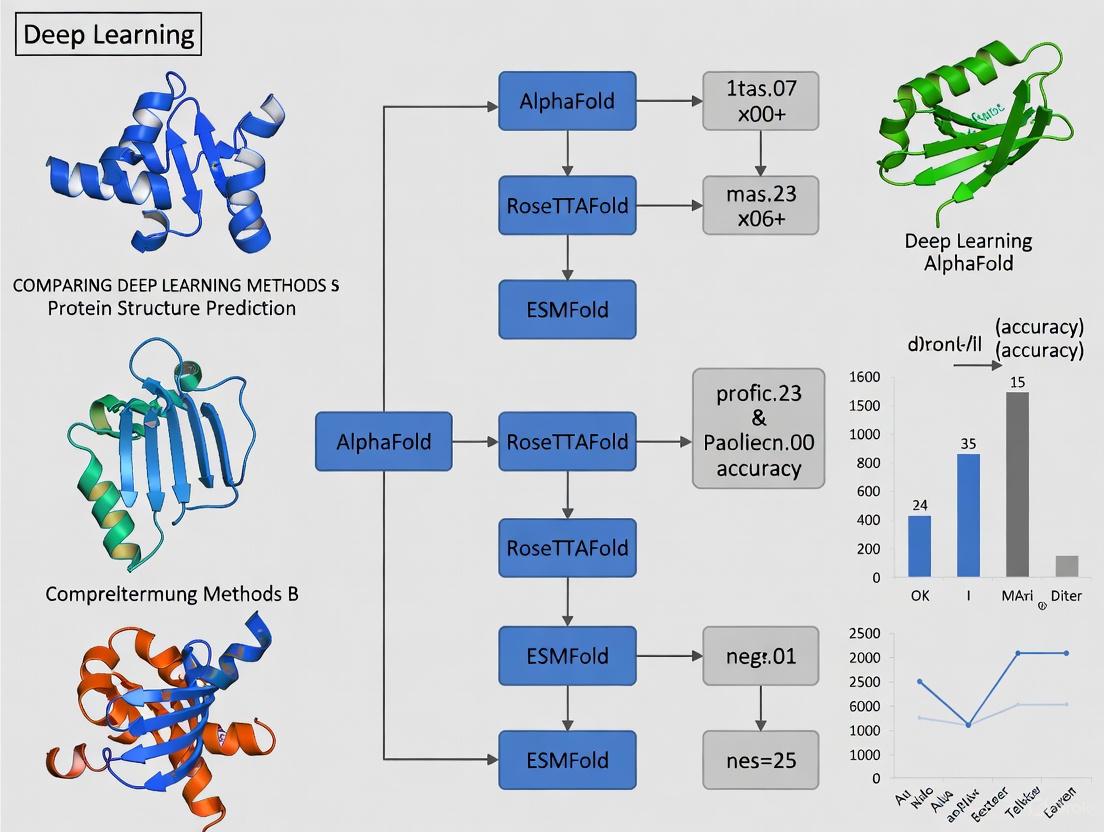

Deep Learning in Protein Structure Prediction: A Comprehensive Comparison of AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, and Emerging Methods

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern deep learning methods for protein structure prediction, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Deep Learning in Protein Structure Prediction: A Comprehensive Comparison of AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, and Emerging Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern deep learning methods for protein structure prediction, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles behind the shift from traditional experimental techniques to AI-driven approaches, with a detailed comparison of leading models like AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, RoseTTAFold, and D-I-TASSER. The scope includes methodological architectures, practical applications in drug discovery and vaccine design, critical troubleshooting of limitations such as orphan proteins and dynamic behavior, and rigorous validation through CASP benchmarks. By synthesizing performance metrics and real-world case studies, this review serves as an essential guide for selecting and applying these transformative tools in biomedical research.

From Sequence to Structure: The Deep Learning Revolution in Protein Folding

The "protein folding problem"—the challenge of predicting a protein's three-dimensional native structure solely from its one-dimensional amino acid sequence—represents one of the most enduring fundamental challenges in computational biology [1]. For decades, this field has been framed by two foundational concepts: Anfinsen's dogma, which established that the native structure is the thermodynamically most stable conformation under physiological conditions and is determined exclusively by the amino acid sequence; and the Levinthal paradox, which highlighted the astronomical impossibility of proteins discovering their native fold through random conformational sampling [2] [3]. This paradox, estimating approximately 10³⁰⁰ possible conformations for a typical protein, implied that folding must proceed through specific pathways or a guided energy "funnel" rather than exhaustive search [1].

The recent transformative advances in deep learning-based protein structure prediction, recognized by the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, have fundamentally altered the landscape of this field [4]. These AI systems, particularly AlphaFold and its successors, have achieved unprecedented accuracy in structure prediction, effectively solving the folding problem for many standard protein domains [1]. However, this breakthrough has also revealed new challenges and limitations, particularly regarding protein dynamics, complex assembly, and the prediction of functional states [4] [5].

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of contemporary deep learning methods for protein structure prediction, examining their performance, underlying methodologies, and limitations within the enduring theoretical framework established by Anfinsen and Levinthal.

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Context

Foundational Principles

The conceptual groundwork for protein folding rests on several key principles established throughout the second half of the 20th century. Christian Anfinsen's seminal experiments with ribonuclease A in the 1960s demonstrated that a denatured protein could spontaneously refold into its functional native structure without external guidance, leading to the conclusion that all information required for three-dimensional structure is encoded within the linear amino acid sequence [2] [1]. This "thermodynamic hypothesis" became a central dogma of molecular biology, suggesting that the native state represents the global free energy minimum under physiological conditions.

Simultaneously, Cyrus Levinthal's 1969 calculation highlighted the profound paradox that proteins fold on biologically relevant timescales (microseconds to seconds) despite the mathematically astronomical number of possible conformations [6] [3]. This insight suggested that proteins do not fold by exhaustive search but rather follow specific folding pathways—a concept that would later evolve into the energy landscape theory and folding funnel hypothesis [2]. The energy landscape theory frames folding as a funnel-guided process where native states occupy energy minima, with the landscape's ruggedness accounting for the heterogeneity and complexity observed in folding pathways [2].

The Role of Molecular Chaperones

As research progressed, it became evident that intracellular conditions—macromolecular crowding, physiological temperatures, and rapid translation rates—increase the risk of misfolding and aggregation [2]. Cells utilize molecular chaperones, including heat shock proteins (HSPs), to mitigate these risks. These chaperones assist in proper folding, prevent aggregation, refold misfolded proteins, and aid in degradation, thereby maintaining proteostasis [2]. The discovery of chaperones complemented Anfinsen's dogma by demonstrating that while the folding information is sequence-encoded, the cellular environment provides crucial facilitation to ensure fidelity under physiological constraints.

Deep Learning Methods for Protein Structure Prediction

Methodological Categories

Computational approaches to protein structure prediction are broadly categorized into three methodological paradigms:

- Template-Based Modeling (TBM): Relies on identifying known protein structures as templates through sequence or structural homology. It requires at least 30% sequence identity between target and template and includes comparative modeling and threading/fold recognition techniques [6] [7].

- Template-Free Modeling (TFM): Predicts structure directly from sequence without global template information, instead using multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to extract co-evolutionary signals and geometric constraints [6] [7].

- Ab Initio Methods: Based purely on physicochemical principles without reliance on existing structural information, representing true "free modeling" [6] [7].

Modern deep learning approaches primarily operate within the TFM paradigm, though they are trained on known structures from the Protein Data Bank and thus indirectly dependent on existing structural information [6].

Key Architectural Innovations

The breakthrough in prediction accuracy achieved by deep learning systems stems from several key architectural innovations:

- Evolutionary Scale Modeling: Leveraging multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of homologous sequences to infer evolutionary constraints and co-evolutionary patterns that indicate spatial proximity [1].

- Transformer Architectures: The Evoformer module in AlphaFold2 processes MSAs and pairwise representations through attention mechanisms to capture long-range interactions [1].

- Geometric Learning: Equivariant neural networks that respect the physical symmetries of molecular structures, enabling direct prediction of atomic coordinates [1].

- End-to-End Learning: Integrated systems that simultaneously evolve sequence representations and structural geometry, progressively refining predictions through recycling mechanisms [1].

Comparative Analysis of Leading Deep Learning Systems

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Protein Structure Prediction Systems

| System | Developer | Key Methodology | Reported TM-score (CASP15) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | DeepMind | Evoformer, MSAs, end-to-end structure module | 0.92 (Global Distance Test) [1] | High monomer accuracy, robust for single chains | Limited complex accuracy, template dependence |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | DeepMind | Extension of AF2 for multimers | Baseline (CASP15) [5] | Improved complex prediction | Lower accuracy than monomer AF2 |

| AlphaFold3 | DeepMind | Diffusion models, multimolecular | 10.3% lower than DeepSCFold (CASP15) [5] | Handles proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands | Web server only, limited accessibility |

| DeepSCFold | Academic | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | 11.6% improvement over AF-Multimer [5] | High complex accuracy, antibody-antigen improvement | Computationally intensive |

| RoseTTAFold | Baker Lab | Three-track network, geometric learning | Near-AlphaFold accuracy [1] | Open source, good performance | Slightly lower accuracy than AF2 |

| ESMFold | Meta AI | Protein language model, single-sequence | Moderate accuracy | Fast, no MSA requirement | Lower accuracy than MSA methods |

Table 2: Experimental Benchmarking on Complex Targets (CASP15 and Antibody-Antigen)

| Method | TM-score (CASP15 Multimers) | Interface Improvement over AF-Multimer | Success Rate (Antibody-Antigen Interfaces) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | 11.6% improvement [5] | Not specified | 24.7% improvement over AF-Multimer [5] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline [5] | Baseline | Baseline |

| AlphaFold3 | 10.3% lower than DeepSCFold [5] | Not specified | 12.4% improvement over AF-Multimer [5] |

| Yang-Multimer | Lower than DeepSCFold [5] | Not specified | Not specified |

| MULTICOM | Lower than DeepSCFold [5] | Not specified | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation: The CASP Framework

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biennial blind experiment that has served as the gold standard for evaluating protein structure prediction methods since 1994 [1]. In each round, organizers select newly solved but embargoed experimental structures and release only their amino acid sequences. Modeling groups worldwide then submit predictions, which independent assessors compare to the experimental structures using metrics including:

- Global Distance Test (GDT): A measure of the percentage of amino acids within a threshold distance from their correct positions [1].

- TM-score: A metric for measuring structural similarity, with values >0.5 indicating generally correct topology [5].

- Interface Accuracy: Specialized metrics for evaluating protein-protein interaction interfaces in complexes [5].

DeepSCFold Protocol for Complex Structure Prediction

Recent advances have specifically targeted the challenge of predicting protein complex structures. The DeepSCFold protocol exemplifies the cutting-edge methodology for this task [5]:

Input Processing: Starting with input protein complex sequences, the method first generates monomeric multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) from diverse sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB).

Structural Similarity Prediction: A deep learning model predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) purely from sequence information, quantifying structural similarity between input sequences and homologs in monomeric MSAs.

Interaction Probability Estimation: A second deep learning model estimates interaction probability (pIA-score) based on sequence-level features to identify potential interacting partners.

Paired MSA Construction: Using pSS-scores, pIA-scores, and multi-source biological information (species annotations, UniProt accessions, known complexes), the method systematically constructs paired MSAs that capture inter-chain interaction patterns.

Structure Prediction and Refinement: The series of paired MSAs are used for complex structure prediction through AlphaFold-Multimer, with model selection via quality assessment methods and iterative refinement.

DeepSCFold Workflow for Protein Complex Prediction

AlphaFold2 Methodology

The AlphaFold2 system, which represented a quantum leap in prediction accuracy, employs a sophisticated multi-stage process [1]:

Input Representation: The system takes as input the target amino acid sequence and generates a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) using homologous sequences from genomic databases.

Evoformer Processing: The MSA and pairwise representations are processed through the Evoformer module, a novel transformer architecture that learns co-evolutionary patterns and geometric constraints simultaneously through attention mechanisms.

Structure Module: A lightweight, equivariant structure module then converts the learned representations into atomic coordinates, specifically predicting the 3D positions of backbone and side chain atoms.

Recycling: The system recycles its own predictions through the network multiple times, progressively refining the structural output.

Loss Calculation: The model is trained using loss functions that incorporate both structural accuracy (frame-aligned point error) and physical constraints.

Critical Assessment of Current Limitations

Despite remarkable progress, current deep learning approaches face fundamental limitations that prevent them from fully capturing the biological reality of protein folding and function.

The Dynamic Nature of Protein Structures

Proteins in their native biological environments are not static structures but exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations [4]. Current AI systems typically produce single static models, which cannot adequately represent the millions of possible conformations that proteins can adopt, especially for proteins with flexible regions or intrinsic disorders [4]. This limitation is particularly significant for understanding allosteric regulation and conformational changes central to protein function.

Environmental Dependence and the Experimental Paradox

A fundamental challenge arises from the environmental dependence of protein conformations. The thermodynamic environment—including pH, ionic strength, molecular crowding, and post-translational modifications—critically influences protein structure [3]. However, analytical determination of protein 3D structure inevitably requires disrupting this native thermodynamic environment, meaning that structures in databases may not fully represent functional, physiologically relevant conformations [3]. This creates an epistemological challenge analogous to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics: the process of measurement may alter the phenomenon being observed [3].

Limitations in Complex Prediction

While methods like DeepSCFold have made significant advances, accurately modeling protein complexes remains substantially more challenging than predicting monomeric structures [5]. Key limitations include:

- Difficulty capturing inter-chain interaction signals, particularly for transient complexes

- Challenges with antibody-antigen systems that lack clear co-evolutionary signals

- Inaccurate modeling of interface regions with high flexibility

- Limited performance on complexes with intertwined subunits or large conformational changes upon binding

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6] | Repository of experimentally determined structures | Training data for ML models; template source |

| Sequence Databases | UniProt, UniRef, TrEMBL [6] [5] | Comprehensive protein sequence repositories | MSA construction; evolutionary analysis |

| Metagenomic Databases | MGnify, Metaclust, BFD [5] | Environmental sequence collections | Enhanced MSA depth for difficult targets |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold [1] | End-to-end structure prediction | Primary structure prediction tools |

| MSA Construction Tools | HHblits, Jackhammer, MMseqs2 [5] | Rapid sequence search and alignment | Generating input features for prediction |

| Complex Prediction | AlphaFold-Multimer, DeepSCFold [5] | Specialized multimer structure prediction | Protein-protein complex modeling |

| Model Quality Assessment | DeepUMQA-X [5] | Quality estimation of predicted models | Model selection and confidence estimation |

| Visualization & Analysis | SwissPDBViewer, MODELLER [6] | Structure visualization and analysis | Model inspection and refinement |

The field of protein structure prediction stands at a pivotal juncture. While the fundamental challenge of predicting static structures from sequence has been largely solved for single-domain proteins, several critical frontiers remain active areas of research:

Emerging Research Priorities

- Dynamics and Conformational Ensembles: Future methods must move beyond single static structures to model the full ensemble of biologically relevant conformations, capturing the intrinsic dynamics essential for protein function [4].

- Environmental Integration: Incorporating environmental factors such as pH, membrane interactions, and post-translational modifications will be crucial for predicting physiologically accurate structures [3].

- Functional Prediction: The ultimate goal extends beyond structure to function prediction, requiring integration of structural models with biochemical and biophysical principles to understand catalytic mechanisms, allostery, and signaling pathways [4].

- De Novo Protein Design: Inverse folding—designing sequences that fold into predetermined structures—represents a complementary challenge with significant applications in biotechnology and therapeutics [8].

The journey from Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis and Levinthal's paradox to contemporary deep learning systems represents a remarkable scientific achievement. Modern AI-based prediction methods have effectively solved the classical protein folding problem for standard protein domains, fulfilling Anfinsen's vision that the amino acid sequence determines the three-dimensional structure.

However, these advances have also revealed new complexities and challenges. The dynamic nature of proteins, their environmental sensitivity, and the limitations in modeling complexes underscore that current approaches, while powerful, do not fully capture the biological reality of protein function in living systems. The Heisenberg-like paradox—that analytical determination of structure may alter the very conformation being studied—suggests fundamental limits to purely computational prediction [3].

As the field progresses, the integration of physical principles with data-driven approaches, together with a focus on dynamics and environmental context, will be essential for advancing from structural prediction to functional understanding. This evolution will enable deeper insights into biological mechanisms and accelerate drug discovery, ultimately bridging the gap between static structure and dynamic function in living systems.

For decades, structural biology has relied on three primary experimental techniques to determine the three-dimensional structures of proteins and other biological macromolecules: X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). These methods have provided foundational insights into molecular function and mechanism, directly enabling structure-based drug design [9] [10]. However, the escalating demands of modern drug discovery and the paradigm shift toward complex therapeutic targets like protein-protein interactions have placed unprecedented pressure on these traditional methods [11]. Furthermore, the rapid development of deep learning-based protein structure prediction methods such as AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold has created a new context for evaluating traditional structural biology approaches [6].

This guide objectively compares the limitations of X-ray crystallography, NMR, and cryo-EM, focusing on their high costs and low throughput as critical bottlenecks in research and drug development pipelines. We present quantitative comparisons of resource requirements, detailed experimental protocols that reveal sources of inefficiency, and visualize the complex workflows that contribute to their technical challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these limitations is crucial for strategic planning and for appreciating the transformative potential of computational methods in structural biology.

Comparative Analysis of Traditional Structural Biology Methods

The limitations of traditional structural methods manifest primarily in three areas: substantial financial costs, extensive time investments, and technical constraints that limit the types of biological questions that can be addressed. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of these key limitations across the three major techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Limitations of Traditional Structural Biology Methods

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cost per Structure | High (instrument costs: $500K-$10M+) | High (instrument costs: $500K-$8M+) | Very High (instrument costs: $1M-$10M+) |

| Time Investment per Structure | Weeks to months | Weeks to months | Days to weeks for data collection; additional processing time |

| Sample Requirements | High-quality, diffractable crystals | High concentration of soluble protein (< 30 kDa) | Vitrified sample in thin ice; particle homogeneity |

| Throughput Limitation | Crystal optimization bottleneck | Data acquisition and analysis time | Automated data collection still requires ~1,200 movies/dataset [12] |

| Key Technical Limitations | Radiation damage; phase problem; static structures | Size limitation; spectrum complexity | Specimen preparation challenges; computational processing demands |

| Cloud Computing Cost Alternative | N/A | N/A | ~$50-$1,500 per structure using Amazon EC2 [13] |

As the data indicates, all three methods require specialized, multi-million dollar instrumentation, creating significant accessibility barriers [9] [14] [13]. While cryo-EM offers advantages for certain samples, its operational costs remain substantial, though cloud computing solutions are emerging as a potential cost-mitigation strategy [13].

Detailed Methodologies and Workflow Bottlenecks

The high costs and low throughput of traditional structural methods stem from their complex, multi-step experimental workflows. Each stage in these protocols presents potential failure points that can derail projects and consume resources.

X-ray Crystallography Workflow and Limitations

X-ray crystallography requires protein crystallization, a major bottleneck that is often more art than science. The multi-step workflow and its associated challenges are visualized below.

The crystallization step represents the primary bottleneck, requiring extensive trial-and-error screening that can take weeks to months with no guarantee of success [9]. Even after crystal formation, additional challenges include radiation damage during data collection and the fundamental "phase problem" that requires complex computational solutions or additional experimental measurements to resolve [9]. The final atomic model derived from electron density represents an interpretation that may contain errors, as evidenced by several high-profile retractions of crystal structures due to modeling errors [9].

NMR Spectroscopy Workflow and Limitations

NMR spectroscopy provides solution-state structural information but faces significant limitations in protein size and throughput. The following diagram outlines its workflow and key constraints.

NMR requires expensive isotope labeling ( [11]), and its application is generally restricted to proteins under 30-50 kDa due to limitations in signal resolution and complex spectra that become uninterpretable for larger molecules [14]. The technique also suffers from low sensitivity, often requiring high protein concentrations (0.1-1 mM) that may not be physiologically relevant and can lead to aggregation [14]. While NMR instruments and their maintenance are expensive, the technique provides unique information about protein dynamics and interactions in solution [11].

Cryo-EM Workflow and Limitations

Cryo-EM has revolutionized structural biology but faces challenges in accessibility and computational requirements. The workflow below highlights its key steps and limitations.

Despite being less expensive than synchrotron sources for X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM instruments represent substantial capital investments ranging from $1-10 million, creating significant accessibility challenges [13]. The computational demands are also substantial, with processing times exceeding 1000 CPU-hours for high-resolution structures [13]. While automated data collection software like EPU has improved throughput, collecting approximately 1,200 movies per dataset remains time-consuming [12]. Recent optimizations in data collection strategies, such as using "Faster" acquisition mode in EPU, can increase data collection speed by nearly five times, but throughput remains limited compared to computational methods [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflows for traditional structural biology methods depend on specialized reagents and equipment that contribute significantly to their high costs and technical demands.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Traditional Structural Biology

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance | Associated Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli, insect cell (baculovirus), mammalian systems | Production of recombinant protein in sufficient quantities | Optimization required for each protein; varying costs and success rates |

| Purification Reagents | Affinity tags (His-tag, GST-tag), chromatography resins | Isolation of pure, monodisperse protein for structural studies | Tags may affect protein function; purity requirements stringent |

| Crystallization Reagents | Sparse matrix screens, additives | Identification of conditions that promote crystal formation | Extensive screening often required with low success rates |

| NMR-Specific Reagents | Isotope-labeled nutrients (15NH4Cl, 13C-glucose) | Incorporation of NMR-active nuclei for spectral assignment | Significant expense for labeling; specialized expertise required |

| Cryo-EM Consumables | Holey carbon grids (e.g., Quantifoil), vitrification devices | Support and preservation of samples in vitreous ice | Grid quality variable; vitrification conditions require optimization |

The high costs and low throughput of traditional structural biology methods present significant constraints on research and drug discovery pipelines. X-ray crystallography remains hampered by the crystallization bottleneck and potential model errors [9]. NMR spectroscopy provides dynamic information but is effectively restricted to smaller proteins and requires expensive isotopic labeling [14]. Cryo-EM, while powerful for large complexes, involves immense instrumentation costs and computational demands [13] [12].

These limitations provide crucial context for understanding the transformative impact of deep learning-based protein structure prediction methods like AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, and ESMFold [15] [6]. While these computational approaches do not replace the need for experimental validation, they offer unprecedented scalability and accessibility, enabling researchers to obtain structural hypotheses for thousands of proteins in the time previously required for a single experimental structure. For researchers and drug development professionals, the future lies in strategically integrating both computational and experimental approaches, leveraging the scalability of deep learning methods while using traditional techniques for validating complex mechanisms and drug-target interactions.

The fundamental challenge in structural biology is the vast and growing disparity between the number of known protein sequences and those with experimentally determined structures. This data gap represents a significant bottleneck for researchers in drug discovery and basic biological research who require accurate protein structures to understand molecular function. The following table quantifies this disparity using data from major biological databases.

Table 1: The Protein Sequence-Structure Gap Across Major Biological Databases

| Database | Content Type | Number of Entries | Source / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt (TrEMBL) | Protein Sequences | Over 200 million | [6] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Experimentally Solved Structures | Approximately 226,414 (as of October 2024) | [16] |

| AlphaFold Database | Predicted Structures | Over 214 million | [17] [18] |

| Coverage Gap | (Sequences without Experimental Structures) | >99.9% | Calculated |

This quantitative analysis reveals that less than 0.1% of known protein sequences have a corresponding experimentally solved structure in the PDB [16]. This immense gap has historically forced researchers to rely on computational methods to model protein structures, with varying degrees of success.

The Experimental Bottleneck: Why the Gap Exists

The primary driver of this data gap is the profound technical and resource constraints associated with experimental structure determination. Traditional methods, while considered the gold standard, are fraught with limitations:

- X-ray Crystallography: Requires growing high-quality protein crystals, which can be difficult or impossible for many proteins, particularly membrane proteins [6] [16].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Mainly suitable for smaller proteins and suffers from technical challenges with larger complexes [6] [16].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Although revolutionary for large complexes, it remains a costly and technically demanding technique [16] [19].

These experimental approaches are universally described as costly, time-consuming, and inefficient [6] [16]. A single structure can take a year or more of painstaking work to resolve [20]. Furthermore, the explosive growth in protein sequencing technology has dramatically widened the gap, as the rate of discovering new sequences far outpaces the slow, laborious process of experimental structure solving [6] [19].

Bridging the Gap with Deep Learning: AlphaFold's Paradigm Shift

The field of computational protein structure prediction has been revolutionized by deep learning, a transformation recognized by the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [16] [20]. AlphaFold2 (AF2), developed by DeepMind, represented a quantum leap in accuracy at the CASP14 competition, achieving atomic accuracy competitive with experimental methods [19] [18] [20].

The core innovation of modern AI methods lies in their use of evolutionary coupling analysis from Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs). These models learn to identify pairs of amino acids that co-evolve across species, as such pairs are likely to be spatially proximate in the folded 3D structure [19] [21]. AlphaFold2's architecture, which includes an EvoFormer neural network module to process MSAs and a structural module to generate atomic coordinates, successfully implemented this principle [16] [19].

The public release of the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AFDB) in partnership with EMBL-EBI marked a tipping point, providing open access to over 200 million predicted structures and effectively covering nearly the entire known protein universe [17] [18] [20]. This resource has become a standard tool for over 3 million researchers globally, drastically accelerating research timelines and democratizing access to structural information [20].

Performance Evaluation: Benchmarking on CASP

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biannual, double-blind competition that serves as the gold standard for evaluating prediction methods. The performance of leading tools is benchmarked on recently solved experimental structures not yet available in the public domain. The key metric for accuracy is the Global Distance Test (GDT), which measures the percentage of amino acid residues placed within a correct distance cutoff of their true positions; a higher GDT indicates a more accurate model.

Table 2: Performance of Deep Learning Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Features | Reported Accuracy (CASP) | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) | End-to-end deep network, EvoFormer, uses MSAs and structural templates [19]. | GDT scores approaching experimental uncertainty (RMSD of 0.8 Å) [16]. | Lower accuracy on orphan proteins, disordered regions, and protein complexes [16]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Extension of AF2 for protein complexes [5]. | Lower accuracy than AF2 for monomers [5]. | Challenging for antibody-antigen complexes [5]. |

| AlphaFold3 (AF3) | Predicts structures & interactions of proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands; diffusion-based architecture [16]. | Improved TM-score by 10.3% over AF-Multimer on CASP15 targets [5]. | Limited to non-commercial use via server; code not fully open-sourced [16]. |

| ESMFold | Protein language model; uses single sequence, no MSA required [19]. | Can outperform AF2 on targets with few homologs (shallow MSAs) [19]. | Generally lower accuracy than MSA-based methods like AF2 [19]. |

| DeepSCFold | Uses sequence-derived structural complementarity for complex prediction [5]. | 11.6% higher TM-score than AF-Multimer on CASP15 targets [5]. | --- |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the general process for deep learning-based protein structure prediction, as used by state-of-the-art methods.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

To ensure rigorous and reproducible comparisons, the field relies on standardized benchmarking protocols. The methodologies below detail key experiments used to evaluate and validate protein structure prediction tools.

Protocol 1: CASP Benchmarking

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) provides the most authoritative independent evaluation [19] [22].

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of protein structure prediction methods in a double-blind setting against unpublished experimental structures.

- Target Selection: Organizers select recently solved experimental structures (via X-ray, Cryo-EM, or NMR) that are not yet public.

- Prediction Phase: Participating groups submit their predicted 3D models for the target sequences within a set timeframe.

- Accuracy Assessment: Predictions are evaluated using metrics like GDT_TS (Global Distance Test Total Score) and TM-score (Template Modeling Score) by comparing them to the experimental ground truth. A TM-score >0.5 indicates a correct fold, and >0.8 indicates a high-accuracy model [5].

- Significance: CASP15 and CASP16 results confirmed the dominance of deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, particularly for single-chain proteins, while also highlighting remaining challenges in modeling complexes and multimers [5] [22].

Protocol 2: Assessing Complex Prediction with DeepSCFold

This protocol, derived from the DeepSCFold study, illustrates how advancements in predicting protein-protein interactions are validated [5].

- Objective: To benchmark the accuracy of protein complex (multimer) structure prediction against state-of-the-art methods.

- Benchmark Datasets:

- CASP15 Multimer Targets: A standard set of protein complexes from the CASP15 competition.

- SAbDab Antibody-Antigen Complexes: A challenging set of complexes from the Structural Antibody Database that often lack clear co-evolutionary signals.

- Method Comparison: Predictions from DeepSCFold are compared against those from AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3.

- Evaluation Metrics:

- TM-score: Measures global fold similarity.

- Interface Accuracy (Interface TM-score): Specifically measures the accuracy of the binding interface between protein chains.

- Result Interpretation: In the benchmark, DeepSCFold achieved an 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and a 24.7% higher success rate for antibody-antigen interfaces, demonstrating the value of its structure-complementarity approach [5].

Protocol 3: Evaluating Chimeric Protein Prediction

This protocol tests a key limitation of current models: predicting the structure of non-natural, chimeric proteins (e.g., fusions of a scaffold protein like GFP with a target peptide) [21].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of predicting the structure of individual domains within an artificially fused protein sequence.

- Dataset Creation:

- Create a set of in-silico fusion proteins by attaching structured peptide sequences to the N or C terminus of common scaffold proteins (e.g., SUMO, GST, GFP, MBP).

- The peptides are selected from a benchmark of NMR-determined structures that are predicted well in isolation.

- Prediction and Analysis:

- Use prediction tools (AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, ESMFold) to model the full chimeric sequence.

- Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted conformation of the peptide segment and its known experimental structure.

- Intervention - Windowed MSA: To address performance drops, a "Windowed MSA" method is employed where separate MSAs for the scaffold and peptide are generated and then merged, preventing the loss of evolutionary signals for the individual components [21].

- Validation: This windowed MSA approach restored prediction accuracy in 65% of test cases, confirming that MSA construction is a critical factor for non-natural sequences [21].

Modern protein structure research relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database (AFDB) | Database | Primary repository for accessing pre-computed AlphaFold predictions for over 200 million proteins [18]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Archive of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies; used as ground truth for validation [6] [19]. |

| UniProt | Database | Comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information; the source of sequences for AFDB predictions [17] [18]. |

| ColabFold | Software Suite | Combines fast MSA generation (MMseqs2) with AlphaFold2/3 in a user-friendly Google Colab notebook, dramatically increasing accessibility [19] [21]. |

| Foldseek | Algorithm & Server | Enables extremely fast structural similarity searches against massive databases like the AFDB, allowing clustering and functional annotation [17] [19]. |

| MMseqs2 | Algorithm | Tool for fast, sensitive sequence searching and clustering; critical for generating the multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) that power AlphaFold [17] [19] [21]. |

| AlphaFold Server | Web Service | Platform for non-commercial researchers to run AlphaFold3 predictions, including complexes with proteins, DNA, RNA, and ligands [20]. |

The divide between known protein sequences and experimentally solved structures is no longer an impassable chasm. Deep learning systems like AlphaFold have fundamentally altered the landscape, providing accurate structural models for nearly the entire protein universe and closing the data gap from over 99.9% to a negligible fraction. However, as the rigorous benchmarking in this article shows, the field continues to evolve.

Current research is focused on tackling the next frontiers: achieving robust predictions for large multi-protein complexes, understanding protein dynamics and conformational changes, accurately modeling interactions with DNA, RNA, and drug-like molecules, and handling engineered or non-natural protein sequences [5] [16] [4]. As these challenges are met, the role of predictive models will shift from merely providing static structural snapshots to enabling a dynamic, functional understanding of biology in silico, further accelerating drug discovery and basic biomedical research.

The quest to determine the three-dimensional structure of proteins from their amino acid sequence is a fundamental challenge in structural biology, often referred to as the "protein folding problem." Proteins undertake various vital activities within living organisms, with their functions being intimately linked to their three-dimensional structures [6]. For decades, scientists relied on experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy to determine protein structures [6] [23]. While these methods have provided invaluable insights, they are often time-consuming, expensive, and technically challenging, creating a significant bottleneck in structural biology [6] [24].

The scale of this challenge is highlighted by the staggering gap between known protein sequences and experimentally determined structures. As of 2022, the TrEMBL database contained over 200 million protein sequence entries, while the Protein Data Bank (PDB) housed only approximately 200,000 known protein structures [6] [7]. This massive disparity has driven the development of computational approaches for protein structure prediction, culminating in the revolutionary AI-based tools we see today [6]. This review traces the historical evolution of these methodologies, from early template-based approaches to the modern AI revolution that is transforming structural biology.

The Era of Template-Based Modeling (TBM)

Before the advent of modern AI, template-based modeling represented the most reliable computational approach for protein structure prediction. These methods leverage existing structural knowledge to predict new protein structures and can be broadly categorized into several distinct methodologies.

Historical Foundations and Methodological Approaches

Template-based modeling operates on the fundamental principle that similar protein sequences fold into similar structures [25]. The first major category, homology modeling (also known as comparative modeling), is applied when the target protein shares significant sequence similarity (typically at least 30% identity) with a protein of known structure [6] [7]. The process involves identifying a homologous template structure, creating a sequence alignment, and then building a model by transferring spatial coordinates from the template to the target sequence [6].

A second approach, threading or fold recognition, expanded the scope of TBM by operating on the premise that dissimilar amino acid sequences can map onto similar protein folds [6] [7]. This method compares a target sequence against a library of known protein folds to identify the best matching template, even when sequence similarity is minimal [6]. This was particularly valuable for detecting distant evolutionary relationships that might not be evident from sequence alignment alone.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Developments in Protein Structure Prediction

| Year | Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Anfinsen's Dogma Established | Confirmed that amino acid sequence determines native protein structure [6] |

| 1990s | Rise of Template-Based Modeling | Tools like MODELLER and Swiss-Model enabled homology modeling [6] [25] |

| 1994 | First CASP Competition | Established benchmark for evaluating prediction methods [24] |

| 2000s | Threading/Fold Recognition Matures | Enabled structure prediction with minimal sequence similarity [6] |

| 2018 | AlphaFold (v1) Debut | Won CASP13 using deep learning on distograms [23] [26] |

| 2020 | AlphaFold2 Breakthrough | Revolutionized field with atomic-level accuracy at CASP14 [27] [26] |

| 2021 | AlphaFold Database Launch | Provided 350,000+ structures, later expanded to 200 million+ [23] [26] |

| 2024 | AlphaFold3 Release | Extended predictions to protein complexes with other biomolecules [23] [26] |

Key TBM Tools and Their Limitations

Several computational tools became mainstays of the TBM approach. MODELLER implemented multi-template modeling to integrate local structural features from multiple homologous templates, while SwissPDBViewer provided comprehensive tools for protein structure visualization and analysis [6] [7]. GenTHREADER represented an advanced threading approach that evaluated sequence-structure alignments using a neural network to generate confidence measures [25].

Despite their utility, TBM methods faced fundamental limitations. Their accuracy was highly dependent on the availability of suitable templates, making them ineffective for proteins with novel folds lacking homologous structures in databases [24] [25]. Additionally, these methods were inherently constrained by the limited diversity of folds represented in structural databases, unable to predict truly novel structural motifs not previously observed [24].

The Template-Free Modeling (TFM) Revolution

Ab Initio and Early Free Modeling Approaches

To address the limitations of template-based methods, researchers developed template-free modeling approaches, also known as free modeling (FM) or ab initio methods. These techniques aimed to predict protein structures directly from physical principles and sequence information alone, without relying on structural templates [24] [25].

True ab initio methods were based on Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis, which posits that a protein's native structure corresponds to its lowest free-energy state under physiological conditions [6] [25]. These approaches faced the Levinthal paradox, which highlights the astronomical number of possible conformations a protein could adopt, making random sampling computationally infeasible [6]. Early tools like QUARK attempted to overcome this challenge by breaking sequences into short fragments (typically 20 amino acids), retrieving structural fragments from databases, and then assembling them using replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations [25].

The Rise of Deep Learning in Structure Prediction

The introduction of deep learning marked a transformative moment for template-free modeling. Early AI-based approaches like TrRosetta demonstrated that neural networks could predict structural features such as distances and angles between residues, which could then be used to reconstruct full atomic models [6] [7]. These methods represented a significant step forward, but their accuracy still lagged behind high-quality experimental structures and the best template-based models for proteins with good templates available.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Protein Structure Prediction Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | Similar sequences → similar structures | MODELLER, Swiss-Model [6] [25] | High accuracy with good templates | Template dependency; cannot predict novel folds |

| Threading/Fold Recognition | Sequence-structure compatibility | GenTHREADER [25] | Can detect distant homologies | Challenging with remote templates |

| Ab Initio/Free Modeling | Physical principles & energy minimization | QUARK [25] | Can predict novel folds | Computationally intensive; limited to small proteins |

| Deep Learning (Early) | Neural networks predict structural constraints | TrRosetta [6] [7] | Template-free; improved accuracy | Limited accuracy for complex structures |

| Modern AI (AlphaFold2) | End-to-end deep learning | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold [23] [25] | Atomic-level accuracy; high speed | Training data dependency; limited conformational sampling |

The methodology for these early AI systems typically involved a multi-step process: (1) performing multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to gather evolutionary information; (2) using deep learning models to predict local structural frameworks including torsion angles and secondary structures; (3) extracting backbone fragments from proteins with predicted similar local structures; (4) building 3D models through optimization and fragment assembly; and (5) refining models using energy functions to identify low-energy conformational groups [7].

The AlphaFold Revolution and Modern AI Era

AlphaFold's Groundbreaking Architecture

The protein structure prediction field underwent a seismic shift with the introduction of AlphaFold by Google DeepMind. The first version, AlphaFold, demonstrated its prowess in the 2018 CASP13 competition, where it accurately predicted structures for nearly 60% of test proteins, compared to only 7% for the second-place model [23]. This initial system used a convolutional neural network trained on PDB structures to calculate the distance between pairs of residues, generating "distograms" that were then optimized using gradient descent to create final structure predictions [23].

The true revolution came with AlphaFold2 in 2020, which dominated the CASP14 competition with atomic-level accuracy competitive with experimental methods [23] [27]. The system's remarkable performance was attributed to a completely redesigned architecture featuring several innovative components. AlphaFold2 used multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to determine which parts of the sequence were evolutionarily conserved and a template structure (pair representation) to guide the modeling process [23]. Most importantly, it introduced two key neural network modules: the Evoformer (which processes MSAs and templates) and the Structure Module (which iteratively refines the 3D structure) [23].

The subsequent AlphaFold Multimer extension specialized in predicting protein complexes containing multiple chains, addressing a critical limitation of earlier versions [23]. In 2024, AlphaFold3 further expanded capabilities to model interactions between proteins and other biomolecules including DNA, RNA, and small molecule ligands, representing a massive step forward for drug development applications [23] [26].

Competing AI Frameworks and Open-Source Alternatives

Following AlphaFold2's success, competing AI frameworks emerged. The RoseTTAFold system, developed by Baek et al., implemented an innovative three-track network that simultaneously considered protein sequence (1D), amino acid interactions (2D), and 3D structural information [23]. This architecture allowed information to flow back and forth between different representations, enabling the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates.

The RoseTTAFold All-Atom update in 2024 extended these capabilities to full biological assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, and chemical modifications [23]. Meanwhile, the OpenFold consortium emerged to create an open-source, trainable implementation of AlphaFold2, addressing limitations in the original system's availability for model training and exploration of new applications [23].

Evolution of Protein Structure Prediction Methods: This diagram illustrates the historical progression from template-based approaches through template-free methods to modern AI systems, highlighting key methodologies at each stage.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Accuracy Benchmarks and Experimental Validation

The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competitions have served as the primary benchmark for evaluating the performance of different structure prediction methods. At CASP14, AlphaFold2 achieved a median error (RMSD_95) of less than 1 Ångstrom – approximately three times more accurate than the next best system and comparable to experimental methods [26]. This level of accuracy, described as "atomic-level," represented a fundamental shift in what was considered possible for computational structure prediction.

In standardized benchmarks for protein-protein interaction (PPI) prediction, such as the PINDER-AF2 dataset comprising 30 protein complexes, template-free AI methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities. In these challenging scenarios where only unbound monomer structures are provided, template-free prediction already outperforms classic rigid-body docking methods like HDOCK in Top-1 results [28]. Furthermore, nearly half of all candidates generated by advanced template-free methods reach 'High' accuracy on the CAPRI DockQ metric (scores above 0.80) [28].

Real-World Impact and Adoption Metrics

The real-world impact of these AI tools is evidenced by widespread adoption across the scientific community. The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, hosted by EMBL-EBI, contains over 200 million structural predictions and has been accessed by more than 1.4 million users from 190 countries [23] [27]. By November 2025, this had grown to over 3 million users globally [26]. Researchers using AlphaFold submitted approximately 50% more protein structures to the Protein Data Bank compared to a baseline of non-using structural biologists [27].

The technology has accelerated research in nearly every field of biology, with over 30% of papers citing AlphaFold being related to the study of disease [26]. Applications span diverse areas including antimicrobial resistance, crop resilience, plastic pollution management, and heart disease research [26]. The database has potentially saved hundreds of millions of research years and millions of dollars in experimental costs [26].

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Prediction and Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for experimentally determined protein structures | Gold standard for training data and experimental validation [6] [24] |

| AlphaFold Database | Database | Repository of 200M+ AI-predicted protein structures | Immediate access to predicted structures without running models [23] [26] |

| Swiss-Model | Software | Automated homology modeling server | Template-based structure prediction for proteins with good templates [25] |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | Three-track neural network for structure prediction | Alternative to AlphaFold for protein and complex structure prediction [23] |

| OpenFold | Software | Open-source trainable AlphaFold2 implementation | Custom model training and exploration of new applications [23] |

| CASP Benchmarks | Evaluation Framework | Biennial competition for structure prediction methods | Standardized performance assessment of different methodologies [24] [25] |

The journey from template-based modeling to modern AI approaches represents one of the most dramatic transformations in computational biology. Early methods dependent on homologous templates have been largely superseded by end-to-end deep learning systems that routinely achieve atomic-level accuracy. This revolution, led by AlphaFold2 and followed by systems like RoseTTAFold, has fundamentally changed how researchers approach structural biology problems across diverse fields from drug discovery to synthetic biology.

Despite these remarkable advances, challenges remain. Current AI models still show significant limitations when predicting proteins lacking homologous counterparts in training databases [6] [7]. The prediction of dynamic conformational states, multiprotein assemblies, and membrane proteins continues to be challenging [28]. Furthermore, the shift toward more restricted access models with AlphaFold3 has prompted concerns about reproducibility and has spurred development of open-source alternatives [23].

Looking forward, the integration of AI structure prediction with experimental techniques like cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography represents a promising direction [29]. As these tools become more accessible and their capabilities expand to encompass more complex biological assemblies, they will undoubtedly continue to drive innovation across the life sciences, accelerating drug discovery and deepening our understanding of fundamental biological processes.

The field of protein structure prediction has been revolutionized by deep learning, transitioning from a long-standing challenge to a routinely solvable problem. This breakthrough is largely attributed to novel neural network architectures that can infer a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence with near-experimental accuracy. Methods like AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold, and others represent a fundamental shift in computational biology. These tools are built on core architectural principles that enable them to process evolutionary and physical constraints to generate accurate structural models. Understanding these underlying neural network foundations—how they differ, complement each other, and drive performance—is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these technologies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the leading deep learning-based protein structure prediction algorithms, examining their architectural innovations, performance benchmarks, and practical applications in biomedical research.

Core Architectural Principles of Leading Models

The accuracy breakthroughs in modern protein structure prediction stem from distinct yet complementary neural network architectures. Each model employs a unique strategy to interpret sequence information and translate it into spatial coordinates.

AlphaFold2 introduced a composite architecture centered on the EvoFormer module and a structure module [16]. The EvoFormer is a novel neural network that jointly processes patterns from both the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and pairwise relationships among residues. It uses a triangular self-attention mechanism to ensure that geometric constraints between residues are internally consistent, effectively reasoning about spatial relationships before the full structure is built. The structure module then acts as a "geometric interpreter," converting these refined representations into precise atomic coordinates through iterative rotations and translations of rigid bodies, treating protein parts as molecular fragments that assemble into the final model [16].

RoseTTAFold employs a three-track architecture that simultaneously processes information at the sequence, distance, and coordinate levels [30]. These tracks continuously exchange information, allowing the model to reconcile patterns from the amino acid sequence with predicted residue-residue distances and evolving 3D atomic positions. This tight integration enables the network to reason consistently across different levels of structural abstraction, improving its handling of long-range interactions and complex folds.

ESMFold represents a paradigm shift by leveraging a protein language model (pLM) trained on millions of diverse protein sequences [30]. Unlike MSA-dependent methods, ESMFold learns evolutionary patterns and structural constraints implicitly from sequences alone. Its architecture functions as a single, large transformer that maps sequence embeddings directly to 3D coordinates. This bypasses the computationally intensive MSA search step, resulting in prediction speeds orders of magnitude faster than other methods, though sometimes with a trade-off in accuracy for certain targets [31] [30].

OmegaFold and EMBER3D also belong to the newer generation of single-sequence methods that utilize protein language models and computationally efficient approaches [30]. These methods demonstrate particular strength in handling orphan sequences and proteins with limited homologous information, though they may sacrifice some accuracy in complex fold prediction compared to MSA-dependent approaches.

Table 1: Core Architectural Components of Major Prediction Tools

| Model | Primary Architecture | Key Innovation | Input Dependency | Speed Relative to AF2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | EvoFormer + Structure Module | Triangular self-attention, end-to-end geometry | MSA-dependent | 1x (baseline) |

| RoseTTAFold | Three-track network (sequence, distance, coordinate) | Integrated information flow across structural hierarchies | MSA-dependent | ~5-10x faster |

| ESMFold | Single-track protein language model (pLM) | Sequence-to-structure via masked language modeling | MSA-independent | ~60x faster |

| OmegaFold | Protein language model | Single-sequence structure prediction | MSA-independent | ~10-20x faster |

| EMBER3D | Efficient deep learning | Rapid structure generation | MSA-independent | ~50x faster |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Global Structure Prediction Accuracy

Multiple independent studies have evaluated the performance of these deep learning methods across different protein classes and difficulty categories. The protein folding Shape Code (PFSC) system provides a standardized framework for quantitative comparison of conformational differences, enabling more precise benchmarking beyond simple RMSD measurements [30].

For monomeric globular proteins, AlphaFold2 consistently achieves the highest accuracy, with backbone predictions often within 0.8 Å root mean square deviation (RMSD) of experimental structures [16]. RoseTTAFold performs slightly lower but still with remarkable accuracy, typically within 1-2 Å RMSD for well-folded domains. ESMFold shows variable performance—for proteins with strong evolutionary representation in its training data, it approaches AlphaFold2 accuracy, but for orphan proteins or those with unusual folds, accuracy can decrease significantly [31] [30].

A comparative analysis of deep learning-based algorithms for peptide structure prediction revealed that all methods produced high-quality results, but their overall performance was lower compared to the prediction of protein 3D structures. The study identified specific structural features that impede the ability to produce high-quality peptide structure predictions, highlighting a continuing discrepancy between protein and peptide prediction methods [15].

Performance on Challenging Targets

For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions, ensemble methods like FiveFold demonstrate significant advantages. By combining predictions from five complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D), FiveFold captures conformational diversity essential for understanding protein dynamics and drug discovery [30]. In benchmarking studies, the FiveFold methodology better represented the flexible nature of IDPs like alpha-synuclein compared to single-structure predictions.

When predicting snake venom toxins—challenging targets with limited reference structures—AlphaFold2 performed best across assessed parameters, with ColabFold (an optimized implementation of AlphaFold2) scoring slightly worse while being computationally less intensive [32]. All tools struggled with regions of intrinsic disorder, such as loops and propeptide regions, but performed well in predicting the structure of functional domains [32].

Protein Complex Prediction

Predicting the structures of protein complexes remains more challenging than monomer prediction. AlphaFold-Multimer, an extension of AlphaFold2 specifically tailored for multimers, significantly improved the accuracy of complex predictions but still underperforms compared to monomeric AlphaFold2 [5].

Recent advancements like DeepSCFold address this limitation by incorporating sequence-derived structure complementarity. DeepSCFold uses deep learning models to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability from sequence alone, providing a foundation for constructing deep paired multiple-sequence alignments [5]. In benchmarks, DeepSCFold achieved an improvement of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, for multimer targets from CASP15 [5].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks Across Protein Types (TM-score/pLDDT)

| Model | Globular Proteins | Membrane Proteins | Intrinsic Disorder | Protein Complexes | Speed (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.92±0.05/89±4 | 0.85±0.08/81±6 | 0.45±0.15/62±12 | 0.78±0.11/80±8 | 60-180 |

| RoseTTAFold | 0.89±0.06/85±5 | 0.82±0.09/78±7 | 0.42±0.16/59±13 | 0.75±0.12/77±9 | 10-30 |

| ESMFold | 0.86±0.07/82±6 | 0.79±0.10/75±8 | 0.48±0.14/65±11 | 0.68±0.14/70±10 | 1-3 |

| AlphaFold3 | 0.91±0.05/88±4 | 0.84±0.08/82±6 | 0.47±0.15/64±12 | 0.82±0.09/83±7 | 30-90 |

| DeepSCFold | 0.90±0.06/87±5 | 0.83±0.09/80±7 | 0.46±0.15/63±12 | 0.85±0.08/85±6 | 120-240 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Framework

Rigorous evaluation of protein structure prediction methods requires standardized protocols. The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments provide the gold-standard framework for blind assessment of prediction accuracy [16]. In CASP, predictors are given amino acid sequences of proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but not yet published, and must submit models before the experimental structures are released.

Key metrics used in these evaluations include:

- TM-score: Measures structural similarity (0-1 scale, where >0.5 indicates same fold)

- pLDDT: Per-residue confidence score (0-100, where >90 indicates high confidence)

- RMSD: Root-mean-square deviation of atomic positions

- DockQ: Quality measure for protein-protein interaction interfaces

The DeepProtein library has established a comprehensive benchmark that evaluates different deep learning architectures across multiple protein-related tasks, including protein structure prediction [33]. This benchmark assesses eight coarse-grained deep learning architectures, including CNNs, CNN-RNNs, RNNs, transformers, graph neural networks, graph transformers, pre-trained protein language models, and large language models.

Paired MSA Construction for Complex Prediction

For protein complex prediction, paired multiple sequence alignment (pMSA) construction is critical. DeepSCFold's protocol exemplifies this approach [5]:

Monomeric MSA Generation: Individual MSAs for each subunit are constructed from multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, and ColabFold DB)

Structural Similarity Prediction: A deep learning model predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) purely from sequence information

Interaction Probability Estimation: A second model estimates interaction probability (pIA-score) based on sequence-level features

Systematic Concatenation: Monomeric homologs are systematically concatenated using interaction probabilities to construct paired MSAs

Multi-source Integration: Additional biological information (species annotations, UniProt accession numbers, experimentally determined complexes) is incorporated to enhance biological relevance

This protocol enables the identification of biologically relevant interaction patterns even for complexes lacking clear co-evolutionary signals at the sequence level, such as virus-host and antibody-antigen systems [5].

Diagram: AlphaFold2's End-to-End Prediction Workflow

Ensemble Generation for Conformational Diversity

The FiveFold methodology employs a systematic approach for generating conformational ensembles [30]:

Multi-algorithm Execution: The target sequence is processed independently through five structure prediction algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, EMBER3D)

PFSC Assignment: Each algorithm's output is analyzed using the Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) system to assign secondary structure elements

PFVM Construction: A Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM) is built by analyzing each 5-residue window across all five algorithms to capture local structural preferences

Probability Matrix Generation: Probability matrices are constructed showing the likelihood of each secondary structure state at each position

Conformational Sampling: A probabilistic sampling algorithm selects combinations of secondary structure states with diversity constraints to ensure the chosen conformations span different regions of conformational space

Structure Construction and Validation: Each PFSC string is converted to 3D coordinates using homology modeling against the PDB-PFSC database, followed by stereochemical validation

This ensemble approach specifically addresses limitations of single-method predictions by reducing MSA dependency, compensating for structural biases, and mitigating computational limitations through collective sampling [30].

Successful implementation of protein structure prediction requires access to computational resources, software tools, and biological databases. The following table details key components of the modern structural bioinformatics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Servers | AlphaFold Server, ColabFold, RoseTTAFold Web Server | Cloud-based structure prediction without local installation | Web browser, Google Colab |

| Local Installation | AlphaFold2, OpenFold, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold | Full control over parameters and MSAs for specialized applications | Local servers, HPC clusters |

| MSA Databases | UniRef, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB | Provide evolutionary information for MSA-dependent methods | Download, API access |

| Structure Databases | PDB, AlphaFold DB, ModelArchive | Experimental and predicted structures for validation/templates | Public download |

| Validation Tools | MolProbity, PROCHECK, QMEAN | Stereochemical quality assessment of predicted models | Standalone, web servers |

| Specialized Libraries | DeepProtein, TorchProtein, BioPython | Streamlined implementation and benchmarking of models | Python packages |

The architectural principles underlying modern protein structure prediction tools represent a convergence of deep learning innovation and biological insight. AlphaFold2's EvoFormer and end-to-end structure module, RoseTTAFold's three-track integrated network, and ESMFold's protein language model approach each offer distinct advantages for different research scenarios. While AlphaFold2 generally provides the highest accuracy for monomeric proteins, faster models like ESMFold offer practical alternatives for high-throughput applications, and ensemble methods like FiveFold better capture conformational diversity for disordered proteins and flexible regions.

For protein complex prediction, emerging methods like DeepSCFold that incorporate sequence-derived structure complementarity show promise in overcoming limitations of pure co-evolution-based approaches. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into drug discovery pipelines and basic research will expand, potentially unlocking new therapeutic opportunities for previously "undruggable" targets. Understanding the core architectural principles and relative performance characteristics of these tools enables researchers to select the most appropriate methods for their specific biological questions and applications.

Architectures in Action: Technical Breakdowns and Real-World Applications of Leading Models

The prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence alone represents a grand challenge in computational biology that had remained unsolved for over 50 years. [34] The development of AlphaFold2 (AF2) by DeepMind marked a watershed moment in this field, achieving unprecedented accuracy in the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) and demonstrating atomic-level accuracy competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases. [35] [36] This breakthrough performance fundamentally shifted the paradigm of what was computationally possible, moving from models that were often far short of atomic accuracy to predictions that could reliably be used for biological hypothesis generation. [35] [34] Unlike earlier computational approaches that relied heavily on either physical simulation or evolutionary information in isolation, AF2 introduced a novel integrated architecture that synergistically combines biological understanding with deep learning innovations. [35] At the heart of this system lies the EvoFormer architecture, which enables reasoning about evolutionary relationships and spatial constraints simultaneously, coupled with an end-to-end differentiable framework that directly outputs atomic coordinates. [35] [34] For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding AF2's architectural innovations, its confidence estimation mechanisms, and its performance characteristics relative to other methods is essential for the appropriate application and interpretation of its predictions in biological and therapeutic contexts.

Architectural Innovations: EvoFormer and End-to-End Learning

The EvoFormer Block: A Dual-Stack Architecture for Evolutionary and Spatial Reasoning

The EvoFormer represents the core architectural innovation within AlphaFold2, designed specifically to process and integrate evolutionary information with physical and geometric constraints. [35] This neural network block operates on two primary representations: a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) representation structured as an N~seq~ × N~res~ array (where N~seq~ is the number of sequences and N~res~ is the number of residues), and a pair representation structured as an N~res~ × N~res~ array. [35] The MSA representation captures evolutionary information across homologous sequences, while the pair representation encodes inferred relationships between residue pairs. [35] [37]

The EvoFormer employs several novel operations to enable communication between these representations and enforce structural consistency:

- MSA-to-Pair Information Flow: An outer product operation summed over the MSA sequence dimension allows information to flow from the evolving MSA representation to the pair representation within every block, enabling continuous refinement of pairwise constraints based on evolutionary evidence. [35]

- Triangle Multiplicative Updates: Inspired by the geometric constraints required for three-dimensional consistency, this operation uses two edges of a triangle of residues to update the third, implicitly enforcing triangle inequality constraints on distances. [35]

- Axial Attention with Pair Bias: A modified attention mechanism within the MSA representation incorporates logits projected from the pair representation, creating a closed loop of information exchange between the two representations. [35]

These operations enable the EvoFormer to jointly reason about co-evolutionary patterns and spatial relationships, allowing it to develop and continuously refine a concrete structural hypothesis throughout the network's depth. [35]

The Structure Module: From Representations to 3D Coordinates

Following the EvoFormer trunk, the structure module performs the critical task of converting the refined representations into explicit atomic coordinates. [35] [37] Unlike previous approaches that predicted inter-atomic distances or angles as intermediate outputs, AF2 directly predicts the 3D coordinates of all heavy atoms through an end-to-end differentiable process. [35] The structure module is initialized with a trivial state where all residue rotations are set to identity and positions to the origin, but rapidly develops a highly accurate protein structure through several key innovations:

- Explicit Rigid Body Frames: Each residue is represented as a rotation and translation in 3D space, providing a mathematically rigorous framework for building the protein backbone. [35]

- Equivariant Transformers: These specialized components allow the network to reason about spatial relationships while respecting the rotational and translational symmetries of 3D space, implicitly considering unrepresented side-chain atoms during backbone refinement. [34]

- Iterative Refinement via Recycling: The entire network employs an iterative refinement process where outputs are recursively fed back into the same modules, with the final loss applied repeatedly to gradually improve coordinate accuracy. [35] [37]

This end-to-end differentiability is a unifying framework that enables gradient-based learning throughout the entire system, from input sequences to output structures. [34]

Evolutionary Information as Foundation: The Critical Role of MSAs

A high-quality multiple sequence alignment (MSA) serves as the foundational input that enables AF2's remarkable performance. [37] The system works by comparing and analyzing sequences of related proteins from different organisms, highlighting similarities and differences that reveal evolutionary constraints. [37] The fundamental principle underpinning this approach is co-evolution: when two amino acids are in close physical contact, mutations in one tend to be compensated by complementary mutations in the other to preserve structural integrity. [37] By detecting these correlated mutation patterns across evolutionarily related sequences, AF2 can infer spatial proximity even without explicit structural templates.

The quality and depth of the MSA directly impacts prediction accuracy. A diverse and deep MSA with hundreds or thousands of sequences provides strong co-evolutionary signals that enable accurate structure determination. [37] Conversely, a shallow MSA with limited sequence diversity represents the most common cause of low-confidence predictions. [37] While AF2 can incorporate structural templates when available, it tends to rely more heavily on MSAs when they provide sufficient evolutionary information. [37]

Table: AlphaFold2 System Architecture Components and Functions

| Component | Input | Key Operations | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| EvoFormer Block | MSA representation, Pair representation | Triangle multiplicative updates, Axial attention with pair bias, MSA-to-pair outer product | Updated MSA and pair representations with refined structural hypothesis |

| Structure Module | Processed MSA and pair representations | Equivariant transformers, Rigid body frame updates, Side-chain placement | 3D coordinates of all heavy atoms |