Beyond Trial and Error: Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Model Refinement of Low-Accuracy Targets

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on refining computational and biological models with initially low accuracy.

Beyond Trial and Error: Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Model Refinement of Low-Accuracy Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on refining computational and biological models with initially low accuracy. It explores the foundational challenges, presents cutting-edge methodological workflows like genetic algorithms and machine learning-based refinement, offers troubleshooting strategies to overcome common pitfalls, and details robust validation frameworks. By integrating insights from recent advances in fields ranging from genomics to quantitative systems pharmacology, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools to enhance predictive accuracy, generate testable hypotheses, and accelerate the translation of models into reliable biomedical insights.

The Low-Accuracy Challenge: Diagnosing the Root Causes in Biological Models

In both drug discovery and systems biology, the selection and validation of biological targets are foundational to success. However, these fields are persistently plagued by the challenge of low-accuracy targets, leading to high failure rates and inefficient resource allocation. In clinical drug development, a staggering 90% of drug candidates fail after entering clinical trials [1]. The primary reasons for these failures are a lack of clinical efficacy (40-50%) and unmanageable toxicity (30%) [1]. Similarly, in systems biology modelling, a systematic analysis revealed that approximately 49% of published mathematical models are not directly reproducible due to incorrect or missing information in the manuscript [2]. This article explores the root causes of these low-accuracy targets and provides a technical troubleshooting guide for researchers seeking to overcome these critical challenges.

Quantitative Data on Failure Rates

The tables below summarize key quantitative data on failure rates and reasons across drug discovery and computational modeling.

Table 1: Reasons for Clinical Drug Development Failures (2010-2017 Data)

| Reason for Failure | Percentage of Failures |

|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40% - 50% |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | 30% |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties | 10% - 15% |

| Lack of Commercial Needs / Poor Strategic Planning | 10% |

Table 2: Reproducibility Analysis of 455 Published Mathematical Models

| Reproducibility Status | Number of Models | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Directly Reproducible | 233 | 51% |

| Reproduced with Manual Corrections | 40 | 9% |

| Reproduced with Author Support | 13 | 3% |

| Non-reproducible | 169 | 37% |

Table 3: Genetic Evidence Support and Clinical Trial Outcomes

| Trial Outcome Category | Association with Genetic Evidence (Odds Ratio) |

|---|---|

| All Stopped Trials | Depleted (OR = 0.73) |

| Stopped for Negative Outcomes (e.g., Lack of Efficacy) | Significantly Depleted (OR = 0.61) |

| Stopped for Safety Reasons | Associated with highly constrained target genes and broad tissue expression |

| Stopped for Operational Reasons (e.g., COVID-19) | No significant association |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Low-Accuracy Targets

FAQ 1: Why do our drug candidates repeatedly fail in clinical trials due to lack of efficacy, despite promising preclinical data?

Issue: This is the most common failure, accounting for 40-50% of clinical trial stoppages [1]. A primary cause is often inadequate target validation and poor target engagement [3].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Strengthen Genetic Evidence: Retrospective analyses show that clinical trials are less likely to stop for lack of efficacy when there is strong human genetic evidence supporting the link between the drug target and the disease. Trials halted for negative outcomes show a significant depletion of such genetic support (Odds Ratio = 0.61) [4]. Before target selection, consult genetic databases (e.g., Open Targets Platform) to assess this evidence.

- Implement STR and STAR Profiling: Move beyond the traditional focus on Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR). Integrate Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) and the comprehensive Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) [1]. A drug may be potent but fail if it does not reach the target tissue in sufficient concentration (a Class II drug), while another with adequate potency but high tissue selectivity (Class III) might be overlooked but succeed [1].

- Verify Target Engagement in Physiologically Relevant Conditions: Use advanced techniques like the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) to confirm that your drug candidate actually binds to and engages the intended target in intact cells or tissues, preserving physiological conditions [3]. This helps move beyond artificial, purified protein assays.

FAQ 2: How can we reduce late-stage failures due to unmanageable toxicity?

Issue: Toxicity accounts for 30% of clinical failures and can stem from both on-target and off-target effects [1] [4].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Target Gene Properties: Trials stopped for safety reasons are associated with drug targets that are highly constrained in human populations (indicating intolerance to functional genetic variation) and that are broadly expressed across tissues [4]. Prioritize targets with more selective expression profiles.

- Employ Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics:

- Reverse Chemical Genetics: Start with a purified protein target, screen for binders/inhibitors, and then characterize the phenotype in cells/animals. This risks selecting compounds that are optimized for an artificial system [5].

- Forward Chemical Genetics: Start with a phenotypic screen in a disease-relevant cell or animal model to find compounds that produce the desired effect, then work to identify the protein target(s). This "pre-validates" the target in a physiological context but requires effective target deconvolution [5].

- Investigate Polypharmacology: Use unbiased affinity purification and proteomic profiling methods to identify off-target protein interactions that could contribute to toxicity [5]. Understanding a compound's full interaction profile is crucial for optimizing selectivity.

FAQ 3: Why are our computational models and predictions, such as for synthetic lethality, often inaccurate and not reproducible?

Issue: Computational models in systems biology often fail to accurately predict biological outcomes, such as synthetic lethal gene pairs, with one study showing accuracy between only 25-43% [6]. Furthermore, nearly half of all published models are not reproducible [2].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Systematically Address Reproducibility: Follow an 8-point reproducibility scorecard for model creation and reporting [2]. The most common reasons for non-reproducible models are missing parameter values, missing initial conditions, and inconsistencies in model structure (e.g., errors in equations) [2].

- Automate Model Refinement: For network-based dynamic models (e.g., Boolean models), leverage tools like boolmore, a genetic algorithm-based workflow that automatically refines models to better agree with a corpus of perturbation-observation experimental data [7]. This can streamline the laborious manual process of trial-and-error refinement.

- Identify and Rectify Common Failure Modes: When a model prediction fails, systematically check for:

Issue: The drug discovery process is prolonged and costly, with the preclinical phase alone taking 3-6 years [8].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Centralize Data Management: Implement centralized data management software (e.g., a LIMS or ELN) to break down data silos, reduce manual entry errors, and provide a unified view of research activities, enabling real-time informed decisions [8].

- Optimize Experimental Design: Use customizable templates for standardized experimental protocols to ensure consistency and data integrity. Identify Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Quality Attributes (CQAs) early to strengthen protocols [8].

- Enhance Collaboration: Utilize platforms that offer real-time notifications, simultaneous document editing, and robust project tracking to keep cross-functional teams (chemistry, biology, pharmacology) aligned and to identify bottlenecks early [8].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Assessing Target Engagement Using CETSA

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the engagement of a drug molecule with its protein target in intact cells under physiological conditions [3].

Methodology:

- Cell Treatment: Incubate intact cells with the drug candidate or a vehicle control.

- Heat Challenge: Subject the cell aliquots to a range of elevated temperatures. When a drug binds to a target protein, it often stabilizes the protein, increasing its thermal stability.

- Cell Lysis and Protein Solubilization: Lyse the heated cells and separate the soluble (non-denatured) protein from the insoluble (aggregated) protein.

- Target Protein Quantification: Detect and quantify the amount of soluble target protein remaining in each sample using a specific detection method, such as immunoblotting or a target-specific assay.

- Data Analysis: The difference in thermal stability of the target protein between drug-treated and untreated samples is a direct indicator of target engagement.

Protocol 2: Automated Model Refinement with Boolmore

Purpose: To streamline and automate the refinement of a Boolean network model to improve its agreement with experimental data [7].

Methodology:

- Inputs:

- Starting Model: The initial Boolean model to be refined.

- Biological Mechanisms: Known biological constraints expressed as logical relations (e.g., "A is necessary for B").

- Perturbation-Observation Pairs: A curated compilation of experimental results, each describing the state of a node under a specific perturbation context.

- Genetic Algorithm Workflow:

- Mutation: The tool generates a population of new models by mutating the Boolean functions of the starting model, while preserving user-defined biological constraints and the structure of the starting interaction graph.

- Prediction: For each model, it calculates the long-term behaviors (minimal trap spaces) under each experimental setting.

- Fitness Scoring: It computes a fitness score for each model by quantifying its agreement with the compendium of experimental results.

- Selection: The models with the top fitness scores are retained for the next iteration.

- Output: A refined Boolean model with higher accuracy and new, testable predictions [7].

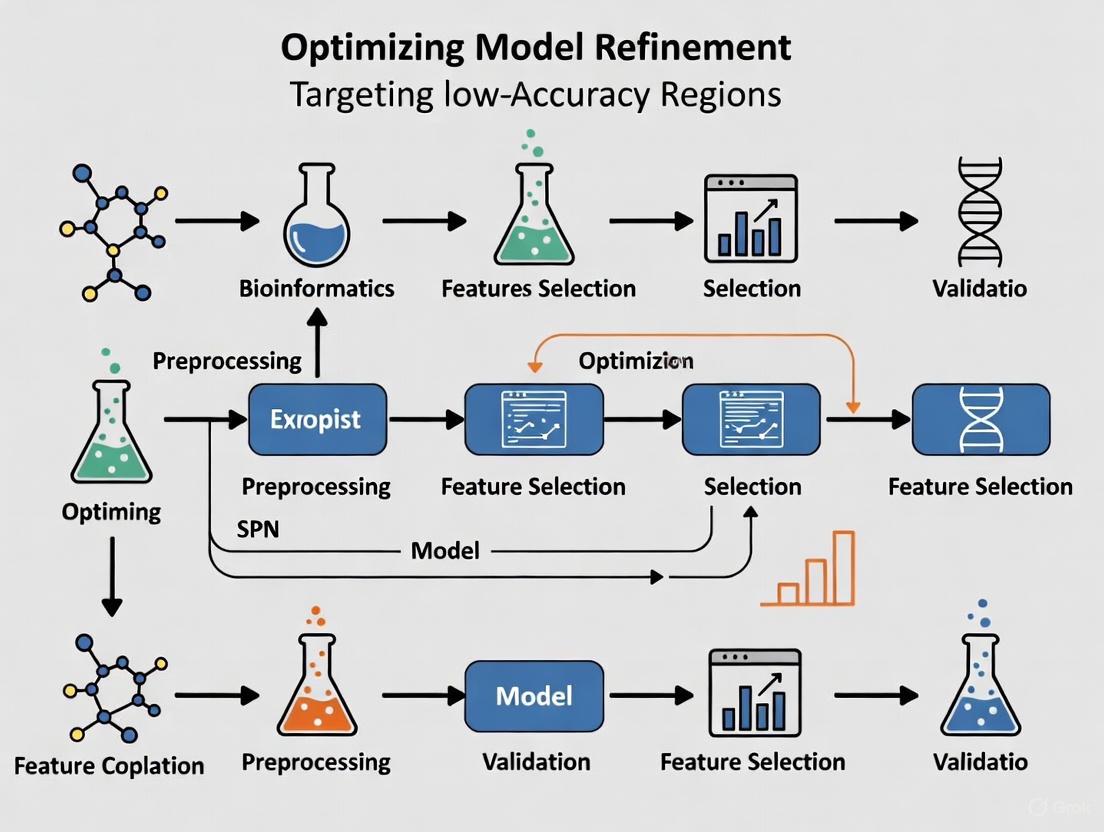

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: STAR-driven Drug Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Reagents

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | A label-free method for measuring target engagement of small molecules with their protein targets directly in intact cells and tissues under physiological conditions [3]. |

| Boolmore | A genetic algorithm-based tool that automates the refinement of Boolean network models to improve agreement with experimental perturbation-observation data [7]. |

| Open Targets Platform | An integrative platform that combines public domain data to associate drug targets with diseases and prioritize targets based on genetic, genomic, and chemical evidence [4]. |

| BioModels Database | A public repository of curated, annotated, and peer-reviewed computational models, used for model sharing, validation, and reproducibility checking [2]. |

| LIMS & ELN Software | Centralized data management systems (Laboratory Information Management System and Electronic Lab Notebook) that streamline experimental tracking, inventory management, and collaboration [8]. |

| Affinity Purification Reagents | Chemical tools (e.g., immobilized beads, photoaffinity labels, cross-linkers) for the biochemical purification and identification of small-molecule protein targets and off-targets [5]. |

FAQs on Data Quality and Model Refinement

How can I identify which data points are most harmful to my model's accuracy?

You can use data valuation frameworks to identify harmful data points. The Data Shapley method provides a principled framework to quantify the value of each training datum to the predictor performance, uniquely satisfying several natural properties of equitable data valuation [9]. It effectively identifies helpful or harmful data points for a learning algorithm, with low Shapley value data effectively capturing outliers and corruptions [9]. Influence functions offer another approach, tracing a model's prediction through the learning algorithm back to its training data, thereby identifying training points most responsible for a given prediction [9]. For practical implementation, ActiveClean supports progressive and iterative cleaning in statistical modeling while preserving convergence guarantees, prioritizing cleaning those records likely to affect the results [9].

What should I do when my experimental results don't match expected outcomes?

Follow a systematic troubleshooting protocol. First, repeat the experiment unless cost or time prohibitive, as you might have made a simple mistake [10]. Second, consider whether the experiment actually failed - consult literature to determine if there's another plausible reason for unexpected results [10]. Third, ensure you have appropriate controls - both positive and negative controls can help confirm the validity of your results [10]. Fourth, check all equipment and materials - reagents can be sensitive to improper storage, and vendors can send bad batches [10]. Finally, start changing variables systematically, isolating and testing only one variable at a time while documenting everything meticulously [10].

How do I address mechanistic uncertainty in biological research?

Mechanistic uncertainty presents special challenges, particularly when causal inference cannot be made and unmeasured confounding may explain observed associations [11]. In such cases, consider that relationships may not be causal, or mechanisms may be indirect rather than direct [11]. For example, in ultraprocessed food research, it's unclear whether associations with health outcomes stem from macronutrient profiles, specific processing techniques, or displacement of health-promoting dietary patterns [11]. The Bayesian synthesis (BSyn) method provides one solution, offering credible intervals for mechanistic models that typically produce only point estimates [12]. This approach is particularly valuable when environmental conditions change and empirical models may be of limited usefulness [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Data Quality Issues

Problem: Model performance is inconsistent or deteriorating despite apparent proper training procedures.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Run data attribution analysis: Use influence functions or Shapley values to identify problematic training points [9].

- Implement Confident Learning: Apply techniques to estimate uncertainty in dataset labels and characterize label errors [9].

- Check for data drift: Monitor whether incoming data maintains the same statistical properties as training data.

- Validate data preprocessing: Ensure consistency in normalization, handling of missing values, and feature engineering across training and deployment.

Solutions:

- Use ActiveClean for interactive data cleaning while preserving statistical modeling convergence guarantees [9].

- Apply Beta Shapley as a unified and noise-reduced data valuation framework to prioritize the most impactful data repairs [9].

- Establish automated data validation pipelines to detect anomalies before model retraining.

Guide 2: Addressing Mechanistic Uncertainty in Drug Development

Problem: Biological mechanisms underlying observed effects remain unclear, creating challenges for model refinement and validation.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Identify knowledge gaps: Map known mechanisms versus hypothesized pathways and their supporting evidence.

- Assess causal evidence: Distinguish between correlational relationships and established causal mechanisms.

- Evaluate alternative explanations: Systematically consider competing hypotheses that might explain observed results.

- Quantify uncertainty: Use Bayesian methods to provide credible intervals around mechanistic predictions [12].

