Evaluating Protein Structure Prediction Tools: A 2025 Guide to Accuracy, Applications, and Validation

Accurate protein structure prediction is now indispensable for drug discovery and functional analysis.

Evaluating Protein Structure Prediction Tools: A 2025 Guide to Accuracy, Applications, and Validation

Abstract

Accurate protein structure prediction is now indispensable for drug discovery and functional analysis. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate the accuracy of modern prediction tools. It covers foundational concepts, explores the methodologies behind leading AI-driven tools like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, addresses current challenges and optimization strategies, and presents rigorous validation and comparative benchmarking techniques based on community standards like CASP and emerging benchmarks such as DisProtBench.

The Foundations of Protein Structure Prediction: From Anfinsen's Dogma to AI Revolution

The central challenge in structural biology is accurately predicting the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a protein from its one-dimensional amino acid sequence. This is known as the sequence-structure gap. Although the underlying principle—that a protein's sequence uniquely determines its structure—has been understood for decades, the computational prediction of this structure has remained a formidable scientific problem [1]. The ability to bridge this gap is crucial for advancing molecular biology, understanding disease mechanisms, and accelerating rational drug design.

For years, experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have been the primary methods for determining protein structures. However, these methods are often time-consuming, expensive, and technically demanding [2] [3]. The rapid growth in protein sequence data, fueled by genomic sequencing technologies, has vastly outpaced the rate of experimental structure determination, making computational prediction an essential tool for keeping pace with biological discovery.

A Comparative Guide to Modern Prediction Tools

The field of protein structure prediction has been revolutionized recently, particularly by deep learning methods. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the leading tools, their core methodologies, and key capabilities.

Table 1: Overview of Leading Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Key Capabilities | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2 & 3 [2] [4] | Deep Learning (Evoformer & Diffusion networks) | Predicts single-chain proteins, protein complexes, protein-ligand, and protein-nucleic acid structures. | Predicting structures for entire proteomes; high-accuracy single-domain models [5]. |

| TASSER_2.0 [6] | Threading & Fragment Assembly | Refines template structures using predicted side-chain contacts for weakly homologous targets. | Modeling proteins with weak or no homology to known structures (Hard targets) [6]. |

| ClusPro [7] | Integration of Machine Learning & Physics-Based Docking | Specializes in predicting protein multimers (complexes) and protein-ligand interactions. | Antibody-antigen complexes; protein-ligand docking [7]. |

| Subsampled AlphaFold2 [2] | Deep Learning with Modified MSA Input | Predicts conformational distributions and relative state populations of proteins. | Studying protein dynamics and the effect of point mutations on conformation [2]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking at CASP16

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biennial community-wide experiment that provides the most rigorous independent assessment of protein structure modeling methods. The most recent assessment, CASP16, was conducted in 2024 and evaluated tens of thousands of models submitted by approximately 100 research groups worldwide [5]. The results provide a clear, quantitative measure of the current state of the art.

Table 2: Performance of Select Tools in CASP16 (2024) Assessment Categories

| Prediction Category | Exemplary Tool / Team | Key Performance Metric | Interpretation & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Multimers (Complexes) | Kozakov/Vajda Team (ClusPro) [7] | Substantially outperformed other participants in accuracy. | Demonstrated particular strength in challenging antibody-antigen complexes, an area where generic AlphaFold models perform relatively poorly. |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Kozakov/Vajda Team (ClusPro) [7] | Attained the highest accuracy among all participants. | Efficient conformational sampling and integration of physics-based scoring were key differentiators. |

| Single Proteins & Domains | AlphaFold-based methods [5] | Many models are competitive in accuracy with experiment. | The focus has shifted to fine-grained accuracy, inter-domain relationships, and the performance of new deep learning/Language Models. |

| Nucleic Acids & Complexes | Traditional Methods [5] | Outperformed deep learning methods in CASP15 (2022). | CASP16 was set to determine if deep learning had closed this performance gap for RNA/DNA structures. |

| Macromolecular Conformational Ensembles | Various [5] | Category assessed for the first time in CASP15. | Aims to evaluate methods for predicting multiple conformations and alternative states of proteins. |

Experimental Protocols for Tool Validation

The high-level performance metrics shown in CASP are derived from rigorous, standardized experimental protocols. Understanding these methodologies is essential for interpreting the data.

The CASP Evaluation Workflow

The CASP experiment follows a strict double-blind protocol to ensure a fair and objective assessment of all participating methods [5].

Key Steps in the Protocol:

- Target Release: Organizers release the amino acid sequences of proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but are not yet publicly available [5].

- Model Submission: Participating research groups worldwide submit their predicted 3D models for these target sequences over a several-month "modeling season." In CASP16, over 80,000 models were submitted [5].

- Independent Assessment: Once the modeling season concludes, independent assessors compare the predicted models to the newly released experimental coordinates using established and novel metrics [5].

- Metrics for Success:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between equivalent atoms in the predicted and native structure after optimal superposition. A lower RMSD indicates higher accuracy.

- Global Distance Test (GDTTS): A more robust metric that measures the percentage of amino acid residues that can be superimposed under a certain distance cutoff. A higher GDTTS indicates higher accuracy.

- Success Rate: A prediction is often deemed successful if the model has an RMSD to the native structure of less than 6.5 Å, particularly for more difficult targets [6].

Protocol for Predicting Conformational Distributions

A key limitation of many structure prediction tools is their focus on a single, static structure. However, proteins are dynamic and exist as an ensemble of conformations. A novel methodology using a subsampled AlphaFold2 approach was developed to address this, with its experimental protocol outlined below [2].

Key Steps in the Protocol:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Compilation: A large MSA is compiled for the protein of interest using tools like JackHMMR [2].

- MSA Subsampling: Instead of using the full MSA, AlphaFold2 is run multiple times with randomly subsampled MSAs. This is controlled by parameters like

max_seqandextra_seq, which are significantly lowered from their default values to disrupt the consensus evolutionary signal and promote conformational diversity [2]. - Ensemble Generation: Dozens to hundreds of independent predictions are run. Each prediction, due to the subsampled MSA and enabled dropout, samples a different part of the protein's conformational landscape [2].

- Validation: The resulting ensemble of structures is validated against experimental data. For example, in the case of the Abl1 kinase, predictions were compared to conformational states observed in enhanced sampling molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The accuracy of predicting population shifts due to mutations was validated against experimental data, achieving over 80% accuracy [2].

Successful protein structure prediction and analysis rely on a suite of databases, software, and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to the Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6] | Database | Central repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. | The primary source of "ground truth" data for training AI models, benchmarking predictions, and performing comparative modeling. |

| AlphaFold DB [7] | Database | Repository of over 200 million pre-computed protein structure predictions generated by AlphaFold. | Allows researchers to instantly access predicted structures for most known proteins without running computations. |

| SAbDab [8] | Specialized Database | Database of all antibody structures from the PDB, consistently annotated with curated affinity data and sequence information. | An invaluable resource for studying and predicting antibody structures, a particularly challenging class of proteins. |

| CASP/CAPRI [5] [7] | Community Experiment | The gold-standard benchmarking platform for objectively assessing the accuracy of new protein (CASP) and complex (CAPRI) prediction methods. | Provides unbiased, rigorous performance data that drives methodological innovation and allows for direct tool comparison. |

| ClusPro Server [7] | Web Server | A widely used, publicly available server for predicting protein-protein interactions and protein-ligand complexes. | Makes state-of-the-art docking and complex prediction accessible to nearly 40,000 users without requiring local computational expertise. |

The field of protein structure prediction has made monumental strides in recent years, effectively narrowing the sequence-structure gap for single-domain proteins. Tools like AlphaFold 2 and 3 have demonstrated accuracies competitive with experimental methods for many targets. However, as the rigorous assessments of CASP16 show, significant challenges remain, particularly in the areas of protein dynamics, multimetric assemblies, and interactions with nucleic acids and small molecules [5] [2].

