Evaluating Protein-Protein Interaction Interfaces: From AI-Driven Prediction to Therapeutic Targeting

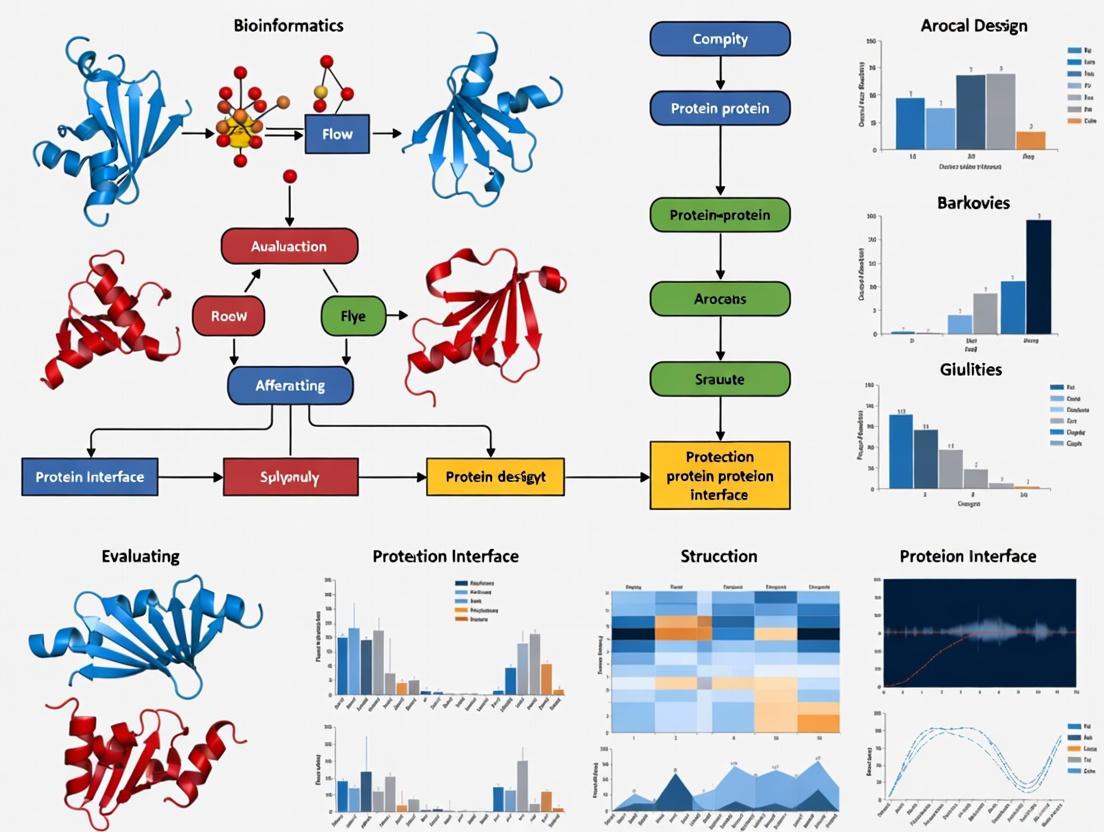

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of computational methods for predicting and analyzing protein-protein interaction (PPI) interfaces, a critical frontier in structural biology and drug discovery.

Evaluating Protein-Protein Interaction Interfaces: From AI-Driven Prediction to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of computational methods for predicting and analyzing protein-protein interaction (PPI) interfaces, a critical frontier in structural biology and drug discovery. We explore the fundamental principles of PPIs, then detail a landscape of methodologies from traditional docking to cutting-edge, template-free AI and protein language models. The content addresses core challenges like protein flexibility and intrinsically disordered regions, while offering a comparative analysis of tool accuracy and performance on standardized benchmarks. Finally, we synthesize key validation strategies and discuss how these advanced computational approaches are poised to accelerate the development of PPI-targeted therapeutics.

The Blueprint of Cellular Dialogue: Understanding PPI Interfaces

Defining Protein-Protein Interactions and Their Role in Health and Disease

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are the dynamic partnerships that proteins form within a cell and are central to virtually all biological processes, including metabolism, transport, structural organization, signal transduction, cell-cycle control, immune recognition, and gene transcription [1]. Over 80% of all proteins do not exist in isolation but rather interact with others to form stable or transient complexes to execute their functions [1]. Understanding PPIs is critical for comprehending cellular functions, diseases, and advancing drug discovery, as aberrant PPIs contribute to the pathogenesis of numerous human diseases [1] [2].

PPIs are fundamentally characterized as either stable or transient, with both types exhibiting varying strengths [3]. Stable interactions are associated with proteins that purify as multi-subunit complexes, such as hemoglobin, while transient interactions are temporary and often require specific conditions such as phosphorylation, conformational changes, or cellular localization [3]. The biological effects of these interactions are diverse, ranging from altering enzyme kinetics and creating new binding sites to inactivating proteins or changing their substrate specificity [3].

Quantitative Characterization of PPIs

The affinity and kinetics of PPIs are fundamental to understanding their biological roles and therapeutic potential. The dissociation constant (Kd) quantifies binding affinity, while thermodynamic and kinetic parameters reveal the nature and stability of complexes. The following experimental methods provide this crucial quantitative data.

Table 1: Biophysical Methods for Quantifying Protein-Protein Interactions

| Method | Principle | Affinity Range | Key Measurements | Sample Consumption | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [1] | Measures change in molecular rotation of a fluorophore upon binding. | nM to mM | Kd | Dozens of µL at nM concentration | Automated high-throughput; simple mix-and-read format | Requires a large change in size upon binding; fluorescent interference |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [1] | Detects changes in refractive index at a sensor surface in real-time. | sub-nM to low mM | Kd, kon, koff | Several µg per sensor chip | Label-free; provides real-time kinetics | Surface immobilization can interfere with binding |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [1] | Measures heat released or absorbed during binding. | nM to sub-µM | Kd, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS | Several hundred µg per assay | Label-free; provides full thermodynamic profile | Low throughput and sensitivity; buffer limitations |

| Protein Microarrays [4] | Fluorescently labeled probe bound to immobilized protein domains. | < 50 µM | Kd (for higher affinity) | 1 µg protein for >1,000 assays | High-throughput; minimal sample consumption; assesses selectivity | Limited to soluble, well-folded domains; strictly in vitro |

| Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) [1] | Tracks movement of molecules along a temperature gradient. | pM to mM | Kd | Several µL at nM concentration | Fast measurement; very low sample consumption | Requires fluorescent labelling |

Experimental Protocols for PPI Analysis

A combination of techniques is typically required to validate, characterize, and confirm protein interactions. The choice of method depends on the nature of the interaction (stable vs. transient) and the desired output (identifying partners or quantifying affinity).

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) for Stable Complexes

Co-IP is a widely used method to discover protein interaction partners from a cell lysate under near-physiological conditions [3].

Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare a cell lysate using a non-denaturing lysis buffer to preserve native protein complexes.

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate a specific antibody against your target "bait" protein with Protein A/G-conjugated magnetic or agarose beads.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the antibody-bound beads with the cell lysate. The antibody will bind the bait protein.

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash multiple times with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the immunoprecipitated protein complex from the beads using low-pH buffer, reducing agents, or competitive analytes like the peptide epitope.

- Analysis: Analyze the eluate by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting to detect the "bait" and co-precipitated "prey" proteins. Mass spectrometry can be used for unbiased partner identification.

Protein Microarray for Quantitative, High-Throughput Analysis

Protein microarrays provide an efficient way to identify and quantify domain-mediated PPIs in high throughput with minimal sample consumption [4].

Protocol:

- Array Fabrication: Spot purified, recombinant protein interaction domains (e.g., SH2, PTB, PDZ) in a regular pattern on a chemically derivatized glass substrate. The proteins become immobilized on the surface.

- Blocking: Incubate the array with a blocking solution (e.g., BSA) to prevent non-specific binding.

- Probing: Incubate the array with a fluorescently labeled synthetic peptide or protein probe.

- Washing: Perform brief washing steps to remove unbound probe.

- Detection and Quantification: Scan the array for fluorescence. The signal intensity at each spot is proportional to the amount of bound probe.

- Data Analysis: For high-affinity interactions (e.g., SH2 domains), saturation binding curves can be generated by probing with a range of probe concentrations to directly calculate the Kd on the array. For weaker binders, the array identifies candidate interactions for subsequent quantification by a solution-based method like Fluorescence Polarization [4].

Pull-Down Assays for Recombinant Proteins

Pull-down assays are ideal for studying strong interactions using a recombinant, tagged "bait" protein to purify binding partners ("prey") from a lysate [3].

Protocol:

- Bait Immobilization: Incubate a purified GST-, polyHis-, or streptavidin-tagged bait protein with the corresponding affinity resin (glutathione-, metal chelate-, or biotin-coated beads).

- Binding Reaction: Incubate the immobilized bait protein with a cell lysate or mixture of purified proteins containing the putative prey.

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution and Analysis: Elute the bound complexes competitively (e.g., with reduced glutathione for GST-tags) or under denaturing conditions. Analyze the eluate by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or mass spectrometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful PPI analysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key materials essential for the experiments described in this protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Protein Domains [4] | Well-folded, modular units (e.g., SH2, PTB, PDZ) used as "baits" or "preys" in defined interaction assays. | Production of protein microarrays; quantitative binding studies using FP or SPR. |

| Tag-Specific Affinity Resins [3] | Beaded supports (e.g., Glutathione, Ni-NTA, Streptavidin) for purifying and immobilizing tagged bait proteins. | Pull-down assays; preparation of samples for co-IP. |

| High-Affinity Antibodies [3] | Specific immunoglobulins for capturing and detecting endogenous bait proteins and their partners. | Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP); Western blot analysis. |

| Homobifunctional Crosslinkers [3] | Chemical reagents with two reactive groups that form covalent bonds between interacting proteins. | Stabilization of transient or weak PPIs prior to lysis and analysis. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Fluorescein, Cy5) [1] | Molecules used to label peptides or proteins for detection in fluorescence-based assays. | Probing protein microarrays; Fluorescence Polarization (FP) assays. |

| Defined Peptide Motifs [4] [3] | Short, synthetic peptides representing known binding sequences (e.g., phosphotyrosine, proline-rich). | Probing domain specificity on microarrays; use as competitive eluents in pull-downs. |

Advancements in structural bioinformatics have provided powerful resources for the scientific community. Large-scale datasets and sophisticated analysis tools are indispensable for modern PPI research.

- Pocket-Centric Structural Datasets: Comprehensive datasets now provide high-quality structural information on over 23,000 binding pockets, 3,700 proteins, and nearly 3,500 ligands across more than 500 organisms [2]. These resources are crucial for elucidating the structural basis of disease-associated PPIs and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

- Pocket Classification for Drug Discovery: Binding pockets in PPI complexes are classified into orthosteric competitive (PLOC), orthosteric non-competitive (PLONC), and allosteric (PLA) pockets. This classification is vital for understanding functional implications and training machine learning models for drug design [2].

- The Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP): PLIP is a computational tool that analyses molecular interactions in 3D structures, detecting eight types of non-covalent interactions. Initially focused on small molecules, the latest release incorporates detailed analysis of protein-protein interfaces, revealing how drugs can mimic native interactions [5].

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually all cellular processes, including gene expression, metabolic catalysis, and signal transduction [6]. The physical contacts between proteins are driven by specific biophysical forces that determine the affinity, specificity, and dynamics of these associations. Understanding these forces—primarily electrostatics, hydrophobicity, and solvation effects—is crucial for deciphering biological pathways and designing therapeutic interventions [7] [8]. This Application Note examines the key biophysical principles governing PPI interfaces, providing researchers with structured data, experimental protocols, and computational methodologies for systematic analysis. The insights presented here form an essential foundation for a broader thesis on evaluating PPI interfaces, with particular relevance to drug development targeting previously undruggable proteins through strategies such as targeted protein degradation [9].

Quantitative Forces at PPI Interfaces

The binding affinity and specificity at protein-protein interfaces are governed by a complex interplay of physicochemical forces. The table below summarizes the key biophysical forces, their energetic contributions, and defining characteristics.

Table 1: Key Biophysical Forces Governing Protein-Protein Interfaces

| Force Type | Energetic Contribution | Characteristics & Role in Binding | Experimental Observables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatics | -1 to -3 kcal/mol for a single ion pair; can be much higher for optimized networks [7] | Long-range force guiding partners; sensitive to pH and salt concentration; can steer binding [7] | Salt concentration dependence; pH optimum for binding; pKa shifts of interfacial residues [7] |

| Hydrophobicity | -0.1 to -0.2 kcal/mol per Ų of buried surface area [10] | Driven by entropy gain from released water molecules; creates "sticky" non-polar patches [10] | Non-polar surface area burial; preference for flat, featureless interfaces in some complexes [10] |

| Solvation/Desolvation | Costly penalty for polar groups (+1 to +3 kcal/mol), offset by favorable bond formation [7] | Major barrier to association; removal of water from interacting surfaces precedes H-bond formation [7] | Heat capacity change (ΔCp); measured through thermodynamic profiling |

The electrostatic energy of interaction between two molecules carrying a unit net charge positioned 10Å apart is approximately 1 kJ/mol, significantly exceeding other energy components at such distances [7]. This long-range guidance is particularly important for selective partner recognition among hundreds of thousands of candidates in the cellular environment. Hydrophobic effects primarily drive the association process through the entropic gain of releasing ordered water molecules from non-polar surfaces, while solvation penalties represent a major energetic barrier that must be overcome for stable complex formation.

Computational Analysis of Interface Electrostatics

Computational modeling provides powerful tools for quantifying the electrostatic component of binding free energy. Continuum electrostatics frameworks, which treat the solvent as a homogenous medium, offer speed and avoid convergence problems for large protein-protein complexes [7].

Workflow for Calculating Electrostatic Binding Energy

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for calculating the electrostatic component of the binding free energy, highlighting critical decision points between "rigid body" and "unbound-bound" approaches, as well as "rigid" versus "flexible" charge protocols.

Key Software Solutions

Table 2: Computational Tools for Electrostatic and PPI Analysis

| Tool Name | Methodology | Primary Application | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| DelPhi [7] | Finite-difference Poisson-Boltzmann solver | Calculating electrostatic energies and pKa shifts | Coulombic, solvation, and ionic energy components |

| APBS [7] | Poisson-Boltzmann equation solver | Biomolecular electrostatics calculations | Electrostatic potentials and binding energies |

| PPI-Surfer [10] | 3D Zernike Descriptors (3DZD) | Comparing and quantifying local PPI surface similarity | Surface similarity scores for interface patches |

| PL-PatchSurfer [10] | 3DZD-based surface patch comparison | Virtual screening for ligands binding to PPI sites | Complementarity scores between pockets and ligands |

Protocol: Calculating Salt Dependence of Binding Affinity

Purpose: To quantify how ionic strength affects the electrostatic component of PPI binding, revealing the role of charge-charge interactions [7].

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain 3D structures of the complex and unbound monomers (PDB files). Protonate structures at the desired pH using PDB2PQR or similar tools.

- Parameter Setting: In DelPhi or APBS, set the temperature to 298K and the internal dielectric constant to 2-4 for proteins. Set the external dielectric constant to 80 for water.

- Salt Concentration Series: Perform calculations for a monotonic series of salt concentrations (e.g., 0, 50, 100, 150, 200 mM NaCl).

- Energy Calculation: For each salt concentration, compute the total electrostatic energy for the complex (Gcomplex) and the unbound monomers (GmonomerA + GmonomerB) using the same parameters.

- Binding Energy Calculation: Calculate the electrostatic component of the binding free energy at each salt concentration: ΔΔGelec = Gcomplex - (GmonomerA + GmonomerB).

- Analysis: Plot ΔΔGelec versus salt concentration. Typically, increased salt concentration weakens binding due to charge screening, indicating optimized charge-charge interactions across the interface [7].

Experimental Analysis of PPI Interfaces

Experimental validation is crucial for verifying computational predictions and understanding PPIs in biological contexts. The table below compares the most common in vivo PPI techniques.

Table 3: Comparison of Key In Vivo PPI Detection Techniques

| Method | Organism/System | Principle | Risk of False Positives | Quantification Capability | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [11] [6] | Yeast | Reconstitution of transcription factor | ++ | ++ | Binary interactions; high-throughput screening |

| Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) [11] | Plant, mammalian cells | Reconstitution of fluorescent protein | +++ | + | Visualizing interaction topology; stable complexes |

| FRET-FLIM [11] | Any | Energy transfer & fluorescence lifetime | - | +++ | Highly quantitative analysis; dynamic interactions |

| Split-Luciferase [11] | Plant, mammalian cells | Reconstitution of luciferase enzyme | + | ++ | Kinetic studies; reversible interactions |

| Co-Immunoprecipitation (CoIP) [11] [6] | Any (ex vivo) | Antibody-based purification of complexes | ++ | + | Confirming interactions in native context; complex isolation |

Protocol: Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay for Binary PPI Detection

Purpose: To detect direct physical interactions between two proteins of interest in an in vivo system [11] [6].

Reagents:

- Bait Plasmid: Expression vector with DNA-binding domain (BD) fused to Protein X

- Prey Plasmid: Expression vector with activation domain (AD) fused to Protein Y

- Yeast Reporter Strain: Typically AH109 or Y2HGold, with auxotrophic markers (e.g., HIS3, ADE2) under control of Gal4-responsive promoters

- SD Media: Synthetic defined media lacking specific amino acids for selection

Procedure:

- Clone genes of interest: Fuse cDNA of Protein X to the Gal4-BD in the bait plasmid and cDNA of Protein Y to the Gal4-AD in the prey plasmid. Verify constructs by sequencing.

- Co-transform yeast: Introduce both bait and prey plasmids into the yeast reporter strain using the lithium acetate method. Include positive control (known interacting pair) and negative controls (empty vector + prey, bait + empty vector).

- Plate transformations: Plate transformed yeast on SD media lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD -Leu -Trp) to select for presence of both plasmids. Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days.

- Test for interactions: Patch growing colonies onto SD media lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine (SD -Leu -Trp -His) to test for interaction-dependent reporter gene activation. Include stricter selection (SD -Ade) for stronger confirmation.

- Validate with quantitative assays: Perform β-galactosidase liquid assays to quantify interaction strength when necessary.

Technical Notes:

- Autoactivation testing is crucial: the bait alone should not activate transcription.

- Verify protein expression by immunoblotting, especially for negative results.

- Y2H is unsuitable for proteins requiring post-translational modifications specific to the native organism or membrane proteins [11] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Interface Studies

| Category | Reagent/Solution | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Expression | Gal4-based Y2H vectors [11] | Creating bait and prey fusions for yeast two-hybrid | Choose appropriate DNA-binding and activation domains |

| Split-fluorescent protein tags (e.g., split-YFP) [11] | Visualizing PPIs via BiFC; assessing cellular localization | Irreversible complementation can capture transient interactions | |

| Detection & Reporting | Antibodies for Co-IP/Western [11] | Validating protein expression and complex purification | Specificity is critical; test with knockout controls if possible |

| Luciferase substrates (e.g., D-luciferin) [11] | Detecting reconstituted split-luciferase activity | Enables real-time, quantitative kinetic measurements | |

| Buffers & Media | Controlled pH buffers [7] | Studying pH dependence of PPIs | Mimics different subcellular compartments (e.g., lysosomal pH ~4.5) |

| Variation salt concentration buffers [7] | Probing electrostatic contributions to binding | Use ionic strength series (0-500 mM NaCl) to screen charge effects | |

| Computational Resources | PPI databases (e.g., IntAct, BioGRID) | Contextualizing discovered interactions | Annotate with known interactions and functional networks |

Application in Targeted Protein Degradation

Understanding PPI interface forces has direct applications in drug discovery, particularly in designing Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs). These bifunctional molecules link a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, forming a ternary complex that triggers target ubiquitination and degradation [9]. Recent research on SMARCA2–VHL complexes bound to different PROTACs reveals that conformational flexibility and "frustration" at the target-ligase interface correlate with cooperativity [9]. Interface frustration quantifies when interfacial residues adopt energetically suboptimal configurations, which appears to be a key factor in ternary complex stability and degradation efficiency [9].

The systematic analysis of electrostatics, hydrophobicity, and solvation effects provides a powerful framework for understanding and manipulating PPI interfaces. Integrating computational approaches with experimental validation allows researchers to decipher the molecular grammar of protein recognition. As demonstrated in cutting-edge applications like PROTAC design, quantifying these biophysical forces enables rational engineering of molecular interactions with therapeutic potential. The protocols and analyses presented here offer a foundation for comprehensive PPI interface characterization in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to nearly all biological processes, from signal transduction to gene regulation. Understanding the three-dimensional structural details of these interfaces is crucial for fundamental biology and applied drug discovery, as evidenced by successful PPI-targeting drugs like venetoclax (a BCL-2 inhibitor) and immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 [12]. For decades, structural biology has relied on two primary experimental techniques for high-resolution structure determination: X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). While these methods have provided invaluable insights, each presents significant bottlenecks that can hinder the efficient determination of biologically relevant PPI interfaces. This application note examines these limitations within the context of PPI research, providing researchers with a clear understanding of current methodological constraints and emerging solutions to overcome them.

Technical Bottlenecks in X-ray Crystallography

The Crystallization Hurdle

The primary bottleneck in X-ray crystallography is the absolute requirement for high-quality, diffraction-quality crystals. This process is entirely empirical, with no predictive methods to determine ideal crystallization conditions a priori [12]. The challenges are particularly pronounced for PPIs and certain protein classes:

- Membrane Proteins: Proteins embedded in lipid membranes, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), are difficult to crystallize due to their inherent instability in aqueous crystallization solvents [12] [13].

- Flexible Complexes: Protein complexes with flexible regions or large conformational dynamics often resist formation of a well-ordered crystalline lattice [13].

- Condition Optimization: Finding successful crystallization conditions requires rigorous empirical optimization of numerous parameters, including concentrations of salts and additives, pH, protein concentration, and temperature—a process that can be both time-consuming and resource-intensive [12].

Throughput and Temporal Resolution Challenges

Traditional crystallography provides a static snapshot, typically at cryogenic temperatures, which may not accurately represent physiological, dynamic states. While time-resolved methods have been developed, they come with substantial experimental burdens:

- High Crystal Consumption: Time-resolved serial crystallography at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) may consume between 10⁵ to 10⁹ crystals per time point to collect a complete dataset [14].

- Complex Instrumentation: These experiments often require specialized hardware integrated into the beamline and multiple personnel on site, limiting their broad adoption [14]. The growth in the number of biomolecular systems studied with these methods has consequently been slow [14].

Table 1: Key Limitations of X-ray Crystallography for PPI Studies

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on PPI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Empirical crystallization process | Low throughput; fails for many flexible complexes and membrane proteins |

| Rigorous optimization required | Time-consuming and resource-intensive | |

| Structural Dynamics | Static snapshot at cryogenic temperature | May not capture physiologically relevant conformations |

| Difficulty capturing transient states | Challenging to study binding kinetics and mechanism | |

| Time-Resolved Studies | Extremely high crystal consumption | Limits applicability to targets that produce vast crystal volumes |

| Complex instrumentation & data analysis | Not routinely accessible to most research groups |

Technical Bottlenecks in Cryo-Electron Microscopy

Sample Size and Preparation Constraints

While cryo-EM does not require crystallization, it introduces its own set of sample-related challenges that are particularly relevant for studying PPIs:

- Molecular Size Limitations: Large molecules provide more contrast and features in noisy images, making them easier to align and reconstruct. Although theoretical limits suggest proteins around 38 kDa are the smallest suitable targets, in practice, the majority of cryo-EM structures are of complexes significantly larger than 50 kDa [15]. This is problematic as many proteins of high therapeutic interest, such as KRAS (∼19 kDa), fall well below this threshold [15].

- Preferred Orientation: Proteins can adsorb to the cryo-EM grid in a limited number of orientations, a phenomenon known as "preferred orientation." This incomplete sampling of views can lead to reconstructed maps with missing or distorted structural information, potentially obscuring the details of an interaction interface [12].

Resolution and Interface Assessment Challenges

The resolution of a cryo-EM structure is not uniform and can be misleading when assessing the quality of a PPI interface.

- Local Resolution Variability: Many cryo-EM maps associated with a near-atomic global resolution contain regions at intermediate (∼4–8 Å) resolutions or even lower [16]. This is especially true for flexible regions, which often include the very loops and domains involved in forming protein-protein interfaces.

- Interface Modeling Errors: Several common scenarios in cryo-EM model building can lead to sub-optimal interface modeling [16]:

- Independent fitting of one chain at a time without considering interface geometry.

- Inaccurate map segmentation that fails to correctly identify boundaries between subunits.

- Application of symmetry operations from a single built protomer, which can propagate initial fitting errors.

These issues are often not captured by standard density-based validation scores, necessitating the development of complementary metrics like the machine learning-based Protein Interface-score (PI-score) to specifically assess the quality of interfaces [16].

Table 2: Key Limitations of Cryo-EM for PPI Studies

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on PPI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Low signal-to-noise for proteins < 50-100 kDa | Difficult to study small proteins and many individual PPI partners |

| Sample Behavior | Preferred orientation on grids | Can lead to distorted or missing structural information for interfaces |

| Data Quality | Local resolution variation | Interface regions may be poorly resolved despite good global resolution |

| Model Building | Inaccurate segmentation & fitting | Can introduce errors at the protein-protein interface that are hard to detect |

| Accessibility | Cost of high-end instrumentation (e.g., 300 kV TEM) | Puts atomic-resolution studies out of reach for some labs [12] |

Emerging Strategies and Experimental Protocols

To overcome the bottlenecks described, researchers are developing innovative strategies that combine traditional structural biology with new computational and biochemical approaches.

Protocol: Cryo-EM of Small Proteins via Coiled-Coil Fusion

This protocol outlines a method to determine the structure of small proteins by fusing them to a coiled-coil scaffold, as demonstrated for the oncogenic protein kRasG12C (19 kDa) [15].

1. Principle: Fusing a small protein target to a larger, rigid scaffold protein increases the particle's effective molecular weight and provides a rigid fiducial marker, facilitating particle alignment and high-resolution reconstruction in single-particle cryo-EM.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Target Protein Gene: The gene for the protein of interest (e.g., kRasG12C).

- Scaffold Gene: The gene for the coiled-coil motif APH2, which forms a stable dimer and is targeted by specific nanobodies [15].

- Expression System: An appropriate recombinant protein expression system (e.g., E. coli, insect cells).

- Nanobodies: Purified nanobodies (e.g., Nb26, Nb28, Nb30, Nb49) that bind the APH2 motif with high affinity [15].

- Standard Cryo-EM Supplies: Holey carbon grids, vitrification device (e.g., Vitrobot), liquid ethane.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Construct Design. Fuse the target protein (kRasG12C) to the APH2 motif using a continuous alpha-helical linker to ensure rigidity. The C-terminal helix of kRas is ideal for this fusion [15].

- Step 2: Protein Expression and Purification. Express and purify the fusion protein using standard affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Step 3: Complex Formation. Incubate the purified fusion protein with a several-fold molar excess of the chosen nanobody (e.g., Nb26 or Nb49) for 30-60 minutes on ice.

- Step 4: Vitrification. Apply the complex to a cryo-EM grid, blot to achieve a thin liquid film, and plunge-freeze into liquid ethane.

- Step 5: Data Collection and Processing. Collect a single-particle cryo-EM dataset on a high-end microscope. Use the large, rigid scaffold-nanobody complex for improved particle picking, alignment, and 3D reconstruction.

4. Expected Results: Application of this method to kRasG12C-APH2 in complex with nanobodies yielded a structure at 3.7 Å resolution, with the bound inhibitor drug MRTX849 and GDP clearly visible in the density map [15]. This demonstrates the method's utility for detailed structural analysis of small protein targets in a drug-bound state.

Protocol: Validating Cryo-EM Interfaces with PI-Score

This protocol describes the use of the Protein Interface-score (PI-score), a density-independent, machine learning-based metric, to assess the quality of protein-protein interfaces in cryo-EM derived models [16].

1. Principle: PI-score is trained on the features of protein-protein interfaces in high-resolution crystal structures. It evaluates interfaces in a cryo-EM model based on features like shape complementarity, number of polar/charged residues, and interface solvation energy to distinguish between native-like and sub-optimal interfaces, providing a crucial complementary validation to standard density-fitting scores [16].

2. Reagents and Software:

- Input Data: A cryo-EM-derived atomic model of a protein complex (in PDB format).

- Software/Web Server: Access to the PI-score tool, as described in the primary literature [16].

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Model Preparation. Prepare the atomic model of the assembly, ensuring all subunits of interest are present.

- Step 2: Interface Assignment. Run the model through the PI-score workflow, which will first assign interfaces using a distance-based threshold.

- Step 3: Feature Calculation. The tool will automatically compute various interface features, including:

- Interface surface area and shape complementarity.

- Number of hydrophobic, charged, and polar residues at the interface.

- Interface solvation energy.

- Step 4: Machine Learning Classification. The computed features are fed into a trained classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) to generate a PI-score for each interface.

- Step 5: Result Interpretation. Interfaces are flagged as potentially problematic if they are associated with a low PI-score, especially in intermediate-to-low resolution (worse than 4 Å) structures where density-based assessment may be less reliable [16].

4. Expected Results: A comprehensive assessment of all interfaces in the model. A combined score incorporating both PI-score and a fit-to-density score has shown high discriminatory power, helping to identify interfaces that may require further refinement [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced PPI Structural Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in PPI Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Coiled-Coil Scaffolds (e.g., APH2) | Provides a rigid, large fusion partner to facilitate particle alignment in cryo-EM. | Enabling high-resolution structure determination of small proteins like kRas [15]. |

| Nanobodies | Small, stable binding domains that can lock proteins in specific conformations and increase particle size. | Used as high-affinity binders to scaffold proteins (e.g., APH2) to aid cryo-EM [15]. |

| PI-Score Software | A machine learning-based metric for assessing the quality of protein-protein interfaces in structural models. | Validating interfaces in cryo-EM derived assemblies, complementing density-based scores [16]. |

| Microfocus X-ray Beams | Enables data collection from smaller crystals, expanding the range of crystallizable samples. | Serial crystallography at synchrotrons and XFELs [13] [17]. |

| Direct Electron Detectors | Key hardware improvement providing dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratios in cryo-EM. | Essential for achieving near-atomic resolution, as in the TRPV1 ion channel structure [13]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Experimental Pathway for PPI Structure Determination

The diagram below outlines the decision pathway and major bottlenecks a scientist faces when choosing a method to determine a PPI interface.

Cryo-EM Scaffold Fusion Strategy

This diagram illustrates the logic and components of the scaffold fusion strategy, a key method for overcoming the size limitation in cryo-EM.

Defining Major PPI Types: Stable and Transient Interactions

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually all cellular biological processes, including immunological responses, signal transduction, and cellular organization [18]. These interactions can be systematically classified based on their binding stability, duration, and functional requirements [18].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics that distinguish stable and transient PPIs.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Stable vs. Transient Protein-Protein Interactions

| Characteristic | Stable PPIs | Transient PPIs |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Stability & Duration | Strong, long-lasting complexes that remain intact over time [18] | Weak, short-lived interactions (seconds or less) that form and dissociate easily [19] [20] |

| Dissociation Constant (Kd) | High affinity (nanomolar range) [20] | Low affinity (micromolar range) [20] |

| Biological Roles | Form structural complexes; essential for permanent cellular machinery [18] | Crucial for signaling cascades, regulatory pathways, and protein trafficking [18] [20] |

| Example | Arc repressor dimer; Heterodimer of human cathepsin D [18] | Kinase-substrate interactions; Chaperone-substrate recognition [20] |

| Interface Properties | Typically larger, more hydrophobic interfaces [18] | Smaller interfaces, often involving Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs) [18] |

Beyond the stability-based classification, PPIs can also be categorized functionally as obligate or non-obligate [18]. In obligate interactions, the associating proteins are unstable in isolation and must form a permanent complex to function. In non-obligate interactions, the proteins are stable independently and may interact transiently or permanently under specific conditions [18].

The Critical Challenge of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

A significant portion of PPIs, particularly transient ones, involves intrinsically disordered proteins and regions (IDPs/IDRs) [21] [22]. IDRs are protein segments that lack a stable 3D structure under physiological conditions, yet are functionally crucial [23].

The prevalence of IDRs poses a major challenge for PPI research and drug discovery for several reasons:

- Structural Dynamics: IDRs are highly flexible and exist as dynamic structural ensembles, making them resistant to traditional structural biology methods like X-ray crystallography [23] [20].

- Prediction Difficulties: Conventional computational methods that rely on co-evolutionary information or defined binding sites often fail with IDRs due to their sequence heterogeneity and conformational flexibility [24] [22].

- Binding Mechanisms: Many IDRs undergo a process of "coupled folding and binding," where they acquire structure only upon interaction with their binding partner [23]. This makes predicting their interaction interfaces exceptionally difficult.

IDRs are especially prevalent and functionally important in transcription factors and proteins involved in signaling networks, making them attractive but challenging therapeutic targets [21] [23].

Experimental Protocols for PPI Investigation

A range of experimental methods is employed to study PPIs, each with its own strengths and limitations. The choice of method often depends on whether the interaction is stable or transient.

Table 2: Core Experimental Methods for Studying Stable and Transient PPIs

| Method | Principle | Suitable for Transient PPIs? | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | A genetic method where PPI reconstitutes a transcription factor, activating a reporter gene [25]. | Partially | High false positive rate; difficult for membrane proteins; interactions occur in nucleus, not native environment [25] [20]. |

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS/TAP-MS) | A bait protein with an affinity tag is expressed and purified from cell lysate, along with its interacting partners, which are identified by MS [25]. | Limited (can lose weak partners during washing) [20] | Requires stabilization (e.g., crosslinking) for transient PPIs; high false-positive rate from contaminants [25] [20]. |

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | An antibody specific to one protein is used to pull the entire protein complex out of a solution [18]. | Partially | Biased towards stable interactions; can miss weak, PTM-sensitive, or short-lived events [20]. |

| Crosslinking Techniques | Chemicals covalently bind proteins in close proximity, stabilizing transient or weak interactions for analysis [18] [25]. | Yes | Captures only a snapshot of the interaction; may disrupt the native protein state [20]. |

Figure 1: A workflow diagram showing common experimental methods for PPI investigation and their primary applications.

Detailed Protocol: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-IP is a widely used biochemical method to confirm physical protein interactions in a native cellular context [18].

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells using a non-denaturing lysis buffer to preserve native protein complexes.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody specific to the protein of interest (the "bait").

- Capture: Add Protein A/G-conjugated beads to the lysate-antibody mixture. The beads bind to the antibody, forming an insoluble complex.

- Wash: Pellet the beads by gentle centrifugation and wash multiple times with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound proteins ("bait" and "prey") from the beads using a low-pH buffer or SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Analysis: Analyze the eluate by:

- Western Blotting: To confirm the presence of a suspected interacting partner.

- Mass Spectrometry: To identify unknown interacting partners.

Key Considerations:

- Controls: Include appropriate controls (e.g., using a non-specific IgG antibody) to identify non-specific binding.

- Buffer Composition: The stringency of the lysis and wash buffers can be adjusted to preserve weak, transient interactions or to reduce background.

Computational Prediction and the Rise of Deep Learning

Computational methods have become indispensable for predicting PPIs at scale, filling gaps left by experimental limitations [20]. These methods fall into two main categories: homology-based methods and template-free machine learning methods [26].

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning are transforming the field [24] [27]. Key architectures include:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Represent protein structures as graphs, where nodes are residues and edges capture spatial relationships, ideal for learning structural features critical for binding [27].

- Transformers and Language Models: Leverage protein language models (e.g., ESM, ProtBERT) trained on millions of protein sequences to extract evolutionary information and semantic context directly from amino acid sequences [27].

A major frontier in computational PPI prediction is addressing the challenge of IDRs. Cutting-edge models like SpatPPI are specifically designed for this task [22]. SpatPPI is a geometric deep learning framework that uses predicted 3D structures from AlphaFold2. It represents proteins as graphs with edge attributes encoding spatial relationships and employs a customized graph self-attention network to dynamically adjust the conformational refinement of IDRs, guided by information from adjacent folded domains [22]. This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in predicting interactions involving IDRs (IDPPIs) [22].

Figure 2: An overview of computational approaches for PPI prediction, from traditional methods to modern deep learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful PPI research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for designing and executing PPI studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags (His-tag, FLAG-tag, TAP-tag) | Fused to a "bait" protein for purification from complex cell lysates using complementary beads [25]. | Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP)-tag reduces false positives via a two-step purification process [25]. |

| Co-IP Kits | Provide optimized buffers, Protein A/G beads, and protocols for efficient immunoprecipitation [18]. | Ensure compatibility with downstream analysis like SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. |

| Crosslinkers | Chemically stabilize transient, weak protein complexes in situ before cell lysis [18] [25]. | Choice of crosslinker (e.g., membrane-permeable, cleavable) depends on the experimental goal. |

| AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Database | Provides highly accurate predicted 3D protein structures for millions of proteins [24] [22]. | Serves as critical input for structure-based computational models, especially for proteins without solved structures. |

| PPI Benchmark Datasets (e.g., HuRI-IDP, STRING, BioGRID) | Curated collections of known and predicted PPIs for training computational models and benchmarking experiments [27] [22]. | The HuRI-IDP dataset is specifically designed for evaluating predictions involving disordered regions [22]. |

The Methodological Revolution: AI, Docking, and Template-Free Prediction

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental regulators of cellular functions, and understanding their three-dimensional structures is essential for elucidating biological mechanisms and designing therapeutic interventions [28]. Computational prediction of protein complex structures relies primarily on two distinct methodological paradigms: template-based docking and template-free (or de novo) rigid-body docking [29] [30]. Template-based methods leverage similarities to known complex structures in databases, while template-free docking explores the physicochemical complementarity between unbound protein structures without prior knowledge of analogous complexes [31]. Within the context of evaluating protein-protein interaction interfaces, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application domains of these "traditional workhorses" is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. This application note provides a structured comparison of these approaches, detailed experimental protocols, and practical guidance for their implementation in PPI research.

Performance Comparison and Method Selection

Performance Benchmarks

The performance of template-based and template-free docking methods has been systematically evaluated on standardized benchmarks. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from these assessments, illustrating the relative strengths of each approach under different conditions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking Methods on Standardized Benchmarks

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Success Rate (Top 10 predictions) | Key Performance Insights | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Docking | COTH, PRISM [29] | Varies with template availability; can outperform free docking when good templates exist [30]. | Better handles complexes involving conformational changes upon binding [29] [31]. | High sequence/structure similarity to known complexes. |

| Template-Free Rigid-Body Docking | ZDOCK, ClusPro, HDOCK [29] [30] | ~40% of targets yield an acceptable model [30]. | Superior sampling capability when allowed multiple predictions per complex [29]. | Novel complexes without good templates; enzyme-inhibitor complexes [29]. |

| Integrated/Hybrid Approach | DeepTAG, CoDock-Ligand [28] [32] | Outperforms individual methods in challenging benchmarks [28]. | Combines advantages of both paradigms; leverages machine learning for scoring. | Real-world scenarios with uncertain template quality. |

Guidelines for Method Selection

Choosing between template-based and template-free docking requires careful consideration of the target complex and available information.

- Favor Template-Based Docking When: A homologous complex structure with significant sequence similarity or a related interface architecture exists in databases like the PDB [30]. This approach is particularly effective for predicting complexes that involve conformational changes upon binding, as the template often encapsulates the bound conformation [29] [31].

- Favor Template-Free Docking When: No suitable templates are available, or the target complex is novel. This method is indispensable for exploring the full spectrum of potential binding modes and is particularly successful for enzyme-inhibitor complexes [29] [30]. Its performance is highest for rigid-body cases, where conformational change between unbound and bound states is minimal.

- Adopt an Integrated Strategy: For the highest likelihood of success, a combination of both methods is often superior. Template-based models can provide reliable starting points, which can then be refined using template-free sampling. Furthermore, using even poor-quality templates to focus or constrain a broader template-free docking search can yield better results than either method alone [30] [28].

The following decision pathway provides a visual guide for selecting the most appropriate docking strategy:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Template-Based Docking Using COTH

COTH is a threading-based method that requires only the amino acid sequences of the interacting proteins as input [29].

- Input Preparation: Obtain FASTA-formatted sequences for both partner proteins.

- Threading and Template Selection: Submit sequences to the COTH server. The algorithm threads both sequences simultaneously against a non-redundant library of complex templates. This generates a selection of potential binding mode templates.

- Monomer Structure Modeling: The server separately threads each monomer sequence against a library of monomer templates to generate structural models.

- Complex Assembly: The predicted monomer structures are superposed onto the selected complex templates to generate the final quaternary structure predictions.

- Filtering (Critical for Benchmarking): To avoid trivial sequence identity matches, exclude predictions where both monomers have >95% sequence identity to the complex template. The top 8 valid predictions are typically retained for analysis [29].

Protocol for Template-Free Docking Using ZDOCK

ZDOCK is a grid-based, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) accelerated algorithm for rigid-body docking [29].

- Input Preparation: Obtain 3D structures (PDB format) of both component proteins, preferably in their unbound states. Pre-process structures by removing water molecules and heteroatoms, and adding hydrogen atoms if required.

- Sampling the Search Space: Run ZDOCK with a 6° rotational sampling interval, which explores 54,000 unique orientations by systematically varying the three Euler angles. For each rotation, the best-scoring translation is identified.

- Initial Scoring and Ranking: The generated poses are ranked using the ZDOCK scoring function, which includes statistical potentials like IFACE [29].

- Post-Processing: The thousands of resulting predictions are typically clustered to identify consensus binding modes. The top models (e.g., top 10 or top 100) are selected for further analysis and validation.

Protocol for Integrated Docking in Practical Scenarios

For real-world applications where the best path is uncertain, an integrated protocol is recommended.

- Initial Template Search: Use HHpred or a similar tool to search for potential complex templates for each target chain. Apply a probability threshold (e.g., 50%) to filter templates [30].

- Parallel Docking Execution:

- Run a template-based method (e.g., PRISM or a homology modeling pipeline) using the identified templates.

- Simultaneously, run a template-free global docking calculation using a program like ZDOCK or ClusPro.

- Model Integration and Consensus Building: Compare the top predictions from both methods. Look for consensus in the binding interface location.

- Rescoring and Refinement: Submit all models (or a focused subset) to a machine learning-based or energy-based scoring function for re-ranking. Tools like GNINA (a CNN-based scorer) have been shown to improve the selection of near-native poses [32].

- Incorporation of Experimental Data: If available, use experimental data from site-directed mutagenesis, cross-linking mass spectrometry, or NMR to filter and validate the final models [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following reagents, software, and databases are essential for conducting rigorous protein-protein docking experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Docking

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Docking Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository of 3D structural data for proteins and complexes; used for template searching and method benchmarking. | https://www.rcsb.org/ [27] |

| BioLiP | Database | A curated database of protein-ligand interactions, useful for identifying biologically relevant binding templates. | https://zhanggroup.org/BioLiP/ [32] |

| ZDOCK | Software | A widely used algorithm for template-free, rigid-body protein-protein docking using FFT. | http://zdock.umassmed.edu/ [29] |

| COTH Server | Web Server | A template-based docking server that uses threading to predict complex structures from sequence. | Available as described in [29] |

| ClusPro Server | Web Server | A popular and robust server for protein-protein docking that performs sampling, clustering, and scoring. | https://cluspro.org/ [30] |

| GNINA | Software | A scoring function based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for re-ranking docking poses to identify near-native structures. | https://github.com/gnina/gnina [32] |

| DOCKGROUND | Database | A comprehensive resource providing benchmark sets for the development and validation of docking methods. | http://dockground.compbio.ku.edu [31] |

Workflow Visualization

The typical workflow for an integrated docking study, combining both template-based and template-free approaches, is summarized below. This pipeline highlights the parallel execution of both methods and the critical steps of consensus model generation and experimental validation.

The prediction of protein-protein interaction (PPI) interfaces has been revolutionized by the advent of end-to-end deep learning frameworks, most notably AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold 3. These systems represent a paradigm shift from traditional computational methods, which often relied on rigid-body docking, template-based modeling, or manually engineered features [33] [27]. AlphaFold 3, with its substantially updated diffusion-based architecture, demonstrates substantially improved accuracy over many previous specialized tools and achieves greater accuracy for protein-protein interactions compared to its predecessors [34]. This unified deep learning framework enables researchers to predict the joint structure of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues within a single model, moving beyond the limitations of specialized predictors that could only handle specific interaction types [34] [35].

The fundamental breakthrough lies in the ability to perform "fold and dock" simultaneously—predicting the tertiary structure of individual chains while also determining their quaternary arrangement. This approach has proven particularly powerful because it leverages co-evolutionary signals and structural patterns in a unified manner. Unlike traditional docking methodologies that treated proteins as rigid bodies or employed semi-flexible approaches with limited success rates, these end-to-end deep learning systems inherently handle the flexibility and interaction-induced structural rearrangements that characterize biological complexes [33]. The performance leap is quantitative and substantial; where classical docking methods achieved success rates of around 16-24% on standard benchmarks, AlphaFold-based approaches now achieve acceptable quality (DockQ ≥ 0.23) for 63-72% of dimers, representing a dramatic improvement in reliability and accuracy [33].

Architectural Evolution and Technical Foundations

Core Architectural Innovations

The evolutionary journey from AlphaFold-Multimer to AlphaFold 3 represents significant architectural innovations that enable their remarkable performance in PPI prediction. AlphaFold 3 introduces a substantially updated diffusion-based architecture that replaces the structure module of AlphaFold 2 [34]. This new diffusion module operates directly on raw atom coordinates without rotational frames or equivariant processing, using a relatively standard diffusion approach where the model is trained to receive "noised" atomic coordinates and predict the true coordinates [34]. This multiscale diffusion process allows the network to learn protein structure at various length scales—small noise levels emphasize local stereochemistry, while high noise levels emphasize large-scale structure. This architectural choice eliminates the need for carefully tuned stereochemical violation penalties and easily accommodates arbitrary chemical components [34].

The trunk architecture has also been streamlined. AlphaFold 3 reduces the amount of multiple-sequence alignment (MSA) processing by replacing the evoformer with a simpler pairformer module [34]. The system uses a much smaller and simpler MSA embedding block with only four blocks compared to the original evoformer, and the processing of the MSA representation uses an inexpensive pair-weighted averaging. Crucially, only the pair representation is used for later processing steps, with the MSA representation not being retained [34]. This architectural refinement improves data efficiency while maintaining high accuracy. The pairformer operates exclusively on the pair and single representations, with pair processing and the number of blocks (48) remaining largely unchanged from AlphaFold 2 [34].

Comparative Architecture Table

Table 1: Architectural Comparison Between AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold 3

| Architectural Component | AlphaFold-Multimer | AlphaFold 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Generation | Structure module operating on amino-acid-specific frames and side-chain torsion angles | Diffusion module predicting raw atom coordinates directly |

| MSA Processing | Evoformer-based with extensive MSA processing | Pairformer with reduced MSA processing (4 blocks) |

| Training Approach | Standard supervised learning | Diffusion-based training with cross-distillation |

| Chemical Scope | Primarily proteins | Proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, modified residues |

| Confidence Measures | pLDDT and PAE | pLDDT, PAE, and distance error matrix (PDE) |

| Handling of Symmetry | Limited implicit handling | Explicit permutation via mini-rollout procedure |

Training Methodology and Confidence Estimation

The training procedure for AlphaFold 3 incorporates several innovative elements to address challenges specific to complex biomolecular interactions. A notable challenge with generative diffusion approaches is their propensity for hallucination, where models may invent plausible-looking structure even in unstructured regions [34]. To counteract this effect, AlphaFold 3 uses a cross-distillation method that enriches training data with structures predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer, where unstructured regions typically appear as long extended loops rather than compact structures [34]. This approach "teaches" AF3 to mimic this behavior and greatly reduces hallucination.

Confidence estimation has also evolved significantly. Unlike AlphaFold 2, which directly regressed error in the output of the structure module during training, AlphaFold 3 employs a diffusion "rollout" procedure for full-structure prediction generation during training [34]. This predicted structure is used to permute symmetric ground-truth chains and ligands and compute performance metrics to train the confidence head. The system predicts modified pLDDT (per-residue confidence measure), PAE (predicted aligned error between residues), and additionally a PDE (distance error matrix), which represents error in the distance matrix of the predicted structure compared to the true structure [34].

Performance Benchmarks and Quantitative Assessment

Comparative Performance Across Methods

The performance leap afforded by end-to-end deep learning frameworks is most evident in quantitative benchmarks comparing them to traditional and specialized methods. In comprehensive evaluations, AlphaFold-based approaches consistently outperform previous state-of-the-art methods across multiple interaction types. AlphaFold 3 demonstrates far greater accuracy for protein-ligand interactions compared to state-of-the-art docking tools, much higher accuracy for protein-nucleic acid interactions compared to nucleic-acid-specific predictors, and substantially higher antibody-antigen prediction accuracy compared to AlphaFold-Multimer v.2.3 [34].

In direct benchmarking on heterodimeric protein complexes, the application of AlphaFold 2 with optimized multiple sequence alignments generated models with acceptable quality (DockQ ≥ 0.23) for 63% of dimers [33]. This performance significantly exceeded all other tested docking methods by a large margin. The recently developed AlphaFold-Multimer achieved even higher performance with a success rate of 72.2% [33]. It's important to note that these benchmarks represent a substantial improvement over traditional docking methods like GRAMM and template-based docking (TMdock interface), which achieved success rates of only 24.2% and similar ranges in comparative assessments [33].

Performance Metrics Table

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of PPI Prediction Methods

| Method | Success Rate (DockQ ≥ 0.23) | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking (Vina) | ~16% (Benchmark 5) | Fast computation; physics-inspired scoring | Poor performance without bound structures; limited flexibility handling |

| Fold and Dock (trRosetta) | 7% | Simultaneous folding and docking | Limited to proteins; requires optimal MSA depth |

| AlphaFold 2 with optimized MSAs | 63% | Leverages co-evolutionary signals; handles flexibility | Limited to protein complexes; requires substantial computational resources |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | 72.2% | Specifically trained for complexes; improved interface prediction | Trained on same data as test sets making direct comparison difficult |

| AlphaFold 3 | Substantially improved over AF-Multimer | Unified framework for multiple biomolecules; diffusion-based architecture | Details on specific protein-protein benchmarks not fully reported |

Confidence Metrics and Model Selection

A critical component of practical PPI prediction is the ability to distinguish accurate from inaccurate models. Research has demonstrated that a predicted DockQ score (pDockQ) derived from AlphaFold 2 outputs can effectively separate acceptable from incorrect models [33]. The pDockQ metric combines interface contacts with interface pLDDT (predicted local distance difference test) values, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.95 in receiver operating characteristic analysis [33]. This significantly outperforms individual metrics such as the number of unique interacting residues (AUC = 0.91), total number of interactions between Cβ atoms (AUC = 0.92), or average interface pLDDT (AUC = 0.88) alone [33].

Interestingly, the average pLDDT of the entire complex performs poorly at distinguishing correct from incorrect docking arrangements (AUC = 0.66), emphasizing that both single chains in a complex can be predicted accurately while their relative orientation remains incorrect [33]. This highlights the importance of interface-specific confidence metrics rather than relying on global structure quality estimates when assessing PPI predictions.

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Standard Protocol for PPI Prediction with AlphaFold

Input Preparation: For a typical PPI prediction experiment using AlphaFold-Multimer or AlphaFold 3, researchers should begin by compiling the amino acid sequences of the interacting proteins in FASTA format. The input can include polymer sequences, residue modifications, and for AlphaFold 3, ligand SMILES strings for complexes involving small molecules [34].

Multiple Sequence Alignment Generation: The quality of multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) significantly impacts prediction accuracy. The optimal protocol combines both paired and unpaired MSAs [33]. Paired MSAs are generated by identifying interacting protein pairs in databases, while unpaired MSAs follow the standard AlphaFold 2 protocol. Research has demonstrated that combining AF2 MSAs with paired MSAs increases performance from 45.0% to 57.8% success rates, suggesting that AlphaFold benefits from both larger and paired MSAs [33].

Model Selection and Configuration: When running predictions, employing multiple models (e.g., model1 to model5) and several recycles (typically 3-10) improves results. Benchmarking revealed that the original AF2 model1 outperforms the fine-tuned model1_ptm in most cases, and the difference between 10 recycles with one ensemble and three recycles with eight ensembles is minor across all MSAs and AF2 models [33]. Running five initializations with random seeds and ranking models using pDockQ scores increases success rates to 61.7-62.7% [33].

Output Analysis and Validation: The prediction output includes both structures and confidence metrics. For PPI assessment, focus on interface-specific metrics rather than global quality measures. The pDockQ score, calculated as 0.724 * (1 / (1 + exp(-0.1 * (x + 7.7)))) where x is the log of the number of product contacts multiplied by the average interface pLDDT, effectively discriminates correct from incorrect models [33]. Models with pDockQ > 0.23 have a high probability of being acceptable, while those with pDockQ > 0.49 are likely to be of medium or high quality [33].

Workflow Visualization

AlphaFold PPI Prediction Workflow

Advanced Protocol: Interface-Focused Prediction with PPI-ID

For large complexes or challenging targets, the PPI-ID tool provides an alternative strategy that can improve prediction quality and reduce computational demands [36]. This approach maps interaction domains and motifs onto molecular structures and filters for those sufficiently close to interact, enabling focused prediction on likely interaction interfaces.

Domain and Motif Identification: Using PPI-ID, researchers can identify protein interaction domains and short linear motifs (SLiMs) through the InterPro and ELM databases [36]. The tool accesses UniProt and InterPro APIs to fetch amino acid sequences from protein accession numbers and search sequences for protein domains, using regular expression searches to identify SLiMs [36].

Interface Prediction and Filtering: PPI-ID checks Pfam or ELM IDs against compiled domain-domain interaction (DDI) and domain-motif interaction (DMI) databases to determine whether pairs constitute potential interactions [36]. If a protein structure is available, the table of predicted DDIs/DMIs can be filtered for contact distance using the filterbydistance() function, which employs atom.selection() and cmap() functions from the bio3d library to select alpha carbons and determine whether DDIs/DMIs are within user-provided contact distance [36].

Focused AlphaFold Modeling: Once interaction interfaces are identified, researchers can limit AlphaFold-Multimer modeling to only the domains and motifs likely to interact. This approach decreases confounding molecular contacts and can produce higher quality models [36]. Validation with known dimers confirms high accuracy of this focused approach [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PPI Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software | Predicting structures of protein complexes | https://github.com/deepmind/alphafold |

| AlphaFold 3 | Software | Unified prediction of biomolecular complexes | https://alphafoldserver.com |

| PPI-ID | Web Tool | Mapping interaction domains/motifs and filtering interfaces | http://ppi-id.biosci.utexas.edu:7215/ |

| PLIP | Web Tool | Analyzing molecular interactions in protein structures | https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de |

| STRING Database | Database | Known and predicted protein-protein interactions | https://string-db.org/ |

| BioGRID | Database | Protein-protein and gene-gene interactions | https://thebiogrid.org/ |

| IntAct | Database | Protein interaction database | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/ |

| 3DID | Database | Domain-domain interactions from crystal structures | https://3did.irbbarcelona.org |

| ELM Database | Database | Eukaryotic linear motifs and domain-motif interactions | http://elm.eu.org |

Analysis and Validation Techniques

Interaction Profiling with PLIP

For validating and analyzing predicted PPIs, the Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) has been extended to handle protein-protein interactions [37]. PLIP detects eight types of non-covalent interactions: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, water bridges, salt bridges, metal complexes, π-stacking, π-cation interactions, and halogen bonds [37]. While originally focused on small molecules, DNA, and RNA interactions, PLIP now incorporates PPI analysis, enabling researchers to compare interaction patterns between predicted and experimental structures.

In PPI analysis, PLIP reveals that hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, water bridges, and salt bridges are the most abundant interactions at 37%, 28%, 11%, and 10% respectively, followed by metal complexes, π-stacking, π-cation interactions, and halogen bonds at 9%, 3%, 1%, and 0.2% [37]. A key application is comparing interaction patterns of small-molecule inhibitors with native PPIs. For example, PLIP analysis shows how the cancer drug venetoclax mimics the native interaction between Bcl-2 and BAX, with critical overlap in interaction profiles [37]. The Bcl-2 residues Phe104, Tyr108, Asp111, Asn143, Trp144, Gly145, Arg146, and Phe153 are common to both BAX and venetoclax binding, with both engaging a hydrophobic groove formed by Phe104, Tyr108, and Phe153 via hydrophobic interactions [37].

Surface-Based Comparison with PPI-Surfer

For characterizing and comparing PPI interfaces, PPI-Surfer provides a novel method that quantifies similarity of local surface regions using three-dimensional Zernike descriptors (3DZD) [10]. This approach represents a PPI surface with overlapping surface patches, each described with a 3DZD—a compact mathematical representation of 3D function that captures both shape and physicochemical properties of the protein surface [10].

PPI-Surfer enables researchers to identify similar potential drug binding regions that don't share sequence or structure similarity, which is particularly valuable for drug discovery targeting PPIs [10]. Unlike traditional small-molecule binding sites, PPI interfaces tend to be larger, flater, and more hydrophobic, with drugs targeting PPIs (SMPPIIs) following the "rule of four" rather than Lipinski's rule of five [10]. These SMPPIIs tend to have molecular weight higher than 400 Da, logP higher than four, more than four rings, and more than four hydrogen-bond acceptors [10].

Validation Workflow

PPI Prediction Validation Pipeline

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Tissue-Specific Interaction Prediction

Recent advances have enabled the development of tissue-specific protein association atlases, compiled from protein abundance data of thousands of proteomic samples across human tissues [38]. These resources demonstrate that over 25% of protein associations are tissue-specific, with less than 7% of these specificities attributable to differences in gene expression alone [38]. This has profound implications for PPI prediction and validation, as interactions may be context-dependent.

For disease research, particularly neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, brain-specific protein association networks have proven valuable for functionally prioritizing candidate disease genes in loci linked to brain disorders [38]. Researchers can now construct tissue-specific interaction networks for disease-related genes, enabling more accurate interpretation of how mutations might disrupt specific interactions in relevant cellular contexts.

Language Model Approaches for Interaction Prediction

Beyond structure prediction, protein language models (PLMs) are being extended to predict PPIs directly from sequence. PLM-interact represents a novel approach that goes beyond using pre-trained PLM feature sets by jointly encoding protein pairs to learn their relationships, analogous to the next-sentence prediction task from natural language processing [39]. This method achieves state-of-the-art performance in cross-species PPI prediction benchmarks, with significant improvements over previous approaches when trained on human data and tested on mouse, fly, worm, E. coli, and yeast [39].

Additionally, fine-tuned versions of PLM-interact can detect mutation effects on interactions, leveraging mutation data from resources like IntAct to predict whether mutations increase or decrease interaction rates or binding strength [39]. This capability is particularly valuable for interpreting variants of unknown significance and understanding how disease-associated mutations disrupt normal PPI networks.

De Novo Interaction Prediction and Design

Perhaps the most exciting frontier is the prediction of de novo PPIs—interactions with no precedence in nature [40]. While AlphaFold-based methods excel at predicting endogenous interactions with an evolutionary trace, their performance drops for interactions without natural precedence [40]. Novel algorithms are being developed to explicitly tackle de novo interactions, including approaches based on protein-protein co-folding, graph-based atomistic models, and methods that learn from molecular surfaces [40].

These capabilities open broad applications in biotechnology, from drug discovery using molecular glues that rewire cellular function to protein engineering [40]. The prediction of antibody-antigen complexes and molecular glue-induced PPIs represents particularly promising applications that could transform therapeutic development [40]. As these methods mature, researchers will increasingly be able to not only predict natural interactions but design novel ones for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to cellular processes, and their dysregulation is linked to diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [41]. While traditional computational methods often relied on template-based modeling or rigid-body docking, these approaches are limited by the sparse coverage of known complex structures in databases; templates cover less than 1% of the estimated human interactome [28]. Hot-spot driven prediction represents a paradigm shift, focusing instead on identifying a small subset of critical residues, known as hot spots, which contribute the majority of the binding free energy in a protein interface [42]. This approach sidesteps the dependency on pre-existing templates, enabling the prediction of complexes for which no homologous structure exists. Artificial intelligence is now breaking through the limits of traditional methods by leveraging these molecular insights to achieve unprecedented accuracy in PPI structure prediction [28].

The Conceptual Workflow of Hot-Spot Driven Prediction

The template-free prediction workflow is fundamentally different from template-based methods. It does not search for a matching scaffold in a database of known complexes. Instead, it follows a multi-stage process that prioritizes biophysical principles and machine learning to assemble a plausible complex structure based on the properties of the individual protein monomers. The core steps of this workflow are visualized in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: The core workflow of a template-free, hot-spot driven PPI prediction method.

Workflow Stage Descriptions

- Hot-Spot Identification: The process begins by scanning the surface of each input protein monomer to locate regions with properties conducive to binding. These properties include residue size, hydrophobicity, charge potential, and solvent exposure [28]. Residues whose mutation causes a significant drop in binding free energy are considered hot spots [41]. Tools like PPI-hotspotID can perform this step using only the free protein structure, leveraging features such as residue conservation, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and gas-phase energy [41].

- Hot-Spot Matching: Identified hot spots on one protein are geometrically and chemically matched with complementary regions on the binding partner. This step defines a limited set of candidate orientations for the two proteins.

- Candidate Interface Generation: For each matched pair of hot spots, a candidate interface is constructed. A contact matrix is built for each candidate, describing which residues from protein A are within binding distance of residues on protein B [28].

- ML-Based Interface Scoring: A machine learning model, trained on residue-residue contacts from folded domains, scores each candidate interaction matrix for its predicted binding energy [28]. This is a critical step where AI evaluates the biological plausibility of the proposed interface.

- Complex Assembly and Refinement: The best-scored interface is used as a anchor point, and the full complex structure is built around it. The final assembly is often refined and tested for stability using methods like molecular dynamics simulations [28].

Key Methods and Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: PPI-HotspotID for Hot-Spot Detection

Objective: To identify protein-protein interaction hot spot residues from a single free protein structure using the PPI-hotspotID method [41].

Materials:

- Input: A 3D structure of a protein in PDB format.