Biological vs. Technical Replicates: A Strategic Guide for qPCR and RNA-Seq in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical distinction between biological and technical replicates in qPCR and RNA-Seq experiments.

Biological vs. Technical Replicates: A Strategic Guide for qPCR and RNA-Seq in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical distinction between biological and technical replicates in qPCR and RNA-Seq experiments. It covers foundational concepts, methodological applications, and advanced optimization strategies to ensure data integrity. The content addresses common pitfalls, offers troubleshooting advice, and explores validation techniques, including the use of RNA-seq data to inform qPCR normalization. By synthesizing current best practices, this guide empowers scientists to design robust, reproducible experiments that yield statistically sound and biologically meaningful results, ultimately accelerating discovery in biomedical and clinical research.

What Are Biological and Technical Replicates? Defining the Core Concepts for Robust Science

Core Definitions and Purpose

In molecular biology research, particularly in quantitative techniques like qPCR and RNA-Seq, a clear understanding of replication is fundamental to generating statistically sound and biologically relevant data. The two primary types of replication, biological and technical, serve distinct and complementary purposes in experimental design.

Biological Replicates are defined as measurements taken from multiple, distinct biological sources or entities within the same experimental group. Their primary purpose is to capture the natural biological variation present in a population, thereby ensuring that the findings are generalizable and not specific to a single individual or sample [1] [2]. For instance, in a study investigating gene expression in response to a drug treatment, biological replicates would involve using cells or tissues derived from different animals or human donors [1]. This approach accounts for the inherent genetic and physiological diversity that exists between individuals. The variation observed among biological replicates is the true biological variation, and it is this variance that statistical tests use to determine if observed effects are significant and likely to be real, rather than mere chance occurrences [3].

Technical Replicates, in contrast, involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample. They are designed to assess and minimize the variation introduced by the experimental methodology itself [1] [2]. This includes variability from procedures such as pipetting, RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and instrument measurement. In a qPCR experiment, technical replicates would be multiple reaction wells loaded with cDNA from the same RNA extraction [1]. The primary value of technical replicates lies in providing an estimate of the precision of the experimental system, improving the reliability of the measurement for that specific sample, and allowing for the detection of potential outliers [1]. However, they do not provide any information about biological variability within a population.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Biological and Technical Replicates

| Feature | Biological Replicates | Technical Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Different biological samples or entities (e.g., individuals, animals, cells) [2] | The same biological sample, measured multiple times [2] |

| Source of Material | Multiple independent biological sources | A single, shared biological source |

| Primary Purpose | To assess biological variability and ensure findings are reliable and generalizable [2] | To assess and minimize technical variation from workflows and measurement [2] |

| Accounts for Variation In | Genetics, physiology, environment, and other inter-individual differences | Pipetting, instrument noise, reagent efficiency, and operator error |

| Example | 3 different animals or cell samples in each experimental group (treatment vs. control) [2] | 3 separate qPCR reactions or RNA-Seq libraries from the same RNA sample [2] |

Experimental Design and Protocols

The strategic implementation of both biological and technical replicates is critical for robust experimental design in both qPCR and RNA-Seq workflows. The optimal number and priority of each replicate type depend on the research question, the technique being used, and practical constraints.

qPCR Replication Protocol

In qPCR experiments, a nested replication strategy is widely recommended to ensure both accuracy and precision [4].

- Biological Replication: A minimum of three independent biological replicates per experimental condition is considered essential for statistical rigor [4]. This allows for a reasonable estimation of the biological variance, which forms the denominator in statistical tests comparing groups. For studies with high inherent variability, such as those involving outbred animal models or human tissues, increasing the number of biological replicates (e.g., 5-8) is highly advisable to achieve sufficient statistical power [1].

- Technical Replication: For each biological replicate, it is standard practice to run at least two or three technical replicates for each PCR reaction [4]. These are typically run on the same qPCR plate to control for inter-well variation. The primary role of these replicates is to provide a precise measurement for that specific biological sample and to flag any potential reaction failures or outliers. The mean Cq value of the technical replicates is typically used for subsequent calculations of gene expression [4].

This design means that for one gene and one sample, a researcher would use 3 biological replicates × 3 technical replicates = 9 reaction wells [5]. This structure ensures that statistical analysis is performed on the biological replicates, which are the independent data points, thereby allowing for valid inference about the population.

RNA-Seq Replication Protocol

In RNA-Seq, the principles of replication are similar, but the cost and workflow scale shift the priorities.

- Biological Replication is Paramount: For RNA-Seq experiments designed to detect differential gene expression, biological replicates are critically important and are required, not technical replicates [6]. Technical replicates (e.g., sequencing the same library multiple times) are generally discouraged as they consume resources without providing new information about biological variability.

- Recommended Numbers: A minimum of three biological replicates per condition is considered the absolute minimum, but four is the optimum minimum for reliable results [6]. For more complex studies or those with higher expected variability, between 4 and 8 replicates per sample group are recommended to cover most experimental requirements and provide adequate statistical power [2].

- Batch Effects: When processing a large number of samples, it is inevitable that they will be processed in batches. The experimental design must account for this by ensuring that replicates for each condition are distributed across different processing batches. This allows for batch effects to be measured and removed bioinformatically during data analysis [2] [6].

Table 2: Summary of Replication Best Practices in qPCR and RNA-Seq

| Aspect | qPCR | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Biological Replicates | 3 [4] | 3 (absolute minimum), 4 (optimum minimum) [6] |

| Typical Technical Replicates | 2-3 per biological sample [4] | Not generally recommended; biological replicates are preferred [6] |

| Primary Goal of Replication | Improve precision of measurement for each sample and estimate biological variance | Ensure statistical power for differential expression detection and generalizability |

| Statistical Unit | The biological replicate (e.g., mean value from one individual's technical replicates) | The biological replicate (e.g., one sequencing library from one individual) |

| Key Consideration | Plate layout and randomization to control for well effects [1] | Batch effect correction by distributing samples across processing runs [2] |

Statistical Rationale and Data Analysis

The mathematical and statistical principles underlying replication provide a clear rationale for prioritizing biological over technical replicates, especially when resources are limited.

The total variance in an experiment ((σ{TOT}^2)) can be decomposed into contributions from different levels of replication. A model for this is: (σ{TOT}^2 = σ{A}^2 + σ{C}^2 + σ{M}^2), where (σ{A}^2) is the variance between animals (biological replicates), (σ{C}^2) is the variance between cell samples from the same animal, and (σ{M}^2) is the variance from the measurement technique (technical replicates) [3]. The precision of the estimated mean expression depends on how these variances are weighted by the number of replicates at each level: (Var(\overline{X}) = \frac{σ{A}^2}{n{A}} + \frac{σ{C}^2}{n{A}n{C}} + \frac{σ{M}^2}{n{A}n{C}n_{M}}) [3].

This formula reveals a critical insight: increasing the number of biological replicates ((nA)) reduces the contribution of all variance components, including the technical variance ((σ{M}^2)). In contrast, increasing only technical replicates ((n_M)) only reduces the measurement error. Consequently, investing in more biological replicates is a more efficient way to improve the precision and reliability of the overall experiment [3].

In RNA-Seq, this principle is powerfully demonstrated in the context of sequencing depth. When total sequencing throughput is fixed, allocating the data to more biological replicates provides a greater boost to the detection of differentially expressed genes (True Positive Rate) than sequencing each of a few samples at a greater depth [7]. For example, splitting a fixed total data量 across 6 biological replicates yields a much higher true positive rate than sequencing 2 biological replicates at three times the depth [7].

For statistical testing in qPCR, after technical replicates have been averaged, the normalized relative quantities (NRQs) from the biological replicates are typically log-transformed to stabilize variance [4]. Statistical comparisons between groups, such as with a t-test or ANOVA, are then performed using these transformed values from the biological replicates, which represent the independent data points [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Replicate-Based Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Replication |

|---|---|

| Passive Reference Dye (qPCR) | A dye included in the qPCR master mix at a fixed concentration to normalize for variations in reaction volume and optical anomalies across wells, thereby improving the precision of technical replicates [1]. |

| Spike-in Controls (RNA-Seq) | Artificial RNA or DNA sequences added in known quantities to each sample during library preparation. They serve as an internal standard to control for technical variation across samples, allowing for normalization and assessment of technical performance in large-scale experiments [2]. |

| Multiplex Assays (qPCR) | The amplification and detection of multiple gene targets (e.g., a gene of interest and a reference gene) in the same reaction well. This setup allows for normalization within the well, creating a precision correction that improves the overall precision of the data [1]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Reagents used to remove abundant ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples prior to RNA-Seq library construction. This enhances the sequencing coverage of mRNA and other RNA species, improving the sensitivity and efficiency of data obtained from each biological replicate [8]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Kits for constructing RNA-Seq libraries that preserve the strand orientation of transcripts. This is crucial for accurate transcript annotation and quantification, especially in complex genomes, ensuring that data from different biological replicates are comparable and biologically meaningful [8]. |

To maximize the return on investment in research, scientists should adhere to several key best practices regarding replicates.

- Prioritize Biological Replicates: Always prioritize resources for an adequate number of biological replicates. This is the most critical factor for ensuring the statistical power and generalizability of your results [3] [7]. For both qPCR and RNA-Seq, a minimum of three biological replicates is a standard starting point, with more required for noisy systems or subtle expected effects [4] [6].

- Use Technical Replicates Judiciously: In qPCR, use technical replicates (typically 2-3) to improve the precision of the measurement for each biological sample. In RNA-Seq, technical replicates of sequencing runs are generally not cost-effective; the focus should be on biological replication [6].

- Plan for Batch Effects: For large studies, design your experiment so that biological replicates from all experimental groups are distributed across processing batches (e.g., different days, different library prep kits). This design enables the use of bioinformatic tools to correct for batch effects during data analysis, preventing them from being confounded with the biological effect of interest [2] [6].

- Validate with Pilot Studies: When working with a new model system or assay, conduct a small pilot study to estimate the levels of biological and technical variation. This data will inform a proper power analysis, helping you determine the optimal number of biological replicates needed for the definitive study [2].

In conclusion, a profound understanding of the distinct roles of biological and technical replicates is non-negotiable for rigorous scientific research. Biological replicates are the cornerstone of generalizable findings, as they capture the true variation of the system under study. Technical replicates are valuable tools for optimizing and monitoring the precision of laboratory measurements. By strategically implementing these principles in the experimental design of qPCR and RNA-Seq studies, researchers can produce data that is both statistically defensible and biologically relevant, ultimately accelerating discovery in drug development and basic research.

In molecular biology research, particularly in gene expression analysis using techniques like qPCR and RNA-Seq, the concepts of biological and technical replication form the bedrock of statistically sound and biologically meaningful experimental design. A precise understanding of this distinction is not merely academic; it directly governs the validity, interpretation, and generalizability of research findings. Biological replicates are defined as measurements performed on distinct biological units (e.g., different animals, plants, or independently cultured cell lines) sampled from a population. They are essential for capturing the random biological variation inherent in the system under study [3] [9]. In contrast, technical replicates involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample (e.g., the same RNA extract aliquoted and measured multiple times) and primarily serve to quantify and reduce the noise introduced by the measurement technology itself [3] [9].

The fundamental distinction lies in what each type of replicate can conclude. Technical replicates provide high confidence in the measurement of a single individual but cannot infer anything about the population from which that individual was drawn. As one analogy aptly notes, "repeating multiple measurements of one man and one woman's height cannot support a conclusion about differences in height between men and women" [9]. For such a generalized conclusion, multiple different men and women—biological replicates—are required. This application note will delineate the profound impact of this distinction on data interpretation, provide robust experimental protocols, and establish a framework for optimal replicate design in qPCR and RNA-Seq studies.

The Statistical and Conceptual Foundation of Replicates

The core reason for the critical distinction between biological and technical replicates is their contribution to the total variance observed in an experiment. The total variance (σ²_TOT) in a dataset can be conceptually broken down into components originating from different levels of replication [3]:

σ²TOT = σ²A + σ²C + σ²M

In this model, σ²A represents the variance arising from differences between individual animals or primary biological units, σ²C denotes the variance from preparing multiple cell cultures from one animal, and σ²M signifies the variance introduced by the measurement technology itself [3]. Biological replicates account for σ²A and σ²C, while technical replicates only account for σ²M.

The implications for experimental design are profound. When the number of biological replicates (nA) is one, the experiment cannot estimate the biological variance (σ²A). Consequently, the total variance is underestimated, and any statistical tests performed are prone to false positives, as the analysis mistakenly interprets technical variation as a true biological effect [3]. The primary goal of increasing biological replicates is to obtain a more accurate estimate of the population variance, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the findings. The goal of technical replication is to increase the precision of the measurement for a specific sample, thereby improving the reliability of individual data points.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Biological and Technical Replicates

| Feature | Biological Replicates | Technical Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measurements from different biological sources [9] | Repeated measurements on the same biological sample [9] |

| Primary Purpose | To capture inherent biological variation and allow generalization to a population [3] [9] | To quantify and reduce measurement error/technical noise [3] [9] |

| Controls For | Biological variability between individuals, sample preparation differences | Pipetting error, instrument noise, assay variability |

| Impact on Variance | Estimates σ²A (Animal/biological unit variance) and σ²C (Cell culture variance) [3] | Estimates σ²_M (Measurement technology variance) [3] |

| Impact on Conclusions | Enables inference to the broader population | Provides confidence in the measurement of a specific sample |

| Risk of Misuse | False positives and over-generalization if underpowered [3] [10] | False positives if used to infer population-level effects [3] |

Quantitative Impact on Data Interpretation: Evidence from RNA-Seq

Empirical studies have systematically evaluated the trade-offs between sequencing depth (which is related to technical measurement) and biological replication. The consensus from multiple high-citation studies is clear: once a minimum sequencing depth is achieved, increasing the number of biological replicates provides a substantially greater boost to statistical power and reliability than further increasing depth [10].

Research shows that for differential expression analysis in RNA-Seq, a sequencing depth of around 10 million reads per library often represents a practical sufficiency point. When reads increase from 2.5 million to 10 million, the ability to detect differentially expressed genes (sensitivity) and the precision of fold-change estimates improve markedly. However, beyond 10 million reads, these gains diminish significantly, and the curves for metrics like the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and the coefficient of variation of log-fold change flatten out [10].

In contrast, increasing the number of biological replicates continues to significantly improve detection power and reduce false discovery rates well beyond typical sample sizes. For instance, one analysis showed that with just one biological replicate, the true positive rate was approximately 55% at a false positive rate of 20%. Increasing to just two biological replicates raised the true positive rate to about 75% at the same false positive rate, and benefits were still evident up to 14 replicates [10]. This underscores that biological replication is the primary determinant of the ability to detect true biological effects, especially for low-abundance transcripts where technical noise is proportionally higher.

Table 2: Impact of Sequencing Depth vs. Biological Replication on Key RNA-Seq Analysis Metrics

| Metric | Impact of Increasing Sequencing Depth (from 2.5M to 10M reads) | Impact of Further Increasing Depth (>10M reads) | Impact of Increasing Biological Replicates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity (True Positive Rate) | Increases significantly [10] | Gains are minimal and plateau [10] | Increases significantly and consistently, even at high replicate numbers [10] |

| False Positive Rate (FPR) | For high-abundance genes: FPR decreases [10] | Effect plateaus [10] | For high-abundance genes: FPR decreases with more replicates [10] |

| Precision of Fold-Change (CV of logFC) | Coefficient of Variation decreases markedly [10] | Effect plateaus, curve flattens [10] | Superior reduction in CV compared to increasing depth; improves result reliability [10] |

| Recommendation | Essential to reach a minimum threshold (e.g., 10M reads) | Lower priority; yields diminishing returns | High priority after minimum depth; most effective use of resources [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Protocol for qPCR Experiment Design and Analysis

A. Experimental Design

- Biological Replicates: The number of biological replicates is the most critical factor for a robust experiment. A minimum of n=3 is required for any statistical comparison, but n=5-8 is strongly recommended to achieve adequate power, particularly for detecting small effect sizes [3].

- Technical Replicates: Technical replicates are used to control for pipetting and platform variance. Running samples in triplicate (n=3) is standard practice. It is crucial to understand that these are used to calculate a single, more precise measurement value (e.g., mean Ct) for that biological sample before statistical comparison across biological replicates.

B. Sample Processing and RNA Extraction

- Process biological samples independently throughout the entire workflow, from homogenization to RNA extraction. Pooling samples before RNA extraction should be avoided unless it is explicitly part of the experimental question, as it destroys information about inter-individual variation and effectively turns multiple biological replicates into a single one [11].

- Use a single, well-validated RNA extraction method for all samples to minimize technical variation introduced at this stage.

C. Data Analysis Workflow

- Calculate Technical Variation: For each biological sample, calculate the mean Ct value and standard deviation from its technical replicates. A high standard deviation may indicate a pipetting error or well-specific failure.

- Normalize to Endogenous Controls: Normalize the gene of interest's mean Ct value to the mean Ct value of one or more stable reference genes (∆Ct).

- Perform Statistical Analysis: Use the normalized values (∆Ct) from each biological replicate (not the technical replicates) as the input data for statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA) comparing experimental groups. The n-value for this analysis is the number of biological replicates.

Protocol for RNA-Seq Experiment Design and Analysis

A. Experimental Design and Power Analysis

- Prioritize Biological Replication: Allocate the majority of the budget to biological replication. For model organisms under controlled conditions, a minimum of n=4 is recommended, while for human cohorts or heterogeneous samples, n>10 may be necessary.

- Determine Sequencing Depth: Allocate sufficient depth to saturate gene discovery. For standard differential expression analyses in a well-annotated genome, 10-20 million reads per library is often adequate [10]. Deeper sequencing is required for novel isoform or splice variant discovery.

- Avoid Pooling: Avoid the practice of pooling RNA from multiple biological individuals into a single sequencing library. This confounds biological variance and prevents statistical assessment of inter-individual variability, severely limiting the generalizability of the results [11]. If faced with previously pooled data, analysis must shift to methods like Mfuzz for time-series patterns, as standard differential expression testing is invalidated [11].

B. Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Perform stringent quality control on individual samples. Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN), and for the resulting sequencing data, use tools like FastQC. Filter cells or libraries based on metrics like counts per cell, number of genes detected, and mitochondrial read fraction to remove low-quality cells or libraries [12].

- Employ dedicated tools like Scrublet or DoubletFinder to identify and remove multiplets (technical artifacts where two cells are sequenced as one) in single-cell RNA-Seq data [12].

C. Data Analysis and Validation

- Assess Replicate Concordance: Before differential expression analysis, evaluate the quality of biological replicates by calculating inter-sample correlations (e.g., Spearman correlation) [13] or by performing Principal Component Analysis (PCA). High correlation between replicates within a group and clear separation between groups in PCA is indicative of a strong experiment.

- Differential Expression: Use statistical frameworks designed for RNA-Seq data that explicitly model biological variation, such as DESeq2, edgeR, or limma-voom. These tools use the variation between biological replicates to estimate gene-wise dispersions and test for significance.

- Independent Validation: Always validate key findings from RNA-Seq using an orthogonal method, such as qPCR, on independent biological replicates. This confirms the technical validity and biological relevance of the results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Replicate-Based Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Consideration for Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality RNA from biological material. | Use the same kit and lot number for all samples in a study to minimize technical variation. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Removes genomic DNA contamination from RNA preparations. | Essential for accurate qPCR results; must be applied consistently to all samples. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates. | Using a master mix for reverse transcription of all samples controls for kit performance variability. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye for real-time PCR. | A master mix is critical for technical replicates to ensure uniform reaction conditions. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules during library prep [12]. | Allows bioinformatic correction for PCR amplification bias, improving technical accuracy of RNA-Seq counts. |

| Viability Stain (e.g., Trypan Blue) | Assesses cell viability prior to single-cell sequencing or culture. | Ensures consistency in starting material quality across biological replicates. |

The distinction between biological and technical replicates is a fundamental principle that directly dictates the scientific validity and broader impact of research. Biological replicates are non-negotiable for drawing conclusions that extend beyond the specific individuals measured in the study, as they account for the natural variation that defines biological systems. Technical replicates are necessary for ensuring measurement precision but are a poor substitute for biological replication.

To implement these principles, follow this decision guide:

- For Generalizability: Your experimental n-number must be the number of biological replicates. This is the primary determinant of statistical power [3] [10].

- For Resource Allocation: In RNA-Seq, after achieving a baseline sequencing depth (e.g., 10M reads), investing in more biological replicates yields a greater return on investment than further increasing sequencing depth [10].

- For Analysis: Always use the summary values from technical replicates (e.g., mean Ct) from each biological replicate as the input for statistical tests comparing groups.

- For Quality Control: Routinely assess the correlation and clustering of biological replicates as a first step in data analysis. Poor concordance often indicates underlying experimental or sample-quality issues [13].

The Critical Role of Replication in Statistical Power and Experimental Reproducibility

In quantitative life science research, the principles of replication form the cornerstone of experimental validity. Replication involves the repetition of experimental procedures to assess the variability, reliability, and significance of observed results. Within molecular techniques such as qPCR and RNA-Seq, understanding and implementing appropriate replication strategies is fundamental to distinguishing biological significance from technical artifacts. The credibility of scientific findings depends heavily on robust replication, as irreproducible research wastes an estimated $28 billion annually in preclinical studies alone [14]. This application note examines the critical distinction between biological and technical replicates, their differential impacts on statistical power, and provides detailed protocols for implementing replication strategies that enhance experimental reproducibility in genomics research.

Defining Replicate Types and Their Applications

Conceptual Framework

In experimental design, replicates are categorized based on what source of variability they aim to capture, which directly influences how results can be interpreted and generalized.

Biological replicates are defined as independent biological samples that represent the entire population of interest, each processed separately through the experimental workflow. In the context of qPCR and RNA-Seq research, biological replicates account for the natural variation occurring between subjects, cell cultures, or organisms [15] [1]. For example, when researching the effect of drug treatment on gene expression in mice, multiple mice receiving the same treatment constitute biological replicates. These replicates are essential for capturing biological variation and ensuring that study conclusions can be generalized to the population [1].

Technical replicates involve multiple measurements of the same biological sample. They are repetitions of the same sample using the same template preparation and PCR reagents, processed through the identical experimental workflow [1]. Technical replicates primarily estimate the variation inherent to the measuring system itself, including pipetting variation, instrument-derived variation, and other technical noise sources [1]. While they help improve measurement precision and identify technical outliers, technical replicates cannot account for biological variability and therefore do not strengthen inferences about population-level effects [15].

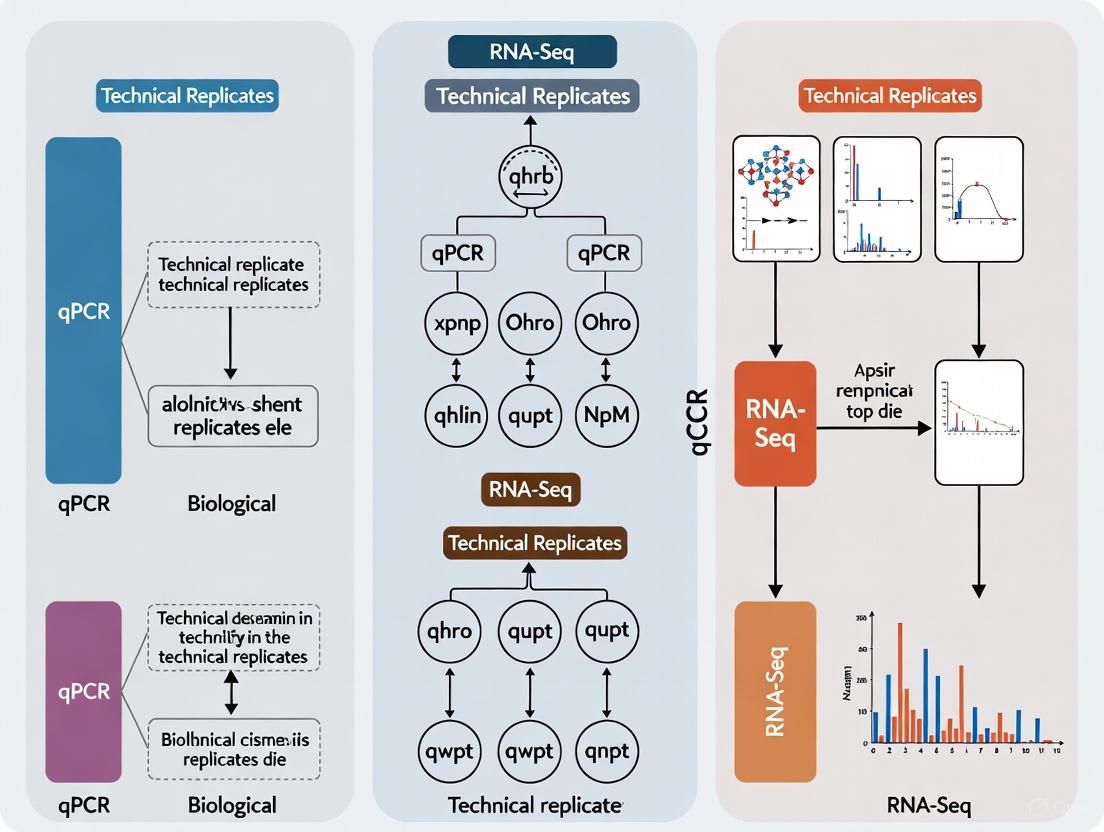

The relationship between these replicate types and their role in experimental design can be visualized as a hierarchical process:

The Critical Problem of Pseudoreplication

A fundamental error in experimental design occurs when researchers mistakenly treat technical replicates or pseudo-biological replicates as true biological replicates [15]. This problem, known as pseudoreplication, artificially inflates statistical significance and leads to hundreds of false positive differentially expressed genes in genomic studies [15]. A common example includes treating three cell-culture flasks of the same passage of a cell line as biological replicates when they actually originated from the same biological source [15]. This practice fails to capture true biological variation and results in spurious findings that cannot be reproduced in subsequent studies.

Quantitative Impact of Replication on Statistical Power

Empirical Evidence from RNA-Seq Studies

The relationship between biological replication and statistical power in genomics research has been quantitatively demonstrated through comprehensive RNA-Seq experiments. A landmark study performing RNA-seq with 48 biological replicates in each of two conditions revealed striking findings about replication requirements [16].

Table 1: Statistical Power for Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in RNA-Seq Based on Replicate Number

| Biological Replicates | Percentage of All SDE Genes Detected | Percentage of >4-Fold Change SDE Genes Detected | Recommended Statistical Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20%-40% | >85% | edgeR, DESeq2 |

| 6 | ~60% | >90% | edgeR, DESeq2 |

| 12 | >85% | >95% | DESeq2 |

| 20+ | >85% | >95% | DESeq |

With only three biological replicates—a common practice in many published studies—current statistical tools identified only 20-40% of the significantly differentially expressed (SDE) genes detected using the full set of 42 clean replicates [16]. This statistical power limitation is particularly pronounced for genes with subtle expression changes, though even with low replication, genes showing strong fold changes (>4-fold) can be detected with >85% power [16]. To achieve >85% detection power for all SDE genes regardless of fold change magnitude, more than 20 biological replicates are required [16].

Field-Specific Replication Guidelines

Best practices for replication vary across molecular techniques, reflecting differing technical variabilities and application requirements:

Table 2: Replication Guidelines by Experimental Method

| Method | Minimum Replicates | Optimal Replicates | Replicate Type Emphasis | Sequencing Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq | 3 | 4-6+ | Biological [6] | 10-60M PE reads |

| ChIP-Seq | 2 | 3 | Biological [6] | 10-30M reads |

| qPCR | 3 technical | 3 biological + 2-3 technical | Both [1] | N/A |

For RNA-Seq experiments, biological replicates are strongly recommended over technical replicates, with an absolute minimum of 3 replicates, though 4 replicates provides a more optimum minimum [6]. The CCBR Bioinformatics Core recommends processing RNA extractions simultaneously whenever possible, as extractions performed at different times introduce unwanted batch effects that compromise reproducibility [6]. When batch processing is unavoidable, researchers should ensure that replicates for each condition are represented in each batch so bioinformatic tools can measure and remove these effects during analysis [6].

In qPCR experiments, both replicate types serve distinct purposes. Technical replicates (typically triplicates) provide estimates of system precision, improve experimental variation measurements, and allow for outlier detection [1]. Biological replicates account for the true variation in target quantity among samples within the same group, enabling appropriate statistical generalization to the population [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing Replication for RNA-Seq Experiments

Principle: Biological replicates are essential for RNA-Seq because they capture the natural variation in gene expression between individuals, treatments, or conditions. Technical variation in sequencing is generally low compared to biological variation, making technical replicates less valuable than biological replicates [15].

Materials:

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy)

- DNase I digestion kit

- RNA integrity assessment system (e.g., Bioanalyzer)

- Library preparation kit

- Sequencing platform (Illumina recommended)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design Phase:

- Determine primary research question and key comparisons

- For animal studies: Plan for a minimum of 4 biological replicates per condition using distinct animals [6]

- For cell culture: Ensure biological replicates represent independent cultures from different passages or source flasks, not aliquots from the same culture [15]

- Calculate sample size using power analysis when possible

Sample Collection and Randomization:

- Process biological replicates independently throughout entire workflow

- Randomize sample processing order to avoid batch effects

- If processing in batches is unavoidable, ensure each batch contains samples from all experimental conditions

RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract RNA using standardized protocol

- Determine RNA Integrity Number (RIN) - require RIN >8 for mRNA sequencing [6]

- Quantify RNA using fluorometric method

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use the same library preparation kit for all samples

- For mRNA analysis: Use mRNA library prep (10-20M paired-end reads) [6]

- For total RNA analysis (including non-coding RNA): Use total RNA method (25-60M paired-end reads) [6]

- Multiplex all samples together and run on the same sequencing lane when possible

Data Analysis:

Validation: Include positive control genes with known expression patterns when possible. Monitor internal consistency between replicates through correlation analysis.

Protocol 2: Implementing Replication in qPCR Experiments

Principle: qPCR experiments require both technical replicates (to measure system precision) and biological replicates (to capture population variation) for statistically valid conclusions [1].

Materials:

- qPCR instrument with calibrated temperature verification

- Pipettes with regular calibration

- Quality-controlled primers and probes

- Passive reference dye

- Plate centrifuge

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Include 3-5 biological replicates per experimental group

- Plan for 3 technical replicates per biological sample

- Include no-template controls and positive controls

Sample Preparation:

- Process each biological sample independently through RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

- Use the same reagent batches for all samples within an experiment

- Verify RNA quality and quantity before proceeding

Reaction Plate Setup:

- Master mix preparation: Prepare sufficient master mix for all technical replicates plus excess

- Aliquot master mix to plate first, then add template

- Include passive reference dye in reactions

- Ensure sample volume does not exceed 20% of PCR reaction volume to prevent optical mixing [1]

Plate Sealing and Centrifugation:

- Seal plate thoroughly to prevent evaporation

- Centrifuge plate briefly to bring liquids to well bottom and remove air bubbles

qPCR Run:

- Use manufacturer-recommended cycling conditions

- Verify temperature calibration of instrument blocks

- Include melt curve analysis for SYBR Green assays

Data Analysis:

- Calculate mean Cq values from technical replicates

- Identify and investigate outliers using coefficient of variation (CV >5% suggests technical issues) [1]

- Use appropriate normalization strategy (multiple reference genes recommended)

- Perform statistical tests (t-tests, ANOVA) on biological replicates, not technical replicates

Troubleshooting: High technical variation (CV >5%) may indicate pipetting errors, inadequate mixing, or instrument issues. Unusually low biological variation may indicate pseudoreplication or over-controlled conditions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Robust Replication Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Quality Control Requirements | Impact on Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticated Cell Lines | Biological replicate source | STR profiling, mycoplasma testing, low passage use [14] | Prevents false results from misidentified or contaminated lines |

| RNA Preservation Reagents | Stabilize RNA expression profiles | RNase-free certification, batch consistency | Maintains accurate transcriptome representation |

| Nucleic Acid Quantitation Kits | Accurate sample quantification | Fluorometric quantification standards | Ensures equal loading and reduces technical variation |

| Library Preparation Kits | cDNA library construction | Lot-to-lot consistency testing | Reduces batch effects in sequencing data |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification reaction | Performance validation, inclusion of passive reference dye [1] | Improves precision and enables cross-plate comparison |

| Validated Antibodies (ChIP-Seq) | Target protein immunoprecipitation | ChIP-seq grade verification, lot number tracking [6] | Ensures specific binding and reproducible results |

Integrated Replication Strategy and Workflow

Implementing a comprehensive replication strategy requires understanding how different replicate types interact throughout the experimental process. The following workflow illustrates how biological and technical replicates integrate to deliver statistically powerful and reproducible results:

Proper experimental replication represents a fundamental pillar of scientific rigor in molecular biology research. The strategic implementation of both biological and technical replicates, following the detailed protocols outlined in this document, enables researchers to accurately distinguish biological effects from technical artifacts. By adhering to evidence-based replication standards—incorporating sufficient biological replicates to achieve appropriate statistical power, utilizing technical replicates to measure system precision, and avoiding the critical pitfall of pseudoreplication—scientists can significantly enhance the reproducibility and reliability of their genomic findings. These practices not only strengthen individual research outcomes but also contribute to the collective advancement of robust scientific knowledge.

In gene expression studies using qPCR and RNA-Seq, understanding and managing sources of variation is fundamental to generating reliable, reproducible data. The accuracy of biological conclusions depends on properly distinguishing between different types of noise inherent in these sensitive techniques. Variation in molecular experiments can be categorized into three primary types: system variation from technical measurement processes, biological variation from inherent differences between subjects, and experimental variation which represents the combined effect observed in data [1]. Each type has distinct characteristics, implications for data interpretation, and requires specific methodological approaches for mitigation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for identifying, quantifying, and controlling these variability sources within the context of replicate strategy decisions in qPCR and RNA-Seq workflows, enabling researchers to optimize experimental designs for robust scientific conclusions.

System Variation

System variation, also called technical variation, originates from the measurement system itself. This includes variability introduced by instrumentation, reagent efficiency, and operator technique [1]. In qPCR, contributors include pipetting inaccuracies, instrument calibration differences, well-position effects in thermal cyclers, and batch-to-batch variations in reagent kits [1]. For RNA-Seq, system variation encompasses library preparation efficiency, sequencing depth differences, and lane effects on flow cells [17]. System variation can be estimated by assaying multiple aliquots of the same biological sample, known as technical replicates [1]. This type of noise directly impacts measurement precision and can be reduced through protocol optimization and technical replication.

Biological Variation

Biological variation represents the true physiological differences in target quantity between individual organisms or samples within the same experimental group [1]. This variation arises from genetic heterogeneity, differential environmental exposures, stochastic cellular processes, and subtle variations in experimental treatments. For example, when researching drug treatment effects on gene expression in mice, biological variation exists between individual mice treated with the same drug [1]. Biological variation is accounted for by including multiple biological replicates in an experimental design – truly independent samples that represent the population being studied [1]. This variation determines the fundamental resolution limits for detecting biologically significant effects.

Experimental Variation

Experimental variation is the composite variability measured for samples belonging to the same biological group [1]. It serves as the practical estimate of true biological variation but is inevitably influenced by system variation. Due to this influence, experimental variation will typically not exactly equal the true biological variation [1]. The magnitude of system variation directly impacts how accurately experimental variation reflects biological reality – larger system variation increases its potential to distort experimental variation estimates [1]. Understanding this relationship is crucial for appropriate statistical interpretation of experimental data.

The diagram below illustrates the relationships and components of these three sources of variation:

Statistical Metrics for Quantifying Variation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100% | Measure of precision; lower CV indicates higher consistency | Assessing technical replicate consistency in qPCR [1] |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | √[Σ(xᵢ - μ)²/(N-1)] | Absolute measure of dispersion in data units | Describing population distribution; ±1 SD ≈ 68% of normally distributed population [1] |

| Standard Error (SE) | SD / √N | Measure of sampling error of the mean | Providing confidence boundaries for how close measured mean is to true mean [1] |

Replicate Strategy Impact on Variation

| Replicate Type | Definition | Controls For | Typical Number | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Replicates | Repeated measurements of same sample aliquot [1] | System variation | 2-3 for qPCR [1] | Improves measurement precision; detects amplification failures; adds cost [1] |

| Biological Replicates | Measurements from different biological sources [1] | Biological variation | 3-6+ depending on effect size | Essential for statistical inference; captures population diversity [20] |

| Artificial Replicates (RNA-Seq) | Computationally generated replicates [17] | Assessment of reproducibility | Variable | FASTQ-bootstrapping shows best performance; computationally intensive [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Variance Analysis

Protocol: Assessing System Variation in qPCR

Principle: Quantify technical noise by repeatedly measuring identical sample aliquots to establish platform precision and identify optimal technical replicate strategy [1] [20].

Materials:

- Homogeneous cDNA sample (from bulk RNA extraction)

- Validated primer sets for high, medium, and low abundance targets

- qPCR instrument with calibrated block temperature

- Master mix prepared for full replicate set

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Create a single master mix containing all reaction components and aliquot into 12 wells of a qPCR plate for each target gene to be assessed [1].

- Plate Setup: Distribute replicates across different plate positions to identify positional effects.

- Amplification: Run qPCR with standardized cycling conditions.

- Data Collection: Record Ct values for all replicates.

- Variation Calculation:

Interpretation: Technical CV < 5% generally indicates acceptable precision. Recent large-scale evidence suggests duplicates often approximate triplicate means sufficiently, offering potential 33-66% savings in reagents and time [20].

Protocol: Evaluating Biological Variation in RNA-Seq

Principle: Distinguish biological variability from technical noise through appropriate replicate design and analysis to ensure adequate power for detecting differential expression [19] [17].

Materials:

- Appropriately preserved tissue or cell samples from multiple biological sources

- RNA extraction kit with DNase treatment

- RNA integrity assessment system (e.g., Bioanalyzer)

- Library preparation kit (whole transcriptome or 3' mRNA-Seq)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Include minimum of 4-6 biological replicates per condition for adequate power [17].

- Consider using 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) for large-scale gene expression studies with many samples, as it provides cost-effective quantification with lower sequencing depth requirements (1-5 million reads/sample) [19].

- Reserve whole transcriptome sequencing for studies requiring isoform resolution, splicing information, or non-polyadenylated RNA detection [19].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Process biological replicates simultaneously using same reagent batches.

- Include randomization during library preparation and sequencing runs.

- Data Analysis:

- Perform quality control (FastQC) and alignment (STAR).

- Generate read counts (featureCounts) and analyze with statistical software (DESeq2).

- Assess biological variation through:

- PCA plots to visualize sample clustering.

- Inter-replicate correlation analysis.

- Dispersion estimates across expression levels.

Interpretation: High concordance between biological replicates indicates robust results. Studies show that 3' mRNA-Seq and whole transcriptome approaches yield highly similar biological conclusions despite differences in numbers of detected differentially expressed genes [19].

Protocol: Artificial Replicate Generation for RNA-Seq

Principle: Generate computational replicates to assess analysis reproducibility when true technical replicates are unavailable [17].

Materials:

- Original FASTQ files from RNA-seq experiment

- Sufficient computational storage and processing resources

- Standard RNA-seq analysis pipeline (Trimmomatic, STAR, DESeq2)

Procedure for FASTQ Bootstrapping (FB):

- Read Resampling: For each original FASTQ file, draw π·k reads with replacement, where k is original read count and π is percentage (typically 100%) [17].

- File Generation: Create new FASTQ files containing resampled reads.

- Standard Analysis: Process bootstrapped FASTQ files through identical mapping and quantification pipeline as original data.

- Comparison: Analyze correlation of p-values and fold changes between original and bootstrapped datasets.

Alternative Methods:

- Column Bootstrapping (CB): Bootstrap samples from columns of expression matrix [17].

- Mixing Observations (MO): Generate new samples as weighted means of original expression columns [17].

Interpretation: FASTQ bootstrapping produces results most similar to true technical replicates, making it preferred for reproducibility assessment, despite higher computational requirements [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Variance Control | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | Maxima H Minus, SuperScript IV [18] | Minimize RT efficiency variation; critical bottleneck in single-cell workflows | Select for high sensitivity, reproducibility, and ability to handle degraded samples [18] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays [20] | Provide consistent amplification efficiency; reduce technical variation | Probe-based chemistries show lower variability than dye-based [20] |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | QuantSeq (3' mRNA), Stranded mRNA (whole transcriptome) [19] | Control for library preparation bias and coverage variation | Choose based on research question: gene quantification (3') vs. isoform detection (whole) [19] |

| Normalization Reagents | Passive reference dyes (ROX) [1] | Correct for pipetting variation and optical anomalies | Essential for improving precision in qPCR; use according to instrument requirements [1] |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | RNAlater, QIAzol [17] [18] | Preserve RNA integrity; minimize degradation-induced variation | Critical for working with challenging samples (FFPE, low input) [19] |

Methodological Decision Framework

The workflow below outlines key decision points for designing gene expression experiments that properly account for different sources of variation:

Proper management of variation sources requires strategic experimental design decisions that balance practical constraints with scientific rigor. System variation can be controlled through technical optimization and appropriate replication, but biological variation must be addressed through adequate biological replication [1] [20]. Method selection between qPCR and RNA-Seq—and within RNA-Seq between 3' focused and whole transcriptome approaches—significantly impacts the ability to resolve biological signals from technical noise [19]. When true replicates are limited, computational approaches like FASTQ-bootstrapping provide valuable alternatives for assessing reproducibility [17]. By systematically addressing each source of variation through the protocols and frameworks presented here, researchers can design more efficient experiments and draw more reliable biological conclusions from gene expression data.

Strategic Experimental Design: How to Implement Replicates in qPCR and RNA-Seq Workflows

In the realm of gene expression analysis, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technology for its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative capabilities. The reliability of qPCR data, however, is profoundly influenced by experimental design, particularly the implementation of appropriate replication. Within the context of a broader thesis comparing qPCR and RNA-Seq methodologies, understanding the distinction and optimal application of biological versus technical replicates is paramount. Proper replication strategy not only controls for experimental variability but also ensures that observed differences reflect true biological phenomena rather than technical noise. This document outlines evidence-based best practices for determining the optimal number of replicates in qPCR experiments, providing detailed protocols to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in producing robust, reproducible, and statistically significant data.

Understanding Replicate Types: Biological vs. Technical

Replicates in qPCR experiments are broadly categorized into two types: technical and biological. Each serves a distinct purpose in controlling for different sources of variation and is fundamental to a sound experimental design.

Technical Replicates are multiple repetitions of the same biological sample. They are created by dividing a single nucleic acid extraction into multiple wells, using the same template preparation and PCR reagent master mix. The primary role of technical replicates is to assess the precision and variability inherent to the qPCR measurement system itself. This includes variation from pipetting, instrument noise, and reaction efficiency. Technical replicates help identify potential outliers and provide a more reliable measure (e.g., the mean) for that specific sample's Cq value. However, they do not provide information about the biological variation within a sample group [1].

Biological Replicates are measurements taken from multiple, independent biological samples within the same experimental group. For example, in a study investigating the effect of a drug treatment on gene expression in mice, each individually treated mouse represents a distinct biological replicate. Biological replicates are essential because they account for the natural variation that exists between individuals or primary samples in a population. The experimental variation measured across biological replicates is used as an estimate of this true biological variation and forms the basis for statistical comparisons between groups (e.g., Control vs. Treated) [1] [4].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each replicate type:

Table 1: Characteristics of Technical and Biological Replicates in qPCR

| Feature | Technical Replicates | Biological Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Multiple measurements of the same sample aliquot [1] | Measurements from different individual biological sources within the same group [1] |

| Primary Purpose | Estimate system precision (pipetting, instrument variation) [1] | Estimate biological variation within a group [1] |

| Controls For | Experimental/analytical noise | Biological heterogeneity |

| Example | Same cDNA sample run in triplicate wells on a qPCR plate [1] | Three different mice from the same treatment group, each analyzed separately [1] |

| Informs | Reproducibility of the assay technique | Generalizability of the finding to the population |

The relationship and purpose of these replicates within a qPCR experimental workflow can be visualized as follows:

Determining the Optimal Number of Replicates

Determining the correct number of replicates is a critical decision that balances statistical power with practical constraints like cost, time, and sample availability.

The Gold Standard: Prioritizing Biological Replication

The consensus in the field is that biological replication is non-negotiable for making statistically valid inferences about a population [4]. An experiment should ideally encompass at least three independent biological replicates of each treatment or condition. Biological variation is often the largest source of variability in gene expression studies, and without sufficient biological replicates, it is impossible to determine if an observed effect is consistent or merely anecdotal. Increasing the number of biological replicates enhances the power of statistical tests to discriminate smaller, biologically relevant fold changes in gene expression [1] [21].

The Role of Technical Replication

For technical replicates, triplicates are a commonly selected and practical number in basic research [1]. Running technical replicates (e.g., duplicates or triplicates) for each biological sample provides confidence in the measurement for that specific sample. It allows for the detection of failed reactions or significant pipetting errors and provides a more precise mean Cq value for the biological replicate. However, it is generally recognized that investing resources in increasing the number of biological replicates provides a greater return in statistical power than running a large number of technical replicates for a few biological samples.

The Interplay Between Replicates and Precision

The precision of a qPCR experiment, measured by metrics like the Coefficient of Variation (CV), is directly impacted by replication. Improved precision allows researchers to discriminate smaller differences in nucleic acid copy numbers. Increasing the number of both technical and biological replicates tends to reduce the impact of random variation, leading to a more accurate estimate of the true mean [1]. The following table provides a summary of recommended replicate numbers based on different experimental goals:

Table 2: Replication Strategy Guidance for Different qPCR Applications

| Experimental Goal | Minimum Biological Replicates | Recommended Technical Replicates | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression (General) | 3 per group [4] | 2-3 per sample [1] [4] | Balance between cost and reliability. |

| Detecting Small Fold Changes | >5 per group [1] [21] | 2-3 per sample | More biological replicates increase power to detect subtle differences. |

| Method Validation / Assay Precision | 1 (to start) | ≥3 to estimate CV [1] | Focus is on measuring system variation, not biological difference. |

| High-Throughput Screening | 3 per group | 2 (to conserve plates & reagents) | Requires rigorous assay validation beforehand. |

A Practical Experimental Protocol

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for a standard relative quantification qPCR experiment, incorporating best practices for replication.

Experimental Design and Sample Maximization

- Step 1: Define Biological Groups and Replicates. Determine the experimental groups (e.g., Control, Treated). Plan for a minimum of three independent biological replicates per group. This is the foundation of the experiment [4].

- Step 2: Plate Design. Ideally, all samples for a full experiment (all biological replicates, all target genes, and all reference genes) should be analyzed on a single qPCR plate to avoid inter-plate variation. If multiple plates are unavoidable, employ a randomized block design where each plate contains a complete set of one biological replicate from each group. Use Inter-Run Calibrators (IRCs) on each plate to correct for plate-to-plate variation [4].

- Step 3: Assign Technical Replicates. Within the plate design, assign two or three technical replicates for each combination of biological sample and assay (target gene and reference gene) [4].

Laboratory Workflow: From RNA to Cq

- Step 4: Nucleic Acid Extraction. Extract total RNA from each biological sample independently using a validated method. Treat samples with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination. Assess RNA concentration, purity (A260/A280 ratio), and integrity (e.g., via agarose gel electrophoresis) [22] [23].

- Step 5: Reverse Transcription. Convert equal amounts of total RNA (e.g., 1 µg) from each sample to cDNA using a high-efficiency reverse transcriptase kit. Use a mixture of oligo-dT and random hexamer primers for comprehensive coverage. Keep all reaction conditions consistent across samples [23].

- Step 6: qPCR Setup.

- Precision Pipetting: Use calibrated pipettes and ensure tips fit snugly. Pipette master mixes first to minimize variation. For probe-based assays, ensure the final reaction volume is at least 20 µL to avoid optical mixing issues [1].

- Reaction Composition: Each reaction should contain: cDNA template, forward and reverse primers, probe (or intercalating dye), and PCR master mix.

- Plate Sealing and Centrifugation: After loading, seal the plate properly and centrifuge to collect all liquid at the bottom of the wells and remove air bubbles [1].

- Step 7: qPCR Run. Use the following standard cycling conditions, optimized for your instrument and reagent system:

- UDG incubation (if applicable): 50°C for 2 minutes

- Polymerase activation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- Amplification (40 cycles): 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation) → 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension; acquire fluorescence)

Data Analysis and Statistical Procedures

- Step 8: Data Quality Control and Preprocessing.

- Baseline Correction: Manually set the baseline cycles to the early phases where no amplification is detected (e.g., cycles 5-15) to correct for background fluorescence variations [24].

- Threshold Setting: Set the fluorescence threshold within the exponential phase of all amplifications where the amplification curves are parallel. This ensures consistent Cq determination across samples [24].

- Efficiency Estimation: Calculate the amplification efficiency (E) for each assay. This can be done via a standard curve of serial dilutions or using algorithms like LinReg that analyze the raw amplification curves. The mean efficiency per assay is typically used for subsequent calculations [21] [4].

- Step 9: Calculation of Normalized Relative Quantities.

- For each biological replicate, calculate the mean Cq of its technical replicates for both the Gene of Interest (GOI) and Reference Gene(s).

- Calculate the normalized relative quantity (NRQ) using the efficiency-adjusted model, such as the Pfaffl method [24]: ( NRQ = \frac{(E{GOI})^{-\Delta Cq{GOI}}}{(E{Ref})^{-\Delta Cq{Ref}}} ) Where (\Delta Cq) is the difference in Cq between treated and control samples for each biological replicate.

- Step 10: Statistical Analysis of Biological Variation.

- Log Transformation: To stabilize variance and normalize the data, apply a log transformation (base 2 or natural) to the NRQ values. The transformed values are referred to as Cq' [4].

- Hypothesis Testing: Perform appropriate statistical tests on the Cq' values of the biological replicates. For two-group comparisons, use a t-test. For more complex designs (e.g., multiple groups or factors), use Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The unit of replication for these tests is the biological replicate, not the technical replicate [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a Robust qPCR Experiment

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Instrument | Instrument for thermal cycling and fluorescence detection. | Applied Biosystems ViiA 7, QuantStudio 7, Bio-Rad CFX [22] |

| Probe-based qPCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer, enzymes, and dNTPs for probe-based detection. | Provides superior specificity over dye-based methods [22] |

| TaqMan Assays | Pre-optimized primer and probe sets for specific targets. | Ideal for high-throughput and multiplexing applications [22] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For isolation of high-quality, intact total RNA. | Qiagen RNeasy, TRIzol LS Reagent [25] [23] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | For synthesis of first-strand cDNA from RNA templates. | Use kits with a mix of oligo-dT and random hexamers [23] |

| Validated Reference Genes | Genes with stable expression for data normalization. | Must be stability-tested for your specific sample set (e.g., using geNorm, NormFinder) [4] [23] |

| Nuclease-free Water | Water certified to be free of RNases and DNases. | Essential for preventing nucleic acid degradation. |

| Optical Plates & Seals | Plates and adhesive films designed for qPCR fluorescence reading. | Ensure compatibility with the qPCR instrument. |

Connecting to Broader Research: qPCR and RNA-Seq

The principles of robust experimental design, particularly adequate biological replication, are universally critical in genomics, whether using qPCR or RNA-Seq. RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome but comes with its own set of computational and normalization challenges [26]. qPCR remains the gold standard for validating RNA-Seq findings due to its superior sensitivity, dynamic range, and precision for a limited number of targets [25] [26]. The relationship between these technologies is synergistic. A well-designed RNA-Seq study with sufficient biological replication (e.g., n≥3) can identify candidate differentially expressed genes, which are then confirmed with a rigorously designed qPCR experiment on independent samples, also with adequate biological replication. This combined approach leverages the strengths of both technologies to generate reliable and impactful conclusions in gene expression research.

In the context of a broader thesis on biological versus technical replicates in qPCR and RNA-Seq research, careful experimental design forms the cornerstone of reliable transcriptomic analysis. The fundamental challenge in any gene expression study lies in accurately distinguishing biological signal from experimental noise. While quantitative PCR (qPCR) has long provided a sensitive method for targeted gene expression analysis, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) offers an unbiased, genome-scale perspective on the transcriptome. However, this comprehensive view introduces additional complexity in experimental design, particularly regarding replication strategy and sequencing depth. The decision between biological replicates (measurements across different biological subjects) and technical replicates (repeated measurements of the same biological sample) carries profound implications for statistical power, generalizability, and cost-efficiency. This application note synthesizes current evidence and best practices to guide researchers in making informed design choices that ensure robust and interpretable RNA-Seq results, with particular relevance for drug development applications where accurate detection of differential expression directly impacts decision-making.

Core Principles: Biological vs. Technical Replication

Definitions and Distinct Purposes

In RNA-Seq experiments, understanding the distinction between biological and technical replicates is paramount, as each addresses different sources of variability. Biological replicates are measurements taken from distinct biological entities (e.g., different animals, independently cultured cells, or human subjects) that capture the natural variation present in the population under study [2]. They are essential for ensuring that findings are generalizable beyond the specific samples measured. In contrast, technical replicates involve multiple measurements of the same biological sample through the experimental workflow (e.g., sequencing the same library multiple times or preparing multiple libraries from the same RNA extraction) [2]. Technical replicates primarily assess variability introduced by laboratory procedures and sequencing platforms rather than biological variation.

Table 1: Comparison of Replicate Types in RNA-Seq Experiments

| Aspect | Biological Replicates | Technical Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Different biological samples or entities | Same biological sample, measured multiple times |

| Purpose | Assess biological variability and ensure findings are generalizable | Assess technical variation from workflows and sequencing |

| Example | 3 different animals in each treatment group | 3 sequencing runs for the same RNA sample |

| Addresses | Natural variation between individuals/subjects | Measurement error, library prep, and sequencing variability |

| Priority | Essential for biological inference | Useful for quality control but secondary to biological replication |

Relative Importance in Experimental Design

Multiple studies consistently demonstrate that biological replication provides substantially greater value than technical replication for detecting differentially expressed genes. Biological replicates enable researchers to estimate the natural variation in gene expression within a population, which is crucial for statistical tests that identify expression changes between conditions [27] [28]. Technical reproducibility in RNA-Seq is generally considered excellent when using consistent laboratory protocols, making technical replicates less critical for most study designs [29]. In fact, for a fixed budget, prioritizing resources toward additional biological replicates rather than technical replicates or extreme sequencing depth typically yields more statistically powerful experiments [27] [28].

Quantitative Guidelines: Replicate Numbers and Sequencing Depth

Recommended Replicate Numbers

The number of biological replicates required depends on the expected effect size, biological variability, and desired statistical power. While more replicates always improve power, practical considerations often dictate a balance between statistical rigor and resource constraints.

Table 2: Recommended Replicate Numbers for RNA-Seq Experiments

| Scenario | Minimum Replicates | Optimal Replicates | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| General research | 3 per condition [30] [6] | 4-8 per condition [2] [28] | 3 replicates enable basic variability estimation; 4+ substantially improve reproducibility and power |

| Pilot studies | 2-3 per condition | 3-4 per condition | Provides preliminary data for power calculations in subsequent larger studies |

| High-variability systems | 4 per condition | 6-8 per condition [2] | Compensates for substantial biological variation (e.g., human samples, complex tissues) |

| Cost-constrained screens | 3 per condition | 4 per condition | Balances statistical needs with throughput requirements |

| Toxicology/Drug discovery | 3 per dose | 4 per dose [28] | Enhances reproducibility of dose-response patterns and benchmark dose estimates |

Evidence strongly indicates that increasing biological replicates significantly enhances the detection of differentially expressed genes. One toxicogenomics study found that with only 2 replicates, over 80% of differentially expressed genes were unique to specific sequencing depths, indicating high variability. Increasing to 4 replicates substantially improved reproducibility, with over 550 genes consistently identified across most depths [28]. Similarly, research has demonstrated that power to detect differential expression improves markedly when the number of biological replicates increases from n = 2 to n = 5 [27].

Optimal Sequencing Depth Recommendations

Sequencing depth requirements vary based on the organism, transcriptome complexity, and specific research objectives. Adequate depth ensures sufficient coverage to detect and quantify transcripts of interest, particularly those expressed at low levels.

Table 3: Recommended Sequencing Depth Based on Experimental Goals

| Application | Recommended Depth | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard differential expression (3' mRNA-Seq) | 1-5 million reads/sample [19] | Sufficient for gene-level quantification when reads localize to 3' end |

| Standard differential expression (whole transcriptome) | 20-30 million reads/sample [30] [6] | Balances cost with detection sensitivity for most protein-coding genes |

| Total RNA-Seq (including non-coding RNA) | 25-60 million reads/sample [6] | Additional depth needed for comprehensive coverage of diverse RNA species |

| Isoform analysis & splice variants | 30+ million reads/sample | Higher depth required to resolve transcript structures |

| Large-scale screening studies | 10-20 million reads/sample [6] | Enables cost-effective profiling of many samples |

Strategic Balance Between Replicates and Depth

When facing budget constraints, researchers must often choose between sequencing more biological replicates at lower depth or fewer replicates at greater depth. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that biological replication generally provides better returns on investment than increased sequencing depth [27] [28]. One study found that sequencing depth could be reduced to as low as 15% without substantial impacts on false positive or true positive rates, whereas reducing replicate numbers significantly diminished statistical power [27]. Another toxicogenomics study concluded that replication had a greater influence than depth for optimizing detection power, with higher replicates increasing the rate of overlap of benchmark dose pathways and precision of median benchmark dose estimates [28].

Practical Protocols and Implementation

Workflow for RNA-Seq Experimental Design

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in designing a robust RNA-Seq experiment, emphasizing replication and sequencing strategies:

Protocol for Replicate Planning and Sample Preparation

Step 1: Define Experimental Units and Conditions

- Clearly identify the biological unit of interest (individual organism, cell culture, tissue sample)

- Define all conditions and time points for comparison

- Ensure true biological independence for biological replicates

Step 2: Determine Replication Strategy

- Allocate resources for minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition [30] [6]

- Increase to 4-6 replicates for studies with anticipated high variability

- Consider including extra samples to account for potential quality control failures

Step 3: Randomization and Batch Effects Mitigation

- Randomly assign samples to processing batches to avoid confounding technical and biological effects

- Process samples in balanced batches that include representatives from all experimental conditions

- Include control samples in each batch to monitor technical variability

Step 4: Sample Collection and Storage

- Collect biological replicates following standardized protocols to minimize introduction of technical artifacts

- Process samples uniformly during RNA extraction and library preparation

- Use appropriate storage conditions (e.g., -80°C in RNase-free plates with proper sealing) [18]

Step 5: Library Preparation and Quality Control

- Select appropriate library preparation method based on research goals (3' mRNA-Seq vs. whole transcriptome)

- Perform rigorous RNA quality assessment (e.g., RIN > 8 for mRNA sequencing) [6]

- Use unique dual indices for multiplexing to enable sample pooling and sequencing

Protocol for Sequencing Depth Optimization

Step 1: Preliminary Depth Estimation

- For standard differential expression: target 20-30 million reads per sample for whole transcriptome [30]

- For 3' mRNA-Seq: 1-5 million reads may be sufficient [19]

- Adjust based on transcriptome complexity and expression dynamic range

Step 2: Pilot Studies for Depth Calibration

- When possible, conduct pilot sequencing with 1-2 samples at higher depth

- Use saturation analysis to determine optimal depth for full study

- Consider published datasets from similar biological systems as reference

Step 3: Multiplexing and Lane Allocation

- Multiplex samples using barcoding to maximize throughput and minimize batch effects [27]

- Balance samples across sequencing lanes to avoid confounding technical effects

- When multiple lanes are required, ensure all conditions are represented in each lane

Step 4: Quality Assessment and Potential Resequencing

- Monitor sequencing quality metrics (Q scores, base composition)