Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Improving RNA-Seq and qPCR Correlation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to enhance the correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR data, a critical step for validating transcriptomic findings.

Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Improving RNA-Seq and qPCR Correlation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to enhance the correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR data, a critical step for validating transcriptomic findings. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we explore the sources of technical variation in both platforms and present robust methodologies for experimental design and data analysis. The guide details troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls and establishes a rigorous validation framework incorporating reference materials and orthogonal testing. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to improve the accuracy, reproducibility, and reliability of gene expression studies, thereby strengthening downstream biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Divide: Why RNA-Seq and qPCR Data Diverge

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does the choice of RNA-Seq library preparation method impact the detection of different RNA species? The library preparation method directly determines which RNA molecules are converted into sequencer-readable DNA, introducing variation based on your target RNA [1].

- Poly-A Selection: Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by targeting the poly-A tail. It is ideal for studying protein-coding genes but will miss non-polyadenylated RNA (e.g., some non-coding RNAs) and is not suitable for degraded RNA samples [2] [1].

- rRNA Depletion: Removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes over 95% of total RNA. This enriches for both coding and non-coding RNA species, including pre-mRNA and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), making it the preferred method for degraded samples like FFPE tissues [2] [1] [3].

- Size Selection: Used for sequencing small RNA species, such as microRNA (miRNA), by isolating RNAs of a specific size range [1].

Q2: What are the key considerations for preparing libraries from low-quality or challenging sample types? Sample-specific protocols are required to manage technical variation from challenging inputs [3].

- FFPE or Degraded RNA: Use a random-primed library preparation kit (not oligo(dT)-primed) in conjunction with rRNA depletion. The random priming does not require intact RNA 3' ends, which are often missing in degraded samples [3].

- Blood Samples: These contain high levels of globin mRNA, which can dominate sequencing reads. It is recommended to use both rRNA and globin depletion protocols to improve the detection of low-expression transcripts [2].

- Ultra-Low Input or Single-Cells: Use specialized kits employing template-switching oligonucleotides for full-length cDNA amplification. For high-quality, low-input RNA, oligo(dT) priming is effective, while degraded, low-input RNA requires random priming and rRNA depletion [3].

Q3: My RNA-Seq and qPCR results show a moderate correlation for highly polymorphic genes like HLA. Is this expected? Yes, this is a recognized challenge. A 2023 study observed only a moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between qPCR and RNA-Seq expression estimates for HLA class I genes [4]. This discrepancy arises because standard RNA-Seq alignment tools struggle with the extreme polymorphism and sequence similarity among HLA paralogs. To minimize this variation, employ HLA-tailored bioinformatic pipelines that account for known HLA diversity during the alignment step, rather than relying on a single reference genome [4].

Q4: How do different bioinformatic workflows affect gene expression quantification, and which one is most accurate? A 2017 benchmarking study compared five popular workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data [5]. The table below summarizes their performance in correlating gene expression fold changes with qPCR, a key metric for most studies.

Table 1: Performance of RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows Against qPCR Fold Change Data [5]

| Workflow | Type | Fold Change Correlation (R²) with qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Tophat-HTSeq | Alignment-based | 0.934 |

| STAR-HTSeq | Alignment-based | 0.933 |

| Kallisto | Pseudoalignment | 0.930 |

| Salmon | Pseudoalignment | 0.929 |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | Alignment-based | 0.927 |

The study concluded that all tested workflows showed high concordance with qPCR data for most genes. However, each workflow identified a small, specific set of genes with inconsistent expression measurements. These genes were typically lower expressed and had fewer exons, suggesting careful validation is warranted for such cases [5].

Q5: When should I use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in my RNA-Seq experiment? UMIs are short random barcodes added to each original cDNA molecule before PCR amplification. They correct for two main technical biases [2]:

- PCR Amplification Bias: UMIs allow bioinformatic tools to count original molecules, eliminating over-representation of molecules that amplified more efficiently.

- PCR Errors: Copies of the same original molecule can be grouped and errors corrected. UMIs are highly recommended for deep sequencing projects (>50 million reads/sample) and low-input library preparations where PCR duplication rates are high [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Correlation with qPCR Validation Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Library Prep and RNA Input Mismatch

- Cause: Using an oligo(dT)-based kit on degraded RNA (RIN < 6) results in 3'-end bias and loss of full-length transcript information [1] [3].

- Solution: For low-quality RNA (e.g., from FFPE), switch to a random-primed library prep kit with rRNA depletion [3]. Always check RNA quality with an Agilent Bioanalyzer before library construction [1].

Bioinformatic Workflow Selection

- Cause: Standard alignment-based workflows can misassign reads from highly similar or polymorphic gene families (e.g., HLA, immunoglobulins), leading to inaccurate quantification [4].

- Solution: For polymorphic genes, use specialized tools (e.g., HLA-tailored pipelines) that incorporate population variation into the alignment process [4]. For standard gene expression, refer to established workflows in Table 1.

Gene-Specific Effects

- Cause: A benchmarking study found that each RNA-Seq workflow has a small set of genes for which it produces inconsistent results compared to qPCR. These genes are often smaller, have fewer exons, and are lower expressed [5].

- Solution: If your research focuses on a specific gene set, validate your RNA-Seq findings for those genes with an orthogonal method like qPCR.

Issue: High Background from Ribosomal or Globin RNA

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient depletion of abundant RNA species during library prep.

- Solution:

- For standard total RNA-seq: Ensure the rRNA depletion kit is compatible with your sample type (e.g., mammalian, bacterial) and that the procedure is optimized for your RNA input amount [3].

- For blood samples: Explicitly request or perform globin mRNA depletion in addition to rRNA depletion. This is a critical step for transcriptome profiling from blood [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for RNA-Seq

| Item | Function | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enable sequencing of other RNA species. | Essential for non-polyadenylated RNA (e.g., bacterial RNA, lncRNA) and degraded samples [2] [1]. |

| Globin Depletion Kits | Specifically removes globin mRNA from blood samples. | Dramatically improves detection of other transcripts in blood-derived RNA [2]. |

| UMI Adapters | Uniquely tags each original cDNA molecule to correct for PCR duplicates and errors. | Critical for high-depth sequencing and low-input experiments to achieve accurate quantification [2]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | A set of synthetic RNA controls of known concentration added to the sample. | Used to assess the sensitivity, dynamic range, and technical performance of the entire RNA-Seq workflow [2]. |

| Strand-Specific Prep Kits | Preserves the original orientation (strand) of the RNA transcript during cDNA synthesis. | Vital for accurately determining which DNA strand is transcribed, crucial for identifying antisense transcripts and simplifying genome annotation [1]. |

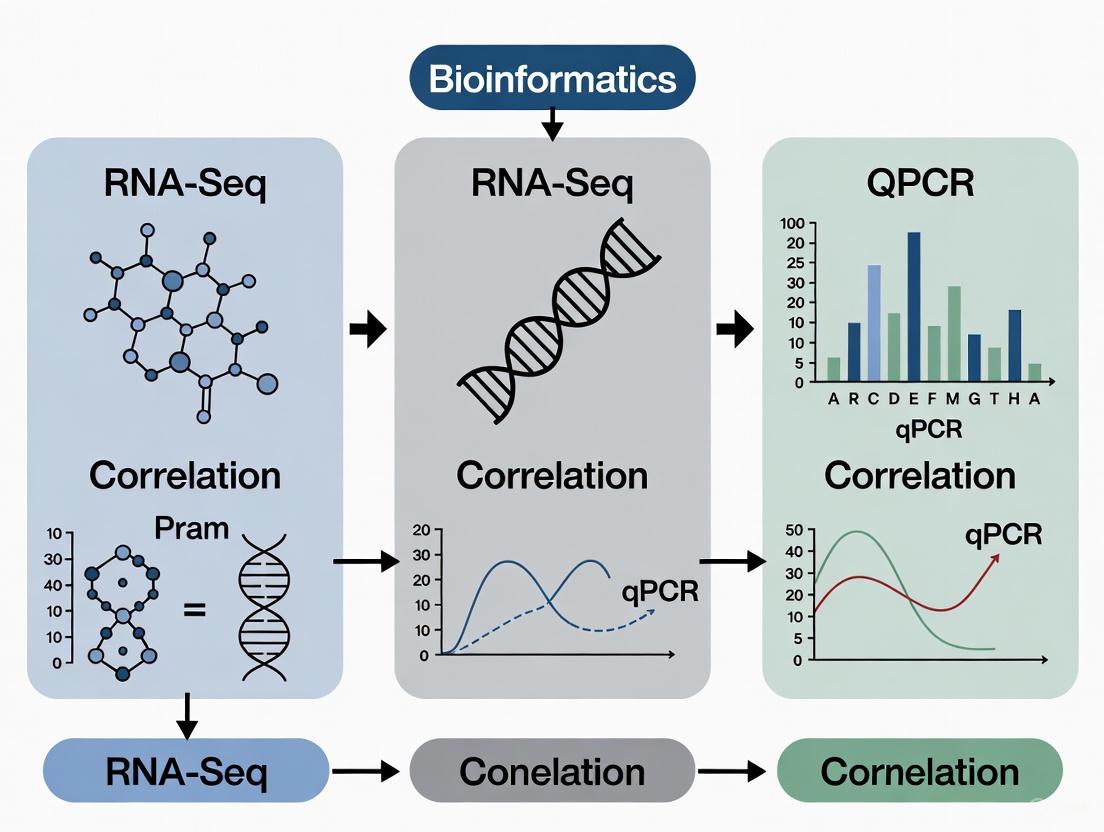

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in a standard RNA-Seq workflow that directly influence technical variation and correlation with qPCR.

RNA-Seq Workflow and Key Variation Sources

Troubleshooting Poor qPCR Correlation

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) serves as a cornerstone technology in molecular biology, providing the sensitive and specific quantification of nucleic acids essential for robust gene expression analysis. In RNA-Seq correlation studies, the accuracy of qPCR data is paramount for validating transcriptomic findings. This technical support center addresses the most common experimental challenges researchers face, providing targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies to ensure the generation of reliable, reproducible data that strengthens the bridge between sequencing discovery and quantitative validation.

Core Principles and Workflow

qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, combines the amplification of target DNA sequences with the simultaneous quantification of the amplified products. Unlike traditional PCR that uses end-point detection, qPCR monitors the accumulation of PCR products in real-time during the exponential phase of amplification, which provides the most precise and accurate data for quantitation [6]. In gene expression analysis, this typically involves an initial step of reverse transcribing RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) before the qPCR amplification, in a process known as RT-qPCR [6].

The process is characterized by the Ct (threshold cycle) value, which is the PCR cycle number at which the sample's fluorescent signal crosses a predefined threshold, indicating a detectable level of amplified product. A lower Ct value corresponds to a higher starting concentration of the target sequence [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common problems encountered during qPCR experiments, their potential causes, and evidence-based solutions to ensure data integrity.

No or Low Amplification

Problem: Little to no detectable signal or much lower yield than expected.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor RNA Quality | Use high-quality, intact RNA. Check integrity via gel electrophoresis and A260/280 ratio. Treat fresh tissue with RNA stabilization reagents [7]. |

| Enzyme/Inhibition | Use a high-quality master mix as recommended. Purify the template to remove inhibitors; do not use more than 10% of a reverse transcription reaction volume for qPCR [8]. |

| Suboptimal Primers | Use dedicated software for design. Check for primer-dimer formation and ensure primers are present in excess at equal concentrations [8]. |

| Insufficient Template | Repurify the template and increase the amount. For genomic DNA, use 1 ng–1 µg per 50 µL reaction [8] [9]. |

| Suboptimal Cycling | Ensure complete initial denaturation (95°C for 1-3 min). For GC-rich templates, prolong the denaturation step in 5 sec increments [8]. |

Non-Specific Amplification or Primer Dimers

Problem: Multiple peaks in the melt curve or multiple bands on a gel, indicating amplification of unintended targets.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Annealing Temperature Too Low | Increase the annealing temperature. It should be 5°C lower than the lowest primer Tm, but must be determined empirically [8] [10]. |

| Poor Primer Design | Use software to avoid self-complementarity and dimers. Avoid GC-rich 3' ends. Test several primer pairs to select the best one [9] [11]. |

| Excess Primer | Titrate primer concentration, typically between 0.1-1 µM. Too high a concentration increases miss-priming [8] [12]. |

| Room Temperature Setup | Assemble all PCR reactions on ice to prevent non-specific priming before thermal cycling begins [8]. |

Irreproducible Results

Problem: High variability between technical replicates or between experimental runs.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Pipetting Errors | Mix all reagents thoroughly before use. Use a master mix to minimize sample-to-sample variation [8] [7]. |

| Low-Quality Reagents | Use high-quality, nuclease-free water and master mixes. Use dedicated pipettes and high-quality, low DNA-binding tubes [8]. |

| Component Changes | Carefully monitor and document any changes in reagents, plastics, or instruments, as these can significantly impact results [8]. |

| Inconsistent Thermal Cycling | Check the calibration of the heating block. Ensure the instrument is properly maintained [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do I design high-quality qPCR primers? Effective primer design is critical for assay specificity and efficiency. Follow this workflow for optimal results [10] [11]:

- Amplicon Length: Keep between 70-200 base pairs for efficient amplification [11].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Aim for 60-63°C for both forward and reverse primers, with a difference of ≤3°C between them [11] [12].

- GC Content: Maintain 40-60% for product stability [11].

- 3' End: Ensure the 3' end terminates in a G or C residue to promote strong binding [11].

- Specificity: Design primers to span an exon-exon junction where possible to avoid amplification of genomic DNA [7] [11].

- Validation: Always check primers for self-complementarity and dimer formation using design software [10].

2. What is an acceptable amplification efficiency for my qPCR assay? The ideal amplification efficiency for a qPCR assay is between 90% and 110% [7] [13]. Efficiency (E) is calculated from the slope of the standard curve using the formula: E = (10^(-1/slope) - 1). A slope of -3.32 corresponds to 100% efficiency, meaning the product doubles perfectly every cycle. Slopes between -3.6 and -3.1 are generally acceptable [13]. Assays with efficiency outside this range should be re-optimized, as they can lead to inaccurate quantification in relative expression studies.

3. How should I select and validate reference genes for normalization? Normalization with stable reference genes (endogenous controls) is essential to correct for sample-to-sample variations in RNA input, quality, and reverse transcription efficiency [6] [7].

- Challenge: Traditionally used "housekeeping" genes like β-actin (ACTB) or GAPDH can be variable under certain experimental conditions, leading to misinterpretation of results [14].

- Solution: Select and validate reference genes that are stable in your specific experimental system. This is often done using RNA-seq data to identify genes with low variability or by using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder to test a panel of candidate genes [14]. For studies on decidualization, for example, STAU1 was identified as a more stable reference gene than β-actin [14].

- Best Practice: Always use more than one validated reference gene for reliable normalization.

4. What are the key considerations for avoiding contamination in qPCR? Contamination can lead to false positives and irreproducible data. Key practices include:

- Physical Separation: Use separate, clean areas for RNA/DNA extraction, reaction setup, and post-amplification analysis [8].

- Meticulous Technique: Always wear gloves and use sterile, aerosol-resistant pipette tips. Routinely decontaminate surfaces with DNA-degrading solutions or 70% ethanol [8] [7].

- Enzymatic Control: Use Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG/UNG) in combination with dUTP in the master mix to prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR products [8].

- Essential Controls: Always include a No-Template Control (NTC) to check for reagent contamination and a No-Reverse-Transcription Control (No-RT) to detect genomic DNA contamination in RT-qPCR assays [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA | Template for cDNA synthesis. | Integrity is critical; use fresh tissue or RNA stabilizers. Check RNA quality via electrophoresis or bioanalyzer [7]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA template. | Choose based on one-step vs. two-step RT-qPCR protocol [6]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzymatically amplifies the target DNA. | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by being inactive at room temperature [12]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides optimized buffer, salts, dNTPs, and polymerase. | Includes fluorescent dyes (SYBR Green) or is compatible with probe-based chemistries. Using a master mix improves reproducibility [8] [7]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Defines the target region for amplification. | Must be well-designed for specificity and efficiency. Predesigned assays can save time and optimization effort [7] [10]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Used for normalization of gene expression data. | Must be empirically validated for stability under specific experimental conditions [6] [14]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for reactions and dilutions. | Essential for preventing degradation of RNA and reaction components [8]. |

FAQs: mRNA Enrichment

Q1: What is the core difference between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion, and how does the choice impact my data?

Poly(A) enrichment uses oligo(dT) magnetic beads to selectively capture RNA molecules with polyadenylated tails, which are typically mature messenger RNAs (mRNAs). This method is highly cost-effective but is restricted to eukaryotic organisms and requires high-quality RNA (RIN > 8). It will miss non-polyadenylated transcripts, including many non-coding RNAs and bacterial mRNAs [15].

In contrast, rRNA depletion uses species-specific probes to hybridize and remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA). This method is suitable for both eukaryotes and prokaryotes and is preferred for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE), as it does not introduce 3' bias. However, it requires prior knowledge of the rRNA sequences for probe design [16] [15]. The choice profoundly affects your data: poly(A) enrichment focuses your sequencing on protein-coding genes, while rRNA depletion provides a broader view of the transcriptome, including non-coding RNAs [17] [15].

Q2: My mRNA enrichment efficiency is low. How can I improve it?

Low efficiency, often evidenced by high residual rRNA content, is a common challenge. Recent research indicates that following a single round of enrichment under standard conditions may be insufficient, leaving roughly 50% of the RNA content as rRNA [18]. To significantly improve efficiency, consider these strategies:

- Increase the Beads-to-RNA Ratio: For oligo(dT)-based enrichment, increasing the ratio of magnetic beads to input RNA from a standard 13.3:1 to 50:1 can reduce rRNA content to about 20% [18].

- Perform Two Rounds of Enrichment: Implementing a second, consecutive round of poly(A) selection dramatically reduces rRNA content to below 10% [18].

- Combine Methods for Dual RNA-seq: For studies involving plant-bacterial or host-pathogen interactions, a sequential strategy is highly effective. First, perform poly(A) selection to capture eukaryotic host mRNA. Then, subject the flow-through to rRNA depletion to enrich for bacterial mRNA. This enriched method has been shown to increase mapping efficiency to the bacterial genome and identify more differentially expressed genes [16].

Q3: How does RNA input quantity affect library preparation and downstream analysis?

The input RNA quantity is a pivotal parameter that influences library complexity, bias, and the ability to detect true biological signals.

- Standard vs. Low Input: At standard input levels (e.g., 100-1000 ng), most commercial kits perform robustly for identifying differentially expressed genes. However, with low-input or degraded samples, protocol performance diverges significantly. Protocols designed for low input (e.g., SMARTer Ultra Low) often rely on cDNA amplification, which can introduce duplication artifacts and bias, particularly against transcripts with high GC content [17].

- Impact on Data Quality: A large-scale multi-center study found that factors related to sample input and processing, including mRNA enrichment, are primary sources of inter-laboratory variation in RNA-seq data. This variation becomes critically important when trying to detect subtle differential expression between similar sample groups, a common scenario in clinical diagnostics [19].

- Best Practice: Always use a kit validated for your specific input range and quality. For low-input studies, kits employing template-switching mechanisms may be preferable, though be aware of potential 3' bias [17].

FAQs: Strandedness

Q1: Why should I use a stranded RNA-seq protocol?

A stranded (or strand-specific) protocol preserves the information about which original DNA strand the RNA was transcribed from. This is crucial for:

- Identifying Antisense Transcription: Accurately detecting transcripts that overlap the opposite strand of a gene.

- Resolving Overlapping Genes: Precisely quantifying expression from genes that reside on opposite strands in overlapping genomic regions.

- Improving Gene Annotation: Correctly defining gene boundaries and discovering novel genes and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [17].

Non-stranded protocols can assign a transcript to the wrong strand, leading to misinterpretation of expression data.

Q2: My stranded library data shows high "reverse" strand mapping. Is this a problem?

Not necessarily. A key feature of a properly functioning stranded library is that the majority of reads from a protein-coding gene should map to the opposite strand of the gene's genomic coordinates. This is because the sequencing read is generated from the cDNA, which is complementary to the original RNA transcript. You should confirm your data analysis pipeline correctly interprets the strandedness information embedded in the library structure (e.g., the read orientation). Consult your library prep kit manual and aligner documentation for the correct strandedness parameters (e.g., "fr-firststrand" in TopHat2 for Illumina TruSeq stranded kits).

FAQs: Input RNA

Q1: How does RNA quality impact my choice of mRNA enrichment method?

RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a critical determinant for method selection.

- High-Quality RNA (RIN > 8): Both poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion are viable. Poly(A) enrichment is a cost-effective choice if the goal is to study protein-coding mRNA [15].

- Degraded RNA (RIN < 7): rRNA depletion is the strongly recommended method. Poly(A) enrichment of degraded RNA will result in a severe 3' bias, as the 5' ends of transcripts are lost, and the oligo(dT) primers will only capture the remaining 3' fragments. This bias skews gene expression quantification and prevents full-length transcript analysis [15].

Q2: I have a limited amount of a precious sample. What are the key considerations for low-input RNA-seq?

Working with low-input RNA requires careful planning to balance data quality with sample conservation.

- Kit Selection: Use kits specifically designed for low input. These often incorporate whole-transcript amplification steps, but be aware that they can differ in performance. Some kits may recover better transcriptome complexity, while others may have more effective rRNA depletion or perform better with high-GC transcripts [17].

- Amplification Bias: A major challenge is amplification bias, where certain transcripts are over- or under-represented during the PCR steps. This can reduce the dynamic range and accuracy of quantification.

- Verify with qPCR: For key findings from a low-input RNA-seq experiment, plan to validate the expression levels of a subset of genes using an independent method like qPCR. This confirms that the observed expression changes are not technical artifacts of the low-input workflow [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting RNA-Seq Preparation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low library yield | Poor input RNA quality, contaminants inhibiting enzymes, inaccurate quantification [21]. | Re-purify input RNA; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV absorbance; verify RNA integrity [21]. |

| High rRNA background | Inefficient mRNA enrichment [18]. | Optimize beads-to-RNA ratio; perform two consecutive rounds of poly(A) enrichment [18]. |

| High duplicate read rate | Over-amplification during library PCR due to low starting input [21]. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; increase starting RNA input if possible. |

| Adapter contamination | Inefficient ligation or cleanup; overly aggressive fragmentation [21]. | Titrate adapter-to-insert ratio; optimize fragmentation parameters; perform rigorous size selection. |

| 3' bias in coverage | Use of poly(A) selection on degraded RNA [15]. | Switch to an rRNA depletion protocol for degraded samples [15]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting qPCR for RNA-Seq Validation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent results among biological replicates | RNA degradation or minimal starting material [22]. | Check RNA concentration/quality (260/280 ratio ~1.9-2.0); repeat RNA isolation with a more suitable method [22]. |

| Amplification in No Template Control (NTC) | Contamination or primer-dimer formation [22]. | Clean workspace and pipettes; prepare fresh primer dilutions; include a dissociation curve to detect primer-dimer [22]. |

| Poor reaction efficiency (low R²) | PCR inhibitors or pipetting error [22]. | Dilute template to dilute inhibitors; practice proficient pipetting and prepare standard curves fresh [22]. |

| Unexpected Ct values | Incorrect thermal cycling protocol or genomic DNA contamination [22]. | Verify instrument protocol; DNase treat RNA samples prior to reverse transcription [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: An Improved mRNA Enrichment Strategy for Dual RNA-Seq of Plant-Bacterial Interactions

This protocol sequentially removes plant mRNA and bacterial rRNA to enrich for bacterial mRNA from infected samples [16].

- Poly(A) Selection for Plant mRNA: Begin with total RNA extracted from bacteria-infected plant tissue. Use oligo(dT) magnetic beads to capture and remove polyadenylated plant mRNA.

- rRNA Depletion for Bacterial mRNA: Take the supernatant from step 1, which is enriched in bacterial RNA, and subject it to probe-based rRNA depletion (e.g., using Ribo-Zero kit) to remove bacterial 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA.

- Library Construction: Proceed with a standard strand-specific RNA-seq library preparation protocol on the enriched bacterial mRNA.

- Efficiency Assessment: Evaluate the success of enrichment by a increased mapping rate of sequencing reads to the bacterial genome and coding sequences (CDS) compared to a non-enriched protocol [16].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Poly(A) Enrichment Efficiency for Yeast RNA

This protocol demonstrates how to optimize a standard poly(A) enrichment protocol to drastically reduce rRNA contamination [18].

- Input: Use high-quality total RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

- First Round of Enrichment: Perform a first round of poly(A) selection using Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads. A beads-to-RNA ratio of 13.3:1 is sufficient for this step.

- Second Round of Enrichment: Elute the RNA from the first round and immediately subject the entire yield to a second round of poly(A) selection. For this round, use a high beads-to-RNA ratio (e.g., 90:1).

- Quality Control: Assess the final rRNA content using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation). This two-round method can reduce rRNA content to less than 10% [18].

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: mRNA Enrichment Method Selection

This diagram outlines the decision-making process for choosing between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion.

Diagram 2: Stranded Library Construction Logic

This diagram illustrates the key steps and molecular logic in constructing a stranded RNA-seq library.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads | For poly(A) enrichment of eukaryotic mRNA. Binding to polyA tails allows separation from rRNA [18]. | Efficiency can be optimized by increasing beads-to-RNA ratio or performing two rounds of selection [18]. |

| Ribo-Zero / RiboMinus Kits | For probe-based rRNA depletion. Uses DNA or LNA probes to hybridize and remove rRNA from total RNA [16] [18]. | Effective for prokaryotes and degraded samples. Coverage of 5S rRNA varies by kit [16]. |

| Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN) | For enzymatic normalization. Degrades abundant, double-stranded cDNAs (from rRNA/housekeeping genes) post-synthesis [15]. | Normalizes transcript levels but can compromise accurate quantification of highly expressed genes [15]. |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | A widely used commercial kit for poly(A)-selected, strand-specific library prep [17]. | Considered universally applicable for protein-coding gene profiles; tends to capture genes with higher expression and GC content [17]. |

| SMARTer Ultra Low RNA Kit | For library prep from low-input RNA. Uses template-switching mechanism for cDNA synthesis and amplification [17]. | A good choice for low input, though may be inferior to standard kits in rRNA removal and exonic mapping rates [17]. |

Core Concepts and Reference Materials

What are the Quartet and MAQC reference materials and why are they important for benchmarking?

The MAQC (MicroArray/Sequencing Quality Control) and Quartet reference materials are well-characterized RNA samples used to assess the performance and reproducibility of transcriptomic technologies like RNA-Seq and qPCR.

- MAQC Reference Samples: Developed by the SEQC/MAQC Consortium, these include RNA from ten cancer cell lines (MAQC A) and human brain tissues from 23 donors (MAQC B). They represent samples with "significantly large biological differences" [19].

- Quartet Reference Samples: Introduced by the Quartet project, these are derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family (parents and monozygotic twin daughters). These samples have "small inter-sample biological differences," reflecting the subtle differential expression often seen in clinical diagnostics [19].

These materials are critical because they provide various types of "ground truth" for benchmarking, including reference datasets, built-in truths like ERCC spike-in ratios, and known mixing ratios for specific samples [19].

How do these materials help improve correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR?

Using these standardized reference materials allows researchers to systematically identify technical variations and optimize workflows. A benchmarking study using MAQC samples revealed that when comparing gene expression fold changes between MAQC A and B samples, approximately 85% of genes showed consistent results between RNA-Seq and qPCR data [5]. This provides a quantitative measure of how well RNA-Seq data correlates with the established qPCR "gold standard," highlighting areas for improvement in experimental protocols and data analysis.

Experimental Design and Benchmarking Protocols

What is a recommended protocol for conducting a benchmarking study?

A comprehensive benchmarking study should evaluate multiple aspects of performance across different laboratory conditions and analysis workflows. The Quartet project's design provides an excellent template [19]:

Sample Preparation:

- Include both Quartet (D5, D6, F7, M8) and MAQC (A, B) reference materials in your study design.

- Utilize defined mixture samples (e.g., T1 and T2 with 3:1 and 1:3 ratios of M8 and D6) as built-in controls.

- Spike with ERCC RNA controls at appropriate concentrations.

Experimental Execution:

- Process samples across multiple laboratories or technical replicates to assess inter-laboratory variation.

- Employ diverse library preparation protocols (e.g., varying mRNA enrichment methods, strandedness).

- Use different sequencing platforms to evaluate technology-specific effects.

Data Analysis:

- Apply multiple bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., alignment tools, quantification methods, normalization approaches).

- Compare results against reference datasets and TaqMan qPCR data.

- Use ERCC spike-in ratios and known mixture ratios for validation.

Table 1: Key Reference Materials for Transcriptomics Benchmarking

| Material Type | Composition | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAQC A | RNA from 10 cancer cell lines | Large biological differences | Assessing major differential expression |

| MAQC B | RNA from human brain tissues of 23 donors | Large biological differences | Assessing major differential expression |

| Quartet Samples | B-lymphoblastoid cells from family quartet | Subtle biological differences | Clinical diagnostic refinement, detecting small expression changes |

| ERCC Spike-Ins | 92 synthetic RNA sequences | Known concentrations | Normalization, sensitivity assessment |

What performance metrics should be evaluated in a benchmarking study?

A robust benchmarking framework should assess multiple performance dimensions [19] [23]:

Data Quality Metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Based on principal component analysis to distinguish biological signals from technical noise.

- Library Complexity: Assessment of unique versus duplicated sequences.

Expression Accuracy Metrics:

- Pearson Correlation: Between RNA-Seq estimates and qPCR measurements or reference datasets.

- Absolute Expression Concordance: Comparison with TaqMan datasets for protein-coding genes.

Differential Expression Performance:

- Fold Change Correlation: Between RNA-Seq and qPCR for sample comparisons.

- Concordance in DEG Identification: Percentage of genes consistently identified as differentially expressed by both methods.

Sensitivity and Specificity:

- Limit of Detection: Lowest expression level reliably quantified.

- False Discovery Rates: For differential expression calls.

Figure 1: Workflow for conducting a comprehensive benchmarking study of transcriptomic methods.

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

The Quartet project identified several key factors contributing to inter-laboratory variation in RNA-Seq data [19]:

Experimental Factors:

- mRNA enrichment method: Different enrichment protocols significantly impact results.

- Library strandedness: Stranded versus non-stranded protocols affect gene quantification.

- Batch effects: Sequencing samples across different flow cells or lanes introduces variability.

Bioinformatics Factors:

- Gene annotation sources: Different references affect gene counts.

- Alignment tools: Various algorithms perform differently.

- Quantification methods: Normalization approaches significantly impact results.

Recommendations:

- Standardize mRNA enrichment and library preparation protocols across replicates.

- Use consistent bioinformatics pipelines with appropriate normalization.

- Implement batch correction methods when samples are processed separately.

Why might RNA-Seq and qPCR results disagree, and how can this be resolved?

Discrepancies between RNA-Seq and qPCR can arise from multiple sources:

Technical Factors:

- RNA-Seq mapping biases: Fragment distribution within transcripts is not uniform, requiring bias correction [24].

