Beyond the Template: Advanced Strategies for Improving AI Model Quality in Data-Scarce Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on improving the quality of artificial intelligence and machine learning models in scenarios where high-quality, labeled training...

Beyond the Template: Advanced Strategies for Improving AI Model Quality in Data-Scarce Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on improving the quality of artificial intelligence and machine learning models in scenarios where high-quality, labeled training data or established templates are unavailable. It covers the foundational challenges of template-independent development, explores methodological approaches like training-free models and unsupervised learning, details optimization and troubleshooting techniques for real-world performance, and establishes robust validation frameworks. The content synthesizes current trends and proven techniques to empower professionals in building reliable, high-quality models that accelerate discovery and enhance clinical applications.

The Core Challenge: Understanding Model Development Without Templates or Perfect Data

Defining 'Template-Unavailable' Scenarios in Biomedical Research

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What defines a 'Template-Unavailable' scenario in structural biology? A 'Template-Unavailable' scenario occurs when a researcher aims to determine the three-dimensional structure of a target protein but cannot find a suitable homologous protein structure in databases like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to use as a template for modeling. This is common for proteins with novel folds or unique sequences lacking evolutionary relatives of known structure.

Q2: What are the primary computational symptoms of this problem?

- Low Sequence Identity: A failure to find templates with sequence identity above the "twilight zone" (typically 20-30%) via tools like BLAST or HHblits.

- Poor Template Coverage: The best available templates cover only a small fraction of your target protein's sequence.

- Low Confidence Scores: Ab initio modeling software reports low confidence scores (e.g., a predicted TM-score below 0.5) for the generated models.

Q3: What key experimental data can compensate for the lack of a template? Several experimental biophysical and structural techniques can provide crucial restraints for modeling, as summarized in the table below.

Table: Key Experimental Data for Template-Unavailable Scenarios

| Data Type | Key Function in Modeling | Required Sample/Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) Maps | Provides a low-resolution 3D density envelope to guide and validate model building. | Purified protein complex in vitreous ice. |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Yields low-resolution structural parameters (e.g., overall shape, radius of gyration). | Monodisperse protein solution. |

| Chemical Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) | Identifies spatially proximal amino acids, providing distance restraints. | Cross-linked protein, Mass Spectrometer. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Can provide inter-atomic distances and dihedral angle restraints for structure calculation. | Isotopically labeled (e.g., 15N, 13C) protein. |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange MS (HDX-MS) | Informs on solvent accessibility and protein dynamics, aiding in domain placement. | Protein in buffered solution, Mass Spectrometer. |

Q4: My ab initio model has a poor global structure but I suspect a local region is correct. How can I validate this? Focus on local quality estimation. Use tools like MolProbity to check the local geometry (e.g., Ramachandran plot, rotamer outliers) of the region of interest. Additionally, see if the predicted local alignment matches with any experimental data you have, such as a peak in your HDX-MS data that corresponds to a protected helix in your model.

Q5: Our template-free model contradicts a key functional hypothesis. What are the next steps?

- Statistical Validation: Rigorously check the model's statistical significance using Z-scores in programs like ROSETTA.

- Design a Crucial Experiment: Formulate a functional assay that can definitively test the prediction made by your model. For example, if the model suggests a specific residue is critical for a protein-protein interaction, perform a site-directed mutagenesis experiment to test this.

- Iterate: Use the new functional data as a constraint to refine your computational models.

▼ Experimental Protocol: Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Template-Free Modeling

1. Objective To construct a computationally rigorous 3D model of a target protein in the absence of homologous templates by integrating ab initio prediction with experimental restraints.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Protein Purification System: FPLC, SDS-PAGE gels, size-exclusion columns.

- Biophysical Assay Kits: For SEC-MALS, fluorescence-based thermal shift assays.

- Cross-linking Reagent: DSSO or DSBU.

- Computational Software Suite:

- Ab initio Prediction: ROSETTA, I-TASSER, or AlphaFold2 (in its ab initio mode).

- Model Refinement: GROMACS or NAMD for molecular dynamics simulation.

- Validation: MolProbity, SAVES v6.0 server.

3. Step-by-Step Methodology Phase 1: Initial Computational Modeling & Quality Assessment

- Step 1.1 (Sequence Analysis): Run PSI-BLAST and HHblits against the PDB. Confirm the absence of suitable templates (sequence identity <25%).

- Step 1.2 (Ab Initio Modeling): Generate an ensemble of 10,000-50,000 decoy structures using ROSETTA's abinitio application or a similar tool.

- Step 1.3 (Cluster Analysis): Cluster the generated decoys using a metric like RMSD. Select the top 5 centroid models from the largest clusters for initial analysis.

Phase 2: Generation of Experimental Restraints

- Step 2.1 (Sample Preparation): Express and purify the target protein to >95% homogeneity. Validate monodispersity via SEC-MALS.

- Step 2.2 (Cross-linking MS): Incubate the purified protein with DSSO cross-linker. Quench the reaction, digest with trypsin, and analyze the peptides via LC-MS/MS. Identify cross-linked residue pairs using software like XlinkX or pLink.

- Step 2.3 (SAXS Data Collection): Collect SAXS data on the purified protein at multiple concentrations. Process data to obtain the pair-distance distribution function and molecular envelope.

Phase 3: Integrative Modeling and Refinement

- Step 3.1 (Restraint-Driven Modeling): Feed the distance restraints from XL-MS and the shape information from SAXS back into the computational modeling pipeline (e.g., using ROSETTA's relax protocol with constraints). Generate a new, smaller ensemble of models that satisfy the experimental data.

- Step 3.2 (Molecular Dynamics): Subject the best-scoring model(s) to a short, restrained molecular dynamics simulation in explicit solvent (e.g., using GROMACS) to relax the structure and remove steric clashes.

Phase 4: Rigorous Model Validation

- Step 4.1 (Geometric Quality): Analyze the final model using MolProbity. A high-quality model should have over 90% of residues in the favored region of the Ramachandran plot and fewer than 1% rotamer outliers.

- Step 4.2 (Restraint Satisfaction): Verify that the final model satisfies >85% of the experimental cross-links (allowing for a small distance threshold).

- Step 4.3 (Statistical Z-score): Calculate the model's energy Z-score relative to the decoys generated in Phase 1. A reliable model typically has a Z-score below -2.

▼ Experimental Workflow for Template-Unavailable Modeling

▼ The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Software for Template-Unavailable Research

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| DSSO (Disuccinimidyl sulfoxide) | A mass-spectrometry cleavable cross-linker used in XL-MS to identify spatially proximate lysine residues in proteins, providing crucial distance restraints for modeling. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns (e.g., Superdex 200) | For purifying the target protein and assessing its oligomeric state and monodispersity, which is critical for obtaining quality SAXS and XL-MS data. |

| ROSETTA Software Suite | A comprehensive software platform for macromolecular modeling, used for ab initio structure prediction, model refinement with experimental restraints, and quality assessment. |

| MolProbity Web Service | A structure-validation tool that analyzes protein models for steric clashes, Ramachandran plot outliers, and rotamer irregularities, providing a global quality score. |

| GROMACS | A molecular dynamics simulation package used to refine protein models in a solvated environment, relaxing steric strain and improving local geometry. |

For researchers and drug development professionals, high-quality, abundant data is the cornerstone of building reliable AI models. In real-world research, particularly when established templates or pre-existing models are unavailable, a frequent and significant obstacle is data scarcity—the lack of sufficient, high-quality annotated data needed to train effective AI systems [1] [2]. This technical support guide provides actionable methodologies and solutions to overcome these challenges and improve model quality under constrained conditions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Insufficient Labeled Data for Model Training

This occurs when there are too few annotated examples to train a generalizable model, leading to poor performance on unseen data.

Methodology 1: Synthetic Data Generation using LLMs

This approach uses Large Language Models (LLMs) to artificially create a larger, more diverse training dataset from a small set of high-quality seed annotations [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Seed Collection: Manually annotate a small, high-quality dataset of dataset mentions from research literature. This is your seed data [1].

