Decoding Cell Identity: A Comparative Analysis of Histone Modification Patterns Across Cell Types

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how histone modification patterns diverge across distinct cell types, establishing a critical link between the epigenetic landscape and cellular identity and function.

Decoding Cell Identity: A Comparative Analysis of Histone Modification Patterns Across Cell Types

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how histone modification patterns diverge across distinct cell types, establishing a critical link between the epigenetic landscape and cellular identity and function. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational principles of key modifications like methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation, and their cell-type-specific roles. It further reviews advanced methodological frameworks, including stacked ChromHMM models and single-cell epigenomic techniques, for cross-cell-type comparison. The content addresses crucial troubleshooting considerations for technical variation and data integration, and validates findings through disease-specific case studies in metabolic disorders, azoospermia, and skeletal degeneration. By synthesizing current research and technologies, this review serves as a guide for exploiting histone modification patterns in understanding disease mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

The Histone Code: Foundational Principles and Cell-Type-Specific Landscapes

Core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) serve as fundamental structural components of chromatin, forming the nucleosome core around which DNA is wrapped [1] [2]. These histones undergo numerous post-translational modifications (PTMs) on their N-terminal tails and globular domains, creating a complex "histone code" that dynamically regulates gene expression and DNA-templated processes without altering the underlying DNA sequence [3] [2]. These covalent modifications—including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and newer discoveries like lactylation and crotonylation—fundamentally influence chromatin structure by altering histone-DNA interactions or serving as docking sites for reader proteins that influence transcriptional activity [1] [3]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications, along with their writers, readers, and erasers, enables precise spatiotemporal control of genomic functions including transcription, replication, and repair [2] [4]. This overview examines major histone PTMs, their functional consequences, and the advanced methodologies enabling their study, providing a foundation for comparing histone modification patterns across cell types in both physiological and disease contexts.

Core Histone Proteins: Structural and Functional Organization

The nucleosome, the fundamental repeating unit of chromatin, consists of an octamer containing two copies of each core histone (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) around which 147 base pairs of DNA are wrapped [2]. These evolutionarily conserved proteins feature flexible N-terminal "tails" that protrude from the nucleosomal core and are particularly enriched in residues susceptible to PTMs [1] [3]. A fifth histone, H1, functions as a linker histone that binds to DNA between nucleosome cores, facilitating higher-order chromatin compaction [5]. The core histones share a common structural motif known as the "histone fold" domain, which mediates histone-histone and histone-DNA interactions through dimer formation [2]. Beyond their architectural role, core histones serve as signaling platforms that integrate cellular information through their modification status, thereby influencing DNA accessibility and functional genomic output across diverse biological contexts [2].

Major Histone Post-Translational Modifications

Classical Modifications: Methylation, Acetylation, and Phosphorylation

Table 1: Classical Histone Post-Translational Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Modification Type | Representative Sites | General Function | Associated Enzymes | Genomic Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation | H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, H3K79, H4K20 | Gene activation or repression depending on site and methylation state | KMTs (e.g., EZH2, SETDB1), PRMTs, KDMs (e.g., LSD1) | Promoters, enhancers, gene bodies |

| Acetylation | H3K9, H3K14, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H4K16 | Chromatin relaxation and transcriptional activation | HATs (e.g., p300, HBO1), HDACs | Active promoters and enhancers |

| Phosphorylation | H3S10, H3S28, H2AXS139 | Chromatin condensation, cell signaling, DNA damage response | Kinases, phosphatases | Mitotic chromatin, DNA break sites |

Histone methylation occurs primarily on lysine and arginine residues and can result in mono-, di-, or tri-methyl states for lysine, adding considerable regulatory complexity [3]. This modification exerts contrasting effects depending on the specific site modified; for instance, H3K4me3 is strongly associated with active promoters, while H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 demarcate constitutive and facultative heterochromatin, respectively [6] [2]. Histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and demethylases (HDMs) dynamically regulate methylation states, with their dysregulation frequently observed in human cancers [3].

Histone acetylation, one of the most extensively studied PTMs, neutralizes the positive charge of lysine residues, reducing histone-DNA affinity and promoting chromatin decompaction [3]. This modification is universally associated with transcriptional activation and is dynamically regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs) [3]. The H3K27ac mark specifically distinguishes active enhancers from their poised counterparts marked by H3K4me1 alone [4].

Histone phosphorylation participates in diverse cellular processes, including chromosome condensation during mitosis (H3S10ph, H3S28ph) and DNA damage response (H2AXS139ph, known as γH2AX) [3]. This modification often exhibits crosstalk with other PTMs, creating interdependent signaling networks that integrate extracellular and intracellular cues [2].

Emerging Acylation Modifications: From Lactylation to Crotonylation

Table 2: Novel Histone Acylation Modifications and Their Proposed Functions

| Modification Type | Histone Sites | Metabolic Links | Proposed Functions | Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactylation | H3K9, H3K18, H3K27, H3K56 | Lactate metabolism | Gene activation in macrophages, metabolic memory | Cancer progression, chemoresistance |

| Crotonylation | H3K9, H3K18, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8 | Short-chain fatty acid metabolism | Spermatogenesis, transcriptional activation | Male infertility |

| Succinylation | H3K9, H3K18, H3K79, H4K5, H4K12 | TCA cycle intermediate | Chromatin organization, energy stress response | Metabolic diseases |

| β-hydroxybutyrylation | H3K9, H3K18, H3K27, H4K8 | Ketone body metabolism | Starvation-induced gene regulation | Metabolic adaptation |

Recent advances in mass spectrometry have uncovered numerous novel histone acylations that extend beyond classical acetylation [1] [5]. These modifications, including lactylation, crotonylation, succinylation, and β-hydroxybutyrylation, directly link cellular metabolism to epigenetic regulation by utilizing metabolic intermediates as modification substrates [1] [3]. For instance, histone lactylation depends on lactate availability and has been implicated in tumor progression and chemoresistance in cancers such as clear cell renal cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer [5]. Similarly, histone crotonylation has been specifically detected in spermatogenic cells, suggesting specialized roles in male germ cell development [1] [3]. The expanding repertoire of histone modifications underscores the remarkable complexity of the histone code and its integration of metabolic and environmental signals.

Advanced Methodologies for Histone PTM Analysis

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Mass spectrometry has emerged as the preferred analytical method for comprehensive histone PTM profiling due to its ability to precisely identify modification sites, quantify abundance, and discover novel modifications [5]. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) platforms enable systematic mapping of PTM dynamics, with specialized sample preparation protocols addressing the unique challenges posed by histone basicity and modification density [1] [5]. The recently developed HiP-Frag bioinformatics workflow integrates closed, open, and detailed mass offset searches to expand histone PTM analysis, leading to the identification of 60 previously unreported marks on core histones and 13 on linker histones [5]. This unrestrictive search strategy overcomes limitations of traditional database-dependent approaches, which typically focus on common modifications due to computational constraints [5]. For quantification, stable isotope labeling techniques coupled with MS enable precise measurement of PTM stoichiometry across experimental conditions, providing critical insights into dynamic epigenetic regulation [1].

Sequencing-Based Epigenomic Mapping

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) remains the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications, though it traditionally requires large cell inputs [6]. Recent methodological innovations have dramatically improved the sensitivity and resolution of these approaches. The TACIT (target chromatin indexing and tagmentation) method enables genome-coverage single-cell profiling of histone modifications, revealing unprecedented heterogeneity in epigenetic states during development and disease [7]. In mouse early embryos, TACIT has been used to profile seven histone modifications across 3,749 individual cells, capturing dynamic reprogramming from zygote to blastocyst stages [7]. For combinatorial analysis, CoTACIT allows simultaneous profiling of multiple histone modifications in the same single cell through sequential rounds of antibody binding and tagmentation [7]. These advances are complemented by epigenome editing approaches that program specific chromatin modifications to precise genomic loci using dCas9-effector fusions, enabling causal inference between PTMs and transcriptional outcomes [4].

Single-Cell Multiomics and Computational Integration

The integration of single-cell epigenomic profiles with transcriptomic data represents a powerful strategy for deciphering functional relationships between histone modifications and gene expression [7]. Such multiomic approaches have revealed that histone modification heterogeneity emerges as early as the two-cell stage in mouse embryos, with H3K27ac profiles exhibiting particularly pronounced variation that may prime subsequent lineage decisions [7]. Computational methods for analyzing these datasets include unsupervised clustering, trajectory inference, and machine learning models that predict cellular states or chronological age based on histone modification patterns [6]. For instance, histone mark-based age predictors achieve accuracy comparable to DNA methylation clocks, with H3K4me3 models reaching a median absolute error of 4.31 years in human tissue samples [6] [8]. These predictive models leverage age-related epigenetic trends, including decreased repressive marks (H3K9me3, H3K27me3) and increased variability of all histone modifications during aging [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone PTM Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27ac, Anti-H3K9me3, Anti-H3K27me3 | Immunodetection in ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, immunofluorescence | Validation of specificity crucial; recommend citations from ENCODE |

| Chromatin-Modifying Enzymes | p300/CD, Prdm9/CD, Ezh2/FL, Ring1b/CD | Epigenome editing via dCas9 fusion systems | Catalytic domains preferred over full-length to minimize confounding effects |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Stable isotope-labeled histone analogs, Propionic anhydride-d10 | Quantitative PTM analysis, chemical derivatization | Enable precise stoichiometry measurements |

| Single-Cell Profiling Systems | TACIT, CoTACIT, PAT-tagmentation | Genome-wide histone modification mapping at single-cell resolution | High sequencing depth required (>200,000 non-duplicated reads/cell) |

| Bioinformatics Tools | HiP-Frag, Seurat, AUCell | PTM identification, single-cell data analysis, pathway enrichment | Open-search strategies enable novel PTM discovery |

Histone PTMs in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of histone PTMs constitutes a hallmark of numerous human diseases, particularly cancer and metabolic disorders [1] [3]. In cancer, abnormal expression of histone-modifying enzymes frequently drives oncogenic gene expression programs; for instance, EZH2 (which catalyzes H3K27me3) and SMYD3 (H3K4 methyltransferase) are overexpressed in multiple cancer types, including liver, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas [3]. Metabolic diseases exhibit distinct histone modification landscapes, with studies demonstrating that high-fat diets in mouse models induce specific PTM patterns that disrupt metabolic homeostasis [1]. In male infertility, particularly non-obstructive azoospermia, aberrant histone modifications in testicular cell subpopulations—including elevated HDAC2 expression—impair spermatogenesis [9]. These disease associations have prompted development of therapeutic agents targeting histone-modifying enzymes, with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) representing the most clinically advanced epigenetic drugs [3]. Additional compounds targeting HMTs, HDMs, and HATs are in various preclinical and clinical development stages, offering promising avenues for epigenetic therapy [1] [3].

The predictive potential of histone modifications extends beyond disease diagnosis to biological aging. Histone mark-based "clocks" accurately predict human chronological age across diverse tissues, with performance comparable to established DNA methylation clocks [6] [8]. These predictors reveal conserved age-related trends, including loss of heterochromatin marks (H3K9me3, H3K27me3) and increased epigenetic drift characterized by elevated variance in all histone modification signals [6]. Notably, models trained on one histone modification can predict age using data from another mark, suggesting shared epigenetic information across the histone code [6]. This pan-histone predictability underscores the degenerate nature of age-related epigenetic information and highlights the potential of histone modifications as robust biomarkers of physiological aging and disease risk.

Core histone proteins and their diverse PTMs constitute a sophisticated epigenetic regulatory system that integrates genetic, metabolic, and environmental signals to shape chromatin structure and function. The comparative analysis of histone modification patterns across cell types reveals both conserved principles and context-specific adaptations of this regulatory code. While certain modifications exhibit consistent associations with transcriptional states (e.g., H3K4me3 with active promoters), their functional impact can be significantly modulated by cellular context, underlying DNA sequence, and combinatorial interactions with other epigenetic marks [4]. Future research directions include comprehensive mapping of histone PTM patterns across human cell types and disease states, elucidating the metabolic regulation of novel acylations, and developing more specific epigenetic therapeutics. The continued refinement of single-cell multiomics and precision epigenome editing technologies will further accelerate our understanding of how histone modification patterns establish, maintain, and transition cellular states in health and disease.

Within the eukaryotic nucleus, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, a complex structure whose accessibility is dynamically regulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) to histone proteins [10]. These chemical modifications form a sophisticated "histone code" that extends the information potential of the genetic code itself, enabling precise control of gene expression without altering DNA sequence [3] [11]. Among the numerous identified histone PTMs, methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation represent three of the most extensively studied and functionally significant modifications. These mechanisms operate by either directly altering chromatin architecture or by serving as docking sites for non-histone proteins that execute downstream functions [12]. Understanding how these modifications collectively influence chromatin state is fundamental to advancing research in comparative epigenomics and developing novel therapeutic strategies for human diseases, including cancer and metabolic disorders [3] [1].

Core Mechanisms of Action

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, functional consequences, and enzymatic regulators of the three major histone modifications.

| Feature | Histone Methylation | Histone Acetylation | Histone Phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Addition of methyl groups to lysine (mono-, di-, tri-) or arginine residues [13] [14] | Addition of acetyl groups to lysine residues [13] [14] | Addition of phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues [13] [11] |

| Charge Alteration | None [13] | Neutralizes positive charge, reducing affinity for DNA [13] [14] | Adds negative charge [11] |

| Primary Enzymes | Histone Methyltransferases (HMTs), e.g., EZH2, SETDB1 [3] | Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs), e.g., HBO1 complex [3] | Kinases [11] |

| Removal Enzymes | Histone Demethylases (HDMs), e.g., LSD1, JMJC family [3] [13] | Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) [3] [13] | Phosphatases [13] |

| General Chromatin Outcome | Context-dependent (activation or repression) [13] | Promotes open chromatin (euchromatin) [13] [14] | Promotes chromatin relaxation; key for condensation during mitosis [13] |

| Specific Examples | H3K4me3: Active promoters [15] [13]H3K27me3: Repressed promoters (Polycomb) [13] [11]H3K9me3: Constitutive heterochromatin [13] [11] | H3K9ac/H3K27ac: Active enhancers/promoters [13] [14]H4K16ac: Chromatin folding [11] | H3S10ph: Mitosis [13]γH2AX (S139): DNA damage response [13] [11] |