The future of the field lies in the intelligent integration of different methodological strengths. As demonstrated by the top performers in CASP16, combining the pattern recognition power of deep learning with the principled sampling of physics-based models and experimental data provides a robust path forward [7]. This hybrid approach will be crucial for moving beyond static structures to model the conformational ensembles that underpin protein function, ultimately providing a more complete and dynamic picture of the molecular machinery of life.

The journey of protein structure prediction is built upon a foundational principle known as Anfinsen's dogma. In 1961, American biochemist Christian Anfinsen demonstrated through experiments with the enzyme RNase that certain chemicals could cause it to lose its structure and biological activity, but upon removal of these chemicals, the denatured RNase would restore its original state [9]. This led to his Nobel Prize-winning hypothesis that under appropriate conditions, a protein's amino acid sequence uniquely determines its three-dimensional structure, which represents the molecule's lowest free-energy state [9] [10].

This principle established the theoretical possibility of predicting protein structure from sequence alone, suggesting that the three-dimensional information of proteins is entirely encoded in their amino acid sequences [9]. For over half a century, this hypothesis has driven computational biology, though researchers immediately confronted Levinthal's paradox, which highlighted the astronomical number of possible conformations a protein chain could theoretically adopt, making brute-force computation impractical [10]. This review traces the historical evolution of computational methods from early physical principles to the deep learning revolution, evaluating their accuracy through community-wide assessments and providing researchers with objective comparisons of modern prediction tools.

The Pre-AI Era: Traditional Computational Methods

Before the advent of artificial intelligence, protein structure prediction relied on three primary computational approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Traditional Protein Structure Prediction Methods before Deep Learning

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | Uses known structures of homologous proteins as templates | High accuracy when suitable templates available; Widely accessible | Template-dependent; Poor for unique proteins without close relatives | Swiss-Model, Modeller, Phyre2 [11] |

| Ab Initio Modeling | Predicts structure from physical principles without templates | Template-free; Can explore novel folds | Computationally intensive; Accuracy depends on energy functions | Rosetta, QUARK, I-TASSER [11] |

| Protein Threading | Threads sequence through library of known folds | Can predict structures with limited sequence similarity | Computationally demanding; Relies on template compatibility | I-TASSER, HHpred, Phyre2 [11] |

Early methods like the Chou-Fasman method in the 1970s calculated the probability of each amino acid appearing in secondary structure elements like α-helices and β-sheets, but achieved only about 50% accuracy as they ignored interactions between distant amino acids [9]. The GOR method improved upon this by considering the effects of neighboring amino acids, yet still remained limited to 65% accuracy [9].

The introduction of neural networks through the PHD algorithm in the 1990s represented a significant step forward by incorporating homologous sequences and physicochemical properties into a three-layer backpropagation network [9]. However, these early neural approaches still struggled with global information and achieved accuracies around 70%, insufficient for reliable tertiary structure prediction [9].

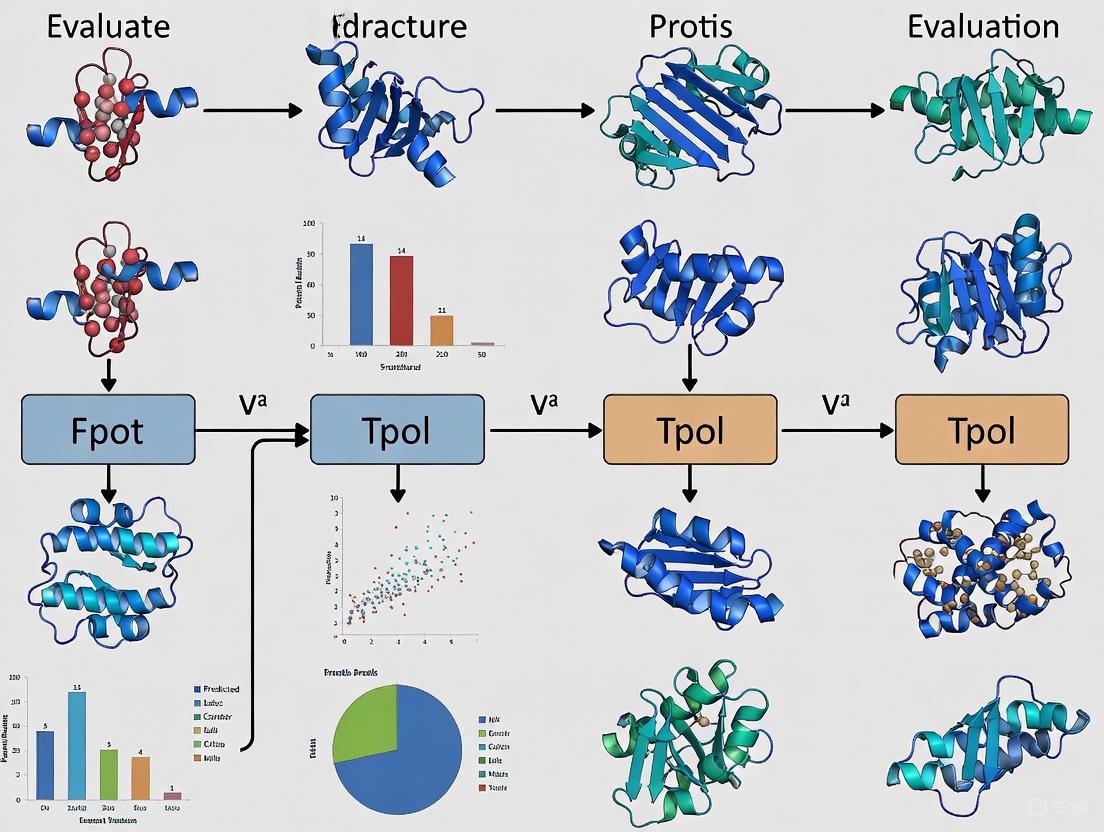

Diagram 1: Traditional protein structure prediction approaches and their limitations

The Deep Learning Revolution

Early Breakthroughs: The First Reliable AI

The significant breakthrough in computational protein structure prediction came with the development of RaptorX by Jinbo Xu in 2016, which represented the first reliable artificial intelligence for this task [9]. Previous methods had struggled with accuracy rates around 70%, but RaptorX introduced a critical innovation: the use of global information throughout the entire amino acid sequence rather than just local context [9].

The key technical advancement was RaptorX's use of a deep residual neural network to calculate contact maps - matrices representing the distance between every pair of amino acids in a sequence [9]. By summarizing all positional information into a matrix and processing it through a specially designed 60-layer neural network, RaptorX could predict the structure of challenging membrane proteins with an error of only 0.2 nanometers (approximately the width of two atoms), even without training on similar structures from the Protein Data Bank [9]. This demonstrated that deep learning could capture fundamental folding principles rather than merely memorizing existing structural templates.

AlphaFold: A Paradigm Shift

The field experienced a seismic shift with Google DeepMind's introduction of AlphaFold in 2018 and its completely redesigned successor AlphaFold2 in 2020 [12]. AlphaFold2 dominated the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) in 2020, achieving median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (r.m.s.d.95) compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method [12]. For context, the width of a carbon atom is approximately 1.4 Å, making AlphaFold2's predictions competitive with experimental methods in most cases [12].