- LLM Prompting: Use a carefully designed prompt with the seed data to instruct an LLM to generate new, synthetic dataset mentions that mirror the diverse styles found in real research (e.g., full names, acronyms, descriptive terms) [1].

- Validation: Establish criteria to validate the synthetic data for quality and relevance. This often involves automated checks or human review to filter out invalid examples [1].

- Model Training: Combine the original seed data with the validated synthetic data to train your AI model (e.g., for named entity recognition or citation tracking) [1].

- Generalization Check: Encode the full research corpus and your training data into a shared embedding space. Identify clusters in the research landscape that are not covered by your training data ("out-of-domain gaps") and use them to test and further refine your model [1].

Visualization: Synthetic Data Expansion Workflow

Methodology 2: Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)

MIDD employs quantitative models to maximize information gain from limited data, reducing the need for large, costly clinical trials [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Problem Formulation: Define the key development question (e.g., determining optimal dosage, waiving a clinical study).

- Model Selection: Choose the appropriate quantitative model:

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: Simulates drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion to predict drug-drug interactions or the impact of organ impairment [3].

- Population PK/PD Modeling: Analyzes the variability in drug exposure (Pharmacokinetics, PK) and response (Pharmacodynamics, PD) within a target population [3].

- Exposure-Response Analysis: Characterizes the relationship between drug exposure levels and their efficacy or safety outcomes [3].

- Data Integration: Integrate all available data (preclinical, early-phase clinical, literature) to inform and build the model.

- Simulation & Decision Making: Run simulations to predict outcomes under different scenarios. Use these insights to support decisions like granting a trial waiver, optimizing study design, or making a "No-Go" decision [3].

- Validation & Regulatory Submission: Where possible, validate model predictions with subsequent data. The model and analysis can be included in regulatory submissions to support labeling [3].

Quantitative Impact of MIDD: The table below summarizes the average savings per program from the systematic application of MIDD across a portfolio.

| Metric | Reported Average Savings per Program | Primary Sources of Savings |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle Time | ~10 months | Waivers of clinical trials (e.g., Phase I studies), sample size reductions, earlier "No-Go" decisions [3] |

| Cost | ~$5 million | Reduced clinical trial costs from waivers, smaller sample sizes, and avoided studies [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main causes of data scarcity in AI for drug development? Data scarcity arises from the high cost and complexity of generating high-quality experimental and clinical data. Annotations for specific tasks (like labeling dataset mentions in scientific papers) are also rare because manual annotation is not scalable and cannot cover the full diversity of real-world data variations [1].

Q2: How can I validate that my model, trained with synthetic data, generalizes well to real-world data? Use embedding space analysis. Map both your training data (synthetic and real) and a broad corpus of research literature into a shared vector space. Cluster this space to identify themes or topics. If you find clusters with no training examples, these are your "out-of-domain" gaps. Testing your model's performance on these exclusive clusters provides evidence of its generalization capability [1].

Q3: Beyond synthetic data, what other techniques can help with limited data? Advanced machine learning techniques like transfer learning (adapting a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset to your specific task) and few-shot learning (training models to learn new concepts from very few examples) are promising approaches for low-resource settings [2].

Q4: Can you provide an example of a MIDD approach directly saving resources? Yes. A PBPK model can sometimes be used to support a waiver for a dedicated clinical drug-drug interaction (DDI) trial. By simulating the interaction, a company can avoid the time and cost of conducting the actual study. One analysis found that MIDD approaches led to waivers for various Phase I studies (e.g., DDI, hepatic impairment), saving an estimated 9-18 months and $0.4-$2 million per waived study [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key methodological "reagents" for combating data scarcity.

| Solution | Function | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data (LLM-generated) | Expands small, annotated datasets by generating diverse, realistic examples to improve model robustness and coverage [1]. | Training AI models for tasks like tracking dataset usage in scientific literature or any NLP task with limited labeled examples. |

| PBPK Modeling | A computational framework that simulates the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of a drug based on physiology. Predicts PK in specific populations or under specific conditions (e.g., organ impairment, DDI) [3]. | To inform dosing strategies, support clinical trial waivers, and assess the risk of drug interactions without always requiring a new clinical study. |

| Population PK/PD Modeling | Quantifies and explains the variability in drug exposure and response within a patient population. Identifies factors (e.g., weight, renal function) that influence drug behavior [3]. | To optimize trial designs, identify sub-populations that may need different dosing, and support dosing recommendations in drug labels. |

| Exposure-Response Analysis | Characterizes the mathematical relationship between the level of drug exposure (e.g., concentration) and a desired or adverse effect. Determines the therapeutic window [3]. | To justify dosing regimens, define therapeutic drug monitoring strategies, and support benefit-risk assessments. |

Establishing a Cyclical Development Process for Robust AI Tools

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the absence of pre-defined templates for AI models presents a significant challenge to ensuring reproducible, high-quality outcomes. A disciplined, cyclical development process is not merely a best practice but a foundational requirement for building robust AI tools. This process mitigates risks such as model bias, performance degradation, and non-reproducible results, which are critical in sensitive fields like drug development.

The AI development life cycle provides a structured framework that guides projects from problem definition through to deployment and ongoing maintenance [4] [5]. By adopting this cyclical approach, research teams can systematically address the unique complexities of AI projects, including data quality issues, computational constraints, and evolving stakeholder requirements. This article establishes a technical support framework to navigate this process, providing troubleshooting guides and FAQs specifically tailored for research environments where standardized templates are unavailable.

The AI Development Life Cycle: A Research Framework

The AI development life cycle is a sequential yet iterative progression of tasks and decisions that drive the development and deployment of AI solutions [4]. For research scientists, this framework ensures that AI tools are built efficiently, ethically, and to a high standard of reliability.

Phases of the AI Life Cycle

A comprehensive understanding of the AI life cycle is crucial for efficiency, cost optimization, and risk mitigation [5]. The following phases form a robust framework for research projects:

- Problem Definition and Scoping: This initial phase involves defining the problem to be solved or the opportunity to be explored using AI. It sets the direction for the entire project and requires establishing clear, measurable objectives and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that align with research goals [4] [5].

- Data Acquisition and Preparation: AI and machine learning algorithms require high-quality data to learn. This stage involves gathering relevant data from reliable sources and preparing it through cleaning, dealing with missing values, and transformation into a format suitable for the chosen models. This is often the most time-consuming phase of the AI life cycle [4] [5].

- Model Design and Selection: This phase involves selecting and developing the AI model that will solve the defined problem. The choice of algorithm depends on the problem type, and researchers must balance model accuracy with computational performance and interpretability [5].

- Model Training and Testing: The selected model is trained with the prepared data. This stage is iterative, involving multiple rounds of development and refinement. The model must be evaluated on unseen data using appropriate metrics to ensure it performs satisfactorily [4] [5].

- Deployment and Integration: Once the model meets performance benchmarks, it is deployed into a production or research environment where it can start solving real-world problems. This involves integrating the model with existing systems and workflows [4] [5].

- Maintenance and Iteration: After deployment, the model requires ongoing maintenance and monitoring. This includes updating the model with new data, refining it based on user feedback, and handling performance degradation or "model drift" to ensure it continues to function as expected over time [4] [5].

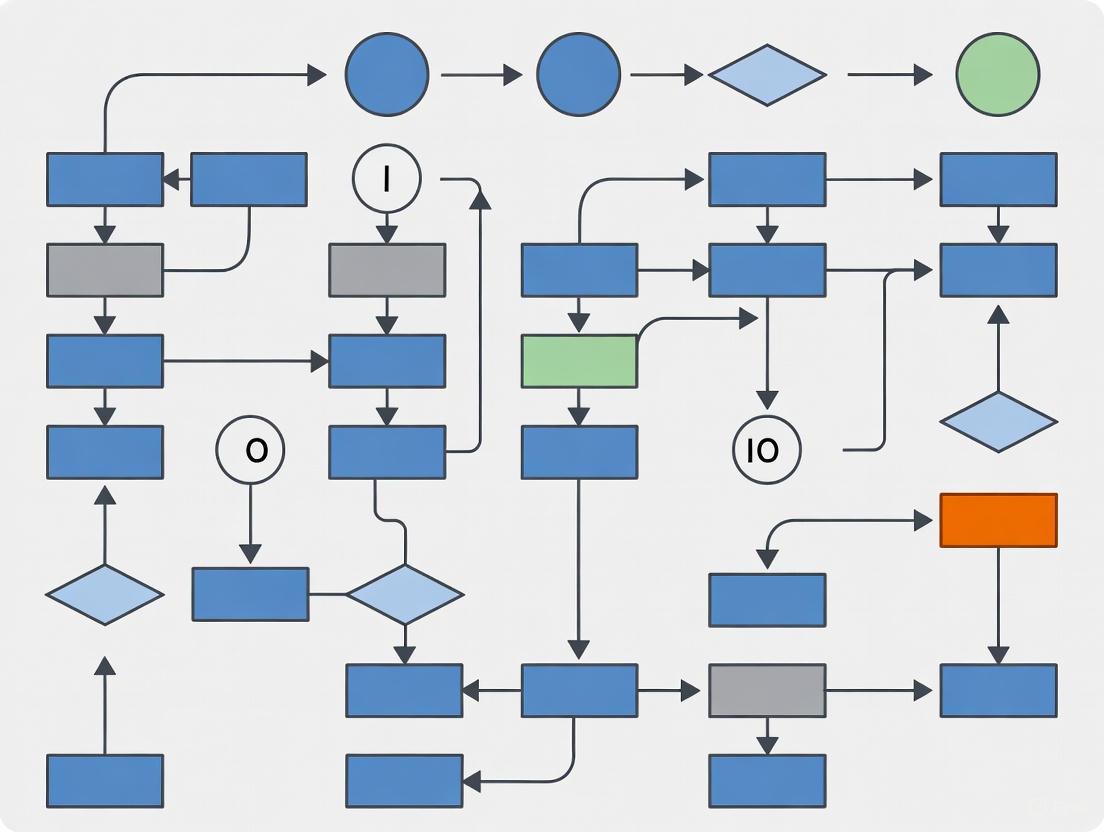

The following diagram illustrates the cyclical nature and key interactions of this process:

Key Considerations for Research-Grade AI

When implementing this life cycle in a research context, several considerations are paramount:

- Ethical AI Development: Regularly conduct fairness audits and employ explainability tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) to ensure transparency and mitigate bias, which is critical in drug development and healthcare applications [5].

- Regulatory Compliance: Adhere to relevant global standards (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) and establish robust data governance policies to maintain data integrity and compliance throughout the AI lifecycle [5].

- Cross-Functional Collaboration: Foster communication between business leaders, data scientists, domain experts, and end-users. This ensures technical solutions align with research objectives and real-world constraints [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential AI Research Reagents

Selecting the appropriate tools is crucial for successfully implementing the AI development life cycle. The following table summarizes key categories of AI research tools and their specific functions in the context of scientific research.

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Literature Review & Discovery | Semantic Scholar, Elicit, Litmaps [6] [7] | AI-powered paper discovery, summarization, and visualization of research connections and citation networks. |

| Writing & Proofreading | thesify, Grammarly, Paperpal [6] [7] | Provides structured feedback on academic writing, corrects grammar, improves clarity, and ensures an academic tone. |

| Citation & Reference Management | Zotero, Scite_ [6] | Organizes and manages research citations, provides context-rich "Smart Citations" indicating if work has been supported or contrasted. |

| All-in-One Research Assistants | Paperguide, SciSpace [7] | Platforms covering multiple research stages: semantic search, literature review automation, data extraction, and AI-assisted writing. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common AI Research Challenges

This guide provides a structured approach to identifying, diagnosing, and resolving common problems encountered during AI development for research [8].

Preparation Steps

Before beginning troubleshooting, ensure you have:

- Defined Clear Objectives: A well-defined problem statement and KPIs aligned with research goals [5].

- Established Data Governance: Protocols for data quality, integrity, and privacy [5].

- Secured Computational Resources: Access to adequate computational power (e.g., cloud platforms like AWS or Google Cloud) for model training and experimentation [5].

Problem Identification and Common Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Preparation | Model fails to converge; Poor performance on validation set; High error rates. | Inconsistent, missing, or unrepresentative data; Data leakage between training/test sets [5]. | Implement robust data cleaning protocols; Use synthetic data generation to overcome scarcity; Perform rigorous train/validation/test splits [5]. |

| Model Performance | Overfitting: Excellent train accuracy, poor test accuracy. Underfitting: Poor performance on both train and test sets [5]. | Overfitting: Model too complex, trained on noisy data. Underfitting: Model too simple for data complexity [5]. | Apply regularization techniques (L1/L2); Use cross-validation; Simplify/model complexity; Gather more relevant features [5]. |

| Deployment & Integration | Model performs well offline but degrades in production; Latency issues in real-time applications [5]. | Model drift due to changing data distributions; Integration errors with existing systems; Insufficient computational resources [5]. | Implement continuous monitoring for performance degradation; Retrain models periodically with new data; Use scalable deployment tools (e.g., Docker, Kubernetes) [5]. |

| Ethical & Compliance Risks | Model exhibits biased behavior against specific subpopulations; Failure to pass regulatory audits [5]. | Biased training data; Lack of model transparency and explainability; Non-compliance with data privacy regulations [5]. | Conduct regular fairness audits on diverse datasets; Employ Explainable AI (XAI) techniques; Anonymize sensitive data and adhere to GDPR/HIPAA [5]. |

Advanced Diagnostic Tools and Techniques

For complex issues that persist after applying basic solutions, consider these advanced approaches:

- Explainable AI (XAI): Use tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to interpret model predictions and identify features contributing to errors or bias [5].

- Automated Model Monitoring: Implement systems to automatically track model performance metrics and data distributions in production to quickly detect and alert on model drift [5].

- Cross-Functional Review: Engage domain experts, data scientists, and end-users in a collaborative review to identify gaps between technical implementation and research needs that may be causing performance issues [5].

Reporting Unresolved Issues

If an issue cannot be resolved using this guide, escalate it by providing the following information to specialized support or your research team:

- A clear description of the expected vs. observed behavior.

- The specific AI life cycle phase where the problem occurs.

- All steps already taken to diagnose and resolve the issue.

- Relevant code snippets, data samples, and model performance logs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we effectively manage the iterative nature of the AI life cycle, especially when research goals evolve? Adopt agile practices by breaking projects into manageable phases and incorporating iterative feedback from real-world data and stakeholders [5]. Use tools like Jira or Trello to streamline collaboration and track iterations. The cyclical nature of the life cycle is a strength, allowing you to refine models and objectives as your research deepens [4].

Q2: Our model performance is degrading in production. What is the most likely cause and how can we address it? The most common cause is model drift, where the statistical properties of the live data change over time compared to the training data [5]. Address this by implementing a continuous monitoring system to track performance metrics and data distributions. Establish a retraining pipeline to periodically update models with new data to maintain relevance and accuracy [5].

Q3: Which AI tools are most critical for establishing a rigorous literature review process when starting a new drug discovery project? Tools like Semantic Scholar and Litmaps are invaluable for discovery, helping you visualize research landscapes and identify foundational papers [6] [7]. For deeper analysis and synthesis, Scite_ provides context-rich citations, showing you how a paper has been supported or contrasted by subsequent research, which is crucial for assessing scientific claims [6].

Q4: How can we ensure our AI model is ethically sound and compliant with regulations in clinical research? Embed ethical considerations from the start. Conduct regular fairness audits using diverse datasets and employ explainability tools (XAI) to ensure transparency [5]. For compliance, adhere to industry-specific regulations like HIPAA by implementing robust data anonymization and governance strategies throughout the AI lifecycle [5].

