Beyond the p-value: A Modern Guide to Accurate Differential Expression Analysis in Biomedical Research

Accurate detection of differentially expressed genes is fundamental for discovering biomarkers and therapeutic targets, yet common methods often produce misleading results.

Beyond the p-value: A Modern Guide to Accurate Differential Expression Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate detection of differentially expressed genes is fundamental for discovering biomarkers and therapeutic targets, yet common methods often produce misleading results. This article synthesizes recent findings on the critical challenges plaguing differential expression analysis, including inflated false positives in spatially-correlated and single-cell data, poor cross-study reproducibility, and the profound impact of normalization and experimental design. We provide a comprehensive framework covering robust statistical methodologies, best-practice workflows for single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, and advanced meta-analysis techniques for validation. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide offers actionable strategies to enhance the reliability and biological relevance of transcriptomic findings in preclinical and clinical research.

The Reproducibility Crisis: Why Standard Differential Expression Methods Often Fail

In the field of differential expression (DE) analysis, the reliability of research conclusions is fundamentally dependent on robust statistical control. The false discovery rate (FDR) is a key metric, representing the expected proportion of false positives among all findings declared significant. When properly controlled at a threshold of 5%, researchers can be confident that only 5% of their reported differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are likely to be spurious. However, a growing body of literature reveals an alarming epidemic of inflated Type I errors, where the actual FDR substantially exceeds the nominal threshold, jeopardizing the validity of published biological insights [1] [2]. This problem is particularly acute in studies with large sample sizes, where popular methods originally designed for small experimental setups can produce exaggerated false positives, potentially misdirecting research efforts and wasting valuable validation resources [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading DE methods, documents the scope of the problem with experimental data, and provides researchers with strategies to enhance the reproducibility of their findings.

Documented Cases of False Positive Inflation

Performance Failure in Population-Level RNA-seq Studies

A comprehensive 2022 investigation exposed severe FDR control failures in several popular DE methods when applied to large human population RNA-seq samples. The study performed permutation analyses on 13 datasets with sample sizes ranging from 100 to 1,376 individuals [1].

Table 1: Documented FDR Inflation in Population-Level Studies (Target FDR: 5%)

| Differential Expression Method | Type | Reported Actual FDR | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Parametric | Exceeded 20% | 84.88% chance of identifying more DEGs in permuted data than original data; 15.3% of original DEGs identified as spurious [1] |

| edgeR | Parametric | Exceeded 20% | 78.89% chance of identifying more DEGs in permuted data than original data; 60.8% of original DEGs identified as spurious [1] |

| limma-voom | Parametric | Failed FDR control | Consistantly showed exaggerated false positives compared to non-parametric methods [1] |

| NOISeq | Non-parametric | Failed FDR control | Failed to consistently maintain FDR at nominal thresholds [1] |

| dearseq | Non-parametric | Failed FDR control | Claimed to overcome FDR inflation but showed increased false positive rates in benchmark [1] |

| Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test | Non-parametric | Adequately controlled | Only method found to consistently control FDR across sample sizes and thresholds [1] |

The most striking finding was that genes with larger estimated fold changes were more likely to be identified as false positives in permuted datasets, directly contradicting the common biological assumption that large fold changes represent more reliable signals [1]. The investigation attributed these failures primarily to violations of the negative binomial distributional assumptions underlying parametric methods, particularly in the presence of outliers common in population-level data [1].

Reproducibility Crisis in Single-Cell Transcriptomics

The false positive epidemic extends to single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) studies, where reproducibility remains a substantial concern. A 2025 meta-analysis of neurodegenerative disease studies found that DEGs from individual datasets had poor predictive power when applied to other datasets [2].

Table 2: Reproducibility of DEGs in Individual scRNA-seq Studies

| Disease | Number of Studies | Reproducibility of DEGs | Predictive Power (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | 17 | >85% of DEGs failed to reproduce in any other study; <0.1% reproduced in >3 studies [2] | 0.68 |

| Schizophrenia (SCZ) | 3 | Poor reproducibility with very few overlapping DEGs across studies [2] | 0.55 |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | 6 | Moderate reproducibility | 0.77 |

| Huntington's Disease (HD) | 4 | Moderate reproducibility | 0.85 |

| COVID-19 | 16 | Moderate reproducibility; positive control with known strong transcriptional response [2] | 0.75 |

The analysis highlighted the case of LINGO1, a gene previously spotlighted in an AD review as a crucial oligodendrocyte DEG. The meta-analysis revealed this gene was not consistently upregulated across most datasets and was even downregulated in several studies, illustrating how false positive claims can persist in the literature [2].

Experimental Protocols & Methodological Debates

Permutation Testing for FDR Evaluation

The primary methodology for evaluating false positive rates in DE studies involves permutation testing, which creates negative control datasets where no true differential expression should exist.

Experimental Workflow for Permutation Analysis:

The standard approach involves randomly permuting condition labels across samples to generate null datasets, then applying DE methods to these datasets where any significant findings represent false positives [1]. However, a critical methodological debate emerged regarding whether permutation should occur before or after normalization. A 2024 response to the original FDR inflation study argued that the reported FDR inflation artifacts stemmed from permuting raw counts before normalization, which can introduce library size confounders [3]. When applying an amended permutation scheme (normalizing before permutation), the researchers demonstrated that methods including dearseq and limma-voom adequately controlled FDR [3].

The Normalization Controversy

The debate surrounding permutation schemes highlights the critical importance of normalization in DE analysis. The original study applied the Wilcoxon test to non-normalized data while testing other methods on normalized data, potentially biasing comparisons [3]. When researchers applied the Wilcoxon test to the same normalized data used by other methods, it also showed apparent FDR inflation under the original permutation scheme [3]. This suggests that the interaction between normalization and study design significantly impacts FDR control, particularly for large sample sizes where subtle biases can produce substantial inflation.

Comparative Performance of Alternative Methods

Method Classifications and Characteristics

DE methods can be broadly categorized by their statistical approaches and underlying assumptions:

Table 3: Differential Expression Method Classification

| Method | Classification | Underlying Model | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Parametric | Negative Binomial | Data follows negative binomial distribution; mean-variance relationship can be modeled [1] |

| edgeR | Parametric | Negative Binomial | Similar to DESeq2 with different estimation approaches for dispersion parameters [1] |

| limma-voom | Parametric | Linear Model | Precision weights can account for mean-variance relationship in log-counts [1] |

| Wilcoxon Test | Non-parametric | Rank-Based | No specific distributional assumptions; focuses on relative ranks rather than magnitudes [1] |

| dearseq | Non-parametric | Variance Component | Designed for large sample sizes; uses variance component score test [3] |

| NOISeq | Non-parametric | Empirical | Non-parametric method using empirical distributions [1] |

Performance Across Sample Sizes

The performance of DE methods varies significantly with sample size. The original FDR inflation study included sample size down-sampling experiments, revealing that the Wilcoxon rank-sum test consistently controlled FDR across all sample sizes, though it had limited power with fewer than 8 samples per condition [1]. In contrast, parametric methods showed FDR inflation even at moderate sample sizes. However, a follow-up study argued that when properly normalized and evaluated with an amended permutation scheme, dearseq achieved competitive power while maintaining FDR control across sample sizes [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Analytical Tools for Robust Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Permutation Framework | Empirical FDR estimation | Generating null distributions for evaluating method performance [1] |

| Pseudobulk Analysis | Single-cell data analysis | Aggregating single-cell data to individual level to avoid false positives from cell-level analysis [2] |

| Amended Permutation Scheme | Method validation | Normalizing data before permutation to avoid library size confounders [3] |

| Meta-analysis Methods (SumRank) | Cross-study validation | Identifying DEGs with reproducible signals across multiple datasets [2] |

| Reference Datasets (GTEx, TCGA) | Benchmarking | Providing well-characterized population-level data for method evaluation [1] |

Pathway to Robust Differential Expression Analysis

The relationship between analytical decisions and false positive risk follows a logical pathway that researchers can navigate to improve reproducibility.

