Concordant vs Non-Concordant Genes: A Practical Guide for Validating RNA-Seq with qPCR

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, assess, and troubleshoot the concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR data.

Concordant vs Non-Concordant Genes: A Practical Guide for Validating RNA-Seq with qPCR

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, assess, and troubleshoot the concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR data. It covers the foundational definition of gene expression concordance, methodologies for comparative analysis, strategies for optimizing workflows to minimize discordance, and guidelines for experimental validation. By synthesizing current benchmarking studies and best practices, this guide aims to empower scientists to make informed decisions on when orthogonal validation is necessary and how to ensure the reliability of their transcriptomic findings in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Concordance in Gene Expression Analysis

Defining Concordant and Non-Concordant Genes

In the field of genomics, the terms "concordant" and "non-concordant" are fundamental to assessing the reliability and reproducibility of gene expression data. Concordant genes are those for which different analytical methods or technological platforms yield consistent results, confirming the robustness of the findings. In contrast, non-concordant genes show significant discrepancies between measurement methods, raising questions about their biological validity or highlighting technical limitations. The comparison between RNA-Seq and quantitative PCR (qPCR) has become a critical benchmark for establishing these definitions, as qPCR is widely regarded as a gold standard for validation. This guide provides an objective comparison of RNA-Seq performance against qPCR and other technologies, presenting experimental data and methodologies that define gene concordance in transcriptomic research.

Quantitative Comparison of Platform Concordance

The agreement between RNA-Seq and other technologies for gene expression measurement varies significantly based on the platform compared and the specific genes analyzed. The table below summarizes key concordance metrics from published studies.

Table 1: Concordance Rates Between RNA-Seq and Other Technologies

| Comparison Platforms | Overall Concordance Rate | Key Factors Affecting Concordance | Primary Source of Non-Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq vs qPCR | ~85% of genes show consistent fold changes [1] [2] | Gene expression level, fold change magnitude, gene length, number of exons [1] [2] | Low expression, small fold changes (<1.5), shorter genes [1] |

| RNA-Seq vs Microarrays | Highly variable (25%-60% for DEGs) [3] | Treatment effect size, biological complexity of the mode of action, gene expression abundance [3] | Weakly expressed genes; complexity of the biological endpoint [3] |

| RNA-Seq vs TempO-Seq | 80% of genes (15,480/19,290) had concordant levels [4] | Gene ontology; histone/ribosomal functions (non-concordant) vs. cellular structure (concordant) [4] | Platform-specific protocols (lysates vs purified RNA) and probe design [4] |

| RNA-Seq vs NanoString | Strong correlation (Spearman 0.78-0.88) [5] | Data distribution (Spearman preferred for RNA-Seq count data), specific gene set [5] | RNA-Seq's broader transcriptome coverage may detect additional genes [5] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Concordant vs. Non-Concordant Genes in RNA-Seq/qPCR Studies

| Characteristic | Concordant Genes | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Expression Level | Moderate to High [2] | Low [1] [2] |

| Typical Fold Change (FC) | Larger [1] | Small (FC < 2) [1] |

| Gene Structure | Longer, more exons [2] | Shorter, fewer exons [2] |

| Fraction of Total Genes | ~85% [2] | ~15% [1] [2] |

| Validation Need | Low | High |

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Assessment

Benchmarking RNA-Seq against qPCR

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of RNA-Seq workflows in quantifying differential gene expression by comparing results with whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data [2].

Key Methodology:

- Reference Samples: Utilize well-established RNA reference samples (e.g., MAQCA and MAQCB from the MAQC consortium) [2].

- RNA-Seq Workflows: Process sequencing reads through multiple bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., Tophat-HTSeq, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) to generate gene-level expression values (TPM or counts) [2].

- qPCR Benchmark: Use a wet-lab validated qPCR assay that covers all protein-coding genes. Normalized quantification cycle (Cq) values serve as the reference dataset [2].

- Concordance Analysis: Calculate log fold changes between sample groups (e.g., MAQCA vs. MAQCB) for both RNA-Seq and qPCR. Genes are classified as follows:

- Concordant: Both methods agree on differential expression status and direction.

- Non-Concordant: Methods disagree on differential expression status or show fold changes in opposite directions. Researchers often further categorize non-concordant genes based on the magnitude of fold change difference (ΔFC) between the platforms [2].

Cross-Platform Validation with Orthogonal Methods

Objective: To independently verify gene expression findings, particularly when a study's conclusions rely heavily on a small number of genes or when expression changes are subtle [1].

Key Methodology:

- Gene Selection: Focus verification efforts on key genes of interest, especially those with low expression levels or small fold changes, which are prone to non-concordance [1].

- Orthogonal Assays: Use qPCR or reporter gene fusions (e.g., eGFP, lacZ) to measure expression of the selected genes in the same original samples used for RNA-Seq [1].

- Expanded Application: Alternatively, use qPCR to measure the expression of key genes in additional sample sets (e.g., different strains, conditions, or time points) not included in the original RNA-Seq study to confirm the broader validity of the findings [1].

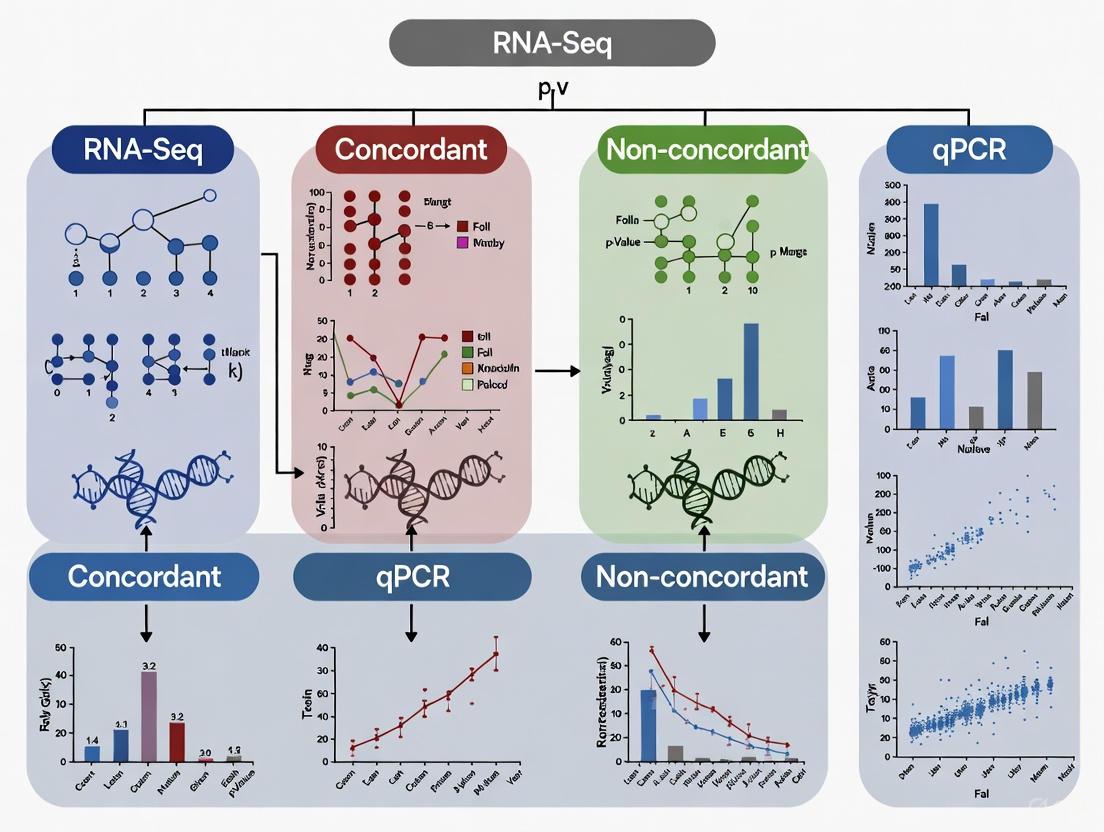

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

RNA-Seq Concordance Benchmarking Workflow

Decision Framework for Gene Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Concordance Studies

| Reagent / Platform | Primary Function | Role in Concordance Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples (e.g., MAQCA/MAQCB) | Standardized transcriptome material [2] | Provides a universal benchmark for cross-platform and cross-laboratory comparisons [2]. |

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries [6] | Ensures accurate assignment of reads to genes, reducing ambiguous mappings and improving concordance [6]. |

| Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Assays | Genome-wide expression profiling [2] | Serves as a gold-standard benchmark for validating RNA-Seq findings and defining concordant genes [2]. |

| TempO-Seq Assay | Targeted expression profiling from lysates [4] | Enables high-throughput screening without RNA purification; concordance with RNA-Seq is ~80% [4]. |

| NanoString nCounter Panels | Targeted digital quantification [5] | Provides amplification-free gene expression data; shows strong correlation with RNA-Seq (Spearman ~0.83) [5]. |

Defining concordant and non-concordant genes is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for ensuring the validity of genomic research. The data consistently show that while RNA-Seq exhibits high overall agreement with qPCR and other technologies, a subset of genes—characterized by low expression, small fold changes, and shorter length—is prone to non-concordance. Researchers should adopt a strategic approach to validation, leveraging standardized reagents and protocols. The decision to validate should be guided by the characteristics of the genes in question and their importance to the biological story. As technologies evolve, so too will our understanding of gene concordance, but the principles of rigorous benchmarking and orthogonal verification will remain fundamental to robust scientific discovery.

The Biological and Technical Meaning of Concordance

In the field of genomics, concordance measures the agreement between different experimental methods or data sets. In the specific context of comparing RNA-Seq and qPCR data, a pair of measurements for a gene is considered concordant when both techniques agree on its differential expression status (i.e., both identify it as significantly up-regulated, down-regulated, or not differentially expressed). Conversely, the measurements are non-concordant when the techniques disagree. Understanding the sources and implications of non-concordance is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on the accurate interpretation of transcriptome data to inform their work [1] [2].

Defining Concordance: From Genetics to Transcriptomics

The concept of concordance originates in classical genetics, where it describes the probability that a pair of individuals (most often twins) will both have a certain phenotypic trait, given that one of them has it [7]. This measures the similarity in phenotype between a set of individuals and helps disentangle genetic from environmental influences [8].

In the context of modern molecular biology and genotyping studies, the term has been adopted to describe the agreement between different data types. When DNA is directly assayed, concordance reflects the percentage of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are measured as identical across different technical platforms [7]. For transcriptomics, this concept is extended to the agreement between high-throughput RNA-Seq results and the traditional gold standard for gene expression measurement, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) [1] [2]. This specific application is the primary focus of this guide.

Benchmarking RNA-Seq Against qPCR: A Performance Comparison

RNA-Seq has become the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification. However, its performance is often benchmarked against qPCR, which is valued for its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [9]. A landmark study by Everaert et al. (as cited in [1]) comprehensively benchmarked five common RNA-Seq analysis workflows against wet-lab qPCR data for over 18,000 human protein-coding genes.

Key Experimental Findings

The study revealed that, depending on the computational workflow used, approximately 15–20% of genes showed non-concordant results when comparing RNA-Seq to qPCR data [1]. "Non-concordant" here was defined as instances where the two methods yielded differential expression in opposing directions, or where one method indicated significant differential expression while the other did not [1].

However, a deeper analysis of these non-concordant genes is revealing. The vast majority (approximately 93%) exhibited relatively small fold changes (below 2), and about 80% had fold changes below 1.5 [1]. This indicates that most disagreements occur for genes with subtle expression differences. Critically, only a very small fraction (approximately 1.8%) of genes were severely non-concordant, and these were typically characterized by lower expression levels and shorter gene length [1].

A separate, comprehensive benchmarking study published in Scientific Reports compared five RNA-seq workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, and Salmon) against whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data for the well-established MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples [2]. The table below summarizes the correlation and concordance results from this study:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows vs. qPCR

| Workflow | Expression Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Fold Change Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 18.5% |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | ~15.1% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 17.8% |

Data adapted from Everaert et al. and the MAQC benchmarking study [1] [2].

This study also confirmed that a significant proportion of the genes showing inconsistent results were reproducibly identified across independent datasets and were consistently associated with specific gene features [2].

Characteristics of Non-Concordant Genes

Genes that are prone to non-concordant results are not random. Multiple studies have identified common characteristics that make a gene more likely to yield disagreeing results between RNA-Seq and qPCR:

- Low Expression Level: Genes with very low transcript abundance are a major source of discrepancy [1] [2].

- Short Gene Length: Shorter genes provide fewer sequencing reads for accurate quantification, increasing the potential for technical variance [1].

- Fewer Exons: Genes with fewer exons exhibit similar technical challenges as short genes [2].

- Small Fold Changes: As noted, the vast majority of non-concordant results occur when the actual fold change in expression is small (e.g., < 2) [1].

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Analysis

To ensure reliable and reproducible results when comparing RNA-Seq and qPCR data, adherence to standardized protocols is paramount. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in benchmarking studies.

Protocol 1: Whole-Transcriptome Benchmarking

This protocol is based on the benchmarking study that used MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples [2].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain established reference RNA samples (e.g., MAQCA/UHRR and MAQCB/Brain Reference RNA).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare RNA-Seq libraries according to a standardized, high-quality protocol (e.g., Illumina). Sequence on an appropriate platform to achieve sufficient depth (e.g., >30 million reads per sample).

- qPCR Assay Design: Design wet-lab validated qPCR assays that cover all protein-coding genes. Each assay detects a specific subset of transcripts that contribute proportionally to the final gene-level quantification cycle (Cq) value.

- Data Alignment: For transcript-level RNA-Seq workflows (Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon), aggregate transcript-level values (e.g., TPM) to the gene level based on the transcripts detected by the corresponding qPCR assay. For gene-level workflows (HTSeq), convert gene counts to TPM.

- Filtering: Apply a minimal expression filter (e.g., >0.1 TPM in all samples) to avoid bias from low-expressed genes.

- Analysis:

- Calculate mean expression across replicates.

- For expression correlation, compute Pearson correlation between normalized qPCR Cq-values and log-transformed RNA-Seq TPM values.

- For fold-change correlation, calculate log fold changes between sample types (e.g., MAQCA vs. MAQCB) for both RNA-Seq and qPCR, then compute correlation.

Protocol 2: Orthogonal Validation with qPCR

This protocol outlines the use of qPCR to validate specific findings from an RNA-Seq experiment [1].

- Candidate Gene Selection: Select genes for validation based on the RNA-Seq results. Priority should be given to genes that are central to the biological story, especially if they have low expression levels and/or small fold changes [1].

- RNA Sample Selection: Use the same RNA samples that were subjected to RNA-Seq.

- Reference Gene Selection: Do not rely on traditionally used housekeeping genes (e.g., Actin, GAPDH) without verification. Use tools like GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) to identify the most stable, highly expressed reference genes from your RNA-Seq dataset specific to your biological conditions [9].

- qPCR Execution: Perform reverse transcription and qPCR following the MIQE guidelines (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) to ensure experimental rigor [1].

- Data Analysis: Use stable reference genes to normalize the qPCR Cq values. Calculate fold changes and compare the direction and magnitude of change to the results obtained from the RNA-Seq analysis.

Visualizing RNA-Seq and qPCR Concordance Analysis

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process for assessing concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR, from experimental design to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key research reagents and computational tools essential for conducting robust concordance studies between RNA-Seq and qPCR.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Concordance Studies

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Biological Reagent | Well-characterized RNA pools (e.g., MAQCA/UHRR, MAQCB) used as benchmarks for platform and workflow comparisons [2]. |

| Stable Reference Genes | Biological Reagent | Genes with high and stable expression across experimental conditions, used for normalizing qPCR data. Identified from RNA-seq data using tools like GSV [9]. |

| Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Assays | Molecular Biology Reagent | A set of validated qPCR assays designed to quantify the expression of all protein-coding genes, serving as a gold standard for RNA-Seq validation [2]. |

| GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) Software | Computational Tool | Identifies the most stable (reference candidate) and most variable (validation candidate) genes from RNA-seq data, ensuring they are highly expressed enough for qPCR detection [9]. |

| RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows | Computational Tool | Software pipelines (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) for processing raw sequencing reads into gene-level expression counts or abundances [2]. |

The biological and technical meaning of concordance in RNA-Seq and qPCR research centers on the reliable agreement of gene expression measurements. Current evidence demonstrates that when best practices are followed, RNA-Seq provides highly reliable data that, for the majority of genes, does not require systematic validation by qPCR [1]. Disagreements are not random but are systematically associated with genes that have low expression, short length, and subtle fold changes. Therefore, orthogonal validation with qPCR remains critical in specific scenarios, particularly when a biological conclusion hinges on the expression pattern of a small number of genes that fall into these problematic categories. By leveraging standardized protocols, understanding the sources of non-concordance, and utilizing modern bioinformatics tools, researchers can make informed decisions on validation strategies, thereby increasing the efficiency and robustness of their transcriptomic studies.

In the fields of genomics and drug development, concordance—the consistency of results across different experimental methods or platforms—is not merely a technical metric but a cornerstone of scientific validity. This guide objectively compares the performance of major gene expression technologies, specifically RNA-Seq and qPCR, by examining experimental data on their concordance. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on the critical importance of distinguishing between concordant and non-concordant genes, as this distinction directly impacts the reliability of biological interpretations and the success of downstream applications in biomarker discovery and toxicology.

In genetic research, concordance often refers to the agreement between different methodologies measuring the same biological phenomenon. High concordance strengthens confidence in results, while low concordance reveals methodological limitations or biological complexity. For gene expression analysis, a key challenge lies in the transition between established technologies like quantitative PCR (qPCR) and modern high-throughput methods like RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq). While RNA-seq offers an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, qPCR is often considered the "gold standard" for targeted validation due to its sensitivity and precision [10] [2]. Understanding the factors that drive concordance between these platforms, such as gene expression abundance and treatment effect size, is therefore paramount for designing robust research protocols and accurately interpreting data in both basic research and drug development pipelines [2] [3].

Cross-Platform Concordance: A Data-Driven Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental findings from comparative studies, highlighting the performance of RNA-seq and qPCR across different conditions.

Table 1: Correlation Between RNA-seq and qPCR for Gene Expression Measurement

| Study Focus | Correlation Range (Pearson R²) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| HLA Class I Genes (A, B, C) [10] | 0.20 - 0.53 | Extreme polymorphism of HLA genes; technical and biological variation. |

| Protein-Coding Genes (MAQC samples) [2] | 0.798 - 0.845 (Expression) 0.927 - 0.934 (Fold-change) | Gene expression level; specific bioinformatic workflow used. |

| Differential Gene Expression [3] | Agreement improves with larger treatment effect | Treatment effect size; biological complexity of the mode of action. |

Table 2: Characteristics of Concordant vs. Non-Concordant Genes

| Feature | Concordant Genes | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Higher expressed [2] | Lower expressed [2] [3] |

| Gene Structure | Larger, more exons [2] | Smaller, fewer exons [2] |

| Impact on Analysis | Reliable for downstream analysis | Require careful validation [2] |

| Fraction in DGE | ~80-85% of genes [2] | ~15-20% of genes [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Concordance Assessment

To ensure the reliability of the data presented in the comparisons, the following standardized protocols are typically employed in concordance studies.

Protocol 1: RNA-seq and qPCR Comparison for HLA Genes

This protocol is designed to address challenges in quantifying expression of highly polymorphic genes [10].

- Sample Preparation: RNA is extracted from freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors. The RNA is treated with DNAse to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing: Total RNA is quantified, and RNA-seq libraries are prepared. Sequencing is performed on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- HLA-Tailored Bioinformatic Analysis: RNA-seq reads are processed using a specialized computational pipeline that accounts for extreme HLA polymorphism and minimizes alignment bias against a single reference genome. Expression levels for HLA-A, -B, and -C are estimated.

- qPCR Analysis: For the same set of samples, qPCR assays are run for each HLA class I gene using specific primers and probes.

- Data Correlation: Expression estimates from RNA-seq and qPCR for each HLA gene are compared using statistical correlation measures (e.g., Spearman's correlation coefficient).

Protocol 2: Benchmarking RNA-seq Workflows Against Genome-Wide qPCR

This protocol uses well-characterized reference samples to benchmark multiple RNA-seq analysis workflows [2].

- Reference Samples: The MAQCA (Universal Human Reference RNA) and MAQCB (Human Brain Reference RNA) samples are used as biologically distinct benchmarks.

- Whole-Transcriptome qPCR: A wet-lab validated qPCR assay for 18,080 protein-coding genes is performed to generate a gold-standard expression dataset.

- RNA-seq and Workflow Processing: RNA-seq is performed on the same samples. The sequencing reads are processed using five distinct workflows:

- Alignment-based: Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq.

- Pseudoalignment-based: Kallisto, Salmon.

- Data Alignment and Normalization: Transcripts detected by qPCR are aligned with transcripts quantified by RNA-seq. Gene-level expression values are normalized and transformed to TPM (Transcripts Per Million) for cross-platform comparison.

- Concordance Metrics: Correlation of expression intensities and fold-changes (MAQCA vs. MAQCB) between qPCR and each RNA-seq workflow is calculated. Genes are categorized as concordant or non-concordant based on their differential expression status.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The relationship between experimental factors and concordance, as well as the workflow for a typical study, can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Factors influencing cross-platform concordance in genomics.

Diagram 2: A typical workflow for a cross-platform concordance study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and their functions essential for conducting rigorous gene expression concordance studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Concordance Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples (e.g., UHRR, Brain RNA) | Provides a stable, well-characterized benchmark for cross-platform and cross-laboratory comparisons [2] [3]. |

| DNAse I Enzyme | Critically removes contaminating genomic DNA during RNA isolation to ensure accurate RNA-only quantification [10]. |

| Poly-A Spike-In Controls | RNA molecules added in known quantities to samples to monitor technical performance and normalization efficiency of RNA-seq [3]. |

| HLA-Tailored Alignment Software | Specialized bioinformatic tools (e.g., specific to HLA genes) are essential for accurate quantification of polymorphic or complex gene families [10]. |

| Stable qPCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mixture containing polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer, ensuring high sensitivity and reproducibility for qPCR validation [2]. |

| Validated qPCR Assays | Pre-designed primer and probe sets with confirmed specificity and efficiency for target genes, crucial for reliable comparison data [2]. |

The implications of concordance extend directly into the drug development pipeline, where decisions are based on transcriptomic data.

Predictive Toxicology and Biomarker Discovery: In toxicology, the concordance between animal models and human responses is a critical focus. Large-scale analyses have confirmed the general predictivity of animal safety observations for humans, identifying specific predictive toxicities while also highlighting limitations in negative predictivity [11]. Furthermore, cross-platform concordance enables the identification of robust biomarkers. For instance, a machine learning approach identified OAS1 as a key gene signature for Ebola infection using NanoString data; this signature maintained 100% predictive accuracy when applied to RNA-seq data from the same cohort and an independent test set, demonstrating the power of concordant findings [5].

Regulatory Science and Clinical Validity: Regulatory science initiatives like the MAQC/SEQC projects have demonstrated that the agreement between RNA-seq and microarrays in identifying differentially expressed genes and pathways is strongly correlated with treatment effect size [3]. This understanding is crucial for fit-for-purpose application of technologies in regulatory submissions. Similarly, in genetic screening, the clinical validity of expanded carrier screening panels is assessed through variant classification concordance with public databases, ensuring patients receive accurate risk assessments [12].

In conclusion, a rigorous, data-driven understanding of concordance is not an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement. It underpins the selection of appropriate technologies, the validation of novel findings, and the ultimate translation of basic research into safe and effective therapeutics. Acknowledging and systematically investigating the factors that create both concordant and non-concordant genes is what separates reliable, reproducible science from mere data generation.

The transition from microarray technology to RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) represents a pivotal shift in molecular biology, fundamentally altering approaches to gene expression validation. Microarrays, which rely on hybridization-based detection with predefined probes, long served as the workhorse for genome-wide expression profiling [13]. Their dominance, however, was accompanied by persistent concerns regarding reproducibility, bias, and the accuracy of fold-change measurements, which necessitated systematic validation using orthogonal methods like quantitative PCR (qPCR) [14] [1]. This established the historical precedent that genome-scale expression findings required confirmation by alternative techniques.

The emergence of RNA-seq as a sequencing-based alternative promised to overcome many microarray limitations, offering a wider dynamic range, superior sensitivity, and the ability to detect novel transcripts without prior sequence knowledge [15] [13]. A critical question then emerged: does this technologically superior platform inherit the same requirement for extensive validation? This guide objectively compares the performance of these platforms and examines the evolving paradigm of concordance checking in the RNA-seq era, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and methodologies to inform their validation strategies.

Technological Comparison: Microarrays vs. RNA-Seq

Fundamental Mechanisms and Capabilities

The core distinction between these platforms lies in their fundamental mechanism: microarrays utilize hybridization of labeled cDNA to immobilized probes, whereas RNA-seq directly sequences cDNA molecules using next-generation sequencing platforms [13]. This difference underlies their divergent capabilities and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Core Technological Differences Between Microarrays and RNA-Seq

| Feature | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-based |

| Prior Sequence Knowledge | Required [13] | Not required [13] |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ [13] | >10⁵ [13] |

| Novel Transcript Detection | No [13] | Yes (splice variants, fusions, novel genes) [13] |

| Background Noise | Higher due to cross-hybridization [16] | Lower [16] |

| Quantification Nature | Analog (fluorescence intensity) | Digital (read counting) |

Performance Benchmarking in Differential Expression Analysis

Multiple studies have systematically compared the abilities of both platforms to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs), often using qPCR as a reference standard. While both technologies generally show good concordance with qPCR, the specific strengths of RNA-seq are evident.

A comprehensive benchmarking study using the well-characterized MAQC samples compared five RNA-seq workflows against a transcriptome-wide qPCR dataset for 18,080 protein-coding genes [15]. The results demonstrated high fold-change correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR across all workflows (R² ≈ 0.93) [15]. However, a fraction of genes (15-19%) showed non-concordant differential expression status between RNA-seq and qPCR. Crucially, over 93% of these non-concordant genes had fold changes below 2, and the small subset (≈1.8%) with severe discrepancies were typically lower expressed and shorter [1] [15]. This indicates that RNA-seq is highly reliable for genes with substantial expression changes but requires careful interpretation for genes with low expression or subtle fold-changes.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Predicting Protein Expression and Clinical Endpoints (TCGA Data Analysis)

| Cancer Type | Performance in Predicting Protein Expression (RPPA) | Survival Prediction Model Performance (C-index) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LUSC) | 16 genes showed significant correlation differences; e.g., CCNE1 and CCNB1 [17] | Microarray model superior [17] |

| Colon Adenocarcinoma (COAD) | BAX gene showed recurrent significant correlation differences [17] | Microarray model superior [17] |

| Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma (KIRC) | BAX and PIK3CA genes showed significant correlation differences [17] | Microarray model superior [17] |

| Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma (OV) | BAX gene showed significant correlation differences [17] | RNA-seq model superior [17] |

| Uterine Corpus Endometrioid Carcinoma (UCEC) | Not specified in results | RNA-seq model superior [17] |

| Breast Invasive Carcinoma (BRCA) | PIK3CA gene showed significant correlation differences [17] | Not specified in results |

Recent toxicogenomic studies further contextualize this comparison. A 2025 concentration-response study of cannabinoids found that while RNA-seq identified more DEGs with a wider dynamic range, both platforms revealed equivalent functional pathways through gene set enrichment analysis and produced nearly identical transcriptomic points of departure (tPODs) for risk assessment [16]. This suggests that for traditional applications like mechanistic pathway identification, microarrays remain a viable, lower-cost option [16].

The Shifting Validation Paradigm: From Mandatory to Context-Dependent

The Microarray Era: Systematic Validation as a Necessity

The historical need for validating microarray results stemmed from several technological limitations. Hybridization-based detection was susceptible to technical artifacts, including probe-specific biases, cross-hybridization, and signal saturation [14] [1]. These issues prompted calls for microarray results to be validated with other technologies before publication [14].

Methodological research from this period established best practices for global validation. Studies demonstrated that selecting only the most significantly differentially expressed genes for validation was a flawed strategy, as it was susceptible to regression toward the mean and did not generalize to the entire set of DEGs [14]. Instead, random-stratified sampling was recommended to provide a representative subset of genes for validation [14]. Furthermore, the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) was identified as a superior statistical metric over simple correlation, as it captures both precision (proximity to the regression line) and accuracy (deviation from the identity line) [14].

The RNA-Seq Era: Rethinking the "Validation Rule"

With the advent of RNA-seq, the consensus on mandatory validation has shifted. Unlike microarrays, RNA-seq does not suffer from the same issues of cross-hybridization or limited dynamic range, and multiple studies have demonstrated a high level of concordance with qPCR measurements [1].

A key study concluded that if all experimental steps and data analyses are performed according to state-of-the-art protocols with sufficient biological replicates, the added value of routinely validating RNA-seq data with qPCR is likely to be low [1]. The same analysis noted that while approximately 15-20% of genes might show non-concordant results between RNA-seq and qPCR depending on the workflow, the vast majority of these (93%) involve fold changes lower than 2, and the genuinely problematic discrepancies affect only about 1.8% of genes, typically those with low expression [1].

The contemporary perspective is that validation should be context-dependent. Orthogonal validation (e.g., by qPCR or reporter fusions) remains appropriate when:

- An entire biological story hinges on the differential expression of only a few genes.

- The genes of interest have low expression levels and/or small differences in expression.

- The data will be used to measure the same genes in additional samples, strains, or conditions not profiled by RNA-seq [1].

Diagram Title: The Evolving Paradigm of Transcriptomic Validation

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Assessment

A Framework for Benchmarking RNA-Seq Workflows

The following methodology is adapted from a comprehensive benchmarking study that compared RNA-seq workflows against a gold-standard qPCR dataset [15]. This protocol provides a robust framework for assessing the concordance of any RNA-seq analysis pipeline.

1. Sample Selection and RNA Preparation:

- Use well-characterized reference RNA samples (e.g., MAQCA/Human Brain Reference from the MAQC project).

- Extract total RNA, ensuring high purity (e.g., Nanodrop 260/280 ratio >1.8) and integrity (e.g., RIN >9.0 via Bioanalyzer).

2. Generation of Gold-Standard qPCR Data:

- Design a transcriptome-wide qPCR panel targeting all protein-coding genes.

- Perform qPCR reactions in technical replicates following MIQE guidelines.

- Calculate normalized Cq values for each gene.

3. RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries from the same RNA samples using a standardized kit (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep).

- Sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq/X) to a sufficient depth (e.g., ≥30 million paired-end reads per sample).

4. Data Processing with Multiple Workflows:

- Process raw sequencing reads through several representative workflows:

- Alignment-based (e.g., STAR/HTSeq, Tophat2/Cufflinks)

- Pseudoalignment-based (e.g., Kallisto, Salmon)

- Generate gene-level expression estimates (e.g., TPM, FPKM) for each workflow.

5. Data Alignment and Concordance Analysis:

- Filter genes based on a minimal expression threshold (e.g., >0.1 TPM) in all samples.

- Calculate expression correlation (Pearson R²) between RNA-seq and qPCR expression intensities.

- Calculate fold changes between sample groups (e.g., MAQCA vs. MAQCB) for both platforms.

- Classify genes into five groups based on differential expression status and direction:

- Concordant: Agree on DE status and direction.

- Non-concordant: Disagree on DE status or direction.

- Severely Discordant: Absolute difference in fold change (ΔFC) > 2.

6. Characterization of Discordant Genes:

- Analyze the gene features (e.g., length, exon count, expression level) of the severely discordant subset.

- Perform cross-dataset validation to identify systematic discrepancies.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Transcriptomic Concordance Study

Protocol for Global Validation of a Transcriptomic Study

This protocol, adapted from methodologies developed for microarray global validation, can be applied to assess the overall quality of any transcriptomic experiment [14].

1. Gene Selection for Validation:

- Do NOT select only the top differentially expressed genes. This strategy fails to provide a global assessment and is biased by regression to the mean.

- Implement Random-Stratified Sampling:

- Stratify all genes based on their fold-change magnitude and direction (e.g., up-regulated high-FC, up-regulated low-FC, down-regulated high-FC, down-regulated low-FC).

- Randomly select a representative number of genes (e.g., 10-20) from each stratum.

2. Orthogonal Measurement:

- Measure the expression of the selected genes using an orthogonal method (e.g., qPCR, Nanostring).

- For qPCR, follow MIQE guidelines: use multiple reference genes for normalization, perform technical replicates, and report Cq values and amplification efficiencies.

3. Statistical Assessment of Agreement:

- Calculate the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) between the fold-change measurements from the primary platform (microarray/RNA-seq) and the validation platform.

- Interpret the CCC:

- Precision Component (r): How close the data points are to the best-fit line (Pearson correlation).

- Accuracy Component (C_b): How close the best-fit line is to the identity line (slope=1, intercept=0).

- A high CCC (>0.9) indicates that the validation platform reproduces both the magnitude and direction of fold changes measured by the primary platform.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomic Concordance Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Provides standardized, well-characterized RNA for benchmarking and cross-platform comparisons. | MAQCA (Universal Human Reference RNA), MAQCB (Human Brain Reference RNA) [15] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from cells or tissues. | Qiagen RNeasy, EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit [16] |

| RNA Integrity Assessment | Evaluates RNA quality to ensure only high-quality samples are used. | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA Nano Kit [16] |

| qPCR Reagents & Assays | Provides gold-standard orthogonal validation for gene expression. | TaqMan assays, SYBR Green master mixes [15] |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | Prepares sequencing libraries from RNA samples. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep [16] |

| Microarray Platforms | For hybridization-based whole-transcriptome expression profiling. | Affymetrix GeneChip系列 [16] |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Identifies the most informative genes from high-dimensional data, reducing complexity. | Elephant Herding Optimization (EHO), Harmonic Search (HS) [18] [19] |

The journey from microarray to RNA-seq has transformed not only the technological landscape of transcriptomics but also the philosophical approach to validation. The historical necessity of systematic orthogonal validation for microarrays has evolved into a more nuanced, context-dependent strategy for RNA-seq. While RNA-seq demonstrates superior technical performance in dynamic range, sensitivity, and novel feature detection, its agreement with gold-standard qPCR is not universal. A small but significant subset of genes—particularly those with low expression or subtle fold-changes—may yield non-concordant results.

For the modern researcher, the decision to validate should be guided by experimental context and biological goals. High-quality RNA-seq data with sufficient replication may not require blanket validation, but targeted confirmation remains crucial when conclusions rest on specific, low-abundance, or subtly changing transcripts. As transcriptomic technologies continue to advance, the principles of rigorous benchmarking and appropriate validation will ensure the reliability of biological insights drawn from these powerful tools.

The translation of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) from a research tool into clinical diagnostics hinges on its ability to reliably detect subtle, biologically relevant changes in gene expression. A significant challenge in validating these transcriptomic measurements lies in establishing a trustworthy "ground truth" against which RNA-seq data can be benchmarked. A central thesis in this field explores the distinction between concordant genes, for which expression measurements from RNA-seq and validation methods like RT-qPCR agree, and non-concordant genes, which show inconsistent results between platforms. This guide objectively compares the performance of various RNA-seq analysis workflows, using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data as a foundational ground truth, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based recommendations for their genomic studies.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Benchmarking studies require carefully designed experiments and a clear ground truth to evaluate the performance of different RNA-seq workflows.

Reference Materials and Ground Truth

A robust benchmark relies on well-characterized reference samples. Two sets of reference RNAs have been pivotal:

- MAQC Samples: Established by the MicroArray/Sequencing Quality Control (MAQC) Consortium, these include Universal Human Reference RNA (MAQC-A) from ten cancer cell lines and Human Brain Reference RNA (MAQC-B) from brain tissues of 23 donors [20] [2]. These samples exhibit large biological differences.

- Quartet Project Reference Materials: These are derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family. They feature small, clinically relevant biological differences between samples, making them ideal for assessing the detection of subtle differential expression [20].

The most definitive ground truth for gene expression is provided by whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR assays. This method uses wet-lab validated assays for thousands of protein-coding genes, providing a high-confidence dataset against which RNA-seq derived expression levels and fold-changes can be compared [21] [2].

Benchmarking Methodology

In a typical benchmarking workflow, RNA from reference samples (e.g., MAQC-A and MAQC-B) is sequenced. The resulting reads are then processed through multiple bioinformatics workflows for gene-level quantification [2]. The key steps are as follows:

Parallel to sequencing, the same RNA samples are subjected to whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR to generate the ground truth data. Performance is evaluated by comparing the gene expression values and the fold-changes (e.g., between MAQC-A and MAQC-B) generated by each RNA-seq workflow to those from the RT-qPCR data. Genes are subsequently classified as concordant or non-concordant based on this analysis [2].

Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Workflows

Workflow Accuracy Against qPCR Ground Truth

Multiple studies have systematically compared popular RNA-seq workflows using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data. The table below summarizes the performance of different computational pipelines in quantifying gene expression and fold-changes.

Table 1: Performance of RNA-seq Workflows Benchmarked Against RT-qPCR Data

| Workflow Category | Specific Workflow | Expression Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Fold-Change Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Fraction of Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-based | Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| Alignment-based | STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | - |

| Pseudoalignment | Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% |

| Pseudoalignment | Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | - |

| Transcript-based | Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | - |

Overall, all tested workflows show high correlation with qPCR data for both absolute expression and fold-changes [2]. Alignment-based tools like Tophat-HTSeq showed a slightly lower fraction of non-concordant genes compared to pseudoalignment tools like Salmon [2]. It is noteworthy that a significant proportion of non-concordant genes are consistently identified as outliers across different workflows and datasets, pointing to systematic, technology-specific discrepancies rather than algorithmic errors [2].

Characteristics of Non-Concordant Genes

Non-concordant genes are not random; they share distinct biological and technical features that can alert researchers to potential inaccuracies.

Table 2: Characteristics of Non-Concordant vs. Concordant Genes

| Characteristic | Non-Concordant Genes | Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Typically lower expressed [2] | Higher expressed [2] |

| Gene Structure | Smaller gene size and fewer exons [2] | Larger gene size and more exons [2] |

| Impact on Analysis | Can lead to inaccurate conclusions if not filtered; require careful validation [2] | Provide reliable results for differential expression analysis [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting rigorous RNA-seq benchmarking studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq Benchmarking

| Item | Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|

| MAQC Reference RNA (A & B) | Well-characterized RNA samples with large biological differences, used for initial pipeline validation and cross-platform comparisons [20] [2]. |

| Quartet Project Reference RNA | RNA reference materials with small, clinically relevant biological differences, crucial for assessing performance on subtle differential expression [20]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA transcripts at known concentrations spiked into samples, used to assess technical accuracy, dynamic range, and detection limits of the workflow [20]. |

| Whole-Transcriptome RT-qPCR Assays | Provides the ground truth for gene expression levels and fold-changes against which RNA-seq data is benchmarked [21] [2]. |

| Stranded mRNA Sequencing Kits | Library preparation kits that preserve the strand orientation of transcripts, identified as a factor influencing data quality and accuracy [20]. |

Benchmarking studies firmly establish that while RNA-seq workflows generally show high agreement with RT-qPCR ground truth, a subset of non-concordant genes exists whose expression is quantified inconsistently. These genes are often lower expressed and have specific structural features. For researchers and drug developers, this underscores the necessity of using well-characterized reference materials and orthogonal validation for critical genes, especially when investigating subtle expression changes relevant to disease subtypes or drug responses. A nuanced understanding of concordant and non-concordant genes is fundamental to establishing a reliable ground truth and advancing RNA-seq into robust clinical diagnostics.

How to Measure and Analyze Gene Expression Concordance

Experimental Design for Concordance Studies

Gene expression analysis is fundamental to biological research and clinical applications. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for whole-transcriptome analysis, but its performance is often validated against quantitative PCR (qPCR), long considered the "gold standard" for targeted gene expression quantification [2]. Concordance studies between these platforms are essential to establish the reliability of RNA-seq data, particularly as it moves toward clinical use. The central thesis of this comparison revolves around understanding which genes show consistent expression measurements between platforms (concordant genes) and which do not (non-concordant genes), and the technical and biological factors driving these differences.

Quantitative Comparison of Platform Performance

Multiple studies have systematically compared gene expression measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR, revealing generally high but imperfect concordance.

Table 1: Summary of RNA-seq and qPCR Concordance Metrics from Key Studies

| Study Reference | Correlation Type | Correlation Coefficient Range | Concordant Genes | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAQC/Scientific Reports [2] | Fold-change correlation | R² = 0.927 - 0.934 (across 5 workflows) | ~85% | ~15% |

| MAQC/Scientific Reports [2] | Expression correlation | R² = 0.798 - 0.845 (across 5 workflows) | N/A | N/A |

| HLA Expression Study [10] | Expression correlation (HLA genes) | rho = 0.2 - 0.53 (HLA-A, -B, -C) | N/A | N/A |

The MAQC study benchmarking five RNA-seq workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data found high fold-change correlations (R² = 0.927-0.934) when comparing two distinct reference RNA samples [2]. Approximately 85% of genes showed consistent differential expression status between RNA-seq and qPCR, while about 15% showed inconsistencies. The alignment-based algorithms (Tophat-HTSeq) showed slightly better performance (15.1% non-concordant genes) compared to pseudoaligners (19.4% for Salmon) [2].

For specific challenging gene families like the highly polymorphic HLA genes, correlation between qPCR and RNA-seq expression estimates was only low to moderate (rho = 0.2-0.53) [10], highlighting the particular difficulties in quantifying certain types of genes.

Characteristics of Non-Concordant Genes

Non-concordant genes—those showing significant differences between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements—typically share distinct characteristics:

- Lower expression levels: Non-concordant genes tend to have significantly lower expression levels as measured by qPCR [2] [3]

- Smaller gene size: These genes are typically smaller and have fewer exons [2]

- Technical artifacts: A small but specific set of genes showed inconsistent expression measurements reproducibly identified across independent datasets [2]

Table 2: Characteristics of Concordant vs. Non-Concordant Genes

| Characteristic | Concordant Genes | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Higher | Lower |

| Gene Size | Larger | Smaller |

| Exon Count | More exons | Fewer exons |

| Technical Variance | Lower | Higher |

| Platform Agreement | Consistent across platforms | Method-specific discrepancies |

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Studies

Sample Preparation and Study Design

Robust concordance studies require carefully controlled experimental designs:

- Reference Materials: Well-established reference RNA samples (e.g., MAQCA/Human Reference RNA and MAQCB/Human Brain Reference RNA) should be used to control for biological variability [2]

- Replication: Multiple technical and biological replicates are essential to account for technical noise and biological variation

- RNA Quality: High-quality RNA with minimal degradation is critical; RNA integrity numbers (RIN) >8.0 are typically recommended

- Sample Matching: Ideally, aliquots from the same RNA extraction should be used for both RNA-seq and qPCR analysis to eliminate preparation variability

RNA-Sequencing Methodology

- Library Preparation: Poly-A selection is commonly used for mRNA enrichment, though ribosomal RNA depletion can provide broader transcriptome coverage [4]

- Sequencing Depth: 15-60 million paired-end reads per sample (100bp read length) is generally sufficient for most applications, with diminishing returns at higher depths [3]

- Platform Selection: Illumina platforms remain most common for RNA-seq studies

qPCR Methodology

- Assay Design: Wet-lab validated qPCR assays that detect specific subsets of transcripts contributing proportionally to gene-level Cq-values [2]

- Normalization: Use of multiple reference genes for reliable normalization

- Whole-Transcriptome Coverage: For comprehensive benchmarking, whole-transcriptome qPCR assays covering >18,000 protein-coding genes provide the most complete comparison [2]

Bioinformatic Processing for RNA-Seq

Multiple computational workflows can be employed for RNA-seq data processing:

- Alignment-based workflows: Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq [2]

- Pseudoalignment methods: Kallisto, Salmon [2]

- HLA-specific pipelines: For challenging gene families like HLA, specialized pipelines that account for known HLA diversity in the alignment step are recommended over standard approaches relying on a single reference genome [10]

Visualization of Concordance Testing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a comprehensive RNA-seq and qPCR concordance study:

Factors Influencing Concordance Between Platforms

Biological and Technical Factors

Several key factors significantly impact the level of concordance observed between RNA-seq and qPCR:

- Treatment effect size: Concordance between platforms is linearly correlated with treatment effect size—stronger biological signals show better agreement [3]

- Gene expression abundance: Both technologies show higher variance for lowly expressed genes, but RNA-seq demonstrates improved accuracy for these genes compared to microarrays (as a reference point) [3]

- Biological complexity: Concordance is higher for simple, well-defined biological mechanisms compared to complex endpoints with multiple contributing factors [3]

- Sequence properties: Genes with high polymorphism (e.g., HLA genes) or specific structural characteristics show reduced concordance [10]

Analysis and Computational Factors

- Bioinformatic workflows: Different RNA-seq processing workflows show minimal but statistically significant differences in concordance with qPCR [2]

- Filtering strategies: Application of minimal expression filters (e.g., 0.1 TPM) affects concordance metrics, particularly for low-abundance genes [2]

- Differential expression methods: Multiple DEG detection methods (limma, edgeR, DESeq) show high consistency in determining the number of differentially expressed genes [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Concordance Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Standardized materials for platform comparison | MAQCA (Universal Human Reference RNA), MAQCB (Human Brain Reference RNA) [2] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation | RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen) with DNAse treatment [10] |

| RNA Quality Control Tools | Assessment of RNA integrity | Bioanalyzer with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment |

| Library Preparation Kits | RNA-seq library construction | Poly-A selection kits for mRNA enrichment [4] |

| Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Assays | Comprehensive qPCR validation | Assays covering >18,000 protein-coding genes [2] |

| HLA-Specific Assays | Expression analysis of polymorphic genes | Specialized qPCR assays for HLA-A, -B, -C [10] |

| Normalization Controls | Reference genes for qPCR | Multiple validated reference genes for reliable normalization |

Concordance studies between RNA-seq and qPCR reveal generally high agreement, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent differential expression patterns between platforms. The remaining 15% of non-concordant genes typically exhibit lower expression levels, smaller size, and fewer exons. Successful experimental design for such studies requires careful attention to sample preparation, adequate sequencing depth, appropriate bioinformatic workflows, and validation using whole-transcriptome qPCR assays. Understanding the factors that influence concordance is essential for proper interpretation of gene expression data, particularly as RNA-seq moves toward clinical applications where reliable quantification is critical for patient care and drug development decisions.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, providing an unprecedented detailed view of gene expression landscapes. As the technique has evolved, two distinct computational approaches have emerged for processing the vast amounts of data it generates: traditional alignment-based methods and newer pseudoalignment algorithms. The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their initial handling of sequencing reads. Alignment-based tools like STAR map reads directly to a reference genome, determining their precise genomic origins [22]. In contrast, pseudoalignment tools such as Kallisto perform a lightweight matching of reads to transcripts by examining their k-mer content, bypassing the computationally intensive step of exact alignment [22] [2].

This methodological divergence is particularly significant when evaluated against the gold standard for gene expression validation: quantitative PCR (qPCR). Research has revealed that a specific subset of genes consistently shows discrepancies—termed "non-concordant" genes—between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements [1] [2]. Understanding the performance characteristics of different RNA-seq workflows regarding these genes is crucial for researchers, especially in drug development where accurate gene expression quantification can inform critical decisions.

Workflow Comparison: Fundamental Differences and Mechanisms

Core Algorithmic Principles

The distinction between alignment-based and pseudoalignment methods represents a paradigm shift in how RNA-seq data is processed, with each approach employing fundamentally different strategies to quantify gene expression.

Alignment-Based Methods (e.g., STAR): These tools operate by mapping raw sequencing reads directly to a reference genome through a detailed, base-by-base alignment process [22]. This method identifies the exact genomic coordinates from which each read originated, requiring significant computational resources to handle splice junctions and sequence variations. The output is typically a file containing read counts for each gene, which forms the basis for subsequent expression analysis [22]. The alignment process provides comprehensive information about splice variants and genomic mapping but demands substantial computational time and memory.

Pseudoalignment Methods (e.g., Kallisto): Rather than performing exact alignment, these tools employ a probabilistic approach that breaks reads down into k-mers (short subsequences of length k) and matches them to a pre-built index of transcripts [22] [2]. This strategy determines the likelihood of a read originating from particular transcripts without establishing its precise genomic location. Kallisto specifically generates both transcripts per million (TPM) and estimated counts as output, enabling immediate abundance estimation [22]. This approach offers substantial gains in speed and computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy for standard differential expression analyses.

Comparative Workflow Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how these two approaches process RNA-seq data:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of STAR and Kallisto Workflows

| Feature | STAR (Alignment-Based) | Kallisto (Pseudoalignment) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Direct genome alignment | K-mer matching to transcriptome |

| Computational Speed | Slower, resource-intensive | Faster, lightweight |

| Memory Requirements | High | Moderate |

| Key Output | Read counts per gene | TPM and estimated counts |

| Splice Junction Detection | Excellent for novel junctions | Limited to annotated transcripts |

| Best Application | Discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants | Rapid quantification of known transcripts |

Performance Benchmarking: Concordance with qPCR Data

Experimental Framework for Validation

Robust benchmarking of RNA-seq workflows requires carefully designed validation frameworks that compare computational results with experimentally verified expression data. One comprehensive study established such a framework using the well-characterized MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples from the MAQC-I consortium, processing RNA-seq data through five distinct workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, and Salmon) and comparing the results with wet-lab validated qPCR assays for 18,080 protein-coding genes [2].

The validation process involved several critical steps to ensure meaningful comparisons. First, researchers aligned transcripts detected by qPCR with those considered for RNA-seq quantification, applying consistent filtering thresholds to avoid biases from lowly expressed genes [2]. For expression correlation analysis, normalized RT-qPCR Cq-values were compared against log-transformed RNA-seq expression values. More importantly, for fold change correlation—often the most biologically relevant metric—gene expression fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples were calculated and compared between RNA-seq workflows and qPCR results [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Concordance Rates

The following table summarizes the performance of different RNA-seq workflows when compared against qPCR validation data:

Table 2: Workflow Performance Against qPCR Benchmarking Data

| Workflow | Expression Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Fold Change Correlation (R² with qPCR) | Non-Concordant Genes | Severely Non-Concordant Genes (ΔFC >2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.1% | 1.1% |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% | 1.1% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 16.8% | 1.4% |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 16.5% | 1.3% |

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% | 1.4% |

Data derived from benchmark studies comparing RNA-seq workflows with genome-wide qPCR data [2].

Overall, high concordance was observed between RNA-seq and qPCR data, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent differential expression results between the two technologies [2]. The alignment-based methods (STAR-HTSeq and Tophat-HTSeq) showed slightly lower rates of non-concordant genes compared to pseudoalignment methods, though the differences were generally modest [2].

Critically, the small percentage of severely non-concordant genes (those with fold change differences >2 between methods) showed consistent characteristics across workflows. These genes were typically shorter, had fewer exons, and were expressed at lower levels compared to genes with consistent measurements [1] [2]. This pattern suggests that molecular features rather than workflow choice primarily drive severe discrepancies.

The Non-Concordant Gene Phenomenon

Characteristics of Problematic Genes

The existence of non-concordant genes represents a significant challenge in RNA-seq analysis, particularly for studies relying on accurate quantification of specific gene targets. Research has revealed that these problematic genes are not randomly distributed but share common characteristics that likely contribute to measurement discrepancies.

A comprehensive analysis by Everaert et al. examined over 18,000 protein-coding genes and found that 15-20% showed non-concordant results when comparing RNA-seq and qPCR data [1]. However, the vast majority of these discrepancies (approximately 93%) involved genes with relatively small fold changes lower than 2, with approximately 80% showing fold changes lower than 1.5 [1]. Only about 1.8% of genes demonstrated severe non-concordance, where the two methods yielded differential expression in opposing directions or one method showed differential expression while the other did not [1].

These severely non-concordant genes display distinct molecular profiles. They tend to be shorter in length and lower in expression levels compared to concordant genes [1] [2]. The combination of these features likely contributes to quantification challenges, as shorter transcripts generate fewer sequencing reads per molecule, potentially reducing quantification accuracy, particularly for low-abundance targets.

Decision Framework for Gene-Specific Validation

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for determining when orthogonal validation is necessary based on gene characteristics and research context:

Experimental Design Considerations

Impact of Study-Specific Factors on Workflow Performance

The optimal choice between alignment-based and pseudoalignment methods depends significantly on specific experimental parameters and research objectives. Several key factors should guide this decision:

Transcriptome Completeness: For well-annotated transcriptomes, pseudoalignment methods like Kallisto provide rapid and accurate quantification of known transcripts [22]. However, when working with less characterized organisms or when discovering novel splice junctions is a priority, alignment-based tools like STAR offer significant advantages [22].

Computational Resources: Alignment-based methods typically require substantial computational resources, including significant RAM and processing time, which can be prohibitive for large-scale studies or institutions with limited infrastructure [22]. Pseudoalignment methods offer dramatically faster processing times with more modest hardware requirements.

Sample Size and Sequencing Depth: Kallisto's pseudoalignment approach demonstrates less sensitivity to variations in sequencing depth compared to alignment-based methods, potentially making it more suitable for studies with heterogeneous sequencing depths across samples [22]. For projects with exceptionally high sequencing depth, the additional information captured by full alignment may justify the computational costs.

Research Objectives: If the primary goal is differential expression analysis of known genes, pseudoalignment methods generally provide excellent performance with dramatically reduced computational requirements [22] [2]. Conversely, if identifying novel transcripts, splice variants, or fusion genes is essential, alignment-based approaches remain necessary [22].

Table 3: Essential Resources for RNA-seq Workflow Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-Based Tools | STAR, Tophat2, HISAT2 | Genome alignment and read mapping | Higher computational demands; superior for novel feature discovery |

| Pseudoalignment Tools | Kallisto, Salmon | Rapid transcript quantification | Fast processing; ideal for well-annotated transcriptomes |

| Quantification Packages | HTSeq, featureCounts | Gene-level read counting | Used with alignment-based workflows |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Statistical analysis of expression differences | Choice depends on experimental design and sample size |

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC, fastp | Read quality assessment and preprocessing | Essential for detecting technical issues |

| Reference Databases | Ensembl, GENCODE, RefSeq | Genome and transcriptome references | Version control critical for reproducibility |

| Validation Methods | qPCR, reporter fusions | Orthogonal verification of key findings | Especially important for low-expression or critical result genes |

The comparison between alignment-based and pseudoalignment RNA-seq workflows reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological choice should align with specific research goals and practical constraints. Alignment-based methods like STAR provide comprehensive mapping information essential for discovering novel transcriptional events, while pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto offer exceptional efficiency for quantitative analysis of known transcripts.

Benchmarking against qPCR data demonstrates that both approaches show high overall concordance, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent differential expression patterns between methods [2]. The critical finding that a small subset of genes (approximately 1.8%) shows consistent discrepancies across workflows underscores the importance of understanding gene-specific factors that affect quantification accuracy [1]. These non-concordant genes, characterized by shorter length and lower expression levels, warrant special attention in studies where they feature prominently.

For researchers in drug development and precision medicine, where accurate gene expression quantification directly impacts decision-making, we recommend a hybrid approach: utilizing pseudoalignment methods for initial genome-wide analyses while implementing targeted qPCR validation for key low-abundance genes or those with small but critical fold changes. This strategy balances comprehensive transcriptome assessment with precise quantification of biologically significant targets, ensuring both discovery power and analytical reliability.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technique for validating gene expression data obtained from high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). While RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, qPCR delivers highly sensitive, specific, and reproducible quantification of selected targets, making it the gold standard for confirmation studies [15] [9]. However, the reliability of qPCR data hinges on stringent methodological rigor. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a critical framework to ensure this rigor, promoting transparency, reproducibility, and trust in qPCR results [23] [24].

This guide explores qPCR best practices within the context of validating concordant and non-concordant genes from RNA-seq analyses. We outline experimental protocols, present comparative performance data, and provide actionable strategies for implementing MIQE guidelines to strengthen the conclusions drawn from your gene expression studies.

The MIQE Guidelines: Ensuring Data Credibility

The MIQE guidelines, first published in 2009 and recently updated to version 2.0, represent an international consensus on the minimum information required to publish reproducible and reliable qPCR experiments [23] [24]. Their primary purpose is to provide a cohesive framework that standardizes experimental design, execution, data analysis, and reporting. Despite their widespread recognition—with over 17,000 citations to date—compliance remains patchy, leading to a troubling complacency that undermines data quality [23].

Common failures include poorly documented sample handling, unvalidated assays, assumptions about amplification efficiency, and the use of unverified reference genes for normalization [23]. These are not marginal oversights but fundamental methodological flaws that can lead to exaggerated sensitivity claims in diagnostics and overinterpreted fold-changes in gene expression studies [23]. MIQE 2.0 addresses these deficiencies by offering updated, simplified, and coherent guidance for the entire qPCR workflow, from sample handling to data analysis [23].

Adhering to MIQE is not merely an academic exercise; it has real-world consequences. During the COVID-19 pandemic, variable quality in qPCR assay design and data interpretation undermined confidence in diagnostics [23]. Following MIQE guidelines helps to build a foundation of reliable data that can underpin sound decisions in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and public health policy.

Key MIQE Checklist Items

The following table summarizes core elements of the MIQE checklist that are crucial for RNA-seq validation workflows.

Table 1: Essential MIQE Checklist Items for RNA-seq Validation

| Category | Requirement | Significance for Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Sample & Nucleic Acid Quality | Detailed RNA quantification, integrity assessment (e.g., RIN), and documentation of DNase treatment [23] [10]. | Prevents bias from degraded samples; ensures template quality for both RNA-seq and qPCR [23]. |

| Reverse Transcription | Complete documentation of kit, priming method (oligo-dT, random hexamers, or gene-specific), and reaction conditions [23] [25]. | The reverse transcription step is a major source of variability; detailed reporting is essential for reproducibility [23] [25]. |

| Assay Validation | Primer sequences, concentrations, and amplicon context sequences. Demonstration of primer specificity and PCR amplification efficiency [23] [25]. | Ensures accurate and specific quantification. Efficiency is critical for correct fold-change calculation [23] [26]. |

| Data Analysis & Normalization | Use of stable, validated reference genes, justification of the number of reference genes, and method for Cq determination [23] [26] [9]. | Inappropriate normalization is a primary source of error. Using unstable reference genes invalidates results [23] [9]. |

| Experimental Transparency | Evidence of repeatability (technical replicates) and biological reproducibility. Raw data (e.g., fluorescence curves) must be available [23] [26]. | Allows for independent evaluation of data quality and re-analysis, which is fundamental to the scientific process [23] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for RNA-seq Validation

Validating an RNA-seq dataset with qPCR requires a carefully planned experiment targeting specific genes of interest. The selection of these genes and the design of the qPCR assay are critical steps that directly impact the validity of the conclusions.

Selection of Target Genes for Validation

When validating RNA-seq data, genes are typically selected based on their differential expression profiles. These can be divided into two categories:

- Concordant Genes: Genes identified as differentially expressed by RNA-seq that the researcher aims to confirm with an orthogonal method.

- Non-Concordant Genes: A critical set of genes that may show inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR. One benchmarking study found that while ~85% of genes showed consistent fold-changes between RNA-seq and qPCR, a small but specific set of genes (often smaller, with fewer exons, and lower expression) were prone to method-specific discrepancies [15]. Including such genes in a validation study can help define the limitations of both technologies.

Selection and Assessment of Reference Genes

The stability of reference genes (often erroneously called "housekeeping genes") is a cornerstone of reliable qPCR. Traditionally used genes like ACTB and GAPDH are often unstable under various experimental conditions [9]. Instead, reference genes must be empirically validated for stability in the specific biological system under investigation.

Software tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) can leverage RNA-seq data itself to identify the most stable, highly expressed candidate reference genes [9]. GSV applies filters to transcript-per-million (TPM) values across samples to select genes that are consistently expressed at high levels with low variation, thereby avoiding the pitfall of selecting stable but lowly expressed genes that are unsuitable for qPCR [9].

A Protocol for qPCR Assay Validation

The following workflow outlines the key steps for establishing a MIQE-compliant qPCR assay for RNA-seq validation.

Workflow Steps Explained:

- Select Target & Candidate Reference Genes: Choose concordant and non-concordant genes from RNA-seq data. Use tools like GSV on your TPM data to identify stable, high-expression reference gene candidates [9].

- Design & Synthesize Primers/Probes: Design oligonucleotides following best practices (e.g., amplicon length of 50-150 bp, spanning an exon-exon junction for cDNA). Note: "TaqMan" is a trade name; the scientific term is "hydrolysis probe" [25].

- Check Amplicon Specificity: Verify a single amplicon through melt curve analysis (for intercalating dyes) or sequence verification.

- Run Serial Dilutions for Efficiency Curve: Perform qPCR on a serial dilution (e.g., 1:5) of a pooled cDNA sample to generate a standard curve.

- Calculate PCR Efficiency & R²: The slope of the standard curve is used to calculate PCR efficiency (E) using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1. Ideal efficiency is 90-110%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.990 [23] [26].