AlphaFold2's architecture represented a fundamental departure from previous approaches through several key innovations:

- Evoformer Blocks: A novel neural network component that processes both multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and pairwise features through attention mechanisms, enabling reasoning about spatial and evolutionary relationships [12]

- End-to-End Structure Prediction: Direct prediction of 3D coordinates for all heavy atoms using a structure module that introduces explicit 3D structure in the form of rotations and translations for each residue [12]

- Iterative Refinement: Recycling outputs back into the same modules to progressively refine predictions, significantly enhancing accuracy [12]

The AlphaFold system demonstrated particular strength with challenging protein classes including membrane-bound proteins, fusion proteins, cytosolic domains, and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [13]. Its accuracy was validated not only in CASP competitions but also against recently released PDB structures, confirming real-world applicability [12].

Experimental Validation: Protocols and Metrics

Community-Wide Assessment (CASP)

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) has served as the gold-standard blind test for evaluating prediction methods since 1994 [14] [12]. Conducted biennially, CASP provides participants with amino acid sequences of recently solved but unpublished structures, allowing objective comparison of methods before experimental results become public [12].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Prediction Accuracy in CASP

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Threshold for High Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS (Global Distance Test Total Score) | Percentage of Cα atoms within certain distance thresholds after optimal superposition | Measures global fold correctness; higher values indicate better accuracy | >90% considered competitive with experimental methods [11] |

| TM-score (Template Modeling Score) | Scale-independent measure for comparing structural similarity | Values 0-1; >0.5 indicates correct fold, >0.8 high accuracy | >0.8 considered high accuracy [11] |

| lDDT (local Distance Difference Test) | Local consistency measure evaluating distance differences in predicted structures | Assesses local quality without global superposition; values 0-100 | >80 considered high quality [11] |

| RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | Standard measure of atomic distances between predicted and experimental structures | Lower values indicate better accuracy; sensitive to domain shifts | <1.0Å for backbone atoms considered atomic accuracy [9] |

The CASP14 results in 2020 demonstrated that AlphaFold2 achieved a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD, vastly outperforming the next best method at 2.8 Å RMSD [12]. Its all-atom accuracy was 1.5 Å RMSD compared to 3.5 Å for the best alternative method [12]. In the most recent CASP16 assessment (2024), deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, continued to dominate, with the protein domain folding problem now considered largely solved [15].

Continuous Automated Evaluation (CAMEO)

Complementing the biennial CASP experiments, the Continuous Automated Model EvaluatiOn (CAMEO) platform provides weekly assessments of prediction servers using the latest PDB structures [11]. This allows for ongoing monitoring of method performance in real-time and ensures that accuracy claims are validated against independent test sets.

Comparative Analysis of Modern Prediction Tools

Performance Comparison

The current landscape of protein structure prediction tools is dominated by AI-based approaches, though traditional methods remain relevant for specific applications.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Modern Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool | Core Methodology | Key Advantages | Reported Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3 | Deep learning with Evoformer and end-to-end structure module | Unprecedented accuracy for single-chain proteins; Fast prediction (hours) | Median backbone accuracy: 0.96Å RMSD; 2.65x more accurate than next best in CASP14 [13] [12] | Initially limited for complexes; Updated in AlphaFold3 [16] |

| RoseTTAFold | Deep learning with three-track architecture | Good accuracy; More accessible to academic community | Lower accuracy than AlphaFold2 but competitive with earlier methods [11] | Less accurate than AlphaFold2 [11] |

| NovaFold AI | Commercial implementation of AlphaFold2 | User-friendly interface; Specialized for membrane proteins, GPCRs, multi-domain proteins | Accuracy equivalent to AlphaFold2; Validated on difficult targets [13] | Commercial license required [13] |

| I-TASSER | Hierarchical approach combining threading and ab initio | Proven track record; Good for template-free modeling | Consistently top performer in earlier CASP experiments [11] | Less accurate than deep learning methods [11] |

| Swiss-Model | Homology modeling | Reliability when templates available; User-friendly web interface | High accuracy when sequence identity >30% [11] | Template-dependent; Limited for novel folds [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids | Public [11] |

| UniProt | Database | Comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information | Public [11] |

| SWISS-MODEL Template Library | Database | Over 1 million curated protein structures for homology modeling | Public [11] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Pre-computed AlphaFold predictions for over 200 million sequences | Public [16] |

| NovaCloud Services | Software Platform | Commercial interface for AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold-Multimer predictions | Subscription [13] |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Macromolecular modeling for protein design and structure prediction | Academic licensing [11] |

Current State and Future Perspectives

Solved Challenges and Persistent Limitations

As of CASP16 (2024), the protein single-domain folding problem is considered largely solved [15]. Deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold2 and its successors, can regularly predict structures with accuracy competitive with experimental methods for most single-domain proteins [12] [15].

However, significant challenges remain in several areas:

- Protein Complexes: Predicting structures of multi-chain protein complexes remains challenging, though AlphaFold-Multimer has shown promising results as a foundational approach [13] [16]

- Dynamic Behavior: Current methods predict static structures, while understanding protein dynamics, conformational changes, and folding pathways remains an open frontier [11]

- Conditional Effects: Most tools predict structures under standard conditions, while in vivo folding influenced by cellular environment presents additional complexity [11]

- Membrane Proteins: Though improved, accurate prediction of complex membrane protein structures continues to be refined [13]

Diagram 2: Modern deep learning workflow for protein structure prediction

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its trajectory as we look toward 2025 and beyond:

- Integration with Experimental Data: Methods like GRASP are emerging that integrate AI predictions with experimental restraints from diverse techniques for more reliable complex prediction [16]

- Extended Biomolecular Prediction: Recent advances focus on predicting not just proteins but complexes involving nucleic acids, small molecules, and post-translational modifications [15]

- Generative Protein Design: Frameworks like Anfinsen Goes Neural (AGN) are leveraging pre-trained protein language models and Anfinsen's dogma for conditional antibody design, demonstrating the inversion of structure prediction into protein design [17]

- Accessibility and Implementation: Cloud-based services and user-friendly interfaces are making advanced prediction tools accessible to broader research communities [13]

The journey from Anfinsen's dogma to modern deep learning represents one of the most significant transformations in computational biology. What began as a theoretical principle - that a protein's sequence determines its structure - has been actualized through increasingly sophisticated computational methods, culminating in AI systems that can predict protein structures with experimental accuracy.

While challenges remain, particularly for complexes and dynamic processes, the core problem of single-domain protein structure prediction has been largely solved through deep learning approaches. The field now shifts toward more complex challenges, including protein design, interaction prediction, and understanding dynamic conformational changes. As these tools become more accessible and integrated with experimental methods, they continue to transform structural biology, drug discovery, and our fundamental understanding of life's molecular machinery.

The three-dimensional structure of a protein is a critical determinant of its biological function, facilitating a mechanistic understanding of processes ranging from enzymatic catalysis to immune protection [18] [19]. The ability to predict this structure from an amino acid sequence alone has been one of the most important open problems in computational biology for over 50 years [12]. The vast gap between the hundreds of millions of known protein sequences and the approximately two hundred thousand experimentally determined structures has intensified the need for reliable computational prediction methods [18] [19]. These computational approaches are broadly categorized into two distinct paradigms: Template-Based Modeling (TBM) and Free Modeling (FM), also known as Template-Free Modeling. TBM relies on detecting structural homologs in existing databases, whereas FM predicts structure without such templates, using principles of physics, evolutionary patterns, or deep learning. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two key paradigms, evaluating their performance, underlying methodologies, and suitability for various applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Methodological Foundations

The fundamental difference between the two paradigms lies in their use of existing structural knowledge. The following workflows illustrate the distinct steps involved in each approach.

Template-Based Modeling (TBM) Workflow

Figure 1: The Template-Based Modeling (TBM) workflow involves identifying a structural template, aligning the target sequence to it, and building a model based on that alignment.

