Histone ChIP-seq Background Correction: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Clinical Applications

This comprehensive guide explores background correction and normalization methods essential for accurate histone ChIP-seq data analysis.

Histone ChIP-seq Background Correction: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores background correction and normalization methods essential for accurate histone ChIP-seq data analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of protein-DNA interactions, practical implementation of methods like spike-in normalization and read-depth adjustment, troubleshooting for common experimental artifacts, and validation through benchmarking against established standards. By addressing both theoretical frameworks and practical applications, this resource aims to enhance data reliability for epigenomic studies in basic research and precision oncology.

Understanding Histone ChIP-seq: Why Background Correction Matters in Epigenetic Research

Core Principles of Histone Modifications and Protein-DNA Interactions in ChIP-seq

Troubleshooting Guides

Cross-Linking and Chromatin Fragmentation Issues

Problem: Poor Chromatin Fragmentation or Loss of Signal

Inconsistent or suboptimal chromatin shearing is a primary source of experimental failure in ChIP-seq protocols. The table below outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions:

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smear on agarose gel shows fragments too large (>1000 bp) | Insufficient sonication time or power; over-crosslinking [1] | Optimize sonication cycles; reduce crosslinking time from 30 to 10-20 minutes at room temperature with 1% formaldehyde [1]. |

| DNA appears as a single band at ~150 bp (enzymatic fragmentation) | Chromatin is over-digested by micrococcal nuclease [2] | Reduce amount of micrococcal nuclease used; use ratio of 4x10⁶ cells to 0.5 µl nuclease as a starting point [2]. |

| Low DNA yield after fragmentation | Overly long crosslinking (>30 min) causing difficulty in shearing [1] | Ensure crosslinking does not exceed 30 min; quench with 125 mM glycine [1]. |

| High background noise in sequencing data | Fragmentation conditions dissociate transcription factors from DNA [2] | For transcription factors, use enzymatic digestion or optimized sonication buffers to preserve protein-DNA interactions [2]. |

Antibody and Immunoprecipitation Problems

Problem: High Background or No Specific Enrichment

The specificity of the antibody and the efficiency of immunoprecipitation are critical determinants of ChIP-seq success [3]. The following troubleshooting table addresses common immunoprecipitation failures:

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No enrichment at positive control sites | Antibody not suitable for ChIP; epitope masked by crosslinking [1] | Use ChIP-validated antibodies; if validating, test 0.5-5 µg per IP reaction [2]. |

| High background in negative controls | Non-specific antibody binding; insufficient washing [1] | Include negative controls: non-immune IgG, no-antibody bead control, or peptide-blocked antibody [1]. |

| Low signal for all targets | Insufficient starting chromatin [4] | Use 4x10⁶ cells or 25 mg tissue per IP; for histones, 1x10⁶ cells may suffice [2]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Bead-antibody binding efficiency [2] | Match bead type (Protein A/G) to antibody species and isotype for optimal binding [1]. |

Library Preparation and Sequencing Quality Control

Problem: Failed Quality Metrics in Sequencing Data

After immunoprecipitation, the library preparation and sequencing steps introduce their own quality challenges. Adherence to established quality metrics is essential for robust data interpretation [4] [3].

| Quality Metric | Preferred Value | Problem Indication & Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) [4] | >1% for transcription factors; >30% for histone marks [3] | Value too low: Indicates poor IP enrichment. Re-optimize antibody and crosslinking conditions. |

| Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) [4] | >0.9 | Value too low: Suggests low library complexity from over-amplification. Increase starting chromatin. |

| PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient (PBC) [4] | PBC1 >3; PBC2 >3 | Low PBC: Indicates high duplication from insufficient starting material. Use more cells per IP. |

| Sequencing Depth [4] | 20M reads (narrow marks); 45M reads (broad marks) | Shallow depth: Fails to detect all binding sites. Sequence deeper, especially for broad histone marks. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Experimental Design

What are the essential controls for a rigorous histone ChIP-seq experiment?

According to ENCODE standards, a well-controlled experiment must include [4] [3]:

- Biological Replicates: Minimum of two independent replicates to ensure findings are reproducible.

- Input DNA Control: Chromatin preparation taken prior to immunoprecipitation, with matching cell number, fragmentation, and processing.

- Antibody Validation: Primary (e.g., immunoblot showing a single dominant band) and secondary (e.g., signal loss upon protein knockdown) characterization [3].

- Negative Control IgG: Use of non-immune IgG to establish background binding levels.

How do I choose between sonication and enzymatic fragmentation?

The choice depends on your protein of interest and research goals [2]:

- Sonication: Traditional method, works well for histones and stable proteins. Risk of damaging chromatin and displacing less stable factors.

- Enzymatic Fragmentation (e.g., Micrococcal Nuclease): Gentler, provides better reproducibility for transcription factors and cofactors. Preserves chromatin integrity but over-digestion can lose nucleosome-free regions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

What are the key quality metrics I should check in my processed ChIP-seq data?

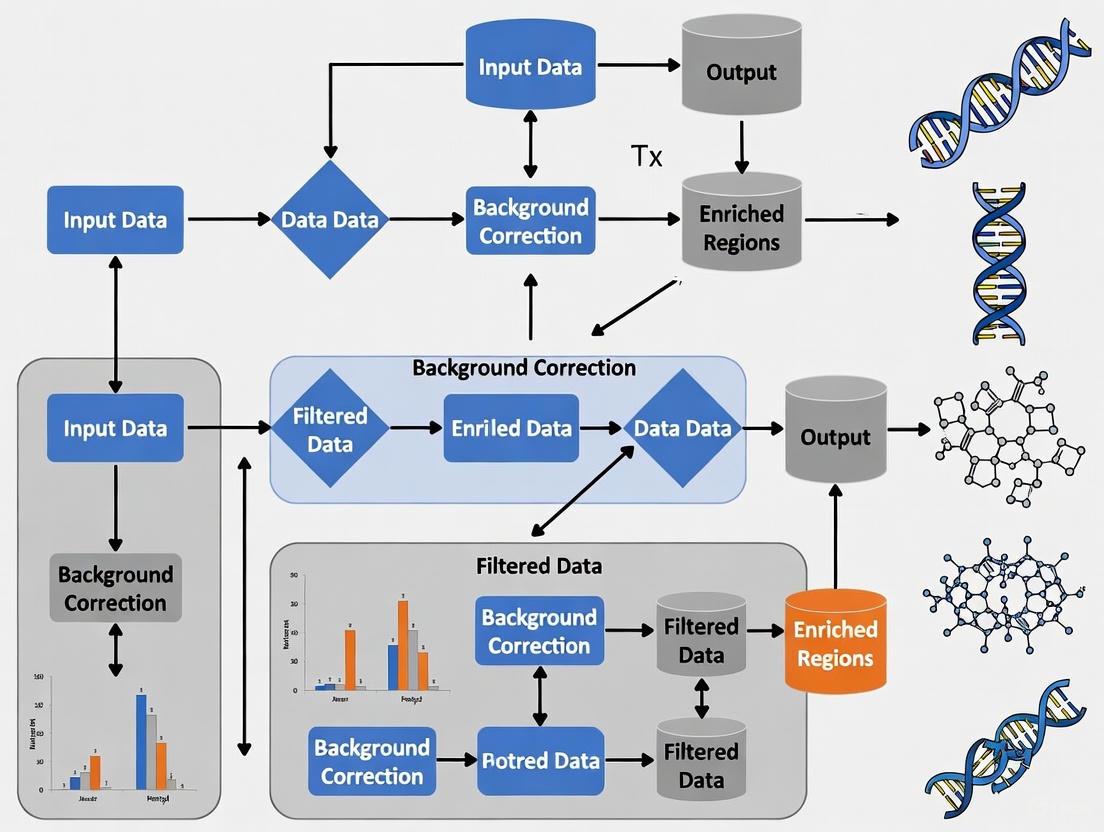

The ENCODE consortium recommends a multi-faceted assessment [4] [3]. The following workflow provides a logical checklist for data quality diagnosis:

How does the intended application influence ChIP-seq experimental design?

Your experimental parameters must align with your biological question [3]:

- Transcription Factor Binding (Point Source): Requires antibodies against sequence-specific factors, ~20 million reads per replicate, and peak callers optimized for sharp, localized signals.

- Histone Modification Mapping (Broad Source): Requires antibodies against specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K36me3), ~45 million reads per replicate, and peak callers that can identify broad domains.

Technical Optimization

My antibody works for Western Blot but not for ChIP. Why?

This common issue arises because the ChIP environment presents unique challenges [1] [3]:

- Epitope Accessibility: Formaldehyde cross-linking can alter protein conformation and mask the epitope recognized by the antibody.

- Chromatin Context: The antibody may not recognize its target when it is bound in the native chromatin structure.

- Solution: Always use ChIP-validated antibodies when available. If you must validate, test multiple antibodies against different epitopes of the same protein.

What is the minimum number of cells required for a successful ChIP-seq experiment?

Standard protocols require millions of cells, but advances have reduced this barrier [5]:

- Standard ChIP: Traditionally requires ~10 million cells.

- Low-Input Protocols: Techniques like Nano-ChIP-seq and LinDA enable successful experiments with 5,000-10,000 cells, particularly for abundant targets like histone modifications.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and materials critical for implementing robust ChIP-seq protocols, as derived from consortium guidelines and technical documentation.

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Technical Specifications & Selection Guide |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Grade Antibody | Specifically enriches target protein-DNA complexes [3] | Must pass primary (immunoblot/immunofluorescence) and secondary (knockdown, peptide competition) validation [3]. |

| Chromatin Fragmentation Reagents | Generates optimally sized DNA fragments (150-900 bp) [2] | Sonication: Requires optimization of time/power. Micrococcal Nuclease: Gentle digestion; ratio of 0.5µl nuclease per 4x10⁶ cells [2]. |

| Magnetic Beads (Protein A/G) | Solid-phase support for antibody immobilization [2] | Prefer magnetic over agarose for ChIP-seq; no DNA blocking agent avoids contamination. Match bead type to antibody species/isotype [1]. |

| Crosslinking Reagent | Preserves in vivo protein-DNA interactions [6] | Fresh 1% formaldehyde for 10-20 min at room temperature. Quench with 125mM glycine [1]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents protein degradation during chromatin prep [1] | Add to lysis buffer immediately before use. Include phosphatase inhibitors if studying phosphorylation [1]. |

| Sequencing Library Prep Kit | Prepares immunoprecipitated DNA for NGS [6] | Must be compatible with low-input DNA (nanogram amounts). Kits with low amplification bias are preferred. |

In histone profiling via Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), distinguishing true biological signal from experimental artifact is crucial for data integrity. Background noise can obscure genuine protein-DNA interactions and lead to erroneous biological interpretations. This guide addresses common sources of artifacts and provides troubleshooting methodologies to enhance the specificity and reliability of your histone ChIP-seq data within the broader context of background correction methods.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Artifacts and Solutions

Background noise in histone ChIP-seq primarily stems from antibody non-specificity, suboptimal chromatin preparation, and inefficient immunoprecipitation. The table below summarizes common issues and their proven solutions.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background (high amplification in no-antibody control) [7] | • Non-specific antibody binding• Insufficient washing• Chromatin over-shearing or under-shearing | • Include a pre-clearing step with BSA/salmon sperm DNA [8]• Increase wash stringency or number of washes [8] [7]• Optimize fragmentation (see below) [9] |

| Low signal or no enrichment [8] | • Insufficient starting material• Incomplete cell lysis• Low antibody affinity or titer• Protein-DNA crosslinking issues | • Increase cell number; use 4x10^6 cells or 25 mg tissue per IP as a starting point [10]• Verify lysis microscopically; use Dounce homogenizer [9] [8]• Use ChIP-validated antibodies; titrate 0.5-5 µg per IP [10]• Optimize crosslinking time (typically 10-30 min) [8] |

| Chromatin over-fragmentation [9] | • Excessive sonication or MNase concentration• Over-digestion to mono-nucleosomes | • For enzymatic protocols: Reduce MNase amount or time [9] [10]• For sonication: Perform a time-course; use minimal cycles [9] |

| Chromatin under-fragmentation [9] [7] | • Insufficient sonication or MNase• Over-crosslinking | • For enzymatic protocols: Increase MNase; perform optimization [9]• For sonication: Conduct a time-course; increase power [9] [7]• Shorten crosslinking time [9] |

How does chromatin fragmentation contribute to artifacts, and how can it be optimized?

Chromatin fragmentation is a critical step where improper handling directly impacts resolution and background. Over-fragmentation can diminish PCR signals, especially for amplicons >150 bp, and disrupt chromatin integrity [9]. Under-fragmentation leads to increased background and lower resolution [9]. The optimal fragment size range is 150–900 base pairs [9] [10].

Optimization Protocol: Enzymatic Fragmentation (Micrococcal Nuclease)

This protocol helps determine the correct amount of Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) for your specific cell or tissue type [9].

- Prepare Cross-linked Nuclei: From 125 mg of tissue or 2 x 10^7 cells.

- Set Up Digestion Series: Aliquot 100 µl of nuclei preparation into 5 tubes.

- Dilute Enzyme: Prepare a 1:10 dilution of MNase stock in Buffer B + DTT.

- Add Enzyme: Add 0 µl, 2.5 µl, 5 µl, 7.5 µl, or 10 µl of the diluted MNase to the respective tubes.

- Digest and Incubate: Incubate for 20 minutes at 37°C with frequent mixing.

- Stop Reaction: Add EDTA to stop digestion and place on ice.

- Purify and Analyze DNA: Pellet nuclei, lyse, reverse cross-links, and run DNA on a 1% agarose gel.

- Determine Optimal Condition: Identify the volume that produces a ladder of DNA fragments between 150–900 bp. The optimal volume for a full-scale IP is 1/10th of this determined volume of stock MNase [9].

Optimization Protocol: Sonication-Based Fragmentation

This protocol determines the optimal sonication time and power [9].

- Prepare Cross-linked Nuclei: From 100–150 mg of tissue or 1x10^7–2x10^7 cells.

- Perform Time-Course Sonication: Sonicate and remove 50 µl aliquots after different time intervals (e.g., after each 1-2 minutes).

- Purify and Analyze DNA: Clarify samples and process the DNA as in the enzymatic protocol. Run on a 1% agarose gel.

- Select Optimal Conditions: Choose the shortest sonication time that generates a DNA smear predominantly below 1 kb. Avoid over-sonication, where >80% of fragments are shorter than 500 bp, as it lowers IP efficiency [9].

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for optimizing both enzymatic and sonication-based chromatin fragmentation:

How critical is antibody selection, and what steps ensure its proper use?

The antibody is arguably the most crucial reagent, as it directly determines specificity. Using non-validated antibodies is a leading cause of failed ChIP experiments [8] [7].

- Selection: Prioritize ChIP-validated antibodies whenever possible [10] [7]. If unavailable, an antibody that works for Immunoprecipitation (IP) is a better candidate than one that does not [10].

- Titration: The recommended amount typically ranges from 0.5 to 5 µg per IP reaction [10]. Always titrate the antibody to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio for your specific conditions.

- Incubation: Performing the immunoprecipitation step overnight at 4°C generally increases both signal and specificity [8] [7].

The decision process for selecting and validating an antibody is outlined below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How much starting chromatin material is needed per IP?

We recommend starting with 4x10^6 cells or 25 mg of tissue per immunoprecipitation (IP), which typically translates to 10–20 µg of chromatin [10]. However, the actual chromatin yield varies significantly by tissue type. The table below provides expected yields from 25 mg of various tissues to help you scale your experiments appropriately [9].

| Tissue / Cell Type | Total Chromatin Yield (per 25 mg tissue) | Expected DNA Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 20–30 µg | 200–300 µg/ml |

| Liver | 10–15 µg | 100–150 µg/ml |

| Kidney | 8–10 µg | 80–100 µg/ml |

| Brain | 2–5 µg | 20–50 µg/ml |

| Heart | 2–5 µg | 20–50 µg/ml |

| HeLa Cells (per 4x10^6 cells) | 10–15 µg | 100–150 µg/ml |

My chromatin fragmentation looks good, but I still get high background. What should I check?

If fragmentation is optimal but background remains high, focus on the immunoprecipitation and washing steps:

- Bead Blocking: Ensure your beads are properly blocked with BSA and salmon sperm DNA to reduce non-specific binding [8].

- Bead Type: Magnetic beads often exhibit lower non-specific binding compared to agarose beads [8]. They are also more suitable for ChIP-seq as they are not blocked with DNA that could contaminate sequencing reads [10].

- Wash Stringency: Increase the number of washes or slightly adjust the salt concentration in the wash buffer (but do not exceed 500 mM NaCl) [8].

- Pre-clearing: Pre-clear your chromatin sample with beads alone to remove fragments that bind non-specifically to the beads [8].

What are the key differences between sonication and enzymatic fragmentation?

The choice between these two core methods can influence your results, especially when studying different chromatin-associated proteins.

| Parameter | Sonication-Based Fragmentation | Enzymatic Fragmentation (MNase) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Uses acoustic energy (shear force) to break chromatin [10]. | Uses Micrococcal Nuclease to cut linker DNA between nucleosomes [10]. |

| Best For | Histones and histone modifications [10]. | Transcription factors and cofactors; provides better reproducibility [10]. |

| Risk of Damage | Can damage chromatin and displace weakly bound factors if over-sonicated [10]. | Gentler; better preserves protein-DNA interactions [10]. |

| Key Consideration | Requires optimization of time/power to avoid over-sonication [9]. | Requires optimization of enzyme-to-cell ratio to avoid over-digestion to mono-nucleosomes [9] [10]. |

Are there advanced methods to quantify and correct for background systematically?

Yes, emerging methods and benchmarks provide paths for better background correction:

- ICeChIP (Internal Standard Calibrated ChIP): This advanced method involves spiking in chromatin with known modifications as an internal standard before IP. It allows for direct measurement of histone modification density on a biologically meaningful scale, enabling unbiased comparisons between experiments and providing an in-situ assessment of immunoprecipitation efficiency and specificity [11].

- Method Benchmarking: Studies systematically compare ChIP-seq with newer techniques like CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN. While CUT&Tag can offer a higher signal-to-noise ratio, it may also have biases, such as a preference for accessible chromatin regions. The choice of method should be tailored to the specific biological question and the type of chromatin-protein interaction being studied [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Histone ChIP-seq | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Validated Antibody | Specifically enriches for the target histone modification or variant. | The most critical reagent; essential for specificity [10] [7]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatically fragments chromatin by digesting linker DNA. | Ratio to cell number must be optimized for each cell/tissue type [9] [10]. |

| Protein G Magnetic Beads | Solid support for capturing antibody-chromatin complexes. | Preferred for low non-specific binding and compatibility with ChIP-seq (no carryover of blocking DNA) [8] [10]. |

| Formaldehyde | Reversible crosslinking agent to preserve protein-DNA interactions in vivo. | Crosslinking time must be optimized (typically 10-30 min) to balance preservation vs. epitope masking [8] [7]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (PIC) | Prevents proteolytic degradation of proteins and histone epitopes during processing. | Cruuble for maintaining sample integrity, especially in complex tissues [9] [8]. |

| Magnetic Separation Rack | Enables efficient separation of beads from supernatant during washing and elution. | Required for use with magnetic beads; allows for complete supernatant aspiration [10]. |

| RNase A & Proteinase K | Enzymes used in post-IP DNA clean-up to remove RNA and proteins, respectively. | Essential for purifying high-quality DNA for sequencing [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the core technical conditions for effective between-sample normalization in ChIP-seq? Three fundamental technical conditions underpin most between-sample normalization methods for ChIP-seq:

- Symmetric Differential DNA Occupancy: The number of genomic regions with increased occupancy should be roughly balanced with those showing decreased occupancy between experimental states [13] [14] [15].

- Equal Total DNA Occupancy: The total amount of DNA occupancy across the genome should be approximately equal between samples [13] [14] [15].

- Equal Background Binding: The level of non-specific, background binding should be consistent across all samples and experimental states [13] [14] [15].

FAQ 2: What happens if the "Symmetric Differential DNA Occupancy" condition is violated? Violating this condition, such as in experiments with a global loss of a histone mark (e.g., after pharmacological inhibition or gene knockout), can severely impact downstream differential binding analysis. Normalization methods that assume symmetric changes will incorrectly normalize the data, leading to a high false discovery rate (FDR). In such scenarios, the majority of peaks may be falsely identified as differentially bound [16].

FAQ 3: How can I achieve reliable results when I'm uncertain which technical conditions are met? When there is uncertainty about which technical conditions hold for your experiment, a robust strategy is to generate a "high-confidence" peakset. This involves running your differential binding analysis with multiple different normalization methods and then taking the intersection of the resulting peaksets. Peaks that are consistently identified across multiple methods are less sensitive to violations of any single method's technical conditions and provide a more reliable basis for biological conclusions [13] [14] [15].

FAQ 4: What is spike-in normalization and when is it particularly useful? Spike-in normalization involves adding a constant amount of exogenous chromatin (from a different species) to each sample as an internal control before immunoprecipitation. It is particularly powerful for experiments where global changes in histone modification levels are expected, as it helps account for variations in antibody efficiency and total chromatin input that read-depth normalization methods miss [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Discovery Rate in Global Knockdown Experiments

Problem: After a global knockdown of a histone mark, your differential analysis flags an unexpectedly high number of peaks, many of which you suspect are false positives. Cause: This is a classic sign of violating the "Symmetric Differential DNA Occupancy" condition. Common normalization methods like TMM or RLE, which assume an equal number of up- and down-regulated peaks, will miscalculate size factors in this scenario [16]. Solution:

- Use Spike-in Normalization: Implement a spike-in method like ChIP-Rx or the PerCell approach. These methods use exogenous chromatin as an internal control to accurately quantify global changes, making them ideal for these conditions [17] [18].

- Generate a High-Confidence Peakset: If spike-in controls were not included, apply multiple normalization methods and use only the differentially bound peaks that are consistently called across all methods for your downstream analysis [13].

Issue 2: Poor Reproducibility and High Background in Tissue Samples

Problem: ChIP-seq data from solid tissues has high background noise and low reproducibility, making normalization unstable. Cause: The dense and heterogeneous nature of solid tissues makes chromatin extraction and fragmentation inefficient, leading to variable background binding and violating the "Equal Background Binding" condition [19]. Solution:

- Optimize Tissue Homogenization: Follow a refined tissue protocol that ensures complete and consistent homogenization. Using a standardized method like the gentleMACS Dissociator or a Dounce grinder on ice can significantly improve reproducibility [19].

- Implement Focused Ultrasonication: Ensure chromatin is sheared to the appropriate size using optimized, focused ultrasonication parameters to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [20].

Issue 3: Choosing the Wrong Normalization Method for Your Histone Mark

Problem: Your differential analysis seems to perform well for some histone marks but poorly for others. Cause: The performance of normalization and differential analysis tools is highly dependent on the shape of the ChIP-seq signal (e.g., sharp peaks for H3K27ac vs. broad domains for H3K27me3) and the biological scenario [16]. Solution: Select your tool based on the peak shape and regulation scenario. The table below summarizes performance recommendations from a comprehensive benchmark study [16].

Table 1: Guide to Optimal Differential ChIP-seq Tool Selection Based on Peak Shape and Regulation Scenario

| Peak Type | Biological Scenario | Recommended Normalization/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor (Sharp) | Balanced (50:50) Change | bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, PePr |

| Sharp Histone Mark (e.g., H3K27ac) | Balanced (50:50) Change | bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, PePr |

| Broad Histone Mark (e.g., H3K27me3) | Balanced (50:50) Change | MEDIPS, PePr |

| Any | Global (100:0) Loss/Gain | Spike-in normalization methods (e.g., ChIP-Rx, PerCell) |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Conditions

Protocol: Validating Equal Background Binding Using Spike-In Controls

This protocol is adapted from the PerCell methodology for quantitative cross-species chromatin sequencing [18].

1. Principle: A defined number of cells from an orthologous species (e.g., Drosophila cells for human samples) are added to your experimental samples in a fixed ratio. The subsequent bioinformatic pipeline uses the reads aligned to the spike-in genome to generate an internal normalization factor that accounts for technical variability in background and efficiency.

2. Key Materials:

- Fixed Ratio of Spike-in Cells: Well-defined cells from an orthologous species (e.g., a 1:10 ratio of Drosophila S2 cells to human cells) [18].

- Antibody: An antibody that robustly recognizes the histone mark in both the target and spike-in species.

- Bioinformatic Pipeline: A pipeline capable of separately aligning reads to the target and spike-in genomes and calculating normalization factors, such as the PerCell Nextflow pipeline [18].

3. Workflow Diagram:

Protocol: Implementing Double-Crosslinking for Challenging Targets (dxChIP-seq)

For histone marks or complexes that are difficult to capture, a double-crosslinking protocol can improve the signal-to-noise ratio, thereby stabilizing background binding [20].

1. Key Reagent:

- Double-Crosslinker Solution: Typically involves a protein-protein crosslinker (e.g., DSG) followed by a protein-DNA crosslinker (formaldehyde) [20].

2. Workflow Overview:

- Step 1: Crosslink protein complexes with a reversible protein-protein crosslinker.

- Step 2: Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde.

- Step 3: Perform chromatin extraction and focused ultrasonication.

- Step 4: Proceed with standard immunoprecipitation, reverse crosslinks, and purify DNA [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq Normalization

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Chromatin/Cells | Provides an internal control for normalization by accounting for technical variation in IP efficiency and sample handling. | Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells for human samples; ensures accurate quantification in global change scenarios [17] [18]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of proteins and histone modifications during tissue/cell preparation. | Added to cold PBS during tissue homogenization to preserve chromatin integrity [19]. |

| Double-Crosslinker Solution | Stabilizes protein-protein interactions prior to protein-DNA crosslinking, improving capture of indirect associations and enhancing signal-to-noise. | Critical for mapping challenging chromatin targets that do not bind DNA directly [20]. |

| MGI-Specific Adaptors | Enables library construction and sequencing on DNBSEQ platforms, a cost-effective alternative for large cohort studies. | Used in refined protocols for solid tissues to facilitate scalable analysis [19]. |

The Impact of Improper Normalization on False Discovery Rates and Biological Interpretation

In histone ChIP-seq research, proper data normalization is not merely a computational step but a fundamental determinant of biological validity. Improper normalization practices systematically distort enrichment measurements, leading to inflated false discovery rates (FDRs) and erroneous biological conclusions. This technical resource center addresses how normalization errors propagate through analysis pipelines, provides troubleshooting guidance for common pitfalls, and outlines rigorous methodologies to ensure the epigenetic landscapes you map accurately reflect biological reality.

Core Concepts: Normalization Errors and Their Consequences

How Normalization Failures Increase False Discoveries

Improper normalization directly inflates false discovery rates through several mechanisms:

Background contamination: When Input DNA is inadequately accounted for, regions with high background signal (e.g., due to open chromatin or high mappability) are misinterpreted as genuine enrichment [21] [22]. One study found that without proper Input control, MACS2 identified false peaks even in pericentromeric regions, which researchers mistakenly interpreted as novel enhancer activation [21].

Insufficient sequencing depth: Inadequate sequencing depth in either IP or Input samples creates sampling artifacts that normalization cannot correct. Analysis shows that when nearly 60% of the genome has zero coverage, true signals become statistically indistinguishable from noise [23].

Inappropriate scaling methods: Simple sequencing depth scaling (SDS) multiplies Input read density by the ratio of total IP-to-Input reads, incorrectly assuming uniform background distribution [22]. This approach artificially inflates background noise in samples with lower IP enrichment, increasing both false positives and false negatives [22].

The following table summarizes the quantitative relationship between normalization errors and their impact on data interpretation:

Table 1: Common Normalization Errors and Their Impacts on Data Quality

| Normalization Error | Effect on False Discovery Rate | Impact on Biological Interpretation | Frequency in Problematic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of inappropriate or missing Input controls | 43% of H3K27ac peaks may be false positives [24] | Claims of novel binding in heterochromatic regions [21] | Common in studies without proper controls [21] |

| Default peak calling parameters | 70-80% peak loss after proper filtering [21] | Misclassification of broad domains as narrow peaks [21] | Very common (>80% of submissions) [21] |

| Failure to account for background components | Specificity reductions of 20-40% [22] | Pathway analyses yield biologically implausible results [21] | Common in non-rigorous pipelines |

| Insufficient sequencing depth | 60% genomic regions with zero coverage [23] | Incomplete mapping of chromatin states | ~30% of datasets [23] |

Critical Normalization Principles for Histone Modifications

Histone modification profiling presents unique normalization challenges distinct from transcription factor ChIP-seq:

Broad vs. narrow domains: Repressive marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 form broad domains spanning hundreds of kilobases, while active marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27ac typically form narrow peaks [21]. Applying narrow peak-calling normalization to broad domains fragments them into hundreds of false narrow peaks, fundamentally misrepresenting their biological nature [21] [24].

Differential background composition: The MARCS project demonstrated that heterochromatic and euchromatic features recruit dramatically different numbers of reader proteins, with euchromatic features (H3ac, H4ac) recruiting many more proteins than heterochromatic features (H3K9me2/3, H3K27me2/3) [25]. Normalization must account for these fundamental differences in background binding propensity.

Combinatorial modification patterns: Histone modifications rarely occur in isolation but form specific combinations that define chromatin states [25] [26]. Normalization approaches must preserve these combinatorial relationships to accurately identify biologically relevant chromatin states defined by multiple modifications [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Normalization Issues

Q1: My negative control regions show enrichment in ChIP-seq. Is this a normalization problem?

This frequently indicates inappropriate normalization or control selection. Specifically:

Problem: Enrichment in negative control regions typically stems from using low-quality input DNA with insufficient coverage, inappropriate control types (e.g., IgG for histone marks), or failure to account for technical artifacts in pericentromeric, telomeric, and other problematic regions [21].

Solution:

- Apply ENCODE blacklist regions during analysis to exclude artifact-prone areas [21]

- Ensure 1:1 or 2:1 ChIP-to-input read ratio for adequate background modeling [21]

- Use GC bias correction methods (e.g., deepTools) when optimal input is unavailable [21]

- Verify your Input DNA quality matches or exceeds your IP samples

Q2: My biological replicates show poor concordance after normalization. What steps should I take?

Poor replicate concordance often indicates hidden technical variability that normalization cannot resolve:

Diagnostic steps:

- Calculate FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) scores for each replicate - successful experiments typically show FRiP > 1% for TFs and >10% for broad marks [21]

- Compute Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) before merging replicates [21]

- Check cross-correlation scores (NSC, RSC) - RSC < 0.5 indicates no enrichment [21]

- Examine duplicate rates - high PCR duplication indicates insufficient library complexity [23]

Corrective actions:

Q3: How does improper normalization specifically affect chromatin state annotations?

Improper normalization distorts the combinatorial patterns of histone modifications that define chromatin states:

Domain misclassification: Normalization errors cause broad heterochromatic domains to appear as fragmented narrow peaks, fundamentally misrepresenting chromatin architecture [21]. In one pediatric cancer study, H3K9me3 analyzed with inappropriate normalization was misinterpreted as discrete heterochromatin islands rather than the actual continuous domains hundreds of kilobases long [21].

Enhancer misassignment: Without proper normalization, enhancer-associated marks like H3K27ac and H3K4me1 show false enrichment, leading to incorrect enhancer identification [26] [24]. Enhancer states show particularly high variability across cell types and are especially vulnerable to normalization artifacts [26].

State transition errors: In time-course experiments studying epigenetic reprogramming (e.g., during infection or differentiation), normalization errors create false chromatin state transitions [24]. During Yersinia infection, proper normalization was essential to distinguish genuine histone modification changes from technical artifacts in approximately 14,500 dynamic loci [24].

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Normalization

Protocol 1: Signal Extraction Scaling (SES) for Histone Modifications

Signal Extraction Scaling provides superior normalization for histone ChIP-seq by specifically normalizing the background component rather than total reads [22]:

Table 2: Reagents for SES Normalization Protocol

| Reagent/Software | Specification | Purpose in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| High-quality Input DNA | 1:1 to 2:1 IP:Input ratio, >10M reads | Background modeling |

| Blacklist regions | ENCODE consensus regions | Exclusion of artifact-prone regions |

| Binning software | Custom scripts or CHANCE | Genome partitioning into fixed windows |

| SES algorithm | Implemented in CHANCE or custom code | Background component identification |

Procedure:

- Genome binning: Partition the reference genome into non-overlapping fixed-width windows (suggested: 1kb bins)

- Count alignments: Count IP and Input alignments within each bin

- Order statistics: Sort IP counts in increasing order, reordering Input counts to match

- Compute cumulative distributions: Calculate partial sums for both IP and Input

- Identify background cutoff: Find the bin cutoff where Input percentage maximally exceeds IP percentage

- Calculate scaling factor: α = cumulative IP background / cumulative Input background

- Apply normalization: Scale Input by α before peak calling

Validation: Successful SES normalization shows proper separation of H3K27me3 broad domains from background, with characteristic domain sizes >100kb and appropriate overlap with repressive chromatin states [21] [26].

Protocol 2: Double-Crosslinking ChIP-seq (dxChIP-seq) for Challenging Targets

For histone marks with indirect chromatin associations, double-crosslinking improves target capture and normalization accuracy [20]:

Crosslinking Procedure:

- Primary crosslinking: Treat cells with 2 mM disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) in PBS for 45 minutes at room temperature

- Secondary crosslinking: Add 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Quenching: Add glycine to 125 mM final concentration, incubate 5 minutes

- Chromatin extraction: Harvest cells, lyse with appropriate buffers

- Focused ultrasonication: Shear chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments

Key advantages for normalization:

- Reduced technical variability between replicates improves normalization consistency

- Enhanced signal-to-noise ratio simplifies background identification

- Better preservation of protein complexes enables more accurate modeling of indirect associations

Visualization of Normalization Concepts

Normalization Workflow Comparison: Problematic vs. Recommended Approaches

This workflow comparison highlights how normalization choices propagate through the entire analytical process, ultimately determining whether biological conclusions reflect reality or technical artifacts.

Research Reagent Solutions for Proper Normalization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Context | Normalization Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Software | CHANCE, deepTools, ChIPQC | Pre-normalization assessment | Identifies biases requiring correction before normalization |

| Peak Calling Algorithms | MACS2 (broad mode), SICER2, SEACR | Histone mark-specific calling | Reduces misclassification of broad domains as narrow peaks |

| Control Resources | ENCODE blacklists, Input DNA standards | Background modeling | Provides reference for artifact exclusion and background estimation |

| Normalization Algorithms | Signal Extraction Scaling, CCAT, SPP | Background-specific scaling | Separates signal from background before normalization |

| Experimental Protocols | Double-crosslinking ChIP-seq [20] | Challenging chromatin targets | Improves signal-to-noise ratio for more accurate normalization |

Advanced Normalization Strategies for Specific Contexts

Normalization in Disease Models

Breast cancer subtype classification relies heavily on epigenetic profiling, where normalization accuracy directly impacts subtype-specific signature identification [26]:

- Subtype-specific chromatin states: Enhancer-associated chromatin states show 41% variability across breast cancer subtypes, requiring careful normalization to distinguish true biological differences from technical artifacts [26]

- Pathway analysis implications: Improper normalization in TNBC cells falsely activated androgen receptor pathways while obscuring vitamin D biosynthesis pathway activity [26]

- Recommended approach: Multi-sample normalization using consensus profiles that account for subtype-specific background characteristics

Normalization in Host-Pathogen Interactions

Infection studies present unique normalization challenges due to pathogen-induced epigenetic remodeling:

- Dynamic range considerations: During Yersinia infection, H3K27ac peaks showed 43% dynamic change, requiring normalization methods capable of handling large-scale epigenomic reorganization [24]

- Time-course normalization: Infection time courses need normalization stable across dramatic chromatin reorganization events

- Cell-type specific backgrounds: Primary human macrophages exhibit different baseline chromatin accessibility than cell lines, necessitating appropriate background models [24]

Proper normalization in histone ChIP-seq requires both computational sophistication and biological awareness. The most effective approaches share these characteristics:

- Biology-aware parameter selection based on the expected chromatin architecture of each histone mark

- Comprehensive quality control before normalization to identify data sets requiring special handling

- Background-specific normalization methods like SES that specifically target non-enriched genomic regions

- Multi-level validation using orthogonal methods to confirm biological conclusions

By implementing these rigorous normalization practices, researchers can dramatically reduce false discovery rates, ensure biological interpretations reflect genuine biology rather than technical artifacts, and build a solid foundation for meaningful epigenetic discovery.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Chromatin Profiling Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | Non-specific antibody binding, contaminated buffers, low-quality Protein A/G beads [27]. | Pre-clear lysate with Protein A/G beads; use fresh, freshly prepared buffers; source high-quality beads [27]. |

| Low Signal/Peak Detection | Excessive sonication, insufficient cell lysis, over-crosslinking, low antibody concentration, low input material [27]. | Optimize sonication to yield 200-1000 bp fragments [27]; ensure complete cell lysis; reduce cross-linking time; increase amount of antibody (e.g., 1-10 µg per IP) and starting material (e.g., 25 µg chromatin per IP) [28] [27]. |

| Poor Replicate Agreement | Variable antibody efficiency, differences in sample preparation, PCR bias [29]. | Standardize protocols; use high-quality, validated antibodies; ensure consistent sample processing. |

| Sparse or Uneven Signal (CUT&Tag/RUN) | Very low background can make weak peaks hard to distinguish [29]. | Perform visual inspection of signal tracks in IGV; merge replicates before peak calling to strengthen signal [29]. |

| Inconsistent Peak Calling | Using a peak caller with incorrect assumptions for the target (e.g., narrow vs. broad marks) [29]. | Select appropriate peak caller and settings (e.g., MACS2 in "broad" mode for H3K27me3); tune parameters carefully [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guide for Histone Modifications (H3K27ac)

| Issue | Specific Consideration | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recall of Known Peaks | CUT&Tag may recover only a subset (~54%) of known ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks, representing the strongest peaks [30]. | Benchmark against established datasets; optimize antibody source and dilution [30]. |

| High Duplication Rate | Excessive PCR cycles during library amplification can lead to high duplicate reads [30]. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles during library preparation from the standard protocol [30]. |

| Antibody Performance | Not all ChIP-grade antibodies perform equally well in CUT&Tag [30]. | Test multiple, validated antibody sources (e.g., Abcam-ab4729, Diagenode C15410196) and titrate dilutions (1:50, 1:100) [30]. |

| HDAC Inhibitor Use | Adding HDAC inhibitors (TSA, NaB) to stabilize acetyl marks in native CUT&Tag conditions did not consistently improve data quality [30]. | Focus optimization efforts on other parameters, such as antibody selection and PCR cycling [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Method Questions

Q1: What are the key advantages of CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN over traditional ChIP-seq? CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN are emerging enzyme-tethering approaches that offer several advantages:

- Lower Input: They require significantly fewer cells (~200-fold less than ChIP-seq) [30].

- Higher Signal-to-Noise Ratio: They produce much less background noise due to in-situ tagmentation and minimal sample handling [30] [12].

- Reduced Sequencing Depth: They can require up to 10-fold less sequencing to achieve robust results [30].

- Adaptability: They are more amenable to single-cell applications [30].

