From In Silico to In Vitro: A Strategic Framework for Validating Bioinformatics Drug Target Predictions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on bridging the critical gap between computational drug-target interaction (DTI) predictions and experimental validation.

From In Silico to In Vitro: A Strategic Framework for Validating Bioinformatics Drug Target Predictions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on bridging the critical gap between computational drug-target interaction (DTI) predictions and experimental validation. It explores the foundational principles of modern AI-driven DTI prediction models, including graph neural networks and evidential deep learning. The content details methodological workflows for prioritizing computational hits for in vitro testing, troubleshooting common pitfalls in assay design, and establishing robust validation frameworks to assess prediction accuracy and translational potential. By synthesizing strategies from foundational exploration to comparative analysis, this guide aims to enhance the efficiency and success rate of transitioning in silico discoveries into biologically confirmed leads.

The Computational Frontier: Understanding AI-Driven Drug Target Predictions

The drug discovery process is characterized by exceptionally high costs, extended timelines, and daunting attrition rates. Traditional development from initial research to market requires approximately $2.3 billion and spans 10–15 years, with over 90% of drug candidates failing to reach the market [1]. This inefficiency stems largely from inadequate target validation and unanticipated off-target effects early in the discovery pipeline. In this challenging landscape, in silico prediction technologies have evolved from complementary tools to indispensable assets, fundamentally reshaping how researchers identify and validate therapeutic targets.

This guide objectively compares the performance of leading computational drug-target prediction methods and details the experimental frameworks essential for validating their predictions. By integrating computational precision with rigorous experimental validation, research organizations can significantly de-risk the discovery pipeline and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

TheIn SilicoArsenal: Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Computational approaches for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction have diversified significantly, ranging from traditional structure-based methods to modern machine learning platforms. The table below compares the primary methodologies and their characteristics.

Table 1: Key In Silico Drug-Target Prediction Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools/Platforms | Core Approach | Data Requirements | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Centric | MolTarPred, SuperPred, PPB2 | 2D/3D chemical similarity searching, QSAR, pharmacophore modeling | Known bioactive compounds, chemical structures | Hit identification, lead optimization, drug repurposing |

| Target-Centric | RF-QSAR, TargetNet, CMTNN | Machine learning models (Random Forest, Naïve Bayes) per target | Bioactivity data (e.g., ChEMBL, BindingDB) | Target fishing, polypharmacology prediction |

| Structure-Based | Molecular Docking (AutoDock Vina), De Novo Design | Protein-ligand docking simulations, binding affinity prediction | 3D protein structures (PDB, AlphaFold) | Virtual screening, binding mechanism analysis |

| Integrated/Machine Learning | DeepTarget, MolTarPred, DTINet | Multimodal data integration, deep learning, network algorithms | Heterogeneous data (chemical, genomic, phenotypic) | Novel target discovery, mechanism of action prediction |

Performance Benchmarking of Prediction Tools

A 2025 systematic comparison of seven target prediction methods using an FDA-approved drug benchmark revealed significant performance variations. The study evaluated stand-alone codes and web servers using a shared dataset to ensure consistent comparison [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Target Prediction Methods (2025 Benchmark)

| Method | Type | Algorithm/Approach | Key Database Source | Reported Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolTarPred | Ligand-centric | 2D similarity (MACCS/Morgan fingerprints) | ChEMBL 20 | Most effective method in benchmark; Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores outperformed MACCS |

| CMTNN | Target-centric | ONNX runtime | ChEMBL 34 | Stand-alone code with modern architecture |

| RF-QSAR | Target-centric | Random Forest | ChEMBL 20 & 21 | Web server implementation |

| TargetNet | Target-centric | Naïve Bayes | BindingDB | Uses multiple fingerprint types |

| PPB2 | Ligand-centric | Nearest neighbor/Naïve Bayes/DNN | ChEMBL 22 | Considers top 2000 similar ligands |

| SuperPred | Ligand-centric | 2D/fragment/3D similarity | ChEMBL & BindingDB | Established method with comprehensive similarity approaches |

| ChEMBL | Target-centric | Random Forest | ChEMBL 24 | Official ChEMBL platform implementation |

The study found that MolTarPred emerged as the most effective method overall, with optimization notes indicating that Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto similarity metrics outperformed other fingerprint and scoring combinations [2]. Performance optimization strategies such as high-confidence filtering (using ChEMBL confidence score ≥7) improved prediction reliability, though with some reduction in recall, making such filtering less ideal for drug repurposing applications where broader target space exploration is valuable.

Specialized Tools for Oncology Applications

In cancer drug discovery, DeepTarget has demonstrated superior performance in predicting both primary and secondary targets of small-molecule agents. Benchmark testing revealed that DeepTarget outperformed existing tools like RoseTTAFold All-Atom and Chai-1 in seven out of eight drug-target test pairs for predicting targets and their mutation specificity [3]. This tool integrates large-scale drug and genetic knockdown viability screens with omics data, uniquely capturing cellular context and pathway-level effects that often play crucial roles in oncology therapeutics beyond direct binding interactions.

From Prediction to Validation: Essential Experimental Frameworks

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm biological relevance. The following section outlines established experimental protocols for verifying in silico drug target predictions.

Experimental Validation Workflow

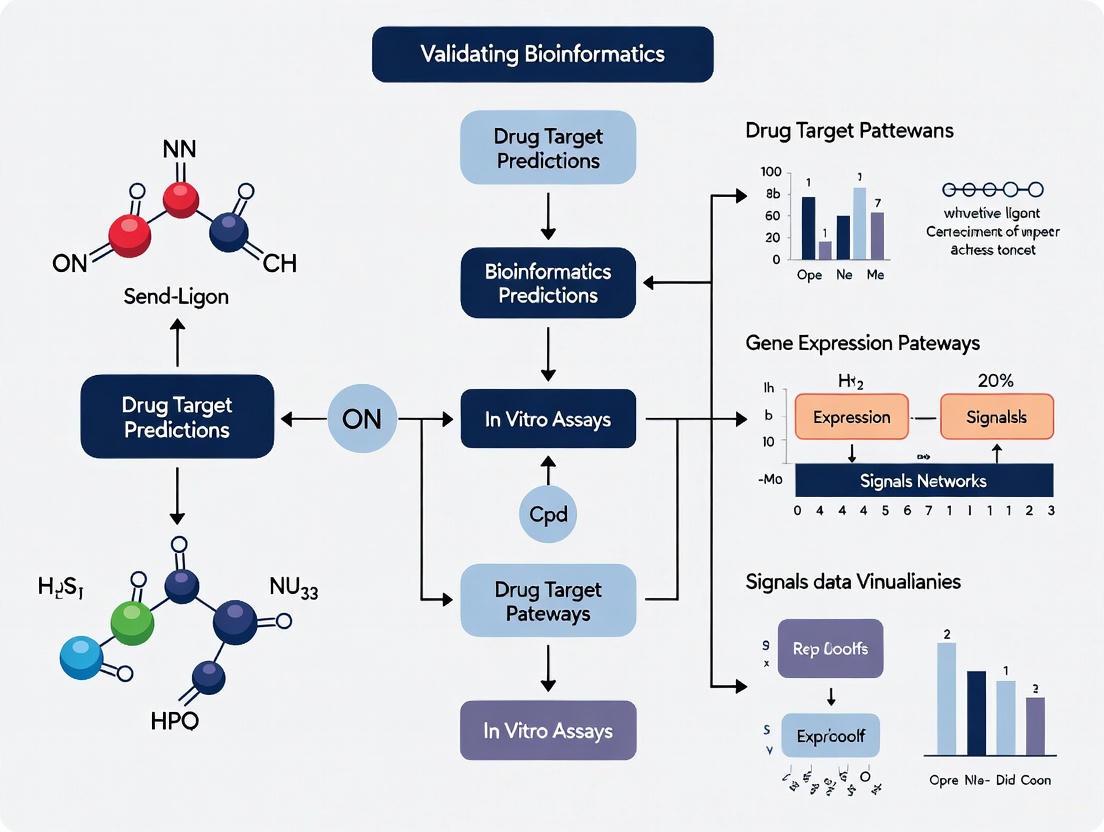

The transition from in silico prediction to biologically validated target involves a multi-stage process, illustrated below:

Key Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Cellular Target Engagement Validation (CETSA)

The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a leading approach for validating direct target engagement in intact cells and tissues, addressing the critical gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [4].

Protocol Summary:

- Cell Preparation: Treat intact cells with the drug compound or vehicle control across a range of concentrations and time points.

- Heat Challenge: Subject cell aliquots to different temperatures (typically 45-65°C) to denature proteins not stabilized by drug binding.

- Protein Solubility Analysis: Separate soluble (native) proteins from insoluble (denatured) aggregates and quantify target protein levels in the soluble fraction.

- Data Interpretation: Drug-induced thermal stabilization is evidenced by increased melting temperature (Tm) and greater remaining soluble target protein at higher temperatures.

Application Example: Recent work by Mazur et al. (2024) applied CETSA in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantitatively demonstrate dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization of DPP9 in rat tissue, confirming target engagement ex vivo and in vivo [4].

Functional Validation in Disease Models

After establishing target engagement, functional validation in disease-relevant models is essential.

Cancer Target Validation Protocol (e.g., CHEK1 in Soft Tissue Sarcoma):

- Gene Expression Analysis: Analyze transcriptomic data from patient samples (e.g., TCGA-SARC cohort) to correlate target expression with clinical outcomes.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC staining on patient tissue microarrays to validate protein-level expression and spatial distribution within tumor microenvironments [5].

- Genetic Perturbation: Implement CRISPR-Cas9 mediated knockout or RNA interference to assess the functional consequence of target modulation on cancer cell viability, proliferation, and invasion.

- Therapeutic Assessment: Evaluate the efficacy of target-specific inhibitors in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models or cell line-derived xenografts.

Application Example: In situ analysis of independent soft tissue sarcoma validation cohorts revealed significant correlation between CHEK1 expression and tumor-infiltrating immune cells, establishing CHEK1 as a promising therapeutic target in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation of computational predictions requires specific research reagents and platforms. The table below details key solutions for experimental confirmation of drug-target interactions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features/Benefits | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CETSA Platform | Target engagement validation in physiologically relevant cellular contexts | Measures thermal stabilization of drug-target complexes in intact cells; provides system-level validation | Confirmation of direct binding; mechanism of action studies; biomarker development [4] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene knockout and editing for functional validation | Precise genome manipulation; enables assessment of target essentiality | Functional genomics; target prioritization; synthetic lethality screening [6] |

| CIBERSORTx | Digital cytometry for tumor immune microenvironment deconvolution | Estimates immune cell fractions from bulk transcriptome data; no single-cell RNA-seq required | Tumor immunophenotyping; biomarker discovery; immunotherapy target identification [5] |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking and virtual screening | Open-source; hybrid scoring function combining empirical and knowledge-based terms | Binding pose prediction; virtual screening; binding affinity estimation [7] |

| AlphaFold2 Models | Protein structure prediction for targets lacking experimental structures | High-accuracy 3D structure prediction from amino acid sequences | Expanding structural coverage for structure-based drug design [1] |

Integrated Workflow: A Case Study in HCV Drug Discovery

A comprehensive structural bioinformatics study on Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) demonstrates the powerful synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation [7]. The research employed an integrated workflow combining:

Computational Phase:

- Homology Modeling: Generated high-quality 3D structures for key HCV proteins (NS3 protease, NS5B polymerase) using MODELLER and I-TASSER

- Virtual Screening: Docked millions of compounds from the ZINC database against identified druggable sites using AutoDock Vina

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Ranked compounds based on calculated binding energies and interaction patterns

Experimental Validation Phase:

- Compound Testing: Evaluated top-ranked compounds in enzymatic assays for HCV protein inhibition

- Structural Confirmation: Determined crystal structures of key protein-ligand complexes to validate predicted binding modes

- Cellular Efficacy: Assessed antiviral activity in HCV replicon systems and primary hepatocyte models

This integrated approach identified promising drug targets including NS3 protease, NS5B polymerase, core protein, and NS5A, with detailed characterization of their binding pockets and interaction patterns [7]. The study demonstrates how computational approaches can prioritize the most promising targets and compounds for experimental investment, dramatically increasing the efficiency of the discovery pipeline.

The drug discovery bottleneck, characterized by prohibitive costs and unacceptable attrition rates, demands a fundamental transformation in approach. In silico prediction methods have evolved from supportive tools to indispensable components of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to navigate the expansive landscape of potential targets and therapeutic compounds with unprecedented efficiency. As benchmark comparisons demonstrate, tools like MolTarPred for general target prediction and DeepTarget for oncology applications provide robust platforms for generating high-confidence hypotheses.

However, computational predictions alone cannot overcome the validation bottleneck. The full power of in silico approaches is realized only through rigorous experimental validation using established frameworks including CETSA for target engagement, functional assays in disease-relevant models, and translational studies that bridge cellular findings to clinical relevance. By integrating computational precision with experimental rigor, the drug discovery community can systematically address the historical challenges of high attrition and accelerate the development of transformative therapies for patients in need.

The accurate prediction of drug-target interactions (DTIs) is a critical bottleneck in the drug discovery pipeline. Traditional experimental methods for identifying DTIs are time-consuming, expensive, and low-throughput, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a new drug to market [8]. Computational approaches have emerged as powerful tools to prioritize drug-target pairs for experimental validation, with deep learning architectures now demonstrating particular promise by learning complex patterns from large-scale biological data.

Among deep learning approaches, three core architectures have shown significant potential: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, and Autoencoders. These architectures differ fundamentally in how they represent and process molecular and sequence data, leading to distinct strengths and limitations in DTI prediction tasks. GNNs excel at modeling the inherent graph structure of molecules, Transformers capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences, and Autoencoders learn compressed representations that reveal latent patterns in heterogeneous biological networks.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of these architectures within the context of validating bioinformatics predictions with in vitro assays. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these architectural differences is crucial for selecting appropriate models, interpreting their predictions, and successfully translating computational findings into experimental validation.

Core Architectures and Their Methodologies

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs process data represented as graphs, making them naturally suited for molecular structures where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges. In DTI prediction, GNNs typically operate through message passing mechanisms where node features are updated by aggregating information from neighboring nodes [9] [10].

Key Methodological Components:

- Molecular Graph Representation: Drugs are represented as 2D molecular graphs derived from SMILES strings, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [10]. Each atom node is initialized with features including atom type, degree, number of implicit hydrogens, formal charge, and hybridization state.

- Graph Convolutional Layers: These layers update atom representations by combining a node's features with aggregated features from its neighbors. The Hetero-KGraphDTI framework employs a multi-layer message passing scheme that aggregates information from different edge types in heterogeneous graphs [8].

- Attention Mechanisms: Graph Attention Networks (GATs) assign importance weights to different edges during aggregation, enabling the model to focus on the most informative molecular substructures [8].

The GNN encoder in models like MGMA-DTI typically consists of a three-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) that progressively aggregates information from neighboring atomic nodes to capture the topological structure of drug molecules [9].

Transformers

Transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture global dependencies in sequential data, making them particularly effective for protein sequences where long-range interactions between amino acids are crucial for binding site formation [10].

Key Methodological Components:

- Self-Attention Mechanism: Computes attention weights for all pairs of elements in a sequence, allowing each position to attend to all other positions. This is particularly valuable for capturing non-local interactions in protein sequences that influence binding affinity.

- Positional Encodings: Since Transformers lack inherent sequential inductive bias, positional encodings are added to input embeddings to incorporate information about the relative or absolute position of tokens in the sequence.

- Multi-Head Attention: Employs multiple attention mechanisms in parallel to capture different types of relationships within the data.

In CAT-DTI, the Transformer architecture is combined with CNNs to encode both local features and global contextual information from protein sequences [10]. The model uses a convolution neural network combined with a Transformer to encode distance relationships between amino acids within protein sequences.

Autoencoders

Autoencoders learn compressed representations of input data through an encoder-decoder structure, making them valuable for integrating heterogeneous biological information and detecting latent patterns in DTI networks [11].

Key Methodological Components:

- Encoder Network: Maps input data to a lower-dimensional latent space representation through a series of transformative layers.

- Bottleneck Layer: Contains the compressed knowledge representation that ideally captures the most salient features of the input data.

- Decoder Network: Reconstructs the input data from the latent representation, ensuring the encoding retains critical information.

The DDGAE model exemplifies the modern autoencoder approach for DTIs, incorporating a Dynamic Weighting Residual Graph Convolutional Network (DWR-GCN) with residual connections to enable deeper networks without over-smoothing issues [11]. The framework employs a dual self-supervised joint training mechanism that integrates DWR-GCN and a graph convolutional autoencoder into a cohesive system.

Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the performance of various GNN, Transformer, and Autoencoder-based models on standard DTI prediction benchmarks, providing quantitative comparisons across multiple evaluation metrics.

Table 1: Performance comparison of GNN-based models on benchmark datasets

| Model | Architecture | Dataset | AUC | AUPR | Accuracy | Other Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hetero-KGraphDTI [8] | GNN with Knowledge Integration | Multiple Benchmarks | 0.98 (avg) | 0.89 (avg) | - | - |

| MGMA-DTI [9] | GCN with Multi-order Gated Convolution | BindingDB | - | - | - | AUROC: 0.988, AUPRC: 0.828, F1: 0.930 |

| EviDTI [12] | GNN with Evidential Deep Learning | DrugBank | - | - | 82.02% | Precision: 81.90%, MCC: 64.29%, F1: 82.09% |

| EviDTI [12] | GNN with Evidential Deep Learning | Davis | - | - | - | Competitive across metrics |

| EviDTI [12] | GNN with Evidential Deep Learning | KIBA | - | - | - | Competitive across metrics |

Table 2: Performance comparison of Transformer-based models

| Model | Architecture | Dataset | AUC | AUPR | Accuracy | Other Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT-DTI [10] | Cross-attention & Transformer | Multiple Benchmarks | - | - | - | Overall improvement vs. previous methods |

| MolTrans [8] | Transformer | KEGG | 0.98 | - | - | - |

Table 3: Performance comparison of Autoencoder-based models

| Model | Architecture | Dataset | AUC | AUPR | Accuracy | Other Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDGAE [11] | Graph Convolutional Autoencoder | DrugBank-based | 0.9600 | 0.6621 | - | - |

| optSAE + HSAPSO [13] | Stacked Autoencoder with Optimization | DrugBank & Swiss-Prot | - | - | 95.52% | Computational complexity: 0.010 s/sample |

Table 4: Cross-domain performance and generalization capabilities

| Model | Architecture | Cross-domain Performance | Uncertainty Quantification | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EviDTI [12] | GNN with EDL | Strong in cold-start scenarios | Yes | Moderate |

| CAT-DTI [10] | Transformer with CDAN | Enhanced via domain adaptation | No | High (via attention) |

| DDGAE [11] | Autoencoder with DWR-GCN | - | No | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Training and Evaluation Protocols

Dataset Preparation and Splitting: Standard benchmarks for DTI prediction include BindingDB, BioSNAP, Human, DrugBank, Davis, and KIBA datasets. In most studies, datasets are randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets with typical ratios of 8:1:1 [12]. For cross-domain evaluation, special protocols are employed where models are trained on a source domain and tested on a different target domain to assess generalization capability [10].

Evaluation Metrics: The most common evaluation metrics include:

- AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve): Measures the model's ability to distinguish between interacting and non-interacting pairs across all classification thresholds.

- AUPR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve): Particularly important for imbalanced datasets where non-interactions vastly outnumber interactions.

- Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient): Provide complementary perspectives on model performance.

Negative Sampling Strategies: Given the positive-unlabeled nature of DTI data, sophisticated negative sampling frameworks are crucial. The Hetero-KGraphDTI framework implements three complementary strategies to generate reliable negative samples: random sampling, similarity-based filtering, and biological knowledge-based exclusion [8].

Experimental Workflows

The experimental workflow for developing and validating DTI prediction models typically follows these key stages:

Diagram 1: DTI Model Development and Validation Workflow

Architecture Integration Patterns

Modern DTI prediction models increasingly combine multiple architectural paradigms to leverage their complementary strengths:

Diagram 2: Hybrid Architecture Integration Pattern

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Key research reagents and computational resources for DTI prediction

| Resource | Type | Function in DTI Prediction | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank Database [11] | Chemical Database | Source of drug structures, target information, and known interactions | Feature extraction, ground truth labels, negative sampling |

| BindingDB [9] | Bioactivity Database | Provides binding affinity data for drug-target pairs | Model training and evaluation |

| ProtTrans [12] | Pre-trained Protein Language Model | Generates protein sequence representations using Transformer architectures | Feature extraction from target protein sequences |

| MG-BERT [12] | Pre-trained Molecular Model | Gener molecular representations from graph structures | Feature extraction from drug compounds |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [8] | Knowledge Base | Provides structured biological knowledge for regularization | Enhancing biological plausibility of predictions |

| RDKit [9] | Cheminformatics Library | Processes SMILES strings and generates molecular graphs | Drug feature extraction and representation |

The comparative analysis of GNNs, Transformers, and Autoencoders for DTI prediction reveals a complex landscape where each architecture offers distinct advantages. GNNs demonstrate exceptional performance in modeling molecular structures, with frameworks like Hetero-KGraphDTI achieving AUC scores up to 0.98. Transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies in protein sequences, while Autoencoders like DDGAE show strong performance in learning compressed representations of heterogeneous biological networks.

For researchers validating predictions with in vitro assays, architectural selection should align with specific research goals and data characteristics. GNNs are preferable when molecular structure is paramount, Transformers when protein sequence context is critical, and Autoencoders when integrating diverse data sources. Emerging trends favor hybrid approaches that combine architectural strengths, such as CAT-DTI's integration of GNNs and Transformers with domain adaptation capabilities.

Uncertainty quantification, as implemented in EviDTI, represents a particularly valuable direction for experimental validation, as it helps prioritize predictions with higher confidence for laboratory testing. As these architectures continue to evolve, their ability to generate biologically interpretable predictions will be crucial for bridging the gap between computational forecasting and experimental confirmation in the drug discovery pipeline.

The process of drug discovery increasingly relies on computational models to predict interactions between potential drug compounds and their biological targets. Accurately interpreting the outputs of these models—from initial binding affinity scores to the quantification of predictive uncertainty—is critical for prioritizing candidates for costly and time-consuming in vitro and in vivo validation. As these computational tools grow more complex, moving from traditional docking scores to sophisticated deep learning and large language model (LLM) based predictions, the need for robust interpretation frameworks has never been greater. This guide objectively compares the performance and capabilities of various computational approaches used in bioinformatics for drug target prediction, with a specific focus on how their outputs should be interpreted and validated within an experimental research context. The ultimate goal is to provide researchers with a practical framework for translating computational predictions into scientifically sound hypotheses for experimental testing, thereby bridging the gap between in silico discovery and in vitro confirmation.

Comparative Performance of Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction Models

Different computational approaches offer varying strengths in predicting drug-target interactions. The table below summarizes the reported performance of several prominent methods, providing a baseline for objective comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DTI Prediction Models

| Model/Method | Core Approach | Reported AUC | Reported AUPR | Key Strengths | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hetero-KGraphDTI | Graph Neural Network with Knowledge Integration | 0.98 [14] | 0.89 [14] | Integrates multiple data types (chemical structures, protein sequences, interaction networks) | High (Attention weights identify salient molecular substructures and protein motifs) [14] |

| Multi-modal GCN (Ren et al.) | Graph Convolutional Network | 0.96 [14] | Information Not Provided | Integrates chemical structures, protein sequences, and PPI networks | Information Not Provided |

| Graph-based Model (Feng et al.) | Heterogeneous Network Learning | 0.98 (KEGG dataset) [14] | Information Not Provided | Learns from multiple heterogeneous networks (drug-drug, target-target, drug-target) | Information Not Provided |

| Traditional Fine-Tuned BERT/BART | Fine-tuned Encoder or Encoder-Decoder Models | ~0.65 (Macro-average across 12 BioNLP tasks) [15] | Information Not Provided | Superior performance in most BioNLP tasks (e.g., information extraction) compared to zero/few-shot LLMs [15] | Information Not Provided |

| GPT-4 (Zero/Few-Shot) | Large Language Model | ~0.51 (Macro-average across 12 BioNLP tasks) [15] | Information Not Provided | Excels in reasoning-related tasks (e.g., medical question answering) [15] | Lower (Prone to hallucinations and missing information) [15] |

From Raw Scores to Biological Meaning: Interpreting Key Outputs

Binding Affinity and Interaction Scores

Computational models generate scores that estimate the strength and likelihood of a drug-target interaction. These scores must be interpreted with a clear understanding of their methodological origins.

- Molecular Docking Scores: Tools like AutoDock Vina predict binding affinity using a hybrid scoring function that calculates the binding free energy (ΔGbinding). This function incorporates terms for attractive/repulsive forces (ΔGgauss), steric clashes (ΔGrepulsion), hydrophobic interactions (ΔGhydrophobic), hydrogen bonding (ΔGhydrogenbonding), and entropic loss due to conformational restriction (ΔGtorsional) [7]. A more negative ΔG_binding generally indicates a more stable and favorable binding interaction.

- Machine Learning Classification Scores: Models like Hetero-KGraphDTI output an interaction probability or a binary classification (interact/does not interact). The high Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.98 and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) of 0.89 reported for this model indicate a strong ability to distinguish true interactions from non-interactions across multiple benchmark datasets [14]. When interpreting these scores, researchers should consider the precision-recall trade-off, especially when dealing with imbalanced datasets where non-interacting pairs are far more common.

The Critical Role of Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)

A model's predictive score is an incomplete picture without an estimate of its associated uncertainty. Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) is essential for assessing the reliability of predictions and is a fundamental requirement for evidence-based reasoning [16].

- Model Uncertainty (Epistemic Uncertainty): This arises from the model's architecture, training data, and optimization process. For generative AI models, this can be quantified by analyzing the variability of evaluation metrics, like precision-recall curves, across multiple training runs with different random initializations [17]. The formal definition of this "model-induced evaluation uncertainty" is the variance of the evaluation metric due to differences in model initialization [17].

- Performance in UQ Tasks: The ability of AI models to perform UQ tasks varies significantly with complexity. A 2025 study found that while reasoning models are generally capable of UQ (scores ≳70%) in simple tasks like judging which of two sample sets is larger, their performance drops to near random guessing (~33%) for complex inequalities requiring multiple intermediate calculations if not guided by specific UQ methods in the prompt [16].

- Data and Aleatoric Uncertainty: This refers to the inherent noise in the experimental data used to train the models. For DTI prediction, this includes variability in binding assay results, inconsistencies in publicly available databases, and incomplete biological context [18].

Experimental Protocols for Computational Validation

Protocol 1: Knowledge-Informed Graph Neural Network

This protocol is adapted from the Hetero-KGraphDTI framework, which integrates graph representation learning with biological knowledge [14].

- Graph Construction: Create a heterogeneous graph that integrates multiple data types. Nodes represent drugs and targets. Edges represent various relationships, such as drug-drug similarity (based on molecular structure), target-target similarity (based on protein sequence or protein-protein interactions), and known drug-target interactions.

- Feature Representation: Represent drugs via their molecular structures (e.g., as graphs or fingerprints) and targets via their protein sequences or structural features.

- Model Training: Train a Graph Neural Network (GNN), such as a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Graph Attention Network (GAT), on the constructed graph. The model learns low-dimensional embeddings for drugs and targets by aggregating information from their local neighborhoods in the graph.

- Knowledge-Based Regularization: Integrate prior biological knowledge from sources like Gene Ontology (GO) and DrugBank during training. This is done using a regularization strategy that encourages the learned drug and target embeddings to be consistent with known ontological and pharmacological relationships [14].

- Prediction and Interpretation: Predict novel DTIs based on the learned embeddings. Use the model's integrated attention mechanisms to identify which molecular substructures and protein motifs are driving the predicted interaction, providing a degree of interpretability [14].

Protocol 2: Structural Bioinformatics Workflow for Novel Target Identification

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for identifying and evaluating novel drug targets within a viral proteome, as demonstrated in a Hepatitis C virus (HCV) study [7].

- Data Retrieval and Preprocessing: Obtain protein sequences for the target organism (e.g., from UniProt). Preprocess sequences to remove redundancy and low-quality regions using tools like CD-HIT with a sequence identity threshold of 90% [7].

- Homology Modeling: For proteins without experimentally determined structures, generate 3D models using homology modeling software like MODELLER or I-TASSER. Select high-resolution crystal structures from the PDB as templates, prioritizing those with a sequence identity of at least 30% and coverage over 80% [7].

- Molecular Docking: Perform molecular docking simulations using software like AutoDock Vina to predict binding sites and interactions. Prepare the protein structures by optimizing and refining them with energy minimization techniques (e.g., using the AMBER force field). Define the docking search space (grid box) around predicted druggable sites, typically with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 20 Å [7].

- Virtual Screening: Screen large compound libraries (e.g., from the ZINC database) against the target protein. Rank the resulting compounds based on their predicted binding energy.

- Post-Docking Analysis: Visually inspect the top-ranked compounds' binding modes and interactions with the target protein using molecular visualization software like PyMOL. Evaluate the drug-likeness of compounds using established filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [7].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Validation: To assess the stability of the predicted ligand-protein complexes, run MD simulations using a package like GROMACS with the AMBER force field. Solvate the complex in a water box and run simulations for a sufficient time scale to capture dynamic behavior and confirm complex stability [7].

Uncertainty Quantification Frameworks

UQ for Large Language Models (LLMs) in Scientific Workflows

As LLMs are integrated into complex scientific workflows, their ability to perform fundamental UQ tasks becomes critical. A benchmark suite known as "Tether" has been developed to evaluate this capability, focusing on a fundamental UQ problem: estimating whether one quantity is probably larger than another under uncertainty [16]. The benchmark includes two key tasks:

- Simple Inequality Test: The model must judge, with 95% confidence, whether one set of samples is "larger," "smaller," or if the result is "uncertain" compared to another set. LLMs have shown reasonable capability here, with scores around 70% [16].

- Complex Inequality Test: This task requires the model to assess interventional probabilities involving multiple intermediate calculations. Without explicit UQ methods provided in the prompt, LLM performance drops significantly to around 33% (random guessing) [16].

This highlights that while LLMs have potential for UQ, their application in complex biomedical reasoning requires carefully designed prompts and frameworks that explicitly guide uncertainty estimation.

UQ for Generative Models in Distribution Learning

For generative models used in tasks like de novo molecular design, UQ focuses on the confidence in the model's approximation of the target data distribution. A key approach involves analyzing model uncertainty [17].

- Ensemble-based Precision-Recall Curves: This method involves training the model multiple times with different random initializations. The variability (uncertainty) in the precision-recall curves across these runs is then quantified, providing insight into the model's stability and sensitivity to training instabilities [17].

- Total Evaluation Uncertainty: This metric captures the overall variability in a generative model's performance. It incorporates uncertainty from the model's random initialization and the use of finite sets of real and generated samples to estimate the true data and model distributions [17].

Successfully validating computational predictions requires a suite of experimental and computational resources. The table below lists key tools and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Experimental Assay | Validates direct drug-target engagement in intact cells and native tissue environments [4]. | Provides quantitative, system-level validation of binding, closing the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy. |

| AutoDock Vina | Computational Tool | Performs molecular docking to predict ligand binding modes and affinities [7]. | Open-source; uses a hybrid scoring function to estimate binding free energy; widely used for virtual screening. |

| GROMACS | Computational Tool | Performs Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to assess the stability of predicted drug-target complexes [7]. | Highly efficient MD package; used to simulate the dynamic behavior of ligand-protein complexes in solvated environments. |

| DrugBank | Knowledge Base / Database | Provides comprehensive data on known drug-target interactions, mechanisms, and chemical information [18]. | Used for training computational models and validating novel predictions against known pharmacological data. |

| ChEMBL | Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, including bioactivity data [18]. | Provides bioactivity data for model training and benchmarking; essential for negative sampling during ML model development. |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | A freely available collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [7]. | Contains millions of compounds that can be docked against a target of interest to identify potential hits. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | A global archive for experimentally determined 3D structures of biological macromolecules [18]. | Source of high-resolution protein structures for homology modeling, molecular docking, and structure-based drug design. |

| TTD (Therapeutic Target Database) | Database | Provides information on known and explored therapeutic targets, diseases, and pathways [18]. | Useful for contextualizing novel target predictions within existing knowledge of druggable targets. |

The landscape of computational drug target prediction is diverse, encompassing methods from knowledge-informed GNNs to structural bioinformatics and emerging LLMs. The most accurate models, such as Hetero-KGraphDTI, demonstrate that integrating multiple data types and prior biological knowledge is key to achieving high predictive performance (AUC > 0.95) [14]. However, a high predictive score is not a guarantee of experimental success. Rigorous interpretation that includes Uncertainty Quantification is essential for establishing trustworthiness and prioritizing the most reliable predictions for experimental validation. Frameworks now exist to quantify this uncertainty for both LLMs [16] and generative models [17]. The successful translation of in silico predictions to in vitro validations relies on a complementary toolkit of computational and experimental resources, where methods like CETSA provide the crucial empirical link by confirming target engagement in physiologically relevant contexts [4]. By applying these comparative insights and rigorous validation protocols, researchers can more effectively navigate the complex journey from computational prediction to confirmed biological activity.

In the field of bioinformatics and drug discovery, the accuracy and reliability of computational models for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the underlying data sources. BindingDB, DrugBank, and UniProt have emerged as three cornerstone databases that researchers routinely leverage for training and validating machine learning and deep learning models. These resources provide complementary types of biological and chemical information that, when integrated, offer a comprehensive foundation for developing predictive algorithms. The validation of computational predictions through in vitro assays represents a critical step in the drug discovery pipeline, bridging the gap between in silico predictions and biological relevance. This guide objectively compares these three key databases, evaluates their performance in experimental contexts, and provides detailed methodologies for their effective utilization in research workflows aimed at translational drug discovery.

Database Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Key Bioinformatics Databases

| Database | Primary Focus | Data Content & Size | Key Features | Data Formats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [19] [20] | Binding affinity measurements | 2,114,159 binding data points between 8,202 protein targets and 928,022 small molecules [19] | Experimentally measured binding affinities (Ki, Kd, IC50); focuses on drug-target interactions | Web-accessible database; downloadable data |

| DrugBank [19] [21] | Comprehensive drug & target data | 14,443 drug molecules and 5,244 non-redundant protein sequences (Version 5.1.8) [19] | Integrates chemical, pharmacological, pharmaceutical data with comprehensive target information; drug-side effects; drug-drug interactions | Bioinformatics/cheminformatics resource; supports complex searches |

| UniProt [19] | Protein sequence & functional information | N/A (Most informative and comprehensive protein database) [19] | Manually annotated (Swiss-Prot) and automatically annotated (TrEMBL) sections; high-quality protein annotations from literature | Five sub-databases with specialized functions |

Table 2: Database Applications in Model Training and Experimental Validation

| Database | Role in DTI Model Training | Experimental Validation Support | Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB | Provides quantitative binding affinity data for regression models; defines negative DTIs (Ki/Kd/IC50/EC50/AC50/Potency >100 μM) [20] | Gold-standard for binding affinity validation; source of experimentally validated interactions [21] | Limited to proteins considered drug targets; binding measurements under specific conditions |

| DrugBank | Source of known drug-target pairs for binary classification; provides drug structures (SMILES) and target protein information [21] [19] | Provides clinically relevant drug-target pairs validated through experiments or extensive literature [21] | Focus on approved drugs and well-studied targets; limited for novel target discovery |

| UniProt | Source of protein sequences for feature extraction; enables similarity-based prediction across protein families [19] | Provides high-quality, manually annotated protein information with evidence-based assertions [19] | Functional annotations may be incomplete for less-studied proteins |

Experimental Protocols for Database Integration and Validation

Protocol 1: Construction of Gold-Standard DTI Datasets

Objective: Integrate data from BindingDB, DrugBank, and UniProt to create a high-confidence dataset for DTI model training and validation.

Materials:

- DrugBank database (drug and target information)

- BindingDB (binding affinity measurements)

- UniProt (protein sequence and functional annotation)

- HCDT 2.0 database (curated drug-gene, drug-RNA, drug-pathway interactions) [20]

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Download the latest versions of DrugBank, BindingDB, and UniProt databases through their official portals or APIs.

- Identifier Mapping: Standardize identifiers across databases using common accessions (e.g., UniProt IDs for proteins, PubChem IDs for compounds).

- Positive Instance Selection: Extract known drug-target pairs from DrugBank with clinical validation [21] and high-affinity interactions from BindingDB (Ki, Kd, IC50, EC50 ≤ 10 μM) [20].

- Negative Instance Selection: Define non-interacting pairs using BindingDB entries with binding affinity measurements >100 μM [20] or through biological sampling strategies [22].

- Feature Extraction:

- Dataset Splitting: Implement biologically-driven splitting strategies [22]:

- Warm start: Drugs and proteins shared between train and test sets

- Cold start: Unseen drugs or proteins in test set

Database Integration Workflow for DTI Model Training

Protocol 2: In Vitro Validation of Computational Predictions

Objective: Experimentally validate computationally predicted drug-target interactions using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and cell-based assays.

Materials:

- Purified target proteins

- Compound libraries from predicted interactions

- SPR instrumentation (e.g., Biacore)

- Cell lines expressing target proteins

- Assay reagents for functional readouts

Methodology:

- Candidate Selection: Select top-ranking DTI predictions from computational models for experimental testing.

- SPR Binding Assays:

- Immobilize purified target proteins on SPR sensor chips

- Inject compound solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., 0.1-100 μM)

- Measure association and dissociation rates to determine binding affinity (KD)

- Compare with known binders and negative controls

- Functional Cell-Based Assays:

- Treat relevant cell lines with predicted compounds (dose-response)

- Measure downstream pathway activation or inhibition

- Assess functional responses (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis, signaling)

- Validation Criteria: Confirm interactions with KD < 10 μM and statistically significant functional effects (p < 0.05) compared to controls.

Performance Assessment in Research Applications

Table 3: Database Performance in Published DTI Prediction Studies

| Study/Model | Databases Used | Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugMAN [21] | DrugBank, BindingDB, CTD, Others | AUROC: 0.912, AUPRC: 0.837 (warm start); Minimal performance decrease in cold-start scenarios | Demonstrated robust generalization ability for real-world applications |

| ColdstartCPI [23] | BindingDB, ChEMBL | Outperformed state-of-the-art methods in cold-start conditions; Effective with sparse data | Predictions validated via molecular docking, binding free energy calculations, literature search |

| HCDT 2.0 [20] | 9 drug-gene, 6 drug-RNA, 5 drug-pathway databases | 1,224,774 drug-gene pairs; 38,653 negative DTIs | High-confidence interactions curated through experimental validation criteria |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DTI Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDkit [19] | Python toolkit for cheminformatics | Compute molecular descriptors/fingerprints from compound structures |

| iFeature [19] | Python toolkit for protein sequence analysis | Generate feature descriptors from protein sequences for machine learning |

| ProtTrans [23] | Pre-trained protein language model | Extract protein features using transformer-based architectures |

| Mol2vec [23] | Unsupervised machine learning approach | Learn vector representations of molecular substructures |

| BIONIC [21] | Biological network integration framework | Learn node representations from multiple biological networks |

| SPR Instrumentation | Label-free binding affinity measurement | Validate direct molecular interactions in real-time |

Integration Strategies and Best Practices

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Effective utilization of BindingDB, DrugBank, and UniProt requires meticulous data preprocessing. For BindingDB, researchers should apply consistent thresholding for binding affinities (e.g., ≤10 μM for positive interactions and >100 μM for negative interactions) [20]. With DrugBank, careful attention should be paid to distinguishing between approved drugs, investigational drugs, and withdrawn compounds, as this affects the biological relevance of predictions. For UniProt, prioritization of manually curated Swiss-Prot entries over automatically annotated TrEMBL records ensures higher quality protein annotations [19].

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for DTI Validation

Addressing Cold-Start Challenges

A significant limitation in many DTI prediction approaches is poor performance on novel compounds or targets (cold-start problem) [22] [23]. To address this, researchers should employ specialized models like ColdstartCPI [23] or DrugMAN [21] that demonstrate robustness in these scenarios. Additionally, incorporating pre-trained features from large chemical libraries (via Mol2vec) [23] or protein language models (ProtTrans) [23] can enhance generalization to unseen entities. Biologically-driven dataset splitting strategies that separate drugs and proteins based on structural or functional similarity during training-test set creation are essential for realistic performance assessment [22].

BindingDB, DrugBank, and UniProt each provide unique and complementary data types that are essential for training robust DTI prediction models. BindingDB offers quantitative binding affinity measurements critical for regression tasks, DrugBank provides clinically validated drug-target pairs with rich contextual information, and UniProt delivers comprehensive protein sequences and functional annotations. The integration of these resources, coupled with appropriate experimental validation protocols, creates a powerful framework for accelerating drug discovery. As computational methods continue to evolve, particularly with advances in deep learning and multimodal approaches [24], these established databases will remain foundational resources for training and validating the next generation of DTI prediction models. Researchers should prioritize biologically-relevant benchmarking, careful attention to cold-start scenarios, and rigorous in vitro validation to ensure computational predictions translate to biologically meaningful results.

In the field of drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, the selection of appropriate performance metrics is not merely a technical formality but a critical determinant of a model's perceived utility and translational potential. For researchers and drug development professionals validating bioinformatics predictions with in vitro assays, understanding the nuances of these metrics is paramount for allocating precious experimental resources effectively. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and its corresponding Area Under the Curve (AUC) serve as fundamental tools for evaluating the diagnostic performance of index tests, which in this context are computational models designed to discriminate between interacting and non-interacting drug-target pairs [25] [26].

The ROC curve is a graphical plot that illustrates the trade-off between a model's True Positive Fraction (TPF, or sensitivity) and its False Positive Fraction (FPF, which is 1-specificity) across all possible classification thresholds [25]. The AUC value, which ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, summarizes this curve and represents the probability that the model will rank a randomly chosen positive instance (a true interaction) higher than a randomly chosen negative instance [26]. An AUC of 0.5 indicates performance equivalent to random chance, while an AUC of 1.0 signifies perfect discrimination [26]. In clinical and diagnostic contexts, AUC values above 0.9 are considered excellent, 0.8-0.9 considerable, 0.7-0.8 fair, and below 0.7 of limited clinical utility [26].

The Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) has emerged as a complementary metric, particularly valued in scenarios with class imbalance—a hallmark of DTI prediction datasets where known interactions are vastly outnumbered by unknown or non-interacting pairs [27]. While the ROC curve and its AUC remain indispensable for assessing a model's overall ranking ability, the precision-recall curve and its AUPRC focus on the model's performance in identifying positive instances, making it especially relevant when the positive class is the primary interest [27].

Comparative Analysis of AUC and AUPRC

Mathematical and Conceptual Foundations

The fundamental distinction between AUC and AUPRC lies in what they measure and how they weight different types of classification outcomes. AUC evaluates a model's ability to separate positive and negative classes across all thresholds, effectively measuring the probability that a random positive sample is ranked higher than a random negative sample [26]. This property makes it a robust metric for overall classification performance, as it is invariant to class imbalance and the specific classification threshold chosen [27].

AUPRC, in contrast, focuses specifically on the model's performance concerning the positive class by plotting precision (the proportion of true positives among all predicted positives) against recall (sensitivity, or the proportion of actual positives correctly identified) [27]. This focus makes AUPRC particularly sensitive to the model's ability to correctly identify positive instances without being overwhelmed by false positives—a critical consideration when validating predictions with expensive in vitro assays.

Recent mathematical analysis has revealed a probabilistic interrelationship between these metrics, demonstrating that while AUC weighs all false positives equally, AUPRC weighs false positives with the inverse of the model's likelihood of outputting a score greater than a given threshold [27]. This fundamental difference in weighting leads to distinct behavioral characteristics, especially in the context of class imbalance and model optimization priorities.

Behavioral Differences in Class-Imbalanced Scenarios

The widespread adage that "AUPRC is superior to AUC for model comparison under class imbalance" requires careful examination. While AUPRC values are indeed typically lower than AUC values in imbalanced datasets, this observation alone does not establish AUPRC's superiority for model comparison [27]. The critical consideration is not the absolute metric values but the relative rankings that different metrics confer upon models when making comparisons.

Research indicates that AUC and AUPRC implicitly prioritize different types of model improvements [27]. AUC optimization corresponds to a strategy where all classification errors are considered equally valuable to correct, regardless of where they occur in the score distribution. This approach is optimal for deployment scenarios where samples will be encountered across the entire score spectrum. AUPRC optimization, conversely, corresponds to prioritizing the correction of classification errors for samples assigned the highest scores first [27]. This strategy aligns with information retrieval settings where users primarily examine the top-k ranked predictions.

This distinction has profound implications for fairness and utility in DTI prediction. If the underlying dataset contains subpopulations with different prevalence rates (e.g., different protein families with varying numbers of known interactions), AUPRC will explicitly favor optimization for the higher-prevalence subpopulation, whereas AUC will optimize both subpopulations in an unbiased manner [27]. This bias can inadvertently introduce algorithmic disparities and should be carefully considered when evaluating models for broad deployment.

Practical Implications for DTI Prediction

For researchers validating DTI predictions with in vitro assays, the choice between AUC and AUPRC as a primary evaluation metric should align with the anticipated deployment context. If the goal is to generate a comprehensive ranking of all possible drug-target pairs for systematic exploration, AUC provides a more balanced assessment of overall ranking quality. However, if the research objective is to identify the most promising candidates for immediate experimental validation from the top-ranked predictions, AUPRC may better reflect the model's utility for this specific use case.

The most robust approach involves reporting both metrics alongside their confidence intervals, as each reveals different aspects of model performance. Furthermore, considering additional metrics such as precision at fixed recall levels or threshold-specific performance can provide a more complete picture of a model's operational characteristics.

Performance Benchmarking of State-of-the-Art DTI Prediction Models

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Recent DTI Prediction Models on Benchmark Datasets

| Model | Architecture | Dataset | AUC | AUPRC | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageMol [28] | Self-supervised Image Representation Learning | HIV, Tox21, BACE | 0.814 (HIV), 0.826 (Tox21), 0.939 (BACE) | N/R | Pretrained on 10M drug-like molecules; uses molecular images as input |

| EviDTI [12] | Evidential Deep Learning | DrugBank, Davis, KIBA | 0.820 (DrugBank Acc) | N/R | Integrates 2D/3D drug structures with target sequences; provides uncertainty estimates |

| DHGT-DTI [29] | Dual-view Heterogeneous Graph Network | Two benchmark datasets | N/R | N/R | Combines GraphSAGE (local features) and Graph Transformer (global features) |

| DDGAE [11] | Dynamic Weighting Residual GCN | Curated dataset (708 drugs, 1,512 targets) | 0.9600 | 0.6621 | Incorporates dynamic weighting graph convolution with residual connections |

| Hetero-KGraphDTI [14] | GNN with Knowledge-Based Regularization | Multiple benchmarks | 0.98 (avg) | 0.89 (avg) | Integrates biological knowledge graphs; uses attention mechanisms |

Table 2: Clinical Interpretation Guidelines for AUC Values [26]

| AUC Value Range | Interpretation | Suggested Clinical/Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|

| 0.9 ≤ AUC ≤ 1.0 | Excellent | High confidence for experimental validation |

| 0.8 ≤ AUC < 0.9 | Considerable | Promising for targeted experimental follow-up |

| 0.7 ≤ AUC < 0.8 | Fair | Limited utility; may require further model refinement |

| 0.6 ≤ AUC < 0.7 | Poor | Questionable utility for experimental guidance |

| 0.5 ≤ AUC < 0.6 | Fail | No better than random chance |

The performance landscape of contemporary DTI prediction models reveals consistent advancement in both AUC and AUPRC values. As shown in Table 1, recent models leveraging graph neural networks and knowledge integration have achieved exceptional performance, with Hetero-KGraphDTI reporting an average AUC of 0.98 and AUPRC of 0.89 across multiple benchmarks [14]. The DDGAE model demonstrates similarly strong performance with an AUC of 0.9600, though its AUPRC of 0.6621 highlights the significant gap that can emerge between these metrics under class imbalance [11].

When interpreting these values, the guidelines in Table 2 provide useful reference points. Models achieving AUC values above 0.90 can be considered to offer excellent discriminatory power, suggesting high promise for guiding experimental validation [26]. However, it is crucial to consider the 95% confidence intervals around these point estimates, as a wide confidence interval may indicate unreliable performance despite a high point estimate [26].

The observed performance gains in recent models can be attributed to several architectural innovations: the integration of multiple data modalities (2D/3D molecular structures, protein sequences, interaction networks) [12]; the use of pre-training on large-scale molecular databases [28]; the incorporation of biological knowledge through regularization [14]; and advanced graph learning techniques that capture both local and global network structures [29] [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Evaluation Frameworks

Robust evaluation of DTI prediction models requires careful experimental design to avoid optimistic performance estimates. The field has converged on several key methodological practices:

Data Splitting Strategies: To assess model generalizability, datasets are typically divided using scaffold-based splits, where the training, validation, and test sets contain distinct molecular substructures [28]. This approach tests the model's ability to generalize to novel chemical entities rather than merely recognizing structural similarities. Alternative strategies include random splits and time-aware splits that simulate real-world deployment scenarios.

Cross-Validation: Most rigorous evaluations employ k-fold cross-validation (typically 5- or 10-fold) to account for variability in dataset composition and provide more stable performance estimates.

Benchmark Datasets: Commonly used benchmarks include DrugBank [12], Davis [12], KIBA [12], BACE [28], Tox21 [28], and specialized datasets for specific target families such as kinases [28] and cytochrome P450 enzymes [28]. These datasets vary in size, class imbalance, and biological context, enabling comprehensive assessment of model capabilities.

Specialized Protocols for DTI Prediction

Beyond standard evaluation practices, several specialized protocols address unique challenges in DTI prediction:

Cold-Start Evaluation: This scenario tests a model's ability to predict interactions for new drugs or targets not present during training [12]. This is accomplished by ensuring that specific drugs or targets (or both) are exclusively present in the test set, simulating the practical challenge of predicting interactions for novel entities.

Temporal Validation: For drug repurposing applications, models may be evaluated using time-split validation, where training data is limited to interactions discovered before a specific date, and test data consists of interactions discovered after that date.

Case Study Validation: Performance metrics are complemented by targeted case studies focusing on specific therapeutic areas. For example, several studies have validated predictions for Parkinson's disease treatments [29] or anti-SARS-CoV-2 molecules [28], providing concrete evidence of practical utility.

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for DTI Prediction Model Development and Validation. This diagram illustrates the standard experimental protocol from data collection through experimental validation, highlighting key stages and performance assessment components.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for DTI Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experimental Validation | Representative Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Source of candidate drugs for testing | PubChem (10M+ compounds) [28], FDA-approved drug libraries |

| Target Proteins | Production of protein targets for binding assays | Recombinant expression systems, native protein purification |

| Binding Assay Kits | Measurement of direct molecular interactions | Fluorescence-based, radioisotope-based, surface plasmon resonance kits |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Assessment of functional effects in biological context | Cell lines with target overexpression, reporter gene assays |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Automated testing of multiple compound-target pairs | Robotic liquid handling, automated microscopy, multi-well plate readers |

| Bioinformatics Databases | Source of known interactions and structural information | DrugBank [11], HPRD [11], ChEMBL, BindingDB |

| Knowledge Bases | Context for interpreting results and generating hypotheses | Gene Ontology [14], KEGG Pathways, Reactome |

The transition from computational prediction to experimental validation requires access to specialized reagents and resources, as summarized in Table 3. Compound libraries such as PubChem, which contains over 10 million drug-like molecules, provide the chemical starting point for experimental testing [28]. For target production, recombinant expression systems enable the production of purified proteins for in vitro binding assays, while cell-based systems allow assessment of functional effects in more physiologically relevant contexts.

Several experimental methodologies are commonly employed for validation. Binding assays measure direct physical interactions between drugs and targets using techniques such as surface plasmon resonance, fluorescence polarization, or radioligand binding. Functional assays assess the pharmacological consequences of these interactions, such as enzyme inhibition or receptor activation. High-throughput screening platforms enable the efficient testing of thousands of compound-target combinations, dramatically accelerating the validation process.

Critical to this pipeline are comprehensive bioinformatics databases such as DrugBank [11] and HPRD [11], which provide curated information on known drug-target interactions for benchmarking and reference. Biological knowledge bases including Gene Ontology [14] and pathway databases offer essential context for interpreting validation results and generating mechanistic hypotheses.

Diagram 2: Comparative Characteristics and Application Contexts of AUC and AUPRC. This diagram illustrates the distinct properties of each metric and the deployment scenarios where each excels.

The establishment of rigorous performance baselines through metrics like AUC and AUPRC is fundamental to advancing the field of drug-target interaction prediction. For researchers and drug development professionals validating computational predictions with in vitro assays, a nuanced understanding of these metrics enables more informed decision-making in both model selection and experimental prioritization.

AUC remains the gold standard for assessing a model's overall ranking capability, with values above 0.90 indicating excellent discriminatory power suitable for guiding experimental programs [26]. AUPRC provides complementary information, particularly valuable when the primary research objective is identifying high-confidence candidates from the top-ranked predictions [27]. The most robust approach involves considering both metrics alongside their confidence intervals and statistical significance.

As the field progresses, emerging techniques such as evidential deep learning for uncertainty quantification [12] and knowledge-guided representation learning [14] promise to further enhance predictive performance and translational utility. By strategically applying appropriate evaluation metrics and maintaining rigorous validation standards, the research community can continue to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic interventions through computational approaches.

Bridging the Digital and Physical: Designing In Vitro Validation Pipelines

The advent of high-throughput technologies and sophisticated artificial intelligence has revolutionized the initial stages of drug discovery, enabling researchers to generate thousands of potential drug-target interactions (DTIs) through computational methods [30] [31]. While computational predictions provide valuable starting points, the transition from virtual hits to experimentally viable candidates remains a critical bottleneck. This challenge is particularly pronounced in bioinformatics-driven target identification, where the gap between in silico prediction and in vitro validation contributes significantly to attrition rates in later development stages [32] [33].

The fundamental question facing researchers is no longer how to generate computational hits, but how to prioritize them for expensive and time-consuming experimental validation. A systematic prioritization framework that integrates computational confidence metrics with experimentally practical validation strategies is essential for resource-efficient drug discovery. This guide establishes such a framework by comparing multiple prioritization and validation approaches, providing structured methodologies for bridging the computational-experimental divide.

Computational Prioritization: From Initial Hits to Triage

Defining Hit Criteria and Ligand Efficiency Metrics

The first step in transitioning from computational hits to experimental candidates involves establishing clear hit-calling criteria. Analysis of virtual screening studies reveals significant variation in how researchers define a "hit," with only approximately 30% of studies reporting clear, predefined activity cutoffs [34]. The most effective frameworks move beyond simple activity thresholds to incorporate ligand efficiency metrics that normalize biological activity against molecular properties.

Table 1: Established Hit Identification Criteria in Virtual Screening

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Typical Range for Hits | Strategic Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency Measures | IC₅₀, EC₅₀, Kᵢ, Kd | 1-100 µM [34] | Primary activity against intended target |

| Ligand Efficiency | LE (Ligand Efficiency) | ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol/heavy atom [34] | Normalizes potency by molecular size |

| Lipophilic Efficiency | LipE, LLE (Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency) | LipE > 5 [35] | Penalizes excessive lipophilicity |

| Structural Alert | PAINS filters, promiscuity checks | Elimination of flagged compounds [34] | Avoids compounds with problematic motifs |

While sub-micromolar activity is desirable, the majority of successful virtual screening studies employ hit criteria in the low to mid-micromolar range (1-100 µM), particularly for novel targets or scaffolds [34]. This pragmatic approach acknowledges that computational hits serve as starting points for optimization rather than final drug candidates.

The Traffic Light System for Multi-Parameter Hit Triage

Prioritizing computational hits requires evaluating multiple parameters simultaneously. The "Traffic Light" (TL) system provides a visual, quantitative framework for comparing hit series across diverse criteria [35]. This approach assigns scores of 0 (good), 1 (warning), or 2 (bad) across multiple parameters, generating a composite score that enables objective comparison of potential starting points.

Table 2: Example Traffic Light Analysis for Hit Triage [35]

| Evaluation Parameter | Compound A | Compound B | Rationale for Prioritization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency (IC₅₀) | 1.2 µM (+1) | 0.8 µM (0) | Compound B more potent |

| Ligand Efficiency | 0.45 (0) | 0.28 (+2) | Compound A uses molecular size more efficiently |

| cLogP | 2.1 (0) | 4.8 (+2) | Compound A has more favorable lipophilicity |

| Solubility | >200 µM (0) | Not tested (+2) | Compound A demonstrates good solubility |

| Selectivity | 15-fold (0) | 3-fold (+2) | Compound A shows better target specificity |

| Total Score | 1 | 8 | Compound A clearly preferred |

The TL system's flexibility allows research teams to incorporate additional experimental data as it becomes available, creating a dynamic prioritization framework that evolves throughout the hit-to-lead process. Teams can weight categories based on project-specific priorities, though equal weighting generally provides the most unbiased starting point [35].

Experimental Validation Strategies: A Comparative Framework

Orthogonal Corroboration vs. Traditional Validation

The framework of "experimental validation" requires refinement in the modern drug discovery context. Rather than a single gold-standard validation method, orthogonal corroboration using multiple experimental approaches provides greater scientific rigor [30]. This paradigm shift acknowledges that all experimental methods have limitations and that confidence increases when multiple approaches yield consistent results.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Experimental Validation Methods

| Computational Method | Traditional "Gold Standard" | Orthogonal Corroboration | Advantages of Orthogonal Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Calling (WGS/WES) | Sanger sequencing [30] | High-depth targeted sequencing [30] | Better detection of low-frequency variants; more precise VAF estimates |

| Copy Number Aberration Calling | FISH (20-100 cells) [30] | Low-depth WGS of thousands of single cells [30] | Higher resolution for subclonal events; quantitative, statistical thresholds |

| Differential Protein Expression | Western Blot/ELISA [30] | Mass spectrometry (MS) [30] | Higher specificity based on multiple peptides; greater coverage and reproducibility |

| Differentially Expressed Genes | RT-qPCR [30] | RNA-seq [30] | Comprehensive transcriptome coverage; nucleotide-level resolution |

The selection of orthogonal methods should consider throughput, resolution, and quantitative capability. For example, mass spectrometry provides superior protein identification confidence compared to Western blotting when multiple peptides cover significant protein sequence (e.g., >5 peptides covering ~30% of sequence with E value < 10⁻¹⁰) [30].

Assessing Assay Quality and Performance Metrics

Regardless of the specific validation method selected, assessing assay quality is essential for interpreting results accurately. The Z' factor is a critical statistical parameter that evaluates assay robustness by incorporating both the assay signal dynamic range and data variation [36]:

Assays with Z' values between 0.5 and 1.0 are considered excellent for screening purposes, while values below 0.5 indicate poor assay quality unsuitable for reliable hit validation [36]. Additional metrics such as signal-to-background (S/B) ratio and EC₅₀/IC₅₀ values for reference compounds provide further assay characterization [36].

For concentration-response assays, the Toxicity Separation Index (TSI) and Toxicity Estimation Index (TEI) represent advanced performance metrics that evaluate how well in vitro data predict in vivo effects. These metrics are particularly valuable in safety assessment and toxicology prediction, where TSI values approaching 1.0 indicate excellent separation between toxic and non-toxic compounds [37].

Integrated Workflow: From Prediction to Confirmation

The Prioritization and Validation Pipeline

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete pathway from computational hit identification to experimental candidate confirmation, integrating both computational and experimental elements:

Prioritization and Validation Workflow: This integrated pipeline shows the key decision points from initial computational hits through experimental confirmation, highlighting the critical transition between phases.

Target Engagement and Mechanism of Action

Confirmation of direct target engagement represents a crucial step in validating computational predictions. Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a powerful method for demonstrating direct binding in physiologically relevant environments [4]. Unlike purely biochemical assays, CETSA confirms target engagement in intact cells and can be extended to tissue samples, providing a translational bridge between in vitro and in vivo systems [4].

For programs targeting specific mechanism of action (MoA) classes, distinguishing between activation and inhibition is essential. Recent computational frameworks like DTIAM enable prediction of activation/inhibition mechanisms alongside binding affinity, though these predictions require experimental confirmation using appropriate functional assays [31]. The expansion of mechanism-specific validation assays addresses a critical gap in early discovery, where misinterpretation of compound MoA contributes to later-stage failures.

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Validation Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays (luciferase), CETSA [36] [4] | Measure functional activity in cellular context | Prioritize systems with high Z' factors (>0.5) and physiological relevance |

| Target Engagement Reagents | CETSA kits, SPR chips, binding assay reagents [4] | Confirm direct compound-target interaction | Cellular vs. biochemical context; throughput requirements |

| Orthogonal Detection Reagents | MS-compatible reagents, specific antibodies, sequencing kits [30] | Enable multiple validation approaches | Compatibility across platforms; specificity validation |

| ADMET Profiling Tools | PAMPA plates, microsomal stability kits, CYP inhibition assays [35] | Assess drug-like properties early | Balance between throughput and predictivity; species relevance |