From Sequencing to Confirmation: A Comprehensive Guide to qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Data

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-Seq findings with qPCR.

From Sequencing to Confirmation: A Comprehensive Guide to qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Data

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-Seq findings with qPCR. It covers the foundational reasons for this essential step, detailed methodological protocols for assay design and validation, practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and a framework for comparative analysis to ensure data robustness. By synthesizing current best practices and validation guidelines, this resource aims to bridge the gap between high-throughput discovery and precise, reproducible confirmation, ultimately enhancing the reliability of gene expression data in biomedical research.

Why Validate? The Critical Link Between RNA-Seq Discovery and qPCR Confirmation

Understanding the Technical Limitations of RNA-Seq and qPCR

In the field of genomics and molecular biology, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) have emerged as two foundational technologies for gene expression analysis. RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, enabling discovery of novel transcripts and comprehensive profiling of gene expression patterns [1] [2]. In contrast, qPCR offers a highly sensitive, specific, and quantitative method for validating targeted gene expression changes with exceptional precision [3]. Despite their synergistic relationship, each technology possesses distinct technical limitations that researchers must understand to properly design experiments, interpret results, and validate findings.

The integration of RNA-seq and qPCR has become particularly important in advancing biomedical research and drug development. RNA-seq drives insights that shape scientific decisions and commercial strategies in pharmaceutical companies, while qPCR provides the rigorous validation required for clinical and regulatory applications [4] [5]. This technical guide examines the core limitations of both technologies, provides methodologies for cross-validation, and offers best practices to ensure data reliability within the context of a broader thesis on qPCR validation of RNA-seq findings.

Technical Limitations of RNA-Seq Technology

Bioinformatics Challenges and Reference Genome Biases

A primary limitation of RNA-seq lies in its substantial dependency on bioinformatics processing and analysis. Unlike microarray techniques that RNA-seq is rapidly replacing, the bottleneck of RNA-seq technology is clearly visible in data analysis rather than data generation [1]. This computational challenge is particularly pronounced for detecting novel transcripts and analyzing highly polymorphic gene families.

The extreme polymorphism at HLA genes, for example, creates significant technical issues for RNA-seq analysis. Standard alignment methods that map short reads to a single reference genome often fail because many reads contain large numbers of differences with respect to the reference genome, resulting in misalignment or complete failure to align [6]. Furthermore, the HLA region consists of gene families formed through successive duplications, containing segments very similar between paralogs, which leads to cross-alignments among genes and biased quantification of expression levels [6].

Annotation gaps present another major challenge, particularly for noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). Although evidence suggests most of the genome is transcribed into RNA, the majority of these RNAs are not translated into proteins, and their annotations remain poor, making RNA-seq analysis particularly challenging for these transcripts [1]. Novel transcripts that are identified from RNA-seq must be examined carefully before proceeding to biological experiments, as a significant proportion may represent technical artifacts rather than genuine biological discoveries [1].

Library Preparation and Experimental Design Considerations

RNA-seq library preparation introduces several technical variables that can impact data quality and interpretation. Table 1 summarizes key library preparation considerations and their implications for data analysis.

Table 1: RNA-seq Library Preparation Considerations and Technical Implications

| Preparation Factor | Options | Technical Implications | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strandedness | Stranded vs. unstranded | Stranded libraries preserve transcript orientation information, critical for identifying novel RNAs or overlapping transcripts on opposite strands [2]. | Stranded libraries are preferred for better preservation of transcript information, despite higher cost and complexity [2]. |

| rRNA Depletion | Poly-A selection vs. rRNA depletion | rRNA depletion increases cost-effectiveness by reducing ribosomal reads (∼80% of cellular RNA), but may introduce variability and off-target effects [2]. | Assess depletion strategy impact on genes of interest; RNAseH methods offer more reproducible enrichment than precipitating bead methods [2]. |

| RNA Quality | RIN score assessment | Degraded RNA (RIN <7) biases against longer transcripts; poly-A selection requires intact mRNA [2]. | Use random priming and rRNA depletion for degraded samples; prioritize high-quality RNA (RIN >7) for standard applications [2]. |

Additional technical biases in RNA-seq include batch effects, library preparation artifacts, GC content biases, and the fundamental limitation that RNA-seq does not count absolute numbers of RNA copies in a sample but rather yields relative expression within a sample [6] [2]. These factors collectively contribute to inaccuracies in expression quantification that must be addressed through careful experimental design and validation.

Technical Limitations of qPCR Technology

Assay Design and Validation Requirements

While qPCR is renowned for its sensitivity and precision, it requires rigorous validation to ensure data reliability. Without proper validation, researchers risk drawing erroneous conclusions that could lead to misdirected research investments or, in clinical settings, patient mismanagement [3]. The powerful amplification efficiency of PCR that enables detection of minute quantities of nucleic acids also makes the technique exceptionally vulnerable to contamination and amplification artifacts.

The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines established in 2009 aimed to address these concerns by promoting standardization and transparency in qPCR experiments [3]. Despite these efforts, a noticeable lack of technical standardization persists in the field, particularly as qPCR applications expand into clinical research and regulated bioanalytical laboratories [4] [3].

Key Validation Parameters for Reliable qPCR Results

Table 2 outlines the critical validation parameters that must be established for any qPCR assay to generate reliable, quantitative data.

Table 2: Essential qPCR Validation Parameters and Specifications

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Acceptance Criteria | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusivity | Measures how well the qPCR detects all intended target strains/isolates [3]. | Detection of all genetic variants within intended scope (e.g., influenza A H1N1, H1N2, H3N2). | Ensures comprehensive target detection; poor inclusivity leads to false negatives for certain variants [3]. |

| Exclusivity (Cross-reactivity) | Assesses how well the qPCR excludes genetically similar non-targets [3]. | No amplification of non-target species (e.g., influenza B in an influenza A assay). | Prevents false positives from cross-reactive sequences; critical for assay specificity [3]. |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Range of template concentrations over which signal is directly proportional to input [3]. | Typically 6-8 orders of magnitude; linearity (R²) ≥ 0.980; efficiency 90-110% [3]. | Determines quantitative reliability; samples must fall within this range for accurate quantification [3]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration of target that can be reliably detected [3]. | Determined through dilution series of standards with known concentrations. | Defines assay sensitivity and determines applicability for low-abundance targets [3]. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest concentration of target that can be reliably quantified [3]. | Determined through statistical analysis of precision at low concentrations. | Establishes the quantitative range distinct from mere detection [3]. |

Both inclusivity and exclusivity validation tests should be performed in two parts: in silico analysis using genetic databases to check oligonucleotide, probe, and amplicon sequences for similarities/differences among targets/non-targets, followed by experimental validation at the bench to confirm performance [3]. This comprehensive approach ensures the qPCR assay will perform reliably with actual experimental samples.

Cross-Technology Validation: Bridging RNA-Seq and qPCR

Comparative Performance and Correlation Challenges

Direct comparisons between RNA-seq and qPCR reveal significant challenges in cross-technology validation. A comprehensive benchmarking study comparing five RNA-seq workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, and Salmon) against whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data for 18,080 protein-coding genes demonstrated generally high expression correlations, with Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from R² = 0.798 to 0.845 [7]. However, when comparing gene expression fold changes between samples, approximately 15-19% of genes showed inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR data [7].

Notably, a 2023 study focusing on HLA class I genes found only moderate correlation between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq for HLA-A, -B, and -C (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53), highlighting the particular challenges in quantifying expression of highly polymorphic genes [6]. This discrepancy underscores the importance of considering both technical and biological factors when comparing quantifications from different molecular phenotypes or using different techniques.

Methodological Framework for qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Findings

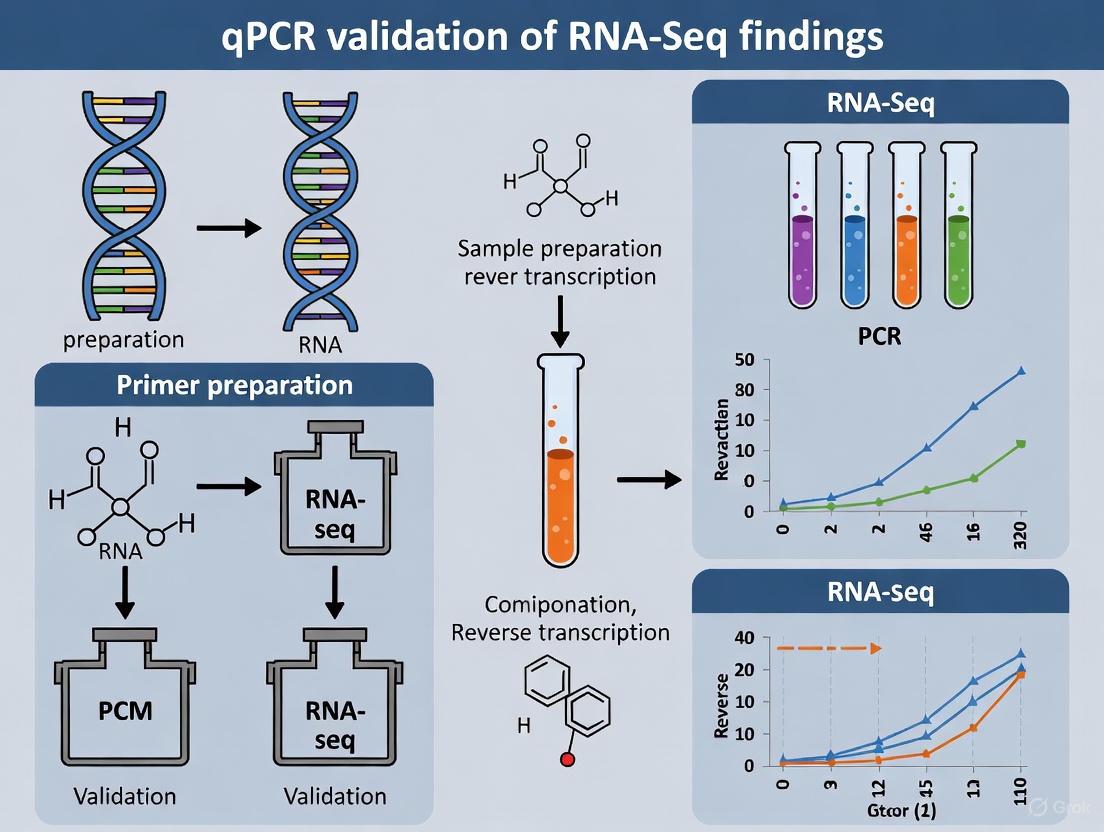

Diagram 1: RNA-seq and qPCR validation workflow.

The validation workflow depicted in Diagram 1 provides a systematic approach for confirming RNA-seq findings using qPCR. This process begins with identifying candidate differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data, prioritizing based on both statistical significance (p-value) and biological relevance. Researchers should select 5-10 key targets representing different expression levels and functional categories for validation.

For the qPCR assay design and optimization phase, several critical reagents and solutions are required. Table 3 details the essential research reagent solutions needed for implementing this validation framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Amplify and detect target sequences | Must be validated for inclusivity/exclusivity; designed to avoid known SNPs; typically used at 100-500 nM final concentration [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid Standards | Generate standard curves for quantification | Commercial standards or samples of known concentration; used in 7-point 10-fold dilution series to establish linear dynamic range [3]. |

| Reverse Transcription Reagents | Convert RNA to cDNA | Must use consistent enzyme and protocol across all samples to minimize technical variation [6]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provide optimal reaction conditions | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, salts; selection affects efficiency and sensitivity [3]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve sample integrity | Critical for blood samples (e.g., PAXgene); prevents degradation between collection and processing [2]. |

The comprehensive qPCR validation phase must establish all parameters outlined in Table 2, with particular emphasis on determining the linear dynamic range using a seven-point 10-fold dilution series of DNA standards run in triplicate [3]. Only when samples fall within this validated linear range can results be considered truly quantitative.

Best Practices and Experimental Protocols

Integrated RNA-seq and qPCR Validation Protocol

Based on the technical limitations and validation challenges discussed, the following integrated protocol provides a robust methodology for cross-platform validation:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

RNA-Seq Library Construction and Sequencing

- Use stranded library protocols (e.g., TruSeq stranded mRNA kit) to preserve transcript orientation information [2] [8]

- Implement ribosomal depletion for cost-effectiveness if rRNA genes are not of interest [2]

- Sequence on established platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000) with Q30 >90% and PF >80% [8]

RNA-Seq Data Analysis

- Process reads using multiple workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq and Kallisto) to assess consistency [7]

- For polymorphic genes (e.g., HLA), use specialized pipelines that account for known diversity rather than single reference genome alignment [6]

- Identify candidate differentially expressed genes using established thresholds (e.g., FPKM ≥0.1, fold change >1) [1] [7]

qPCR Assay Validation

- Perform in silico analysis of oligonucleotide specificity using genetic databases [3]

- Validate linear dynamic range using 7-point 10-fold dilution series of standards [3]

- Confirm amplification efficiency (90-110%) and linearity (R² ≥ 0.980) [3]

- Test inclusivity with up to 50 well-defined strains of target organisms [3]

- Verify exclusivity against genetically similar non-target species [3]

Cross-Platform Correlation Analysis

Analysis of Discordant Results and Troubleshooting

When RNA-seq and qPCR results show significant discrepancies (ΔFC >2), investigators should consider these potential sources of error:

- RNA-seq alignment issues: For polymorphic genes or novel transcripts, misalignment can cause inaccurate quantification [1] [6]

- qPCR specificity problems: Primers may not detect all variants or may amplify non-target sequences [3]

- Transcript complexity: Genes with multiple isoforms may be quantified differently by each technology [7]

- Dynamic range limitations: Targets near the limit of detection for either technology show higher variability [7] [3]

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting discordant RNA-seq and qPCR results.

RNA-seq and qPCR each present distinct technical limitations that researchers must navigate to generate reliable gene expression data. RNA-seq offers comprehensive transcriptome coverage but suffers from bioinformatics complexities, reference genome biases, and library preparation artifacts. qPCR provides exceptional sensitivity and precision but requires rigorous validation to ensure specificity and quantitative accuracy. The integration of these technologies through systematic validation frameworks enables researchers to leverage the strengths of each approach while mitigating their respective limitations.

As the biotechnology industry increasingly relies on transcriptomic data to drive drug discovery and clinical applications, the professionals who master both RNA-seq analysis and qPCR validation position themselves at the forefront of biomedical innovation [5]. By understanding the technical considerations outlined in this guide and implementing robust validation protocols, researchers can enhance the reliability of their findings, ultimately advancing scientific knowledge and improving patient outcomes through more accurate molecular profiling.

The Importance of Analytical and Clinical Validation in Biomarker Research

The translation of biomarker candidates from promising research findings into clinically useful tools is a challenging process, characterized by a high failure rate. It is estimated that for every 100 biomarker candidates that look promising in the lab, only 5 ever make it to clinical use—a 95% failure rate [9]. This high attrition underscores the critical importance of rigorous validation procedures. Within the specific context of validating RNA-Seq findings using qPCR, this process becomes particularly crucial, as it bridges the gap between high-throughput discovery research and clinically applicable diagnostic assays [10] [11].

The validation pathway encompasses two distinct but complementary phases: analytical validation, which proves that the test itself measures the biomarker accurately and reliably, and clinical validation, which demonstrates that the biomarker measurement provides meaningful information about a patient's health status or disease [9] [10]. For biomarkers intended to support clinical decision-making, both phases must be successfully completed, and the evidentiary requirements are stringent [9]. This guide examines the principles, methodologies, and best practices for achieving robust analytical and clinical validation of biomarkers, with particular emphasis on the qPCR validation of RNA-Seq discoveries.

Core Concepts: Analytical versus Clinical Validation

Understanding the distinction between analytical and clinical validity is fundamental to designing successful biomarker development strategies. These two pillars of validation address different questions and require different experimental approaches and success criteria.

Analytical validation answers the question: "Does the test work in the laboratory?" It establishes that the analytical method itself is performing correctly. This involves demonstrating that the assay consistently measures the biomarker with the required precision, accuracy, and reliability across different conditions [10]. Key parameters include sensitivity, specificity, precision, and limits of detection and quantification [12] [10].

Clinical validation answers the question: "Does the test result provide clinically useful information?" It establishes that the biomarker measurement is reliably associated with the specific clinical phenotype, outcome, or endpoint it claims to predict [9] [10]. This involves assessing diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, predictive values, and clinical utility in relevant patient populations [10].

The relationship between these concepts and the broader development pathway is structured, progressing from technical performance to clinical application, as illustrated below:

A biomarker's path from discovery to clinical application.

Biomarker Categories and Context of Use

Biomarkers are categorized by their intended application, which directly determines the validation requirements. According to consensus guidelines, biomarkers can be structured into several categories based on their intended use: susceptibility/risk, diagnostic, monitoring, prognostic, predictive, pharmacodynamics/response, and safety biomarkers [10]. The context of use (COU) is a formal statement describing the specific application and interpretation of the biomarker, while the fit-for-purpose concept recognizes that the level of validation should be sufficient to support the intended COU [10]. For example, a biomarker intended to stratify patients for targeted therapy would require more rigorous clinical validation than one used for early research hypothesis generation.

Analytical Validation for qPCR Biomarker Assays

Analytical validation establishes the fundamental reliability of the measurement technique itself. For qPCR assays validating RNA-Seq findings, this process involves a series of deliberate experiments to characterize the assay's performance parameters.

Key Analytical Performance Parameters

The following parameters form the core of analytical validation for qPCR-based biomarker assays:

Linearity and Dynamic Range: The assay's ability to provide results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte across a specified range. This is typically established using a dilution series of the target nucleic acid [12]. For example, in the development of a qPCR assay for residual Vero DNA, researchers established a standard curve with concentrations ranging from 0.3 fg/μL to 30 pg/μL, demonstrating excellent linearity across this range [12].

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The LOD is the lowest concentration of analyte that can be detected but not necessarily quantified, while the LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [12] [10]. In the Vero DNA qPCR assay, the LOD was determined to be 0.003 pg/reaction, while the LOQ was 0.03 pg/reaction [12].

Precision and Accuracy: Precision refers to the closeness of agreement between independent measurements (repeatability and reproducibility), while accuracy (trueness) refers to the closeness of measured values to the true value [10]. These are typically expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) and recovery rates, respectively. For instance, the Vero DNA qPCR assay demonstrated RSD values ranging from 12.4% to 18.3% across samples, with recovery rates between 87.7% and 98.5% [12].

Specificity: The ability of the assay to detect only the intended target without cross-reacting with similar, non-target sequences [10]. This is particularly important when validating RNA-Seq findings, as closely related gene family members or splice variants may cause false positives. Specificity should be tested against a panel of related and unrelated samples [12] [13].

Table 1: Key Analytical Validation Parameters for qPCR Biomarker Assays

| Parameter | Definition | Acceptance Criteria Examples | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration | R² > 0.98 [12] | Serial dilutions of target nucleic acid |

| Dynamic Range | Interval between upper and lower concentration with demonstrated linearity | 6-8 orders of magnitude for qPCR | Serial dilutions spanning expected concentrations |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration detectable but not necessarily quantifiable | 0.003 pg/reaction [12] | Probit analysis or signal-to-noise approach |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest concentration measurable with acceptable precision and accuracy | 0.03 pg/reaction [12] | Lowest concentration with CV < 25% and 80-120% recovery |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent measurements | CV < 15-20% [9] | Repeated measurements within and between runs |

| Accuracy | Closeness of measured value to true value | Recovery rate 80-120% [9] | Comparison with reference method or spike-recovery |

| Specificity | Ability to measure only the intended analyte | No cross-reactivity with related targets [12] [13] | Testing against panel of non-target sequences |

Reference Gene Selection and Validation

A critical aspect of qPCR validation of RNA-Seq data is the selection of appropriate reference genes for normalization. Traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) may exhibit variable expression under different biological conditions, potentially leading to misinterpretation of results [14]. RNA-Seq data itself can be leveraged to identify more stable reference genes specifically suited to the experimental context [14] [15].

The GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) software represents one approach to this challenge, using transcript per million (TPM) values from RNA-Seq data to identify optimal reference genes based on criteria including expression greater than zero in all libraries, low variability between libraries (standard variation < 1), absence of exceptional expression in any library, high expression level (average of log2 expression > 5), and low coefficient of variation (< 0.2) [14]. This methodology was successfully applied in a study of endometrial decidualization, where RNA-Seq data from human endometrial stromal cells identified Staufen double-stranded RNA binding protein 1 (STAU1) as a stable reference gene, outperforming traditionally used references like β-actin [15].

Clinical Validation: Establishing Clinical Relevance

Clinical validation moves beyond technical performance to establish the relationship between the biomarker measurement and clinical endpoints. This phase asks whether the biomarker reliably correlates with or predicts the biological process, pathological state, or response to intervention that it claims to [10].

Clinical Performance Metrics

The clinical utility of a biomarker is assessed through several key metrics, each addressing a different aspect of clinical performance:

Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity: Sensitivity (true positive rate) measures the proportion of actual positives correctly identified, while specificity (true negative rate) measures the proportion of actual negatives correctly identified [10]. The FDA typically expects high sensitivity and specificity for diagnostic biomarkers, often ≥80% depending on the specific indication [9].

Positive and Negative Predictive Values: These metrics indicate the probability that a positive (PPV) or negative (NPV) test result correctly predicts the presence or absence of the condition [10]. Unlike sensitivity and specificity, predictive values are dependent on disease prevalence in the population.

Clinical Utility: Perhaps the most important question is whether using the biomarker actually improves patient outcomes or clinical decision-making [9]. This requires demonstrating that clinical decisions change when doctors have the biomarker information, and that these changes lead to better results.

Table 2: Key Clinical Validation Parameters for Biomarker Assays

| Parameter | Definition | Formula | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Sensitivity | Proportion of true positives correctly identified | True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) | High sensitivity critical for rule-out tests |

| Diagnostic Specificity | Proportion of true negatives correctly identified | True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) | High specificity critical for rule-in tests |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Probability disease is present when test is positive | True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives) | Highly dependent on disease prevalence |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Probability disease is absent when test is negative | True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Negatives) | Highly dependent on disease prevalence |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Overall measure of diagnostic performance across all thresholds | Area under ROC curve | AUC ≥0.80 often required for clinical utility [9] |

| Likelihood Ratios | How much a test result changes the odds of having a disease | Sensitivity/(1-Specificity) for LR+; (1-Sensitivity)/Specificity for LR- | Independent of prevalence |

Validation Study Design Considerations

Robust clinical validation requires careful study design with particular attention to:

Population Selection: The study population must adequately represent the intended-use population, considering factors such as disease stage, comorbidities, demographics, and prior treatments [9] [11]. For example, in the development of a five-gene signature for pancreatic cancer, researchers validated their biomarker in peripheral blood samples from 55 participants (30 patients with confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and 25 healthy controls), ensuring relevance to the intended minimally invasive application [11].

Blinding and Randomization: To minimize bias, both sample processing and data analysis should be performed blinded to clinical outcomes and patient groups [10].

Multi-site Validation: Reproducibility across different laboratories and operators strengthens the evidence for clinical validity [16]. For instance, a multi-laboratory validation study of a Salmonella qPCR method involved 14 laboratories each analyzing 24 blind-coded samples, demonstrating the method's reproducibility across sites [16].

Statistical Power: Studies must include sufficient sample sizes to detect clinically meaningful effects with appropriate statistical power [9]. Underpowered studies are a common cause of failure in biomarker validation.

Integrated Workflow: RNA-Seq to Clinically Validated qPCR Assay

The complete pathway from RNA-Seq discovery to clinically validated qPCR assay involves multiple stages, each with specific quality control checkpoints. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

Integrated RNA-Seq to qPCR clinical validation workflow.

Case Study: Pancreatic Cancer Biomarker Signature

A comprehensive example of this workflow is demonstrated in a study that integrated traditional machine learning with qPCR validation to identify solid drug targets in pancreatic cancer [11]. Researchers analyzed 14 public pancreatic cancer datasets comprising 845 samples using random-effects meta-analysis and forward-search optimization to identify a robust five-gene signature (LAMC2, TSPAN1, MYO1E, MYOF, and SULF1). This signature achieved a summary AUC of 0.99 in training datasets and 0.89 in external validation datasets [11].

For qPCR validation, the team recruited 55 participants (30 pancreatic cancer patients and 25 healthy controls), collected peripheral blood samples under standardized conditions, extracted RNA with quality control (RIN > 7), performed cDNA synthesis, and conducted qPCR analysis with GAPDH as the internal control [11]. The differential expression of all five genes was confirmed, demonstrating utility in distinguishing cancer from normal conditions with an AUC of 0.83, thus validating both the analytical performance and initial clinical relevance of the signature [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful validation of RNA-Seq findings via qPCR requires specific laboratory reagents, instruments, and consumables. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their applications in the validation workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Findings

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | TRIzol LS reagent, QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [11] [13] | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids from biological samples | RNA integrity number (RIN) >7 recommended for qPCR analysis [11] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System [11] | Conversion of RNA to cDNA for qPCR amplification | Critical step ensuring representative cDNA library |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green Master Mix, Probe qPCR Mix [11] [13] | Provides enzymes, buffers, dNTPs for amplification reaction | Choice between SYBR Green vs. probe-based depends on specificity requirements |

| Primers & Probes | Custom-designed sequences [12] [13] [11] | Target-specific amplification and detection | Designed to span exon-exon junctions; validated for efficiency (90-110%) |

| Reference Genes | GSV-identified candidates, STAU1 [14] [15] | Normalization of technical variation | Should be validated for stability in specific experimental system |

| Quality Control Instruments | NanoDrop spectrophotometer, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer [11] | Assessment of nucleic acid quantity and quality | Essential for pre-analytical quality control |

| qPCR Instruments | ABI 7900HT, Bio-rad systems [11] [13] | Amplification and detection of target sequences | Should be regularly calibrated and maintained |

The journey from RNA-Seq discovery to clinically validated qPCR assay is complex and demanding, requiring rigorous attention to both analytical and clinical validation principles. By implementing comprehensive analytical validation to ensure technical reliability and well-designed clinical validation to establish medical utility, researchers can significantly improve the translation rate of biomarker candidates into clinically useful tools. As technologies advance—particularly with the integration of AI and machine learning approaches—and regulatory pathways evolve, the validation process continues to become more efficient and standardized. However, the fundamental requirement remains: robust evidence that a biomarker not only can be measured accurately but also provides meaningful information that improves patient care.

In the rigorous pipeline of validating RNA-Seq findings with quantitative PCR (qPCR), establishing robust performance metrics is not merely a procedural step—it is the foundation for generating reliable, interpretable, and actionable data. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Values is crucial for assessing the diagnostic power of a qPCR assay and ensuring its suitability for regulatory filings. These metrics move beyond theoretical concepts to become quantifiable indicators of an assay's ability to correctly identify true positives, reject true negatives, and ultimately, deliver on the promise of precision medicine. This guide details the experimental frameworks and calculations necessary to define these metrics within the context of qPCR validation, providing a critical chapter in the broader thesis on best practices.

Core Definitions and Diagnostic Framework

The performance of a qPCR assay used for diagnostic or validation purposes is evaluated based on its outcomes compared to a known "ground truth" or reference standard. The interplay of these outcomes is best visualized using a confusion matrix, which forms the basis for all subsequent calculations.

Table 1: The Confusion Matrix for a Binary qPCR Assay

| Condition Present (True Positive) | Condition Absent (True Negative) | |

|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | True Positive (TP) | False Positive (FP) |

| Test Negative | False Negative (FN) | True Negative (TN) |

From this matrix, the key performance metrics are derived:

- Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): The proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified by the assay. It answers: "If the target is present, how likely is the assay to detect it?"

- Formula: Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN)

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): The proportion of actual negatives that are correctly identified by the assay. It answers: "If the target is absent, how likely is the assay to be negative?"

- Formula: Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): The probability that a subject with a positive test result truly has the target. This is highly dependent on the prevalence of the target in the population.

- Formula: PPV = TP / (TP + FP)

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV): The probability that a subject with a negative test result truly does not have the target.

- Formula: NPV = TN / (TN + FN)

The relationship between the assay result and the true condition status, and how the four key metrics are calculated, can be summarized in the following workflow:

Experimental Protocols for Metric Determination

Determining these metrics requires a carefully designed validation study using samples with a known condition status. The following protocol outlines the key steps.

Panel Composition and Reference Standards

The first and most critical step is to assemble a well-characterized sample panel.

- Positive Controls: These are samples known to contain the target RNA transcript(s) of interest identified by RNA-Seq. The panel should encompass the expected biological variation, including different disease subtypes, stages, or concentrations near the assay's limit of detection to challenge sensitivity [8] [17].

- Negative Controls: These are samples confirmed to lack the target transcript. To rigorously challenge specificity, this set should include:

- Biologically Negative Samples: From healthy donors or relevant control groups.

- Analytically Challenging Negatives: Samples with closely related but distinct RNA sequences, or samples that may cause cross-reactivity (e.g., from other tissues or organisms) [3]. This tests exclusivity.

- Reference Method: The "ground truth" must be established by a robust method. This is typically the original RNA-Seq data, but it is strengthened by confirmation with an orthogonal method, such as a different qPCR assay, digital PCR (dPCR), or a standardized clinical diagnosis [8] [18].

qPCR Assay Execution

The assembled panel is run through the qPCR assay under validation.

- Blinding: The operator should be blinded to the reference standard status of the samples to prevent bias.

- Replication: Each sample should be run in multiple technical replicates (e.g., triplicate) to account for well-to-well variability.

- Controls: Include no-template controls (NTCs) to monitor for contamination (false positives) and positive control templates to ensure the assay is functioning correctly.

Data Analysis and Metric Calculation

After the run, Cq values are collected, and results are classified as positive or negative based on a predetermined Cq cutoff.

- Result Classification: Compare the qPCR result (Positive/Negative) for each sample against its known status from the reference standard.

- Populate the Confusion Matrix: Tally the results into the four categories: TP, FP, TN, FN.

- Calculate Metrics: Use the formulas in the previous section to calculate Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, and NPV.

Case Study in Biomarker Validation

A 2025 study on ovarian cancer detection provides a compelling example of this process in practice. The researchers used RNA-Seq on platelet-derived RNA to identify a panel of 10 splice-junction biomarkers. They then developed a qPCR-based algorithm to validate these findings for early cancer detection [19].

Table 2: Performance Metrics from an Ovarian Cancer qPCR Validation Study

| Metric | Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 94.1% | The assay correctly identified 94.1% of the patients with ovarian cancer (including high-grade serous ovarian cancer) [19]. |

| Specificity | 94.4% | The assay correctly identified 94.4% of the patients with benign tumors or as asymptomatic controls [19]. |

| AUC | 0.933 | The Area Under the ROC Curve, a measure of overall diagnostic accuracy, was 0.933, indicating excellent performance [19]. |

Another study developing an RNA biomarker panel for Alzheimer's disease from whole blood demonstrated the impact of high specificity, achieving over 95% specificity and a positive predictive value (PPV) over 90%, which is critical for minimizing false alarms in a clinical setting [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The reliability of the performance metrics is directly dependent on the quality of the reagents and materials used in the validation process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Biobank Samples | Provide the positive and negative samples for the validation panel. | Ensure samples are well-annotated with clinical/data history. Source from reputable providers [17]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, contaminant-free RNA from sample matrices. | Select kits optimized for your sample type (e.g., blood, tissue, FFPE). Assess RNA integrity (RIN ≥7) [8] [17]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Convert RNA to cDNA for qPCR amplification. | Use kits with high fidelity and efficiency. Control for genomic DNA contamination [20]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides the enzymes, buffers, and dNTPs for amplification. | Choose probe-based (e.g., TaqMan) for superior specificity. Validate primer efficiency (90–110%) [3] [20]. |

| Primers & Probes | Confer specificity by binding to the target sequence identified by RNA-Seq. | Design to span exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification. Empirically test multiple candidates [20]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Act as an endogenous control for sample input and quality. | Do not assume traditional housekeeping genes are stable. Use software (e.g., GSV) to select stable genes from your RNA-Seq data [14]. |

Defining sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values is a non-negotiable component of the qPCR validation workflow. These metrics transform a qualitative assay into a quantitatively reliable tool, enabling researchers to state with confidence the probability that their results reflect biological reality. By adhering to rigorous experimental designs—employing well-characterized sample panels, using orthogonal confirmation methods, and meticulously calculating outcomes—scientists can generate data that not only validates RNA-Seq discoveries but also meets the stringent standards required for advancing drug development and clinical diagnostics.

The Role of Validation in Reproducible Research and Clinical Translation

The translation of research findings, particularly from powerful discovery tools like RNA-Seq, into clinically applicable diagnostics or therapeutic targets presents a significant bottleneck in modern biomedical research. The noticeable lack of technical standardization remains a huge obstacle, contributing to a well-documented reproducibility crisis [10]. For instance, despite thousands of published studies on noncoding RNA biomarkers, very few have been successfully implemented in clinical practice, often due to contradictory findings between studies [10]. Validation serves as the critical bridge between exploratory research and clinical application, ensuring that molecular observations are robust, reliable, and suitable for informing decisions about patient care.

This guide examines the role of validation within the context of verifying RNA-Seq findings using quantitative PCR (qPCR), a common workflow in translational research. We focus on the necessary steps that need to be taken toward the appropriate validation of qRT-PCR workflows for clinical research, providing a tool for basic and clinical researchers for the development of validated assays in the intermediate steps of biomarker research [10]. By defining a Clinical Research (CR) level validation, researchers can more easily transition Research Use Only (RUO) assays toward In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) status, ultimately impacting clinical management through improved diagnosis, prognosis, prediction, and therapeutic monitoring [10].

Validation Fundamentals: Concepts and Terminology

Key Validation Principles

The validation process is guided by several fundamental principles that determine its stringency and scope. The Context of Use (COU) is a statement that describes the appropriate use of a product or test, while the Fit-for-Purpose (FFP) concept concludes that the level of validation is sufficient to support its COU [10]. These principles acknowledge that the extent of validation required for a biomarker used in early-phase research differs substantially from one intended to guide therapeutic decisions.

Validation encompasses both analytical and clinical performance. Analytical validation ensures the test itself is reliable and measures what it claims to measure, whereas clinical validation establishes that the test accurately identifies or predicts a clinical condition or status [10].

Glossary of Essential Validation Terms

- Analytical Precision: Closeness of two or more measurements to each other [10].

- Analytical Sensitivity: The ability of a test to detect the analyte (often reported as the Limit of Detection) [10].

- Analytical Specificity: The ability of a test to distinguish target from nontarget analytes [10].

- Analytical Trueness/Accuracy: Closeness of a measured value to the true value [10].

- Clinical Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): Proportion of positives that are correctly identified [10].

- Clinical Specificity (True Negative Rate): Proportion of negatives that are correctly identified [10].

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): The ability of a test to identify disease in individuals with positive results [10].

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV): The ability of a test to identify the absence of disease in individuals with negative test results [10].

Analytical Validation: Frameworks and Performance Criteria

Validation Frameworks for PCR Assays

For PCR-based assays supporting cell and gene therapy development, cross-industry working groups have established frameworks to harmonize approach in the absence of specific regulatory guidance [20]. These frameworks cover critical assays including biodistribution (characterizing therapy distribution and persistence), transgene expression, viral shedding, and cellular kinetics [20].

The validation process involves multiple stages, beginning with defining the clinical need and developing a validation plan, followed by analytical verification, and continuing into ongoing validation maintenance during clinical use [21]. This continuous process ensures the assay's performance remains consistent and reliable.

Establishing Analytical Performance Standards

The table below outlines key analytical performance parameters and typical validation criteria for qPCR assays used in translational research:

Table 1: Key Analytical Performance Parameters for qPCR Validation

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Trueness | Closeness to true value [10] | Spike-recovery experiments using known quantities of target in relevant matrix [21] [20] |

| Precision | Repeatability (within-run) and reproducibility (between-run) [10] | Multiple replicates across days, operators, and instruments [21] [20] |

| Analytical Sensitivity (LOD) | Lowest concentration reliably detected [10] | Probabilistic models (e.g., Probit) or dilution series near detection limit [21] [20] |

| Linearity & Dynamic Range | Range over which response is linearly proportional to concentration | Serial dilutions across expected concentration range [20] |

| Specificity | Ability to distinguish target from non-target sequences [10] | Testing against closely related sequences and background nucleic acids [21] [20] |

| Robustness/Ruggedness | Resistance to small, deliberate changes in protocol | Varying reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, time, reagent lots) [21] |

For clinical RNA-Seq tests, validation involves establishing reference ranges for each gene and junction based on expression distributions from control data, then evaluating clinical performance using positive samples with previously identified diagnostic findings [22] [18]. This process typically involves dozens to hundreds of samples, with one recent study using 130 samples (90 negative and 40 positive) for comprehensive validation [22].

Experimental Design for Validating RNA-Seq Findings with qPCR

Sample Considerations and Preanalytical Variables

The preanalytical phase introduces significant variability that can compromise reproducibility. Considerations for sample acquisition, processing, storage, and RNA purification are foundational to reliable validation [10]. Workflow performance for nucleic acid quantification varies significantly across targets, sample volumes, concentration methods, and extraction kits, necessitating careful validation for each specific application [23].

For RNA-Seq follow-up, the same RNA isolates used for sequencing should ideally be used for qPCR validation to eliminate variability from separate RNA preparations. When this is not possible, samples should be processed identically using standardized protocols. The availability of sufficient numbers of well-characterized samples is crucial; when genuine clinical samples are limited, spiking various concentrations of the analyte into a suitable matrix may be necessary, though such artificially constructed samples are unlikely to have the same properties as clinical samples [21].

Target Selection and Assay Design

Target selection should prioritize transcripts with sufficient expression levels for reliable qPCR quantification. The design of primers and probes is critical for method development and validation [20]. While design software can select primer and probe sets, it is generally advised to design and empirically test at least three primer and probe sets because performance predicted by in silico design may not always occur in actual use [20].

For validating RNA-Seq findings, the assay must specifically detect the transcript of interest. When detecting expressed transcripts, specificity for the vector-derived transcript could be conferred by targeting the junction of the transgene and neighboring vector component which would be expressed in the vector-derived transcript but not in the endogenous transcript [20]. This highlights the need to ensure that the developed assay can distinguish between vector-derived transcript and contaminating vector DNA, as well as endogenous transcript.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation of RNA-Seq Findings

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primer/Probe Sets | Sequence-specific amplification and detection | Design multiple candidates; verify specificity in silico and empirically [20] |

| Nucleic Acid Standards | Quantification standard curve | Should mimic sample amplicon; purified PCR product or synthetic oligonucleotides [24] [20] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA | Consistent enzyme and protocol critical for reproducibility [10] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides reaction components | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, buffers; choice affects efficiency [20] |

| Reference Genes | Normalization control | Should be stable across experimental conditions; multiple genes recommended [24] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring assay performance | Positive, negative, and inhibition controls [21] |

qPCR Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Detailed qPCR Validation Protocol

RNA Quality Assessment: Verify RNA integrity (RIN > 7) and purity (A260/280 ratio ~2.0) before proceeding with reverse transcription.

Reverse Transcription: Use consistent input RNA amounts (typically 100-500 ng) across all samples with a robust reverse transcription protocol. Include no-reverse transcriptase controls to detect genomic DNA contamination.

Assay Optimization: Test primer concentrations (typically 50-900 nM) in checkerboard fashion to determine optimal combination that provides the lowest Cq with highest amplification efficiency and specificity.

Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions (at least 5 points) of standard material covering the expected dynamic range. The standard curve material should be sequence-identical to the target and processed similarly to samples [24].

Reaction Setup: Perform reactions in technical replicates (at least duplicates, preferably triplicates) with appropriate negative controls (no-template controls).

Amplification Conditions: Follow optimized thermal cycling parameters with data acquisition at each cycle during the extension step.

Data Collection: Record Cq (quantification cycle) values for each reaction using consistent analysis parameters across the entire dataset.

qPCR Data Analysis Fundamentals

Accurate data analysis begins with proper baseline correction and threshold setting [24]. The baseline should be set using early cycles (e.g., cycles 5-15) that represent background fluorescence before amplification begins, while the threshold should be set in the exponential phase where amplification curves are parallel [24].

For quantification, the two primary approaches are:

- Standard Curve Quantitative Analysis: Cq values of unknown samples are compared to a standard curve with known concentrations [24].

- Relative/Comparative Quantitative Analysis (ΔΔCq method): Uses differences in Cq values between target and reference genes across samples to calculate fold changes [24].

Recent recommendations encourage moving beyond the 2−ΔΔCT method to more robust statistical approaches like ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance), which enhances statistical power and is less affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency [25]. Sharing raw qPCR fluorescence data with detailed analysis scripts improves transparency and reproducibility [25].

Clinical Translation: From Research to Diagnostic Applications

Clinical Research Assay Validation

The transition from Research Use Only (RUO) to In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) requires an intermediate step often referred to as a Clinical Research (CR) assay [10]. These are laboratory-developed tests that have undergone more thorough validation without reaching the status of a certified IVD assay, filling the gap between basic research and commercial diagnostics [10].

For molecular diagnostics like RNA sequencing, clinical validation involves establishing reference ranges for each gene and junction based on expression distributions from control data, then evaluating clinical performance using positive samples with previously identified diagnostic findings [22] [18]. This process typically establishes both analytical and clinical performance characteristics.

Clinical Validation of RNA-Seq-Based Tests

Recent advances in clinical RNA-Seq validation demonstrate approaches for diagnostic implementation. One validated clinical diagnostic RNA-Seq test for Mendelian disorders processes RNA samples from fibroblasts or blood and derives clinical interpretations based on analytical detection of outliers in gene expression and splicing patterns [22] [18]. The clinical validation of this test involved 130 samples (90 negative and 40 positive), with provisional benchmarks established using reference materials from the Genome in a Bottle Consortium [22].

The clinical performance measures—sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV)—become critical at this stage [10]. These metrics determine the real-world utility of the test and its impact on clinical decision-making. For molecular tests intended to support clinical trials, the validation must be sufficient to meet regulatory requirements, which continue to evolve for novel technologies [21] [20].

Robust validation is the cornerstone of reproducible research and successful clinical translation. The path from RNA-Seq discovery to clinically applicable findings requires rigorous analytical and clinical validation, with qPCR serving as a key bridging technology. By implementing comprehensive validation strategies that address preanalytical variables, analytical performance, and clinical utility, researchers can enhance the reproducibility of their findings and accelerate the translation of genomic discoveries into clinical applications that improve patient care.

The development of consensus guidelines and cross-industry standards for PCR assay validation represents significant progress in addressing the reproducibility crisis [10] [20]. As these standards continue to evolve and be adopted more widely, the scientific community can look forward to more efficient and reliable translation of RNA-Seq findings into clinically actionable insights.

From Data to Assay: A Step-by-Step Protocol for qPCR Validation

Candidate Gene Selection from RNA-Seq Analysis

The integration of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) has become the gold standard for comprehensive gene expression analysis in biomedical research. RNA-seq enables unbiased transcriptome profiling, while RT-qPCR provides sensitive, specific validation of key findings. However, the critical bridge between these technologies—appropriate candidate gene selection—is often overlooked, potentially compromising data interpretation and validation reliability. This technical guide outlines systematic approaches for selecting optimal reference and validation candidate genes from RNA-seq datasets, emphasizing rigorous statistical criteria and experimental design considerations. Within the broader context of qPCR validation best practices, proper gene selection ensures accurate biological interpretation, enhances reproducibility, and supports robust conclusions in drug development and basic research applications.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomic studies since its introduction in 2008, generating unprecedented volumes of gene expression data [26]. The fundamental goal of RNA-seq analysis is to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and infer biological meaning from these patterns. However, the complexity of RNA-seq data analysis presents significant challenges, including proper quality control, normalization, statistical testing, and interpretation [26]. Following statistical identification of DEGs, researchers typically employ RT-qPCR to validate key expression changes in specific genes of interest due to its superior sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility compared to sequencing approaches [14]. This validation step requires careful selection of both reference genes (for normalization) and target genes (for biological validation), a process that must be tailored to the specific biological context and experimental conditions. Inappropriate gene selection can introduce technical artifacts and lead to misinterpretation of biological phenomena, particularly when traditionally used housekeeping genes demonstrate unexpected variability under certain experimental conditions [14].

Table 1: Essential Components in RNA-seq to qPCR Validation Pipeline

| Component | Description | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Raw Data | FASTQ files from sequencing | Input for differential expression analysis |

| Alignment Reference | Organism-specific genome (e.g., mm10 for mouse) | Reference for mapping sequencing reads |

| Count Table | Matrix of reads mapped to each gene | Quantitative gene expression data |

| Metadata Sheet | Sample IDs, group assignments, covariates | Experimental design specification |

| Differential Expression Tool | edgeR, DESeq2, or limma | Statistical identification of DEGs |

| Reference Genes | Stable, highly expressed genes | RT-qPCR normalization |

| Validation Genes | Variable, biologically relevant genes | Target confirmation in RT-qPCR |

Methodological Framework for RNA-seq Analysis

Experimental Design and Quality Control

Proper experimental design is paramount for generating meaningful RNA-seq data. A well-controlled experiment minimizes batch effects—technical variations introduced during sample processing, RNA isolation, library preparation, or sequencing runs [26]. To mitigate these effects, researchers should process controls and experimental conditions simultaneously, maintain consistent protocols across users, and harvest samples at consistent times of day [26]. During the quality control phase, principal component analysis (PCA) provides a global overview of data structure, visualizing intergroup variability (differences between experimental conditions) versus intragroup variability (technical or biological variability among replicates) [26]. Ideally, intergroup variability should exceed intragroup variability to support robust differential expression detection. Sequencing reads must undergo quality checking using tools like FastQC, with adapter trimming performed using utilities such as Trimmomatic before alignment to the appropriate reference genome [27].

Differential Expression Analysis

Following quality control, RNA-seq analysis proceeds to differential expression testing. The process begins with raw count data, typically generated by alignment tools like STAR and quantification tools like HTSeq-count [27]. These raw counts should not be pre-normalized before differential expression analysis, as specialized tools like DESeq2 and edgeR incorporate normalization within their statistical frameworks [27]. These tools assume count data follows a negative binomial distribution and internally correct for library size differences using scaling factors [27]. The statistical testing phase employs generalized linear models to identify significantly differentially expressed genes, with multiple testing correction (typically using Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate) applied to account for the thousands of simultaneous comparisons being performed [27]. The result is a list of DEGs with associated statistics including log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values.

Figure 1: RNA-seq Analysis and Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps from raw data processing through candidate gene selection for validation.

Strategic Selection of Candidate Genes for Validation

Reference Gene Selection Criteria

Reference genes for RT-qPCR validation must demonstrate high and stable expression across all experimental conditions. Traditional selection of housekeeping genes (e.g., actin, GAPDH) based solely on their biological functions is insufficient, as these genes may exhibit variability under different biological conditions [14]. The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software implements a systematic filtering-based methodology using Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values to identify optimal reference candidates [14]. This approach applies five sequential filters to identify genes with appropriate characteristics for reliable normalization:

- Expression Presence: TPM > 0 across all samples

- Low Variability: Standard deviation of log2(TPM) < 1

- Consistent Expression: No outlier expression (|log2(TPMi) - mean(log2TPM)| < 2)

- High Expression: Mean log2(TPM) > 5

- Low Coefficient of Variation: CV < 0.2

These criteria collectively ensure selected reference genes are stably expressed at levels readily detectable by RT-qPCR, minimizing technical variation during validation experiments [14].

Table 2: Reference Gene Selection Criteria and Interpretation

| Criterion | Mathematical Representation | Biological/Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitous Expression | (TPMᵢ)ᵢ₌ₐⁿ > 0 | Ensures gene is expressed in all experimental conditions |

| Low Variability | σ(log₂(TPMᵢ)ᵢ₌ₐⁿ) < 1 | Filters genes with minimal expression fluctuations |

| Expression Consistency | |log₂(TPMᵢ) - log₂TPM| < 2 | Eliminates genes with outlier expression in any sample |

| High Expression Level | log₂TPM > 5 | Ensures expression above RT-qPCR detection limits |

| Stable Expression | CV = σ(log₂(TPMᵢ))/log₂TPM < 0.2 | Selects genes with minimal relative variation |

Validation Gene Selection Criteria

For target genes selected to confirm biological findings, different selection criteria apply. These genes should exhibit significant differential expression while remaining within detectable limits for RT-qPCR. The GSV software applies three fundamental criteria for identifying suitable validation candidates [14]:

- Expression Presence: TPM > 0 across all samples

- High Variability: Standard deviation of log2(TPM) > 1

- Adequate Expression: Mean log2(TPM) > 5

These filters ensure selected validation genes show meaningful expression differences between conditions while maintaining sufficient expression levels for reliable RT-qPCR detection. This approach prevents selection of genes with low expression that might produce inconsistent validation results due to technical limitations of the RT-qPCR assay [14].

Experimental Protocols for qPCR Validation

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Following candidate gene selection, RNA isolation must be performed using standardized protocols to maintain RNA integrity. Samples with high-quality RNA (RNA integrity number > 7.0) should be selected for downstream processing [26]. For cDNA synthesis, total RNA samples (0.5μg) are reverse-transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and reverse transcriptase (e.g., Superscript II) in a total volume of 10μL [28]. The typical thermal cycling program consists of 42°C for 60 minutes followed by 70°C for 15 minutes to inactivate the enzyme. The resulting cDNA samples are then diluted to 25μL and stored at -20°C until qPCR analysis [28].

Quantitative PCR Setup and Analysis

Quantitative PCR is performed using talent qPCR Premix (SYBR Green) kits following manufacturer instructions [28]. Each 20μL reaction contains 10μL of 2× PreMix, 0.6μL each of forward and reverse primers (10μM), 8.7μL of RNase-free ddH₂O, and 0.7μL of cDNA template [28]. Primer design represents a critical factor in successful validation; primers should be designed to have melting temperatures of 57-63°C (optimized to 60°C) with product sizes of 90-180 base pairs [28]. The PCR cycling program typically includes an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 5 seconds at 95°C and 15 seconds at 60°C [28]. Melting curve analysis should be performed after amplification to verify primer specificity, with only primers producing single peaks selected for validation experiments. For data analysis, the delta-delta Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method is commonly employed, with PCR efficiency calculations based on standard curves of serial cDNA dilutions [28].

Figure 2: qPCR Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in the qPCR validation process from RNA isolation through data analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kit | Extract high-quality RNA from samples | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (maintains RIN > 7.0) |

| Poly(A) Selection Kit | Enrich for mRNA from total RNA | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | Reverse transcribe RNA to cDNA | Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase with oligo(dT) |

| qPCR Master Mix | Enable quantitative PCR detection | Talent qPCR Premix (SYBR Green) |

| Alignment Software | Map reads to reference genome | STAR, TopHat2 with organism-specific reference |

| Differential Expression Tools | Identify statistically significant DEGs | edgeR, DESeq2, limma (R/Bioconductor packages) |

| Gene Selection Software | Identify optimal reference/validation genes | GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) software |

Effective candidate gene selection from RNA-seq data represents a critical methodological bridge between high-throughput transcriptomic discovery and targeted validation. By implementing systematic approaches for selecting both reference and target validation genes, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and biological relevance of their expression studies. The integration of rigorous statistical criteria with practical experimental considerations ensures that qPCR validation accurately reflects biological phenomena rather than technical artifacts. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and applications expand across basic research and drug development, robust validation frameworks will remain essential for translating transcriptomic discoveries into meaningful biological insights and therapeutic advancements.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technique for validating gene expression findings from high-throughput RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq). While RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, qPCR offers unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative precision for confirming key results [29]. This technical guide outlines core principles for designing robust qPCR assays—focusing on primers, probes, and amplicon considerations—within the context of a rigorous RNA-Seq validation workflow. Proper assay design is paramount for generating reproducible, reliable data that can withstand scientific scrutiny and support critical conclusions in drug development and basic research.

Core Principles of Primer Design

PCR primers are the foundation of any successful qPCR assay. Their binding characteristics directly influence amplification efficiency, specificity, and overall quantification accuracy [30].

Key Design Parameters

Table 1: PCR Primer Design Guidelines

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Ideal Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-30 bases | 20-24 bases | Balances specificity and binding efficiency [30] [31]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 59-64°C | ~60°C | Must be compatible with enzyme function and cycling conditions [30] [31]. |

| Primer Pair Tm Difference | ≤ 2°C | Identical | Ensures both primers bind simultaneously and efficiently [30]. |

| GC Content | 40-60% | 50% | Provides sequence complexity while avoiding stable secondary structures [30] [31]. |

| 3' End Stability | Avoid 3' secondary structures | - | Prevents mispriming and ensures correct initiation [31]. |

Avoiding Secondary Structures and Dimers

Primer sequences must be analyzed for self-complementarity and potential interactions with the partner primer:

- Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers: The ΔG value of any predicted dimer should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [30].

- Hairpins: Avoid stable hairpin structures, particularly at the 3' end, as they can severely impede polymerase binding and extension [31].

- Repetitive Sequences: Avoid runs of four or more identical consecutive nucleotides, as they can promote slippage and mispriming [31].

Free online tools, such as the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool, can automatically screen for these problematic interactions [30].

Hydrolysis Probe Design for qPCR

Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) provide an additional layer of specificity by requiring hybridization to the target sequence between the primer binding sites. This significantly reduces false-positive signals from non-specific amplification or primer-dimer artifacts [30].

Design Criteria

Table 2: qPCR Hydrolysis Probe Design Guidelines

| Parameter | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Close to, but not overlapping, a primer-binding site. Can be on either strand. | Ensures probe binds to the same amplicon without interfering with primer extension [30]. |

| Length | 20-30 bases (for single-quenched probes) | Achieves a suitable Tm without compromising fluorescence quenching [30]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 5-10°C higher than primers | Ensures the probe is fully bound when primers anneal, providing accurate quantification [30] [32]. |

| GC Content | 35-65% | Similar to primers, avoids secondary structures [30]. |

| 5' End | Avoid a Guanine (G) base | Prevents quenching of the 5' fluorophore reporter dye [30]. |

Advanced Probe Technologies

Double-quenched probes are highly recommended over single-quenched probes. They incorporate an internal quencher (e.g., ZEN or TAO) in addition to the 3' quencher, which results in consistently lower background fluorescence and a higher signal-to-noise ratio. This is particularly beneficial for longer probes [30].

Amplicon and Target Sequence Selection

The region of the genome to be amplified—the amplicon—must be carefully selected to ensure specific detection of the intended target, which is especially critical when validating RNA-Seq data.

Amplicon Characteristics

- Length: For qPCR, ideal amplicon length is 75-200 base pairs. Smaller amplicons are amplified more efficiently, leading to more accurate and robust quantification [31].

- Sequence Evaluation: The target sequence should be checked for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as a single mismatch can reduce the primer Tm by up to 10°C and drastically lower PCR efficiency [31]. Tools like NCBI BLAST should be used to confirm primer uniqueness [30].

- Secondary Structure: Use tools like mFold or the IDT UNAFold Tool to predict template secondary structure at the primer annealing temperature. Select target regions that are predicted to be in an "open" configuration to facilitate primer and probe binding [31] [30].

Specificity for RNA Targets: Avoiding Genomic DNA

A primary concern when validating RNA-Seq data is ensuring that the qPCR assay is specific to the cDNA target and does not co-amplify contaminating genomic DNA (gDNA).

- DNase Treatment: A best practice is to treat RNA samples with RNase-free DNase I prior to reverse transcription to remove residual gDNA [30].

- Amplicon Location: Design assays to span an exon-exon junction. Because introns are spliced out in mature mRNA, this design will prevent amplification from gDNA, which contains introns [30] [31]. Whenever possible, target a junction with a long intron (several kilobases) to make gDNA amplification even less likely under standard cycling conditions [31].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps and decision points in designing a qPCR assay for RNA-Seq validation.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Calculating PCR Efficiency

PCR efficiency must be calculated for every assay to ensure accurate relative quantification. Efficiency between 90-110% is generally acceptable, with 100% representing ideal doubling every cycle [33].

Protocol:

- Prepare a standard curve using a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) of a known amount of template cDNA [33].

- Run the qPCR assay for all dilution points, including at least three technical replicates per point.

- Plot the average Ct value for each dilution against the log10 of the dilution factor.

- Perform linear regression to obtain the slope of the trendline.

- Calculate the efficiency using the formula: Efficiency (%) = (10(-1/slope) - 1) × 100 [33].

Data Analysis and the Pitfalls of 2–ΔΔCT

While the 2–ΔΔCT method is widely used for relative quantification, it relies on the critical assumption that all assays have perfect and equal amplification efficiencies. Violations of this assumption can lead to significant inaccuracies [25].

Superior Statistical Approach:

- ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance): This linear modeling approach, applied to raw fluorescence data, offers greater statistical power and robustness because it directly accounts for variability in amplification efficiency between assays. Sharing raw fluorescence data and analysis code (e.g., in R) promotes reproducibility and adherence to FAIR data principles [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for qPCR Assay Design and Validation

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Design Tools | IDT SciTools (PrimerQuest, OligoAnalyzer) [30] | Designs primers/probes and analyzes parameters like Tm, dimers, and hairpins. |

| Eurofins Genomics qPCR Assay Design Tool [32] | Selects optimal primer/probe combinations based on customizable constraints. | |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | DNase I (RNase-free) [30] | Degrades contaminating genomic DNA in RNA samples prior to reverse transcription. |

| Double-Quenched Probes [30] | Provide lower background and higher signal-to-noise ratio compared to single-quenched probes. | |

| Validation Software | Standard Curve Analysis Software (e.g., in R) [33] [25] | Calculates PCR amplification efficiency from serial dilution data. |

| Statistical Platforms (R, with ANCOVA models) [25] | Provides robust differential expression analysis that accounts for efficiency variations. |

In the pipeline of molecular research, particularly in the validation of RNA-Seq findings, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the benchmark for confirming gene expression levels. The reliability of this confirmation, however, is entirely dependent on the rigorous validation of the qPCR assay itself. Within a regulated bioanalytical environment, such as that supporting preclinical and clinical studies for gene and cell therapies, establishing key performance parameters is not just best practice—it is a necessity for generating GxP-compliant, trustworthy data [4] [34]. This guide details the core principles of three foundational pillars of qPCR validation: inclusivity, exclusivity, and linear dynamic range. Without a properly validated assay, researchers risk investing in drug candidates that seem promising based on erroneous data or, in a clinical setting, misinterpreting transcriptional biomarkers for patient diagnostics [3]. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide a framework for this process, aiming to ensure the integrity of the scientific literature and promote consistency between laboratories [3] [35].

Defining the Core Parameters

Inclusivity

Inclusivity measures the assay's ability to detect all intended target variants or strains with high reliability [3]. In the context of validating RNA-Seq results, the "target" is often a specific transcript sequence. Genetic diversity, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or splice variants identified in sequencing data, can prevent primer or probe binding, leading to false negative results.

- Practical Implication: An assay with poor inclusivity will fail to detect some isoforms of the target transcript, leading to an underestimation of gene expression levels and a failure to accurately corroborate the RNA-Seq findings.

Exclusivity (Cross-Reactivity)

Exclusivity, also referred to as cross-reactivity, assesses the assay's ability to avoid detection of genetically similar non-targets [3]. These non-targets can include homologous genes, pseudogenes, or transcripts from closely related family members.

- Practical Implication: An assay with poor exclusivity will generate false positive signals by amplifying non-target sequences, leading to an overestimation of the true expression level of the gene of interest. This can mislead the interpretation of a drug's mechanism of action or a disease biomarker's significance.

Linear Dynamic Range