From Spectra to Signatures: A Modern Pipeline for Biomarker Discovery in Proteomic Mass Spectrometry

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the end-to-end pipeline for identifying and validating protein biomarkers using mass spectrometry.

From Spectra to Signatures: A Modern Pipeline for Biomarker Discovery in Proteomic Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the end-to-end pipeline for identifying and validating protein biomarkers using mass spectrometry. Covering the journey from foundational concepts and experimental design to advanced data acquisition, troubleshooting, and rigorous validation, it synthesizes current best practices and technological innovations. Readers will gain a practical framework for designing robust discovery studies, overcoming common analytical challenges, and translating proteomic findings into clinically actionable biomarkers, with insights drawn from recent advancements and comparative platform analyses.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles and Design for Robust Biomarker Discovery

In the realm of modern molecular medicine and proteomic research, biomarkers are indispensable tools for bridging the gap between benchtop discovery and clinical application. The Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource, a joint initiative by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), defines a biomarker as "a defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention" [1]. Within the pipeline for identifying biomarkers from proteomic mass spectrometry data, a critical first step is the precise classification of these biomarkers based on their clinical application. This classification directly influences study design, analytical validation, and ultimate clinical utility [1] [2]. This article delineates the three foundational classifications—diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive—providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in mass spectrometry-based biomarker discovery.

Biomarker Classification and Clinical Applications

Biomarkers are categorized by their specific clinical function, which dictates their role in patient management and therapeutic development. The table below summarizes the core definitions and applications of diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers.

Table 1: Classification and Application of Key Biomarker Types

| Biomarker Type | Primary Function | Clinical Context of Use | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Detects or confirms the presence of a disease or a specific disease subtype [1] [3]. | Symptomatic individuals; aims to identify the disease and classify its subtype for initial management [1]. | Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer [4], C-reactive protein (CRP) for inflammation [5], Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) for traumatic brain injury [3]. |

| Prognostic | Provides information about the likely natural history of a disease, including risk of recurrence or mortality, independent of therapeutic intervention [3] [5]. | Already diagnosed individuals; informs on disease aggressiveness and overall patient outcome, guiding long-term monitoring and care intensity [3]. | Ki-67 (MKI67) protein for cell proliferation in cancers [5], Mutated PIK3CA in metastatic breast cancer [3]. |

| Predictive | Identifies the likelihood of a patient responding to a specific therapeutic intervention, either positively or negatively [1] [5]. | Prior to treatment initiation; enables therapy selection for individual patients, forming the basis of personalized medicine [1]. | HER2/neu status for trastuzumab response in breast cancer [3] [5], EGFR mutation status for tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer [3] [5]. |

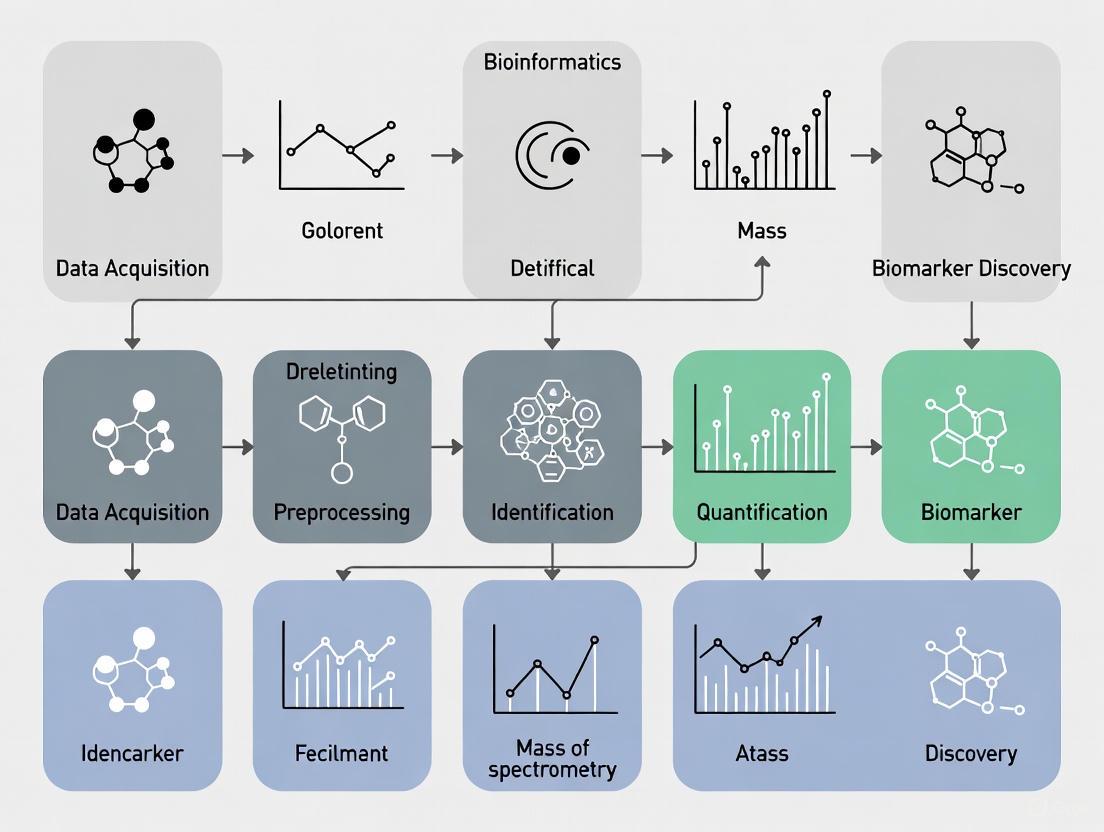

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these biomarker types and their specific roles in the patient journey.

Integrated Mass Spectrometry Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

The discovery and validation of protein biomarkers using mass spectrometry (MS) require a rigorous, multi-stage pipeline. This process transitions from broad, untargeted discovery to highly specific and validated assays, ensuring that only the most robust candidates advance [6] [2]. The pipeline is characterized by an inverse relationship between the number of proteins quantified and the number of patient samples analyzed, with different MS techniques being optimal for each phase [6].

Stages of the Biomarker Pipeline

- Biomarker Discovery: This initial phase utilizes non-targeted, "shotgun" proteomics to relatively quantify thousands of proteins across a small number of samples (e.g., 10-20 per group) [6] [7]. Techniques like data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry or isobaric labeling (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) are commonly employed to identify proteins that are differentially expressed between diseased and healthy cohorts [6] [8]. The output is a list of hundreds of candidate proteins with associated fold-changes.

- Biomarker Verification: The long list of candidates from the discovery phase is filtered down using higher-specificity mass spectrometry, often targeted methods like Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) or SRM [6]. This step verifies the differential expression of a smaller panel of proteins (tens to hundreds) in a larger, independent set of patient samples (typically 50-100) [6] [2].

- Biomarker Validation: This critical final preclinical phase involves the absolute quantitation of a small number of lead biomarker candidates (fewer than 10) in a large, well-defined clinical cohort (100-500+ samples) [6] [2]. The goal is to rigorously assess the clinical sensitivity, specificity, and predictive power of the biomarker(s) using analytically validated assays, which may still be MS-based or transition to immunoassays [6] [8].

Protocol: Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) for Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To identify differentially expressed protein biomarkers between case and control groups from plasma/serum samples using a discovery proteomics approach.

Materials:

- Biological Samples: Matched case and control cohorts (e.g., n=492 total for sufficient statistical power) [8].

- Sample Preparation: Equipment for protein digestion (e.g., trypsin), desalting columns (e.g., C18 STAGE tips), and detergent removal.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) instrument coupled to a nano-flow liquid chromatography system [8].

- Data Analysis Software: Tools for DIA data analysis (e.g., Spectronaut, DIA-NN, Skyline) and statistical analysis (e.g., R, Python).

Method Details:

- Sample Preparation and Randomization:

- Deplete high-abundance plasma proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) to enhance depth of coverage.

- Perform reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion of proteins according to standardized protocols [2] [8].

- Desalt and purify peptides.

- Critical Step: Randomize the order of sample analysis by LC-MS/MS to prevent batch effects from confounding biological differences [2].

LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition:

- Separate peptides using a reversed-phase nano-LC gradient.

- Acquire DIA-MS data on the HRAM mass spectrometer. In DIA mode, the instrument fragments all ions within sequential, pre-defined m/z isolation windows, covering the entire mass range of interest [8].

Data Processing and Protein Quantification:

- Process the raw DIA data using specialized software (e.g., TEAQ - Targeted Extraction Assessment of Quantification) to extract peptide precursor signals and quantify proteins [8].

- The software should assess analytical quality criteria, including:

- Linearity: Correlation between peptide abundance and sample load.

- Specificity: Uniqueness of the peptide signal to a single protein.

- Repeatability/Reproducibility: Low coefficient of variation across technical replicates [8].

Statistical Analysis and Biomarker Candidate Selection:

- Normalize protein abundance data across all samples.

- Perform statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) adjusted for multiple comparisons (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to identify proteins significantly differentially expressed between case and control groups.

- Apply feature selection algorithms or machine learning models (e.g., logistic regression, random forest) to identify a panel of biomarker candidates with the highest classification power [9].

Expected Outcomes: A list of verified peptide precursors and their parent proteins that are significantly altered in the disease cohort and meet pre-defined analytical quality metrics, ready for downstream validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials required for a mass spectrometry-based biomarker discovery and validation pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MS-Based Biomarker Pipeline

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Proteolytic enzyme for specific digestion of proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis [6]. |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Tips | Desalting and purification of peptide mixtures after digestion and prior to LC-MS injection [2]. |

| Isobaric Tagging Reagents (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) | Chemical labels for multiplexed relative protein quantitation across multiple samples in a single MS run [6]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Peptide Standards (SIS) | Synthetic peptides with heavy isotopes for absolute, precise quantitation of target proteins in validation assays (e.g., MRM) [6]. |

| High-Abundancy Protein Depletion Columns | Immunoaffinity columns for removing highly abundant proteins (e.g., albumin) from plasma/serum to improve detection of low-abundance biomarkers [8]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Sample | A representative pool of all samples analyzed repeatedly throughout the MS sequence to monitor instrument performance and data quality [2]. |

The precise classification of biomarkers into diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive categories is a foundational element that directs the entire proteomic research pipeline. From initial experimental design to final clinical application, understanding the distinct clinical question each biomarker type addresses is paramount for developing meaningful and impactful tools. The structured workflow from MS-based discovery through rigorous verification and validation, supported by the appropriate toolkit of reagents and protocols, provides a robust pathway for translating proteomic data into clinically actionable biomarkers. This systematic approach ultimately empowers the development of personalized medicine, enabling more accurate diagnoses, informed prognosis, and effective, tailored therapies.

The Critical Role of Experimental Design and Cohort Selection

The journey from a mass spectrometry (MS) run to a clinically validated biomarker is fraught with potential for failure. Often, the root cause of such failures is not the analytical technology itself, but fundamental flaws in the initial planning of the study. Rigorous experimental design and meticulous cohort selection are the most critical, yet frequently underappreciated, components of a successful biomarker discovery pipeline [10] [11]. These initial steps form the foundation upon which all subsequent data generation, analysis, and validation are built; a weak foundation inevitably leads to unreliable and non-reproducible results. This document outlines detailed protocols and application notes to guide researchers in designing robust and statistically sound proteomic studies, thereby enhancing the rigor and credibility of biomarker development [10].

Principles of Cohort Selection

The selection of study subjects is a cornerstone of biomarker research, as an ill-defined cohort can introduce bias and confound results, dooming a project from the start.

Defining Cases and Controls

The clarity and precision with which case and control groups are defined directly impact the specificity and generalizability of the discovered biomarkers [10].

- Cases: Patient groups should be defined using established diagnostic criteria. This includes clear clinical characteristics, standardized laboratory test results, and well-defined disease stages. The stringency of these criteria involves a trade-off between cohort purity and the eventual clinical applicability of the biomarker.

- Controls: Control subjects must be carefully matched to cases to minimize the influence of confounding variables. As outlined in Table 1, control groups can range from healthy individuals to patients with other diseases that share symptomatic similarities. The most robust studies often include multiple control groups to distinguish disease-specific biomarkers from general indicators of inflammation or other physiological states [10].

Managing Bias and Confounding Factors

Observational studies are particularly susceptible to biases that can skew results [10].

- Selection Bias: This occurs when the study subjects are not representative of the target population. To mitigate this, recruitment strategies should be based on well-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria applied equally to all participants. The use of consecutive recruitment from clinical pathways is a recommended practice [10].

- Confounding Factors: These are variables that are associated with both the exposure and the outcome. Common confounders in clinical proteomics include age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities. Statistical methods like inverse probability weighting and post-stratification can be employed to adjust for these factors during data analysis [10].

Table 1: Types of Control Groups in Biomarker Studies

| Control Type | Description | Key Utility | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls | Individuals with no known history of the disease. | Establishes a baseline "normal" proteomic profile. | May not account for proteins altered due to non-specific factors (e.g., stress, minor inflammation). |

| Disease Controls | Patients with a different disease, often with symptomatic overlap. | Helps identify biomarkers specific to the disease of interest rather than general illness. | Crucial for verifying specificity and reducing false positives. |

| Pre-clinical/Longitudinal Controls | Individuals who later develop the disease, identified from longitudinal cohorts. | Allows discovery of early detection biomarkers before clinical symptoms manifest. | Requires access to well-annotated, prospective biobanks. |

Experimental Design and Statistical Considerations

A powerful and well-controlled experimental design is essential for detecting true biological signals amidst technical noise.

Power and Sample Size

A critical early step is the calculation of statistical power to determine the necessary sample size. Underpowered studies are a major contributor to irreproducible research, as they lack the sensitivity to detect anything but very large effect sizes [10]. Sample size should be estimated based on the expected fold-change in protein abundance and the biological variability within the groups. Tools for power analysis in proteomics are available and must be utilized during the planning phase to ensure the study is capable of answering its central hypothesis [10].

Randomization, Blinding, and Replication

Incorporating these elements is non-negotiable for ensuring the integrity of the data [10] [11].

- Randomization: The assignment of samples to processing batches and MS run orders must be randomized. This prevents technical artifacts (e.g., instrument drift, reagent batch effects) from being systematically correlated with biological groups.

- Blinding: Technicians and analysts should be blinded to the group identity of the samples (e.g., case vs. control) during sample processing, data acquisition, and initial data processing to prevent unconscious bias.

- Replication: Both technical and biological replicates are essential.

- Technical Replicates: Multiple injections of the same sample assess instrumental precision.

- Biological Replicates: Multiple individuals per group account for natural biological variation and are required for robust statistical inference.

The following workflow diagram integrates the key components of cohort selection and experimental design into a coherent pipeline.

Quality Control and Data Acquisition

Robust quality control (QC) measures are implemented throughout the process to ensure data reliability [10] [11].

- Sample Preparation QC: Protein concentration should be measured using a standardized assay (e.g., BCA assay) before digestion. A common best practice is to include a "QC pool" sample, created by combining a small aliquot of every sample in the study. This QC pool is then analyzed repeatedly throughout the MS acquisition sequence to monitor technical performance.

- Mass Spectrometry QC: The instrument performance should be evaluated using complex standard digests (e.g., HeLa cell digest) to ensure sensitivity and stability over time. Monitoring metrics like peptide identification rates, retention time stability, and intensity distribution is crucial.

An Integrated Pipeline for Biomarker Translation

The ultimate goal of discovery is translation into a clinically usable assay. The pipeline must therefore be designed with validation in mind from the outset.

From Discovery to Targeted Assays

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA-MS) has emerged as a powerful discovery strategy because it combines deep proteome coverage with high reproducibility [8]. The data generated can be directly mined to transition into targeted mass spectrometry assays (e.g., SRM/PRM), which are the standard for precise biomarker verification and validation. Software tools like the Targeted Extraction Assessment of Quantification (TEAQ) have been developed to automatically select the most reliable peptide precursors from DIA-MS data based on analytical criteria such as linearity, specificity, and reproducibility, thereby streamlining the development of targeted assays [8].

Integration of Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) models are increasingly used to identify complex patterns in high-dimensional proteomic data [12] [9]. A typical ML pipeline for biomarker discovery, as applied in areas like prostate cancer research, involves:

- Feature Selection: Reducing the thousands of detected proteins to a panel of the most informative biomarkers using statistical methods or ML-based feature importance [9].

- Model Training: Training multiple classifiers (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) on the selected features to distinguish between patient groups [9].

- Model Ensembling: Combining predictions from multiple models through a voting mechanism to improve overall classification accuracy and robustness [9]. Such pipelines have demonstrated success in identifying novel peptide panels with high predictive performance for disease classification [9].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Proteomic Workflows

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Trypsin/Lys-C protease, RapiGest SF, Dithiothreitol (DTT), Iodoacetamide (IAA), C18 solid-phase extraction plates | Protein digestion, disulfide bond reduction, alkylation, and peptide desalting/purification. |

| Chromatography | LC-MS grade water/acetonitrile, Formic Acid, C18 reversed-phase UHPLC columns | Peptide separation prior to MS injection to reduce complexity and enhance identification. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Mass calibration solution (e.g., ESI Tuning Mix), Quality control reference digest (e.g., HeLa digest) | Instrument calibration and performance monitoring to ensure data quality and reproducibility. |

| Data Analysis | Protein sequence databases (e.g., Swiss-Prot), Software platforms (e.g., MaxQuant, Spectronaut, TEAQ), Standard statistical packages (R, Python) | Protein identification, quantification, and downstream bioinformatic analysis for biomarker candidate selection. |

The following diagram illustrates the informatics pipeline that integrates machine learning for biomarker signature identification.

The path to a clinically useful biomarker is long and complex, but its success is largely determined at the very beginning. A deliberate and rigorous approach to cohort selection and experimental design is not merely a procedural formality but the fundamental engine of discovery. By adhering to the principles outlined in this protocol—careful subject matching, power analysis, randomization, blinding, and planning for validation—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and translational potential of their proteomic biomarker studies.

In the proteomic mass spectrometry pipeline for biomarker discovery, the choice of biological sample is a foundational decision that profoundly influences the success and clinical relevance of the research. Blood-derived samples (plasma and serum) and proximal fluids represent two complementary approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific clinical questions. Plasma and serum provide a systemic overview of an organism's physiological and pathological state, making them ideal for detecting widespread diseases and monitoring therapeutic responses. In contrast, proximal fluids—bodily fluids in close contact with specific organs or tissue compartments—offer a concentrated source of tissue-derived proteins that often reflect local pathophysiology with greater specificity [13] [14].

The biomarker development pipeline necessitates different sample strategies across its phases. Discovery phases often benefit from the enriched signal in proximal fluids, while validation and clinical implementation typically require the accessibility and systemic perspective of blood samples [6]. This application note examines the advantages, limitations, and appropriate contexts for using these sample types, providing structured comparisons and detailed protocols to inform researchers' experimental designs within the broader biomarker identification pipeline.

Comparative Analysis of Sample Types

Fundamental Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Applications of Major Sample Types

| Sample Type | Definition & Composition | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Liquid component of blood containing fibrinogen and other clotting factors; obtained via anticoagulants [15]. | - Represents systemic circulation- Good stability of analytes- Enables repeated sampling- Standardized collection protocols | - High dynamic range of protein concentration (~1010)- High abundance of proteins (e.g., albumin) can mask low-abundance biomarkers [13] | - Systemic disease monitoring- Drug pharmacokinetic studies- Cardiovascular and metabolic disorders |

| Serum | Liquid fraction remaining after blood coagulation; fibrinogen and clotting factors largely removed [15]. | - Lacks anticoagulant additives- Clotting process removes some high-abundance proteins- Well-established historical data | - Potential loss of protein biomarkers during clotting- Variable composition due to clotting time/temperature | - Oncology biomarkers (e.g., CA-125, CA19-9) [6]- Historical cohort studies- Autoimmune disease profiling |

| Proximal Fluids | Fluids derived from extracellular milieu of specific tissues (e.g., CSF, synovial fluid, nipple aspirate) [13]. | - Enriched with tissue-derived proteins- Higher relative concentration of disease-related proteins vs. plasma/serum [13]- Reduced complexity and dynamic range | - Often more invasive collection procedures- Lower total volume typically obtained- Potential blood contamination issues [14] | - Central nervous system disorders (CSF) [14] [16]- Breast cancer (nipple aspirate) [17]- Joint diseases (synovial fluid) |

Quantitative Proteomic Depth Across Sample Types

The capability to identify proteins from different sample sources varies significantly based on their complexity and the methodologies employed.

Table 2: Typical Proteomic Depth Achievable Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Typical Protein Identifications | Key Methodological Considerations | Reported Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | 2,615 proteins from 6 individual samples using SCX fractionation and LC-MS/MS [14] | - Often requires minimal depletion due to lower albumin content- Fractionation significantly increases proteome coverage | 78 brain-specific proteins identified using Human Protein Atlas database mining [14] |

| Plasma/Serum | 1,179 proteins identified; 326 quantifiable proteins from a cohort of 492 IBD patients using DIA-MS [8] | - Requires high-abundance protein depletion (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins)- Advanced fractionation and high-resolution MS essential for depth | 8-protein panel for Parkinson's disease prediction validated in plasma [18] |

| Cell Line Media (Proximal Fluid Surrogate) | 249 proteins detected from 7 breast cancer cell lines [17] | - Controlled environment reduces complexity- Enables study of specific cellular phenotypes without in vivo complexity | Predictive categorization of HER2 status using two proteins [17] |

Advantages of Proximal Fluids in Biomarker Discovery

Biological Rationale and Technical Advantages

Proximal fluids offer distinct advantages for biomarker discovery, particularly in the early stages of the pipeline:

Enhanced Biological Relevance: Proximal fluids reside in direct contact with their tissues of origin, creating a dynamic exchange where shed and secreted proteins from the tissue microenvironment accumulate. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), for instance, communicates closely with brain tissue and contains numerous brain-derived proteins, with approximately 20% of its total protein content secreted by the central nervous system [14]. This proximity means that disease-related proteins are often present at higher concentrations relative to their diluted counterparts in systemic circulation [13].

Reduced Complexity: The dynamic range of protein concentrations in plasma and serum spans approximately ten orders of magnitude, creating significant analytical challenges for detecting low-abundance, disease-relevant proteins [13]. Proximal fluids like CSF have a less complex proteome with a narrower dynamic range, facilitating the detection of potentially significant biomarkers that would be masked in blood samples.

Tissue-Specific Protein Enrichment: Proximal fluids are enriched for tissue-specific proteins. For example, the CSF proteome is characterized by a high fraction of membrane-bound and secreted proteins, which are overrepresented compared to blood and represent respectable biomarker candidates [14]. Mining of the Human Protein Atlas database against experimental CSF proteome data has identified 78 brain-specific proteins, creating a valuable signature for CNS disease diagnostics [14].

Practical Workflow: CSF Proteomic Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a highly automated, scalable pipeline for CSF proteome analysis, designed for biomarker discovery in central nervous system disorders.

Diagram 1: Automated CSF proteomics workflow for biomarker discovery. This scalable pipeline enables large-scale clinical studies while maintaining comprehensive proteome coverage. Sample preparation begins with clearance centrifugation and proceeds through standard proteolytic processing before strong cation exchange (SCX) fractionation and high-resolution LC-MS/MS analysis [14] [16].

Detailed Protocol: CSF Proteome Preparation for Biomarker Discovery

Protocol Objective: To prepare cerebrospinal fluid samples for comprehensive proteomic analysis using fractionation and LC-MS/MS, enabling identification of brain-enriched proteins.

Materials & Reagents:

- Clear, non-hemolyzed CSF samples (stored at -80°C)

- RapiGest SF Surfactant (Waters)

- Dithiothreitol (DTT)

- Iodoacetamide (IAA)

- Sequencing-grade modified trypsin

- Ammonium bicarbonate

- Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

- Formic acid

- Acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

- Strong cation exchange (SCX) PolySULFOETHYL Column

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw CSF samples at room temperature and centrifuge at 17,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble material or cells [14].

- Protein Denaturation & Reduction: Adjust CSF volume equivalent to 300 µg total protein. Add RapiGest to 0.05% final concentration and DTT to 5 mM final concentration. Incubate at 60°C for 40 minutes [14].

- Alkylation: Add iodoacetamide to 15 mM final concentration. Incubate for 60 minutes in the dark at room temperature [14].

- Trypsin Digestion: Add trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (1:30 trypsin-to-protein ratio). Incubate for 18 hours at 37°C [14].

- Digestion Termination: Add trifluoroacetic acid to 1% final concentration to stop digestion and cleave RapiGest. Centrifuge at 500 × g for 30 minutes to remove insoluble debris [14].

- Peptide Fractionation: Dilute trypsinized samples two-fold with SCX Buffer A (0.26 M formic acid, 5% acetonitrile). Load onto SCX column and elute with a gradient of SCX Buffer B (0.26 M formic acid, 5% acetonitrile, 1 M ammonium formate) over 70 minutes. Collect 15-16 fractions per sample based on UV monitoring at 280 nm [14].

- Desalting: Purify peptides from each fraction using C18 solid-phase extraction tips. Elute with 65% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, and dilute to 0.01% formic acid for MS analysis [14].

Quality Control Notes:

- Monitor sample clarity before processing; discard samples with visible blood contamination.

- Include a pooled quality control sample across runs to monitor technical variability.

- Expected protein identification range: 1,100-1,400 proteins per individual CSF sample with 21% inter-individual variability [14].

Advantages of Plasma and Serum in Biomarker Validation and Clinical Translation

Strategic Value in the Biomarker Pipeline

While proximal fluids excel in discovery phases, plasma and serum offer complementary strengths that make them indispensable for validation and clinical implementation:

Clinical Practicality: Blood collection is minimally invasive, standardized, and integrated into routine clinical practice worldwide. This enables large-scale cohort studies, repeated sampling for longitudinal monitoring, and eventual translation into clinical diagnostics. The recent development of high-throughput targeted mass spectrometry assays has further enhanced the utility of plasma for large validation studies [8] [18].

Systemic Perspective: Plasma and serum provide a comprehensive view of systemic physiology, capturing signaling molecules, tissue leakage proteins, and immune mediators from throughout the body. This systemic perspective is particularly valuable for multifocal diseases, metastatic cancers, and systemic inflammatory conditions.

Established Infrastructure: Well-characterized protocols for sample collection, processing, and storage exist for plasma and serum, along with established quality control measures and commercial reference materials (e.g., NIST SRM 1950) [15]. This infrastructure supports reproducible and comparable results across laboratories and studies.

Advanced Workflow: Plasma Biomarker Verification Pipeline

The following diagram outlines a targeted proteomics pipeline for verification of biomarker candidates discovered in plasma, bridging the gap between discovery and clinical validation.

Diagram 2: Plasma biomarker verification pipeline using TEAQ. The Targeted Extraction Assessment of Quantification (TEAQ) software bridges discovery and validation by selecting precursors, peptides, and proteins from DIA-MS data that meet strict analytical criteria required for clinical assays [8].

Case Study: Plasma Biomarker Panel for Parkinson's Disease

A recent study exemplifies the power of plasma proteomics for neurological disease biomarker development. Researchers employed a multi-phase approach:

Discovery Phase: Unbiased LC-MS/MS analysis of depleted plasma from 10 drug-naïve Parkinson's disease (PD) patients and 10 matched controls identified 895 distinct proteins, with 47 differentially expressed [18].

Targeted Assay Development: A multiplexed targeted MS assay was developed for 121 proteins, focusing on inflammatory pathways implicated in PD pathogenesis [18].

Validation: Application to an independent cohort (99 PD patients, 36 controls, 41 other neurological diseases, 18 isolated REM sleep behavior disorder [iRBD] patients) confirmed 23 significantly differentially expressed proteins in PD versus controls [18].

Panel Refinement: Machine learning identified an 8-protein panel (including Granulin precursor, Complement C3, and Intercellular adhesion molecule-1) that accurately identified all PD patients and 79% of iRBD patients up to 7 years before motor symptom onset [18].

This case study demonstrates how plasma proteomics, coupled with advanced computational analysis, can yield clinically actionable biomarkers even for disorders primarily affecting the central nervous system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Processing and Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Technology | Application & Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | RapiGest SF Surfactant (Waters) [14] | Acid-labile surfactant for protein denaturation; improves protein solubilization and digestion efficiency | Compatible with MS analysis; easily removed by acidification and centrifugation |

| Folch Extraction (Chloroform: Methanol, 2:1) [15] | Gold-standard method for lipid extraction from plasma/serum; provides excellent recovery rates and minimal matrix effects | Particularly valuable for lipidomic workflows; superior to single-phase extractions | |

| Chromatography | Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) PolySULFOETHYL Column [14] | Orthogonal peptide separation prior to RP-LC-MS/MS; significantly increases proteome coverage | Critical for deep profiling of complex samples; enables identification of low-abundance proteins |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Tips [14] | Microscale desalting and concentration of peptide mixtures; prepares samples for MS analysis | Essential for cleaning up samples after digestion or fractionation; improves MS sensitivity | |

| Mass Spectrometry | Q-Exactive Plus Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) [14] | High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) Orbitrap instrument; enables both discovery and targeted proteomics | Ideal for DIA and targeted methods; high sensitivity and mass accuracy |

| TripleQuadrupole Mass Spectrometer (e.g., SCIEX QTRAP) [6] | Gold standard for targeted quantitation via MRM/SRM; excellent sensitivity and quantitative precision | Preferred for validation studies; high reproducibility across large sample sets | |

| Data Analysis | TEAQ (Targeted Extraction Assessment of Quantification) [8] | Software pipeline for selecting biomarker candidates from DIA-MS data that meet analytical validation criteria | Bridges discovery and validation; selects peptides based on linearity, specificity, repeatability |

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen) [18] | Bioinformatics tool for pathway analysis of proteomic data; identifies biologically relevant networks | Helps contextualize biomarker findings; identifies perturbed pathways in disease states |

Integrated Strategy for the Biomarker Pipeline

The most effective biomarker development strategies leverage both proximal fluids and blood samples at different pipeline stages:

Discovery Phase: Utilize proximal fluids (e.g., CSF for neurological disorders, nipple aspirate for breast cancer) to identify high-quality candidate biomarkers with strong biological rationale [14] [17].

Verification Phase: Develop targeted MS assays (e.g., MRM, TEAQ) to verify candidate biomarkers in plasma/serum from moderate-sized cohorts (50-100 patients) [8] [6].

Validation Phase: Conduct large-scale (100-1000+ samples) validation of refined biomarker panels in plasma/serum, focusing on clinical applicability and robustness [18].

Clinical Implementation: Translate validated biomarkers into clinical practice using plasma/serum-based tests, potentially incorporating automated sample preparation and high-throughput MS platforms [19].

This integrated approach maximizes the strengths of each sample type while acknowledging practical constraints, ultimately accelerating the development of clinically impactful biomarkers for early disease detection, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring.

The journey to discovering a robust, clinically relevant biomarker from proteomic mass spectrometry data is a complex endeavor, highly susceptible to failure in its initial phases. Pre-analytical variability—introduced during sample collection, processing, and storage—represents a paramount challenge to the integrity of biospecimens and the validity of downstream data. In the context of a biomarker identification pipeline, inconsistencies in these early stages can artificially alter the plasma proteome, leading to irreproducible results, false leads, and ultimately, the failure of promising biomarkers to validate in independent cohorts. Evidence suggests that a significant portion of errors in omics studies originate in the pre-analytical phase, underscoring the critical need for standardized protocols [20]. This document outlines essential steps and controls to ensure sample quality, thereby enhancing the reproducibility and translational potential of proteomic mass spectrometry research.

Critical Pre-analytical Variables and Their Effects on the Proteome

A comprehensive understanding of how handling procedures affect biospecimens is the first step toward mitigation. The following variables have been demonstrated to significantly impact the plasma proteome.

Blood Collection and Processing Delays

The time interval between blood draw and plasma separation is one of the most critical factors. Research using an aptamer-based proteomic assay measuring 1305 proteins found that storing whole blood at room temperature for 6 hours prior to processing significantly changed the abundance of 36 proteins compared to immediate processing. When stored on wet ice (0°C) for the same duration, an even greater effect was observed, with 148 proteins changing significantly [21]. Another LC-MS study concluded that pre-processing times of less than 6 hours had minimal effects on the immunodepleted plasma proteome, but delays extending to 96 hours (4 days) induced significant changes in protein levels [22].

Centrifugation Conditions

The force applied during centrifugation to generate plasma can profoundly influence sample composition. The use of a lower centrifugal force (1300 × g) resulted in the most substantial alterations in the aptamer-based study, changing 200 out of 1305 proteins assayed. These changes are likely due to increased contamination of the plasma with platelets and cellular debris [21]. In contrast, a separate proteomic study comparing single- versus double-spun plasma showed minimal differences, suggesting that specific protocols must be benchmarked for their intended application [22].

Post-Processing and Storage Variables

After plasma separation, handling remains crucial. Holding plasma at room temperature or 4°C for 24 hours before freezing has been shown to activate the complement system in vitro and alter the abundance of 75 and 28 proteins, respectively [21]. Furthermore, multiple freeze-thaw cycles are a well-known risk. However, one LC-MS study indicated that the impact of ≤3 freeze-thaw cycles was negligible, regardless of whether they occurred in quick succession or over 14–17 years of frozen storage at -80 °C [22].

Phlebotomy Technique

The method of blood draw itself can be a source of variation. An exploratory study using Multiple Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry (MRM-MS) found that different phlebotomy techniques (e.g., IV with vacutainer, butterfly with syringe) significantly affected 12 out of 117 targeted proteins and 2 out of 11 complete blood count parameters, such as red blood cell count and hemoglobin concentration [23].

Table 1: Summary of Pre-analytical Variable Effects on the Plasma Proteome

| Pre-analytical Variable | Experimental Conditions | Observed Impact on Proteome | Primary Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Processing Delay | 6h at Room Temperature | 36 proteins significantly changed | [21] |

| Blood Processing Delay | 6h at 0°C (wet ice) | 148 proteins significantly changed | [21] |

| Blood Processing Delay | 96h at elevated temperature | Significant changes apparent; elevated protein levels | [22] |

| Centrifugation Force | 1300 × g vs. 2500 × g | 200 proteins significantly changed (196 increased) | [21] |

| Plasma Storage Delay | 24h at Room Temperature | 75 proteins changed; complement activation | [21] |

| Plasma Storage Delay | 24h at 4°C | 28 proteins changed; complement activation | [21] |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles | ≤3 cycles | Negligible impact | [22] |

| Phlebotomy Technique | 4 different methods | 12 of 117 targeted proteins significantly changed | [23] |

Standardized Protocols for Plasma Collection and Processing

To mitigate the variables described above, the implementation of standardized protocols is non-negotiable. The following protocol, synthesizing recommendations from recent literature, is designed for the collection of K2 EDTA plasma, a common starting material for proteomic studies.

Materials and Reagents

- Blood Collection Tubes: Spray-coated K2 EDTA Vacutainer tubes (e.g., BD Vacutainer #368589).

- Equipment: Refrigerated centrifuge capable of maintaining 4°C and equipped with a horizontal rotor (swing-out bucket).

- Consumables: Sterile cryovials for plasma aliquoting.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Blood Draw: Perform venipuncture with a 21-gauge needle or similar. Release the tourniquet within one minute of application [22]. Invert the K2 EDTA tubes 8 times immediately after collection to ensure proper mixing with the anticoagulant [22].

- Immediate Handling: Transport blood tubes to the processing laboratory at ambient temperature without delay.

- Initial Centrifugation: Centrifuge tubes within 30 minutes of collection. Use a refrigerated centrifuge (4°C) with a horizontal rotor set for 15 minutes at 1500-2500 × g [22] [21].

- Plasma Transfer: Carefully aspirate the upper plasma layer using a pipette, ensuring the buffy coat (white cell layer) is not disturbed. Transfer the plasma to a sterile 15 mL conical tube.

- Secondary Centrifugation (for platelet-poor plasma): To minimize platelet contamination, perform a second centrifugation step on the transferred plasma for 15 minutes at 2000 × g, 4°C [22].

- Aliquoting and Freezing: Pool plasma from the same donor (if multiple tubes were drawn) and aliquot into sterile cryovials (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL per vial). Snap-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen or a dry-ice ethanol bath and transfer to a -80°C freezer for long-term storage [22] [21]. Avoid any freeze-thaw cycles.

Implementing a Comprehensive Quality Control Framework

A robust QC strategy combines the monitoring of known confounders with the use of standardized QC samples to track technical performance across the entire workflow.

Monitoring Key Pre-analytical Confounders

The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) Blood Task Force's MIBlood-EV framework provides a excellent model for reporting pre-analytical variables, focusing on key confounders [24]:

- Hemolysis: Qualitatively assess by visual inspection or quantitatively using a haematology analyzer. Hemolysis can release abundant cellular proteins that interfere with the plasma proteome.

- Residual Platelets: Quantify using a haematology analyzer post-centrifugation to ensure the effectiveness of the plasma preparation protocol.

- Lipoproteins: Monitor as these can co-isolate with targets of interest like extracellular vesicles and confound analysis.

Quality Control Samples for Mass Spectrometry

Incorporating well-characterized QC samples into the mass spectrometry workflow is essential for inspiring confidence in the generated data. These materials can be used for System Suitability Testing (SST) before a batch run and as process controls run alongside experimental samples [25].

Table 2: Quality Control Samples for Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

| QC Level | Description | Example Materials | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| QC1 | Known mixture of purified peptides or protein digest | Pierce Peptide Retention Time Calibration (PRTC) Mixture | System Suitability Testing (SST), retention time calibration |

| QC2 | Digest of a known, complex whole-cell lysate or biofluid | HeLa cell digest, commercial yeast or E. coli lysate digest | Process control; monitors overall workflow performance |

| QC3 | QC2 sample spiked with isotopically labeled peptides (QC1) | Labeled peptides spiked into a HeLa cell digest | SST; enables monitoring of quantitative accuracy and detection limits |

| QC4 | Suite of different samples or mixed ratios | Two different cell lysates mixed in known ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:2) | Evaluating quantitative accuracy and precision in label-free experiments |

These QC samples allow for the separation of instrumental variance from intrinsic biological variability. Data from many commercially available QC standards are available in public repositories like ProteomeXchange, enabling benchmarking of laboratory performance and data analysis workflows [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for Standardized Proteomic Sample Preparation

| Reagent / Kit Name | Supplier | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| BD Vacutainer K2 EDTA Tubes | BD | Standardized blood collection for plasma preparation; contains spray-coated K2 EDTA anticoagulant. |

| Pierce Peptide Retention Time Calibration (PRTC) Mixture | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A known mixture of 15 stable isotope-labeled peptides used for LC-MS system suitability and retention time calibration. |

| MARS Hu-14 Immunoaffinity Column | Agilent Technologies | Depletes the top 14 high-abundance plasma proteins to enhance detection of lower-abundance potential biomarkers. |

| PreOmics iST Kit | PreOmics | An integrated sample preparation kit that streamlines protein extraction, digestion, and peptide cleanup into a single, automatable workflow. |

| SOMAscan Assay | SomaLogic | An aptamer-based proteomic assay for quantifying >1000 proteins in a small volume of plasma; useful for pre-analytical stability studies. |

The following diagram synthesizes the key stages, decisions, and quality control points in a standardized pre-analytical workflow for proteomic biomarker discovery.

In conclusion, the fidelity of a biomarker discovery pipeline is fundamentally rooted in the rigor of its pre-analytical phase. By systematically standardizing blood collection, processing, and storage protocols, and by integrating a multi-layered quality control strategy that includes monitoring key confounders and using standardized QC materials, researchers can significantly reduce technical noise. This disciplined approach ensures that the biological signal of interest, rather than pre-analytical artifact, drives discovery, thereby accelerating the development of reliable, clinically translatable biomarkers.

Mass Spectrometry Platforms and Acquisition Modes

Mass spectrometry (MS) platforms are defined by how key instrument components are configured and operated. Core components include the ion source (converts molecules to ions), mass analyzer(s) (separates ions by mass-to-charge ratio, m/z), collision cell (fragments ions), and detector (quantifies ions) [26]. The combination of scan modes used in these components defines the data acquisition strategy, primarily categorized into untargeted and targeted approaches [26].

Untargeted Acquisition Modes

Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) is a foundational untargeted strategy. The instrument first performs a full MS1 scan to detect all ions, then automatically selects the most abundant precursor ions for MS/MS fragmentation [26]. DDA provides high-resolution, clean MS2 spectra but is biased toward high-intensity ions and can exhibit poor reproducibility across replicates [26].

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) was designed to enhance reproducibility. It systematically divides the full m/z range into consecutive windows. All precursors within each window are fragmented simultaneously, providing comprehensive MS2 data for nearly all detectable ions independent of intensity [26]. DIA offers excellent reproducibility and sensitivity for low-abundance analytes but produces complex data that requires advanced deconvolution algorithms [26].

Targeted Acquisition Modes

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), performed on triple quadrupole instruments, is the gold standard for targeted quantification. It uses predefined precursor-to-product ion transitions (MRM transitions) for highly selective and sensitive detection of known compounds [26]. MRM delivers unmatched specificity and linearity but requires significant upfront method development and is limited to known targets [26].

Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) is a high-resolution targeted mode. It combines MRM-like specificity with the collection of full, high-resolution fragment ion spectra, providing rich spectral information for confident identification and quantification [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Modes

| Feature | DDA (Untargeted) | DIA (Untargeted) | MRM (Targeted) | PRM (Targeted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Discovery, identification | Comprehensive profiling, quantification | Precise, sensitive quantification | High-resolution targeted quantification |

| Scan Mode | Full scan (MS1), then targeted MS/MS on intense ions | Sequential full MS/MS on all ions in defined m/z windows | Selective monitoring of predefined precursor/fragment pairs | Selective MS2 with full fragment scan |

| Multiplexing | Limited by dynamic exclusion | High, all analytes in windows | High for known transitions | Moderate |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (ion intensity bias) | High (systematic acquisition) | Very High | Very High |

| Ideal For | Novel biomarker discovery, spectral library generation | Large-scale quantitative studies, biomarker verification | Validated biomarker assays, clinical diagnostics | Biomarker validation, PTM analysis |

| Key Limitation | Bias against low-abundance ions | Complex data deconvolution | Limited to known targets; requires method development | Lower throughput than MRM |

Experimental Workflows in Biomarker Research

A coherent pipeline connecting biomarker discovery with established evaluation and validation is critical for developing robust, clinically relevant assays [28]. This pipeline integrates both untargeted and targeted MS approaches.

Figure 1: Integrated biomarker discovery and validation pipeline.

Sample Preparation

Robust sample preparation is essential for clinical proteomics. Common biofluids include blood (plasma/serum), urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [19]. Proteins are typically denatured, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis [19]. Depletion of high-abundance proteins or enrichment of target analytes is often necessary to detect lower-abundance cancer biomarkers, especially in plasma and serum [29]. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, reversal of chemical cross-linking is required prior to digestion [19].

Untargeted Discovery Workflow

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Digested peptides are separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed using DDA or DIA on high-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap) [19].

- Database Searching: MS/MS spectra are searched against protein sequence databases using algorithms (e.g., Sequest, Mascot, X!Tandem) to identify peptide sequences [28].

- Bioinformatics Validation: Identified peptides are rigorously validated. This includes:

- Concordance Analysis: Using multiple database search algorithms to increase confidence in peptide identifications [28].

- Uniqueness Check: Using tools like BLAST to ensure peptide biomarkers are unique to the organism or disease of interest and absent in related species [28].

- False Discovery Rate (FDR) Estimation: Using target-decoy search strategies to measure and control for incorrect peptide assignments [28].

Targeted Verification and Validation Workflow

- Assay Development: Proteotypic peptides representing candidate biomarkers are selected. For MRM, optimal precursor-fragment ion transitions are determined experimentally [29] [27].

- Absolute Quantification: Stable Isotope-labeled Standard (SIS) peptides are added to the sample at a known concentration [29] [27]. These "heavy" peptides have identical physicochemical properties to their endogenous "light" counterparts but are distinguishable by MS. Quantification is based on the light-to-heavy peptide intensity ratio [27].

- LC-MRM/PRM Analysis: Samples are analyzed using targeted MS on triple quadrupole (for MRM) or high-resolution (for PRM) instruments [29].

Figure 2: Targeted proteomics workflow with isotope dilution.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Untargeted Profiling using DIA (SWATH-MS)

This protocol is adapted for biomarker discovery from biofluids using a high-resolution Q-TOF mass spectrometer [19].

I. Sample Preparation

- Plasma/Serum Depletion: Use an immunoaffinity column to remove the top 14 abundant proteins from 20 µL of plasma/serum.

- Protein Digestion:

- Reduce proteins with 10 mM dithiothreitol (56°C, 30 min).

- Alkylate with 25 mM iodoacetamide (room temperature, 30 min in the dark).

- Digest with sequencing-grade trypsin (1:20 enzyme-to-protein ratio, 37°C, overnight).

- Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges and dry in a vacuum concentrator.

II. Liquid Chromatography

- Column: C18 reversed-phase column (75 µm i.d. x 25 cm length, 1.6 µm particle size).

- Gradient: 2-35% mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) over 120 minutes at a flow rate of 300 nL/min.

III. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) on Q-TOF Mass Spectrometer

- MS1 Survey Scan: Acquire one full-scan MS1 spectrum (m/z 350-1400, 250 ms accumulation time).

- DIA MS/MS Scans: Cycle through 64 variable windows covering the m/z 400-1200 range.

- Fragmentation: Use collision energy rolling based on precursor m/z.

- Resolution: Ensure MS2 fragments are acquired with a resolution of at least 30,000.

- Quality Control: Inject a pooled quality control sample every 6-8 experimental samples to monitor instrument performance.

IV. Data Processing

- Process DIA data using specialized software (e.g., Spectronaut, DIA-NN, or Skyline).

- Use a project-specific or public spectral library (e.g., from DDA runs of sample aliquots) to extract and quantify peptide intensities.

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) to identify significantly differentially expressed proteins between case and control groups.

Protocol for Targeted Verification using LC-MRM/MS

This protocol is for verifying a panel of candidate protein biomarkers in plasma [29] [27].

I. Sample Preparation with SIS Peptides

- Follow steps in Section 3.1.I for plasma depletion and digestion.

- Internal Standard Addition: After digestion, add a known amount (e.g., 25-100 fmol) of stable isotope-labeled (SIS) peptides to each sample digest. SIS peptides are spiked in prior to LC-MS analysis.

II. Liquid Chromatography

- Use the same LC conditions as in Section 3.1.II, but the gradient can be shortened to 30-60 minutes for higher throughput.

III. Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) on Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer

- Method Development: For each target peptide, define the precursor ion (m/z) and at least three specific fragment ions. The most intense transition is the quantifier, and the others are qualifiers.

- Chromatographic Method: Schedule MRM transitions within a specific retention time window (e.g., 3-5 minutes wide) to maximize the number of data points per peak and monitor more peptides.

- MS Parameters:

- Dwell time: 10-50 ms per transition.

- Collision energy: Optimized for each peptide.

- Resolution: Unit resolution for both Q1 and Q3.

IV. Data Analysis and Quantification

- Peak Integration: Manually review and integrate peaks for both endogenous ("light") and SIS ("heavy") peptides for all transitions.

- Calculate Ratios: For each peptide, calculate the peak area ratio of light to heavy.

- Determine Concentration: Calculate the absolute concentration of the endogenous peptide using the known concentration of the spiked SIS peptide and the light/heavy ratio.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Proteomic Mass Spectrometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standard (SIS) Peptides | Internal standards for absolute quantification; correct for analytical variability [29] [27]. | Synthesized with 13C/15N on C-terminal Lys/Arg; spiked into sample post-digestion. |

| Trypsin (Sequencing Grade) | Proteolytic enzyme; cleaves proteins at lysine and arginine residues to generate peptides for MS analysis [19]. | Use 1:20-1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio; ensure purity to minimize autolysis peaks. |

| Immunoaffinity Depletion Columns | Remove high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) from plasma/serum to enhance detection of low-abundance biomarkers [29]. | Critical for plasma/serum analysis; can deplete top 7-14 proteins. |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Tips/Cartridges | Desalt and concentrate peptide mixtures after digestion; remove interfering salts and detergents [19]. | Standard step before LC-MS/MS; improves chromatographic performance and signal. |

| Formic Acid | Ion-pairing agent in mobile phase; improves chromatographic peak shape and ionization efficiency in positive ESI mode [19]. | Used at 0.1% in water (mobile phase A) and acetonitrile (mobile phase B). |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) & Iodoacetamide (IAA) | Reduce disulfide bonds (DTT) and alkylate cysteine residues (IAA); denatures proteins and prevents disulfide bond reformation [19]. | Standard step in "bottom-up" proteomics workflow. |

The Proteomic Workflow in Action: From Sample to Spectral Data

In mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics, the profound complexity and vast dynamic range of protein concentrations in biological samples present a significant analytical challenge. Sample preparation, particularly through depletion, enrichment, and fractionation, is therefore not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant for the success of downstream analyses, especially in biomarker discovery pipelines [30] [31]. Effective sample preparation mitigates the dynamic range issue, reduces complexity, and enhances the detection of lower-abundance proteins, which are often the most biologically interesting candidates for disease biomarkers [28] [31]. This application note details standardized protocols and strategic frameworks for preparing proteomic samples, providing researchers with the tools to deepen proteome coverage and improve the robustness of their identifications and quantifications.

Core Principles and Strategic Framework

The primary goal of sample preparation is to simplify complex protein or peptide mixtures to facilitate more comprehensive MS analysis. The strategies can be conceptualized in a hierarchical manner:

- Depletion: The selective removal of a small number of highly abundant proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins from plasma) that otherwise dominate the MS signal [31]. This is often the first step when analyzing biofluids.

- Enrichment: The affirmative selection and concentration of specific protein subsets, such as those with post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) or low molecular weight (LMW) proteins, from a complex background [32] [33].

- Fractionation: The separation of a complex mixture into simpler, less complex sub-fractions based on properties like isoelectric point (pI), hydrophobicity, or molecular weight. This can be applied at the protein or peptide level and is often performed after digestion [28] [34].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these strategies integrate into a coherent proteomic analysis pipeline for biomarker discovery.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immunoaffinity Depletion of High-Abundance Plasma Proteins

This protocol describes the use of a Multiple Affinity Removal System (MARS) column to deplete the top 7 or 14 most abundant proteins from human plasma, thereby enhancing the detection of medium- and low-abundance proteins [31].

Materials:

- MARS-7 or MARS-14 column (Agilent)

- HPLC system with UV detection

- Load/wash buffer and elution buffer (supplied with column)

- Amicon 5 kDa molecular weight cutoff filters (Millipore)

- BCA protein assay kit (Pierce)

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute plasma fourfold with the specified load/wash buffer. Remove particulates by centrifuging the diluted plasma through a 0.22 µm spin filter for 1 minute at 16,000 × g.

- Column Equilibration: Equilibrate the MARS column with load/wash buffer at room temperature.

- Sample Loading: Load 160 µL of the diluted, filtered plasma onto the column at a low flow rate (0.125 mL/min for MARS-14, 0.5 mL/min for MARS-7).

- Fraction Collection:

- Collect the flow-through fraction, which contains the depleted plasma, and store at -20°C.

- Use elution buffer to release the bound fraction containing the abundant proteins.

- Buffer Exchange and Concentration: Concentrate the depleted plasma fraction using a 5 kDa MWCO filter and exchange the buffer to 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate.

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of the depleted sample using the BCA assay.

Performance Notes: This depletion process is highly reproducible and results in an average 2 to 4-fold global enrichment of non-targeted proteins. However, even after depletion, the 50 most abundant proteins may still account for ~90% of the total MS signal, underscoring the need for subsequent fractionation or enrichment steps for deep proteome mining [31].

Protocol 2: Automated In-Solution Digestion for High-Throughput Analysis

This protocol is designed for robust, high-throughput sample preparation without depletion or pre-fractionation, suitable for large-scale clinical cohorts [35]. It can be performed using an automated liquid-handling platform.

Materials:

- LH-1808 or equivalent liquid handling robot (AMTK)

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP)

- 2-Chloroacetamide (CAA)

- Sequencing-grade trypsin and LysC

- Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

- Home-made C18 spintips (3M Empore C18 material)

Method:

- Dilution & Denaturation: Transfer 5 µL of plasma into a 96-well plate. Add 95 µL of reduction-alkylation buffer (10 mM TCEP, 50 mM CAA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8). Mix thoroughly by pipetting.

- Aliquot & Heat Denature: Transfer a 20 µL aliquot of the diluted plasma to a new plate. Heat at 95°C for 15 minutes to denature proteins, then cool to room temperature.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add a mixture of Lys-C and trypsin (1:100 enzyme-to-protein ratio, 0.6 µg of each enzyme). Incubate the plate at 37°C for 3 hours.

- Reaction Quenching: Quench the digestion by adding 50 µL of 0.1% (v/v) TFA.

- Peptide Cleanup: Desalt the digested peptides using home-made C18 spintips. Lyophilize the eluted peptides for storage or resuspend in 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS analysis.

Performance Notes: This automated workflow achieves a median coefficient of variation (CV) of 9% for label-free quantification and identifies over 300 proteins from 1 µL of plasma without depletion, making it ideal for high-throughput biomarker verification studies [35].

Protocol 3: Micro-Purification and Enrichment Using StageTips

StageTips are low-cost, disposable pipette tips containing disks of chromatographic media for micro-purification, enrichment, and pre-fractionation of peptides [36].

Materials:

- Pipette tips (200 µL)

- Teflon mesh-embedded disks (C18, cation-exchange, anion-exchange, TiO₂, ZrO₂)

- Solvents: 0.1% TFA, 0.1% Formic Acid, LC-MS grade water and acetonitrile

Method (C18 Desalting and Concentration):

- Conditioning: Pass 100 µL of methanol through the C18 StageTip by centrifugation.

- Equilibration: Wash with 100 µL of solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA), followed by 100 µL of solvent A (0.1% TFA).

- Sample Loading: Acidify the peptide sample and load it onto the StageTip slowly by centrifugation.

- Washing: Wash with 100 µL of solvent A to remove salts and contaminants.

- Elution: Elute peptides with 50-100 µL of solvent B into a clean tube. Evaporate the solvent in a vacuum concentrator.

Performance Notes: StageTips can be configured with multiple disks for multi-functional applications. For example, combining TiO₂ disks with C18 material enables efficient phosphopeptide enrichment. The entire process for desalting takes ~5 minutes, while fractionation or enrichment requires ~30 minutes [36].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for implementing the described strategies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Proteomic Sample Preparation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| MARS Column (Agilent) | Immunoaffinity column for depletion of top 7 or 14 abundant plasma proteins. | Deep plasma proteome profiling prior to discovery LC-MS/MS [31]. |

| PreOmics iST Kit | Integrated workflow for lysis, digestion, and peptide purification in a single device. | Standardized, high-throughput sample preparation for cell and tissue lysates [37]. |

| StageTip Disks (C18, TiO₂, etc.) | Self-made micro-columns for peptide desalting, fractionation, and specific enrichment. | Desalting peptide digests; enriching phosphopeptides with TiO₂ disks [36]. |

| Rapigest SF | Acid-labile surfactant for protein denaturation; cleaved under acidic conditions to prevent MS interference. | Efficient protein solubilization and digestion without detergent-related ion suppression [38]. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | MS-compatible reducing agent for breaking protein disulfide bonds. | Protein reduction under denaturing conditions as part of the digestion protocol [38] [35]. |

| Tryptsin/Lys-C Mix | Proteolytic enzymes for specific protein digestion into peptides. | High-efficiency, in-solution digestion of complex protein mixtures [35] [34]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

The selection of a sample preparation strategy involves trade-offs between depth of analysis, throughput, and reproducibility. The following table summarizes quantitative data from the cited studies to aid in method selection.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Different Sample Preparation Strategies

| Strategy / Workflow | Proteins Identified (Single Run) | Quantitative Reproducibility (Median CV) | Sample Processing Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunodepletion (MARS-14) [31] | ~25% increase vs. undepleted plasma (Shotgun MS) | -- | ~40 min/sample (depletion only) | Enhancing detection of medium-abundance proteins in plasma. |

| Automated In-Solution Digestion [35] | >300 proteins (from 1 µL plasma) | 9% | High-throughput, 32 samples simultaneously | Large-scale clinical cohort verification studies. |

| SISPROT with 2D Fractionation [35] | 862 protein groups (from 1 µL plasma) | -- | Longer, includes fractionation | Deep discovery profiling from minimal sample input. |

| StageTip Desalting [36] | -- | -- | ~5 minutes | Routine peptide cleanup and concentration for any workflow. |

Integrated Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

The individual strategies of depletion, enrichment, and fractionation find their greatest utility when combined into a coherent pipeline. This is particularly true for biomarker discovery, which progresses from comprehensive discovery to targeted validation. The following diagram outlines an integrated workflow that connects sample preparation strategies with the phases of biomarker development.

This integrated approach ensures that the sample preparation methodology is tailored to the specific goal. The discovery phase leverages extensive fractionation and enrichment to maximize proteome coverage and identify potential biomarker candidates. In contrast, the validation phase prioritizes robustness, reproducibility, and high throughput to confidently assess candidate performance across large patient cohorts [28] [38] [35].

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has become an indispensable tool in biomedical research for the discovery and validation of protein biomarkers [19] [39]. The identification of reliable biomarkers is crucial for early disease detection, prognosis, and monitoring treatment responses [40]. The core of this process lies in the analytical techniques used to acquire proteomic data, with Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), and tandem mass tag (TMT)/isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation (iTRAQ) labeling emerging as the three principal methods [41] [42]. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations in terms of quantification accuracy, proteome coverage, and suitability for different experimental designs within the biomarker discovery pipeline [43] [41]. This article provides a detailed comparison of these core acquisition techniques and presents standardized protocols for their application in clinical and research settings focused on biomarker identification.

Core Principles of MS Acquisition Techniques

Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), often used in label-free quantification, operates by selecting the most abundant peptide precursor ions from an MS1 survey scan for subsequent fragmentation and MS2 analysis [41] [42]. This intensity-based selection provides high-quality spectra for protein identification but can introduce stochastic sampling variability and miss lower-abundance peptides, potentially limiting proteome coverage [41] [19].

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) addresses this limitation through a systematic approach where the entire mass range is divided into consecutive isolation windows, and all precursors within each window are fragmented simultaneously [43] [42]. This comprehensive fragmentation strategy reduces missing values and improves quantitative precision, making it particularly valuable for analyzing complex clinical samples where consistency across many samples is crucial [43] [19].

TMT/iTRAQ Labeling utilizes isobaric chemical tags that covalently bind to peptide N-termini and lysine side chains [41] [44]. These tags have identical total mass but release reporter ions of different masses upon fragmentation, enabling multiplexed quantification of multiple samples in a single MS run [41] [44]. The isobaric nature means peptides from different samples appear as a single peak in MS1 but can be distinguished based on their reporter ion intensities in MS2 or MS3 spectra [42] [44].

Comparative Performance in Biomarker Research

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Core MS Acquisition Techniques for Biomarker Discovery

| Parameter | DDA (Label-Free) | DIA | TMT/iTRAQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Principle | Peak intensity or spectral counting [42] | Extraction of fragment ion chromatograms [42] | Reporter ion intensities [41] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low (individual analysis) [41] | Low (individual analysis) [41] | High (up to 18 samples simultaneously) [42] |

| Proteome Coverage & Missing Values | Moderate, higher missing values [42] | High, fewer missing values [43] [42] | High with fractionation [42] |

| Quantitative Accuracy & Precision | Moderate, susceptible to instrument variation [41] | High, particularly with library-free approaches [43] | High intra-experiment precision [41] |

| Dynamic Range | Broader linear dynamic range [42] | Not specified in sources | Limited by ratio compression [42] |

| Cost & Throughput | Cost-effective for large cohorts [42] | Cost-effective, reduced sample prep [43] | Higher reagent costs, medium throughput [43] [42] |

| Key Advantages | Experimental flexibility, no labeling cost [41] [42] | Comprehensive data recording, high reproducibility [43] [42] | High quantification accuracy, reduced technical variability [43] [41] |

| Key Limitations | Higher missing values, requires strict instrument stability [41] [42] | Complex data analysis [41] [42] | Ratio compression effects, batch effects [42] |

The selection of an appropriate acquisition technique significantly impacts the depth and quality of data obtained in biomarker discovery. DIA, particularly in library-free mode using software such as DIA-NN, has demonstrated performance comparable to TMT-DDA in detecting target engagement in thermal proteome profiling experiments, making it a cost-effective alternative [43]. TMT methods excel in multiplexing capacity, allowing up to 18 samples to be analyzed simultaneously, thereby reducing technical variability [42]. However, they suffer from ratio compression effects that can underestimate true quantification differences [42]. Label-free DDA provides maximum experimental flexibility and is suitable for large-scale studies, though it typically yields higher missing values and requires stringent instrument stability [41] [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for DIA-Based Biomarker Screening

Sample Preparation and Liquid Chromatography

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Extract proteins from biological samples (e.g., cell lysates, tissue, plasma) using appropriate lysis buffers. Digest proteins into peptides using trypsin following standard protocols [43] [40].

- Peptide Cleanup: Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges or stage tips.

- Liquid Chromatography: Separate peptides using nano-flow liquid chromatography with a reversed-phase C18 column and a gradient of 60-120 minutes, depending on desired depth of analysis [19].

Mass Spectrometry Data Acquisition

- MS Instrument Setup: Utilize a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap) capable of DIA acquisition.

- DIA Method Configuration: Divide the typical m/z range (e.g., 400-1000) into consecutive isolation windows. Window size can be fixed (e.g., 25 m/z) or variable, with narrower windows in crowded regions [43] [42].

- Cycling Method: Implement a cycle consisting of one MS1 scan followed by MS2 scans of all isolation windows. Adjust cycle time to ensure sufficient points across chromatographic peaks [42].

Data Processing and Analysis

- Library Generation: Generate a spectral library using either:

- Peptide Identification and Quantification: Match DIA data against the spectral library to identify peptides and extract fragment ion chromatograms for quantification [43] [42].

- Statistical Analysis: Process quantitative data using bioinformatics tools to identify differentially expressed proteins with statistical significance.

Protocol for TMT/iTRAQ-Based Biomarker Verification

Sample Labeling and Pooling

- Peptide Labeling: Reconstitute desalted peptides from each sample in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.5). Dissolve TMT or iTRAQ reagents in anhydrous acetonitrile and add to respective peptide samples. Incubate at room temperature for 1-2 hours [41] [44].

- Reaction Quenching: Add 5% hydroxylamine to stop the labeling reaction and incubate for 15 minutes.

- Sample Pooling: Combine equal amounts of each labeled sample into a single tube. Vacuum centrifuge to reduce volume if necessary [42] [44].

Fractionation and Mass Spectrometry

- Peptide Fractionation: Perform high-pH reversed-phase fractionation to reduce sample complexity. Use a C18 column with a stepwise or shallow gradient of acetonitrile in ammonium hydroxide (pH 10) to collect 8-16 fractions [42].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Reconstitute each fraction in loading solvent and analyze using nano-LC-MS/MS with a DDA method.

- MS Method: Acquire MS1 spectra at high resolution (e.g., 60,000-120,000). Select top N most intense precursors for HCD fragmentation. Set HCD collision energy to optimize reporter ion generation [44].

Data Analysis

- Database Searching: Search raw files against appropriate protein sequence databases using search engines such as Mascot, SEQUEST, or Andromeda [12] [45].

- Reporter Ion Quantification: Extract reporter ion intensities from MS2 or MS3 spectra. Apply isotope correction factors as recommended by reagent manufacturers [44].

- Normalization and Statistical Analysis: Normalize data across channels and perform statistical tests to identify significantly altered proteins between sample groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MS-Based Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|