Differential Analysis Tools for Histone Marks: A 2025 Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and applying computational tools for differential analysis of histone modification ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&TAG data.

Differential Analysis Tools for Histone Marks: A 2025 Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and applying computational tools for differential analysis of histone modification ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&TAG data. We explore the foundational challenges posed by broad histone marks like H3K27me3 and H3K36me3, which are poorly handled by traditional peak-callers. The content details specialized methodologies, including binning approaches and Hidden Markov Models, and presents findings from recent benchmark studies to guide optimal tool selection based on biological scenario and mark type. Finally, we discuss validation strategies and future directions, empowering scientists to robustly identify epigenomic changes driving disease and development.

Understanding Histone Marks and the Computational Challenge

The Biological Significance of Narrow vs. Broad Histone Marks

The genomic landscape is governed by a complex language of post-translational modifications to histone proteins, which play a crucial role in regulating gene expression and chromatin architecture. These modifications can be broadly categorized by their genomic distribution patterns: narrow marks confined to specific genomic loci and broad marks that spread across extensive chromosomal domains. This distinction is not merely morphological but reflects fundamental differences in their molecular functions, regulatory mechanisms, and biological consequences. Understanding these differences is essential for interpreting epigenetic regulation in development, disease, and cellular identity.

The analytical challenge of accurately detecting and differentiating these marks has driven the development of specialized computational tools. As differential analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) data becomes increasingly sophisticated, researchers must select tools optimized for specific histone modification types to avoid misinterpretation of biological significance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of analytical approaches framed within the broader thesis that tool selection must be guided by the inherent properties of the epigenetic features under investigation.

Biological Foundations of Histone Mark Patterns

Defining Characteristics and Genomic Distributions

Narrow histone marks typically span focused genomic regions of a few hundred base pairs to several kilobases, often with high signal intensity at specific loci. These include promoter-associated marks such as H3K4me3, which marks active transcription start sites, and H3K27ac, which identifies active enhancers and promoters [1]. These sharp peaks are characteristic of transcription factor binding sites and modifications associated with regulatory elements that operate in a highly localized manner.

In contrast, broad histone marks can spread over large genomic regions spanning several kilobases to hundreds of kilobases. Key examples include H3K27me3, a repressive mark associated with facultative heterochromatin deposited by Polycomb group proteins, and H3K36me3 and H3K79me2, which are linked to actively transcribed gene bodies [1] [2]. These broad domains often correspond to large-scale chromatin states that maintain transcriptional programs over extended genomic regions.

Functional Consequences and Biological Roles

The spatial distribution of histone modifications directly correlates with their functional mechanisms. Narrow marks typically designate sites for precise molecular interactions, such as transcription factor recruitment or transcription initiation complex assembly. For instance, the sharp H3K4me3 peaks around transcription start sites facilitate pre-initiation complex formation through interactions with TFIID [3].

Broad marks often establish chromatin environments that influence transcriptional states over large domains. H3K27me3 creates repressive domains that silence entire gene clusters during development and differentiation, while H3K36me3 correlates with transcriptional elongation across gene bodies [2]. Recent research has revealed that some marks, including H3K4me3, can exhibit both narrow and broad patterns with distinct functional implications. Broad H3K4me3 domains have been identified as epigenetic signatures for tumor suppressor genes in normal cells and cell identity genes during development [3].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Histone Modifications by Distribution Pattern

| Modification | Pattern Type | Genomic Location | Primary Function | Associated Processes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Narrow | Promoters | Transcription initiation | Promoter activation, TF recruitment |

| H3K27ac | Narrow | Enhancers, Promoters | Enhancer activation | Regulatory element activity |

| H3K9ac | Narrow | Promoters | Transcription initiation | Open chromatin maintenance |

| H3K27me3 | Broad | Gene bodies, Intergenic | Transcriptional repression | Developmental silencing, Polycomb domains |

| H3K36me3 | Broad | Gene bodies | Transcription elongation | Co-transcriptional processing |

| H3K9me3 | Broad | Heterochromatin | Chromatin compaction | Constitutive heterochromatin formation |

| H3K79me2 | Broad | Gene bodies | Transcription elongation | Transcriptional regulation |

Computational Tools for Differential Analysis

Performance Comparison Across Tool Categories

The performance of computational tools for differential ChIP-seq analysis varies significantly depending on the histone mark type being investigated. Comprehensive benchmarking studies have evaluated tools based on metrics including area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), stability, and computational cost [1]. The DCS score, which combines these metrics, provides a standardized measure for tool comparison.

Tools can be broadly categorized as peak-dependent (requiring external peak calling) or peak-independent (with internal peak calling). Peak-dependent approaches generally show significantly better performance on simulated data with clearly defined regions and high signal-to-noise ratios, while peak-independent tools demonstrate more consistent performance on genuine experimental data with heterogeneous background noise [1].

Specialized algorithms have been developed to address the particular challenges of broad histone mark analysis. These tools typically use binning strategies or hidden Markov models to detect diffuse enrichment patterns that conventional peak-callers might fragment or miss entirely.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Differential ChIP-seq Analysis Tools

| Tool | Peak Dependency | Best For | Regulation Scenario | Key Strength | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bdgdiff (MACS2) | Dependent | Sharp marks | All scenarios | High AUPRC for sharp peaks | Fragments broad domains |

| MEDIPS | Independent | Sharp marks | Balanced (50:50) | Consistent performance | Lower sensitivity for broad marks |

| PePr | Dependent | Sharp marks | Global change (100:0) | Optimized for knockout studies | Requires predefined peaks |

| histoneHMM | Independent | Broad marks | All scenarios | HMM for broad domains | Specialized for broad marks only |

| csaw | Independent | Sharp marks | Balanced (50:50) | Window-based approach | Struggles with diffuse signals |

| ChIPbinner | Independent | Broad marks | Global change (100:0) | Reference-agnostic binning | Newer method, less validation |

| Rseg | Independent | Broad marks | Balanced (50:50) | Good gene body coverage | Occasional result inversion |

| DiffReps | Independent | Sharp marks | Balanced (50:50) | Multiple testing correction | Lower specificity for broad marks |

Specialized Algorithms for Broad Histone Marks

histoneHMM represents a specialized approach for differential analysis of histone modifications with broad genomic footprints. This bivariate Hidden Markov Model aggregates short-reads over larger regions and uses the resulting counts as inputs for unsupervised classification, requiring no further tuning parameters [2]. The tool outputs probabilistic classifications of genomic regions as modified in both samples, unmodified in both samples, or differentially modified between samples. Validation studies on H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 data demonstrate its superiority in detecting functionally relevant differentially modified regions compared to general-purpose tools [2].

ChIPbinner is a more recent R package specifically tailored for reference-agnostic analysis of broad histone modifications. Instead of relying on pre-identified enriched regions from peak-callers, ChIPbinner divides the genome into uniform windows, providing an unbiased method to explore genome-wide differences [4]. This approach avoids assumptions about peak morphology and better captures the diffuse nature of broad marks. The tool incorporates the ROTS (reproducibility-optimized test statistics) method, which optimizes the test statistic directly from the data rather than relying on a fixed predefined statistical model [4].

hiddenDomains uses a Hidden Markov Model approach to identify both enriched peaks and domains simultaneously without prior tuning for specific enrichment types. This tool generates posterior probabilities that provide confidence measures beyond simple binary "enriched" or "depleted" calls, allowing researchers to distinguish high-confidence and moderate-confidence regions within enriched domains [5].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Benchmarking Frameworks and Reference Datasets

Robust evaluation of differential analysis tools requires standardized reference datasets representing different biological scenarios. Benchmarking studies typically employ two complementary approaches: in silico simulation of ChIP-seq data and experimental sub-sampling of genuine ChIP-seq data [1].

The DCSsim tool generates artificial ChIP-seq reads distributed into samples based on beta distributions and predefined replicate numbers. This approach creates clearly defined regions with controlled signal-to-noise ratios, enabling precise performance measurement [1]. To model more realistic experimental conditions with heterogeneous background noise, DCSsub sub-samples reads from genuine ChIP-seq experiments while maintaining the original distribution characteristics.

Benchmarking studies typically evaluate tools across different biological regulation scenarios, including balanced changes (equal fractions of regions showing increase and decrease at 50:50 ratio) representative of physiological state comparisons, and global changes (100:0 ratio) simulating knockout or inhibition experiments [1]. Performance is measured using precision-recall curves and the area under these curves (AUPRC) across different peak shapes and regulation scenarios.

Analytical Workflows for Different Mark Types

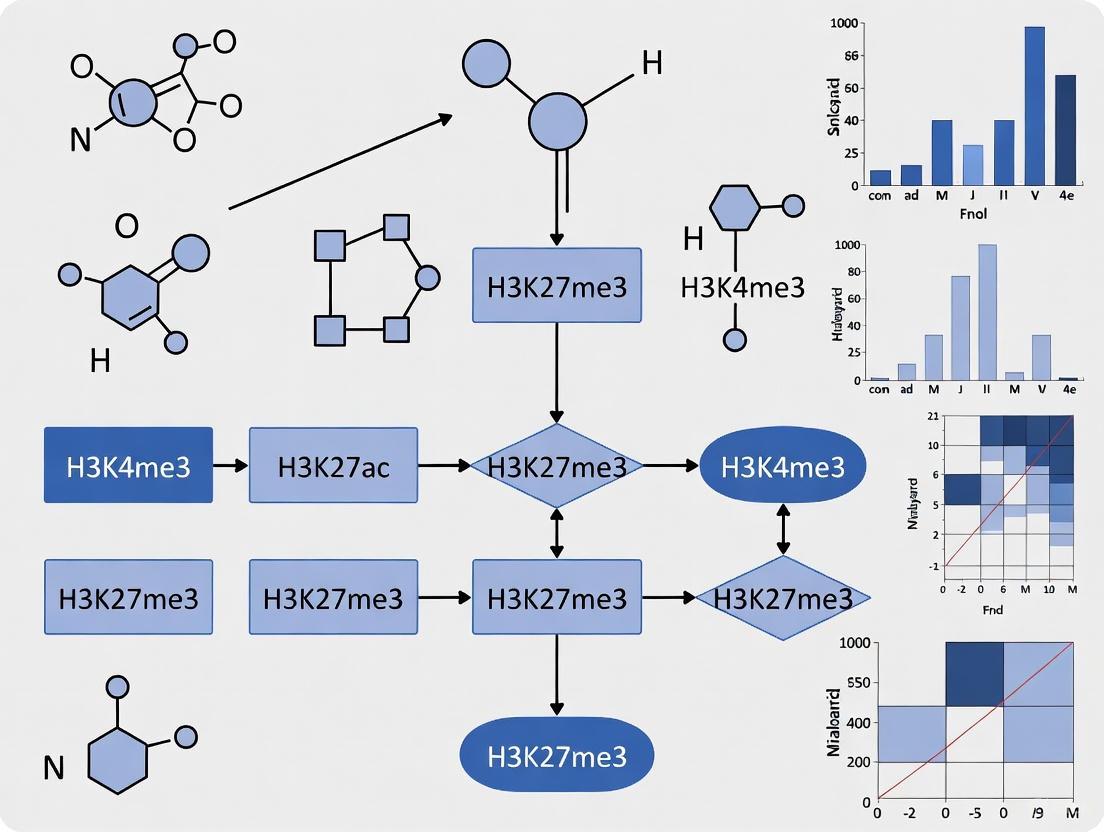

The analytical workflow for differential histone mark analysis requires careful tool selection at each step based on the mark type being investigated. The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate analytical strategies:

Decision Workflow for Histone Mark Analysis

Quality Control and Validation Metrics

Proper quality control is essential for reliable differential histone mark analysis. Key metrics include:

- FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks): Measures signal-to-noise ratio; should typically exceed 1-5% depending on the mark [6]

- Alignment rates: Should exceed 80% for target species

- Duplicate rates: Ideally below 25% with fewer than 10% of reads trimmed

- Peak size distribution: Should match expected patterns for the investigated mark

- Reproducibility between replicates: Assessed using Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) or correlation metrics

Biological validation should include correlation with complementary data types, such as RNA-seq for functional transcriptional outcomes, and comparison to known biological expectations for the system under investigation.

Advanced Applications and Research Technologies

Single-Cell Histone Modification Profiling

Recent technological advances have enabled genome-wide profiling of histone modifications at single-cell resolution. Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation (TACIT) allows single-cell analysis of multiple histone modifications across development, revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in epigenetic states [7]. This method has been applied to mouse early embryos, generating genome-wide maps of seven histone modifications across 3,749 individual cells [7].

The CoTACIT method extends this capability to profile multiple histone modifications in the same single cell through sequential rounds of antibody binding and tagmentation [7]. These single-cell epigenomic approaches are revealing unprecedented heterogeneity in histone modification patterns and their relationship to lineage specification during development.

Integration with Multi-Omics Approaches

Comprehensive understanding of histone mark function requires integration with complementary data types. Multi-omics approaches combining histone modification data with transcriptome, chromatin accessibility, and DNA methylation information provide more complete models of epigenetic regulation.

Machine learning frameworks applied to integrated multi-omics data can predict lineage-specifying transcription factors and identify regulatory elements driving cellular identity changes [7]. These integrated analyses demonstrate that broad H3K4me3 domains specifically mark cell identity genes during development and tumor suppressor genes in normal cells [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Histone Mark Analysis

| Reagent/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq antibodies | Biological reagent | Target-specific immunoprecipitation | Antibody quality critically impacts data quality |

| Low-input ChIP-seq kits | Library preparation | Enable profiling of scarce samples | Essential for developmental and clinical samples |

| TACIT/CoTACIT | Single-cell platform | Single-cell histone modification profiling | Reveals cellular heterogeneity in epigenetic states |

| MACS2 | Computational tool | Peak calling for narrow marks | Industry standard for TF and sharp histone marks |

| SICER2 | Computational tool | Domain calling for broad marks | Specialized for diffuse enrichment patterns |

| histoneHMM | Computational tool | Differential analysis of broad marks | HMM-based approach for broad domains |

| ChIPbinner | Computational tool | Binned analysis of broad marks | Reference-agnostic approach for diffuse signals |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Computational tool | General differential analysis | Adaptable for count-based differential enrichment |

The biological significance of narrow versus broad histone marks extends beyond their spatial distribution to encompass fundamental differences in their mechanisms of action and functional consequences. Accurate interpretation of these epigenetic signals requires analytical approaches specifically tailored to their distinct characteristics. As single-cell epigenomics and multi-omics integration advance, our understanding of how these modification patterns establish and maintain cellular identity in development and disease will continue to deepen. Future methodological developments will likely focus on improved detection of mixed patterns, dynamic tracking of modification changes, and enhanced integration across epigenetic layers to provide more comprehensive models of chromatin-mediated regulation.

Why Traditional Peak-Callers Fail with Broad Domains

The Fundamental Divide in Chromatin Marks

In the analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) data, genomic regions enriched with signals are broadly categorized into two distinct types: narrow peaks and broad domains. This fundamental distinction lies at the heart of why traditional peak-calling algorithms often fail to adequately characterize certain histone modifications.

Narrow peaks, typically associated with transcription factor binding sites and some histone marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, span focused genomic regions of a few hundred base pairs to a few kilobases. In contrast, broad domains represent extensive genomic regions that can span tens to hundreds of kilobases, encompassing features like repressed chromatin marked by H3K27me3 or actively transcribed gene bodies marked by H3K36me3 [1] [5].

The algorithmic assumptions optimized for identifying sharp, focal signals become problematic when applied to these diffuse, extended regions. Traditional peak-callers tend to fragment broad domains into smaller, often biologically meaningless segments, or fail to detect them entirely, creating significant analytical gaps in epigenetic studies [4] [5].

Core Algorithmic Limitations

Inappropriate Statistical Models

Traditional peak-callers like MACS2 employ statistical models, typically based on Poisson or binomial distributions, that assume focused enrichment patterns with well-defined boundaries [8]. These models are optimized for local signal enrichment against background noise, an approach that struggles with broad marks that display moderate but consistent enrichment across extensive genomic regions.

The fundamental issue is that broad histone marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K36me3 do not exhibit the sharp, peak-like profiles that these models are designed to detect. Instead, they form extended plateaus of modification across large genomic regions, which lack the pronounced focal enrichment that traditional algorithms use to distinguish signal from background [1] [5].

Fragmentation and Inconsistent Domain Boundaries

When traditional peak-callers are applied to broad domains, they often produce fragmented outputs that break biologically coherent domains into multiple smaller peaks. This fragmentation problem was clearly demonstrated in a benchmark study where different programs applied to the same H3K27me3 dataset identified anywhere from 5,014 to 143,184 domains, with average domain widths varying from 2.8 kb to 124 kb [5].

This extreme variability in domain identification directly impacts biological interpretation. Programs that generate excessive fragmentation create challenges for downstream analyses, including associating domains with target genes and quantifying enrichment levels accurately across conditions [5].

Normalization Challenges for Global Changes

Differential analysis of broad domains introduces additional normalization challenges that traditional methods handle poorly. Many tools originally designed for RNA-seq data analysis assume that the majority of genomic regions do not change between experimental conditions [1]. However, this assumption is frequently violated in epigenetic studies involving experimental perturbations, such as knockout of histone-modifying enzymes or drug treatments that globally affect chromatin marks [1].

In scenarios where a histone mark undergoes global redistribution rather than focal changes, normalization methods that assume balanced changes can produce misleading results. For instance, when H3K27me3 transitions from a broad to promoter-focused distribution due to specific mutations, traditional normalization approaches may incorrectly adjust the data, obscuring genuine biological effects [4] [1].

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Specialized Methods

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance Across Peak Types and Biological Scenarios

| Tool Category | Example Tools | Transcription Factors (Narrow Peaks) | Broad Histone Marks (H3K27me3) | Global Reduction Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Peak-Callers | MACS2, Homer | High performance (AUPRC: 0.85-0.95) | Moderate to low performance (AUPRC: 0.45-0.65) | High false discovery rate |

| Broad Mark Specialized Tools | SICER, Rseg, hiddenDomains | Moderate performance (AUPRC: 0.70-0.80) | High performance (AUPRC: 0.75-0.90) | Better control of false positives |

| Alternative Approaches | ChIPbinner, csaw | Variable performance | Improved detection of broad patterns | More robust to global changes |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics on H3K27me3 Data (Sensitivity and Specificity)

| Tool | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Average Domain Width | Fragmentation Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rseg | 75.2 | 58.1 | 124 kb | Low |

| hiddenDomains | 62.3 | 90.4 | 28 kb | Moderate |

| PeakRanger-BCP | 61.8 | 89.7 | 32 kb | Moderate |

| MACS2 (broad) | 59.5 | 88.2 | 15 kb | High |

| SICER | 52.1 | 95.3 | 25 kb | Moderate |

| Homer | 48.7 | 96.8 | 8 kb | Very High |

Performance data derived from benchmarking studies reveals consistent patterns of superiority for specialized tools when analyzing broad histone marks. In comprehensive evaluations using ChIP-qPCR validated sites for H3K27me3, specialized methods demonstrate significantly better balance between sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional peak-callers [5].

The fragmentation problem is particularly evident in the average domain widths reported by different algorithms. While Rseg identifies long domains (average 124 kb), tools like Homer and MACS2 produce much shorter segments (8-15 kb averages), indicating their tendency to break biologically coherent domains into smaller fragments [5].

Emerging Solutions and Alternative Approaches

Specialized Algorithms for Broad Domains

Several algorithms have been specifically developed to address the limitations of traditional peak-callers for broad domains:

SICER and SICERpy: Employ spatial clustering approaches to identify enriched regions by accounting for the diffuse nature of broad marks, using statistical methods that consider the distribution of reads across larger genomic contexts [9] [1].

Rseg: Utilizes a hidden Markov model approach to segment the genome into broad domains of enrichment and depletion, though it sometimes suffers from inversion problems where enriched regions are called depleted [5].

hiddenDomains: Implements hidden Markov models that simultaneously identify both narrow peaks and broad domains without prior assumptions about enrichment type, automatically adjusting to prevent inversion artifacts [5].

Reference-Agnostic Binning Approaches

Rather than relying on peak-calling, bin-based methods like ChIPbinner divide the genome into uniform windows and analyze signal patterns across these bins, completely avoiding assumptions about peak shape or size [4]. This approach provides several advantages for broad mark analysis:

- Unbiased analysis without pre-defined references

- Detection of broader patterns and correlations often missed by peak-focused approaches

- Improved performance for differential analysis of broad histone marks like H3K36me2/3 [4]

ChIPbinner specifically addresses the fragmentation problem by clustering bins independently of differential enrichment status, providing more accurate identification of broadly changing genomic regions [4].

Normalization Methods for Differential Analysis

Proper normalization is particularly crucial for differential analysis of broad domains. Recent research has identified that the choice of normalization method should be guided by technical conditions specific to the experiment [10]. Key considerations include:

- Balanced differential DNA occupancy across conditions

- Equal total DNA occupancy across experimental states

- Equal background binding between conditions [10]

When these conditions are violated, which frequently occurs in experiments involving global chromatin perturbations, researchers can employ high-confidence peaksets—the intersection of differentially bound peaks identified by multiple normalization methods—to obtain more robust biological conclusions [10].

Experimental Guidance for Researchers

Recommended Workflows

Table 3: Recommended Analytical Tools for Different Histone Marks

| Histone Mark Type | Examples | Recommended Primary Tools | Alternative Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K27ac | MACS2, SEACR | Homer, PeakRanger |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3 | SICER, hiddenDomains, Rseg | ChIPbinner, csaw |

| Mixed Patterns | H3K27me3 (in certain contexts) | hiddenDomains | MACS2 + manual curation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Mark Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 Antibody (Diagenode C15410069) | Immunoprecipitation of repressive chromatin domains | Validated for CUT&RUN; used in benchmark studies [8] |

| H3K27ac Antibody (Abcam ab4729) | Marker for active enhancers and promoters | Same antibody used in ENCODE ChIP-seq; multiple dilutions tested [11] |

| H3K4me3 Antibody (Abcam ab8580) | Associated with active transcription start sites | Used in CUT&RUN benchmarking with mouse brain tissue [8] |

| MicroPlex Library Preparation Kit v3 (Diagenode) | Library preparation for ChIP-seq | Optimized for low-input samples; 7-13 PCR cycles recommended [9] |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for CUT&RUN | Used in standardized CUT&RUN protocols [8] |

| Tn5 Transposase | Tagmentation in CUT&Tag protocols | Key enzyme in emerging tagmentation-based approaches [11] |

| Trichostatin A (TSA) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Tested for stabilizing acetyl marks in CUT&Tag; 1 µM concentration [11] |

Method Selection Framework

Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies [1], researchers should consider the following factors when selecting analytical tools:

- Peak shape characteristics: Match the algorithm to the expected signal profile

- Biological scenario: Consider whether changes are expected to be focal or global

- Sample size and replication: Some tools perform better with replicates

- Downstream analysis needs: Consider how results will be used for annotation and interpretation

For experiments involving broad domains, beginning with specialized tools like SICER or hiddenDomains, supplemented by binned approaches for differential analysis, provides the most robust foundation for accurate characterization of histone modification patterns.

Visualizing Analytical Approaches for Histone Marks

The following workflow diagram illustrates the recommended analytical strategies for different types of histone marks, highlighting the decision points where broad domains require specialized treatment:

The failure of traditional peak-callers with broad domains stems from fundamental algorithmic mismatches between tool design and biological reality. As epigenetic research continues to reveal the complexity of chromatin regulation, employing fit-for-purpose analytical methods becomes increasingly critical for accurate biological insight. By understanding these limitations and adopting the specialized tools and approaches described here, researchers can significantly improve their characterization of broad histone modifications and advance our understanding of epigenetic regulation.

The study of histone modifications is fundamental to understanding gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease mechanisms. For decades, chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the gold standard for mapping protein-DNA interactions genome-wide. However, recent technological advances have introduced powerful alternatives: CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag. These methods offer significant advantages in resolution, sensitivity, and required input material. For researchers investigating histone marks, the choice of methodology critically impacts data quality and biological interpretation, particularly for differential analysis comparing biological states. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three key technologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and suitability for histone mark research to inform optimal experimental design.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&Tag, highlighting key differences that influence method selection.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Chromatin Profiling Technologies

| Feature | ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | CUT&Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Crosslinking, fragmentation, immunoprecipitation | Antibody-guided in situ nuclease cleavage | Antibody-guided in situ tagmentation |

| Crosslinking | Required (heavy) | Optional (light) or native | Native (no crosslinking) |

| Fragmentation | Sonication or MNase | pA-MNase fusion protein | pA-Tn5 transposase fusion |

| Library Prep | In vitro (multi-step) | In vitro | Largely in vivo |

| Typical Protocol Duration | 3-5 days [12] | 2-3 days [13] | 1-2 days [13] |

| Single-Cell Amenable | No | Challenging [12] | Yes [13] |

Workflow Visualization

The fundamental difference between these technologies lies in their experimental workflows, which directly impact their performance.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide critical data for comparing the performance of these methods. The following table synthesizes quantitative performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Histone Mark Profiling

| Performance Metric | ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | CUT&Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Input | 1-10 million cells [11] | 500,000 cells (down to 5,000) [12] | ~100,000 cells [13] |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-40 million reads [12] | 3-8 million reads [12] | ~2 million reads [13] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lower (high background) [12] | Higher [14] [12] | Highest [14] |

| Recall vs. ENCODE ChIP-seq | Benchmark | Data similar [12] | ~54% for H3K27ac & H3K27me3 [11] |

| Heterochromatin Performance | Biased against repetitive elements [15] | Improved for some marks [15] | Superior for H3K9me3 at repetitive elements [15] |

| Key Advantages | Extensive existing data for comparison | Balance of compatibility and quality [12] | Speed, low input, single-cell application [13] |

Key Performance Insights

- Sensitivity and Specificity: CUT&Tag demonstrates a higher signal-to-noise ratio compared to other methods, which allows for lower sequencing depths [14] [13]. A 2025 benchmarking study reported that CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of known ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications H3K27ac and H3K27me3, with these peaks representing the strongest ENCODE signals and showing the same functional enrichments [11].

- Method-Specific Biases: ChIP-seq shows a distinct bias toward open chromatin regions, such as gene promoters, while under-representing heterochromatic regions and repetitive elements [15]. CUT&Tag overcomes this limitation, enabling robust profiling of marks like H3K9me3 at repetitive elements, which are often lost in ChIP-seq due to insoluble chromatin formation [15].

- Technical Reproducibility: Both CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag show high replicate consistency and correlation with ChIP-seq data for most histone marks, though significant differences can emerge for specific marks and genomic contexts [15].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed CUT&Tag Protocol for Histone Marks

The following diagram outlines a standard CUT&Tag protocol, which can be completed in 1-2 days [13].

Critical Optimization Steps

- Cell Permeabilization: Efficient digitonin-based permeabilization is crucial for antibody and pA-Tn5 access to the nuclear interior [13].

- Antibody Validation: Antibody quality remains a critical factor. Use CUT&Tag-validated antibodies where possible, as ChIP-grade antibodies may not perform optimally in this system [11] [12].

- PCR Cycle Optimization: Excessive PCR amplification can lead to high duplication rates. Titrate cycles based on starting material; 12-15 cycles are often sufficient [11].

- Control Reactions: Always include a negative control (e.g., non-specific IgG) and, if possible, a positive control (e.g., H3K3me3) to assess background and experimental efficiency [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these chromatin profiling methods requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for a CUT&Tag experiment.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CUT&Tag Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pA-Tn5 Transposase | Binds primary antibody and performs tagmentation | CUTANA pAG-Tn5 [16]; CUT&Tag pAG-Tn5 (Loaded) [13] |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Binds specific histone mark | Anti-H3K27me3 [16]; Anti-H3K27ac [11] |

| Magnetic Beads | Immobilizes nuclei during washing steps | Concanavalin A Magnetic Beads [13] |

| Permeabilization Buffer | Enables antibody/Tn5 nuclear access | Digitonin Solution in appropriate buffer [13] |

| Library Amplification Mix | Amplifies tagmented DNA for sequencing | CUT&Tag Dual Index Primers and PCR Master Mix [13] |

| DNA Purification System | Purifies DNA after proteinase K treatment | DNA Purification Buffers and Spin Columns [13] |

| Peak Calling Software | Identifies significantly enriched regions | MACS2, SEACR (optimize parameters for CUT&Tag) [11] |

Differential Analysis Considerations

The choice of chromatin profiling method directly impacts downstream differential analysis, a crucial step when comparing histone marks between biological conditions.

- Tool Selection: A comprehensive 2022 benchmark of 33 differential ChIP-seq (DCS) tools found that performance is strongly dependent on peak characteristics (sharp vs. broad) and the biological scenario (e.g., 50:50 changes vs. global shifts) [1]. Tools like bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, and PePr showed robust performance across various scenarios [1].

- Normalization Challenges: Methods originally designed for RNA-seq data may assume most genomic regions do not change, an assumption violated in experiments involving global epigenetic perturbations (e.g., histone methyltransferase inhibition) [1].

- Peak Calling Impact: The peak caller used significantly affects differential analysis results. For CUT&Tag data, both MACS2 and SEACR are commonly used, but parameters may need optimization as CUT&Tag peaks can be narrower than ChIP-seq peaks [11].

Choosing between ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&Tag requires careful consideration of research goals, sample availability, and technical expertise. ChIP-seq remains valuable for comparing with existing datasets but has significant limitations in resolution, input requirements, and bias. CUT&RUN provides an excellent balance of compatibility and data quality, suitable for most histone marks and chromatin-associated proteins. CUT&Tag offers the highest sensitivity and speed, enables single-cell applications, and provides superior mapping of heterochromatic regions, though it may require more technical expertise.

For most new investigations into histone marks, particularly with limited sample material or when studying repetitive genomic regions, CUT&Tag represents the most advanced approach, provided appropriate optimization and controls are implemented. The data generated are highly concordant with ChIP-seq for most euchromatic marks while overcoming fundamental biases inherent in crosslinking-based methods.

This guide provides an objective comparison of computational tools for detecting differential enrichment in histone mark studies. We evaluate performance across various histone mark types, supported by experimental data, to inform optimal tool selection for research and drug development. The comparison reveals that tool performance is highly dependent on the biological scenario and mark specificity, with no single solution outperforming all others in every context.

Detecting genuine differences in histone modification patterns between biological states is a fundamental goal in epigenomics. This process, known as differential enrichment analysis, enables researchers to identify epigenetic changes underlying development, disease, and treatment responses. However, the computational landscape is fragmented, with tools demonstrating variable performance depending on histone mark type, regulatory scenario, and data characteristics. This guide synthesizes recent benchmarking studies and methodological advances to empower researchers in selecting appropriate tools for their specific experimental context.

Performance Comparison of Differential Analysis Tools

Table 1: Tool Performance Across Histone Mark Types

| Tool Name | Primary Strength | Histone Mark Specificity | Regulatory Scenario | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAnorm | Sharp marks, TFs | Active marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) | Balanced changes (50:50) | [1] |

| csaw | Sharp marks, TFs | Active marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) | Balanced changes (50:50) | [1] |

| ChIPbinner | Broad marks | Repressive marks (H3K27me3, H3K36me3) | Global shifts (100:0) | [4] |

| histoneHMM | Broad marks | Repressive marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Balanced changes (50:50) | [17] |

| DiffHiChIP | 3D chromatin | All marks in 3D context | Long-range interactions | [18] |

| bdgdiff (MACS2) | Versatile | Both sharp and broad marks | Multiple scenarios | [1] |

| MEDIPS | Versatile | Both sharp and broad marks | Multiple scenarios | [1] |

| PePr | Versatile | Both sharp and broad marks | Multiple scenarios | [1] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Aspect | Top Performing Tools | Experimental Validation | Key Limitation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | bdgdiff, MEDIPS, PePr | qPCR validation | Poor performance with broad marks | [1] |

| Sharp Histone Marks | MAnorm, csaw | RNA-seq correlation | Global change scenarios | [1] |

| Broad Histone Marks | histoneHMM, ChIPbinner, Rseg | Functional enrichment | Fragmentation of broad domains | [4] [17] |

| Differential 3D Interactions | DiffHiChIP | Hi-C validation | Distance decay effects | [18] |

| Computational Efficiency | histoneHMM, MACS2 | Large-scale application | Memory usage with broad windows | [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Differential Analysis Workflow

The foundational workflow for differential histone mark analysis involves sequential processing steps:

- Quality Control: Assess raw sequencing data quality using FastQC and alignment metrics [19]

- Read Mapping: Align sequencing reads to reference genome using Bowtie2 or BWA [20] [19]

- Peak Calling: Identify enriched regions using shape-appropriate tools (MACS2 for sharp marks, SICER2 for broad marks) [1] [19]

- Normalization: Account for technical variability using control samples (input DNA, H3 pull-down) [20]

- Differential Analysis: Apply specialized tools based on mark type and biological question

- Functional Interpretation: Annotate regions and integrate with complementary data (e.g., RNA-seq) [21]

Standard differential analysis workflow for histone modifications

Protocol 2: Binned Analysis for Broad Histone Marks

ChIPbinner implements an alternative reference-agnostic approach specifically designed for diffuse histone marks:

- Data Preprocessing: Convert aligned reads (BAM) to BED format and bin genome into uniform windows [4]

- Normalization: Scale signals using the ROTS method, which optimizes test statistics directly from data [4]

- Clustering Analysis: Group bins based on normalized counts independent of differential status [4]

- Differential Assessment: Identify significantly changed bins using reproducibility-optimized statistics [4]

- Functional Annotation: Characterize clusters for enrichment in genic/intergenic regions [4]

This method avoids peak-calling assumptions that often fragment broad domains into biologically meaningless segments.

Protocol 3: Differential Analysis in 3D Chromatin Context

DiffHiChIP provides a specialized framework for detecting differential chromatin interactions from HiChIP data:

- Contact Map Generation: Process HiChIP data to generate genome-wide contact matrices [18]

- Background Modeling: Account for distance decay of contact probability using stratification techniques [18]

- Statistical Testing: Implement edgeR with generalized linear models and quasi-likelihood F tests [18]

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply independent hypothesis weighting to control false discovery rates [18]

- Long-Range Interaction Detection: Specifically capture interactions >400 kb using specialized distance modeling [18]

Critical Experimental Design Considerations

Biological Versus Technical Replicates

A critical determinant of analysis success is appropriate replication strategy. Biological replicates (multiple samples from different biological sources) are essential for population inference and account for natural variability, while technical replicates (multiple sequencing runs of the same library) primarily address technical noise [21]. Most differential tools require biological replicates for robust statistical testing.

Control Sample Selection

The choice of control samples significantly impacts differential analysis outcomes:

- Input DNA (WCE): Most common control, representing sheared chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation [20]

- Histone H3 Pull-down: Specifically maps nucleosome distribution, potentially more appropriate for histone modification studies [20]

- IgG Control: Mock immunoprecipitation with non-specific antibody, though often yields limited DNA [20]

Comparative studies indicate H3 pull-down controls better emulate background in histone modification studies, particularly for marks with broad distributions [20].

Scenario-Specific Tool Selection

Tool performance varies dramatically depending on the biological context:

- Balanced Changes (50:50): Scenarios where similar proportions of regions show increased and decreased signal (e.g., comparing developmental states) are well-handled by most tools [1]

- Global Shifts (100:0): Scenarios with widespread changes in one condition (e.g., knockout or pharmacological inhibition) require specialized normalization to avoid false negatives [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Differential Histone Mark Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of target histone marks | Quality and specificity critically impact results [20] |

| Control Samples | Background signal estimation | Input DNA, H3 pull-down, or IgG controls [20] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Preserve protein-DNA interactions | Formaldehyde most common; dual crosslinking for Micro-C-ChIP [22] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Generate appropriately sized fragments | MNase for nucleosome-resolution; sonication for standard ChIP [22] |

| Size Selection Kits | Isolation of proximity-ligated fragments | Critical for reducing non-informative reads in 3D methods [22] |

| Spike-in Controls | Normalization across conditions | Useful for global change scenarios [1] |

Selecting optimal tools for differential histone mark analysis requires careful consideration of experimental goals and mark characteristics. For sharp marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, MAnorm and csaw demonstrate robust performance. For broad marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, ChIPbinner and histoneHMM provide superior detection of differentially modified regions. For studies investigating 3D chromatin architecture, DiffHiChIP addresses specific challenges of chromatin interaction data. Ultimately, researchers should prioritize tools based on their specific histone mark of interest, biological question, and experimental design, as no single solution excels across all contexts.

A Toolkit of Algorithms: From Binning to Hidden Markov Models

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) and related technologies like CUT&RUN and CUT&TAG have become fundamental methods for mapping the epigenomic landscape, particularly histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) [12]. These histone marks play critical regulatory roles in gene expression, with broad marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K36me2/3 forming diffuse domains across large genomic regions rather than focused, peak-like signals [23] [24]. Analyzing these broad domains presents significant computational challenges, as traditional peak-calling algorithms like MACS2 were originally designed for sharp, well-defined transcription factor binding sites and often struggle with extended regions of enrichment [23] [2]. This fragmentation of biologically coherent domains into smaller, often meaningless peaks creates a pressing need for alternative analytical approaches in comparative epigenomics studies.

The binning approach represents a paradigm shift from peak-based analysis by dividing the entire genome into uniform, non-overlapping windows for analysis. This reference-agnostic strategy avoids prior assumptions about enrichment patterns and enables unbiased detection of differential histone modifications across the genome [23] [24]. This guide focuses on ChIPbinner, an R package specifically developed to address the limitations of peak-callers for broad histone marks, and compares its performance and methodology with other available tools for differential analysis of histone modifications.

ChIPbinner: Purpose-Built for Broad Marks

ChIPbinner is an open-source R package specifically tailored for reference-agnostic analysis of broad histone modifications from ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, and CUT&TAG data [23] [25]. Unlike peak-dependent methods, ChIPbinner employs a uniform windowing approach across the genome, providing an unbiased method to explore genome-wide differences between samples. Key features include:

- Reference-agnostic analysis: Divides the genome into uniform bins without relying on pre-identified enriched regions [23]

- Differential binding detection: Uses the ROTS (reproducibility-optimized test statistics) method to assess differential binding between groups, optimizing test statistics directly from data without fixed predefined models [23]

- Cluster identification: Identifies and characterizes clusters of bins independent of their differential enrichment status [23]

- Exploratory analysis: Provides visualization tools including scatterplots, PCA, and correlation plots to assess sample relationships [23]

- Annotation capabilities: Includes functions for annotating bins as genic or intergenic and enrichment/depletion analysis [23]

Alternative Differential Analysis Tools

Several other tools address differential histone mark analysis with varying approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Differential Analysis Tools for Histone Modifications

| Tool | Methodology | Primary Strength | Limitations | Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIPbinner | Uniform binning with ROTS statistics | Optimized for broad histone marks; cluster identification independent of DB status | Less power for highly focused, peak-like marks | BED files of binned sequencing data [23] |

| histoneHMM | Bivariate Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Specifically designed for broad repressive marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Limited to comparisons between two conditions | Binned read counts (1000bp windows) [2] |

| csaw | Window-based counting with edgeR | Flexibility in window size; can detect both broad and narrow regions | Default clustering struggles with diffuse marks; requires manual coding for normalization | BAM files directly [23] |

| DiffBind | Peak-set based differential analysis | Excellent for pre-defined regions; works well with narrow marks | Dependent on peak-caller assumptions and biases | Pre-called peaksets [23] [26] |

| PBS (Probability of Being Signal) | Gamma distribution fitting to 5kB bins | Simple implementation; straightforward normalization and comparison | Lower resolution than peak-based methods | BAM files converted to binned counts [24] |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Analytical Approach Comparison

Each tool employs distinct statistical frameworks for detecting differential enrichment:

- ChIPbinner utilizes the ROTS method, which maximizes the reproducibility of top-ranked features in bootstrap datasets, performing particularly well with datasets containing large proportions of differentially enriched features [23]

- histoneHMM implements a bivariate Hidden Markov Model that probabilistically classifies genomic regions into three states: modified in both samples, unmodified in both, or differentially modified [2]

- PBS method fits a gamma distribution to the background signal and calculates a "probability of being signal" (0-1) for each bin, enabling direct comparison across datasets [24]

- csaw uses statistical methods from the edgeR package, originally designed for differential gene expression analysis, and controls false discovery rates across detected regions [23]

Performance in Benchmarking Studies

While direct comparative benchmarks between ChIPbinner and other tools are limited in the current literature, assessments of similar binning approaches demonstrate advantages for broad mark analysis:

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Binning-Based Approaches

| Performance Aspect | ChIPbinner | histoneHMM | csaw | PBS Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Mark Detection | Excellent for diffuse signals [23] | Excellent for H3K27me3, H3K9me3 [2] | Requires post-hoc clustering for diffuse marks [23] | Effective for both broad and narrow marks [24] |

| Narrow Mark Resolution | Limited by bin size | Limited by 1000bp bins | Flexible with adjustable windows | Limited by 5kB bins |

| Statistical Framework | ROTS - data-optimized statistics [23] | Bivariate HMM - probabilistic classification [2] | edgeR - negative binomial models [23] | Gamma distribution background modeling [24] |

| Multi-sample Comparison | Supports multiple conditions through clustering | Primarily for two-condition comparison | Supports complex experimental designs | Enables comparison across multiple datasets |

| Ease of Implementation | Minimal dependencies; R package [25] | R package; fast C++ implementation [2] | Requires BioConductor installation | Simple implementation in existing pipelines |

In evaluations of similar tools, histoneHMM demonstrated superior performance in detecting functionally relevant differentially modified regions for broad repressive marks compared to Diffreps, Chipdiff, Pepr, and Rseg when analyzing H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 data from rat, mouse, and human cell lines [2]. The binning approach used by ChIPbinner has shown particular effectiveness for marks like H3K36me2, where it accurately detected depletion following NSD1 knockout in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

ChIPbinner Workflow Implementation

The ChIPbinner analysis pipeline follows a systematic process for identifying differentially enriched regions in broad histone marks:

ChIPbinner Analysis Workflow

The detailed methodology consists of these critical steps:

- Data Pre-processing: Convert aligned sequencing reads in BAM format to BED format using tools like

bedtools bamtobed[23] - Genome Binning: Divide the genome into uniform windows, with recommended sizes ranging from 1-10 kilobases depending on the expected size of changes [23]

- Signal Normalization: Normalize raw counts per bin, accounting for factors like mappability and copy number variations [23]

- Exploratory Analysis: Assess data quality and sample relationships using PCA and correlation plots to ensure replicate consistency and treatment separation [23]

- Differential Binding Analysis: Apply the ROTS method to identify bins showing significant differences between experimental conditions [23]

- Cluster Identification: Group bins with similar behavior across the genome using K-means clustering, independent of differential binding status [23]

- Functional Annotation: Characterize identified clusters by their enrichment in genic vs. intergenic regions or other genomic features [23]

Comparison of Binning Strategies

Different tools employ distinct binning and analysis strategies:

Binning Methodologies Comparison

Successful implementation of ChIPbinner and related analyses requires specific experimental and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Binning-Based Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ChIPbinner R Package | Reference-agnostic analysis of broad histone marks | Install via GitHub; minimal dependencies; includes vignettes for guidance [23] [25] |

| CUTANA CUT&RUN/CUT&Tag | Chromatin mapping with lower background vs ChIP-seq | Ideal for low cell numbers; reduced sequencing depth requirements [12] |

| bedtools | Conversion of BAM to BED format; genomic arithmetic | Essential pre-processing step for ChIPbinner input preparation [23] |

| MACS2/EPIC2 | Peak calling for narrow marks or comparative analysis | Useful for parallel analysis of sharp histone modifications [23] |

| Validated Antibodies | Specific enrichment of target histone marks | Critical for data quality; high cross-reactivity rates reported for many commercial antibodies [12] |

| ROTS Algorithm | Reproducibility-optimized differential analysis | Superior performance with large proportion of differential features [23] |

| Input DNA/IgG Controls | Background signal estimation | Essential for controlling technical variability; IgG recommended for CUT&RUN [12] |

Binning-based approaches like ChIPbinner provide a powerful alternative to peak-centric methods for analyzing broad histone modifications. The uniform windowing strategy offers particular advantages for marks such as H3K27me3, H3K9me3, and H3K36me2/3 that form extended domains across the genome [23] [24]. Unlike peak-callers that often fragment these broad domains, ChIPbinner maintains the biological coherence of these regions while enabling robust differential analysis between experimental conditions.

The choice between ChIPbinner and alternative tools depends on specific research objectives and mark characteristics. For focused marks like H3K27ac or transcription factors, peak-based methods like DiffBind may provide higher resolution [26]. For comparative analysis of broad repressive marks between two conditions, histoneHMM offers a specialized probabilistic framework [2]. However, for reference-agnostic exploration of broad histone marks across multiple conditions, particularly when prior enrichment regions are unknown or poorly defined, ChIPbinner's binning approach provides an unbiased, robust solution for epigenetic researchers.

Strategic implementation should consider sequencing depth requirements—while ChIP-seq often requires 20-40 million reads per library, CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag technologies compatible with ChIPbinner analysis can yield high-quality profiles with only 3-8 million reads, significantly reducing sequencing costs [12]. As epigenetic profiling continues to advance in disease research and drug development, binning-based approaches will play an increasingly important role in deciphering the broad regulatory landscapes that govern gene expression programs in development and disease.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become a routine method for interrogating the genome-wide distribution of various histone modifications, enabling researchers to compare epigenetic landscapes between biological states [2] [17]. However, comparative analysis remains particularly challenging for histone modifications with broad domains, such as heterochromatin-associated H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 [2]. These marks form large genomic footprints that can span several thousands of basepairs, producing relatively low read coverage in effectively modified regions and resulting in low signal-to-noise ratios [2] [17]. Most conventional ChIP-seq algorithms are designed to detect well-defined peak-like features and consequently generate false positives or false negatives when applied to broad histone marks [2].

To address this critical limitation, histoneHMM implements a powerful bivariate Hidden Markov Model specifically designed for the differential analysis of histone modifications with broad genomic footprints [2]. This computational tool provides probabilistic classification of genomic regions, enabling researchers to identify functionally relevant epigenetic changes with greater accuracy. As differential histone modification analysis becomes increasingly important for understanding developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and drug responses, tools like histoneHMM offer specialized capabilities that address specific challenges in epigenomics research.

histoneHMM: Methodological Framework and Implementation

Core Algorithmic Approach

histoneHMM employs a bivariate Hidden Markov Model that fundamentally differs from peak-centric approaches [2]. The method aggregates short-reads over larger genomic regions and takes the resulting bivariate read counts as inputs for an unsupervised classification procedure [2]. This approach requires no additional tuning parameters beyond the initial setup, simplifying implementation for researchers. The model outputs probabilistic classifications of genomic regions into one of three states: modified in both samples, unmodified in both samples, or differentially modified between samples [2] [17].

The software is implemented as a fast algorithm written in C++ and compiled as an R package, allowing it to run in the popular R computing environment and seamlessly integrate with the extensive bioinformatic tool sets available through Bioconductor [2] [27]. This integration capability significantly enhances its utility in diverse bioinformatics workflows, enabling researchers to combine differential analysis with downstream functional annotation and visualization.

Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key analytical steps in the histoneHMM workflow:

Performance Comparison: histoneHMM Versus Competing Tools

Experimental Framework and Benchmarking Data

The performance of histoneHMM has been rigorously evaluated against multiple competing algorithms using diverse biological datasets [2] [17]. Benchmarking studies utilized ChIP-seq data for:

- H3K27me3 from left ventricle heart tissue of two inbred rat strains (Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat and Brown Norway)

- H3K9me3 from liver tissue of male and female CD-1 mice

- Multiple histone marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K36me3, and H3K79me2) from human embryonic stem cell line H1-hESC and K562 cell line (ENCODE project data) [2]

These datasets represent biologically relevant scenarios for comparative epigenomics, including strain comparisons, sex differences, and cell line differentiation states [2]. The competing tools evaluated alongside histoneHMM included Diffreps, Chipdiff, PePr, and Rseg - all designed for differential analysis of ChIP-seq experiments and not restricted to narrow peak-like data [2].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Genome-wide differential region detection across platforms

| Tool | H3K27me3 Rat (Mb Detected) | H3K9me3 Mouse (Mb Detected) | qPCR Validation Rate | RNA-seq Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| histoneHMM | 24.96 Mb (0.9% of genome) | 121.89 Mb (4.6% of genome) | 71% (5/7 regions) | Most significant overlap (P=3.36×10⁻⁶) |

| Diffreps | Not specified | Not specified | 100% (7/7 regions) * | Less significant overlap |

| Chipdiff | Not specified | Not specified | 71% (5/7 regions) | Less significant overlap |

| Rseg | Larger than histoneHMM | Larger than histoneHMM | 83% (5/6 regions) | Less significant overlap |

*Diffreps detected all validated regions but also predicted two false positives [17]

Table 2: Performance across histone mark types based on comprehensive benchmarking

| Performance Aspect | Sharp Marks (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) | Broad Marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Transcription Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| histoneHMM Performance | Not primary application | Optimal performance | Not primary application |

| Recommended Tools | MEDIPS, PePr, bdgdiff | histoneHMM, Rseg | MEDIPS, PePr, bdgdiff |

Data derived from comprehensive benchmarking of 33 tools [1]

Biological Validation Outcomes

The functional relevance of differential regions identified by histoneHMM was substantiated through multiple experimental approaches:

- qPCR validation: histoneHMM achieved 71% validation rate (5 out of 7 regions) compared to Chipdiff (5/7) and Rseg (5/6) [17]

- RNA-seq integration: histoneHMM showed the most significant overlap with differentially expressed genes (P=3.36×10⁻⁶, Fisher's exact test) [17]

- Biological insight generation: Genes identified through histoneHMM as both differentially modified and differentially expressed revealed enrichment for "antigen processing and presentation" (GO:0019882, P=4.79×10⁻⁷), primarily MHC class I genes located in blood pressure quantitative trait loci [17]

Experimental Design and Methodological Protocols

Standardized Analysis Workflow

For differential analysis of broad histone marks using histoneHMM, researchers should follow these key methodological steps:

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Data Preprocessing

- Align sequencing reads to reference genome

- Bin genome into 1000 bp windows (following established practice for broad marks) [2]

- Aggregate read counts within each genomic window

histoneHMM Implementation

- Input bivariate read counts from sample pairs

- Run unsupervised classification procedure

- Output probabilistic classifications for each genomic region

Downstream Validation and Interpretation

- Integrate with transcriptomic data (RNA-seq) where available

- Perform functional annotation of differential regions

- Select top candidate regions for experimental validation (e.g., qPCR)

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Components

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Histone Marks | H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K36me3, H3K79me2 | Targets for differential epigenomic analysis |

| Biological Models | SHR/BN rat strains, CD-1 mice, H1/K562 cell lines | Model systems for comparative epigenomics |

| Experimental Methods | ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, qPCR | Data generation and validation technologies |

| Computational Tools | histoneHMM, Diffreps, Chipdiff, PePr, Rseg | Differential analysis algorithms |

| Analysis Frameworks | R/Bioconductor, Genome Browsers | Data analysis and visualization environments |

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Scenarios Favoring histoneHMM Implementation

histoneHMM demonstrates particular strength in several specific research contexts:

- Broad histone mark profiling: The tool was specifically designed for marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 that form large heterochromatic domains [2]

- Functional genomics integration: histoneHMM regions show superior correlation with gene expression changes, making it ideal for studies linking epigenomic and transcriptomic changes [17]

- Strain and cell type comparisons: The algorithm effectively identifies differential regions between closely related biological states (e.g., rat strains, cell lines) [2]

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

While histoneHMM excels with broad histone marks, researchers should consider alternative tools in these scenarios:

- Sharp mark analysis: For marks like H3K27ac and H3K4me3, tools such as MEDIPS and PePr may outperform histoneHMM [1]

- Transcription factor binding studies: Peak-centric approaches remain more appropriate for narrow, well-defined binding events [1]

- Global perturbation studies: When expecting unidirectional changes (e.g., knockout models), normalization strategies in some alternative tools may be more appropriate [1]

histoneHMM represents a specialized computational solution that addresses the particular challenges of differential analysis for broad histone modifications. Its bivariate HMM framework, probabilistic classification output, and seamless integration with Bioconductor make it a valuable tool for epigenomics researchers. Performance validation across multiple biological systems demonstrates its ability to identify functionally relevant differential regions with higher biological concordance than several competing methods.

The specialized nature of histoneHMM highlights an important trend in computational epigenomics: the movement toward context-specific tools optimized for particular biological scenarios. As the field advances, researchers would benefit from selecting differential analysis tools based on the specific histone marks being investigated, the biological question being addressed, and the expected patterns of genomic regulation. histoneHMM establishes itself as the tool of choice for studies focused on polycomb-associated repressive domains and other broad chromatin features, filling a critical niche in the epigenomics toolkit.

The analysis of differential histone modifications is a cornerstone of epigenomic research, enabling scientists to understand how gene regulation changes across biological conditions, disease states, and during development. For histone marks with broad genomic footprints—such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3—which can span thousands of base pairs, traditional peak-centric analysis methods often prove inadequate [2]. Instead, sliding window approaches provide a powerful alternative for genome-wide scanning, systematically dividing the genome into contiguous segments for statistical testing of enrichment differences [28]. Among the tools implementing this strategy, diffReps (differential replication) stands as a specifically designed solution that scans the entire genome using a sliding window, performing millions of statistical tests to identify significant differential sites while accounting for biological variation [29]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of diffReps against other computational tools for differential ChIP-seq analysis, focusing specifically on its application to histone modification studies and providing experimental data to inform tool selection for research and drug development applications.

Core Algorithm and Implementation

diffReps operates on a fundamental principle of systematic genomic partitioning followed by statistical testing within each partition. The tool employs a sliding window that moves across the genome at defined intervals, counting the number of DNA fragments overlapping each window position [29]. This approach provides comprehensive coverage of the genome without prior assumptions about peak locations, making it particularly valuable for discovering novel regulatory regions affected by epigenetic changes.

The implementation specifics of diffReps include:

- Window and Step Size: By default, diffReps uses a sliding window of 1 kilobase pair (kbp) with a moving step size of 100 base pairs (bp), though these parameters can be adjusted based on experimental needs [29].

- Fragment Extension: Like many ChIP-seq tools, diffReps extends sequenced reads to represent the complete post-sonication DNA fragment, using the average fragment length estimated from cross-correlation analysis [28].

- Input Requirements: The tool requires aligned sequencing data in BED format as input, which can be converted from other alignment formats such as BAM using tools like BedTools [29].

Statistical Framework for Differential Analysis

diffReps incorporates multiple statistical tests to accommodate different experimental designs, making it adaptable to various research scenarios:

- Negative Binomial Test: The recommended test for experiments with biological replicates, as it models discrete count data and accounts for over-dispersion among different samples [29].

- G-test and Chi-square Test: Available for experiments without biological replicates, with G-test being generally preferred due to its statistical properties [29].

- T-test: Included for comparison purposes but not recommended as the primary test, as normalized counts are not normally distributed, potentially degrading detection power [29].

A key feature of diffReps is its ability to incorporate biological variation within sample groups, which significantly enhances statistical power, particularly for in vivo studies such as those involving brain tissues [29].

Advanced Analytical Capabilities

Beyond basic differential site detection, diffReps includes supplementary functionalities for downstream analysis:

- Genomic Annotation: An integrated script automatically annotates differential sites based on their proximity to genes and association with heterochromatic regions, categorizing them into promoter-associated, genebody, or various intergenic regions [29].

- Hotspot Detection: The tool can identify spatially clustered differential sites, known as chromatin modification hotspots, by building a null model on site-to-site distance and identifying regions that violate this model with statistical significance [29].

Below is the experimental workflow for implementing diffReps in a differential histone mark analysis pipeline:

Performance Comparison: diffReps Versus Other Differential Analysis Tools

Comprehensive Benchmarking Studies

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated the performance of diffReps against other differential ChIP-seq analysis tools. A landmark 2022 study published in Genome Biology assessed 33 computational tools and approaches using standardized reference datasets created by in silico simulation and sub-sampling of genuine ChIP-seq data [1]. The researchers evaluated performance across different biological scenarios, including comparisons with equal fractions of increasing and decreasing signals (50:50 ratio) and scenarios with global decrease in one sample (100:0 ratio), representing common experimental conditions like pharmacological inhibition or gene knockout [1].

The performance assessment revealed that tool effectiveness is strongly dependent on peak characteristics and biological context. While some tools performed consistently well across scenarios, no single tool outperformed all others in every situation. The study introduced a DCS score combining the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), stability metrics, and computational cost to guide optimal tool selection [1].

Specific Performance Metrics for Histone Marks

For broad histone marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, specialized tools have been developed to address the challenges of diffuse signal patterns. histoneHMM, a bivariate Hidden Markov Model specifically designed for broad marks, was compared against diffReps and other methods (Chipdiff, PePr, and Rseg) in a study analyzing repressive marks in rat, mouse, and human cell lines [2].

The results demonstrated that while diffReps provides robust detection capabilities, its performance varies depending on the specific histone mark and biological system. histoneHMM showed particular advantages for broad genomic footprints,

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Differential ChIP-seq Tools for Histone Marks

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Best For | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| diffReps | Sliding window | Multiple biological scenarios with replicates | Multiple statistical tests; hotspot detection; biological variation integration | Performance varies with peak shape |

| histoneHMM | Hidden Markov Model | Broad marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Superior for broad domains; probabilistic classification | Less optimal for sharp marks |

| MACS2 bdgdiff | Peak-based | Sharp marks (TF, H3K27ac) | High performance in specific scenarios | Limited for broad domains |

| MEDIPS | Window-based | Multiple mark types | Consistent performance across scenarios | - |

| PePr | Peak-based | Sharp marks with replicates | Good for defined peaks | Limited for broad domains |

| csaw | Window-based | Flexible window sizes | Adaptable to different mark widths | Requires parameter optimization |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

The 2022 benchmark study provided quantitative performance data using the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) as the primary metric. While the study found that bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, and PePr showed the highest median performance independent of peak shape or regulation scenario, it emphasized that specific parameter setups in several tools yielded superior performance for particular scenarios [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Differential Analysis Tools

| Tool | Transcription Factors | Sharp Marks (H3K27ac) | Broad Marks (H3K27me3) | Global Change Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| diffReps | Variable AUPRC | Moderate AUPRC | Lower AUPRC vs. specialized tools | Moderate performance |

| histoneHMM | Not optimal | Not optimal | High AUPRC | Good performance |

| MACS2 bdgdiff | High AUPRC | High AUPRC | Lower performance | Good performance |

| MEDIPS | High AUPRC | High AUPRC | Moderate AUPRC | High AUPRC |

| PePr | High AUPRC | High AUPRC | Moderate AUPRC | High AUPRC |

| csaw | Variable performance | Variable performance | Variable performance | Variable performance |

Experimental Protocols for diffReps Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Differential Analysis

Implementing diffReps effectively requires careful attention to experimental design and computational parameters. The following protocol outlines the key steps for a robust differential histone mark analysis:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation with appropriate biological replicates (recommended minimum: 2-3 per condition)

- Sequence libraries to sufficient depth (recommended: 20-50 million reads per sample depending on genome size)

- Include appropriate control samples (input DNA, IgG, or H3 pull-down) [20]

Data Preprocessing:

- Align sequenced reads to the reference genome using Bowtie2 or similar aligner

- Convert alignment files to BED format using BedTools

- Estimate average fragment length using cross-correlation plots [28]

diffReps Execution:

- Run diffReps with Negative Binomial test if biological replicates are available

- Specify genome using built-in genomes (e.g., hg19, mm10) or custom chromosome length file

- Adjust window size and step size according to the histone mark being studied

Critical Parameter Optimization

The performance of diffReps is significantly influenced by parameter selection. Key considerations include:

- Window Size Selection: For transcription factors, smaller windows (100-500 bp) are appropriate, while for broad histone marks, larger windows (1-5 kbp) may be more effective [28] [1].

- Step Size: Smaller step sizes provide higher resolution but increase computational time, which can "vary wildly between 30min and 10h" depending on parameters [29].

- Statistical Thresholds: Adjust FDR cutoffs based on experimental goals, with stricter thresholds (e.g., 1%) recommended for candidate validation studies.

Validation and Downstream Analysis

Following differential site identification, rigorous validation is essential:

- Genomic Annotation: Use diffReps' built-in annotation script to categorize differential sites by genomic context

- Hotspot Detection: Identify spatially clustered differential regions using the hotspot detection functionality

- Integration with Expression Data: Correlate differential histone modification with RNA-seq data to identify functional regulatory changes

- Experimental Validation: Select key findings for confirmation by orthogonal methods such as qPCR or additional ChIP experiments

Successful implementation of diffReps and differential histone mark analysis requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The following table outlines key components of the experimental pipeline:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Differential Histone Mark Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Histone modification-specific antibodies (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Target immunoprecipitation | Antibody specificity is critical; validate using known controls |

| Controls | Input DNA, IgG, H3 pull-down | Background estimation | H3 pull-down may be superior for histone modifications [20] |

| Library Prep | TruSeq DNA Sample Prep Kit | Sequencing library construction | Maintain consistency across samples |

| Sequencing | Illumina platforms | Read generation | Aim for 20-50 million reads per sample |

| Alignment | Bowtie2, BWA | Map reads to reference genome | Use sensitive settings for optimal mapping |

| Format Conversion | BedTools | Convert BAM to BED format | Required for diffReps compatibility [29] |

| Statistical Analysis | diffReps, edgeR, DESeq2 | Identify differential sites | diffReps specifically designed for ChIP-seq data |

Based on comprehensive performance assessments and methodological considerations, the following guidelines emerge for researchers selecting and implementing diffReps for histone mark studies: