Getting Started with Genomic Variant Annotation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

This guide provides a foundational and practical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals embarking on genomic variant annotation.

Getting Started with Genomic Variant Annotation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

This guide provides a foundational and practical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals embarking on genomic variant annotation. It covers core concepts, from defining genetic variants and their functional impact to implementing best-practice workflows for coding and non-coding regions. The article delves into advanced methodologies, including high-throughput functional assays, and addresses critical challenges such as tool discrepancies and the optimization of variant prioritization. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of validation strategies and emerging technologies, equipping readers to accurately interpret genetic variation for disease research and therapeutic development.

Understanding Variant Annotation: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

The dramatic reduction in the cost and time of sequencing has democratized access to whole genome and exome data. However, the transition from raw sequencing data to biologically and clinically meaningful insights remains a significant challenge. The core bottleneck in genomic analysis is no longer data generation but rather data interpretation [1]. This process, which bridges the gap between a list of genetic variants and an understanding of their functional impact on health and disease, is critical for advancing personalized medicine, diagnosing rare genetic disorders, and identifying novel drug targets [2]. The primary goal of functional interpretation is to move beyond simply identifying the location of a variant to predicting its potential consequences on protein function, gene regulation, and cellular processes, ultimately elucidating its role in phenotype and disease pathology [1].

This guide provides a comprehensive technical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals embarking on genomic variant annotation research. It outlines the definitive goal of the interpretation workflow: to systematically prioritize genetic variants and translate their predicted functional impacts into actionable biological insights that can inform clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development.

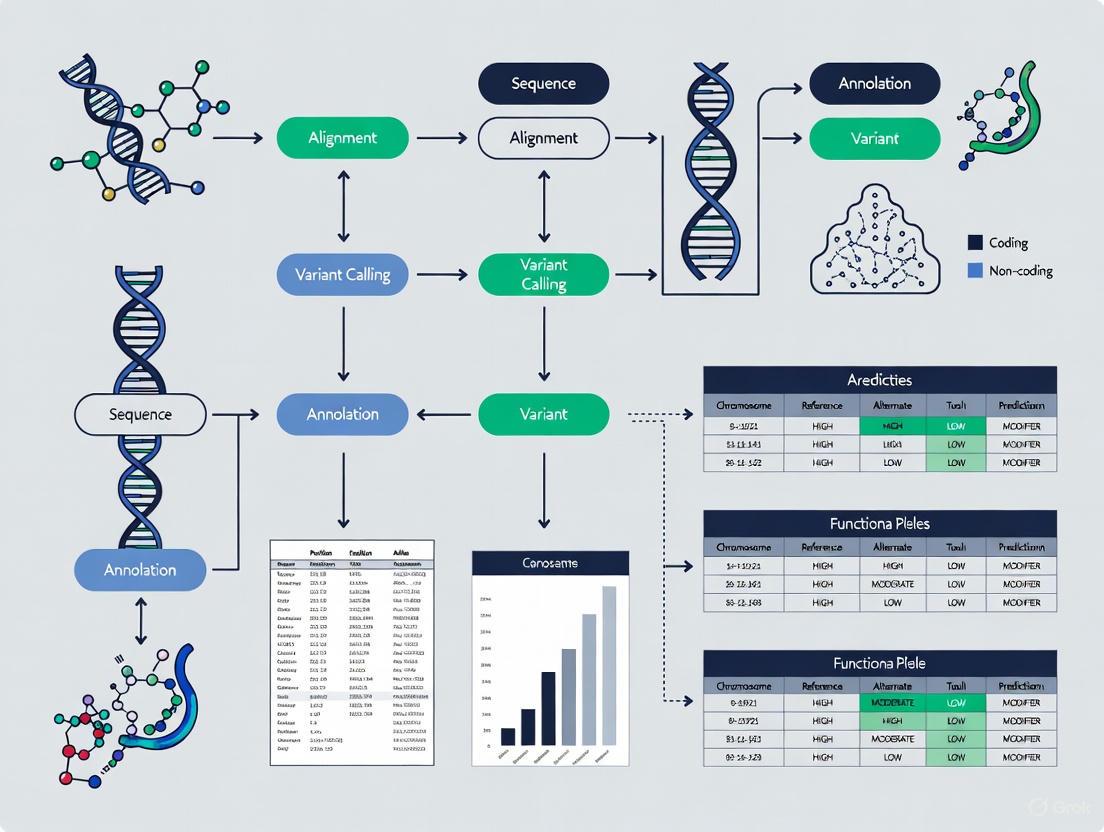

The Genomic Interpretation Workflow: From Sequencing to Insight

The journey from raw sequencing data to a functionally annotated and prioritized variant list is a multi-stage process. The following diagram illustrates the complete logical workflow, highlighting the key steps and decision points.

Core Technical Stages: A Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Data Preprocessing and Variant Calling

The foundational stage of the workflow involves generating a high-confidence set of genetic variants from raw sequencing reads.

- Read Alignment: The process begins by mapping short sequencing reads from FASTQ files to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38). Tools like BWA-MEM are standard for this task, as they efficiently handle the alignment of millions of reads, accounting for possible gaps and mismatches [3]. The output is a Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) file, which is then converted to its binary, compressed counterpart (BAM) for efficient storage and processing.

- Variant Calling: The sorted BAM file is analyzed to identify sites where the sequenced DNA differs from the reference genome. The

bcftools mpileupandcallcommands are commonly used for this purpose [3]. Thempileupstep examines the aligned reads to compute the likelihood of variants at each genomic position, while thecallstep makes the final determination, outputting a Variant Call Format (VCF) file. This file contains the genomic coordinates of the variants (chromosome, position), the reference and alternate alleles, and initial quality metrics.

Functional and Clinical Annotation

Annotation is the critical step that transforms a generic list of variants into a biologically meaningful dataset. This involves layering information from various biological databases onto each variant in the VCF file.

- Functional Impact Prediction: Tools like the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) and SnpEff are the workhorses of this stage [1] [4]. They determine the genomic context of each variant (e.g., intronic, exonic, intergenic) and predict its molecular consequence. For coding variants, this includes classifying the effect as missense, nonsense, synonymous, or frameshift, and predicting its impact on the protein sequence and structure [3].

- Integration of External Databases: Clinical and population frequency data are indispensable for prioritization. ClinVar is a key resource that provides assertions about the clinical significance of variants (e.g., Pathogenic, Benign) [5] [3]. Population databases like gnomAD provide allele frequencies across diverse populations, helping to filter out common variants unlikely to cause rare, severe diseases [5]. Annotation pipelines cross-reference variants against these and other databases, appending the information to the VCF's INFO field.

Variant Filtering and Prioritization

With annotation complete, the goal is to narrow down thousands of variants to a manageable shortlist for further investigation.

- Application of Biological and Clinical Filters: In a clinical context, such as diagnosing a rare disease, one might first filter for variants that are rare in the population (e.g., gnomAD allele frequency < 0.01), have a predicted deleterious effect (e.g., stop-gain, frameshift), and are classified as "Pathogenic" in ClinVar [5]. For trio analysis (e.g., parent-child), inheritance models (e.g., de novo, recessive) can be applied.

- Case Study Example: As demonstrated in a Sarek pipeline tutorial, a systematic approach can identify a causative variant. The process involved filtering a case sample for homozygous alternative alleles not present in a control, leading to the identification of a nonsense mutation in the

COL6A1gene. Cross-referencing with ClinVar confirmed its pathogenic status, providing a molecular diagnosis [5].

A successful variant interpretation project relies on a suite of bioinformatics tools, databases, and computational resources. The table below catalogues the key components of a modern genomic interpretation toolkit.

Table 1: Essential Resources for Genomic Variant Interpretation

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management | Sarek [5], cio-abcd/variantinterpretation [4] | Automated end-to-end variant calling & annotation | Built on Nextflow for portability & reproducibility; integrates multiple best-practice tools. |

| Functional Annotation | Ensembl VEP [1] [4] | Predicts variant consequences on genes & transcripts | Annotates with consequence, SIFT, PolyPhen; uses cache for public databases. |

| Functional Annotation | SnpEff [3] | Genomic variant effect annotation | Annotates effects, impacts; used for adding ANN field to VCF. |

| Clinical Annotation | ClinVar [5] [3] | Archive of human variant interpretations | Provides clinical significance (Pathogenic/Benign) for variant prioritization. |

| Population Frequency | gnomAD [5] | Catalog of human genetic variation | Filters common polymorphisms; inspects gene constraint (LOEUF score). |

| VCF Manipulation | bcftools [4] [3] | VCF processing & normalization | Indexing, filtering, normalization (left-align indels), merging files. |

| Reporting | MultiQC [4] | Quality control report generation | Summarizes QC metrics from multiple tools into a single HTML report. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

As the field evolves, several advanced topics are becoming integral to comprehensive variant interpretation.

- The Non-Coding Challenge: A significant limitation of early genomic studies was their focus on protein-coding regions. It is now understood that the majority of disease-associated variants from GWAS lie in non-coding regions [1]. Advanced annotation must therefore include regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, and non-coding RNAs. Techniques like Hi-C, which probes the 3D organization of the genome, are vital for linking non-coding variants to the genes they potentially regulate [1].

- The Rise of Multi-Omics and AI: Integrating genomic data with other molecular layers—such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics—provides a more holistic view of a variant's functional impact [6]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence and machine learning are being leveraged to improve the accuracy of variant calling (e.g., DeepVariant) and to predict pathogenicity from sequence alone, helping to interpret variants of uncertain significance (VUS) [6].

- Reproducibility and Data Reusability: Ensuring that genomic analyses are reproducible and that data can be reused by the community is a critical challenge. Incomplete metadata and non-standardized reporting hamper this goal [7]. Adherence to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles and the use of containerized workflows (e.g., Docker, Singularity) are essential practices for robust and shareable genomic science [4] [7].

The path from variant calling to functional interpretation is a complex but well-defined process that is fundamental to unlocking the value of genomic data. By following a structured workflow—encompassing rigorous data generation, comprehensive functional and clinical annotation, and systematic prioritization—researchers can transform a list of genetic differences into actionable biological insights. As technologies for sequencing and computational analysis continue to advance, the goal remains constant: to precisely determine the functional consequences of genetic variation, thereby accelerating the delivery of precision medicine and the development of novel therapeutics.

Genetic variants are differences in the DNA sequence that occur naturally between individuals in a population and form the basis of genetic diversity [8]. The genetic blueprint of every living organism, from humans to microbes, is written in DNA and shaped by a remarkable phenomenon: genetic variation [9]. These variations make each of us unique, contribute to susceptibility to certain diseases, and influence our response to the environment [9]. For scientists, understanding these genomic variants is critical not just for health research but also for advancing fields like agriculture and environmental sustainability [9].

The analysis of high-quality genomic variant data offers a more complete understanding of the human genome, enabling researchers to identify novel biomarkers, stratify patients based on disease risk factors, and decipher underlying biological pathways [10]. While the availability of genomic data has sharply increased in recent years, the accessibility of bioinformatic tools to aid in its preparation is still lacking, primarily due to the large volume of data, associated computational and storage costs, and difficulty in identifying targeted and relevant information [10].

Fundamental Variant Types and Characteristics

Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs)

Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs), often referred to as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) when discussing frequent variations in populations, represent the most prevalent type of genetic variation [9] [1] [8]. Each SNV represents a change at a single nucleotide—the basic building block of DNA [9]. In every human genome, there are typically around 4 to 5 million SNVs [9].

The implications of SNVs are profound, especially when they occur in coding regions or regulatory elements of genes [9]. When SNVs occur within coding regions, they can result in amino acid substitutions (missense mutations), leading to altered protein structure and function [9]. In some cases, this change can be benign, but in others, it can significantly impact biological processes and contribute to disease [9]. Similarly, SNVs in regulatory elements can disrupt the normal control of gene expression, affecting when, where, and how much of a protein is produced [9]. These disruptions have the potential to influence a wide array of conditions, including genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia, as well as complex diseases like cancer [9].

SNVs have become very important markers for certain diseases, such as breast cancer, and serve as guideposts for developing personalized treatments [8]. In fact, there are approximately 180 SNPs associated with the development of breast cancer [8].

Insertion and Deletion Variations (Indels)

Insertions and Deletions (Indels) represent another significant class of genetic variation, involving the addition or removal of small segments of DNA within the genome [9]. Indels can range in size from just a single nucleotide to a few dozen base pairs, but even these seemingly minor changes can have dramatic effects on gene function [9]. This is especially true when indels occur within coding regions of the genome, as they can disrupt the gene's reading frame, a phenomenon known as a frameshift mutation [9].

Even small indels can have a considerable impact on biological processes and are frequently associated with genetic diseases [9]. It's estimated that humans have several million indels in their genome [8]. In the disease cystic fibrosis, for example, indels are responsible for the deletion of a single amino acid that triggers the disease [8]. The detection of small variants like SNVs and indels requires a sequencing technology that prioritizes high accuracy to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors and can handle difficult-to-sequence regions to ensure comprehensive detection [9].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary Genetic Variant Types

| Variant Type | Definition | Typical Size Range | Primary Functional Impact | Example Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | Change at a single nucleotide position | 1 base pair | Amino acid substitution, disrupted regulatory sites | Cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, cancer [9] |

| Insertions/Deletions (Indels) | Addition or removal of DNA segments | 1 to ~10,000 base pairs [8] | Frameshift mutations, disrupted reading frames | Cystic fibrosis [9] [8] |

| Structural Variants (SVs) | Larger genomic rearrangements | >50 base pairs [9] | Gene disruption, rearrangements of key genomic regions | Autism, schizophrenia, cancer [9] |

| Copy Number Variants (CNVs) | Duplication or deletion of large sections | Large segments (genes or chromosomal regions) | Altered gene dosage | Autism spectrum disorder, developmental disorders [9] |

The Critical Challenge of Non-Coding Regions

The Prevalence and Importance of Non-Coding Variants

The majority of human genetic variation resides in non-protein coding regions of the genome [1] [11]. While the most studied variants are those in coding regions that directly alter protein sequences, the challenge of exploring non-coding regions (intergenic, intronic) and providing exhaustive functional annotation of these unknown regions remains substantial, despite the critical role that non-coding regions play in human disease [1]. The expanding collection of human WGS data, combined with the understanding of regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, transcription factor binding sites (TFBS), non-coding RNAs, and transposable elements, has the potential to transform our limited knowledge of the functional importance of these regions into a wealth of information [1].

Mutations in non-coding regions can affect the binding of transcription factors and alter the regulation of gene expression [12]. Such mutations may contribute to the development of disease [12]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified hundreds of thousands of variants associated with complex pathological phenotypes, most of them in non-coding DNA [12]. Determining the functional effects of these variants has been a major challenge for GWAS [12].

Regulatory Elements in Non-Coding Regions

Non-coding regions contain critical regulatory elements that control gene expression. The key regulatory elements include:

- Promoters and Enhancers: Regions that control the initiation and rate of transcription [1]

- Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBS): Specific DNA sequences where transcription factors bind to regulate transcription [1]

- Non-coding RNAs: Functional RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins, including microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs [1]

- DNA Methylation Sites: Epigenetic modifications that regulate gene expression [1]

- Transposable Elements: DNA sequences that can change position within the genome [1]

The crux of a mechanistically insightful genome annotation lies in the functional interpretation at the gene level, rendering the interpretation of intergenic and non-coding variants particularly difficult [1]. By providing methods and resources for comprehensive functional annotation of both coding and non-coding regions, we can enhance our understanding of the relationship between non-coding variation and clinical disease [1]. This, in turn, will provide a more thorough understanding of disease biology and could reveal opportunities for developing novel therapeutic targets, generating novel druggable biomarkers, and identifying new drug candidates [1].

Experimental Methodologies for Variant Analysis

Sequencing Technologies and Variant Calling

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has enabled a drastic growth in the number of sequencing projects by largely increasing the sequence output and by lowering overall costs [13]. Certain projects involve the sequencing of an organism whose genome is already available [13]. These projects, called resequencing projects, generally involve two steps: the mapping of reads onto the known genome and the subsequent analysis of divergent features between the reference genome and the mapped sequences [13].

The detection of small variants like SNVs and indels requires a sequencing technology that prioritizes high accuracy to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors and can handle difficult-to-sequence regions to ensure comprehensive detection [9]. HiFi sequencing provides high-resolution insights into these small genetic variants, making it easier to detect SNVs, even in challenging regions of the genome such as homopolymers or GC-rich sequences [9]. This precision is equally critical for identifying indels, reducing the risk of missing critical mutations and providing a powerful tool for understanding genetic contributions to disease [9].

Benchmarking Variant Calling Pipelines

Recent studies have compared various bioinformatics pipelines for whole genome sequencing data pre-processing. These comparisons involve different mapping and alignment approaches and variant calling pipelines, with performance assessed by computation time, F1 score, precision, and recall [14].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Variant Calling Pipelines for SNVs and Indels

| Pipeline (Mapping/Variant Calling) | F1 Score (SNVs) | Precision (SNVs) | Recall (SNVs) | F1 Score (Indels) | Precision (Indels) | Recall (Indels) | Compute Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGEN/DRAGEN | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 36 ± 2 [14] |

| DRAGEN/DeepVariant | 0.995 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.983 | 0.991 | 0.975 | 256 ± 7 [14] |

| DRAGEN/GATK | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.986 | 0.971 | 0.976 | 0.966 | ~200 [14] |

| GATK/DRAGEN | 0.991 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.980 | 0.983 | 0.977 | ~220 [14] |

| GATK/DeepVariant | 0.993 | 0.996 | 0.990 | 0.977 | 0.987 | 0.967 | ~414 [14] |

| GATK/GATK | 0.986 | 0.989 | 0.983 | 0.967 | 0.974 | 0.960 | ~323 [14] |

In the mapping and alignment step, the DRAGEN pipeline was faster than the GATK with BWA-MEM2 pipeline [14]. DRAGEN showed systematically higher F1 score, precision, and recall values than GATK for single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and Indels in simple-to-map, complex-to-map, coding and non-coding regions [14]. In the variant calling step, DRAGEN was fastest [14]. In terms of accuracy, DRAGEN and DeepVariant performed similarly and both superior to GATK, with slight advantages for DRAGEN for Indels and for DeepVariant for SNVs [14].

Annotation Workflows and Functional Prediction

Variant Annotation Processes

Variant annotation is the process of associating metadata from public databases with corresponding variant data [10]. The choice of annotations can have a significant impact on the interpretation and conclusions of genomic analyses [10]. Functional annotation of genetic variants is a critical step in genomics research, enabling the translation of sequencing data into meaningful biological insights [1].

The major types of genetic variation include Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and small insertions or deletions (indels) of two or more nucleotides, often detected through Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) or Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) at the individual level [1]. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) also refer to changes in a single nucleotide in a DNA sequence, although they represent frequent variations in the genome shared across a population, typically identified through GWAS [1]. While the concept of variant identification involves the detection of the precise location of variants on the reference genome and determining the alternate alleles, functional annotation specifically refers to predicting the potential impact of these variants on protein structure, gene expression, cellular functions, and biological processes [1].

Variant Annotation and Analysis Workflow

AI and Machine Learning Approaches

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a potent tool in identifying genetic mutations [12]. By leveraging AI capabilities, scientists can rapidly and accurately analyze vast amounts of data [12]. AI algorithms, such as machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), are used in genomic analysis to process and interpret large amounts of genetic data [12]. These algorithms can identify patterns, make predictions, and classify genetic variations based on training from large datasets [12].

One of the first works in this area was done by Kircher et al. (2014), who developed a computational framework called Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) that integrates different annotations to assess the effects of genetic variants in the human genome [12]. They created a variant-by-annotation matrix containing millions of observed and simulated genetic variants along with their unique annotations [12]. They then trained a support vector machine (SVM) using features derived from the annotations to score all possible single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the human genome [12].

Two notable examples of AI solutions for mutation detection are DeepSEA and ExPecto, both of which are based on DL [12]. DeepSEA is a DL method specifically designed to predict the effects of sequence changes on chromatin [12]. It can accurately predict the epigenetic state of a sequence, including factors such as transcription factor binding, DNase I sensitivity, and histone marks in multiple cell types [12]. This capability allows DeepSEA to predict the chromatin effects of sequence variants and prioritize regulatory variants [12].

ExPecto is another DL-based approach focused on understanding gene regulation [12]. It can accurately predict the tissue-specific transcriptional effects of mutations directly from a DNA sequence [12]. This includes the ability to predict the effects of rare or previously unobserved mutations [12]. It prioritizes causal variants within loci associated with disease or traits using data from publicly available GWAS [12].

One of the most recent developments is the DEMINING method created by Fu et al. (2023), which directly detects disease-linked genetic mutations from RNA-seq datasets [12]. By utilizing DEMINING to RNA-seq data from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, previously underappreciated mutations were found in unannotated AML-connected gene loci [12].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

The landscape of variant annotation tools is quite complex, as different tools target different genomic regions and perform different types of analyses [1]. Some tools specialize in annotating exonic (protein-coding) regions, focusing on variants that may alter amino acid sequences and affect protein function or structure [1]. These tools provide insights into the potential pathogenicity of missense mutations and other coding variants [1]. Other tools concentrate on non-exonic intragenic regions, such as introns and untranslated regions (UTRs), as well as intergenic regions [1].

Table 3: Essential Tools and Databases for Genomic Variant Annotation

| Tool/Database | Primary Function | Variant Type Applicability | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensembl VEP [1] [10] | Variant effect prediction | SNVs, Indels, SVs | Maps variants to genomic features, suited for large-scale WGS/WES |

| ANNOVAR [1] | Variant functional annotation | SNVs, Indels | Handles large-scale annotation tasks for WGS/WES projects |

| SnpEff/SnpSift [10] | Variant effect annotation and filtering | SNVs, Indels | Simplicity, portability, and efficiency; supports custom databases |

| dbNSFP [10] | Functional pathogenicity scores | SNVs | Provides 36 different functional pathogenicity scores (SIFT, PolyPhen, CADD) |

| ClinVar [10] | Clinical significance archive | All variant types | Public archive of genetic variants and their significance in human disease |

| dbSNP [10] | Variant repository | Primarily SNPs | Centralized repository of genetic variation; auto-generates IDs for known variants |

| Segtor [13] | Rapid annotation for NGS | Coordinates, SNVs, Indels, SVs | Uses segment trees instead of DBMS; determines position relative to genes |

| DeepVariant [14] [12] | AI-based variant calling | SNVs, Indels | Deep learning-based variant caller; high accuracy for SNVs |

| CADD [12] | Pathogenicity prediction | SNVs | Integrates multiple annotations using machine learning |

Genetic variants, particularly SNVs and indels, represent fundamental components of genetic diversity with profound implications for health and disease [9] [8]. The challenge of non-coding regions remains substantial in genomic research, as the majority of human genetic variation resides in these areas and their functional interpretation is complex [1] [11]. Advances in sequencing technologies, bioinformatics pipelines, and AI-powered analysis tools are progressively enhancing our ability to detect, annotate, and interpret these variants with increasing accuracy and efficiency [14] [12].

The field continues to evolve with improvements in annotation methodologies, functional prediction algorithms, and comprehensive databases [1] [10]. By addressing the challenges associated with both coding and non-coding variants, researchers can unlock deeper insights into disease mechanisms, identify novel therapeutic targets, and advance the field of personalized medicine [1] [12]. The integration of AI and machine learning approaches represents a particularly promising direction for future research, enabling more accurate prediction of variant effects and prioritization of clinically significant mutations [12].

The systematic annotation of genomic variants is a foundational step in human genetics, enabling researchers to transition from raw sequencing data to biologically and clinically meaningful insights. This process involves characterizing genetic alterations based on their genomic location, predicted functional impact on genes and regulatory elements, and population frequency. A critical distinction in this field lies between variants occurring in coding regions—the segments of DNA that are translated into protein—and those in non-coding regions, which encompass the vast majority of the genome and include crucial regulatory sequences. Next-generation sequencing technologies have democratized the ability to generate vast amounts of genetic variation data, creating a pressing need for accessible and robust bioinformatic tools to annotate and interpret these findings. The growing gap between data generation and biological interpretation frames the essential challenge that modern annotation pipelines aim to solve [15] [16]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the key genomic features that differentiate coding and non-coding variant impact, equipping researchers with the methodologies and analytical frameworks needed for advanced genomic research.

Fundamental Biological distinctions

Coding Variants: Direct Impact on Protein Sequence

Coding variants occur within the exonic regions of genes that are translated into proteins. Their primary classification depends on their effect on the amino acid sequence of the resulting polypeptide.

- Non-synonymous Variants: These single nucleotide variants (SNVs) alter the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein. They are further categorized as:

- Missense: A change that results in the substitution of one amino acid for another. The functional impact can range from benign to severe, depending on the chemical properties of the substituted amino acids and the structural/functional importance of the residue.

- Nonsense: A change that creates a premature stop codon, leading to truncation of the protein product. This often results in non-functional or degraded proteins.

- Synonymous Variants: Often called "silent" variants, these SNVs do not change the encoded amino acid. While historically considered neutral, they can potentially affect RNA splicing, stability, or translation efficiency.

- Frameshift Variants: Typically caused by insertions or deletions (indels) that are not multiples of three nucleotides, these alterations disrupt the translational reading frame. This usually leads to a completely altered amino acid sequence downstream of the variant and often a premature stop codon.

- In-Frame Indels: These insertions or deletions involve a number of nucleotides that is a multiple of three, resulting in the addition or removal of one or more amino acids from the protein without altering the rest of the reading frame.

Non-Coding Variants: Disruption of Regulatory Grammar

Non-coding variants reside outside of protein-coding exons and exert their influence primarily by disrupting the complex regulatory architecture of the genome. Nearly 90% of disease risk-associated variants identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are found in these non-coding regions [17]. Their functional annotation is more complex and relies on intersecting genomic coordinates with functional genomic datasets.

- Regulatory DNA Variants: These affect elements that control the spatial and temporal expression of genes.

- Promoter Variants: Located near transcription start sites, these can directly alter the binding of the basal transcription machinery.

- Enhancer/Silencer Variants: These can be located vast distances from their target genes and can disrupt the binding of transcription factors, thereby enhancing or repressing gene expression.

- Epigenetic Variants: These can alter the landscape of epigenetic marks, such as histone modifications (e.g., H3K4me3 for promoters, H3K27ac for active enhancers) and DNA methylation, which in turn influences chromatin accessibility and gene expression. For example, H3K4me3 marks in specific cell types like the brain's dorsolateral prefrontal cortex have been shown to be highly enriched for heritability of related traits [18].

- Splicing Variants: Located in intronic regions near exon-intron boundaries (e.g., splice donor and acceptor sites), these variants can disrupt the normal splicing of pre-mRNA, leading to aberrant transcript isoforms.

- Non-Coding RNA Variants: These affect genes that produce functional RNA molecules that are not translated into protein (e.g., microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs), potentially disrupting intricate regulatory networks.

Table 1: Comparative Impact of Coding vs. Non-Coding Variants

| Feature | Coding Variants | Non-Coding Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functional Impact | Alters protein amino acid sequence, structure, and function | Disrupts regulatory logic; modulates gene expression levels, timing, and cell-type specificity |

| Genomic Context | Exons of protein-coding genes | Promoters, enhancers, silencers, introns, non-coding RNA genes |

| Key Annotation Databases | RefSeq, Ensembl, KnownGene, dbNSFP (for functional prediction) | RegulomeDB, ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, GTEx [17] [19] |

| Typical Analysis Approach | Gene-based annotation; impact prediction (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen) | Region-based annotation; overlap with functional genomic marks (e.g., ChIP-seq, DNase-seq) |

| Proportion of GWAS Signals | ~10% | ~90% [17] |

| Example Pathogenic Mechanism | Production of a truncated, non-functional enzyme | Dysregulation of a key developmental transcription factor |

Analytical Approaches and Workflows

Variant Annotation Methodologies

The annotation of coding and non-coding variants requires distinct but complementary methodological approaches, often integrated within a single software pipeline.

- Gene-Based Annotation (for Coding Variants): This approach focuses on relating variants to the genes they affect and the consequent changes to the protein product. Tools like ANNOVAR use databases such as RefGene, KnownGene, and EnsGene to determine whether a variant is exonic, intronic, or intergenic, and to annotate its specific effect (e.g., non-synonymous, stop-gain) [15] [19]. This is coupled with filter-based annotations using databases like dbNSFP that aggregate functional prediction scores from algorithms like SIFT and PolyPhen-2 to assess the potential deleteriousness of missense variants [15].

- Region-Based Annotation (for Non-Coding Variants): This methodology intersects the genomic coordinates of a variant with intervals from functional genomic datasets to infer its potential regulatory role. The RegulomeDB tool, for instance, integrates thousands of datasets from ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, and other consortia, including transcription factor binding sites, chromatin accessibility, and histone modification profiles [17]. It synthesizes this information into a heuristic ranking score (e.g., RegulomeDB Score) that indicates the variant's likelihood of being functional in a regulatory context. A high-ranking variant might lie within a transcription factor binding site in a relevant cell type, suggesting a mechanism for its phenotypic effect.

Integrated Annotation Workflow

A typical variant annotation and prioritization pipeline involves a series of sequential steps, from raw data to a refined list of candidate variants, as visualized below.

Diagram 1: Variant Annotation Workflow

This workflow begins with a Variant Call Format (VCF) file containing the raw genetic variants identified from sequencing. The first critical step is Quality Control & Filtering to remove low-quality calls. The core annotation phase involves parallel or sequential Gene-Based and Region-Based Annotation to characterize each variant. Finally, researchers apply specific Filtering & Prioritization criteria—such as population frequency, predicted functional impact, and inheritance models—to generate a manageable Candidate Variant List for further validation.

Quantitative Functional Architecture

The functional architecture and the strength of natural selection differ markedly between coding and non-coding regions. Heritability partitioning studies reveal how the genetic contribution to traits is distributed across different functional annotations. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from large-scale analyses, such as those performed in the UK Biobank [18].

Table 2: Heritability Enrichment of Low-Frequency and Common Variants

| Functional Annotation | Low-Frequency Variant Heritability | Common Variant Heritability | Implication (Strength of Negative Selection) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-synonymous Coding | 17% ± 1% | 2.1% ± 0.2% | Very Strong |

| Brain DLPFC H3K4me3 (e.g., for Neuroticism) | 57% ± 12% | 12% ± 2% | Strong in specific cell types |

| Other Cell-Type-Specific Non-Coding Annotations | Similarly enriched as common variants for most traits | Baseline for comparison | Moderate to Strong |

The data demonstrates that low-frequency variants are dramatically enriched in functional categories under strong negative selection, such as protein-coding exons. This is because strongly deleterious mutations are kept at low population frequencies by natural selection. The high enrichment of heritability for low-frequency variants in brain-specific epigenetic marks further underscores the cell-type-specific functional importance of the non-coding genome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful variant annotation project relies on a combination of robust software tools, comprehensive databases, and powerful computing resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Variant Annotation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANNOVAR [15] [16] | Command-line Software | Performs fast gene-based, region-based, and filter-based annotations. | A versatile, Perl-based tool; supports local database downloads for high-throughput analysis. |

| wANNOVAR [15] [16] | Web Server | Web-based interface for ANNOVAR functionality. | User-friendly; no command-line skills required; suitable for smaller datasets (<100 MB). |

| ShAn [19] | R Shiny App | Interactive graphical interface harnessing ANNOVAR's engine. | No file size limits; runs on local servers for enhanced data privacy; features a progress bar. |

| RegulomeDB v.2 [17] | Web Server / Database | Annotates and prioritizes non-coding variants. | Integrates ENCODE, epigenomic data, and machine learning scores (SURF) to rank variants. |

| SeattleSeq [19] | Web Server | Provides variant annotation. | Useful for smaller datasets; clinical significance annotation can be limited compared to others. |

| RefSeq / Ensembl [19] | Database | Provides canonical gene models and transcripts. | Used for gene-based annotation to define exons, introns, and UTRs. |

| dbSNP / 1000 Genomes [19] | Database | Catalogues population genetic variation. | Used for filter-based annotation to flag common polymorphisms. |

Experimental Protocols for Variant Annotation

Protocol: Command-Line Annotation with ANNOVAR

This protocol details the steps for annotating a VCF file using the command-line version of ANNOVAR, offering maximum flexibility and power for large datasets [15] [16].

Software and Database Setup:

- Download and install ANNOVAR (a Perl-based tool).

- Download required annotation databases (e.g.,

refGene,avsnp150,gnomad211_genome,dbnsfp35a) to a local directory using theannotate_variation.plscript.

Input Data Preparation:

- Prepare your input file in VCF format generated from your sequencing pipeline (e.g., GATK).

- Ensure the genome build of your VCF file (Hg19/GRCh37 or Hg38/GRCh38) matches the databases you will use.

Run Annotation:

- Execute a command that specifies the input VCF, output file name, and databases. A typical command structure is:

table_annovar.pl <input.vcf> <humandb_directory> -buildver <hg19/hg38> -out <output> -remove -protocol refGene,avsnp150,gnomad211_genome,dbnsfp35a -operation g,f,f,f -nastring . -vcfinput - This performs gene-based annotation with

refGeneand filter-based annotation with the other databases.

- Execute a command that specifies the input VCF, output file name, and databases. A typical command structure is:

Output and Interpretation:

- The main output is a tab-delimited text file or a VCF file with new annotation fields added to each variant.

- Analyze the output by filtering columns based on variant frequency, predicted deleteriousness (e.g., SIFTscore, Polyphen2HDIV_score from dbNSFP), and clinical significance.

Protocol: Interactive Annotation with ShAn

For researchers without a command-line background or those working with sensitive data, ShAn provides an excellent alternative [19].

Application Access:

- Option A: Run ShAn locally on your personal computer by downloading the source code from its GitLab repository and executing it within R.

- Option B: Access a version hosted on a secure institutional server.

Data Upload and Parameter Selection:

- In the ShAn web interface, use the sidebar to upload your VCF file.

- Select the reference genome build (Hg19 or Hg38).

- Choose the annotation type: "gene" (for RefSeq, KnownGene, Ensembl) or "filter" (for population frequency and functional databases).

Execution and Monitoring:

- Initiate the annotation. A progress bar at the lower right corner will show the status in real-time.

- The annotation typically takes 5-30 minutes of compute time, depending on file size.

Result Analysis and Export:

- View the fully annotated variant table directly in the main browser panel.

- Use the interactive table to sort and filter variants.

- Download the final annotated results as a text file for permanent storage and further analysis.

The distinction between coding and non-coding variants is fundamental to genomic medicine. Coding variants, with their direct and often interpretable effects on protein function, have been the traditional focus of research. However, as evidenced by the enrichment of disease heritability in regulatory annotations, non-coding variants represent a vast and complex landscape that controls the intricate circuitry of gene expression. The strength of negative selection acting on these regions, particularly in a cell-type-specific manner, highlights their biological importance [18]. Modern genomic research requires a dual approach: leveraging robust gene-based annotation to understand protein-altering changes and employing sophisticated region-based annotation tools like RegulomeDB to decipher the regulatory code [17]. The availability of diverse tools—from command-line powerhouses like ANNOVAR to user-friendly interfaces like ShAn—ensures that researchers of all computational backgrounds can participate in this endeavor [15] [19]. By integrating these analytical strategies and resources, scientists and drug developers can more effectively prioritize causal variants, elucidate disease mechanisms, and identify novel therapeutic targets across the full spectrum of the human genome.

The functional annotation of genomic variants is a critical step in translating sequencing data into biological and clinical insights. It involves identifying the location and functional consequences of genetic variants, such as their impact on genes, proteins, and regulatory regions. Three tools have become the cornerstone of this process: ANNOVAR, SnpEff, and the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP). While they share a common goal, their methodologies, output formats, and underlying assumptions differ significantly. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these tools, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and implement the appropriate tool for their genomic research projects. Understanding their strengths and limitations is essential, as studies reveal that these tools can show concerning levels of disagreement, with one analysis finding only 58.52% concordance for HGVSc annotations and 65% concordance for Loss-of-Function variants between ANNOVAR and VEP [20] [21].

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of ANNOVAR, SnpEff, and VEP.

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison of Major Annotation Tools

| Feature | ANNOVAR | SnpEff | Ensembl VEP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Gene, region, and filter-based annotation [22] | Variant effect prediction and annotation [23] | Functional effect prediction of genomic variants [24] |

| Input Format | Custom text file (Chr, Start, End, Ref, Obs) [25] | VCF (Variant Call Format) [26] | VCF, HGVS, variant ID [24] |

| Output Format | Tab-separated file [20] | Annotated VCF [20] | Tab-separated, VCF, JSON [24] |

| Annotation Philosophy | Reports single most deleterious effect per variant [20] | Lists all effects for all transcripts [20] | Lists all effects for all transcripts [20] |

| Strengths | Efficient filtering against population databases; diverse annotation types [22] [25] | Extremely fast; high degree of customization; supports over 38,000 genomes [23] [26] | Tight integration with Ensembl resources; regular updates; regulatory region annotation [20] [24] |

A critical differentiator is how each tool handles transcripts. Most genes have multiple transcript isoforms, and a variant may have different consequences depending on the transcript used. SnpEff and VEP provide annotations for every overlapping transcript, offering a comprehensive view. In contrast, ANNOVAR collapses this information to report only the single most deleterious effect based on a predefined priority system [20]. While this simplifies initial filtering, it removes granular data that can be crucial for later analysis, such as when a protocol specifically targets stop-gain variants that may be masked by a higher-priority frameshift annotation [20].

Technical Performance and Discrepancy Analysis

Despite their widespread use, ANNOVAR, SnpEff, and VEP often disagree in their annotations. A 2025 study using 164,549 high-confidence ClinVar variants highlighted substantial discrepancies [21].

Table 2: Annotation Concordance Across Tools (Based on ClinVar Analysis)

| Annotation Type | Overall Concordance | Highest Performing Tool | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| HGVSc (DNA-level) | 58.52% | SnpEff | 0.988 (Match Ratio) |

| HGVSp (Protein-level) | 84.04% | VEP | 0.977 (Match Ratio) |

| Coding Impact | 85.58% | Not Specified | N/A |

The concordance drops dramatically for specific variant types. McCarthy et al. found only about 65% concordance for Loss-of-Function (LoF) variants between ANNOVAR and VEP when using the same transcript set. This figure plummets to 44% when different transcript sets (Ensembl vs. RefSeq) are used with ANNOVAR [20]. These discrepancies arise from several technical factors:

- Non-coding Region Definitions: The tools use different boundaries for non-coding features. For example, SnpEff defines upstream/downstream regions as 5 kb from a transcript, while ANNOVAR's default is 1 kb [20]. When non-coding variants are included, overall concordance between the tools can fall to as low as 49% [20].

- Transcript Sets: The choice of transcript database (e.g., RefSeq, Ensembl, MANE) significantly impacts results [21].

- HGVS Syntax and Alignment: Converting VCF coordinates to HGVS nomenclature involves complex rules, including left-alignment (VCF) versus 3'-alignment (HGVS), which can lead to different representations of the same variant, especially in repetitive regions [21].

- Algorithmic Edge Cases: The tools can produce conflicting annotations for biologically complex variants. For instance, a single-base deletion in a run of thymines might be annotated as a frameshift by Annovar and VEP, but as a more precise stop-gain by SnpEff. Similarly, a variant three bases into an intron might be annotated imprecisely as "intronic" by Annovar, correctly as "spliceregionvariant" by VEP, and incorrectly as "splicesiteacceptor" by SnpEff [20].

Experimental Protocols for Tool Evaluation and Application

To ensure reliable results, researchers should employ systematic protocols for using and validating annotation tools. The following workflow, based on a 2025 benchmarking study, outlines a robust methodology for comparing annotation outputs [21].

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Annotation Concordance

Objective: To quantify the agreement between ANNOVAR, SnpEff, and VEP on a known set of variants.

Methodology [21]:

- Dataset Curation:

- Source: Obtain the latest VCF file of human variants from ClinVar.

- Filtering: Apply stringent filters to create a high-confidence dataset. The 2025 study used 164,549 "two-star" variants from ClinVar.

- Preprocessing: Use

bcftoolsto left-align variants, remove duplicates, eliminate degenerate bases, and normalize the VCF.

- Variant Annotation:

- Software Versions: Use recent versions of all tools (e.g., ANNOVAR, SnpEff 5.2+, VEP 111+).

- Genome Build: Standardize on NCBI GRCh38 (or the latest build).

- Transcript Set: Specify a consistent transcript set (e.g., RefSeq or Ensembl) for all tools. For ANNOVAR, adjust the

upstreamanddownstreamparameters to 5000 bp to match SnpEff's default. - Execution: Run each tool with HGVS output enabled (

-hgvsfor ANNOVAR,--hgvsfor VEP).

- Data Analysis:

- Normalization: Map the specific effect terms from each tool (e.g., "stopgained," "stoplost") to standardized Sequence Ontology terms.

- Comparison: Perform string-match comparisons of the HGVSc and HGVSp strings generated by each tool against the reference ClinVar data and against each other.

- Concordance Calculation: Calculate the percentage of variants for which all tools produce identical HGVS nomenclature and effect predictions.

Protocol 2: Basic Annotation of a Human VCF File

Objective: To functionally annotate a set of human genetic variants called from a sequencing experiment.

Methodology [27]:

- Input Preparation: Start with a VCF file generated from a sequencing pipeline (e.g., after alignment with BWA and variant calling with GATK).

- Tool Execution (Example Commands):

- VEP (Offline with Cache):

- SnpEff (Human Genome):

- ANNOVAR:

- Output Interpretation: Examine the annotated files to identify high-priority variants, such as those with "high" impact in SnpEff, "LoF" predictions, or absence in population frequency databases like gnomAD.

Table 3: Key Resources for Genomic Variant Annotation

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Annotation |

|---|---|---|

| RefSeq & Ensembl Transcripts | Database | Provide the reference gene models to which variants are compared to determine their functional consequence [20]. |

| MANE (Matched Annotation from NCBI and EMBL-EBI) | Transcript Set | A curated set of "default" transcripts that precisely match between RefSeq and Ensembl, designed to reduce annotation ambiguity [21]. |

| ClinVar | Database | A public archive of reports detailing the relationships between human variants and phenotypes, with supporting evidence; used for validation [21]. |

| VCF (Variant Call Format) | File Format | The standard text file format used for storing gene sequence variations [21] [26]. |

| GRCh38 (hg38) | Reference Genome | The primary, maintained reference assembly for the human genome; recommended for all new studies. |

| gnomAD | Database | A resource of population allele frequencies from large-scale sequencing projects; crucial for filtering common polymorphisms [22]. |

| Sequence Ontology (SO) | Controlled Vocabulary | A standardized set of terms and definitions used to describe the effects of sequence variants, promoting consistency [20]. |

Critical Considerations for Clinical and Research Applications

The discrepancies between annotation tools have direct implications for research and clinical diagnostics. Incorrect interpretation of a variant's effect can lead to misclassification.

- Impact on ACMG Classification: The 2025 study demonstrated that discrepancies in LoF annotation directly affect the application of the ACMG/AMP PVS1 criterion (for null variants in disease genes). When tools misannotated a variant's coding impact, it led to the incorrect application of PVS1, which in turn caused 55.9% (ANNOVAR), 66.5% (SnpEff), and 67.3% (VEP) of Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic (PLP) variants to be downgraded, risking false negatives in clinical reports [21].

- Recommendations for Robust Workflows:

- Use the MANE Select Transcript Set: Where available, prioritize annotation based on MANE Select transcripts to standardize the gene model used across tools and institutions [21].

- Cross-validate with Multiple Tools: For clinically significant variants, or those in critical genes, run annotations through at least two tools to identify and manually review discrepancies.

- Leverage Standardized Ontologies: Encourage the use of specific Sequence Ontology terms (e.g.,

five_prime_cis_splice_siteover the more generalsplice_region_variant) to improve communication and reduce ambiguity [20]. - Maintain Updated Software and Databases: The field evolves rapidly. Regular updates of both the annotation tools and the underlying databases (e.g., ClinVar, gnomAD) are essential for accurate results [24] [22].

In conclusion, ANNOVAR, SnpEff, and VEP are powerful and indispensable tools for genomic variant annotation. ANNOVAR excels in database filtering, SnpEff in speed and custom genome support, and VEP in its deep integration with Ensembl's continually updated resources. However, researchers must be acutely aware that these tools are not interchangeable. Their outputs can differ significantly due to fundamental algorithmic and philosophical differences. A rigorous, transparent, and often multi-tool approach is therefore necessary to ensure the accurate interpretation of genomic variants, which forms the foundation for both biological discovery and precision medicine.

Genomic variant annotation represents a foundational step in modern genetics, enabling the translation of raw sequencing data into biologically and clinically meaningful insights. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the strategic use of population and clinical databases is not merely a preliminary step but a critical, ongoing process that directly influences the validity and impact of research outcomes. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for leveraging these essential resources, with a specific focus on ClinVar, a premier public archive of variant interpretations. We will detail the core characteristics of major databases, present integrated workflows for their application, and quantify their performance to equip you with the methodologies necessary for robust genomic research. The subsequent diagram outlines a generalized workflow for integrating these databases into a variant annotation and prioritization pipeline.

Database Fundamentals: Characteristics and Applications

Understanding the scope, data sources, and strengths of each database is crucial for selecting the right resource for a specific research question.

Table 1: Core Genomic Databases for Variant Annotation

| Database | Primary Function & Scope | Key Features & Data Sources | Principal Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClinVar [28] [29] | Public archive of relationships between genomic variants and human health, with expert-curated interpretations. | - Aggregates submissions from clinical & research labs- Uses ACMG/AMP guidelines for classification- Provides review status ("stars") for submissions- Contains germline & somatic variants | - High transparency with submitter identity- Open access and frequently updated |

| HGMD [29] | Commercial database cataloging published disease-associated mutations. | - Curated from scientific literature by dedicated staff- Classifies variants as DM (disease-causing) or DM?- Contains nearly 385,000 DM/DM? variants | - Extensive collection of published variant-disease associations- Useful for initial screening of known pathogenic variants |

| dbSNP [30] | Central repository for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other short genetic variations. | - Assigns unique RS IDs for easy cross-referencing- Contains over 154 million reference variants- Includes population frequency data where available | - Essential for variant normalization and identification |

| gnomAD [22] | Public catalog of human genetic variation from large-scale sequencing projects. | - Provides population allele frequencies from exome and genome data- Includes data from diverse ancestral backgrounds- Flags variants with poor quality or low confidence | - Critical for filtering common variants unlikely to cause rare disease |

Quantitative Analysis of Database Accuracy and Trends

Empirical data on database performance is essential for assessing the reliability of variant interpretations in research. A 2023 study measured the false-positive rates of ClinVar and HGMD over six years, using inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) screened in newborns as a model system [29]. The study utilized samples from the 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) to identify individuals with genotypes classified as pathogenic; due to the rarity of IEMs in this general population, such findings predominantly indicate variant misclassification.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Database Accuracy Over Time (2014-2020)

| Metric | ClinVar | HGMD | Context and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| False-Positive Rate Trend | Significant improvement over time [29] | Improvement over time, but higher baseline [29] | Reflects iterative reclassification and improved guidelines. |

| Implied Disease Burden in 1KGP | Lower implied burden [29] | Two orders of magnitude higher than ClinVar [29] | Suggests more stringent current classification in ClinVar. |

| Variant Reclassification Rate | Sixfold more frequent than HGMD [29] | Lower reclassification rate [29] | Higher ClinVar reclassification may contribute to its improved accuracy. |

| Impact of Ancestral Bias | Reduced bias after excluding common variants [29] | Initially higher false-positive rate for African genomes; mitigated by frequency filtering [29] | Allele frequency databases are critical for correcting ancestral bias. |

Integrated Experimental Protocol for Database Leveragement

This section provides a detailed methodology for integrating population and clinical databases into a variant annotation pipeline, a process critical for studies ranging from rare disease research to polygenic risk assessment.

Protocol: Comprehensive Variant Annotation and Prioritization

Objective: To systematically annotate a set of genetic variants (e.g., from a VCF file) using population and clinical databases, and to prioritize them based on predicted functional impact and disease relevance.

Materials and Reagents:

- Input Data: Variant Call Format (VCF) file from WES/WGS.

- Annotation Software: Ensembl VEP [1] [31] or ANNOVAR [31] [22].

- Filtering & Analysis Tool: SnpSift [23].

- Reference Transcript Set: RefSeq or Ensembl/GENCODE [31].

- Population Frequency Database: gnomAD (via ANNOVAR or VEP plugins) [22].

- Clinical Database: ClinVar (integrated within ANNOVAR/VEP) [28] [22].

- In silico Prediction Tools: CADD, SIFT, PolyPhen-2 (available via dbNSFP in ANNOVAR) [22] [32].

Methodology:

- Variant Effect Prediction: Initiate the annotation process using a tool like ANNOVAR or VEP to map variants to genomic features. A critical first step is the selection of a transcript set (RefSeq or Ensembl), as this choice can lead to discrepant annotations for a significant proportion of variants, including a 44% disagreement for loss-of-function variants [31].

- Population Frequency Filtering: Annotate variants with allele frequency data from gnomAD. The primary goal is to filter out common variants (e.g., MAF > 0.01) that are unlikely to cause highly penetrant rare diseases. This step is crucial for mitigating ancestral bias, as it helps correct for variants that are common in one population but may be misclassified as pathogenic [29].

- Integration of Clinical Evidence: Annotate with ClinVar to identify variants with existing clinical interpretations. Pay close attention to the review status of ClinVar entries (e.g., multiple submitters, expert panel review) as a measure of confidence [28] [29]. Be aware that classifications can change; ClinVar variants are reclassified six times more often than those in HGMD, reflecting an evolving understanding [29].

- Computational Pathogenicity Prediction: Incorporate scores from multiple in silico prediction algorithms (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD) to assess the potential functional impact of missense and other non-truncating variants. These provide supporting evidence for variant prioritization [29] [32].

- Prioritization and Triage: Synthesize the collected evidence to prioritize variants. A typical strategy involves a tiered approach:

- Tier 1 (High Priority): (Likely) Pathogenic variants in ClinVar (with high review status), with low population frequency, and high computational prediction scores.

- Tier 2 (Medium Priority): Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in ClinVar that are predicted to be damaging and are located in genes relevant to the disease phenotype.

- Tier 3 (Low Priority): Benign/likely benign variants or variants with high population frequency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Resources for Genomic Variant Annotation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ANNOVAR [22] | Annotation Software | Performs gene-, region-, and filter-based annotation, enabling functional classification and database integration. |

| Ensembl VEP [1] [31] | Annotation Software | Predicts the functional consequences of variants on genes, transcripts, and protein sequence. |

| SnpEff/SnpSift [23] | Annotation & Filtering | Annotates variant effects and provides tools to filter and manipulate large annotated genomic datasets. |

| LOFTEE [1] | Plugin Tool | Works with VEP to rigorously annotate and quality-control loss-of-function variants. |

| dbNSFP [22] | Aggregated Database | Provides a compiled set of multiple functional predictions (SIFT, PolyPhen, CADD, etc.) for streamlined annotation. |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements, critical challenges remain in the field of variant annotation. A primary issue is annotation inconsistency, which arises from two key variables: the choice of transcript set and the selection of annotation software. Research has shown that using RefSeq versus Ensembl transcripts with the same software (ANNOVAR) resulted in only a 44% agreement for loss-of-function variants and an 83% agreement for all exonic variants [31]. Furthermore, when using the same transcript set (Ensembl) but different software tools (ANNOVAR vs. VEP), the agreement for loss-of-function variants was only 65% [31]. This highlights that variant annotation is not a solved problem and requires careful, conscious selection of pipelines.

The field is rapidly evolving to address these and other challenges. Future directions emphasize:

- Automation and Integration: Developing more efficient, comprehensive, and largely automated systems for annotating both coding and non-coding variants [1] [33].

- Harnessing Non-Coding Regions: Creating methods to exploit information in non-coding regions (promoters, enhancers, non-coding RNAs) to better understand their role in disease [1] [32].

- Improved Diversity: Expanding population databases to include more diverse ancestries is paramount to reducing health disparities and improving the accuracy of variant interpretation for all populations [29].

- Text-Mining for Novel Discoveries: Tools like tmVar 2.0 demonstrate the potential of extracting variant information from the vast biomedical literature, having identified 41,889 RS numbers not found in ClinVar, thus uncovering a wealth of potential novel variant-disease relationships for further investigation [30].

Implementing Annotation Workflows: From Standard Pipelines to Advanced Techniques

The rapid evolution of next-generation sequencing technologies has democratized access to vast amounts of genetic variation data, creating a critical gap between data generation and biological interpretation. For researchers and drug development professionals embarking on genomic variant annotation research, building a standardized analysis pipeline is not merely advantageous—it is essential for producing reproducible, reliable results. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for constructing a robust variant annotation workflow, enabling scientists to transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights that can drive therapeutic discovery and development.

The fundamental challenge in genomic variant analysis lies in the sheer volume of data and the complexity of biological systems. A typical human genome contains 3.5 million genetic variants compared to the reference genome, with each individual carrying 250-300 loss-of-function variants in annotated genes and 50-100 variants previously implicated in inherited disorders [34]. This vast genetic landscape necessitates systematic approaches to identify the handful of clinically or biologically relevant variants among mostly benign background variation. The pipeline described herein addresses this challenge through a structured, multi-tiered methodology that progresses from raw data to prioritized candidate variants.

Core Components of a Variant Annotation Pipeline

Pipeline Architecture and Data Flow

A standard variant annotation pipeline integrates several specialized computational tools and databases in a sequential manner, where the output of each stage becomes the input for the next. The overall architecture follows a logical progression from data quality control through functional annotation to prioritization, with opportunities for iterative refinement at each step. This structured approach ensures that variants are evaluated systematically rather than arbitrarily, reducing the risk of overlooking potentially significant findings or pursuing false leads.

The foundational principle underlying pipeline development is that annotation creates biological context for raw variants. As outlined in genomic visualization research, effective analysis requires "one-dimensional, semantic zooming to show sequence data alongside gene structures" [35], meaning that the pipeline must maintain the connection between individual variants and their genomic context throughout the analysis. This contextual preservation enables researchers to shift seamlessly between big-picture patterns and nucleotide-level details, both of which are essential for accurate biological interpretation.

Table 1: Essential Databases for Genomic Variant Annotation

| Database Category | Examples | Primary Purpose | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Frequency | dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, gnomAD | Determine population frequency and filter common polymorphisms | Population data |

| Functional Prediction | SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD | Predict functional impact of protein-altering variants | Algorithmic scores |

| Gene Annotation | RefSeq, Ensembl, GENCODE | Define gene models and regulatory elements | Gene structure |

| Clinical Association | ClinVar, OMIM, GWAS Catalog | Link variants to known phenotypes and diseases | Clinical knowledge |

| Conservation | PhastCons, GERP++ | Assess evolutionary constraint across species | Evolutionary data |

These databases collectively enable researchers to address critical questions about each variant: Is it common or rare? Does it affect protein function? What gene or regulatory element does it impact? Is it evolutionarily conserved? Has it been associated with disease? The integration of these diverse data types creates a multidimensional profile for each variant that forms the basis for prioritization decisions in both research and clinical contexts.

Step-by-Step Analytical Workflow

Primary Workflow Stages

The variant annotation workflow follows a structured pathway with distinct stages, as illustrated below:

Quality Control and Data Preparation

The initial quality control stage is critical for establishing a reliable foundation for all subsequent analyses. This phase begins with the Variant Call Format (VCF) file generated from sequence alignment and variant calling processes. Key quality metrics include:

- Transition/Transversion (Ti/Tv) ratio: This measure should approximate expected values (~2.0-2.1 for whole exome sequencing), with significant deviations indicating potential technical artifacts.

- Variant concordance with known databases: Comparing your variant set with established resources like dbSNP and HapMap provides a quality baseline.

- Mendelian error rates: For family-based studies, checking inheritance patterns can identify systematic genotyping errors.

- Variant call quality scores: Filtering based on metrics such as QUAL, DP, GQ, and MQ ensures inclusion of high-confidence variants only.

Systematic discounting of erroneous SNPs is challenging because "all quality measures are just proxies because we do not know which variants are real" [34]. Therefore, a balanced approach that removes clear outliers while retaining potentially novel findings is essential. For an average human genome dataset containing approximately 3.5 million SNPs, initial quality filtering typically reduces this number by 10-30%, depending on sequencing quality and stringency of filters applied.

Functional Annotation Methodology

Functional annotation represents the core of the variant interpretation process, where biological context is added to each variant. As demonstrated in protocols for tools like ANNOVAR, this stage typically takes "5-30 minutes of computer time, depending on the size of the variant file, and 5-10 minutes of hands-on time" [16]. The annotation process occurs through three primary mechanisms:

Gene-based annotation focuses on identifying the relationship between variants and gene elements. This includes determining whether variants fall within exonic regions, intronic regions, untranslated regions (UTRs), or intergenic spaces. For exonic variants, further classification includes synonymous versus nonsynonymous changes, stop-gain or stop-loss mutations, and frameshift indications. The impact of protein coding region variants can be profound, including introduction of stop codons, structural disruption, domain disruption, or altered translation efficiency [34].

Region-based annotation examines variants in the context of functionally important genomic regions beyond protein-coding genes. This includes conservation metrics (such as PhastCons and GERP++ scores), regulatory elements (enhancers, promoters, transcription factor binding sites), and chromatin states identified through projects like ENCODE. This dimension is particularly important given that "intergenic variants are also important" as they can "disrupt regulatory elements" and cause "changes in the expression of proteins" [34].

Filter-based annotation focuses on population frequency and clinical associations. This includes identifying variants present in population databases (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes), cataloging variants with known disease associations (ClinVar, OMIM), and flagging variants with predicted functional consequences using algorithms like SIFT and PolyPhen. These tools "assign a pre-computed score that says how likely this substitution is tolerated given the sequence of homologous proteins" or use "machine learning methods predicting the impact of a sequence on the protein's structure" [34].

Visualization and Interpretation Strategies

Genomic Data Visualization Techniques

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex genomic data. Semantic zooming approaches allow researchers to "inspect individual bases that influence the gene structure's believability" while maintaining "a sense of context" [35]. This technique enables seamless transitions between chromosome-level views and nucleotide-level resolution, supporting both broad pattern recognition and detailed mechanistic hypotheses.

Advanced genome browsers implement one-dimensional zooming rather than traditional two-dimensional approaches because "genome browser applications represent a one-dimensional world in that they display location-based features across a single axis defined by the genomic sequence data itself" [35]. This specialized visualization strategy aligns with the intrinsic nature of genomic information, allowing efficient navigation along linear genomes while using the perpendicular axis to represent different annotation tracks or data types.

Color Application in Scientific Visualization

Table 2: Color Palettes for Genomic Data Visualization

| Palette Name | Package | Colorblind-Friendly | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viridis | viridis | Yes | Gradient data (conservation, quality scores) |

| ColorBrewer Qualitative | RColorBrewer | Yes (selected palettes) | Categorical data (variant types, functional classes) |

| Scientific Journal | ggsci | Varies | Publication-ready figures |

| Wes Anderson | wesanderson | No | Presentations and internal reports |

| Grey Scale | ggplot2 | Yes | Black-and-white publication requirements |

Color selection should follow accessibility guidelines to ensure interpretability by all researchers, including those with color vision deficiencies. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) recommend "a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for small text and 3:1 for large text" [36]. Tools like ColorBrewer include integrated "Colorblind Safe" options to simplify this process [37]. The viridis color scales are particularly valuable as they are "printer-friendly, perceptually uniform and easy to read by those with colorblindness" [38].

When creating visualizations, specify colors using hexadecimal RGB notation (e.g., #FF0000 for red) for consistent reproduction across platforms and media [37]. For genomic feature displays, establish consistent color coding across all figures—for example, using the same hue to represent exonic variants regardless of whether they appear in a main analysis figure or supplementary materials.

Implementation with ANNOVAR

Practical Protocol Execution

ANNOVAR provides a representative tool for implementing the annotation workflow described previously. The protocol begins with preparing a VCF file from your sequencing pipeline and proceeds through these concrete steps:

Installation and setup: Download ANNOVAR from its public repository and configure the database paths. The software requires Perl and standard computational resources.

Database downloading: Retrieve relevant annotation databases based on your research focus. For human studies, this typically includes RefSeq gene annotations, dbSNP, population frequency databases, and functional prediction scores.

Annotation execution: Run the annotation command, which follows the syntax:

table_annovar.pl [input.vcf] [humandb/] -buildver hg19 -out [output] -remove -protocol [db1,db2,...] -operation [t1,t2,...] -nastring . -vcfinput. This single command integrates multiple annotation types in a single pass.Output interpretation: The primary output includes a comprehensive table with each variant annotated across all specified dimensions. Additional summary statistics help assess the overall characteristics of the variant set.

This protocol enables "fast and easy variant annotations, including gene-based, region-based and filter-based annotations on a variant call format (VCF) file generated from human genomes" [16]. For non-human species, the process can be adapted through gene-based annotation using orthology relationships or species-specific databases when available.

Web-Based Alternatives

For researchers without computational infrastructure or expertise, web-based tools like wANNOVAR provide accessible alternatives. These platforms "prioritize candidate genes for a Mendelian disease" through user-friendly interfaces that eliminate command-line requirements [16]. The web server approach is particularly valuable for exploratory analyses or researchers transitioning from wet-lab to computational approaches, though it may have limitations for large datasets or proprietary genomic data due to privacy considerations.

Variant Prioritization Framework

Multi-Dimensional Filtering Strategy

Variant prioritization represents the culminating stage where annotated variants are ranked based on their potential biological or clinical relevance. This process employs a structured filtering approach:

This sequential filtering approach progressively reduces variant numbers from millions to a manageable number of high-priority candidates. The specific criteria and thresholds should be established based on the research context—for example, a de novo mutation study would prioritize very rare variants, while a complex disease analysis might consider somewhat higher frequency variants with moderate effect sizes.

Pathway and Network Analysis

Following initial variant prioritization, contextualizing results within biological pathways and networks adds another layer of interpretation. The "one-variant one-phenotype" model is "rather unlikely" for many diseases, making it essential to "prioritize variants or sets of variants to focus analysis on variants likely to be functional [and] involved in the same pathway" [34]. This systems-level approach can identify clusters of related variants that collectively impact biological processes, even when individual variants have modest effects.

Tools that model "disease liability on this subset" represent the cutting edge of statistical genetics, seeking to "find variants with relatively large effect sizes that are able to explain a proportion of disease heritability in the population" [34]. This approach acknowledges the complex genetic architecture of most traits and diseases, where multiple genetic factors interact with environmental influences to determine outcomes.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Variant Analysis