Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to RNA-Seq and qPCR Correlation in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on correlating RNA-Seq and qPCR data, the established gold standard for gene expression validation.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to RNA-Seq and qPCR Correlation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on correlating RNA-Seq and qPCR data, the established gold standard for gene expression validation. It covers foundational principles, from the distinct advantages and limitations of each technology to their respective roles in diagnostic and clinical pipelines. The content delves into methodological best practices for experimental design, including sample preparation, choice of clinically accessible tissues, and the critical selection of stable reference genes. A significant focus is given to troubleshooting common technical challenges, such as the impact of PCR duplicates in RNA-Seq and the pitfalls of using traditional housekeeping genes in qPCR. Finally, the guide synthesizes benchmarking studies that quantify the correlation between platforms, offering concrete strategies for data integration and validation to ensure robust, reproducible results in research and clinical applications.

RNA-Seq and qPCR: Understanding the Gold Standard and Its Role in Modern Transcriptomics

Why qPCR Remains the Gold Standard for Validating RNA-Seq Findings

In the evolving landscape of genomic research, next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to profile transcriptomes comprehensively. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a powerful discovery tool, enabling researchers to detect novel transcripts, identify alternatively spliced isoforms, and quantify gene expression across the entire genome without prior knowledge of sequence information [1]. Despite these advancements, quantitative PCR (qPCR) maintains its position as the unequivocal gold standard for validating RNA-Seq findings, forming a critical checkpoint in the gene expression analysis workflow. This enduring status stems from qPCR's unparalleled sensitivity, reproducibility, and technical accessibility, which together provide the verification necessary to confirm discoveries made through high-throughput screening.

The relationship between these two technologies is not competitive but fundamentally complementary. RNA-Seq excels in hypothesis generation, offering an unbiased view of the transcriptome, while qPCR provides the precise, targeted validation required to confirm these findings with the highest level of confidence [2]. This symbiotic relationship is particularly crucial in research with significant implications for drug development and clinical applications, where data integrity is paramount. The scientific community relies on this validation paradigm to ensure that RNA-Seq-based discoveries are not artifacts of the complex computational pipelines required for sequencing data analysis but reflect genuine biological signals worthy of further investigation and investment.

Quantitative Evidence: Establishing Correlation and Concordance

Independent benchmarking studies consistently demonstrate strong correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR data, providing the empirical foundation for this validation paradigm. A comprehensive study comparing five common RNA-Seq processing workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes revealed high expression correlations, with Pearson correlation coefficients (R²) ranging from 0.798 to 0.845 across different computational methods [3]. When comparing gene expression fold changes between samples, the correlations were even stronger, with R² values between 0.927 and 0.934, indicating excellent concordance in relative quantification.

However, a more nuanced analysis reveals important considerations for validation strategies. When examining differential expression between samples, approximately 85% of genes showed consistent results between RNA-Seq and qPCR data across various workflows [3]. The remaining 15% of genes with discordant results typically shared specific characteristics: they tended to be smaller, had fewer exons, and were expressed at lower levels compared to genes with consistent measurements. This systematic pattern highlights the importance of strategic qPCR validation, particularly for specific gene sets that may be prone to quantification discrepancies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Workflows Against qPCR Benchmark

| RNA-Seq Workflow | Expression Correlation (R²) | Fold Change Correlation (R²) | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 16.8% |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 17.2% |

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% |

Data adapted from benchmarking study comparing RNA-seq workflows using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR expression data [3].

Methodological Foundations: Technical Advantages of qPCR for Validation

Precision, Dynamic Range, and Sensitivity

The status of qPCR as a validation tool rests on several distinct technical advantages that make it uniquely suited for confirmation of gene expression changes. While RNA-Seq demonstrates impressive sensitivity for a high-throughput technology, qPCR operates with a wider dynamic range and lower quantification limits for targeted analysis [4]. This technical superiority is particularly evident when analyzing low-abundance transcripts, where qPCR's amplification efficiency provides more reliable quantification than the read-counting approach of RNA-Seq. For the specific application of validating a limited number of targets identified through discovery-based sequencing, qPCR offers uncompromising data quality that remains the benchmark against which other technologies are measured.

The precision of qPCR is further enhanced by its independence from complex computational processing. RNA-Seq data must undergo multiple bioinformatic steps including alignment, normalization, and gene counting, with each step introducing potential sources of variation depending on the algorithms and parameters selected [5]. In contrast, qPCR quantification relies on direct fluorescence detection of amplified products, creating a more direct relationship between signal and transcript abundance that is not mediated by computational decisions. This methodological simplicity translates to more reliable and interpretable results for targeted gene expression analysis.

Practical Accessibility and Efficiency

From a practical standpoint, qPCR offers significant advantages in terms of workflow efficiency and accessibility for validation studies. The technology benefits from ubiquitous instrumentation in molecular biology laboratories and straightforward data analysis workflows that are familiar to most researchers [2]. This accessibility contrasts sharply with RNA-Seq, which often requires specialized bioinformatics expertise and computational resources that may not be readily available in all research settings. The time investment for validation is also considerably less with qPCR, with typical experiments requiring only 1-3 days from sample preparation to data analysis compared to potentially weeks for RNA-Seq when factoring in library preparation, sequencing, and data processing [2] [4].

The economic argument for qPCR validation is equally compelling. For studies involving smaller numbers of targets (typically ≤20 genes), qPCR is significantly more cost-effective than targeted RNA-Seq approaches [2] [1]. This cost efficiency enables researchers to validate their findings across larger sample sets or with more extensive technical replication, strengthening the statistical power of their conclusions without prohibitive expense. The combination of technical superiority, practical accessibility, and economic efficiency creates a compelling case for qPCR's continued role as the preferred validation methodology.

Implementation: Experimental Design for Effective Validation

Reference Gene Selection from RNA-Seq Data

A critical prerequisite for reliable qPCR validation is the selection of appropriate reference genes for data normalization. Traditional approaches often rely on presumed "housekeeping" genes such as ACTB and GAPDH, but evidence shows these genes can demonstrate significant expression variability under different experimental conditions [6]. Modern best practices leverage RNA-Seq data itself to identify optimal reference genes using computational tools specifically designed for this purpose.

The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software represents one such approach, employing a systematic filtering methodology to identify optimal reference genes directly from transcriptome data [6]. The algorithm applies sequential filters to identify genes with stable, high expression across all experimental conditions:

- Expression greater than zero in all samples

- Low variability between libraries (standard deviation of log₂(TPM) < 1)

- No exceptional expression in any library (within 2-fold of mean log₂ expression)

- High expression level (mean log₂(TPM) > 5)

- Low coefficient of variation (< 0.2)

This data-driven approach to reference gene selection significantly improves normalization accuracy compared to reliance on traditional housekeeping genes, which may exhibit unexpected variability in specific experimental contexts [6] [7].

Technical Replication and Quality Control

Robust qPCR validation requires careful attention to experimental design and quality control measures. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring reliability and repeatability of qPCR results [4]. Key considerations include implementing appropriate technical and biological replication, verifying PCR efficiency for each assay, and including necessary controls to detect potential contamination or amplification artifacts.

When designing validation experiments, researchers should prioritize genes that represent the dynamic range of expression changes observed in RNA-Seq data, including both highly differentially expressed genes and those with more modest fold changes. This approach tests the robustness of the original findings across expression levels. Additionally, the validation set should include genes with potential biological significance to the research question, ensuring that key conclusions are supported by orthogonal validation.

Advanced Applications: qPCR Validation in Complex Systems

The utility of qPCR validation extends beyond standard gene expression studies to more complex applications where its precision provides particular value. In studies of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) expression, for example, qPCR has demonstrated important advantages in quantifying expression levels of these highly polymorphic genes [8]. Research comparing qPCR and RNA-Seq for HLA class I gene expression revealed only moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between the two technologies, highlighting the challenges of accurately quantifying these genes using short-read sequencing approaches and underscoring the importance of orthogonal validation [8].

