Dimensionality Reduction for Transcriptomics: A Practical Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques for researchers and professionals analyzing high-dimensional transcriptomic data.

Dimensionality Reduction for Transcriptomics: A Practical Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques for researchers and professionals analyzing high-dimensional transcriptomic data. It covers the foundational principles of both linear and nonlinear DR methods, explores their specific applications in tasks like cell type identification and drug response analysis, and addresses critical challenges including parameter sensitivity, noise, and batch effects. A dedicated section benchmarks popular algorithms like PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP on accuracy, stability, and structure preservation, offering evidence-based selection criteria. The guide concludes with future-looking insights on interpretability, ethical AI, and the role of DR in precision medicine.

Understanding Dimensionality Reduction: Core Concepts and Algorithm Families for Transcriptomics

The Critical Need for DR in High-Dimensional Transcriptomics Data

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has generated an unprecedented volume of transcriptomic data, presenting both remarkable opportunities and significant analytical challenges for biomedical researchers. Drug-induced transcriptomic data, which represent genome-wide expression profiles following drug treatments, have become crucial for understanding molecular mechanisms of action (MOAs), predicting drug efficacy, and identifying off-target effects in early-stage drug development [1]. However, the high dimensionality of these datasets—where each profile contains measurements for tens of thousands of genes—creates substantial obstacles for computational analysis, biological interpretation, and visualization [1]. This high-dimensional space is characterized by significant noise, redundancy, and computational complexity that obscures meaningful biological patterns essential for advancing pharmacological research and therapeutic discovery.

Dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques provide a powerful solution to this challenge by transforming high-dimensional transcriptomic data into lower-dimensional representations while preserving biologically meaningful structures [1]. These methods enable researchers to visualize complex datasets, identify previously hidden patterns, and perform more efficient downstream analyses, including clustering and trajectory inference. The growing importance of DR is particularly evident in large-scale pharmacogenomic initiatives like the Connectivity Map (CMap), which contains millions of gene expression profiles across hundreds of cell lines exposed to over 40,000 small molecules [1]. Without effective DR methodologies, extracting meaningful insights from such expansive datasets would remain computationally prohibitive and biologically uninterpretable.

Quantitative Benchmarking of DR Methods

Performance Evaluation Across Experimental Conditions

Systematic benchmarking studies have evaluated numerous DR algorithms across diverse experimental conditions to identify optimal approaches for transcriptomic data analysis. A comprehensive assessment of 30 DR methods utilized data from the CMap database, focusing on four distinct biological scenarios: different cell lines treated with the same compound, a single cell line treated with multiple compounds, a single cell line treated with compounds targeting distinct MOAs, and a single cell line treated with varying dosages of the same compound [1]. The benchmark dataset comprised 2,166 drug-induced transcriptomic change profiles, each represented as z-scores for 12,328 genes, with nine cell lines selected for their high-quality profiles: A549, HT29, PC3, A375, MCF7, HA1E, HCC515, HEPG2, and NPC [1].

Performance was assessed using internal cluster validation metrics including Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI), Silhouette score, and Variance Ratio Criterion (VRC), which quantify cluster compactness and separability based on the intrinsic geometry of embedded data without external labels [1]. External validation was performed using normalized mutual information (NMI) and adjusted rand index (ARI) to measure concordance between sample labels and unsupervised clustering results [1]. Hierarchical clustering consistently outperformed other methods including k-means, k-medoids, HDBSCAN, and affinity propagation when applied to DR outputs [1].

Table 1: Top-Performing Dimensionality Reduction Methods Across Evaluation Metrics

| DR Method | Local Structure Preservation | Global Structure Preservation | Dose-Dependency Sensitivity | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE | High | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| UMAP | High | High | Moderate | High |

| PaCMAP | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| TRIMAP | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| PHATE | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Low |

| Spectral | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Low |

Context-Dependent Method Performance

The benchmarking revealed that method performance varied significantly depending on the biological question and data characteristics. For discrete classification tasks such as separating different cell lines or grouping drugs with similar MOAs, PaCMAP, TRIMAP, t-SNE, and UMAP consistently ranked as top performers across internal validation metrics [1]. These methods excelled at preserving both local and global biological structures, effectively segregating distinct drug responses and grouping compounds with similar molecular targets in visualization space [1].

For detecting subtle, continuous patterns such as dose-dependent transcriptomic changes, Spectral, PHATE, and t-SNE demonstrated stronger performance [1]. This capability is critical for understanding concentration-dependent effects in drug response studies. Notably, PCA—despite its widespread application and interpretive simplicity—performed relatively poorly in preserving biological similarity across most experimental conditions [1]. The rankings showed high concordance across the three internal validation metrics (Kendall's W=0.91-0.94, P<0.0001), indicating general agreement in performance evaluation despite DBI consistently yielding higher scores and VRC assigning lower scores across all methods [1].

Table 2: Optimal DR Method Selection Based on Research Objective

| Research Objective | Recommended Methods | Performance Characteristics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Separation | UMAP, PaCMAP, t-SNE | High cluster discrimination (NMI: 0.75-0.82) | Standard parameters may require optimization |

| MOA Identification | TRIMAP, UMAP, PaCMAP | Strong MOA-based grouping (ARI: 0.68-0.74) | Struggles with novel MOA classes |

| Dose-Response Analysis | PHATE, Spectral, t-SNE | Captures continuous gradients | Higher computational requirements |

| Rare Cell Population Detection | Knowledge-guided DR [2] | Enhances rare signal recovery | Requires prior biological knowledge |

Experimental Protocols for DR Application

Standardized Workflow for Transcriptomic DR Analysis

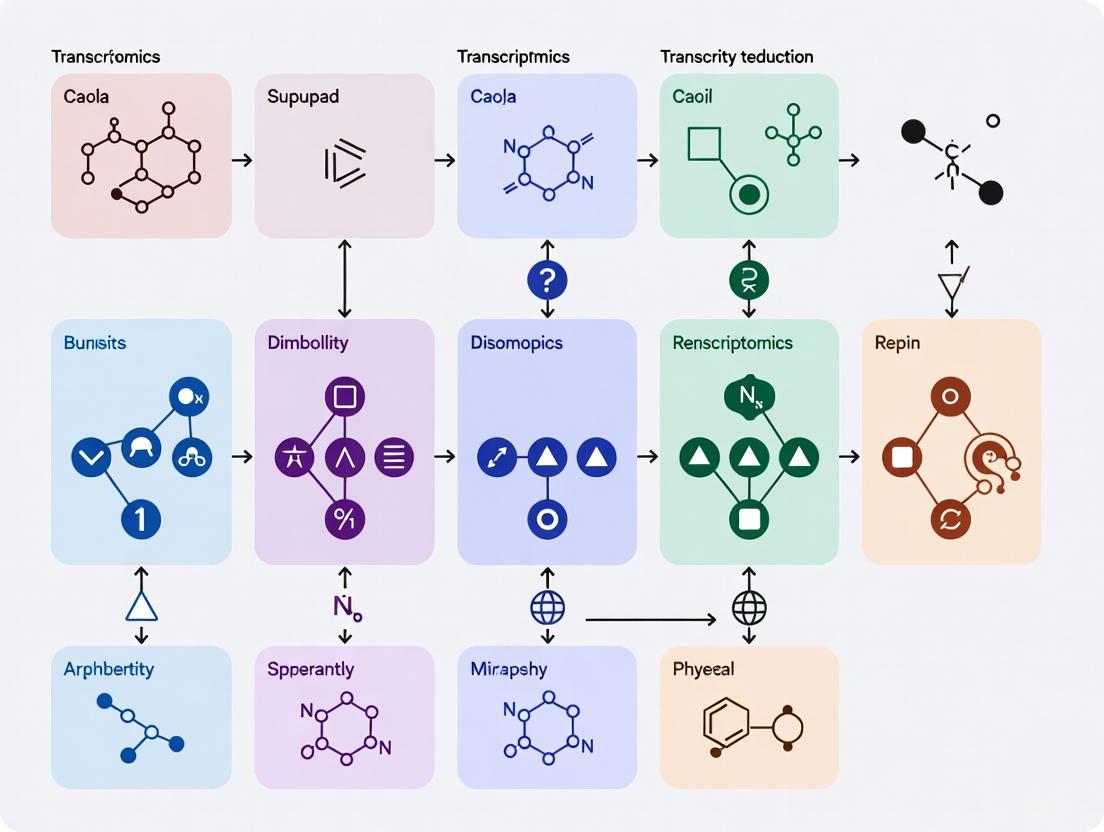

Transcriptomic DR Analysis Workflow

Detailed Protocol for scRNA-seq Data Preprocessing

Protocol Title: Standardized Preprocessing of scRNA-seq Data for Dimensionality Reduction

Introduction: This protocol describes a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline for single-cell RNA sequencing data to ensure optimal performance of subsequent dimensionality reduction methods. Proper preprocessing is critical for removing technical artifacts while preserving biological signals.

Materials:

- Raw scRNA-seq count matrix (genes × cells)

- Computing environment with R (≥4.0) or Python (≥3.8)

- Quality control tools (Seurat, Scanpy, or custom scripts)

- Normalization and feature selection algorithms

Procedure:

Quality Control (QC)

- Filter cells with fewer than 500 detected genes [3]

- Exclude cells with mitochondrial content exceeding 10% [3]

- Remove genes expressed in fewer than 3 cells [3]

- Mathematically, the cell filtering can be represented as:

- ( Ci = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if genes}(i) \geq G{\text{min}} = 500 \text{ and } M(i) \leq 0.1 \ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ) [3]

- Visualize QC metrics (mitochondrial content, gene counts) using violin plots to assess data quality

Normalization

- Apply the LogNormalize method to address sequencing depth variations:

- ( x{ij}' = \log2\left(\frac{x{i,j}}{\sumk x{i,k}} \times 10^4 + 1\right) ) [3]

- where ( x{i,j} ) is the raw expression value of gene j in cell i

- and ( x_{ij}' ) is the normalized expression value

- Apply the LogNormalize method to address sequencing depth variations:

Feature Selection

- Identify Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) using dispersion-based methods:

- Calculate variance-to-mean ratio for each gene: ( \text{Dispersion}j = \frac{\sigmaj^2}{\mu_j} ) [3]

- Select genes with dispersion above a dataset-specific threshold

- Typically retain 2,000-5,000 HVGs for downstream analysis

- Identify Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) using dispersion-based methods:

Dimensionality Reduction Application

- Scale the data to zero mean and unit variance

- Apply selected DR method (t-SNE, UMAP, PaCMAP, etc.) to HVG matrix

- For PaCMAP/UMAP: use default parameters initially (nneighbors=15, mindist=0.1)

- For t-SNE: use perplexity=30, early_exaggeration=12 as starting point

- Generate 2-dimensional embeddings for visualization

Notes:

- Parameter optimization may be required for specific datasets

- Monitor computational resources for large datasets (>50,000 cells)

- Validate biological coherence of results through known marker genes

Advanced Protocol: Knowledge-Guided Dimensionality Reduction

Protocol Title: Knowledge-Guided DR for Rare Cell Population Identification

Introduction: Traditional DR methods may overlook rare but biologically important cell populations. This protocol incorporates prior biological knowledge to guide dimensionality reduction, enhancing detection of rare cell types and subtle subpopulations.

Materials:

- Preprocessed scRNA-seq data (after QC, normalization)

- Curated gene sets of biological interest (e.g., pathway databases, marker genes)

- Computational framework supporting custom similarity metrics

Procedure:

Gene Priority Definition

- Curate gene lists based on prior biological knowledge (e.g., cell-type-specific markers, pathway genes)

- Assign weights to genes based on relevance to biological question

- Create a weighted similarity metric incorporating both expression patterns and gene importance

Modified Distance Calculation

- Implement knowledge-informed distance metric:

- ( D{\text{knowledge}} = \alpha \cdot D{\text{expression}} + \beta \cdot D_{\text{knowledge-priority}} )

- where ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ) are weighting parameters

- Apply modified distance matrix to preferred DR algorithm

- Implement knowledge-informed distance metric:

Validation of Rare Populations

- Assess enrichment of known rare cell markers in identified clusters

- Compare with ground truth data when available

- Evaluate biological plausibility of newly identified subpopulations

Applications:

- Identification of endocrine cell subtypes in pancreatic islets [2]

- Separation of highly similar hematopoietic sub-populations [2]

- Detection of rare senescent cells in tissue samples [2]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Transcriptomic DR

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Dataset | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Connectivity Map (CMap) [1] | Drug-induced transcriptomic profiles for method benchmarking | https://clue.io/cmap |

| Reference Datasets | Human Pancreas scRNA-seq [3] | 16,382 cells, 14 cell types for algorithm validation | Publicly available through cellxgene |

| Reference Datasets | Human Skeletal Muscle scRNA-seq [3] | 52,825 cells, 8 cell types for scalability testing | Publicly available through cellxgene |

| Software Tools | Seurat | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis suite with DR implementations | R package: https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| Software Tools | Scanpy | Python-based single-cell analysis with optimized DR workflows | Python package: https://scanpy.readthedocs.io |

| Software Tools | Cytoscape [4] | Network visualization and biological interpretation | https://cytoscape.org/ |

| Validation Metrics | Silhouette score, DBI, VRC [1] | Internal validation of cluster quality | Standard implementations in scikit-learn |

| Validation Metrics | NMI, ARI [1] | External validation against known labels | Standard implementations in scikit-learn |

Advanced Visualization Principles for DR Outcomes

DR Method Taxonomy and Applications

Accessible Visualization Design for DR Results

Effective visualization of dimensionality reduction outcomes requires careful consideration of color, layout, and labeling to ensure accessibility and interpretability. The following principles should guide visualization design:

Color Selection and Contrast:

- Use the specified color palette (#4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368) consistently across all visualizations

- Ensure text has a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 against background colors [5]

- For adjacent data elements (bars, pie wedges), use solid borders with at least 3:1 contrast ratio between elements [5]

- Never rely on color alone to convey meaning; supplement with shapes, patterns, or direct labeling [5]

Labeling and Annotation Best Practices:

- Use direct labeling positioned adjacent to data points when possible [5]

- Ensure font sizes are legible (at least equivalent to caption font size) [4]

- Provide clear legends, titles, and axis labels that explain the visualization context

- For complex figures, consider using annotations to highlight specific features of interest

Alternative Representations:

- Provide supplemental data tables for all visualizations [5]

- Include detailed figure descriptions that explain the key findings

- Consider alternative layouts such as adjacency matrices for dense networks [4]

- For interactive visualizations, ensure keyboard accessibility and screen reader compatibility

Dimensionality reduction has emerged as an indispensable methodology for extracting biological insights from high-dimensional transcriptomic data. The systematic benchmarking of DR methods reveals that optimal algorithm selection is highly dependent on the specific biological question, with t-SNE, UMAP, PaCMAP, and TRIMAP excelling at discrete classification tasks, while Spectral, PHATE, and t-SNE show superior performance for detecting continuous patterns such as dose-dependent responses [1]. The development of knowledge-guided approaches further enhances our ability to recover rare but biologically critical signals that might otherwise be lost in conventional DR workflows [2].

Future methodological advancements will likely focus on enhancing scalability for increasingly large datasets, improving sensitivity to subtle biological signals, and developing better integration with multi-omics data types. The recent introduction of CP-PaCMAP, which improves upon its predecessor by focusing on maintaining data compactness critical for accurate classification, represents the ongoing innovation in this field [3]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve and drug screening datasets expand, sophisticated dimensionality reduction approaches will remain essential tools for transforming complex high-dimensional data into actionable biological insights with significant implications for drug discovery and therapeutic development.

In the field of transcriptomics, particularly with the advent of high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), researchers routinely encounter datasets where the number of genes (features) far exceeds the number of cells (observations). This high-dimensional landscape poses significant computational and analytical challenges, including increased noise, sparsity, and the curse of dimensionality. Linear dimensionality reduction techniques have emerged as fundamental tools for addressing these challenges by projecting data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving global structures and biological variance. Among these techniques, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) form the cornerstone of many analytical pipelines, enabling researchers to visualize complex data, identify patterns, and perform downstream analyses such as clustering and cell type annotation.

PCA operates by identifying principal components that capture the maximum variance in the data through an orthogonal transformation, making it particularly effective for highlighting dominant sources of biological heterogeneity. In contrast, LDA is a supervised method that seeks to find linear combinations of features that best separate two or more classes, making it invaluable for classification tasks such as cell type identification. The application of these methods has evolved significantly, with numerous variants now available to address specific challenges in transcriptomics data analysis. These developments are particularly crucial as transcriptomics continues to drive discoveries in basic biology, disease mechanisms, and drug development, where accurate interpretation of high-dimensional data can lead to novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers.

Theoretical Foundations of PCA and LDA

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis is a linear dimensionality reduction technique based on the fundamental mathematical operation of eigen decomposition. Given a gene expression matrix X with n cells and p genes, PCA works by identifying a set of orthogonal vectors (principal components) that sequentially capture the maximum possible variance in the data. The first principal component is the direction along which the projection of the data has the greatest variance, with each subsequent component capturing the next greatest variance while remaining orthogonal to all previous components. Mathematically, this is achieved by computing the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of the standardized data, with the eigenvalues representing the amount of variance explained by each component.

The covariance matrix Σ of the data matrix X is computed as Σ = (1/(n-1))(X - μ)ᵀ(X - μ), where μ is the mean vector of the data. The eigenvectors v₁, v₂, ..., vₚ of Σ form the principal components, with corresponding eigenvalues λ₁ ≥ λ₂ ≥ ... ≥ λₚ ≥ 0 representing the variance explained by each component. The original data can then be projected onto a lower-dimensional subspace by selecting the top k eigenvectors corresponding to the largest k eigenvalues, resulting in a reduced representation that preserves the most significant sources of variation in the data.

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

Linear Discriminant Analysis operates under a different objective than PCA—rather than maximizing variance, LDA seeks to find a linear projection that maximizes the separation between predefined classes while minimizing the variance within each class. Given a data matrix X with class labels y₁, y₂, ..., yₙ, LDA computes two scatter matrices: the between-class scatter matrix SB and the within-class scatter matrix SW. The between-class scatter matrix measures the separation between different classes, while the within-class scatter matrix measures the compactness of each class.

Mathematically, these matrices are defined as SB = Σᶜ nᶜ(μᶜ - μ)(μᶜ - μ)ᵀ and SW = Σᶜ Σ{i∈c} (xi - μᶜ)(xi - μᶜ)ᵀ, where nᶜ is the number of points in class c, μᶜ is the mean of class c, and μ is the overall mean of the data. LDA then finds the projection matrix W that maximizes the ratio of the determinant of the between-class scatter matrix to the determinant of the within-class scatter matrix of the projected data: J(W) = |WᵀSBW| / |WᵀSWW|. The solution to this optimization problem is given by the eigenvectors of SW⁻¹S_B corresponding to the largest eigenvalues.

Comparative Strengths and Limitations

The fundamental difference between PCA and LDA lies in their objectives: PCA is unsupervised and seeks directions of maximum variance without regard to class labels, while LDA is supervised and explicitly uses class information to find discriminative directions. This distinction leads to complementary strengths and limitations in transcriptomics applications. PCA is particularly valuable for exploratory data analysis, visualization, and noise reduction when class labels are unavailable or uncertain. However, it may overlook biologically relevant features that discriminate between cell types if those features explain relatively little overall variance. Conversely, LDA typically achieves better separation of predefined cell types but requires accurate prior labeling and may perform poorly when classes are not linearly separable or when the training data is not representative of the full biological diversity.

Advanced Variants and Recent Methodological Developments

Contrastive and Generalized Contrastive PCA

Traditional PCA captures the dominant sources of variation in a single dataset but cannot directly compare patterns across different experimental conditions. Contrastive PCA (cPCA) addresses this limitation by identifying low-dimensional patterns that are enriched in one dataset compared to another. Specifically, cPCA finds directions in which the variance of a "foreground" dataset is maximized while the variance of a "background" dataset is minimized. However, cPCA requires tuning a hyperparameter α that controls the trade-off between these objectives, with no objective criteria for selecting the optimal value.

Generalized Contrastive PCA (gcPCA) was developed to overcome this limitation, providing a hyperparameter-free approach for comparing high-dimensional datasets [6]. gcPCA performs simultaneous dimensionality reduction on two datasets by finding projections that maximize the ratio of variances between them, eliminating the need for manual parameter tuning. This method is particularly valuable in transcriptomics for identifying gene expression patterns that distinguish disease states, treatment conditions, or developmental stages. The mathematical foundation of gcPCA involves a generalized eigenvalue decomposition that directly optimizes the contrast between datasets without introducing arbitrary weighting parameters.

Feature Subspace PCA (FeatPCA)

FeatPCA represents an innovative approach that addresses the challenges of applying PCA to ultra-high-dimensional transcriptomics data [7]. Rather than applying PCA directly to the entire dataset, FeatPCA partitions the feature set (genes) into multiple subspaces, applies PCA to each subspace independently, and then merges the results. This approach offers several advantages: it can capture local gene-gene interactions that might be overlooked in global PCA, reduces the computational burden, and can improve downstream clustering performance.

The FeatPCA algorithm incorporates four distinct strategies for subspace generation:

- Sequential partitioning of genes into equal parts

- Partitioning of randomly shuffled genes

- Random gene selection without replacement

- Random gene selection with replacement Experimental results demonstrate that FeatPCA consistently outperforms standard PCA in clustering accuracy across diverse scRNA-seq datasets, particularly when using the sequential partitioning approach with 20-30% overlap between adjacent partitions [7].

Integrative RECODE (iRECODE)

While not strictly a PCA variant, the RECODE algorithm represents a significant advancement in addressing technical noise in single-cell data using high-dimensional statistics [8]. The recently developed iRECODE extends this approach to simultaneously reduce both technical noise and batch effects while preserving the full dimensionality of the data. iRECODE integrates batch correction within an "essential space" created through noise variance-stabilizing normalization and singular value decomposition, minimizing the computational cost while effectively addressing both technical and batch noise.

A key innovation of iRECODE is its compatibility with established batch correction methods such as Harmony, MNN-correct, and Scanorama, with empirical results showing optimal performance when combined with Harmony [8]. This approach substantially improves cross-dataset comparisons and integration of multi-omics data, enabling more reliable detection of rare cell types and subtle biological variations.

Table 1: Advanced PCA Variants for Transcriptomics Applications

| Method | Key Innovation | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gcPCA [6] | Hyperparameter-free comparison of two datasets | Identifies condition-specific patterns; No manual tuning required | Limited to pairwise comparisons | Identifying disease-specific expression signatures; Treatment vs. control studies |

| FeatPCA [7] | Feature subspace partitioning | Improved clustering; Captures local gene interactions; Reduced computation | Optimal number of partitions dataset-dependent | Large-scale scRNA-seq analysis; Rare cell type identification |

| iRECODE [8] | Dual noise reduction (technical + batch) | Preserves full data dimensions; Compatible with multiple batch methods | Computational intensity for very large datasets | Multi-batch integration; Cross-platform data harmonization |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cell Type Annotation with PCLDA

The PCLDA pipeline represents a robust approach for supervised cell type annotation that combines simple statistical methods with demonstrated high accuracy [9] [10]. Below is a detailed protocol for implementing PCLDA:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing

- Begin with a raw gene expression matrix X ∈ R^(n×p) where n is the number of cells and p is the number of genes.

- Normalize the data using log-transformed library-size normalization: x'ᵢⱼ = log₂(1 + 10⁴ × xᵢⱼ / Σₖ₌₁ᵖ xᵢₖ), where xᵢⱼ is the raw count of gene j in cell i.

- Filter genes using t-test screening based on the transformed expression values. For each cell type c, compute the t-statistic for each gene j comparing type c versus all other cells: Tⱼ,꜀ = (x̄ⱼ,꜀ - x̄ⱼ,ᵣₑₛₜ) / √(s²ⱼ,꜀/n꜀ + s²ⱼ,ᵣₑₛₜ/nᵣₑₛₜ).

- Select the top k genes (typically 300-500) with the highest |Tⱼ,꜀| for each cell type and take the union across all cell types to create a filtered gene set G.

Step 2: Dimensionality Reduction via Supervised PCA

- Apply PCA to the filtered expression matrix X'ᴳ containing only genes in G.

- Rather than selecting principal components (PCs) based on variance explained, choose PCs that maximize class separability using the ratio Rₖ = Varʙ(z:ₖ) / Varᴡ(z:ₖ), where Varʙ and Varᴡ represent between-class and within-class variance, respectively.

- Rank all PCs by Rₖ and retain the top d PCs (typically d=200) with the highest values.

Step 3: LDA Classification

- Train a Linear Discriminant Analysis classifier using the selected PC scores from the training data.

- Apply the trained LDA model to project test data onto the same discriminant axes.

- Assign cell type labels based on the highest posterior probability.

Validation and Interpretation

- Benchmarking across 22 public scRNA-seq datasets has shown that PCLDA achieves top-tier accuracy under both intra-dataset (cross-validation) and inter-dataset (cross-platform) conditions [10].

- The linear nature of PCA and LDA provides strong interpretability, with decision boundaries represented as linear combinations of original gene expression values.

- Top-weighted genes identified by PCLDA consistently capture biologically meaningful signals in enrichment analyses.

Protocol 2: Batch Effect Correction with iRECODE

iRECODE provides a comprehensive solution for addressing both technical noise and batch effects in single-cell data [8]. The protocol consists of the following steps:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Normalization

- Input raw count matrices from multiple batches or experiments.

- Apply noise variance-stabilizing normalization (NVSN) to stabilize technical variance across cells.

Step 2: Essential Space Mapping

- Map the normalized gene expression data to an essential space using singular value decomposition.

- This step reduces the impact of high-dimensional noise while preserving biological signals.

Step 3: Integrated Batch Correction

- Apply batch correction within the essential space using a compatible algorithm (Harmony recommended based on empirical results).

- This integrated approach minimizes computational costs while effectively correcting for batch effects.

Step 4: Variance Modification and Reconstruction

- Apply principal component variance modification and elimination to further reduce technical noise.

- Reconstruct the denoised and batch-corrected gene expression matrix for downstream analyses.

Performance Validation

- Evaluate batch correction effectiveness using integration scores such as local inverse Simpson's index (iLISI) for batch mixing and cell-type LISI (cLISI) for cell-type separation.

- Assess technical noise reduction by examining sparsity reduction and dropout rate improvement in the reconstructed matrix.

- Empirical results show iRECODE reduces relative errors in mean expression values from 11.1-14.3% to 2.4-2.5% while improving computational efficiency approximately 10-fold compared to sequential noise reduction and batch correction [8].

Protocol 3: Spatial Transcriptomics with STAMP

STAMP (Spatial Transcriptomics Analysis with topic Modeling to uncover spatial Patterns) provides interpretable, spatially aware dimension reduction for spatial transcriptomics data [11]. The protocol includes:

Step 1: Data Integration

- Input gene expression counts with spatial coordinates for each cell or spot.

- Construct an adjacency matrix based on spatial locations to capture spatial relationships.

Step 2: Model Configuration

- Configure STAMP based on data type (single section, multiple sections, or time-series data).

- For time-series data, enable the Gaussian process prior with Matern kernel to model temporal variations.

Step 3: Model Training

- Train the STAMP model using black-box variational inference to maximize the evidence lower bound (ELBO).

- The model incorporates a simplified graph convolutional network (SGCN) as an inference network to integrate spatial information.

Step 4: Result Interpretation

- Examine the resulting spatial topics and their spatial distributions.

- Identify dominant topics for each cell and assign corresponding biological interpretations.

- Analyze gene modules associated with each topic, with genes ranked by their contribution to the topic.

Validation and Benchmarking

- STAMP has demonstrated superior performance in identifying anatomical regions in mouse hippocampus data, correctly separating CA1, CA2, CA3, dentate gyrus, and habenula regions where other methods failed [11].

- Evaluation metrics include module coherence (measuring coexpression of top-ranking genes) and module diversity (measuring uniqueness of gene modules), with STAMP achieving superior scores (coherence: 0.162, diversity: 0.9) compared to alternatives.

STAMP Analysis Workflow: Integrating spatial and expression data.

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Quantitative Assessment of PCA Variants

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Linear Dimensionality Reduction Methods

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Computational Efficiency | Batch Effect Correction | Interpretability | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PCA | 72-85 | High | None | Medium | High |

| PCLDA [9] [10] | 89-94 | High | Partial | High | Medium |

| iRECODE [8] | 90-96 | Medium | Excellent | Medium | Medium |

| FeatPCA [7] | 88-93 | Medium-High | None | Medium | High |

| STAMP [11] | 92-95 | Medium | Excellent | High | Medium (up to 500k cells) |

| gcPCA [6] | 85-91 | Medium | None | Medium | Medium |

Application-Specific Recommendations

Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies and empirical evaluations:

- For standard cell type annotation without strong batch effects: PCLDA provides an optimal balance of accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency [9] [10].

- For data integration across multiple batches or platforms: iRECODE delivers superior performance in batch correction while simultaneously reducing technical noise [8].

- For spatial transcriptomics analysis: STAMP outperforms alternative methods in identifying biologically relevant spatial domains with interpretable gene modules [11].

- For large-scale scRNA-seq clustering: FeatPCA demonstrates consistent improvements in clustering accuracy compared to standard PCA [7].

- For comparative analysis across experimental conditions: gcPCA provides a robust, hyperparameter-free approach for identifying condition-specific patterns [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics Dimensionality Reduction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanpy [7] | Software Toolkit | Single-cell analysis in Python | Preprocessing, normalization, and basic dimensionality reduction |

| Harmony [8] | Integration Algorithm | Batch effect correction | Compatible with iRECODE for integrated noise reduction and batch correction |

| STAMP Toolkit [11] | Software Package | Spatially aware topic modeling | Spatial transcriptomics analysis with interpretable dimension reduction |

| gcPCA Toolbox [6] | MATLAB/Python Package | Comparative analysis of two conditions | Identifying patterns enriched in one condition versus another |

| FeatPCA Implementation [7] | Algorithm | Feature subspace PCA | Enhanced clustering of high-dimensional scRNA-seq data |

| PCLDA GitHub Repository [9] [10] | Code Pipeline | Cell type annotation | Supervised classification using PCA and LDA |

Method Selection Guide: Choosing appropriate linear techniques.

Linear dimensionality reduction techniques, particularly PCA, LDA, and their modern variants, continue to play indispensable roles in transcriptomics research. While nonlinear methods have gained popularity for visualization and capturing complex manifolds, linear methods provide unique advantages for preserving global data structure, computational efficiency, and interpretability. The development of specialized variants such as iRECODE for dual noise reduction, FeatPCA for enhanced clustering, gcPCA for comparative analysis, and STAMP for spatial transcriptomics demonstrates the ongoing innovation in this field.

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: (1) further integration of multimodal data types within linear frameworks, (2) improved scalability for massive single-cell datasets exceeding millions of cells, (3) enhanced interpretability through structured sparsity and biological constraints, and (4) tighter integration with experimental design for prospective studies. As transcriptomics continues to evolve toward clinical applications in drug development and personalized medicine, the reliability, interpretability, and computational efficiency of linear dimensionality reduction methods will ensure their continued relevance in the analytical toolkit of researchers and pharmaceutical developers.

For researchers implementing these methods, the key considerations remain matching the method to the specific biological question, understanding the assumptions and limitations of each approach, and employing appropriate validation strategies. When applied judiciously, linear dimensionality reduction techniques provide powerful capabilities for extracting biological insights from high-dimensional transcriptomics data.

In transcriptomics research, high-dimensional data presents a significant challenge for analysis and interpretation. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques are indispensable for visualizing and exploring this complex data, as they aim to uncover the intrinsic low-dimensional manifold upon which the data resides. Among the most prominent methods are t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding), UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection), and PHATE (Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Trajectory Embedding). Each algorithm is founded on distinct mathematical principles, leading to different strengths in preserving various aspects of data structure, such as local neighborhoods, global geometry, or continuous trajectories [12].

The choice of DR method is not merely a procedural step but a critical analytical decision that can shape scientific interpretation. For instance, while t-SNE excels at revealing local cluster structure, it can distort the global relationships between clusters. Conversely, UMAP offers improved speed and some preservation of global structure, but its results can be highly sensitive to parameter settings. PHATE is specifically designed to capture continuous progressions, such as cellular differentiation trajectories, which other methods might incorrectly fragment into discrete clusters [13] [12]. This application note provides a structured comparison and detailed protocols for the application of these three key manifold learning techniques within the context of transcriptomics research.

Performance Comparison and Method Selection

Selecting an appropriate DR method requires a nuanced understanding of how each algorithm balances the preservation of local versus global data structure. The following table provides a quantitative summary of their performance across key metrics, drawing from comprehensive benchmarking studies [1] [13].

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarking of Nonlinear Dimensionality Reduction Methods

| Method | Local Structure Preservation | Global Structure Preservation | Sensitivity to Parameters | Typical Runtime | Ideal Use Case in Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE | High [1] [13] | Low [13] [12] | High (e.g., perplexity) [14] [13] | Medium | Identifying well-separated, discrete cell clusters [1] |

| UMAP | High [1] [13] | Medium [15] [16] | High (e.g., nneighbors, mindist) [14] [13] | Fast | General-purpose visualization; balancing local and global structure [1] |

| PHATE | Medium [13] | High (for trajectories) [12] | Medium [13] | Slow | Revealing branching trajectories, differentiation pathways, and continuous progressions [12] |

| PaCMAP | High [1] [13] | High [15] [13] | Low [15] [13] | Fast | A robust alternative for preserving both local and global structure [13] |

The performance of these methods is not absolute but is influenced by parameter choices and data characteristics. For example, a benchmark on drug-induced transcriptomic data confirmed that t-SNE, UMAP, and PaCMAP were top performers in preserving biological similarity, though most methods struggled with subtle dose-dependent changes, where PHATE and Spectral methods showed stronger performance [1]. Furthermore, studies indicate that UMAP and t-SNE are highly sensitive to parameter choices, and their apparent global structure can be heavily reliant on initialization with PCA [15] [13]. In contrast, methods like PaCMAP are more robust due to their use of additional attractive forces that extend beyond immediate neighborhoods [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cell Atlas Construction from scRNA-seq Data Using UMAP

This protocol details the construction of a cell atlas, a foundational step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, using the Seurat toolkit and UMAP for visualization [17].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Data Preparation

- Input: Processed output files from 10X Genomics Cell Ranger, a Seurat object, or a gene expression matrix (genes x cells).

- Software: R package

Seurator the HemaScope toolkit, which provides a user-friendly interface [17].

Quality Control (QC) and Filtering

- Filter cells based on quality metrics:

- Filter genes detected in fewer than

min.cells(e.g., 3 cells) [3]. - Tool: Use the

CreateSeuratObjectand subset functions in Seurat, or the quality control module in HemaScope.

Normalization and Feature Selection

- Normalize gene expression values for each cell using the

LogNormalizemethod, scaling by 10,000 and log-transforming the result [3] [17]. - Identify Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) using a dispersion-based method (e.g.,

FindVariableFeaturesin Seurat). Typically, the top 2,000 HVGs are selected for downstream analysis [14] [17].

- Normalize gene expression values for each cell using the

PCA and Batch Correction

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the scaled data of the HVGs.

- If dealing with data from multiple batches, use integration methods like

FindIntegrationAnchorsin Seurat to correct for batch effects [17].

UMAP Dimensionality Reduction

- Run UMAP on the top principal components (PCs) from the previous step.

- Critical Parameters:

n_neighbors(default=15): Balances local vs. global structure. Lower values focus on local detail, while higher values capture broader topology [14].min_dist(default=0.01): Controls how tightly points are packed. Lower values allow for denser clusters, while higher values focus on broad structure [14].

- Tool:

RunUMAPfunction in Seurat or the corresponding function in HemaScope.

Clustering and Cell Type Annotation

- Perform unsupervised clustering on the PCA-reduced data using a graph-based method such as the Louvain algorithm (e.g.,

FindClustersin Seurat). - Annotate cell types by finding differentially expressed genes for each cluster and comparing them to known lineage markers [17]. HemaScope integrates seven methods to improve annotation accuracy [17].

- Perform unsupervised clustering on the PCA-reduced data using a graph-based method such as the Louvain algorithm (e.g.,

Output and Interpretation

- Output: A 2D UMAP visualization colored by cluster identity and/or annotated cell type.

- Interpretation: Analyze the spatial relationships between clusters to infer biological relationships, such as the similarity between different cell states or lineages.

Protocol 2: Trajectory Inference for Cellular Dynamics Using PHATE

This protocol uses PHATE to infer continuous processes like differentiation or cellular responses from scRNA-seq data.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input and Software Environment

- Input: A normalized and filtered gene expression matrix from a scRNA-seq experiment.

- Software: Python using the

phatelibrary.

Data Preprocessing

- Import the data and apply any necessary library size normalization and log-transformation if not already performed.

- Optionally, select highly variable genes to reduce noise and computational load.

Running PHATE

- Instantiate the PHATE estimator. Key parameters to consider are:

knn: Number of nearest neighbors for graph construction (similar ton_neighborsin UMAP).decay: Alpha parameter, which controls the influence of the distance kernel.t: The diffusion time scale, which can be automatically selected.

- Fit the model to the data and transform it to obtain the PHATE embedding (typically 2D or 3D).

- Code Example:

- Instantiate the PHATE estimator. Key parameters to consider are:

Visualization and Interpretation

- Plot the resulting PHATE coordinates.

- Color the plot by experimental metadata (e.g., sample time point, cell cycle phase) or expression of key genes to interpret the trajectory.

- Interpretation: Identify the root, branches, and endpoints of the trajectory. Continuous progressions along the manifold suggest a dynamic biological process. PHATE is particularly powerful for visualizing branching relationships that other methods might shatter into clusters [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat R Toolkit | A comprehensive R package designed for the analysis of single-cell transcriptomic data, covering the entire workflow from QC to visualization. | Executing the step-by-step protocol for cell atlas construction [17]. |

| Scanpy (Python) | A scalable Python toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data, analogous to Seurat. | Preprocessing data and performing preliminary clustering before trajectory analysis with PHATE. |

| HemaScope Toolkit | A specialized bioinformatics toolkit with modular designs for analyzing scRNA-seq and ST data from hematopoietic cells, available as an R package, web server, and Docker image [17]. | Streamlined analysis of bone marrow or blood-derived single-cell data with cell-type-specific annotations. |

| Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) | A subset of genes with high cell-to-cell variation, which are most informative for distinguishing cell types and states. | Reducing dimensionality and noise prior to PCA and manifold learning [14] [17]. |

| Lineage Score (LSi) | A parameter designed to quantify the affiliation levels of individual cells to various lineages within the hematopoietic hierarchy [17]. | Quantifying differentiation potential or identifying cell blockage in leukemia studies. |

| Cell Cycle Score (Score~cycle~) | A parameter that classifies single cells into G0, G1, S, and G2/M phases based on gene expression profiles [17]. | Checking and regressing out cell cycle effects, a major source of confounding variation. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The field of manifold learning is rapidly evolving to address its current limitations. A significant challenge is the high sensitivity of methods like t-SNE and UMAP to hyperparameter choices, which can lead to inconsistent results and misinterpretations [13] [18]. In response, new methods like PaCMAP have been developed that demonstrate superior robustness and a better balance between local and global structure preservation [15] [13]. Furthermore, automated manifold learning frameworks are emerging, which select the optimal method and hyperparameters through optimization over representative data subsamples, thereby enhancing scalability and reproducibility [18].

Another frontier is the development of methods with explicit geometric focus. For example, Preserving Clusters and Correlations (PCC) is a novel method that uses a global correlation loss objective to achieve state-of-the-art global structure preservation, significantly outperforming even PCA in this regard [16]. Conversely, in domains like rehabilitation exercise evaluation from skeleton data, leveraging Symmetric Positive Definite (SPD) manifolds has proven powerful for capturing the intrinsic nonlinear geometry of human motion, outperforming Euclidean deep learning methods [19]. These advances highlight a growing trend towards specialized, robust, and geometrically-aware manifold learning techniques that will provide even deeper insights into complex biological systems like those studied in transcriptomics.

Modern transcriptomics research, particularly single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics, generates complex, high-dimensional datasets that present significant analytical challenges. Dimensionality reduction serves as an indispensable step for visualizing cellular heterogeneity, identifying patterns, and preparing data for downstream analyses such as clustering and trajectory inference. While traditional methods like PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP have been widely adopted, they exhibit limitations in preserving both local and global data structures and often lack interpretability. Deep learning approaches, particularly autoencoders and their variants, have emerged as powerful alternatives that offer greater flexibility and capacity to learn meaningful low-dimensional representations. Concurrently, ensemble feature selection methods provide robust frameworks for identifying stable biomarkers from transcriptomic profiles. The integration of these approaches—autoencoders for representation learning and ensemble methods for feature selection—represents a cutting-edge paradigm for advancing transcriptomics research and biomarker discovery, offering enhanced performance, biological interpretability, and robustness for applications in basic research and drug development.

Autoencoder Architectures for Transcriptomic Data

Fundamental Concepts and Architectures

Autoencoders are neural network architectures designed to learn efficient representations of data through an encoder-decoder framework. In transcriptomics, the encoder component transforms high-dimensional gene expression vectors into a lower-dimensional latent space, while the decoder attempts to reconstruct the original input from this compressed representation. The model is trained by minimizing the reconstruction error, forcing the latent space to capture the most salient patterns in the transcriptomic data. The fundamental advantage of autoencoders over linear methods like PCA is their ability to model nonlinear relationships between genes and cell states, which are ubiquitous in biological systems.

Variational autoencoders (VAEs) introduce a probabilistic framework by encoding inputs as distributions rather than fixed points in latent space. This approach regularizes the latent space and enables generative sampling, which has proven valuable for modeling transcriptomic variability and generating synthetic data for augmentation. For scRNA-seq data specifically, specialized architectures like the deep count autoencoder (DCA) model count-based distributions with negative binomial loss functions, better accommodating the zero-inflated nature of single-cell data [20] [21].

Advanced Autoencoder Implementations

Recent research has produced sophisticated autoencoder variants tailored to specific transcriptomic applications:

Boosting Autoencoder (BAE): This innovative approach replaces the standard neural network encoder with componentwise boosting, resulting in a sparse mapping where each latent dimension is characterized by a small set of explanatory genes. The BAE incorporates structural assumptions through customizable constraints, such as disentanglement (ensuring different dimensions capture complementary information) or temporal coupling for time-series data. This architecture simultaneously performs dimensionality reduction and identifies interpretable gene sets associated with specific latent dimensions, effectively bridging representation learning and biomarker discovery [22].

Graph-Based Autoencoders: For spatial transcriptomics, graph-based autoencoders integrate gene expression with spatial coordinates and imaging data. The STACI framework creates a joint representation that incorporates gene expression, cellular neighborhoods, and chromatin images in a unified latent space. This multimodal integration enables novel analyses such as predicting gene expression from nuclear morphology and identifying spatial domains with coupled molecular and morphological features [23].

Two-Part Generalized Gamma Autoencoder (AE-TPGG): Specifically designed for scRNA-seq data, this model addresses the bimodal expression pattern (zero vs. positive values) and right-skewed distribution of positive counts using a two-part generalized gamma distribution. This statistical framing provides improved imputation and denoising alongside dimensionality reduction, enhancing downstream analyses by accounting for the specific characteristics of single-cell data [21].

Table 1: Autoencoder Architectures for Transcriptomics

| Architecture | Key Features | Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Probabilistic latent space, generative capability | Regularized latent space, models uncertainty | Single-cell analysis, data augmentation |

| Boosting Autoencoder (BAE) | Componentwise boosting encoder, sparse gene sets | Interpretable dimensions, structural constraints | Cell type identification, time-series analysis |

| Graph-Based Autoencoder | Incorporates spatial relationships, multimodal integration | Preserves spatial context, combines imaging & transcriptomics | Spatial transcriptomics, tissue domain identification |

| AE-TPGG | Two-part generalized gamma model for count data | Handles zero-inflation, provides denoising | scRNA-seq imputation, differential expression |

Ensemble and Hybrid Feature Selection Methods

Ensemble Feature Selection Frameworks

Ensemble feature selection (EFS) strategies address the instability of individual feature selection methods by combining multiple selectors to produce more robust and reproducible gene signatures. Two primary EFS approaches have emerged: homogeneous EFS (Hom-EFS), which applies a single feature selection algorithm to multiple perturbed versions of the dataset (data-level perturbation), and heterogeneous EFS (Het-EFS), which applies multiple different feature selection algorithms to the same dataset (method-level perturbation). Both approaches aggregate results across iterations to identify consistently selected features, reducing dependence on particular data subsets or algorithmic biases [24] [25].

Hybrid ensemble feature selection (HEFS) combines both data-level and method-level perturbations, offering enhanced stability and predictive power. By integrating variability at both endpoints, HEFS disrupts associations of good performance with any single dataset, algorithm, or specific combination thereof. This approach is particularly valuable for genomic biomarker discovery, where reproducibility across studies remains challenging. HEFS implementations typically incorporate diverse feature selection methods (filters, wrappers, and embedded methods) with various resampling strategies, capitalizing on their complementary strengths to identify robust biomarker signatures [24].

Implementation Considerations for Transcriptomics

Designing effective HEFS strategies requires careful consideration of multiple components. For the initial feature reduction step, commonly used approaches include differential expression analysis (DEG) or variance filtering. Resampling strategies must balance representativeness, with distribution-balanced stratified sampling often outperforming random stratified sampling for imbalanced transcriptomic data. The wrapper component typically involves aggregating thousands of machine learning models with different hyperparameter configurations to explore intra-algorithm variability, while embedded methods provide algorithm-specific feature importance measures. Finally, aggregation protocols determine how features are ranked and selected across all perturbations, with stability-based ranking often prioritizing features that consistently appear across multiple iterations and algorithms [24].

Table 2: Hybrid Ensemble Feature Selection Components

| Component | Options | Considerations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Feature Reduction | DEG, Variance filtering | Stringency affects downstream performance | Moderate stringency to retain biological signal |

| Resampling Strategy | Random stratified, Distribution-balanced stratified | Critical for imbalanced data | Distribution-balanced for class imbalance |

| Feature Selection Methods | Filters (SU, GR), Wrappers (RF, SVM), Embedded (LASSO) | Diversity improves robustness | Combine methods from different categories |

| Aggregation Protocol | Rank-based, Stability-weighted, Performance-weighted | Affects final signature composition | Stability-weighted ranking for reproducibility |

Integrated Protocols for Transcriptomics Applications

Protocol: Boosting Autoencoder for Cell Type Identification

Objective: To identify distinct cell populations and their characteristic marker genes from scRNA-seq data using the Boosting Autoencoder approach.

Materials:

- scRNA-seq count matrix (cells × genes)

- High-performance computing environment with GPU acceleration

- BAE implementation (https://github.com/NiklasBrunn/BoostingAutoencoder)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Quality control: Filter cells with high mitochondrial content and low gene detection.

- Normalize counts using library size normalization and log-transform.

- Select highly variable genes for analysis input.

Model Configuration:

- Initialize BAE architecture with disentanglement constraint.

- Set latent dimension based on expected cellular complexity (typically 10-30 dimensions).

- Configure boosting parameters: number of boosting iterations (typically 100-500), learning rate (typically 0.01-0.1), and sparsity constraint.

Model Training:

- Split data into training (80%) and validation (20%) sets.

- Train model using reconstruction loss minimization with early stopping.

- Monitor training and validation loss to prevent overfitting.

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Extract sparse weight matrix linking genes to latent dimensions.

- For each latent dimension, identify top-weighted genes as potential markers.

- Project cells into latent space for visualization and clustering.

- Validate identified gene sets against known cell type markers.

Troubleshooting:

- If latent dimensions fail to capture biological structure, adjust sparsity constraint.

- If model fails to converge, reduce learning rate or increase boosting iterations.

- If gene sets lack specificity, strengthen disentanglement constraint.

Protocol: Hybrid Ensemble Feature Selection for Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To identify robust transcriptomic biomarkers for cancer stage classification using hybrid ensemble feature selection.

Materials:

- RNA-seq expression matrix (samples × genes) with clinical annotations

- Computational environment supporting parallel processing

- HEFS implementation (Python/R frameworks)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Annotate samples by disease stage (e.g., Stage IV vs. Normal).

- Perform standard RNA-seq preprocessing: normalization, batch correction.

- Split data into discovery (70%) and validation (30%) cohorts.

HEFS Configuration:

- Initial Feature Reduction: Apply variance filtering (top 5,000 genes) and differential expression analysis (FDR < 0.05).

- Resampling Strategy: Implement repeated holdout with distribution-balanced stratification (20 iterations, 80/20 splits).

- Feature Selectors: Configure multiple filter methods (Wx, Symmetrical Uncertainty, Gain Ratio) and wrapper methods (Random Forest, SVM with linear kernel).

- Aggregation Method: Apply stability-based ranking with minimum 50% selection frequency threshold.

Ensemble Execution:

- Execute HEFS pipeline on discovery cohort.

- For each resampling iteration, apply all feature selectors to reduced feature sets.

- Aggregate results across all iterations and methods.

- Rank features by selection frequency and predictive importance.

Validation and Interpretation:

- Evaluate final feature set using independent validation cohort.

- Assess predictive performance with multiple classifiers (logistic regression, random forest).

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on identified gene signature.

- Compare with known cancer biomarkers in literature.

Troubleshooting:

- If signature size is too large, increase selection frequency threshold.

- If performance is poor on validation, adjust initial feature reduction stringency.

- If computational requirements are excessive, reduce resampling iterations or feature selectors.

Performance Evaluation and Comparative Analysis

Benchmarking Dimensionality Reduction Methods

Comprehensive evaluation of dimensionality reduction methods should consider multiple performance dimensions: preservation of local structure (neighborhood relationships), preservation of global structure (inter-cluster relationships), sensitivity to parameter choices, sensitivity to preprocessing choices, and computational efficiency. Recent systematic evaluations reveal significant differences among popular DR methods across these criteria [13].

For local structure preservation, measured by metrics such as neighborhood preservation or supervised classification accuracy in low-dimensional space, t-SNE and its optimized variant art-SNE typically achieve the highest scores, followed closely by UMAP and PaCMAP. For global structure preservation, measured by metrics such as distance correlation or rank-based measures, PCA, TriMap, and PaCMAP demonstrate superior performance. Notably, no single method excels across all criteria, necessitating method selection based on analytical priorities. Autoencoder-based approaches generally offer a favorable balance, particularly when incorporating structural constraints or specialized architectures for transcriptomic data [13].

Evaluating Feature Selection Stability

For feature selection methods, evaluation extends beyond predictive accuracy to include stability—the sensitivity of selected features to variations in the training data. Ensemble methods, particularly hybrid approaches, significantly improve stability compared to individual feature selectors. Quantitative assessment involves measuring the overlap between feature sets selected from different data perturbations, with Jaccard index and consistency index being common metrics. HEFS approaches demonstrate substantially higher stability while maintaining competitive predictive performance, making them particularly valuable for biomarker discovery where reproducibility across studies is essential [24] [25].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

| Method | Local Structure | Global Structure | Parameter Sensitivity | Interpretability | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Low | High | Low | Medium (Dense) | Initial exploration, linear data |

| t-SNE | High | Low | High | Low | Visualization of local clusters |

| UMAP | High | Medium | High | Low | Visualization, balance local/global |

| VAE | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium (Post-hoc) | Nonlinear data, generative tasks |

| BAE | Medium | Medium | Medium | High (Sparse) | Interpretable dimensions, marker discovery |

Table 4: Computational Tools for Autoencoder and Ensemble Approaches

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAE Implementation | Software Package | Boosting autoencoder for interpretable dimensionality reduction | GitHub: NiklasBrunn/BoostingAutoencoder |

| STACI Framework | Integrated Pipeline | Graph-based autoencoder for spatial transcriptomics with chromatin imaging | Custom implementation [23] |

| AE-TPGG | Specialized Autoencoder | scRNA-seq imputation and dimensionality reduction with generalized gamma model | Custom implementation [21] |

| Hybrid EFS Framework | Feature Selection | Python package for hybrid ensemble feature selection | Python Package Index |

| DCA | Deep Count Autoencoder | Denoising autoencoder for scRNA-seq data | GitHub: scverse/dca |

| Scanpy | Ecosystem | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis including autoencoder integration | Python Package Index |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Case Study: Identifying Cancer Biomarkers

Hybrid ensemble feature selection has been successfully applied to identify robust biomarkers for cancer stage classification across multiple cancer types. In a comprehensive study analyzing Stage IV colorectal cancer (CRC), Stage I kidney cancer (KIRC), Stage I lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), and Stage III endometrial cancer (UCEC), HEFS identified stable gene signatures that generalized well to independent validation datasets. The approach demonstrated advantages over individual feature selectors by producing more generalizable and stable results that were robust to both data and functional perturbations. Notably, the identified signatures showed high enrichment for cancer-related genes and pathways, supporting their biological relevance and potential translational applications [24].

Case Study: Spatial Transcriptomics in Alzheimer's Disease

The STACI framework, which integrates spatial transcriptomics with chromatin imaging using graph-based autoencoders, has revealed novel insights into Alzheimer's disease progression. By jointly analyzing gene expression, nuclear morphology, and spatial context in mouse models of Alzheimer's, researchers identified coupled alterations in gene expression and nuclear morphometry associated with disease progression. This integrative approach enabled the prediction of spatial transcriptomic patterns from chromatin images alone, providing a potential pathway for reducing experimental costs while maintaining comprehensive molecular profiling. The identified multimodal biomarkers offer new perspectives on the relationship between nuclear architecture, gene expression, and neuropathology in Alzheimer's disease [23].

Case Study: Drug Response Prediction

Ensemble approaches have shown promising results in predicting drug responses using multi-omics features. In one study implementing an ensemble of machine learning algorithms to analyze the correlation between genetic features (mutations, copy number variations, gene expression) and IC50 values as a measure of drug efficacy, researchers identified a highly reduced set of 421 critical features from an original pool of 38,977. Notably, copy number variations emerged as more predictive of drug response than mutations, suggesting a need to reevaluate traditional biomarkers for drug response prediction. This approach demonstrates the potential of ensemble methods for advancing personalized medicine by identifying robust predictors of therapeutic efficacy [26].

High-dimensional transcriptomic data presents significant challenges for analysis and interpretation due to its inherent complexity, sparsity, and noise [1]. Dimensionality reduction (DR) serves as a crucial preprocessing step to improve signal-to-noise ratio and mitigate the curse-of-dimensionality, enabling downstream analyses such as cell type identification, trajectory inference, and spatial domain detection [27]. The core premise of this application note establishes that the geometric assumptions embedded within DR algorithms must align with the intrinsic geometry of the transcriptomic data to achieve optimal performance [28]. Real-world biological data often exhibits inherently non-Euclidean structures—including hierarchical relationships, multi-way interactions, and complex spatial dependencies—that prove challenging to represent effectively within conventional Euclidean space [28]. This alignment between data geometry and algorithmic foundation directly impacts analytical outcomes in drug discovery research, influencing molecular mechanism of action (MOA) identification, drug efficacy prediction, and off-target effect detection [1].

Theoretical Foundations: Data Geometries and Algorithmic Alignment

Geometric Spaces for Data Representation

Table 1: Characteristics of Geometric Spaces for Data Representation

| Geometric Space | Curvature | Strengths | Ideal Data Structures | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | Zero (Flat) | Intuitive distance metrics; Computational efficiency; Natural compatibility with linear algebra | Isotropic data; Globally linear relationships; Data without hierarchical organization | PCA; t-SNE; UMAP (standard) |

| Hyperbolic | Negative | Efficient representation of hierarchical structures; Exponential growth capacity; Minimal distortion for tree-like data | Taxonomies; Concept hierarchies; Biological phylogenies; Knowledge graphs | Poincaré embeddings; Hyperbolic neural networks |

| Spherical | Positive | Natural representation of directional data; Suitable for angular relationships and bounded data | Protein structures; Cellular orientation; Cyclical biological processes | Spherical embeddings; von Mises-Fisher distributions |

| Mixed-Curvature | Variable | Flexibility to capture heterogeneous structures; Adaptability to complex multi-scale data | Real-world datasets combining hierarchical, cyclic, and linear relationships | Product space embeddings; Multi-geometry architectures |

The limitations of Euclidean space become particularly evident when dealing with biological data exhibiting hierarchical organization, such as cellular differentiation pathways or gene regulatory networks [28]. Hyperbolic spaces, with their negative curvature, excel at representing hierarchical structures with minimal distortion in low dimensions, effectively modeling exponential expansion—a property inherent to tree-like structures such as taxonomic classifications and lineage hierarchies [28]. Spherical geometries, characterized by positive curvature, provide optimal representation for data with inherent periodicity or directional constraints, including seasonal gene expression patterns or protein structural orientations [28]. For the complex, heterogeneous nature of transcriptomic data, mixed-curvature approaches that combine multiple geometric spaces offer enhanced flexibility to capture diverse local structures within the same embedding [28].

Algorithmic Alignment in Deep Learning

Algorithmic alignment theory provides a mathematical foundation explaining why certain neural network architectures demonstrate superior performance on specific computational tasks [29]. A network better aligned with a target algorithm's structure requires fewer training examples to achieve generalization [29]. In transcriptomics, this principle manifests when graph neural networks (GNNs) align with dynamic programming algorithms for pathfinding problems, enabling more effective capture of cellular trajectory relationships [29]. The encode-process-decode paradigm exemplifies this alignment through parameter-shared processor networks that can be iterated for variable computational steps, mirroring the iterative nature of many biological algorithms [29].

Figure 1: Framework for aligning data geometry with appropriate algorithms to optimize analytical performance.

Benchmarking Dimensionality Reduction Methods in Transcriptomics

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Dimensionality Reduction Methods on Drug-Induced Transcriptomic Data (CMap Dataset) [1]

| DR Method | Geometric Foundation | Cell Line Separation (DBI) | MOA Classification (NMI) | Dose-Response Detection | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaCMAP | Euclidean (optimized) | 0.91 | 0.87 | Moderate | High |

| TRIMAP | Euclidean (triplet-based) | 0.89 | 0.85 | Moderate | High |

| t-SNE | Euclidean (neighborhood) | 0.88 | 0.84 | Strong | Moderate |

| UMAP | Euclidean (manifold) | 0.87 | 0.83 | Moderate | High |

| PHATE | Euclidean (diffusion) | 0.79 | 0.76 | Strong | Low |

| Spectral | Graph-based | 0.81 | 0.78 | Strong | Moderate |

| PCA | Euclidean (linear) | 0.62 | 0.58 | Weak | Very High |

| NMF | Euclidean (non-negative) | 0.53 | 0.51 | Weak | High |

Benchmarking studies using the Connectivity Map (CMap) dataset—comprising millions of gene expression profiles across hundreds of cell lines exposed to over 40,000 small molecules—reveal significant performance variations among DR methods [1]. The evaluation assessed 30 DR algorithms across four experimental conditions: different cell lines treated with the same compound, single cell line treated with multiple compounds, single cell line treated with compounds targeting distinct MOAs, and single cell line treated with varying dosages of the same compound [1]. Methods incorporating neighborhood preservation (t-SNE, UMAP) and distance-based constraints (PaCMAP, TRIMAP) consistently outperformed linear techniques (PCA) in preserving biological similarity, particularly evident in their superior Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) scores [1]. For detecting subtle dose-dependent transcriptomic changes, diffusion-based (PHATE) and spectral methods demonstrated enhanced sensitivity compared to neighborhood-preservation approaches [1].

Spatial Transcriptomics Considerations

Spatial transcriptomics technologies introduce additional geometric considerations through spatial neighborhood relationships between cells or spots [27]. Methods specifically designed for spatial transcriptomics, such as GraphPCA, incorporate spatial coordinates as graph constraints within the dimension reduction process, explicitly preserving spatial relationships in the embedding [27]. GraphPCA leverages a spatial neighborhood graph (k-NN graph by default) to enforce that adjacent spots in the original tissue remain proximate in the low-dimensional embedding, significantly enhancing spatial domain detection accuracy compared to geometry-agnostic methods [27]. This spatial constraint approach demonstrated robust performance across varying sequencing depths, noise levels, spot sparsity, and expression dropout rates, maintaining high Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) scores even at 60% dropout rates [27].

Experimental Protocols and Application Guidelines

Protocol: Geometry-Aware Dimensionality Reduction for Transcriptomics

Protocol Title: Geometry-aware dimensionality reduction for drug response analysis in transcriptomics

Purpose: To provide a standardized methodology for selecting and applying dimensionality reduction methods based on the intrinsic geometry of transcriptomic data for drug discovery applications.

Materials:

- Transcriptomic dataset (e.g., CMap, GEO accession)

- Computational environment (Python/R)

- DR method implementations (scanpy, scikit-learn, specialized packages)

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing

- Normalize raw count data using scTransform or similar variance-stabilizing transformation

- Filter low-expression genes (detection in <10% of cells/samples)

- Regress out technical covariates (batch effects, sequencing depth)

Exploratory Geometry Assessment

- Compute intrinsic dimensionality using nearest neighbor regression

- Assess hierarchical structure using clustering stability metrics

- Evaluate spatial autocorrelation (for spatial transcriptomics)

- Analyze neighborhood preservation in preliminary PCA embedding

Method Selection Matrix

- Hierarchical Data: Apply hyperbolic embeddings (Poincaré maps)

- Spatial Data: Implement GraphPCA or STAGATE with spatial constraints

- Dose-Response Trajectories: Utilize PHATE or diffusion maps

- Global Structure Preservation: Employ PaCMAP or UMAP

- Local Neighborhood Emphasis: Apply t-SNE or TRIMAP

Parameter Optimization

- For neighborhood-based methods: sweep perplexity (5-50) for t-SNE

- For UMAP: optimize nneighbors (5-100) and mindist (0.001-0.5)

- For GraphPCA: tune spatial constraint parameter λ (0.2-0.8)

- Validate using internal clustering metrics (Silhouette score, DBI)

Validation and Interpretation

- Assess biological coherence using known cell type markers

- Evaluate dose-response gradient preservation (if applicable)

- Verify spatial domain continuity (for spatial transcriptomics)

- Compare with ground truth annotations (when available)

Troubleshooting:

- Poor separation: Increase embedding dimensions or adjust neighborhood size

- Computational constraints: Implement approximate nearest neighbors

- Over-smoothing: Reduce spatial constraint strength in GraphPCA

- Instability: Increase random state iterations or use ensemble approaches

Table 3: Essential Resources for Geometry-Aware Transcriptomics Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Function | Geometric Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | Connectivity Map (CMap) | Reference drug-induced transcriptomic profiles | All geometries |

| 10X Visium Spatial Data | Annotated spatial transcriptomics datasets | Spatial geometries | |

| Allen Brain Atlas | Anatomical reference for validation | Spatial geometries | |

| Computational Libraries | Scikit-learn | Standard DR implementations (PCA, t-SNE) | Euclidean |

| Scanpy | Single-cell analysis pipeline | Euclidean, Graph | |

| Hyperboliclib | Hyperbolic neural network components | Hyperbolic | |

| Geomstats | Riemannian geometry operations | Multiple manifolds | |

| Specialized Algorithms | GraphPCA | Graph-constrained PCA for spatial data | Spatial graphs |

| PHATE | Diffusion geometry for trajectory inference | Trajectory geometry | |

| PaCMAP | Neighborhood preservation for visualization | Euclidean | |

| STAGATE | Graph attention for spatial domains | Spatial graphs | |

| Validation Metrics | Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | Cluster similarity measurement | All geometries |

| Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) | Information-theoretic alignment | All geometries | |

| Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) | Internal cluster validation | All geometries | |

| Trajectory Conservation Score | Pseudotemporal ordering preservation | Trajectory geometry |

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for geometry-aware dimensionality reduction in transcriptomics.