- qPCR amplification efficiency: Variations in PCR efficiency between assays affect quantification accuracy [25].

- Low-abundance genes: Both technologies show higher variability for lowly expressed genes [5].

Bioinformatic Factors:

- Incorrect transcript alignment: Misalignment can lead to inaccurate read counts.

- Poor normalization: Inadequate normalization methods fail to correct for technical variations.

Resolution Strategies:

- Apply bias correction algorithms to RNA-Seq data to address fragment distribution issues [24].

- Validate qPCR assays for efficiency (90-110%) and specificity [23].

- Focus on genes with moderate to high expression levels for correlation studies.

- Use standardized analysis pipelines that have been benchmarked against reference materials.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common RNA-Seq and qPCR Discrepancies

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor correlation between platforms | Different sensitivity to low-abundance transcripts | Filter out low-expression genes (<0.1 TPM); focus on robustly detected genes [5] |

| Systematic bias in RNA-Seq data | Non-uniform fragment distribution in library prep | Apply bias correction algorithms (e.g., Cufflinks) [24] |

| High inter-laboratory variation | Different mRNA enrichment methods or library prep protocols | Standardize experimental protocols; use consistent bioinformatics pipelines [19] |

| Inconsistent differential expression calls | Different statistical thresholds or normalization methods | Use reference materials to establish method-specific thresholds; validate with qPCR [5] |

How can I improve the accuracy of my RNA-Seq expression estimates?

Bias Correction:

- Implement likelihood-based approaches that simultaneously estimate bias parameters and expression levels [24].

- Account for both positional bias (fragments preferentially located toward transcript ends) and sequence-specific bias (sequence surrounding fragment starts/ends affects selection).

- Use tools like Cufflinks that incorporate bias correction, which has been shown to improve correlation with qPCR data from R²=0.753 to 0.807 in MAQC samples [24].

Pipeline Selection:

- Consider alignment-based (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks) or pseudoalignment (e.g., Kallisto, Salmon) methods, which show similar overall performance but may differ for specific gene sets [5].

- Evaluate your chosen pipeline against reference materials to understand its specific limitations.

Figure 2: Troubleshooting framework for identifying sources of discrepancy between RNA-Seq and qPCR data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Transcriptomics Benchmarking

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/References |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Materials | Provide ground truth for benchmarking | Quartet reference materials, MAQC A/B samples [19] |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations | ERCC Spike-In Mix [19] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation | DNase I treatment for genomic DNA removal [26] |

| Library Preparation Kits | cDNA library construction for sequencing | Various commercial kits with different mRNA enrichment [19] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis for qPCR | SuperScript kits, Luna WarmStart Reverse Transcriptase [27] [25] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Quantitative PCR amplification | SYBR Green or TaqMan master mixes [23] [25] |

| Bias Correction Software | Improve RNA-Seq expression estimates | Cufflinks with bias correction [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Which reference material is more appropriate for my study - Quartet or MAQC?

Choose MAQC reference materials when:

- Evaluating large differential expression (e.g., cancer vs. normal tissue).

- Establishing baseline performance for major expression differences.

- Conducting initial validation of new RNA-Seq workflows.

Choose Quartet reference materials when:

- Studying subtle expression differences (e.g., different disease subtypes or stages).

- Optimizing protocols for clinical diagnostic applications.

- Assessing sensitivity for detecting small expression changes [19].

What is the minimum number of replicates needed for reliable results?

For both RNA-Seq and qPCR experiments:

- Technical replicates: Minimum of 3 replicates to account for technical variability.

- Biological replicates: Multiple independent biological samples (number depends on expected effect size and variability).

- For qPCR specifically, "the necessary number of sample replicates (n) varies depending on the experimental system. When the experimental error is expected to be relatively large, use a larger number of samples" [26].

How can I properly normalize my qPCR data for accurate comparison with RNA-Seq?

- Use multiple housekeeping genes that show stable expression across your experimental conditions [26].

- Consider using geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes as implemented in algorithms like geNorm or BestKeeper [26].

- For absolute quantification, prepare calibration curves using serial dilutions of RNA.

- For relative quantification, use serial dilutions of cDNA and normalize to reference genes [26].

What are the best practices for avoiding genomic DNA amplification in qPCR?

- Design primers that span exon-exon junctions where possible.

- Treat RNA samples with DNase I to remove contaminating genomic DNA.

- Use kits with dedicated gDNA removal steps (e.g., PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser) [26].

- Include no-RT controls to detect genomic DNA contamination.

The Crucial Role of Bioinformatics Pipelines in Introducing Variation

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Correlation Between RNA-seq and qPCR Data

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution | Recommended Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR results | Differences in normalization techniques [28]. | Apply appropriate normalization for each technology (e.g., TMM for RNA-seq, geometric mean for qPCR) [28]. | edgeR (TMM), DESeq2 (geometric mean). |

| Technical artifacts in RNA-seq data for highly polymorphic genes (e.g., HLA) [4]. | Use HLA-tailored bioinformatics pipelines for alignment and quantification [4]. | Specialized pipelines (e.g., from Boegel et al., Lee et al.). | |

| Non-specific amplification in qPCR [29]. | Redesign primers using specialized software; optimize annealing temperature [29]. | Primer design software. | |

| Inconsistent pipetting leading to Ct value variations [29]. | Implement proper pipetting techniques; use automated liquid handling systems [29]. | Automated dispensers (e.g., I.DOT Liquid Handler). |

Experimental Protocol: Validating RNA-seq Findings with qPCR

- Gene Selection: Select differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from RNA-seq analysis.

- Primer Design: Design and validate qPCR primers for selected genes. Ensure amplicons are specific and intron-spanning where possible to distinguish from genomic DNA.

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize cDNA from the same RNA samples used for RNA-seq.

- qPCR Run: Perform qPCR reactions in technical and biological replicates.

- Data Normalization & Analysis: Normalize qPCR Ct values using stable reference genes (geometric mean of multiple genes is recommended). Calculate fold-change values and correlate with RNA-seq results.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Differential Gene Expression Analysis

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution | Recommended Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| High false positive/negative DGE results | Inadequate normalization for library size and composition [28]. | Apply normalization methods like TMM (edgeR) or geometric mean (DESeq2) to account for technical variation [28]. | edgeR, DESeq2. |

| Model assumption violations for RNA-seq count data distribution [28]. | Choose an appropriate statistical model (e.g., Negative Binomial for RNA-seq). For complex distributions, consider non-parametric methods [28]. | NOIseq (non-parametric), SAMseq. |

|

| Low statistical power due to small sample size [28]. | Ensure adequate biological replicates; use empirical Bayes methods in tools like edgeR or DESeq2 to stabilize estimates [28]. |

edgeR, DESeq2. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Pipeline Questions

What is the primary purpose of a bioinformatics pipeline for data visualization? The primary purpose is to process, analyze, and visualize biological data, transforming raw data into meaningful visual representations like graphs, charts, and heatmaps. This enables researchers to extract actionable insights, simplify complex data, and make informed decisions [30].

How can I ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of my bioinformatics pipeline? Focus on data quality during preprocessing, use reliable and standardized tools, automate processes to minimize human error, and maintain detailed documentation for every step. Utilizing workflow management systems like Nextflow or Snakemake also enhances reproducibility [30] [31].

RNA-seq Specific Questions

Why might my RNA-seq and qPCR results for the same gene disagree? Moderate correlation (e.g., 0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53 for HLA genes) is common due to technical and biological factors [4]. Key reasons include:

- Technical Biases: RNA-seq involves alignment and quantification steps that can be biased for extremely polymorphic genes, while qPCR is susceptible to primer efficiency and amplification issues [4] [29].

- Normalization Differences: RNA-seq data is normalized based on overall read distribution, whereas qPCR typically uses a small set of reference genes. These different approaches can yield different expression estimates [28].

- Dynamic Range: Both techniques have different effective dynamic ranges for detection.

What are the most common tools used for differential gene expression analysis from RNA-seq data?

edgeR and DESeq2 are among the most widely used tools for DGE analysis. They both use the Negative Binomial distribution to model count data but employ different normalization and statistical shrinkage strategies [28].

qPCR Specific Questions

How can I prevent non-specific amplification in my qPCR assays? Non-specific amplification is often due to primer-dimer formation or mis-priming. To address this, redesign your primers using specialized software to avoid secondary structures and dimers. If redesigning is not feasible, optimize the reaction conditions, especially the annealing temperature [29].

How can I reduce Ct value variations between my qPCR replicates? Ct variations are frequently caused by manual pipetting errors. Ensure consistent and proper pipetting techniques. For higher precision and reproducibility, consider using automated liquid handling systems, which significantly reduce this variability [29].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

RNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow

qPCR Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Extraction Kits | To obtain RNA with high integrity and purity, free from genomic DNA and inhibitors. | Essential for both RNA-seq and qPCR. Poor RNA quality is a major cause of low yield in both techniques [29]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | To synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates for downstream qPCR analysis. | Adjust cDNA synthesis conditions for optimal efficiency [29]. |

| Validated qPCR Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides designed to amplify the gene of interest. | Design using specialized software to have appropriate length, GC content, and melting temperature (Tm), while checking for potential secondary structures [29]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green) for real-time detection. | Ensures reaction consistency. Must be compatible with the qPCR instrument and detection chemistry. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | A system for high-precision, non-contact liquid dispensing. | Improves accuracy, reduces Ct value variations and contamination risk in qPCR workflows [29]. |

Robust Workflows: Methodologies to Synchronize RNA-Seq and qPCR

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between TPM and RPKM/FPKM, and why does it matter for cross-sample comparison?

TPM (Transcripts Per Million) and RPKM/FPKM (Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped) both normalize for sequencing depth and gene length, but the order of operations differs, leading to a critical practical distinction [32].

- RPKM/FPKM first normalizes for sequencing depth (per million) and then for gene length. The sum of all RPKM/FPKM values in a sample can vary, making direct comparison of expression proportions between samples difficult [32].

- TPM first normalizes for gene length (per kilobase) and then for sequencing depth. This ensures that the sum of all TPM values in each sample is the same (one million), allowing you to directly compare the proportion of transcripts a gene represents across different samples [32].

Q2: I use TPM values for my cross-sample comparisons. Why might my results still be unreliable when combining data from different sequencing protocols?

A common misconception is that TPM values, being "normalized," are always comparable across samples. However, TPM represents the relative abundance of a transcript within a specific population of sequenced RNAs [33]. If the composition of this RNA population changes—for example, due to different library preparation protocols—the TPM values for the same gene in the same biological sample will not be directly comparable [33] [34].

For instance, in a study of human blood samples:

- With poly(A)+ selection, the most abundant sequenced molecules were protein-coding mRNAs [33].

- With rRNA depletion, small RNAs (e.g., RN7SL2, RN7SL1) became the most abundant category [33]. This shift in the underlying RNA repertoire means a protein-coding gene's TPM value will appear artificially deflated in the rRNA-depleted sample because it now constitutes a smaller fraction of a different total transcript pool [33].

Q3: When should I avoid using TPM for differential expression analysis?

TPM is generally not recommended as direct input for differential expression (DE) analysis tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [34] [35]. These tools are designed to work with raw or normalized counts and incorporate their own sophisticated normalization methods (e.g., DESeq's median-of-ratios, edgeR's TMM) that are robust to composition bias and other technical artifacts [36] [34] [35]. TPM, RPKM, and FPKM are considered suitable for comparing expression levels within a single sample but tend to perform poorly for cross-sample DE analysis when transcript distributions differ significantly [34].

Q4: My TPM values show high variability between biological replicates. What could be the cause?

High variability between replicates can stem from several sources, many of which are not resolved by TPM normalization alone:

- Inherent biological variation: TPM does not control for biological variability.

- RNA composition bias: If a few genes are extremely highly expressed in one replicate, they can consume a large share of the sequencing reads, artificially depressing the counts for all other genes. TPM normalization does not fully correct for this [36].

- Batch effects: Technical variations from different library preparation dates, sequencing runs, or personnel can introduce systematic biases that TPM does not address [37].

- Pipeline choices: The algorithms used for read mapping and quantification can significantly impact the final gene expression estimates, leading to differences in TPM values even when starting from the same raw data [38].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Poor Correlation Between RNA-seq (TPM) and qPCR Results

Potential Cause 1: Improper quantification method for downstream analysis.

- Solution: Use normalized counts from established DE tools for validation against qPCR. A comprehensive study of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models found that normalized count data provided superior reproducibility between replicates (lower Coefficient of Variation and higher Intraclass Correlation Coefficient) compared to TPM and FPKM [34]. When performing DE analysis, use the normalized counts from tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, which are more robust for such comparisons [34].

Potential Cause 2: Joint impact of RNA-seq analysis pipeline components.

- Solution: Carefully select your entire analysis pipeline, as the combination of mapping, quantification, and normalization methods jointly affects accuracy. Research from the FDA-led SEQC project demonstrates that the choice of pipeline components significantly impacts the accuracy of gene expression estimation compared to qPCR [38]. The table below summarizes the performance of different pipeline components from this study.

Table 1: Impact of RNA-seq Pipeline Components on Gene Expression Estimation Accuracy (vs. qPCR) [38]

| Component | Option | Effect on Accuracy (Deviation from qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Normalization | Median Normalization | Lowest deviation (highest accuracy) for most genes [38]. |

| Other Methods (e.g., RPKM) | Showed larger deviations from qPCR benchmarks [38]. | |

| Mapping & Quantification | Bowtie2 (multi-hit) + Count-based | Showed the largest deviation from qPCR [38]. |

| Most other combinations | Performed well when combined with median normalization [38]. | |

| Gene Expression Level | Low-expression genes | All pipelines showed larger deviation than for all genes [38]. |

Issue: Inconsistent Results When Integrating Public RNA-seq Datasets

Potential Cause: Major differences in sample preparation protocols.

- Solution: Be highly cautious when merging datasets generated with different methods (e.g., poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion). If integration is necessary, apply batch effect correction methods after quantification. Tools like ComBat or Harmony can model and remove technical biases arising from different protocols [37]. The diagram below illustrates the workflow for robust cross-protocol data integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for Robust RNA-seq Normalization Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Considerations for Cross-Platform Comparability |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Control RNAs | Known quantities of exogenous transcripts added to the sample. | Serves as an internal standard to monitor technical variation and assess the accuracy of normalization across different protocols [36]. |

| Reference RNA Samples | Well-characterized, stable RNA pools (e.g., from MAQC/SEQC projects). | Provides a benchmark for evaluating the performance and reproducibility of different RNA-seq pipelines and normalization methods [38]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for other RNA species. | Yields a different transcript population than poly(A)+ selection; know that TPM values will not be directly comparable between these protocols [33]. |

| Poly(A)+ Selection Kits | Enriches for mRNAs with poly(A) tails. | The standard for mRNA sequencing; TPM values from different studies using this method are more comparable, though batch effects may remain [33]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Software | Computational tools (e.g., ComBat, limma, Harmony). | Crucial for integrating datasets from different batches or platforms after initial quantification to remove technical artifacts [37]. |

In Silico Selection of Optimal qPCR Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

Accurate gene expression analysis using quantitative PCR (qPCR) fundamentally relies on normalization using stably expressed reference genes. Traditional methods for identifying these genes require extensive laboratory validation, which is time-consuming and costly. The emergence of large-scale public RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) databases provides a powerful alternative, enabling researchers to identify optimal reference genes computationally, or in silico. This technical guide details robust methodologies for selecting reference genes from RNA-seq data, a critical step for improving the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR results and ensuring the reliability of gene expression data in research and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core principle behind in silico reference gene selection? The core principle leverages large RNA-seq datasets to computationally evaluate the expression stability of candidate genes across many biological conditions. By applying specific algorithms, researchers can identify genes with minimal expression variation, which are then recommended as optimal internal controls for qPCR experiments. This approach transforms the validation process from a wet-lab procedure into a bioinformatic analysis [39] [40].

FAQ 2: My RNA-seq and qPCR data show a moderate correlation for my gene of interest. Could poor reference gene choice be a factor? Yes, absolutely. While technical differences between the platforms exist, the use of inappropriate reference genes for qPCR normalization is a major contributor to observed discrepancies. Selecting a reference gene that is unstable under your specific experimental conditions can introduce significant bias, leading to inaccurate relative quantification and poor correlation with RNA-seq data. Validating your reference genes is a critical step in reconciling data from these two techniques [4].

FAQ 3: I have access to a large RNA-seq dataset. What are the main methodological approaches for in silico selection? Two primary and powerful approaches are widely used, both relying on the analysis of RNA-seq data (typically in TPM or FPKM units) from a cohort of samples representing your experimental conditions:

- The iRGvalid Method: This method uses a double-normalization strategy. A target gene's expression is first normalized against the total gene expression in each sample, and then again against a candidate reference gene. The stability of the candidate gene is assessed by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient (Rt) between the pre- and post-normalized target gene expression across all samples. A higher Rt value indicates a more stable reference gene. This can be done for individual genes or combinations of genes [39].

- The Gene Combination Method: This approach posits that a combination of genes, even if individually unstable, can balance each other out to create a highly stable composite reference. The method involves selecting a pool of genes with expression levels similar to your target gene and then testing all possible combinations of a fixed number (k) of these genes. The optimal combination is the one that shows the lowest variance in its arithmetic mean expression across the dataset while maintaining a geometric mean expression level suitable for normalization [40].

FAQ 4: What are the key advantages of using an in silico approach?

- Robustness: Utilizes large sample sizes, providing greater statistical power than most lab-based validation studies [39].

- Efficiency: Saves significant time and laboratory resources by prioritizing the best candidate genes before any experimental validation [39].

- Universality: Helps identify reference genes with stable expression across diverse conditions, improving the reproducibility and comparability of studies [39].

- Combinatorial Optimization: Allows for the identification of optimal multi-gene reference panels that outperform single genes [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Correlation Between RNA-seq and qPCR Data After In Silico Selection

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The RNA-seq dataset used for in silico selection does not adequately represent the specific experimental conditions of your qPCR study.

- Solution: Ensure the RNA-seq cohort closely mirrors your study's biological conditions (e.g., same tissue type, disease state, or treatment).

- Cause: The candidate gene's expression level is too low or too high compared to your target gene, leading to normalization issues.

- Solution: When applying the gene combination method, pre-filter your candidate gene pool to include only genes with similar expression levels to your target gene [40].

- Cause: PCR inhibition or suboptimal qPCR assay efficiency is skewing results.

Issue 2: High Variation in Candidate Gene Stability Values Across Different Algorithms

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Different algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt) use distinct statistical models to define "stability," which can lead to varying gene rankings [42] [43].

Issue 3: No Single Gene Shows Sufficient Stability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The experimental conditions (e.g., different tissues, severe stress treatments) cause high transcriptional variability, making no single gene truly stable.

- Solution: Shift your strategy from seeking a single perfect gene to identifying an optimal combination of genes. As demonstrated in research, a stable combination of non-stable genes often outperforms a single reference gene [40]. Both the iRGvalid and the gene combination methods support the evaluation of multi-gene panels.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The iRGvalid Workflow for Reference Gene Validation

This protocol is adapted from the iRGvalid method, which uses a double-normalization strategy to validate candidate genes [39].

Input Data Preparation:

- Obtain a RNA-seq dataset (e.g., from TCGA or a comparable source) with data from a large number of samples (

N) relevant to your study. - Compile a pool of candidate reference genes from literature or preliminary data.

- Ensure gene expression values are normalized (e.g., converted to TPM) and log2-transformed [Log2(TPM+1)].

- Obtain a RNA-seq dataset (e.g., from TCGA or a comparable source) with data from a large number of samples (

Double Normalization and Calculation:

- For a given target gene and a candidate reference gene, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (Rt) as follows:

- First Normalization: The expression of the target gene is normalized against the total gene expression level of each sample. (This step may be implicit in using TPM).

- Second Normalization: The target gene is normalized against the candidate reference gene using the formula:

Normalized Expression = Log2(TPM + 1)target - Log2(TPM + 1)ref. - Regression Analysis: Perform linear regression between the pre- and post-normalized target gene expression values across all

Nsamples.

- The Rt value (Pearson correlation coefficient) from this regression indicates stability. A value close to 1 indicates a highly stable reference gene for that target.

- For a given target gene and a candidate reference gene, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (Rt) as follows:

Evaluation:

- Repeat the process for all candidate genes and for multiple target genes.

- The best reference gene(s) will produce high Rt values regardless of the target gene used.

- The method can be extended to evaluate all possible combinations of candidate genes to find the most stable multi-gene panel.

The following diagram illustrates the iRGvalid workflow:

Protocol 2: Identifying an Optimal Gene Combination from RNA-seq Data

This protocol is based on a study showing that a combination of genes can outperform single stable genes [40].

Define Conditions and Target:

- Select a comprehensive RNA-seq database (e.g., TomExpress for tomato) that covers the biological conditions of interest.

- Identify your target gene and calculate its mean expression level across the dataset.

Create a Candidate Gene Pool:

- From all genes in the database, select a pool (e.g., N=500) of genes whose mean expression is greater than or equal to that of your target gene.

Find the Optimal k-Gene Combination:

- Choose a fixed number

k(e.g., k=3) for the combination. - Calculate the geometric mean profile for every possible combination of

kgenes from the pool. The geometric mean expression of the combination should be ≥ the target's mean expression. - Calculate the arithmetic mean profile for the same combinations.

- Select the optimal set of

kgenes that has the lowest variance in its arithmetic mean profile across all conditions.

- Choose a fixed number

Validation:

- The geometric mean of the expression levels of this optimal

k-gene combination is used for normalizing qPCR data.

- The geometric mean of the expression levels of this optimal

The following diagram illustrates the gene combination selection workflow:

► The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for In Silico Reference Gene Selection

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Description | Key Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA Biolinks [39] | An R/Bioconductor package for querying and downloading data from the NCI's The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). | Acquiring large-scale, disease-specific RNA-seq datasets for analysis. |

| RefFinder [42] [44] [43] | A web-based tool that integrates four algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt) to provide a consensus ranking of candidate reference genes. | Final validation and ranking of candidate genes identified from RNA-seq data. |

| iRGvalid Web App [39] | An interactive online application (built with R Shiny) that allows users to perform iRGvalid analysis by providing a target and candidate reference genes. | Easy implementation of the iRGvalid method without requiring extensive programming. |

| TomExpress [40] | A platform providing a comprehensive and publicly accessible RNA-seq database for the tomato plant model. Example of an organism-specific resource. | Serves as a model for the type of curated, condition-rich RNA-seq database needed for the gene combination method. |

| Primer-BLAST [41] | A tool for designing target-specific primers while checking for cross-homology with other sequences. | Designing high-quality, specific qPCR assays for the candidate reference genes selected in silico. |

The in silico selection of qPCR reference genes from RNA-seq data represents a paradigm shift in experimental design, moving validation from the bench to the computer. This approach enhances the robustness, efficiency, and reproducibility of gene expression studies. The core methodologies of iRGvalid and the Gene Combination Method provide powerful frameworks to leverage public data. Success depends on using a representative RNA-seq cohort, validating findings with integrated algorithms like RefFinder, and always confirming qPCR assay efficiency. By integrating these computational strategies, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of their qPCR data and its correlation with transcriptomic studies.

Leveraging Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Assays for Enhanced Validation

Integrated DNA and RNA sequencing assays represent a significant advancement in clinical genomics, moving beyond the limitations of DNA-only testing. By combining Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) from a single tumor sample, this approach substantially improves the detection of clinically relevant alterations in cancer, including somatic variants, gene fusions, and changes in gene expression [45]. This technical support center provides guidelines and troubleshooting for implementing these powerful combined assays, with a specific focus on improving the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR data—a critical step for robust clinical validation.

Key Experimental Protocols

The following section outlines the core methodologies for developing and validating an integrated DNA-RNA sequencing assay, as derived from recent, large-scale validation studies.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

This protocol is based on the BostonGene Tumor Portrait assay, validated on over 2,000 clinical samples [45].

Nucleic Acid Isolation:

- Solid Tumors (Fresh Frozen): Use the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

- Normal Tissue (Control): Use the QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (for whole blood or PBMCs) or the Maxwell RSC Stabilized Saliva DNA Kit (for saliva).

- FFPE Tissue: Use the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen).

- Quality Control (QC): Assess DNA and RNA quantity and quality using Qubit 2.0, NanoDrop OneC, and TapeStation 4200.

Library Preparation:

- Input: 10–200 ng of extracted DNA or RNA.

- RNA Library (FF tissue): Construct using the TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina).

- DNA & RNA Library (FFPE tissue): Construct using exome capture kits (SureSelect XTHS2 DNA and SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kits, Agilent Technologies).

- Hybridization and Capture: Use the SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR exome probe for RNA and the SureSelect Human All Exon V7 exome probe for DNA.

Sequencing:

- Platform: Perform on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina).

- QC Metrics: Monitor Q30 (>90%) and PF (>80%) during every run.

Bioinformatics Analysis

A rigorous bioinformatics pipeline is essential for accurate data interpretation [45].

Alignment:

- WES Data: Map to the human genome (hg38) using BWA aligner (v.0.7.17).

- RNA-seq Data: Map to the human genome (hg38) using STAR aligner (v2.4.2). For gene expression quantification, align reads to the human transcriptome (hg38) with Kallisto (v0.43.0).

Variant Calling:

- Germline and Somatic SNVs/INDELs: Detect using Strelka (v2.9.10) on paired tumor/normal samples.

- Somatic INDELs: Call using Strelka with small INDEL candidates from Manta (v1.5.0).

- RNA-seq Variants: Call using Pisces (v5.2.10.49).

Unique Molecular Index (UMI) Error Correction: To correct for sequencing or PCR errors, group reads with the same start-stop position and UMI into single-read families. Collapse these families using tools like GroupReadsByUmi and CallMolecularConsensusReads (fgbio) to generate a consensus read for variant calling [46].

A Framework for Validating RNA-seq and qPCR Correlation

Correlating RNA-seq with established qPCR data is a key validation step. The following protocol, informed by comparative studies, helps address technical disparities [4].

Sample Preparation:

- Use matched biological samples for both RNA-seq and qPCR assays (e.g., PBMCs from healthy donors).

- Extract total RNA using a kit such as the RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen), including a DNAse treatment step to remove genomic DNA.

- Quantify total RNA using a method like the HT RNA Lab Chip (Caliper).

qPCR Protocol:

- Design locus-specific primers for target genes (e.g., HLA-A, -B, -C).

- Perform amplification and quantification using standard qPCR procedures.

RNA-seq & HLA-Tailored Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process RNA-seq data through a standard pipeline (e.g., alignment with STAR).

- Crucially, for HLA and other polymorphic genes, employ an HLA-tailored pipeline that accounts for extreme polymorphism and minimizes alignment bias by incorporating known HLA allelic diversity. This step is vital for accurate expression estimation.

Data Correlation:

- Compare expression estimates for the target genes (e.g., HLA class I) from both techniques using correlation coefficients (e.g., Spearman's rho).

- Account for technical and biological factors that can cause variation between the two methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the development and execution of integrated DNA-RNA sequencing assays, as cited in the validation studies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing

| Item Name | Function / Application | Validation Context / Citation |

|---|---|---|

| AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Simultaneous isolation of DNA and RNA from a single fresh-frozen tissue sample. | Used for nucleic acid isolation from fresh frozen (FF) solid tumors [45]. |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) | Simultaneous isolation of DNA and RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples. | Used for nucleic acid isolation from FFPE solid tumors [45]. |

| TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina) | Preparation of sequencing libraries from RNA derived from fresh frozen tissue. | Used for library construction from FF tissue RNA [45]. |

| SureSelect XTHS2 DNA/RNA kits (Agilent) | Preparation of sequencing libraries from DNA and RNA derived from FFPE tissue. | Used for library construction from FFPE tissue [45]. |

| RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen) | Extraction of total RNA, including removal of genomic DNA. | Used for RNA extraction from PBMCs in comparative expression studies [4]. |

| xGen cfDNA & FFPE Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for challenging samples; utilizes UMIs for error correction. | Referenced for its use of UMIs to identify and correct sequencing or PCR errors [46]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Sequencing Preparation Problems

The table below summarizes frequent issues encountered during NGS library preparation, their root causes, and recommended solutions [21].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common NGS Library Preparation Issues

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input & Quality | Low yield; smear in electropherogram; low complexity. | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants; inaccurate quantification. | Re-purify input; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit); check 260/280 and 260/230 ratios [21]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks. | Over-/under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio. | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter ratios; ensure fresh ligase [21]. |

| Amplification & PCR | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias. | Too many PCR cycles; enzyme inhibitors; primer exhaustion. | Reduce PCR cycles; use master mixes to reduce pipetting error; ensure clean input [21]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of adapter dimers; high sample loss. | Wrong bead:sample ratio; over-drying beads; inefficient washing. | Precisely follow cleanup protocol; avoid bead over-drying; use "waste plates" to prevent accidental discarding [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I improve the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR data for gene expression, especially for highly polymorphic genes like HLA?

A: Achieving a strong correlation requires addressing specific technical challenges [4]:

- Use Matched Samples: Always use the same biological sample aliquot for both assays to eliminate biological variation.

- Employ HLA-Tailored Bioinformatics: Standard RNA-seq alignment to a single reference genome is inadequate for HLA genes. Use specialized computational pipelines designed for HLA that incorporate known allelic diversity to achieve accurate alignment and expression quantification.

- Understand Technical Disparities: The two methods measure related but different molecular phenotypes (e.g., transcript abundance vs. amplification efficiency). A moderate correlation (e.g., Spearman's rho between 0.2 and 0.53 for HLA class I genes) may reflect these inherent technical differences rather than a failure of either assay [4].

Q2: What is the role of UMIs in an integrated assay, and how are they used for error correction?

A: Unique Molecular Indexes (UMIs) are short, random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before PCR amplification [46]. They are used for two primary purposes:

- Removal of PCR Duplicates: All reads with the same start-stop position and the same UMI are considered PCR duplicates originating from a single original molecule and can be collapsed into a single consensus read.

- Error Correction: By grouping reads into families based on their UMI, a consensus sequence can be built that corrects for random sequencing errors or PCR errors that may have occurred in individual reads. This process improves the accuracy of subsequent variant calling [46].

Q3: Our assay validation revealed several gene fusions only in the RNA-seq data and not the DNA data. Is this expected?

A: Yes, this is a key advantage of integrated DNA-RNA sequencing. RNA-seq can directly detect expressed fusion transcripts, which may be missed by DNA-only assays for several reasons [45]:

- Complex Rearrangements: The DNA breakpoints may occur in large intronic or intergenic regions not covered by your DNA panel or exome capture.

- Detection Limit: The DNA allele frequency of a structural variant may be below the limit of detection, while the corresponding fusion transcript is highly expressed and readily detectable by RNA-seq.

- Validation studies have shown that integrating RNA-seq with WES significantly improves the detection of clinically actionable gene fusions and can reveal complex genomic rearrangements that would likely remain undetected without RNA data [45].

Q4: What is a comprehensive, step-by-step approach to validating an integrated DNA-RNA sequencing assay for clinical use?

A: Based on a large-scale validation study, a robust framework involves three critical steps [45]: