Discriminating True SNPs from Bisulfite Conversion Artifacts: A Comprehensive Guide for Genomic Researchers

Accurately discriminating true single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from artifacts introduced by bisulfite conversion is a critical challenge in epigenomic studies.

Discriminating True SNPs from Bisulfite Conversion Artifacts: A Comprehensive Guide for Genomic Researchers

Abstract

Accurately discriminating true single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from artifacts introduced by bisulfite conversion is a critical challenge in epigenomic studies. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of how bisulfite treatment confounds variant calling, the methodologies and specialized computational tools developed to address this, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing protocols, and a comparative evaluation of validation techniques. By synthesizing current knowledge and best practices, this guide aims to empower scientists to improve the accuracy of their genetic and epigenetic analyses, ensuring more reliable data for downstream applications in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

The Fundamental Challenge: How Bisulfite Conversion Creates SNP-like Artifacts

Bisulfite conversion is a fundamental technique in epigenetics that allows for the detection of DNA methylation at single-base resolution. The core principle involves the selective deamination of unmethylated cytosines to uracils upon treatment with sodium bisulfite, while methylated cytosines (5-methylcytosines) remain unchanged. During subsequent PCR amplification, uracils are read as thymines, creating sequence differences that distinguish methylated from unmethylated cytosines. Despite its status as the gold standard for decades, this chemical process presents significant challenges including DNA fragmentation, substantial DNA loss, and potential artifacts in SNP discrimination, which are crucial considerations for research on genetic and epigenetic variation [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of incomplete bisulfite conversion and how can they be mitigated? Incomplete conversion typically results from degraded or old bisulfite reagent, insufficient mixing of reaction components, or the presence of impurities in the DNA sample. To ensure complete conversion: always prepare fresh CT Conversion Reagent when possible, mix samples thoroughly until no mixing lines are visible, and ensure all liquid is at the bottom of the tube before thermal cycling. Particulate matter in the conversion reagent should be removed by centrifugation, using only the clear supernatant for conversion [3] [4].

Q2: Why does bisulfite conversion cause extensive DNA fragmentation and how does this impact downstream applications? The harsh chemical conditions of traditional bisulfite conversion, including high temperature, extreme pH, and long incubation times, directly damage DNA through depurination and backbone cleavage. This results in severe fragmentation that limits downstream applications, particularly for low-quality and low-quantity samples such as cell-free DNA or forensic samples. The fragmentation reduces the amplifiable template and can lead to failure in applications requiring longer amplicons [1] [2].

Q3: What specific challenges does bisulfite conversion create for distinguishing true methylation from SNP variants? After bisulfite treatment, the reduced sequence complexity (effectively creating a 3-letter genome: A, G, T) complicates the alignment of sequencing reads and discrimination of C/T polymorphisms from true methylation signals. This is particularly problematic when analyzing genetically diverse populations where SNP variation is common. Specialized bioinformatics tools like Bismark and BWA meth are required, and paired-end sequencing is recommended to help discriminate between true unmethylated cytosines and SNP variants [5] [6].

Q4: What are the key considerations for PCR amplification after bisulfite conversion? Successful amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA requires: (1) primers 24-32 nucleotides in length designed to bind the converted template, with no more than 2-3 mixed bases; (2) using hot-start Taq polymerase (not proof-reading enzymes) as they can read through uracils in the template; (3) targeting shorter amplicons (~200 bp) due to DNA fragmentation; and (4) using appropriate template amounts (2-4 µl of eluted DNA, not exceeding 500 ng per reaction) [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low DNA Recovery After Bisulfite Conversion

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive DNA fragmentation during conversion process.

- Solution: Optimize conversion conditions using newer methods like Ultra-Mild Bisulfite Sequencing (UMBS-seq) which reduces DNA damage through optimized bisulfite concentration and pH [2].

- Cause: Overly long desulphonation step.

- Solution: Strictly limit desulphonation time to 15 minutes maximum (20 minutes is absolute upper limit) to prevent additional degradation [4].

- Cause: Inefficient purification during cleanup steps.

- Solution: For enzymatic conversion methods, optimize the bead-based cleanup steps which are critical for recovery [1].

Problem: Incomplete Cytosine Conversion

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Degraded or improperly prepared bisulfite reagent.

- Solution: Prepare fresh conversion reagent before each use and protect from light and oxygen exposure during processing [4].

- Cause: Incomplete denaturation or reaction conditions.

- Solution: Ensure proper thermal cycler settings with heated lid to prevent precipitation, thorough mixing of samples, and complete centrifugation before reactions [3] [4].

- Cause: Low DNA input amounts.

- Solution: Use adequate DNA input (≥5 ng for bisulfite conversion, ≥10 ng for enzymatic conversion) and consider alternative methods like enzymatic conversion or UMBS-seq for low-input scenarios [1] [2].

Problem: High Background or False Positives in Methylation Detection

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete bisulfite conversion leading to residual cytosines.

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control measures including qBiCo assay to assess conversion efficiency, or use colony Sanger sequencing to verify conversion [1] [4].

- Cause: SNP variants interfering with methylation calling.

- Solution: Utilize paired-end sequencing and bioinformatic tools like MethylDackel that can discriminate between true unmethylated cytosines and SNPs by analyzing opposite strand information [6].

- Cause: Stochastic effects in low-template samples.

- Solution: Increase sequencing depth and implement depth filters in analysis to ensure reliable methylation calls [6].

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Conversion Methods for Methylation Analysis

| Parameter | Traditional Bisulfite | Enzymatic Conversion | UMBS-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Input Range | 0.5-2000 ng [1] | 10-200 ng [1] | As low as 10 pg [2] |

| Conversion Efficiency | ~99.9% [2] | >99% (but higher variability) [2] | ~99.9% [2] |

| DNA Recovery | Overestimated (130%) [1] | Low (40%) [1] | High [2] |

| Fragmentation Level | High (14.4 ± 1.2) [1] | Low-Medium (3.3 ± 0.4) [1] | Significantly Reduced [2] |

| Background Signal | <0.5% [2] | >1% at low inputs [2] | ~0.1% [2] |

| Protocol Duration | 12-16 hours [1] | 6 hours [1] | 90 minutes [2] |

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for Bisulfite Sequencing Analysis

| Tool | Mapping Efficiency | Key Features | SNP Discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismark | Lower (reference: BWA meth) [6] | Most widely used, integrates mapping and extraction [6] | Standard filtering |

| BWA meth | 45-50% higher than Bismark [6] | Faster, uses BWA mem algorithm [6] | Better with paired-end data |

| MethylDackel | N/A (methylation extractor) [6] | Works with BWA meth output [6] | Excellent: uses opposite strand G content to filter SNPs [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Bisulfite Conversion for Illumina Arrays

Materials:

- EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [4]

- High-quality genomic DNA (≥250 ng for manual, ≥1000 ng for automated) [4]

- Thermal cycler with heated lid [4]

Procedure:

- DNA Quality Assessment: Quantify DNA using dsDNA-specific methods (Qubit or Picogreen), not spectrophotometry [4].

- Conversion Reaction: Add CT Conversion Reagent to DNA samples, mix thoroughly until no lines visible [3].

- Incubation: Perform 16 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds and 50°C for 60 minutes in thermal cycler with heated lid [4].

- Cleanup: Use provided columns and buffers for desulphonation and washing.

- Elution: Elute in 10-20 μL elution buffer [1] [4].

Quality Control:

- Assess conversion efficiency using qBiCo assay or similar QC method [1].

- Expected DNA yield: 70-80% of input [4].

Protocol 2: UMBS-seq for Low-Input and Fragmented DNA

Materials:

- Optimized UMBS reagent (100 μL of 72% ammonium bisulfite + 1 μL of 20 M KOH) [2]

- DNA protection buffer [2]

Procedure:

- DNA Denaturation: Perform alkaline denaturation of DNA samples.

- UMBS Treatment: Incubate with UMBS reagent at 55°C for 90 minutes [2].

- Cleanup and Desulphonation: Standard procedures following treatment.

- Library Preparation: Proceed with standard bisulfite sequencing library prep.

Advantages:

- Significantly reduced DNA damage compared to conventional bisulfite [2].

- Higher library yields and complexity, especially with low-input samples [2].

- Better preservation of cfDNA fragment profiles [2].

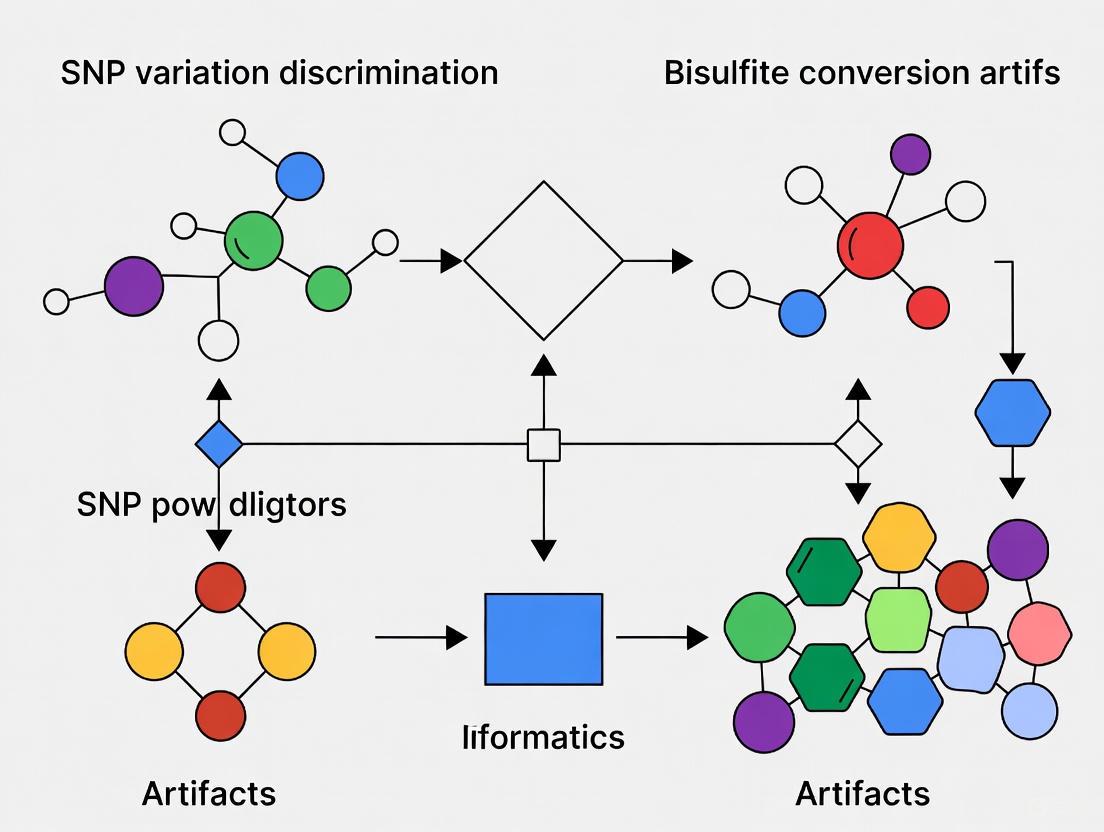

Method Workflow and SNP Discrimination

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Bisulfite-Based Methylation Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [1] [4] | Standard bisulfite conversion | Illumina methylation arrays, general BS-seq |

| NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit [1] [2] | Enzyme-based conversion | Low-input samples, long fragment applications |

| UMBS Reagent [2] | Mild chemical conversion | cfDNA, FFPE, low-input degraded samples |

| Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase [3] | PCR amplification of converted DNA | Targeted bisulfite sequencing, validation |

| Bisulfite Conversion Control Probes [4] | Quality assessment | Verification of conversion efficiency |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the core "Strand Complementarity Problem" in bisulfite sequencing?

- A: Standard SNP callers assume that the two strands of DNA are complementary. However, in bisulfite-treated DNA, unmethylated cytosines (C) are converted to thymines (T), making the two strands non-complementary. Using a standard caller violates this fundamental assumption, leading to a high false positive rate for C>T and G>A SNPs, which are the most common substitution types in the human population [7] [8].

Q2: What specific errors does this problem cause?

- A: The primary errors are:

- Misidentification of SNPs: It becomes impossible to distinguish true evolutionary C>T SNPs from C>T changes caused by bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines [8].

- Inaccurate Methylation Quantification: If a true C>T SNP is present, the site will always appear as unmethylated, skewing methylation results [8].

- Failure in Allele-Specific Analysis: Accurate identification of heterozygous SNPs is a prerequisite for studying allele-specific methylation, a key epigenetic regulatory mechanism [8] [9].

- A: The primary errors are:

Q3: Are there specialized tools to solve this, and how do they work?

- A: Yes, specialized bisulfite SNP callers like Bis-SNP and bsgenova have been developed. They use a strand-specific approach [8] [9]. These tools leverage the fact that in directional bisulfite sequencing protocols, reads originating from the "G-strand" are not affected by C-to-T conversion and can be used to confidently call SNPs, including the problematic C>T type [8]. They employ Bayesian or multinomial models that incorporate base quality scores, bisulfite conversion efficiency, and prior SNP probabilities to make accurate calls [10] [8].

Q4: My lab only has WGBS data, not matched WGS. Can I still call SNPs accurately?

- A: Yes, tools like Bis-SNP and bsgenova are designed specifically for this purpose. Studies have successfully used Bis-SNP to call genotypes from WGBS data alone for sample tagging in large cohorts, confirming its utility even without matched WGS [9]. However, performance is best with adequate coverage (e.g., ~30x) [8].

Q5: Besides the strand problem, what other artifacts plague bisulfite SNP calling?

- A: Library preparation introduces significant artifacts. Both sonication and enzymatic fragmentation can create chimeric reads due to the pairing of partial single strands from similar molecules (PDSM model), leading to false-positive, low-frequency SNVs and indels. These often occur in inverted repeat or palindromic sequences [11].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Bisulfite SNP Calling

Protocol 1: SNP Calling with Bis-SNP

This protocol is based on the method described in [8].

- Read Mapping: Map your bisulfite-treated sequencing reads (single-end or paired-end) to a reference genome using a bisulfite-aware aligner (e.g., Bismark, BSMAP). The output should be a BAM file.

- Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR): Run the Bis-SNP BQSR tool. This is a critical step that recalibrates the base quality scores provided by the sequencer. Unlike standard BQSR, it treats T's at reference C positions as a separate category to avoid misinterpreting bisulfite conversion as errors [8].

- Local Realignment: Perform local realignment around indels to correct mapping artifacts that can lead to false SNP calls.

- SNP Calling with Bis-SNP: Execute the Bis-SNP caller on the processed BAM file. The tool uses a Bayesian model that considers:

- Strand-specific base calls and quality scores.

- Prior information on population SNP frequencies.

- Estimated bisulfite conversion efficiency and site-specific methylation levels [8].

- Output: Bis-SNP generates a standard VCF file with SNP calls and likelihood scores, and can also output methylation levels in BED or WIG format.

Protocol 2: SNP Calling with bsgenova

This protocol utilizes the more recently developed bsgenova tool, which is noted for its accuracy, speed, and robustness against low-quality reads [10].

- Input Preparation: Generate a summary ATCGmap file from your mapped BAM data. This file contains the reference base, CpG context, and counts of A, T, C, G reads mapped to Watson and Crick strands.

- SNP Calling: Run the bsgenova command, which uses a Bayesian multinomial model.

- Model Assumptions: The model accounts for the probability of a base being methylated (dependent on CG context), errors during sample preparation and bisulfite conversion, and mistakes from PCR and sequencing [10].

- Computational Efficiency: bsgenova is optimized with matrix imputation and multi-process parallelization for fast execution [10].

- Output: bsgenova produces both a customized SNV file with detailed posterior probabilities for 10 possible genotypes and a standard VCF file [10].

Performance Comparison of Bisulfite SNP Callers

The following table summarizes key characteristics and performance metrics of major bisulfite-specific SNP callers as evaluated in recent studies.

| Tool | Core Methodology | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Precision | Strengths | Noted Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bis-SNP [8] | Bayesian model within GATK framework | ~96% (at 30x coverage) | High (with default settings) | First major tool; integrates BQSR and realignment; well-documented. | Can be computationally heavy and time-consuming [10]. |

| bsgenova [10] | Bayesian multinomial model with matrix optimization | High (superior for chrX) | High (superior with low-quality reads) | Fast; low memory/disk usage; robust to low-quality data. | Relatively newer tool (2024). |

| BS-SNPer [10] | Heuristic and probabilistic model | Lower than Bis-SNP/bsgenova | High (but less sensitive) | Fast processing speed. | Lower sensitivity compared to other methods [10]. |

| MethylExtract [10] | Simple probabilistic model | High | Lower than Bis-SNP/bsgenova | Sensitive for SNP detection. | Less specific, leading to more false positives [10]. |

| cgmaptools [10] | Not specified | High | Lower than Bis-SNP/bsgenova | Sensitive for SNP detection. | Not robust against contaminative or low-quality reads [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | The key chemical that converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil, while leaving methylated cytosine unchanged. This is the foundation of the entire protocol [8] [5]. |

| Directional Bisulfite-Seq Library Prep Kit | A commercial kit that ensures sequencing reads can be traced to their original strand (C-strand or G-strand). This strand-specificity is exploited by tools like Bis-SNP to resolve the complementarity problem [8]. |

| Bisulfite-Aware Aligner (e.g., Bismark, BSMAP) | Specialized software that accurately maps sequencing reads back to the reference genome by simulating the bisulfite conversion process in silico. Standard aligners fail at this task [8]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used during library amplification to minimize the introduction of novel errors (false positive SNPs) during PCR [11]. |

| Artifact Blacklist (BED file) | A bioinformatic list of genomic regions prone to library preparation artifacts (e.g., inverted repeats, palindromes). Tools like ArtifactsFinder can generate these to filter out false positives [11]. |

Workflow Diagrams for Troubleshooting

- Troubleshooting SNP Calling Workflow

- Logic of Strand Complementarity Problem

FAQ: Resolving Bisulfite Sequencing Ambiguity

Q1: Why is it so challenging to distinguish a true C>T SNP from a bisulfite-converted cytosine? The core problem stems from the chemistry of the bisulfite conversion process itself. In bisulfite-treated DNA, unmethylated cytosines are converted to uracils, which are then read as thymines (T) during sequencing. A true C>T single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) will also appear as a T in the sequencing data. Therefore, from the sequencing output alone, a T can represent either a genuine genetic variant or a successful conversion of an unmethylated cytosine, making the two events indistinguishable from a single read [12] [13].

Q2: What is the primary method to overcome this misidentification? The most robust solution is the use of directional bisulfite sequencing protocols. These protocols preserve strand-specificity, which is the key to resolving the ambiguity [12].

- On one DNA strand, a C->T change can represent either an unmethylated cytosine or a SNP.

- On the complementary strand, this same event will result in a G->A change if it was due to bisulfite conversion.

- A true C->T SNP, however, will have a complementary G->A change on the opposite strand.

By analyzing both strands, you can differentiate the patterns: a bisulfite conversion artifact creates an asymmetric C->T and G->A pattern across strands, while a true SNP creates a symmetric one [12].

Q3: Can bioinformatic tools alone solve this problem, and how do they differ? Yes, several bioinformatic tools are designed for SNP calling from bisulfite-converted data, but they perform differently. The choice of tool involves a trade-off between sensitivity (finding all true SNPs) and precision (avoiding false positives) [12].

- Some tools, like Bis-SNP, are optimized for higher precision.

- Others, like Biscuit, are optimized for higher sensitivity.

- Most tools attempt to strike a balance between the two.

Furthermore, some modern methylation callers, like MethylDackel, incorporate a specific feature to filter out SNPs. They use overlapping paired-end sequencing data to check the base on the opposite strand; if a C->T change is not accompanied by a G on the opposite strand, it is more likely to be a SNP and can be filtered out of the methylation analysis [6].

Q4: How does the presence of a SNP near a CpG site affect methylation measurement? The presence of a SNP within or very near a CpG site (often called a "probe-SNP") can severely bias the measurement of methylation levels, particularly for array-based technologies like the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC array. The genetic variant can interfere with the probe's ability to bind to its target sequence, leading to a spurious methylation reading that actually reflects genetic variation rather than true epigenetic status [14]. Bisulfite sequencing methods are less susceptible to this specific issue, but the underlying C/T polymorphism still needs to be correctly identified to accurately calculate methylation proportions [6] [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Unexpectedly High Number of C>T Variants Problem: Your variant calling from bisulfite sequencing data reveals an overabundance of C>T SNPs. Solution:

- Verification: Confirm that your library preparation was performed with a directional bisulfite sequencing protocol [12].

- Bioinformatic Re-analysis: Re-run your SNP calling using a tool specifically designed for bisulfite-converted data. Cross-reference your list of C>T SNPs with a known SNP database for your species, if available.

- Validation: Consider validating key SNPs using an independent, non-bisulfite method (e.g., standard PCR and Sanger sequencing) on the original DNA [14].

Scenario 2: Inconsistent Methylation Calls at a Specific Locus Problem: Methylation levels at a particular CpG site are highly variable between samples or do not match validated data. Solution:

- Check for Underlying Variation: First, inspect the raw sequencing reads at that locus in a genome browser to check for the presence of a nearby SNP that might be interfering with the methylation call [14].

- Apply a SNP Filter: Use a bioinformatic tool, like MethylDackel, that can identify and filter out positions likely to be SNPs based on paired-end read information [6].

- Filter Your Dataset: For array-based data, rigorously filter out CpG sites that are known to contain or are adjacent to common SNPs, using a comprehensive reference like the 1000 Genomes Project [14].

Performance Comparison of SNP Callers for Bisulfite Data

The table below summarizes the performance of different tools as evaluated in a study on a non-model organism (great tit). The baseline for comparison was SNPs called from whole-genome resequencing data [12].

| Tool | Key Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Bis-SNP | Optimizes for precision, resulting in fewer false positive SNPs. |

| Biscuit | Optimizes for sensitivity, resulting in fewer false negative SNPs. |

| Other Tools | Provides a compromise between sensitivity and precision. |

Comparison of Bisulfite Sequencing Methods

The choice between whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) also influences the context and potential challenges of SNP misidentification.

| Method | Coverage | Advantages | Challenges for SNP Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Genome-wide, all CpG sites | Comprehensive; no ascertainment bias [6]. | Lower read depth can reduce accuracy of both SNP and methylation calls; more expensive, limiting sample size [6]. |

| RRBS | Targets CpG-rich regions (e.g., CpG islands) | Cost-effective; higher read depth at covered sites; allows for larger sample sizes [6]. | Only interrogates a fraction of the genome (~10%); may miss important SNPs in non-CpG-rich regions [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating SNP-CpG Associations Using Methyl-Seq

This protocol is adapted from a study that used Methyl-Seq to validate findings from methylation arrays, which are prone to probe-SNP bias [14].

1. Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA.

- Perform bisulfite conversion using a kit designed for sequencing applications (e.g., Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation Lightning Kit).

- Prepare sequencing libraries, for example, using the Agilent SureSelectXT Methyl-Seq system for targeted enrichment, or standard WGBS libraries.

- Sequence on an Illumina platform to a sufficient depth (e.g., >10x coverage per CpG site is a common minimum threshold) [14].

2. Bioinformatic Processing and Read Alignment:

- Perform quality control on raw sequence data using FastQC.

- Align the bisulfite-treated reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using a specialized aligner. The study utilized Bismark (v0.22.1) [14], but BWA-meth is a noted alternative with higher mapping efficiency in some cases [6].

- Remove duplicate reads using the

deduplicate_bismarkcommand.

3. Methylation Calling and Association Analysis:

- Extract methylation information for each CpG site, ensuring a minimum coverage filter (e.g., >10x) to guarantee data quality [14].

- For the specific CpG sites of interest (e.g., those previously identified by an array), conduct association analyses between the methylation levels (from Methyl-Seq) and the genotype data to replicate the original SNP-CpG findings.

4. Validation and Replication Rate Calculation:

- A significant association from the Methyl-Seq data at a locus previously identified by the array is considered a successful replication.

- Calculate the overall replication rate to confirm the robustness of the initial findings, as done in the referenced study, which showed a 71.6% replication rate for one model [14].

Visualizing the Core Problem and Its Solution

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental challenge of distinguishing a C>T SNP from bisulfite conversion and how strand-specific sequencing resolves it.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

This table lists key materials and tools used in the experiments cited in this guide.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Agilent SureSelectXT Methyl-Seq | A target enrichment system used to prepare libraries for bisulfite sequencing validation studies [14]. |

| Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation Lightning Kit | A commercial kit for rapid and efficient bisulfite conversion of DNA [12]. |

| Bismark | A widely used aligner and methylation caller for bisulfite sequencing data. It performs in-silico conversion of the reads and reference genome for accurate alignment [6] [14]. |

| BWA-meth / MethylDackel | An alternative pipeline for bisulfite data analysis. BWA-meth aligns reads, often with higher efficiency, and MethylDackel is used to extract methylation calls, with built-in SNP filtering capabilities [6]. |

| PolyMarker | A primer design tool for developing locus-specific assays in polyploid species, helping to avoid co-amplification from highly similar genomic regions [15]. |

| FDSTools | Software used for the analysis of forensic STRs, which has been adapted to name STRs in bisulfite-converted DNA and perform allele-linked DNA methylation analysis [5]. |

Impact of Directional vs. Non-Directional Bisulfite Sequencing Protocols

Bisulfite sequencing is a fundamental technique in epigenetics for detecting DNA methylation at single-nucleotide resolution. The critical distinction between directional and non-directional library preparation protocols significantly impacts data quality, analytical approaches, and the ability to discriminate true single nucleotide polymorphisms from bisulfite-induced artifacts. This technical support center guide addresses key challenges researchers face when selecting and implementing these protocols, particularly within studies investigating SNP variation and bisulfite conversion artifacts. Understanding these methodological differences is essential for generating reliable data in both genetic and epigenetic analyses [12] [16].

Understanding the Core Protocol Differences

FAQ: What is the fundamental difference between directional and non-directional bisulfite sequencing?

Answer: The fundamental difference lies in strand specificity during library preparation. Directional protocols preserve information about the original DNA strand, while non-directional protocols do not.

In directional protocols, different adapters are ligated to the 5' and 3' ends of the DNA fragments before sequencing. This ensures that the sequencing read can be unambiguously traced back to its original genomic strand. The sequencing primer binds only to one specific adapter sequence, producing reads that consistently represent the original 5'-to-3' orientation of the DNA fragment [17].

In non-directional protocols, identical adapters are ligated to both ends of DNA fragments. The sequencing primer can bind to either end, meaning the resulting reads could represent either the original sequence or its reverse complement, with no built-in mechanism to distinguish between them [17].

FAQ: How does protocol directionality affect SNP calling and artifact identification?

Answer: Directional protocols provide a critical advantage for distinguishing true C>T SNPs from bisulfite-converted cytosines through strand-specific resolution.

In directional protocols, reads originating from the "G-strand" provide unambiguous evidence for C>T SNPs because these positions appear as G>A polymorphisms that are unaffected by bisulfite conversion. This strand-specific information enables specialized SNP callers to accurately differentiate genetic variants from epigenetic signals [16].

Non-directional protocols lose this strand information, making it significantly more challenging to discriminate true C>T SNPs from unmethylated cytosines that have undergone bisulfite conversion. This ambiguity can lead to both false positive and false negative SNP calls, complicating downstream genetic and epigenetic analyses [12] [16].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Directional vs. Non-Directional Bisulfite Sequencing Protocols

| Feature | Directional Protocol | Non-Directional Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Strand Information | Preserved | Lost |

| Adapter Design | Different adapters for 5' and 3' ends | Identical adapters for both ends |

| SNP Calling Accuracy | Higher, especially for C>T SNPs | Lower, ambiguity in C>T discrimination |

| Data Complexity | Higher initial processing | Simpler initial processing |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Requires specialized strand-aware tools | Compatible with broader tools |

| Methylation Quantification | More accurate at C>T SNP sites | Potential artifacts at C>T SNP sites |

Technical Challenges and Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Artifacts and Resolution Strategies

Problem: Incomplete bisulfite conversion leading to false positive methylation calls.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Pre-conversion DNA quality: Ensure complete protein removal from DNA samples prior to bisulfite treatment, as residual proteins can protect cytosines from conversion [18] [19].

- Conversion efficiency monitoring: Include completely unmethylated controls (e.g., lambda phage DNA) to calculate empirical conversion rates. Conversion efficiency should typically exceed 99% [18] [20].

- Protocol optimization: Follow standardized bisulfite treatment protocols with appropriate incubation times, temperature, and buffer conditions to ensure complete conversion [18].

Problem: PCR amplification biases affecting methylation quantification.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Polymerase selection: Use high-fidelity "hot start" polymerases to reduce non-specific amplification, which is particularly problematic with bisulfite-treated DNA due to its reduced sequence complexity [20].

- Cycle optimization: Minimize PCR cycle numbers (while maintaining sufficient library yield) to reduce over-amplification of specific fragments [21].

- Duplication rate assessment: Monitor PCR duplication rates in sequencing data as a quality control metric [12].

Workflow Visualization: Directional Bisulfite Sequencing for SNP Discrimination

The following diagram illustrates how directional bisulfite sequencing protocols enable strand-specific discrimination between true C>T SNPs and bisulfite conversion artifacts:

Diagram: Strand-specific resolution in directional bisulfite sequencing enables simultaneous methylation quantification and accurate SNP calling.

Performance Assessment and Tool Selection

Quantitative Performance Metrics for SNP Callers

Table: Performance Comparison of SNP Calling Tools for Bisulfite Sequencing Data

| Tool | Optimal Use Case | Sensitivity | Precision | Key Strength | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bis-SNP | Maximizing precision | Moderate | High | Best precision for C>T SNPs [12] | GATK-based [16] |

| Biscuit | Maximizing sensitivity | High | Moderate | Best sensitivity for variant detection [12] | Standalone suite |

| BS-SNPer | Fast processing | Moderate | High | Speed and efficiency [10] | C implementation |

| Bsgenova | Balanced performance | High | High | Accuracy for chromosome X, robust to low-quality reads [10] | Bayesian multinomial model |

| MethylExtract | Sensitivity-focused | High | Moderate | High sensitivity for variant detection [10] | Perl-based |

FAQ: How do I choose the appropriate SNP caller for my bisulfite sequencing data?

Answer: The choice depends on your research priorities and data characteristics:

- For maximizing precision (minimizing false positives): Select Bis-SNP, which demonstrates the highest precision in benchmark studies, particularly for challenging C>T SNPs [12] [9].

- For maximizing sensitivity (minimizing false negatives): Choose Biscuit or Bsgenova, which show superior sensitivity for detecting true variants, with Bsgenova performing particularly well with low-quality data and on chromosome X [12] [10].

- For balanced performance: Bsgenova provides an optimal balance between sensitivity and precision, along with superior computational efficiency [10].

- For specific challenging scenarios: Consider Bsgenova for chromosome X analysis or when working with data containing low-quality reads, as it demonstrates particularly robust performance under these conditions [10].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Bisulfite Sequencing Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Purity critical for conversion efficiency; fresh preparation recommended [18] |

| DNA Restoration Reagents | Repair of bisulfite-induced DNA fragmentation | Essential for low-input samples; reduces bias in library representation [21] |

| Strand-Specific Adapters | Directional library preparation | Different 5' and 3' adapters mandatory for directional protocols [17] |

| Methylated Adapters | Prevention of adapter conversion | Critical for pre-bisulfite adapter ligation protocols [21] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | PCR amplification of converted DNA | Reduces errors in AT-rich bisulfite-converted templates [20] |

| Unmethylated Control DNA | Conversion efficiency monitoring | Lambda phage or synthetic unmethylated DNA for quality control [20] |

| Methylated Control DNA | Bisulfite conversion specificity verification | Confirms methylated cytosines remain protected [20] |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Computational Strategies for Non-Directional Data

For researchers working with existing non-directional datasets, computational approaches can partially mitigate the limitations:

Base Quality Score Manipulation: The "double-masking" procedure manipulates base quality scores for nucleotides potentially affected by bisulfite conversion, assigning them zero quality. This prevents conventional Bayesian variant callers from considering these positions as evidence for SNPs, effectively introducing strand specificity through quality control [22].

Reference-Based Reconstruction: When paired whole-genome sequencing data is available, SNPs identified from conventional sequencing can be used to validate and correct SNP calls from bisulfite sequencing data, though this requires additional sequencing resources [9].

Protocol Selection Guidelines for Specific Research Goals

- For allele-specific methylation studies: Directional protocols are essential, as they enable unambiguous haplotype phasing through strand-specific SNP identification [16].

- For large-scale epigenome-wide association studies: Consider non-directional protocols only when coupled with separate whole-genome sequencing for genotype information, as the reduced complexity may lower costs for high-throughput applications [9].

- For novel SNP discovery in conjunction with methylation analysis: Directional protocols are strongly recommended, as they provide the most reliable discrimination between true genetic variants and epigenetic modifications [12] [16].

- For clinical diagnostics or biomarker validation: Directional protocols provide the highest accuracy for simultaneous genetic and epigenetic profiling, reducing false positive rates in variant calling [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do genetic variants in probe sequences lead to spurious methylation results? Genetic variants (SNPs) within the 50-base pair probe sequence of DNA methylation microarrays can alter the probe's hybridization efficiency. This is particularly problematic in admixed populations, as a probe SNP that is common in one ancestral population but not another can create a false association between local genetic ancestry and DNA methylation level. This technical artifact can be misinterpreted as biological signal, such as an ancestry-specific meQTL [23].

2. What is the fundamental difference between bisulfite sequencing and enzymatic methods regarding DNA damage? Bisulfite conversion relies on harsh chemical conditions (high temperature and low pH) that cause DNA fragmentation and depyrimidination, leading to significant DNA degradation and loss. This results in biased genome coverage, particularly in high GC-content regions. In contrast, enzymatic conversion methods (like EM-seq) use milder enzyme-based reactions that preserve DNA integrity, leading to more uniform genome coverage and higher library complexity, especially from low-input samples [24].

3. Why is C-to-T SNP calling challenging from bisulfite sequencing data, and how can this be overcome? Standard variant callers assume complementary base pairs across DNA strands, an assumption violated by bisulfite conversion, which converts unmethylated C to T (read as T) on one strand but leaves the complementary G unchanged. This makes it difficult to distinguish a true C-to-T polymorphism from a bisulfite-induced conversion. Specialized computational strategies, such as "double-masking," manipulate base quality scores to leverage this strand-specific information, enabling the use of conventional Bayesian variant callers with bisulfite data [22].

4. How can I improve the accuracy of detecting allele-specific methylation (ASM)? The accuracy of ASM detection is highly dependent on the correct phasing of sequencing reads to their parental haplotype. Using a "trio-binning" approach, where the genomes of an individual's parents are also sequenced, significantly improves phasing accuracy and haplotype block continuity (N50) compared to computational phasing alone. Increasing sequencing coverage beyond 30x without parental information provides diminishing returns, whereas trio binning offers a substantial improvement in correctly assigning methylation signals to alleles [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete Bisulfite Conversion Leading to False Positives

Issue: Unconverted cytosines are misinterpreted as methylated cytosines, leading to overestimation of methylation levels [18].

Solution:

- Ensure DNA is fully denatured: Protein contaminants can cause DNA to reanneal during conversion, protecting cytosines from conversion. Use high-quality, protein-free DNA [18] [26].

- Follow a standardized protocol: Use a reliable, detailed protocol for bisulfite treatment. A sample is provided below [26].

- Denature DNA: Mix DNA with a fresh denaturation buffer (e.g., containing NaOH) and incubate at 98°C for 5-20 minutes.

- Prepare Saturated Bisulfite Solution: Freshly prepare a saturated sodium metabisulfite solution (pH 5.0) containing a reducing agent like hydroquinone to prevent oxidation.

- Incubate: Combine denatured DNA with the bisulfite solution, overlay with mineral oil to prevent evaporation, and incubate in the dark at 50°C for 12-16 hours.

- Desalt and Desulfonate: Purify the converted DNA using a minicolumn-based kit. Subsequently, treat with NaOH to desulfonate the uracil-sulfonate adducts to uracil.

- Precipitate and Resuspend: Precipitate the DNA with ethanol/ammonium acetate, wash, and resuspend in TE buffer or water [26] [27].

- Include controls: Always run non-methylated and fully methylated control DNA samples alongside experimental samples to verify conversion efficiency [18].

Problem: Spurious meQTLs Due to Probe SNPs on Microarrays

Issue: Common SNPs within the probe sequence of methylation array platforms cause spurious meQTL discoveries that are confounded with local genetic ancestry [23] [28].

Solution:

- Rigorous probe filtering: Cross-reference all CpG probe sequences with a comprehensive database of genetic variants (e.g., from the 1000 Genomes Project) to identify probes containing SNPs.

- Use specialized tools: Employ software like

probeSNPfferto systematically flag and remove problematic probes from your analysis dataset [23]. - Analyze raw fluorescence signals: Tools like

UMtoolscan analyze raw fluorescence intensity signals (U and M) from the microarray to identify probe failure patterns indicative of underlying genetic artifacts, which are often masked in the final beta-value output [28].

Problem: DNA Degradation and Biased Coverage in Bisulfite Sequencing

Issue: The harsh conditions of bisulfite treatment fragment DNA, leading to substantial sample loss, biased genome coverage (especially against high-GC regions), and higher sequencing costs to achieve sufficient depth [24].

Solution:

- Switch to enzymatic conversion: Use Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) as an alternative. EM-seq employs enzymatic reactions to distinguish modified cytosines without damaging the DNA.

- Validate with published data: As shown in the table below, multiple independent studies have demonstrated that EM-seq outperforms WGBS in key metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of WGBS and EM-seq

| Metric | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Integrity | Severely degraded due to high temp/low pH | Preserved; minimal damage | [24] |

| Library Complexity | Lower; high duplicate rates | Higher; lower duplicate rates | [24] |

| CpG Detection (Low Input, 1x coverage) | ~36 million CpGs | ~54 million CpGs | [24] |

| CpG Detection (Low Input, 8x coverage) | ~1.6 million CpGs | ~11 million CpGs | [24] |

| GC Bias | Significant bias; under-representation of GC-rich regions | More uniform GC coverage | [24] |

| Protocol Recommendation | - | Recommended for whole-genome DNA methylation sequencing | [24] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Bisulfite Conversion of DNA

This protocol is adapted from established laboratory methods for robust bisulfite conversion [26].

Materials:

- DNA sample (up to 2 µg genomic DNA)

- Glycogen (as carrier for low-concentration samples)

- 3 N NaOH (freshly prepared)

- 0.5 M Na₂EDTA, pH 8.0

- 100 mM hydroquinone (freshly prepared, light-sensitive)

- Sodium bisulfite/metabisulfite mixture

- Minicolumn-based DNA purification kit (e.g., Zymo Research)

- TE buffer

Procedure:

- Denature DNA: Add a freshly prepared denaturation buffer (containing NaOH and EDTA) to your DNA sample. Incubate at 98°C for 5-20 minutes to ensure complete denaturation into single strands.

- Prepare Bisulfite Solution: In a tube with a stir bar, mix 7 ml of degassed water, 100 µl of 100 mM hydroquinone, and one 5g vial of sodium metabisulfite. While stirring gently, add 1 ml of 3 N NaOH and adjust the pH to 5.0. Pre-heat this saturated solution to 50°C.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Add the pre-heated bisulfite solution to the denatured DNA. Overlay with mineral oil and incubate in the dark at 50°C for 12-16 hours.

- Purification and Desulfonation: After incubation, remove the mineral oil. Purify the DNA using the minicolumn-based kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The eluted DNA is then treated with NaOH (e.g., 37°C for 15 minutes) to complete the desulfonation reaction.

- Final Precipitation: Precipitate the DNA by adding ammonium acetate, ethanol, and isopropanol. Wash the pellet with 70% ethanol, dry, and resuspend in TE buffer or water. The converted DNA is now ready for PCR amplification [26] [27].

Workflow: Resolving Genetic Artifacts in Methylation Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing genetic artifacts in DNA methylation studies.

Diagram 1: A workflow for diagnosing and resolving genetic artifacts in DNA methylation data, with separate paths for microarray and sequencing-based platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Discriminating SNP Variation from Bisulfite Artifacts

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical Reagent | Selectively deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil, enabling methylation status detection [26] [27]. |

| EM-seq Kit | Library Prep Kit | Enzymatically identifies 5mC and 5hmC without DNA damage, overcoming key limitations of bisulfite conversion [24]. |

| probeSNPffer | Software Tool | Cross-references CpG probe coordinates with genetic variant databases to flag probes prone to hybridization artifacts [23]. |

| UMtools | Software Tool (R package) | Analyzes raw microarray fluorescence signals to identify and qualify genetic artifacts and probe failures [28]. |

| Revelio | Software Tool | Implements "double-masking" pre-processing on bisulfite sequencing alignments to enable accurate SNP calling with conventional tools [22]. |

| Trio-Binning Approach | Methodology | Uses parental genome sequences to achieve superior phasing accuracy for allele-specific methylation analysis from long-read data [25]. |

Methodological Solutions: Computational and Experimental Strategies for Accurate SNP Calling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our bisulfite sequencing analysis is yielding unexpectedly low mapping efficiency. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Low mapping efficiency in bisulfite sequencing is often related to the bioinformatic tools and parameters used for aligning the converted sequences. The core challenge is that bisulfite treatment reduces genome complexity, making alignment difficult.

- Primary Cause: The in silico conversion strategy used by aligners significantly impacts performance. Tools like Bismark, which converts both the read and reference genome, can be computationally intensive and may result in lower mapping rates [6].

- Solution: Consider alternative mapping tools. Benchmarking studies indicate that BWA-meth can provide a 45% higher mapping efficiency compared to Bismark by using a different alignment strategy [6]. Furthermore, using paired-end sequencing is highly recommended, as it provides more information to accurately map reads and helps distinguish true unmethylated cytosines from single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [6].

Q2: How can I reliably distinguish a true single-nucleotide variant (SNV) from an artifact caused by incomplete bisulfite conversion?

Discriminating between a C>T SNV and an unconverted, methylated cytosine is a critical challenge. A robust solution leverages the inherent symmetry of CpG sites.

- Primary Cause: In standard bisulfite sequencing, a C>T change on the forward strand could either be a true variant or an unconverted methylated cytosine. Without additional information, these are indistinguishable and can lead to false positives in either variant or methylation calls [29].

- Solution: The most reliable method is to examine the complementary strand. For a genuinely methylated CpG site, the complementary base to the cytosine is a guanine (G). In contrast, for a true C>T SNV, the complementary base on the opposite strand would be an adenosine (A) [29]. Bioinformatics tools like MethylDackel use this logic to filter out polymorphic sites and prevent them from biasing methylation metrics [6]. The Illumina 5-base solution and its DRAGEN analysis software also fundamentally rely on this principle for dual-omic calling [29].

Q3: What is the impact of read depth on the accuracy of methylation calls, and how do I choose an appropriate depth?

Read depth is a major determinant of accuracy in DNA methylation studies, as methylation level at a site is a quantitative metric (proportion of reads showing methylation).

- Primary Cause: At low read depths, the estimated methylation level for a CpG site is statistically unstable. A few reads can drastically skew the perceived methylation proportion, especially for sites with intermediate methylation [6].

- Solution: The required depth depends on your biological question and the heterogeneity of your sample. There is no universal value, but a best practice is to "sequence a few initial individuals deeply to identify the amount of genomic coverage necessary for mean methylation estimates to plateau" [6]. Depth filters also have a large impact on the number of CpG sites recovered across multiple individuals, which is crucial for cohort studies [6].

Q4: We are studying genetically diverse natural populations. How do genetic variants (SNPs/indels) interfere with methylation analysis, and how can we mitigate this?

Genetic variation is a major source of artifact in methylation studies, as sequencing probes or reads may not map correctly to a divergent genome.

- Primary Cause: Underlying SNPs or indels can prevent the hybridization of sequencing reads or microarray probes, leading to erroneous methylation calls or complete probe failure. This is a well-documented issue for both sequencing-based methods and microarray platforms like the Illumina Infinium arrays [28].

- Solution:

- For sequencing data: Use tools that explicitly account for polymorphisms. MethylDackel, for example, can use overlaps from paired-end data to discriminate SNPs from unmethylated cytosines and exclude them [6].

- For microarray data: Move beyond static probe exclusion lists. Develop data-driven strategies to identify artifacts from raw fluorescence intensity signals (U/M plots), as implemented in the UMtools R package, which can expose genetic artifacts not accounted for in standard databases [28].

- General Practice: Paired-end sequencing is again highly recommended for population studies to help filter these polymorphic sites [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Methylation Profiles Between Technical Replicates

Possible Causes and Diagnostic Steps:

Incomplete Bisulfite Conversion:

- Diagnosis: Check conversion rates using spike-in controls (e.g., unmethylated lambda phage DNA). A conversion efficiency of >99% is typically expected.

- Solution: Optimize the bisulfite conversion protocol by strictly controlling reaction time, temperature, and pH. Use fresh bisulfite reagent.

Low Sequencing Depth:

- Diagnosis: Calculate the average read depth per CpG site in your aligned data. High variance in methylation calls at low-coverage sites indicates a depth issue.

- Solution: Increase sequencing depth. For WGBS, aim for high coverage (e.g., 30x); for RRBS, ensure sufficient depth to robustly call methylation levels at your target sites.

Bioinformatic Pipeline Variability:

- Diagnosis: Re-run raw data through your pipeline with identical settings and check for consistency. Compare outputs from different methylation callers (e.g., Bismark vs. a BWA-meth/MethylDackel combo).

- Solution: Document and version-control all software and parameters. For critical analyses, consider using a containerized pipeline (e.g., Docker, Singularity) for perfect reproducibility.

Problem: Suspected Genetic Artifacts in Methylation Data

Step-by-Step Investigation:

- Step 1: Annotate with Known Genetic Variants. Cross-reference your CpG sites of interest with public (e.g., dbSNP) or population-specific genotype databases to identify co-located variants [28].

- Step 2: Interrogate Raw Data Signals. If using microarray data, use tools like UMtools to visualize the raw fluorescence intensities (U/M plots). Genetic artifacts often produce distinct cluster patterns that are obscured in the final beta-value calculation [28].

- Step 3: Employ SNP-Aware Bioinformatics Tools. For sequencing data, ensure your alignment and methylation calling tools are designed to handle polymorphisms. Bismark can be run in alignment modes that are more permissive of mismatches, and MethylDackel actively filters SNPs [6].

- Step 4: Validate Findings. If a specific locus is critical, consider validating the methylation state and genotype using an orthogonal method, such as pyrosequencing.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: RRBS for Ecological Epigenetics

This protocol is adapted for genetically variable natural populations [6].

Library Preparation:

- DNA Digestion: Digest genomic DNA (100-500 ng) with the methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme MspI (cut site: CCGG) to enrich for CpG-rich genomic regions.

- Size Selection: Clean up the digested DNA and perform size selection (e.g., using gel electrophoresis or solid-phase reversible immobilization beads) to isolate fragments in the 150-400 bp range.

- End-Repair and Adenylation: Repair fragment ends and add a single 'A' base to the 3' ends to facilitate adapter ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate methylated sequencing adapters to the fragments.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat the adapter-ligated DNA with sodium bisulfite. This critical step converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, which will be read as thymines during sequencing.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the converted libraries using PCR. Use a polymerase capable of amplifying uracil-containing templates. Index sequences are added during this step for multiplexing.

Sequencing:

- Utilize paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform. Paired-end reads are crucial for population studies as they aid in filtering SNPs [6].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess read quality.

- Read Trimming & Adapter Removal: Use Trim Galore! or Cutadapt, which can handle bisulfite-converted reads.

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome using a bisulfite-aware aligner. The choice of tool is critical:

- Methylation Calling: Extract methylation counts for each CpG site. Bismark does this internally. If using BWA-meth, use MethylDackel for this step [6].

- SNP Filtering: Actively filter out CpG sites that overlap with known or detected SNPs to prevent artifacts [6] [28].

- Differential Analysis: Use tools like methylKit or DMReport in R to identify statistically significant differences in methylation between sample groups.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Comparison of Bisulfite Sequencing Analysis Tools

Table 1: Performance and characteristics of popular bioinformatics tools for bisulfite sequencing data.

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Algorithm/Strategy | Reported Performance | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bismark [6] | Read mapping & methylation extraction | In silico conversion of both reads & reference genome (using Bowtie2) | Standard tool; lower mapping efficiency vs. BWA-meth [6] | User-friendly, all-in-one solution. Can be computationally intensive. |

| BWA-meth [6] | Read mapping | In silico conversion of reference genome only (using BWA mem) | 50% higher mapping efficiency than Bismark [6] | Faster than Bismark. Requires MethylDackel for methylation calling. |

| MethylDackel [6] | Methylation extraction | Works with BWA-meth alignments; can filter SNPs using paired-end info | Effective at discriminating SNPs from unconverted Cs [6] | Essential companion for BWA-meth. Improves call accuracy in diverse populations. |

| BWA mem [6] | Read mapping (standard) | Standard DNA read mapping, not bisulfite-aware | Systematically discards unmethylated cytosines [6] | Not recommended for bisulfite data without modification. |

| Illumina DRAGEN [29] | Secondary analysis (5-base) | Methylation-aware alignment & variant calling for novel chemistry | Enables simultaneous variant and methylation calling [29] | Tied to Illumina's 5-base solution and DRAGEN platform. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and tools for SNP and bisulfite-conversion artifact research.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical agent that deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil. | The foundational reagent for most standard bisulfite sequencing protocols (WGBS, RRBS) [6] [28]. |

| MspI Restriction Enzyme | Methylation-insensitive enzyme that cuts at CCGG sites. | Used in RRBS library prep to selectively target and enrich for CpG-rich regions of the genome [6]. |

| Unmethylated Lambda Phage DNA | A control DNA with known, near-zero methylation. | Spike-in control to empirically measure and monitor the efficiency of bisulfite conversion in each reaction [28]. |

| UMtools R Package [28] | Software for analyzing raw fluorescence intensities from microarrays. | Identifies and diagnoses genetic artifacts in Illumina Infinium Methylation BeadChip data that are missed by standard analysis [28]. |

| Illumina 5-Base Conversion Enzyme [29] | A novel engineered enzyme that directly converts methylated cytosine to thymine. | Core of the "5-base solution"; enables simultaneous high-accuracy genetic variant and methylation calling from a single workflow [29]. |

| Paired-End Sequencing Adapters | Oligonucleotides ligated to DNA fragments for sequencing. | Mandatory for population studies. Provides the read-pair information needed to filter SNPs and improve mapping accuracy [6]. |

Logical Workflow for Tool Selection

The following diagram outlines a decision process for selecting the appropriate bioinformatic tools based on your research goals and sample type:

Core Concepts: FAQs on Strand-Specificity and Bisulfite Conversion

FAQ 1: Why is distinguishing true C>T SNPs from bisulfite conversion artifacts a major challenge?

After bisulfite treatment, all unmethylated cytosines (C) are converted to uracils (U), which are then read as thymines (T) during sequencing [30] [31]. Consequently, a T base in the sequencing data could represent either a genuine single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or a successful conversion of an unmethylated C. Without special methods, it is impossible to differentiate between these two biologically distinct scenarios, leading to potential false positives in SNP calling [32].

FAQ 2: How does exploiting G-strand reads provide a solution?

Bisulfite conversion affects the two DNA strands differently. On the forward strand, unmethylated Cs are converted to Ts. On the reverse-complement strand, the guanines (G) opposite these unconverted Cs remain unchanged, but the Gs opposite converted bases become adenines (A) [30]. By performing strand-specific analysis, you can cross-verify a potential C>T SNP call. A true C>T SNP on the forward strand will manifest as a complementary G>A change on the reverse strand. If this specific signature is not present, the observed T is likely a bisulfite conversion artifact [32].

FAQ 3: What are the critical wet-lab steps to ensure successful strand-specific analysis?

The foundation for accurate analysis is laid during sample preparation. Key steps include [32] [3]:

- Complete Bisulfite Conversion: Achieve a conversion rate of >99.8% to minimize false negatives and ensure consistent sequence changes [32].

- Specialized Primer Design: Design four primers for each region of interest—two for each strand. Primers must be complementary to the bisulfite-converted sequence, be sufficiently long (24-32 nts) to bind specifically despite the reduced sequence complexity, and should not have mixed bases at their 3' end [32] [3].

- Appropriate Polymerase Selection: Use a polymerase that can efficiently read through uracil residues in the template DNA, such as a hot-start Taq polymerase. Proof-reading polymerases are not recommended [3].

FAQ 4: Which bioinformatics tools are designed for this type of analysis?

Standard short-read aligners treat C>T changes as mismatches, leading to poor alignment. Specialized bisulfite-aware aligners are required. The following table compares common strategies and tools:

Table 1: Comparison of Bisulfite Sequencing Read Alignment Strategies

| Alignment Strategy | Key Principle | Example Tool(s) | Pros and Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Letter Alignment | Converts all Cs to Ts in both reads and reference to eliminate mismatches. | Bismark [30], bwa-meth [30] | Simple approach. Loses distinction between Cs and Ts, potentially reducing unique alignments [30]. |

| Wildcard Alignment | Replaces Cs in the reference with a wildcard (Y) that can match either C or T in reads. | BSMAP [30] | No information loss. Biased towards better alignment of reads from hypermethylated regions, leading to overestimation of methylation [30]. |

| Context-Aware Alignment | Directly integrates BS-specific alterations, using multiple genome indexes based on methylation context (e.g., CpG islands). | ARYANA-BS [30] | Achieves state-of-the-art accuracy by considering genomic context; outperforms other methods in robustness [30]. |

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Low mapping rates or high multi-mapping reads after bisulfite alignment.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete bisulfite conversion or poor-quality input DNA, leading to inconsistent C>T patterns and non-specific primer binding [32] [3].

- Solutions:

- Verify bisulfite conversion efficiency by spiking in an unmethylated control DNA (e.g., λ-phage) and ensure conversion rates are >99% [31].

- Check DNA purity before conversion. Particulate matter can inhibit the reaction. Centrifuge samples and use clear supernatant [3].

- Re-evaluate primer design. Ensure primers are specific to the converted sequence and avoid regions with high sequence complexity loss [32].

Issue 2: Inconsistent or failed PCR amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA.

- Potential Cause: Use of a polymerase that is inefficient at amplifying uracil-containing templates; primers designed for the wrong strand or with suboptimal length [32] [3].

- Solutions:

- Use a hot-start Taq polymerase (e.g., Platinum Taq) that is validated for bisulfite-converted DNA. Avoid proof-reading enzymes [3].

- Keep amplicon size relatively small (~200 bp) to accommodate DNA fragmentation caused by the harsh bisulfite treatment [3].

- Use specialized freeware (e.g., Zymo Research's Free Bisulfite Primer Design Tool) to design and check your primers [5].

Issue 3: Persistent background noise and false positives in SNP calling.

- Potential Cause: Sequencing errors and PCR artifacts being misinterpreted as true variants [32].

- Solutions:

- Implement a molecular barcoding (UID) system. This allows bioinformatics tools to group reads originating from the same original DNA molecule (forming a UID family). A true mutation should be present in all members of a UID family [32].

- Adopt a duplex sequencing approach. Techniques like BiSeqS require a mutation to be identified on both strands of a molecularly barcoded DNA fragment to be called bona fide. This increases specificity by orders of magnitude by eliminating nearly all sequencing artifacts [32].

Experimental Protocol: Strand-Specific SNP Identification with BiSeqS

This protocol is adapted from a published method for ultra-specific mutation detection [32].

1. Sample Input and Bisulfite Conversion:

- Use high-quality, purified genomic DNA.

- Perform bisulfite conversion using a optimized kit/protocol to achieve >99.8% conversion efficiency. This is critical for making the two strands distinguishable [32].

2. Molecular Barcoding and Library Preparation:

- Primer Design: For each target region, design four strand-specific primers that bind to the bisulfite-converted sequence.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the bisulfite-converted DNA using a polymerase mixture capable of amplifying uracil-rich templates. The PCR primers must include unique molecular barcodes (UIDs) to tag each original template molecule [32].

3. Next-Generation Sequencing:

- Sequence the resulting libraries on your preferred NGS platform.

4. Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Separate reads by sample and UID.

- Alignment: Use a bisulfite-aware aligner like ARYANA-BS [30] to map reads to the reference genome.

- Variant Calling with Strand-Specific Filtering:

- Group reads into UID families.

- For a C>T candidate, require that it is present in all reads within a UID family (supermutant) [32].

- For strand-specific confirmation, require that the candidate is supported by a G>A change on the reverse strand from an independent UID family derived from the opposite original strand.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core BiSeqS process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Strand-Specific SNP Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemically converts unmethylated C to U, the foundation of the assay. | Ensure high conversion efficiency (>99.8%); kits from Zymo Research or Thermo Fisher are commonly used [32] [3]. |

| Polymerase for Uracil-Templates | Amplifies bisulfite-converted, uracil-containing DNA without bias. | Hot-start Taq polymerases (e.g., Platinum Taq, AccuPrime Taq). Do not use proof-reading polymerases [3]. |

| Bisulfite-Aware Aligner | Bioinformatics tool to accurately map BS-treated reads to a reference genome. | ARYANA-BS (context-aware) [30], Bismark (three-letter), or BSMAP (wildcard) [30]. |

| Molecular Barcoding Adapters | Unique identifiers ligated to or included in primers for DNA templates to enable error correction. | Available in many commercial NGS library prep kits or can be synthesized as modified oligos [32]. |

| Methylated & Unmethylated Control DNA | Validates the efficiency and specificity of the bisulfite conversion process. | Commercially available from various suppliers (e.g., EpiTect PCR Control DNA from Qiagen). |

| CRISPR/dCas9 System (for alternative methods) | For targeted enrichment or detection of specific alleles without amplification, as in the SNP-Chip [33] [34]. | Requires dCas9 protein and specific guide RNAs (sgRNAs) designed for the target sequence [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the double-masking procedure and why is it necessary for bisulfite sequencing data? Bisulfite conversion treatment deaminates unmethylated cytosines (C) to uracils (U), which are read as thymines (T) in subsequent sequencing. This process creates artificial C-to-T mutations in the sequencing data. Conventional variant callers, which assume complementary strands, cannot distinguish these artifacts from true single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The double-masking procedure is a computational pre-processing step that manipulates the alignment file to prevent these artifacts from being misinterpreted as variants, thereby enabling the use of conventional Bayesian variant callers like GATK or Freebayes [22].

Which specific nucleotide changes does the double-masking procedure target? The procedure is strand-specific. In a directional, paired-end sequencing library, it targets:

- C>T conversions on Mate 1 alignments to the Watson strand (FW+) and Mate 2 alignments to the Crick strand (RC-).

- G>A conversions on Mate 1 alignments to the Crick strand (FW-) and Mate 2 alignments to the Watson strand (RC+), as a G>A change on one strand corresponds to a C>T change on the opposite strand [22].

What are the specific steps of the double-masking algorithm? The procedure, as implemented in tools like Revelio, involves two key steps performed on individual alignments [22]:

- Nucleotide Conversion: Specific nucleotides in bisulfite contexts (e.g., C in a C>T context) are converted back to the corresponding reference base. This prevents sites with evidence stemming only from bisulfite conversion from being considered as candidate variants, saving computational resources.

- Base Quality (BQ) Score Manipulation: Any nucleotide considered a potential bisulfite-induced artifact is assigned a BQ score of 0. This effectively instructs the downstream variant caller to ignore this evidence, forcing the genotype call to be informed primarily by reads from the opposite, unaffected strand.

What is a common issue when applying this method to Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) data and how can it be solved? Users have reported abnormal variant calling results with RRBS data, where the output VCF contains almost exclusively A->G and T->C SNPs, which was not observed with Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) data [35].

- Potential Cause: This bias may be due to the specific nature of RRBS libraries, which sequence a reduced, CpG-rich portion of the genome. The interaction between the double-masking logic and the unique distribution of reads in RRBS might not be fully accounted for.

- Solution: Ensure you are using the latest version of the double-masking script (e.g., from the official Revelio or EpiDiverse SNP GitHub repositories). If the problem persists, consider using a specialized bisulfite SNP caller like Bis-SNP or bsgenova for RRBS data, as they are designed to handle various bisulfite sequencing protocols [12] [8] [10].

How does the performance of the double-masking method combined with conventional callers compare to specialized bisulfite SNP callers? Independent evaluations show that performance varies between tools, and the best choice depends on whether the research goal is to maximize precision or sensitivity [12]. The table below summarizes a performance comparison of various tools, including a pipeline using the double-masking method.

| Tool / Method | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Double-Masking + GATK/Freebayes [22] | Pre-processing method; enables use of conventional callers. | Marked improvement in precision-sensitivity on human and plant benchmarks compared to specialized tools. |

| Bis-SNP [12] [8] | Specialized tool; based on GATK framework; calls SNPs and methylation concurrently. | Optimizes for precision (low false positives). Correctly identified 96% of SNPs at 30x coverage in its original study. |

| Biscuit [12] | Specialized tool for bisulfite data. | Optimizes for sensitivity (low false negatives). |

| bsgenova [10] | Specialized tool; uses a Bayesian multinomial model; fast and robust. | A good compromise between sensitivity and precision; performs well with low-quality data and on chromosome X. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Excessive Number of False Positive C>T / G>A SNP Calls

- Symptoms: The final VCF file is dominated by C>T and G>A variant calls, many of which are likely bisulfite conversion artifacts.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Strand-Specific Masking: Verify that your sequencing library type (e.g., directional paired-end) is correctly specified in the double-masking command. Using the wrong strand specification will result in incomplete masking of artifacts [22].

- Low-Quality Base Calls: Check the quality of your original sequencing data and alignment. While double-masking sets BQ=0 for artifacts, overall low base quality can still confound the variant caller. Ensure you use appropriate quality trimming and alignment parameters [22].

- Ineffective Masking: Inspect the masked BAM file visually in a tool like IGV to confirm that the base quality scores at suspected artifact positions have indeed been set to zero.

Problem: Low Number of Variants or High Number of False Negatives

- Symptoms: The variant caller outputs very few SNPs, potentially missing true positive variants.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Overly Stringent Masking: The double-masking procedure might be too aggressive. Review the parameters for the nucleotide conversion step. Check if true variants are being removed in the pre-selection step. You may need to adjust the masking logic, though this is typically handled within the script [22].

- Variant Caller Parameters: The conventional variant caller (e.g., GATK) may be using default filters that are too strict for the masked data. Try adjusting the

--min-base-quality-score(a value of 1 is used in the method validation [22]) and other confidence thresholds to be more lenient. - Low Coverage: Bisulfite conversion and PCR duplication can reduce effective coverage. Ensure your data has sufficient depth (>20x) for reliable variant calling.

Problem: Abnormal Variant Substitution Patterns in RRBS Data

- Symptoms: As reported in the GATK forum, the output VCF for RRBS data contains almost only A->G and T->C SNPs, which is biologically implausible [35].

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Protocol-Specific Bias: This appears to be a specific issue with RRBS data when using the double-masking method with GATK's HaplotypeCaller. The fundamental cause may be complex, relating to the enrichment for CpG sites and the behavior of the caller.

- Switch to a Specialized Caller: The most straightforward solution is to use a SNP caller designed for bisulfite data, such as Bis-SNP or bsgenova, which have been validated on RRBS data and can handle its specific characteristics [8] [10] [9].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Double-Masking and Variant Calling from WGBS Data

The following protocol is adapted from the Revelio validation pipeline [22].

Read Trimming and Quality Control

- Tool:

cutadapt - Action: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the raw FASTQ files.

- Quality Control: Assess read quality before and after trimming using

FastQC.

- Tool:

Alignment to Reference Genome

- Tool:

BWA-meth(or another bisulfite-aware aligner likeBismark). - Action: Map the trimmed bisulfite-treated reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome.

- Output: A BAM file containing the aligned reads.

- Tool:

Post-Alignment Processing

- Tool:

SAMtools - Action: Merge BAM files from multiple lanes, if applicable.

- Tool:

Picard MarkDuplicates - Action: Identify and mark PCR duplicate reads to avoid overcounting identical DNA fragments.

- Tool:

Application of the Double-Masking Procedure

- Tool:

Revelio(or a custom script implementing Algorithm 1 from the source paper). - Input: The processed BAM file from the previous step.

- Action: The script executes the two-step masking process:

- Converts specific context-based nucleotides to the reference base.

- Sets the base quality score to 0 for nucleotides potentially arising from bisulfite conversion.

- Output: A masked BAM file ready for conventional variant calling.

- Tool:

Variant Calling with a Conventional Tool

- Tool:

GATK UnifiedGenotyper/HaplotypeCallerorFreebayes. - Critical Parameters:

--min-base-quality-score 1(or-minQ 1in Freebayes)--standard-min-confidence-threshold-for-calling 1(for GATK)

- Action: Call variants from the masked BAM file as you would with standard sequencing data.

- Output: A VCF file containing the SNP calls.

- Tool:

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software tools and resources essential for implementing the double-masking approach.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| BWA-meth [22] | Bisulfite-aware aligner | Maps bisulfite-converted sequencing reads to a reference genome. |

| Revelio [22] | Double-masking script | The core pre-processing script that performs nucleotide conversion and base quality score manipulation on the BAM file. |

| EpiDiverse SNP [22] | Implementation pipeline | A ready-to-use workflow that incorporates the double-masking method with Freebayes for variant calling. |

| GATK [22] [36] | Conventional variant caller | A widely-used Bayesian variant caller that can be used on the masked BAM files. Its HaplotypeCaller or UnifiedGenotyper modules are applicable. |

| Freebayes [22] | Conventional variant caller | A Bayesian genetic variant detector designed to find small polymorphisms. Works effectively with the masked data. |