In cancer diagnostics, qPCR continues to play a crucial role in translating RNA-Seq discoveries into clinically applicable assays. A recent study on ovarian cancer detection developed a qPCR-based algorithm using platelet-derived RNA that achieved 94.1% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity [9]. This approach successfully bridged the gap between discovery-phase RNA-Seq findings and practical diagnostic application, demonstrating how qPCR validation facilitates the translation of sequencing data into clinically implementable tools. The resulting assay provided an accessible, cost-effective alternative to NGS for early cancer detection while maintaining high accuracy.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Data

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcription Kits | SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System | Converts RNA to cDNA for qPCR analysis |

| qPCR Assays | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Target-specific primers and probes for precise quantification |

| Reference Gene Assays | Commercially available or custom-designed assays for stable genes | Enables accurate normalization of target gene expression |

| qPCR Master Mixes | TaqMan Universal Master Mix | Provides enzymes and buffers for efficient amplification |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA kits | Verifies RNA integrity prior to cDNA synthesis |

| Pre-spotted Assay Plates | TaqMan Array Cards | Enables high-throughput validation of multiple targets |

The relationship between qPCR and RNA-Seq represents a powerful synergy in modern genomic research, with each technology playing distinct yet complementary roles. RNA-Seq provides an unparalleled capacity for discovery,

offering a hypothesis-free approach to transcriptome characterization that can identify novel transcripts, splice variants, and differentially expressed genes across the entire genome [1]. qPCR, in turn, delivers the verification necessary to confirm these findings with the highest level of confidence, leveraging its superior sensitivity, reproducibility, and practical accessibility for targeted analysis.

This validation paradigm remains essential across diverse research contexts, from basic biological investigations to translational studies with clinical applications. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, offering ever-greater throughput and sensitivity, the need for reliable validation through orthogonal methods like qPCR becomes increasingly important rather than diminished. The scientific standard of confirming high-throughput discoveries with targeted, highly precise methodologies ensures the integrity of genomic research and its subsequent applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Looking forward, the continued integration of qPCR and RNA-Seq will drive advances in both technologies, with each informing and improving the other. Best practices in experimental design will increasingly leverage the strengths of both approaches, using RNA-Seq for comprehensive discovery and qPCR for rigorous validation of key findings. This collaborative relationship, built on the recognized strengths of each technology, will continue to support the generation of reliable, reproducible genomic data that moves scientific understanding forward while maintaining the highest standards of evidence.

In the field of genomic research, the combined use of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) represents a powerful synergistic methodology. RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-scale discovery platform, while qPCR delivers precise, sensitive validation of key findings. This whitepaper delineates the technical and strategic frameworks for integrating these technologies, underscoring their complementary nature within correlation studies. We present experimental protocols, analytical workflows, and empirical data demonstrating how this tandem approach enhances the reliability and translational potential of transcriptomic research, ultimately providing researchers and drug development professionals with a robust pipeline for gene expression analysis.

Transcriptome analysis is a cornerstone of modern biological research, driving advancements in drug discovery, disease mechanism elucidation, and biomarker identification. While RNA-Seq has emerged as the premier tool for comprehensive, hypothesis-generating discovery due to its ability to profile the entire transcriptome without prior sequence knowledge, qPCR remains the gold standard for validating specific gene expression changes with unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [10] [11]. This complementary relationship is not sequential but integrative, with each technology informing and strengthening the other within a cohesive analytical strategy.

The synergy arises from the inherent strengths and limitations of each method. RNA-Seq's broad, unbiased nature is ideal for identifying novel transcripts, splice variants, and gene fusions, but it can be resource-intensive and requires sophisticated bioinformatics support [12] [13]. Conversely, qPCR is highly targeted, cost-effective for analyzing a limited number of genes, and technically accessible, but it lacks the scalability for discovery [6] [11]. When used together, they form a complete analytical pipeline: RNA-Seq illuminates the full transcriptional landscape and pinpoints candidate genes of interest, while qPCR confirms these findings with orthogonal validation, providing the rigorous verification often required for high-impact publications and clinical applications [10] [14].

Technical Foundations: Methodological Principles and Comparisons

RNA-Seq: The Discovery Engine

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) utilizes next-generation sequencing (NGS) to catalogue and quantify RNA populations in a sample. The process begins with converting RNA into a library of complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments, followed by adapter ligation, amplification, and high-throughput sequencing. The resulting millions of short reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome, and mapped to genes to generate a count table [12]. This workflow enables the detection of both known and novel features—including gene isoforms, single nucleotide variants, and gene fusions—in a single assay without the limitation of prior knowledge [13].

A key advantage of RNA-Seq is its extremely broad dynamic range, which allows for the sensitive and accurate measurement of gene expression across transcripts that vary in abundance by several orders of magnitude [13]. This makes it exceptionally powerful for exploratory research. However, its accuracy can be influenced by factors such as read depth, alignment algorithms, and data normalization methods. Notably, a benchmark study comparing multiple RNA-Seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data found that while overall concordance was high, a small fraction of genes (approximately 1.8%) showed severe non-concordance; these genes were typically lower expressed and shorter, highlighting a potential limitation for specific gene sets [3] [10].

qPCR: The Validation Gold Standard

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) measures the expression levels of a predefined set of genes by detecting PCR amplification in real-time using fluorescent reporters. The technique relies on the principle that the cycle at which fluorescence crosses a threshold (Cq value) is proportional to the starting quantity of the target transcript. For gene expression validation, qPCR is often performed using reverse transcription to first generate cDNA (thus, RT-qPCR) [6].

qPCR's principal strengths lie in its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. It is capable of detecting very low-abundance transcripts and can distinguish between closely related splice variants with well-designed assays. Furthermore, it is rapid, cost-effective for small numbers of targets, and requires minimal RNA input [11]. A critical, often overlooked step in qPCR experimental design is the selection of appropriate reference genes for data normalization. These should exhibit stable, high expression across all biological conditions in the study. Traditionally, housekeeping genes like GAPDH and ACTB have been used, but their expression can vary under certain conditions. Software tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) have been developed to identify the most stable reference genes directly from RNA-seq data, thereby reducing errors in qPCR quantification and ensuring more reliable interpretation of results [6].

Comparative Analysis of Technologies

Table 1: Strategic comparison of RNA-Seq and qPCR for gene expression analysis.

| Feature | RNA-Seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Discovery, hypothesis generation | Validation, confirmation |

| Throughput | Whole transcriptome (high) | 1-10s of genes (low) |

| Dynamic Range | Extremely broad [13] | Broad |

| Sensitivity | High | Very high [11] |

| Ability to Detect Novel Features | Yes (e.g., novel transcripts, fusions) [13] | No |

| Sample RNA Input | Moderate to High (e.g., 10 ng–1 µg) [13] | Low |

| Typical Workflow Duration | Several days to weeks | 1-3 days [11] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | High [12] | Low |

| Cost per Sample | High | Low for a few targets [11] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | High, but with a small set of problematic genes [3] [10] | Very high (Gold standard) |