Visualizing the Core Mechanisms

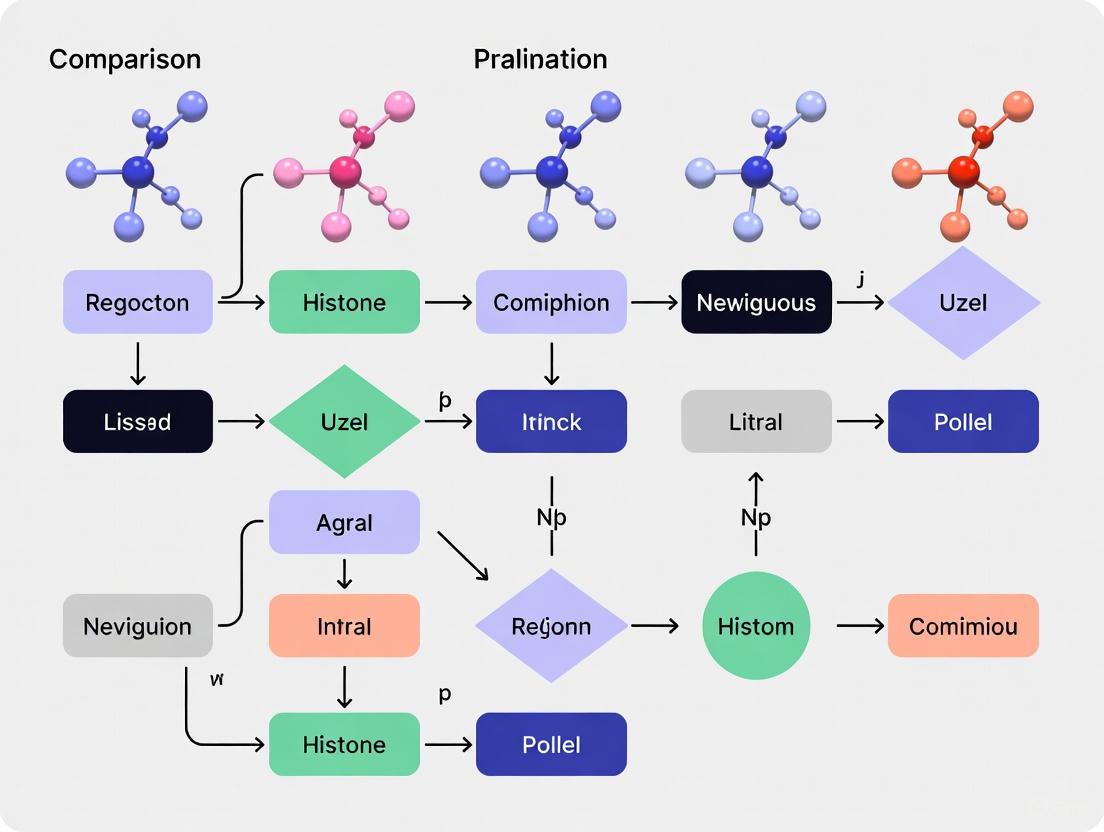

The following diagram illustrates how these three modifications work at the nucleosome level to influence chromatin state.

Comparative Analysis of Modification Patterns Across Cell Types

A core objective in modern epigenetics is comparing histone modification landscapes (the "histone code") across different cell types. These patterns are cell-type-specific and persist through the cell cycle, forming a chromosomal bar code that helps maintain cellular identity [16]. The table below summarizes key comparative data from foundational studies.

| Modification | Pattern Consistency Across Cell Cycle | Inter-Cell Type Variation | Genomic Distribution | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Highly consistent from G1 to M phase [16] | Distinct sub-band patterns in HeLa vs. lymphoblastoid cells [16] | Sharp peaks at transcriptional start sites (TSS) [15] [13] | Highly predictive of active gene promoters [15] |

| H3K9ac | Highly consistent from G1 to M phase [16] | Distinct sub-band patterns in HeLa vs. lymphoblastoid cells [16] | Sharp peaks at TSS and enhancers [15] [13] | Marks active enhancers and promoters [13] [14] |

| H3K27me3 | Consistent through cell cycle but re-established more slowly post-replication [16] | Patterns differ between cell types [16] | Broad domains across silenced gene promoters [13] [16] | Associated with facultative heterochromatin and developmental gene silencing [13] [11] |

| H4ac | Not specified | Not specified | Widespread distribution, less tightly focused at TSS [15] | General association with active chromatin [15] |

Key Experimental Methodologies

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the cornerstone method for mapping histone modifications across the genome. The detailed protocol and associated workflow are essential for generating comparable data across different cell types and experimental conditions.

Detailed ChIP-seq Protocol

- Cross-linking and Cell Lysis: Cells are fixed with formaldehyde to covalently link histones to DNA, preserving in vivo interactions. The chromatin is then isolated and fragmented, typically using sonication or enzymatic digestion with Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase), to sizes of 200-500 bp [15] [16].

- Immunoprecipitation: The fragmented chromatin is incubated with a highly specific antibody against the histone modification of interest (e.g., anti-H3K4me3). Antibody-bound complexes are then isolated using beads coated with Protein A/G [13].

- Reversal of Cross-linking and DNA Purification: The immunoprecipitated complexes are treated to reverse the cross-links, and proteins are degraded. The resulting purified DNA fragments represent the genomic regions associated with the target histone mark [15].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The purified DNA is used to construct a sequencing library, which is then subjected to high-throughput sequencing [15].

- Data Analysis: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome. Enriched regions ("peaks") are identified by comparing the ChIP sample to a control (input DNA), revealing the genomic locations of the histone modification [15].

ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs critical reagents and tools required for experimental research in histone modification biology.

| Research Tool | Function and Application | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Essential for ChIP-seq to immunoprecipitate specific histone modifications [13] [16]. | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27ac, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-γH2AX. Specificity validation is critical. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Chemical probes to inhibit writers or erasers of histone marks; used for functional studies and therapeutic development [3] [11]. | HDAC inhibitors (Vorinostat), LSD1 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors. Many are in clinical trials [3] [11]. |

| Modified Nucleosomes | Defined biochemical substrates for in vitro assays to study enzyme kinetics or reader domain specificity [11]. | Recombinant nucleosomes with site-specific modifications (e.g., H3K4me3); used in platforms like EpiCypher's Captify [11]. |

| Cell Lines | Model systems for comparing cell-type-specific histone modification patterns [15] [16]. | HeLa (cervical cancer), GM06990 (lymphoblastoid), K562 (chronic myeloid leukemia) [15] [16]. |

Methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation constitute a fundamental triad of histone modifications that work in concert to regulate chromatin state and gene expression. Their mechanisms—ranging from direct charge neutralization to sophisticated recruitment of protein complexes—enable a nuanced and dynamic control system. The persistence of cell-type-specific modification patterns through the cell cycle underscores their role as a stable epigenetic blueprint. The advancement of this field relies on robust comparative methodologies like ChIP-seq and a growing toolkit of specific reagents and inhibitors. As research progresses, particularly in mapping modifications across diverse cell types and disease states, the understanding of this complex regulatory language will continue to deepen, unlocking new avenues for targeted epigenetic therapies.

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, whose fundamental unit is the nucleosome—an octamer of core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) around which DNA is wrapped [13]. The N-terminal tails of these histones are susceptible to post-translational modifications (PTMs) that constitute a critical epigenetic layer regulating gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [17]. These modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation, form the basis of the "histone code" that dictates the transcriptional state of genomic regions [13] [18]. Among the numerous documented histone PTMs, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 have emerged as particularly crucial regulators of cell fate, differentiation, and disease. These marks function as dynamic switches that establish permissive or repressive chromatin states, thereby controlling access to genetic information [19]. This comparison guide examines the defining characteristics, functional outcomes, and experimental profiling of these key histone modifications within the context of comparative studies across cell types.

Functional Classification and Comparative Profiles

Histone modifications H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 serve distinct functional roles in gene regulation, with H3K4me3 and H3K27ac associated with permissive chromatin and H3K27me3 linked to repression. Permissive marks facilitate transcription through chromatin loosening or transcription factor recruitment, while repressive marks promote chromatin compaction and inhibit transcription machinery binding [13]. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these modifications.

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Key Histone Modifications

| Feature | H3K4me3 | H3K27ac | H3K27me3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Role | Permissive/Active [13] | Permissive/Active [13] | Repressive [13] |

| Primary Genomic Location | Promoters, Transcription Start Sites (TSS) [13] [17] | Enhancers, Promoters [13] | Promoters in gene-rich regions [13] |

| Associated Chromatin State | Euchromatin [6] | Euchromatin [6] | Facultative Heterochromatin [6] |

| Effect on Transcription | Activation [13] | Activation [13] | Silencing [13] |

| Writer Enzymes | KMT2F/G (SETD1A/B) complexes [17] | p300/CBP [19] | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [20] |

| Eraser Enzymes | KDM5 family (e.g., JARID1A) [13] | HDAC1, HDAC2 [19] | KDM6 family (e.g., UTX) [13] |

| Reader Proteins | TAF3 subunit of TFIID [17] | Bromodomain-containing proteins [19] | Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) [20] |

These modifications exhibit distinct genomic distribution patterns relative to gene features. H3K4me3 is highly enriched at promoter regions immediately surrounding transcription start sites, typically forming sharp peaks [17]. H3K27ac marks both active enhancers and promoters, distinguishing active regulatory elements from their poised or inactive counterparts [13]. In contrast, H3K27me3 is found at promoters of developmentally regulated genes, maintaining them in a transcriptionally silent but reversible state [13] [20].

