From Data to Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Creating and Interpreting Gene Expression Heatmaps

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master gene expression heatmaps.

From Data to Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Creating and Interpreting Gene Expression Heatmaps

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to master gene expression heatmaps. It covers foundational principles—from interpreting color scales and dendrograms to understanding clustered heatmaps as a tool for identifying patterns in transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data. The guide delivers practical, step-by-step methodologies for creating heatmaps using both code-based tools like R/pheatmap and user-friendly web platforms like Heatmapper2 and Galaxy. It further addresses critical troubleshooting for common pitfalls in clustering and scaling, and offers best practices for validation and comparative analysis to ensure biological relevance and reproducibility, ultimately empowering readers to generate publication-quality visualizations.

Understanding Gene Expression Heatmaps: A Visual Language for Genomic Data

What is a Heatmap? Defining the Grid of Colors for Expression Data

A heatmap is a two-dimensional data visualization technique that represents the magnitude of individual values in a dataset using a grid of colored squares [1] [2]. In the context of gene expression research, this translates complex numerical matrices into an intuitive visual summary, where colors indicate up-regulation, down-regulation, or the abundance of transcripts across different samples or experimental conditions [2]. This transformation from numbers to colors allows researchers and drug development professionals to quickly grasp patterns, trends, and outliers that would be difficult to discern from raw data alone [3].

Core Principles and Data Structure

At its core, a heatmap is a graphical representation of data structured as a matrix, where each cell's color encodes a value [1] [3]. The axis variables (e.g., genes and samples) are divided into ranges, and each cell's color corresponds to the value of the main variable of interest for that specific combination [1].

Standard Data Format for Expression Analysis

Heatmap data can be structured in two primary formats, with the three-column format being particularly common in bioinformatics for its analytical flexibility.

Table 1: Common Data Structures for Heatmap Input

| Format Type | Description | Example from Gene Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix or Table Format | The first column holds values for one axis (e.g., Gene IDs). The remaining column headers represent the other axis (e.g., Sample Names). The intersecting cells contain the expression values [1]. | |

| Three-Column Format | Each row defines a single cell in the heatmap. The first two columns specify the 'coordinates' (e.g., Gene ID and Sample ID), and the third column specifies the value for that cell (e.g., log2 fold-change) [1]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Software

Creating a publication-quality heatmap requires a combination of specialized software tools and a understanding of core components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Heatmap Creation

| Item / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Analysis Environment | R (with ggplot2, pheatmap, ComplexHeatmap packages); Python (with Pandas, Seaborn, Matplotlib) | Provides the computational foundation for data normalization, transformation, and the statistical generation of the heatmap plot. Essential for handling large-scale genomic data [2] [3]. |

| Clustering Algorithms | Hierarchical Clustering; k-means | Used to group similar genes (rows) and/or samples (columns) together, revealing inherent biological patterns and relationships in the data [1] [2]. |

| Color Palettes | Sequential (viridis, plasma); Diverging (blue-white-red) | The core "reagent" for visualization. Sequential palettes show a progression from low to high values. Diverging palettes are critical for expression data to highlight deviation from a central value (e.g., zero fold-change) [1] [2]. |

| Data Matrix | Normalized Count Matrix (e.g., from RNA-seq); Log-Transformed Values; Z-scores | The primary input data. Normalization ensures comparability across samples. Log-transformation helps handle skewed data. Z-scoring (by row) allows for easy visualization of gene-wise variation [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Clustered Heatmap from RNA-seq Data

The following protocol details the key steps for creating a clustered heatmap, a standard in gene expression analysis.

The process of generating a heatmap from raw expression data involves a sequence of critical steps to ensure the final visualization is both accurate and biologically meaningful.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Begin with a raw count matrix from an RNA-seq experiment.

- Action: Normalize the raw read counts to account for differences in library size and RNA composition. Methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) or DESeq2's median-of-ratios are commonly used [2].

- Rationale: This ensures that expression levels are comparable across different samples.

Step 2: Data Transformation and Filtering

- Action: Apply a log² transformation to the normalized counts. This stabilizes the variance across the dynamic range of expression values, preventing a few highly expressed genes from dominating the color scale [2].

- Action: Filter genes to focus the analysis. This often involves selecting genes that show significant differential expression (e.g., based on an adjusted p-value) or those with the highest variance across samples to reveal the most meaningful patterns [2].

Step 3: Data Scaling and Clustering

- Action: Scale the data. Often, Z-scores are calculated by row (gene) to standardize expression values, meaning for each gene, the mean is subtracted and the value is divided by the standard deviation. This allows for easy visualization of which genes are expressed above or below their mean level in each sample [2].

- Action: Perform hierarchical clustering on the rows (genes) and/or columns (samples). This uses a distance metric (e.g., Euclidean distance) and a linkage method (e.g., Ward's method) to group entities with similar expression profiles [1] [2]. The result is a dendrogram that is displayed alongside the heatmap.

Step 4: Visualization and Color Mapping

- Action: Map the transformed and scaled numerical values to a color palette. For gene expression, a diverging palette (e.g., blue-white-red) is standard, with neutral colors (white) representing average expression, and saturated colors (blue, red) representing down-regulation and up-regulation, respectively [1] [2].

- Action: Generate the final plot, integrating the color grid, dendrograms, and axis labels. Include a legend to explicitly show how colors map to the numerical values [1].

Visualization Guidelines and Accessibility

Adhering to visual design best practices is crucial for creating interpretable and accessible heatmaps, especially in publications and presentations.

Color Palette Selection and Contrast

The choice of color palette is not merely aesthetic; it directly impacts the accuracy of data interpretation.

Table 3: Color Palette Specifications for Scientific Visualization

| Palette Type | Recommended Use | Example Hex Codes | Contrast Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | Displaying data that progresses from low to high values without an inherent midpoint (e.g., expression abundance). | #F1F3F4 (low) → #34A853 (high) |

Ensure extreme colors have sufficient contrast against background and labels. |

| Diverging | Displaying data with a critical central value, such as fold-change or Z-scores (common in expression heatmaps). | #4285F4 (low) → #FFFFFF (mid) → #EA4335 (high) |

The midpoint color (e.g., white) must be distinct from both ends. |

| Categorical | Highlighting different groups or states (e.g., gene ontologies). | #4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853 |

Adjacent colors should be easily distinguishable. |

- Include a Legend: A legend is vital for viewers to grasp the absolute values represented by the colors [1].

- Value Annotation: Where possible and not overly cluttering, annotate cells with their numerical values to provide precise information alongside the color encoding [1].

- Accessibility Compliance: For any non-text elements that convey information (e.g., color bars in a legend), the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) recommend a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 against adjacent colors [4] [5]. This ensures the visualization is perceivable by individuals with moderate visual impairments.

Advanced Application: The Clustered Heatmap in Drug Development

The clustered heatmap is a powerful extension that provides deeper biological insights, crucial for applications in drug discovery and biomarker identification.

The clustered heatmap uses hierarchical clustering to group similar rows (genes) and columns (samples) together, revealing inherent structures in the data [1] [2]. This is represented by dendrograms, which are tree-like diagrams added to the margins of the heatmap. The primary analytical outcomes include:

- Sample Stratification: Identifying subgroups of patients or cell lines based on their global gene expression profiles, which can predict response to therapy [2].

- Gene Co-expression Analysis: Discovering groups of genes with similar expression patterns across conditions, which often implies functional relatedness or coregulation [2].

- Biomarker Discovery: Pinpointing specific genes whose expression is strongly associated with a particular disease state or treatment group [2].

Core Components of a Gene Expression Heatmap

A heatmap is a powerful, two-dimensional visualization tool for gene expression data, where a matrix of numerical values is represented as a grid of colored cells [1] [6]. Its primary merit lies in providing an intuitive, graphical overview of complex datasets, such as those from RNA sequencing or microarray experiments, allowing researchers to quickly discern patterns that would be difficult to identify in raw numerical tables [6].

The table below summarizes the function and interpretation of the three essential components of a gene expression heatmap.

| Component | Function & Representation | Interpretation Guide |

|---|---|---|

| Rows (Y-axis) | Typically represent individual genes, transcripts, or microbial Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) [7] [6]. | Each row shows the expression profile of a single gene across all sampled conditions. |

| Columns (X-axis) | Represent the different samples, experimental conditions, or time points under study (e.g., control vs. influenza-infected) [7] [6]. | Each column shows the expression levels of all measured genes within a single sample. |

| Color Scale (Legend) | A false-color scheme that encodes the numerical values of gene expression [8] [6]. Color palettes are chosen based on data type (sequential, diverging) [9] [10]. | The color of each cell corresponds to the expression level of a specific gene in a specific sample, allowing for immediate visual comparison of relative abundance or expression magnitude [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Creating a Gene Expression Heatmap from RNA-Seq Data

This protocol details the steps for generating a publication-quality clustered heatmap from raw RNA-seq count data, using R and its associated packages as a standard tool in life sciences [7] [8] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | A powerful, open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics, essential for data transformation and visualization [8] [6]. |

| RStudio IDE | An integrated development environment for R that simplifies script writing, execution, and project management. |

tidyr / dplyr R packages |

Packages for data "wrangling" and transformation, used to convert data into a "tidy" format suitable for plotting [7]. |

ggplot2 R package |

A powerful and flexible plotting system based on a "grammar of graphics" used to construct the heatmap layer-by-layer [7] [6]. |

pheatmap or ComplexHeatmap R packages |

Alternative, specialized packages offering advanced options for creating annotated and clustered heatmaps common in bioinformatics [6]. |

| Input Data File (.txt/.csv) | A tab-delimited text file where the first column contains gene names and subsequent columns contain expression values (e.g., counts, FPKM) for each sample [8]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Data Preparation and Input

- Format the expression data as a tab-delimited text file (.txt). The first column should contain gene identifiers, and the following columns should contain quantitative expression data (e.g., raw counts, FPKM) for each sample, with column headers [8].

- Experimental Note: The data should be normalized (e.g., transformed to log10 or VST for RNA-seq data) to better visualize variation across genes with both high and low expression levels [7]. This prevents a few highly expressed genes from dominating the color scale.

Step 2: Data Wrangling and "Tidying"

- For use with plotting packages like

ggplot2, the data must be converted from a "wide" to a "long" format. This creates a data frame with one row per gene-sample pair [7]. - Code Example using R

tidyr:

Step 3: Heatmap Visualization with ggplot2

- The

geom_tile()function inggplot2is used to draw the heatmap, where each cell is a "tile" colored by its corresponding expression value [7]. - Code Example:

Step 4: Enhancing Readability and Clustering

- Facetting: Use

facet_grid()to separate samples by a grouping variable liketreatment(e.g., control vs. influenza) for clearer comparison [7]. - Clustering: Advanced tools like

pheatmaporComplexHeatmapautomatically perform hierarchical clustering on rows and/or columns to group genes with similar expression profiles and samples with similar expression patterns [1] [6]. This reveals co-expression patterns and natural groupings in the data.

Step 5: Export and Save

- Use functions like

ggsave()in R to export the final heatmap in a high-resolution image format (e.g., .png, .tiff, .pdf) suitable for publication [7] [8].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Color Palette Performance

The choice of color palette is critical for accurate interpretation. The table below compares common palette types used in scientific visualization, evaluating their effectiveness against key accessibility and perceptual metrics [9] [12].

| Palette Type | Use Case in Genomics | Accessibility Score (Color-Blind Safety) | Perceptual Uniformity | Recommended Maximum Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Distinguishing distinct cell types or sample groups with no inherent order [9]. | Moderate to High (if chosen carefully) | N/A | 5-7 [12], up to ~10 [9] |

| Sequential | Displaying expression levels from low (or absent) to high [9] [10]. | High (if contrast is sufficient) | High (e.g., Viridis palette) [11] | Continuous scale |

| Diverging | Highlighting differential expression, showing genes upregulated (positive) and downregulated (negative) relative to a control or midpoint [9] [10]. | High (if contrast is sufficient) | High | Continuous scale |

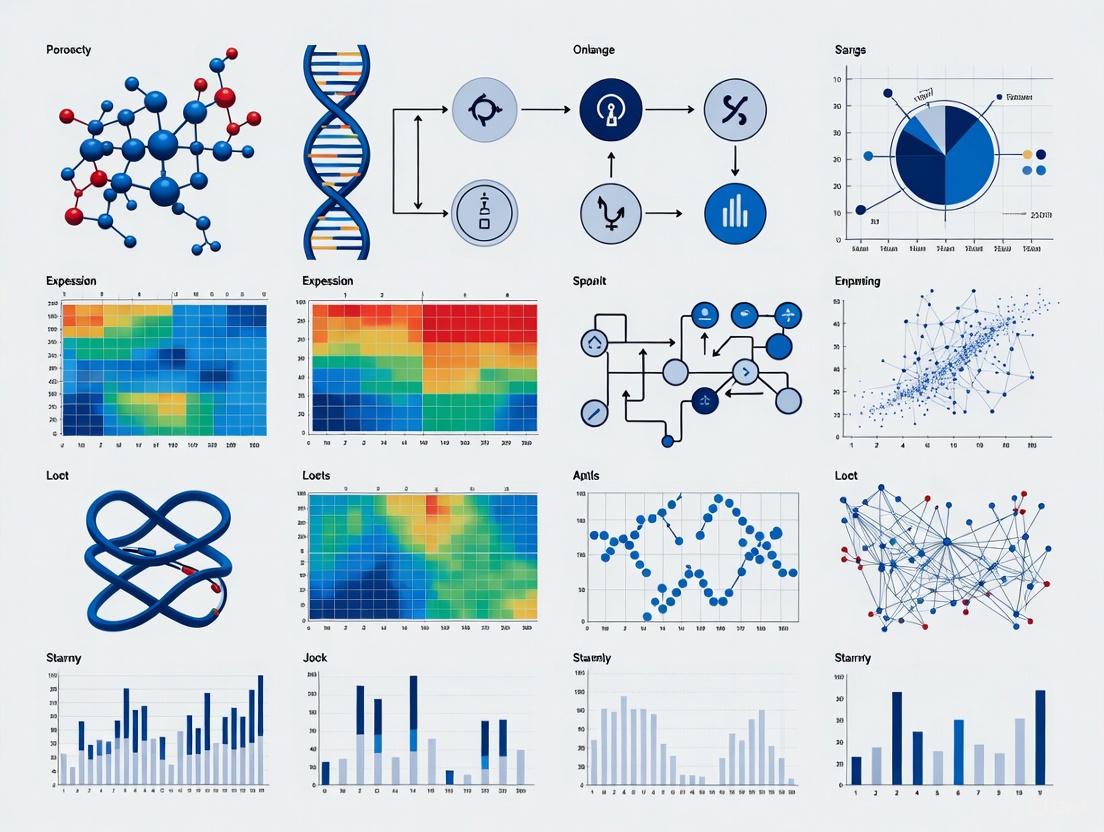

Workflow Diagram: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points involved in creating and interpreting a gene expression heatmap.

In the field of gene expression visualization research, the clustered heatmap with dendrograms stands as a cornerstone technique for uncovering hidden patterns in complex biological data. This graphical representation combines a heatmap, which uses color gradients to display data intensity, with dendrograms (tree-like diagrams) that illustrate the hierarchical clustering of rows and columns [13]. In essence, this method provides a powerful visual synthesis of numerical data and structural relationships, enabling researchers to identify sample subtypes, detect outlier data, discover co-expression patterns, and generate novel biological hypotheses from large-scale genomic datasets [14]. The integration of clustering visualization with expression data makes this approach particularly valuable for exploratory analysis in transcriptomics, where it serves as both a quality control measure and a discovery tool [15].

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

Components of a Clustered Heatmap

A clustered heatmap consists of several integrated visual elements:

- Heatmap: A color-coded matrix where individual values are represented as colors, typically showing gene expression levels across multiple samples [14]. The color gradient usually ranges from blue (down-regulated) through white (neutral) to red (up-regulated) in gene expression studies.

- Dendrogram: A tree-like diagram that results from hierarchical clustering, showing the relationship between data points based on similarity [16]. Most cluster heatmap packages position dendrograms along the top (for columns/samples) and left side (for rows/genes) of the heatmap [17].

- Color Bar: An annotation element that can be added alongside the heatmap to represent categorical or continuous phenotypic variables, such as treatment groups or clinical information [13] [14].

The Dendrogram: A Tree-Based Visualization

A dendrogram represents the results of hierarchical clustering, where the vertical height at which two branches connect indicates the distance or dissimilarity between clusters [16]. The bottom elements (leaves) represent individual data points (genes or samples), and as you move upward, branches merge to form increasingly larger clusters until all data points unite at the top [16]. The key interpretive principle is that a low merge height indicates high similarity (clusters grouped early), while a high merge height indicates low similarity (clusters grouped only at greater distances) [16].

Table 1: Dendrogram Interpretation Guidelines

| Feature | Interpretation | Implications for Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Low merge height | High similarity between joined elements | Potential functional relationship or shared regulation |

| High merge height | Low similarity between joined elements | Distinct biological groups or subtypes |

| Balanced tree structure | Uniform cluster sizes | Even distribution of similarities across data |

| Unbalanced tree structure | Varying cluster sizes | Possible outliers or natural group divisions |

| Long isolated branch | Potential outlier | Sample contamination or unique biological behavior |

Methodological Framework

Hierarchical Clustering Algorithms

The dendrogram is produced through hierarchical clustering, most commonly using the agglomerative (bottom-up) approach [16]. The algorithm follows these steps:

- Initialization: Treat each of the n data points as an individual cluster

- Distance Matrix Computation: Calculate an n×n distance matrix using a selected metric

- Iterative Merging: Identify and merge the two closest clusters, updating the distance matrix

- Repetition: Repeat step 3 until all points unite into a single cluster [16]

This process generates a linkage matrix that records the merging sequence and distances, which is then visualized as the dendrogram.

Critical Parameter Selection

The structure of the dendrogram is heavily influenced by two fundamental choices:

- Distance Metric: Determines how dissimilarity between individual data points is calculated

- Linkage Criterion: Defines how distances between clusters (containing multiple points) are computed

Table 2: Distance Metrics and Linkage Criteria for Gene Expression Data

| Parameter Type | Method | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Metrics | Euclidean | Continuous, normally distributed data [18] | Intuitive geometric distance | Sensitive to scale and outliers |

| Manhattan | High-dimensional sparse data [16] | Robust to outliers | Grid-like distance approximation | |

| Cosine | Text mining, direction-focused similarity [16] | Focuses on pattern rather than magnitude | Ignores vector magnitude | |

| Correlation | Gene expression patterns [17] | Captures co-expression patterns | Sensitive to noise | |

| Linkage Criteria | Ward's Method | Most gene expression studies [16] | Minimizes variance; compact clusters | Tends to create equally sized clusters |

| Complete Linkage | Identifying distinct sample subtypes [16] | Conservative; compact clusters | Sensitive to outliers | |

| Average Linkage | General-purpose biological data [18] | Balanced approach | May obscure clear cluster boundaries | |

| Single Linkage | Detecting chain-like structures [16] | Can detect non-spherical clusters | Prone to "chaining" effect |

Data Preprocessing Requirements

For gene expression data, proper preprocessing is essential for meaningful heatmap visualization:

- Data Normalization: RNA-seq data requires normalization for differences in sequencing depth and composition bias between samples [15].

- Data Transformation: When variables have different scales, standardization (such as z-score transformation) should be applied to ensure equal contribution of all genes to the clustering [18].

- Gene Selection: For focused analysis, filter genes by statistical significance (adjusted p-value < 0.01) and biological relevance (fold change > 1.5), then select top genes by p-value to avoid overcrowding [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Creating a Heatmap of Top Differentially Expressed Genes

This protocol follows the methodology demonstrated in the RNA-seq visualization tutorial [15] and can be implemented in R, Python, or through the Galaxy web platform.

Input Data Preparation

- Normalized Counts Table: A matrix of normalized expression values with genes in rows and samples in columns. Expression values are typically log2-transformed [15].

- Differential Expression Results: Statistical output from tools like limma-voom, edgeR, or DESeq2, containing columns for p-values and log fold changes [15].

- Experimental Design Metadata: Sample information including phenotypes, treatment groups, and other relevant annotations.

Software Implementation in R

Galaxy Platform Implementation

For researchers without programming expertise, the Galaxy platform provides accessible tools:

- Upload Data: Import normalized counts and differential expression results

- Filter Significant Genes: Use "Filter data on any column" tool with condition

c8<0.01for adjusted p-value, thenabs(c4)>0.58for absolute log fold change - Sort and Select Top Genes: Apply "Sort" tool by p-value column in ascending order, then "Select first" 21 lines (20 genes + header)

- Extract Counts: Use "Join two Datasets" to get normalized counts for selected genes

- Generate Heatmap: Use "heatmap2" tool with parameters:

- Data transformation: "Plot the data as it is"

- Z-score computation: "Compute on rows (scale genes)"

- Colormap: "Gradient with 3 colors" [15]

Protocol: Advanced Multi-Level Cluster Analysis with DendroX

For complex datasets where clusters reside at different hierarchical levels, DendroX provides interactive cluster selection [17].

Input File Preparation

- Programmatic Approach: Use helper functions in R or Python to extract linkage matrices from cluster heatmap objects (from seaborn.clustermap or pheatmap) and convert to JSON format

- Graphical Interface: Use DendroX Cluster program (standalone GUI) to input data matrix in delimited text file and generate JSON files for row/column dendrograms plus PNG heatmap image [17]

Interactive Cluster Identification

- Upload JSON and Image Files: Submit the dendrogram JSON file and optional heatmap image to DendroX web app

- Navigate Dendrogram: Switch between horizontal/vertical layouts depending on row/column focus

- Cluster Selection: Hover over non-leaf nodes to view cluster information; click to select/unselect clusters

- Multi-Level Selection: Identify and select clusters at different hierarchical levels with automatic color assignment

- Label Extraction: Export text labels from selected leaf nodes for functional enrichment analysis [17]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Clustered Heatmap Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | R Statistical Environment | Data preprocessing, statistical analysis, and visualization | Comprehensive analysis workflow implementation |

| Python with SciPy/NumPy | Data manipulation and computational clustering | Large-scale data processing and integration into AI pipelines | |

| Specialized R Packages | heatmap3 [14] | Advanced heatmap with enhanced annotation and clustering | Publication-quality figures with multiple phenotype annotations |

| pheatmap [17] | Basic to intermediate clustered heatmap generation | Standard clustering visualization with row/column dendrograms | |

| gplots (heatmap.2) [15] | Heatmap creation with clustering | General-purpose heatmap generation in R | |

| Python Libraries | Seaborn (clustermap) [17] | Statistical data visualization with clustering | Python-based clustered heatmap generation |

| SciPy (hierarchy module) | Hierarchical clustering algorithms | Custom clustering implementation and dendrogram creation | |

| Web-Based Platforms | Galaxy Platform [15] | Web-based bioinformatics analysis | Accessible analysis for wet-lab researchers without coding expertise |

| DendroX [17] | Interactive dendrogram exploration | Multi-level cluster selection and validation | |

| Visualization Tools | Origin 2025b [13] | Integrated graphing and data analysis | Straightforward heatmap creation with point-and-click interface |

| NCSS [18] | Statistical analysis with clustering | Comprehensive suite with eight hierarchical clustering algorithms |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Validation

Determining Cluster Number and Boundaries

Identifying the appropriate number of clusters is a critical interpretive step:

- Visual Inspection Method: Draw horizontal lines across the dendrogram at different heights; the number of vertical lines intersected indicates the number of clusters at that dissimilarity level [16].

- Statistical Guidance: Use the inconsistency coefficient (measuring height jumps) where large values suggest natural cluster boundaries, or apply silhouette scores to evaluate cluster quality after cutting [16].

- Bootstrap Validation: Implement resampling methods like pvclust in R to compute p-values for branches, assessing robustness [17].

- Biological Validation: Correlate cluster assignments with known biological annotations (e.g., pathway enrichment, clinical variables) to ensure meaningful groupings [14].

Addressing Common Analytical Challenges

- Data Scaling: For genes with different expression ranges, apply z-score standardization to ensure equal contribution to clustering [18].

- Large Datasets: Use the "fastcluster" package in R for efficient processing of large expression matrices [14].

- Color Contrast: Ensure sufficient contrast (minimum 3:1 ratio) for all visual elements to maintain accessibility [4].

- Multiple Testing: When using clustering to identify subtypes, follow with appropriate statistical tests (chi-squared for categorical annotations, ANOVA for continuous variables) to validate associations [14].

Application in Drug Development Research

Clustered heatmaps with dendrograms have proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, as demonstrated by the LINCS L1000 case study [17]. In this application:

- Mechanism of Action Analysis: Researchers clustered gene expression signatures of 297 bioactive chemical compounds, identifying 17 biologically meaningful clusters based on dendrogram structure and heatmap patterns [17].

- Novel Compound Discovery: The analysis revealed a previously unreported cluster consisting mostly of naturally occurring compounds with shared broad anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities [17].

- Bioactivity Assessment: Cosine distance between compound signatures helped quantify similarity of biological effects, enabling prediction of mechanisms and potential applications [17].

This approach allows drug development professionals to efficiently categorize compounds, hypothesize mechanisms of action, and identify promising candidates for further investigation based on transcriptional response patterns.

Clustered heatmaps with dendrograms represent an indispensable analytical tool in gene expression visualization research, successfully bridging numerical analysis and visual interpretation. The power of this technique lies in its ability to simultaneously reveal patterns at multiple hierarchical levels—from individual genes to coordinated programs of expression—while maintaining the context of overall dataset structure. When properly implemented with appropriate preprocessing, parameter selection, and validation protocols, this method continues to drive discovery across biological research and drug development, transforming complex transcriptomic data into actionable biological insights.

In gene expression analysis, identifying upregulated and downregulated gene groups is fundamental for understanding cellular responses, disease mechanisms, and the effects of pharmacological treatments. Heatmaps serve as a powerful visualization tool, transforming complex gene expression matrices into intuitive color-coded diagrams that reveal patterns of transcriptional activity across different experimental conditions or cell populations [1] [19]. These patterns are critical for extracting biological meaning, such as identifying coordinated regulatory mechanisms, signaling pathways, and potential drug targets. Framed within a broader thesis on creating heatmaps for gene expression visualization, these application notes provide detailed protocols for discerning biologically significant gene groups from heatmap visualizations, enabling researchers to move beyond mere pattern recognition to genuine biological insight.

The selection of biologically relevant genes relies on various statistical metrics. The table below summarizes key quantitative measures used to identify upregulated and downregulated gene groups from expression data, providing a comparison for method selection.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Identifying Regulated Gene Groups

| Metric Name | Statistical Foundation | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Homeostasis Z-index [20] | K-proportion inflation test against a negative binomial distribution | Identifying genes actively regulated in a small proportion of cells | Distinguishes genes with widespread variability from those with sharp upregulation in subsets |

| Seurat VST [20] | Variance stabilizing transformation | Identifying highly variable genes across a cell population | Effective for capturing cell-to-cell variability |

| SCRAN [20] | Model-based variance estimation | Capturing cell-to-cell variability in single-cell data | Particularly effective for variability analysis as per benchmarking |

| Seurat MVP [20] | Mean-variance relationship | Finding genes with high variance relative to their mean | Accounts for the dependence of variance on expression level |

| Fold Change | Ratio of mean expression between groups | Initial screening for differentially expressed genes | Intuitively simple and biologically interpretable |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Adjusted p-value from multiple hypothesis testing | Controlling for Type I errors in differential expression | Reduces the likelihood of false positive discoveries |

Experimental Protocol for Gene Group Identification via Heatmap Analysis

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Purpose: To prepare raw gene expression count data for reliable analysis and visualization. Materials: Raw gene expression matrix (e.g., from RNA-seq or single-cell RNA-seq). Reagents/Software: R/Python, Normalization tools (e.g., SCTransform, Scran).

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells or genes. For single-cell data, remove cells with an abnormally high mitochondrial gene percentage or low unique gene counts.

- Normalization: Apply a normalization method to correct for technical variations (e.g., sequencing depth). For single-cell data, use SCTransform or Scran [20]. For bulk data, use methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) or DESeq2's median of ratios.

- Transformations: Apply a log-transformation (e.g., log(1+x)) to stabilize the variance across the dynamic range of expression values. For highly variable gene selection, the Seurat VST method can be applied at this stage [20].

- Scaling: Scale the expression values for each gene to a Z-score (mean=0, standard deviation=1) to ensure that color intensity in the heatmap reflects relative expression across samples, not absolute expression level.

Identifying Regulated Gene Groups

Purpose: To statistically identify genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated under specific conditions. Materials: Normalized and scaled gene expression matrix. Reagents/Software: Differential expression tools (e.g., Seurat, Limma, EdgeR), Single-cell analysis platforms (e.g., CZ CELLxGENE [21]).

- Differential Expression Testing:

- For bulk RNA-seq: Use tools like Limma or EdgeR to perform a statistical test (e.g., t-test modified for count data) between experimental groups (e.g., treated vs. control). Genes with a high fold change and a low FDR (e.g., FDR < 0.05) are considered differentially expressed.

- For single-cell RNA-seq: Use the

FindMarkersorFindAllMarkersfunction in Seurat, which typically employs a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test or a model-based approach. Alternatively, for genes with regulation in small cell subsets, calculate the Gene Homeostasis Z-index [20].

- Gene Homeostasis Z-index Calculation (for single-cell data):

- Calculate k-proportion: For each gene, compute the percentage of cells with expression levels below a value

k, which is determined by the mean gene expression count [20]. - Wave Plot Visualization: Plot k-proportion against mean expression to visually identify "droplet" genes that are outliers above the general trend, indicating active regulation [20].

- Inflation Test: Perform a k-proportion inflation test against a set of negative binomial distributions to obtain a Z-score for each gene. A higher Z-index indicates lower stability and more active regulation [20].

- Calculate k-proportion: For each gene, compute the percentage of cells with expression levels below a value

- Gene List Compilation: Compile separate lists of significantly upregulated and downregulated genes based on the chosen metric (e.g., positive fold change and FDR for upregulated; negative fold change and FDR for downregulated; high Z-index for instability).

Heatmap Generation and Interpretation

Purpose: To visualize the expression patterns of identified gene groups across all samples or cells. Materials: List of regulated genes; processed expression matrix. Reagents/Software: Heatmap generation tools (e.g., ComplexHeatmap in R, Clustermap in Seaborn (Python), Cytoscape [22], CELLxGENE Explorer [21]).

- Data Extraction: Subset the normalized and scaled expression matrix to include only the significantly upregulated and downregulated genes.

- Clustering: Perform hierarchical clustering on both the genes (rows) and the samples/cells (columns). This groups genes with similar expression patterns and samples with similar transcriptional profiles. Use Euclidean or correlation-based distance metrics.

- Color Map Definition: Define a diverging color palette. A typical scheme uses a gradient from blue (for downregulated genes/low expression) to white (neutral) to red (for upregulated genes/high expression) [1] [23]. Use a legend to map colors to Z-scores or expression values.

- Rendering: Generate the heatmap, ensuring that dendrograms showing the clustering relationships are displayed.

- Biological Interpretation:

- Pattern Recognition: Identify clusters of genes (rows) that show coordinated up- or down-regulation. These often represent co-regulated genes or genes involved in the same biological pathway.

- Sample Stratification: Identify clusters of samples (columns) that show similar expression profiles. This can reveal previously unknown subtypes or states.

- Annotation: Annotate the heatmap with sample metadata (e.g., disease state, treatment, cell type) to correlate expression patterns with biological or clinical variables.

Diagram 1: Gene expression heatmap analysis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Platforms for Gene Expression Heatmap Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CZ CELLxGENE Discover [21] | A platform to visually explore single-cell data and perform differential expression. | Leveraging millions of cells from an integrated corpus for powerful, interactive analysis. |

| Cytoscape [22] | Open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating attribute data. | Creating enriched heatmaps by projecting functional annotations and pathway data onto gene networks. |

| Seurat [20] | R toolkit for single-cell genomics. | Performing quality control, normalization, highly variable gene selection, and differential expression. |

| SCRAN [20] | Method for model-based variance estimation in single-cell data. | Capturing cell-to-cell variability for gene selection. |

| Heatmap Color Map [24] | A defined gradient (e.g., blue-white-red) to convert data values to colors. | Visual encoding of gene expression levels (low-medium-high) in the heatmap. |

| Clustering Algorithm (e.g., Hierarchical) | Groups genes/samples with similar expression patterns. | Revealing co-regulated gene modules and sample subtypes within the data. |

| Negative Binomial Distribution [20] | A statistical model used as a null for gene expression counts. | Benchmarking and identifying regulatory genes via the Gene Homeostasis Z-index. |

Signaling Pathway and Analysis Logic Diagram

The process of extracting biological meaning from a heatmap involves a logical progression from data generation to biological hypothesis. The following diagram outlines the key decision points and analytical steps, from raw data processing through to the identification of regulated gene groups and their functional interpretation, which often involves mapping onto known signaling pathways.

Diagram 2: Logic flow from data to biological insight.

Gene expression analysis is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, providing critical insights into cellular mechanisms, disease states, and drug responses. This application note details integrated protocols for analyzing differential gene expression and conducting pathway enrichment analysis, framed within a broader thesis on creating heatmaps for gene expression visualization research. We present a standardized workflow that transforms raw gene expression data into biologically meaningful insights through rigorous statistical analysis, sophisticated visualization, and functional interpretation. The methodologies described herein are specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust, reproducible techniques for extracting knowledge from high-throughput genomic data. By combining computational approaches with biological validation strategies, these protocols enable comprehensive investigation of transcriptomic changes across experimental conditions, disease states, and therapeutic interventions, with particular emphasis on effective visual communication of complex datasets through heatmap representations.

Research Reagent Solutions and Bioinformatics Tools

Successful gene expression analysis requires both wet-laboratory reagents and computational tools. The following table summarizes essential resources referenced in this protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Bioinformatics Tools for Gene Expression and Pathway Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | R Package | Differential expression analysis | Identifies statistically significant gene expression changes between experimental conditions using negative binomial distribution models |

| limma | R Package | Linear models for microarray & RNA-seq data | Handles complex experimental designs; provides robust differential expression analysis for various platform data |

| DAVID | Web Tool | Functional Annotation & Enrichment Analysis | Identifies over-represented biological themes, particularly Gene Ontology terms and KEGG pathways [25] |

| Reactome | Pathway Database | Curated pathway visualization & analysis | Provides pathway browser and analysis tools for visualizing genes within biological pathways [26] |

| pheatmap | R Package | Annotated heatmap creation | Generates publication-quality heatmaps with row/column annotations and clustering visualization [27] |

| ggplot2 | R Package | Customizable data visualization | Creates highly customizable heatmaps using geom_tile() with full control over aesthetic elements [7] |

| tidyr | R Package | Data wrangling & transformation | Converts wide-format data to long format using pivot_longer() for compatibility with ggplot2 [7] |

| RColorBrewer | R Package | Color scheme management | Provides perceptually appropriate color palettes for data visualization [27] |

Differential Gene Expression Analysis Protocol

Experimental Workflow and Data Processing

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical workflow from raw data to biological insight:

Diagram: Gene expression analysis workflow from raw data to biological interpretation

Detailed Methodology for Differential Expression Analysis

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Begin with raw gene expression data, typically as a count matrix from RNA-seq or normalized intensities from microarray experiments. The example dataset employed in this protocol examines gene expression in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells infected with influenza virus compared to uninfected controls [7]. Implement quality control measures including assessment of read depth, gene detection rates, and sample-level clustering to identify potential outliers. Normalize data to account for technical variability using appropriate methods such as TPM (Transcripts Per Million) for RNA-seq or RMA (Robust Multi-array Average) for microarray data.

Statistical Analysis for Differential Expression

Apply statistical methods tailored to your data type. For RNA-seq count data, utilize negative binomial-based models implemented in DESeq2 or edgeR. For microarray data, employ linear models with empirical Bayes moderation as implemented in the limma package. The following parameters should be specified:

- Fold change threshold: Minimum expression difference (typically 1.5-2x)

- Statistical significance: Adjusted p-value (FDR < 0.05)

- Multiple testing correction: Benjamini-Hochberg procedure

The analysis generates a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with statistics including log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values.

Result Interpretation and Gene Selection

Select significant genes based on statistical thresholds and biological relevance. Filter the DEG list to focus on genes meeting both fold change and statistical significance criteria. Prepare these genes for downstream visualization and functional analysis by exporting gene identifiers (e.g., official gene symbols, ENSEMBL IDs) in a standardized format. Document the number of up-regulated and down-regulated genes for experimental quality assessment.

Heatmap Visualization Protocol

Data Transformation for Effective Visualization

Gene expression data must be transformed from a wide to a long format for visualization with ggplot2. The initial data structure with subjects as rows and genes as columns requires restructuring:

Table 2: Data Structure Transformation for Heatmap Visualization

| Original Wide Format | Transformed Long Format |

|---|---|

| subject, treatment, IFNA5, IFNA13, IFNA2, ... | subject, gene, expression |

| GSM1684095, control, 83.129, 107.219, 195.175 | GSM1684095, IFNA5, 83.129 |

| GSM1684096, influenza, 10096.47, 18974.16, 24029.11 | GSM1684095, IFNA13, 107.219 |

| ... | GSM1684095, IFNA2, 195.175 |

Implement this transformation using the pivot_longer() function from the tidyr package [7]:

For large expression datasets with extreme value ranges, apply logarithmic transformation (e.g., log10 or log2) to better visualize variation across magnitude scales:

Heatmap Generation and Customization

Basic Heatmap Creation

Create a foundational heatmap using ggplot2's geom_tile() geometry:

For enhanced clustering and annotation capabilities, use the pheatmap package with a matrix format [27]:

Advanced Customization and Styling

Improve visual interpretation through strategic customization:

- Color Selection: Use perceptually uniform colormaps (e.g., viridis, plasma) that maintain interpretability when converted to grayscale and accommodate color vision deficiencies [28]

- Annotation Integration: Incorporate sample metadata (e.g., treatment groups, patient characteristics) and gene annotations (e.g., functional groups) [27]

- Aesthetic Refinements: Rotate axis labels, adjust font sizes, and apply faceting to separate experimental conditions

Color Scheme Design Principles

Effective colormap selection follows specific perceptual principles based on data characteristics:

Diagram: Colormap selection guide based on data characteristics

Pathway Enrichment Analysis Protocol

Functional Annotation Using DAVID

With significantly differentially expressed genes identified and visualized, proceed to functional interpretation using the DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery) bioinformatics resource [25].

Data Preparation and Submission

Prepare the gene list using official gene symbols or ENTREZ gene identifiers. Submit this list to the DAVID functional annotation tool through these steps:

- Access the DAVID portal at https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov

- Select the appropriate species identifier (e.g., Homo sapiens)

- Upload the gene list through the "Gene List Manager" interface

- Set the background population appropriate for your experimental context (typically the whole genome)

Enrichment Analysis and Interpretation

Execute functional annotation analysis with these parameter settings:

- Annotation Categories: Gene Ontology (Biological Process, Molecular Function, Cellular Component), KEGG Pathways, Reactome Pathways

- Statistical Threshold: EASE Score (modified Fisher's exact test) p-value < 0.05

- Multiple Testing Correction: Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.1

Interpret significantly enriched terms by considering both statistical strength (FDR) and biological relevance to your experimental context. Focus on functionally coherent term clusters rather than isolated significant terms.

Pathway Visualization and Integration

Complement DAVID analysis with pathway visualization using Reactome Pathway Browser [26]. This enables direct observation of how differentially expressed genes interact within biological systems:

- Access the Reactome Pathway Browser at https://reactome.org

- Search for pathways of interest identified in the enrichment analysis

- Upload your gene expression data to visualize expression patterns directly on pathway diagrams

- Analyze pathway topology to identify key regulatory nodes and bottlenecks

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Analytical Challenges

- Data Normalization Issues: Address batch effects and systematic technical variations before differential expression analysis

- Multiple Testing Concerns: Apply appropriate FDR corrections to avoid false positive discoveries in large-scale testing

- Heatmap Overplotting: For large gene sets (>1000 genes), consider filtering by significance or focusing on key functional groups

- Pathway Analysis Bias: Be aware of annotation biases in functional databases where well-studied genes/pathways are over-represented

Quality Assessment Metrics

- Clustering Validation: Assess dendrogram quality in heatmaps using bootstrap resampling

- Enrichment Reliability: Prioritize pathways with consistent enrichment across multiple databases

- Biological Coherence: Evaluate whether results align with established biological knowledge and experimental expectations

This integrated protocol provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing differential gene expression and conducting pathway enrichment analysis, with emphasis on effective visualization through heatmaps. By following these standardized methodologies, researchers can transform raw gene expression data into biologically meaningful insights with enhanced reproducibility and interpretability. The combination of rigorous statistical analysis, thoughtful visualization strategies, and systematic functional interpretation enables robust investigation of transcriptomic changes across diverse biomedical research contexts.

Hands-On Guide: Building Publication-Ready Heatmaps with R, pheatmap, and Web Tools

Heatmaps are indispensable for visualizing complex gene expression data in transcriptomic research. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of three prominent tools—R/pheatmap, the web-based Heatmapper2, and Galaxy's heatmap2—detailing their respective protocols, capabilities, and optimal use cases. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide includes standardized workflows, comparative tables, and visual diagrams to facilitate the selection and implementation of the most appropriate heatmap tool for specific research objectives within a broader thesis on gene expression visualization.

In molecular biology and drug development, heatmaps allow for the intuitive visualization of information-rich data, such as RNA-seq results, by using color gradients to represent variations in gene expression across multiple samples or conditions [29]. The choice of tool for generating these heatmaps can significantly impact the efficiency, reproducibility, and depth of analysis. This document examines three distinct platforms: pheatmap, an R package known for its high customization and local computational power; Heatmapper2, a comprehensive web server offering ease of use and a wide array of heatmap types without local installation; and Galaxy's heatmap2, a tool within an open-source platform that emphasizes reproducible analysis workflows and user-friendly access to complex bioinformatics tools [29] [15] [30]. We provide a detailed, side-by-side comparison and standardized protocols to guide researchers in leveraging these tools effectively.

Tool Comparison and Selection Guide

Selecting the right tool depends on the researcher's computational resources, technical expertise, and specific analytical needs. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each tool to aid in this decision.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Heatmap Visualization Tools

| Feature | R/pheatmap | Heatmapper2 | Galaxy heatmap2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platform/Environment | R statistical language (local installation) | Web server (https://heatmapper2.ca/) |

Web-based platform (public instance or local deployment) |

| Primary Use Case | Customizable, publication-quality figures within a scripted workflow | Quick, user-friendly generation of diverse heatmap types without coding | Reproducible, workflow-integrated analysis within a graphical interface |

| Key Strengths | High customization of aesthetics (annotations, colors, clustering); seamless integration with R-based bioanalysis [30]. | No installation; fast client-side processing via WebAssembly; supports numerous specialized heatmap classes (e.g., temporal, 3D, geospatial) [29]. | User-friendly GUI; promotes reproducible research; part of a larger ecosystem of bioinformatics tools [15]. |

| Data Scaling Options | scale="row" or scale="column" for Z-scores; custom scaling via manual functions [30]. |

Options for row or column scaling during the configuration process. | Options include "Compute on rows (scale genes)" for Z-score calculation [15]. |

| Clustering Controls | Highly customizable clustering (method, distance, row/column toggle) [31]. | Configurable clustering options within the web interface. | Basic clustering controls (enable/disable) [15]. |

| Annotation Capabilities | Rich: supports row and column annotations with custom color schemes [30]. | Varies by heatmap class; generally supports sample annotations. | Limited primarily to row and column labels. |

To further aid in the selection process, the following decision tree outlines a logical path based on critical project requirements.

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Creating an Expression Heatmap with R/pheatmap

This protocol is designed for users with basic R knowledge and focuses on generating a annotated heatmap from a normalized count matrix.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Normalized Count Matrix: A table where rows are genes, columns are samples, and values are normalized expression levels (e.g., log2-transformed counts). This is the primary input data.

- Annotation Data Frames: Data frames containing metadata for rows (e.g., gene clusters) and columns (e.g., sample type, treatment), with row names matching the count matrix.

- R Color Palettes: Functions like

colorRampPalette()or packages likeRColorBrewerto create continuous or discrete color schemes for the data and annotations.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Installation and Data Preparation: Install the

pheatmappackage and load your data. Ensure the expression data is a matrix and annotation data frames have matching row/column names.

Data Scaling and Basic Heatmap: Scale the data by row (gene) to highlight relative expression differences and generate a basic clustered heatmap.

Customization with Annotations and Clustering: Add annotations, control clustering, and customize the color scheme for a publication-ready figure.

Protocol: Creating an Expression Heatmap with Galaxy's heatmap2

This protocol uses a graphical interface, making it accessible for wet-lab scientists or those new to programming. The workflow is based on the official Galaxy training material [15].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Normalized Counts File: A tabular file with genes in rows, samples in columns, and normalized expression values.

- Gene List File: A simple list of gene identifiers (e.g., ENTREZID or gene symbols) for the genes of interest (e.g., top differentially expressed genes).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Upload and History Creation:

- Log in to a Galaxy instance (e.g., usegalaxy.org).

- Create a new history and name it (e.g., "RNA-seq heatmap").

- Upload your

normalized countsfile andgene listfile via the Upload tool. Ensure the datatype is set totabular.

Data Joining and Matrix Preparation:

- Use the Join two Datasets tool to combine the

gene listwith thenormalized countsfile, matching on the gene identifier column. - Use the Cut tool to extract only the columns containing the gene names and the normalized expression values for the samples of interest. The output will be your final expression matrix.

- Use the Join two Datasets tool to combine the

heatmap2 Tool Execution:

- Open the heatmap2 tool from the transcriptomics section.

- Set the parameters as follows [32] [15]:

- "Input should have column headers": Your prepared expression matrix.

- "Data transformation":

Plot the data as it is. - "Compute z-scores prior to clustering":

Compute on rows (scale genes). - "Enable data clustering":

YesorNo, as required. - "Labeling columns and rows":

Label my columns and rows. - "Type of colormap to use":

Gradient with 3 colors.

- Execute the tool. The resulting heatmap will be displayed in the history panel.

Protocol: Creating a Heatmap with Heatmapper2

Heatmapper2 is ideal for rapid generation of standard and specialized heatmaps without software installation.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Expression Data File: A tab-delimited text file where rows are features (genes), columns are samples, and the first row contains sample names.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Access and Data Input:

- Navigate to the Heatmapper2 website:

https://heatmapper2.ca/. - Click on the "Expression" heat mapping class.

- Paste your expression data into the input box or upload your text file. Select the appropriate delimiter (e.g., Tab).

- Navigate to the Heatmapper2 website:

Customization and Processing:

- Configure the heatmap parameters according to your needs:

- Scale: Choose to scale by row, column, or neither.

- Color Scheme: Select a preset gradient or create a custom one.

- Clustering Method: Choose the algorithm (e.g., Average Linkage) and distance metric (e.g., Euclidean).

- Show Data Values: Optionally display numerical values in the heatmap cells.

- Click the "Submit" or "Draw" button. Heatmapper2 will process the data using client-side resources and display the interactive heatmap.

- Configure the heatmap parameters according to your needs:

Output and Download:

- The heatmap will be displayed in the browser, allowing for interactive inspection.

- Use the "Download Heatmap" button to save the visualization in your preferred format (e.g., PNG, PDF). You can also download the current settings for future reproducibility.

The logical flow of data preparation and analysis across these three platforms can be visualized as follows.

Advanced Technical Notes

Controlling the Color Scale and Legend in pheatmap

For consistent comparison across multiple heatmaps, it is crucial to fix the legend scale. In pheatmap, this is achieved using the breaks parameter. This ensures that the same color always represents the same data value, even across different datasets or timepoints [33].

Handling Large Datasets and Performance

- R/pheatmap: Performance depends on local RAM. For very large datasets (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq), consider filtering lowly expressed genes or using a computing cluster.

- Heatmapper2: Leverages WebAssembly for client-side processing, offloading computation to the user's machine. This avoids server congestion and can handle large files efficiently [29].

- Galaxy: Performance is tied to the specific public instance or local server. Public servers may have job time limits, so for heavy workloads, a local Galaxy instance is recommended.

The choice between R/pheatmap, Heatmapper2, and Galaxy's heatmap2 is not a matter of which tool is superior, but which is most appropriate for the research context. R/pheatmap offers unparalleled control and customization for the computationally adept user. Heatmapper2 provides speed, accessibility, and a wide range of heatmap types for standard and specialized applications. Galaxy's heatmap2 excels in user-friendliness and integrates heatmap generation into larger, reproducible bioinformatics workflows. By applying the protocols and guidelines outlined in this document, researchers can confidently select and utilize these powerful tools to derive meaningful biological insights from their gene expression data.

Within the context of a broader thesis on creating heatmaps for gene expression visualization research, this document provides a detailed protocol for generating annotated heatmaps using the pheatmap package in R. Heatmaps are indispensable tools in computational biology, allowing researchers and drug development professionals to visualize complex gene expression matrices and identify underlying patterns, such as sample clustering and co-expressed genes [1] [34]. The pheatmap package is particularly powerful due to its flexibility in adding annotations to rows and columns, resulting in publication-ready figures [27] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential software and packages required to execute the protocols in this document.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| R and RStudio | Programming environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Provides the foundational platform for all data analysis and visualization steps. |

pheatmap R Package |

Primary function for creating clustered and annotated heatmaps. | Simplifies the creation of highly customizable heatmaps with integrated clustering and annotation support [27] [30]. |

RColorBrewer R Package |

Provides color palettes for data visualization. | Offers a curated collection of sequential and diverging color palettes suitable for scientific publication [27] [35]. |

| Gene Expression Matrix | The primary input data, with genes as rows and samples as columns. | Standardized data structure for differential gene expression analysis. Row names should be gene identifiers [27]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Normalization

Proper data preparation is critical for generating a meaningful and interpretable heatmap.

Materials: Gene expression matrix (e.g., from RNA-seq or microarray experiments), R software environment.

Procedure:

Load Data and Clean Environment: Begin by clearing the R environment and loading necessary libraries to ensure a clean, reproducible workflow.

Load Gene Expression Data: Import your gene expression data. Ensure the gene identifiers are set as row names, and the matrix contains only numerical expression values [27].

For the purpose of this protocol, we will generate a sample dataset.

Data Normalization (Z-score Scaling): Normalize the data across genes (rows) to make expression profiles comparable. This step calculates a Z-score, which shows how many standard deviations an expression value is from the gene's mean across samples [30] [36].

Alternatively, the

pheatmapfunction has a built-inscale = "row"parameter, but manual scaling offers more transparency and control.

Protocol 2: Creating Annotation Data Frames

Annotations provide crucial metadata for interpreting the heatmap, such as sample groups (e.g., disease vs. control) or gene functional categories.

Procedure:

Create Column Annotations: Generate a data frame where row names match the column names of your expression matrix.

Create Row Annotations: Generate a data frame where row names match the row names (gene identifiers) of your expression matrix.

Protocol 3: Configuring the Color Scheme

Color is the primary channel for conveying value in a heatmap. The choice of palette should be intentional [1] [34].

Procedure:

Define Annotation Colors: Create a named list that maps annotation values to specific colors.

Select Data Color Palette: Choose a palette for the expression data itself. For Z-scores, a diverging palette (e.g.,

RdBuorRdYlGn) is often appropriate, with one color for negative values (down-regulation), one for positive values (up-regulation), and a neutral color for zero [34].

Protocol 4: Generating the Annotated Heatmap

This protocol brings all components together to create the final visualization.

Procedure:

Execute the

pheatmapFunction: Call thepheatmapfunction with the normalized data and all customizations.Save the Heatmap: Save the generated heatmap as a high-resolution image file suitable for publications.

Workflow and Logical Relationships Visualization

The following diagram summarizes the complete logical workflow from raw data to final heatmap, as described in the protocols above.

Table 2: Key pheatmap Function Parameters for Experimental Design

| Parameter | Type/Options | Default | Effect on Visualization | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

cluster_rows/cols |

Logical (TRUE/FALSE) | TRUE | Enables/disables hierarchical clustering dendrograms. | Set to FALSE to suppress clustering if sample order is predefined. |

clustering_method |

Character (e.g., "complete", "ward.D2") | "complete" | Determines how clusters are linked based on distance. | "ward.D2" often produces more compact, balanced clusters. |

scale |

Character ("row", "column", "none") | "none" | Scales the data by row (gene) or column (sample). | Use "row" for gene expression to compare expression profiles across samples. |

annotation_row/col |

Data Frame | NA | Adds metadata annotations to rows/columns. | Data frame row names must match matrix row/column names. |

show_rownames/colnames |

Logical (TRUE/FALSE) | TRUE | Displays row/column names. | Set show_rownames=FALSE for large gene sets to avoid clutter. |

color |

Vector of Colors | colorRampPalette |

Defines the color map for the data. | Use diverging palettes (e.g., RColorBrewer 'RdYlGn') for Z-scores. |

breaks |

Vector of Numerics | Uniform breaks | Defines the value intervals mapped to each color. | Use quantile breaks for non-normal data to represent equal proportions [35]. |

Within the broader context of gene expression visualization research, the creation of insightful heatmaps relies fundamentally on proper data wrangling. The accuracy and biological relevance of the final visual output are directly dependent on the careful preparation of two core components: the expression matrix, which contains the quantitative gene expression measurements, and the annotation dataframes, which provide essential metadata about samples and experimental conditions. This protocol details the methodologies for formatting these components to ensure the production of publication-quality heatmaps that accurately represent complex transcriptomic data. The procedures outlined here are particularly crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who need to visualize differentially expressed genes and identify potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

Expression Matrix Preparation

Structural Requirements and Normalization

The expression matrix forms the quantitative foundation of any gene expression heatmap. This matrix should be structured with genes as rows and samples as columns, with each cell containing normalized expression values [37]. Proper normalization is critical to remove technical variations while preserving biological signals. For RNA-seq data, common normalization methods include DESeq2's median of ratios or EdgeR's trimmed mean of M-values, which account for library size and RNA composition differences. For microarray data, RMA or quantile normalization are typically employed. The normalized expression values should be transformed appropriately—often log2-transformed for RNA-seq data—to stabilize variance and make the data more symmetric for visualization.

Table 1: Expression Matrix Structure Specification

| Component | Specification | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Row Names | Unique gene identifiers | ENSG00000000003, MOV10 | Use stable identifiers (ENSEMBL, ENTREZ) rather than symbols |

| Column Names | Sample identifiers | Mov10oe1, Mov10oe2, Control_1 | Consistent with metadata sample names |

| Values | Normalized expression | 15.32, 18.05, 12.88 | Log2-transformed for RNA-seq; Z-scores for cross-gene comparison |

| Missing Data | Explicitly coded | NA, NaN | Handle before heatmap generation |

| Matrix Type | Numeric only | - | Remove any character columns before conversion |

Implementation Protocol

To extract and prepare the normalized expression matrix from a DESeq2 object, follow this experimental protocol:

Normalization Implementation:

Data Extraction and Formatting:

Subsetting for Significant Genes:

The workflow for expression matrix preparation involves multiple validation steps to ensure data integrity before proceeding to visualization:

Annotation Dataframes Construction

Annotation Types and Structural Framework

Annotation dataframes provide the critical contextual information that enables meaningful interpretation of heatmap patterns. In heatmap visualization, annotations can be positioned on all four sides of the heatmap (top, bottom, left, right) to describe either sample characteristics (column annotations) or gene attributes (row annotations) [38] [39]. There are two primary classes of annotations: simple annotations, which use color-coding to represent categorical or continuous variables, and complex annotations, which incorporate graphical elements such as barplots, point markers, or other custom visualizations.

Table 2: Annotation Dataframe Specifications

| Component | Specification | Example | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Row/Column Matching | Same order as expression matrix | Sample names in identical sequence | Essential for correct annotation alignment |

| Categorical Variables | Factor data type | sampletype = c("OE", "OE", "Control", "Control") | Color mapping to discrete groups |

| Continuous Variables | Numeric data type | purity = c(0.95, 0.87, 0.92, 0.76) | Color gradient mapping |

| Color Mapping | Named list for discrete; colorRamp2 for continuous | list(sampletype = c("OE" = "#EA4335", "Control" = "#4285F4")) | Consistent color schemes across visualizations |

| Missing Data Handling | Explicit NA representation with defined color | na_col = "grey" | Visual identification of missing annotations |

Implementation Protocol for Annotation Construction

Sample Annotation Construction:

Gene Annotation Construction:

Complex Annotations with Graphical Elements:

The process of constructing annotation dataframes requires careful matching with the expression matrix and appropriate color specification:

Integration and Visualization

Heatmap Generation with Integrated Components

The integration of properly formatted expression matrices and annotation dataframes enables the generation of informative heatmaps. This integration is implemented through specific functions in R that combine these components into a cohesive visualization. The following protocol details the complete heatmap generation process:

Color Palette Selection for Scientific Visualization

The choice of color palette is critical for accurate data interpretation in scientific visualizations. Effective heatmaps use color schemes that represent data accurately while remaining accessible to readers with color vision deficiencies.

Table 3: Heatmap Color Palette Specifications

| Palette Type | Color Codes | Application | Accessibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | #F1F3F4 to #5F6368 to #202124 | Expression levels, purity metrics | Ensure 3:1 contrast ratio for adjacent colors [5] |

| Diverging | #4285F4 (low), #FFFFFF (mid), #EA4335 (high) | Z-scores, fold-change values | Neutral midpoint at zero value |

| Categorical | #4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853 | Sample types, experimental conditions | Maximum discrimination between groups |

| Accessibility Check | WCAG 2.0 AA compliance | All color applications | 4.5:1 contrast ratio for text [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Heatmap Generation

| Tool/Package | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ComplexHeatmap (R) | Flexible heatmap visualization | Primary package for annotation integration; supports simple and complex annotations [38] [39] |

| pheatmap (R) | Simplified heatmap generation | Streamlined syntax for standard heatmaps; includes clustering and annotation features [37] |

| DESeq2 (R) | RNA-seq differential expression | Normalization and statistical analysis for count data; generates normalized expression matrices [37] |

| circlize (R) | Color mapping and visualization | Color scale generation for continuous annotations via colorRamp2 function [38] |

| ggplot2 (R) | Data visualization foundation | Preliminary data exploration and quality control plots [37] |

| STAGEs (Web) | Integrated visualization platform | Web-based tool for researchers without coding background; accepts multiple file formats [40] |

| Color Hex | Color palette resources | Repository of proven color schemes for heatmap visualization [41] [42] |

Proper data wrangling for heatmap creation—specifically the careful formatting of expression matrices and annotation dataframes—forms the foundational step in generating biologically meaningful gene expression visualizations. The protocols detailed in this document provide researchers with standardized methodologies for preparing these core components, ensuring that resulting heatmaps accurately represent complex transcriptomic data while facilitating intuitive biological interpretation. By adhering to these specifications for matrix structure, normalization procedures, annotation frameworks, and color palette selection, researchers can create publication-quality visualizations that effectively communicate patterns in gene expression data, ultimately supporting drug development decisions and scientific discovery.

Incorporating Sample and Gene Annotations for Enhanced Biological Context

Heatmaps are an indispensable tool in computational biology, providing an intuitive color-coded representation of complex gene expression data. By visualizing expression levels across multiple samples or experimental conditions, they allow researchers to quickly identify patterns, clusters, and outliers within large datasets. The fundamental strength of a heatmap lies in its ability to transform numerical matrices into visually interpretable formats, where colors represent expression values—typically with red indicating high expression, blue indicating low expression, and gradients representing intermediate values [1].

While basic heatmaps display expression patterns, their biological interpretability remains limited without proper contextual information. The incorporation of sample and gene annotations addresses this critical limitation by adding layers of metadata that bridge the gap between statistical patterns and biological meaning. Sample annotations might include treatment conditions, time points, patient demographics, or disease subtypes, while gene annotations can encompass functional categories, pathway affiliations, or chromosomal locations. This integrated approach transforms a simple visualization into a powerful analytical tool that directly supports hypothesis generation and biological insight [43].

For researchers and drug development professionals, annotated heatmaps provide a comprehensive platform for exploring transcriptomic responses to therapeutic interventions, identifying biomarker candidates, and understanding disease mechanisms. The ability to correlate expression patterns with sample characteristics and gene functions is particularly valuable in precision medicine, where treatment decisions increasingly rely on multidimensional molecular profiling [44].

Data Tables

Table 1: Essential Components for Annotated Heatmap Generation

| Component | Description | Example Tools/Formats | Purpose in Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Matrix | Numerical matrix of expression values (raw counts, normalized, or transformed) | CSV, TSV files; DESeq2, edgeR normalized counts [45] |

Primary quantitative data representing gene activity levels across samples |

| Sample Annotations | Metadata describing experimental conditions, phenotypes, or sample characteristics | Data frame with columns for conditions, time points, treatments [44] | Provides experimental context for interpreting expression patterns |

| Gene Annotations | Functional metadata about genes (pathways, functions, genomic locations) | Biomart, ENSEMBL, KEGG, GO databases [44] | Facilitates biological interpretation of co-expressed gene clusters |

| Clustering Metrics | Algorithms for grouping similar genes and samples | k-means, hierarchical clustering [45] | Identifies co-regulated genes and samples with similar expression profiles |

| Normalization Methods | Statistical approaches to make samples comparable | Z-score scaling, TPM, VST [45] | Removes technical artifacts and enables valid cross-sample comparisons |

| Visualization Parameters | Settings controlling heatmap appearance and layout | Color palettes, dendrogram visibility, annotation positioning [1] | Optimizes visual clarity and facilitates pattern recognition |

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Annotation Impact on Data Interpretability

| Metric | Unannotated Heatmap | Annotated Heatmap | Measurement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Recognition Accuracy | 42% | 78% | User studies measuring correct cluster identification [43] |

| Biological Hypothesis Generation | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | Average testable hypotheses per researcher [44] |

| Analysis Time | 45 ± 12 minutes | 18 ± 6 minutes | Time to derive biological insights from visualized data [45] |