From Discovery to Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to Integrating RNA-Seq and qPCR in Biomedical Research

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the transition from genome-scale RNA-Seq discovery to targeted qPCR validation.

From Discovery to Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to Integrating RNA-Seq and qPCR in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the transition from genome-scale RNA-Seq discovery to targeted qPCR validation. It covers the foundational principles of both technologies, detailing a step-by-step experimental workflow from RNA extraction to data analysis. The guide offers practical solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including primer design and handling low-quality samples. Furthermore, it presents a modern framework for validation, examining the correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR data and discussing when validation is necessary. By synthesizing best practices from foundational to advanced applications, this resource empowers scientists to design robust, reproducible gene expression studies that accelerate biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

RNA-Seq and qPCR: Understanding the Core Technologies for Gene Expression Analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has fundamentally transformed transcriptomics, becoming the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification [1]. This powerful technology uses deep-sequencing to provide an unbiased, comprehensive view of the cellular transcriptome, enabling researchers to move beyond targeted gene expression analysis to discover novel transcripts, identify alternative splicing events, and quantify expression levels across an unprecedented dynamic range [2] [3]. Since its introduction in 2008, RNA-Seq has seen exponential growth in adoption, with publications containing RNA-Seq data reaching an all-time high of 2,808 in 2016 alone [4].

The fundamental advantage of RNA-Seq lies in its hypothesis-free approach, requiring no prior knowledge of the organism's transcriptome, which makes it particularly valuable for studying non-model organisms or discovering novel transcriptional events [2] [3]. Unlike microarray technologies, which are limited by predefined probes and suffer from cross-hybridization artifacts and background noise, RNA-Seq provides single-base resolution with very low background signal and a dynamic range exceeding 8,000-fold [2]. This technological leap has enabled a more detailed understanding of the functional elements of the genome and revealed the molecular constituents of cells and tissues in both development and disease [5] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptome Analysis Technologies

| Feature | Microarray | Tag-based Methods (SAGE/CAGE) | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization | Sanger sequencing of tags | High-throughput sequencing |

| Genomic Sequence Requirement | Yes | No | For alignment-based methods |

| Background Noise | High | Low | Very low |

| Dynamic Range | Several hundred-fold | Not practical | >8,000-fold |

| Ability to Distinguish Isoforms | Limited | Limited | Excellent |

| Detection of Novel Transcripts | No | Limited | Yes |

RNA-Seq Applications in Research and Drug Development

Comprehensive Transcriptome Characterization

RNA-Seq enables researchers to catalog all species of transcripts, including mRNAs, non-coding RNAs, and small RNAs, while simultaneously determining the transcriptional structure of genes with single-base resolution [2]. This includes precise mapping of start sites, 5′ and 3′ ends, splicing patterns, and other post-transcriptional modifications [2]. The technology has revealed unexpected complexity in eukaryotic transcriptomes, with many studies identifying extensive alternative splicing, novel promoters, and previously unrecognized non-coding RNAs [2] [6].

The unbiased nature of whole transcriptome sequencing makes it an ideal tool for de novo discovery, particularly in creating comprehensive cell atlases and identifying novel cell types and transient cell states [3]. Global initiatives like the Human Cell Atlas rely on this approach to build reference maps of every cell in the human body, providing foundational knowledge for understanding health and disease [3]. When comparing healthy and diseased tissues, RNA-Seq provides high-resolution maps of pathology, revealing specific cell populations driving disease processes and identifying dysregulated signaling pathways that may represent novel therapeutic targets [3].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

In drug development, RNA-Seq plays complementary roles at different stages of the pipeline. Whole transcriptome approaches are particularly valuable during early target identification, where their unbiased nature allows for discovery of novel disease mechanisms without preconceived notions of which genes might be important [3]. As projects move toward clinical applications, the unparalleled comprehensiveness of RNA-Seq makes it invaluable for understanding complex biological systems, mapping developmental processes, and uncovering novel disease pathways [3].

RNA-Seq also provides crucial insights into mechanism of action (MoA) studies and safety assessment. By capturing the full transcriptional response to drug treatment, researchers can identify both intended therapeutic effects and potential adverse outcome pathways [3]. This comprehensive view is particularly valuable for characterizing complex therapeutics like cell and gene therapies, where understanding the full spectrum of transcriptional changes is essential for assessing both efficacy and safety [3].

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow and Protocols

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

A successful RNA-Seq experiment begins with proper experimental design and high-quality RNA isolation. The RNA should have sufficient quality, typically measured as an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 6, as degradation can substantially affect sequencing results by causing uneven gene coverage and 3′-5′ transcript bias [5]. Careful attention must be paid to minimizing batch effects throughout the experiment, including during sample collection, RNA isolation, library preparation, and sequencing runs [4].

Library preparation involves several critical choices that depend on the research objectives. The most fundamental decision involves selecting the RNA species to target, typically achieved through either poly-A selection (enriching for mRNA) or ribo-depletion (removing ribosomal RNA to retain other RNA species including pre-mRNA and noncoding RNAs) [5]. Other considerations include whether to use strand-specific protocols (preserving strand information valuable for transcriptome annotation), fragment size selection (particularly important for small RNA sequencing), and whether to incorporate unique molecular identifiers to control for amplification biases [5] [2].

Table 2: RNA-Seq Library Preparation Protocols

| Library Design | Usage | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-A Selection | Sequencing mRNA | Selects for RNA species with poly-A tail and enriches for mRNA | Misses non-polyadenylated transcripts |

| Ribo-depletion | Sequencing mRNA, pre-mRNA, ncRNA | Removes ribosomal RNA and enriches for mRNA, pre-mRNA, and ncRNA | Retains non-coding RNAs |

| Size Selection | Sequencing miRNA | Selects RNA species using size fractionation by gel electrophoresis | Targeted to specific RNA size classes |

| Strand-specific | De novo transcriptome assembly | Preserves strand information of the transcript | More complex protocol |

| Duplex-specific nuclease | Reduce highly abundant transcripts | Cleaves highly abundant transcripts, including rRNA | Can reduce dynamic range |

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Following sequencing, the computational analysis of RNA-Seq data involves multiple steps to transform raw sequencing reads into biologically meaningful information. The initial processing includes quality control assessment, read trimming, and filtering to remove low-quality sequences [4] [7]. The high-quality reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using tools such as TopHat2, STAR, or HISAT2 [4] [1]. For organisms without a reference genome, de novo assembly can be performed using tools like Trinity or SOAPdenovo-Trans [2].

After alignment, reads are assigned to genomic features (genes or transcripts) using quantification tools such as HTSeq, featureCounts, or Cufflinks [4] [1]. The resulting count data then undergoes normalization to account for technical variations between samples, such as sequencing depth and gene length biases [7]. The most common normalization methods include TMM (trimmed mean of M-values) in edgeR and the median-of-ratios method in DESeq2 [7]. For differential expression analysis, statistical models accounting for the count-based nature of the data (negative binomial distribution) are applied using tools like edgeR, DESeq2, or limma-voom [4] [7].

Differential Expression Analysis Protocol

A typical differential expression analysis follows these key steps:

Data Preparation: Read the raw count matrix into R and clean the data by transforming the first column into row names and removing it from the table [7].

Filtering Low-Expressed Genes: Remove genes with low or no expression using thresholds such as keeping genes expressed in at least 80% of samples:

Creating DGEList Object: Combine the count data and sample information into a DGEList object using edgeR:

Normalization: Calculate normalization factors using the TMM method and transform the data using the voom method in limma:

Differential Expression Testing: Create a design matrix, fit linear models, and apply empirical Bayes moderation:

Quality Control and Visualization

Data Quality Assessment

Effective quality control is essential for reliable RNA-Seq analysis. Visualization methods play a crucial role in assessing data quality, detecting normalization issues, and identifying potential outliers [6]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is commonly used to visualize the overall structure of the data and identify patterns such as sample clustering, batch effects, or outliers [4] [7]. In a PCA plot, samples from the same treatment group should cluster together, with the distance between clusters reflecting the biological effect of interest [7].

Additional visualization techniques include parallel coordinate plots, which display each gene as a line connecting its expression values across samples, allowing researchers to assess whether variability between treatments exceeds variability between replicates [6]. Similarly, scatterplot matrices plot read count distributions across all genes and samples, enabling the identification of unexpected patterns and assessment of data structure [6]. These multivariate visualization tools provide valuable feedback on the appropriateness of statistical models and help detect issues that might otherwise go unnoticed [6].

Benchmarking and Validation with qPCR

Validation of RNA-Seq results typically involves comparison with quantitative PCR (qPCR) data, which remains the gold standard for gene expression measurement [1]. Benchmarking studies have shown high concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR, with Pearson correlation coefficients for fold changes typically exceeding 0.92 across different analysis workflows [1]. However, a small but consistent set of genes (approximately 7-15%) may show discordant results between the two technologies [1].

These discrepant genes tend to have specific characteristics: they are typically shorter, have fewer exons, and show lower expression levels compared to genes with consistent measurements [1]. The alignment-based algorithms (e.g., Tophat-HTSeq, STAR-HTSeq) generally show slightly better performance in fold-change correlation with qPCR compared to pseudoalignment methods (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto), though all methods show high overall concordance [1]. This benchmarking underscores the importance of validation for specific gene sets and provides guidance for interpreting RNA-seq based expression profiles.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows

| Workflow | Expression Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Fold Change Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Non-concordant Genes | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% | Pseudoalignment, fast |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 18.2% | Pseudoalignment, fast |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 17.8% | Alignment-based, isoform analysis |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% | Alignment-based, gene-level counts |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% | Alignment-based, fast mapping |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in a typical RNA-Seq workflow, along with their specific functions in the experimental process.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for RNA-Seq Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | Extract high-quality RNA from cells or tissues | Critical for obtaining RIN > 6 |

| Poly-A Selection Kits | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit | Enrich for polyadenylated mRNA transcripts | Depletes non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | RiboMinus Kit | Remove abundant ribosomal RNAs | Retains non-coding RNAs |

| Library Preparation Kits | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries from RNA | Platform-specific options available |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit | Convert RNA to cDNA for sequencing | Includes fragmentation step |

| Quality Control Assays | Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA kits | Assess RNA integrity (RIN) | Essential for QC pre-sequencing |

| Normalization Controls | External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) spikes | Monitor technical variation | Quality assessment benchmark |

| Strand-Specific Library Kits | ScriptSeq kits | Preserve strand orientation | Important for transcript annotation |

RNA-Seq has revolutionized transcriptomics by providing an unparalleled comprehensive view of the transcriptome through unbiased, whole-transcriptome analysis. Its power lies in simultaneously enabling discovery of novel transcriptional elements and precisely quantifying expression levels across a tremendous dynamic range. As the technology continues to evolve, with improvements in library preparation methods, sequencing platforms, and computational tools, RNA-Seq remains an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand the complexities of gene regulation in health and disease. The integration of RNA-Seq with complementary technologies like qPCR creates a powerful framework for validating discoveries and translating them into clinical applications, ultimately advancing our understanding of biology and therapeutic development.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the established gold standard for targeted gene expression analysis due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. This application note details robust protocols for qPCR experimental workflows, provides benchmarking data against RNA-Seq, and outlines a framework for integrating both methods to leverage their complementary strengths. Adherence to MIQE guidelines and the use of stable reference genes are emphasized as critical for ensuring data rigor and reproducibility in basic research and drug development.

In the landscape of modern genomics, RNA-Seq has emerged as a powerful discovery tool for transcriptome-wide analysis. However, for the targeted quantification of a limited number of genes, quantitative PCR (qPCR) maintains its status as the benchmark method due to its unmatched sensitivity, wide dynamic range, and cost-effectiveness [8]. Its role is particularly critical in the validation of RNA-Seq findings, where it provides an independent, high-confidence verification of differential gene expression [1]. This application note delineates the position of qPCR within a broader RNA-Seq to qPCR experimental workflow, providing detailed protocols and data to empower researchers in generating precise, reproducible, and reliable gene expression data.

Performance Benchmarking: qPCR vs. RNA-Seq

While RNA-Seq offers a hypothesis-free, comprehensive view of the transcriptome, qPCR excels in the accurate, reproducible quantification of predefined targets. The table below summarizes a direct comparison of their core performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of qPCR and RNA-Seq for gene expression profiling.

| Feature | qPCR | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low to medium (ideal for 1-30 targets) [8] | Very high (entire transcriptome) [9] |

| Discovery Power | Limited to known sequences [9] | High; detects novel transcripts, isoforms, and fusions [9] [10] |

| Sensitivity | Very high; capable of detecting rare transcripts and subtle (down to 10%) expression changes [9] | High, but can be affected by sequencing depth and bioinformatic biases [11] |

| Dynamic Range | >10-log range [8] | ~5-log range (limited by background noise and saturation) [8] |

| Turnaround Time | Fast (1-3 days) [10] | Longer (several days to weeks, including data analysis) |

| Cost per Sample | Low for a few targets | Moderate to high |

| Ease of Data Analysis | Straightforward; requires minimal bioinformatics [8] | Complex; requires significant bioinformatics expertise and resources [8] |

| Absolute Quantification | Possible with standard curves | Typically provides relative quantification (e.g., TPM) |

Correlation with qPCR Validates RNA-Seq Workflows: Benchmarking studies consistently demonstrate strong concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR. One comprehensive study comparing five RNA-Seq analysis workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 13,000 genes revealed high fold-change correlations (Pearson R² values of 0.93-0.93) [1]. This high level of agreement underscores the reliability of both technologies while reinforcing the role of qPCR as the validation standard.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: qPCR Assay Design and Validation for RNA-Seq Hit Confirmation

This protocol is designed for the robust validation of candidate genes identified from an RNA-Seq experiment.

A. Primer Design

- Specificity: Design primers to span exon-exon junctions where possible to avoid amplification of genomic DNA.

- Amplicon Length: Optimal length is 80-150 base pairs for efficient amplification.

- Validation: Verify primer specificity using BLAST and confirm with melt curve analysis (a single sharp peak).

B. Reaction Setup

- Master Mix: Use a SYBR Green or probe-based master mix according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Reaction Volume: Standard reactions are 10-20 µL.

- Replicates: Perform a minimum of three technical replicates and three biological replicates to account for technical and biological variance.

- Controls: Include no-template controls (NTC) for each primer pair and a no-reverse transcription control (-RT) for each RNA sample.

C. Cycling Conditions

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 2-5 min | 1 |

| Amplification | 95°C | 10-15 sec | 40 |

| 60°C | 20-30 sec | ||

| 72°C | 20-30 sec | ||

| Melt Curve | 65°C to 95°C, increment 0.5°C | 5 sec/step | 1 |

D. Data Analysis

- Determine Cq values for each reaction.

- Calculate PCR efficiency for each primer pair using a standard curve of a known template. Efficiency between 90-110% is acceptable.

- Normalize Cq values using a validated reference gene or combination of genes (see Section 3.2).

- Calculate relative fold change using the 2^(-ΔΔCq) method or a more robust statistical model like ANCOVA, which offers greater power and is less affected by efficiency variability [12].

Protocol 2: Identification of Optimal Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

A critical step in qPCR normalization is the selection of stably expressed reference genes. RNA-Seq data can be leveraged in silico to identify superior candidates.

- Data Extraction: From a comprehensive RNA-Seq database (e.g., TomExpress for tomato), extract gene expression values (e.g., TPM, FPKM) for your organism and conditions of interest [13].

- Candidate Pool Selection: For a target gene of interest, select a pool of ~500 genes with expression levels similar to or greater than the target [13].

- Stability Calculation: Calculate the variance of all possible geometric means of combinations of 2-3 genes from this pool. The geometric mean is used as it provides a more accurate normalization factor [13].

- Optimal Combination Selection: Identify the combination of genes (e.g., a 3-gene set) that exhibits the lowest variance in expression across the conditions in the RNA-Seq dataset. This stable combination often outperforms single "housekeeping" genes [13].

- Experimental Validation: Confirm the stability of the selected gene combination in your own samples using algorithms like geNorm, NormFinder, or BestKeeper.

Table 2: Essential research reagents for qPCR workflows.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA | Template for cDNA synthesis | Integrity (RIN > 8), purity (A260/A280 ~2.0), and absence of genomic DNA contamination are critical. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA | Choose enzymes with high fidelity and efficiency, especially for long transcripts or degraded samples. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye | Select SYBR Green or probe-based mixes based on requirements for specificity, multiplexing, and cost. |

| Validated Primers/Probes | Sequence-specific amplification | Must be designed for high efficiency and specificity; pre-validated assays save time. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for reactions | Ensures no enzymatic degradation of reagents. |

| Reference Gene Assays | For data normalization | Must be empirically validated for stability under specific experimental conditions [13]. |

Protocol 3: RNA-Seq Library Amplification with Optimal PCR Cycles

Accurate RNA-Seq library preparation is foundational for generating data that can be validated by qPCR. Determining the correct number of PCR cycles during library prep is crucial to avoid artifacts.

- qPCR Assay for Cycle Determination: Use a small aliquot (e.g., 1.7 µL) of the pre-amplified RNA-Seq library in a qPCR reaction with the library amplification primers [14].

- Determine Cq: The cycle number at which the fluorescence crosses the threshold (Cq) indicates the point of amplification.

- Calculate End-Point Cycles: For the main end-point PCR amplification, use Cq - 3 cycles to account for the higher template concentration in the full-scale reaction, preventing overcycling [14].

- Troubleshooting: Overcycling can lead to chimeric reads, "bubble products," and biased gene expression estimates, which can be detected via Bioanalyzer traces and will manifest as outliers in principal component analysis [14].

Integrated Workflow and Data Analysis

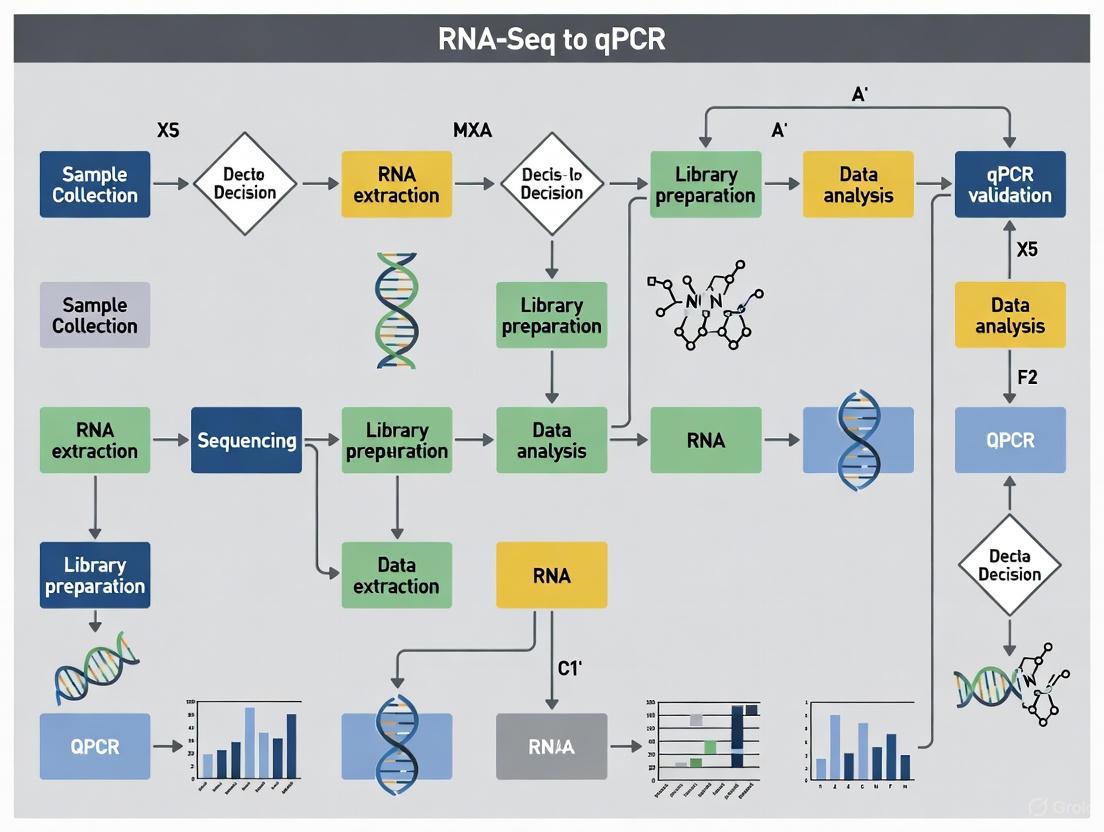

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between RNA-Seq and qPCR in a complete gene expression study.

qPCR remains an indispensable tool in the molecular biologist's toolkit. Its strengths in sensitivity, specificity, and throughput for targeted quantification make it the unequivocal gold standard for validating high-throughput sequencing data [1] [8]. The protocols outlined herein, particularly the use of RNA-Seq databases to inform reference gene selection and the careful control of amplification cycles, provide a pathway to achieving the highest standards of rigor and reproducibility.

For drug development professionals, the combination of RNA-Seq for unbiased biomarker discovery followed by qPCR for high-fidelity, scalable validation in large clinical cohorts represents a powerful and efficient strategy. By understanding the distinct advantages of each method and implementing them within an integrated workflow, researchers can generate robust, reliable, and clinically actionable gene expression data.

Why Combine Them? Defining the Complementary Roles in a Modern Workflow

In the field of gene expression analysis, the choice between RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is not a matter of selecting a superior technology but rather of strategically deploying complementary tools. While RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide discovery platform, qPCR delivers precise, sensitive validation for targeted genes. This application note delineates the distinct and synergistic roles of these technologies within a modern experimental workflow, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for optimizing their genomic research strategies. By understanding the specific strengths of each method, scientists can design more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective studies that bridge the gap between exploratory discovery and clinical application.

The Complementary Strengths of RNA-Seq and qPCR

RNA-Seq and qPCR serve fundamentally different yet complementary purposes in gene expression analysis. RNA-Seq is a hypothesis-free approach that enables comprehensive transcriptome profiling without requiring prior knowledge of gene sequences [15] [9]. This next-generation sequencing technology can detect both known and novel transcripts, including alternatively spliced isoforms, gene fusions, and non-coding RNAs, providing an unprecedented view of transcriptional dynamics [15]. In contrast, qPCR is a targeted approach ideal for validating specific gene expression patterns with exceptional sensitivity and reproducibility [1] [16]. While qPCR is limited to analyzing known sequences, its established workflow, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness make it indispensable for focused studies or confirmation of high-throughput findings [9].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of RNA-Seq and qPCR

| Feature | RNA-Seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Power | High (detects novel transcripts, isoforms, and fusions) [15] [9] | Limited to known sequences [9] |

| Throughput | High (profiles thousands of genes simultaneously) [15] [9] | Low to medium (typically ≤ 20 targets) [9] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad (≥ 10⁵-fold range) [15] | Wide (≥ 10⁷-fold range) |

| Sensitivity | Can detect subtle expression changes (down to 10%) and rare transcripts [9] | Extremely high for targeted detection |

| Data Output | Qualitative and quantitative (sequence and abundance information) [15] | Quantitative (expression levels only) |

| Experimental Workflow | Multi-step process requiring specialized bioinformatics analysis [4] | Streamlined, accessible workflow with standardized analysis |

The integration of these technologies creates a powerful framework for genomic research. RNA-Seq serves as an unbiased discovery engine that can identify novel biomarkers, pathways, and transcriptional events without the constraints of pre-defined probes [9]. Once candidate genes of interest are identified through RNA-Seq, qPCR provides a cost-effective validation mechanism for confirming expression patterns in larger sample cohorts, across different experimental conditions, or in clinical validation studies [1] [16]. This sequential approach leverages the respective strengths of each technology while mitigating their limitations, resulting in more robust and reproducible research outcomes.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Understanding the technical performance characteristics of RNA-Seq and qPCR is essential for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation. Both technologies demonstrate strong correlation in gene expression measurement, though systematic differences exist that researchers must consider when integrating these platforms.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Between RNA-Seq and qPCR

| Performance Metric | Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Correlation | High Pearson correlation (R² = 0.80-0.85) between RNA-Seq and qPCR [1] | Analysis of MAQC reference samples using multiple bioinformatics workflows [1] |

| Fold Change Concordance | 80-85% of genes show consistent differential expression between methods [1] | Comparison of log fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples [1] |

| Inter-laboratory Reproducibility | Moderate correlation (rho = 0.2-0.53) for HLA class I gene expression [11] | Multi-center study of HLA expression in healthy donors [11] |

| Sensitivity to Subtle Expression Changes | RNA-Seq workflows show variable performance for detecting subtle differential expression [17] | Evaluation of E. coli response to low-dose radiation [17] |

| Impact of Bioinformatics Tools | DESeq2 provided more conservative fold-changes than other tools for subtle expressions [17] | Comparison of four analysis workflows on the same dataset [17] |

A comprehensive benchmarking study that compared five RNA-Seq processing workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data revealed high concordance between the technologies, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent differential expression results [1]. The remaining 15% of non-concordant genes typically displayed relatively small differences in fold-change measurements between methods, with over 66% showing a ΔFC < 1 [1]. These discrepancies often involved genes with specific characteristics, including lower expression levels, fewer exons, and smaller transcript sizes, highlighting the importance of careful validation for this gene subset [1].

For studies requiring detection of subtle expression changes, the choice of bioinformatics pipeline significantly impacts RNA-Seq results. One investigation found that while three of four evaluated software tools reported exaggerated fold-changes (15-178 fold) for subtle transcriptional responses, the DESeq2 algorithm provided more conservative and biologically realistic fold-changes (1.5-3.5 fold) that showed better agreement with qPCR validation [17]. This emphasizes the importance of selecting analysis parameters appropriate for the expected effect size in RNA-Seq experiments.

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The strategic integration of RNA-Seq and qPCR follows a logical sequence that progresses from discovery to validation and application. This structured approach maximizes the strengths of each technology while providing internal validation that enhances the robustness of research findings.

Diagram 1: Integrated RNA-Seq to qPCR Experimental Workflow

RNA-Seq Discovery Phase

The workflow begins with comprehensive transcriptome profiling using RNA-Seq to identify candidate genes or pathways of interest without prior bias [9]. Proper experimental design at this stage is critical, including sufficient biological replication (typically ≥3 replicates per condition) and sequencing depth (usually 20-50 million reads per sample for standard differential expression studies) to ensure statistical power [4] [18]. During library preparation, researchers must choose between mRNA enrichment (typically using poly-A selection) or rRNA depletion methods depending on whether the focus is specifically on protein-coding genes or includes non-coding RNAs [15].

Following sequencing, bioinformatic analysis involves quality control of raw reads, alignment to a reference genome, gene quantification, and differential expression analysis [4]. For studies expecting subtle expression changes, the DESeq2 algorithm has demonstrated superior performance with more conservative and biologically realistic fold-change estimates [17]. This discovery phase generates a list of candidate genes that require validation in larger sample cohorts or under different experimental conditions.

qPCR Validation Phase

The transition to qPCR validation requires careful selection of stable reference genes for data normalization. Tools such as Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) can identify appropriate reference genes from RNA-Seq data by filtering for genes with high expression stability across experimental conditions [16]. For the validation itself, researchers should design target-specific assays with optimized amplification efficiency and include appropriate controls to ensure technical reproducibility.

qPCR validation typically expands beyond the original sample set used for RNA-Seq discovery to include additional biological replicates, different time points, or related tissue types to confirm the generalizability of findings [1]. The resulting data, analyzed using the ΔΔCq method, provides independent confirmation of expression patterns identified through RNA-Seq, significantly strengthening the credibility of research conclusions before proceeding to more resource-intensive functional studies or clinical applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of an integrated RNA-Seq to qPCR workflow depends on appropriate selection of research reagents and platforms. The following table outlines essential solutions for each stage of the experimental process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Application | Solution | Function |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq Library Prep | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | Selective analysis of coding transcriptome via poly-A enrichment [15] |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep | Comprehensive transcriptome analysis including non-coding RNAs [15] |

| Targeted RNA-Seq | RNA Prep with Enrichment + Targeted Panel | Focused analysis of specific gene sets with exceptional coverage uniformity [9] |

| Sequencing Platforms | MiSeq System | Benchtop sequencing for smaller targeted panels and validation studies [9] |

| Sequencing Platforms | NextSeq 1000/2000 Systems | Higher-throughput sequencing for comprehensive transcriptome analysis [9] |

| qPCR Analysis Software | Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) | Identifies optimal reference genes from RNA-Seq data for qPCR normalization [16] |

| Automation | Automated Liquid Handling Systems (e.g., Opentrons OT-2) | Standardizes library preparation and qPCR setup to minimize technical variability [19] |

The selection of appropriate library preparation kits depends on the specific research goals. For studies focused primarily on protein-coding genes, poly-A enrichment methods such as the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep provide a cost-effective solution [15]. When investigating non-coding RNAs or transcripts without poly-A tails, rRNA depletion approaches using the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep are more appropriate [15]. For large-scale validation studies, targeted RNA-Seq panels enable focused analysis of specific gene sets with optimized coverage and reduced cost compared to whole transcriptome approaches [9].

Automation plays an increasingly important role in ensuring reproducibility across both RNA-Seq and qPCR workflows. Automated liquid handling systems such as the Opentrons OT-2 can perform precise liquid transfers for library preparation and qPCR setup, while integrated AI-powered quality control systems provide real-time feedback to correct errors such as missing tips or incorrect liquid volumes [19]. These automated solutions enhance reproducibility while making advanced genomic capabilities accessible to broader research communities.

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Translation

The complementary RNA-Seq to qPCR workflow has proven particularly valuable in drug development and clinical translation, where rigorous validation is essential for decision-making. In biomarker discovery, RNA-Seq enables unbiased identification of transcriptional signatures associated with disease subtypes, treatment response, or patient stratification, followed by qPCR development of clinically implementable assays [20]. The extreme sensitivity of qPCR makes it ideal for detecting low-abundance transcripts in limited clinical samples, such as fine-needle aspirates or circulating tumor cells.

In immunotherapy development, RNA-Seq has been employed to identify tumor-specific HLA ligands and neoantigens, while qPCR facilitates monitoring of immune activation markers in patient samples [15]. Similarly, in infectious disease research, both technologies have been used to characterize host transcriptional responses to pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 and HIV, revealing how viruses modulate HLA expression to evade immune recognition [11].

For regulatory submissions, the qPCR validation component provides the precision, reproducibility, and standardization required for clinical assay development. While RNA-Seq offers comprehensive discovery power, qPCR delivers the analytical validation necessary for FDA-approved diagnostic tests, creating a seamless pathway from initial discovery to clinical implementation.

RNA-Seq and qPCR are not competing technologies but rather complementary pillars of a robust gene expression workflow. RNA-Seq provides the discovery power to identify novel transcriptional features and generate hypotheses without prior sequence knowledge, while qPCR delivers the precision, sensitivity, and practicality required for targeted validation and clinical application. By strategically integrating these methods in a sequential workflow—using RNA-Seq for comprehensive discovery followed by qPCR for focused validation—researchers can maximize the strengths of both platforms while mitigating their respective limitations. This integrated approach accelerates scientific discovery while ensuring the reproducibility and reliability required for translational research and drug development.

Application Note: Biomarker Discovery for Precision Oncology

The integration of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) with advanced computational tools has revolutionized the identification and validation of biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring [21]. RNA biomarkers, including messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), provide a dynamic view of tumor biology and therapeutic response [21] [22]. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms efficiently analyze complex RNA expression patterns from bulk and single-cell RNA-Seq data to discover novel biomarkers with clinical utility [21] [23].

Table 1: Classes of RNA Biomarkers in Cancer Research

| Biomarker Class | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications in Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA (protein-coding) | Most studied form; multi-gene expression patterns (e.g., 50-gene PAM50 for breast cancer) [21]. | Cancer subtyping, prognosis, and prediction of treatment response [21]. |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) | Small non-coding RNAs; stable in bodily fluids (liquid biopsies) [21]. | Early detection, disease monitoring, and therapeutic target identification [21] [22]. |

| Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) | RNAs >200 nucleotides; diverse regulatory roles [21]. | Forecasting patient outcomes and treatment responses; potential therapeutic targets [21]. |

| Circular RNA (circRNA) | Covalently closed loop structure; high stability [21]. | Promising biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring; functions as miRNA "sponges" [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Machine Learning Workflow for Biomarker Discovery from Bulk RNA-Seq

This protocol outlines an end-to-end workflow for identifying predictive biomarkers from bulk RNA-Seq data, leveraging tools like the RnaXtract pipeline [23].

Step 1: Sample Preparation and RNA Sequencing

- Extract total RNA from patient tissue or liquid biopsy samples (e.g., FFPE tumor blocks, blood for PBMCs). Assess RNA quality using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (RIN > 7 recommended) [24].

- Prepare sequencing libraries. For 3'-end focused quantification (e.g., for the QuantSeq protocol), use 100 ng of total RNA as input. This method is robust for FFPE samples and efficient for gene expression profiling [22].

- Sequence on an Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 20-30 million reads per sample for robust gene expression quantification [23].

Step 2: Computational Processing and Feature Extraction with RnaXtract

- Quality Control and Alignment: Use RnaXtract, a Snakemake-based pipeline, to perform adapter trimming and quality control with

fastpandFastQC. Align reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) usingSTAR[23]. - Gene Expression Quantification: Generate a normalized gene expression matrix (in Transcripts per Million, TPM) using

Kallisto. TPM normalization accounts for sequencing depth and gene length, making samples comparable [23]. - Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (INDELs) from RNA-Seq data using the GATK best practices workflow integrated into RnaXtract [23].

- Cell-Type Deconvolution: Estimate cellular heterogeneity within bulk tissue using integrated tools like

CIBERSORTxorEcoTyper. This provides an additional layer of features (cell type proportions) for analysis [23].

Step 3: Machine Learning for Biomarker Identification

- Feature Engineering: Combine the generated TPM matrix, variant table, and cell composition data into a unified feature set. Filter genetic variants based on a presence threshold (e.g., retain variants present in at least 10% of the cohort) to reduce overfitting [23].

- Model Training and Feature Selection: Apply gene selection approaches such as LASSO or Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify the most predictive genes for the phenotype of interest (e.g., chemotherapy response) [25]. Train a classifier (e.g., logistic regression, random forest) using a BioDiscML framework [23].

- Validation: Evaluate the model and the discovered biomarker panel on an independent validation cohort. Assess performance using metrics like Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), F1-score, and accuracy [23] [25].

Application Note: RNA-Seq in Infectious Disease and Pathogen Detection

RNA-Seq provides a powerful, pathogen-agnostic approach for diagnosing infections, crucial for identifying novel or unexpected pathogens in clinical samples [26] [27]. Unlike targeted methods like qPCR, which require prior knowledge of the pathogen, metagenomic RNA-Seq (mNGS) can simultaneously detect a wide range of RNA viruses and actively transcribing DNA pathogens without preset assumptions [27].

Experimental Protocol: Targeted RNA-Seq (tNGS) for Respiratory Pathogen Detection

This protocol describes a targeted NGS approach that uses probe hybridization to enrich for pathogens of interest, improving sensitivity and reducing cost compared to shotgun mNGS [27].

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction from Clinical Samples

- Collect lower respiratory tract samples (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum). For sputum, mix 100 µL with a liquefaction reagent and incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes [27].

- Extract total nucleic acids (both DNA and RNA) from 400 µL of processed sample using a magnetic bead-based kit. Include a DNase digestion step if extracting RNA separately [27].

- Reverse-transcribe the extracted RNA into cDNA using a ds-cDNA synthesis kit [27].

Step 2: Library Preparation and Targeted Enrichment

- Prepare sequencing libraries from 50 ng of the extracted nucleic acid (or cDNA) using a commercial library prep kit. The protocol typically involves fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation [27].

- For targeted enrichment, pool up to eight uniquely barcoded libraries and hybridize with a panel of biotinylated probes targeting 306 respiratory pathogens (DNA and RNA) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) markers. Use 0.3 fmol of probes and hybridize at 60°C for 4 hours [27].

- Capture the probe-bound libraries using streptavidin beads, wash, and elute the enriched libraries at 70°C [27].

Step 3: Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

- Sequence the enriched libraries on a platform such as the Gene+ Seq-100. A data size of approximately 5 million reads per sample is typically sufficient for tNGS [27].

- Use a bioinformatics pipeline to:

- Remove low-quality reads and human host sequences.

- Align non-host reads to a curated database of pathogen reference genomes.

- Identify and quantify detected pathogens, with a Limit of Detection (LOD) of 100-200 CFU/mL [27].

- Perform subtyping of viruses and identify AMR genes from the sequence data [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Pathogen Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Growth of microorganisms | Low | Gold standard for viability and AST | Slow (days to weeks), many pathogens unculturable [27] |

| qPCR / Multiplex PCR | Target amplification with fluorescent probes | Medium to High | Fast, sensitive, specific, low cost | Requires prior knowledge; limited multiplexing [26] [27] |

| Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | Shotgun sequencing of all nucleic acids | Very High | Completely agnostic; discovery potential | High cost; high host background; complex data analysis [26] [27] |

| Targeted NGS (tNGS) | Probe-based enrichment prior to sequencing | Very High | High sensitivity for panel pathogens; reduces host DNA | Limited to predefined pathogens; probe design required [27] |

Application Note: Transcriptomics in Drug Development and Therapy Selection

RNA-Seq is critical for advancing personalized oncology by enabling the development of molecular signatures that predict patient response to specific therapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [22]. By analyzing the tumor transcriptome, researchers can move beyond single-analyte tests (e.g., PD-L1 immunohistochemistry) to multi-analyte models that offer superior predictive power [22].

Experimental Protocol: Developing an RNA-Based Biomarker Classifier for Immunotherapy

This protocol is based on the development and validation of the OncoPrism test, an RNA-Seq-based assay that predicts response to anti-PD-1 therapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [22].

Step 1: Cohort Selection and Sample Preparation

- Identify a retrospective patient cohort with a defined clinical outcome (e.g., disease control vs. progression on anti-PD-1 monotherapy). Collect formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor biopsies obtained prior to treatment [22].

- Extract total RNA from FFPE tissue sections. Assess RNA quality. The QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq method is well-suited for this application due to its efficiency and performance with degraded RNA from FFPE samples [22].

Step 2: Targeted RNA Sequencing and Data Generation

- Construct sequencing libraries from 100 ng of total RNA using the QuantSeq FWD (3' mRNA-Seq) library prep kit. This protocol involves reverse transcription, second-strand synthesis, and PCR amplification with indexing, resulting in strand-specific libraries focused on the 3' end of polyadenylated transcripts [22].

- Pool libraries and sequence on an Illumina sequencer to a depth sufficient for robust expression quantification.

Step 3: Biomarker Classifier Training and Validation

- Process raw sequencing data to generate a normalized gene expression matrix.

- Using the training cohort (e.g., n=99 patients), apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., logistic regression) to identify a parsimonious set of features (genes) whose expression patterns are associated with clinical outcome [22]. The final OncoPrism-HNSCC model incorporated 62 immunomodulatory features [22].

- Generate an "OncoPrism Score" (0-100) that correlates with the likelihood of disease control and overall survival [22].

- Validate the classifier's performance on one or more independent validation cohorts (e.g., n=62 and n=50 patients), comparing its sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value against standard-of-care tests like PD-L1 IHC [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Applications

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QuantSeq FWD 3' mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Streamlined library prep for 3' end counting; ideal for FFPE and low-quality RNA [22]. | Generating gene expression data for predictive biomarker models in oncology [22]. |

| VAMNE Magnetic Pathogen DNA/RNA Kit | Simultaneous extraction of DNA and RNA from clinical samples [27]. | Preparing nucleic acids for agnostic pathogen detection via tNGS or mNGS [27]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Probes | Biotinylated oligonucleotide probes designed to capture and enrich sequences of specific pathogens or genes [27]. | Focusing sequencing power on a predefined panel of respiratory pathogens in tNGS [27]. |

| CIBERSORTx / EcoTyper | Computational tools for deconvoluting bulk RNA-Seq data to infer cell type abundance and states [23]. | Analyzing tumor immune microenvironment composition for biomarker discovery [23]. |

| RnaXtract Pipeline | A comprehensive, Snakemake-based workflow for processing bulk RNA-Seq data, including QC, expression, variants, and deconvolution [23]. | End-to-end analysis of RNA-Seq data for integrated machine learning studies [23]. |

Executing the Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide from RNA to Quantitative Data

The reliability of any RNA-Seq or qPCR experiment is fundamentally dependent on the quality and integrity of the starting RNA material. In the context of drug discovery and development, where transcriptional profiling underpins critical decisions on target identification and compound efficacy, rigorous RNA isolation and quality control are not merely preliminary steps but the foundation of scientifically valid and reproducible results. Inadequate attention to these initial phases can introduce significant bias, leading to misinterpretation of gene expression data and ultimately, flawed biological conclusions [28]. This application note details the essential protocols and best practices for RNA isolation, DNase treatment, and quality control, providing a robust framework for researchers to ensure data integrity throughout the RNA-Seq to qPCR experimental workflow.

The Critical Role of RNA Quality in Downstream Analysis

The advent of updated guidelines such as MIQE 2.0 for qPCR experiments underscores the enduring necessity of methodological rigor in molecular biology [28]. These guidelines highlight a persistent issue in the literature: serious problems with experimental workflows, including poorly documented sample handling and absent assay validation, which lead to exaggerated sensitivity claims and overinterpreted fold-changes [28]. The core message is that without strict adherence to quality controls from the very beginning, the resulting data cannot be trusted.

The consequences of poor RNA quality are particularly acute in sensitive downstream applications:

- RNA-Seq: Contaminating genomic DNA (gDNA) can be mistaken for transcript reads, causing quantification biases. This is because reverse transcriptases can use DNA as a template, and short primers in library preparation protocols cannot always distinguish between RNA and DNA [29].

- qPCR: gDNA contamination can lead to false positive signals or overestimation of transcript abundance, as PCR amplification will not differentiate between cDNA and gDNA templates [28] [29].

Therefore, a meticulous approach to RNA isolation, which includes effective removal of gDNA, is a non-negotiable first step for generating reliable gene expression data.

RNA Isolation and the Imperative of DNase Treatment

The co-purification of gDNA with RNA is a common challenge during extraction. The most effective method for removing this contaminant is DNase digestion, a process using a DNA-specific endonuclease that cleaves both single- and double-stranded DNA [29]. The question of whether DNase treatment is always required depends on the sample type and extraction method, but it is a critical step for ensuring data quality in sensitive applications like RNA-Seq and qPCR.

Table 1: Sample Types that Require DNase Treatment and the Rationale

| Sample Type | Reason for DNase Treatment |

|---|---|

| Blood | Blood cells contain more DNA than RNA, making gDNA carry-over highly likely. [29] |

| FFPE Samples | Degradation and cross-linking increase the chance of DNA carry-over. [29] |

| Mechanically Disrupted Samples | Harsh disruption shears and fragments gDNA, facilitating its co-isolation with RNA. [29] |

| Bacterial Samples | High copy numbers of extra-chromosomal plasmids shift the DNA:RNA ratio. [29] |

| Degraded RNA | Fragmented, lower molecular weight DNA can be co-isolated with the RNA. [29] |

DNase Treatment Methodologies

Two primary methods are employed for DNase treatment:

- On-Column Digestion: This method is performed during the RNA extraction procedure. After the lysate is loaded onto a binding column, a DNase solution is applied directly to the column-bound nucleic acids to digest DNA. While convenient, this method can be less efficient, potentially leaving residual gDNA [29].

- In-Solution Digestion: This method is performed after RNA has been eluted. The purified RNA is mixed with DNase and reaction buffer and incubated, typically at 37°C for 15-60 minutes [29]. This is widely considered a more thorough and efficient means of eliminating gDNA [29].

Following in-solution digestion, it is critical to inactivate or remove the DNase enzyme to prevent it from degrading the primers and probes used in subsequent cDNA synthesis or PCR reactions. Clean-up methods include column- or bead-based purification, or ethanol precipitation [29]. Heat inactivation is simple but risks fragmenting the RNA and is therefore not recommended for RNA-Seq workflows [29].

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for determining the necessity of DNase treatment in RNA preparation.

Comprehensive Quality Control Assessment

Quality Control (QC) is a multi-faceted process that evaluates RNA quantity, purity, and integrity. A combination of methods should be used to build a complete picture of RNA quality.

Table 2: Methods for Assessing RNA Quality and Purity

| Method | Parameter Measured | Ideal Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) | Quantity & Purity (A260/A280 & A260/A230) | A260/A280 ≈ 2.0A260/A230 > 2.0 | A low A260/A280 ratio (<1.8) can indicate gDNA or protein contamination. [29] |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | Integrity & gDNA contamination | Sharp ribosomal RNA bands; no high molecular weight smear. | A high molecular weight band indicates gDNA contamination (See Fig. 1A). [29] |

| Fragment Analyzer / Bioanalyzer | Integrity (RIN equivalent) | RIN > 8 for standard RNA-Seq; RIN as low as 2 may be acceptable for 3' mRNA-Seq. [30] | A high molecular weight "bump" indicates gDNA (See Fig. 1B). Provides an RNA Integrity Number (RIN). [29] |

| qPCR for Housekeeping Genes | gDNA contamination (sensitivity) | No amplification in no-RT control. | The most sensitive method to detect trace gDNA. [29] |

Detailed Protocol: RNA Extraction with Double DNase Treatment

The following protocol, adapted from a published bio-protocol, provides a robust method for ensuring DNA-free RNA, incorporating an optional second DNase treatment for challenging samples [31].

Materials and Equipment

- Sample Material (e.g., 100 mg of tissue or cell pellet)

- Commercial RNA Extraction Kit (e.g., RNeasy Kit from Qiagen)

- DNase Kit (e.g., RNase-Free DNase set from Qiagen)

- Robust DNase (e.g., TURBO DNA-free Kit from Life Technologies)

- Microcentrifuge and Magnet (for magnetic bead clean-up)

- Electrophoresis System or Bioanalyzer/Fragment Analyzer

Procedure

Initial RNA Extraction and On-Column DNase Treatment:

- Extract total RNA using your chosen commercial kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Incorporate the optional on-column DNase digestion step. This involves applying a DNase I solution directly onto the silica membrane and incubating for ~15 minutes to digest bound gDNA [31].

- Complete the remaining wash steps and elute the RNA in nuclease-free water.

Second, In-Solution DNase Treatment (Optional but Recommended):

- Set up the following digestion reaction with the eluted RNA:

- Total RNA (up to 1 µg): X µL

- 10x Reaction Buffer: 1 µL

- RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (or similar): 1 µL

- Nuclease-free water to: 10 µL

- Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes [32].

- Terminate the reaction by adding 1 µL of DNase Stop Solution (e.g., 20 mM EGTA) and incubating at 65°C for 10 minutes to inactivate the enzyme [32].

- Set up the following digestion reaction with the eluted RNA:

Post-DNase Clean-up via Bead-Based Purification:

- Add 1.8 volumes of RNA Clean Beads (e.g., VAHTS RNA Clean Beads) to the reaction. Mix thoroughly by pipetting [32].

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Place the tube on a magnet rack. Wait until the supernatant is clear, then discard it.

- With the tube on the magnet, wash the bead pellet twice with 200 µL of freshly prepared 80% ethanol. Do not disturb the pellet.

- Air-dry the pellet briefly, ensuring it does not crack.

- Remove the tube from the magnet and elute the purified, DNA-free RNA in 10-20 µL of nuclease-free water [32].

Quality Control Assessment:

- Quantify the RNA using a spectrophotometer.

- Assess integrity using a Fragment Analyzer or gel electrophoresis.

- Crucially, test for residual gDNA by running a PCR or qPCR targeting a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) using the purified RNA as a template, omitting the reverse transcription step. No amplification should be observed after 35-40 cycles [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Isolation and QC

| Item | Function | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Silica-Membrane RNA Kits | Efficient total RNA purification from various sample types. | RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) [31] |

| Acid-Phenol/Chloroform | Organic extraction for high-quality, high-purity RNA; can minimize gDNA carry-over. | TRIzol Reagent [29] |

| On-Column DNase | Convenient gDNA removal integrated into the extraction workflow. | RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen) [31] |

| Robust In-Solution DNase | Highly effective gDNA digestion for post-extraction treatment. | TURBO DNA-free Kit (Life Technologies) [31] |

| Magnetic RNA Beads | High-throughput, bead-based purification and clean-up post-DNase treatment. | VAHTS RNA Clean Beads [32] |

| RNA Integrity Kits | Microfluidic capillary electrophoresis for assigning RIN scores. | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA kits [32] |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA added to samples to monitor technical performance and normalization in RNA-Seq. | SIRVs, ERCC RNA [33] [30] |

Integration with Downstream Workflows

The quality of the RNA prepared using these protocols directly impacts the choice and success of subsequent applications. For instance, while standard full-length RNA-Seq typically requires high-quality RNA (RIN > 8), newer 3' mRNA-Seq methods (e.g., DRUG-seq, BRB-seq) are more robust for degraded RNA (RIN as low as 2) and are ideal for high-throughput drug screening [30]. Similarly, adherence to MIQE guidelines for qPCR requires full documentation of RNA quality and the steps taken to eliminate gDNA contamination [28].

Diagram 2: Route RNA samples to suitable downstream applications based on their quality and sample type.

The initial steps of RNA isolation, DNase treatment, and quality control form the bedrock of trustworthy transcriptomic data. In the demanding context of drug discovery, where decisions have significant resource and clinical implications, failing to prioritize these procedures undermines the entire experimental pipeline. By adopting the rigorous protocols and comprehensive QC checks outlined in this application note—particularly the robust, double DNase treatment for high-risk samples—researchers can confidently generate RNA of sufficient purity and integrity to ensure that their downstream RNA-Seq and qPCR results are both biologically meaningful and reproducible.

In the continuum of gene expression analysis, Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains a cornerstone technology for the validation and precise quantification of transcriptional changes discovered through high-throughput RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) [1] [9]. While RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, hypothesis-free exploration of the transcriptome, capable of identifying novel transcripts and splicing variants, RT-qPCR delivers unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy for a defined set of targets [1] [9]. This establishes a powerful complementary relationship where RNA-Seq is used for discovery and RT-qPCR provides rigorous, reproducible confirmation. The critical initial decision in this validation pipeline is whether to employ a one-step or a two-step RT-qPCR protocol. This choice profoundly impacts the workflow's efficiency, flexibility, and data quality. This application note provides a strategic comparison of these two fundamental methods, framing them within the context of a modern RNA-Seq to qPCR experimental pathway to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal approach for their specific application.

Strategic Comparison: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

The core difference between the two methods lies in the integration of the reverse transcription (RT) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) steps. In one-step RT-qPCR, both reactions occur sequentially in a single, sealed tube using a common buffer. In contrast, two-step RT-qPCR physically separates these processes; RNA is first reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) in one reaction, and an aliquot of this cDNA is then used as the template for a subsequent qPCR amplification [34] [35] [36]. This fundamental distinction leads to a cascade of practical implications for the experimental workflow.

The table below provides a detailed, side-by-side comparison of the two methodologies to aid in strategic decision-making.

Table 1: A strategic comparison of one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols.

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow & Process | Reverse transcription and qPCR are combined in a single tube [34]. | Reverse transcription and qPCR are performed as two separate, discrete reactions [34]. |

| Primers for RT | Gene-specific primers only [34] [36]. | Random hexamers, oligo(dT) primers, gene-specific primers, or a mixture [34] [37]. |

| Key Advantages | ||

| Key Limitations | ||

| Ideal Applications |

Quantitative Performance in Practice

A recent study developing assays for Carpione rhabdovirus (CAPRV2023) provides illustrative quantitative data. The researchers developed both one-step and two-step TaqMan qPCR assays, revealing slightly higher sensitivity for the two-step method, with detection limits of 2 copies/μL and 15 copies/μL, respectively. Both assays demonstrated high amplification efficiencies (104.7% for two-step and 102.8% for one-step) and excellent repeatability, underscoring that both methods are highly capable, with the two-step protocol offering a marginal sensitivity benefit in this specific application [39].

Experimental Protocols

One-Step RT-qPCR Protocol

The one-step protocol is designed for speed and simplicity, consolidating the entire process into a single reaction tube.

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. Combine the following components in a qPCR tube or plate on ice [37]:

- RNA template: 1 pg–1 μg of total RNA (volume should be <20% of final reaction volume).

- One-Step Master Mix: Contains reverse transcriptase, thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and reaction buffers.

- Gene-specific primers: Both forward and reverse primers for the qPCR amplification.

- Probe or dye: A sequence-specific fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) or a DNA-binding dye (e.g., SYBR Green).

- Nuclease-free water to the final volume.

- Step 2: Thermal Cycling. Place the plate into a real-time PCR instrument and run the following combined program:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 10–30 minutes [37].

- Initial Denaturation/Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 2–10 minutes.

- Amplification (40–50 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 10–15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 55–65°C for 30–60 seconds (with fluorescence measurement).

- Step 3: Data Analysis. Determine Cycle threshold (Ct) values and quantify target abundance using absolute standard curves or relative quantification methods [37].

Two-Step RT-qPCR Protocol

The two-step protocol offers superior flexibility by physically separating the cDNA synthesis and amplification steps.

- Step 1: Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis).

- Primer Annealing: In a nuclease-free tube, mix 1 pg–2 μg of total RNA with RT primers (random hexamers, oligo(dT), or gene-specific primers) and nuclease-free water. Incubate at 65–70°C for 5–10 minutes to denature secondary structures, then immediately place on ice [37].

- cDNA Synthesis: Add a master mix containing reverse transcriptase, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor, and reaction buffer. Mix gently and incubate at 37–50°C for 30–60 minutes [37].

- Reaction Termination: Inactivate the reverse transcriptase by heating to 70–85°C for 5–15 minutes [37]. The resulting cDNA can be stored for future use.

- Step 2: Quantitative PCR.

- Reaction Setup: In a qPCR tube, combine:

- cDNA template: 1–5 μL of the diluted or undiluted RT reaction.

- qPCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and optimized buffers.

- Gene-specific primers and Probe or dye.

- Nuclease-free water to the final volume.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the plate into the real-time PCR instrument and run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–10 minutes.

- Amplification (40–50 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 10–15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 55–65°C for 30–60 seconds (with fluorescence measurement) [38].

- A melt curve analysis is recommended following amplification if using a DNA-binding dye like SYBR Green to verify amplification product specificity [38].

- Reaction Setup: In a qPCR tube, combine:

Integration with RNA-Seq Workflows

RT-qPCR is the gold standard for validating gene expression patterns observed in RNA-Seq experiments [1]. The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR in this context is strategic. When RNA-Seq identifies a long list of candidate genes, two-step RT-qPCR is strongly recommended. The resulting cDNA archive allows for the efficient screening of tens to hundreds of targets from a single, often limited, RNA sample, which is a common scenario in patient-derived samples or precious tissue specimens [34] [36]. Conversely, once a specific, smaller gene signature has been firmly established and requires routine testing across large sample sets (e.g., in clinical trial biomarker assays or high-throughput drug screening), transitioning to a one-step RT-qPCR platform can dramatically increase throughput, reduce costs, and minimize procedural variability [34] [35].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for integrating RNA-Seq with RT-qPCR validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Successful RT-qPCR relies on a set of core reagents. The table below details these essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for RT-qPCR experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template [37]. | Engineered enzymes (e.g., LunaScript) tolerate higher temperatures, improving specificity [34]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that amplifies the cDNA template during qPCR cycles [37]. | Must be heat-stable. Often pre-mixed with optimized buffers in master mixes [38]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for DNA synthesis [37]. | Quality and concentration are critical for efficient cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification [37]. |

| RT Primers | Initiates cDNA synthesis. Types: Random Hexamers (for all RNA), Oligo(dT) (for mRNA), Gene-Specific (for specific targets) [37]. | Choice dictates sequence representation in the cDNA pool. Two-step protocols allow any type; one-step requires gene-specific [34] [36]. |

| qPCR Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides that define the target region to be amplified during qPCR [37]. | Must be designed for high specificity and efficiency (~18-25 nt, 40-60% GC, spanning exon-exon junctions) [37]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter | Allows real-time detection of amplified products. Includes DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) and sequence-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan) [38]. | Dyes are cost-effective but less specific. Probes (e.g., TaqMan) offer higher specificity and enable multiplexing [39] [38]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects the integrity of the RNA template from degradation by ribonucleases during the RT reaction [37]. | Essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible results, especially when working with low-abundance targets. |

| MgCl₂ | Provides magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), an essential cofactor for the activity of both reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase [37]. | Concentration is often optimized in the commercial master mix. |

There is no universally superior choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR; the optimal path is dictated by the specific experimental goals and constraints. One-step RT-qPCR is the tool of choice for high-throughput, targeted quantification, where speed, simplicity, and a minimized contamination risk are paramount. Two-step RT-qPCR is the unequivocal strategy for flexible, multi-target analysis, especially when working with valuable samples and when the goal is to build a reusable cDNA resource for the validation of RNA-Seq findings. By aligning the strengths of each method with the requirements of the experimental workflow—from initial RNA-Seq discovery to final, robust validation—researchers can ensure the generation of precise, reproducible, and biologically meaningful gene expression data.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as the capstone technology for genome-wide transcriptome analysis, enabling the unbiased detection of both known and novel features like transcript isoforms, gene fusions, and single nucleotide variants in a single assay [15] [40]. This powerful technique provides a comprehensive, quantitative snapshot of the dynamic cellular transcriptome with a wide dynamic range and high sensitivity [15] [41].

Despite its comprehensive nature, the transition from RNA-Seq's discovery-based findings to focused, quantitative validation is a critical step in robust experimental workflow research. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating gene expression results due to its simplicity, maturity, affordability, and high sensitivity [42] [10]. This application note outlines a systematic framework for selecting optimal candidate genes from RNA-Seq datasets for subsequent qPCR validation, ensuring efficient resource allocation and confirmation of key biological findings.

RNA-Seq Data Analysis: From Raw Reads to Differential Expression

The journey from raw sequencing data to a list of candidate genes involves multiple computational steps, each requiring specific tools and careful quality control. A standard RNA-Seq analysis workflow progresses through preprocessing, alignment, quantification, and differential expression analysis [43].

Preprocessing and Quality Control

The initial phase begins with assessing raw sequence data stored in FASTQ format. Quality control (QC) is crucial and employs tools like FastQC or multiQC to identify technical artifacts including adapter contamination, unusual base composition, or duplicated reads [43]. Following QC, read trimming with tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt cleans the data by removing low-quality bases and adapter sequences [43].

Subsequently, cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using aligners like STAR or HISAT2, or alternatively, pseudo-aligned using faster tools like Kallisto or Salmon [43]. Post-alignment QC is then performed with tools like SAMtools or Qualimap to remove poorly aligned or multimapping reads that could artificially inflate expression counts [43]. The final preprocessing step, read quantification, uses programs such as featureCounts to generate a raw count matrix summarizing the number of reads mapped to each gene in every sample [43].

Normalization and Differential Expression Analysis

The raw count matrix cannot be directly compared between samples due to differences in sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample) and library composition (expression profile of each sample) [43]. Normalization corrects for these technical biases. Table 1 compares common normalization methods.

Table 1: Common RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling; heavily affected by highly expressed genes [43] |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No | Enables within-sample comparison; not for cross-sample DE [43] |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | Preferred over RPKM/FPKM for cross-sample comparison [43] |

| median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition bias; affected by large expression shifts [43] |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition bias; affected by over-trimming [43] |

For differential expression (DE) analysis, normalization methods like the median-of-ratios (used in DESeq2) and TMM (used in edgeR) are recommended as they account for library composition biases [43]. These tools apply statistical models to test for significant expression differences between experimental conditions, generating a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with associated p-values and fold-changes.

A Strategic Workflow for Selecting qPCR Candidate Genes

The process of selecting candidate genes from RNA-Seq results for qPCR validation should be guided by both statistical significance and biological relevance. The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic selection pathway.

Figure 1: A systematic workflow for selecting candidate genes for qPCR validation from RNA-Seq results.

Application of Statistical and Abundance Filters

The first step involves applying stringent statistical thresholds to the DEG list. Genes should meet both a significance criterion (e.g., adjusted p-value < 0.05 or FDR < 0.1) and a minimum fold-change threshold (e.g., ≥ 2-fold up or down) [43]. This prioritizes genes with large and statistically robust expression changes.

Next, candidate genes should be filtered by expression abundance using metrics like CPM or TPM. Very lowly expressed genes, even with high fold-changes, are challenging to validate accurately by qPCR. Setting a minimum abundance threshold (e.g., CPM ≥ 5-10 in a sufficient number of samples) ensures selected targets are reliably detectable [43].

Prioritization Based on Biological Relevance

After statistical filtering, the final and most crucial step is to prioritize genes based on their biological relevance to the research question. This involves several key considerations:

- Hypothesis-Driven Candidates: Genes directly related to the core biological hypothesis being tested.

- Pathway Enrichment: Key players in significantly enriched biological pathways or gene ontology terms.

- Novel Findings: Genes representing unexpected or novel discoveries that are central to the study's conclusions.

- Biomarker Potential: For clinical or translational studies, genes with potential as diagnostic, prognostic, or therapeutic biomarkers.

- Druggable Targets: In drug development, genes encoding proteins with known or predicted druggability.

This strategic triage ensures that qPCR validation efforts and resources are invested in the most biologically meaningful targets.

Experimental Design and qPCR Validation Protocol

The Critical Role of Experimental Design

A successful validation hinges on proper experimental design. Biological replication is non-negotiable for both RNA-Seq and qPCR experiments. While RNA-Seq with a low number of replicates might be used for discovery, validation requires sufficient power. Three replicates per condition is often considered the minimum, though more may be needed for heterogeneous samples [43]. Most critically, qPCR validation should be performed on an independent set of biological samples—not the same RNA used for sequencing. This practice validates not just the technical measurement, but the underlying biology itself [42].

Detailed qPCR Validation Protocol

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality total RNA from validation samples using a commercial kit. RNA integrity and purity are critical. Assess quality using an instrument that provides an RNA Integrity Number (RIN); a RIN > 8.0 is generally recommended for reliable results.

- Reverse Transcription: Convert equal amounts of total RNA (e.g., 1 µg) into cDNA using a high-capacity reverse transcription kit. Use a mixture of oligo(dT) and random hexamers for priming to ensure comprehensive coverage of both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts.

Selection and Validation of Reference Genes