Solutions:

- Implement Bayesian synthesis to quantify uncertainty in mechanistic models [12].

- Design targeted experiments to test specific mechanistic hypotheses rather than just outcome measures.

- Use model comparison frameworks to evaluate competing mechanistic explanations against experimental data.

- Apply sensitivity analysis to determine which uncertain parameters most affect model predictions.

Guide 3: Systematic Experimental Troubleshooting

Problem: Experiments produce unexpected results, high variance, or consistent failure despite proper protocols.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Apply the Pipettes and Problem Solving framework: This approach involves presenting unexpected experimental outcomes and systematically proposing new experiments to identify the source of problems [13].

- Categorize the problem type: Determine if it involves known outcomes returning atypical results (Type 1) or developing new assays/methods where the "right" outcome isn't known in advance (Type 2) [13].

- Consensus-driven hypothesis generation: Work collaboratively to reach consensus on proposed diagnostic experiments [13].

- Propose limited, sequential experiments: Typically limit to 2-3 proposed experiments before identifying the source of the problem [13].

Solutions:

- For Type 1 problems (atypical results with known expectations): Focus on fundamentals like appropriate controls, instrument calibration, and technique verification [13].

- For Type 2 problems (unknown right outcomes): Emphasize hypothesis development, proper controls, and new analytical techniques [13].

- Include seemingly mundane sources of error such as contamination, miscalibration, instrument malfunctions, and software bugs in your troubleshooting considerations [13].

- Document all troubleshooting steps meticulously for future reference and knowledge transfer [10].

Quantitative Error Analysis Framework

Table 1: Data Error Quantification Methods Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Shapley [9] | Equitable data valuation based on cooperative game theory | Satisfies unique fairness properties; identifies both helpful/harmful points | Computationally expensive for large datasets | Critical applications requiring fair data valuation; error analysis |

| Influence Functions [9] | Traces predictions back to training data using gradient information | Explains individual predictions; no model retraining needed | Theoretical guarantees break down on non-convex/non-differentiable models | Model debugging; understanding prediction behavior |

| Confident Learning [9] | Characterizes label errors using probabilistic thresholds | Directly estimates joint distribution between noisy and clean labels | Requires per-class probability estimates | Learning with noisy labels; dataset curation |

| Beta Shapley [9] | Generalizes Data Shapley by relaxing efficiency axiom | Noise-reduced valuation; more stable estimates | Recent method with less extensive validation | Noisy data environments; robust data valuation |

| ActiveClean [9] | Interactive cleaning with progressive validation | Preserves convergence guarantees; prioritizes impactful cleaning | Limited to convex loss models (linear regression, SVMs) | Iterative data cleaning; budget-constrained cleaning |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Protocol for Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Type | Example Scenario | Diagnostic Experiments | Common Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Variance Results [13] | MTT assay with very high error bars and unexpected values | Check negative controls; verify technique (e.g., aspiration method); test with known compounds | Improve technical consistency; adjust protocol steps; verify equipment calibration |

| Unexpected Negative Results [10] | Dim fluorescence in immunohistochemistry | Repeat experiment; check reagent storage and compatibility; test positive controls | Adjust antibody concentrations; verify reagent quality; optimize visualization settings |

| Mechanistic Uncertainty [11] | Observed associations without clear causal mechanisms | Design controlled experiments to test specific pathways; assess confounding factors | Bayesian synthesis methods; consider multiple mechanistic hypotheses; targeted validation |

| Systematic Measurement Error [14] | Consistent bias across all measurements | Calibration verification; instrument cross-checking; reference standard testing | Equipment recalibration; protocol adjustment; measurement technique refinement |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Error Reduction

| Reagent/Category | Function | Error Mitigation Role | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Controls [10] | Verify experimental system functionality | Identifies protocol failures versus true negative results | Should produce consistent, known response; validate regularly |

| Negative Controls [10] | Detect background signals and contamination | Distinguishes specific signals from non-specific binding | Should produce minimal/zero signal when properly implemented |

| Reference Standards | Calibrate instruments and measurements | Reduces systematic error in quantitative assays | Traceable to certified references; proper storage conditions |

| Validated Antibodies [10] | Specific detection of target molecules | Minimizes off-target binding and false positives | Verify host species, clonality, applications; check lot-to-lot consistency |

| Compatible Detection Systems [10] | Generate measurable signals from binding events | Ensures adequate signal-to-noise ratio | Confirm primary-secondary antibody compatibility; optimize concentrations |

Methodological Workflows

Data Error Identification Protocol

Data Error Identification and Mitigation Workflow

Systematic Experimental Troubleshooting

Systematic Experimental Troubleshooting Protocol

Mechanistic Uncertainty Resolution

Mechanistic Uncertainty Resolution Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Model Refinement

Q1: What is the primary challenge of manual model refinement in systems biology? Manual model refinement is a significant bottleneck because it relies on a slow, labor-intensive process of trial and error, constrained by domain knowledge. For instance, refining a Boolean model of ABA-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana took over two years of manual effort across multiple publications [7].

Q2: What is automated model refinement and how does it address this challenge?

Automated model refinement uses computational workflows, such as genetic algorithms, to systematically adjust a model's parameters to better agree with experimental data. Tools like boolmore can streamline this process, achieving accuracy gains that surpass years of manual revision by automatically exploring a space of biologically plausible models [7].

Q3: My model gets stuck in a local optimum during refinement. What can I do? Advanced optimization pipelines like DANTE address this by incorporating mechanisms such as local backpropagation. This technique updates visitation data in a way that creates a gradient to help the algorithm escape local optima, preventing it from repeatedly visiting the same suboptimal solutions [15].

Q4: How can I ensure my refined model generalizes well and doesn't overfit the training data?

Benchmarking is crucial. Studies with boolmore showed that refined models improved their accuracy on a validation set from 47% to 95% on average, demonstrating that proper algorithmic refinement enhances predictive power without overfitting [7]. Using a hold-out validation set is a standard practice to test generalizability.

Q5: What kind of data is needed for automated refinement with a tool like boolmore?

The primary input is a compilation of curated perturbation-observation pairs. These are individual experimental results that describe the state of a biological node under specific conditions, such as a knockout or stimulus. This is common data in traditional functional biology, making the method suitable even without high-throughput datasets [7].

Quantitative Data on Refinement Performance

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from the boolmore case study, demonstrating its effectiveness against manual methods [7].

| Metric | Starting Model (Manual) | Refined Model (boolmore) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set Accuracy (Average) | 49% | 99% | Accuracy on the set of experimental data used for refinement. |

| Validation Set Accuracy (Average) | 47% | 95% | Accuracy on a held-out set of experiments, demonstrating improved generalizability. |

| Time to Achieve Refinement | ~2 years (manual revisions) | Automated workflow | The manual process spanned publications from 2006 to 2018-2020. |

| Key Improvement in ABA Stomatal Closure | Baseline | Surpassed manual accuracy gain | The refined model agreed significantly better with a compendium of published results. |

Experimental Protocol: TheboolmoreWorkflow

The following is a detailed methodology for refining a Boolean model using the boolmore genetic algorithm-based workflow [7].

Input Preparation:

- Starting Model: Provide the initial Boolean model, including its interaction graph and regulatory functions.

- Biological Constraints: Define known biological mechanisms as logical relations (e.g., "A is necessary for B").

- Experimental Compendium: Curate a set of perturbation-observation pairs, categorizing observations (e.g., OFF, ON, "Some").

Model Mutation:

- The algorithm generates new candidate models ("offspring") by mutating the regulatory functions of the starting model.

- Mutations are constrained to preserve the original interaction graph's structure and signs, and to respect the user-provided biological constraints. Regulations can be deleted and later recovered.

Prediction Generation:

- For each candidate model, calculate its long-term behaviors (minimal trap spaces) under each experimental setting defined in the perturbation-observation pairs.

- Determine the predicted state (ON, OFF, or oscillating) for each node.

Fitness Scoring:

- Compute a fitness score for each model by quantifying its agreement with the experimental compendium.

- Scoring is hierarchical; to score well on a double perturbation experiment, the model must also agree with the constituent single perturbations.

Selection and Iteration:

- Retain the models with the top fitness scores, with a preference for models with fewer added edges.

- Repeat the steps of mutation, prediction, and selection for multiple generations to evolve an optimized model.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Automated Model Refinement Workflow

Simplified ABA Stomatal Closure Signaling Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and biological tools used in automated model refinement, as featured in the case study and related research [7] [15].

| Item Name | Type | Function in Refinement |

|---|---|---|

boolmore Tool |

Software Workflow | A genetic algorithm-based tool that refines Boolean models to better fit perturbation-observation data [7]. |

| Perturbation-Observation Pairs | Curated Data | A compiled set of experiments that serve as the ground truth for scoring and training model candidates [7]. |

| Deep Active Optimization (DANTE) | Optimization Pipeline | An AI pipeline that uses a deep neural surrogate and tree search to find optimal solutions in high-dimensional problems with limited data [15]. |

| Minimal Trap Space Calculator | Computational Method | Used to determine the long-term behavior (e.g., ON/OFF states) of a Boolean model under specific conditions for prediction [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Dose Optimization

1. What is Project Optimus and why was it initiated? Project Optimus is an initiative launched by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Oncology Center of Excellence in 2021. Its mission is to reform the dose-finding and dose selection paradigm in oncology drug development. It was initiated due to a growing recognition that conventional methods for determining the best dose of a new agent are inadequate. These older methods often identify unnecessarily high doses for modern targeted therapies and immunotherapies, leading to increased toxicity without added benefit for patients [16] [17].

2. What are the main limitations of conventional dose-finding methods like the 3+3 design? Conventional methods, such as the 3+3 design, have several critical flaws:

- Ignores Efficacy: They select a dose based primarily on short-term toxicity (Maximum Tolerated Dose, or MTD) and ignore whether the drug is actually effective at treating cancer [16] [17].

- Poorly Suited for Modern Therapies: They were designed for cytotoxic chemotherapies and rely on the assumption that both toxicity and efficacy always increase with dose. This is often not true for targeted therapies, where efficacy may plateau while toxicity continues to rise [16].

- Short-Term Focus: They evaluate toxicity over very short periods (e.g., one to two cycles), which does not reflect the reality of patients staying on modern therapies for months or years, leading to issues with cumulative or late-onset toxicities [16].

- High Failure Rate: Studies show that nearly 50% of patients on late-stage trials for targeted therapies require dose reductions, and the FDA has required additional studies to re-evaluate the dosing for over 50% of recently approved cancer drugs [17].

3. What are model-informed approaches in dose optimization? Model-informed approaches use mathematical and statistical models to integrate and analyze all available data to support dose selection. Key approaches include [18]:

- Exposure-Response Modeling: Determines the relationship between drug exposure in the body and its safety and efficacy outcomes.

- Population Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling: Describes how drug concentrations vary in different patients and can be used to select dosing regimens that achieve target exposure levels.

- Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP): Incorporates biological mechanisms to understand and predict a drug's effects with limited clinical data. These models can predict outcomes for doses not directly tested and help identify an optimized dose with a better benefit-risk profile [18].

4. What are adaptive or seamless trial designs? Traditional drug development has separate trials for distinct stages (Phase 1, 2, and 3). Adaptive or seamless designs combine these various phases into a single trial [17] [19]. For example, an adaptive Phase 2/3 design might test multiple doses in Stage 1, then select the most promising dose to continue into Stage 2 for confirmatory testing. This allows for more rapid enrollment, faster decision-making, and the accumulation of more long-term safety and efficacy data to better inform dosing decisions [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios in Dose Optimization

Scenario 1: High Rates of Dose Modification in Late-Stage Trials

Problem: A high percentage of patients in a registrational trial require dose reductions, interruptions, or discontinuations due to intolerable side effects [17].

| Investigation Step | Action | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Analyze Data | Review incidence of dosage modifications, long-term toxicity data, and patient-reported outcomes from early trials [18]. | Identify the specific toxicities causing modifications and their relationship to drug exposure. |

| Model Exposure-Response | Perform exposure-response (ER) modeling to link drug exposure (e.g., trough concentration) to the probability of key adverse events [18]. | Quantify the benefit-risk trade-off for different dosing regimens. |

| Evaluate Lower Doses | Use the ER model to simulate the potential safety profile of lower doses or alternative schedules (e.g., reduced frequency). | Determine if a lower dose maintains efficacy while significantly improving tolerability. |

| Consider Randomized Evaluation | If feasible, initiate a randomized trial comparing the original high dose with the optimized lower dose to confirm the improved benefit-risk profile [16]. | Generate high-quality evidence for dose selection as encouraged by Project Optimus [16]. |

Scenario 2: Efficacy Plateau with Increasing Dose

Problem: Early clinical data suggests that the anti-cancer response (e.g., tumor shrinkage) reaches a maximum at a certain dose level, but toxicity continues to increase at higher doses [16].

| Investigation Step | Action | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Identify Efficacy Plateau | Analyze dose-response data for efficacy endpoints (e.g., Overall Response Rate) and safety endpoints (e.g., Grade 3+ adverse events) [18]. | Visually confirm the plateau effect and identify the dose where it begins. |

| Integrate Pharmacodynamic Data | Incorporate data on target engagement or pharmacodynamic biomarkers. For example, assess if the dose at which target saturation occurs aligns with the efficacy plateau [17]. | Understand the biological basis for the plateau and identify a biologically optimal dose. |

| Apply Clinical Utility Index (CUI) | Use a CUI framework to quantitatively combine efficacy and safety data into a single score for each dose level [17]. | Objectively compare doses and select the one that offers the best overall value. |

| Select Optimized Dose | Choose the dose that provides near-maximal efficacy with a significantly improved safety profile compared to the MTD. | Avoid the "false economy" of selecting an overly toxic dose that provides no additional patient benefit [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Dose Optimization Analyses

Protocol 1: Exposure-Response Analysis for Safety

Objective: To characterize the relationship between drug exposure and the probability of a dose-limiting toxicity to inform dose selection.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Patient PK/PD Data: Collected plasma concentration-time data from your First-in-Human trial.

- Safety Data: Graded adverse event data, standardized using CTCAE criteria.

- Population PK Model: A model describing the typical population pharmacokinetics of your drug and sources of variability.

- Software: Non-linear mixed-effects modeling software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix, R).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Merge individual patient exposure metrics (e.g., predicted trough concentration or area under the curve from the population PK model) with the corresponding safety event data (e.g., occurrence of a severe adverse event over a defined period) [18].

- Model Development: Use logistic regression or time-to-event modeling to relate the exposure metric to the probability (or hazard) of the safety event.

- Model structure:

Logit(P(Event)) = β0 + β1 * Exposure - Where P(Event) is the probability of the adverse event, and β1 represents the steepness of the exposure-response relationship [18].

- Model structure:

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model's goodness-of-fit using diagnostic plots and visual predictive checks to ensure it adequately describes the observed data.

- Simulation: Use the validated model to simulate the probability of the adverse event across a range of potential doses and dosing regimens [18].

- Decision-Making: Compare the simulated safety profiles to identify doses with an acceptable risk level.

Protocol 2: Clinical Utility Index (CUI) for Dose Selection

Objective: To integrate multiple efficacy and safety endpoints into a single quantitative value to rank and compare different dose levels.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Efficacy & Safety Data: Key efficacy (e.g., ORR, PFS) and safety (e.g., rate of specific AEs, dose intensity) metrics for each dose level.

- Stakeholder Input: Pre-defined weights reflecting the relative importance of each endpoint (e.g., from clinicians, patients, regulators).