The Integrated Workflow: From Discovery to Confirmation

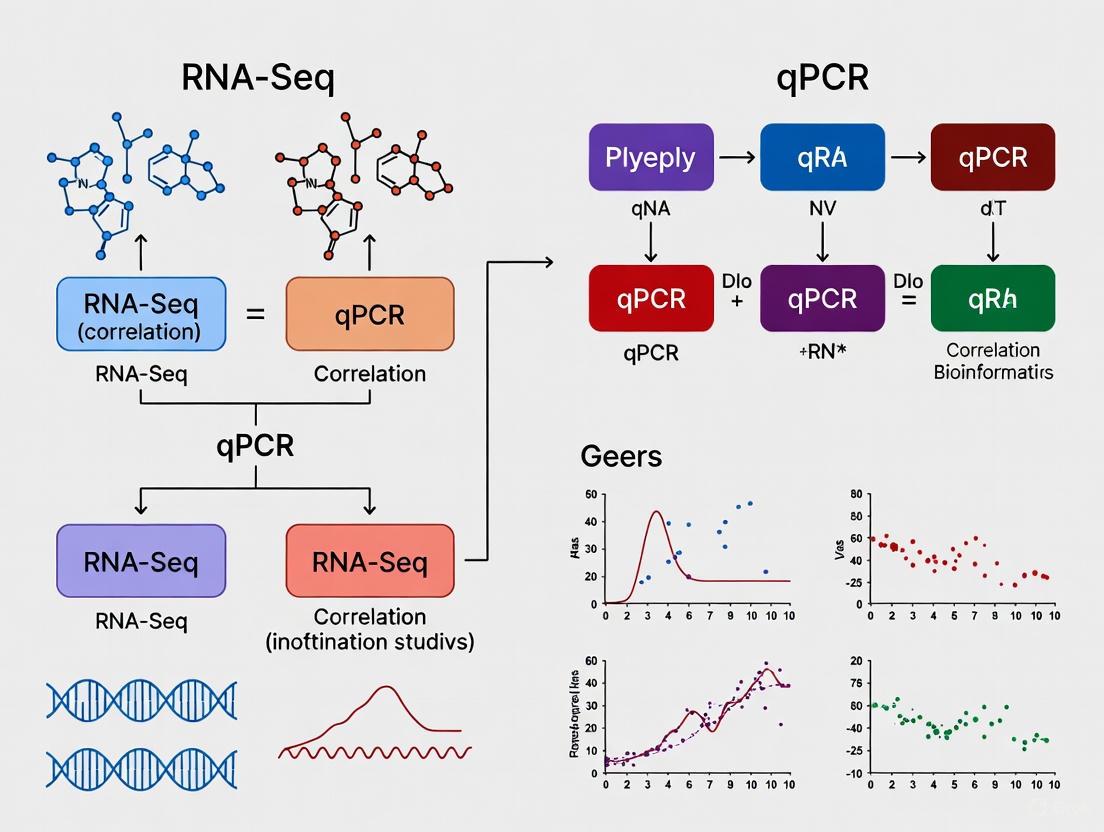

A robust transcriptomic study strategically leverages both RNA-Seq and qPCR. The following workflow diagram and subsequent text outline the key stages of this integrated approach.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for RNA-Seq discovery and qPCR confirmation.

RNA-Seq Discovery Phase

The process begins with a rigorously designed RNA-Seq experiment. Key considerations include minimizing batch effects by processing control and experimental samples simultaneously during RNA isolation, library preparation, and sequencing runs [12]. After sequencing, raw reads are demultiplexed, aligned to a reference genome (e.g., using STAR or TopHat2), and mapped to genes (e.g., using HTSeq) to generate a raw count table [12] [3].

Differential expression analysis is then performed using statistical methods based on the negative binomial distribution, such as edgeR or DESeq [15]. This step identifies a list of candidate genes that are significantly altered between experimental conditions. To ensure a conservative candidate list, some researchers cross-reference results from multiple analysis tools [15]. It is also crucial to perform quality control checks, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to assess intra- and inter-group variability and identify potential outliers [12].

Candidate Gene Selection for Validation

The transition from RNA-Seq to qPCR requires judicious selection of candidate genes for validation. This list should not only include top differentially expressed genes but also represent key biological pathways relevant to the study's hypothesis. Additionally, selecting genes with a range of expression levels and fold changes is prudent.

This is also the stage to select optimal reference genes for qPCR normalization. Tools like GSV software can analyze the RNA-Seq dataset itself (using TPM values) to identify genes that are highly and stably expressed across all samples, thereby providing a data-driven approach to choosing the best reference genes and avoiding traditionally used but potentially unstable housekeeping genes [6].

qPCR Confirmation Phase

With candidates identified, specific and efficient qPCR assays are designed. The TaqMan system, which uses a fluorescent probe for highly specific detection, is often employed in validation studies [14]. RNA from the original samples is reverse-transcribed to cDNA, and the expression of candidate and reference genes is quantified.

The qPCR data is analyzed using the ΔΔCt method to calculate log2 fold changes between conditions [14]. A successful validation is demonstrated by a strong correlation between the fold changes observed by RNA-Seq and qPCR. For example, a study on circulating cell-free RNA in colorectal cancer used TaqMan qPCR to validate the expression patterns of biomarkers HPGD, PACS1, and TDP2 that were initially discovered by RNA-Seq, confirming their clinical relevance [14].

Quantitative Concordance and Analytical Validation

Empirical evidence strongly supports the high concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR, justifying their complementary use. A landmark benchmarking study compared five RNA-Seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes. The results demonstrated high fold change correlations between RNA-Seq and qPCR across all workflows (Pearson R² ~0.93) [3].

Table 2: Summary of key concordance metrics between RNA-Seq and qPCR from benchmarking studies.

| Metric | Result | Interpretation & Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Fold Change Correlation | R² ≈ 0.93 [3] | High overall agreement in quantifying expression differences. |

| Non-Concordant Genes | 15-20% of genes [3] [10] | Disagreement mostly in genes with small fold changes. |

| Non-Concordant Genes with FC > 2 | ~1.8% of all genes [10] | Represents a small but critical set of severe discrepancies. |

| Profile of Problematic Genes | Typically lower expressed and shorter [3] | Suggests caution is warranted when interpreting data for such genes. |

Further analysis of the "non-concordant" genes reveals that the vast majority (≈93%) have a fold change difference (ΔFC) of less than 2 between the two methods. This indicates that most discrepancies occur for genes with relatively small expression changes. Only a very small fraction (≈1.8%) of genes show severe non-concordance (ΔFC > 2), and these are characterized by low expression levels and shorter gene length [3] [10]. This evidence supports the practice of using qPCR to validate RNA-Seq findings, particularly for key genes on which major conclusions are based, especially if those genes fall into this potentially problematic category.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of this integrated workflow relies on a suite of reliable reagents and kits. The following table catalogues key solutions used in the experiments cited within this whitepaper.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for integrated RNA-Seq and qPCR workflows.

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Simultaneous isolation of DNA and RNA from a single sample. | Integrated DNA/RNA-seq from fresh-frozen tumors [16]. |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit (Illumina) | Library preparation for RNA-Seq, enriching for polyadenylated RNA. | RNA-Seq library construction from fresh-frozen tissue [16]. |

| SureSelect XTHS2 (Agilent) | Hybrid-capture based library prep kit. | RNA-Seq library construction from challenging FFPE samples [16]. |

| miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen) | Purification of cell-free and total RNA from biofluids. | Isolation of circulating cell-free RNA from plasma [14]. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher) | Pre-designed, optimized primer-probe sets for qPCR. | Validation of candidate biomarkers (e.g., HPGD, PACS1) [14]. |

| PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara) | High-performance reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA. | cDNA synthesis for downstream qPCR analysis [14]. |

The strategic partnership between RNA-Seq and qPCR provides a robust framework for transcriptomic analysis that is greater than the sum of its parts. RNA-Seq serves as a powerful, unbiased discovery engine, illuminating the vast and complex transcriptional landscape. qPCR, in turn, provides a precise and reliable mechanism for confirming key findings, adding a layer of rigor and confidence essential for scientific publication and translational application.

This guide has outlined the methodological principles, integrated workflow, and empirical evidence supporting this synergy. By adopting this complementary approach—using RNA-Seq to generate comprehensive datasets and guide the intelligent selection of reference genes, and qPCR to orthogonally validate critical results—researchers and drug developers can maximize the accuracy, impact, and translational potential of their gene expression studies. As the field continues to evolve, this tandem methodology will remain a cornerstone of rigorous transcriptomic research.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative technology in molecular biology, enabling groundbreaking applications across both rare disease diagnostics and oncology. This technical guide explores how RNA-seq elucidates the functional consequences of genetic variants, moving beyond the static information provided by DNA analysis to dynamic transcriptome profiling. By detailing specific experimental protocols, benchmarking data, and integration with artificial intelligence, this review provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals implementing RNA-seq in clinical and research settings. The content is framed within the broader context of correlating RNA-seq findings with qPCR validation, establishing a critical pathway for biomarker verification and clinical translation.

The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing has fundamentally altered the diagnostic and research landscape for genetic disorders and cancer. While exome and genome sequencing identify potential pathogenic variants, they often fail to provide conclusive functional evidence, leaving over half of diagnostic evaluations without definitive results [17]. RNA-seq directly addresses this gap by quantifying gene expression, detecting aberrant splicing, and identifying novel transcripts, providing a dynamic view of cellular function that static DNA analysis cannot achieve.

In clinical genomics, RNA-seq increases diagnostic yields by 7.5%–36% beyond DNA testing alone by identifying pathological changes at the transcript level [17]. Similarly, in oncology, RNA-seq enables the discovery of novel biomarkers, characterization of tumor heterogeneity, and prediction of treatment responses through comprehensive transcriptome profiling [18]. The technology's versatility extends from single-gene expression analysis to full transcriptome sequencing, making it indispensable for both focused clinical diagnostics and exploratory biomarker discovery.

RNA-Seq in Rare Disease Diagnosis

Diagnostic Utility and Clinical Impact

RNA-seq has demonstrated significant value in clarifying variants of uncertain significance (VUS), particularly those affecting splicing and gene expression. Clinical studies show that RNA-seq can reclassify approximately 50% of eligible variants identified through exome or genome sequencing, providing critical functional evidence for molecular diagnoses [19]. When applied to specific clinical scenarios—such as evaluating putative splice variants, assessing canonical splice site variants with atypical phenotypes, defining the impact of intragenic copy number variations, or analyzing variants in regulatory regions—hypothesis-driven RNA-seq analysis confirmed molecular diagnoses in 45% of participants, provided supportive evidence for another 21%, and excluded candidate variants in 24% of cases [20].

Table 1: Diagnostic Utility of RNA-seq in Rare Diseases

| Study / Application | Cohort Size | Diagnostic Yield | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baylor Genetics Clinical Series | 3,594 cases | 50% variant reclassification | Provided functional evidence for variant interpretation [19] |

| SickKids Hypothesis-Driven RNA-seq | 33 probands | 45% diagnosis confirmation | Resolved impact of splice, CNV, and regulatory variants [20] |

| Undiagnosed Diseases Network | 45 patients | 24% positive diagnosis (11/45 cases) | Identified pathogenic mechanisms missed by DNA methods [19] |

| Mendelian Disorder Validation | 130 samples | Established clinical benchmarks | Developed validated protocols for diagnostic RNA-seq [17] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Tissue Selection and Sample Preparation

The selection of appropriate tissues is critical for successful diagnostic RNA-seq. Clinically accessible tissues (CATs) include fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), and whole blood. For rare disease diagnosis, studies indicate that fibroblasts express approximately 72.2% of genes in disease panels, followed by whole blood (69.4%), PBMCs (69.4%), and LCLs (64.3%) [21]. For neurodevelopmental disorders specifically, PBMCs express nearly 80% of genes associated with intellectual disability and epilepsy panels [21].

Sample Processing Protocol:

- Cell Culture: For fibroblasts, culture in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin [17]

- RNA Extraction: Use RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) with on-column genomic DNA removal from approximately 10^7 cells [17]

- RNA Quality Control: Assess integrity using Qubit 4 fluorometer with RNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher) and TapeStation RNA ScreenTape (Agilent) [20]

- NMD Inhibition: For detecting transcripts subject to nonsense-mediated decay, treat cells with cycloheximide (CHX) at 100μg/mL for 4-6 hours before RNA extraction [21]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Stranded mRNA library preparation is recommended for protein-coding transcript analysis:

- Library Prep: Illumina Stranded mRNA prep kit for fibroblasts and LCLs; Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus for whole blood to remove globin RNA and rRNA [17]

- Spike-in Controls: Include SIRV Set 3 (Lexogen) diluted 1:1000, using 3.3μL per 100ng input RNA for normalization [20]

- Sequencing: Illumina NovaSeqX platform with paired-end 150bp reads, targeting 150 million reads per sample for clinical diagnostics [17]

Bioinformatics Analysis

The bioinformatics pipeline for rare disease diagnosis focuses on outlier detection:

- Alignment: STAR v.2.7.8a in two-pass mode against GRCh38 reference genome [20]

- Quantification: RSEM v.1.3.3 for gene and isoform expression levels in TPM [20]

- Splicing Analysis: Junctions with ≥5 uniquely mapped reads analyzed for aberrant usage; Z-score ≥3 relative to GTEx controls considered significant [20]

- Expression Outliers: Genes with absolute Z-score >2 relative to GTEx cohort flagged for further investigation [20]

Figure 1: Clinical RNA-seq workflow for rare disease diagnosis, integrating DNA and RNA findings for comprehensive variant interpretation.

RNA-Seq in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

Biomarker Classes and Clinical Applications

RNA-seq has revolutionized cancer biomarker discovery by enabling comprehensive profiling of diverse RNA species with clinical utility:

Table 2: RNA Biomarker Classes in Cancer Research and Diagnostics

| Biomarker Class | Detection Method | Clinical Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Signatures | 3' mRNA-Seq, Whole Transcriptome | Cancer subtyping, prognosis, treatment prediction | PAM50 for breast cancer, Oncotype DX [18] [22] |

| Gene Fusions | Whole Transcriptome, Targeted RNA-Seq | Diagnosis, therapeutic targeting | EML4-ALK in lung cancer [18] |

| Non-coding RNAs (miRNA, circRNA, lncRNA) | Small RNA-Seq, Total RNA-Seq | Early detection, monitoring treatment response | miRNA profiles for cancer classification [22] |

| Immunotherapy Response Signatures | 3' mRNA-Seq with ML | Predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors | OncoPrism for HNSCC [18] |

| Single-Cell Signatures | scRNA-seq | Tumor heterogeneity, microenvironment, drug resistance | Cellular states in tumor ecosystems [23] |

Advanced Methodologies in Cancer Transcriptomics

Multi-omics Integration for Biomarker Discovery

Integrative analysis combining RNA-seq with genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data has significantly enhanced biomarker discovery. Multi-omics strategies enable the identification of biomarker panels at single-molecule, multi-molecule, and cross-omics levels, supporting cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic decision-making [24]. Landmark projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Pan-Cancer Atlas and the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) have demonstrated that proteomics can identify functional subtypes and reveal druggable vulnerabilities missed by genomics alone [24].

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies have transformed our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment dynamics:

scRNA-seq Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Tissue dissociation using enzymatic and mechanical methods optimized for cell type

- Cell Capture: Droplet-based systems (10× Genomics Chromium) for high-throughput profiling; FACS for larger cells (>30μm)

- Library Preparation: Single-cell 3' or 5' gene expression with cell barcoding and UMIs

- Sequencing: Illumina platforms with sufficient depth (≥50,000 reads/cell)

- Bioinformatic Analysis: SEURAT or Galaxy Europe Single Cell Lab for quality control, clustering, and differential expression [23]

Spatial transcriptomics extends this by preserving morphological context, enabling correlation of gene expression patterns with tissue architecture—particularly valuable for understanding tumor-immune interactions and heterogeneous therapy responses [24].

AI-Powered Biomarker Discovery

Machine learning and deep learning algorithms are increasingly integrated with RNA-seq analysis for biomarker discovery:

- Feature Selection: LASSO, network analysis, and feature importance scores for identifying minimal gene panels [25]

- Classification: Random Forest, XGBoost, and multilayer perceptron algorithms for cancer subtype classification [22]

- Predictive Modeling: Support vector machines and neural networks trained on circulating RNA data to distinguish benign from malignant disease [22]

For example, in breast cancer research, a machine learning pipeline identified eight-gene biomarker panels that achieved F1 Macro scores ≥80% across cell line and patient datasets, with thirteen genes (including MFSD2A, ERBB2, and ESR1) showing significant predictive capability for five-year survival [25].

Figure 2: Comprehensive cancer biomarker discovery workflow integrating multiple RNA-seq approaches with multi-omics and artificial intelligence.

Quality Control and Benchmarking

Technical Validation and Reproducibility

Large-scale benchmarking studies have revealed significant inter-laboratory variations in RNA-seq results, particularly when detecting subtle differential expression with clinical relevance. A comprehensive study across 45 laboratories using Quartet and MAQC reference materials found that experimental factors (including mRNA enrichment and library strandedness) and bioinformatics pipelines introduced substantial variability [26]. Key quality metrics include:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Based on principal component analysis, with Quartet samples showing average SNR of 19.8 compared to 33.0 for MAQC samples [26]

- Expression Correlation: Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.876 with Quartet TaqMan datasets and 0.825 with MAQC TaqMan datasets for protein-coding genes [26]

- ERCC Spike-in Controls: High correlation (0.964 average) with nominal concentrations across laboratories [26]

Best Practices for Clinical RNA-seq

To ensure reproducible and clinically actionable results:

Experimental Design:

- Implement batch effect controls through randomization

- Include reference materials like Quartet and MAQC samples

- Use spike-in controls (ERCC, SIRV) for normalization

Bioinformatics Quality Control:

Validation:

- Correlate RNA-seq findings with qPCR for candidate biomarkers

- Establish laboratory-specific reference ranges for expression and splicing

- Implement 3-1-1 reproducibility testing framework (triplicate preparations across multiple runs) [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Applications

| Category | Product/Platform | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality RNA from multiple sources | Includes gDNA removal column [17] |

| Blood Collection | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes (BD) | RNA stabilization in whole blood | Maintains RNA integrity for transport [20] |

| Library Prep (mRNA) | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | Protein-coding transcript analysis | Strand-specificity, 3' bias quantification [17] |

| Library Prep (Total RNA) | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus | Comprehensive RNA profiling | Ribosomal RNA depletion, includes ncRNAs [17] |

| 3' mRNA-Seq | QuantSeq FWD (Lexogen) | Targeted gene expression profiling | 3' bias, cost-effective for large cohorts [18] |

| Single-Cell Platform | 10× Genomics Chromium | Single-cell transcriptomics | High-throughput, cell barcoding [23] |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher) | Technical normalization | 92 synthetic RNAs at known concentrations [26] |

| Spike-in Controls | SIRV Set 3 (Lexogen) | Quality control and normalization | Synthetic RNA variants for pipeline validation [20] |

| Automation System | NGS Workstation (Agilent) | High-throughput processing | Automated library preparation [20] |

RNA sequencing has established itself as an indispensable technology bridging the gap between genetic information and functional biology in both rare disease diagnosis and cancer research. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide—from carefully designed RNA-seq protocols in clinically accessible tissues to advanced multi-omics integration and AI-powered analysis—provide a roadmap for researchers and clinicians implementing these approaches. As standardization improves through reference materials and benchmarking studies, and as computational methods continue to advance, RNA-seq is poised to become increasingly central to precision medicine initiatives, enabling more accurate diagnoses, novel biomarker discovery, and personalized treatment strategies across the disease spectrum.

In the field of genomics, accurately measuring gene expression is fundamental to understanding biological systems, from basic cellular functions to complex disease mechanisms. The correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR data serves as a critical benchmark for validating transcriptomic findings, making it essential to understand the different quantification metrics used by these technologies. RNA-Seq provides a comprehensive, high-throughput snapshot of the transcriptome, while qPCR offers a highly sensitive and specific method for validating the expression of a smaller set of genes [3] [27]. The accuracy of this correlation depends heavily on selecting appropriate normalization methods for each technology and understanding how their respective units—TPM and FPKM for RNA-Seq, and Cq values for qPCR—relate to one another. Misapplication of normalization strategies can lead to technical artifacts and incorrect biological interpretations, undermining the validity of research conclusions [28] [29]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these core quantification units, their calculation, appropriate use cases, and their role in ensuring rigor and reproducibility in gene expression studies, particularly within the context of RNA-Seq and qPCR correlation studies.

Core Quantification Units in RNA-Seq

RNA-Seq quantification requires normalization to account for two primary technical variables: sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample) and gene length (the number of bases in a transcript). Without this normalization, comparing expression levels between genes within a sample or for the same gene across different samples is invalid.

FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads)

FPKM is a within-sample normalization measure designed for paired-end sequencing experiments. It quantifies the expression of a gene by considering the number of fragments originating from it, normalized for the gene's length and the total sequencing depth [28] [30].

Calculation: The formula for FPKM is:

FPKM = (Number of fragments mapped to the gene / (Gene length in kilobases × Total number of million mapped fragments))

Key Characteristics: FPKM is calculated for each gene independently. The sum of all FPKM values in a sample is not constant, which makes it difficult to directly compare the proportional expression of a gene across different samples [30] [31].

TPM (Transcripts Per Million)

TPM is often considered a successor to FPKM and addresses one of its key limitations. The calculation involves a different order of operations: normalization for gene length is performed first, followed by normalization for sequencing depth [30].

Calculation:

- Divide the read count for a gene by its length in kilobases, giving Reads Per Kilobase (RPK).

- Sum all RPK values in the sample and divide by 1,000,000 to get a "per million" scaling factor.

- Divide each RPK value by this scaling factor to obtain TPM.

Key Characteristics: Because of the calculation method, the sum of all TPM values in a sample is always one million. This allows researchers to directly compare the proportion of transcripts for a specific gene across different samples [30] [32]. For example, a TPM of 3.33 in two different samples indicates that the same proportion of the total transcript pool was mapped to that gene in both samples.

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Metric | Full Name | Normalization For | Sum Across Sample | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped fragments | Gene length & sequencing depth | Variable | Comparing expression of different genes within a single sample. Not ideal for cross-sample comparison [31]. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Gene length & sequencing depth | Constant (1 million) | Comparing expression levels both within a single sample and across different samples [28] [30]. |

Figure 1: Workflow comparison for calculating TPM and FPKM from raw RNA-Seq read counts. The order of normalization steps is the fundamental difference between the two methods.

Considerations for Cross-Sample Comparison

While TPM is generally preferred for cross-sample comparison, some studies have suggested that normalized counts (e.g., using methods like DESeq2's median-of-ratios or TMM) may provide better reproducibility for specific downstream analyses like differential expression. One study on patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models found that normalized count data had a lower coefficient of variation and higher intraclass correlation across replicate samples compared to TPM and FPKM [28]. This highlights that the choice of quantification measure should be informed by the specific analytical goal.

The qPCR Quantification Cycle (Cq)

In contrast to RNA-Seq, quantitative PCR (qPCR) quantifies gene expression by measuring the amplification of a target sequence in real-time during the PCR reaction. The core quantification unit in qPCR is the Cq value (Quantification Cycle), also known as the Ct (Cycle Threshold) value.

- Definition: The Cq value is the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence signal from the amplification of a target gene crosses a predetermined threshold, indicating a statistically significant increase in amplification product [27].

- Interpretation: The Cq value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target transcript. A lower Cq value indicates a higher initial amount of the target mRNA, while a higher Cq value indicates a lower initial amount. Differences in Cq values (ΔCq) between genes or between samples are used for further normalization and calculation of relative expression.

Normalization of qPCR Data

Normalization is critical to eliminate technical variation introduced during RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and sample loading. The most common strategy is the use of reference genes (RGs), which are genes with stable expression across all samples in the study [29] [6].

- The 2^–ΔΔCq Method: This widely used method calculates the relative fold change in gene expression between an experimental group and a control group. It involves normalizing the Cq of the target gene to a reference gene (ΔCq), then normalizing this value to the control group (ΔΔCq).

- Limitations and Advanced Methods: The 2^–ΔΔCq method can be sensitive to variations in amplification efficiency. Recent guidelines recommend using more robust statistical approaches like Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), which can enhance statistical power and account for variability in amplification efficiency [27].

- Alternative: Global Mean (GM) Normalization: When profiling tens to hundreds of genes, an alternative method is to normalize to the global mean (GM)—the average Cq of all well-performing genes in the assay. A 2025 study on canine gastrointestinal tissues found that GM normalization outperformed the use of multiple reference genes in reducing intra-group variation, particularly when more than 55 genes were profiled [29].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq and qPCR Analysis

| Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit | For cDNA synthesis and amplification from low-input RNA, used in full-length scRNA-seq protocols [9] [33]. |

| mirVana RNA Isolation Kit | For total RNA extraction, including from platelets [9]. | |

| RNAlater | A storage reagent that stabilizes and protects RNA in intact tissues and cells [9]. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | HISAT2, STAR | Read alignment tools for mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome [3] [9]. |

| Salmon, Kallisto | Pseudoalignment tools for fast transcript quantification, bypassing the need for full alignment [3] [28]. | |

| GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) | Software to identify optimal reference and validation candidate genes from RNA-seq (TPM) data for qPCR validation [6]. | |

| GeNorm, NormFinder | Algorithms to evaluate the stability of potential reference genes using qPCR Cq data [29] [6]. |

Correlating RNA-Seq and qPCR Data

Correlation studies between RNA-Seq and qPCR are essential for validating transcriptomic results. A well-designed benchmarking study using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data demonstrated that while various RNA-seq workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) show high gene expression and fold-change correlations with qPCR, a small but specific set of genes can show inconsistent results [3].

Experimental Protocol for Correlation Studies

A robust protocol for correlating RNA-Seq and qPCR data involves the following key steps, adapted from benchmark studies [3] [9] [6]:

- Sample Preparation: Use the same RNA sample for both RNA-Seq and qPCR assays. Ensure RNA quality and integrity are high (e.g., RIN ≥ 6) [9].

- RNA-Seq Processing:

- Library Preparation: Use a standardized kit (e.g., Illumina). For challenging samples like platelets, consider ultra-low input protocols.

- Sequencing & Quantification: Sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq/NovaSeq). Process reads through a workflow (e.g., alignment with STAR/Hisat2 or pseudoalignment with Salmon/Kallisto) to obtain gene-level TPM values [3] [9].

- qPCR Assay Design:

- Candidate Gene Selection: Select genes for validation that cover a range of expression levels and fold-changes. Software like GSV can identify stable reference genes and highly variable target genes from the RNA-seq TPM data [6].

- Assay Validation: Ensure qPCR assays have high and similar amplification efficiencies. Use intron-spanning probes/primers to avoid genomic DNA amplification [27] [9].

- qPCR Experiment & Analysis:

- Data Alignment & Correlation:

- Unit Conversion: For a fair comparison, align the transcripts detected by each technology. Convert RNA-seq TPM values to log2(TPM). Convert qPCR data to normalized relative quantities or log2(fold-change) [3].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate Pearson correlation (R²) for expression levels and for fold-changes between conditions. Identify and investigate outliers.

Figure 2: An integrated experimental workflow for correlating RNA-Seq and qPCR data to validate gene expression findings.

Key Findings and Pitfalls

Benchmarking studies have revealed critical insights for correlation studies:

- High Overall Concordance: Most workflows show high gene expression correlations (e.g., R² > 0.8) and fold-change correlations (e.g., R² > 0.9) with qPCR data [3].

- Existence of Problematic Genes: Each quantification method reveals a small, specific set of genes with inconsistent expression measurements between RNA-Seq and qPCR. These genes are often characterized by shorter length, fewer exons, and lower expression levels [3].

- Systematic Discrepancies: A significant proportion of these inconsistent genes are reproducibly identified across different datasets and workflows, pointing to systematic technological discrepancies rather than algorithmic errors [3].

- Recommendation: Researchers should be aware that a specific set of genes may not validate well by qPCR regardless of the RNA-seq workflow used. Careful validation is warranted for this gene set [3].

The accurate interpretation of transcriptome data hinges on a thorough understanding of its underlying quantification units. TPM has become the preferred normalized unit for RNA-Seq due to its suitability for cross-sample comparisons, while FPKM remains relevant for within-sample gene expression analysis. In qPCR, the Cq value is the fundamental measurement that requires rigorous normalization, ideally using validated reference genes or the global mean method. When correlating data from these two powerful technologies, researchers must follow rigorous experimental and computational protocols, from sample preparation through data alignment. Acknowledging that certain gene characteristics can lead to inconsistent quantification between platforms is crucial for ensuring the rigor and reproducibility of gene expression studies in research and drug development. By applying these principles and best practices, scientists can more reliably decode phenotypic information from transcriptomic data.

From Sample to Data: Best Practices in RNA-Seq and qPCR Workflow Design

The advancement of genomic medicine has increasingly relied on accessing informative biological tissues through minimally invasive means. For research involving human subjects, particularly in clinical trials and longitudinal studies, the impracticality of repeatedly sampling solid tissues has driven the adoption of peripheral blood as a primary biosource. Within this liquid biopsy field, two key components have emerged as powerful platforms for transcriptomic analysis: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) and blood platelets. This whitepaper examines the scientific rationale, methodological considerations, and technical applications of these two biosources, contextualizing their use within the framework of RNA-Seq and qPCR correlation studies.

The critical advantage of both PBMCs and platelets lies in their accessibility through standard venipuncture, eliminating the need for invasive tissue biopsies. PBMCs represent a heterogeneous mixture of immune cells—including T cells, B cells, NK cells, and monocytes—that serve as sentinels for systemic immune responses and certain disease states. Platelets, while anucleate, possess a dynamic transcriptome inherited from megakaryocytes and further modified through interactions with their environment. Together, these biosources enable researchers to probe physiological and pathological processes through gene expression analysis while minimizing participant burden.

PBMCs: A Window into the Immune Transcriptome

Biological Rationale and Composition

PBMCs constitute a critical interface between the circulatory system and overall immune status. Their composition includes multiple cell types with distinct transcriptional profiles that respond to various stimuli, making them particularly valuable for studying immune-related conditions, infectious diseases, and inflammatory disorders. Recent evidence indicates that up to 80% of genes in intellectual disability and epilepsy panels are expressed in PBMCs, highlighting their utility even for neurodevelopmental disorders [34]. Comparative studies of clinically accessible tissues (CATs) have demonstrated that PBMCs express 69.4% of genes across various disease panels, performing nearly as well as fibroblasts (72.2%) and better than lymphoblastoid cell lines (64.3%) for larger gene panels [34].

Technical Considerations and Protocols

Optimal PBMC processing requires careful attention to pre-analytical variables. Research indicates that processing delays of under 24 hours have minimal impact on PBMC quality and downstream assay outcomes, though viability decreases significantly after 48 hours [35]. For RNA-seq applications, short-term cultured PBMCs with and without cycloheximide treatment enable detection of transcripts subject to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), significantly enhancing variant detection capability [34].

The following table summarizes key technical aspects of PBMC processing for transcriptomic studies:

Table 1: PBMC Processing and Analytical Considerations

| Parameter | Specification | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum processing delay | <24 hours recommended | Delays >24h increase granulocyte contamination and reduce viability [35] |

| Cell viability requirement | >90% recommended for scRNA-seq | Low viability increases background noise and affects cluster resolution [36] |

| NMD inhibition | Cycloheximide treatment | Enables detection of unstable transcripts with premature termination codons [34] |

| Expression correlation between CATs | 50.5%-70.4% of genes expressed across all CATs | Facilitates comparison across studies using different biosources [34] |

| Stimulation capability | Pathogen exposure (e.g., C. albicans, M. tuberculosis) | Reveals context-specific gene expression responses and eQTLs [37] |

Applications in Disease Research

PBMCs have demonstrated particular utility in immunogenetics and infectious disease research. Single-cell RNA-sequencing of PBMCs from 120 individuals exposed to three different pathogens revealed widespread, context-specific gene expression regulation, with myeloid cells (monocytes and DCs) showing the highest number of differentially expressed genes upon stimulation [37]. This context-specificity is crucial for understanding how genetic variants influence gene expression in response to environmental triggers, potentially explaining disease susceptibility mechanisms.

Platelet RNA: The Anucleate Transcriptome Reservoir

Biological Foundations

Despite being anucleate, platelets contain a diverse repertoire of RNA species inherited from megakaryocytes, including mRNAs, lncRNAs, miRNAs, tRNAs, and circRNAs [38]. Throughout their 7-10 day lifespan, platelets dynamically regulate their RNA content and can translate RNAs into proteins in response to external cues. Recent groundbreaking research has revealed that platelets also sequester extracellular DNA, including tumor-derived genetic material, suggesting a previously unrecognized biological function in nucleic acid clearance [39].

Platelets have demonstrated an impressive capacity to internalize nucleic acids from their environment, including glioma-derived EGFRvIII RNA transcripts and EML4-ALK rearrangements in non-small-cell lung cancer [38]. This "tumor-educated" platelet phenomenon forms the basis for their use in liquid biopsy applications for cancer diagnostics and monitoring.

Methodological Advances in Platelet Isolation

Traditional platelet isolation methods based on multiple centrifugation steps pose significant challenges due to platelet activation and granule content release during physical stress [40]. Plateletpheresis has emerged as a superior alternative, yielding highly concentrated, pure platelet samples without leukocyte contamination. This method enables the collection of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) with concentrations exceeding 500×10⁹ platelets/L and negligible other cell types [40].

The following table outlines key methodological considerations for platelet RNA analysis:

Table 2: Platelet Isolation and RNA Analysis Methods

| Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Plateletpheresis | High purity, no activation, suitable for single-donor studies [40] | Requires specialized equipment and training [40] |

| Multiple centrifugation | Widely accessible, no special equipment needed | Causes platelet activation and granule release [40] |

| ThromboSeq | Shallow RNA-sequencing detects hundreds of mRNA transcripts [38] | Requires specialized bioinformatic pipelines |

| qPCR for mutant detection | Highly sensitive for specific tumor-derived transcripts (e.g., EGFRvIII) [38] | Limited to known mutations |

| Flow cytometry for subpopulations | Identifies platelet subsets (e.g., DRAQ5hi vs DRAQ5lo) [39] | Requires immediate processing |

Diagnostic and Monitoring Applications

Platelet RNA has shown remarkable utility in neuro-oncology, where traditional liquid biopsy approaches have faced challenges due to the blood-brain barrier. In glioblastoma patients, platelet RNA profiles change following tumor resection and during treatment, potentially distinguishing tumor pseudoprogression from true progression [38]. Similar applications have been demonstrated for non-small-cell lung cancer (EML4-ALK rearrangements) and prostate cancer (PCA3 transcripts) [38].

The mechanism behind these diagnostic capabilities involves active uptake of circulating nucleic acids. Experimental evidence confirms that platelets rapidly capture DNA from nucleated cells, with uptake plateauing at approximately 6 minutes in vitro [39]. This DNA is contained within membrane-bound vesicles inside platelets, not within granules or mitochondria [39].

Correlation Between RNA-Seq and qPCR: Validation Frameworks

Benchmarking Studies and Technical Validation

The correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR data represents a critical validation step for transcriptomic studies using both PBMCs and platelets. Comprehensive benchmarking studies using the well-characterized MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples have demonstrated high expression correlations between RNA-seq and qPCR across multiple processing workflows [3]. Pearson correlation values ranged from R² = 0.798 to 0.845 depending on the computational pipeline used [3].

When comparing gene expression fold changes between samples, correlations between RNA-seq and qPCR were even stronger, with R² values ranging from 0.927 to 0.934 [3]. These findings support the use of RNA-seq as a quantitative tool for transcriptome analysis while highlighting the importance of validation approaches for specific gene sets.

Method-Specific Discrepancies and Solutions

Despite generally high correlations, certain gene sets show inconsistent expression measurements between technologies. Studies have identified a small but specific set of genes with inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR data, characterized by being smaller, having fewer exons, and lower expression levels compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [3]. These method-specific inconsistencies are reproducible across independent datasets, suggesting they represent systematic technological differences rather than random noise.

For HLA gene expression analysis, which presents particular challenges due to extreme polymorphism, comparisons between qPCR and RNA-seq have shown moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) for HLA-A, -B, and -C genes [8]. This highlights the need for careful validation when using RNA-seq for highly polymorphic genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PBMC and Platelet Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation Media | HISTOPAQUE-1077, Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for PBMC isolation from whole blood [36] |

| Cell Culture Media | RPMI 1640 with GlutaMAX, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Maintenance and short-term culture of PBMCs [36] |

| Immune Stimulants | Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), Pam3CSK4 | Activate immune cells to study response pathways [41] [36] |

| NMD Inhibitors | Cycloheximide (CHX), Puromycin (PUR) | Block nonsense-mediated decay to detect unstable transcripts [34] |

| Platelet Isolation Systems | Trima Accel system (Terumo BCT) | Automated plateletpheresis for high-purity platelet collection [40] |

| RNA Stabilization | TRIzol, RLT buffer with β-mercaptoethanol | Preserve RNA integrity during sample processing [40] |

| Single-Cell Reagents | 10X Genomics Chromium Next GEM | Single-cell RNA-sequencing library preparation [36] |

| DNA Staining Dyes | DRAQ5, NUCLEAR-ID Red, Hoechst | Identify DNA-containing platelets by flow cytometry [39] |

PBMCs and platelets represent complementary biosources for minimally invasive transcriptomic studies, each with distinct advantages and applications. PBMCs offer a comprehensive window into the immune system's transcriptional landscape, while platelets provide unique insights into systemic processes, particularly in oncology. The strong correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR data for both biosources supports their use in clinical research and diagnostic development.

Future directions will likely focus on standardizing protocols across laboratories, establishing quality control metrics specific to each biosource, and developing integrated analysis approaches that combine information from both PBMCs and platelets. As single-cell technologies continue to advance, the resolution at which we can probe these biosources will further improve, unlocking new opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel biomarkers. For clinical trial design, the minimally invasive nature of both PBMC and platelet collection enables more frequent sampling and longitudinal monitoring, providing dynamic insights into treatment response and disease progression.

The accuracy of alignment and quantification methods for bulk RNA-seq data processing has a profound impact on downstream analysis, such as differential expression analysis, functional annotation, and pathway analysis [42]. Inaccurate alignment or quantification can lead to false positives or false negatives, resulting in incorrect biological conclusions [42]. Within the complex RNA-seq pipeline, the step of mapping sequencing reads to a reference transcriptome or genome stands as a critical determinant of data quality and reliability. This process essentially involves deciding where each of the millions of short RNA sequences (reads) originated from in the reference, which directly influences all subsequent biological interpretations.

Two fundamentally different computational approaches have emerged for this task: traditional alignment (also called mapping) and modern pseudoalignment. Alignment tools like STAR aim to find the exact base-by-base position of a read within a reference genome or transcriptome, while pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto use a lightweight algorithm to determine the compatibility of reads with transcripts without performing exact alignment [42]. The choice between these approaches represents a crucial decision point for researchers designing their analysis pipelines, particularly in studies where validation with quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a gold standard.

This technical guide examines both alignment and pseudoalignment methodologies within the context of RNA-seq and qPCR correlation studies, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the evidence needed to select appropriate tools for their specific research objectives.

Fundamental Concepts: Alignment vs. Pseudoalignment

Traditional Alignment-Based Methods

Traditional alignment-based tools represent the established approach for mapping RNA-seq reads. These tools employ sophisticated algorithms to find the exact genomic origin of each sequencing read, providing base-level resolution.

Core Mechanism: Alignment tools like STAR map RNA-seq reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using an alignment algorithm that accounts for splice junctions and other genomic features [42]. They perform exhaustive search to identify the optimal genomic position for each read, considering factors like sequence similarity, splice sites, and indels.

Output: The primary output of traditional aligners is a sequence alignment map (SAM) or binary alignment map (BAM) file that contains the precise genomic coordinates for each read [43]. These files can be subsequently processed to generate read counts for each gene, which serve as the basis for expression quantification.

Strengths: Alignment methods provide comprehensive genomic context, enabling the discovery of novel splice junctions, fusion genes, and sequence variants [42]. The base-by-base alignment facilitates detailed inspection of mapping quality and supports various downstream analyses beyond mere quantification.

Modern Pseudoalignment Approaches

Pseudoalignment represents a paradigm shift in read mapping, focusing computational resources specifically on the task of expression quantification rather than comprehensive genomic localization.

Core Mechanism: Pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto use a lightweight algorithm to determine the abundance of transcripts by assessing read compatibility with reference transcripts without performing base-by-base alignment [42] [43]. These tools employ k-mer based indexing and efficient data structures to rapidly determine which transcripts a read could potentially originate from, based on k-mer matches.

Output: Pseudoaligners directly generate transcript abundance estimates in the form of counts or TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values, bypassing the intermediate BAM file generation [42] [43]. This streamlined output accelerates the transition from raw reads to expression values.

Strengths: The primary advantages of pseudoalignment include significantly faster processing speeds and reduced memory requirements [42] [43]. By avoiding the computationally intensive task of base-level alignment, these tools can process large datasets in a fraction of the time required by traditional aligners while maintaining high quantification accuracy.

Conceptual Workflow Comparison

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences between these two approaches in a typical RNA-seq analysis pipeline:

Performance Comparison: Speed, Accuracy, and Resource Requirements

Computational Efficiency and Resource Usage

Multiple benchmarking studies have demonstrated significant differences in computational requirements between alignment and pseudoalignment approaches:

Processing Speed: Kallisto's pseudoalignment approach provides substantially faster processing compared to alignment-based methods. In practical applications, Kallisto completes quantification tasks in a fraction of the time required by STAR, making it particularly advantageous for large-scale studies with numerous samples [42].

Memory Utilization: Pseudoaligners typically demonstrate superior memory efficiency. For instance, Kallisto operates with minimal memory requirements compared to the significant RAM needed for STAR's genome indexing and alignment processes [42]. This memory frugality enables analysis of large datasets on standard computational hardware.

Scalability: The efficient computational profile of pseudoalignment tools makes them highly scalable for studies involving hundreds of samples. Traditional aligners face linear increases in processing time with dataset size, while pseudoaligners maintain more consistent performance characteristics across varying sample sizes.

Recent advancements continue to push these efficiency boundaries. The development of alevin-fry-atac introduces a modified pseudoalignment scheme that partitions references into "virtual colors," achieving 2.8 times faster processing while using only 33% of the memory required by the second fastest approach, Chromap [44].

Quantitative Accuracy and Correlation with qPCR

A critical consideration in tool selection is quantification accuracy, particularly in relation to established validation methods like quantitative PCR. A comprehensive benchmark evaluating 192 analysis pipelines applied to 18 samples from two human cell lines provides insightful data [5].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification Methods

| Tool | Method Type | Processing Speed | Memory Efficiency | qPCR Correlation | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [42] | Alignment-based | Moderate to Slow | Lower | High [5] | Novel splice junction detection, fusion genes, variant calling |

| Kallisto [42] | Pseudoalignment | Very Fast | High | High [5] | Rapid transcript quantification, large-scale studies, low-resource environments |

| BWA [43] | Alignment-based | Slow | Moderate | Benchmark data not available in search results | DNA-seq, variant discovery |

| Bowtie2 [43] | Alignment-based | Moderate | Moderate | High in some tested pipelines [5] | General-purpose alignment, splice-aware mapping with appropriate parameters |

The systematic assessment revealed that both alignment-based and pseudoalignment-based pipelines can achieve high correlation with qPCR validation data when combined with appropriate counting methods [5]. Specifically, pipelines utilizing Kallisto for pseudoalignment demonstrated strong correlation with qPCR measurements, confirming that the quantification accuracy of modern lightweight approaches is comparable to more computationally intensive methods [5].

Experimental Design Considerations for qPCR Correlation Studies

Impact of Experimental Parameters on Tool Performance

The optimal choice between alignment and pseudoalignment approaches depends significantly on specific experimental design parameters and data characteristics:

Transcriptome Completeness: Kallisto's pseudoalignment approach performs optimally when the transcriptome is well-annotated and complete [42]. In contrast, if the transcriptome is incomplete or contains numerous novel splice junctions, STAR's traditional alignment approach may be more suitable for comprehensive transcript discovery [42].

Read Length and Quality: Kallisto demonstrates robust performance with standard short-read lengths (75-150 bp), while STAR may show advantages with longer read lengths that facilitate more accurate splice junction identification [42]. Data quality also influences tool performance, with complex libraries potentially benefiting from STAR's more detailed alignment approach.

Sequencing Depth: Kallisto's pseudoalignment approach is less sensitive to sequencing depth variations compared to STAR's alignment-based method [42]. This characteristic makes pseudoalignment particularly suitable for studies with variable sequencing depths across samples or those with limited sequencing resources.

Reference Quality: The completeness and accuracy of the reference genome or transcriptome significantly impact both approaches. Alignment methods can partially compensate for reference limitations by identifying novel features, while pseudoaligners depend more heavily on comprehensive reference annotations.

Validation Strategies for qPCR Correlation

Establishing robust correlation between RNA-seq quantification and qPCR measurements requires careful experimental design:

Housekeeping Gene Selection: A benchmark study selected 32 genes for qPCR validation based on stable expression across 32 healthy tissues and two cell lines, including 10 genes with the highest and lowest median coefficient of variation, plus 10 random mid-range genes, and two commonly used housekeeping genes (GAPDH and ACTB) [5]. This systematic approach ensures representative validation across the dynamic range of expression.

Normalization Methods: The same study evaluated three normalization approaches for qPCR data: endogenous control normalization (using GAPDH and ACTB), global median normalization, and the most stable gene method [5]. Researchers detected treatment-induced bias in traditional housekeeping genes (GAPDH and ACTB) and ultimately selected global median normalization for its robustness in capturing Ct value distribution [5].

Statistical Correlation Assessment: Correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements should be assessed using multiple statistical measures, including Pearson correlation for linear relationships and non-parametric measures for precision and accuracy assessment across the full expression range [5].

Technical Protocols and Implementation

Recommended Experimental Workflow for Method Validation

For researchers conducting RNA-seq studies with planned qPCR validation, the following integrated workflow ensures robust correlation:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of RNA-seq studies with qPCR validation requires specific laboratory reagents and computational resources:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq/qPCR Studies

| Category | Specific Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | RNeasy Plus Mini Kit [5] | High-quality RNA isolation with genomic DNA removal | Critical for obtaining intact RNA suitable for both sequencing and qPCR |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq Stranded RNA Library Prep Kit [5] | Construction of strand-specific RNA-seq libraries | Maintains strand information for accurate transcript assignment |

| qPCR Assays | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [5] | Specific target amplification and detection | Provides standardized, highly specific quantification for validation genes |

| cDNA Synthesis | SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System [5] | Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA | Uses oligo(dT) priming for consistent mRNA representation |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes [45] | Technical controls for normalization and quality assessment | Enables assessment of technical performance across platforms |