Correcting GC Bias in Transcriptomics: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate RNA-Seq Analysis

GC bias, the dependence of sequencing read coverage on guanine-cytosine content, is a major technical artifact that confounds transcriptomics analysis, leading to inaccurate gene expression quantification and differential expression results.

Correcting GC Bias in Transcriptomics: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate RNA-Seq Analysis

Abstract

GC bias, the dependence of sequencing read coverage on guanine-cytosine content, is a major technical artifact that confounds transcriptomics analysis, leading to inaccurate gene expression quantification and differential expression results. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, identify, and correct for GC bias in RNA-Seq data. Covering foundational concepts through advanced validation strategies, we detail the unimodal nature of GC bias affecting both GC-rich and GC-poor regions, explore experimental and computational mitigation methods, and present best practices for troubleshooting and benchmarking. By synthesizing current evidence and multi-center study findings, this guide empowers scientists to achieve more reliable biological interpretations from their transcriptomics data, which is crucial for robust biomarker discovery and clinical translation.

Understanding GC Bias: From Core Concepts to Transcriptomic Impact

Defining GC Bias and Its Unimodal Effect in Sequencing

GC bias is a technical artifact in high-throughput sequencing where the guanine (G) and cytosine (C) content of DNA or RNA fragments influences their representation in sequencing data. This bias manifests as a unimodal relationship between GC content and fragment coverage, meaning both GC-rich and AT-rich (adenine-thymine) fragments are underrepresented, while fragments with moderate GC content are overrepresented [1] [2]. This effect can substantially distort quantitative analyses in transcriptomics, such as differential expression and copy number estimation, making its understanding and correction essential for accurate biological interpretation [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is GC bias and why is it a problem in transcriptomics?

GC bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and GC content found in sequencing data [1]. In transcriptomics, this bias confounds the true biological signal because the measured read count for a gene depends not only on its actual expression level but also on its sequence composition [2]. This can lead to:

- Inaccurate fold-change estimates in differential expression analysis [2].

- False positives or false negatives in tests for differential expression [2].

- Misinterpretation of biological results, as GC content is often correlated with genomic functionality [1].

What does "unimodal effect" mean in the context of GC bias?

The unimodal effect refers to the specific pattern observed in GC bias: read coverage is highest for fragments with an intermediate GC content and drops off for fragments that are either very GC-poor or very GC-rich [1] [2]. This creates a single-peak (unimodal) curve when coverage is plotted against GC content. Empirical evidence suggests this pattern is consistent with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) being a major cause of the bias, as both extremely high and low GC sequences amplify less efficiently [1] [3].

My RNA-seq data shows an unusual GC content distribution. Should I be concerned?

An unusual GC profile does not automatically indicate a problem. It could be due to a set of highly expressed genes with a particular GC content in your specific sample [4]. However, you should investigate further if:

- The distribution differs substantially between sample groups in a differential expression study [5] [2].

- There is a low mapping rate to your target organism, which could point to microbial contamination that also alters the GC profile [4].

- Samples were processed in different batches, labs, or with different library preparation kits, as the GC bias effect is often sample-specific [1] [5] [3]. Normalization methods in tools like DESeq2 or edgeR can account for some technical variability, but severe bias may require explicit correction [4].

Which step of the sequencing workflow introduces the most GC bias?

Library preparation, and particularly PCR amplification, is identified as a dominant source of GC bias [1] [6]. During PCR, fragments with very high or very low GC content are amplified less efficiently, leading to their under-representation in the final sequencing library [1]. Other steps can also contribute, including:

- Fragmentation methods (e.g., enzymatic vs. chemical) [6].

- Adapter ligation efficiency, which can be sequence-dependent [6].

- Priming biases, especially from random hexamers used in cDNA synthesis [2] [6].

- Enzymes used in library kits: For example, Oxford Nanopore's transposase-based (rapid) kits show a stronger coverage bias linked to GC content compared to their ligation-based kits [3].

How can I check my data for GC bias?

A primary method is to visualize the relationship between GC content and read coverage. This typically involves:

- Binning genomic regions (e.g., genes or fixed-size windows) based on their GC content.

- Calculating the average read coverage for each bin.

- Plotting the average coverage against GC content. A unimodal curve, rather than a flat line, indicates the presence of GC bias. Many software packages, such as

deepToolsandEDASeq, can assist with this analysis [2] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Identifying and Diagnosing GC Bias

Follow this workflow to systematically diagnose GC bias in your sequencing data.

Table 1: Key Features of GC Bias in Sequencing Data

| Feature | Description | How to Detect It |

|---|---|---|

| Unimodal Coverage | Read coverage peaks at moderate (~40-60%) GC content and decreases for both high and low GC regions. | Plot average read depth vs. GC content percentage per genomic bin. |

| Sample-Specificity | The exact shape of the GC bias curve can vary between samples, even from the same library. | Compare GC-coverage plots across all samples in the experiment. |

| Technology/Library Dependence | The severity of bias can differ between sequencing platforms and library prep kits. | Compare results from different kits or protocols; ONT rapid kits may show stronger bias than ligation kits [3]. |

| Impact on DE | Can cause false differential expression calls for genes with extreme GC content. | Check if DE genes are enriched for high or low GC content after standard normalization. |

Mitigating and Correcting for GC Bias

Pre-sequencing (Preventative) Measures

- Use PCR-free library protocols where possible, though this is often challenging for low-input samples like cfDNA [6] [7].

- Optimize PCR conditions: Use polymerases known for better performance across GC extremes (e.g., Kapa HiFi) and additives like betaine for GC-rich templates [6].

- Choose library kits carefully: Ligation-based protocols may introduce less bias than transposase-based ones for some technologies [3].

- Maintain high RNA quality: Use high-quality, non-degraded RNA (RIN > 7) to prevent interactions between degradation bias and GC bias [8].

Post-sequencing (Computational) Corrections

Computational methods model and counter the observed bias. They generally work by calculating a correction factor for each fragment or genomic region based on its GC content.

Table 2: Comparison of GC Bias Correction Methodologies

| Method / Tool | Primary Application | Key Principle | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCparagon [7] | Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) | Two-stage algorithm that computes fragment-level weights based on length and GC count, adding them as tags to BAM files. | Designed for the specific length distribution of cfDNA; allows customization of fragment length range. |

| Conditional Quantile Normalization (CQN) [2] | RNA-seq | Incorporates GC-content and gene length effects into a Poisson model using smooth spline functions. | Simultaneously corrects for multiple within-lane biases (GC and length). |

| Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) [9] | RNA-seq (short-read) | Leverages the theoretical Gaussian distribution of GC content in k-mers to model and correct biases without relying on empirical data. | Aims to correct multiple co-existing biases simultaneously. |

| Benjamini & Speed Method [1] [7] | DNA-seq | Produces GC-effect predictions at the base pair level, allowing strand-specific correction. | Informed by the analysis that the full fragment's GC content is the most influential factor. |

| EDASeq [2] | RNA-seq | Provides within-lane gene-level GC-content normalization procedures, to be followed by between-lane normalization. | Offers multiple simple normalization approaches. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for GC Bias Analysis

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Kapa HiFi Polymerase | A PCR enzyme known for robust amplification across sequences with varying GC content. | Reducing bias during library amplification step [6]. |

| Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA and other RNA biotypes, improving sequencing efficiency. | Preparing RNA-seq libraries from total RNA to avoid skewed representation due to abundant rRNA [9] [8]. |

| Spike-in RNAs (e.g., ERCC, SIRV, Sequin) | Synthetic RNA molecules with known sequences and concentrations added to the sample. | Acts as an internal control to monitor technical performance, including GC bias, across samples and protocols [10] [9]. |

| VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | A standardized protocol for constructing RNA-seq libraries, including fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification. | A representative kit used in standardized workflows for transcriptome sequencing [9]. |

| GCparagon Software [7] | A stand-alone tool designed specifically for GC bias correction in cfDNA data on a fragment level. | Correcting GC bias in liquid biopsy sequencing data to improve detection of copy number alterations or nucleosome footprints. |

| EDASeq R/Bioconductor Package [2] | An open-source software package providing functions for exploratory data analysis and normalization of RNA-seq data, including GC correction. | Implementing within-lane GC-content normalization during the initial bioinformatic processing of RNA-seq data. |

Core Concepts: PCR and GC Bias

What is the primary function of PCR in NGS library preparation? PCR is used to amplify the amount of DNA in a library, ensuring there is sufficient material for sequencing. It also incorporates sequencing adapters and sample indices (barcodes) onto the DNA fragments, enabling the sequencing process and multiplexing of samples [11].

How does PCR contribute to GC bias in transcriptomics data? PCR amplification is not always uniform. DNA fragments with extreme GC content (very high or very low) often amplify less efficiently than fragments with moderate GC content [12]. This leads to:

- Under-representation: GC-rich regions can form stable secondary structures that hinder DNA polymerase activity, leading to lower coverage [13] [12].

- Skewed Data: The resulting sequencing data does not accurately represent the original abundance of transcripts, compromising the accuracy of downstream differential expression analysis [12].

What are the downstream impacts of PCR-induced GC bias on transcriptomics research? GC bias can significantly impact the biological interpretation of your data, leading to:

- Inaccurate variant calling, potentially causing both false negatives and false positives [12].

- Compromised detection of copy number variations (CNVs) and other structural variants due to uneven coverage [12].

- Misleading differential expression results in transcriptomics, as coverage differences can be mistaken for true biological changes [12].

PCR Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common PCR-related issues during library prep, their root causes, and proven solutions.

| Observation | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No / Low Amplification [14] [11] | Poor template quality or contaminants [13] [14] | Re-purify template DNA; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over absorbance; ensure 260/280 ratio ~1.8 [14] [11]. |

| Suboptimal reaction conditions [14] | Optimize Mg2+ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [14]; use a hot-start polymerase [13] [14]; test an annealing temperature gradient starting 5°C below primer Tm [14]. | |

| Multiple Bands / Non-specific Products [14] | Primer annealing temperature too low [13] [14] | Increase annealing temperature; optimize stepwise in 1-2°C increments [13]. |

| Excess enzyme or primers [13] | Lower DNA polymerase amount [13]; optimize primer concentration (typically 0.1-1 µM) [13] [14]. | |

| Sequence Errors / Low Fidelity [13] [14] | Low fidelity DNA polymerase [14] | Switch to a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) [14]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP concentrations [13] [14] | Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes [13] [14]. | |

| High Duplicate Read Rate / Amplification Bias [12] [11] | Too many PCR cycles [12] [11] | Reduce the number of amplification cycles [13] [12]; use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish PCR duplicates [12]. |

| Complex template (e.g., high GC-content) [13] [14] | Use a polymerase with high processivity [13]; add a PCR enhancer or co-solvent (e.g., DMSO, GC enhancer) [13] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol 1: Optimizing PCR for GC-Rich Transcripts

This protocol is designed to improve the uniform amplification of GC-rich regions, which are common in gene promoters and other critical genomic areas [12].

- Polymerase Selection: Use a DNA polymerase engineered for high processivity and robustness to inhibitors, often marketed for "difficult" templates [13] [14].

- Master Mix Formulation:

- Thermal Cycling Adjustments:

- Denaturation: Increase the denaturation temperature (e.g., to 98°C) and/or time (e.g., to 30 seconds) to ensure complete separation of stable, GC-rich templates [13].

- Annealing/Eextension: Use a combined annealing/extension step at a higher temperature (e.g., 68-72°C) to prevent secondary structure formation [13].

- Cycles: Use the minimum number of cycles necessary to obtain sufficient yield to minimize bias [13] [12].

Protocol 2: A PCR-Free Library Preparation Workflow

The most effective method to eliminate PCR bias is to avoid it entirely. This is feasible when input DNA is of sufficient quantity and quality [12].

- Input DNA: Start with high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA (recommended amount varies by kit, often > 1μg).

- Fragmentation: Fragment DNA via sonication or enzymatic methods. Mechanical shearing has demonstrated improved coverage uniformity compared to enzymatic methods [12].

- End-Repair & A-Tailing: Perform standard enzymatic steps to prepare fragment ends for adapter ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate double-stranded sequencing adapters directly to the prepared fragments. This is a key step that replaces the PCR amplification of adapters [11].

- Purification: Clean up the ligated library using bead-based purification to remove excess adapters and reaction components. Accurate bead-to-sample ratios are critical to prevent loss of desired fragments [11].

- QC and Sequencing: Quantify the final library using qPCR-based methods and proceed to sequencing. The resulting data will be free from PCR duplicates and amplification bias, providing a more accurate representation of the original sample [12].

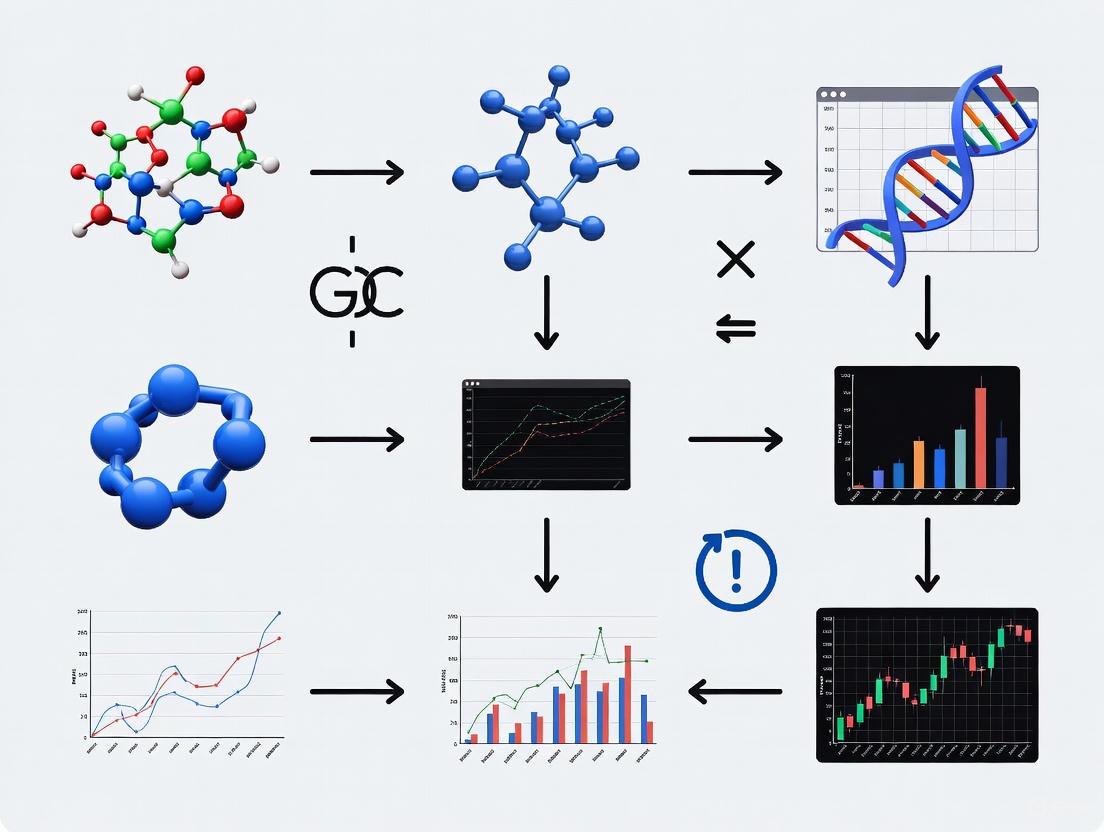

Workflow and Cause-Effect Visualization

PCR Workflow and Bias Introduction Points

Cause and Effect of PCR-Induced Bias

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in PCR | Key Consideration for GC Bias |

|---|---|---|

| High-Processivity DNA Polymerase [13] [14] | Robustly amplifies difficult templates; maintains activity over long targets. | Essential for denaturing and amplifying stable secondary structures in GC-rich regions [13]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, GC Enhancer) [13] [14] | Destabilizes DNA secondary structures; improves polymerase processivity. | Critical for reducing the melting temperature of GC-rich sequences, promoting even amplification [13]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [13] [14] | Remains inactive until a high-temperature activation step. | Prevents nonspecific priming and primer-dimer formation at setup, improving specificity and yield [13] [14]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [12] | Short random nucleotide sequences ligated to each fragment before amplification. | Allows bioinformatic correction for PCR duplicates and amplification bias, crucial for accurate quantification [12]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit [12] | Uses adapter ligation without amplification to create sequencing libraries. | The most effective solution to eliminate PCR bias, but requires higher input DNA [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I identify if GC bias is present in my sequencing data? Use quality control tools like FastQC to visualize the relationship between GC content and read coverage across your genome. A uniform distribution should show a relatively smooth, symmetrical peak. Deviations from this, such as sharp drops in coverage at high or low GC percentages, indicate significant bias [12].

Are there bioinformatic tools to correct for GC bias? Yes, several bioinformatics normalization approaches exist. These algorithms computationally adjust the read depth based on the local GC content of the genome, which can help improve the uniformity of coverage and the accuracy of downstream analyses like variant calling [12].

What is the single most impactful step I can take to reduce PCR bias? The most impactful step is to reduce the number of PCR cycles during library amplification. Every additional cycle exponentially amplifies small, initial biases in amplification efficiency. Use the minimum number of cycles required to obtain sufficient library yield for sequencing [13] [12].

How GC Bias Skews Gene Expression and Quantification

GC bias, the technical artifact where the guanine (G) and cytosine (C) content of a transcript influences its representation in sequencing data, is a significant challenge in transcriptomics. This bias can severely skew gene expression quantification, leading to inaccurate biological interpretations. In sequencing data, the relationship between fragment count and GC content is typically unimodal: both GC-rich fragments and AT-rich fragments are underrepresented [1]. This bias predominantly arises during PCR amplification steps in library preparation, where fragments with extreme GC content amplify less efficiently [1] [12]. Understanding and correcting for this effect is crucial for the reliability of RNA-seq in clinical diagnostics and drug development [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is GC bias and how does it affect my RNA-seq data? GC bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and the GC content of the DNA fragment [1]. It creates a unimodal curve: fragments with extremely high or low GC content have lower coverage than those with moderate GC content [1]. This skews gene expression quantification, as genes with non-optimal GC content will be under-represented, leading to false negatives in differential expression analysis and inaccurate measurement of expression levels [12].

Q2: What are the primary molecular causes of GC bias? Evidence strongly suggests that PCR amplification during library preparation is a dominant cause [1]. GC-rich regions can form stable secondary structures that hinder polymerase processivity, while AT-rich regions may have less stable DNA duplexes, both leading to inefficient amplification [12]. The bias is influenced by the GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced reads [1].

Q3: How can I identify GC bias in my sequencing data? GC bias can be identified using several quality control (QC) tools. FastQC provides graphical reports highlighting deviations in GC content [12]. Picard tools and Qualimap enable detailed assessments of coverage uniformity relative to GC content [12]. Visually, you will observe a non-uniform distribution of coverage when plotted against GC content, forming a characteristic unimodal shape [1].

Q4: Does GC bias only affect RNA-seq, or other sequencing types too? While this guide focuses on transcriptomics, GC bias is a pervasive issue in many high-throughput sequencing assays, including DNA-seq for copy number variation analysis and ChIP-seq [1]. The underlying cause—PCR amplification of fragments with varied GC composition—is common to many library preparation protocols.

Q5: Are some genes more susceptible to GC bias than others? Yes, genes with extreme GC content (either very high or very low) are most affected. For example, genes in promoter-associated CpG islands (which are GC-rich) are often underrepresented due to this bias [12]. This is a critical consideration when studying gene families with inherent sequence composition biases.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inaccurate Gene Expression Quantification Due to GC Bias

- Symptoms: Inconsistent gene expression measurements between replicates; under-representation of genes with very high or very low GC content; poor correlation with qPCR validation data for specific genes [12] [15].

- Root Causes:

- PCR Over-amplification: Excessive number of PCR cycles during library preparation exacerbates the under-representation of extreme-GC fragments [1] [12].

- Suboptimal Fragmentation: Enzymatic fragmentation methods can be susceptible to sequence-dependent biases compared to mechanical methods like sonication [12].

- Incorrect Data Normalization: Using standard normalization methods that do not account for GC content.

- Solutions:

- Wet-Lab Protocol Adjustments:

- Optimize library preparation by reducing the number of PCR cycles [11].

- Use PCR-free library workflows if input DNA is sufficient [12].

- Consider using polymerases engineered for more uniform amplification across different GC contents [12].

- Use mechanical fragmentation (e.g., sonication) which has demonstrated improved coverage uniformity compared to enzymatic methods [12].

- Bioinformatics Corrections:

- Employ normalization algorithms that explicitly adjust read counts based on local GC content [12].

- Utilize advanced bias mitigation frameworks like the Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) framework, which models the natural Gaussian distribution of GC content in transcripts to correct for multiple coexisting biases simultaneously [9].

- Wet-Lab Protocol Adjustments:

Problem 2: Low Sensitivity in Detecting Subtle Differential Expression

- Symptoms: Inability to reliably detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between samples with similar transcriptome profiles (e.g., different disease subtypes or stages); high inter-laboratory variation in DEG lists [15].

- Root Causes: GC bias introduces technical noise that can obscure small, biologically relevant expression differences [15]. The problem is more pronounced than when analyzing samples with large biological differences [15].

- Solutions:

- Implement Rigorous Quality Control: Use reference materials like the Quartet samples, which are designed for benchmarking performance at subtle differential expression levels [15].

- Benchmark Your Pipeline: Calculate metrics like the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on principal component analysis (PCA) of your data and reference samples to gauge your ability to detect subtle expression changes [15].

- Standardize Experimental Protocols: Studies show that factors like mRNA enrichment method and library strandedness are major sources of variation. Adopting best-practice protocols can reduce inter-lab variability [15].

Problem 3: General Workflow for GC Bias Mitigation

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for diagnosing and correcting GC bias in a transcriptomics project.

Quantitative Data on GC Bias Impact

Table 1: Performance Variation in Multi-Center RNA-Seq Studies

This table summarizes key findings from a large-scale benchmarking study across 45 laboratories, highlighting the impact of technical variations, including GC bias, on RNA-seq results [15].

| Metric | Samples with Large Biological Differences (MAQC) | Samples with Subtle Biological Differences (Quartet) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Average: 33.0 (Range: 11.2–45.2) | Average: 19.8 (Range: 0.3–37.6) | Technical noise has a greater relative impact when biological differences are small [15]. |

| Correlation with TaqMan (Protein-Coding Genes) | Average Pearson R: 0.825 | Average Pearson R: 0.876 | Accurate quantification of a broader gene set is more challenging; highlights need for large-scale reference datasets [15]. |

| Primary Sources of Variation | Experimental factors (mRNA enrichment, strandedness) and every step in bioinformatics pipelines [15]. |

Table 2: Common Sequencing Preparation Failures Linked to Bias

This table links common laboratory issues with their potential to introduce or exacerbate GC bias [11].

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Link to GC Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification / PCR | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias [11]. | Primary cause. Excessive cycles preferentially amplify mid-GC fragments [1] [12]. |

| Sample Input / Quality | Low library complexity; shearing bias [11]. | Degraded DNA/RNA and uneven fragmentation can compound under-representation of extreme-GC regions [12]. |

| Fragmentation | Unexpected fragment size distribution [11]. | Enzymatic fragmentation can be sequence-dependent, skewing fragment population before PCR [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol 1: Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) for Bioinformatics Correction

The GSB framework is a theoretical model-based approach that mitigates multiple biases simultaneously by leveraging the natural Gaussian distribution of GC content in transcripts [9].

- k-mer Categorization: Break down the transcript reference sequences into k-mers and categorize them based on their GC content [9].

- Theoretical Model Building: Aggregate the counts of k-mers within each GC-content category. Fit these aggregate counts to a Gaussian distribution to establish a theoretical, unbiased benchmark. The key parameters (mean and standard deviation) are derived from this theoretical model, independent of empirical data [9].

- Empirical Data Processing: Process your empirical sequencing data by similarly categorizing k-mers from the aligned reads by their GC content and aggregating their counts [9].

- Bias Correction: Fit the empirical GC-count aggregates to the Gaussian distribution using the pre-determined parameters from Step 2. The resulting Gaussian-distributed counts serve as unbiased indicators. Use these to adjust the sequencing counts for each k-mer, effectively reducing bias across the entire transcript [9].

Protocol 2: Best-Practice RNA-seq Workflow to Minimize Bias

This protocol summarizes wet-lab and computational best practices compiled from multiple sources [12] [15] [9].

- Library Preparation:

- Use rRNA depletion instead of poly-A selection if possible, as the latter can introduce its own biases [9].

- If PCR is necessary, minimize the number of amplification cycles. Use polymerases known for balanced amplification [12].

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to account for PCR duplicates [12].

- Sequencing:

- Sequence to an adequate depth, as the impact of bias can be more pronounced in low-coverage data.

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC and MultiQC to generate reports on GC distribution [12] [9].

- Trimming: Remove adapters and low-quality bases using tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic [9].

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner like HISAT2 [9].

- Bias Mitigation: Apply a GC-content normalization method or a advanced framework like GSB [9].

- Validation: Where possible, validate key findings using an orthogonal method like qPCR or by leveraging spike-in controls [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for GC Bias-Aware Research

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Relevance to GC Bias |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations spiked into samples. | Provide an external standard to monitor technical accuracy, including GC bias effects, independent of biological variation [15]. |

| Quartet Reference Materials | RNA reference materials derived from a family quartet with well-characterized, subtle expression differences [15]. | Essential for benchmarking pipeline performance and accurately detecting subtle differential expression in the presence of technical noise like GC bias [15]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Library preparation kits that eliminate the PCR amplification step. | Avoids the introduction of PCR-based biases, including GC bias, but requires higher input DNA [12]. |

| Bias-Robust Polymerase | PCR enzymes engineered for uniform amplification efficiency across sequences with varied GC content. | Reduces the under-representation of GC-rich and AT-rich fragments during library amplification [12]. |

| Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit | A kit for removing ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples. | An alternative to poly-A selection for mRNA enrichment; helps avoid 3' bias associated with some poly-A protocols [9]. |

| VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | A standardized commercial kit for RNA-seq library construction. | Using a standardized, widely adopted kit helps ensure reproducibility and reduces protocol-specific variability [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between fragment GC and read GC content? Read GC refers to the proportion of Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) bases only in the sequenced part of a DNA fragment. In contrast, Fragment GC refers to the GC content of the entire original DNA molecule before sequencing, including the parts between the paired-end reads that are never actually sequenced [1].

Why is this distinction critical for my analysis? The GC bias observed in sequencing data (where coverage depends on GC content) is primarily influenced by the full fragment GC, not just the read GC [1]. Using the wrong one for normalization can lead to incomplete correction, leaving substantial bias in your data and confounding downstream analyses like differential expression or copy number variation detection [1] [2] [16].

What is the typical "shape" of GC content bias? The bias is unimodal. This means that both GC-rich fragments and AT-rich fragments (GC-poor) are underrepresented in the sequencing results. The highest coverage is typically observed for fragments with a moderate, intermediate GC content [1] [12].

What is the primary cause of this bias? Empirical evidence strongly suggests that PCR amplification during library preparation is the most important cause of the GC bias. Both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments amplify less efficiently than those with balanced GC content [1] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms and Diagnosis

If you are observing the following issues in your data, incorrect GC bias correction might be the cause:

- In DNA-seq: Unexplained fluctuations in copy number (CN) profiles that correlate with regional GC content [1].

- In RNA-seq: Inaccurate transcript abundance estimates and an increased false discovery rate in differential expression analysis [2] [16].

- General NGS: Persistent uneven coverage across the genome after standard normalization, with systematic drops in coverage in known GC-rich or GC-poor regions [12].

Diagnostic Checklist:

- Plot Your GC-Coverage Curve: Create a plot of fragment coverage versus GC content. If the curve is not unimodal (peaking in the middle), your normalization method may be insufficient [1].

- Check Protocol Details: Determine if your library preparation method is prone to this bias (e.g., PCR-amplified libraries). PCR-free workflows show reduced bias [12].

- Verify Normalization Method: Ensure the bioinformatics tool you are using for GC correction accounts for the full fragment GC content.

Visualizing the Concepts and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts and a general workflow for identifying and correcting for fragment GC bias.

Methodologies for Assessing and Correcting Bias

The table below summarizes key experimental and computational approaches for addressing fragment GC bias.

| Method Category | Description | Key Tools / Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Mitigation | Reducing the bias at the source during library preparation. | PCR-free library workflows [12]; Using polymerases engineered for GC-rich templates [12]; Mechanical fragmentation (sonication) over enzymatic [12]. |

| Computational Correction (DNA-seq) | Modeling the unimodal relationship between fragment GC and coverage, then normalizing the data. | BEADS [1]; Polynomial regression on bin-level counts [2]. |

| Computational Correction (RNA-seq) | Correcting transcript abundance estimates by modeling bias from fragment sequence features. | alpine R/Bioconductor package [16]; Conditional Quantile Normalization (CQN) [2]; GC-content normalization in EDASeq [2] [17]. |

Detailed Protocol: Computational Correction with a Full-Fragment Model

This methodology, as described in Benjamini & Speed (2012) [1], involves:

- Fragment Definition: For paired-end data, use the mapped coordinates of both reads to determine the start, end, and length of the original DNA fragment.

- GC Calculation: For each genomic position, calculate the GC content for every possible fragment that could be observed in the library, considering the actual distribution of fragment lengths.

- Bias Modeling: Model the observed read coverage as a function of the pre-calculated fragment GC content. The relationship is typically fitted with a unimodal curve (e.g., a smooth loess curve or a parametric unimodal function).

- Normalization: Divide the observed read count in a genomic region (or bin) by the predicted count from the GC-bias model. This yields a normalized coverage value that is corrected for fragment GC effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function |

|---|---|

| PCR-free Library Prep Kits | Eliminates the primary source of GC bias by avoiding amplification, though they require higher input DNA [12]. |

| Bias-Correcting Software | Tools like alpine (for RNA-seq) and BEADS (for DNA-seq) implement models that use full fragment GC for normalization [1] [16]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes ligated to each fragment before PCR. They help distinguish technical duplicates (from PCR) from biological duplicates, mitigating one aspect of amplification bias [12]. |

| Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNAs or DNAs with known concentrations and a range of GC contents. They are added to the sample to provide an external standard for quantifying and correcting technical biases [10]. |

| Quality Control Tools | Software like FastQC, Picard, and MultiQC help visualize GC coverage trends and duplication rates, providing the first alert to potential bias issues [12] [18]. |

What is GC Bias in Sequencing?

GC bias refers to the uneven sequencing coverage of genomic regions due to variations in their guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotide content. In both DNA and RNA sequencing, regions with very high or very low GC content often show reduced read coverage compared to regions with balanced GC content. This technical artifact can lead to inaccurate measurements of gene expression in transcriptomics (RNA-seq) or false conclusions in metagenomic abundance estimates [19] [12]. The bias arises because the probability of a DNA or RNA fragment being successfully amplified and sequenced is not constant, but depends on its sequence composition [20].

Critically, the shape and severity of GC bias are not consistent; they are sample-specific, meaning they can change from one experiment to another, even when using the same sequencing platform [6] [20]. This variability is a major source of systematic error that must be understood and corrected for reliable biological interpretation.

FAQs on GC Bias Variability

1. Why does the GC bias profile differ between my sequencing runs?

The GC bias profile is highly sensitive to specific laboratory conditions and choices during library preparation. The core reason for variability is that multiple experimental factors, which differ between runs, can introduce and modulate the bias. Key factors include [6] [19] [20]:

- Library Preparation Kit and Protocol: Different commercial kits and methods (e.g., PCR-free vs. PCR-amplified) have varying susceptibilities to GC bias.

- PCR Amplification: The number of amplification cycles and the type of DNA polymerase used are major contributors. PCR can stochastically introduce biases, as it amplifies different molecules with unequal probabilities [6].

- Sequencing Platform: Different platforms (e.g., Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq, HiSeq, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) exhibit distinct and characteristic GC bias profiles [19] [21].

- Sample Storage and RNA Extraction Method: For RNA-seq, the method of sample preservation (e.g., frozen vs. FFPE) and RNA isolation can influence RNA integrity and introduce biases that interact with GC effects [6].

2. How can the same protocol produce different GC biases in different labs?

Even with an identical written protocol, inter-laboratory variation in execution introduces significant variability. A large-scale, real-world benchmarking study of RNA-seq across 45 laboratories found that subtle differences in experimental execution are a primary source of variation. Factors such as the specific mRNA enrichment method (e.g., poly-A selection vs. rRNA depletion) and the strandedness of the library can profoundly influence results, including GC-related biases [15]. This means that operator technique, reagent batches, and equipment calibration can all contribute to the unique GC bias signature of a dataset.

3. What is the molecular basis for GC bias affecting certain fragments?

The bias is driven by the physical properties of DNA and RNA fragments during the library preparation process:

- GC-Rich Regions: Sequences with high GC content form stable secondary structures (e.g., hairpins) that can hinder the binding of primers and polymerases, leading to inefficient amplification during PCR [12].

- GC-Poor Regions: Sequences with low GC content have less stable DNA duplexes, which can also result in inefficient amplification [12].

- Fragment GC Content: Evidence suggests that it is the GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced read ends, that most strongly influences its representation. The relationship is typically unimodal, meaning both GC-rich and GC-poor fragments are under-represented compared to those with an optimal, intermediate GC content [20].

4. Does GC bias impact transcriptomics analysis differently than genomic studies?

Yes, the impact and correction strategies can differ. In genomics (e.g., DNA-seq for copy number variation), GC bias directly causes uneven coverage across the genome, creating gaps or false positives. In transcriptomics (RNA-seq), the bias can lead to systematic errors in transcript abundance estimation. For example, isoforms of the same gene that differ in a high-GC exon can be mis-quantified, as the high-GC region may have artificially low coverage, skewing expression estimates between isoforms [22]. This can result in hundreds of false positives in differential expression analysis [22].

Comparison of Sequencing Platforms and GC Bias

The following table summarizes how different sequencing technologies and library preparation methods compare in their susceptibility to GC bias, based on empirical studies.

Table 1: GC Bias Profiles Across Sequencing Platforms and Methods

| Platform / Method | GC Bias Profile | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq | High GC Bias [19] | Major GC biases; severe under-coverage outside 45-65% GC range; GC-poor regions (e.g., 30% GC) can have >10-fold less coverage [19]. |

| Illumina HiSeq | Moderate GC Bias [19] | Exhibits GC bias, but with a profile distinct from MiSeq/NextSeq [19]. |

| Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) | Moderate GC Bias [19] | Similar GC bias profile to HiSeq [19]. |

| Oxford Nanopore | Minimal to No GC Bias [19] [21] | PCR-free workflows are not afflicted by GC bias, making it advantageous for unbiased coverage [19] [21]. |

| PCR-free Library Prep | Greatly Reduced Bias [19] [12] | Eliminates the major contributor to bias; requires high input DNA [19] [12]. |

| PCR-based Library Prep | Variable, often High Bias [6] [23] | Bias level depends on polymerase, cycle number, and additives [6] [23]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Methods for Mitigating GC Bias

| Reagent / Method | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Kapa HiFi Polymerase | An enzyme engineered for more balanced amplification of sequences with extreme GC content, outperforming others like Phusion [6]. |

| PCR Additives (Betaine, TMAC) | Chemical additives that help denature stable secondary structures in GC-rich regions, promoting more uniform amplification [6] [19]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes ligated to each molecule before PCR amplification, allowing bioinformatic identification and removal of PCR duplicates [12]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | For RNA-seq, using rRNA depletion (e.g., Ribo-off kit) instead of poly-A selection can help avoid 3'-end capture bias associated with random hexamer priming [6] [24]. |

| Mechanical Fragmentation | Using sonication or other physical methods for DNA shearing demonstrates improved coverage uniformity compared to enzymatic fragmentation, which can be sequence-biased [12]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations and a range of GC contents, used to track and correct for technical biases, including GC effects, within a sample [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing GC Bias

Protocol 1: Visualizing and Quantifying GC Bias in Your Data

This protocol allows you to assess the level of GC bias in your own sequencing dataset.

- Read Alignment: Map your sequencing reads to the reference genome using a standard aligner (e.g., BWA for DNA-seq, HISAT2 for RNA-seq).

- Genome Binning: Divide the reference genome into consecutive, non-overlapping windows (bins). A common size is 1 kb, but this can be adjusted.

- Calculate Metrics: For each bin, compute:

- GC Content: The proportion of G and C bases in the bin's reference sequence.

- Read Coverage: The average number of reads mapping to that bin (normalized by the total number of mapped reads).

- Data Visualization: Create a scatter plot with GC content on the x-axis and normalized read coverage on the y-axis.

- Curve Fitting: Fit a smooth curve (e.g., a Loess curve) or a unimodal function to the data points. The resulting curve is your sample-specific GC bias profile [20]. A flat line indicates no bias, while a curved line shows the dependence of coverage on GC.

Diagram: The Workflow for GC Bias Assessment

Protocol 2: A Multi-Center Study Design for Systemic Bias Evaluation

Large-scale consortium projects have established robust methods for evaluating technical variability, including GC bias.

- Reference Materials: Use well-characterized reference samples. For transcriptomics, the Quartet project provides RNA reference materials from a family quartet, designed to have subtle differential expression, making them sensitive to technical noise [15]. The MAQC project samples are also widely used.

- Spike-In Controls: Spiked-in synthetic RNAs (like ERCC controls) at known ratios into your samples prior to library preparation. These provide an external "ground truth" for evaluating quantification accuracy across different GC contents [15].

- Distributed Sequencing: Distribute the same set of reference materials to multiple participating laboratories. Each lab should prepare libraries and sequence the samples using their own standard protocols and platforms.

- Centralized Analysis: Perform a centralized bioinformatic analysis to quantify the inter-laboratory variation. Key metrics include:

- Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

- Accuracy of absolute gene expression measurements against TaqMan reference datasets.

- Accuracy of detecting differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [15].

- Factor Analysis: Statistically correlate the observed variations (e.g., in GC bias profiles) with the documented experimental factors (e.g., library kit, platform, operator) from each lab to identify the most influential sources of bias [15].

Key Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: My data shows a strong GC bias, with poor coverage of both AT-rich and GC-rich regions.

Solutions:

- Wet-Lab: For future experiments, switch to a PCR-free library preparation protocol if input material allows [19] [12]. If PCR is necessary, reduce the number of cycles and use a high-fidelity polymerase optimized for GC-rich regions (e.g., Kapa HiFi) with PCR additives like betaine [6].

- Bioinformatic: Apply a GC-content normalization algorithm to your existing data. Methods exist in tools like

alpinefor RNA-seq, which models fragment GC content to correct abundance estimates and can drastically reduce false positives in differential expression analysis [22]. Other tools likeEDASeqalso provide robust within-lane GC normalization [2].

Problem: I am getting inconsistent results in a multi-site study.

Solutions:

- Standardize Protocols: Implement a single, detailed library preparation protocol across all sites, including specific kit recommendations and PCR cycle numbers.

- Use Common Controls: Provide all sites with the same batch of reference materials (e.g., Quartet or MAQC samples) and spike-in controls (ERCCs) to be included in every sequencing run. This allows for post-hoc batch effect correction and performance monitoring [15].

- Centralized Processing: Process all raw sequencing data through a single, standardized bioinformatics pipeline to avoid introducing additional variation from analysis choices [15].

GC Bias Correction Strategies: From Laboratory to Code

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is GC bias in transcriptomics and why is it a problem? GC bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and GC content found in sequencing data. This technical artifact results in both GC-rich fragments and AT-rich fragments being underrepresented in sequencing results, which can dominate the biological signal of interest and lead to inaccurate interpretation of gene expression data [1].

How does PCR contribute to GC bias? PCR is considered the most important cause of GC bias. During library preparation, the polymerase chain reaction amplifies DNA fragments with varying efficiency based on their GC content, leading to uneven coverage across the genome that doesn't reflect true biological abundance [1].

What are the main advantages of PCR-free workflows? PCR-free workflows eliminate amplification bias, provide more uniform coverage across regions with varying GC content, reduce duplicate reads, and offer more accurate representation of true biological abundance. These benefits are particularly valuable for quantitative applications like transcriptomics and copy number variation analysis [1] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common GC Bias Issues and Solutions

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uneven coverage in GC-rich or AT-rich regions | PCR amplification bias during library prep | Implement PCR-free library preparation methods; Use GC-balanced kits [1] [11] |

| Inaccurate gene expression measurements | Overamplification of specific GC content fragments | Reduce PCR cycles; Optimize amplification conditions; Switch to PCR-free protocols [1] |

| Difficulties in CNV detection | GC bias confounding copy number signal | Apply computational GC bias correction (e.g., DRAGEN GC bias correction) [25] |

| Low library complexity | Overamplification in early PCR cycles | Limit PCR cycles; Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs); Optimize input DNA quality [11] |

PCR Optimization Strategies to Minimize Bias

| Factor | Problem | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle Number | Overamplification introduces bias | Use minimal cycles needed for adequate library yield [11] |

| Polymerase Type | Standard polymerases have GC bias | Use high-fidelity or GC-enhanced polymerases [26] |

| Buffer Composition | Suboptimal Mg++ concentration affects fidelity | Adjust Mg++ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [26] |

| Annealing Temperature | Mispriming causes spurious products | Optimize annealing temperature using gradient PCR [26] |

| Template Quality | Degraded DNA increases amplification bias | Use high-quality, intact DNA/RNA templates [26] [11] |

Enzyme Engineering Solutions for GC Bias

| Approach | Mechanism | Application in GC Bias Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Directed Evolution | Laboratory evolution through mutation and screening | Develop polymerases with improved amplification efficiency across GC content [27] |

| Enzyme Immobilization | Stabilizing enzymes on solid supports | Enhance polymerase thermal stability and processivity [27] |

| Rational Design | Structure-based protein engineering | Engineer polymerase variants with reduced GC preference [27] |

| Computer-Aided Design | AI and simulation-guided optimization | Predict and design enzyme mutants with unbiased amplification [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Assessing GC Bias in Your Data

- Sequence your samples using standard library preparation protocols

- Align reads to reference genome using appropriate aligners (e.g., BWA)

- Calculate GC content and coverage in genomic bins

- Plot relationship between GC content and read coverage

- Identify characteristic unimodal curve where both high-GC and low-GC regions show underrepresentation [1]

Implementing PCR-Free Workflows

- Start with high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA (≥100 ng)

- Fragment DNA using mechanical shearing (e.g., sonication)

- Perform end-repair and A-tailing following standard protocols

- Ligate adapters without amplification steps

- Clean up library and quantify using fluorometric methods

- Sequence with appropriate coverage to account for lack of amplification [11]

Computational GC Bias Correction

For experiments where PCR-free workflows aren't feasible, implement computational correction:

The DRAGEN GC bias correction module processes aligned reads to generate GC-corrected counts, which are recommended for downstream analysis when working with whole genome sequencing data [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity amplification | Reduces sequence errors; better for GC-rich templates [26] |

| PreCR Repair Mix | Template damage repair | Fixes damaged DNA template before amplification [26] |

| GC Enhancer Additives | Improve GC-rich amplification | Specialized buffers for difficult templates [26] |

| Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit | Purification | Removes inhibitors that affect amplification [26] |

| DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform | Computational GC correction | Software-based bias correction for existing data [25] |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enhanced stability | Improved reusability and industrial applicability [27] |

| Directed Evolution Platforms | Enzyme optimization | OrthoRep and PACE systems for polymerase improvement [27] |

Within-Lane Normalization Approaches for RNA-Seq Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is within-lane normalization, and why is it specifically needed for RNA-Seq data? Within-lane normalization corrects for gene-specific technical biases that occur within a single sequencing lane. It is essential because raw RNA-Seq read counts are influenced not only by biological expression but also by technical factors like gene length and GC-content. Without this correction, comparing expression levels between different genes within the same sample is biased, as longer genes naturally produce more reads, and genes with extreme GC content (either very high or very low) can be under-represented [28] [29].

2. How does GC-content bias specifically affect my differential expression analysis? GC-content bias is not constant across samples; it is lane-specific. This means the bias does not cancel out when you compare samples. For a given gene, one sample might have a lower read count not because of true biological down-regulation, but due to that specific lane's bias against the gene's GC content. This can lead to false positives or false negatives in your differential expression results [28] [30].

3. My data is normalized with TPM. Is that sufficient for cross-sample comparison? No. While TPM is a useful within-sample normalization method that corrects for sequencing depth and gene length, it is not sufficient for reliable cross-sample comparisons. TPM does not fully account for library composition bias, which occurs when a few highly expressed genes in one sample consume a large fraction of the sequencing reads, skewing the apparent expression of all other genes. For cross-sample comparisons, such as differential expression, you should use methods designed for between-sample normalization (e.g., those in DESeq2 or edgeR) after within-lane corrections [31] [29].

4. What are the signs that my dataset might have a significant GC-content bias? You can detect potential GC-content bias by plotting gene-level read counts (or log-counts) against their GC-content for each lane. A clear non-random pattern, such as a curve where both GC-rich and GC-poor genes have lower counts, indicates a strong bias. Tools like the EDASeq package in R provide functions for this kind of exploratory data analysis [28] [30].

5. Are there methods that can correct for multiple biases at once? Yes, newer computational frameworks are being developed to handle co-existing biases simultaneously. For example, the Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) framework leverages the natural Gaussian distribution of GC content in transcripts to model and correct for multiple biases, including GC bias, fragmentation bias, and library preparation bias, in a single integrated process [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Persistent GC-Bias After Standard Normalization

Problem: Even after applying common normalization methods (e.g., TMM), you observe a clear relationship between GC-content and read counts in your diagnostic plots.

Solutions:

- Apply a dedicated GC-content normalization method: Use the functions available in the EDASeq R package. The package implements within-lane gene-level GC-content normalization procedures that can be followed by a between-lane normalization step [28] [30].

- Consider the GSB Framework: For a more comprehensive solution, explore the GSB framework, which is designed to mitigate multiple biases jointly based on GC-content distribution [9].

- Verify with Spike-Ins: If available, use external RNA controls (spike-ins) with a range of GC contents to independently monitor and validate the performance of your GC-bias correction [9].

Issue 2: Non-Uniform Read Coverage Along Transcripts

Problem: Reads are not distributed evenly across exons, which can make standard count-based summarization (like summing all reads per gene) unreliable.

Solutions:

- Try the "maxcounts" approach: Instead of summing all reads mapped to a feature (totcounts), quantify its expression as the maximum per-base coverage (maxcounts). This method has been shown to be less biased by non-uniform read distribution and less sensitive to variations in alignment quality [32].

- Check library preparation protocols: Be aware that the choice of fragmentation method (e.g., sonication vs. enzymatic) and reverse transcription primers (e.g., random hexamers vs. poly-dT) can influence coverage uniformity. Optimizing these wet-lab steps can reduce the bias at the source [12] [32].

Comparison of Normalization Methods and Their Characteristics

The table below summarizes key within-sample normalization methods and their properties to help you choose the right one for your analysis goals.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Corrects for Sequencing Depth | Corrects for Gene Length | Primary Use Case | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Counts Per Million | Yes | No | Simple scaling for sequencing depth. | Fails to account for gene length and RNA composition. Not for cross-sample DE [33] [29]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads | Yes | Yes | Comparing gene expression within a single sample [29]. | Values for a gene can differ between samples even if true expression is the same. Not for cross-sample comparison [31] [29]. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Yes | Yes | Comparing gene expression within a single sample [29]. | More comparable between samples than RPKM/FPKM, but still not suitable for DE analysis as it doesn't fully correct for composition bias [31] [33]. |

| GC-content (EDASeq) | - | Via subsequent between-lane method | Via subsequent between-lane method | Correcting sample-specific GC-content bias before differential expression. | Requires a two-step process (within-lane then between-lane) [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for GC-Bias Assessment and Correction

Protocol 1: Implementing GC-Content Normalization with EDASeq

This protocol outlines the steps for performing within-lane GC-content normalization using the EDASeq package in R, as derived from the foundational paper [28] [30].

- Input Data Preparation: Prepare a matrix of raw gene-level read counts for your experiment.

- GC Content Calculation: Compute the GC-content for each gene based on its nucleotide sequence.

- Within-Lane Normalization: Apply one of the three within-lane GC-normalization approaches implemented in EDASeq:

- Loess Robust Smoothing: Fits a loess curve to the relationship between read counts and GC-content within each lane and corrects counts based on this fit.

- Global-Scaling: Adjusts counts based on the global mean of counts for genes with similar GC-content.

- Full-Quantile Normalization: Makes the distribution of read counts conditional on GC-content the same across all genes.

- Between-Lane Normalization: Following the within-lane correction, apply a between-lane normalization method (e.g., TMM from edgeR or the median-of-ratios from DESeq2) to account for differences in sequencing depth across lanes.

- Output: The final output is a normalized count matrix suitable for downstream differential expression analysis.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this process:

Diagram Title: GC-content normalization workflow with EDASeq.

Protocol 2: The maxcounts Quantification Approach

This protocol describes an alternative method for quantifying gene expression that is less sensitive to non-uniform read coverage [32].

- Alignment and Post-Processing: Map reads to a reference genome or transcriptome and perform standard post-alignment QC, including filtering out poorly aligned reads and multireads.

- Compute Per-Base Coverage: For each exon or single-isoform transcript, calculate the number of reads covering every single position (p) in its sequence. This gives you a vector of "positional counts" (N^p).

- Determine maxcounts: For each feature, define its expression value as the maximum value in its vector of positional counts:

maxcounts = max(N^p). - Between-Sample Normalization: Normalize the maxcounts values across samples to correct for library size differences using a method like TMM [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for GC-Bias Mitigation Experiments

| Item | Function in Context | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | A standardized protocol for library preparation used in studies developing bias mitigation methods [9]. | Used in the validation of the GSB framework. |

| Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA, enriching for other RNA types and improving sequencing sensitivity [9]. | Critical for reducing dominant rRNA signals that can worsen composition bias. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Exogenous RNA controls with known sequences and concentrations. | Mixed with sample RNA to monitor technical accuracy and bias in the sequencing workflow [32]. |

| Custom RNA Spike-Ins (Circular) | Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides used for internal calibration and benchmarking of bias correction methods [9]. | Used to validate the GSB framework's performance. |

| EDASeq R/Bioconductor Package | Provides a suite of functions for the exploratory data analysis and normalization of RNA-Seq data, including GC-content normalization [28] [30]. | Implements the within-lane methods described in Protocol 1. |

| Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) Framework | A novel computational tool that uses the theoretical distribution of GC content to correct for multiple biases simultaneously [9]. | A tool for advanced, integrated bias correction. |

Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind the Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) framework?

The GSB framework is a novel bias mitigation method that leverages the natural Gaussian (normal) distribution of Guanine and Cytosine (GC) content found in RNA transcripts. Instead of treating GC content as a source of bias, GSB uses it as a theoretical foundation to build a robust correction model. It operates on the principle that k-mer counts from a transcript, when grouped by their GC content, should inherently follow a Gaussian distribution. By comparing empirical sequencing data against this theoretical benchmark, the framework can simultaneously identify and correct for multiple technical biases [9] [34].

Q2: How does the GSB framework differ from traditional bias correction methods in RNA-seq?

Traditional methods are often empirical, meaning they rely on the observed (and already biased) sequencing data to estimate and correct for biases one at a time. In contrast, the GSB framework is theoretical and simultaneous [9]. The key differences are summarized below:

| Feature | Traditional Methods | GSB Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Empirical, using biased data for correction [9] | Theoretical, using a known GC distribution as a benchmark [9] |

| Bias Handling | Corrects biases individually and sequentially [9] | Corrects multiple co-existing biases simultaneously [9] |

| Foundation | Relies on observed data flaws [9] | Relies on pre-determined parameters (mean, standard deviation) of GC content [9] |

| Model | Various statistical models for single biases (e.g., GC, positional) [9] | A single Gaussian distribution model for k-mers grouped by GC content [9] |

Q3: What specific biases does the GSB framework address?

The framework is designed to mitigate a range of common RNA-seq biases, including [9]:

- GC bias: The dependence between read coverage and the GC content of fragments.

- Fragmentation or degradation bias: Uneven survival of RNA fragments based on their position within the transcript.

- Library preparation bias: Introduced by factors like hexamer priming preferences and PCR amplification.

- Mapping bias: Arising from specific characteristics of RNA molecules during alignment.

Q4: What are the key software tools used in implementing the GSB pipeline?

A standard data analysis pipeline for GSB incorporates several established bioinformatics tools for pre- and post-processing. Key software includes [9]:

- FastQC (v0.11.8): For initial quality control checks of raw sequence data.

- Cutadapt (v2.10) & Trimmomatic (v0.39): For trimming adapter sequences and removing low-quality bases.

- HISAT2 (v2.2.1): For aligning sequenced reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38).

- Samtools (v1.7): For post-alignment processing and file management.

- RSeQC package: For comprehensive quality control of RNA-seq data.

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Diagnostic Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Bias Correction | Incorrectly pre-determined parameters (mean, standard deviation) for the theoretical GC distribution [9]. | Recalculate the GC distribution parameters from a validated reference transcriptome. Ensure the reference is appropriate for your organism and sample type. |

| Low library complexity or quality [11]. | Check RNA integrity (RIN > 8) and library profile using a BioAnalyzer. Use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of absorbance alone [11]. | |

| High Technical Variation | Inefficient rRNA depletion, leading to skewed representation [9]. | Validate the efficiency of the rRNA depletion kit (e.g., Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit) using a BioAnalyzer trace [9]. |

| PCR over-amplification artifacts [11]. | Optimize the number of PCR cycles during library amplification to minimize duplicates and bias. Re-amplify from leftover ligation product if yield is low [11]. | |

| Data Integration Failures | Inconsistent genome builds or annotation files between alignment and k-mer analysis [35]. | Ensure all steps use the same genome assembly (e.g., GRCh38.p14) and annotation source (e.g., Ensembl). Check for inconsistencies in chromosome naming [35]. |

| Adapter Contamination | Inefficient adapter ligation or cleanup during library prep [11]. | Inspect the FastQC report for adapter content. Re-trim raw reads with Cutadapt/Trimmomatic. Optimize adapter-to-insert molar ratios in ligation [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Key Steps for GSB Implementation

The following workflow outlines the critical steps for applying the GSB framework, from sample preparation to computational analysis.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract high-quality total RNA (e.g., using RNAiso Plus kit) and verify integrity with a BioAnalyzer [9].

- Deplete ribosomal RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit) to enrich for coding and non-coding RNAs of interest [9].

- Prepare the RNA-seq library using a standardized protocol (e.g., VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit). This involves RNA fragmentation, cDNA synthesis with hexamer priming, end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [9].

- Sequence the library on an Illumina platform to generate high-quality short reads [9].

Computational Data Processing:

- Perform quality control on raw sequencing reads using FastQC [9].

- Trim adapters and remove low-quality bases using Cutadapt and Trimmomatic [9].

- Align the cleaned reads to the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using a splice-aware aligner like HISAT2 [9].

- Process alignment files (BAM) using Samtools and perform additional RNA-seq QC with the RSeQC package [9].

GSB Bias Correction Core:

- Theoretical Benchmark: From the reference transcriptome, organize all possible k-mers based on their GC content. The aggregate counts for each GC-content category will form a Gaussian distribution. Pre-determine the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of this distribution. These are the key theoretical parameters [9].

- Empirical Data Processing: Similarly, from the aligned sequencing data, extract k-mers along the transcripts, group them by their GC content, and aggregate their observed counts [9].

- Self-Benchmarking and Correction: Fit the empirical GC-count aggregates to a Gaussian distribution using the pre-determined theoretical parameters (μ, σ). The fitted Gaussian curve represents the unbiased expected counts for each GC category. Use these expected values to calculate correction factors and systematically reduce bias at targeted positions across all transcripts [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | A standardized protocol for constructing high-quality RNA-seq libraries, covering fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and adapter ligation [9]. | Used in the GSB study for preparing libraries from HEK293T cells and colorectal samples [9]. |

| Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit | Efficiently removes ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples, enriching for mRNA and other non-rRNA species to improve detection sensitivity [9]. | Specifically used to profile non-rRNA molecules in the GSB study [9]. |

| RNAiso Plus Reagent | A monophasic reagent for the effective isolation of high-quality total RNA from cells and tissues [9]. | Used for total RNA isolation from HEK293T cells in the GSB protocol [9]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides of known sequence and quantity used to monitor technical performance and potential biases throughout the workflow [9]. | Used in the GSB validation process to generate circular RNA spike-ins [9]. |

| DMEM High Glucose Media | Cell culture medium for maintaining mammalian cell lines, such as HEK293T, under optimal conditions prior to RNA extraction [9]. | Used for culturing HEK293T cells in the GSB experimental validation [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core algorithmic difference between Salmon and Kallisto that influences their GC bias correction capabilities? Salmon and Kallisto both use rapid, alignment-free quantification but employ different core algorithms. Kallisto uses pseudoalignment with a de Bruijn graph to determine transcript compatibility [36]. In contrast, Salmon uses quasi-mapping, which tracks the position and orientation of mapped fragments, providing additional information that feeds into its rich, sample-specific bias models [37] [36]. This foundational difference allows Salmon to incorporate a broader set of bias models, including explicit fragment GC content bias correction, which is a key differentiator [37].

Q2: Under what experimental conditions is Salmon's GC bias correction most critical? Salmon's GC bias correction provides the most significant advantage in datasets where fragment GC content has a strong and variable influence on sequencing coverage across samples. This is particularly important in differential expression (DE) analysis when the condition of interest is confounded with GC bias, such as when comparing samples from different sequencing batches or libraries prepared with different protocols [37] [38]. In such cases, Salmon's model can markedly reduce false positive rates and increase the sensitivity of DE detection [37].

Q3: Can Kallisto correct for GC bias? While Kallisto's primary focus is not on GC bias correction, it does include basic sequence-specific bias correction [36]. However, it lacks the comprehensive, sample-specific fragment-GC bias model that is a feature of Salmon [37] [36]. For experiments where GC bias is a major concern, Salmon is generally the recommended tool between the two.

Q4: How does the role of EDASeq differ from that of Salmon and Kallisto? Salmon and Kallisto are quantification tools that estimate transcript abundance from raw RNA-seq reads. EDASeq, on the other hand, is a normalization package typically used downstream of quantification. It operates on a matrix of gene or transcript counts (often obtained from tools like Salmon or Kallisto) to correct for various technical biases, including GC content, as part of the data preparation for differential expression analysis [39]. Therefore, they function at different stages of the analysis workflow.

Q5: Is there a significant accuracy difference between Salmon and Kallisto in practice? While original publications highlighted specific scenarios where Salmon's bias correction improved accuracy [37], independent benchmarks and user experiences often show that the abundance estimates from the two tools are highly correlated and frequently lead to similar biological conclusions in standard differential expression analyses [38] [40]. The greatest performance differences are typically observed in simulations or real data with strong, confounded technical biases [37] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Inter-Replicate Concordance in Differential Expression Analysis

Problem: Your differential expression analysis results in high false discovery rates or poor agreement between biological replicates, and you suspect GC bias is a contributing factor.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Visualize GC Bias: Use tools like

multiQCto check for correlations between fragment GC content and read coverage across your samples. A strong dependency indicates GC bias. - Inspect Method Logs: Ensure that the bias correction flags were successfully enabled and executed by checking the tool's output logs.

Solutions:

- For Salmon: Rerun quantification with the

--gcBiasflag enabled. This activates the fragment GC content bias model, which learns a sample-specific correction during online inference [37] [41]. - For Kallisto: While Kallisto lacks a dedicated GC bias model, ensure that the basic sequence bias correction is enabled with the

--biasflag. - Post-Quantification with EDASeq: If quantification is complete, use the

withinLaneNormalizationfunction in EDASeq to correct the count matrix for GC content effects after importing quantifications (e.g., viatximport).

Issue 2: Handling of Short-Read and Long-Read Data

Problem: You are working with long-read sequencing data (e.g., from Oxford Nanopore or PacBio) and are unsure about the best quantification strategy for GC-aware analysis.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Confirm the sequencing technology used in your experiment.

- Check the error profile and read length of your data.

Solutions:

- Salmon and Kallisto were primarily designed for short-read RNA-seq data [37] [36].

- For long-read data, consider specialized tools like lr-kallisto, an adaptation of the kallisto method optimized for the higher error rates and different error profiles of long-read technologies [42]. The benchmarking indicates lr-kallisto provides accurate quantification for long-read datasets [42].

Issue 3: Integration with Downstream Differential Expression Tools

Problem: You have quantified transcript abundances with GC bias correction but are unsure how to properly prepare this data for differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Confirm the output format of your quantification tool (e.g.,

quant.sffrom Salmon). - Verify that you are using the correct import function to bring abundance estimates into R/Bioconductor.

Solutions:

- Best Practice: Do not use TPM or FPKM values directly for DE analysis. These normalized counts are not suitable for variance-stabilizing methods like DESeq2, which require estimated counts that are not scaled for transcript length [38].

- Recommended Pipeline:

- Run Salmon with

--gcBiasand--seqBiasto get bias-corrected estimates. - Use the

tximportR package to import thequant.sffiles. When importing for use with DESeq2, settxOut = FALSEto obtain gene-level summarized estimated counts ortxOut = TRUEto work with transcript-level counts [36] [38]. - Pass the imported counts directly to DESeq2 or edgeR. These tools have built-in normalization procedures (e.g., median-of-ratios in DESeq2, TMM in edgeR) that account for sequencing depth and library composition, and should be applied to the estimated counts [33].

- Run Salmon with

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Benchmarking GC Bias Correction Performance

This protocol outlines a procedure to evaluate the effectiveness of GC bias correction in quantification tools, based on principles from benchmark studies [37] [40].

1. Experimental Design:

- Data Source: Use a publicly available dataset with known GC bias issues, or generate simulated data where the ground truth abundance is known. The SEQC and GEUVADIS datasets have been used for this purpose [37].

- Comparison Groups: Process the same dataset with different tool configurations (e.g., Salmon with and without

--gcBias, and Kallisto with--bias).

2. Computational Processing:

- Quantification:

- Salmon: Run with

--validateMappings --seqBias --gcBias. - Salmon (no GC bias): Run with

--validateMappings --seqBiasbut omit--gcBias. - Kallisto: Run with

--bias.

- Salmon: Run with

- Indexing: Use a consistent, decoy-aware transcriptome index for all runs [41].

3. Outcome Measures:

- Accuracy against ground truth: Calculate the correlation (Pearson/Spearman) and mean absolute relative difference (MARD) between estimated abundances and known true abundances [37] [43].