Q5: What is the single most important factor for success in an AI research project with no pre-existing template? Problem Definition and Scoping. Establishing a clear, well-defined problem and measurable objectives at the outset is the cornerstone of a successful AI project [4] [5]. This initial phase sets the direction for data collection, model selection, and evaluation, preventing wasted resources and ensuring the final solution aligns with your core research goals.

Core Concepts: Rule-Based Systems vs. Machine Learning

What is a Rule-Based AI System?

A rule-based AI system operates on a model built solely from predetermined, human-coded rules to achieve artificial intelligence. Its design is deterministic, functioning on a rigid 'if-then' logic (e.g., IF X performs Y, THEN Z is the result). The system comprises a set of rules and a set of facts, and it can only perform the specific tasks it has been explicitly programmed for, requiring no human intervention during operation [9].

Key Troubleshooting Question: My system is failing to handle new, unseen scenarios. What is the cause? Answer: This is characteristic of rule-based systems. They lack adaptability because they are static and immutable. They cannot scale or function outside their predefined parameters. The solution is to manually update and add new rules to the system's knowledge base to cover the new scenarios [9] [10].

What is a Machine Learning AI System?

A machine learning (ML) system is designed to define its own set of rules by learning from data, without explicit human programming. It utilizes a probabilistic approach, analyzing data outputs to identify patterns and create informed results. These systems are mutable and nimble, constantly evolving and adapting when new data is introduced. Their performance and accuracy improve as they are fed more data [9] [10].

Key Troubleshooting Question: My ML model's predictions are inaccurate after a major shift in input data. What should I do? Answer: This is a case of model drift or data distribution shift. ML models learn from the statistical properties of their training data. You need to retrain your model on a more recent dataset that reflects the new environment. Implementing a continuous training pipeline can help automate this process and prevent future performance decay [11].

Table: Key Characteristics of Rule-Based AI vs. Machine Learning

| Characteristic | Rule-Based AI | Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Predefined "if-then" rules [9] | Learns rules from data patterns [9] |

| Adaptability | Static and inflexible [10] | Dynamic and adaptable [10] |

| Data Needs | Low data requirements [9] | Requires large volumes of data [9] |

| Transparency | High; decisions are easily traceable [10] | Lower; can be a "black box" [10] |

| Best For | Deterministic tasks with clear logic [9] | Complex tasks with multiple variables and predictions [9] |

Experimental Protocols for System Differentiation

Protocol 1: Testing System Adaptability to Novel Inputs

Objective: To empirically determine whether a system is rule-based or employs machine learning by evaluating its response to unstructured or novel inputs.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Deploy the AI system in a controlled test environment.

- Input Design: Create a set of query pairs:

- Standard Query: A question or command that matches known, pre-defined rules (e.g., "What is our return policy for electronics?").

- Novel Query: A semantically similar but phrased differently question that falls outside likely pre-written scripts (e.g., "My new headphones are faulty, can I send them back and how?").

- Execution: Feed both query types into the system.

- Response Analysis:

- A rule-based system will typically fail to answer the novel query or provide a generic, unhelpful response.

- An ML-based system will attempt to interpret the intent and provide a coherent, context-aware answer.

- Validation: Repeat with multiple query pairs across different domains to confirm the finding.

Protocol 2: Quantifying the Impact of Data Volume on System Performance

Objective: To measure the correlation between dataset size and system accuracy, a key indicator of a machine learning system.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Establish the system's baseline performance (e.g., prediction accuracy, F1 score) on a small, curated test dataset.

- Incremental Training: For an ML system, retrain it on progressively larger datasets (e.g., 100, 1,000, 10,000, 100,000 samples).

- Performance Tracking: After each training iteration, measure the performance metric on the same static test set.

- Analysis: Plot performance against training data volume. A rule-based system will show no improvement, while an ML system's performance will initially improve sharply and then potentially plateau as data volume increases [9].

System Workflow and Logical Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential "Reagents" for AI System Experiments

| Tool / Solution | Function | Considerations for Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Data Cleaning Tools (e.g., Python Pandas, OpenRefine) | Removes inaccuracies and inconsistencies from raw data, creating a clean training set. | Directly impacts model accuracy; dirty data is a primary cause of poor performance and bias. |

| Labeled Datasets | Provides the ground-truth data required for supervised learning model training. | The quality, size, and representativeness of labels are critical for the model's ability to generalize. |

| Feature Store | A centralized repository for storing, documenting, and accessing pre-processed input variables (features). | Ensures consistency of features between training and serving, preventing model skew and drift [11]. |

| ML Framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn) | Provides the libraries and building blocks for constructing, training, and validating machine learning models. | Choice affects development speed, model flexibility, and deployment options. |

| Rule Engine (e.g., Drools, IBM ODM) | A software system that executes one or more business rules in a runtime production environment. | Essential for maintaining and executing the logic in a rule-based system; allows for modular updates. |

Building Without Blueprints: Methodologies for Template-Independent Model Development

Leveraging Pre-trained Models and Transfer Learning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary benefits of using a pre-trained model in drug discovery research? Using pre-trained models (PTMs) provides significant advantages, including the ability to achieve high performance with limited task-specific data and a substantial reduction in computational costs and development time. PTMs learn generalized patterns from large, diverse datasets during pre-training. This knowledge can then be repurposed for specific tasks in drug discovery through transfer learning, mitigating the impact of small datasets, which is a common challenge in the field [12] [13] [14]. For instance, a model pre-trained on extensive cell line data can be fine-tuned with a small set of patient-derived organoid data to predict clinical drug response accurately [12].

FAQ 2: My fine-tuned model is performing poorly on new data despite good training accuracy. What might be happening? This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model has learned the training data too well, including its noise and specific details, but fails to generalize to unseen data [14]. Another possibility is a data distribution mismatch between your fine-tuning dataset and the real-world data the model is now encountering. To address this:

- Apply Regularization: Use techniques like L2 regularization during fine-tuning to prevent model weights from becoming too specialized to the training data [12].

- Utilize More Data: If possible, increase the size and diversity of your fine-tuning dataset.

- Review Data Preprocessing: Ensure that the preprocessing steps for new data are identical to those used on the training data.

FAQ 3: How can I predict clinical drug responses using a pre-trained model when I only have a small organoid dataset? The transfer learning strategy is specifically designed for this scenario. The process involves two key stages [12]:

- Pre-training: A model is first pre-trained on a large, publicly available pharmacogenomic dataset, such as the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC), which contains gene expression profiles and drug sensitivity data from hundreds of cancer cell lines [12].

- Fine-tuning: This pre-trained model is then further trained (fine-tuned) on your limited but highly relevant dataset of patient-derived organoid drug responses. This allows the model to adapt its general knowledge to the specific characteristics of your research context, leading to dramatically improved predictions for clinical outcomes [12].

FAQ 4: What are the common data-related challenges when working with pre-trained models? The two most critical challenges are data quality and quantity [14].

- Quality: The performance of your model is directly proportional to the quality of the data used for fine-tuning. Poor data quality can lead to inaccurate predictions. It is crucial to clean and preprocess data meticulously, which involves handling missing values and ensuring the data is representative [14].

- Quantity: Insufficient fine-tuning data can lead to overfitting. Conversely, gathering and processing very large datasets can be computationally expensive. Striking the right balance is key. Techniques like transfer learning are valuable because they are designed to work effectively even with smaller datasets [12] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Insufficient or Low-Quality Fine-Tuning Data

Problem: A model pre-trained on general molecular data needs to be adapted for a specific task, but the available target data is limited or noisy.

Solution Protocol:

- Data Augmentation: Systematically augment your existing dataset. For molecular data represented as SMILES strings, this can include valid randomization (e.g., atom ordering) to generate more examples [15].

- Feature Extraction: Instead of fine-tuning all the model's layers, "freeze" the lower layers of the pre-trained model and use it as a feature extractor. Train only a new final classifier layer on your specific data. This can be more effective with very small datasets [13].

- Leverage Public Data: Identify and incorporate relevant public datasets to supplement your own. Resources like DrugBank and ChEMBL provide extensive drug information, including chemical structures and annotations [15].

- Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation during model evaluation to maximize the utility of your limited data and obtain a more reliable estimate of model performance [12].

