CASP Experiment: The Gold Standard in Protein Structure Prediction

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP), the community-wide experiment that has driven progress in computational biology for three decades.

CASP Experiment: The Gold Standard in Protein Structure Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP), the community-wide experiment that has driven progress in computational biology for three decades. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore CASP's foundational principles, its evolution in methodology from homology modeling to deep learning, and its role in validating groundbreaking tools like AlphaFold2. The article further details how CASP continues to tackle unsolved challenges in predicting protein complexes, RNA structures, and ligand interactions, while highlighting the real-world application of CASP-validated models in accelerating structural biology and therapeutic discovery.

CASP Unfolded: Understanding the Benchmark for Protein Folding

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, worldwide experiment that aims to advance methods of computing three-dimensional protein structure from amino acid sequence. Operating on a two-year cycle since 1994, CASP provides a rigorous framework for the blind testing of structure prediction methods, delivering an independent assessment of the state of the art to the research community and software users. The experiment was established in response to the fundamental challenge in molecular biology known as the "protein folding problem"—predicting a protein's native three-dimensional structure from its one-dimensional amino acid sequence. For decades, this problem stood as a grand challenge in science. CASP's primary goal has been to catalyze progress in solving this problem by objectively testing methods, identifying advances, and highlighting areas for future focus. The organization has become a cornerstone of structural bioinformatics, with more than 100 research groups regularly participating in what many view as the "world championship" of protein structure prediction [1] [2].

Historical Foundation and Key Objectives

The Mission of CASP

The mission of the Protein Structure Prediction Center, which organizes CASP, is to "help advance the methods of identifying protein structure from sequence." The Center facilitates the objective testing of these methods through the process of blind prediction [3]. The core components of this mission are the rigorous blind testing of computational methods and the independent evaluation of the results by assessors who are not participants in the predictions. By establishing the current state of the art, CASP helps identify what progress has been made and where future efforts may be most productively focused [3] [2].

A Brief History of CASP

CASP has been conducted every two years since its inception in 1994 [1]. The following table chronicles key developments over its thirty-year history.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of CASP Experiments

| CASP Round | Year | Key Milestones and Developments |

|---|---|---|

| CASP1 | 1994 | First experiment conducted [1]. |

| CASP4 | 2000 | First reasonable accuracy ab initio model built; residue-residue contact prediction introduced as a category [3] [1]. |

| CASP5 | 2002 | Secondary structure prediction dropped; disordered regions prediction introduced [1]. |

| CASP7 | 2006 | Introduction of model quality assessment and model refinement categories; redefinition of structure prediction categories to Template-Based Modeling (TBM) and Free Modeling (FM) [1]. |

| CASP11 | 2014 | First time a larger new fold protein (256 residues) was built with unprecedented accuracy; data-assisted modeling category included [3] [2]. |

| CASP12 | 2016 | Assembly modeling (complexes) assessed; notable progress from using predicted contacts [3]. |

| CASP13 | 2018 | Substantial improvement in template-free models using deep learning and distance prediction; won by DeepMind's AlphaFold [3] [1]. |

| CASP14 | 2020 | Extraordinary increase in accuracy with AlphaFold2; models competitive with experimental structures for ~2/3 of targets [3] [2] [1]. |

| CASP15 | 2022 | Enormous progress in modeling multimolecular protein complexes; accuracy of oligomeric models almost doubled [3]. |

| CASP16 | 2024 | Planned start in May 2024; includes special interest groups (SIGs) for continuous community engagement [3] [4]. |

In 2023, to foster continuous dialogue between the biennial experiments, CASP established three Special Interest Groups (SIGs): CASP-AI (focusing on artificial intelligence methods), CASP-NA (focusing on nucleic acid structure prediction), and CASP-Ensemble (focusing on conformational ensembles of biomolecules) [4]. These groups hold regular online meetings to discuss recent developments, helping to bridge gaps for newer members and between disciplines [4].

The CASP Experimental Protocol

The CASP experiment is designed as a rigorous double-blind test to ensure a fair assessment. Neither the predictors nor the organizers know the structures of the target proteins at the time predictions are made [1].

Target Selection and Release

Targets for structure prediction are proteins whose experimental structures (solved by X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or NMR spectroscopy) are soon-to-be made public or are currently on hold by the Protein Data Bank [1] [2]. In a typical CASP round (e.g., CASP14), structures of 50-70 proteins and complexes are received from the experimental community and released as prediction targets. For CASP14, these were divided into 68 tertiary structure targets and later organized into 96 evaluation units [2].

Prediction Categories and Evaluation Metrics

Predictors submit their computed structures within a strict timeframe (typically 3 weeks for human groups and 72 hours for automatic servers). The submitted models are then evaluated by independent assessors using a variety of metrics [2] [1].

Table 2: CASP Prediction Categories and Evaluation Methods

| Category | Description | Primary Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Tertiary Structure | Prediction of a single protein chain's 3D structure. | GDT_TS (Global Distance Test - Total Score), LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test) [2] [1]. |

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Modeling using evolutionary-related structures (templates). | GDT_TS, with targets classified as TBM-Easy or TBM-Hard based on difficulty [2] [1]. |

| Free Modeling (FM) | Modeling with no detectable homology to known structures (ab initio). | GDT_TS, with visual assessment for loose resemblances in difficult cases [1] [3]. |

| Assembly Modeling | Prediction of multimolecular protein complexes (quaternary structure). | Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1), LDDT of the interface (LDDTo) [3]. |

| Model Refinement | Improving the accuracy of a starting model. | Change in GDT_TS from the starting model [3]. |

| Contact/Distance Prediction | Predicting spatial proximity of residue pairs. | Precision of top-ranked predictions [3]. |

| Model Quality Assessment | Estimating the accuracy of a protein model. | Correlation between predicted and observed accuracy [1]. |

The GDTTS score is the primary metric for evaluating the backbone accuracy of tertiary structure models. It represents the percentage of well-modeled residues in the model compared to the experimental target structure, with a higher score indicating greater accuracy. A GDTTS above 50 generally indicates the correct fold, while scores above 90 are considered competitive with experimental accuracy [2] [1].

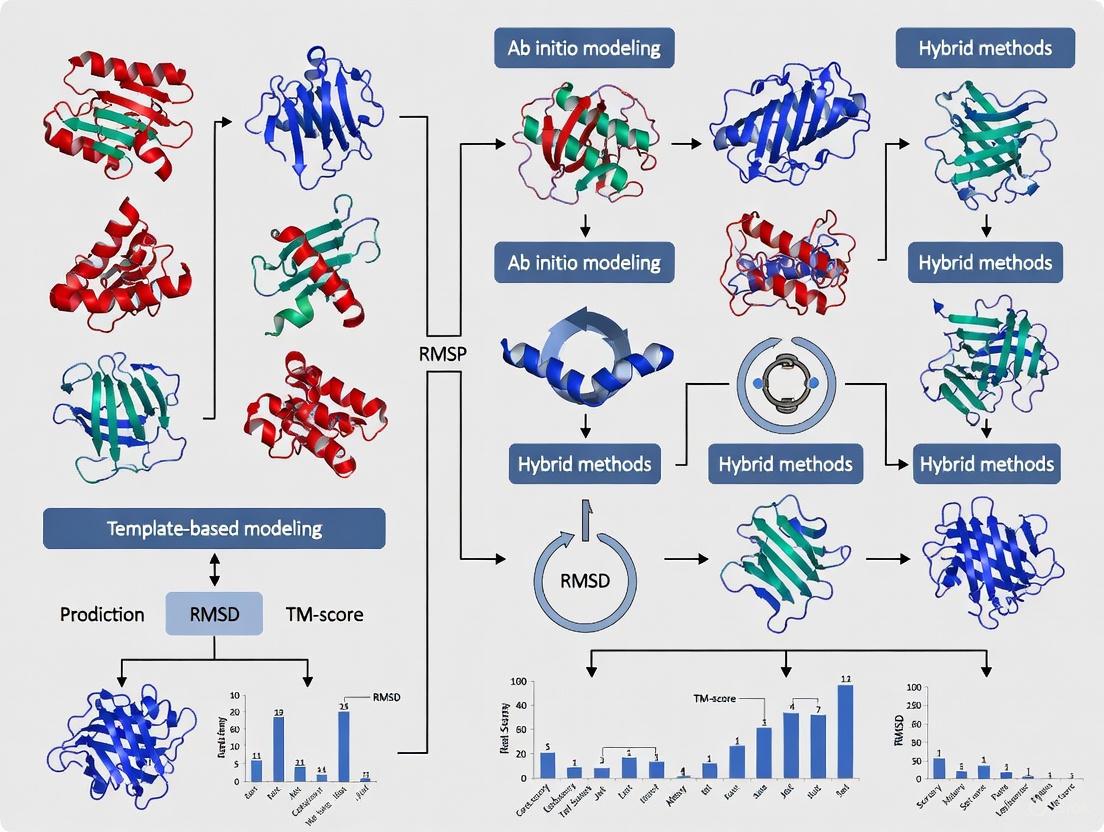

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow of a CASP experiment.

Quantitative Assessment of Progress

CASP's rigorous evaluation has provided clear, quantitative evidence of the remarkable progress in protein structure prediction, particularly in recent years.

The Leap in Accuracy in CASP14

CASP14 (2020) marked a watershed moment. The advanced deep learning method AlphaFold2, developed by DeepMind, produced models competitive with experimental accuracy for approximately two-thirds of the targets [2]. The trend line for CASP14 starts at a GDT_TS of about 95 for the easiest targets and finishes at about 85 for the most difficult targets. This represents a dramatic improvement over previous years, where accuracy fell off sharply for targets with less available evolutionary information [2].

Table 3: Historical Progress in CASP Backbone Accuracy (GDT_TS)

| CASP Round | Year | Approx. Average GDT_TS for Easy Targets | Approx. Average GDT_TS for Difficult Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP7 | 2006 | ~75 [3] | Significantly lower |

| CASP12 | 2016 | Information not available in sources | ~81 for a specific small domain (T0866-D1) [3] |

| CASP13 | 2018 | ~80 | ~65 [2] |

| CASP14 | 2020 | ~95 | ~85 [2] |

This leap in performance was not limited to a single group. The performance of the best servers in CASP14 was similar to the best performance of all groups in CASP13, indicating a rapid dissemination of advanced methods through the community [2].

Expansion into Complexes and Ensembles

Following the success in single-chain prediction, CASP has expanded its focus. CASP15 (2022) showed "enormous progress in modeling multimolecular protein complexes," with the accuracy of oligomeric models almost doubling in terms of the Interface Contact Score (ICS) compared to CASP14 [3]. Furthermore, the newly formed CASP-Ensemble SIG is exploring the assessment of conformational ensembles, recognizing that biomolecules adopt dynamic, multi-state structures rather than single static conformations [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The CASP experiment relies on a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table details key resources that form the foundation of modern structure prediction, as utilized by participants.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in CASP |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimentally solved protein structures used as templates and for method training [1]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Data | Collection of evolutionarily related sequences; provides information for deep learning methods on residue co-evolution and constraints [2] [4]. |

| AlphaFold2 & OpenFold | Software | End-to-end deep learning systems that predict protein 3D structure from amino acid sequence and MSA; set new standards in accuracy [2] [4]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Software | Computational simulations of physical movements of atoms and molecules; used for model refinement and studying dynamics [4]. |

| Rosetta | Software | A comprehensive software suite for de novo protein structure prediction and design, often used for template-free modeling and refinement [1]. |

| CASP Assessment Metrics (GDT_TS, LDDT) | Algorithm | Standardized metrics for objectively comparing the accuracy of predicted models against experimental structures [1] [2]. |

Over three decades, the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction has evolved from a small-scale challenge into a large, global community experiment that has fundamentally shaped the field. CASP has provided the objective framework necessary to measure progress, from the early days of comparative modeling to the recent revolution driven by deep learning. The mission to solve the protein folding problem has been largely achieved for single proteins, a conclusion starkly evidenced by the quantitative results from CASP14. The experiment now looks toward new frontiers, including the accurate prediction of multimolecular complexes, conformational ensembles, and the integration of computational models with experimental data to solve ever more challenging biological problems. Through its rigorous, blind assessment protocol and its engaged community, CASP continues to drive innovation, ensuring that computational structure prediction remains a powerful tool for researchers and drug development professionals worldwide.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, biennial experiment that has been the cornerstone of protein structure prediction research since 1994 [3] [1]. Its primary mission is to establish the state of the art in modeling protein structure from amino acid sequence through objective, blind testing of methods [5]. The integrity and scientific value of this massive undertaking—involving over 100 research groups submitting tens of thousands of predictions—rests upon a foundational principle: the double-blind protocol [5] [1]. This rigorous framework ensures that assessments are unbiased, progress is measured authentically, and the results faithfully guide the field's future direction. This paper deconstructs the double-blind methodology that empowers CASP to deliver authoritative evaluations of computational protein structure prediction.

The Mechanics of the Double-Blind Protocol

The double-blind protocol in CASP is a carefully orchestrated process designed to eliminate any possibility of subjective bias or unfair advantage. The "double-blind" nature means that two key parties in the experiment are kept ignorant of critical information until after predictions are submitted.

Target Selection and Anonymity

The process begins with the selection of "target" proteins whose structures have been recently determined experimentally but are not yet publicly available. These targets are typically structures soon-to-be solved by X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy, and are often held on hold by the Protein Data Bank [1]. The critical point is that the amino acid sequences of these targets are provided to predictors without any accompanying structural information [3].

The Two Key "Blinds"

- Predictors are blind to experimental structures: Participating research groups have no access to the experimental structures of the target proteins at the time they are making their predictions [1]. This prevents them from tailoring their methods to a known answer and forces algorithms to rely solely on the amino acid sequence and their underlying principles.

- Assessors are blind to predictor identity: The independent scientists who evaluate the accuracy of the submitted models do so without knowing which research group or method produced any given model [5]. This prevents any conscious or unconscious bias based on a group's reputation or past performance.

The entire workflow, from target release to final assessment, is summarized below.

Quantifying Success: CASP Evaluation Metrics

The objectivity of the double-blind protocol is complemented by rigorous, quantitative evaluation. The primary metric for assessing the backbone accuracy of a predicted model is the Global Distance Test Total Score (GDTTS) [1]. The GDTTS score, measured on a scale of 0 to 100, calculates the percentage of well-modeled residues in a model by measuring the Cα atom positions against the experimental structure [5] [1]. As a rule of thumb, models with a GDT_TS above 50 generally have the correct overall topology, while those above 75 contain many correct atomic-level details [5]. The dramatic progress in CASP, particularly with the advent of deep learning, is unmistakable when viewed through this objective lens.

Table 1: Key Evaluation Metrics in the CASP Experiment

| Metric/Aspect | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Global Distance Test Total Score; measures Cα atom positions [1]. | Primary score for backbone accuracy; >50 indicates correct fold, >75 high atomic-level detail [5]. |

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Category for targets with identifiable structural templates [1]. | Assesses ability to leverage evolutionary information from known structures. |

| Free Modeling (FM) | Category for targets with no detectable templates (most challenging) [1]. | Tests true de novo structure prediction capabilities. |

| Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1) | Measures accuracy of interfaces in multimeric complexes [3]. | Critical for evaluating the prediction of protein-protein interactions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents in CASP

The CASP experiment relies on a suite of "research reagents"—both data and software—that form the essential toolkit for participants and assessors alike.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Resources in CASP

| Resource | Type | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Target Sequences | Data | The fundamental input for predictors; amino acid sequences of soon-to-be-published structures [1]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Source of "on-hold" target structures and repository of known structures used for template-based modeling [1]. |

| CASP Prediction Center | Web Infrastructure | Central platform for distributing target sequences and collecting blinded model submissions [3]. |

| GDT_TS Algorithm | Software Tool | The standardized algorithm for quantifying model accuracy, ensuring consistent and comparable evaluation [1]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignments | Data | Evolutionary information derived from protein families; a critical input for modern deep learning methods [5]. |

The Fruit of Rigor: Key Outcomes Enabled by the Protocol

The strict adherence to the double-blind protocol has allowed CASP to authoritatively document the field's most groundbreaking achievements. The most profound of these was the confirmation in the CASP14 experiment that DeepMind's AlphaFold2 had produced models competitive with experimental accuracy for roughly two-thirds of the targets [2]. This milestone, validated through an unbiased process, represented a solution to the classical protein folding problem for single proteins [2]. The protocol has also reliably captured progress in other complex areas, such as multimeric protein complex prediction (CASP15 showed a near-doubling of accuracy in interface prediction) [3] and the utility of models for aiding experimentalists in solving structures via molecular replacement [3].

Table 3: Documented Progress in CASP Through Blind Assessment

| CASP Edition | Key Documented Advance | Quantified Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| CASP13 (2018) | Emergence of deep learning for contact/distance prediction [5]. | Best model accuracy (GDT_TS) on difficult targets sustained at >60 [5]. |

| CASP14 (2020) | AlphaFold2 demonstrates atomic-level accuracy [2]. | ~2/3 of targets had models competitive with experiment (GDT_TS >90) [2]. |

| CASP15 (2022) | Major progress in modeling multimolecular complexes [3]. | Interface prediction accuracy (ICS) almost doubled compared to CASP14 [3]. |

The double-blind protocol is the engine of credibility for the CASP experiment. By rigorously enforcing anonymity for both predictors and assessors, CASP generates an unbiased, quantitative record of the state of the art in protein structure prediction. This framework has proven its worth by reliably validating every major breakthrough in the field, from the early successes of statistical methods to the recent revolution driven by deep learning. As the field continues to tackle ever more complex challenges—such as the prediction of large multi-protein complexes and the conformational changes underling protein function—the double-blind protocol of CASP will remain the gold standard for objective assessment, ensuring that future progress is measured with the same unwavering rigor.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, blind experiment held every two years to objectively determine the state of the art in computing three-dimensional protein structures from amino acid sequences [1]. The primary goal of CASP is to advance computational methods by providing rigorous blind testing and independent evaluation [6] [7]. Since its inception in 1994, CASP has served as the gold-standard assessment, creating a unique framework where participants worldwide predict protein structures for sequences whose experimental structures are unknown but soon-to-be-solved [8] [1]. The experiment has witnessed dramatic progress, particularly with the introduction of deep learning methods like AlphaFold, which in recent rounds have demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental structures for single proteins and have spurred enormous advances in modeling protein complexes [3] [9] [10]. This technical guide delineates the complete lifecycle of a CASP target protein, from its selection as an unsolved biological puzzle to its final role in assessing cutting-edge prediction methodologies.

The CASP Lifecycle: A Stage-by-Stage Breakdown

The lifecycle of a CASP target is a meticulously orchestrated process involving collaboration between experimentalists, organizers, predictors, and assessors. The diagram below illustrates the core workflow and logical relationships between these stages.

Figure 1: The end-to-end workflow of a CASP target protein, from identification by experimentalists to final assessment and publication, highlighting the key stages and responsible parties.

Stage 1: Target Identification and Submission

The lifecycle begins when structural biologists submit prospective targets to the CASP organizers. Target providers are typically X-ray crystallographers, NMR spectroscopists, or cryo-EM scientists who have determined or expect to determine a protein structure whose coordinates are not yet publicly available [7] [1]. The preferred method is direct submission via the Prediction Center web interface, though email submission and designation during PDB submission are also available [9]. The critical requirement is that the experimental data must not be publicly available until after computed structures have been collected to maintain the blind nature of the experiment [9]. For CASP16, the deadline for target submission was July 1, 2024 [7].

Stage 2: Target Release and Predictor Registration

CASP organizers release approved targets through the official CASP website during the "modeling season". For CASP16, this ran from May 1 to July 31, 2024 [7]. Participation is open to all, and research groups must register with the Prediction Center [7]. The targets are announced with their amino acid sequences and sometimes additional information, such as subunit stoichiometry for complexes, which may be released in stages to test methods under different information conditions [7]. The experiment is double-blinded: predictors cannot access the experimental structures, and assessors do not know the identity of those making submissions during evaluation [8].

Stage 3: Sequence Analysis and Feature Generation

Upon receiving a target sequence, predictors conduct in-depth bioinformatic analyses. A crucial first step is the construction of a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) by gathering homologous sequences from genomic databases [8] [10]. For modern deep learning methods, the next step involves generating evolutionary coupling statistics and pairwise features that may indicate which residue pairs are likely to be in spatial proximity [11] [10]. Advanced methods like AlphaFold's Evoformer block then process these MSAs and residue-pair representations through repeated layers of a novel neural network architecture to create an information-rich foundation for structure prediction [10].

Stage 4: 3D Structure Prediction

This core stage involves translating the processed sequence information into atomic coordinates. The following table summarizes the primary methodologies employed for different prediction categories in CASP.

Table 1: Key Protein Structure Prediction Methodologies Assessed in CASP

| Method Category | Core Principle | Typical Applications | Key Innovations (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Identifies structural templates (homologous proteins of known structure) and builds models through sequence alignment and comparative modeling [3] [1]. | Proteins with detectable sequence or structural similarity to known folds. | More accurate alignment; combining multiple templates; improved regions not covered by templates [3]. |

| Free Modeling (FM) / Ab Initio | Predicts structure without detectable homologous templates, using physical principles or statistical patterns [3] [1]. | Proteins with novel folds or no detectable homology. | Accurate 3D contact prediction using co-evolutionary analysis and deep learning [3] [11]. |

| Deep Learning (e.g., AlphaFold) | Uses neural networks trained on known structures and sequences to directly predict atomic coordinates from MSAs and pairwise features [8] [10]. | All target types, with particularly high accuracy for single domains [6] [10]. | Evoformer architecture; end-to-end differentible learning; iterative refinement ("recycling") [10]. |

Stage 5: Model Submission

Predictors submit their final 3D structure models in a specified format through the Prediction Submission form or by email [7]. Each model contains the predicted 3D coordinates of all or most atoms for the target protein. For CASP16, approximately 100 research groups submitted more than 80,000 models for over 100 modeling entities, illustrating the massive scale of the experiment [7]. Server predictions are made publicly available shortly after the prediction window for a specific target closes, fostering a collaborative and transparent environment [7].

Stage 6: Experimental Structure Determination

In parallel with the prediction season, the target providers finalize their experimental structures. CASP requires the experimental data by August 15 for assessment, though the data can remain confidential until after the evaluation period [9]. These experimentally determined structures, solved through techniques like X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM, serve as the ground truth or "gold standard" against which all computational models are rigorously evaluated [6] [1].

Stage 7: Blind Assessment and Evaluation

Independent assessors, who are expert scientists not involved in the predictions, compare the submitted models with the experimental structures. The assessment employs quantitative metrics and qualitative analysis, with the specific criteria varying by prediction category.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating CASP Predictions

| Evaluation Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS (Global Distance Test Total Score) | The average percentage of Cα atoms in the model that can be superimposed on the native structure under multiple distance thresholds (1, 2, 4, and 8 Å) [8]. | 0-100 scale; higher scores indicate better overall fold accuracy. A score >~90 is considered competitive with experimental accuracy [6] [3]. | Single protein and domain structures [3]. |

| GDT_HA (High Accuracy) | Similar to GDT_TS but uses more stringent distance thresholds (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Å) [1]. | Measures high-quality structural agreement, particularly for well-predicted regions. | High-accuracy template-based models [1]. |

| lDDT (local Distance Difference Test) | A local, superposition-free score that evaluates the local consistency of distances in the model compared to the native structure [10]. | More robust to domain movements than global scores. Reported as pLDDT (predicted lDDT) by AlphaFold as an internal confidence measure [10]. | Local model quality and accuracy estimation. |

| ICS (Interface Contact Score) / F1 | For complexes, measures the accuracy of residue-residue contacts at the subunit interface [3]. | 0-1 scale; higher scores indicate more accurate protein-protein interaction interfaces. | Protein complexes and assemblies [3]. |

| RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | The average distance between equivalent atoms (e.g., Cα atoms) after optimal superposition [10]. | Measured in Ångströms (Å); lower values indicate better atomic-level accuracy. | Overall and local atomic accuracy. |

Stage 8: Results Publication and Knowledge Integration

The CASP lifecycle concludes with the public dissemination of results. All predictions and numerical evaluations are made available through the Prediction Center website [7]. A conference is held to discuss the results (for CASP16, tentatively scheduled for December 1-4, 2024) [7]. Finally, the proceedings, including detailed assessments, methods descriptions, and analyses of progress, are published in a special issue of the journal PROTEINS: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics [6] [7]. This completes the cycle, transforming a single target protein from a private sequence into a public benchmark that advances the entire field.

Successful navigation of the CASP lifecycle relies on a suite of computational and data resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for CASP

| Resource/Solution | Type | Primary Function in CASP |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | The single worldwide archive of structural data of biological macromolecules; provides the foundational training data for knowledge-based methods and stores the final experimental targets [8]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tools | Computational Tool | Generates alignments of homologous sequences from genomic databases; essential for extracting evolutionary constraints and co-evolutionary signals for contact prediction [8] [10]. |

| AlphaFold & Related DL Models | Software/Algorithm | Deep learning systems that directly predict 3D atomic coordinates from amino acid sequences and MSAs; represent the current state-of-the-art in accuracy [6] [10]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Computational Tool | Uses physics-based simulations for model refinement; can slightly improve initial models by sampling conformational space near the starting structure [11] [8]. |

| CASP Prediction Center | Web Infrastructure | The central hub for the experiment: distributes target sequences, collects submitted models, provides evaluation tools, and disseminates results [3] [7]. |

The lifecycle of a CASP target protein embodies a unique and powerful collaborative model in scientific research. From its genesis in an experimental lab to its role as a blind test for computational methods and its final contribution to published literature, each target plays a crucial part in driving the field forward. The rigorous, community-wide assessment provided by CASP has been instrumental in benchmarking progress, most notably catalyzing the revolutionary advances brought by deep learning. As the experiment continues to evolve, incorporating new challenges like protein-ligand complexes, RNA structures, and conformational ensembles, the structured lifecycle of a CASP target will remain fundamental to transforming amino acid sequences into biologically meaningful three-dimensional structures.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, blind experiment conducted every two years since 1994 to objectively assess the state of the art in computing protein three-dimensional structure from amino acid sequence [1]. This rigorous experiment provides a framework for testing protein structure prediction methods through blind testing, where predictors calculate structures for proteins whose experimental configurations are not yet public [3] [12]. A fundamental requirement of this assessment is objective, quantitative metrics to evaluate the accuracy of predicted models against experimentally determined reference structures. The Global Distance Test Total Score (GDT_TS) has emerged as the primary metric for this evaluation, serving as the gold standard for comparing predicted and experimental structures in CASP and beyond [13].

Understanding GDT_TS: Calculation and Interpretation

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Methodology

The Global Distance Test (GDT) was developed to provide a more robust measure of protein structure similarity than Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), which is sensitive to outlier regions caused by poor modeling of individual loops in an otherwise accurate structure [13]. The conventional GDT_TS score is computed over the alpha carbon atoms and is reported as a percentage ranging from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating closer approximation to the reference structure [13].

The GDT algorithm calculates the largest set of amino acid residues' alpha carbon atoms in the model structure that fall within a defined distance cutoff of their position in the experimental structure after iteratively superimposing the two structures [13]. The algorithm was originally designed to calculate scores across 20 consecutive distance cutoffs from 0.5 Å to 10.0 Å [13]. However, the standard GDT_TS used in CASP assessment is the average of the maximum percentage of residues that can be superimposed under four specific distance thresholds: 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ångströms [13].

Table 1: GDT_TS Distance Cutoffs and Their Implications

| Distance Cutoff (Å) | Structural Interpretation | Typical Accuracy Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Å | Very high atomic-level accuracy | Near-experimental quality |

| 2 Å | High backbone accuracy | Competitive with experiment |

| 4 Å | Correct fold determination | Structurally useful model |

| 8 Å | Overall topological similarity | Basic fold recognition |

Variations and Extended GDT Metrics

Over successive CASP experiments, the GDT framework has evolved to include specialized variants addressing specific assessment needs:

- GDT_HA (High Accuracy): Uses smaller cutoff distances (typically 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Å) to more heavily penalize larger deviations, emphasizing high-precision modeling [13]. This metric was introduced for the high-accuracy category in CASP7 [13].

- GDC_SC (Global Distance Calculation for Sidechains): Extends the assessment to side chain atoms using predefined "characteristic atoms" near the end of each residue [13].

- GDC_ALL (All-Atom GDC): Incorporates full-model information, evaluating the accuracy of all atoms rather than just the protein backbone [13].

GDT_TS in Practice: CASP Assessment and Performance Benchmarks

The CASP Assessment Framework

In CASP experiments, protein structures soon to be solved by X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy are selected as targets [1]. Predictors submit their models based solely on amino acid sequences, and these predictions are subsequently compared to the experimental structures when they become publicly available [14]. The evaluation occurs across multiple categories, with tertiary structure prediction being a core component throughout all CASP experiments [1].

Target structures are classified into difficulty categories based on their similarity to known structures: Template-Based Modeling Easy (TBM-Easy), TBM-Hard, Free Modeling/TBM (FM/TBM), and Free Modeling (FM) for the most challenging targets with no detectable homology [2]. Historically, model accuracy strongly correlated with these categories, but recent advances have substantially reduced this dependence [2].

Performance Benchmarks and Historical Progress

GDTTS has been instrumental in quantifying the remarkable progress in protein structure prediction, particularly the breakthroughs demonstrated in recent CASP experiments. According to CASP assessments, a GDTTS score of approximately 90 is informally considered competitive with experimental methods [14].

Table 2: CASP Performance Benchmarks and GDT_TS Interpretation

| GDT_TS Score Range | Interpretation | CASP Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| 90-100 | Competitive with experimental accuracy | AlphaFold2 CASP14 median: 92.4 GDT_TS [14] |

| 80-90 | High accuracy | CASP14 best models for difficult targets [2] |

| 60-80 | Correct fold with structural utility | CASP13 best performance for difficult targets [2] |

| <50 | Incorrect or largely inaccurate fold | Pre-deep learning era for difficult targets [2] |

The CASP14 experiment in 2020 marked a paradigm shift, with AlphaFold2 achieving a median GDTTS of 92.4 overall across all targets, with an average error of approximately 1.6 Ångströms [10] [14]. This performance was competitive with experimental structures for about two-thirds of the targets [2]. Surprisingly, the best model trend line in CASP14 started at a GDTTS of about 95 and finished at about 85 for the most difficult targets, demonstrating only a minor fall-off in accuracy despite decreasing evolutionary information [2].

Methodological Protocols: Calculating and Applying GDT_TS

Standard GDT_TS Calculation Protocol

The technical implementation of GDT_TS calculation follows a specific methodology:

- Input Preparation: The predicted model and experimental reference structure are prepared with identical amino acid sequences and residue numbering.

- Residue Correspondence Establishment: The algorithm establishes residue correspondence, typically assuming identical sequences for CASP targets.

- Iterative Superposition: The structures undergo iterative superposition to identify optimal alignment.

- Distance Calculation: For each residue, the Cα distance between the model and reference is calculated after superposition.

- Residue Counting at Cutoffs: The algorithm identifies the largest set of residues that can be superimposed under each distance cutoff (1, 2, 4, and 8 Å).

- Averaging: The final GDT_TS is computed as the average of these four percentages.

The following workflow visualizes this calculation process:

Accounting for Uncertainty in GDT_TS Measurements

Protein structures are not static entities but exist as ensembles of conformational states, introducing uncertainty in atomic positions that affects GDTTS measurements [15]. Research has demonstrated that the uncertainty of GDTTS scores, quantified by their standard deviations, increases for lower scores, with maximum standard deviations of 0.3 for X-ray structures and 1.23 for NMR structures [15]. This uncertainty arises from:

- Structural flexibility inherent in protein molecules

- Experimental limitations in structure determination methods

- Dynamic properties of target proteins

For high-accuracy models (GDT_TS > 70), the uncertainty is relatively small, but becomes more significant for lower-quality models [15]. Time-averaged refinement techniques for X-ray structures and ensemble approaches for NMR structures help quantify this uncertainty [15].

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Prediction and Validation

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Software Algorithm | Primary tool for GDT_TS calculation and structure comparison [13] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimental protein structures used for template-based modeling and method training [10] |

| AlphaFold | Prediction Method | Deep learning system that demonstrated GDT_TS scores competitive with experiment in CASP14 [10] [14] |

| CASP Assessment Data | Benchmark Dataset | Curated targets and predictions from past experiments for method development and validation [3] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) | Bioinformatics Data | Evolutionary information used as input for modern deep learning prediction methods [10] |

The GDTTS metric has proven indispensable for quantifying progress in protein structure prediction, particularly through the CASP experiments. As the field advances with deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 routinely producing models with GDTTS scores above 90 [10] [14], the role of GDTTS is evolving. While it remains crucial for assessing backbone accuracy, the focus is expanding to include all-atom accuracy, complex assembly prediction, and accuracy estimation [12] [7]. The continued development and refinement of assessment metrics like GDTTS and its variants will ensure rigorous evaluation of the next generation of structure prediction methods, furthering their application in drug discovery and basic biological research [16].

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, blind experiment established in 1994 to advance methods for computing three-dimensional protein structure from amino acid sequence [17] [3]. CASP operates as a rigorous testing ground where research groups worldwide predict protein structures that have been experimentally determined but not yet publicly released [6] [17]. By evaluating predictions against the experimental benchmarks, independent assessors establish the current state of the art, identify progress, and highlight areas for future focus [6] [3]. This experiment is foundational to structural biology because protein function is dictated by its 3D structure, and accurate prediction is crucial for understanding biological processes and accelerating drug development [17].

The Evolution of CASP Assessment Categories

The CASP experiment has systematically evolved its assessment categories to track progress across the diverse challenges in protein structure modeling. The core categories have matured in response to methodological breakthroughs.

Template-Based Modeling (TBM)

Template-Based Modeling assesses methods that build protein models using structures of related proteins as templates [3]. For over a decade, progress in this category was incremental, but CASP12 (2016) marked a significant acceleration in accuracy due to improved sequence-template alignment, multiple template combination, and better model refinement [3]. The emergence of deep learning in CASP14 created another step-change, with models achieving near-experimental accuracy (GDT_TS>90) for approximately two-thirds of targets [3].

Free Modeling (FM) /Ab InitioModeling

Free Modeling (originally called ab initio modeling) represents the most challenging task: predicting structures without identifiable templates from existing databases [3]. Early progress was limited to small proteins (~120 residues). CASP11 and CASP12 showed substantial improvements through the successful use of predicted contacts as constraints [3]. CASP13 registered another leap forward through deep learning techniques predicting inter-residue distances [3]. By CASP14, methods like AlphaFold2 produced models with backbone accuracy competitive with experiments for many targets, effectively solving aspects of the classical protein-folding problem for single domains [6] [17] [3].

Quaternary Structure (Assembly) Modeling

Assembly Modeling (assessment of multimolecular protein complexes) was introduced in CASP12 [3]. CASP15 (2022) demonstrated enormous progress, with accuracy nearly doubling in terms of Interface Contact Score (ICS) compared to CASP14 [3]. Deep learning methods originally developed for monomeric proteins were successfully extended to model oligomeric complexes, significantly outperforming earlier methods [6] [3].

Refinement

The Refinement category tests the ability of methods to improve model accuracy by correcting structural deviations from experimental reference structures [3]. CASP assessments have identified two methodological trends: molecular dynamics methods that provide consistent but modest improvements, and more aggressive methods that can achieve substantial refinement but with less consistency [3].

Contact Prediction

Contact Prediction evaluates the accuracy of predicting spatially proximate residue pairs in the native structure [3]. This category witnessed sustained improvement from CASP11 to CASP13, where precision jumped from 27% to 70% for the best-performing methods [3]. These advances directly contributed to improved accuracy in free modeling by providing strong constraints for 3D model construction [3].

Data-Assisted Modeling

Data-Assisted Modeling involves predicting structures using low-resolution experimental data (NMR, cross-linking, cryo-EM, etc.) combined with computational methods [3]. This hybrid approach has shown promise in improving model accuracy, as demonstrated in CASP12 where cross-linking assisted models showed significant improvement over non-assisted predictions [3].

Table: Key CASP Assessment Categories and Their Evolution

| Category | Primary Focus | Key Evolutionary Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Building models using known protein structures as templates | CASP12 (2016): Significant accuracy improvements through better alignment and template combination [3]CASP14 (2020): Deep learning methods (e.g., AlphaFold2) achieved near-experimental accuracy [3] |

| Free Modeling (FM) | Predicting structures without homologous templates (ab initio) | CASP11-12: Improved accuracy using predicted contacts as constraints [3]CASP13: Major leap from deep learning and distance prediction [3]CASP14: AlphaFold2 produced models competitive with experiment [6] [3] |

| Quaternary Structure (Assembly) | Modeling multimolecular protein complexes | CASP12: Category introduced [3]CASP15: Accuracy dramatically improved through extended deep learning methods [3] |

| Refinement | Improving model accuracy towards experimental structures | CASP10-14: Identification of consistent molecular dynamics methods and powerful but less consistent aggressive methods [3] |

| Contact Prediction | Predicting spatially proximate residue pairs | CASP11-13: Precision nearly tripled from 27% to 70% [3] |

| Data-Assisted Modeling | Combining computational methods with experimental data | CASP11-13: Demonstrated significant accuracy improvements when integrating experimental constraints [3] |

Quantitative Tracking of Progress in CASP

CASP employs rigorous quantitative metrics to evaluate prediction accuracy, allowing objective tracking of methodological progress across experiments. The Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) is a primary metric measuring the average percentage of Cα atoms in a model that fall within a threshold distance of their correct positions in the experimental structure after optimal superposition [3]. For assembly prediction, the Interface Contact Score (ICS or F1) measures accuracy in modeling residue-residue contacts across protein interfaces [3].

Table: Quantitative Progress Across CASP Experiments (2006-2022)

| CASP Experiment | Template-Based Modeling (Avg. GDT_TS) | Free Modeling (Avg. GDT_TS) | Contact Prediction (Top Precision %) | Notable Methodological Advances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASP7 (2006) | ~70-80 (est.) | ~40-50 (est.) | <10% (est.) | First reasonable ab initio models for small proteins [3] |

| CASP11 (2014) | ~75-85 (est.) | ~50-60 (est.) | 27% | Baker team ranked first; deep learning introduced for structure prediction [17] [3] |

| CASP12 (2016) | Significant improvement over CASP11 | Improved via predicted contacts | 47% | Burst of progress in TBM; contact prediction precision nearly doubled [3] |

| CASP13 (2018) | Continued improvement | 65.7 (from 52.9 in CASP12) | 70% | AlphaFold1 debut; substantial improvement in FM via deep learning and distance prediction [17] [3] |

| CASP14 (2020) | ~92 (average) | ~85 for difficult targets | No significant increase | AlphaFold2; models competitive with experiment for ~2/3 of targets [6] [3] |

| CASP15 (2022) | High accuracy maintained | High accuracy maintained | Data not shown | Assembly modeling accuracy nearly doubled (ICS) [3] |

Methodological Breakthroughs and Experimental Protocols

The extraordinary progress tracked by CASP has been driven by fundamental methodological breakthroughs, particularly the integration of deep learning and evolutionary information.

The Deep Learning Revolution

The transformation in protein structure prediction is exemplified by the evolution of AlphaFold. AlphaFold1 (CASP13) used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to analyze 2D maps of distances between amino acids, predicting inter-residue distances and optimizing structures using gradient descent [17]. AlphaFold2 (CASP14) implemented a radically different architecture that moved beyond predetermined distance constraints to directly process sequence information including multiple sequence alignments (MSA) and pair representations [17]. Its core innovation was the Evoformer module—a modified Transformer algorithm that uses attention mechanisms to learn complex relationships directly from amino acid sequences [17].

AlphaFold2's High-Level Workflow

Experimental Protocol in CASP

The CASP experimental protocol follows a rigorous blind assessment paradigm:

- Target Selection: Organizers provide amino acid sequences of proteins whose structures have recently been experimentally determined but not published [17].

- Prediction Phase: Participant groups submit their three-dimensional structure predictions using only sequence information [3].

- Assessment: Independent assessors evaluate predictions against experimental structures using standardized metrics like GDT_TS and ICS, without knowledge of which groups generated which models [6] [3].

- Results Publication: Comprehensive analysis is published in special issues of Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics [6] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents and Resources in Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function in Protein Structure Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository of experimentally determined protein structures used for method training and validation [17] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA) | Data | Collections of evolutionarily related sequences used to infer structural constraints and co-evolutionary patterns [17] |

| AlphaFold2 | Software | End-to-end deep learning system that predicts 3D structures from amino acid sequences with high accuracy [17] |

| Evoformer | Algorithm | Transformer-based architecture that processes MSA and pair representations to learn structural relationships [17] |

| CASP Targets | Dataset | Blind test cases with experimentally solved structures but unreleased coordinates, used for objective assessment [3] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules, used for structure refinement [3] |

CASP's evolving assessment categories have systematically tracked the field's transformation from modest template-based modeling to the accurate ab initio prediction of single proteins and complex multimolecular assemblies. The quantitative progress documented in CASP demonstrates that AI methods, particularly deep learning, have fundamentally changed structural biology [6] [17]. These advances have immediate practical applications, with CASP14 models already being used to solve problematic crystal structures and correct experimental errors [6] [3]. For drug development professionals, these breakthroughs enable rapid structural characterization of therapeutic targets, potentially accelerating drug discovery pipelines. As CASP continues to evolve its assessment categories to address more complex challenges like protein design and functional prediction, it will continue to serve as the essential benchmark for tracking progress in computational structural biology.

From Templates to AI: The Methodological Revolution in CASP

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biennial, community-wide blind experiment established in 1994 to objectively assess the state of the art in predicting protein three-dimensional structure from amino acid sequence [1]. It functions as a rigorous testing ground where predictors worldwide submit models for proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but are not yet public. Independent assessors then evaluate these submissions, providing an unbiased overview of methodological capabilities and progress [5]. Within this framework, Template-Based Modeling (TBM) has historically been the most reliable method for predicting protein structures when a related protein of known structure (a "template") can be identified [1] [3]. TBM leverages the evolutionary principle that structural homology is more conserved than sequence homology, allowing for the construction of accurate models even with low sequence similarity. This guide details the core methodologies, experimental validation, and practical applications of TBM within the context of CASP, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical overview of this foundational approach.

The CASP Experimental Framework for TBM

The Double-Blind Protocol

A cornerstone of the CASP experiment is its double-blind protocol, which ensures an objective assessment. Predictors receive only the amino acid sequences of the target proteins and have no access to the experimental structures during the prediction phase. Simultaneously, the assessors evaluate the submitted models without knowing the identity of the predictors [1] [5]. This eliminates bias and guarantees that the assessment purely reflects the predictive power of the computational methods.

Target Difficulty Categorization

CASP classifies targets based on their similarity to known structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), which directly dictates the applicability of TBM. The official CASP classification is as follows [2]:

- TBM-Easy: Targets for which straightforward homology modeling is possible, typically with clear and easily identifiable templates.

- TBM-Hard: Targets where homology modeling is still the primary approach, but the structural homology is more remote or difficult to detect, often requiring advanced sequence alignment or threading techniques [1]. It is critical to note that the distinction between TBM and the more challenging "Free Modeling" (FM) category has become increasingly blurred with the advent of deep learning methods like AlphaFold, which integrate principles from both categories to achieve remarkable accuracy [2].

Core Methodology of Template-Based Modeling

The TBM workflow is a multi-stage process that transforms a target sequence and a template structure into a refined 3D model. The following diagram illustrates the key steps and their logical relationships.

Step 1: Template Identification and Selection

The initial and crucial step is to identify one or more experimentally solved protein structures (templates) that are homologous to the target sequence.

- Experimental Protocols:

- Sequence-Based Search: Tools like BLAST or HHsearch are used to search the PDB for sequences with significant similarity to the target. A high sequence identity often indicates a suitable template [1].

- Protein Threading: For distantly related homologs where sequence identity is low, protein threading methods can be more effective. These methods score the compatibility of the target sequence with the structural folds of potential templates in the library, even in the absence of clear sequence similarity [1].

- Selection Criteria: The ideal template is selected based on factors including sequence identity, the quality and resolution of the experimental template structure, and coverage of the target sequence.

Step 2: Target-Template Alignment

A precise alignment between the target amino acid sequence and the sequence (and structure) of the template is generated. This alignment defines how the coordinates of the template will be transferred to the target.

- Experimental Protocols: This step can use the same tools as template identification (e.g., HHsearch). Advanced methods may employ iterative algorithms and multiple sequence alignment information to improve the accuracy of the alignment, especially in low-identity scenarios.

Step 3: Model Building

The core framework of the model is constructed by transferring the backbone coordinates from the template to the target based on the sequence alignment.

- Experimental Protocols:

- Copying Conserved Regions: Amino acids that are identical between the target and template can have their coordinates directly copied.

- Handling Variations: For aligned but non-identical residues, side-chain conformations are modeled. In regions where the target has an insertion not present in the template (a "gap" in the alignment), the structure must be built from scratch.

Step 4: Loop Modeling

Regions corresponding to gaps in the target-template alignment, typically loops, are the most variable and difficult to model. Specialized methods are required for this step.

- Experimental Protocols:

- Knowledge-Based Methods: Searching a database of protein loops for fragments that fit the geometric constraints of the "stem" regions.

- De Novo Methods: Using conformational sampling algorithms, such as those implemented in Rosetta, to generate and score possible loop conformations [1].

Step 5: Side-Chain Refinement

The conformations of side chains, even in well-aligned regions, are optimized to remove steric clashes and find energetically favorable rotamers.

- Experimental Protocols: This involves using rotamer libraries—statistical distributions of side-chain dihedral angles observed in high-resolution structures—and employing energy minimization algorithms to select the most stable conformations.

Step 6: Model Validation and Quality Assessment

The final model must be checked for structural integrity and reliability.

- Experimental Protocols:

- Geometric Checks: Tools like MolProbity assess stereochemical quality, including bond lengths, angles, and Ramachandran plot outliers.

- Physical Plausibility: Checking for atomic clashes, solvation energy, and other physicochemical properties.

- Model Quality Estimation: Methods like ModFOLD or ProQ2 estimate the local and global accuracy of the model, which is a dedicated assessment category in CASP [1].

Quantitative Assessment in CASP

Primary Metrics for Model Accuracy

The CASP assessment uses robust metrics to quantitatively compare predicted models against the experimental target structure. The primary metric for the backbone is the Global Distance Test (GDT). The most common variant is the GDTTS (Total Score), which represents the average of four values: GDT1, GDT2, GDT4, and GDT8. These correspond to the percentage of Cα atoms in the model that can be superimposed on the corresponding atoms in the experimental structure under different distance thresholds (1, 2, 4, and 8 Ångströms) [1] [2]. A higher GDTTS indicates a more accurate model.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating TBM Models in CASP

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Average percentage of Cα atoms within 1, 2, 4, and 8 Å of their correct positions after optimal superposition. | Primary measure of overall backbone accuracy. >90: Competitive with experiment. >80: High accuracy. >50: Generally correct fold [3] [2]. |

| GDT_HA | Same as GDT_TS but uses tighter distance thresholds (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Å). | Measures "High-Accuracy" details, assessing atomic-level precision. |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation of atomic positions (typically Cα atoms) between model and target. | Measures average deviation. Sensitive to local errors; less informative for global fold. |

| MolProbity Score | Comprehensive evaluation of stereochemistry, clashes, and rotamer outliers. | Validates the geometric and physical plausibility of the model. |

Documented Performance and Historical Progress

TBM has shown consistent and dramatic improvements over the history of CASP, driven by better algorithms, template libraries, and the integration of deep learning.

Table 2: Historical Progress of TBM Accuracy in CASP (Data compiled from CASP reports)

| CASP Round | Key Trends and Average Performance Highlights |

|---|---|

| CASP10 (2012) | Baseline for a decade of progress. Models were accurate but with room for improvement. |

| CASP12 (2016) | A "burst of progress": backbone accuracy improved more in 2014-2016 than in the preceding 10 years [3]. |

| CASP13 (2018) | Significant improvement driven by the integration of deep learning for contact/distance prediction, even for TBM targets [5]. |

| CASP14 (2020) | "Extraordinary increase" in accuracy. AlphaFold2 models for TBM targets reached an average GDT_TS of ~92, significantly surpassing models from simple template transcription [3]. |

The data shows that modern TBM methods, particularly those enhanced by deep learning, have moved beyond simple template transcription. They now produce models that are significantly more accurate than the best available templates, achieving near-experimental accuracy for the majority of targets [3] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TBM

Table 3: Key Resources for Template-Based Modeling

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in TBM |

|---|---|---|

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | The central repository of experimentally determined protein structures, serving as the source for all potential templates [1]. |

| BLAST | Software | Performs rapid sequence similarity searches to identify potential homologous templates in the PDB [1]. |

| HHsearch/HHblits | Software | Employs hidden Markov models (HMMs) for sensitive profile-based sequence searches and alignments, crucial for finding distant homologs [1] [5]. |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Provides powerful algorithms for de novo loop modeling, side-chain packing, and overall structural refinement, especially when template coverage is incomplete [1]. |

| Modeller | Software | A widely used package for comparative (homology) model building, which spatial restraints derived from the template to construct the target model. |

| MolProbity | Software | A structure-validation tool that checks the stereochemical quality of the built model, identifying clashes, rotamer outliers, and Ramachandran deviations. |

| AlphaFold2 | Software | A deep learning system whose architecture and training have revolutionized the field. While a full Free Modeling tool, its principles are now integrated into modern TBM pipelines, and its public models can serve as highly accurate starting templates [18]. |

Template-Based Modeling, rigorously tested and refined within the CASP experiment, remains a cornerstone of computational structural biology. The methodology has evolved from simple homology modeling to a sophisticated process that, when augmented by modern deep learning techniques, can produce models of near-experimental quality. The quantitative assessments from CASP unequivocally demonstrate this dramatic progress, with GDT_TS scores for TBM targets now consistently exceeding 90 for a majority of targets [3] [2]. For researchers in drug discovery, this level of accuracy makes TBM an indispensable tool for tasks ranging from understanding protein function and elucidating mechanisms of disease to structure-based drug design and virtual screening. The continued integration of experimental data (e.g., from cryo-EM, NMR, or cross-linking mass spectrometry) into the modeling process promises to further enhance the reliability and scope of TBM, solidifying its role as a critical technology for advancing human health.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, biennial experiment that serves as the gold standard for objectively testing computational methods that predict protein three-dimensional structure from amino acid sequence [1]. Since its inception in 1994, CASP has categorized the protein folding problem into distinct challenges, one of the most difficult being Template-Free Modeling (FM), also known as ab initio or de novo prediction [19] [1]. This category specifically addresses the prediction of protein structures that possess novel folds—those with no detectable structural homology to any known template in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [20] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to accurately model these novel folds is paramount for understanding the structure and function of proteins unique to pathogens or disease processes, where no prior structural information exists. The evolution of FM methodologies within the CASP framework, from early physical models to the recent revolution in deep learning, represents one of the most significant frontiers in computational structural biology.

The Theoretical Divide: Template-Based vs. Template-Free Modeling

Computational protein structure prediction methods are broadly classified into two categories:

- Template-Based Modeling (TBM): This approach leverages known protein structures (templates) that share evolutionary or structural relationships with the target sequence. It includes Homology Modeling, Comparative Modeling, and Threading (fold-recognition) [19]. TBM is highly reliable when sequence identity with a template is above 30%, but its major limitation is its inability to predict new protein folds not represented in existing databases [21] [19].

- Template-Free Modeling (FM): FM methods predict structure without relying on identifiable structural templates. They address the core of the "protein folding problem" by attempting to compute the native conformation—the one at the lowest Gibbs free energy level—from physical principles and knowledge-based statistics derived from known protein structures [21] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process and the position of FM within a generalized protein structure prediction workflow, as formalized by CASP:

Evolution of Methodologies in Template-Free Modeling

Early and Hybrid Methodologies

The immense conformational space available to even a small protein made exhaustive search impossible. Early FM strategies focused on reducing search space and designing effective energy functions to guide the search toward native-like states [21].

- Fragment Assembly: Pioneered by tools like ROSETTA, this method breaks the target sequence into short fragments (typically 1-20 residues) that are frequently retrieved from unrelated protein structures based on sequence similarity and local structure propensity [19] [22]. Full-length models are then assembled from these fragments using stochastic search algorithms like Monte Carlo simulations, guided by knowledge-based force fields that favor hydrophobic burial and specific steric interactions [22].

- Lattice Models: Approaches like TOUCHSTONE II represented protein conformations on discrete lattices, significantly simplifying the conformational search but potentially losing accuracy due to the discrete representation [21].

- Continuous Space Sampling: Methods like the one in RAPTOR++ aimed to sample protein conformations in a continuous space using directional statistics and Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) to model backbone angle distributions, thus avoiding the discretization artifacts of lattice models [21].

- Hybrid Approaches: As the field evolved, the line between TBM and FM blurred. Many successful "FM" predictors in CASP began using very remote templates or server predictions as starting points for further refinement [20]. Tools like Bhageerath and QUARK exemplify hybrid protocols that combine knowledge-based potentials from fragments with physics-based approaches [19].

The Deep Learning Revolution

A paradigm shift occurred with the integration of deep learning, particularly in CASP13 and CASP14.

- CASP13 (2018): Saw a substantial improvement in FM accuracy, primarily driven by the use of deep learning to predict inter-residue contacts and distances at various thresholds. This provided powerful spatial constraints that guided the model assembly process more effectively than previous methods [3] [2].

- CASP14 (2020): Marked an extraordinary breakthrough with AlphaFold2. It employed an end-to-end deep learning architecture based on an Evoformer neural network that jointly processed multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and pairwise features [2]. Rather than predicting contacts, it directly output accurate 3D coordinates. AlphaFold2's performance was so high that for about two-thirds of the targets, its models were considered competitive with experimental accuracy in backbone measurement (GDTTS >90) [3] [2]. The trend line for CASP14 started at a GDTTS of about 95 for easy targets and finished at about 85 for the most difficult FM targets, a dramatic reduction in the accuracy gap between TBM and FM [2].

The following workflow summarizes the key methodological evolution in FM:

Quantitative Assessment in CASP

Key Metrics for Evaluation

CASP employs rigorous, superposition-dependent and independent metrics to evaluate model quality. The primary measures for FM include:

- GDTTS (Global Distance Test Total Score): The primary metric in CASP, expressing the average percentage of Cα atoms in a model that can be superimposed on the corresponding atoms in the experimental structure within multiple distance thresholds (1, 2, 4, and 8 Å). A higher GDTTS (0-100 scale) indicates a better model, with scores above 50 generally indicating a correct fold [1] [2].

- TM-Score (Template Modeling Score): A protein size-independent metric that measures the structural similarity between a model and the native structure. A TM-score >0.5 indicates the same fold, while a score <0.17 indicates a random similarity [22].

- QCS (Quality Control Score) and Other Scores: CASP10 introduced additional superposition-independent scores to provide a more comprehensive assessment, especially for clustering and selecting the best models from a large pool of predictions [20].

Performance Evolution in CASP FM

The table below summarizes the quantitative progress in FM as observed through recent CASP experiments, highlighting the dramatic leap in performance.

Table 1: Evolution of Template-Free Modeling Performance in CASP

| CASP Experiment | Key Methodological Advance | Representative Performance on FM Targets (GDT_TS) | Noteworthy Tools/Servers |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP7 (2006) | Early fragment assembly and knowledge-based potentials | ~75 for small protein domains (e.g., T0283-D1) [3] | ROSETTA, RAPTOR++ [21] [3] |

| CASP9 & 10 | Hybrid approaches using remote templates; sustained progress for small proteins (<150 residues) [19] | Improved accuracy for targets up to 256 residues [3] | QUARK, Zhang-server (leading servers in CASP10) [20] |

| CASP12 (2016) | Use of predicted contacts as constraints for modeling | ~81 for specific targets (e.g., T0866-D1) [3] | – |

| CASP13 (2018) | Major improvement from deep learning-based contact/distance prediction | Average GDT_TS increased from 52.9 (CASP12) to 65.7 [3] | AlphaFold (v1), other DL methods [3] [2] |

| CASP14 (2020) | End-to-end deep learning (direct coordinate prediction) | Trend line: ~85 (difficult FM) to ~95 (easier FM); 2/3 of all targets had GDT_TS >90 [2] | AlphaFold2 [2] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FM

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in FM | Relevance to Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUARK | Software Suite / Server | Ab initio structure prediction by replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations guided by a knowledge-based force field and fragment assembly [22]. | Model novel drug targets for structure-based drug design when no templates exist. |

| ROSETTA | Software Suite | Comprehensive suite for macromolecular modeling; its ab initio protocol uses fragment assembly and a sophisticated energy function [19]. | Protein engineering, enzyme design, and protein-protein interaction prediction. |

| MODELER | Software Suite | Comparative modeling, but often used in conjunction with FM methods for loop modeling or final model refinement [21]. | Generate complete models where parts of a structure are novel and other parts are template-based. |

| PSI-BLAST | Algorithm / Database | Generates Position-Specific Iterated (PSI) multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to derive evolutionary profiles [21]. | Provides crucial evolutionary constraints for both traditional and modern DL-based FM methods. |

| PSIPRED | Algorithm | Predicts protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence [21]. | Offers structural constraints to guide the conformational search in knowledge-based FM. |

| AlphaFold2 | Deep Learning System | End-to-end deep network that directly predicts 3D atomic coordinates from sequence and MSA data [2]. | Generate highly accurate structural models for entire proteomes, revolutionizing target identification. |

| CASP Data Archive | Database | Repository of all CASP targets, predictions, and evaluation results for benchmarking new methods [3] [1]. | Benchmark in-house prediction pipelines and assess the expected accuracy for a given target class. |

The journey of Template-Free Modeling within the CASP experiment has evolved from a formidable challenge to a domain where computational methods, particularly deep learning, have demonstrated unprecedented accuracy. The field has transitioned from relying on physical principles and fragment assembly to leveraging deep learning-predicted constraints and, finally, to the end-to-end structure prediction embodied by AlphaFold2. This progress has effectively blurred the lines between FM and TBM, as the latest methods seem to rely less on explicit homologous templates and more on evolutionary information embedded in multiple sequence alignments [2].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the implications are profound. The ability to rapidly generate accurate structural models for proteins with novel folds opens new avenues for understanding disease mechanisms, exploring previously "undruggable" targets, and accelerating structure-based drug discovery. While challenges remain—particularly for large multi-domain proteins, dynamic ensembles, and membrane proteins—the advances showcased in CASP have irrevocably transformed the role of computational prediction in structural biology, making it an indispensable tool in the scientist's toolkit.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) stands as the global benchmark for evaluating protein folding methodologies. For decades, this biannual experiment quantified incremental progress but fell short of achieving the ultimate goal: computational prediction competitive with experimental structures. The 2020 CASP14 assessment marked a historic inflection point, characterized by the performance of AlphaFold2, an artificial intelligence system developed by DeepMind. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of how AlphaFold2's novel architecture redefined the possible in structural biology. We detail its core methodological breakthroughs, quantify its performance against experimental data and other methods, and summarize the subsequent ecosystem of AI tools it inspired. Furthermore, we contextualize its impact within the CASP framework and outline the new frontiers of research it has opened, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to the current and future landscape of protein structure prediction.

The CASP Experiment: The Benchmark for Protein Folding Research

Since 1994, the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) has served as a community-wide, blind experiment to objectively assess the state of the art in predicting protein 3D structure from amino acid sequence [1]. Its primary goal is to advance methods by providing rigorous, independent evaluation. During each CASP round, organizers release amino acid sequences for proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but are not yet public. Predictors worldwide submit their computed models, which are then compared against the ground-truth experimental structures [1] [2].

A key feature of CASP is its double-blind protocol; neither predictors nor organizers know the target structures during the prediction window, ensuring an unbiased assessment [1]. The evaluation is rigorous, relying on metrics like the Global Distance Test (GDT_TS), a score from 0-100 that measures the percentage of Cα atoms in a model positioned within a threshold distance of their correct location in the experimental structure [1] [2]. Historically, CASP targets have been categorized by difficulty, from Template-Based Modeling (TBM), where evolutionary related structures can guide prediction, to the most challenging Free Modeling (FM) category, which involves proteins with no recognizable structural homologs [2].

For over two decades, CASP documented steady but slow progress. However, as one overview noted, "accurate computational approaches are needed to address this gap" between the billions of known protein sequences and the small fraction with experimentally solved structures [10]. This longstanding challenge set the stage for a transformative breakthrough.

Before the Breakthrough: The Protein Folding Problem

The "protein folding problem" has been a grand challenge in biology for over 50 years. A protein's specific 3D structure, or native conformation, is essential to its function. Christian Anfinsen's pioneering work posited that this native structure is intrinsically determined by the protein's amino acid sequence [23]. Predicting this structure computationally from sequence alone proved immensely difficult.

Prior to the deep learning revolution, computational methods fell into two main categories [10] [23]:

- Template-Based Modeling (TBM): These methods relied on identifying evolutionarily related proteins of known structure (templates) in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) through sequence alignment. Models were built by copying and adapting the template structure. While often accurate when good templates existed, these methods failed for proteins without clear homologs.

- De Novo (or Free) Modeling: For proteins without templates, methods attempted to predict structure from physical principles and energy minimization. These approaches were computationally expensive and notoriously unreliable, especially for larger proteins.