Essential Quality Control Metrics for Histone ChIP-Seq: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing robust quality control in histone ChIP-seq experiments, crucial for reliable epigenomic research and drug discovery.

Essential Quality Control Metrics for Histone ChIP-Seq: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing robust quality control in histone ChIP-seq experiments, crucial for reliable epigenomic research and drug discovery. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we detail critical QC metrics including library complexity, FRiP scores, replicate concordance, and peak calling strategies tailored for broad histone marks. The guide incorporates current ENCODE standards, practical troubleshooting advice, and comparative analysis of computational tools to help researchers optimize experimental design, validate data quality, and ensure reproducible results in studying histone modifications across diverse biological contexts.

Understanding Histone ChIP-Seq QC: Core Concepts and Critical Metrics

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Enrichment and High Background

Problem: The ChIP-seq experiment yields a low fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) and shows high background signal, making it difficult to distinguish true enrichment.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Quality Metric to Check |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Specificity | Validate antibody via immunoblot (primary band >50% signal) or immunofluorescence prior to ChIP [1]. | Verify antibody characterization data is available and passes ENCODE standards [2] [1]. |

| Insufficient Sequencing Depth | Sequence deeper: ≥45 million usable fragments per replicate for broad histone marks and ≥20 million for narrow marks [2]. | Check if the number of peaks stabilizes in a saturation analysis [3]. |

| Poor Chromatin Fragmentation | Optimize enzymatic digestion or sonication conditions via a time-course experiment to achieve DNA fragments between 150-900 bp [4]. | Check agarose gel for a smear of DNA in the desired size range post-fragmentation [4]. |

| Inadequate Input Control | Use a matched input control sequenced to a higher depth than the ChIP sample [2] [3]. | Confirm the ChIP-to-input read ratio is at least 1:1, preferably 2:1 [5]. |

Guide 2: Resolving Peak Calling and Data Interpretation Issues

Problem: The identified peaks do not match biological expectations (e.g., broad domains appear as fragmented narrow peaks, or peaks fall in implausible genomic regions).

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Quality Metric to Check |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Peak Calling Strategy | For broad marks (e.g., H3K27me3), use tools like SICER2 or MACS2 in --broad mode. For narrow marks (e.g., H3K4me3), use standard narrow peak callers [5] [6]. |

Inspect called peaks in a genome browser (e.g., IGV) to confirm they match the expected chromatin pattern [5]. |

| Unfiltered Artifact Regions | Filter peaks against the ENCODE blacklist of known artifact-prone regions (e.g., centromeres, telomeres) [5] [7]. | Check the RiBL (Reads in Blacklist Regions) metric; a high percentage (>1%) indicates potential artifacts [7]. |

| Poor Replicate Concordance | Perform peak calling on individual biological replicates, not just pooled data. Assess concordance using the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) [5]. | Calculate the FRiP score for each replicate individually; high variability between replicates indicates inconsistency [5] [7]. |

| Over-fragmented Chromatin | Use the minimal sonication or enzymatic digestion required to achieve the desired fragment size. Over-sonication can damage chromatin and reduce signal [4]. | On an agarose gel, >80% of DNA fragments should not be shorter than 500 bp [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical quality control metrics for histone ChIP-seq data, and what are their ideal values?

The ENCODE consortium provides guidelines for key quality metrics [2]. The most critical are summarized in the table below.

| Metric | Ideal Value / Range | Description and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) | Varies by target; generally >1-5% [7] | Measures enrichment and signal-to-noise ratio. The proportion of all sequenced reads that fall within called peak regions [2] [7]. |

| NSC (Normalized Strand Cross-correlation) | >1.05 [3] | Assesses signal-to-noise ratio based on the clustering of reads from forward and reverse strands. Higher values indicate stronger enrichment [3]. |

| RSC (Relative Strand Cross-correlation) | >0.8 [3] | A more robust version of NSC that is less sensitive to background. Values below 0.5 often indicate a failed experiment [5] [3]. |

| PBC (PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient) | PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 10 [2] | Measures library complexity. Low values indicate over-amplification and low diversity in the sequencing library [2] [3]. |

| RiBL (Reads in Blacklist Regions) | As low as possible (<1%) [7] | Indicates the percentage of reads in known artifact regions. A high value suggests technical bias [7]. |

Q2: How much sequencing depth is required for my histone ChIP-seq experiment?

The required depth depends on whether you are studying a broad or narrow histone mark. The ENCODE consortium recommends [2]:

- Broad histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K36me3): 45 million usable fragments per biological replicate.

- Narrow histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K9ac): 20 million usable fragments per biological replicate.

Q3: My biological replicates show poor overlap. What should I do?

First, calculate standard QC metrics (FRiP, NSC, RSC) for each replicate individually to ensure both are of high quality [5] [7]. If quality is good but overlap is poor, it may indicate underlying biological variability or an issue with the antibody. Do not merge the replicates for peak calling until you have established they are highly concordant. Using the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) framework is a robust method for assessing replicate consistency [5].

Q4: What is the difference between analyzing broad histone marks (like H3K27me3) and narrow marks (like H3K4me3)?

The key differences lie in the expected peak morphology and the subsequent analysis tools and parameters.

Q5: Why is an input control sample essential, and what are the best practices for it?

An input control (total DNA from sonicated chromatin that has not been immunoprecipitated) is crucial for distinguishing true enrichment from background noise caused by technical biases like open chromatin or GC-rich regions [5] [8]. Best practices include:

- Use a matched input: The input should come from the same cell type and be processed identically to the ChIP sample [2].

- Sequence it deeply: The input control should be sequenced to a higher depth than the ChIP sample to ensure it accurately models the background [3].

- Do not use IgG as a universal substitute: While sometimes used, an input DNA control is generally preferred for histone marks as it more accurately captures background structure [5].

Experimental Workflow and Quality Control

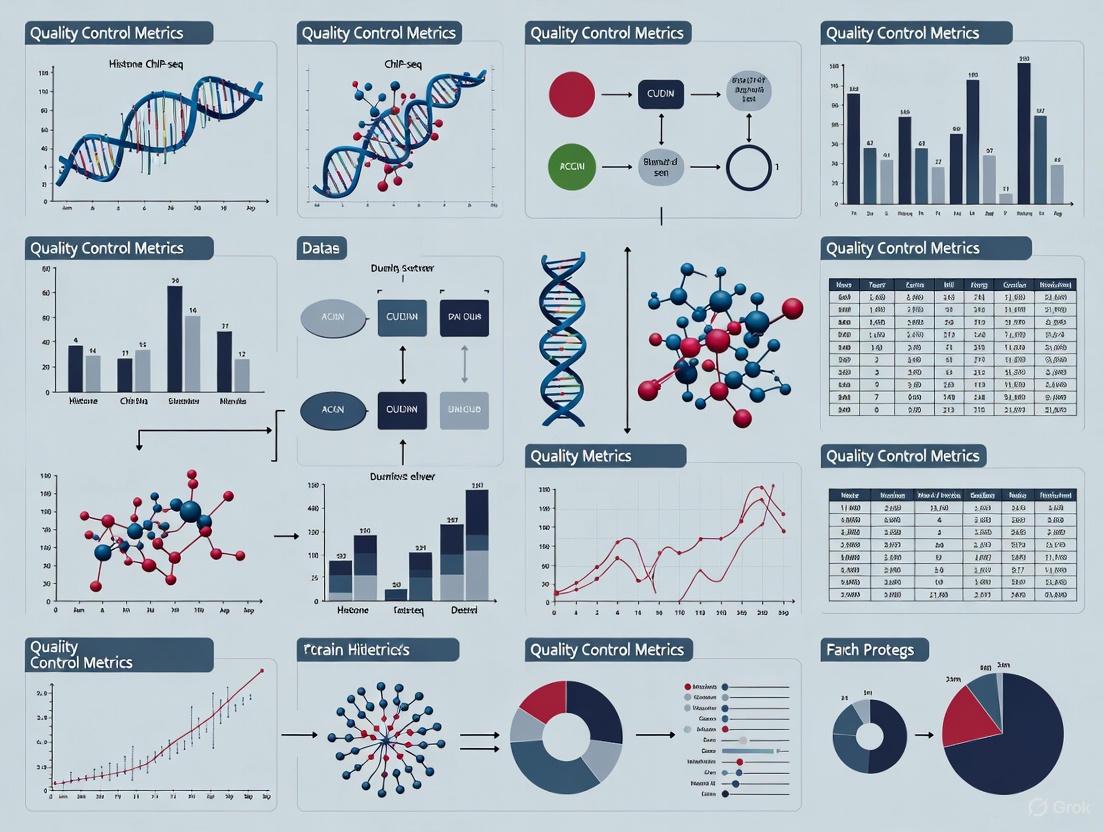

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a histone ChIP-seq workflow, highlighting critical quality checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibody | Binds specifically to the target histone modification for immunoprecipitation. | Must be characterized by immunoblot (single strong band) or immunofluorescence [1]. Check ENCODE-approved antibodies. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatically digests chromatin to yield fragments of 1-6 nucleosomes. | Requires titration for each cell/tissue type to avoid over- or under-digestion [4]. |

| Input Control DNA | Total fragmented chromatin DNA not subjected to IP. Serves as the background model. | Must be from the same source and sequenced deeper than the ChIP sample [2] [3]. |

| Sonication Shearing | Physically shears cross-linked chromatin via ultrasonic energy. | Requires a time-course to optimize for each cell type; over-sonication can damage epitopes [4]. |

| Blacklist Regions File | A curated BED file of genomic regions known to produce artifactual signals. | Filter final peak calls against the species-appropriate ENCODE blacklist to remove false positives [5] [7]. |

For researchers conducting histone ChIP-seq experiments, robust quality control (QC) is the foundation of biologically meaningful data. This guide addresses frequent challenges related to three essential QC metrics: library complexity, sequencing depth, and signal-to-noise ratios. By troubleshooting these key areas, you can ensure your data meets the standards required for publication and robust analysis, particularly within the framework of a thesis on quality control metrics for histone ChIP-seq.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Library Complexity

Problem: Low library complexity, indicated by high levels of PCR duplicates, reduces the effective resolution of your experiment and can lead to false positives.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check Your Metrics: Calculate the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF), PCR Bottleneck Coefficient 1 (PBC1), and PBC2. Preferred standards are NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 [2] [9] [1]. Low values indicate over-amplification or suboptimal immunoprecipitation.

- Identify the Cause:

- Over-cross-linking or excessive sonication can damage chromatin and reduce complexity.

- Insufficient starting material leads to over-amplification during library preparation. For histone marks, the ENCODE consortium recommends starting with 1-10 million cells, depending on the abundance of the target [10].

- Inefficient immunoprecipitation caused by a low-quality antibody will yield less unique material.

- Apply Corrective Measures:

- Optimize cell fixation and sonication conditions to generate fragments of 200-300 bp without destroying epitopes.

- Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) in your library prep to accurately identify and account for PCR duplicates.

- Employ advanced protocols like HT-ChIPmentation, which uses Tn5 transposase for tagmentation and minimizes material loss, thereby maintaining high complexity even with low cell numbers (e.g., a few thousand cells) [11].

Troubleshooting Inadequate Sequencing Depth

Problem: Insufficient sequencing reads result in failure to saturate the detection of enriched regions, missing true binding sites or broad domains, and generating irreproducible results.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Perform Saturation Analysis: Use tools like the preseq package to predict how many additional unique peaks you would discover with deeper sequencing [3] [12]. A well-saturated experiment shows less than a 1% increase in peaks with an additional million reads [12].

- Follow Target-Specific Standards: The required depth depends on whether your histone mark is "narrow" or "broad". The table below summarizes the ENCODE consortium's current standards for human data [2] [9]:

Table: ENCODE Sequencing Depth Standards for Histone ChIP-seq

| Histone Mark Type | Examples | Minimum Usable Fragments per Replicate | Recommended Fragments per Replicate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac | 20 million | >20 million [9] |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me1 | 45 million | >45 million [2] [9] |

| Exception (H3K9me3) | Enriched in repetitive regions | 45 million total mapped reads | >45 million [2] [9] |

- Increase Depth Systematically: If saturation analysis shows your depth is inadequate, combine data from technical replicates or sequence deeper in subsequent experiments. Note that control (input) samples should be sequenced at the same depth or deeper than the ChIP sample to ensure adequate genomic coverage for background modeling [3].

Troubleshooting Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Problem: A low signal-to-noise ratio makes it difficult to distinguish true enrichment from background, leading to poor peak calling.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Calculate Key Metrics:

- FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks): This measures the enrichment efficiency. A higher FRiP (e.g., >1-5%, though target-dependent) indicates a successful IP [13].

- Strand Cross-Correlation: This analysis assesses the clustering of reads. It produces two key metrics: the Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) and the Relative Strand Coefficient (RSC). High-quality data typically has NSC > 1.05 and RSC > 0.8 [3] [1]. Low values indicate high background noise.

- Verify Antibody Quality: This is the most critical factor. An antibody suitable for ChIP-seq should show ≥5-fold enrichment in ChIP-PCR assays at positive-control regions compared to negative controls [10] [1]. Always use antibodies characterized by immunoblot or immunofluorescence to confirm specificity [1].

- Use Appropriate Controls: Always include a matched input chromatin control (not non-specific IgG) to account for biases in chromatin fragmentation, sequencing efficiency, and open chromatin regions [10] [1].

- Optimize Chromatin Preparation: For histone modifications, using micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to digest native chromatin to mononucleosomes can provide higher resolution and lower background than sonication of cross-linked chromatin [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing low signal-to-noise ratio issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My data fails the PBC metrics but the peak caller still identified thousands of peaks. Can I trust my results? Proceed with extreme caution. Low library complexity means your data is based on a small number of unique genomic fragments, making the results non-representative and highly irreproducible. Peaks called from low-complexity libraries are enriched for false positives and should not be used for biological interpretation [3] [1].

Q2: How many biological replicates are absolutely necessary for a robust histone ChIP-seq experiment? The ENCODE standard mandates a minimum of two biological replicates to account for technical and biological variability [2] [9] [1]. Replicate concordance is often measured using the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR). For transcription factors, a successful experiment must have a rescue ratio and self-consistency ratio both less than 2 [13]. While this is a TF standard, the principle of assessing reproducibility is universally important.

Q3: Are there more quantitative methods for comparing ChIP-seq signals between different conditions? Yes, traditional methods can be limited for direct quantitative comparisons. The siQ-ChIP method has been developed to establish an absolute, physical quantitative scale for ChIP-seq without requiring spike-in reagents. It uses mass conservation laws to calculate the immunoprecipitation efficiency, allowing for more direct and accurate comparisons of histone modification abundance across samples [14].

Q4: I am working with very low cell numbers. Are there specialized protocols? Yes, standard ChIP-seq protocols can be challenging with low cell inputs. Specialized methods like HT-ChIPmentation are designed for this purpose. By combining ChIP with a streamlined tagmentation-based library preparation, it minimizes material loss and has been successfully used to generate high-quality data from just a few thousand FACS-sorted cells [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Histone ChIP-seq QC

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of target histone mark. | Must be ChIP-grade; validate via immunoblot/immunofluorescence and show ≥5-fold enrichment in ChIP-PCR [10] [1]. |

| Protein G-coupled Magnetic Beads | Capture of antibody-bound chromatin complexes. | Preferred for ease of use and efficient washing steps [11]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Digestion of native chromatin for histone mark mapping. | Can provide higher resolution for nucleosome-scale analysis [10]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme for "tagmentation" in ChIPmentation protocols. | Simultaneously fragments DNA and adds sequencing adapters, streamlining library prep [11]. |

| Strand Cross-Correlation Tools (e.g., in SPP) | Computes NSC and RSC metrics. | Critical for objective assessment of signal-to-noise ratio [3]. |

| Complexity Assessment Tools (e.g., preseq) | Predicts library complexity and estimates yield from deeper sequencing. | Helps determine if sequencing depth is adequate [3] [12]. |

| Peak Caller with Broad Mark Support (e.g., MACS2, SPP) | Identifies statistically significantly enriched genomic regions. | Must use a tool and settings appropriate for broad histone domains (e.g., MACS2 in -broad mode) [12]. |

FAQs: ENCODE Standards for Histone ChIP-seq

Q1: What are the current ENCODE standards for histone ChIP-seq experiments regarding replicates and controls?

Current ENCODE standards require at least two biological replicates (isogenic or anisogenic) for each histone ChIP-seq experiment, with exemptions granted only for assays using EN-TEx samples due to limited material availability. Each ChIP-seq experiment must include a corresponding input control experiment that matches the run type, read length, and replicate structure. All antibodies must be characterized according to ENCODE Consortium standards specific for histone modifications and chromatin-associated proteins established in October 2016. [2]

Q2: What are the specific read depth requirements for different types of histone marks?

ENCODE distinguishes between broad and narrow histone marks, each with different sequencing depth requirements. These standards have evolved from ENCODE2 to current specifications, reflecting technological improvements and increased understanding of data requirements. [2]

Table: Histone ChIP-seq Read Depth Requirements

| Histone Mark Type | ENCODE2 Standards (Million usable fragments/replicate) | Current Standards (Million usable fragments/replicate) | Example Marks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad marks | 20 | 45 | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K4me1 |

| Narrow marks | 10 | 20 | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac |

| Exception (H3K9me3) | 20 (broad) | 45 (with special considerations for repetitive regions) | H3K9me3 only |

Q3: What library complexity metrics does ENCODE use, and what are the preferred values?

ENCODE uses three primary metrics to assess library complexity: Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF), PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1 (PBC1), and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 2 (PBC2). The preferred values are NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10. These metrics help identify potential issues with over-amplification and assess the complexity of the sequencing library. [2]

Q4: How has the ENCODE approach to data quality assessment evolved?

The ENCODE Consortium analyzes data quality using multiple metrics, recognizing that no single measurement can identify all high-quality or low-quality samples. Quality assessment has evolved to include uniform processing pipelines that generate standardized quality metrics. The consortium emphasizes that comparisons within an experimental method—such as comparing replicates to each other—are essential for identifying potential stochastic error. Data that do not meet minimum cutoff values are flagged on the ENCODE portal according to severity of the error. [15]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Library Complexity in Histone ChIP-seq

Symptoms: Low NRF, PBC1, or PBC2 scores in quality control reports.

Solutions:

- Optimize fragmentation conditions: Ensure appropriate sonication or enzymatic fragmentation to generate optimal fragment sizes.

- Reduce PCR amplification cycles: Implement qPCR monitoring during library amplification to prevent over-amplification.

- Increase starting material: Use the recommended cell numbers according to current ENCODE experimental guidelines.

- Verify antibody efficiency: Ensure antibodies meet ENCODE characterization standards (October 2016 histone modification standards). [2]

Issue: Low Replicate Concordance

Symptoms: Low Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) scores or poor correlation between replicates.

Solutions:

- Standardize experimental conditions: Ensure identical processing for all replicates from cell culture to sequencing.

- Verify replicate type: Confirm whether replicates are biological (isogenic or anisogenic) or technical, as standards differ.

- Check sequencing depth: Ensure each replicate meets the minimum required read depth for your specific histone mark (see Table above).

- Review input controls: Confirm that input controls match replicates in read length, run type, and processing. [2]

Issue: Inadequate Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Symptoms: Low FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) scores, poor strand cross-correlation metrics.

Solutions:

- Verify antibody specificity: Confirm proper antibody validation according to ENCODE standards.

- Optimize immunoprecipitation conditions: Titrate antibody amounts and include appropriate wash stringency.

- Validate with positive controls: Include known positive control regions in analysis.

- Assess with strand cross-correlation: Calculate normalized strand cross-correlation coefficient (NSC) and relative strand cross-correlation coefficient (RSC). High-quality experiments typically show distinct peak of enrichment at the predominant fragment length. [16]

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

ENCODE Uniform Processing Pipeline for Histone ChIP-seq

The ENCODE consortium has developed standardized analysis pipelines for histone ChIP-seq data. The pipeline schematic below illustrates the key processing stages:

Histone ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

The experimental workflow for generating ENCODE-compliant histone ChIP-seq data involves both wet-lab and computational steps:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for ENCODE-Compliant Histone ChIP-seq

| Reagent/Resource | Function | ENCODE Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Specific immunoprecipitation of target histone modifications | Must meet October 2016 characterization standards for histone modifications [2] |

| Input Control | Control for background signal and technical artifacts | Must match experimental samples in run type, read length, and replicate structure [2] |

| Uniform Processing Pipeline | Standardized data analysis | Available on GitHub; processes FASTQ to peaks and signal tracks [2] |

| Reference Genomes | Read alignment and annotation | GRCh38 (human) or mm10 (mouse); other assemblies not supported [2] |

| Quality Metrics Tools | Assessment of data quality | Calculate NRF, PBC, FRiP, strand cross-correlation [15] |

Data Quality Metrics and Interpretation

Key Quality Metrics for Histone ChIP-seq

ENCODE uses multiple quality metrics to evaluate histone ChIP-seq data. The table below summarizes the critical metrics and their interpretation guidelines:

Table: Histone ChIP-seq Quality Metrics Interpretation Guide

| Metric | Calculation Method | Excellent | Acceptable | Problematic | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) | Fraction of all mapped reads falling into peak regions | > 0.3 | 0.1 - 0.3 | < 0.1 | Measures enrichment efficiency |

| NSC (Normalized Strand Cross-correlation) | Ratio of cross-correlation at fragment length to background | > 1.05 | 1.01 - 1.05 | < 1.01 | Assesses signal-to-noise ratio |

| RSC (Relative Strand Cross-correlation) | Ratio of fragment-length cross-correlation to read-length cross-correlation | > 1 | 0.5 - 1 | < 0.5 | Evaluates library quality |

| NRF (Non-Redundant Fraction) | Fraction of non-redundant mapped reads | > 0.9 | 0.8 - 0.9 | < 0.8 | Measures library complexity |

| PBC1 (PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1) | Ratio of distinct locations with one read to total distinct locations | > 0.9 | 0.8 - 0.9 | < 0.8 | Assesses amplification bias |

| PBC2 (PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 2) | Ratio of distinct locations with one read to two reads | > 10 | 5 - 10 | < 5 | Additional measure of complexity |

Historical Evolution of ENCODE Standards

The ENCODE Consortium's standards have evolved significantly across project phases (ENCODE2, ENCODE3, ENCODE4), reflecting technological advancements and increased understanding of functional genomics data requirements. Key developments include:

- Increased sequencing depths for both broad and narrow histone marks (see Table above)

- Implementation of uniform processing pipelines for consistent data analysis across the consortium [17]

- Enhanced antibody validation requirements with specific standards for different protein categories [18]

- Development of comprehensive quality metric suites that recognize the multidimensional nature of data quality assessment [15]

The ENCODE Data Portal now hosts over 23,000 functional genomics experiments with standardized processing and quality metrics, representing a vast resource for comparative analysis and methodology development. [17]

The Role of Biological Replicates and Controls in Experimental Design

FAQs on Experimental Design

1. Why are biological replicates essential in ChIP-seq experiments?

Biological replicates are fundamental for distinguishing true biological signals from experimental noise. They account for natural variation between different biological samples (e.g., cells from different passages or animals) and are required for robust statistical analysis. While the ENCODE consortium mandates a minimum of two biological replicates, recent evidence suggests that three or more are ideal. Increasing the number of replicates improves the reliability of peak identification and allows for the detection of binding sites that might be missed with only two replicates [19] [20] [1].

2. What is the difference between a biological replicate and a technical replicate?

A biological replicate involves processing independently derived biological samples (e.g., cells from different cell culture plates, or tissues from different animals) through the entire ChIP-seq protocol. This is crucial for assessing the variability in the broader population. In contrast, a technical replicate involves taking a single biological sample and processing it multiple times through the library preparation and sequencing steps. For ChIP-seq, biological replicates are required; technical replicates are generally not necessary for sequencing [21] [20].

3. Why is a control sample necessary, and what type should I use?

Controls are critical for modeling the local background signal and for accurately distinguishing true enrichment from experimental artifacts and noise. It is impossible to reliably detect binding events (peaks) without them [21]. The two primary types of controls are:

- Input Chromatin: This is a sample of the sonicated or digested chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation. It is the more widely used and generally less biased control [21].

- IgG IP: This uses a non-specific immunoglobulin during the immunoprecipitation step to control for non-specific antibody binding. This method can sometimes suffer from issues with library complexity [21]. The input chromatin is often recommended. Your control should be sequenced to at least the same depth as your ChIP samples, and each biological replicate of ChIP should have its own matching control sample sequenced separately [21] [2].

4. How many sequencing reads are sufficient for my histone ChIP-seq experiment?

The required sequencing depth depends heavily on whether the histone mark or chromatin-associated protein produces "broad" or "narrow" (punctate) enrichment patterns. Broad marks cover large genomic domains and require significantly deeper sequencing. The table below summarizes the current recommendations from authoritative sources.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Signal Type | Examples | Recommended Depth (per replicate) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Source / Narrow Marks | Transcription Factors, H3K4me3, H3K9ac | 10 - 25 million usable fragments | [21] [2] [20] |

| Broad Enrichment Domains | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K4me1, H3K9me3 | 40 - 45 million usable fragments | [21] [2] |

Note: H3K9me3 is a special case among broad marks because it is enriched in repetitive regions. For tissues and primary cells, the ENCODE consortium recommends 45 million total mapped reads per replicate for H3K9me3 [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background or Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

A high background can obscure genuine binding sites and lead to false positives during peak calling.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Antibody Specificity: The antibody may have poor reactivity or cross-react with other proteins. Always use a ChIP-validated antibody and characterize it according to ENCODE guidelines, which include immunoblot analysis to ensure a single primary band constitutes at least 50% of the signal [1].

- Inadequate Chromatin Fragmentation: Under-sheared (too large) chromatin fragments can lead to increased background and lower resolution. Optimize your sonication or enzymatic digestion protocol via a time-course experiment to achieve a fragment size of 200-1000 bp, with a majority under 1 kb [22] [23].

- Non-specific Binding: Pre-clear your lysate with protein A/G beads before immunoprecipitation to remove proteins that bind non-specifically. Ensure all buffers are fresh and of high quality [23].

- Over-crosslinking: Excessive crosslinking can mask antibody epitopes and reduce signal intensity. Reduce the formaldehyde fixation time (within a 10-30 minute range) and always quench with glycine [23] [24].

Problem: Low Signal or Poor Enrichment

This issue results in a low number of identifiable peaks and a low Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) score.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Starting Material: Too little chromatin will yield poor results. Use 5-10 µg of cross-linked and fragmented chromatin per immunoprecipitation reaction. For tissues with low native chromatin yield like brain or heart, you may need to start with more than 25 mg of tissue per IP [22].

- Suboptimal Antibody Amount: Too little antibody will result in poor enrichment. Titrate your antibody; recommended amounts are typically between 1-10 µg per IP [23].

- Over-sonication: Fragmenting chromatin to very short sizes (e.g., mostly mononucleosomes) can damage the chromatin and diminish signal, especially for longer amplicons. Use the minimal sonication required to achieve the desired fragment size [22].

- Inefficient Immunoprecipitation: Ensure the antibody subclass is compatible with your Protein A/G beads. An overnight incubation at 4°C often increases signal and specificity compared to shorter incubations [24].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Biological Replicates

High variability between replicates makes it difficult to identify a consensus set of binding sites.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Replicates: With only two replicates, the inherent noise of ChIP-seq can lead to unreliable conclusions. Increase the number of biological replicates to three or more. A "majority rule" (where a peak is called if it appears in >50% of replicates) has been shown to yield more reliable peaks than requiring 100% concordance between two replicates [19].

- Batch Effects: Processing samples in different batches (e.g., different days) can introduce technical variation. Whenever possible, process replicates for all conditions together. If batches are unavoidable, ensure that each batch contains replicates for every condition so that batch effects can be measured and corrected bioinformatically [20].

- Variable Library Quality: Ensure that all replicates are prepared and sequenced consistently in terms of read length and run type [2]. Monitor library complexity metrics like the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF > 0.9) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient (PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 10) to ensure all replicate libraries are of high and comparable quality [2] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Histone ChIP-seq Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Validated Antibody | Binds specifically to the histone modification or chromatin protein of interest. | Must be validated for ChIP. Check for ENCODE certification or perform immunoblot/immunofluorescence validation. Lot-to-lot variability can be significant [20] [1]. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Facilitates capture and purification of the antibody-target complex. | Ensure the bead type is compatible with your antibody's host species and subclass. Always resuspend beads thoroughly before use [24]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatically digests chromatin to yield mononucleosomes for mapping nucleosome positions. | Preferred over sonication for histone mark ChIP as it provides more precise mapping. Requires optimization of enzyme concentration to avoid over- or under-digestion [22] [25]. |

| Sonicator | Shears cross-linked chromatin into small fragments via physical disruption. | Required for cross-linked ChIP (X-ChIP). Power settings and duration must be optimized for each cell or tissue type to achieve 200-1000 bp fragments [22] [1]. |

| Input DNA Control | Provides the background model for the genome-wide signal. | Consists of cross-linked and fragmented chromatin that is not subjected to immunoprecipitation. Should be sequenced to the same or greater depth than IP samples [21] [2]. |

| Spike-in Control | Allows for normalization between samples with global changes in histone mark levels. | Comprises chromatin from a distant organism (e.g., Drosophila for human/mouse samples). Helps qualitatively compare binding affinity across different conditions [20]. |

Essential Workflow Diagrams

Histone ChIP-seq Workflow with Controls

Analysis Strategy for Multiple Replicates

The analysis of histone modifications through Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become a fundamental technique in epigenetics research and drug discovery. A crucial aspect of this analysis involves correctly categorizing the resulting enrichment patterns as either broad domains or narrow peaks. This distinction is not merely analytical but reflects fundamental biological differences in how histone marks function across the genome. Broad domains typically cover large genomic regions such as entire gene bodies, while narrow peaks are highly localized signals often found at specific regulatory elements like promoters or enhancers [26] [27].

Within the framework of quality control metrics for histone ChIP-seq data research, proper categorization directly impacts downstream analysis validity. Using inappropriate peak-calling parameters can lead to both false positives and false negatives, potentially misdirecting research conclusions and therapeutic development efforts. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidelines to help researchers navigate these complexities, with specific troubleshooting advice for common experimental challenges encountered when working with different classes of histone modifications.

Fundamental Concepts: Histone Mark Classification and Functional Implications

Characterizing Broad vs. Narrow Histone Modifications

Histone modifications form two functionally distinct categories based on their genomic distribution patterns and roles in gene regulation. The table below summarizes the primary characteristics and functions of the most extensively studied histone marks.

Table 1: Functional Classification of Major Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Peak Type | Genomic Location | Functional Role | Associated Processes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Narrow | Promoters | Transcriptional activation | Initiation of transcription [28] [29] |

| H3K9ac | Narrow | Enhancers, Promoters | Transcriptional activation | Open chromatin formation [28] [29] |

| H3K27ac | Narrow | Enhancers, Promoters | Transcriptional activation | Active enhancer marking [28] [29] |

| H3K27me3 | Broad | Promoters in gene-rich regions | Transcriptional repression | Developmental gene silencing [28] [27] [29] |

| H3K9me3 | Broad | Satellite repeats, telomeres, pericentromeres | Heterochromatin formation | Permanent gene silencing [28] [29] |

| H3K36me3 | Broad | Gene bodies | Transcriptional elongation | Active transcription [27] [29] |

Biological Significance of Peak Architecture

The spatial organization of histone modifications into broad or narrow patterns corresponds directly to their mechanistic roles in chromatin regulation. Narrow peaks typically mark precise regulatory elements where specific protein complexes are recruited. For example, H3K4me3 at promoters facilitates the assembly of pre-initiation complexes and recruitment of RNA polymerase II [29]. In contrast, broad domains often correspond to large-scale chromatin states that define functional genomic compartments. H3K27me3 forms extensive repressive domains that silence developmental gene clusters, while H3K36me3 coats actively transcribed gene bodies, reflecting the process of transcriptional elongation [27] [29].

These patterns have profound implications for understanding gene regulatory mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets. Disruption of broad domains, particularly H3K27me3 patterns, is frequently observed in cancers and developmental disorders, making them attractive targets for epigenetic therapies [28].

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do I determine whether my histone mark typically produces broad or narrow peaks?

The expected peak type depends on the specific biological function of the histone mark. Generally, marks associated with precise regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) produce narrow peaks, while those associated with large chromatin domains or gene bodies form broad domains. Consult the reference table below for common classifications:

Table 2: Peak Type Classification for Common Histone Modifications

| Expected Peak Type | Histone Modifications |

|---|---|

| Narrow Peaks | H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac |

| Broad Domains | H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K36me3 |

If you are working with a mark not listed here, examine its biological function. Marks that establish large chromatin environments (e.g., heterochromatin) typically produce broad domains, while those marking specific regulatory sites produce narrow peaks. The ENCODE consortium provides detailed guidelines for classifying and analyzing different histone modifications [1].

FAQ 2: What are the best practices for peak calling with mixed enrichment patterns?

Some histone marks exhibit both narrow and broad enrichment patterns across different genomic contexts. H3K27me3, for instance, can form broad domains over repressed gene clusters while also appearing as narrow peaks at specific regulatory elements [27]. For such mixed patterns:

Use algorithms capable of detecting both peak types simultaneously. Tools like hiddenDomains employ hidden Markov models that identify both enriched peaks and domains without prior specification of peak type [27].

Leverage specialized broad peak-calling options in established tools. MACS2 and Homer include parameters specifically designed for broad domain detection [27].

Validate calls with orthogonal methods. Compare your results with expression data (RNA-seq) or other epigenetic marks to confirm biological relevance [27].

Adjust metrics for quality assessment. For broad marks, focus on domain characteristics rather than peak number, and use metrics like FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) calculated specifically for broad domains [30].

FAQ 3: Why is my chromatin fragmentation yielding inconsistent results across tissue types?

Chromatin fragmentation efficiency varies significantly between tissue types due to differences in cellular composition and extracellular matrix. The table below illustrates typical chromatin yields from different tissues using standardized protocols:

Table 3: Expected Chromatin Yields from Different Tissue Types

| Tissue / Cell Type | Total Chromatin Yield (per 25 mg tissue) | Expected DNA Concentration | Recommended Homogenization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 20–30 µg | 200–300 µg/ml | Medimachine or Dounce homogenizer [31] |

| Liver | 10–15 µg | 100–150 µg/ml | Dounce homogenizer [31] |

| Brain | 2–5 µg | 20–50 µg/ml | Dounce homogenizer (required) [31] |

| Heart | 2–5 µg | 20–50 µg/ml | Dounce homogenizer [31] |

| HeLa Cells | 10–15 µg (per 4×10⁶ cells) | 100–150 µg/ml | Medimachine or Dounce homogenizer [31] |

Troubleshooting recommendations:

- For low-yield tissues (brain, heart): Increase starting material and use Dounce homogenization for better cell disruption [31].

- Optimize fragmentation method: For enzymatic fragmentation, titrate micrococcal nuclease concentration using a time-course experiment [31].

- For sonication-based protocols: Conduct sonication time-course experiments and examine fragment size on agarose gels after each round of sonication [31] [32].

FAQ 4: What control samples are most appropriate for histone ChIP-seq experiments?

The choice of control sample significantly impacts background estimation and peak calling accuracy:

Whole Cell Extract (WCE) / "Input" DNA: Most common control; consists of sonicated chromatin taken prior to immunoprecipitation. Effectively identifies background from sequencing and mapping biases [33].

Histone H3 immunoprecipitation: Specifically recommended for histone modifications; controls for nucleosome occupancy and antibody-specific backgrounds. Studies show H3 controls are more similar to histone modification ChIP-seq samples than WCE in features like mitochondrial coverage and behavior near transcription start sites [33].

IgG mock IP: Controls for non-specific antibody binding; can be used when studying non-histone chromatin proteins.

For histone modifications, Histone H3 immunoprecipitation generally provides the most appropriate background model, as it accounts for the underlying distribution of histones across the genome [33].

FAQ 5: How can I improve ChIP efficiency and specificity?

Problem: Low signal-to-noise ratio or high background

Possible causes and solutions:

- Antibody quality: Use ChIP-grade antibodies specifically validated for immunoprecipitation applications. Verify specificity through immunoblotting (should show single major band) or immunofluorescence showing expected nuclear pattern [1].

- Cross-linking issues: Over-cross-linking (>30 minutes) can mask epitopes and reduce IP efficiency. Optimize cross-linking time (typically 10-20 minutes for histones) and always use fresh formaldehyde [32] [1].

- Chromatin fragmentation: Either under-fragmentation or over-fragmentation can reduce resolution and efficiency. Optimize sonication conditions or MNase concentration for your specific cell or tissue type [31] [32].

- Cell lysis efficiency: Perform lysis at 4°C with fresh protease inhibitors to prevent degradation while maintaining protein integrity [32].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Comprehensive ChIP-seq Quality Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the critical quality control checkpoints throughout the ChIP-seq experimental pipeline, from sample preparation to data analysis:

Optimized Cross-Linking and Fragmentation Protocol

Materials Required:

- Fresh formaldehyde (1% final concentration)

- Glycine (125 mM stock for quenching)

- Lysis buffers with protease inhibitors

- Micrococcal nuclease (for enzymatic fragmentation) or sonication equipment

- Agarose gel equipment for size verification

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Cross-linking Optimization

Chromatin Fragmentation

Enzymatic Fragmentation (Micrococcal Nuclease):

- Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 125 mg tissue or 2×10⁷ cells.

- Set up digestion time course with varying MNase concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 μL of diluted enzyme).

- Incubate 20 minutes at 37°C with frequent mixing.

- Stop reaction with 10 μL 0.5 M EDTA.

- Determine optimal condition that produces 150-900 bp fragments [31].

Sonication-Based Fragmentation:

- Resuspend nuclear pellet in 1 ml ChIP Sonication Nuclear Lysis Buffer per 100-150 mg tissue or 1-2×10⁷ cells.

- Perform sonication time course, removing 50 μL samples after each 1-2 minutes of sonication.

- Analyze DNA fragment size by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Select conditions where ~90% of fragments are <1 kb for cells fixed 10 minutes [31].

Quality Assessment

Algorithm Selection for Peak Calling Based on Histone Mark Type

The decision workflow below guides researchers in selecting appropriate analysis strategies based on their histone mark of interest:

Table 4: Critical Reagents and Resources for Histone ChIP-seq Experiments

| Category | Item | Specification | Purpose | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Histone modification-specific | ChIP-grade validated | Target immunoprecipitation | Verify specificity by immunoblot (≥50% signal in main band) [1] |

| Controls | Histone H3 antibody | ChIP-grade | Background control for histone marks | Accounts for nucleosome occupancy [33] |

| Enzymes | Micrococcal nuclease | Molecular biology grade | Chromatin fragmentation | Titrate for 150-900 bp fragments [31] |

| Software | hiddenDomains | Latest version | Simultaneous broad/narrow peak calling | Sensitivity >62%, Specificity ~90% [27] |

| Software | MACS2 | Version 2.1.0+ | Flexible peak calling | Includes broad domain options [27] |

| Software | ChiLin | Pipeline | Comprehensive QC | Compares to 23,677 public datasets [30] |

| QC Metrics | FRiP | Sample-level metric | Enrichment assessment | >1% for broad marks, >5% for narrow marks [30] |

| QC Metrics | PBC | Library-level metric | Library complexity | >0.8 for high complexity [30] |

Proper categorization of histone marks into broad domains versus narrow peaks is not merely an analytical formality but a fundamental requirement for biologically meaningful ChIP-seq analysis. The distinction reflects essential differences in how these epigenetic marks function at the chromatin level, with narrow peaks typically marking precise regulatory elements and broad domains defining large-scale chromatin states. By implementing the troubleshooting guidelines, experimental protocols, and QC metrics outlined in this technical support center, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of their histone modification studies.

A robust quality control framework that accounts for these categorical differences—from experimental design through data analysis—ensures that resulting conclusions about gene regulatory mechanisms, epigenetic inheritance, and chromatin dynamics accurately reflect underlying biology. This approach is particularly crucial in therapeutic contexts, where epigenetic biomarkers and targets are increasingly important for diagnostic and drug development applications.

Implementing QC Pipelines: Practical Protocols and Analysis Workflows

What are the essential quality control steps in a histone ChIP-seq workflow?

A robust quality control (QC) workflow for histone ChIP-seq is critical for generating biologically meaningful data. The entire process, from raw sequencing reads to identified peaks (binding sites), involves multiple QC checkpoints to ensure data integrity. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and their logical relationship.

Workflow Overview and Key QC Checkpoints

What specific quality metrics should I check after read alignment and how do I interpret them?

After aligning your reads to a reference genome, several key metrics help assess the quality of your ChIP-seq experiment. The ENCODE consortium has established standards for interpreting these values [2] [34].

The table below summarizes the critical post-alignment QC metrics, their ideal values, and troubleshooting advice for out-of-range values.

| Metric | Description | Recommended Value | Troubleshooting Out-of-Range Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniquely Mapped Reads [35] [36] | Percentage of reads mapped to a single, unique location in the genome. | >50-70% for human genomes [35] [36]. | Low values may indicate poor library quality or a contaminated sample. |

| PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient (PBC) [2] [34] | Measures library complexity/skew. PBC = N1/Nd (N1=genomic locations with one read; Nd=distinct genomic locations). | PBC1 > 0.9 (No bottlenecking). 0.5-0.8 is moderate, 0-0.5 is severe bottlenecking [2] [34]. | Low values indicate over-amplification by PCR or insufficient starting material. |

| Normalized Strand Cross-correlation (NSC) [37] [34] | Ratio of maximal cross-correlation to background; measures signal-to-noise. | >1.1 (Low); >1.5 for broad histone marks [37]. Higher is better. | Values <1.1 indicate low signal-to-noise, potentially from poor enrichment or antibody. |

| Relative Strand Cross-correlation (RSC) [34] | Ratio of fragment-length cross-correlation to read-length phantom peak. | >1 (High quality); <1 may indicate low quality [34]. | Low RSC can result from poor enrichment, high background, or undersequencing. |

| Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) [2] | Proportion of all mapped reads that fall within called peak regions. | Varies by target. A higher score indicates better enrichment [2]. | A low score suggests poor antibody efficiency or weak ChIP enrichment. |

How much sequencing depth is required for my histone mark, and what are the consequences of undersequencing?

Sequencing depth requirements are strongly influenced by whether the histone mark produces broad domains (e.g., H3K27me3) or sharp, punctate peaks (e.g., H3K4me3). The ENCODE consortium provides clear guidelines [2].

The table below lists the recommended sequencing depths for various histone marks and the implications of insufficient depth.

| Histone Mark Type | Example Marks | ENCODE Recommended Depth (per replicate) | Risks of Undersequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Marks [2] | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me1, H3K79me2 | 45 million usable fragments [2]. | Incomplete domain detection, poor reproducibility, failure to identify biologically significant regions [34]. |

| Narrow Marks [2] | H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K4me2 | 20 million usable fragments [2]. | Missing weaker binding sites, reduced statistical power for peak calling, lower confidence in identified peaks [36]. |

| Exception (H3K9me3) [2] | H3K9me3 | 45 million total mapped reads. | This mark is enriched in repetitive regions, requiring more reads to confidently map signals in unique genomic regions [2]. |

My replicates show poor agreement. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

Poor reproducibility between biological replicates is a common challenge. The Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis is the gold standard for assessing replicate consistency [2] [34].

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Antibody Specificity: A primary cause of poor reproducibility is a non-specific or low-quality antibody [1]. The ENCODE consortium mandates rigorous antibody validation, including immunoblot or immunofluorescence, to ensure specificity for the target [2] [1].

- Variable IP Efficiency: Differences in chromatin shearing, immunoprecipitation time, or washing stringency between replicates can cause inconsistency [38]. Standardize protocols meticulously and use controls.

- Low Sequencing Depth: If replicates are undersequenced, the signal may be too weak to distinguish from noise, leading to poor overlap in peak calls [2] [36]. Ensure you meet the recommended sequencing depths.

- Analysis Pipeline Issues: Using inappropriate peak-calling parameters can cause problems. For broad histone marks like H3K27me3, ensure your peak caller (e.g., MACS2) is set to broad mode, as the statistical model differs from the default narrow mode [38].

My peak caller is producing inconsistent results. What should I check?

Inconsistent peak calling can stem from incorrect tool selection or parameter settings.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Tool Selection: Confirm you are using a peak caller suitable for histone data. MACS2 is a versatile and widely used option, but it must be run in

--broadmode for broad histone marks [38]. Other tools like SICER are also designed for broad domains [37]. - Check the Control/Input: Always use a matched input control (e.g., genomic input DNA) during peak calling to account for technical biases and open chromatin background [2] [36]. The control should be sequenced to a comparable depth as your ChIP sample.

- Inspect Signal Tracks Visually: "Peak calling is statistical, but interpretation is visual" [38]. Load your ChIP and control BAM files into a genome browser like IGV or UCSC Genome Browser. This allows you to visually confirm that called peaks correspond to genuine enrichment signals and are not artifacts [38] [35].

- Review QC Metrics First: Before adjusting peak-calling parameters, go back and check your alignment and enrichment metrics (e.g., NSC, RSC). Poor peak calling is often a symptom of underlying data quality issues, not a problem with the peak caller itself [38] [34].

- Verify Tool Selection: Confirm you are using a peak caller suitable for histone data. MACS2 is a versatile and widely used option, but it must be run in

| Category | Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Validated Antibody | The most critical reagent. Must be specifically validated for ChIP-seq applications to ensure it recognizes the intended histone modification with minimal cross-reactivity [2] [1]. |

| Input Control DNA | Chromatin that has been cross-linked and sheared but not immunoprecipitated. Serves as a crucial control for background noise and biases in sequencing and analysis [2] [36]. | |

| Software & Algorithms | Quality Control Tools | FastQC for initial read QC; samtools and sambamba for BAM file processing and filtering [37] [35]. |

| Alignment Tools | Bowtie2 or BWA for mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome quickly and accurately [39] [35] [36]. | |

| Peak Callers | MACS2 (use --broad flag for broad marks), HOMER, or SICER to identify statistically significant enriched regions [38] [37] [35]. |

|

| QC & Visualization | deepTools for advanced QC plots; IGV for essential visual inspection of called peaks against raw data tracks [38] [39]. | |

| Databases & Pipelines | ENCODE Guidelines & Pipelines | Provides the definitive standard for experimental protocols, data processing pipelines, and quality metric thresholds for ChIP-seq data [2]. |

| ChIP-Atlas | A public data-mining suite to explore and compare over 433,000 public ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and Bisulfite-seq experiments [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Library Quality Assessment

Q1: What are NRF and PBC, and why are they critical for my histone ChIP-seq experiment? NRF (Non-Redundant Fraction) and PBC (PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient) are fundamental metrics used to assess the complexity and quality of your ChIP-seq sequencing library. Library complexity indicates the diversity of unique DNA fragments in your library, which is crucial for achieving comprehensive genome coverage and avoiding biases from the over-amplification of a small number of fragments.

- NRF is calculated as the number of genomic locations with at least one read (unique locations) divided by the total number of uniquely mapped reads. A high NRF indicates a library with high complexity [30].

- PBC is calculated as the number of genomic locations with exactly one read divided by the number of unique locations (NRF denominator). This measures the evenness of coverage and the severity of amplification bottlenecks [2] [30].

The ENCODE consortium has established the following preferred standards for these metrics [2] [9]:

Table 1: Preferred ENCODE Standards for Library Complexity

| Metric | Full Name | Calculation | Preferred Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRF | Non-Redundant Fraction | Unique locations / Total mapped reads | > 0.9 [2] [9] |

| PBC | PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1 | Locations with 1 read / Unique locations | > 0.9 [2] [9] |

| PBC2 | PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 2 | Locations with 1 read / Locations with 2 reads | > 10 [2] [9] |

Q2: My PBC score is low. What does this mean, and how can I troubleshoot it? A low PBC score (e.g., PBC1 < 0.9) indicates a high rate of PCR duplication, meaning your library has low complexity. This is often referred to as a "bottlenecked" library, where a small number of original DNA fragments have been amplified many times, skewing your representation of the genome and reducing the effective sequencing depth [30].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize PCR Amplification: The most common cause is excessive PCR cycling during library preparation. Reduce the number of PCR cycles to the minimum necessary.

- Start with More Input Material: Low starting material can lead to over-amplification. Ensure you are using an adequate number of cells. For histone ChIP-seq, one million cells is often sufficient for abundant marks, while ten million may be required for others [10].

- Verify Fragmentation and Size Selection: Improper sonication or MNase digestion can reduce complexity. Ensure your chromatin is sheared to an optimal size of 150-300 bp and that size selection is performed correctly to remove very short or long fragments [10].

- Check the IP Efficiency: A weak immunoprecipitation that yields very little DNA will also require more amplification. Ensure your antibody is specific and your ChIP protocol is efficient [1] [10].

Q3: What mapping statistics should I look for, and what are the minimum thresholds? After sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome, mapping statistics help you understand the quality of the alignment and identify potential issues. Key metrics include the uniquely mapped reads and the unmapped or multi-mapped reads.

The ENCODE processing pipelines require reads to be a minimum of 50 base pairs, though longer reads are encouraged, and they must be mapped to a designated reference genome like GRCh38 or mm10 [2] [9]. While ENCODE does not specify a single universal threshold for uniquely mapped reads, a high percentage is critical. The ChiLin pipeline, for example, reports the "uniquely mapped ratio" (uniquely mapped reads divided by total reads) and compares it to a large historical database of public ChIP-seq samples to determine its percentile rank, providing context for your data's quality [30].

Q4: How much sequencing depth is required for histone ChIP-seq? The required sequencing depth depends on whether you are investigating a "broad" or "narrow" histone mark. The ENCODE consortium provides clear guidelines for the number of usable fragments per biological replicate [2] [9]:

Table 2: ENCODE Sequencing Depth Standards for Histone ChIP-seq

| Histone Mark Type | Examples | Minimum Usable Fragments per Replicate | Recommended Usable Fragments per Replicate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3 | 20 million [9] | 45 million [2] [9] |

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac | 10 million [9] | 20 million [2] [9] |

Note: H3K9me3 is a special case among broad marks because it is enriched in repetitive regions. For tissues and primary cells, ENCODE recommends 45 million total mapped reads per replicate for H3K9me3 [2] [9].

Q5: What tools are available to calculate these quality metrics? Several specialized software packages and pipelines can automatically calculate NRF, PBC, mapping statistics, and other QC metrics from your raw sequencing files.

- ChiLin: A comprehensive pipeline that automates QC and analysis for ChIP-seq data. It calculates NRF and PBC from a sub-sample of reads to allow comparison across samples with different sequencing depths and generates a comprehensive QC report [30].

- CHANCE: A user-friendly, graphical software that estimates immunoprecipitation strength, identifies biases (including PCR amplification), and compares your data's quality to a large collection of published ENCODE datasets [41].

- ENCODE Pipelines: The standardized histone ChIP-seq processing pipeline used by the ENCODE consortium collects key QC metrics, including library complexity (NRF, PBC), read depth, and FRiP score, as part of its output [2] [9].

Workflow for Library Quality Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing library quality, from raw data to final interpretation, integrating the key metrics discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone ChIP-seq Quality Control

| Item | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Protein-specific reagents for immunoprecipitation. | Must be characterized for ChIP-seq. ENCODE requires primary (e.g., immunoblot showing a single major band) and secondary tests for specificity [1] [10]. |

| Input Control DNA | Chromatin taken before IP; used as a control for background signal. | Essential for accurate peak calling. Must come from the same cell type and have matching replicate structure and sequencing depth as the IP sample [2] [9] [42]. |

| PCR Reagents | Enzymes and master mixes for library amplification. | Use high-fidelity polymerases and minimize the number of amplification cycles to preserve library complexity and avoid bottlenecks (low PBC) [10] [30]. |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Enzymes (e.g., MNase) or equipment (sonicator) for DNA fragmentation. | Method impacts data. MNase is good for histone marks but can degrade transcription factor binding sites. Sonication of cross-linked chromatin is widely applicable. Optimize for fragment size of 150-300 bp [10] [43]. |

| QC Analysis Software | Tools like ChiLin [30] and CHANCE [41]. | Automate the calculation of NRF, PBC, FRiP, and other metrics. Provide a benchmark against historical data for objective quality assessment. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the FRiP score, and why is it critical for histone ChIP-seq quality control?

The FRiP score, or Fraction of Reads in Peaks, is a primary metric used to assess the signal-to-noise ratio in a ChIP-seq experiment. It calculates the proportion of all sequenced reads that fall within the identified peak regions, thereby indicating the success of the immunoprecipitation step. A higher FRiP score signifies a greater level of specific enrichment over background noise.

For histone ChIP-seq data, which is a key focus of your research, this metric is crucial because it helps determine if the experiment has sufficient enrichment to reliably identify regions bound by histones or specific histone modifications. It serves as a key quality indicator before proceeding with more complex analyses, such as chromatin segmentation models [2].

How do I calculate the FRiP score?

The FRiP score is calculated using a straightforward formula after you have generated your initial set of peak calls.

FRiP = (Number of reads falling within peaks) / (Total number of mapped reads)

The following workflow outlines the general process for obtaining the data needed for this calculation:

In practice, this calculation is often performed automatically by quality control tools like ChIPQC in Bioconductor, which takes the BAM file (aligned reads) and the BED file (called peaks) as input and computes the FRiP score along with other QC metrics [44].

What is considered a good FRiP score for my histone ChIP-seq experiment?

The expected FRiP score varies significantly depending on the genomic feature being studied. Histone marks generally produce a mix of broad and narrow peaks and typically yield higher FRiP scores than transcription factors. The ENCODE consortium guidelines provide a framework for expectations.

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for FRiP Scores

| Target Type | Typical Peak Profile | Expected FRiP Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor | Sharp / Narrow | ~5% or higher [44] | A good quality TF with successful enrichment. |

| Histone Mark (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac) | Mixed (Sharp & Broad) | Can be 30% or higher [44] | Represents a good quality mark like Pol II. |

| Broad Histone Mark (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K36me3) | Broad / Dispersed | Higher than sharp marks [45] | Can spread over large genomic regions. |

It is critical to note that these are guidelines, not absolute thresholds. The ENCODE consortium emphasizes that there are known examples of high-quality datasets with FRiP scores below 1% (e.g., for a protein that binds very few sites) [44]. The score should be evaluated in the context of other QC metrics, such as library complexity and replicate concordance.

My FRiP score is low. What are the potential causes and solutions?

A low FRiP score indicates a high level of background noise and poor immunoprecipitation efficiency. The following troubleshooting table outlines common causes and recommended solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Low FRiP Scores

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody & IP | Non-specific or low-quality antibody; inefficient IP. | Use ChIP-grade antibodies validated by immunoblot or immunofluorescence [1]. Perform a primary characterization to ensure the main reactive band contains at least 50% of the signal on a blot [1]. |

| Chromatin Preparation | Over- or under-fragmentation of chromatin; suboptimal cross-linking. | Optimize sonication or enzymatic digestion (e.g., Micrococcal Nuclease) to achieve a fragment size of 150–900 bp [46]. Avoid over-sonication, which can damage chromatin. Optimize cross-linking time (typically 10-20 min) [47]. |

| Experimental Design | Insufficient sequencing depth; lack of biological replicates. | Follow ENCODE sequencing depth standards: 45 million usable fragments per replicate for broad histone marks and 20 million for narrow histone marks (exceptions like H3K9me3 exist) [2]. Include two or more biological replicates. |

| Input Material | Low amount of starting chromatin. | Ensure you are using the recommended amount of chromatin per IP (e.g., 5–10 µg). Note that chromatin yield varies by tissue type (e.g., brain tissue yields much less than spleen) [46]. |

| Background Noise | High reads in blacklisted regions. | Check the RiBL (Reads in Blacklisted Regions) metric. A high RiBL percentage indicates artifactual signal. Use tools like ChIPQC to calculate this [44]. |

How does the FRiP score relate to other ChIP-seq quality control metrics?

The FRiP score is most powerful when used as part of a holistic quality assessment. The ENCODE consortium recommends evaluating it alongside other metrics:

- Library Complexity: Measured by the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 & PBC2). Preferred values are NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 [2] [13].

- Replicate Concordance: For transcription factors, this is measured using the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR). For histone marks with broad peaks, replicated peaks are identified through overlap between biological replicates or pseudoreplicates [2] [13].

- SSD (Standard Deviation of Signal Pile-up): Measures the uniformity of coverage. A higher SSD indicates more regional enrichment, which is expected for a good ChIP sample, while a lower SSD is typical for input controls [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for a successful histone ChIP-seq experiment, as referenced in the guidelines and protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone ChIP-seq

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-grade Antibody | Binds specifically to the target histone or histone modification for immunoprecipitation. | Must be specifically validated for ChIP [1] [48]. Check for characterization data (e.g., immunoblot showing a single dominant band) [1]. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase support for capturing antibody-target complexes. | Choose Protein A or G based on the species and isotype of your antibody for optimal binding affinity [47]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzyme for digesting chromatin into smaller fragments (enzymatic shearing). | The optimal amount must be determined empirically for each cell/tissue type via a digestion test [46]. |

| Sonicator | Instrument for fragmenting cross-linked chromatin via physical shearing (sonication). | Optimal conditions (power, duration, cycles) must be determined via a time-course experiment to achieve 150-900 bp fragments [46]. |

| Formaldehyde | Reagent for cross-linking proteins to DNA in living cells. | Use a final concentration of 1% and a cross-linking time of 10-20 minutes at room temperature. Quench with glycine [47]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent degradation of proteins and histones during the isolation process. | Add to lysis buffers immediately before use. For histone ChIPs, consider adding sodium butyrate (NaB) [47]. |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors | For certain marks like acetylated histones, it prevents the removal of the modification during the procedure. | Trichostatin A (TSA) or Sodium Butyrate (NaB) can be added, though systematic improvement for CUT&Tag has not been consistently observed [48]. |

FAQs: Understanding Peak Shape and Biological Meaning

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between broad and narrow histone marks?

The difference lies in their genomic distribution and biological function. Narrow marks (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3) produce sharp, focal peaks typically at active promoters and enhancers, spanning a few hundred to a few thousand base pairs. Broad marks (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K36me3) form wide enrichment domains that can spread across large genomic regions, such as repressed domains or actively transcribed gene bodies, often covering tens to hundreds of kilobases [49] [45]. This distinction is critical because peak-calling algorithms developed for narrow peaks often fragment or completely miss these broad domains [5].

Q2: Why can't I use the same peak caller and settings for all my histone ChIP-seq data?

Using a one-size-fits-all approach, particularly a peak caller optimized for transcription factors, is a common mistake that severely distorts biological interpretation [5]. The underlying algorithms for identifying significant regions are tuned for different signal shapes. For instance, applying a narrow peak caller like MACS2 with default settings to a broad mark like H3K27me3 will report hundreds of fragmented, sharp peaks instead of continuous broad domains, leading to a complete misrepresentation of the underlying biology [5] [45]. The choice of tool must be matched to the expected peak shape of the histone mark.

Q3: My broad mark analysis shows fragmented peaks. What went wrong?

Fragmentation of broad domains is typically caused by using a peak-calling method designed for narrow peaks. This occurs when tools search for localized, high-intensity signals and fail to merge adjacent regions of lower but significant enrichment into a single, continuous domain [49] [5]. To correct this, you must switch to a peak caller specifically designed for broad domains, such as SICER2 or MACS2 in broad mode, which use sliding windows or spatial clustering to identify larger enriched regions [45] [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Biological Replicates

Possible Causes & Recommendations:

- Cause: Inadequate Quality Control (QC) Metrics. Relying only on basic FastQC reports while ignoring ChIP-specific QC metrics.

- Recommendation: Implement a rigorous QC pipeline. Calculate the Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP), which should typically be >1% for histone marks. Use tools like

PhantomPeakToolsto compute normalized strand cross-correlation (NSC) and relative strand correlation (RSC). Per ENCODE guidelines, an RSC > 1 is indicative of a successful experiment, while RSC < 0.5 suggests no significant enrichment [5]. Always analyze replicates separately before merging to assess concordance. - Cause: Low Sequencing Depth or Poor Library Complexity. Broad marks require sufficient sequencing depth to cover large domains consistently.

- Recommendation: Ensure adequate sequencing depth. While guidelines vary, broad marks often require more reads than narrow marks to map their entire domain reliably. Check library complexity metrics and be wary of high duplication rates that can indicate issues [5].

Problem: Excessive Background Noise or False Positive Peaks

Possible Causes & Recommendations:

- Cause: Failure to Use or Misuse of Control Datasets. Using a low-quality input DNA, an inappropriate control (e.g., IgG for some marks), or no control at all.

- Recommendation: Always use a properly sequenced input DNA control. The input should have a read depth at least equal to, and ideally double, that of your ChIP samples. This control accounts for background noise from technical artifacts like open chromatin and GC bias [5].

- Cause: Peaks in Artifact-Prone Genomic Regions. Many peaks fall into known problematic regions like satellite repeats, telomeres, and centromeres.

- Recommendation: Filter your peak calls using the ENCODE blacklist, which is a curated list of artifact-prone regions for common model organism genomes. This simple step removes obvious false positives [5].

Problem: Inability to Detect Broad, Low-Enrichment Domains

Possible Causes & Recommendations:

- Cause: Suboptimal Peak Caller Selection and Parameters. Using a narrow peak caller or a broad peak caller with overly stringent thresholds.

- Recommendation: Use a tool designed for broad marks. For MACS2, explicitly use the

--broadflag and a more lenient--broad-cutoff(e.g., 0.1). Alternatively, use dedicated tools like SICER2, which is specifically designed to identify spatially clustered signals that characterize broad marks [5] [45]. - Cause: Global Background Normalization Issues. Some differential analysis tools assume most genomic regions do not change, which is invalid in experiments causing global loss of a mark (e.g., inhibitor treatment).

- Recommendation: For differential analysis of broad marks, select a tool robust to global changes. A comprehensive benchmark study recommends tools like

bdgdiff(MACS2),MEDIPS, andPePrfor their strong performance across various scenarios [45].

Peak Caller Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes recommended tools and key considerations for different histone mark categories.

Table 1: Peak Calling Strategy Selection Guide

| Histone Mark Type | Example Marks | Recommended Peak Callers | Critical Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K9ac | MACS2 (narrow mode), HOMER | Use default or stringent q-value (e.g., 0.01). Good for focal, high-intensity signals [45] [51]. |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3 | SICER2, MACS2 (--broad), SEACR (for CUT&RUN) |

Use larger window sizes (SICER2) and lenient cutoffs. Designed for wide, low-enrichment domains [45] [52]. |

| Mixed or Unknown | H3K4me1, H3K79me2 | MACS2 (broad and narrow), HOMER | May require testing both modes and validating against known biology [53]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimization of Chromatin Fragmentation

A critical wet-lab step that influences peak calling is chromatin fragmentation. The following protocol, adapted from standard troubleshooting guides, ensures optimal DNA fragment size [54].

Objective: To determine the ideal micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion or sonication conditions for generating DNA fragments primarily between 150–900 bp.

Materials:

- Cross-linked nuclei from your tissue or cell type of interest.

- Micrococcal nuclease (for enzymatic digestion) or a sonicator (for sonication protocol).

- 1X Buffer B + DTT, 0.5 M EDTA, 1X ChIP buffer + Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (PIC).

- RNAse A, Proteinase K, and standard materials for agarose gel electrophoresis.

Method for Enzymatic Digestion (Optimizing MNase Concentration):

- Prepare Nuclei: Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 125 mg of tissue or 2 x 10^7 cells.

- Set Up Digestions: Aliquot 100 µl of nuclei preparation into five separate tubes.

- Dilute Enzyme: Prepare a 1:10 dilution of MNase stock in 1X Buffer B + DTT.

- Titrate Enzyme: Add different volumes (e.g., 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 µl) of the diluted MNase to each tube. Mix and incubate for 20 minutes at 37°C.

- Stop Reaction: Add 10 µl of 0.5 M EDTA to each tube and place on ice.

- Purify DNA: Pellet nuclei, resuspend in ChIP buffer, and lyse with brief sonication or homogenization. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation.

- Reverse Cross-Links & Analyze: Treat the supernatant with RNAse A and Proteinase K to isolate DNA. Run 20 µl of each sample on a 1% agarose gel.

- Determine Optimal Condition: Identify the MNase volume that produces a DNA smear in the desired 150–900 bp range. Scale this volume down for a single IP preparation.

Diagram: Workflow for Optimizing Chromatin Fragmentation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions