

- Cell-level QC: Remove cells with high mitochondrial gene expression or low unique gene counts [12]

- Feature selection: Focus on genes with consistent expression across cell populations

- Cross-validation: Compare results across multiple imputation methods

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent validation results between scRNA-seq and functional assays

Symptoms:

- Top marker genes from scRNA-seq fail to validate in functional experiments

- Poor correlation between sequencing data and protein expression measurements

- Inability to reproduce clustering results in validation datasets

Solutions:

Apply appropriate imputation methods:

Implement rigorous quality control:

Quality Control and Validation Workflow

Utilize complementary validation approaches:

Problem: Poor detection of rare cell populations

Symptoms:

- Inconsistent identification of rare cell types across analyses

- Putative rare population markers fail to validate

- High variability in rare population abundance estimates

Solutions:

Optimize experimental design:

Apply specialized computational methods:

- Use methods that preserve weak biological signals [10]

- Implement supervised clustering with known markers

- Employ ensemble approaches combining multiple clustering algorithms

Problem: Unreliable differential expression results

Symptoms:

- High false discovery rates in DE analysis

- Poor replication of DE results in technical replicates

- Inconsistent fold-change estimates across methods

Solutions:

Address zeros in statistical testing:

Benchmark performance with down-sampling:

- Evaluate how DE results change with sequencing depth [10]

- Use cross-validation to assess stability of findings

- Compare multiple DE methods to identify robust signals

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Experimental Platform | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | Optimize cell viability (>90%) and input concentration |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) | Molecular Barcode | Corrects for amplification bias [10] | Essential for accurate transcript quantification |

| SAVER | Computational Tool | Recovers expression values using gene correlations [10] | Preserves biological variability; provides uncertainty estimates |

| ALRA | Computational Tool | Zero-preserving imputation via low-rank approximation [1] | Automatically determines optimal rank; preserves biological zeros |

| Seurat | Computational Toolkit | End-to-end scRNA-seq analysis [10] | Industry standard; integrates with most imputation methods |

| ERCC Spike-ins | Quality Control | Quantifies technical noise and sensitivity [12] | Add at consistent concentration across samples |

| Cell Hashing | Experimental Method | Identifies multiplets and improves demultiplexing [11] | Critical for samples with complex experimental designs |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Marker Genes in the Presence of Excessive Zeros

Step-by-Step Workflow for Robust Validation

Comprehensive Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodology

Pre-experimental Design Phase:

- Power calculation: Ensure sufficient cells per population (minimum 500-1000 cells per type)

- Control inclusion: Plan for positive and negative control genes in validation assays

- Replication strategy: Include biological and technical replicates

Quality Control Implementation:

Conservative Marker Identification:

- Use multiple differential expression methods (Wilcoxon, DESeq2, MAST)

- Require consistent fold-change across imputation methods

- Prioritize genes with clear biological plausibility and literature support

Orthogonal Validation Priority:

This systematic approach to addressing excessive zeros in scRNA-seq data will significantly improve the reliability of your validation studies and ensure that your findings reflect true biology rather than technical artifacts.

Accurate identification and quantification of low-abundance transcripts is crucial in validation research, from biomarker discovery to understanding drug mechanisms. However, common normalization procedures in RNA-seq data analysis can systematically bias against these informative molecules. This guide details the specific pitfalls that can obscure low-expression genes and provides actionable solutions to ensure your results accurately reflect biological reality.

FAQ: Normalization and Low-Abundance Transcripts

What are the most common normalization methods that affect low-abundance transcripts?

The most prevalent normalization methods that impact low-expression genes include:

- Total count normalization (e.g., TPM, RPKM/FPKM): These methods express counts as proportions of the total library, making them highly sensitive to changes in highly expressed genes [15] [16].

- Rarefying: Subsampling reads to equal depth across samples, which discards data and can eliminate low-count transcripts [17] [18].

- Aggressive filtering: Removing genes with low counts across samples, which may eliminate genuine low-abundance transcripts [19].

- Digital normalization (deduplication): Removing presumed PCR duplicates, which can disproportionately affect highly expressed genes and distort abundance estimates [20].

Why are low-abundance transcripts particularly vulnerable to normalization artifacts?

Low-expression genes are more susceptible to normalization artifacts due to several factors:

- Statistical instability: Low counts have higher relative variance, making them more easily influenced by global adjustments [19].

- Compositional effects: When a few highly expressed genes dominate the library, proportion-based normalization artificially deflates counts for all other genes [15] [16].

- Threshold effects: Filtering steps often use arbitrary count thresholds that may eliminate genuine low-abundance transcripts [19] [20].

- Degradation bias: Low-expression transcripts are more severely affected by sample degradation, which varies gene-by-gene [21].

How does library preparation protocol affect normalization of low-expression genes?

Different RNA extraction and library preparation methods dramatically alter transcriptome representation:

Table 1: Impact of Library Preparation Protocols on Transcript Detection

| Protocol | Effect on Low-Abundance Transcripts | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A)+ selection | Primarily captures mature mRNAs with poly(A) tails; may miss non-polyadenylated transcripts [15] | Optimal for standard mRNA quantification but limited in scope |

| rRNA depletion | Can sequence both mature and immature transcripts; may improve detection of certain low-abundance classes [15] | Increases complexity, potentially diluting rare transcript signals |

| Degraded samples | Low-expression genes show greater vulnerability to degradation effects [21] | Requires specialized normalization (e.g., DegNorm) |

What evidence exists that normalization affects differential expression results for low-expression genes?

Empirical studies demonstrate significant impacts:

- Filtering 15% of lowest-expressed genes increased true positive DEG detection by 480 genes in one benchmark study [19].

- The optimal filtering threshold varies significantly with RNA-seq pipeline components, particularly reference annotation and DEG detection tool [19].

- In microbiome data (which shares characteristics with RNA-seq), rarefying controlled false discovery rates better than alternatives when library sizes varied substantially (~10× difference) [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Preserving Low-Abundance Transcripts

Problem: Consistently losing low-expression genes after normalization

Solutions:

- Apply appropriate filtering strategies:

Validate with spike-in controls: Use external RNA controls of known concentration to calibrate normalization performance across the expression range [19].

Employ degradation-aware normalization: For samples with potential degradation issues (common in clinical specimens), use methods like DegNorm that adjust for gene-specific degradation patterns [21].

Problem: Discrepancies in low-abundance transcript detection between replicate samples

Solutions:

- Address degradation heterogeneity:

Increase sequencing depth strategically: While more sequencing helps detect rare transcripts, prioritize longer, more accurate reads over extreme depth when using long-read technologies [22].

Incorporate replicate samples: Always include biological replicates to distinguish technical artifacts from true biological variation, especially for low-expression genes [22].

Problem: Inconsistent results when changing RNA-seq protocols or platforms

Solutions:

- Avoid cross-protocol comparisons: TPM and RPKM values are not directly comparable across different sample preparation protocols (e.g., polyA+ vs. ribosomal depletion) [15].

Use platform-specific benchmarks: When adopting long-read RNA-seq, recognize that quantification accuracy improves with read depth, while transcript identification benefits from longer, more accurate sequences [22].

Implement compositional data analysis: For datasets with major shifts in expression distributions, consider compositionally aware methods like ANCOM, which better controls false discoveries [18].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Normalization Impact on Low-Abundance Transcripts

Step 1: Experimental Design

- Include external RNA controls (ERCC spike-ins) with known concentrations across the expected expression range [19].

- Plan for sufficient biological replicates (≥3 per condition) to support statistical power for low-expression genes.

- Record RNA integrity numbers (RIN) for all samples to account for degradation variation [21].

Step 2: Data Processing with Low-Expression Preservation

Step 3: Systematic Normalization Evaluation

- Apply multiple normalization methods (e.g., TMM, RLE, upper quartile, TPM) in parallel.

- For each method, track the recovery of spike-in controls across concentration ranges.

- Compare the number of genes retained after filtering and their characteristics.

Step 4: Degradation Assessment and Correction

- Compute degradation metrics (TIN, mRIN, or DegNorm indices) for all samples [21].

- If degradation heterogeneity is detected, apply degradation-aware normalization.

- Verify that degradation correction preserves expected biological signals.

Step 5: Differential Expression Validation

- Perform differential expression analysis using normalized counts.

- Compare results across normalization methods, focusing on consistency in low-abundance candidates.

- Validate key low-abundance findings with orthogonal methods (qPCR, nanostring).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Low-Abundance Transcripts

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Normalization standards | Use mixes covering expected expression range; add before library prep [19] |

| RNA Integrity Standard | Sample quality assessment | RIN values >7 recommended; track for each sample [21] |

| PolyA+ RNA Standards | Protocol performance monitoring | Assess 3' bias and coverage uniformity [15] |

| Degradation-Resistant Reagents | RNA preservation | RNase inhibitors, specialized storage buffers for field/clinical samples [21] |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for preserving low-abundance transcripts throughout RNA-seq analysis.

Diagram 2: Common normalization pitfalls and corresponding solutions for low-abundance transcript preservation.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does the Gene Homeostasis Z-Index differ from traditional gene variability metrics? The Gene Homeostasis Z-Index specifically identifies genes that are upregulated in a small proportion of cells, which traditional mean-based variability metrics often overlook. While conventional measures like variance or coefficient of variation (CV) quantify fluctuation relative to mean expression, the Z-index focuses on stability—the proportion of cells where a gene's expression aligns with baseline status. It detects genes whose variability stems from sharp upregulation in minor cell subsets, revealing active regulatory dynamics that traditional methods miss [23].

Q2: My dataset contains many low-expression genes. Should I filter them before applying the Z-index analysis? Filtering low-expression genes requires careful consideration. Studies show that appropriate filtering can increase sensitivity and precision of gene detection. Removing the lowest 15% of genes by average read count was found to maximize detection of differentially expressed genes. However, the optimal threshold depends on your RNA-seq pipeline, particularly the transcriptome annotation and DEG identification tool used. We recommend determining a threshold by maximizing the number of detected genes of interest for your specific pipeline [19].

Q3: What does a "significant Z-index" indicate biologically in my single-cell data? A significant Z-index indicates a gene under active regulation within specific cell subsets, suggesting compensatory activity or response to stimuli. For example, in CD34+ cell analysis, significant Z-index values revealed H3F3B and GSTO1 involved in cellular oxidant detoxification in subgroup 1, PRSS1 and PRSS3 revealing digestive activities in subgroup 2, and NKG7 and GNLY associated with cell-killing activities in subgroup 3. These patterns represent regulatory heterogeneity not observable with mean-based approaches [23].

Q4: Can the Z-index help identify genes that are important but expressed at low levels? Yes, this is a key advantage. The Z-index specifically captures genes with low stability, indicating differential regulation within specific cell subsets, even when overall expression appears low. This is particularly valuable for detecting important regulatory genes that might be filtered out by low-expression thresholds. The method identifies "droplets" on wave plots—genes with expression patterns deviating from the negative binomial distribution expected of homeostatic genes [23].

Troubleshooting Common Analysis Issues

Issue 1: Inconsistent Z-index results across cell populations

Problem: Z-index values vary dramatically between what should be similar cell types. Solution:

- Generate separate wave plots for each distinct cell subgroup identified through clustering

- Calculate subgroup-specific dispersion parameters, as heterogeneity significantly affects these values

- Consider that subgroup 2 in CD34+ cells showed dispersion of 0.526 versus 0.163 in the more homogeneous subgroup 3 [23]

- Ensure you're using appropriate controls and verify cell type annotations

Issue 2: Poor separation between regulatory and homeostatic genes

Problem: The "droplet" pattern on your wave plot is unclear, with few obvious outliers. Solution:

- Verify your data follows a negative binomial distribution for most genes

- Check that dispersion parameter estimation is accurate

- Confirm sufficient cell numbers (benchmark simulations used n=200 cells) [23]

- Examine whether bulk analysis might be masking cell-specific signals—consider single-cell resolution instead of pooled data [24]

Issue 3: Discrepancy between mRNA stability signals and protein outcomes

Problem: Genes with significant Z-index values don't correlate with expected functional protein changes. Solution:

- Remember that biological regulation involves multiple confounding factors

- Consider post-transcriptional and translational regulations that may disrupt mRNA-protein correlation [24]

- Integrate proteomic data where possible to validate functional outcomes

- Explore epigenetic regulation aspects including DNA methylation and histone modifications that might affect ultimate protein expression [24]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Gene Homeostasis Z-Index Calculation Protocol

Objective: To identify genes under active regulation within specific cell subsets using the gene homeostasis Z-index.

Methodology Overview: The Z-index is derived through a k-proportion inflation test that compares observed versus expected k-proportions—the percentage of cells with expression levels below an integer value k determined by mean gene expression count [23].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Input: Normalized single-cell RNA sequencing data (cells × genes matrix)

- Filter cells based on quality control metrics (mitochondrial content, number of features)

- Optional: Perform preliminary clustering to identify major cell populations

k-Proportion Calculation

- For each gene, calculate mean expression count across all cells

- Determine integer value k based on the mean expression count

- Calculate observed k-proportion: percentage of cells with expression < k

- This represents cells with considerably lower expression than the mean [23]

Expected Distribution Modeling

- Assume most genes are homeostatic and follow a negative binomial distribution

- Estimate a shared dispersion parameter empirically from the gene population

- Generate expected k-proportion values from negative binomial distributions with the same dispersion [23]

Z-Index Computation

- Perform k-proportion inflation test comparing observed vs. expected k-proportions

- Leverage asymptotic normality under null hypothesis to obtain Z-scores

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons

- Interpret higher Z-index values as indicating more active regulation or compensatory activity [23]

Benchmarking Protocol Against Variability Metrics

Objective: To validate Z-index performance against established variability measures.

Procedure:

- Comparison Metrics Selection:

- Include scran, Seurat VST, and Seurat MVP as established effective variability metrics [23]

- Exclude CV due to numerical instability in simulations

Simulation Framework:

- Generate baseline data for 5000 genes following negative binomial distribution

- Use dispersion parameter of 0.5 and mean expression of 0.25 (empirical estimates from real data)

- Introduce 200 "inflated genes" with outliers of varying magnitude (2, 4, or 8) and percentage of affected cells (2%, 5%, or 10%) [23]

Performance Evaluation:

- Use receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess overall performance

- Convert method estimates to quantiles for comparison with true labels

- Calculate sensitivity and specificity across thresholds [23]

Data Presentation

Performance Comparison of Gene Stability and Variability Metrics

Table 1: Simulation results comparing Z-index performance against variability metrics under different regulatory scenarios [23]

| Method | Low Outlier Expression | High Outlier Expression | Low % Cells (2-5%) | High % Cells (10%) | Type I Error Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-index | Competitive with Seurat MVP and SCRAN | Stable performance, superior to degrading methods | Subtle performance differences | Clearly superior, ROC curves closer to top-left | Well-calibrated, approximates normal distribution |

| SCRAN | Effective for capturing cell-to-cell variability | Performance degrades with sharper regulation | Effective | Less resilient against increasing biases | Challenging to control with arbitrary cut-offs |

| Seurat VST | Surpassed by Z-index in certain sensitivity ranges | Performance shifts with increasing expression | Effective | Performance differences become starker | Not explicitly reported |

| Seurat MVP | Competitive with Z-index at low outlier expression | Performance degrades | Effective | Less resilient than Z-index | Not explicitly reported |

Significantly Regulated Genes Identified by Z-index in CD34+ Cell Subgroups

Table 2: Cell subtype-specific regulatory patterns revealed by Z-index analysis [23]

| Cell Subgroup | Putative Identity | Genes with Significant Z-index | Biological Activities Revealed | Dispersion Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup 1 | Megakaryocyte progenitors | H3F3B, GSTO1, TSC22D1, CLIC1, LYL1, FAM110A | Cellular oxidant detoxification | Moderate (Not specified) |

| Subgroup 2 | Antigen-presenting cell progenitors | PRSS1, PRSS3 | Digestive activities | High (0.526) |

| Subgroup 3 | Early T cell progenitors | NKG7, GNLY | Cell-killing activities | Low (0.163) |

| Combined Analysis | Multiple lineages | HLA and RPL families, MAP3K7CL | Cytoplasmic translation, processing of exogenous peptide antigen, signal transmission | High (1.4) |

Visualization Diagrams

Gene Homeostasis Z-index Workflow

Z-index Analytical Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key resources for implementing Gene Homeostasis Z-index analysis [23] [19]

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Framework | k-proportion inflation test | Identifies genes with significantly higher k-proportion than expected | Core metric for Z-index calculation |

| Reference Distribution | Negative binomial distribution | Models expected expression pattern for homeostatic genes | Shared dispersion parameter estimated empirically from data |

| Benchmarking Metrics | scran, Seurat VST, Seurat MVP | Comparison against established variability measures | Exclude CV due to numerical instability in simulations |

| Data Simulation | Negative binomial model with inflated genes | Method validation under controlled conditions | Use 5000 genes, 200 cells, dispersion=0.5, mean=0.25 as baseline [23] |

| Filtering Guidance | Average read count threshold | Optimizes detection sensitivity | ~15% filtering maximizes DEG detection; varies by pipeline [19] |

| Multiple Testing Correction | False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Controls for false positives in significance testing | Benjamini-Hochberg method recommended |

Methodological Arsenal: Computational and Experimental Tools for Enhanced Detection

Differential expression (DE) analysis is a cornerstone of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies, enabling the identification of cell-type-specific responses to disease, treatment, and other biological stimuli. However, the unique characteristics of scRNA-seq data—including high sparsity, technical noise, and complex experimental designs—present significant challenges that are not adequately addressed by methods designed for bulk RNA-seq. This technical support article, framed within a broader thesis on addressing low-expression genes in validation research, provides a comprehensive benchmarking overview and practical guidance for selecting and implementing DE methods. We synthesize evidence from large-scale benchmarking studies to help researchers and drug development professionals navigate the complex landscape of scRNA-seq DE analysis tools.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: When should I use scRNA-seq-specific DE methods versus adapted bulk methods? Benchmarking studies reveal that the optimal choice depends on your data characteristics and experimental design. For datasets with substantial batch effects, covariate models that include batch as a factor (e.g., MAST with covariate adjustment) generally outperform methods using pre-corrected data [25]. When analyzing data with very low sequencing depth, limmatrend and Wilcoxon test applied to uncorrected data show more robust performance than zero-inflation models, which tend to deteriorate under extreme sparsity [25]. For complex multi-subject designs with repeated measures, mixed models such as NEBULA-HL and glmmTMB typically outperform other approaches because they properly account for within-sample correlation [26].

Q2: How does data sparsity (zero inflation) impact DE method performance? Excessive zeros represent a major challenge in scRNA-seq DE analysis, often referred to as "the curse of zeros" [27]. While many methods attempt to address zero inflation through imputation or specialized modeling, benchmarking shows that aggressive filtering of genes based on zero rates can discard biologically meaningful signals [27]. Methods that explicitly model zeros as part of a hurdle model (e.g., MAST) can be beneficial, but their performance advantage diminishes with very low sequencing depths [25]. For genes with genuine biological zeros (true non-expression), methods that preserve this information rather than imputing missing values generally yield more biologically interpretable results [27].

Q3: What normalization strategy should I use for scRNA-seq DE analysis? The choice of normalization strategy significantly impacts DE results. Library-size normalization methods (e.g., CPM) commonly used in bulk RNA-seq convert UMI-based scRNA-seq data from absolute to relative abundances, potentially obscuring biological signals [27]. Studies demonstrate that different normalization methods substantially alter the distribution of both zero and non-zero counts, affecting downstream DE detection [27]. For UMI-based protocols that enable absolute quantification, methods that bypass traditional normalization or use the cellular sequencing depth as an offset may preserve more biologically relevant information [28].

Q4: How do I properly account for batch effects and biological replicates in DE analysis? Benchmarking reveals two primary effective strategies for handling batch effects: (1) covariate modeling, where batch is included as a covariate in the DE model, and (2) mixed models, which treat batch as a random effect [25] [26]. For balanced designs where each batch contains both conditions, covariate modeling generally improves performance, particularly for large batch effects [25]. For unbalanced designs or studies with multiple biological replicates, methods that account for within-sample correlation (e.g., NEBULA-HL, glmmTMB) significantly reduce false discoveries by properly modeling the hierarchical data structure [26]. Simple batch correction methods followed by pooled analysis often underperform these more sophisticated approaches.

Common Issues and Solutions

Issue: High False Discovery Rates (FDR) in DE Results Solution: Implement methods that properly account for biological replicate variation. Mixed models such as NEBULA-HL and glmmTMB demonstrate superior FDR control in multi-subject scRNA-seq studies compared to methods that treat all cells as independent observations [26]. Additionally, ensure your normalization strategy preserves biological variation rather than introducing artifacts.

Issue: Poor Performance with Low Sequencing Depth Data Solution: For very sparse data (average nonzero count <10), simpler methods like limmatrend, Wilcoxon test, and fixed effects models on log-normalized data generally outperform more complex zero-inflated models [25]. Consider using pseudobulk approaches that aggregate counts to the sample level, which show improved performance for low-depth data when batch effects are minimal [25].

Issue: Inconsistent Results Across Batches or Platforms Solution: Utilize covariate adjustment rather than pre-corrected data. Benchmarking shows that DE analysis using batch-corrected data rarely improves performance for sparse data, whereas directly modeling batch as a covariate in the DE model maintains data integrity while accounting for technical variation [25]. For multi-batch experiments, ensure your study design is balanced where possible, with each batch containing representatives from all conditions being compared.

Quantitative Benchmarking Results

Performance of DE Methods Across Experimental Conditions

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DE Method Categories Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Optimal Use Cases | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq Adapted | limmatrend, DESeq2, edgeR | Moderate sequencing depth; Minimal batch effects | Computational efficiency; Well-understood statistical properties | Poor handling of zero inflation; Doesn't account for cellular correlation |

| scRNA-seq Specific | MAST, scDE | Balanced batch effects; High-quality data | Explicit modeling of zero inflation; Designed for single-cell characteristics | Performance deteriorates with low depth; Complex implementation |

| Mixed Models | NEBULA-HL, glmmTMB | Multi-subject designs; Complex experimental designs | Properly accounts for within-sample correlation; Excellent FDR control | Computational intensity; Complex model specification |

| Non-parametric | Wilcoxon test | Low sequencing depth; Exploratory analysis | Robust to distributional assumptions; Simple implementation | Lower power for subtle effects; Limited covariate integration |

| Pseudobulk Approaches | edgeR on aggregated counts | Multi-sample comparisons; Population-level effects | Reduces false positives from correlated cells; Uses established methods | Loses single-cell resolution; Masks cellular heterogeneity |

Table 2: Impact of Data Characteristics on Method Performance

| Data Characteristic | High-Performing Methods | Low-Performing Methods | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Batch Effects | MASTCov, ZWedgeR_Cov | Pseudobulk methods, Naïve pooling | F0.5-score: Covariate models >15% higher than pseudobulk [25] |

| Low Sequencing Depth | limmatrend, LogN_FEM, Wilcoxon | ZINB-WaVE with observation weights | Relative performance: limmatrend >30% higher than ZINB-WaVE for depth-4 [25] |

| High Zero Inflation | GLIMES, MAST | Methods with aggressive zero-filtering | AUPR: GLIMES >20% higher than conventional methods [27] |

| Multiple Biological Replicates | NEBULA-HL, glmmTMB | Cell-level methods ignoring sample structure | FDR control: Mixed models <5% vs >15% for methods ignoring sample structure [26] |

| Complex Covariates | GLIMES, Mixed Models | Simple linear models | Power: Covariate-adjusted models >25% higher for confounded designs [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Benchmarking Workflow for Differential Expression Methods

Diagram 1: Benchmarking workflow for DE methods

Protocol 1: Benchmarking DE Methods with Synthetic Data

Purpose: To evaluate differential expression methods using data with known ground truth.

Materials:

- MSMC-Sim simulator or Splatter package for synthetic data generation [26] [25]

- Computing environment with R and necessary DE method packages

- Performance evaluation metrics (AUPR, FDR, Power)

Procedure:

- Parameter Specification: Define simulation parameters including number of cells (20-500), number of genes (500-2000), effect sizes (1-3.5), proportion of DE genes (0.1), and zero inflation parameters [28].

- Data Generation: Use simulators to generate synthetic datasets with known differentially expressed genes. Incorporate realistic data characteristics including subject-to-subject variation, batch effects, and varying sequencing depths [26].

- Method Application: Apply each DE method to the simulated datasets. Include both scRNA-seq specific methods (MAST, glmmTMB, NEBULA) and adapted bulk methods (limmatrend, DESeq2, edgeR) [25] [26].

- Performance Assessment: Calculate precision-recall curves, false discovery rates, and statistical power for each method. Place greater emphasis on precision (F0.5-score) due to the importance of identifying a small number of marker genes from sparse scRNA-seq data [25].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Repeat simulations across varying conditions including different levels of batch effects, sequencing depths, and data sparsity to identify robust performers.

Protocol 2: Validation with Real scRNA-seq Data

Purpose: To verify benchmarking results using real experimental data.

Materials:

- Publicly available scRNA-seq datasets with multiple conditions and replicates (e.g., lung adenocarcinoma, COVID-19 datasets) [25]

- Annotated cell type markers for validation

- Computing environment with Seurat, Bioconductor packages

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain real scRNA-seq datasets from public repositories that include multiple biological replicates and conditions. Suitable datasets include those from disease studies such as multiple sclerosis or pulmonary fibrosis [26].

- Preprocessing: Perform standard quality control including filtering of low-quality cells and genes. Filter genes with zero rates >0.95 to focus on reasonably expressed genes [25].

- Cell Type Identification: Use clustering and annotation to identify major cell types. Focus DE analysis on specific cell types rather than heterogeneous cell populations.

- Method Application: Apply multiple DE methods to the real data. Include both high-performing methods from synthetic benchmarks and commonly used approaches.

- Biological Validation: Assess the ability of each method to prioritize known disease-related genes and prognostic markers. Compare the ranks of established marker genes between methods [25].

- Consensus Analysis: Identify genes consistently called as differentially expressed across multiple high-performing methods to generate robust biological insights.

Method Selection Framework

Diagram 2: Method selection decision framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq DE Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DE Method Implementations | MAST, NEBULA, glmmTMB, limmatrend | Statistical testing for differential expression | Cell-type-specific DE analysis across conditions |

| Data Simulation | MSMC-Sim, Splatter, Biomodelling.jl | Generate synthetic data with known ground truth | Method benchmarking and power calculations |

| Batch Correction | Harmony, Seurat CCA, scVI, ComBat | Remove technical variation between batches | Multi-sample, multi-batch studies |

| Normalization | SCTransform, scran, Linnorm | Adjust for technical covariates | Preprocessing prior to DE analysis |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | BenchmarkSingleCell (R package) | Compare method performance | Evaluation of new methods vs. established approaches |

| Visualization | Seurat, SCope, iCOBRA | Explore and present results | Interpretation and communication of findings |

The benchmarking of differential expression methods for scRNA-seq data reveals that method performance is highly context-dependent, influenced by data sparsity, batch effects, sequencing depth, and experimental design. While no single method dominates all scenarios, clear recommendations emerge: mixed models excel for multi-subject designs, covariate adjustment outperforms batch correction for balanced designs, and simpler methods often show superior performance for low-depth data. By following the guidelines, protocols, and decision frameworks presented in this technical support document, researchers can make informed choices about DE method selection, properly account for technical and biological sources of variation, and generate more robust and reproducible results in their single-cell studies.

Leveraging Perturbation Gene Expression Profiles for Mechanistic Validation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is filtering low-expression genes necessary in perturbation studies? Filtering low-expression genes is a common practice because these genes can be indistinguishable from sampling noise. Their presence can decrease the sensitivity of detecting differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Proper filtering increases both the sensitivity and precision of DEG detection, ensuring that the downstream mechanistic analysis focuses on reliable transcriptional changes [19].

Q2: How do I choose a method and threshold for filtering low-expression genes? The choice of method and threshold is critical. Evidence suggests that using the average read count as a filtering statistic is ideal. For the threshold, a practical approach is to choose the level that maximizes the number of detected DEGs in your dataset, as this has been shown to correlate closely with the threshold that maximizes the true positive rate. It is important to note that the optimal threshold can vary depending on your RNA-seq pipeline (e.g., transcriptome annotation and DEG detection tool) [19].

Q3: What are the main types of perturbation gene expression datasets available? Several large-scale datasets are available for in silico analysis:

- Connectivity Map (LINCS): A large compendium containing over 3 million gene expression profiles from L1000 assays, covering both chemical and genetic perturbations [29].

- CREEDS: A crowdsourced collection of perturbation signatures from public repositories like GEO [29].

- PANACEA: A resource of anti-cancer drug perturbation signatures measured with RNA-seq in multiple cell lines [29].

- CIGS: An extensive dataset of chemical-induced gene signatures across thousands of compounds [30].

- Perturb-Seq: Provides genome-wide genetic perturbation data combined with single-cell RNA-seq [29].

Q4: My in silico perturbation fails with multiprocessing errors. How can I fix this? This is a known technical issue when using tools like Geneformer. The solution is to ensure the correct start method is set for multiprocessing. Adding the following code to the beginning of your script typically resolves the problem:

Additionally, running your data from a local scratch drive instead of a network mount can prevent process disruptions [31].

Q5: How can perturbation profiles help identify a drug's mechanism of action (MoA)? The core principle is that compounds sharing a mechanism of action induce similar gene expression changes. By comparing the gene expression signature of an uncharacterized compound to a database of signatures from perturbations with known targets or MoAs, you can infer its biological mechanism. This is often done by calculating signature similarity scores [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Detection of Differentially Expressed Genes

Problem: You suspect that noisy, low-expression genes are obscuring true differential expression signals in your perturbation experiment.

Solution: Apply a systematic low-expression gene filtering strategy.

- Calculate Filtering Statistic: For each gene, calculate its average read count or average Counts Per Million (CPM) across all samples [19].

- Determine Optimal Threshold: Generate a series of filtering thresholds based on the percentile of your chosen statistic. For each threshold, perform your standard DEG analysis and note the total number of DEGs detected.

- Select Threshold: Choose the filtering threshold that corresponds to the maximum number of DEGs detected. As shown in the table below, this threshold typically also offers a favorable balance of sensitivity and precision [19].

Table 1: Effect of Low-Expression Gene Filtering on DEG Detection (Example Data)

| Genes Filtered (%) | Total DEGs Detected | True Positive Rate (TPR) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (No filter) | 3,200 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| 5% | 3,450 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| 10% | 3,610 | 0.78 | 0.84 |

| 15% | 3,680 | 0.79 | 0.85 |

| 20% | 3,650 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

| 30% | 3,400 | 0.75 | 0.87 |

Issue 2: Interpreting Gene Expression Changes for Mechanistic Insights

Problem: You have a list of DEGs from a perturbation experiment but are struggling to derive a coherent biological mechanism.

Solution: Utilize perturbation profile databases and pathway-centric analysis.

- Signature Comparison: Compare your DEG signature (e.g., the list of up- and down-regulated genes) against a reference database like Connectivity Map or CREEDS. This can identify known drugs or genetic perturbations that elicit a similar response, pointing to a shared MoA or pathway [29] [30].

- Leverage Advanced Models: Use large-scale computational models like the Large Perturbation Model (LPM). The LPM integrates data from diverse perturbation experiments and can map both chemical and genetic perturbations into a shared latent space. In this space, perturbations targeting the same gene or pathway cluster together, providing a powerful tool for mechanistic hypothesis generation [32].

- Contextualize with Pathway Tools: Input your DEG list into pathway enrichment analysis tools to identify statistically overrepresented biological processes, molecular functions, and signaling pathways. The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow for mechanistic validation.

Issue 3: Selecting an Appropriate Perturbation Profile Database

Problem: The numerous available databases have different strengths, making selection difficult.

Solution: Choose a database based on your perturbation type and experimental goals. The following table summarizes key resources.

Table 2: Key Perturbation Gene Expression Profile Databases

| Database Name | Perturbation Types | Key Features & Technology | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity Map (LINCS) [29] | Chemical, Genetic | L1000 assay; >1 million profiles; reduced transcriptome (978 genes) | Large-scale MoA identification and drug repurposing |

| CREEDS [29] | Chemical, Genetic | Crowdsourced from GEO; uniformly processed metadata | Accessing a wide range of published perturbation data |

| PANACEA [29] | Chemical (Anti-cancer) | RNA-seq; multiple cell lines | Studying anti-cancer drug mechanisms |

| CIGS [30] | Chemical | HTS2 and HiMAP-seq; 13k+ compounds; 3,407 genes | Elucidating MoA for unannotated small molecules |

| Perturb-Seq [29] | Genetic (CRISPR) | Single-cell RNA-seq; genome-wide perturbations | Analyzing perturbation effects with single-cell resolution |

| Large Perturbation Model (LPM) [32] | Chemical, Genetic | Deep learning model integrating multiple datasets | Predicting perturbation outcomes and mapping shared mechanisms in silico |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Perturbation-Expression Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Guides (for Perturb-Seq) [29] | To introduce targeted genetic perturbations (knockout/knockdown). | Specificity (minimize off-target effects); expressed barcodes are needed to link guide to cell. |

| shRNA Constructs [29] | To introduce gene knockdown perturbations. | Can lead to partial inhibition, which may better mimic some drug effects than full knockout. |

| L1000 Assay Kit [29] | High-throughput, low-cost gene expression profiling of a reduced transcriptome. | Only directly measures 978 "landmark" genes; the rest are computationally inferred. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls [19] | External RNA controls added to samples to help calibrate and troubleshoot sequencing experiments. | Used to estimate technical noise and the limit of detection for low-expression genes. |

| Cell Line Barcodes (for MIX-Seq) [29] | Allows pooling of multiple cell lines into a single sequencing run, reducing costs and batch effects. | Requires SNP-based computational demultiplexing to assign reads to the correct cell line of origin. |

FAQs on Probe Performance and Low-Expression Genes

Q1: Why is my signal intensity weak when using long oligonucleotide probes to detect low-expression genes?

Weak signal intensity often stems from two main categories of issues: probe assembly efficiency on the target or suboptimal detection conditions.

- Low Probe Assembly Efficiency: For methods like MERFISH that use encoding probes, the number of probes successfully binding to each RNA molecule directly determines signal brightness. Inefficient hybridization, often due to non-optimal denaturing conditions (e.g., formamide concentration and temperature), can drastically reduce this assembly efficiency [33].

- Suboptimal Detection Chemistry: The performance of fluorescently labeled readout probes can degrade over time. The "aging" of reagents during multi-day experiments can lead to a drop in signal. Furthermore, the choice of imaging buffer significantly impacts fluorophore photostability and effective brightness [33].

- Probe and Target Accessibility: The secondary structure of the target RNA molecule can physically block probe binding sites. This is a common cause of false-negative results, as some target regions may be inaccessible despite using well-designed probes [34].

Q2: How can I reduce high background noise with long oligonucleotide probes?

High background is frequently caused by non-specific binding of probes or the presence of unincorporated fluorescent dye.

- Insufficient Purification: After conjugating a fluorophore to an oligonucleotide, incomplete removal of the unreacted, free dye is a major source of background fluorescence. Purification methods like HPLC or gel electrophoresis are essential to remove this contaminant [35].

- Non-Specific Probe Binding: Readout probes can bind non-specifically in a tissue- and sequence-dependent manner. This can introduce false-positive signals. Pre-screening readout probes against your specific sample type can help identify and mitigate this issue [33].

- Off-Target Hybridization: The presence of excess, unbound probe in the hybridization solution contributes to background. Ensuring stringent post-hybridization wash conditions, such as increasing SDS concentration or adjusting wash times, can help reduce this noise [34].

Q3: What are the critical steps for labeling oligonucleotides with fluorophores?

The efficiency of the labeling reaction is paramount for achieving strong signals.

- Dye Reactivity and Storage: Amine-reactive dyes, such as Alexa Fluor dyes, are sensitive to hydrolysis. They must be stored as a powder, desiccated, and protected from light. Once dissolved in anhydrous DMSO, the dye solution should be used immediately to prevent loss of reactivity [35].

- Reaction Buffer and pH: The conjugation reaction works best at a slightly basic pH (e.g., pH 8.5) to ensure the amine group on the oligonucleotide is deprotonated and reactive. Using the recommended borate buffer is critical; other buffers like Tris or those containing ammonium salts will interfere with the reaction [35].

- Purity of Starting Material: The amine-modified oligonucleotide must be thoroughly purified before the reaction to remove any contaminating primary amines (e.g., Tris, glycine, BSA), which will compete for the reactive dye and reduce labeling efficiency [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Design & Synthesis | Rapid loss of coupling efficiency during synthesis [36]. | Hydrolysis of phosphoramidite synthons by trace water [36]. | Treat synthons with 3 Å molecular sieves for 2+ days prior to use [36]. |

| Incomplete removal of 2'-O-silyl protecting groups in RNA synthesis [36]. | High water content in deprotection reagent (TBAF) [36]. | Treat TBAF with molecular sieves upon arrival; use small reagent bottles to minimize moisture uptake [36]. | |

| Hybridization Efficiency | Variable signal quality, poor performance with pyrimidine-rich sequences [36]. | Water in reagents affecting reaction kinetics; pyrimidines more sensitive to water than purines [36]. | Ensure absolute dryness of all reagents with molecular sieves [36]. |

| Weak single-molecule signal intensity in smFISH [33]. | Suboptimal hybridization conditions leading to low encoding probe assembly efficiency [33]. | Screen a range of formamide concentrations (e.g., 10%-30%) at a fixed temperature (e.g., 37°C) to find the optimum [33]. | |

| Signal Detection & Specificity | High background fluorescence after probe labeling [35]. | Insufficient removal of free, unreacted dye after the conjugation reaction [35]. | Purify labeled oligonucleotides via HPLC or gel electrophoresis to remove unincorporated dye [35]. |

| False-positive counts in MERFISH measurements [33]. | Non-specific, tissue-dependent binding of individual readout probes [33]. | Pre-screen readout probes against the sample of interest to identify and replace problematic sequences [33]. | |

| Reagent Stability | Signal intensity decreases over the course of a multi-day experiment [33]. | "Aging" of fluorescent reagents; loss of performance over time [33]. | Introduce protocol modifications to buffer composition to improve reagent photostability and longevity [33]. |

Quantitative Data for Protocol Optimization

Table 1: Effect of Target Region Length on Single-Molecule Signal Brightness [33]

| Target Region Length | Optimal Formamide Range | Relative Signal Brightness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nt | To be optimized empirically | Baseline | Shorter regions may be more susceptible to secondary structure effects. |

| 30 nt | To be optimized empirically | Comparable to 40nt/50nt | Offers a balance between specificity and synthesis cost. |

| 40 nt | To be optimized empirically | High | Often used as a standard; provides good assembly efficiency. |

| 50 nt | To be optimized empirically | High | Maximal binding energy, but cost and potential for non-specificity may increase. |

Table 2: Impact of Low-Expression Gene Filtering on DEG Detection Sensitivity [19]

| Filtering Threshold (% Genes Removed) | True Positive Rate (TPR) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Total DEGs Detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (No Filter) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| 15% | Increases | Increases | Maximum (e.g., +480 DEGs) |

| >30% | Decreases | High | Decreases |

Note: The optimal threshold (often ~15% for average read count method) can vary with the RNA-seq pipeline (annotation, quantification, and DEG tool) [19].

Experimental Protocols for Key Optimizations

Protocol 1: Optimizing Hybridization Conditions for smFISH-Based Methods

This protocol is designed to maximize the assembly efficiency of encoding probes onto target RNAs, which directly translates to brighter single-molecule signals [33].

- Probe Set Design: Create multiple encoding probe sets (e.g., 80 probes per gene) with varying target region lengths (e.g., 20, 30, 40, and 50 nucleotides) for at least two genes with different expression levels. Affix common readout sequences to all probes [33].

- Hybridization Screening: For each probe set, prepare a series of hybridization buffers containing a gradient of formamide concentrations (e.g., 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%) while keeping the temperature constant at 37°C.

- Sample Processing: Hybridize each probe set to fixed cell samples (e.g., U-2 OS cells) for a standardized duration (e.g., 1 day) using the different formamide buffers.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Perform smFISH and image single molecules. Quantify the average brightness of the single-molecule signals for each condition. The brightness serves as a proxy for probe assembly efficiency.

- Determine Optimal Conditions: Identify the formamide concentration and target region length that produce the brightest signals without increasing background. Research indicates that signal brightness depends weakly on target region length for regions of 30 nt or more, but the optimal formamide concentration must be determined empirically [33].

Protocol 2: Drying Water-Sensitive Reagents for Oligonucleotide Synthesis

This procedure is critical for maintaining the coupling efficiency of phosphoramidite synthons and the activity of deprotection reagents like TBAF [36].

- Obtain Materials: Acquire high-quality, activated 3 Å molecular sieves.

- Prepare Reagents: Place the water-sensitive reagent (e.g., phosphoramidite synthon or TBAF solution) in a sealed container.

- Add Molecular Sieves: Directly add the 3 Å molecular sieves to the reagent. Ensure the sieves are fresh and have not been fully saturated with water.

- Incubate: Allow the reagent to sit over the molecular sieves for a minimum of two days at room temperature in a dry environment.

- Verification: After treatment, the reagent should be tested for performance. For synthons, coupling efficiency should be restored to >95%. For TBAF, Karl Fisher titration can confirm reduced water content (e.g., to ~2%) [36].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimizing Oligonucleotide Probe Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 3 Å Molecular Sieves | Removes trace water from moisture-sensitive reagents like phosphoramidite synthons and TBAF, preserving their reactivity and efficiency [36]. | Must be freshly activated; requires 2+ days of treatment for full effect [36]. |

| Formamide | A chemical denaturant used in hybridization buffers to control stringency and facilitate probe access to the target RNA by melting secondary structures [33]. | Optimal concentration is target-length dependent and must be determined empirically for each probe set [33]. |

| Anhydrous DMSO | A polar, aprotic solvent used to dissolve amine-reactive dyes for oligonucleotide labeling without causing hydrolysis [35]. | Must be of the highest purity and used immediately after dissolving the dye to prevent water absorption [35]. |

| Sodium Borate Buffer (pH 8.5) | The recommended buffer for amine-labeling reactions, providing the slightly basic pH needed for efficient conjugation [35]. | Avoids amines (e.g., Tris) that would compete with the oligonucleotide and quench the reaction [35]. |

| HPLC / Gel Electrophoresis System | Critical for post-labeling purification to separate the fluorophore-conjugated oligonucleotide from unreacted free dye, which causes high background [35]. | Non-negotiable step after the labeling reaction to ensure clean probes and low background [35]. |

FAQs: Understanding Novel Stability Metrics

Q1: What is the key limitation of traditional mean-based analysis in gene expression studies? Traditional mean-based analysis, which often uses metrics like variance or coefficient of variation, cannot distinguish between genes with widespread variability across cells and genes whose apparent variability is driven by sharp upregulation in a small subset of cells. This latter pattern, indicative of active regulation, is often masked when focusing only on the mean [23].

Q2: How does the Gene Homeostasis Z-index address this limitation? The Gene Homeostasis Z-index is a novel stability metric designed to identify genes that are actively regulated in a small proportion of cells. It uses a k-proportion inflation test to determine if the number of cells with low expression levels is significantly higher than expected under a negative binomial distribution, which models homeostatic genes. A high Z-index indicates low stability and active regulation [23].

Q3: My data contains many low-expression genes. Is the Z-index applicable? Yes, the methodology for the Z-index was developed specifically for single-cell genomics data, which inherently contains many lowly expressed genes. The k-proportion metric is calculated based on the mean gene expression count, making it suitable for such datasets. Simulations show it performs robustly even with a mean expression as low as 0.25 [23].

Q4: In a validation experiment, what does a significant Z-index for a gene imply? A significant Z-index suggests that the gene is not stably expressed but is instead under active or compensatory regulation within a specific subset of cells in an otherwise homeostatic population. This can unveil regulatory heterogeneity that is crucial for understanding cellular adaptation and should be a key focus for further functional validation [23].

Q5: How do I know if the Z-index is more suitable for my dataset than variability-based methods? The Z-index is particularly advantageous when your biological question involves identifying rare cell subpopulations or genes that are sharply upregulated in only a few cells. Benchmarking simulations show that the Z-index matches or outperforms methods like scran and Seurat VST/MVP, especially when the upregulated expression in the outlier cells is high [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inability to Distinguish Regulatory Genes from Noisy Genes

Problem: Standard variability metrics flag many genes as interesting, but subsequent validation fails, likely because these genes are highly variable due to technical noise rather than true biological regulation.

Solution: Implement the Gene Homeostasis Z-index to pinpoint genes with evidence of active, subset-specific regulation.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Data Input: Ensure your data is a normalized gene expression matrix (cells x genes) from a relatively homogeneous cell population.

- Calculate k-proportion: For each gene, calculate the k-proportion, which is the percentage of cells where the expression level is below a value 'k'. The value of 'k' is determined based on the mean expression count for that gene [23].

- Fit Null Model: Assume the majority of genes are homeostatic and empirically estimate a shared dispersion parameter for a negative binomial distribution.

- Perform Inflation Test: For each gene, compare its observed k-proportion to the expected k-proportion under the null negative binomial model.

- Compute Z-index: The test statistic is asymptotically normal, yielding a Z-score (Z-index) for each gene. A significantly high Z-index indicates a gene with low stability and active regulation.

Validation Tip: Genes identified with a high Z-index should be prioritized for validation using orthogonal techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to confirm their expression is indeed restricted to a small subpopulation of cells.

Issue: Model Overfitting in High-Dimensional RNA-seq Data

Problem: When using machine learning for classification (e.g., cancer type) based on RNA-seq data, the high number of genes (features) relative to samples leads to overfitting and poor model performance on validation sets.

Solution: Integrate robust feature selection methods to identify a compact set of statistically significant genes before model training.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Preprocess Data: Check for and handle any missing values or outliers. The PANCAN dataset from UCI, for example, often contains no missing values [37].

- Apply Feature Selection: Use regularized regression models to downsample the number of features.

- Lasso (L1) Regression: Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the coefficients (

λΣ|βj|). This drives many coefficients to exactly zero, effectively performing feature selection [37]. - Ridge (L2) Regression: Adds a penalty equal to the square of the coefficients (

λΣβj^2). This shrinks coefficients but does not set them to zero, helping to manage multicollinearity [37].

- Lasso (L1) Regression: Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the coefficients (

- Train Classifiers: Use the selected features to train machine learning models. A study on cancer RNA-seq data found Support Vector Machines (SVM) achieved high accuracy (99.87%) with 5-fold cross-validation [37].

- Validate Rigorously: Always use a hold-out test set (e.g., 70/30 split) and cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold cross-validation) to obtain unbiased performance estimates [37].

Validation Tip: For external validation, apply your trained model to an independently sourced dataset, such as the Brain Cancer Gene Expression (CuMiDa) dataset, to test its generalizability [37].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Protocol: Implementing the k-proportion Inflation Test

This protocol outlines the steps to calculate the Gene Homeostasis Z-index for a single-cell RNA-seq dataset.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Normalized scRNA-seq Data | The foundational input data; a matrix of gene expression counts across a population of cells. |

| Computational Environment (e.g., R/Python) | Software platform for performing statistical calculations and implementing the algorithm. |

| Negative Binomial Distribution Model | The statistical null model used to define the expected distribution of homeostatic genes. |

| Shared Dispersion Parameter | An empirically estimated parameter that describes the overall variability of the homeostatic gene population. |

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Start with a quality-controlled and normalized single-cell gene expression matrix. It is crucial to analyze a defined, homogeneous cell population to avoid confounding effects from multiple cell types.

- Calculate Gene Statistics: For each gene in the matrix:

- Compute its mean expression across all cells.

- Determine the integer value k, which is based on this mean expression.

- Calculate the k-proportion: the percentage of cells with an expression level less than k [23].

- Estimate Population Parameters: Assume most genes are homeostatic. Use their expression profiles to empirically estimate a shared dispersion parameter for a negative binomial distribution.

- Hypothesis Testing: For each gene, test the null hypothesis that its expression follows the negative binomial distribution with the shared dispersion parameter. Specifically, test if the observed k-proportion is significantly inflated compared to the expected k-proportion under the null model.