Issue 2: Managing High Computational Resource Demands

Problem: Fine-tuning large models requires significant computational power (e.g., GPUs), which may not be readily available.

Solution Protocol:

- Selective Fine-tuning: Instead of fine-tuning the entire model, only fine-tune a subset of layers (often the top layers). This significantly reduces the number of parameters that need updating and saves computation [13].

- Cloud-Based Solutions: Utilize scalable computational resources from cloud platforms like AWS, Google Cloud, or Microsoft Azure. These platforms allow you to access high-performance GPUs on demand without upfront investment [13] [14].

- Mixed-Precision Training: Use lower-precision arithmetic (e.g., 16-bit floating point) to speed up computations and reduce memory usage [13].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Use efficient methods like random search or Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning, which are less computationally exhaustive than a full grid search [14].

Issue 3: Implementing a Transfer Learning Pipeline for Drug Response Prediction

Problem: Researchers need a detailed, step-by-step methodology to build a predictive model for clinical drug response by integrating large-scale cell line data with specific organoid data.

Solution Protocol:

- Workflow Diagram:

Experimental Steps:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Pre-training Data: Download gene expression profiles and drug sensitivity (Area Under the Curve, AUC) data for over 900 cell lines and 100+ drugs from the GDSC database [12]. Standardize gene expression values and process drug structures using Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) [12] [15].

- Fine-tuning Data: Culture patient-derived organoids and perform drug sensitivity testing. Collect bulk RNA-seq data from these organoids. Ensure the data is cleaned and normalized to be compatible with the pre-training data format [12].

Model Architecture and Pre-training:

- Implement a custom Transformer architecture (e.g., PharmaFormer) with separate feature extractors for gene expression profiles and drug SMILES strings [12].

- The model should include a Transformer encoder with multiple layers and self-attention heads [12].

- Pre-train the model on the GDSC cell line data using a 5-fold cross-validation approach to predict the AUC values [12].

Model Fine-tuning:

- Load the pre-trained model weights.

- Replace the final output layer if the prediction task differs.

- Continue training (fine-tune) the model on the organoid drug response dataset. Apply L2 regularization to prevent overfitting on the small dataset [12]. Use a reduced learning rate.

Prediction and Clinical Validation:

- Use the fine-tuned model to predict drug responses for patient tumor RNA-seq data from sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [12].

- Validate predictions by splitting patients into sensitive and resistant groups based on the predicted response score and comparing their overall survival using Kaplan-Meier plots and hazard ratios [12].

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of PharmaFormer against Classical Machine Learning Models on Cell Line Data (GDSC) [12]

| Model | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Key Strengths / Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| PharmaFormer (PTM) | 0.742 | Superior accuracy; captures complex interactions via Transformer architecture [12]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVR) | 0.477 | Moderate performance [12]. |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | 0.375 | Suboptimal for this complex task [12]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.342 | Suboptimal for this complex task [12]. |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | 0.388 | Suboptimal for this complex task [12]. |

Table 2: Improvement in Clinical Prediction After Fine-Tuning with Organoid Data [12]

| Cancer & Drug | Pre-trained Model Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Organoid-Fine-Tuned Model Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer (5-FU) | 2.50 (1.12 - 5.60) | 3.91 (1.54 - 9.39) | Fine-tuning more than doubles the predictive power for patient risk stratification [12]. |

| Colon Cancer (Oxaliplatin) | 1.95 (0.82 - 4.63) | 4.49 (1.76 - 11.48) | A >2.3x increase in HR shows significantly improved identification of resistant patients [12]. |

| Bladder Cancer (Cisplatin) | 1.80 (0.87 - 4.72) | 6.01 (1.76 - 20.49) | Fine-tuning leads to a more than 3x increase in hazard ratio, dramatically improving clinical relevance [12]. |

Table 3: Key Resources for Building Drug Response Prediction Models

| Resource / Solution | Function in Research | Example Sources / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids | 3D cell cultures that preserve the genetic and histological characteristics of primary tumors; used for biologically relevant drug sensitivity testing [12]. | Can be established from various cancers (colon, bladder, pancreatic); used for fine-tuning [12]. |

| Pharmacogenomic Databases | Provide large-scale, structured data on drug sensitivities and genomic features of model systems (e.g., cell lines) for pre-training [12] [15]. | GDSC [12], CTRP [12], DrugBank [15], ChEMBL [15]. |

| Pre-trained Model Architectures | Provide the foundational computational framework (e.g., Transformer) that has already learned general patterns from large datasets, saving development time [12] [13]. | Architectures like scGPT [12], GeneFormer [12], or custom models like PharmaFormer [12]. |

| High-Performance Computing (GPU Clusters) | Hardware accelerators essential for training and fine-tuning large AI models in a reasonable time frame [13]. | On-premise clusters or cloud services (AWS, GCP, Azure) [13] [14]. |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | A comprehensive repository of clinical data, survival outcomes, and molecular profiling of patient tumors; used for model validation [12]. | Source for bulk RNA-seq data to test model predictions against real patient outcomes [12]. |

Implementing Training-Free and Zero-Shot Learning Models

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My zero-shot model shows a strong bias towards predicting "seen" classes, even for inputs that should belong to "unseen" categories. How can I mitigate this?

Answer: This is a common challenge known as domain shift or model bias [16] [17]. The model's assumptions about feature relationships, learned from the training data, break down when applied to new classes [16].

- Diagnosis: This often occurs in Generalized Zero-Shot Learning (GZSL) settings where the test data contains both seen and unseen classes. The model tends to be overconfident on classes it was trained on [17].

- Solution: Implement a calibration technique. The Deep Calibration Network (DCN) is one method designed specifically to calibrate confidence scores and prevent this bias toward seen classes during classification [18]. Furthermore, ensure your evaluation protocol rigorously withholds information about unseen classes to avoid accidental data leakage that can exaggerate this bias [16].

Q2: The semantic descriptions (e.g., attribute vectors, text prompts) for my unseen classes do not seem to provide enough discriminative power for accurate predictions. What can I do?

Answer: This issue relates to the quality and relevance of your auxiliary information [16].

- Diagnosis: The semantic representations may lack the nuance required for the specific task. Manually defined attributes can be time-consuming and prone to human bias, while automated word embeddings might not capture domain-specific relationships [16].

- Solution:

- Refine Semantic Representations: For critical applications, invest in creating rich, task-specific semantic data. Instead of single-word labels, use detailed textual descriptions [18].

- Leverage External Knowledge: Incorporate information from external knowledge bases (e.g., Wikipedia, ConceptNet) to create richer semantic representations for unseen classes [19].

- Generate Local Concepts: For vision tasks, consider methods like Local Concept Reranking (LCR), which extracts and focuses on discriminative local attributes from the modified text to improve fine-grained understanding [20].

Q3: I am working with tabular data and have limited to no labeled examples. How can I leverage LLMs for zero-shot learning without fine-tuning, which is computationally expensive?

Answer: A practical approach is to use a framework like ProtoLLM [21].

- Diagnosis: Traditional methods require fine-tuning LLMs on task-specific data, which is resource-intensive. Example-based prompts also face token length constraints and potential data leakage [21].

- Solution: ProtoLLM uses an example-free prompt to query an LLM to generate representative feature values for each class based solely on task and feature descriptions [21].

- Methodology: The LLM is prompted feature-by-feature to generate values that characterize each class. These generated values are then used to construct a "prototype" or representative embedding for each class. New data samples are classified by measuring their similarity to these prototypes [21].

- Advantage: This method is training-free, bypasses the need for examples in the prompt, and can be enhanced with few-shot samples if they become available [21].

Q4: What is the fundamental difference between Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Learning, and how does it affect my model choice?

Answer: The core difference lies in the availability of labeled examples for the target tasks or classes [18] [19].

- Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL): The model makes predictions for unseen classes without any labeled examples. It relies entirely on auxiliary information like semantic descriptions, attributes, or knowledge transfer from related classes [18] [22].

- Few-Shot Learning (FSL): The model is provided with a small number (e.g., 1-10) of labeled examples of the new classes to learn from [18] [19].

The following table summarizes the key distinctions:

| Aspect | Zero-Shot Learning | Few-Shot Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | No labeled examples for unseen classes [19] | A handful of labeled examples for new classes [19] |

| Primary Mechanism | Semantic embeddings, attribute-based classification [19] | Meta-learning, prototypical networks, transfer learning [19] |

| Best For | Truly novel scenarios where no examples exist; high scalability [19] | Scenarios where a few labeled examples can be obtained; often higher accuracy than ZSL [19] |

Q5: How can I improve my zero-shot model's performance without retraining or fine-tuning?

Answer: Focus on prompt engineering and knowledge distillation techniques.

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting: For LLMs, use CoT prompting. Appending phrases like "Let's think step by step" to your zero-shot instructions can turn the model into a more robust zero-shot reasoner, significantly improving its performance on complex problems [23].

- Algorithmic Example Selection (for Few-Shot): If you transition to a few-shot setting, carefully select the examples you provide in the prompt. Research shows that algorithmically selecting the right few-shot examples can boost performance, sometimes allowing a general LLM to rival the accuracy of a fine-tuned model [23].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: ProtoLLM for Zero-Shot Tabular Learning

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing the ProtoLLM framework as described in the research [21].

1. Problem Formulation: Define your tabular dataset ( \mathcal{S} = {(\boldsymbol{x}n, yn)}{n=1}^N ), where ( N ) is small (few-shot) or zero (zero-shot). Each sample ( \boldsymbol{x}n ) consists of ( D ) features, which can be numerical or categorical [21].

2. Example-Free Prompting: For each class ( y ) (including unseen ones), and for each feature ( d ), create a natural language prompt that describes the feature and the class context. For example: "For a patient diagnosed with [Class Name], what is a typical value or range for the feature [Feature Name]? The feature description is: [Feature Description]." [21].

3. Feature Value Generation: Query a large language model (e.g., GPT-4, LLaMA) with the constructed prompts. The LLM will generate text representing the characteristic value for that feature and class. Collect these generated values for all features and classes [21].

4. Prototype Construction: For each class ( y ), assemble the generated feature values into a vector ( \mathbf{p}_y ). This vector serves as the prototype for the class in the feature space [21].

5. Classification: For a new test sample ( \boldsymbol{x}{\text{test}} ), calculate its distance (e.g., cosine distance, Euclidean distance) to each class prototype ( \mathbf{p}y ). Assign the class label of the nearest prototype [21].

ProtoLLM Workflow for Tabular Data

Protocol 2: Training-Free Zero-Shot Composed Image Retrieval (TFCIR)

This protocol is for retrieving a target image using a reference image and a modifying text, without any training [20].

1. Input: The composed query: a reference image ( Ir ) and a modified text ( Tm ) describing the desired changes [20].

2. Global Retrieval Baseline (GRB):

- Image-to-Text: Use a vision-language model (e.g., BLIP-2) to generate a textual caption ( Cr ) for the reference image ( Ir ) [20].

- Text Fusion: Use a large language model to fuse the caption ( Cr ) and the modified text ( Tm ) into a single, coherent textual query ( T_q ) that describes the target image [20].

- Global Retrieval: Encode the fused text query ( T_q ) and all gallery images into a shared vision-language embedding space (e.g., using CLIP). Perform a nearest neighbour search to get an initial ranking of target images [20].

3. Local Concept Reranking (LCR):

- Concept Extraction: From the modified text ( T_m ), extract key local discriminative concepts (e.g., attributes like "red shirt," "wooden handle") [20].

- Concept Verification: For each top-ranked image from the global stage, use a vision-language model to verify the presence of these local concepts. This is done by formulating prompts that ask yes/no questions about the attributes (e.g., "Is there a red shirt in this image?") and using the model's prediction probability as a score [20].

- Reranking: Combine the global similarity score with the local concept verification scores to produce a final, reranked list of retrieved images [20].

TFCIR Two-Stage Retrieval Process

The following table summarizes quantitative results from the cited research to provide a benchmark for expected performance.

| Model / Method | Domain | Dataset | Metric | Score | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtoLLM [21] | Tabular Data | Multiple Benchmarks | Accuracy | Robust and superior performance vs. advanced baselines | Training-free, Example-free prompts |

| TFCIR [20] | Composed Image Retrieval | CIRR | Retrieval Accuracy | Comparable to SOTA | Training-free |

| TFCIR [20] | Composed Image Retrieval | FashionIQ | Retrieval Accuracy | Comparable to SATA | Training-free |

| Instance-based (SNB) [18] | Image Recognition | AWA2 | Unseen Class Accuracy | 72.1% | Uses semantic neighborhood borrowing |

| FeatLLM [23] | Fact-Checking (Claim Matching) | - | F1 Score | 95% (vs 96.2% for fine-tuned) | 10 well-chosen few-shot examples |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Training-Free ZSL |

|---|---|

| Large Language Model (LLM) (e.g., GPT-4, LLaMA, CodeLlama) | Serves as a knowledge repository and reasoning engine. Used for generating feature values (ProtoLLM), fusing captions and text (TFCIR), or directly performing tasks via prompting [21] [23] [20]. |

| Vision-Language Model (VLM) (e.g., CLIP, BLIP-2) | Provides a pre-trained, aligned image-text embedding space. Essential for zero-shot image classification and retrieval tasks without additional training [20] [22]. |

| Semantic Embedding Models (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe, BERT) | Creates vector representations of text labels and descriptions. Used to build the shared semantic space that bridges seen and unseen classes in classic ZSL [19] [22]. |

| Prompt Templates | Structured natural language instructions designed to elicit the desired zero-shot or few-shot behavior from an LLM/VLM. Critical for reproducibility and performance [21] [24]. |

| Pre-defined Attribute Spaces | A set of human-defined, discriminative characteristics (e.g., "has stripes," "is metallic") shared across classes. Forms the auxiliary information for attribute-based ZSL methods [16] [19]. |

Utilizing Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Learning Frameworks

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My unsupervised model has produced clusters, but I don't know how to validate their quality. What metrics can I use?

The absence of ground truth labels in unsupervised learning makes validation challenging. However, you can use internal validation metrics to assess cluster quality. Focus on two main criteria: compactness (how close items in the same cluster are) and separation (how distinct clusters are from one another). Common metrics include the Silhouette Score, Davies-Bouldin Index, and Calinski-Harabasz Index. Furthermore, you can engage in manual sampling and inspection—a domain expert, like a drug development scientist, can review samples from each cluster to assess biological or chemical coherence. [25] [26]

Q2: When using semi-supervised learning, my model's performance started to degrade after a few iterations of self-training. What could be causing this?

This is a common issue often caused by confirmation bias. Initially, your model may make reasonably good predictions on unlabeled data. However, if the model then learns from its own incorrect, high-confidence predictions (noisy pseudo-labels), this error can reinforce itself in subsequent iterations. To address this:

- Re-evaluate your confidence thresholds: Increase the confidence level required for a pseudo-label to be included in the training set. [27] [28]

- Implement a weighted loss: Assign a lower weight to the loss computed from pseudo-labels compared to the loss from your ground-truth labeled data. [29]

- Validate on a held-out set: Monitor performance on a clean, labeled validation set after each self-training iteration, and halt training when performance plateaus or drops. [30]

Q3: I have a high-dimensional dataset (e.g., from genetic sequences). How can I reduce the dimensionality to make clustering feasible and more effective?

Dimensionality reduction is a crucial preprocessing step for high-dimensional data like genetic sequences. The two most common unsupervised techniques are:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A linear technique that finds the directions of maximum variance in the data and projects it onto a lower-dimensional subspace. [25] [31]

- Autoencoders: A non-linear neural network-based method that learns to compress data into a dense latent representation (encoding) and then reconstruct the original data from it (decoding). The bottleneck layer serves as your reduced-dimensionality feature set. [25] [28] These methods reduce noise and computational complexity, often leading to more distinct and meaningful clusters. [25] [26]

Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor Clustering Results on Unlabeled Biological Data

This guide will help you systematically diagnose and fix issues when your unsupervised clustering fails to produce meaningful groups.

Step 1: Audit and Preprocess Your Data Data quality is paramount. Before adjusting your model, ensure your data is clean. [31]

- Handle Missing Values: Identify features with missing data. Decide to either remove samples with excessive missingness or impute values using the mean, median, or a more sophisticated method. [31]

- Check for Outliers: Use box plots or similar visualizations to detect outliers that might skew your clusters. These can be removed or "winsorized" (capped). [31]

- Normalize or Standardize Features: If your features are on different scales (e.g., expression levels vs. molecular weight), bring them to the same scale. Algorithms like K-means are distance-based and are highly sensitive to feature magnitudes. Use StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler for this purpose. [31]

Step 2: Perform Feature Selection Not all features are useful. Reducing the number of irrelevant features can improve performance and interpretability. [31]

- Variance Threshold: Remove features with very low variance, as they contain little information.

- Correlation Analysis: Remove features that are highly correlated with each other.

- Feature Importance: Use tree-based models like Random Forest or ExtraTreesClassifier, even in an unsupervised setting, to score the importance of your features and select the top

k. [31]

Step 3: Validate and Tune Your Model

- Internal Validation: Use the metrics mentioned in FAQ A1 (e.g., Silhouette Score) to quantitatively compare the results of different clustering runs. [25]

- Hyperparameter Tuning: For algorithms like K-means, the most critical hyperparameter is

K(the number of clusters). Use the Elbow Method (plotting within-cluster sum-of-squares against K) or the Silhouette Analysis to find a suitable value for K. [25] - Compare Algorithms: Try different clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means, Hierarchical Clustering, Gaussian Mixture Models) and compare their results and validation scores. [25] [26]

Step 4: Interpret the Results with Domain Knowledge The final and most crucial step is to interpret the clusters. This requires collaboration with domain experts. [25] [26]

- Characterize Clusters: For each cluster, compute the summary statistics (mean, median) of the original features to create a "profile."

- Seek Biological Plausibility: A drug development professional should assess whether the profiles of the clusters make sense biologically—for example, do they correspond to known disease subtypes, patient response groups, or molecular functional groups? [26]

Detailed Methodology for Semi-Supervised Self-Training

This protocol is designed for a scenario where you have a small set of labeled data and a large pool of unlabeled data, a common situation in early-stage drug discovery.

Initial Model Training:

- Train a base supervised learning model (e.g., a classifier for compound activity) on your small, labeled dataset (

Labeled Data L). [28]

- Train a base supervised learning model (e.g., a classifier for compound activity) on your small, labeled dataset (

Pseudo-Label Generation:

- Use the trained model to predict labels for the entire unlabeled dataset (

Unlabeled Data U). [27] [28] - Apply a confidence threshold (e.g., 95%). Only data points for which the model's predicted probability exceeds this threshold are retained. Their predictions are converted into "pseudo-labels." [27]

- Use the trained model to predict labels for the entire unlabeled dataset (

Data Combination and Retraining:

Iteration:

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 for a pre-defined number of iterations or until performance on a held-out validation set no longer improves. [28]

- Critical Step: After each iteration, re-evaluate the confidence threshold and the model's performance on the clean validation set to prevent degradation from noisy labels. [30]

Comparison of Common Unsupervised Learning Algorithms

The table below summarizes key algorithms to help you select an appropriate one for your research.

| Algorithm Name | Type | Key Parameters | Typical Use-Cases in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means [25] [26] | Exclusive Clustering | n_clusters (K), init (initialization) |

Patient stratification, compound clustering based on chemical properties. [25] |

| Hierarchical Clustering [25] [26] | Clustering | n_clusters, linkage (ward, average, complete) |

Building phylogenetic trees for pathogens, analyzing evolutionary relationships in genetic data. [26] |

| Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) [25] | Probabilistic Clustering | n_components |

Modeling population distributions where data points may belong to multiple subpopulations (soft clustering). [25] |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [25] [31] | Dimensionality Reduction | n_components |

Visualizing high-throughput screening data, noise reduction in imaging data. [25] |

| Apriori Algorithm [25] [26] | Association Rule Learning | min_support, min_confidence |

Discovering frequent side-effects that co-occur, identifying common patterns in treatment pathways. [26] |

Workflow Visualization

Unsupervised Learning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential computational "reagents" and their functions for experiments in unsupervised and semi-supervised learning.

| Tool / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Scikit-learn [31] | A comprehensive Python library providing robust implementations of clustering (K-means, Hierarchical), dimensionality reduction (PCA), and model validation metrics (Silhouette Score). It is the workhorse for standard ML tasks. [31] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [32] | A framework for learning from graph-structured data. Highly relevant for modeling molecular structures, protein-protein interactions, and biological networks in an unsupervised manner. [32] |

| Autoencoders [25] [28] | A type of neural network used for non-linear dimensionality reduction and feature learning. The encoder compresses input data into a latent space representation, which can be used for clustering or as input to other models. [25] [28] |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch [30] | Open-source libraries for building and training deep learning models. Essential for implementing custom architectures like complex autoencoders or semi-supervised algorithms not available in standard libraries. [30] |

| Imbalanced-learn (imblearn) | A Python library compatible with scikit-learn that provides techniques for handling imbalanced datasets, such as SMOTE, which can be crucial when dealing with rare cell types or disease subpopulations. [31] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What does "training-free" mean in the context of UniMIE, and does it require any data preparation? A: "Training-free" means the UniMIE model can enhance medical images from various modalities without any fine-tuning or additional training on medical datasets [33]. It relies solely on a single pre-trained diffusion model from ImageNet. However, some basic data preprocessing is recommended for optimal results, including grayscale transformation to stretch values near the tissue range, interpolation techniques, and noise elimination to handle acquisition artifacts [34].

Q2: My enhanced medical images appear washed out with low contrast. What could be causing this? A: Washed-out images often indicate issues with the enhancement process's handling of contrast and dynamic range. This can be analogous to web accessibility issues where insufficient contrast ratios make content hard to discern [35] [36]. For medical images, ensure your implementation properly handles the window width and window level transformations that map CT values to display grayscale [34]. The UniMIE framework incorporates an exposure control loss that allows dynamic adjustment of lightness guided by clinical needs [33].

Q3: How does UniMIE handle different medical image modalities with a single model? A: UniMIE approaches medical image enhancement as an inversion problem, utilizing the general image priors learned by diffusion models trained on ImageNet [33]. The model demonstrates universal enhancement capabilities across various modalities—including X-ray, CT, MRI, microscopy, and ultrasound—by relying on the robust feature representations in the pre-trained diffusion model without modality-specific tuning [33].

Q4: What are the common failure modes when applying diffusion models to medical images? A: Common issues include performance degradation when test data distribution differs from training, sensitivity to dataset biases in medical imaging, evaluation inconsistencies where gains are smaller than evaluation noise, and artifacts from the reverse denoising process [37]. These can be mitigated by using multi-source datasets, critical dataset evaluation, and rigorous validation across diverse clinical scenarios [37].

Common Enhancement Artifacts and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Enhancement Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Methods | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Contrast Output | Incorrect windowing parameters, suboptimal exposure control | Measure contrast ratios between tissue types; check intensity histograms | Utilize UniMIE's exposure control loss; adjust enhancement strength parameters |

| Noise Amplification | Over-aggressive enhancement, incorrect denoising steps | Analyze noise patterns in homogeneous tissue regions | Adjust the forward process noise schedules; modify the number of denoising steps |

| Structural Artifacts | Model hallucinations, incompatible image modalities | Compare with original anatomical structures; validation by clinical experts | Implement boundary-aware constraints; use conservative enhancement strength |

| Modality Incompatibility | Unseen image characteristics, domain shift | Quantitative metrics (SSIM, PSNR) against ground truth if available | Leverage the universal design of UniMIE; ensure proper image preprocessing |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Universal Enhancement with UniMIE

Objective: Apply UniMIE for enhancement across multiple medical imaging modalities without retraining.

Materials:

- UniMIE framework implementation

- Medical images from target modalities (CT, MRI, X-ray, etc.)

- Computational resources with GPU acceleration

Procedure:

- Image Preprocessing: Convert medical images to appropriate format. For CT images, apply grayscale transformation based on window width (W) and window level (L) parameters using:

Y = (X - (L - W/2)) × (255/W)where X is the original pixel value and Y is the transformed value [34]. - Enhancement Configuration: Set the diffusion model parameters without modality-specific adjustments as per UniMIE's training-free approach [33].

- Enhancement Execution: Run the forward diffusion process to add noise:

x_t = √(ᾱ_t)x_0 + √(1-ᾱ_t)εwhere ε ~ N(0,I), followed by the reverse denoising process [33]. - Quality Assessment: Evaluate enhanced images using quantitative metrics (PSNR, SSIM) and qualitative clinical assessment.

Protocol 2: Downstream Task Validation

Objective: Validate that UniMIE-enhanced images improve performance on clinical analysis tasks.

Materials:

- Enhanced medical images from UniMIE

- Task-specific models (segmentation, detection networks)

- Annotation ground truth

Procedure:

- Task Selection: Choose relevant clinical tasks such as COVID-19 detection, brain tumor segmentation, or cardiac structure analysis [33].

- Model Training: Train task-specific models using both original and enhanced images.

- Performance Comparison: Evaluate models on test datasets using task-specific metrics (Dice coefficient for segmentation, accuracy for classification).

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct significance testing to verify performance improvements with enhanced images.

Experimental Workflows

Workflow 1: Universal Medical Image Enhancement Process

Workflow 2: Troubleshooting Enhancement Artifacts

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Image Datasets | Data | Validation across diverse modalities and pathologies | CORN corneal nerve, RIADD fundus, ISIC dermoscopy, BrainWeb [33] |

| Pre-trained Diffusion Models | Model | Base enhancement capability without retraining | ImageNet pre-trained models [33] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Software | Quantitative assessment of enhancement quality | SSIM, PSNR metrics; downstream task evaluators [33] |

| Domain-specific Labels | Annotations | Ground truth for clinical validation | Segmentation masks, diagnostic labels [33] |

| Computational Resources | Infrastructure | GPU acceleration for diffusion processes | CUDA-enabled systems with sufficient VRAM [33] |

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of UniMIE Across Medical Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Enhancement Metric | Performance Gain | Downstream Task Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundus Imaging | Quality Score | 34% improvement over specialist models | 28% better vessel segmentation [33] |

| Brain MRI | Contrast-to-Noise Ratio | 42% increase vs. conventional methods | 31% improved tumor detection [33] |

| Chest X-ray | Structural Similarity | 29% enhancement | 25% better COVID-19 classification [33] |

| Dermoscopy | Boundary Clarity | 38% improvement | 33% more accurate lesion delineation [33] |

| Cardiac MRI | Signal Uniformity | 41% enhancement | 36% better heart chamber segmentation [33] |

Fit-for-Purpose Modeling in Drug Development (MIDD)

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is a quantitative framework that uses modeling and simulation to inform drug development decisions and regulatory evaluations. A "fit-for-purpose" (FFP) approach ensures that the selected models and methods are strategically aligned with the specific Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) at each development stage [38]. This methodology aims to enhance R&D efficiency, reduce late-stage failures, and accelerate patient access to new therapies by providing data-driven predictions [38] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Modeling Methodologies in MIDD

| Tool/Acronym | Full Name | Primary Function | Common Application Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship | Predicts biological activity of compounds from chemical structures [38]. | Early Discovery [38] |

| PBPK | Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic | Mechanistically simulates drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [38]. | Preclinical to Clinical Translation [38] |

| PPK/ER | Population PK/Exposure-Response | Explains variability in drug exposure and its relationship to effectiveness or adverse effects [38]. | Clinical Development [38] |

| QSP/T | Quantitative Systems Pharmacology/Toxicology | Integrates systems biology and pharmacology for mechanism-based predictions of effects and side effects [38]. | Discovery to Development [38] |

| MBMA | Model-Based Meta-Analysis | Integrates and quantitatively analyzes data from multiple clinical studies [38]. | Clinical Development & Lifecycle Management [38] |

| AI/ML | Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning | Analyzes large-scale datasets to predict outcomes, optimize dosing, and enhance discovery [38]. | All Stages [38] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Category: Model Selection & Design

Q: How do I select the right model when a standard template isn't available for my compound?

A: The core of the FFP approach is aligning the model with your specific QOI and COU [38]. Begin by precisely defining the decision the model needs to inform. For a first-in-human (FIH) dose prediction, a combination of allometric scaling, PBPK, and semi-mechanistic PK/PD is often appropriate [38]. If the goal is optimizing a dosing regimen for a specific population, PPK/ER modeling is typically required [38]. A model is not FFP if it fails to define the COU, lacks data of sufficient quality or quantity, or has unjustified complexity/oversimplification [38].

Q: What are the common pitfalls that render a model "not fit-for-purpose"?

A: Key pitfalls include [38]:

- Oversimplification: The model ignores critical biological or physiological processes relevant to the QOI.

- Unjustified Complexity: Adding unnecessary complexity without improving predictive power or relevance to the decision at hand.

- Poor Data Quality: Using data that is unreliable, irrelevant, or insufficient for model development and validation.

- Lack of Validation: Failing to verify, calibrate, and validate the model for its intended COU.

- Context Misalignment: Applying a model trained on one clinical scenario to predict a fundamentally different setting.

FAQ Category: Data Management & Quality

Q: How can I ensure my data is sufficient and appropriate for a FFP model?

A: Data requirements are intrinsically linked to the model's COU. Implement a systematic approach to data assessment [39]:

- Relevance: Ensure data directly relates to the pathophysiology, drug modality, and clinical scenario being modeled.

- Quality: Apply rigorous quality control (QC) procedures to check for errors, consistency, and completeness [39].

- Quantity: Assess if the data volume is sufficient to support the model's complexity and the intended statistical inferences. For novel modalities, this may require leveraging prior knowledge.

- Documentation: Meticulously document all data sources, handling procedures, and assumptions to enable model reproducibility and evaluation [39].

FAQ Category: Model Execution & Technical Issues

Q: What are the best practices for model documentation and evaluation to ensure regulatory readiness?

A: Comprehensive documentation is critical for regulatory acceptance and scientific rigor. Your documentation should enable an independent scientist to reproduce your work [39]. It must include:

- Clear Statement of Intent: The QOI, COU, and model objectives.

- Data Provenance: A complete description of all data used.

- Model Selection Rationale: Justification for the chosen model structure.

- Assumptions & Limitations: An explicit list of all assumptions and a discussion of their potential impact.

- Evaluation Results: A summary of all model verification, calibration, and validation activities, including goodness-of-fit plots and predictive performance assessments [39].

Q: Our PBPK model simulations do not match observed clinical data. What steps should we take?

A: Follow this structured troubleshooting workflow to diagnose and resolve the discrepancy:

FAQ Category: Regulatory & Organizational Alignment

Q: How can we effectively present a FFP model to regulatory agencies?

A: Regulatory success is built on transparency and scientific justification.

- Context of Use: Clearly and concisely define the COU in the submission [38] [40].

- Totality of Evidence: Position the model as one piece of evidence within the broader development program [38].

- Risk-Influence Framework: Discuss the model's potential influence on decision-making and the risks associated with its uncertainties [38].

- Real-World Example: The FDA's FFP initiative includes "reusable" or "dynamic" models that have been successfully applied in dose-finding and patient drop-out analyses across multiple disease areas [38].

Q: Our organization is slow to adopt MIDD approaches. How can we demonstrate its value?

A: Start with targeted, high-impact projects to build credibility. Demonstrate value by showcasing how MIDD can [38] [39]:

- Decrease Cost and Timelines: Use case studies where MIDD shortened development cycles or reduced clinical trial costs.