- Computational Tool: Spreadsheet software or statistical software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Define Endpoints and Weights: Select the critical efficacy and safety endpoints to include in the index. Assign a weight to each endpoint based on stakeholder input, ensuring the sum of all weights is 1 [17].

- Normalize Endpoint Values: Rescale the raw data for each endpoint to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1, where 1 is most desirable). For efficacy, higher values are better; for safety (toxicity), lower values are better, so normalization may need to be inverted.

- Calculate CUI: For each dose level, calculate the CUI using a linear additive model:

CUI_Dose = [Weight_E1 * Normalized_E1] + [Weight_E2 * Normalized_E2] + ... + [Weight_S1 * (1 - Normalized_S1)] + ...- Where E represents efficacy endpoints and S represents safety endpoints [17].

- Rank and Select: Rank the dose levels based on their CUI scores. The dose with the highest CUI represents the best balance of efficacy and safety according to the pre-defined criteria.

Research Reagent Solutions for Dose Optimization

| Item | Function in Dose Optimization |

|---|---|

| Population PK Modeling | Describes the typical drug concentration-time profile in a population and identifies sources of variability (e.g., due to organ function, drug interactions) to support fixed vs. weight-based dosing and dose adjustments [18]. |

| Exposure-Response Modeling | Correlates drug exposure metrics with changes in clinical endpoints (safety or efficacy) to predict the outcomes of untested dosing regimens and understand the therapeutic index [18]. |

| Clinical Utility Index (CUI) | Provides a quantitative and collaborative framework to integrate multiple data types (efficacy, safety, PK) to determine the dose with the best overall benefit-risk profile [17]. |

| Backfill/Expansion Cohorts | Enrolls additional patients at specific dose levels of interest within an early-stage trial to strengthen the understanding of that dose's benefit-risk ratio [17]. |

| Adaptive Seamless Trial Design | Combines traditionally distinct trial phases (e.g., Phase 2 and 3) into one continuous study, allowing for dose selection based on early data and more efficient confirmation of the chosen dose [17] [19]. |

Workflow Diagrams for Dose Optimization Strategies

Diagram 1: Model-Informed Dose Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting High Toxicity with Exposure-Response

In the landscape of modern drug development, 'Fit-for-Purpose' (FFP) models represent a paradigm shift in how computational and quantitative approaches are integrated into regulatory decision-making. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines the FFP initiative as a pathway for regulatory acceptance of dynamic tools for use in drug development programs [20]. These models are not one-size-fits-all solutions; rather, they are specifically developed and tailored to answer precise questions of interest (QOI) within a defined context of use (COU) at specific stages of the drug development lifecycle [21].

The imperative for FFP models stems from the need to improve drug development efficiency and success rates. Evidence demonstrates that a well-implemented FFP approach can significantly shorten development cycle timelines, reduce discovery and trial costs, and provide better quantitative risk estimates amidst development uncertainties [21]. As drug modalities become more complex and therapeutic targets more challenging, the strategic application of FFP models provides a structured, data-driven framework for evaluating safety and efficacy throughout the entire drug development process, from early discovery to post-market surveillance.

The Scientific Framework for FFP Model Development

Core Principles and Regulatory Alignment

FFP model development operates under several core principles that ensure regulatory alignment and scientific rigor. A model is considered FFP when it successfully defines the COU, ensures data quality, and undergoes proper verification, calibration, validation, and interpretation [21]. Conversely, a model fails to be FFP when it lacks a clearly defined COU, utilizes poor quality data, or suffers from unjustified oversimplification or unnecessary complexity.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has expanded its guidance to include MIDD, specifically the M15 general guidance, promoting global harmonization in model application [21]. This standardization improves consistency among global sponsors applying FFP models in drug development and regulatory interactions, potentially streamlining processes worldwide. Regulatory agencies emphasize that FFP tools must be "reusable" or "dynamic" in nature, capable of adapting to multiple disease areas or development scenarios, as demonstrated by successful applications in dose-finding and patient drop-out modeling across various therapeutic areas [21].

Structured Troubleshooting for Model Optimization

When FFP models underperform, particularly with low-accuracy targets, researchers require systematic troubleshooting methodologies. Adapted from proven laboratory troubleshooting frameworks [22], the following workflow provides a structured approach to diagnosing and resolving model deficiencies:

Figure 1. Systematic troubleshooting workflow for optimizing low-accuracy FFP models.

This troubleshooting methodology emphasizes iterative refinement and validation, ensuring that model optimizations directly address root causes of inaccuracy while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Technical Support Center: FFP Model Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on FFP Model Refinement

Q: What are the primary causes of low accuracy in target localization and quantification for FFP models, and how can they be diagnosed?

Low accuracy in target localization often stems from multiple factors, including uncertainties in model structure, inaccurate parameter estimations, and challenges in model construction that account for both mobility and localization constraints [23] [24]. Diagnosis should begin with residual error analysis to identify systematic biases, followed by parameter identifiability assessment using profile likelihood or Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. For long-distance target localization issues specifically, researchers have implemented pruning operations and silhouette coefficient calculations based on multiple target relative coordinates to efficiently identify clusters near true relative coordinates [24].

Q: How can we improve coordinate fusion accuracy in multi-target FFP models?

Advanced clustering algorithms can significantly enhance coordinate fusion accuracy. Research demonstrates that improved hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN) algorithms effectively fuse relative coordinates of multiple targets [23] [24]. The implementation involves introducing a pruning operation and silhouette coefficient calculation based on multiple target relative coordinates, which efficiently identifies clusters near the true relative coordinates of targets, thereby improving coordinate fusion effectiveness [24]. This approach has maintained relative localization error within 4% and absolute localization error within 6% for static targets at distances ranging from 100 to 500 meters in robotics applications, with similar principles applying to pharmacological target localization [24].

Q: What optimization algorithms show the most promise for refining path planning in adaptive FFP models?

Double deep Q-networks (DDQN) with reward strategies based on coordinate fusion error have demonstrated significant improvements in positioning accuracy for long-distance targets [23] [24]. Successful implementation involves developing an experience replay buffer that includes state information such as grid centers and estimated target coordinates, constructing behavior and target networks, and designing appropriate loss functions [24]. For drug development applications, this translates to creating virtual population simulations that adaptively explore parameter spaces, with reward functions aligned with precision metrics rather than mere convergence.

Q: How does the FDA's FFP initiative impact model selection and validation requirements?

The FDA's FFP initiative provides a pathway for regulatory acceptance of dynamic tools that may not have formal qualification [20]. A drug development tool (DDT) is deemed FFP based on the acceptance of the proposed tool following thorough evaluation of submitted information. This evaluation publicly determines the FFP designation to facilitate greater utilization of these tools in drug development programs [20]. The practical implication is that researchers must clearly document the COU, QOI, and model validation strategies that demonstrate fitness for their specific purpose, as exemplified by approved FFP tools in Alzheimer's disease and dose-finding applications [20].

Q: What are the consequences of using non-FFP models in regulatory submissions?

Non-FFP models risk regulatory rejection due to undefined COU, poor data quality, inadequate model verification, or unjustified incorporation of complexities [21]. Specifically, oversimplification that eliminates critical biological processes, or conversely, unnecessary complexity that cannot be supported by available data, renders models unsuitable for regulatory decision-making. Additionally, machine learning models trained on specific clinical scenarios may not be FFP for predicting different clinical settings, leading to extrapolation errors and regulatory concerns [21].

Advanced Optimization Methodologies for Low-Accuracy Targets

Enhanced Sensing and Positioning Algorithms

Robotics research provides transferable methodologies for improving target localization accuracy in pharmacological models. One advanced approach involves dividing the movement area into hexagonal grids and introducing constraints on stopping position selection and non-redundant locations [24]. Based on image parallelism principles, researchers have developed methods for calculating the relative position of targets using sensing information from two positions, significantly improving long-distance localization precision [23]. These techniques can be adapted to improve the accuracy of physiological compartment identification in PBPK models and target engagement quantification in QSP models.

Integrated Residual Attention Units for Feature Extraction

For complex remote sensing image change detection, researchers have developed Integrated Residual Attention Units (IRAU) that optimize detection accuracy through ResNet variants, Split and Concat (SPC) modules, and channel attention mechanisms [25]. These units extract semantic information from feature maps at various scales, enriching and refining the feature information to be detected. In one application, this approach improved accuracy from 0.54 to 0.97 after training convergence, with repeated detection accuracy ranging from 95.82% to 99.68% [25]. Similar architectures can enhance feature detection in pharmacological models dealing with noisy or complex biological data.

Depth-wise Separable Convolution for Real-time Processing

Depth-wise Separable Convolution (DSC) modules significantly optimize processing efficiency while maintaining accuracy [25]. When combined with attention mechanisms, these modules reduce computational complexity and latency, crucial for real-time applications and large-scale simulations. In benchmark tests, removing DSC modules increased latency by 117ms while decreasing accuracy by 1.91% [25]. For large virtual population simulations in drug development, implementing similar efficient processing architectures can enable more extensive sampling and faster iteration cycles.

Quantitative Performance Data for FFP Model Optimization

Table 1. Comparative performance metrics of optimization algorithms for target localization

| Algorithm | Relative Localization Error | Absolute Localization Error | Optimal Path Identification | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTLO [24] | <4% | <6% | Yes | Long-distance static targets (100-500m) |

| Traditional Monocular Visual Localization (TMVL) [24] | >4% | >6% | Limited | Short-distance dynamic targets |

| Monocular Global Geolocation (MGG) [24] | Higher than LTLO | Higher than LTLO | Partial | Intermediate distance with GPS |

| Long-range Binocular Vision Target Geolocation (LRBVTG) [24] | Higher than LTLO | Higher than LTLO | No | Specific distance ranges |

Table 2. Accuracy optimization results with advanced architectural components

| Model Component | Performance Improvement | Training Impact | Latency Effect | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Residual Attention Unit (IRAU) [25] | Accuracy increased from 0.54 to 0.97 | Faster convergence | Moderate increase | High (requires specialized architecture) |

| Depth-wise Separable Convolution (DSC) [25] | 1.91% accuracy improvement | Standard convergence | 117ms reduction | Medium (modification of existing layers) |

| Improved HDBSCAN Algorithm [24] | Relative error <4%, Absolute error <6% | Requires coordinate fusion training | Minimal increase | Medium (clustering implementation) |

| Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) [24] | Optimal path identification | Requires extensive training | Initial high computational load | High (reinforcement learning setup) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Improved HDBSCAN for Coordinate Fusion

Purpose: To enhance coordinate fusion accuracy in multi-target FFP models using an improved HDBSCAN algorithm.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-dimensional parameter estimation data

- Computational environment (Python/R/MATLAB)

- HDBSCAN library with custom modifications

- Validation dataset with known ground truth

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile relative coordinates from multiple target estimations into a feature matrix.

- Pruning Operation: Implement silhouette coefficient-based pruning to eliminate outlier coordinates that fall outside acceptable confidence intervals.

- Cluster Identification: Apply modified HDBSCAN algorithm with constraints tailored to the specific target topology.

- Coordinate Fusion: Calculate weighted centroids of identified clusters, giving higher weights to coordinates with lower estimated variance.

- Validation: Compare fused coordinates against ground truth using standardized error metrics.

Validation Metrics: Relative localization error (<4% target), absolute localization error (<6% target), and cluster stability across multiple iterations [24].

Protocol 2: DDQN with Experience Replay for Path Optimization

Purpose: To implement a reinforcement learning approach for optimizing model exploration strategies in parameter space.

Materials and Reagents:

- State definition of model parameters and targets

- Reward function framework

- DDQN implementation framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- Experience replay buffer infrastructure

Procedure:

- State Representation: Define state information including current parameter estimates, target coordinates, and uncertainty metrics.

- Reward Function Design: Create a reward strategy based on coordinate fusion error reduction rather than absolute accuracy.

- Network Architecture: Construct separate behavior and target networks with identical architecture but different update frequencies.

- Experience Replay: Implement prioritized experience replay that stores state transitions and associated rewards.

- Training Cycle: Iterate through action selection, reward calculation, experience storage, and model updates until convergence.

Validation Metrics: Path efficiency improvement, reduction in target localization error, and training stability [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for FFP Model Development

Table 3. Essential computational tools for FFP model optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in FFP Development | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Platforms [21] | GastroPlus, Simcyp Simulator | Mechanistic modeling of drug disposition incorporating physiology and product quality | FDA FFP designation available for specific COUs |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Frameworks [21] | DILIsym, ITCsym | Integrative modeling combining systems biology with pharmacology for mechanism-based predictions | Requires comprehensive validation and biological plausibility documentation |

| Population PK/PD Tools [21] | NONMEM, Monolix, R/nlme | Explain variability in drug exposure and response among individuals in a population | Well-established regulatory precedent with standardized submission requirements |

| AI/ML Platforms [21] | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Analyze large-scale biological and clinical datasets for pattern recognition and prediction | Emerging regulatory framework with emphasis on reproducibility and validation |

| First-in-Human (FIH) Dose Algorithm Tools [21] | Allometric scaling, QSP-guided prediction | Determine starting dose and escalation scheme based on preclinical data | High regulatory scrutiny requiring robust safety margins and justification |

The strategic development and refinement of 'Fit-for-Purpose' models represents a critical advancement in model-informed drug development. By applying systematic troubleshooting methodologies, leveraging advanced optimization algorithms from complementary fields, and maintaining alignment with regulatory expectations through the FDA's FFP initiative, researchers can significantly enhance model accuracy and reliability for challenging targets. The integration of approaches such as improved HDBSCAN clustering, DDQN path optimization, and architectural improvements like IRAU and DSC modules provides a robust toolkit for addressing the persistent challenge of low-accuracy targets in pharmacological modeling. As the field evolves, continued emphasis on methodological rigor, comprehensive validation, and regulatory communication will ensure that FFP models fulfill their potential to accelerate therapeutic development and improve patient outcomes.

From Data to Discovery: Modern Methodologies for Effective Model Refinement

What is boolmore and what is its primary function? boolmore is an open-source, genetic algorithm (GA)-based workflow designed to automate the refinement of Boolean models of biological networks. Its primary function is to adjust the Boolean functions of an existing model to improve its agreement with a corpus of curated experimental data, formatted as perturbation-observation pairs. This process, which traditionally requires manual trial-and-error, is streamlined by boolmore, which efficiently searches the space of biologically plausible models to find versions with higher accuracy [7] [26].

What are the core biological concepts behind the models boolmore refines? boolmore works on Boolean models, which are a type of discrete dynamic model used to represent biological systems like signal transduction networks. In these models [7]:

- Nodes represent biological components (e.g., proteins).

- Edges represent causal interactions between them (e.g., activation or inhibition).

- Node States are either 0 (OFF/inactive) or 1 (ON/active).

- Regulatory Functions are Boolean rules (using AND, OR, NOT) that determine a node's state based on its regulators.

- Long-term behavior is analyzed through minimal trap spaces (or quasi-attractors), which represent the stable patterns of activity the system can settle into.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table details the key "research reagents" – the core inputs, software, and knowledge required – to run a boolmore experiment successfully.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for boolmore Experiments

| Item Name | Type | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Boolean Model | Input Model | The initial network (interaction graph and Boolean rules) to be refined. Serves as the baseline and constrains the search space [7]. |

| Perturbation-Observation Pairs | Input Data | A curated compendium of experimental results. Each pair describes the observed state of a node under a specific perturbation context (e.g., a knockout) [7]. |

| Biological Mechanism Constraints | Input Knowledge | Logical relations (e.g., "A is necessary for B") provided by the researcher to ensure evolved models remain biologically plausible [7]. |

| CoLoMoTo Software Suite | Software Environment | An integrated Docker container or Conda environment that provides access to over 20 complementary tools for Boolean model analysis, ensuring reproducibility [27]. |

| GINsim | Software Tool | Used within the CoLoMoTo suite to visualize and edit the network structure and logical rules of the Boolean model [27]. |

| bioLQM & BNS | Software Tools | Tools within the CoLoMoTo suite used for attractor analysis, which is crucial for generating model predictions to compare against experimental data [27]. |

boolmore Workflow and Experimental Protocol

The boolmore refinement process follows a structured, iterative workflow. The diagram below illustrates the key stages from initial setup to final model analysis.

Detailed Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Input Preparation

- Obtain your Starting Boolean Model in a supported format (e.g., SBML-qual). The model's interaction graph should be biologically reasonable, though it may be missing some edges [7].

- Curate your Perturbation-Observation Pairs from experimental literature. Categorize observations (e.g., OFF, ON, "Some" activity) and organize perturbations hierarchically (e.g., single then double knockouts) for accurate scoring [7].

- Define Biological Constraints as logical statements to limit the algorithm's search to functionally plausible models [7].

Algorithm Execution and Configuration

- Initialize the genetic algorithm. boolmore will create the first generation of models by applying mutation and crossover operators to the starting model's Boolean functions, while respecting your constraints and the interaction graph [7].

- For each new model (offspring), boolmore performs fitness scoring. It calculates the model's minimal trap spaces under each perturbation setting and compares the predictions to your experimental pairs. The score reflects the degree of agreement [7].

- The models with the top fitness scores are selected to produce the next generation. This cycle repeats for a predefined number of generations or until convergence [7].

Output and Validation

- The primary output is one or more Refined Boolean Models with higher accuracy against the training data.

- Crucially, these models should be validated against a hold-out validation set of experimental data not used during refinement to ensure the model has not overfitted and possesses predictive power [7].

- Analyze the refined model's structure and dynamics to generate new, testable predictions for experimental validation [7].

Performance Benchmarking and Data

In-silico benchmarks on a suite of 40 biological models demonstrated boolmore's effectiveness. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance gains.

Table 2: boolmore Benchmark Performance on 40 Biological Models

| Model Set | Starting Model Average Accuracy | Refined Model Average Accuracy | Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set (80% of data) | 49% | 99% | +50 percentage points |

| Validation Set (20% of data) | 47% | 95% | +48 percentage points |

This data shows that boolmore can dramatically improve model accuracy without overfitting, as evidenced by the high performance on the unseen validation data [7].

Integration with Analysis Workflows

boolmore operates within a broader ecosystem of model analysis tools. The diagram below shows how it fits into a reproducible workflow using the CoLoMoTo software suite.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

My refined model has high accuracy on the training data but performs poorly on new perturbations. What went wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting. Your model may have become overly specialized to the specific experiments in your training set.

- Solution: Ensure you are using a hold-out validation set (data not used for refinement) to monitor performance during the process. Increase the stringency of your biological constraints to limit the algorithm's search to a more plausible model space. You may also need to adjust GA parameters like population size or mutation rate to encourage broader exploration [7].

The algorithm isn't converging on a high-fitness model. How can I improve the search?

- Solution: First, verify the quality and consistency of your perturbation-observation pairs. Inconsistent data can confuse the fitness function. Second, review your biological constraints; they might be too restrictive. Consider allowing the algorithm to add interactions from a user-provided pool of potential edges if the starting network is incomplete. Finally, you can tune GA parameters like mutation probability or the number of models per generation [7].

How do I handle experimental observations that are not simply ON or OFF?

- Solution: boolmore supports an intermediate category, labeled "Some", to represent observations of an intermediate level of activation. You can incorporate these into your data compilation. The scoring function can be configured to handle this category appropriately, giving partial credit for predictions that match this intermediate state [7].

Can I use boolmore for lead optimization in drug discovery?

- Answer: While boolmore itself refines network models, the genetic algorithm approach is directly applicable to drug design. Tools like AutoGrow4 use a very similar GA workflow for de novo drug design and lead optimization. They start with seed molecules and use crossover and mutation operators to evolve new compounds with better predicted binding affinity to a protein target [28]. The core concepts of using a GA to optimize a complex model against a fitness score are directly transferable.

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is my decision tree model for genomic variant analysis encountering memory errors?

The most likely cause is that the analysis includes genes with an unusually high number of variants or particularly long genes, which demand significant memory during aggregation steps. Examples of such problematic genes include RYR2 (ENSG00000198626) and SCN5A (ENSG00000183873) [29].

To resolve this, increase the memory allocation in your workflow configuration files. The following table summarizes the recommended changes for the quick_merge.wdl file [29]:

Table: Recommended Memory Adjustments in quick_merge.wdl

| Task | Parameter | Default | Change to |

|---|---|---|---|

split |

memory |

1 GB | 2 GB |

first_round_merge |

memory |

20 GB | 32 GB |

second_round_merge |

memory |

10 GB | 48 GB |

Similarly, adjustments are needed in the annotation.wdl file [29]:

Table: Recommended Memory Adjustments in annotation.wdl

| Task | Parameter | Default | Change to |

|---|---|---|---|

fill_tags_query |

memory allocation |

2 GB | 5 GB |

annotate |

memory allocation |

1 GB | 5 GB |

sum_and_annotate |

memory allocation |

5 GB | 10 GB |

FAQ 2: What could cause a high number of haploid calls (ACHemivariant > 0) for a gene located on an autosome?

For autosomal variants, the majority of samples will have diploid genotypes (e.g., 0/1). However, some samples may exhibit haploid (hemizygous-like) calls (e.g., 1) for specific variants [29].

This typically indicates that the variant call is located within a known deletion on the homologous chromosome for that sample. These haploid calls are not produced during aggregation but are already present in the input single-sample gVCFs [29].

Worked Example: In a single-sample gVCF, you might observe a haploid ALT call for a variant (e.g., chr1:2118756 A>T with genotype '1'). This occurs because a heterozygous deletion (e.g., chr1:2118754 TGA>T with genotype '0/1') is located upstream, spanning the position of the A>T SNP. The SNP is therefore called as haploid because it resides within the deletion on one chromosome [29].

FAQ 3: Why do my variant classifications conflict with public databases like ClinVar, and how can I resolve this?

Conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity (COIs) are a common challenge. A 2024 study found that 5.7% of variants in ClinVar have conflicting interpretations, and 78% of clinically relevant genes harbor such variants [30]. Discrepancies often arise from several factors [31]:

- Differences in classification methods: Use of different guidelines (e.g., ACMG/AMP vs. Sherloc) or gene-specific modifications.

- Differences in application of methods: Subjectivity in applying evidence categories (e.g., PS3/BS3 for functional data or BS1 for population frequency).

- Differences in evidence: Inconsistent access to the latest medical literature or internal clinical data.

- Differences in interpreter opinions: Subjective judgment, especially for variants associated with rare diseases.

Resolution Strategy: Collaboration and evidence-sharing between clinical laboratories and researchers can resolve a significant portion of these discrepancies. Ensuring all parties use the same classification guidelines, data sources, and versions is a critical first step [31].

FAQ 4: What are the key performance metrics for optimized decision tree models in pattern recognition, and how do they compare to other models?

Optimized decision tree models, such as those combining Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, can achieve high accuracy. The following table compares the performance of an optimized decision tree with other common algorithms from a 2025 study on pattern recognition [32]:

Table: Algorithm Performance Comparison for Pattern Recognition

| Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Model Size (MB) | Memory Usage (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Decision Tree | 94.9 | 50 | 300 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 87.0 | 45 | Not Specified |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 92.0 | 200 | 800 |

| XGBoost | 94.6 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| LightGBM | 94.7 | 48 | Not Specified |

| CatBoost | 94.5 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Quality and Model Performance

Problem: The model's predictions are inaccurate or nonsensical, potentially due to underlying data issues.

This is a classic "Garbage In, Garbage Out" (GIGO) scenario. In bioinformatics, the quality of input data directly dictates the quality of the analytical results. Up to 30% of published research may contain errors traceable to data quality issues at the collection or processing stage [33].

Solution: Implement a multi-layered data quality control strategy.

Table: Common Data Pitfalls and Prevention Strategies

| Pitfall | Description | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Mislabeling | Incorrect tracking of samples during collection, processing, or analysis. | Implement rigorous sample tracking systems (e.g., barcode labeling) and regular identity verification using genetic markers [33]. |

| Technical Artifacts | Non-biological signals from sequencing (e.g., PCR duplicates, adapter contamination). | Use tools like Picard and Trimmomatic to identify and remove artifacts before analysis [33]. |

| Batch Effects | Systematic differences between sample groups processed at different times or locations. | Employ careful experimental design and statistical methods for batch effect correction [33]. |

| Contamination | Presence of foreign genetic material (e.g., cross-sample, bacterial). | Process negative controls alongside experimental samples to identify contamination sources [33]. |

Detailed Methodology for Data Validation:

- Standardized Protocols (SOPs): Develop and adhere to detailed, validated SOPs for every data handling step, from tissue sampling to sequencing, following standards from organizations like the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) [33].

- Quality Control Metrics: Establish thresholds for key metrics. For next-generation sequencing, use tools like FastQC to monitor base call quality scores (Phred scores), read length distributions, and GC content [33].

- Data Validation: Ensure data makes biological sense by checking for expected patterns (e.g., gene expression profiles matching known tissue types). Employ cross-validation using alternative methods (e.g., confirming a variant from WGS with targeted PCR) [33].

- Version Control and Reproducibility: Use systems like Git to track changes to datasets and analysis workflows. Utilize workflow managers like Nextflow or Snakemake to ensure all processing steps are documented and reproducible [33].

Experimental Protocol: Building an Optimized Decision Tree Model for Variant Analysis

This protocol details the methodology for creating a high-accuracy decision tree model, adapted from a 2025 study on pattern recognition [32].

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Data Source: Collect genomic data from high-precision sources. This may include key parameters such as allele counts, read depth, and functional prediction scores.

- Data Preprocessing: Perform data cleaning steps, including denoising and standardization, to ensure data quality and consistency. Handle missing data and normalize features as necessary [32].

2. Model Training with Adaptive Hyperparameter Tuning

- Algorithm Selection: Combine the advantages of ensemble methods like Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting Tree (GBT). RF enhances stability by integrating multiple trees, while GBT finely adjusts predictions through sequential optimization [32].

- Adaptive Feature Selection: The algorithm should adaptively select the most informative features (genomic annotations) to improve recognition of different variant classes and reduce overfitting [32].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Use grid search to identify the optimal set of hyperparameters. Perform this within a cross-validation framework to ensure robust model selection and avoid overfitting [32].

3. Model Performance Evaluation

- Compare the optimized decision tree against commonly used benchmark algorithms such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [32].

- Evaluate models based on key metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Computational Efficiency (latency and memory usage) [34] [32].

Workflow Visualization: Decision Tree Model for Variant Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for a machine learning-enhanced genomic variant analysis pipeline.

Table: Key Resources for Genomic Variant Analysis with Machine Learning

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | The gold-standard framework for the clinical interpretation of sequence variants, providing criteria for classifying variants as Pathogenic, VUS, or Benign [30] [31]. |

| ClinVar Database | A public archive of reports detailing the relationships between human variations and phenotypes, with supporting evidence. Essential for benchmarking and identifying interpretation conflicts [30]. |

| Ensembl VEP (Variant Effect Predictor) | A tool that determines the effect of your variants (e.g., amino acid change, consequence type) on genes, transcripts, and protein sequence, as well as regulatory regions [30]. |

| gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database) | A resource that aggregates and harmonizes exome and genome sequencing data from a wide variety of large-scale sequencing projects. Critical for assessing variant allele frequency [30]. |

| Scikit-learn (sklearn) | A core Python library for machine learning. It provides efficient tools for building and evaluating decision tree models, including Random Forest and Gradient Boosting classifiers [35]. |

| FastQC | A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. It provides a modular set of analyses to quickly assess whether your raw genomic data is of high quality [33]. |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | A structured software library for variant discovery in high-throughput sequencing data. It provides best-practice workflows for variant calling and quality assessment [33]. |

| Python with Matplotlib | A fundamental plotting library for Python. Used for visualizing decision tree structures, feature importance, and other key model metrics to aid in interpretation [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are perturbation-observation pairs, and why are they fundamental for model refinement in biological systems?

Perturbation-observation pairs are a core data type in functional biology where a specific component of a biological system is perturbed (e.g., knocked out or stimulated), and the state of another component is observed [7]. In modeling, they are used to constrain and validate dynamic models. Unlike high-throughput data, these pairs are often piecewise and uneven, making them unsuitable for standard inference algorithms [7]. They are crucial for refining models because they provide direct, causal insights into the system's logic, allowing you to test and improve a model's predictive accuracy against known experimental outcomes.

Q2: My model fits the training perturbation data perfectly but fails to predict new experimental outcomes. What might be causing this overfitting?

Overfitting often occurs when a model becomes too complex and starts to memorize the training data rather than learning the underlying biological rules. To address this:

- Constrained Search Space: Limit the algorithm's search space to only biologically plausible models by incorporating existing mechanistic knowledge as logical constraints (e.g., "A is necessary for B") [7].

- Validation Set: Always hold back a portion of your experimental data (e.g., 20%) to use as a validation set. A refined model should show improved accuracy on both the training and this unseen validation set [7].

- Function Complexity: If using a tool like

boolmore, you can lock certain Boolean functions from mutating if they are already well-supported by evidence, preventing unnecessary complexity [7].

Q3: How can I refine a model when my data spans multiple time scales (e.g., fast signaling and slow gene expression)?

Integrating multi-scale data is challenging because a single model may not capture the full spectrum of dynamics. A proposed framework addresses this by:

- Data-Driven Decomposition: Using algorithms like Computational Singular Perturbation (CSP) to partition your dataset into subsets where the dynamics are similar and occur on a comparable time scale [36].

- Local Model Identification: Applying system identification methods, like Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy), to each subset to identify the appropriate reduced model for that specific dynamical regime [36].

- Jacobian Estimation: Employing Neural Networks to estimate the Jacobian matrix from observational data, which is required for time-scale decomposition methods like CSP when explicit equations are unavailable [36].

Q4: What should I do if my model's predictions and the experimental observation are in conflict for a specific perturbation?

A systematic troubleshooting protocol is essential [10]:

- Repeat the Experiment: If cost and time permit, repeat the experiment to rule out simple human error.

- Verify Biological Plausibility: Revisit the scientific literature. The unexpected result could be a true biological phenomenon (e.g., the protein is not expressed in that tissue) rather than a model error [10].

- Check Controls: Ensure you have appropriate positive and negative controls. If a positive control also fails, the issue likely lies with the protocol or reagents, not the model [10].

- Audit Equipment and Reagents: Check for improper storage or expired reagents. Visually inspect solutions for precipitates or cloudiness [10].

- Change Variables Systematically: If the experimental protocol is suspect, generate a list of variables (e.g., concentration, incubation time) and test them one at a time, starting with the easiest to change [10].

Q5: What is the advantage of using a genetic algorithm for model refinement compared to manual curation?