Template-Based Modeling (TBM) operates on the principle that evolutionarily related proteins share similar structures [18] [20]. When a protein with a known structure (a template) shares significant sequence similarity with the target protein, its structure can be used as a scaffold. The TBM process, as illustrated in Figure 1, involves several key steps. First, the target sequence is used to search a database of known structures (e.g., the Protein Data Bank, PDB) to identify potential templates using tools like PSI-BLAST or profile-based methods [21] [22]. Next, a sequence-structure alignment is generated, establishing a correspondence between each residue in the target sequence and a residue in the template structure. Finally, a 3D model is constructed by copying the coordinates of aligned regions from the template and modeling any unaligned regions (like loops) de novo, followed by energy minimization and refinement [18] [22]. TBM can be subdivided into homology modeling (for clear evolutionary relationships) and threading or fold recognition (for detecting structural similarity even with low sequence identity) [18] [20].

Free Modeling (FM) Workflow

Figure 2: The Free Modeling (FM) workflow predicts structure without a template, often by extracting constraints from evolutionary data and physical principles.

Free Modeling (FM) is employed when no suitable structural templates can be found, necessitating a prediction from first principles or evolutionary patterns [19] [20]. As shown in Figure 2, its methodology is fundamentally different. Early FM approaches, often called ab initio methods, were grounded in Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis, which states that a protein's native structure corresponds to its global free energy minimum [18] [20]. These methods involved computationally expensive conformational sampling to find this minimum. Modern FM, revolutionized by deep learning, instead uses patterns in evolutionary couplings and multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to infer spatial constraints [19] [12]. Programs like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold employ sophisticated neural networks to process MSAs and predict atomic coordinates or inter-residue distances, effectively learning the mapping from sequence to structure [12]. While some modern FM tools may use structural databases for training, they do not rely on explicit template search during prediction [18].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The choice between TBM and FM is largely dictated by the availability of structural templates, which in turn directly determines the achievable accuracy. The following table summarizes the typical performance characteristics of each paradigm.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Template-Based Modeling vs. Free Modeling

| Performance Metric | Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Free Modeling (FM) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical RMSD Range | 1–6 Å [23] | 4–8 Å (traditional methods) [23]; Near-experimental (modern AI, e.g., AlphaFold2) [12] |

| Typical TM-score Range | >0.5 (with good templates) [23] | ≤0.17 (random); >0.5 (correct topology) [23]; Often >0.7 (modern AI) [12] |

| Key Accuracy Factor | Sequence identity to template (>30% for high accuracy) [21] [23] | Depth/quality of Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [12] |

| Suitable Application Resolution | High- to Medium-resolution models [23] | Low-resolution to High-resolution (modern AI) [19] [12] |

| Strength | High accuracy when good templates exist; computationally efficient [18] [22] | Can predict novel folds not in databases [19] [20] |

| Limitation | Cannot predict novel folds; accuracy drops sharply with lower template similarity [20] [23] | Computationally demanding; traditionally unreliable for large proteins [20] [23] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data in Table 1 reveals a clear performance landscape. Template-Based Modeling excels when the target protein has a homologous structure in the PDB. The accuracy is strongly correlated with sequence identity; a common benchmark is that sequences with more than 30% identity to a template can often produce good quality models [21] [23]. In such cases, TBM can generate high-resolution models with a backbone accuracy (Cα RMSD) of 1–2 Å, rivaling the accuracy of low-resolution experimental structures [23]. This makes TBM highly useful for applications like computational ligand screening and guiding site-directed mutagenesis [23]. However, its major weakness is its inability to predict structures for proteins with novel folds, as it is entirely dependent on the repertoire of known structures [20].

Free Modeling was historically considered a method of last resort, producing low-resolution models (4–8 Å RMSD) suitable only for fold-level insights [23]. This changed dramatically with the advent of deep learning. Modern FM tools like AlphaFold2 have demonstrated accuracy "competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases," achieving median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD in the blind CASP14 assessment [12]. This breakthrough has blurred the historical performance gap, making FM the dominant paradigm for proteins without close templates. Nevertheless, the accuracy of these methods can still be limited for proteins with shallow evolutionary histories (resulting in poor MSAs) or complex multi-domain assemblies [19] [12].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments are the gold standard for objectively evaluating the accuracy of protein structure prediction methods [19] [20]. This biennial, blind competition tests methods on proteins whose structures have been recently solved but not yet publicly released.

Key CASP Experiment Protocol

- Target Selection and Sequence Distribution: Organizers select a set of "target" proteins with structures determined experimentally but unreleased. Only the amino acid sequences of these targets are provided to predictors [12].

- Model Prediction: Participating research groups worldwide submit their predicted 3D models for each target sequence within a defined timeframe. They may use any methodology, including TBM, FM, or hybrid approaches.

- Blind Assessment: Predictions are compared against the experimental ground-truth structures using quantitative metrics. The primary metrics include:

- Global Distance Test (GDT): A measure of the overall structural similarity, ranging from 0-100, with higher scores indicating better models [22].

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in the predicted and native structures after superposition. Lower values indicate higher accuracy [23].

- TM-score: A metric that is more sensitive to the global topology than local errors. A score >0.5 indicates a model of roughly correct topology, while a score ≤0.17 suggests a random prediction [23].

- Category-based Analysis: Targets are categorized based on the difficulty of finding templates, allowing for separate evaluation of TBM and FM methods [19]. Performance is analyzed to establish the current state-of-the-art and identify promising methodological advances.

Successful protein structure prediction, regardless of the paradigm, relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table details key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids [18]. | TBM: The primary source of structural templates. |

| UniProtKB/TrEMBL | Database | Comprehensive repository of protein sequences and functional information [18] [19]. | Both: Source of target sequences and for building Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs). |

| SWISS-MODEL | Software Tool | Fully automated, web-based protein structure homology modeling server [19]. | TBM: A widely used, accessible tool for comparative (homology) modeling. |

| MODELLER | Software Tool | A program for comparative protein structure modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints [21] [22]. | TBM: Used to build 3D models from a target-template alignment. |

| AlphaFold2 | Software Tool | A deep learning system that predicts protein structure from genetic sequences with high accuracy [12]. | FM: The leading FM method that has revolutionized the field. |

| RoseTTAFold | Software Tool | A deep learning-based three-track neural network for predicting protein structures from sequences [19]. | FM: A highly accurate FM method that balances speed and accuracy. |

| I-TASSER | Software Tool | An integrated platform for automated protein structure and function prediction, combining threading and ab initio modeling [23]. | Hybrid: Often uses a combination of TBM and FM approaches. |

| PyRosetta | Software Tool | A Python-based interface to the Rosetta molecular modeling suite, used for structure prediction, design, and refinement [22]. | Both: Used for de novo structure prediction (FM) and model refinement (TBM). |

Both Template-Based Modeling and Free Modeling are indispensable paradigms in the computational structural biologist's toolkit. TBM remains a highly accurate and efficient approach for predicting structures when a clear template exists, making it invaluable for tasks requiring high-resolution models, such as drug docking and detailed mechanistic studies. Its performance is robust and well-understood, though inherently limited by the scope of the PDB. In contrast, FM has been transformed by deep learning from a specialized last-resort technique into a powerful, general-purpose method. Modern FM tools like AlphaFold2 can now regularly predict structures at near-experimental accuracy, even for proteins with no close structural homologs, effectively enabling large-scale structural bioinformatics.

The choice between these paradigms is no longer strictly binary. The field is increasingly moving towards hybrid methods that leverage the strengths of both. For instance, some of the best-performing servers in recent CASP experiments use deep learning to refine TBM-generated models or to select and combine information from multiple weak templates [22]. For researchers, the practical guidance is straightforward: if a high-identity template is available, TBM is a reliable and fast option. For novel folds, orphan sequences, or when pursuing the highest possible accuracy, a state-of-the-art FM method is the preferred choice. As both computational power and the richness of biological databases continue to grow, the integration of these two paradigms will undoubtedly drive the next wave of advances in protein structure prediction.

The Critical Role of Community-Wide Assessments (CASP)

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, blind experiment that has been conducted every two years since 1994 to objectively determine the state of the art in modeling protein structure from amino acid sequence [24]. As an independent evaluation mechanism, CASP provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with rigorous comparative assessments of computational methods against experimental structures [25]. This article examines CASP's experimental framework, its evolution in response to methodological breakthroughs, and its pivotal role in validating tool accuracy through quantitative comparison.

CASP Experimental Design and Protocol

Target Selection and Blind Testing

CASP operates as a double-blind experiment where neither predictors nor organizers know target protein structures during the prediction phase [24]. Targets are soon-to-be-solved structures or recently solved structures kept on hold by the Protein Data Bank, ensuring no participant has prior structural information [24]. For CASP15, organizers posted sequences of unknown protein structures from May through August 2022, with nearly 100 research groups worldwide submitting more than 53,000 models on 127 modeling targets [25].

Assessment Methodologies

Independent assessors evaluate submitted models using multiple complementary metrics when experimental structures become available [25]. The primary evaluation incorporates both distance-based and contact-based measures:

- Global Distance Test (GDT_TS): A core metric measuring the percentage of well-modeled residues within specified distance thresholds, providing a single summary score between 0-100% where higher values indicate better models [24] [26]

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between equivalent atoms in predicted and experimental structures, with lower values indicating higher accuracy [26]

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): A superposition-free score that evaluates local agreement between predicted and experimental structures [12]

The following Dot language code defines the workflow of a typical CASP experiment:

Evolution of CASP Assessment Categories

CASP has continuously adapted its evaluation framework to reflect methodological advances. CASP15 featured significant category revisions in response to the dramatically improved accuracy of deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold [25] [19].

Table: CASP15 Modeling Categories and Focus Areas

| Category | Assessment Focus | Key Changes from CASP14 |

|---|---|---|

| Single Protein/Domain Modeling | Fine-grained accuracy of local main chain motifs and side chains | Elimination of distinction between template-based and template-free modeling [25] |

| Assembly | Domain-domain, subunit-subunit, and protein-protein interactions | Continued collaboration with CAPRI partners [25] |

| Accuracy Estimation | Multimeric complexes and inter-subunit interfaces | Shift to pLDDT units instead of Angstroms; removal of single protein estimation category [25] |

| RNA Structures & Complexes | RNA models and protein-RNA complexes | Pilot experiment in collaboration with RNA-Puzzles [25] |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Ligand binding interactions | Pilot experiment subject to resource availability [25] |

| Protein Conformational Ensembles | Structure ensembles and alternative conformations | New category addressing local conformational heterogeneity [25] |

Categories discontinued after CASP14 include contact and distance prediction, refinement, and domain-level estimates of model accuracy, reflecting how the field has evolved beyond these specific challenges [25].

Quantitative Performance Assessment in CASP

The AlphaFold Breakthrough in CASP14

The CASP14 assessment in 2020 marked a watershed moment when AlphaFold2 demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental structures [12]. The quantitative results revealed unprecedented prediction quality:

Table: CASP14 Protein Structure Prediction Accuracy (Backbone Atoms)

| Method | Median RMSD₉₅ (Å) | 95% Confidence Interval | All-Atom RMSD₉₅ (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.96 | 0.85-1.16 | 1.5 |

| Next Best Method | 2.8 | 2.7-4.0 | 3.5 |

AlphaFold2 achieved a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD₉₅ (Cα root-mean-square deviation at 95% residue coverage), compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method [12]. This performance level – where the width of a carbon atom is approximately 1.4 Å – demonstrated that computational predictions could regularly reach atomic-level accuracy [12].

Assessment Metrics and Their Interpretation

CASP employs multiple metrics to provide comprehensive evaluation, each with specific strengths for different aspects of model quality:

Table: Key Protein Structure Comparison Metrics in CASP

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Average percentage of Cα atoms under different distance cutoffs (1, 2, 4, 8 Å) | 0-100% scale; higher values indicate better models | Robust to localized errors; provides single summary score [24] [26] | May mask regional inaccuracies in otherwise good models |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation of atomic positions after superposition | Lower values indicate higher accuracy; measured in Ångströms | Intuitive geometric interpretation [26] | Highly sensitive to largest errors; global RMSD dominated by worst-modeled regions [26] |

| lDDT | Local Distance Difference Test without superposition | 0-100 scale; residue-level accuracy estimate | Superposition-free; evaluates local quality; more relevant for functional regions [12] | Less familiar to non-specialists than RMSD |

Successful participation in CASP and protein structure prediction research requires specialized computational tools and databases:

Table: Key Research Reagents for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to CASP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids | Source of template structures and training data; reference for model validation [27] [18] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) | Data Resource | Collections of evolutionarily related protein sequences | Provides evolutionary constraints for deep learning methods like AlphaFold [12] [28] |

| Evoformer | Neural Network Architecture | Processes MSAs and residue pairs through attention mechanisms | Core component of AlphaFold2 that enables reasoning about spatial and evolutionary relationships [12] [28] |

| AlphaFold2 | Prediction Software | End-to-end deep learning system for protein structure prediction | Current state-of-the-art method; has transformed expectations for accuracy [12] [19] |

| pLDDT | Confidence Metric | Per-residue estimate of model reliability (0-100 scale) | Standardized accuracy estimation in CASP15; replaces Angstrom-based measures [25] [12] |

The following Dot language code illustrates the architectural innovation of AlphaFold2 that drove recent performance improvements:

CASP has provided the essential framework for quantifying progress in protein structure prediction for nearly three decades. Through its rigorous blind testing protocols and independent assessment, CASP offers the scientific community validated benchmarks for method comparison. The experiment's evolving categories reflect the field's shifting challenges, from template-based modeling to the current emphasis on multimeric complexes, conformational ensembles, and accuracy estimation. As deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 have dramatically raised the accuracy ceiling, CASP's role has expanded to include more nuanced evaluations of model quality, ensuring it remains the definitive standard for assessing computational structure prediction tools relevant to drug discovery and basic biological research.

Methodologies in Action: How Modern AI Tools Predict Structure and Inform Biomedical Research

The prediction of protein three-dimensional (3D) structures from amino acid sequences represents a cornerstone of modern structural biology and drug discovery. For decades, this problem stood as a significant scientific challenge, with experimental methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy providing accurate structures but requiring substantial time and resources [29]. The landscape transformed with the advent of deep learning approaches, leading to the development of several powerful computational tools that have dramatically accelerated and enhanced protein structure prediction. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of four leading tools in this domain: AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, RoseTTAFold, and ESMFold, focusing on their architectures, performance metrics, and applicability in research and development contexts relevant to scientists and drug development professionals.

Tool Architectures and Core Methodologies

The predictive performance of each tool is fundamentally governed by its underlying architecture and the type of biological information it utilizes.

AlphaFold2

Developed by Google's DeepMind, AlphaFold2 utilizes an intricate architecture that processes evolutionary information derived from Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) [29]. These MSAs, built from databases of related protein sequences, allow the model to identify co-evolved residue pairs that hint at spatial proximity in the 3D structure. The model employs a novel attention-based neural network that jointly embeds MSA and pairwise representations, followed by a structure module that iteratively refines atomic coordinates [29]. Its training leveraged a vast dataset of known protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

RoseTTAFold

Created by the Baker lab, RoseTTAFold is a "three-track" neural network that simultaneously considers information at one-dimensional (sequence), two-dimensional (distance between residues), and three-dimensional (spatial coordinates) levels [30]. This design allows information to flow seamlessly between these tracks, enabling the network to reason collectively about the relationship between a protein's sequence and its final folded structure [30]. Like AlphaFold2, it relies on MSAs as a primary input. Its subsequent evolution, RoseTTAFoldNA, extended this architecture to handle nucleic acids and protein-nucleic acid complexes by adding tokens for DNA and RNA nucleotides and incorporating physical information like Lennard-Jones and hydrogen-bonding energies into its loss function [31].

ESMFold

Developed by Meta AI, ESMFold takes a significantly different approach. It does not rely on MSAs [29] [32]. Instead, it uses a large protein language model called Evolutionary Scale Modeling (ESM-2), which is trained on millions of protein sequences to learn fundamental principles of protein biochemistry and structure. The structural prediction is generated directly from the embeddings created by this language model [32]. This makes ESMFold exceptionally fast—reportedly up to 60 times faster than AlphaFold2 for short sequences—but generally with lower overall accuracy compared to MSA-dependent methods [29] [32].

AlphaFold3

The latest iteration from DeepMind, AlphaFold3, introduces a diffusion-based architecture that moves away from predicting torsion angles and instead directly predicts the 3D coordinates of atoms [33] [34]. This allows it to model a much broader range of biomolecular complexes, including proteins, nucleic acids (DNA/RNA), small molecules, ions, and modified residues [34]. While it maintains high accuracy for proteins, its expansion to other biomolecules marks its key architectural advancement.

The following diagram summarizes the core architectural workflows and relationships between these tools.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The accuracy, speed, and applicability of these tools vary significantly, making each suitable for different research scenarios. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of their performance.

| Tool | Core Input | Reported Accuracy (TM-Score / lDDT) | Inference Speed | Key Outputs | Confidence Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | MSA | High (Median RMSD vs. experiment: ~1.0 Å) [35] | Slow (minutes to hours) [29] | Protein structures | pLDDT, PAE [36] [35] |

| RoseTTAFold | MSA | High (Comparable to AlphaFold2) [30] | Medium (e.g., ~10 mins on gaming PC) [30] | Protein structures, Protein-NA complexes (RFNA) [31] | lDDT, PAE [31] |

| ESMFold | Single Sequence | Lower than AF2/RF [29] [32] | Very Fast (e.g., ~60x AF2 on short sequences) [29] [32] | Protein structures | pLDDT [32] |

| AlphaFold3 | Single Sequence / MSA? | High for proteins, emerging for RNA/DNA [33] [34] | Not Well Documented | Proteins, DNA, RNA, Ligands, Ions [34] | pLDDT, PAE (inferred) |

Analysis of Performance Data

Accuracy vs. Experimental Structures: A systematic analysis of AlphaFold2 predictions against experimental nuclear receptor structures found that while it achieves high accuracy for stable conformations with proper stereochemistry, it shows limitations in capturing the full spectrum of biologically relevant states [36]. Specifically, it systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and misses functionally important asymmetry in homodimeric receptors [36]. The median RMSD between AlphaFold2 predictions and experimental structures is 1.0 Å, which is slightly higher than the median RMSD of 0.6 Å between different experimental structures of the same protein [35].

Performance on Complexes:

- RoseTTAFoldNA: When predicting protein-nucleic acid complexes, RoseTTAFoldNA produces models with an average Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT) score of 0.73 for monomeric protein complexes. Among its high-confidence predictions (mean interface PAE < 10), 81% correctly model the protein-nucleic acid interface [31].

- AlphaFold3: For RNA structure prediction, benchmarks show that AlphaFold3 does not outperform human-assisted methods and its performance varies across different RNA test sets [33].

- ESMFold for Docking: In protein-peptide docking, a benchmark study found that using ESMFold with a polyglycine linker and a random masking strategy yielded successful docking (DockQ ≥ 0.23) in about 40% of viable cases, a performance generally lower than specialized tools like AlphaFold-Multimer but achieved with greater computational efficiency [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and critical assessment, researchers must understand the key experimental and benchmarking methodologies used to evaluate these tools.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Predictive Accuracy against Experimental Structures

This protocol is used to assess the geometric accuracy of a predicted model against a experimentally determined reference structure [36] [35].

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the experimental structure from the PDB and the predicted model from a database (e.g., AlphaFold DB) or generate it using the tool's software.

- Structural Alignment: Superimpose the predicted model onto the experimental structure using a rigid body alignment algorithm based on conserved core residues.

- Calculation of Deviation Metrics:

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the RMSD of atomic positions (typically Cα atoms) after optimal superposition. A lower RMSD indicates a closer match [35].

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): Calculate the lDDT score, a superposition-free metric that evaluates the local distance differences of atoms within a defined cutoff. It is more robust to errors in flexible regions than RMSD [31].

- Analysis of Specific Regions: Calculate metrics for specific functional regions, such as ligand-binding pockets, to identify domain-specific variations in accuracy [36].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Protein-Peptide Docking Performance

This protocol assesses a tool's ability to predict the structure of a protein-peptide complex [32].

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a benchmark dataset of high-resolution experimental structures of protein-peptide complexes from the PDB, ensuring no overlap with the training data of the evaluated models.

- Model Generation:

- Linker Strategy: For tools designed for single-chain prediction (e.g., ESMFold), connect the protein and peptide sequences with a flexible polyglycine linker (e.g., 30 residues) [32].

- Sampling Enhancement: Employ strategies like random masking of input residues to generate multiple candidate models and enhance structural diversity [32].

- Model Evaluation:

- DockQ Scoring: Use the DockQ score to evaluate docking quality. It combines the metrics of Ligand RMSD (LRMSD), Interface RMSD (IRMSD), and Fraction of Native Contacts (FNat). Scores are categorized as acceptable (0.23-0.49), medium (0.5-0.8), or high quality (≥0.8) [32].

- Success Rate Calculation: Determine the percentage of cases in the benchmark set where the top-ranked model achieves an acceptable DockQ score or higher.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources and computational components essential for working with protein structure prediction tools.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. Used for training, validation, and benchmarking [36]. | RCSB PDB (rcsb.org) |

| UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) | Comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information. Used to find sequences for prediction and to generate MSAs [36]. | UniProt (uniprot.org) |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Input for MSA-dependent models (AF2, RF). Maps evolutionary relationships to infer structural constraints [29]. | Generated from databases like UniRef using tools like HHblits. |

| ColabFold | Popular and accessible web-based platform that integrates AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold with streamlined MSA generation, lowering the barrier to entry [32]. | Google Colab notebooks |

| Predicted lDDT (pLDDT) | Per-residue confidence score provided by prediction tools. Scores >90 indicate high confidence, while scores <50 indicate very low confidence/disorder [36] [35]. | Integral output of AF2, ESMFold, etc. |

| Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) | A 2D plot representing the expected positional error between residues in the predicted model. Critical for assessing inter-domain and protein-protein interaction confidence [35]. | Integral output of AF2, RFNA, etc. |

| GPUs (High-Performance) | Essential hardware for training models and performing inference in a reasonable time frame. | NVIDIA A100, V100, or similar consumer-grade GPUs [32]. |

The current landscape of protein structure prediction offers a suite of powerful tools, each with distinct strengths. AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold provide the highest accuracy for single proteins and have been extended to model complexes, with RoseTTAFoldNA specializing in protein-nucleic acid interactions [29] [31]. ESMFold offers a compelling trade-off, providing fast and accessible predictions that are valuable for high-throughput screening or orphan proteins, albeit with lower accuracy [29] [32]. AlphaFold3 represents a significant step toward a unified model for biomolecular complexes, though its performance on non-protein components is still under active evaluation [33] [34].

For researchers in drug discovery, the choice of tool depends on the specific question. If atomic-level accuracy for a specific protein target is critical for small-molecule docking, AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold are the preferred choices, with careful attention given to confidence metrics in the binding pocket [36]. For proteome-wide analyses or engineering of novel proteins and peptides, the speed of ESMFold or the complex-modeling capabilities of RoseTTAFoldNA and AlphaFold3 become highly advantageous. Future developments will likely focus on improving the prediction of conformational dynamics, multi-state proteins, and the integrative modeling of larger cellular assemblies, further closing the gap between computational prediction and biological reality.

In the field of computational biology, Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) serve as a fundamental bridge between protein sequence evolution and three-dimensional structure. MSAs capture the evolutionary history of a protein family by aligning related sequences to identify conserved residues and co-evolutionary patterns. This information is crucial for accurate protein structure prediction, as it provides the statistical evidence needed to infer spatial constraints between amino acids. The rise of deep learning methods like AlphaFold has further amplified the importance of high-quality MSAs, which are now a standard input for state-of-the-art prediction pipelines [27] [18]. Within the framework of protein structure prediction research, evaluating the accuracy of these tools depends heavily on the MSAs fed into them, making the choice of MSA generation method a critical variable in any comparative assessment.

Comparative Performance of MSA Tools

The accuracy of a downstream predicted protein structure is profoundly influenced by the quality of the input MSA. Therefore, selecting an appropriate MSA tool is a vital first step in the structure prediction workflow. Independent comparative studies evaluate these tools using benchmark datasets and standardized metrics, such as the Sum-of-Pairs Score (SPS) and the Total Column Score (TC), which measure how closely a tool's alignment matches a reference alignment of known correctness [37] [38].

A comprehensive evaluation of ten popular MSA tools revealed significant differences in their ability to generate accurate alignments. The following table summarizes the key findings from this large-scale comparison, which tested the tools on alignments generated with varying evolutionary parameters [38].

Table 1: Overall Performance Ranking of MSA Tools

| Rank | Tool | Relative Accuracy | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ProbCons | Top | Consistently produced the highest-quality alignments but relatively slow. |

| 2 | SATé | High | Excellent balance of accuracy and speed; significantly faster than ProbCons. |

| 3 | MAFFT (L-INS-i) | High | Accurate, especially with complex indel events. |

| 4 | Kalign | Medium-High | Achieved high SPS scores efficiently. |

| 5 | MUSCLE | Medium-High | A reliable and widely-used benchmark tool. |

| 6 | Clustal Omega | Medium | Improved scalability over previous versions. |

| 7 | MAFFT (FFT-NS-2) | Medium | Faster, less accurate strategy than L-INS-i. |

| 8 | T-Coffee | Medium | Good accuracy but computationally intensive. |

| N/A | Dialign-TX, Multalin | Lower | Generally lower accuracy in the tested scenarios. |

The study concluded that alignment quality was most strongly affected by the number of deletions and insertions in the sequences, while sequence length and indel size had a weaker effect [38].

Performance on a Standardized Project

The practical impact of tool selection is evident in focused research projects. For instance, a 2024 computational project compared MSA tools (MAFFT, Muscle, ClustalW) against probabilistic methods like Profile Hidden Markov Models (ProfileHMM) using the BaliBase (RV11 and RV12) benchmark datasets. The evaluation metrics included SP and TC scores, runtime, and Leave-One-Out Cross Validation [37]. The findings from such projects generally align with larger studies, confirming that MSA method choice directly influences the quality of the evolutionary data used for downstream structure prediction tasks.

Experimental Protocols for MSA Evaluation

The rigorous evaluation of MSA tools, as cited in the comparison above, relies on a structured experimental protocol. This methodology ensures that performance comparisons are objective, reproducible, and relevant to real-world research scenarios.

Workflow for MSA Tool Benchmarking

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for benchmarking MSA tools, from dataset generation to final accuracy assessment.

Detailed Methodology

The protocol can be broken down into the following key steps:

Dataset Generation:

- Simulated Sequences: Using a tool like

indel-Seq-Gen (iSGv2.0), researchers generate sequence families with a known evolutionary history and a known true alignment [38]. This process starts with generating model phylogenetic trees using packages likeTreeSimin R. iSG then evolves sequences along these trees, introducing indels and substitutions according to specified parameters (e.g., insertion rate, deletion rate, sequence length, indel size), resulting in both the true ("reference") alignment and the unaligned sequences [38]. - Benchmark Datasets: Manually curated reference datasets like BaliBase are also used. These contain expertly aligned sequences for specific protein families, providing a gold standard for testing [37] [38].

- Simulated Sequences: Using a tool like

Tool Execution: The generated unaligned sequence files are used as input for each MSA tool under evaluation (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE, Clustal Omega, ProbCons) [38].

Accuracy Measurement: The alignment produced by each tool (the "test alignment") is compared against the known reference alignment. The two primary metrics used are:

- Sum-of-Pairs Score (SPS): The proportion of correctly aligned residue pairs in the test alignment relative to the reference. A higher SPS indicates better accuracy [38].

- Column Score (CS): The proportion of correctly aligned entire columns in the test alignment. This is a stricter metric than SPS [38].

- Statistical tests, such as one-way ANOVA and post-hoc analyses, are often applied to determine if the performance differences between tools are statistically significant [38].

From MSAs to 3D Structures: The Prediction and Evaluation Workflow

The ultimate test of MSA quality is the accuracy of the protein structure models it helps generate. The field has moved towards integrated, large-scale benchmarks that cover the entire pipeline, from MSA generation to the final evaluation of predicted structures.

The Role of MSAs in Structure Prediction

Modern protein structure prediction approaches are categorized based on their reliance on templates. As shown in the diagram below, MSAs are a critical input for both template-based and template-free modeling (TFM), which includes deep learning methods like AlphaFold [27] [18].

Evaluating Predicted Structures with PSBench

Once a 3D structural model is generated, its quality must be assessed. Benchmarks like PSBench have been developed to evaluate the accuracy of Estimation of Model Accuracy (EMA) methods, which are used to rank and select the best predicted models [39] [40]. PSBench is a large-scale benchmark comprising over a million structural models generated for CASP15 and CASP16 protein complex targets using tools like AlphaFold2-Multimer and AlphaFold3 [40].

- Key Evaluation Metrics in PSBench: For each predicted model, multiple quality scores are calculated against the experimental (true) structure. These include [39]:

- Global Quality Scores:

tmscore(4 variants) andrmsd, which measure the overall similarity of the model's fold to the native structure. - Local Quality Scores:

lddt, which assesses the local atomic accuracy. - Interface Quality Scores:

ics,ips, anddockq_wave, which are critical for evaluating multi-chain protein complexes.

- Global Quality Scores:

- EMA Method Evaluation: PSBench provides scripts to evaluate how well an EMA method's predicted scores correlate with the true quality scores using metrics like Pearson correlation, Spearman correlation, and top-1 ranking loss [39]. This creates a full-cycle evaluation framework: good MSAs lead to better predicted structures, and good EMA methods are needed to identify them.

To conduct rigorous MSA and protein structure prediction research, scientists rely on a suite of software tools, benchmark datasets, and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Resources for MSA and Structure Prediction Research

| Category | Resource Name | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MSA Software | MAFFT, MUSCLE, Clustal Omega, ProbCons | Generates multiple sequence alignments from unaluted sequences; choice of tool impacts downstream prediction accuracy [38] [41]. |

| Benchmark Datasets | BaliBASE, PSBench | Provides standardized datasets with reference alignments (BaliBASE) or labeled structural models (PSBench) for tool evaluation and method training [37] [39] [38]. |

| Structure Prediction Tools | AlphaFold2/3, I-TASSER, D-I-TASSER | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences and MSAs; represents the downstream application of MSA data [42] [18]. |

| Evaluation Suites | PSBench Evaluation Scripts | Automates the assessment of predicted model quality (EMA) by calculating correlation metrics between predicted and true scores [39]. |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures; used as a source of templates and for validation [27] [18]. |

| Sequence Databases | UniProt, TrEMBL | Comprehensive sources of protein sequences required for building informative MSAs [18]. |

The challenge of predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence alone—known as the protein folding problem—has been a central focus in computational biology for over 50 years [43]. Proteins are essential to life, and understanding their structure facilitates a mechanistic understanding of their function. While experimental methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM have determined structures for approximately 100,000 unique proteins, this represents only a small fraction of the billions of known protein sequences [43]. This structural coverage bottleneck, requiring months to years of painstaking experimental effort per structure, has driven the development of computational approaches to enable large-scale structural bioinformatics [43] [44].

Recent years have witnessed a revolution in protein structure prediction, largely driven by advances in deep learning. Modern computational methods can now regularly predict protein structures with atomic accuracy, even in cases where no similar structure is known [43]. These developments have profound implications for drug discovery, bioinformatics, and molecular biology, enabling researchers to rapidly generate structural hypotheses for previously uncharacterized proteins [45] [46]. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary protein structure prediction tools, their performance characteristics, and the experimental protocols used for their validation, framed within the broader context of evaluating accuracy in structural bioinformatics research.

Fundamental Approaches

Computational methods for protein structure prediction have evolved along two complementary paths focusing on either physical interactions or evolutionary history. The physical interaction approach integrates understanding of molecular driving forces into thermodynamic or kinetic simulations of protein physics. While theoretically appealing, this approach has proven challenging for even moderate-sized proteins due to computational intractability, context-dependent protein stability, and difficulties in producing sufficiently accurate physics models [43].

The evolutionary approach, which has gained prominence in recent years, derives structural constraints from bioinformatics analysis of protein evolutionary history. This method leverages the insight that proteins with similar functions often have similar structures and show evolutionary conservation across species [47]. The key principle is that during evolution, pairs of residues that are mutually proximate in the tertiary structure tend to co-evolve to maintain structural integrity [48].

The Deep Learning Revolution

The breakthrough in prediction accuracy came with the integration of deep learning architectures that could effectively leverage both evolutionary information and structural constraints. Modern neural network-based models like AlphaFold represent a fundamental shift in approach, incorporating novel architectures that jointly embed multiple sequence alignments and pairwise features while enabling direct reasoning about spatial and evolutionary relationships [43].

These advances were validated through the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP), a biennial blind assessment that serves as the gold standard for evaluating prediction accuracy. In CASP14, AlphaFold demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases, greatly outperforming other methods with a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method [43].

Key Protein Structure Prediction Tools

MSA-Based Prediction Tools

AlphaFold represents a landmark advancement in protein structure prediction. Its neural network architecture incorporates physical and biological knowledge about protein structure, leveraging multi-sequence alignments within its deep learning algorithm. The system comprises two main stages: the Evoformer block that processes inputs through a novel neural network architecture, and the structure module that introduces explicit 3D structure in the form of rotations and translations for each residue [43]. AlphaFold demonstrated the first computational approach capable of predicting protein structures to near-experimental accuracy in most cases, with an all-atom accuracy of 1.5 Å compared to 3.5 Å for the best alternative method during CASP14 [43].

RoseTTAFold utilizes a three-track neural network that simultaneously reasons about one-dimensional sequences, two-dimensional distance maps, and three-dimensional coordinates. This architecture allows information to flow back and forth between 1D amino acid sequence information, 2D distance maps, and 3D coordinates, enabling the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates [47]. A significant advantage of RoseTTAFold is its ability to predict structures of large proteins using a single GPU, making it more accessible than systems requiring multiple powerful GPUs [47].

Single-Sequence-Based Prediction Tools

SPIRED (Structural Prediction Based on Inter-Residue Relative Displacement) is a single-sequence-based structure prediction model that achieves comparable performance to state-of-the-art methods but with approximately 5-fold acceleration in inference and at least one order of magnitude reduction in training consumption [49]. Through an innovative design in model architecture and loss function, SPIRED addresses the prohibitive computational costs that limit the application of other methods for high-throughput structure prediction. When integrated with downstream neural networks, it forms an end-to-end framework (SPIRED-Fitness) for rapid prediction of both protein structure and fitness from single sequences [49].

ESMFold and OmegaFold are other single-sequence predictors that employ pre-trained protein language models to learn evolutionary information from dependencies between amino acids in hundreds of millions of available protein sequences. These methods achieve structure prediction for generic proteins in seconds, surpassing AlphaFold's speed by orders of magnitude, though SPIRED shows faster inference times compared to both [49].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Tool | Input Requirements | Key Features | Computational Demand | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold | Amino acid sequence + MSA | High accuracy (0.96 Å backbone), Evoformer architecture, atomic coordinates | High (multiple GPUs recommended) | Research requiring highest accuracy, detailed structural analysis |

| RoseTTAFold | Amino acid sequence + MSA | Three-track neural network, 1D-2D-3D information flow | Medium (single GPU sufficient) | Large protein prediction, limited computational resources |

| SPIRED | Single amino acid sequence | Fast inference (5× faster), low training consumption, fitness prediction | Low (efficient on single GPU) | High-throughput screening, integrated structure-fitness prediction |

| ESMFold | Single amino acid sequence | Protein language model, rapid prediction | Medium | Quick structural hypotheses, large-scale analyses |

| OmegaFold | Single amino acid sequence | Leverages protein language model | Medium | Generic protein prediction without MSA requirement |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Benchmarking Methodologies

The performance of protein structure prediction tools is typically evaluated using standardized benchmarks that assess accuracy against experimentally determined structures. The most prominent evaluation frameworks include:

CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction): A biennial blind assessment that uses recently solved structures not yet deposited in the Protein Data Bank, providing an unbiased test of prediction accuracy [43] [49]. CASP has long served as the gold standard for evaluating the accuracy of structure prediction methods.

CAMEO (Continuous Automated Model Evaluation): A continuous benchmarking platform that evaluates prediction methods on newly released protein structures, providing ongoing assessment of performance [49].

Key metrics used in these evaluations include:

- TM-score: A metric for measuring the similarity of protein topologies, where scores range from 0-1, with higher scores indicating better structural alignment [49].

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed proteins, with lower values indicating higher accuracy [43].

- pLDDT (predicted Local Distance Difference Test): A per-residue estimate of prediction confidence that reliably predicts the local accuracy of the corresponding prediction [43].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative comparisons of prediction tools. On the CAMEO dataset comprising 680 single-chain proteins, SPIRED achieved an average TM-score of 0.786 without recycling, slightly surpassing OmegaFold (average TM-score = 0.778) and approaching ESMFold performance despite having approximately five times fewer parameters [49].

For CASP15 targets, SPIRED exhibited similar prediction accuracy to OmegaFold, with both methods showing strong performance across diverse protein folds. ESMFold generally demonstrates better performance on both CAMEO and CASP15 sets, which can be attributed to its larger parameter count and training on a substantial amount of AlphaFold2-predicted structures [49].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison on Standard Benchmarks

| Tool | CAMEO (680 proteins) Average TM-score | CASP15 (45 domains) Performance | Inference Time (500-residue protein) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold | N/A | Reference standard | Minutes to hours (varies) | High computational demand, MSA requirement |

| RoseTTAFold | N/A | High accuracy | Moderate | Less accurate than AlphaFold |

| SPIRED | 0.786 | Comparable to OmegaFold | ~1.6 seconds | Slightly less accurate than ESMFold |

| ESMFold | ~0.81 (estimated) | Best performing | ~8 seconds | Large model size, resource intensive |

| OmegaFold | 0.778 | Comparable to SPIRED | ~8 seconds | Requires recycling for best accuracy |