Exploratory Data Analysis for Proteomics: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) for proteomics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Exploratory Data Analysis for Proteomics: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

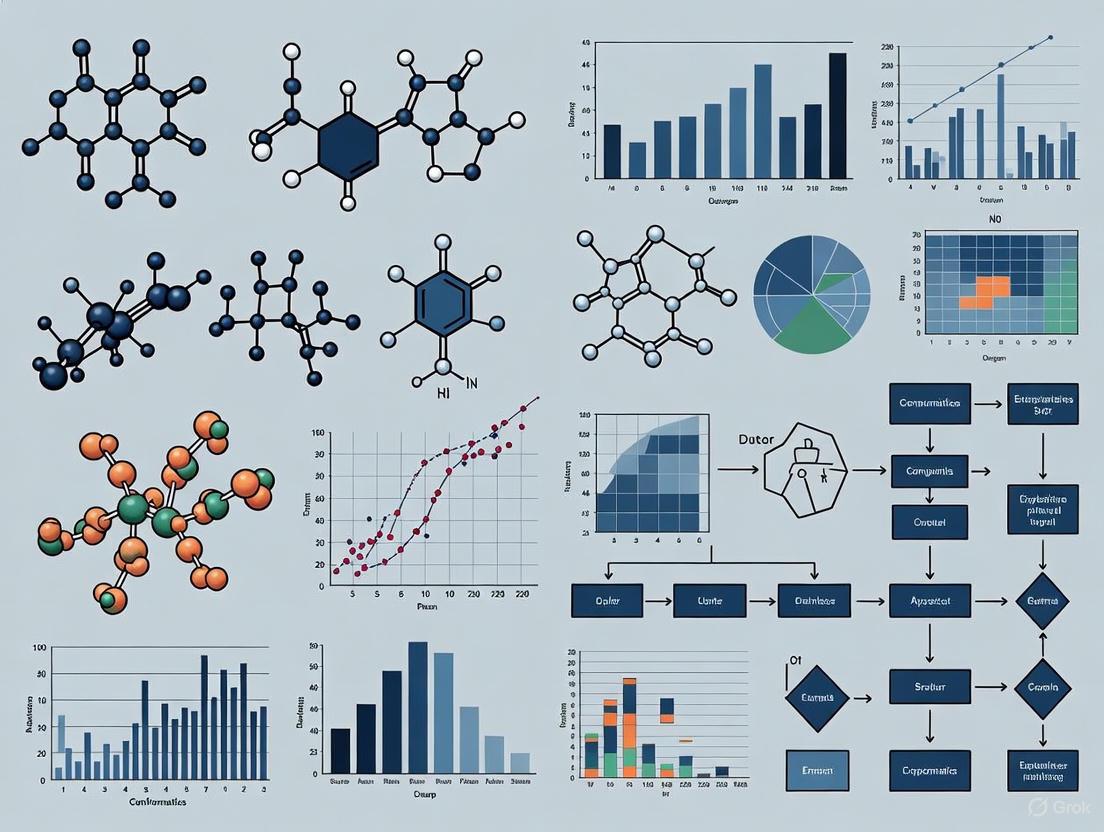

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) for proteomics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational role of EDA in uncovering patterns and ensuring data quality in high-dimensional protein datasets. The guide details practical methodologies, from essential visualizations to advanced spatial and single-cell techniques, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it explores validation strategies and the integration of proteomics with other omics data, illustrating these concepts with real-world case studies from current 2025 research to empower robust, data-driven discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Visual Tools for Proteomic EDA

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is a fundamental, critical step in proteomics research that provides the initial examination of complex datasets before formal statistical modeling or hypothesis testing. In the context of proteomics, EDA refers to the methodological approaches used to gain a comprehensive overview of proteomic data, identify patterns, detect anomalies, check assumptions, and assess technical artifacts that could impact downstream analyses [1] [2]. The primary goal of EDA is to enable researchers to understand the underlying structure of their data, evaluate data quality, and generate informed biological hypotheses for further investigation.

The importance of EDA is particularly pronounced in proteomics due to the inherent complexity of mass spectrometry-based data, which is characterized by high dimensionality, technical variability, and frequently limited sample sizes [3]. Proteomics data presents unique challenges, including missing values, batch effects, and the need to distinguish biological signals from technical noise. Through rigorous EDA, researchers can identify potential batch effects, assess the need for normalization, detect outlier samples, and determine whether samples cluster according to expected experimental groups [1] [2]. This process is indispensable for ensuring that subsequent statistical analyses and biological interpretations are based on reliable, high-quality data.

Core Principles and Significance of EDA

EDA in proteomics operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from confirmatory data analysis. It emphasizes visualization techniques that allow researchers to intuitively grasp complex data relationships, employs quantitative measures to assess data quality and structure, and maintains an iterative approach where initial findings inform subsequent analytical steps [2]. This process is inherently flexible, allowing researchers to adapt their analytical strategies based on what the data reveals rather than strictly testing pre-specified hypotheses.

The significance of EDA extends throughout the proteomics workflow. In the initial phases, EDA helps verify that experimental designs have been properly executed and that data quality meets expected standards. Before normalization and statistical testing, EDA can identify technical biases that require correction [2]. Perhaps most importantly, EDA serves as a powerful hypothesis generation engine, revealing unexpected patterns, relationships, or subgroups within the data that may warrant targeted investigation [2] [4]. This is particularly valuable in discovery-phase proteomics, where the goal is often to identify novel protein signatures or biological mechanisms without strong prior expectations.

In clinical proteomics, where sample sizes are often limited but the number of measured proteins is large (creating a "large p, small n" problem), EDA becomes essential for understanding the data structure and informing appropriate analytical strategies [3]. As proteomics technologies advance, enabling the simultaneous quantification of thousands of proteins across hundreds of samples, EDA provides the crucial framework for transforming raw data into biologically meaningful insights [5].

Key EDA Techniques and Visualizations in Proteomics

Data Quality Assessment and Preprocessing

The initial stage of EDA in proteomics focuses on assessing data quality and preparing datasets for downstream analysis. This begins with fundamental descriptive statistics that summarize the overall data output, including the number of identified spectra, peptides, and proteins [6]. Researchers typically examine missing value patterns, as excessive missingness may indicate technical issues with protein detection or quantification. Reproducibility assessment using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient evaluates the consistency between biological or technical replicates, with values closer to 1 indicating stronger correlation and better experimental reproducibility [6].

Data visualization plays a crucial role in quality assessment. Violin plots combine features of box plots and density plots to show the complete distribution of protein expression values, providing more detailed information about the shape and variability of the data compared to traditional box plots [2]. Bar charts are employed to represent associations between numeric variables (e.g., protein abundance) and categorical variables (e.g., experimental groups), allowing quick comparisons across conditions [2].

Table 1: Key Visualizations for Proteomics Data Quality Assessment

| Visualization Type | Primary Purpose | Key Components | Interpretation Guidance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violin Plot | Display full distribution of protein expression | Density estimate, median, quartiles | Wider sections show higher probability density; compare shapes across groups | ||

| Box Plot | Summarize central tendency and spread | Median, quartiles, potential outliers | Look for symmetric boxes; points outside whiskers may be outliers | ||

| Correlation Plot | Assess replicate reproducibility | Pearson's R values, scatter points | R | near 1 indicates strong reproducibility | |

| Bar Chart | Compare protein levels across categories | Rectangular bars with length proportional to values | Compare bar heights across experimental conditions |

Dimensionality Reduction Methods

Dimensionality reduction techniques are essential EDA tools for visualizing and understanding the overall structure of high-dimensional proteomics data. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is one of the most widely used methods, transforming the original variables (protein abundances) into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components that capture decreasing amounts of variance in the data [2] [6]. PCA allows researchers to visualize the global structure of proteomics data in two or three dimensions, revealing whether samples cluster according to experimental groups, identifying potential outliers, and detecting batch effects [2].

More advanced dimensionality reduction methods are increasingly being applied in proteomics EDA. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) are particularly valuable for capturing non-linear relationships in complex datasets [7] [4]. These methods create low-dimensional embeddings that preserve local data structure, often revealing subtle patterns or subgroups that might be missed by PCA. In practice, UMAP often provides better preservation of global data structure compared to t-SNE while maintaining computational efficiency [7].

The application of these methods is well-illustrated by research on ocean world analog mass spectrometry, where both PCA and UMAP were compared for transforming high-dimensional mass spectrometry data into lower-dimensional spaces to identify data-driven clusters that mapped to experimental conditions such as seawater composition and CO2 concentration [7]. This comparative approach to dimensionality reduction represents a robust EDA strategy for uncovering biologically meaningful patterns in complex proteomics data.

Clustering and Pattern Discovery

Clustering techniques complement dimensionality reduction by objectively identifying groups of samples or proteins with similar expression patterns. K-means clustering and Gaussian mixture models are commonly applied to proteomics data to discover inherent subgroups within samples that may correspond to distinct biological states or experimental conditions [3]. When applied to proteins rather than samples, clustering can reveal co-expressed protein groups that may participate in related biological processes or pathways.

Heatmaps coupled with hierarchical clustering provide a powerful visual integration of clustering results and expression patterns [2]. Heatmaps represent protein expression values using a color scale, with rows typically corresponding to proteins and columns to samples. The arrangement of rows and columns is determined by hierarchical clustering, grouping similar proteins and similar samples together. This visualization allows researchers to simultaneously observe expression patterns across thousands of proteins and identify clusters of proteins with similar expression profiles across experimental conditions [2].

More specialized clustering approaches have been developed specifically for mass spectrometry data. Molecular networking uses pairwise spectral similarities to construct groups of related mass spectra, creating "molecular families" that may share structural features [4]. Tools like specXplore provide interactive environments for exploring these complex spectral similarity networks, allowing researchers to adjust similarity thresholds and visualize connectivity patterns that might indicate structurally related compounds [4].

Essential Tools and Platforms for Proteomics EDA

Computational Frameworks and Machine Learning Platforms

The complexity of proteomics EDA has driven the development of specialized computational tools that streamline analytical workflows while maintaining methodological rigor. OmicLearn is an open-source, browser-based machine learning platform specifically designed for proteomics and other omics data types [5]. Built on Python's scikit-learn and XGBoost libraries, OmicLearn provides an accessible interface for exploring machine learning approaches without requiring programming expertise. The platform enables rapid assessment of various classification algorithms, feature selection methods, and preprocessing strategies, making advanced analytical techniques accessible to experimental researchers [5].

For mass spectral data exploration, specXplore offers specialized functionality for interactive analysis of spectral similarity networks [4]. Unlike traditional molecular networking approaches that use global similarity thresholds, specXplore enables localized exploration of spectral relationships through interactive adjustment of connectivity parameters. The tool incorporates multiple similarity metrics (ms2deepscore, modified cosine scores, and spec2vec scores) and provides complementary visualizations including t-SNE embeddings, partial network drawings, similarity heatmaps, and fragmentation overview maps [4].

More general-purpose platforms like the Galaxy project provide server-based scientific workflow systems that make computational biology accessible to users without specialized bioinformatics training [5]. These platforms often include preconfigured tools for common proteomics EDA tasks such as PCA, clustering, and data visualization, enabling researchers to construct reproducible analytical pipelines through graphical interfaces rather than programming.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Proteomics Exploratory Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| OmicLearn | Machine learning for biomarker discovery | Browser-based, multiple algorithms, no coding required | Web server or local installation |

| specXplore | Mass spectral data exploration | Interactive similarity networks, multiple similarity metrics | Python package |

| MSnSet.utils | Proteomics data analysis in R | PCA visualization, data handling utilities | R package |

| Galaxy | General-purpose workflow system | Visual workflow building, reproducible analyses | Web server or local instance |

Functional Analysis and Biological Interpretation

Following initial data exploration and pattern discovery, EDA extends to biological interpretation through functional annotation and pathway analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis categorizes proteins based on molecular function, biological process, and cellular component, providing a standardized vocabulary for functional interpretation [6]. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database connects identified proteins to known metabolic pathways, genetic information processing systems, and environmental response mechanisms [6].

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis using databases like StringDB places differentially expressed proteins in the context of known biological networks, helping to identify key nodal proteins that may serve as regulatory hubs [6]. More advanced network analysis techniques, such as Weighted Protein Co-expression Network Analysis (WPCNA), adapt gene co-expression network methodologies to proteomics data, identifying modules of co-expressed proteins that may represent functional units or coordinated biological responses [6].

These functional analysis techniques transform lists of statistically significant proteins into biologically meaningful insights. For example, in a study of Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease, functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed plasma proteins revealed dysregulation of inflammatory and neurodevelopmental pathways, generating new hypotheses about disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [8]. This integration of statistical pattern discovery with biological context represents the culmination of the EDA process, where data-driven findings are translated into testable biological hypotheses.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Proteomics EDA Workflow

A comprehensive EDA protocol for proteomics data should follow a systematic sequence of analytical steps, beginning with data quality assessment and progressing through increasingly sophisticated exploratory techniques. The following workflow represents a robust, generalizable approach suitable for most mass spectrometry-based proteomics datasets:

Step 1: Data Input and Summary Statistics

- Load protein abundance data from mass spectrometry output (typically from platforms like MaxQuant, DIA-NN, or AlphaPept) [5]

- Generate summary statistics including number of identified proteins, number of quantified proteins, and missing value counts per sample

- Calculate basic distribution metrics (mean, median, variance) for protein abundances across samples

Step 2: Data Quality Assessment

- Perform reproducibility analysis using correlation coefficients between technical or biological replicates [6]

- Create violin plots or box plots to visualize distributions of protein abundances across samples

- Identify potential outlier samples using PCA or hierarchical clustering

Step 3: Dimensionality Reduction and Global Structure Analysis

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and create scores plots to visualize sample clustering [6]

- Calculate variance explained by each principal component to assess data dimensionality

- Optionally, apply additional dimensionality reduction methods (t-SNE, UMAP) for complex datasets [7]

- Annotate plots with experimental factors (e.g., treatment groups, batch information) to identify potential confounders

Step 4: Pattern Discovery through Clustering

- Apply k-means clustering or Gaussian mixture models to identify sample subgroups [3]

- Perform hierarchical clustering of both samples and proteins

- Visualize results using heatmaps with dendrograms [2]

Step 5: Biological Interpretation

- Conduct functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) on protein clusters or differential expression results [6]

- Perform protein-protein interaction network analysis using StringDB or similar databases [6]

- Integrate findings from multiple EDA approaches to generate coherent biological hypotheses

This workflow should be implemented iteratively, with findings at each step potentially informing additional, more targeted analyses. The entire process is greatly facilitated by tools like OmicLearn [5] or specialized R packages [1] that streamline the implementation of various EDA techniques.

Case Study: EDA in Down Syndrome Alzheimer's Research

A recent proteomics study investigating Alzheimer's disease in adults with Down syndrome (DS) provides an illustrative example of EDA in practice [8]. Researchers analyzed approximately 3,000 plasma proteins from 73 adults with DS and 15 euploid healthy controls using the Olink Explore 3072 platform. The EDA process began with quality assessment to ensure data quality and identify potential outliers. Dimensionality reduction using PCA revealed overall data structure and helped confirm that symptomatic and asymptomatic DS samples showed separable clustering patterns.

Differential expression analysis identified 253 differentially expressed proteins between DS and healthy controls, and 142 between symptomatic and asymptomatic DS individuals. Functional enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology and KEGG databases revealed dysregulation of inflammatory and neurodevelopmental pathways in symptomatic DS. The researchers further applied LASSO feature selection to identify 15 proteins as potential blood biomarkers for AD in the DS population [8]. This EDA-driven approach facilitated the generation of specific, testable hypotheses about disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets, demonstrating how comprehensive data exploration can translate complex proteomic measurements into biologically meaningful insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Proteomics EDA

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in EDA |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | LC-MS/MS systems, MASPEX | Generate raw proteomic data for exploration |

| Protein Quantification Technologies | SOMAScan assay, Olink Explore 3072 | Simultaneously measure hundreds to thousands of proteins |

| Data Processing Software | MaxQuant, DIA-NN, AlphaPept | Convert raw spectra to protein abundance matrices |

| Statistical Programming Environments | R, Python with pandas/NumPy | Data manipulation and statistical computation |

| Specialized Proteomics Packages | MSnSet.utils (R), matchms (Python) | Proteomics-specific data handling and analysis |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | scikit-learn, XGBoost | Implement classification and feature selection algorithms |

| Visualization Libraries | ggplot2 (R), Plotly (Python) | Create interactive plots and visualizations |

| Functional Annotation Databases | GO, KEGG, StringDB | Biological interpretation of protein lists |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Galaxy, OmicLearn | Accessible, web-based analysis interfaces |

Exploratory Data Analysis represents an indispensable phase in proteomics research that transforms raw spectral data into biological understanding. Through a systematic combination of visualization techniques, dimensionality reduction, clustering methods, and functional annotation, EDA enables researchers to assess data quality, identify patterns, detect outliers, and generate informed biological hypotheses. As proteomics technologies continue to advance, enabling the quantification of increasingly complex protein mixtures across larger sample sets, the role of EDA will only grow in importance.

The future of EDA in proteomics will likely be shaped by several emerging trends, including the development of more accessible computational tools that make sophisticated analyses available to non-specialists [5], the integration of machine learning approaches for pattern recognition in high-dimensional data [7] [5], and the implementation of automated exploration pipelines that can guide researchers through complex analytical decisions. By embracing these advancements while maintaining the fundamental principles of rigorous data exploration, proteomics researchers can maximize the biological insights gained from their experimental efforts, ultimately accelerating discoveries in basic biology and clinical translation.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is an essential step in any research analysis, serving as the foundation upon which robust statistical inference and model building are constructed [9]. In the field of proteomics, where high-throughput technologies generate complex, multidimensional data, EDA provides the critical first lens through which researchers can understand their datasets, recognize patterns, detect anomalies, and validate underlying assumptions [10] [11]. The primary aim of exploratory analysis is to examine data for distribution, outliers, and anomalies to direct specific testing of hypotheses [9]. It provides tools for hypothesis generation by visualizing and understanding data, usually through graphical representations that assist the natural pattern recognition capabilities of the analyst [9].

Within proteomics research, EDA has become indispensable due to the volume and complexity of data produced by modern mass spectrometry-based techniques [10]. As a means to explore, understand, and communicate data, visualization plays an essential role in high-throughput biology, often revealing patterns that descriptive statistics alone might obscure [10]. This technical guide examines the core methodologies of EDA within proteomics research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with structured approaches to maximize insight from their proteomic datasets.

Theoretical Foundations of EDA

Definition and Core Principles

Exploratory Data Analysis represents a philosophy and set of techniques for examining datasets without formal statistical modeling or inference, as originally articulated by Tukey in 1977 [9]. Loosely speaking, any method of looking at data that does not include formal statistical modeling and inference falls under the term EDA [9]. This approach stands in contrast to confirmatory data analysis, focusing instead on the open-ended exploration of data structure and patterns.

The objectives of EDA can be summarized as follows:

- Maximizing insight into the database structure and understanding the underlying data

- Visualizing potential relationships between variables, including direction and magnitude

- Detecting outliers and anomalies that differ significantly from other observations

- Developing parsimonious models and performing preliminary selection of appropriate statistical models

- Extracting and creating clinically relevant variables for further analysis [9]

Classification of EDA Techniques

EDA methods can be cross-classified along two primary dimensions: graphical versus non-graphical methods, and univariate versus multivariate methods [9]. Non-graphical methods involve calculating summary statistics and characteristics of the data, while graphical methods leverage visualizations to reveal patterns, trends, and relationships that might not be apparent through numerical summaries alone [9]. Similarly, univariate analysis examines single variables in isolation, while multivariate techniques explore relationships between multiple variables simultaneously.

Table 1: Classification of EDA Techniques with Proteomics Applications

| Technique Type | Non-graphical Methods | Graphical Methods | Proteomics Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Tabulation of frequency; Central tendency (mean, median); Spread (variance, IQR); Shape (skewness, kurtosis) [9] | Histograms; Density plots; Box plots [9] | Distribution of protein intensities; Quality control of expression values [12] |

| Multivariate | Cross-tabulation; Covariance; Correlation analysis [9] | Scatter plots; Heatmaps; PCA plots; MA plots [2] [10] | Batch effect detection; Sample clustering analysis; Intensity correlation between replicates [12] |

EDA Techniques and Workflows in Proteomics

Non-graphical EDA Methods

Non-graphical EDA methods provide the fundamental quantitative characteristics of proteomics data, offering initial insights into data quality and distribution before applying more complex visualization techniques.

Univariate Non-graphical Analysis

For quantitative proteomics data, characteristics of central tendency (arithmetic mean, median, mode), spread (variance, standard deviation, interquartile range), and distribution shape (skewness, kurtosis) provide crucial information about data quality [9]. The mean is calculated as the sum of all data points divided by the number of values, while the median represents the middle value in a sorted list and is more robust to extreme values and outliers [9].

The variance and standard deviation are particularly important in proteomics for understanding technical and biological variability. When calculated on sample data, the variance (s²) is obtained using the formula:

[s^2 = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})^2}{(n-1)}]

where (x_i) represents individual protein intensity measurements, (\bar{x}) is the sample mean, and n is the sample size [9]. The standard deviation (s) is simply the square root of the variance, expressed in the same units as the original measurements, making it more interpretable for intensity values [9].

For proteomics data, which often exhibits asymmetrical distributions or contains outliers, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are generally preferred over the mean and standard deviation [9]. The IQR is calculated as:

[IQR = Q3 - Q1]

where Q₁ and Q₃ represent the first and third quartiles of the data, respectively [9].

Multivariate Non-graphical Analysis

Covariance and correlation represent fundamental bivariate non-graphical EDA techniques for understanding relationships between different proteins or experimental conditions in proteomics datasets [9]. The covariance between two variables x and y (such as protein intensities from two different samples) is computed as:

[\text{cov}(x,y) = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})}{n-1}]

where (\bar{x}) and (\bar{y}) are the means of variables x and y, and n is the number of data points [9]. A positive covariance indicates that the variables tend to move in the same direction, while negative covariance suggests an inverse relationship.

Correlation, particularly Pearson's correlation coefficient, provides a scaled version of covariance that is independent of measurement units, making it invaluable for comparing relationships across different scales in proteomics data:

[\text{Cor}(x,y) = \frac{\text{Cov}(x,y)}{sx sy}]

where (sx) and (sy) are the sample standard deviations of x and y [9]. Correlation values range from -1 to 1, with values near these extremes indicating strong relationships.

Graphical EDA Methods

Graphical methods form the cornerstone of effective EDA, providing visual access to patterns and structures that might remain hidden in numerical summaries alone.

Univariate Graphical Techniques

Histograms represent one of the most useful univariate EDA techniques, allowing researchers to gain immediate insight into data distribution, central tendency, spread, modality, and outliers [9]. Histograms are bar plots of counts versus subgroups of an exposure variable, where each bar represents the frequency or proportion of cases for a range of values (bins) [9]. The choice of bin number heavily influences the histogram's appearance, with good practice suggesting experimentation with different values, generally between 10 and 50 bins [9].

Box plots (box-and-whisker plots) effectively highlight the central tendency, spread, and skewness of proteomics data [9]. These visualizations display the median (line inside the box), quartiles (box edges), and potential outliers (whiskers extending from the box), making them particularly valuable for comparing distributions across different experimental conditions or sample groups [2].

Violin plots combine the features of box plots with density plots, providing more detailed information about data distribution [2]. Instead of a simple box, violin plots feature a mirrored density plot on each side, with the width representing data density at different values [2]. This offers a more comprehensive view of distribution shape and variability compared to traditional box plots.

Multivariate Graphical Techniques

Scatter plots provide two-dimensional visualization of associations between two continuous variables, such as protein intensities between different experimental conditions [2]. In proteomics, scatter plots can reveal correlations, identify potential outliers, and highlight patterns in data distribution, such as co-expression relationships [2].

Heatmaps offer powerful visualization for proteomics data by representing numerical values on a color scale [2]. Typically used to display protein expression patterns across samples, heatmaps can be combined with hierarchical clustering to identify groups of proteins or samples with similar expression profiles [2]. This technique is particularly valuable for detecting sample groupings, batch effects, or expression patterns associated with experimental conditions.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) represents a dimensionality reduction method that visualizes the overall structure and patterns in high-dimensional proteomics datasets [2]. PCA transforms original variables into principal components—linear combinations that capture maximum variance in decreasing order [2]. In proteomics, PCA can determine whether samples cluster by experimental group and identify potential confounders or technical biases (e.g., batch effects) that require consideration in downstream analyses [2].

MA plots, originally developed for microarray data but now commonly employed in proteomics, visualize the relationship between intensity (average expression) and log2 fold-change between experimental conditions [10]. These plots help verify fundamental data properties, such as the absence of differential expression for most proteins (evidenced by points centered around the horizontal 0 line), while highlighting potentially differentially expressed proteins that deviate from this pattern [10].

EDA Workflow for Proteomics Data

A structured EDA workflow ensures comprehensive understanding of proteomics data before proceeding to formal statistical testing. The following diagram illustrates a recommended EDA workflow for proteomics research:

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Case Study: EDA in Differential Expression Analysis

Recent research has highlighted the critical importance of EDA in optimizing differential expression analysis (DEA) workflows for proteomics data. A comprehensive study evaluated 34,576 combinatoric experiments across 24 gold standard spike-in datasets to identify optimal workflows for maximizing accurate identification of differentially expressed proteins [12]. The research examined five key steps in DEA workflows: raw data quantification, expression matrix construction, matrix normalization, missing value imputation (MVI), and differential expression analysis [12].

The EDA process in this study revealed that optimal workflow performance could be accurately predicted using machine learning, with cross-validation F1 scores and Matthew's correlation coefficients surpassing 0.84 [12]. Furthermore, the analysis identified that specific steps in the workflow exerted varying levels of influence depending on the proteomics platform. For label-free DDA and TMT data, normalization and DEA statistical methods were most influential, while for label-free DIA data, the matrix type was equally important [12].

Table 2: High-Performing Methods in Proteomics Workflows Identified Through EDA

| Workflow Step | Recommended Methods | Performance Context | Methods to Avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalization | No normalization (for distribution correction not embedded in settings) [12] | Label-free DDA and TMT data | Simple global normalization without EDA validation |

| Missing Value Imputation | SeqKNN, Impseq, MinProb (probabilistic minimum) [12] | Label-free data | Simple mean/median imputation without considering missingness mechanism |

| Differential Expression Analysis | Advanced statistical methods (e.g., limma) [12] | All platforms | Simple statistical tools (ANOVA, SAM, t-test) [12] |

| Intensity Calculation | directLFQ, MaxLFQ [12] | Label-free data | Methods without intensity normalization |

EDA for Mass Spectrometry Data

In mass spectrometry-based proteomics, EDA techniques face unique challenges due to the high-dimensionality of spectral data and substantial technical noise [7]. Research has demonstrated the applicability of data science and unsupervised machine learning approaches for mass spectrometry data from planetary exploration, with direct relevance to proteomics [7]. These approaches include dimensionality reduction methods such as Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for transforming data from high-dimensional space to lower dimensions for visualization and pattern recognition [7].

Clustering algorithms represent another essential EDA tool for identifying data-driven groups in mass spectrometry data and mapping these clusters to experimental conditions [7]. Such data analysis and characterization efforts form critical first steps toward developing automated analysis pipelines that could prioritize data analysis based on scientific interest [7].

Protocol: EDA for Quality Assessment in Quantitative Proteomics

The following protocol provides a structured approach for implementing EDA in quantitative proteomics studies:

Step 1: Data Quality Assessment

- Calculate summary statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, IQR) for protein intensities across all samples

- Generate box plots or violin plots to visualize intensity distributions across samples

- Identify samples with abnormal intensity distributions that may indicate technical issues

Step 2: Distribution Analysis

- Plot histograms or density plots for intensity measurements to assess normality

- Apply statistical tests for normality (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk test) if formal testing is required

- Determine whether data transformation (e.g., log-transformation) is necessary for downstream analyses

Step 3: Outlier Detection

- Use box plots to identify potential outliers within samples

- Employ Z-scores or studentized residuals to detect outlier samples across the dataset

- Apply PCA to identify sample outliers in multidimensional space

Step 4: Correlation Structure Evaluation

- Calculate correlation coefficients between technical or biological replicates

- Generate scatter plots comparing replicate samples

- Create correlation heatmaps to visualize sample-to-sample relationships

Step 5: Multivariate Pattern Detection

- Perform PCA to identify major sources of variation in the dataset

- Visualize sample clustering in PCA space colored by experimental factors

- Create heatmaps with hierarchical clustering to identify patterns in protein expression

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of EDA in proteomics requires both wet-lab reagents for generating high-quality data and computational tools for analysis. The following table details key resources in the proteomics researcher's toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools for Proteomics EDA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in EDA |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Platforms | Fragpipe, MaxQuant, DIA-NN, Spectronaut [12] | Raw data processing and expression matrix construction for downstream EDA |

| Spike-in Standards | UPS1 (Universal Proteomics Standard 1) proteins [12] | Benchmarking data quality and evaluating technical variation through known quantities |

| Statistical Software | R/Bioconductor [10] | Comprehensive environment for implementing EDA techniques and visualizations |

| Specialized R Packages | MSnbase, isobar, limma, ggplot2, lattice [10] | Domain-specific visualization and analysis of proteomics data |

| Color Palettes | RColorBrewer [10] | Careful color selection for thematic maps to highlight data patterns effectively |

| Workflow Optimization | OpDEA [12] | Guided workflow selection based on EDA findings and benchmark performance |

Visualization Standards for Proteomics EDA

Effective visualization is paramount to successful EDA in proteomics. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected relationships between different EDA techniques and their applications in uncovering data patterns:

Exploratory Data Analysis represents a critical foundation for rigorous proteomics research, enabling researchers to understand complex datasets, identify potential issues, generate hypotheses, and guide subsequent analytical steps. Through systematic application of both non-graphical and graphical EDA techniques, proteomics researchers can maximize insight into their data, detect anomalies that might compromise downstream analyses, and uncover biologically meaningful patterns. The structured approaches and protocols outlined in this technical guide provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with essential methodologies for implementing comprehensive EDA within proteomics workflows. As proteomics technologies continue to evolve, producing increasingly complex and high-dimensional data, the role of EDA will only grow in importance for ensuring robust, reproducible, and biologically relevant research outcomes.

In the high-dimensional landscape of proteomics research, where mass spectrometry generates complex datasets with thousands of proteins and post-translational modifications, exploratory data analysis (EDA) serves as the critical first step for extracting biologically meaningful insights. This technical guide provides proteomics researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing four essential graphical tools—Principal Component Analysis (PCA), box plots, violin plots, and heatmaps—within a proteomics context. By integrating detailed methodologies, structured data summaries, and customized visualization workflows, we demonstrate how these techniques facilitate quality control, outlier detection, pattern recognition, and biomarker discovery in proteomic studies, ultimately accelerating translational research in precision oncology.

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has revolutionized cancer research by enabling large-scale profiling of proteins and post-translational modifications (PTMs) to identify critical alterations in cancer signaling pathways [13]. However, these datasets present significant analytical challenges due to their high dimensionality, technical noise, missing values, and biological heterogeneity. Typically, proteomics research focuses narrowly on using a limited number of datasets, hindering cross-study comparisons [14]. Exploratory data analysis addresses these challenges by providing visual and statistical methods to assess data quality, identify patterns, detect outliers, and generate hypotheses before applying complex machine learning algorithms or differential expression analyses.

The integration of EDA within proteomics workflows has been greatly enhanced by tools like OncoProExp, a Shiny-based interactive web application that supports interactive visualizations including PCA, hierarchical clustering, and heatmaps for proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses [13]. Such platforms underscore the importance of visualization in translating raw proteomic data into actionable biological insights, particularly for classifying cancer types from proteomic profiles and identifying proteins whose expression stratifies overall survival.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Visualization Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional proteomics data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving maximal variance. In proteomic applications, PCA identifies the dominant patterns of protein expression variation across samples, effectively visualizing sample stratification, batch effects, and outliers. The technique operates by computing eigenvectors (principal components) and eigenvalues from the covariance matrix of the standardized data, with the first PC capturing the greatest variance, the second PC capturing the next greatest orthogonal variance, and so on.

In proteomics implementations, PCA is typically applied to the top 1,000 most variable proteins or phosphoproteins, selected based on the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) to focus analysis on biologically relevant features [13]. Scree plots determine the number of principal components that explain most of the variance, guiding researchers in selecting appropriate dimensions for downstream analysis. The resulting PCA plots reveal natural clustering of tumor versus normal samples, technical artifacts, or subtype classifications, providing an intuitive visual assessment of data structure before formal statistical testing.

Box Plots and Violin Plots

Box plots and violin plots serve as distributional visualization tools for assessing protein expression patterns across experimental conditions or sample groups. The box plot summarizes five key statistics—minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum—providing a robust overview of central tendency, spread, and potential outliers. In proteomics, box plots effectively visualize expression distributions of specific proteins across multiple cancer types or between tumor and normal samples, facilitating rapid comparison of thousands of proteins.

Violin plots enhance traditional box plots by incorporating kernel density estimation, which visualizes the full probability density of the data at different values. This added information reveals multimodality, skewness, and other distributional characteristics that might be biologically significant but obscured in box plots. For proteomic data, which often exhibits complex mixture distributions due to cellular heterogeneity, violin plots provide superior insights into the underlying expression patterns, particularly when comparing post-translational modification states across experimental conditions.

Heatmaps

Heatmaps provide a rectangular grid-based visualization where colors represent values in a data matrix, typically with hierarchical clustering applied to both rows (proteins) and columns (samples). In proteomics, heatmaps effectively visualize expression patterns across large protein sets, revealing co-regulated protein clusters, sample subgroups, and functional associations. The top 1,000 most variable proteins are often selected for heatmap visualization to emphasize biologically relevant patterns, with color intensity representing normalized abundance values [13].

Effective heatmap construction requires careful consideration of color scale selection, with sequential color scales appropriate for expression values and diverging scales optimal for z-score normalized data. Data visualization research emphasizes that using two or more hues in sequential gradients increases color contrast between segments, making it easier for readers to distinguish between expression levels [15]. Heatmaps in proteomics are frequently combined with dendrograms from hierarchical clustering and annotation tracks showing sample metadata (e.g., cancer type, TNM stage, response to therapy) to integrate expression patterns with clinical variables.

Methodology and Implementation

Data Collection and Preprocessing for Proteomic Visualization

Proteome and phosphoproteome data require rigorous preprocessing before visualization to ensure analytical validity. The standard pipeline, as implemented in platforms like OncoProExp, includes several critical steps [13]:

- Data Quality Control: Exclusion of features with >50% missing values for proteome and >70% for phosphoproteome (user-adjustable thresholds).

- Missing Value Imputation: Application of Random Forest algorithm using missForest (v1.5 in R) with default parameters until convergence.

- Feature Identifier Mapping: Protein identifiers mapped to standardized gene symbols using the Ensembl database via the biomaRt package (v2.58.2).

- Gene-Level Summarization: When multiple phosphosites or protein entries map to the same gene, expression values are averaged to obtain a single gene-level representation.

- Filtering for Comparative Analysis: Retention of only those genes with at least 30% non-missing values in both tumor and normal conditions to ensure equivalent protein representation.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Proteomics Visualization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| CPTAC Datasets | Provides standardized, clinically annotated proteomic and phosphoproteomic data from cancer samples for method validation [13] |

| MaxQuant Software | Performs raw MS data processing, peak detection, and protein identification for downstream visualization [14] |

| R/biomaRt Package (v2.58.2) | Maps protein identifiers to standardized gene symbols enabling cross-dataset comparisons [13] |

| missForest Package (v1.5) | Implements Random Forest-based missing value imputation to handle sparse proteomic data [13] |

| Urban Institute R Theme | Applies consistent, publication-ready formatting to ggplot2 visualizations [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Visualization Generation

PCA Implementation Protocol:

- Input the top 1,000 most variable proteins or phosphoproteins selected by Median Absolute Deviation (MAD).

- Standardize the data matrix to mean-centered and unit variance.

- Compute covariance matrix and perform eigen decomposition.

- Generate scree plot to determine optimal number of components.

- Project samples onto the first 2-3 principal components.

- Visualize with sample coloring by experimental condition (tumor/normal) or cancer type.

Box Plot and Violin Plot Generation:

- Select target proteins of biological interest or randomly sample for quality assessment.

- Group samples by experimental condition, cancer type, or clinical variable.

- For box plots: Calculate quartiles, median, and outliers (typically defined as beyond 1.5×IQR).

- For violin plots: Compute kernel density estimates for each group with bandwidth selection.

- Plot distributions with appropriate axis labeling and group coloring.

Heatmap Construction Workflow:

- Select feature set (typically top 1,000 variable proteins or differentially expressed proteins).

- Apply row and column clustering using Euclidean distance and Ward's linkage method.

- Normalize expression values using z-score or min-max scaling.

- Select appropriate color palette (sequential for expression, diverging for z-scores).

- Add column annotations for sample metadata.

- Render heatmap with dendrograms and legend.

Technical Specifications and Parameters

Table 2: Technical Parameters for Proteomics Visualization Techniques

| Visualization Method | Key Parameters | Recommended Settings for Proteomics | Software Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Number of components, scaling method, variable selection | Top 1,000 MAD proteins, unit variance scaling, 2-3 components for visualization [13] | prcomp() R function, scikit-learn Python |

| Box Plots | Outlier definition, whisker length, grouping variable | 1.5×IQR outliers, default whiskers, group by condition/cancer type [13] | ggplot2 geom_boxplot(), seaborn.boxplot() |

| Violin Plots | Bandwidth, kernel type, plot orientation | Gaussian kernel, default bandwidth, vertical orientation [13] | ggplot2 geom_violin(), seaborn.violinplot() |

| Heatmaps | Clustering method, distance metric, color scale | Euclidean distance, Ward linkage, z-score normalization [13] | pheatmap R package, seaborn.clustermap() |

Application in Proteomics Research

Case Study: CPTAC Pan-Cancer Analysis

The Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) represents a comprehensive resource for applying visualization techniques to proteomic data. When analyzing CPTAC datasets covering eight cancer types (CCRCC, COAD, HNSCC, LSCC, LUAD, OV, PDAC, UCEC), PCA effectively reveals both expected and unexpected sample relationships [13]. For instance, PCA applied to clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC) proteomes consistently separates tumor and normal samples along the first principal component, while the second component may separate samples by grade or stage. Similarly, box plots and violin plots of specific protein expressions (e.g., metabolic enzymes in PDAC, kinase expressions in LUAD) reveal distributional differences between cancer types that inform subsequent biomarker validation.

In one demonstrated application, hierarchical clustering heatmaps of the top 1,000 most variable proteins across CPTAC datasets identified coherent protein clusters enriched for specific biological pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation complexes in CCRCC and extracellular matrix organization in HNSCC [13]. These visualizations facilitated the discovery of biologically relevant patterns while ensuring retention of critical details often overlooked when blind feature selection methods exclude proteins with minimal expressions or variances.

Integration with Machine Learning Workflows

Visualization techniques serve as critical components within broader machine learning frameworks for proteomics. Platforms like OncoProExp integrate PCA, box plots, and heatmaps with predictive models including Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to classify cancer types from proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiles [13]. In these implementations, PCA not only provides qualitative assessment of data structure but also serves as a feature engineering step, with principal components used as inputs to classification algorithms.

The interpretability of machine learning models in proteomics is enhanced through visualization integration. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) coupled with violin plots reveal feature importance distributions across sample classes, while heatmaps of SHAP values for individual protein-predictor combinations provide granular insights into model decisions [13]. This integrated approach achieves classification accuracy above 95% while maintaining biological interpretability—a critical consideration for translational applications in biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification.

Color Palette Selection for Accessible Visualizations

Effective visualization in proteomics requires careful color palette selection to ensure interpretability and accessibility. The recommended approach utilizes:

- Categorical Color Scales: For distinguishing cancer types or sample groups without intrinsic order, using hues with different lightnesses ensures they remain distinguishable in greyscale and for colorblind readers [15].

- Sequential Color Scales: For expression gradients in heatmaps, gradients from bright to dark using multiple hues (e.g., light yellow to dark blue) increase contrast between segments [15].

- Diverging Color Scales: For z-score normalized data, gradients with a neutral middle value (light gray) and contrasting hues at both extremes effectively represent negative and positive values [15].

Table 3: Color Application Guidelines for Proteomics Visualizations

| Visualization Type | Recommended Color Scale | Accessibility Considerations | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA Sample Plot | Categorical palette | Minimum 3:1 contrast ratio, distinct lightness values [15] | Grouping by cancer type or condition |

| Expression Distribution | Single hue with variations | Colorblind-safe palettes, pattern supplementation | Protein expression across sample groups |

| Heatmaps | Sequential or diverging scales | Avoid red-green scales, ensure luminance variation [15] | Protein expression matrix visualization |

| Annotation Tracks | Categorical with highlighting | Grey for de-emphasized categories ("no data") [15] | Sample metadata representation |

PCA, box plots, violin plots, and heatmaps represent foundational visualization techniques that transform complex proteomic datasets into biologically interpretable information. When implemented within structured preprocessing pipelines and integrated with machine learning workflows, these tools facilitate quality assessment, hypothesis generation, and biomarker discovery across diverse cancer types. As proteomics continues to evolve with increasing sample sizes and spatial resolution, these visualization methods will remain essential for exploratory analysis, ensuring that critical patterns in the data guide subsequent computational and experimental validation in translational research.

In the field of proteomics research, exploratory data analysis (EDA) serves as a critical first step in understanding large-scale datasets generated by mass spectrometry and other high-throughput technologies. The volume and complexity of proteomic data have grown exponentially in recent years, requiring robust analytical approaches to ensure data quality and biological validity [2]. EDA encompasses methods used to get an initial overview of datasets, helping researchers identify patterns, spot anomalies, confirm hypotheses, and check assumptions before proceeding with more complex statistical analyses [2]. Within this framework, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) has emerged as an indispensable tool for quality assessment, providing critical insights into data structure that can reveal both technical artifacts and meaningful biological patterns [17].

The fundamental challenge in proteomics data analysis lies in distinguishing true biological signals from unwanted technical variations. Batch effects, defined as unwanted technical variations resulting from differences in labs, pipelines, or processing batches, are particularly problematic in mass spectrometry-based proteomics [18]. These effects can confound analysis and lead to both false positives (proteins that are not differential being selected) and false negatives (proteins that are differential being overlooked) if not properly addressed [19]. Similarly, sample outliers—observations that deviate significantly from the overall pattern—can arise from technical failures during sample preparation or from true biological differences, requiring careful detection and evaluation [20]. Without systematic application of PCA-based quality assessment, technical artifacts can masquerade as biological signals, leading to spurious discoveries and irreproducible results [17].

This technical guide frames PCA within the broader context of exploratory data analysis techniques for proteomics research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodologies for detecting batch effects and sample outliers. By establishing principled workflows for PCA-based quality assessment, proteomics researchers can safeguard against misleading artifacts, preserve true biological signals, and enhance the reproducibility of their findings—an essential foundation for credible scientific discovery in both academic and clinical settings [17].

Theoretical Foundations of PCA in Proteomics

Mathematical Principles of PCA

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional proteomics data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving the most important patterns of variation. The mathematical foundation of PCA lies in eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix or singular value decomposition (SVD) of the standardized data matrix. Given a proteomics data matrix ( X ) with ( n ) samples (columns) and ( p ) proteins (rows), where each element ( x_{ij} ) represents the abundance of protein ( i ) in sample ( j ), PCA begins by centering and scaling the data to ensure all features contribute equally regardless of their original measurement scale [17]. The covariance matrix ( C ) is computed as:

[ C = \frac{1}{n-1} X^T X ]

The eigenvectors of this covariance matrix represent the principal components (PCs), which are orthogonal directions in feature space that capture decreasing amounts of variance in the data. The corresponding eigenvalues indicate the amount of variance explained by each principal component. The first principal component (PC1) captures the maximum variance in the data, followed by subsequent components in decreasing order of variance [2]. The transformation from the original data to the principal component space can be expressed as:

[ Y = X W ]

Where ( W ) is the matrix of eigenvectors and ( Y ) is the transformed data in principal component space. This transformation allows researchers to visualize the high-dimensional proteomics data in a two- or three-dimensional space defined by the first few principal components, making patterns, clusters, and outliers readily apparent.

PCA vs. Alternative Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

While PCA is the most widely used dimensionality reduction technique in proteomics quality assessment, researchers sometimes consider alternative approaches such as t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). However, PCA remains superior for quality assessment due to three key advantages [17]:

- Interpretability: PCA components are linear combinations of original features, allowing direct examination of which protein measurements drive batch effects or outliers.

- Parameter stability: PCA is deterministic and requires no hyperparameter tuning, while t-SNE and UMAP depend on hyperparameters that can be difficult to select appropriately and can significantly alter results.

- Quantitative assessment: PCA provides objective metrics through explained variance and statistical outlier detection, enabling reproducible decisions about sample retention.

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for Proteomics Quality Assessment

| Feature | PCA | t-SNE | UMAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Linear algebra (eigen decomposition) | Probability and divergence minimization | Topological data analysis |

| Deterministic Output | Yes | No | No |

| Hyperparameter Sensitivity | Low | High (perplexity, learning rate) | High (neighbors, min distance) |

| Preservation of Global Structure | Excellent | Poor | Good |

| Computational Efficiency | High for moderate datasets | Low for large datasets | Medium |

| Direct Component Interpretability | Yes | No | No |

PCA Workflow for Quality Assessment in Proteomics

Data Preprocessing for PCA

Proper data preprocessing is essential for meaningful PCA results in proteomics studies. The typical workflow begins with data cleaning to handle missing values, which are common in proteomics datasets due to proteins being missing not at random (MNAR). Common approaches include filtering out proteins with excessive missing values or employing imputation methods such as k-nearest neighbors or minimum value imputation. Next, data transformation is often necessary, as proteomics data from mass spectrometry typically exhibits right-skewed distributions. Log-transformation (usually log2) is routinely applied to make the data more symmetric and stabilize variance across the dynamic range of protein abundances [20]. Finally, data scaling is critical to ensure all proteins contribute equally to the PCA results. Unit variance scaling (z-score normalization) is commonly used, where each protein is centered to have mean zero and scaled to have standard deviation one [17]. This prevents highly abundant proteins from dominating the variance structure simply due to their larger numerical values.

PCA Computation and Visualization

The computation of PCA begins with the preprocessed data matrix, which is decomposed into principal components using efficient numerical algorithms. For large proteomics datasets containing tens of thousands of proteins and hundreds of samples, specialized computational approaches are often necessary to handle the scale while enabling robust and reproducible PCA [17]. The principal components are ordered by the amount of variance they explain in the dataset, with the first component capturing the maximum variance. A critical aspect of PCA interpretation is examining the variance explained by each component, which indicates how much of the total information in the original data is retained in each dimension. The scree plot provides a visual representation of the variance explained by each consecutive principal component, helping researchers decide how many components to retain for further analysis [2].

Visualization of PCA results typically involves creating PCA biplots where samples are projected onto the space defined by the first two or three principal components. In these plots, each point represents a sample, and the spatial arrangement reveals relationships between samples. Samples with similar protein expression profiles will cluster together, while unusual samples will appear as outliers. Coloring points by experimental groups or batch variables allows researchers to immediately assess whether the major sources of variation in the data correspond to biological factors of interest or technical artifacts [2] [17]. The direction and magnitude of the original variables (proteins) can also be represented as vectors in the same plot, showing which proteins contribute most to the separation of samples along each principal component.

Figure 1: PCA Workflow for Proteomics Data Quality Assessment

Detecting and Evaluating Batch Effects

Identifying Batch Effects in PCA Space

In PCA plots, batch effects are identified when samples cluster according to technical factors such as processing date, instrument type, or reagent lot rather than biological variables of interest [17]. These technical sources of variation can manifest as distinct clusters of samples in principal component space, often correlating with the first few principal components. For example, if samples processed in different batches form separate clusters in a PCA plot, this indicates that technical variation between batches is a major source of variance in the data, potentially obscuring biological signals [19]. Research has shown that batch effects are particularly problematic in mass spectrometry-based proteomics due to the complex multi-step protocols involving sample preparation, liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry analysis across multiple days, months, or even years [18] [19].

The confounding nature of batch effects becomes particularly severe when they are correlated with biological factors of interest. In such confounded designs, where biological groups are unevenly distributed across batches, it becomes challenging to distinguish whether the observed patterns in data are driven by biology or technical artifacts. PCA helps visualize these relationships by revealing whether separation between biological groups is consistent across batches or driven primarily by batch-specific technical variation [18]. When batch effects are present but not confounded with biological groups, samples from the same biological group should still cluster together within each batch cluster, whereas in confounded scenarios, biological groups and batch factors become inseparable in the principal component space.

Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

While visual inspection of PCA plots provides initial evidence of batch effects, quantitative metrics offer objective assessment of batch effect magnitude. Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) integrates PCA and variance components analysis to quantify the proportion of variance attributable to batch factors, biological factors of interest, and other sources of variation [18]. This approach provides a numerical summary of how much each factor contributes to the overall variance structure observed in the data. Another quantitative approach involves calculating the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on PCA results, which evaluates the resolution in differentiating known biological sample groups in the presence of technical variation [18].

Additional quantitative measures include calculating the coefficient of variation (CV) within technical replicates across different batches for each protein [18]. Proteins with high CVs across batches indicate features strongly affected by batch effects. For datasets with known truth, such as simulated data or reference materials, the Matthew's correlation coefficient (MCC) and Pearson correlation coefficient (RC) can be used to assess how much batch effects impact the identification of truly differentially expressed proteins [18]. These quantitative approaches provide objective criteria for determining whether batch effect correction is necessary and for evaluating the effectiveness of different correction strategies.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Batch Effects in Proteomics Data

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained by Batch | Proportion of variance in early PCs correlated with batch | Values >25% indicate strong batch effects | General use with known batch factors |

| Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) | Mixed linear model on principal components | Quantifies contributions of biological vs. technical factors | Studies with multiple known factors |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of biological to technical variance | Higher values indicate better separation of biological groups | Before/after batch correction |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Standard deviation/mean for replicate samples | Lower values after correction indicate improved precision | Technical replicate samples |

| Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Correlation between true and observed differential expression | Values closer to 1 indicate minimal batch confounding | Simulated data or reference materials |

Detecting and Evaluating Sample Outliers

Identifying Outliers in PCA Space

Sample outliers in proteomics data are observations that deviate significantly from the overall pattern of the distribution, potentially arising from technical artifacts or rare biological states [20]. In PCA space, outliers typically appear as isolated points distinctly separated from the main cluster of samples. The standard approach for outlier identification involves using multivariate standard deviation ellipses in PCA space, with common thresholds at 2.0 and 3.0 standard deviations, corresponding to approximately 95% and 99.7% of samples as "typical," respectively [17]. Samples outside these thresholds are flagged as potential outliers and should be carefully examined in the context of available metadata and experimental design.

It is important to distinguish between technical outliers resulting from experimental errors and biological outliers representing genuine rare biological phenomena. Technical outliers, caused by factors such as sample processing errors, instrument malfunctions, or data acquisition problems, typically impair statistical analysis and should be removed or downweighted [20]. In contrast, biological outliers may contain valuable information about previously unobserved biological mechanisms, such as rare cell states or unusual patient responses, and warrant further investigation rather than removal [20]. Examining whether outliers correlate with specific sample metadata (e.g., sample collection date, processing technician, or quality metrics) can help distinguish between these possibilities.

Robust PCA Methods for Outlier Detection

Classical PCA (cPCA) is sensitive to outlying observations, which can distort the principal components and make outlier detection unreliable. Robust PCA (rPCA) methods address this limitation by using statistical techniques that are resistant to the influence of outliers. Several rPCA algorithms have been developed, including PcaCov, PcaGrid, PcaHubert (ROBPCA), and PcaLocantore, all implemented in the rrcov R package [21]. These methods employ robust covariance estimation to obtain principal components that are not substantially influenced by outliers, enabling more accurate identification of anomalous observations.

Research comparing rPCA methods has demonstrated their effectiveness for outlier detection in omics data. In one study, PcaGrid achieved 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity in detecting outlier samples in both simulated and genuine RNA-seq datasets [21]. Another approach, the EnsMOD (Ensemble Methods for Outlier Detection) tool, incorporates multiple algorithms including hierarchical cluster analysis and robust PCA to identify sample outliers [20]. EnsMOD calculates how closely quantitation variation follows a normal distribution, plots density curves to visualize anomalies, performs hierarchical clustering to assess sample similarity, and applies rPCA to statistically test for outlier samples [20]. These robust methods are particularly valuable for proteomics studies with small sample sizes, where classical PCA may be unreliable due to the high dimensionality of the data with few biological replicates.

Figure 2: Outlier Detection and Decision Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Benchmarking Studies on Batch Effect Correction

Several comprehensive benchmarking studies have evaluated strategies for addressing batch effects in proteomics data. A recent large-scale study leveraged real-world multi-batch data from Quartet protein reference materials and simulated data to benchmark batch effect correction at precursor, peptide, and protein levels [18]. The researchers designed two scenarios—balanced (where sample groups are balanced across batches) and confounded (where batch effects are correlated with biological groups)—and evaluated three quantification methods (MaxLFQ, TopPep3, and iBAQ) combined with seven batch effect correction algorithms (ComBat, Median centering, Ratio, RUV-III-C, Harmony, WaveICA2.0, and NormAE) [18].

The findings revealed that protein-level correction was the most robust strategy overall, and that the quantification process interacts with batch effect correction algorithms [18]. Specifically, the MaxLFQ-Ratio combination demonstrated superior prediction performance when extended to large-scale data from 1,431 plasma samples of type 2 diabetes patients in Phase 3 clinical trials [18]. This case study highlights the importance of selecting appropriate correction strategies based on the specific data characteristics and analytical context, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach to batch effect correction.

Protein Complex-Based Analysis as Batch-Effect Resistant Method

An alternative approach to dealing with batch effects involves using batch-effect resistant methods that are inherently less sensitive to technical variations. Research has demonstrated that protein complex-based analysis exhibits strong resistance to batch effects without compromising data integrity [22]. Unlike conventional methods that analyze individual proteins, this approach incorporates prior knowledge about protein complexes from databases such as CORUM, analyzing proteins in functional groups rather than as individual entities [22].

The underlying rationale is that technical batch effects tend to affect individual proteins randomly, whereas true biological signals manifest coherently across multiple functionally related proteins. By analyzing groups of proteins that form complexes, the method amplifies biological signals while diluting technical noise [22]. Studies using both simulated and real proteomics data have shown that protein complex-based analysis maintains high differential selection reproducibility and prediction accuracy even in the presence of substantial batch effects, outperforming conventional single-protein analyses and avoiding potential artifacts introduced by batch effect correction procedures [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Quality Proteomics

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Quality Proteomics

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in Quality Assessment | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Biological standards | Multi-level quality control materials for benchmarking | [18] |

| SearchGUI & PeptideShaker | Computational tools | Protein identification from MS/MS data | [23] |

| rrcov R Package | Statistical software | Robust PCA methods for outlier detection | [21] |

| EnsMOD | Bioinformatics tool | Ensemble outlier detection using multiple algorithms | [20] |

| CORUM Database | Protein complex database | Reference for batch-effect resistant complex analysis | [22] |

| Immunoaffinity Depletion Columns | Chromatography resins | Remove high-abundance proteins to enhance dynamic range | [24] |

| TMT/iTRAQ Reagents | Chemical labels | Multiplexed sample analysis to reduce batch effects | [22] |

Principal Component Analysis serves as a powerful, interpretable, and scalable framework for assessing data quality in proteomics research. By systematically applying PCA-based workflows, researchers can identify batch effects and sample outliers that might otherwise compromise downstream analyses and biological interpretations. The integration of robust statistical methods with visualization techniques provides a comprehensive approach to quality assessment that balances quantitative rigor with practical interpretability. As proteomics continues to evolve as a critical technology in basic research and drug development, establishing standardized practices for PCA-based quality assessment will be essential for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of research findings. Future directions in this field will likely include the development of more sophisticated robust statistical methods, automated quality assessment pipelines, and integrated frameworks that combine multiple quality metrics for comprehensive data evaluation.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on exploratory data analysis (EDA) techniques for proteomics research, this guide addresses the critical practical application of these methods using the R programming language. EDA is an essential step before any formal statistical analysis, providing a big-picture view of the data and enabling the identification of potential outlier samples, batch effects, and overall data quality issues that require correction [1]. In mass spectrometry-based proteomics, where datasets are inherently high-dimensional and complex, EDA becomes indispensable for ensuring robust and interpretable results. This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with detailed methodologies for implementing EDA using popular R packages, complete with structured data summaries, experimental protocols, and mandatory visualizations to streamline analytical workflows in proteomic investigations.

The fundamental goal of EDA in proteomics is to transform raw quantitative data from mass spectrometry into actionable biological insights through a process of visualization, quality control, and initial hypothesis generation. This process typically involves assessing data distributions, evaluating reproducibility between replicates, identifying patterns of variation through dimensionality reduction, and detecting anomalies that might compromise downstream analyses. By employing a systematic EDA approach, researchers can make data-driven decisions about subsequent processing steps such as normalization, imputation, and statistical testing, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their proteomic findings [25].

Essential R Packages for Proteomics EDA

The R ecosystem offers several specialized packages for proteomics data analysis, each with unique strengths and applications. Selecting the appropriate package depends on factors such as data type (labeled or label-free), preferred workflow, and the specific analytical requirements of the study. The following table summarizes key packages instrumental for implementing EDA in proteomics.

Table 1: Essential R Packages for Proteomics Exploratory Data Analysis

| Package Name | Primary Focus | Key EDA Features | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| tidyproteomics [25] | Quantitative data analysis & visualization | Data normalization, imputation, quality control plots, abundance visualization | Output from MaxQuant, ProteomeDiscoverer, Skyline, DIA-NN |

| Bioconductor Workflow [26] | End-to-end data processing | Data import, pre-processing, quality control, differential expression | LFQ and TMT data; part of Bioconductor project |

| MSnSet.utils [1] | Utilities for MS data | PCA plots, sample clustering, outlier detection | Compatible with MSnSet objects |