Table 2: Association with Gene Features and Dynamic Properties

| Property | H3K4me3 | H3K27ac | H3K27me3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancer Association | Rare (H3K4me1 primarily marks enhancers) [13] | Primary mark of active enhancers [13] | Not typically associated with enhancers |

| Stability / Heritability | Relatively stable but requires ongoing maintenance [13] | Dynamic, rapidly altered by signaling events [20] | Heritable through cell divisions (epigenetic memory) [20] |

| Relationship to Gene Expression | Correlates with transcriptional potential [17] | Strong correlation with active transcription [21] | Inverse correlation with transcription [13] |

| Role in Disease | Aberrant in cancer, broad domains metastatic potential [17] | Super-enhancer dysregulation in cancer [17] | Dysregulation in developmental disorders, cancer [20] |

| Cell Type Specificity | Relatively consistent across cell types | Highly cell-type specific at enhancers [7] | Cell-type specific repression programs |

Experimental Profiling and Data Interpretation

Core Methodologies for Genome-Wide Mapping

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) remains the gold standard method for genome-wide profiling of histone modifications [13]. This technique involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, chromatin fragmentation, antibody-mediated immunoprecipitation of specific histone marks, and high-throughput sequencing to identify genomic locations [22]. Key advancements include Cut&Run-seq, which offers higher sensitivity with lower input requirements [20], and TACIT (Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation), enabling genome-coverage single-cell profiling of histone modifications [7]. For integrative analyses, CoTACIT permits simultaneous profiling of multiple histone modifications in the same single cell [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3 (#39159, Active Motif) [22] | Target-specific immunoprecipitation for ChIP-seq/Cut&Run; validation via Western blot |

| Anti-H3K27ac (ab4729, Abcam) [22] | Marks active enhancers and promoters; critical for super-enhancer identification | |

| Anti-H3K27me3 (07-449, Millipore) [22] | Identifies Polycomb-silenced genomic regions | |

| Histone Modifying Enzymes | KMT2F/G (SETD1A/B) complexes [17] | Writer enzymes for H3K4me3 deposition; study mechanistic basis of mark establishment |

| p300/CBP histone acetyltransferases [19] | Writer enzymes for H3K27ac; link signaling pathways to epigenetic changes | |

| PRC2 complex (EZH2 catalytic subunit) [20] | Writer enzyme for H3K27me3; target for therapeutic inhibition | |

| Chemical Inhibitors | HDAC inhibitors (e.g., SAHA) [19] | Erase H3K27ac; study acetylation dynamics and therapeutic applications |

| EZH2 inhibitors (e.g., GSK126) [20] | Reduce H3K27me3; cancer therapeutic and research tool | |

| Cell Lines | HeLa cells [20] | Model for IFNγ-induced transcriptional memory studies |

| PSAPP mice [22] | Alzheimer's disease model for studying histone modifications in neurological disorders | |

| Mouse ES cells [7] | Study epigenetic regulation in development and differentiation |

Interplay and Coordination in Chromatin Regulation

H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 do not function in isolation but exhibit complex interdependencies that define chromatin states. H3K4me3 and H3K27ac frequently co-occur at active promoters, creating a permissive environment for transcription initiation [17]. In contrast, the coexistence of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 at certain promoters creates "bivalent domains," which are particularly important in embryonic stem cells for maintaining genes in a poised state—transcriptionally silent but primed for activation upon differentiation [13]. During cellular reprogramming and differentiation, these marks demonstrate dynamic reciprocity; for instance, loss of H3K27me3 at specific genomic loci often accompanies the acquisition of H3K27ac during gene activation [20].

Recent single-cell epigenomics reveals that the coordinated behavior of these marks underpins cellular heterogeneity. In mouse pre-implantation development, H3K27ac profiles exhibit marked heterogeneity as early as the two-cell stage, preceding other modifications and potentially priming cells for subsequent lineage specification [7]. This highlights how the relative abundance and genomic distribution of these marks contribute to epigenetic cell fate decisions.

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

Dysregulation of histone modification landscapes is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in human diseases, particularly cancer and neurological disorders. In cancer, genome-wide redistribution of these marks occurs, with broad H3K4me3 domains appearing at oncogenes and tumor suppressors, potentially increasing metastatic potential [17]. In Alzheimer's disease, sex-specific differences in H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 patterns have been observed in mouse models, suggesting epigenetic mechanisms may contribute to differential disease susceptibility [22]. Aging also profoundly affects these marks, with studies showing a trend toward loss of heterochromatin (decreased H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) and gain of euchromatin marks (increased H3K4me3) in human tissues, contributing to transcriptional dysregulation [6].

The enzymes responsible for writing, reading, and erasing these marks represent promising therapeutic targets. Inhibitors targeting EZH2 (the catalytic subunit of PRC2 that deposits H3K27me3) are in clinical development for various cancers [20]. Similarly, bromodomain inhibitors that disrupt reading of H3K27ac show efficacy in preclinical models of inflammation and cancer [19]. As these epigenetic therapies advance, comparative analysis of histone modification patterns across cell types will be essential for understanding their mechanisms and developing biomarkers for patient stratification.

H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 represent fundamental components of the epigenetic machinery that establishes permissive and repressive chromatin states. Their distinct yet interconnected functions enable precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression programs during development, in differentiated tissues, and in disease states. Advanced profiling technologies now enable mapping of these marks at single-cell resolution, revealing unprecedented details about cellular heterogeneity and epigenetic dynamics. As research continues to decipher the complex relationships between these modifications, their measurement will remain essential for understanding cell identity, plasticity, and the epigenetic basis of disease, ultimately guiding development of novel epigenetic therapeutics.

Cell differentiation, the process by which a stem cell transitions into a specialized cell type, is fundamentally guided by epigenetic mechanisms that shape gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Among these mechanisms, post-translational modifications of histone proteins play a dominant role in establishing and maintaining cellular identity by remodeling chromatin structure and regulating access to genomic information. Histone modifications create a complex "code" that influences whether genes are actively transcribed or silenced, thereby directing lineage specification from pluripotent stem cells to terminally differentiated tissues [15] [23]. This comparative guide examines the patterns of key histone modifications across different cell types and developmental contexts, synthesizing experimental data and methodologies to provide researchers with a practical framework for investigating epigenetic regulation in development and disease.

The dynamic interplay between activating and repressive histone modifications creates chromatin states that poise developmental genes for expression or enforce their silencing. For instance, the bivalent chromatin state—characterized by the simultaneous presence of H3K4me3 (an activating mark) and H3K27me3 (a repressive mark) at promoter regions—is thought to keep developmental genes in a transcriptionally poised state in stem cells, ready for rapid activation or permanent silencing upon differentiation signals [23]. Understanding how these modifications are established, maintained, and altered during cell fate decisions provides crucial insights for developmental biology, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine applications.

Comparative Patterns of Histone Modifications Across Cell Lineages

Quantitative Comparison of Histone Modification Patterns

Table 1: Histone Modification Patterns Across Cell Lineages and Developmental Stages

| Biological System | Key Histone Modifications | Genomic Distribution | Functional Role in Differentiation | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Epithelium [24] | H3K4me2, H3K27ac | Enhancer elements; dynamic redistribution | CDX2 binding site remodeling; guides crypt-to-villus differentiation | ChIP-seq in Caco-2 cells; conditional knockout mice |

| Hematopoietic System [23] | H3K4me3, H3K27me3 (bivalent) | Promoters of developmental genes | Poises genes for expression during progenitor maturation | H3K4M mutant mice; CUT&Tag; functional rescue assays |

| Mouse Pre-implantation Embryos [7] | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K36me3 | Genome-wide reprogramming | Zygotic genome activation; lineage priming for ICM/TE fate | TACIT single-cell profiling; multi-omic integration |

| Adult Mouse Striatum [25] | H3K4me3, H3K27me3 | Cell-type specific promoters | Defines D1 vs. A2A medium spiny neuron identity | ICuRuS method (INTACT + CUT&RUN) |

| Human Kidney Regions [26] | H3K4me3, H3K27me3 | Regional chromatin domains | Cortex, medulla, and papilla-specific gene regulation | Hi-C + CUT&RUN sequencing |

Context-Specific Modifications and Functional Outcomes

The comparative analysis of histone modifications across diverse biological systems reveals both conserved principles and context-specific behaviors. In the intestinal epithelium, H3K4me2 and H3K27ac modifications identify active enhancer elements that undergo dramatic remodeling during cellular differentiation from crypt progenitors to villus enterocytes. This enhancer reorganization facilitates the dynamic redistribution of transcription factor CDX2, a critical regulator of intestinal identity, which shifts from hundreds of sites in proliferating cells to thousands of new sites in differentiated cells [24]. This redistribution enables condition-specific gene expression through differential co-occupancy with other tissue-restricted transcription factors such as GATA6 and HNF4A.

In contrast, the hematopoietic system demonstrates the critical importance of bivalent chromatin domains, where promoters simultaneously bear both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 modifications. Using an innovative H3K4M mutation that dominantly blocks H3K4 methylation, researchers demonstrated that H3K4 methylation is dispensable for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance but essential for progenitor cell maturation. Mechanistically, H3K4 methylation opposes the deposition of repressive H3K27 methylation at differentiation-associated genes, and concomitant suppression of H3K27 methylation can rescue the lethal hematopoietic failure observed in H3K4-methylation-depleted mice [23]. This functional interaction between opposing histone modifications highlights the delicate balance required for proper lineage specification.

During mouse pre-implantation development, single-cell profiling of seven histone modifications revealed extensive epigenetic reprogramming with marked heterogeneity emerging as early as the two-cell stage. H3K27ac profiles exhibited particularly pronounced heterogeneity at the two-cell stage, suggesting this mark may prime cells for subsequent lineage decisions. The integration of multiple histone modifications enabled the identification of regulatory elements and previously unknown lineage-specifying transcription factors that determine the earliest branching toward inner cell mass versus trophectoderm fates [7].

Experimental Approaches for Histone Modification Analysis

Methodological Comparison for Histone Profiling

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Histone Modification Profiling

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Input Requirements | Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq [15] | Antibody-based chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing | 100-1000 bp | 10,000-1,000,000 cells | Genome-wide histone modification mapping | Established protocol; robust analysis tools |

| CUT&RUN [26] | Antibody-targeted MNase cleavage followed by sequencing | Single nucleosome | 500,000 nuclei | High-resolution histone modification profiling | Low background; minimal crosslinking artifacts |

| TACIT [7] | Target chromatin indexing and tagmentation | Single-cell | 20-50 cells | Single-cell histone modification atlas | Single-cell resolution; high genome coverage |

| ICuRuS [25] | INTACT isolation + targeted MNase cleavage | Cell-type specific | Single mouse brain region | Cell-type specific profiling in heterogeneous tissues | Cell-type specificity; minimal cellular stress |

| Micro-C [27] | MNase-based chromatin conformation capture | Nucleosome | 1-5 million cells | 3D genome organization with histone modification correlation | Highest resolution chromatin contacts |

Integrated Workflow for Multi-scale Histone Modification Analysis

Integrated Workflow for Histone Modification Analysis

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CUT&RUN for Regional Histone Modification Profiling [26]: The CUT&RUN protocol begins with the generation of a high-quality nuclear suspension from fresh or frozen tissue using a Dounce homogenizer in Nuclei EZ Lysis Buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. For each reaction, 500,000 nuclei are bound to 10 μL of activated ConA beads. Antibody binding is performed with 0.5 μg of specific histone modification antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3 or H3K27me3) with incubation overnight at 4°C. Chromatin digestion is then performed with pAG-MNase enzyme for 30 minutes on ice, followed by DNA purification using phenol-chloroform extraction. Library preparation utilizes the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit with 13 PCR amplification cycles. Quality control is performed via TapeStation analysis to verify nucleosomal periodicity.

TACIT for Single-Cell Histone Modification Profiling [7]: The TACIT method enables genome-wide single-cell profiling of histone modifications with high coverage. The protocol involves several rounds of antibody binding, protein A-Tn5 transposon (PAT) incubation, and tagmentation to profile multiple histone modifications. For CoTACIT (profiling multiple modifications in the same cell), sequential rounds of antibody binding and PAT incubation are performed for different histone marks. The method generates up to half a million non-duplicated reads per cell, with a 41-fold increase in non-duplicated reads compared to previous methods. The high sequencing depth enables robust identification of histone modification patterns at single-cell resolution across embryonic development stages.

ICuRuS for Cell-Type Specific Profiling in Neural Tissue [25]: The ICuRuS method combines INTACT (isolation of nuclei tagged in specific cell types) with CUT&RUN for histone modification profiling from specific neuronal populations in a single mouse brain. First, nuclei are isolated from A2a-Cre or D1-Cre; SUN1-GFP mice striatum using anti-GFP antibody conjugated to paramagnetic beads, yielding 8,000-10,000 nuclei per purification. Bead-bound nuclei are then incubated with antibodies against H3K4me3 or H3K27me3, followed by antibody-guided nucleosomal MNase cleavage. This approach minimizes cellular stress and artifacts associated with FACS sorting while providing cell-type specific resolution from minimal input material.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K4me1, H3K9me3, H3K36me3 | Specific recognition of histone modifications for enrichment protocols | All profiling methods (ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, TACIT) [7] [26] |

| Cell-Type Specific Nuclear Labels | SUN1-sfGFP-Myc mouse line | Nuclear tagging for INTACT isolation in specific cell types | ICuRuS method for neuronal subtyping [25] |

| Chromatin Digestion Enzymes | Micrococcal nuclease (MNase), pAG-MNase | Chromatin fragmentation for nucleosome resolution | CUT&RUN, Micro-C, TACIT [27] [25] [26] |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Formaldehyde, DSG, EGS | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions for capture | Hi-C, ChIP-seq protocol variants [27] |

| Transposase Systems | Protein A-Tn5 (PAT) | Tagmentation and library preparation | TACIT, CoTACIT [7] |

| Histone Mutant Models | H3K4M, H3K27M | Dominant blockade of specific histone methylation | Functional studies of histone modifications [23] |

| Nuclear Isolation Kits | Nuclei EZ Lysis Buffer | High-quality nuclear preparation from tissues | All nuclear-based epigenomic methods [26] |

Mechanistic Insights: Histone Modifications in Lineage Decisions

Bivalent Chromatin Regulation of Hematopoietic Differentiation

Bivalent Chromatin in Hematopoietic Differentiation

The mechanistic relationship between H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in bivalent chromatin represents a crucial regulatory node for lineage specification. In hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), bivalent domains maintain key developmental genes in a transcriptionally poised state, characterized by low-level expression yet primed for activation or silencing during differentiation [23]. The H3K4M mouse model demonstrated that depletion of H3K4 methylation leads to a fatal loss of all major blood cell types, despite normal HSPC maintenance and commitment. This phenotype results from an imbalance in bivalent chromatin, where loss of H3K4me3 allows expansion of repressive H3K27me3 domains, effectively locking genes in a silenced state and blocking progenitor maturation.

Notably, concomitant suppression of H3K27 methylation in H3K4-methylation-depleted mice rescues both the lethal phenotype and the aberrant gene expression patterns, confirming the functional interaction between these opposing modifications [23]. This mechanistic insight reveals that the ratio of activating to repressive marks, rather than their absolute presence or absence, determines the developmental potential of progenitor cells across lineages.

Dynamic Transcription Factor Collaboration in Intestinal Differentiation

In the intestinal epithelium, histone modification dynamics enable the contextual reprogramming of transcription factor binding during cellular differentiation. CDX2, a homeodomain protein critical for intestinal identity, demonstrates surprising lability in its genomic occupancy, redistributing from hundreds of sites in proliferating crypt cells to thousands of new sites in differentiated villus cells [24]. This redistribution corresponds with differential co-occupancy patterns with other tissue-specific transcription factors—specifically, preferential collaboration with GATA6 in proliferating cells and with HNF4A in differentiated cells.

The dynamic behavior of CDX2 is facilitated by pre-existing enhancer landscapes marked by H3K4me2 and H3K27ac, which prime regulatory elements for activation upon differentiation signals [24]. Conditional knockout models confirm distinct requirements for CDX2 in proliferating versus mature intestinal cells, with differentiated cells depending on CDX2 for maintaining the active enhancer configuration associated with maturity. This illustrates how stable transcription factor expression can produce context-specific regulatory outcomes through dynamic interactions with a changing epigenetic landscape.

Discussion: Comparative Insights and Research Applications

The comparative analysis of histone modification patterns across diverse biological systems reveals both universal principles and context-specific behaviors in epigenetic regulation of cellular identity. Several key themes emerge from this synthesis: (1) the importance of balanced opposition between activating and repressive marks in lineage decisions; (2) the dynamic nature of transcription factor interactions with a pre-existing epigenetic landscape; and (3) the increasing heterogeneity of epigenetic states as differentiation progresses.

From a methodological perspective, the choice of profiling approach depends critically on the biological question. For mapping population-level patterns in homogeneous cell populations, bulk ChIP-seq remains a robust and well-established approach [15]. For heterogeneous tissues, cell-type specific methods like ICuRuS provide crucial resolution [25], while for developmental processes with inherent cellular diversity, single-cell methods like TACIT offer unprecedented insights into emerging heterogeneity [7]. The integration of histone modification profiling with other genomic modalities—including chromatin conformation capture [27] [26], transcriptomics, and accessibility data—provides the most comprehensive view of the regulatory landscape governing cell identity.

These experimental approaches and mechanistic insights have direct applications for drug development, particularly in the context of epigenetic therapies for cancer and regenerative medicine strategies aimed at controlling cell fate decisions. The demonstrated rescue of differentiation defects through epigenetic rebalancing in hematopoietic cells [23] suggests promising therapeutic avenues for manipulating the histone modification landscape to direct cell fate outcomes in disease contexts.

In the evolving field of epigenetics, histone post-translational modifications (HPTMs) represent a crucial mechanism for regulating gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. While acetylation and methylation have been extensively studied, recent advances in high-throughput mass spectrometry have unveiled a novel class of short-chain lysine acylations that significantly expand the histone code's complexity [28]. Among these emerging modifications, succinylation, crotonylation, and lactylation have garnered significant attention for their unique chemical properties, distinct regulatory functions, and connections to cellular metabolism [29] [30] [31]. These modifications serve as important links between cellular metabolic status and epigenetic regulation, enabling cells to adapt their gene expression profiles in response to metabolic changes.

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these three acylations, focusing on their chemical properties, genomic distributions, functional consequences, and experimental methodologies. Understanding the nuances of these modifications provides researchers with critical insights into their roles in development, disease pathogenesis, and potential therapeutic targeting.

Comparative Analysis of Three Novel Histone Acylations

The table below provides a detailed comparison of the key characteristics of succinylation, crotonylation, and lactylation, highlighting their distinct properties and functional roles.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Novel Histone Acylations

| Feature | Succinylation (Ksuc/succ) | Crotonylation (Kcr) | Lactylation (Kla) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discover Year | 2011 [32] | 2011 [30] [33] | 2019 [31] [28] |

| Chemical Structure |  |

|

|

| Acyl Group | Succinyl (-CO-CH2-CH2-COOH) [29] | Crotonyl (-CO-CH=CH-CH3) [30] [33] | Lactyl (-CO-CHOH-CH3) [31] |

| Charge Change | +1 to -1 [29] | +1 to 0 [30] | +1 to 0 (presumed) |

| Key Writers | p300/CBP (also for acetylation) [33] | p300/CBP, MOF, Esa1 [30] [33] | p300 [31] |

| Key Erasers | SIRT5, SIRT7 [34] | Class I HDACs (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3) [30] [34] | HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 [31] |

| Metabolic Precursor | Succinyl-CoA [29] | Crotonyl-CoA [30] [33] | Lactyl-CoA [31] |

| Primary Functions | Promotes transcription, DNA repair, reduces nucleosome stability [29] | Marks active promoters/enhancers, stimulates transcription [30] [33] | Links metabolism to gene expression, promotes homeostasis in macrophages [31] |

| Genomic Distribution | Enriched at transcriptional start sites [29] | Enriched at transcriptional start sites and potential enhancers [30] | Associated with active gene promoters |

Chemical Properties and Structural Impacts

The biological functions of these acylations are deeply rooted in their distinct chemical properties, which directly influence chromatin structure and function.

Succinylation

Succinylation involves the covalent attachment of a succinyl group to the ε-amine of lysine residues. This modification introduces a significant change in charge from +1 to -1 at physiological pH, representing the most dramatic charge reversal among known histone PTMs [29]. Furthermore, the succinyl moiety has a larger molecular volume compared to acetyl or methyl groups, enabling it to introduce more substantial structural disturbances in the nucleosome [29]. These properties allow succinylation to significantly weaken histone-DNA interactions by disrupting electrostatic attractions, thereby promoting an open chromatin configuration conducive to transcription.

Crotonylation

Crotonylation adds a four-carbon crotonyl group featuring a distinctive C-C π bond that creates a rigid, planar conformation [30] [33]. While its charge neutralization effect (from +1 to 0) resembles acetylation, the extended hydrocarbon chain increases both hydrophobicity and bulkiness compared to acetylation [30]. This unique structure provides a specific mechanism for reader protein recognition and binding, distinguishing it from other acylation types despite similar charge effects.

Lactylation

Lactylation incorporates a lactyl group derived from lactic acid. The key structural feature is the presence of a hydroxyl group, which may facilitate hydrogen bonding interactions distinct from other acyl modifications [31]. While detailed structural studies on histone lactylation are still emerging, this modification appears to create a unique binding surface for specific reader proteins that differentiate it from other acyl marks.

Genomic Distribution and Functional Roles

These modifications exhibit distinct genomic distributions and participate in diverse biological processes, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Genomic Distribution and Functional Roles

| Modification | Conserved Sites | Genomic Localization | Biological Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Succinylation | H3K79, H4K77 in yeast [29] | Transcriptional start sites (bimodal pattern) [29] | Transcription activation, DNA damage repair, disease pathogenesis [29] |

| Crotonylation | Broadly conserved across eukaryotes [30] | Active promoters, enhancers [30] [33] | Gene activation, spermatogenesis, cell differentiation [30] [33] |

| Lactylation | 26 sites in HeLa, 18 in mouse BMDMs [31] | Active gene promoters [31] | Macrophage polarization, tumor microenvironment, metabolic memory [31] |

Functional Mechanisms

- Succinylation: Demonstrates a strong correlation between promoter succinylation and gene expression levels [29]. Experimental evidence confirms that specific succinylation sites (e.g., H4K77succ and H3K122succ) directly destabilize nucleosomes by weakening DNA-histone interactions, thereby increasing DNA unwrapping rates and facilitating transcription factor binding [29].

- Crotonylation: Functions as a potent transcriptional activation mark, with studies showing that histone crotonylation can stimulate transcription more effectively than acetylation in certain contexts [30]. This modification contributes to chromatin instability during spermatogenesis, facilitating the histone-to-protamine transition essential for sperm maturation [30].

- Lactylation: Represents a novel mechanism through which lactate links cellular metabolism to epigenetic regulation. In macrophages, lactylation induces a pro-homeostatic gene expression program during the later stages of inflammation, promoting tissue repair and resolution [31].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Studying these novel modifications requires specialized experimental approaches and reagents. The workflow typically begins with antibody-based enrichment, followed by mass spectrometric analysis and functional validation.

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Novel Acylations

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-succinyl-lysine [29], Anti-crotonyl-lysine [30] [33], Anti-lactyl-lysine [31] | Immunodetection, Western blotting, immunofluorescence, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) |

| Metabolic Precursors | Isotope-labeled succinate (D4-succinate) [29], Sodium crotonate [30], Isotope-labeled lactate [31] | Metabolic labeling to track modification dynamics and validate sites |

| Enzyme Modulators | SIRT5 inhibitors (for succinylation) [34], HDAC1/2/3 inhibitors (for crotonylation/lactylation) [30] [31], p300/CBP inhibitors [33] | Manipulate modification levels to study functional consequences |

| Synthetic Peptides | Site-specifically modified histones (e.g., H4K77succ [29]) | In vitro biochemical and structural studies, standardization in MS |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Synthetic succinylated, crotonylated, and lactylated peptides [29] [31] | Reference standards for accurate identification and quantification by LC-MS/MS |

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard integrated workflow for identifying and validating novel histone acylations:

Detailed Methodologies

Mass Spectrometry-Based Identification

- Procedure: Histones are acid-extracted from cells or tissues and digested with trypsin. Peptides are separated using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [29] [33]. For novel modification discovery, researchers employ PTMap algorithm to scan for unexpected mass shifts that correspond to potential new modifications [33].

- Validation: Putative sites are confirmed through comparison with synthetic peptides bearing the suspected modification, HPLC co-elution experiments, and isotopic labeling in living cells (e.g., using D4-succinate or labeled lactate) [29] [31] [33].

- Key Considerations: Distinguishing between isobaric modifications (e.g., succinylation vs. malonylation) requires high-resolution mass spectrometry and careful validation [29].

Antibody-Based Detection Methods

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Utilizes modification-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-succinyl-lysine) to isolate bound DNA fragments, followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map genomic distributions [29]. For example, succinyl-lysine ChIP-seq revealed enrichment at transcriptional start sites with a characteristic bimodal pattern [29].

- Immunofluorescence and Western Blotting: Enable spatial localization and relative quantification of modifications across samples or conditions [31] [35].

- Limitations: Antibody specificity remains a challenge, requiring validation using site-directed mutagenesis or mass spectrometry.

Functional Validation Approaches

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Lysine residues are mutated to arginine (mimicking unmodified state) or glutamic acid (mimicking charge reversal of succinylation) to study functional consequences [29].

- Chemical Biology Approaches: Expressed protein ligation (EPL) enables generation of histones with site-specific modifications (e.g., H4K77succ) for biochemical and biophysical studies [29].

- Enzyme Modulation: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout or pharmacological inhibition of putative writers and erasers to establish causal relationships.

Metabolic Connections and Regulatory Enzymes

These modifications function at the intersection of metabolism and epigenetics, with their levels being influenced by cellular metabolic states.

Metabolic Pathways and Regulation

The diagram below illustrates the metabolic connections and regulatory enzymes governing these modifications:

Enzyme Systems and Metabolic Regulation

Succinylation

- Writers: Primarily p300/CBP, which exhibits broad substrate specificity for various acylations including succinylation [33]. The modification can also occur non-enzymatically in conditions of high succinyl-CoA concentration, particularly in mitochondrial environments with alkaline pH [34].

- Erasers: SIRT5 and SIRT7 are the primary desuccinylases. SIRT7 specifically removes succinylation from H3K122, promoting chromatin condensation and DNA repair [34].

- Metabolic Regulation: Succinyl-CoA abundance is particularly high in tissues with numerous mitochondria (heart, liver, brown adipose), creating tissue-specific succinylation landscapes [29].

Crotonylation

- Writers: Multiple HATs including p300/CBP, MOF (MYST family), and Esa1 (yeast homolog) possess histone crotonyltransferase (HCT) activity [30] [33]. p300's HCT activity is less efficient than its acetyltransferase activity due to steric constraints in the active site [30].

- Erasers: Class I HDACs (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3) rather than sirtuins serve as the major histone decrotonylases [30] [34]. Mutants of HDAC1 and HDAC3 have been generated that impair deacetylase but retain decrotonylase activity [34].

- Metabolic Regulation: Crotonyl-CoA levels are regulated by multiple pathways including ACSS2-mediated conversion of crotonate, β-oxidation of glutaryl-CoA by BCDH, and lysine/tryptophan metabolism [33].

Lactylation

- Writers: p300 has been identified as a major lactyltransferase, with histone lactylation significantly impaired upon p300 knockdown in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages [31].

- Erasers: HDAC1-3 have been implicated as potential delactylases, though the enzymatic regulation of lactylation is less characterized than other modifications [31].

- Metabolic Regulation: Lactate concentration directly influences lactylation levels, creating a direct link between glycolytic flux (e.g., Warburg effect in cancer cells) and epigenetic regulation [31].

Succinylation, crotonylation, and lactylation represent distinct epigenetic marks with unique chemical properties, regulatory mechanisms, and functional consequences. While all three modifications are associated with active transcription, they achieve this through different structural mechanisms—succinylation via dramatic charge reversal, crotonylation through its rigid planar structure, and lactylation via its metabolic connection to lactate.

From a methodological perspective, researching these modifications requires integrated approaches combining advanced mass spectrometry, specific immunological tools, and careful functional validation. The metabolic regulation of these marks positions them as key sensors of cellular physiological states, with implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

Future research will likely focus on identifying additional reader proteins that specifically recognize each modification, elucidating cross-talk between different acylation types, and developing more specific modulators for the enzymatic regulators of these modifications. As our understanding of these novel acylations deepens, they offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, metabolic disorders, and other diseases linked to epigenetic dysregulation.

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping and Comparing Epigenomes

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has established itself as a foundational methodology in modern epigenomics, providing researchers with an powerful tool for genome-wide profiling of protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications [36] [37]. This technique enables the precise mapping of transcription factor binding sites, nucleosome positioning, and epigenetic marks across the entire genome, offering unprecedented insights into the regulatory mechanisms that govern gene expression and cellular identity [37]. For nearly two decades, ChIP-seq has served as the benchmark technology for investigating how histone modification patterns contribute to developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and cellular differentiation [38].

The significance of ChIP-seq in comparative studies of histone modifications across different cell types cannot be overstated [36]. By providing a comprehensive view of the epigenomic landscape, ChIP-seq has enabled researchers to identify cell-type-specific regulatory elements, characterize epigenetic signatures associated with cellular states, and understand how chromatin organization influences transcriptional programs [37]. As scientists increasingly recognize that systematic profiling of epigenomes across multiple cell types and developmental stages is essential for understanding biological processes and disease states, ChIP-seq has remained the go-to technology despite the emergence of newer methods [36]. This review examines ChIP-seq's continued status as the gold standard while critically evaluating its limitations in comparative epigenomic studies, particularly in the context of emerging alternative technologies.

ChIP-seq Methodology: Principles and Workflow

The standard ChIP-seq protocol consists of multiple meticulously optimized steps designed to capture a snapshot of protein-DNA interactions in living cells [37]. The process begins with formaldehyde cross-linking, where proteins are covalently bound to their genomic DNA substrates to preserve these transient interactions through subsequent processing steps [39]. Following cross-linking, chromatin is fragmented typically through sonication to generate fragments in the 200-600 base pair range, although micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion may be used for nucleosome positioning studies as it provides more precise cleavage between nucleosomes [36] [37].

The core of the ChIP-seq technique involves immunoprecipitation, where an antibody specific to the protein or histone modification of interest is used to selectively enrich for DNA fragments bound to the target [37]. After antibody incubation and purification, the cross-links are reversed, and the immunoprecipitated DNA is purified [39]. The resulting DNA fragments are then processed for high-throughput sequencing through library preparation steps that include end repair, adapter ligation, size selection, and PCR amplification [37]. Finally, the prepared libraries are sequenced using next-generation sequencing platforms, with the Illumina platform being the most commonly used for ChIP-seq applications [37].

Key Research Reagents for ChIP-seq Experiments

The quality and reliability of ChIP-seq data depend critically on several key reagents. The table below outlines essential materials and their specific functions in the ChIP-seq workflow:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Reagents | Formaldehyde (37%), Glycine | Presves protein-DNA interactions; stopped with glycine [37] |

| Chromatin Preparation | PIPES, KCl, IGEPAL, SDS, Protease inhibitors (aprotinin, leupeptin, PMSF) | Cell lysis, nuclei isolation, chromatin fragmentation [37] |

| Immunoprecipitation | Target-specific antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3), Protein A/G beads | Enrichment of target protein-DNA complexes [37] |

| DNA Purification & Library Prep | QIAquick PCR purification kit, DNA size selection beads | DNA cleanup, adapter ligation, library amplification [37] |

| Quality Control | NanoDrop 1000, Bioanalyzer | Quantification and quality assessment of DNA [37] |

Visualization of the ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the standard ChIP-seq protocol:

ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

ChIP-seq as the Gold Standard: Advantages and Strengths

ChIP-seq offers several significant advantages that have cemented its position as the reference technology for epigenomic mapping. One of its most notable strengths is its comprehensive genome-wide coverage, which is not limited by predetermined probe sequences as with earlier array-based methods (ChIP-chip) [36] [39]. This enables researchers to investigate protein-DNA interactions across repetitive regions of the genome, including heterochromatin and microsatellites, which were previously challenging to study with microarray-based approaches [36].

The technique provides excellent base-pair resolution, a substantial improvement over the 30-100 base pair resolution typically achieved with ChIP-chip [39]. This high resolution allows for precise mapping of transcription factor binding sites and enables the identification of sequence motifs with greater accuracy [36]. Furthermore, ChIP-seq offers a larger dynamic range compared to array-based methods, as it does not suffer from signal saturation limitations that can obscure biologically meaningful peaks in ChIP-chip experiments [36].

ChIP-seq has proven remarkably versatile in its applications, successfully profiling various chromatin features including transcription factor binding, histone modifications, histone variants, and nucleosome positioning [36] [37]. The technology has been particularly instrumental in creating reference epigenomes through large-scale consortium projects such as ENCODE and the Roadmap Epigenomics Project, which have generated comprehensive maps of histone modifications across diverse cell types and tissues [37] [40].

From a practical standpoint, ChIP-seq requires relatively lower sample input compared to ChIP-chip, with robust protocols available for samples containing as little as 1 μg of chromatin [37]. Continued methodological refinements have further reduced input requirements, with specialized protocols now enabling ChIP-seq from 100,000 cells or fewer, considerably expanding its applicability to rare cell populations and precious clinical samples [41].

Limitations of ChIP-seq in Comparative Studies

Despite its numerous advantages, ChIP-seq presents several significant limitations that researchers must consider when designing comparative studies of histone modifications across cell types.

Technical and Resource Challenges

A primary constraint of conventional ChIP-seq is its substantial cell number requirement. Standard protocols typically need millions of cells per immunoprecipitation, creating a major bottleneck for investigating rare cell types or precious clinical samples [42] [41]. Although optimized low-cell protocols have been developed, they often involve complex procedures and still face challenges with increased unmapped reads and PCR duplicates as cell numbers decrease [41].

The technique is also notoriously time-consuming, typically requiring approximately one week from cell processing to sequencing-ready libraries even with optimized protocols [42]. This extended timeframe limits experimental throughput and reduces the number of conditions that can be practically compared in a single study.

From a resource perspective, ChIP-seq remains relatively expensive, with costs typically ranging between $1,000-$2,000 per sequencing lane [39]. These expenses can become prohibitive in large-scale comparative studies requiring multiple conditions, replicates, and histone marks. Furthermore, the method demands specialized equipment and expertise across multiple domains, including molecular biology for sample processing and bioinformatics for data analysis, creating barriers to adoption for some research groups [39].

Data Quality and Experimental Variability

A critical limitation of ChIP-seq stems from its dependence on antibody quality. Commercial antibodies vary considerably in their specificity and efficiency, with studies indicating that over 70% of histone modification antibodies may display unacceptable cross-reactivity or poor target recognition [42]. This variability introduces significant experimental noise and can compromise reproducibility across studies and laboratories.

The technique is also plagued by high background signal resulting from multiple factors including cross-linking artifacts, non-specific immunoprecipitation, and biases introduced during chromatin fragmentation [42]. This background noise necessitates deeper sequencing (typically 20-40 million reads per library) to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, further increasing costs [42].

Several steps in the ChIP-seq workflow introduce technical variability, particularly chromatin fragmentation and immunoprecipitation efficiency [42]. This variability complicates comparative analyses across cell types and conditions, requiring extensive optimization and multiple replicates to ensure robust conclusions. Additionally, the library preparation process involves multiple enzymatic steps and purifications, each resulting in sample loss and potential biases, particularly problematic when working with low-input samples [41].

Computational and Analytical Challenges

The analysis of ChIP-seq data presents substantial computational challenges, particularly for researchers without specialized bioinformatics expertise [36]. The large datasets generated require significant computational resources for alignment, peak calling, and downstream analyses. Furthermore, peak calling program selection significantly influences results, with different algorithms performing variably depending on the specific histone modification being studied [40]. For instance, marks with broad domains like H3K27me3 require different analytical approaches compared to sharp marks like H3K4me3 [40].

There remains no consensus on optimal controls for ChIP-seq experiments, with researchers using various approaches including input DNA, no-antibody controls, or non-specific IgG controls [39]. This lack of standardization complicates cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses. Finally, comparative analyses are challenged by batch effects and normalization issues, as technical variations between experiments can obscure true biological differences in histone modification patterns across cell types [41].

Emerging Alternatives to ChIP-seq

Recent technological advances have introduced several alternative methods that address specific limitations of ChIP-seq. The table below compares key features of ChIP-seq with two prominent emerging technologies:

| Parameter | ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | CUT&Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Input Requirements | 1-20 million cells [42] [41] | 100 - 500,000 cells [42] | As few as 100,000 nuclei [42] |

| Protocol Duration | ~7 days [42] | ~3 days [42] | Slightly faster than CUT&RUN [42] |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-40 million reads [42] | 3-8 million reads [42] | Similar to CUT&RUN [42] |

| Background Noise | High [42] [43] | Low [42] [43] | Low [42] |

| Resolution | 200-600 bp fragments [43] | High (smaller fragments) [43] | High (smaller fragments) [42] |

| Cross-linking | Required [42] [37] | Typically native conditions [42] | Typically native conditions [42] |

| Technical Expertise | Moderate [42] | Moderate [42] | High ("expert-level") [42] |

| Target Compatibility | Broad [42] | Broad (histone PTMs, transcription factors) [42] | More limited for low abundance targets [42] |

CUT&RUN: A Streamlined Alternative

Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) represents a significant departure from traditional ChIP-seq methodology [43]. This technique utilizes protein A-protein G (pAG) fusion proteins bound to magnetic beads to tether enzymatic reagents to antibody-bound chromatin targets in permeabilized cells or nuclei [42] [43]. The bound chromatin is then cleaved in situ by the nuclease, releasing specific fragments for subsequent extraction and sequencing [43].

CUT&RUN offers several advantages for comparative studies of histone modifications, including dramatically reduced background signal due to the elimination of cross-linking and chromatin fragmentation steps [43]. The method requires significantly fewer cells, with robust results obtainable from as few as 100-500,000 cells, and sometimes even lower [42]. Furthermore, CUT&RUN enables higher resolution mapping due to the production of smaller DNA fragments compared to sonication-based ChIP-seq [43].

CUT&Tag: An Expert-Level Innovation

Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) further refines the principles of CUT&RUN by integrating a hyperactive Tn5 transposase for simultaneous cleavage and adapter tagging of target chromatin [42]. This innovation streamlines the library preparation process by combining fragmentation and adapter tagging into a single step, potentially reducing handling time and sample loss [42].

While CUT&Tag shares many advantages with CUT&RUN, including low background and minimal cell input requirements, it is generally considered more technically challenging and requires practiced hands to generate robust results [42]. The method is particularly sensitive to errors in assay setup, ConA bead loss, and antibody specificity, making it less suitable for researchers new to epigenomic mapping or those working with novel targets [42].

Single-Cell Epigenomic Methods

Recent years have witnessed the development of single-cell ChIP-seq methodologies, such as the Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation (TACIT) approach, which enables genome-coverage single-cell profiling of histone modifications [7]. These innovations are particularly valuable for comparative studies of cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues, such as during early embryonic development or in tumor microenvironments [7] [38].

The following diagram illustrates the key methodological differences between ChIP-seq and the newer CUT&RUN approach:

Methodology Comparison: ChIP-seq vs. CUT&RUN

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing continues to serve as the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications, offering comprehensive coverage, well-established protocols, and extensive validation through countless publications and consortium projects [36] [37]. Its strengths in providing a robust, versatile platform for epigenomic profiling ensure it will remain a fundamental tool in comparative studies of chromatin states across cell types and conditions.

However, researchers must carefully consider the significant limitations of ChIP-seq, particularly its substantial cell input requirements, technical variability, and high background noise [42] [41]. These constraints become particularly relevant when studying rare cell populations, clinical samples with limited material, or when conducting large-scale comparative analyses where cost and throughput are major considerations [42].