The evidence from multiple independent studies confirms a concerning prevalence of inflated Type I error rates in differential expression analysis, particularly affecting popular parametric methods when applied to large population-level datasets. While methodological debates continue regarding optimal permutation schemes and normalization approaches, researchers should approach DE results with appropriate caution, especially from individual studies with limited sample sizes. Incorporating robust non-parametric methods, employing empirical FDR validation through permutation testing, and utilizing meta-analytical approaches across multiple datasets represent the most promising strategies for mitigating the false positive epidemic and enhancing the reproducibility of transcriptomic research.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the study of gene expression patterns within their native tissue context. However, a critical analytical blind spot threatens the validity of findings from many studies: the use of statistical methods that ignore spatial correlations. This guide objectively compares the performance of different differential expression (DE) analysis methods, with a focus on the widely used Wilcoxon rank-sum test in Seurat, and highlights more robust alternatives that account for data structure.

The Analytical Challenge: Spatial Correlation in Transcriptomic Data

In spatial transcriptomics, measurements from nearby locations are typically spatially correlated, violating the fundamental assumption of data independence required by many conventional statistical tests. When analyses fail to account for this structure, they risk producing misleading biological conclusions.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, serving as the default DE method in popular platforms like Seurat, is a non-parametric test that assesses whether two sample sets originate from the same distribution by ranking observations and comparing rank sums [4]. Despite its computational efficiency and simplicity, it fundamentally disregards spatial correlations between nearby spots or cells [4]. This limitation is particularly problematic for ST data where spatial dependencies are inherent, often leading to inflated Type I error rates (false positives) and compromised biological interpretations [4].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Statistical Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Type I Error Control

Extensive simulation studies evaluating statistical methods for DE analysis in ST data reveal critical differences in false positive control.

Table 1: Type I Error Rate Comparison Across Statistical Methods

| Statistical Method | Framework | Spatial Correlation Accounting | Type I Error Control | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test | Non-parametric | No | Inflated | High |

| Generalized Score Test (GST) | Generalized Estimating Equations | Yes, via working correlation matrix | Superior | Moderate |

| Robust Wald Test | Generalized Estimating Equations | Yes, via working correlation matrix | Inflated | Moderate |

| Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) | Mixed Effects | Yes, via random effects | Good (but convergence issues) | Low |

Simulations demonstrate that the Wilcoxon test produces substantial false positives due to spatial correlation, while the GST approach maintains proper error control by appropriately incorporating spatial dependencies [4].

Power and Biological Relevance Assessment

Beyond statistical precision, the biological relevance of identified genes varies significantly between methods.

Table 2: Biological Pathway Enrichment in Breast and Prostate Cancer ST Datasets

| Analysis Method | Cancer-Related Pathway Enrichment | Non-Cancer Pathway Enrichment | Representative Significant Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| GST (SpatialGEE) | High | Low | Pathways directly implicated in cancer progression |

| Wilcoxon Test | Lower | Substantial | Frequently enriched in non-cancer pathways |

Applications to real ST datasets from breast and prostate cancer show that GST-identified differentially expressed genes were enriched in pathways directly implicated in cancer progression, whereas the Wilcoxon test-identified genes were enriched in non-cancer pathways and produced substantial false positives [4]. This highlights how statistically significant results from methods ignoring spatial structure can yield biologically misleading conclusions.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Spatial Differential Expression Analysis

Protocol 1: Generalized Score Test Implementation

The Generalized Score Test within the Generalized Estimating Equations framework provides a robust solution for DE analysis in ST data. The methodology can be implemented using the R package "SpatialGEE" available on GitHub [4].

Key Steps:

- Model Specification: Define the marginal model for gene expression with appropriate link function

- Working Correlation Structure: Specify spatial correlation structure (e.g., exchangeable, autoregressive)

- Parameter Estimation: Estimate parameters under the null hypothesis using iterative algorithms

- Score Test Calculation: Compute the generalized score statistic based on the estimating functions

- Inference: Compare the test statistic to asymptotic distribution for p-value calculation

The primary advantage of GST is that it requires only fitting the null model, which enhances numerical stability and reduces computational burden for genome-wide scans [4].

Protocol 2: Pseudobulk Analysis for Sample-Level Inference

An alternative approach to address correlation structures involves pseudobulk analysis, which aggregates cell-level data to the sample level before DE testing.

Workflow:

- Aggregate Expression: Sum gene counts across all cells from the same sample and cell type using

AggregateExpression()[5] - Create Sample-Level Profiles: Generate one gene expression profile per sample-cell type combination

- DE Analysis with DESeq2: Perform differential expression testing at the sample level using appropriate methods like DESeq2 [5]

This approach treats samples rather than individual cells as independent observations, effectively accounting for within-sample correlation and preventing false positive inflation from pseudo-replication [5].

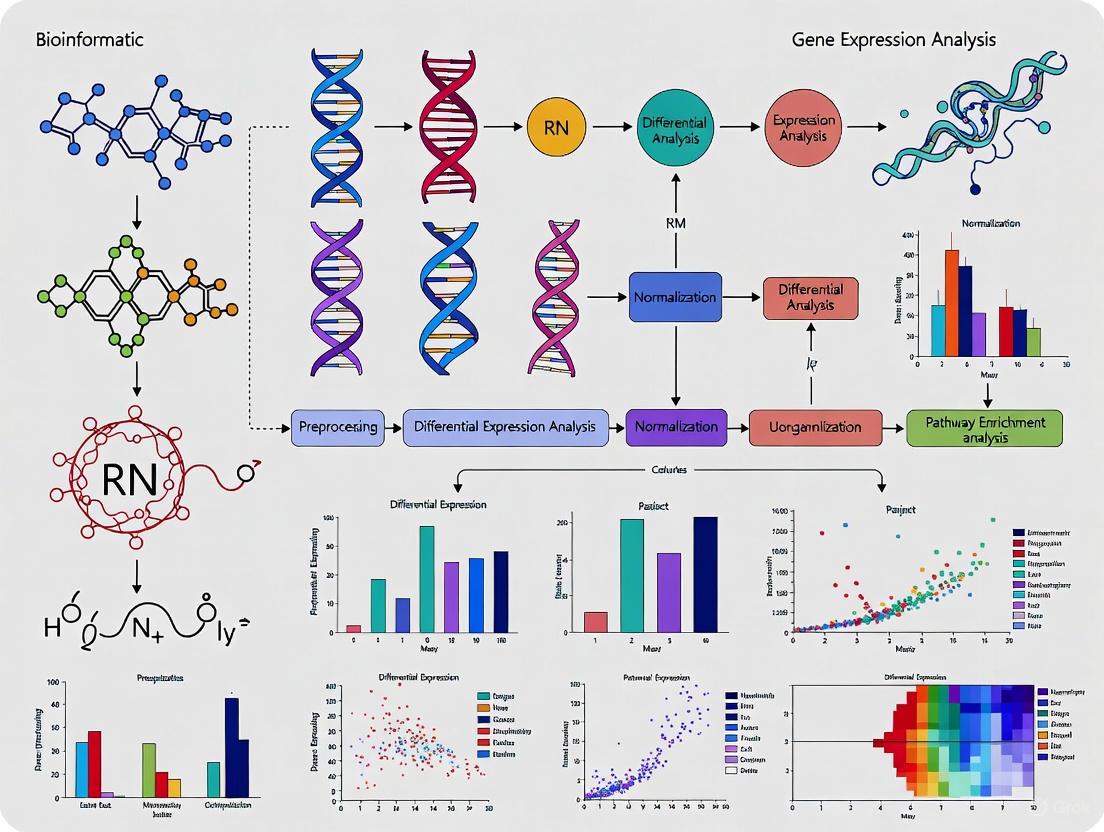

Visualizing Analytical Workflows

Differential Expression Analysis Workflow

Spatial Correlation in ST Data

Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Analytical Tools for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Tool/Package | Function | Spatial Capability | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Comprehensive scRNA/ST analysis | Limited (default Wilcoxon test) | General exploratory analysis |

| SpatialGEE | Differential expression with GEE | Yes (GST implementation) | Formal hypothesis testing |

| Banksy | Spatial clustering incorporating neighborhood | Yes (neighbor-enhanced features) | Spatial domain identification |

| CellCharter | Spatial niche identification | Yes (linear weighting of neighbors) | Microenvironment characterization |

| spatialGE | Integrates statistical and spatial models | Yes (LMM with exponential covariance) | Spatial trend analysis |

Experimental Platform Considerations

Different spatial transcriptomics platforms present unique analytical challenges and opportunities:

- 10x Visium: Spot-based technology requiring specialized normalization approaches to address variance in molecular counts across spots with different cellular densities [6]

- Imaging-based platforms (CosMx, MERFISH, Xenium): Provide single-cell resolution but vary in performance metrics including transcript counts, unique gene detection, and cell segmentation accuracy [7]

- High-resolution technologies (Stereo-seq): DNA nanoball-based sequencing enabling cellular-level mapping of complex tissue architectures [8]

The evidence clearly demonstrates that accounting for spatial correlation is essential for valid differential expression analysis in spatial transcriptomics. While the Wilcoxon rank-sum test offers computational simplicity, its disregard for spatial structure produces inflated false positive rates and biologically misleading results. The Generalized Score Test in the GEE framework provides superior Type I error control while maintaining comparable power, offering a more robust alternative for hypothesis testing in spatially correlated data. As spatial technologies continue to evolve toward higher resolution, adopting analytically appropriate methods that respect data structure will be crucial for extracting biologically meaningful insights from these complex datasets.

The advent of single-cell technologies has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. However, this revolution has introduced a suite of computational challenges collectively termed "The Single-Cell Conundrum." Three interrelated problems dominate this landscape: high data sparsity, the complexity of integrating multimodal measurements, and the pervasive issue of technical zeros. High sparsity arises from the limited starting RNA material in individual cells, resulting in datasets where zeros can exceed 80-95% of values [9]. Technical zeros, distinct from biological absence of expression, stem from stochastic dropout during library preparation where lowly expressed genes fail to be captured [10]. Meanwhile, multimodal assays that simultaneously measure different molecular features (e.g., scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq) from the same cell promise a more comprehensive view of cellular states but demand innovative integration strategies [11]. Within this framework, accurately identifying differentially expressed (DE) genes across conditions or cell types remains a fundamental goal with critical implications for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

Dissecting the Challenges: A Technical Deep Dive

The Tripartite Problem of Zeros in scRNA-seq Data

Zero counts in scRNA-seq data represent a complex mixture of technical and biological signals that most computational methods struggle to disentangle. As highlighted in recent evaluations, zeros can arise from three distinct scenarios: (1) genuine biological zeros, indicating the gene is not expressed in that cell; (2) sampled zeros, where the gene is expressed at low levels but not detected due to sampling limitations; and (3) technical zeros, where the gene is expressed but lost during library preparation due to inefficient cell lysis, reverse transcription, or amplification [12]. The prevailing notion that zeros are primarily technical artifacts has led to widespread use of imputation methods and zero-inflation models, though evidence suggests that cell-type heterogeneity may be the major driver of observed zeros in UMI-based data [12].

The impact of these zeros on differential expression analysis is profound. Methods that explicitly model zero-inflation, such as MAST, can improve performance for certain data types, but may deteriorate under very low sequencing depths where distinguishing biological from technical zeros becomes increasingly difficult [9]. Furthermore, normalization approaches that transform zeros to non-zero values risk introducing artifacts and obscuring true biological signals, particularly for rare cell populations where marker genes may be naturally sparse [12].

Multimodal Integration: Opportunities and Obstacles

Multimodal single-cell technologies provide paired measurements of different molecular layers from the same cell, creating unprecedented opportunities for linking regulatory mechanisms with transcriptional outputs. However, these technologies introduce distinctive computational hurdles. The fundamental challenge lies in reconciling data modalities with markedly different statistical properties—particularly the extreme sparsity of scATAC-seq data (0.2-6% density) compared to scRNA-seq (1-10% density) in multimodal assays [11].

Several strategies have emerged to address these integration challenges. The scMoC framework employs an RNA-guided imputation approach that leverages the richer information in scRNA-seq data to inform the analysis of scATAC-seq data [11]. Alternatively, methods like Liam perform joint representation learning across modalities using a combination of conditional and adversarial training to account for complex batch effects while preserving biological variation [13]. For enhancer-gene mapping, scMultiMap uses a latent-variable model that simultaneously accounts for technical confounding in both gene expression and chromatin accessibility data [14]. Each approach represents a different philosophical stance on whether to integrate data at the imputation, representation, or modeling stage.

Benchmarking Differential Expression Performance

Comprehensive Workflow Evaluation

A landmark benchmarking study evaluated 46 differential expression workflows across diverse experimental conditions, revealing how sparsity, batch effects, and sequencing depth impact performance [9]. The tested workflows combined ten batch effect correction methods (ZINB-WaVE, MNN, scMerge, Seurat, limma_BEC, scVI, scGen, Scanorama, RISC, ComBat) with seven DE methods (DESeq2, edgeR, limma-trend, MAST, Wilcoxon) and three integration approaches (batch-corrected data, covariate modeling, meta-analysis).

Table 1: Top-Performing DE Workflows Under Different Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Recommended Workflows | Performance Metrics | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate depth, large batch effects | MASTCov, ZWedgeR_Cov | High F0.5-score (>0.7) and pAUPR | Covariate modeling slightly deteriorates with small batch effects |

| Low sequencing depth (depth-10) | limmatrend, LogN_FEM, DESeq2 | Maintained F0.5-score >0.6 | ZINB-WaVE weights deteriorate performance |

| Very low depth (depth-4) | RawWilcox, LogNFEM | Relative performance enhanced | Benefit of covariate modeling diminished |

| Multiple batches (7 batches) | MAST_Cov, limmatrend | Stable F0.5-score across batches | Pseudobulk methods perform poorly with large batch effects |

The benchmarking revealed several critical patterns. First, the use of batch-corrected data rarely improved DE analysis compared to covariate modeling approaches, with one exception being scVI combined with limma-trend [9]. Second, covariate modeling generally outperformed other integration strategies for large batch effects but provided diminishing benefits with very low-depth data. Third, methods based on zero-inflation models (e.g., MAST) performed well at moderate depths but deteriorated with extremely sparse data, whereas non-parametric methods like Wilcoxon test showed enhanced relative performance for low-depth data [9].

Normalization: A Critical Choice with Profound Implications

Normalization strategies profoundly impact differential expression results in scRNA-seq analysis, yet the field lacks consensus on optimal approaches [12]. The critical distinction lies in whether protocols use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that enable absolute quantification or produce relative abundance measurements. For UMI-based data, size-factor normalization methods like CPM (counts per million) convert absolute counts to relative abundances, thereby erasing valuable quantitative information and potentially obscuring biological differences between cell types with naturally different RNA content [12].

Table 2: Normalization Methods and Their Impacts on DE Analysis

| Normalization Method | Underlying Principle | Impact on Zeros | Effect on DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw UMI counts | Uses absolute molecule counts | Preserves original zero structure | Maintains biological variation in RNA content |

| CPM/Size-factor | Converts to relative abundance | Preserves zeros but removes quantitative context | May obscure differences between cell types |

| sctransform (VST) | Regularized negative binomial regression | Transforms zeros to negative values | Alters distribution shape, may introduce bias |

| Integrated log-normalization | Batch correction followed by log-transform | Zeros become values near zero | Masks variation across cell types |

Evidence suggests that library-size normalization, while crucial for bulk RNA-seq, may be inappropriate for UMI-based scRNA-seq data [12]. In one analysis of post-menopausal fallopian tube cells, macrophages and secretory epithelial cells exhibited significantly higher raw UMI counts than other cell types, reflecting their biological activity. After integration-based normalization, these biologically meaningful differences were obscured [12]. Similarly, variance-stabilizing transformations like sctransform alter the distribution of zeros by assigning them negative values, potentially complicating downstream interpretation.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Benchmarking Framework for DE Analysis

The comprehensive benchmarking study [9] employed rigorous methodology to evaluate differential expression workflows:

Data Simulation Approach:

- Model-based simulation using splatter R package with negative binomial distribution

- Model-free simulation using real scRNA-seq data to incorporate complex batch effects

- Variation of key parameters: sequencing depth (depth-77, depth-10, depth-4), batch effect size (small/large), and dropout rates

- Inclusion of 20% differentially expressed genes (10% up, 10% down) in simulations

Performance Evaluation Metrics:

- F0.5-score: Emphasizing precision over recall given the need to identify few marker genes from noisy data

- Partial Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (pAUPR): Focusing on recall rates <0.5

- False discovery rates and ranking of known disease genes for real data analyses

- Gene filtering: Removal of genes with zero rates >0.95 before analysis

Workflow Implementation:

- Three integration approaches tested: (1) DE analysis of batch-corrected data, (2) covariate modeling with batch as covariate, and (3) meta-analysis of batch-specific results

- All analyses conducted in balanced study designs where each batch contained both conditions being compared

- Significance threshold set at q-value <0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg correction

Multimodal Integration Assessment

For evaluating multimodal methods like scMoC [11] and scMultiMap [14], distinct experimental protocols were employed:

scMoC Validation Protocol:

- Datasets: sci-CAR (GSE117089), SNARE-seq (GSE126074), and 10X Multiome data

- Preprocessing: Standard Seurat pipeline for scRNA-seq, Latent Semantic Indexing for scATAC-seq

- Imputation: RNA-guided k-nearest neighbors (k=50) using Euclidean distance in PCA space

- Cluster integration: Contingency table approach splitting RNA clusters based on ATAC evidence (>10% and <90% overlap)

scMultiMap Evaluation Framework:

- Statistical foundation: Joint latent-variable model for sparse multimodal counts

- Benchmarking against orthogonal data: Promoter capture Hi-C, HiChIP, PLAC-seq

- Assessment metrics: Type I error control, statistical power, computational efficiency

- Biological validation: Heritability enrichment in disease-relevant cell types (e.g., microglia in Alzheimer's disease)

Visualization of Computational Workflows

Differential Expression Analysis Workflow

Multimodal Data Integration Architecture

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Single-Cell Analysis

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Strength | Applicable Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| scMoC | Multimodal clustering | RNA-guided ATAC imputation | Paired scRNA-seq+scATAC-seq data |

| scMultiMap | Enhancer-gene mapping | Fast moment-based estimation | Cell-type-specific regulatory inference |

| Liam | Multimodal integration | Combined conditional/adversarial training | Complex batch effects in multi-omics |

| DiSC | Differential expression | Joint distributional characteristic testing | Individual-level analysis with multiple replicates |

| GLIMES | Differential expression | Generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed models | Accounting for batch effects and within-sample variation |

| ZINB-WaVE | Zero-inflated modeling | Observation weights for bulk methods | Moderate-depth data with technical zeros |

| MAST with covariate | Differential expression | Zero-inflation modeling with batch covariates | Balanced designs with large batch effects |

| limma-trend | Differential expression | Precision weighting for log-counts | Low-depth data after log-transformation |

The single-cell conundrum represents both a challenge and an opportunity for computational biology. As benchmarking studies reveal, no single method outperforms others across all scenarios—the optimal approach depends critically on experimental factors including sequencing depth, batch effect magnitude, and the specific biological question. For differential expression analysis, covariate modeling generally surpasses analysis of batch-corrected data, particularly for large batch effects [9]. For multimodal integration, methods that leverage the richer modality to inform the sparser one (e.g., RNA-guided ATAC imputation) show particular promise for extracting biological insights from complex data [11]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput and additional modalities, the computational frameworks highlighted in this guide provide a foundation for extracting meaningful biological signals from the pervasive sparsity, technical noise, and complexity that define the single-cell conundrum.

Despite tremendous investment and preclinical success, effective disease-modifying treatments for patients with neurodegenerative diseases have remained elusive. A highly cited reason for this discrepancy is the limited reproducibility of scientific findings, which creates significant gaps between initial discoveries and their validation in independent cohorts [15]. This crisis spans multiple research domains, from genomic analyses to neuroimaging and fluid biomarkers, with rates of non-reproducibility reported as high as 65–89% in pharmacological studies and 64% in psychological studies [16]. In genomic studies specifically, 72% of initially reported genomic associations were found to be over-estimates of the true effect when tested in additional datasets [16]. For neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), this lack of reproducibility directly impedes the development of reliable biomarkers and therapeutic targets, highlighting an urgent need for improved methodological rigor and validation frameworks.

Quantifying the Problem: Evidence Across Modalities

Genomic and Transcriptomic Studies

Table 1: Reproducibility Rates in Transcriptomic Studies of Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Technology | Reproducibility Metric | Rate | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | snRNA-seq (17 studies) | DEGs from one study reproducing in others | <15% | Over 85% of DEGs failed to reproduce in any other study | [2] |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | snRNA-seq (6 studies) | DEGs from one study reproducing in others | Moderate | Improved reproducibility compared to AD, but no gene reproduced in >4 studies | [2] |

| Huntington's Disease (HD) | snRNA-seq (4 studies) | DEGs from one study reproducing in others | Moderate | Better reproducibility than AD, worse than COVID-19 controls | [2] |

| Schizophrenia (SCZ) | snRNA-seq (3 studies) | DEGs from one study reproducing in others | Poor | Very few DEGs independently detected across studies | [2] |

| General RNA-seq | Bulk RNA-seq | Inter-site reproducibility of DEG calls | 60-93% | Varies by analytical tools and filters applied | [17] |

Studies of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) reveal particularly alarming gaps. When examining single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data from 17 studies of Alzheimer's Disease, over 85% of DEGs identified in one individual dataset failed to reproduce in any of the other 16 studies [2]. Fewer than 0.1% of genes were consistently identified as differentially expressed in more than three of the 17 AD studies, and none were reproduced in over six studies [2]. This pattern of non-reproducibility extends to other neuropsychiatric disorders, though with varying severity, suggesting both methodological and biological factors are at play.

Neuroimaging and Fluid Biomarkers

Table 2: Reproducibility in Neuroimaging and Fluid Biomarker Studies

| Modality | Disease | Studies | Reproducibility Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-state fMRI | Parkinson's Disease | 3 independent datasets | PD-related functional connectivity changes were non-reproducible across datasets | [18] |

| Resting-state fMRI | Parkinson's Disease | Classifier training | Classifiers trained on one dataset performed poorly on others (low test accuracy) | [18] |

| Fluid biomarkers | Alzheimer's Disease | Multiple | Many promising biomarker findings fail replication despite initial promising results | [19] |

| Structural MRI | Alzheimer's Disease | 32 CNN model studies | Susceptibility to information leakage; varied performance due to methodological differences | [20] |

The reproducibility challenge extends beyond genomics to neuroimaging, where functional connectivity alterations in Parkinson's Disease have proven non-reproducible across independent datasets [18]. Classifiers trained to discriminate PD patients from controls based on functional connectivity achieved only low accuracies when tested on independent datasets, highlighting limitations in generalizability [18]. Similarly, for fluid biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases, many promising findings have had low reproducibility despite initial promising results, particularly for novel biomarker panels [19].

Root Causes: Technical and Biological Factors

Experimental Design and Analytical Variability

A primary source of non-reproducibility stems from flawed animal study design and reporting in preclinical research [15]. Additionally, in transcriptomic studies, the choice of computational methods significantly impacts results. One evaluation of nine differential expression tools found that widely used methods like edgeR and monocle have worse rediscovery rates (RDR) compared to other methods, especially for top-ranked genes [21]. Performance varies substantially for lowly expressed genes, with some methods being too liberal (poor control of false positives) while others are too conservative (losing sensitivity) [21].

The focus on statistical significance (P-values) rather than effect size or independent verification also contributes to irreproducible findings [16]. This problem is exacerbated by small sample sizes, which typically overestimate effects and performance compared to larger studies [19].

Biological and Cohort-Related Heterogeneity

Neurodegenerative diseases exhibit substantial mechanistic and phenotypic variability [15]. The frequent presence of multiple co-pathologies in clinically diagnosed cases (e.g., combinations of α-synuclein pathology, TDP-43 deposits, and microvascular changes in AD) complicates biomarker associations [19]. This biological heterogeneity means that most models only interrogate individual aspects of complex phenomena, limiting their generalizability.

Cohort-related factors significantly impact reproducibility, including:

- Pre-selection of study participants or extensive inclusion/exclusion criteria [19]

- Systematic differences in recruitment between patients and controls [19]

- Demographic, genetic, and comorbidity factors that may confound associations [19]

- Insufficient accounting for inter-study heterogeneity in meta-analyses [16]

Solutions and Best Practices

Methodological Improvements

Table 3: Strategies to Improve Reproducibility and Their Evidence Base

| Strategy | Application | Effect | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis with random-effects models | Gene expression integration | Improved reproducibility by integrating data from multiple studies | [16] |

| Increasing number of datasets | Gene expression meta-analysis | Increased accuracy even when controlling for sample size | [16] |

| Effect size thresholds | Differential expression analysis | Greater reproducibility with more-stringent effect size thresholds and relaxed significance thresholds | [16] |

| Factor analysis | RNA-seq data preprocessing | Substantially improved empirical False Discovery Rate (eFDR) | [17] |

| SumRank method | scRNA-seq meta-analysis | Substantially outperformed existing methods in sensitivity and specificity of discovered DEGs | [2] |

Gene expression meta-analysis has proven valuable for improving reproducibility by integrating data from multiple studies [16]. Specific methodological choices significantly impact success: random-effects models that account for heterogeneity between studies generally outperform fixed-effects models; including more datasets improves accuracy even when controlling for total sample size; and applying effect size thresholds with relaxed significance thresholds enhances reproducibility [16].

For single-cell transcriptomics, novel methods like SumRank (a non-parametric meta-analysis approach based on reproducibility of relative differential expression ranks across datasets) have demonstrated substantially improved predictive power compared to dataset merging and inverse variance weighted p-value aggregation methods [2].

Rigorous Experimental Design

The adoption of rigorous guidelines for machine learning and biomarker studies is essential for improving reproducibility. For ML in healthcare, these include:

Data Handling Guidelines:

- Data collection/selection should align with the scientific problem, avoiding bias and information leakage [20]

- Detailed description of the entire data handling process to ensure reproducibility [20]

- Data harmonization to compensate for heterogeneous data from different acquisition techniques [20]

Model Design and Assessment Guidelines:

- Public sharing of versioned code to ensure transparency and reproducibility [20]

- Disclosure of samples used in training/testing splits to guarantee benchmarking [20]

- Testing models on external datasets to evaluate generalization properties [20]

For fluid biomarker studies, key considerations include:

- Control of pre-analytical factors (sampling procedures, tube handling) [19]

- Careful attention to assay-related factors (specificity, selectivity, lot-to-lot variability) [19]

- Appropriate statistical methods and proper validation in independent cohorts [19]

- Pre-registration of cohort studies to reduce selective reporting and p-hacking [19]

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Reproducible Differential Expression Analysis

Protocol 1: Meta-analysis of Gene Expression Data

- Systematic search of NIH GEO and ArrayExpress for clinical studies meeting inclusion criteria [16]

- Data download and transformation from public repositories with log2 transformation if not already in log scale [16]

- Gene filtering to include only genes present in all studies for the disease of interest [16]

- Effect size calculation for each probe using corrected Hedges' g [16]

- Probe summarization to genes with a fixed-effects model within each dataset [16]

- Meta-analysis between datasets using random-effects models (e.g., via R package 'metafor') [16]

- Multiple hypothesis correction of P-values to q-values using Benjamini-Hochberg method [16]

- Application of effect size filters (e.g., |log2(F C)|>1) and expression level thresholds [16] [17]

Reproducible Neuroimaging Analysis

Protocol 2: Functional Connectivity Reproducibility Assessment

- Data acquisition of resting-state fMRI scans with consistent parameters across sites [18]

- Preprocessing including motion correction, normalization, and registration to standard space [18]

- Region of interest (ROI) definition using standardized atlases [18]

- Functional connectivity calculation between all ROI pairs [18]

- Comparison with independent datasets processed through identical workflow [18]

- Assessment of reproducibility using random splits of single datasets to distinguish technical vs. biological heterogeneity [18]

- Machine learning validation through training on one dataset and testing on others [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Neurodegeneration Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression Tools | DESeq2, edgeR, limma, MAST, BPSC, DEsingle | Identify statistically differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data | Performance varies substantially; method choice should match data type (bulk vs. single-cell) [21] |

| Meta-analysis Software | metafor, GeneMeta, MetaDE, ExAtlas | Combine results across multiple studies to improve reproducibility | Random-effects models generally preferred for accounting between-study heterogeneity [16] |

| scRNA-seq Analysis Pipelines | SumRank, DESeq2 with pseudo-bulking | Identify cell type-specific transcriptional alterations | SumRank shows improved reproducibility for neurodegenerative diseases compared to standard methods [2] |

| Fluid Biomarker Assays | CSF Aβ42, Aβ42/40 ratio, total-tau, phosphorylated tau, NFL, RT-QuIC | Measure specific protein biomarkers in CSF or blood | Require careful control of pre-analytical factors and lot-to-lot variability [19] |

| Reference Materials | Certified reference materials for CSF Aβ42 | Standardize measurements across laboratories and studies | Not available for most neurodegeneration biomarkers, limiting comparability [19] |

The alarming rates of non-reproducibility in neurodegenerative disease research represent a critical challenge that must be addressed to accelerate therapeutic development. Evidence across genomic, neuroimaging, and biomarker studies consistently shows that findings from individual studies often fail to validate in independent cohorts. This reproducibility crisis stems from multiple factors, including methodological variability, small sample sizes, biological heterogeneity, and analytical choices.

Promising solutions include adopting meta-analytic approaches that prioritize reproducibility across datasets, implementing rigorous experimental design guidelines, and developing novel methods specifically designed to address the unique challenges of neurodegenerative disease research. As the field moves forward, researchers should prioritize cross-study validation from the outset rather than treating it as an afterthought, embrace data sharing and collaborative consortia to increase sample sizes and diversity, and adhere to best practices in statistical analysis and reporting. Only through these concerted efforts can we bridge the cross-study validation gaps that currently impede progress against devastating neurodegenerative diseases.

Next-Generation Statistical Frameworks and Tools for Robust Detection

In the field of spatial transcriptomics and biomedical research, accurately identifying differentially expressed genes is critical for understanding complex biological systems and disease mechanisms. The inherent spatial correlation in data generated from modern technologies violates the fundamental assumption of independence in many statistical tests, leading to inflated false positive rates and compromised biological conclusions [4]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates two methodological approaches within the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) framework for handling spatially correlated data: the commonly used robust Wald test and the Generalized Score Test (GST). Within the broader thesis on accuracy of differential expression detection research, this analysis demonstrates how proper accounting for data correlation structures significantly impacts the reliability and reproducibility of scientific findings in drug development and basic research.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Approaches

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE)

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) represent a semi-parametric method for analyzing longitudinal or clustered data where measurements within the same subject or cluster are correlated [22] [23]. GEE extends generalized linear models (GLMs) to accommodate correlated data through the specification of a "working" correlation matrix, which models the dependence structure between repeated observations within the same cluster [24]. The key advantage of GEE is that it provides consistent parameter estimates even when the correlation structure is misspecified, with the robust sandwich variance estimator accounting for the dependence between observations [22] [23].

The GEE methodology models the marginal expectation of the response variable as a function of covariates, ( g(\mu{ij}) = X{ij}'\beta ), where ( g(.) ) is the link function, ( \mu{ij} ) is the marginal mean of the response ( Y{ij} ) for the ( j )-th measurement of cluster ( i ), ( X{ij} ) is a vector of covariates, and ( \beta ) is the vector of regression coefficients [22]. The variance of ( Y{ij} ) is specified as ( \text{Var}(Y{ij}|X{ij}) = \nu(\mu{ij})\phi ), where ( \nu(.) ) is a known variance function and ( \phi ) is a scale parameter [22]. The working correlation structure ( Ri(\alpha) ) is incorporated into the variance-covariance matrix of responses within each cluster, enabling the GEE to account for within-cluster correlation [22].

Generalized Score Test (GST)

The Generalized Score Test (GST) is a hypothesis testing procedure within the GEE framework that requires fitting only the null model [4]. Unlike the Wald test, which necessitates model fitting under the alternative hypothesis, the GST evaluates whether including additional parameters significantly improves model fit by examining the score function at the null hypothesis [4]. This approach offers enhanced numerical stability and reduced computational burden, making it particularly advantageous for large-scale genomic studies where thousands of tests are performed simultaneously [4].

The GST is based on the score statistic, which is the derivative of the log-likelihood function evaluated at the null parameter values [4]. In the GEE context, the score function is ( U(\beta) = \sum{i=1}^K Di' Vi^{-1} (Yi - \mui) ), where ( Di = \partial \mui / \partial \beta' ) and ( Vi ) is the working variance-covariance matrix [22] [4]. Under the null hypothesis, the properly standardized score statistic follows an asymptotic chi-square distribution, facilitating hypothesis testing without the need to estimate parameters under the alternative hypothesis [4].

Correlation Structures in Spatial Data Analysis

The appropriate specification of correlation structures is fundamental to both GEE and GST applications in spatial data analysis. Several working correlation structures are commonly employed, each with distinct assumptions about the pattern of correlation between observations [22] [24]:

- Independent: Assumes no correlation between observations within the same cluster.

- Exchangeable: Assumes constant correlation between all pairs of observations within a cluster.

- Autoregressive (AR-1): Assumes that correlations decrease with increasing distance or time between measurements.

- Unstructured: Makes no assumptions about the correlation pattern, estimating all pairwise correlations separately.

For spatial transcriptomics data, the correlation structure should reflect the spatial arrangement of measurements, with nearby spots typically exhibiting higher correlation than those farther apart [4].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Type I Error Control

Comprehensive simulation studies comparing GST and GEE with robust Wald tests have demonstrated significant differences in Type I error control when analyzing spatially correlated data [4]. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, commonly used in popular spatial transcriptomics software like Seurat, shows substantial Type I error inflation due to its failure to account for spatial correlations [4]. While GEE with robust Wald tests improves upon the Wilcoxon test, it still exhibits inflated Type I error rates in many scenarios [4]. In contrast, the GST demonstrates superior control of Type I error rates across various correlation structures and sample sizes [4].

Table 1: Type I Error Rates Across Testing Methods (Simulation Results)

| Testing Method | Type I Error Rate | 95% Confidence Interval | Correlation Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Test | 0.118 | (0.103, 0.133) | Independent |

| GEE with Wald Test | 0.072 | (0.060, 0.084) | Exchangeable |

| GST | 0.048 | (0.038, 0.058) | Exchangeable |

| GEE with Wald Test | 0.065 | (0.053, 0.077) | Autoregressive |

| GST | 0.051 | (0.041, 0.061) | Autoregressive |

The simulation results indicate that GST consistently maintains Type I error rates closer to the nominal level (typically 0.05) compared to both the Wilcoxon test and GEE with Wald tests across different correlation structures [4]. This robust error control is particularly valuable in large-scale genomic studies where multiple testing corrections are applied, as inflated false positive rates can lead to numerous spurious findings [4].

Statistical Power

While Type I error control is crucial, the utility of a statistical test also depends on its power to detect true effects. Simulation studies have demonstrated that GST maintains power comparable to GEE with Wald tests while providing superior Type I error control [4]. The power advantage of both GEE-based methods over the Wilcoxon test becomes particularly evident when analyzing data with moderate to strong spatial correlation [4].

Table 2: Statistical Power Comparisons Across Effect Sizes

| Effect Size | Wilcoxon Test | GEE with Wald Test | GST |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| Medium | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| Large | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

Notably, the GST achieves this comparable power with reduced computational burden and enhanced numerical stability, as it requires fitting only the null model rather than both null and alternative models [4]. This characteristic makes GST particularly advantageous in genome-wide scans where computational efficiency is a practical concern [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Simulation Study Design

The comparative performance of GST, GEE with Wald tests, and Wilcoxon tests was evaluated through extensive simulation studies [4]. These simulations were designed to mimic realistic spatial transcriptomics data scenarios with varying correlation structures, sample sizes, and effect sizes [4].

The general workflow for the simulation studies included:

- Data Generation: Simulate spatially correlated gene expression data under various correlation structures (exchangeable, autoregressive) and effect sizes.

- Model Fitting: Apply each testing method (Wilcoxon, GEE with Wald test, GST) to the simulated data.

- Performance Evaluation: Compute Type I error rates (under null scenarios) and statistical power (under alternative scenarios) for each method.

- Comparison: Evaluate methods based on error control, power, computational efficiency, and numerical stability.

For spatial correlation modeling, the simulations incorporated distance-based correlation structures where the correlation between spots decreased with increasing spatial distance [4].

Real Data Application Protocols

The methodological comparison was further validated through applications to real spatial transcriptomics datasets from breast and prostate cancer studies [4]. The analysis workflow for these real data applications included:

- Data Preprocessing: Quality control, normalization, and filtering of spatial transcriptomics data.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Application of Wilcoxon test, GEE with Wald test, and GST to identify differentially expressed genes between tumor and normal tissues.

- Biological Validation: Pathway enrichment analysis of identified genes using databases such as KEGG and GO to assess biological relevance.

- Reproducibility Assessment: Comparison of results across methods and datasets to evaluate consistency.

The real data applications demonstrated that GST-identified differentially expressed genes were enriched in pathways directly implicated in cancer progression, while Wilcoxon test-identified genes showed enrichment in non-cancer pathways and produced substantial false positives [4].

Pathway Diagrams and Workflows

Methodological Decision Pathway

GEE and GST Analytical Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Spatial Transcriptomics Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpatialGEE | R Package | Implements GST for spatial transcriptomics | Available on GitHub [4] |

| geesmv | R Package | Provides modified variance estimators for GEE | Comprehensive small-sample corrections [22] |

| geepack | R Package | General GEE analysis | Model fitting with various correlation structures [23] |

| Seurat | R Package | Spatial transcriptomics analysis platform | Default Wilcoxon test implementation [4] |

| 10x Genomics | Platform | Spatial transcriptomics data generation | Commercial platform for spatial transcriptomics [4] |

| Gaussian Kernel | Statistical Tool | Cumulative density estimation for continuous data | Microarray data transformation [25] |

| Poisson Kernel | Statistical Tool | Cumulative density estimation for count data | RNA-seq data transformation [25] |

The comparative analysis of GEE and GST methods for spatial transcriptomics data reveals important considerations for researchers and drug development professionals. While GEE with robust Wald tests represents a substantial improvement over traditional methods like the Wilcoxon test that ignore spatial correlation, it still exhibits limitations in Type I error control, particularly in small-sample settings [22] [4]. The GST approach addresses these limitations by providing superior control of false positive rates while maintaining comparable power and offering computational advantages through reduced model-fitting requirements [4].

The broader implications for accuracy in differential expression detection research are significant. Proper accounting for spatial correlation structures is not merely a statistical nuance but a fundamental requirement for generating reliable, reproducible findings in spatial transcriptomics studies [4]. The demonstrated inflation of Type I error rates when using methods that ignore spatial correlation explains some of the reproducibility challenges in the literature and highlights the importance of method selection in study design [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between GEE with Wald tests and GST should be guided by specific research contexts. When computational efficiency and numerical stability are priorities, particularly in large-scale genomic scans, GST offers distinct advantages [4]. In cases where parameter estimates and confidence intervals are of primary interest, GEE with bias-corrected variance estimators may be preferable, especially with small sample sizes [22]. Ultimately, both approaches represent substantial improvements over correlation-ignorant methods and contribute to more accurate detection of differentially expressed genes in spatially correlated data.

Differential expression (DE) analysis in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables the dissection of cell-type-specific responses to perturbations such as disease, trauma, or experimental manipulations. While many statistical methods are available to identify differentially expressed genes, the principles that distinguish these methods and their performance remain unclear. A growing body of evidence now demonstrates that pseudobulk methods—which aggregate single-cell data before analysis—consistently outperform approaches that analyze cells as individual observations. This performance advantage stems primarily from the ability of pseudobulk methods to properly account for biological variation between replicates, a fundamental challenge that cell-level models frequently mishandle.

As single-cell technologies mature, enabling large-scale comparisons of cell states within complex tissues, the choice of appropriate statistical methods has become increasingly critical. The unique analytical challenges of scRNA-seq data, including its inherent sparsity and hierarchical correlation structure, necessitate specialized approaches that respect the experimental design. This guide examines the experimental evidence establishing pseudobulk methods as the current gold standard for single-cell differential expression analysis.

Experimental Evidence: Establishing Pseudobulk Superiority

Ground-Truth Benchmarking Against Bulk RNA-Seq

Comprehensive benchmarking against experimentally validated ground truths provides the most compelling evidence for pseudobulk superiority. When researchers curated eighteen 'gold standard' datasets containing matched bulk and scRNA-seq performed on the same population of purified cells, they found that pseudobulk methods demonstrated significantly higher concordance with bulk RNA-seq results, which served as the biological ground truth [26].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DE Methods Against Ground Truth

| Method Category | AUCC (Area Under Concordance Curve) | Bias Toward Highly Expressed Genes | Functional Enrichment Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudobulk Methods | 0.72-0.89 | Minimal | High |

| Single-Cell Methods | 0.45-0.67 | Substantial | Low |

The performance advantage was not merely statistical—pseudobulk methods also more faithfully recapitulated biological insights. In comparisons of Gene Ontology term enrichment analyses, pseudobulk methods consistently mirrored the ground truth established by bulk RNA-seq, while single-cell methods failed to identify relevant biological pathways even in well-characterized systems like mouse phagocytes stimulated with poly(I:C) [26].

Balanced Performance Metrics

Initial concerns that pseudobulk approaches might be "overly conservative" have been addressed by more comprehensive benchmarking using balanced metrics like the Matthews Correlation Coefficient, which considers both type-1 and type-2 error rates. When evaluated using MCC, pseudobulk approaches achieved the highest performance across variations in individual and cell numbers, with performance improving as cell numbers increased [27] [28].

Table 2: Balanced Performance Assessment Using Matthews Correlation Coefficient

| Method Type | 5 Individuals, 50 Cells | 20 Individuals, 200 Cells | 40 Individuals, 500 Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudobulk: Mean | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Pseudobulk: Sum | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.91 |

| Mixed Models | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| Pseudoreplication Methods | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.38 |

Receiver operating characteristics analysis further confirmed that at equivalent type-1 error rates, pseudobulk methods achieve superior sensitivity compared to alternatives, disproving the hypothesis that their conservative nature comes at the cost of reduced power [28].

The Core Mechanism: Accounting for Biological Replicates

The Replicate Variation Problem

The fundamental advantage of pseudobulk methods lies in their proper handling of variation between biological replicates. Single-cell experiments inherently possess a hierarchical structure: cells are nested within samples, and samples are nested within experimental conditions or donors. Cells from the same biological sample are more similar to each other than to cells from different samples due to both technical factors and biological context.

When single-cell methods treat individual cells as independent observations, they commit a pseudoreplication error by ignoring this hierarchical structure. This approach misattributes the inherent variability between replicates to the effect of the perturbation, leading to inflated false discovery rates. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the most widely used single-cell methods can discover hundreds of differentially expressed genes even in the complete absence of biological differences [26] [12].

Visualizing the Analytical Difference

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how single-cell methods versus pseudobulk approaches handle biological replicates:

Systematic Bias Toward Highly Expressed Genes

Single-cell methods exhibit a systematic tendency to identify highly expressed genes as differentially expressed, even when their expression remains unchanged. This bias was conclusively demonstrated using spike-in experiments where synthetic mRNAs were present in equal concentrations across conditions. Single-cell methods incorrectly identified many abundant spike-ins as differentially expressed, while pseudobulk methods avoided this bias [26].

This systematic error explains why the performance gap between pseudobulk and single-cell methods is most pronounced among highly expressed genes, contrary to the initial hypothesis that pseudobulk would show superior performance primarily for lowly expressed genes due to reduced sparsity after aggregation.

Implementation Guide: Pseudobulk Methodologies

Core Pseudobulk Workflow

The pseudobulk approach follows a standardized workflow that can be implemented using various computational tools:

- Subset to Cell Type of Interest: Isolate cells belonging to the specific cell type for differential expression analysis

- Extract Raw Counts: Obtain the raw count matrix after quality control filtering

- Aggregate to Sample Level: Sum counts across all cells of the same type within each biological sample

- Apply Bulk RNA-seq Methods: Perform differential expression analysis using established bulk tools like edgeR, DESeq2, or limma

This workflow effectively converts a single-cell analysis problem into a bulk RNA-seq analysis problem, leveraging decades of methodological development and optimization in bulk transcriptomics [29].

Specialized Extensions: Differential Detection

Beyond conventional differential expression analysis, pseudobulk frameworks can be extended to assess differential detection—differences in the fraction of cells in which a gene is detected between conditions. This approach leverages the observation that the frequency of zero counts captures meaningful biological variability.

By aggregating binarized expression values (expressed/not expressed) to the sample level, researchers can model detection rates using binomial or quasi-binomial generalized linear models. The optimal approach based on benchmarking studies uses edgeR with normalization offsets and filtering of ubiquitously detected genes, providing complementary biological insights to conventional differential expression analysis [30] [31].

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Methods

Addressing the "Four Curses" of Single-Cell DE Analysis

Recent research has identified four major challenges—termed the "four curses"—in single-cell differential expression analysis:

- Excessive Zeros: The high proportion of zero counts in scRNA-seq data

- Normalization Challenges: Appropriate correction for technical variation

- Donor Effects: Biological variation between replicates

- Cumulative Biases: The compounding effect of multiple preprocessing steps

Pseudobulk methods naturally address these challenges by reducing zeros through aggregation, using established normalization strategies from bulk RNA-seq, explicitly modeling donor effects through the experimental design, and minimizing cumulative preprocessing biases [12].

Emerging Statistical Innovations

While pseudobulk methods represent the current gold standard, statistical innovation continues. Newer approaches like GLIMES leverage UMI counts and zero proportions within generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed-effects models to account for batch effects and within-sample variation while preserving absolute RNA expression rather than converting to relative abundance [12].

Another emerging method, scDETECT, implements a Bayesian hierarchical model to incorporate correlations in differential expression states across related cell types, potentially improving accuracy and statistical power, particularly for low-abundance cell types [32].

These specialized methods may offer advantages in specific experimental contexts but require further benchmarking against established pseudobulk approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Pseudobulk Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Negative binomial generalized linear models | Primary workhorse for pseudobulk DE analysis |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial modeling with variance stabilization | Alternative to edgeR with different normalization |

| limma-voom | Linear modeling of log-counts with precision weights | Particularly effective for large sample sizes |

| SingleCellExperiment | Data container for single-cell data | Standardized object for organizing count matrices and metadata |

| Seurat | Single-cell analysis toolkit | Preprocessing, clustering, and cell type identification |

| muscat | Multi-sample multi-condition analysis toolkit | Specialized implementation of pseudobulk DD and DE workflows |

The collective evidence from benchmarking studies establishes pseudobulk methods as the current gold standard for differential expression analysis in single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Their superior performance stems from the principled handling of biological replicates, avoidance of pseudoreplication bias, and reduced false discoveries.

For researchers designing single-cell studies, we recommend:

- Incorporate Multiple Biological Replicates in experimental designs

- Implement Pseudobulk Workflows as the primary analysis strategy

- Consider Differential Detection as a complementary analysis to uncover additional biological insights

- Leverage Established Bulk RNA-seq Tools like edgeR and DESeq2 for the analytical component

The pseudobulk paradigm represents a fundamental principle in single-cell bioinformatics: respecting the hierarchical structure of multi-sample experimental data is not merely a statistical technicality but a prerequisite for biologically accurate inference.

Differential expression (DE) analysis in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is pivotal for identifying cell-type-specific responses to disease, treatment, and other biological stimuli. However, the pervasive issue of zero-inflation—where a high proportion of genes show zero counts—has long plagued analytical workflows, compromising accuracy and biological interpretability [33] [34]. These zeros arise from a complex mixture of biological phenomena (e.g., genuine absence of transcripts) and technical artifacts (e.g., inefficient mRNA capture or limited sequencing depth), creating fundamental challenges for statistical modeling [34]. Within this context, a new generation of computational frameworks is emerging, with GLIMES (Generalized Poisson/Binomial Mixed-Effects Model) representing a significant paradigm shift that directly addresses the major shortcomings of existing methods [33].

GLIMES: A Novel Framework for Zero-Inflated Data

Conceptual Foundation and Methodology

GLIMES is a statistical framework designed to overcome the four major "curses" of single-cell DE analysis: excessive zeros, normalization challenges, donor effects, and cumulative biases [33]. Its methodological innovation lies in leveraging UMI counts and zero proportions within a unified model, thereby treating zeros as potentially informative biological signals rather than mere noise to be corrected.

Unlike methods that rely on relative abundance measures (e.g., CPM), GLIMES uses absolute RNA expression quantified by UMIs. This approach preserves quantitative biological information that is often lost during normalization. The framework incorporates generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed-effects models to account for both batch effects and within-sample (donor) variation simultaneously, addressing the critical issue of pseudoreplication that inflates false discovery rates in many conventional tests [33] [35].

Comparative Performance Against Established Methods

Rigorous benchmarking against six existing DE methods across three case studies and simulation scenarios demonstrates GLIMES's superior adaptability to diverse experimental designs [33]. The framework demonstrates particular strength in:

- Improved Sensitivity: Better detection of true differentially expressed genes, especially those with low expression levels.

- Reduced False Discoveries: More accurate control of false positive rates through proper modeling of biological and technical variability.

- Enhanced Biological Interpretability: Preservation of biologically meaningful signals often obscured by aggressive normalization or imputation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GLIMES Against Established DE Methods

| Method | Underlying Model | Handling of Zeros | Account for Donor Effects | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLIMES | Generalized Poisson/Binomial Mixed-Effects | Leverages zero proportions as information | Yes (via mixed effects) | Adaptability to diverse designs, uses absolute expression |

| MAST | Hurdle model | Explicitly models as technical dropouts | Can include random effects | Two-part model for zero inflation |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial | Not specifically modeled | No (fixed effects only) | Established robustness for bulk RNA-seq |

| Wilcoxon Test | Non-parametric rank-based | Ignores mechanism | No | Simple, fast execution |

| scVI | Deep generative model | Implicitly handled by latent representation | Can be incorporated in latent space | Handles complex batch effects |

| Pseudobulk | Various (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) | Aggregates across cells | Yes (by design) | Avoids pseudoreplication |

Benchmarking Insights: GLIMES in Context

Large-Scale Benchmarking Evidence

Comprehensive benchmarking studies provide context for evaluating GLIMES's performance claims. An analysis of 46 DE workflows revealed that batch effects, sequencing depth, and data sparsity substantially impact method performance [9]. Key findings include:

- Batch Effect Management: Covariate modeling (including batch as a covariate) generally improves DE analysis for substantial batch effects, whereas using pre-corrected data rarely helps [9].

- Sequencing Depth Considerations: For low-depth data, methods based on zero-inflation models often deteriorate in performance, while methods like limmatrend, Wilcoxon test, and fixed effects models perform better [9].

- Pseudobulk Approaches: While pseudobulk methods (aggregating counts per sample) perform well for small batch effects, they show the worst performance for large batch effects [9].

Table 2: Method Performance Across Experimental Conditions Based on Large-Scale Benchmarking

| Method Category | Substantial Batch Effects | Small Batch Effects | Low Sequencing Depth | High Data Sparsity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate Modeling | Excellent | Good | Good (benefit diminishes at very low depth) | Good |

| Naïve DE (no batch adjustment) | Poor | Good | Varies by method | Varies by method |

| Batch-Corrected Data | Rarely improves analysis | Rarely improves analysis | Not recommended | Not recommended |

| Zero-Inflation Models | Variable | Variable | Poor | Designed for this but performance varies |

| Pseudobulk Methods | Poor | Excellent | Good | Good with sufficient cells per sample |

The Zero-Inflation Controversy

The fundamental assumption underlying GLIMES—that zeros contain biological information—aligns with growing evidence challenging conventional zero-inflation modeling. Research across 20 spatial transcriptomics datasets found that "modeling zero inflation is not necessary," as simple count models often suffice when biological heterogeneity is properly accounted for [36]. Similarly, in UMI-based scRNA-seq protocols, evidence suggests that cell-type heterogeneity is a major driver of observed zeros rather than technical dropouts [33] [36].

This paradigm shift suggests that methods aggressively "correcting" for zeros through imputation or specialized inflation models may inadvertently remove biological signal. GLIMES's approach of leveraging zero proportions while maintaining absolute expression measurements positions it favorably within this evolving understanding.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Benchmarking

Benchmarking Design Principles

The experimental protocols supporting GLIMES development and evaluation follow rigorous principles essential for meaningful method comparison:

- Multi-Faceted Validation: Performance assessed through both simulated data with known ground truth and real biological datasets with established markers [33].

- Diverse Scenario Testing: Evaluation across different experimental conditions including comparisons across cell types, tissue regions, and cell states [33].

- Comprehensive Metric Selection: Assessment using multiple complementary metrics including F-scores, area under precision-recall curve (AUPR), false discovery rates, and rank of known disease genes [9] [33].

Implementation of Model Comparisons

In benchmark studies, methods are typically evaluated using the following standardized approach:

- Data Preprocessing: Filtering of sparsely expressed genes (e.g., zero rate > 0.95) to remove uninformative features [9].

- Model Fitting: Each method is applied according to its recommended workflow, with appropriate normalization and parameter settings.

- Statistical Testing: DE genes are identified using a significance threshold (e.g., q-value < 0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction) [9].

- Performance Quantification: For simulated data, precision-recall metrics and F-scores are calculated; for real data, enrichment of known markers or prognostic genes is assessed [9].

Visualizing the GLIMES Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and logical structure of the GLIMES framework for differential expression analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Single-Cell Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLIMES | R package | Differential expression testing | Handling zero-inflated data with complex experimental designs |

| scvi-tools | Python library | Probabilistic modeling, DE analysis | Large-scale data integration, reference-based analysis [37] |

| DESeq2 | R package | General purpose DE testing | Pseudobulk approaches, established methodology [35] |

| MAST | R package | Zero-inflated DE analysis | Modeling technical zeros explicitly [9] [35] |

| Seurat | R package | Single-cell analysis toolkit | Data integration, visualization, and general analysis [9] |