Q2: When should I choose ChIP-seq over CUT&Tag or CUT&RUN? ChIP-seq remains a robust and well-established gold standard with extensive benchmarking data, such as from the ENCODE consortium [30]. It may be preferable when working with certain transcription factors or when a direct comparison to vast existing ChIP-seq datasets is critical.

Q3: How do I fragment chromatin for ChIP-seq, and what is the ideal size? You can use sonication or enzymatic digestion (micrococcal nuclease).

- Sonication: Uses acoustic energy to shear DNA. Ideal fragment size is a smear between 200-1000 base pairs [28]. Over-sonication can damage chromatin and displace proteins.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Uses micrococcal nuclease to cut linker DNA. Ideal fragment size shows a ladder of mono-, di-, tri-nucleosomes (150-1000 bp) [28]. Over-digestion results in only a ~150 bp band.

Experimental Protocol FAQs

Q4: How much antibody should I use for a ChIP experiment? For a standard IP using 4 million cells (10-20 µg chromatin), use 0.5–5 µg of antibody [28]. If an antibody is sold as ChIP-validated, always refer to the manufacturer's datasheet for the recommended amount.

Q5: Why is my ChIP-seq data so noisy, and how can I improve it? High background in ChIP-seq can be caused by several factors [27]:

- Buffers: Use fresh, uncontaminated lysis and wash buffers.

- Beads: Use high-quality, DNA-free Protein A/G magnetic beads to reduce background sequencing reads.

- Sample Pre-clearing: Pre-clear your lysate with beads before adding the antibody to remove nonspecifically binding proteins.

Q6: Why is my CUT&Tag data so sparse, and are these weak peaks real? The low background of CUT&Tag is a double-edged sword. Regions with only 10-15 reads may be false positives [29]. It is essential to:

- Visually inspect the signal tracks in a genome browser like IGV.

- Merge replicates before peak calling to strengthen the signal and improve confidence [29].

Data Analysis FAQs

Q7: Which peak caller should I use for CUT&Tag data or for broad histone marks like H3K27me3? The choice of peak caller and its settings is critical.

- For CUT&Tag: SEACR is a popular choice, but it may over-call weak signal. MACS2 and GoPeaks are also used but require careful parameter tuning [29].

- For Broad Marks: When using MACS2 for marks like H3K27me3 or H3K9me3, always use the

--broadflag. This uses a different statistical model tailored for diffuse enrichment signals [29].

Q8: My replicates don't agree well. What could be the cause? Poor replicate agreement often stems from technical variability [29]:

- Antibody Efficiency: Variable antibody performance between runs.

- Sample Prep: Inconsistencies in chromatin preparation or fragmentation.

- PCR Bias: Differences in library amplification. Ensure consistent protocols and use high-quality reagents.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Performance Comparison of Chromatin Profiling Methods

| Metric | ChIP-seq | CUT&Tag | CUT&RUN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Input Cells | 1 - 10 million [30] | ~200-fold less than ChIP-seq (low input) [30] | Low input [12] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lower, more background [30] [12] | Higher [30] [12] | Higher [12] |

| Recall of ENCODE H3K27ac Peaks | Gold Standard (100%) | ~54% [30] | Information Missing |

| Key Bias | Heterochromatin bias from sonication [30] | Bias towards accessible chromatin regions [12] | Information Missing |

| Single-Cell Applicability | Poorly adapted [30] | Amenable [30] | Information Missing |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Workflow: CUT&Tag for Histone Modifications (e.g., H3K27ac)

This protocol is based on the optimizations described in the benchmarking study [30].

- Cell Preparation and Permeabilization: Harvest and wash K562 cells. Permeabilize the cells to make the chromatin accessible to antibodies.

- Antibody Binding: Incubate permeabilized cells with a primary antibody against the target histone mark (e.g., H3K27ac).

- Antibody Optimization: Test multiple ChIP-grade antibodies (e.g., Abcam-ab4729, Diagenode C15410196) at various dilutions (e.g., 1:50, 1:100) to determine the best signal-to-noise ratio [30].

- HDACi Note: The addition of Trichostatin A (TSA) did not consistently improve data quality for H3K27ac and is not required [30].

- pA-Tn5 Transposase Binding: Add the Protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein, which binds to the primary antibody.

- Tagmentation: Activate the pA-Tn5 with Mg2+. The tethered enzyme will simultaneously cleave DNA and add sequencing adapters ("tagmentation") in situ, targeting only the antibody-bound chromatin.

- DNA Extraction and Purification: Extract and purify the tagmented DNA fragments.

- Library Amplification: Amplify the library using PCR.

- PCR Cycle Optimization: The original protocol's 15 cycles can lead to high duplication rates. Test reducing the number of PCR cycles to maintain library complexity [30].

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform.

Key Reagent Solutions for CUT&Tag Optimization

| Reagent | Function | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac Antibody (e.g., Abcam-ab4729) | Binds specifically to H3K27ac marks. | Critical for success. Use ChIP-grade antibodies and titrate (1:50-1:200) for optimal performance [30]. |

| pA-Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that cleaves and tags target DNA. | The core enzyme for CUT&Tag; ensures targeted tagmentation. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Used in immunoprecipitation. | Magnetic beads are easier to use and do not require a DNA blocking agent, preventing contamination in sequencing [28]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Chromatin Profiling Method Workflows

Relationship: Peak Caller Selection Logic

Implementing Correction Methods: A Practical Guide to Histone ChIP-seq Normalization Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental purpose of spike-in normalization in ChIP-seq experiments?

Spike-in normalization was developed to accurately quantify protein-DNA interactions in cases where the overall concentration of target DNA-associated proteins changes significantly between samples. It uses exogenous chromatin from another species added to each sample prior to immunoprecipitation as an internal control. This approach reduces variability between replicates and captures changes in genome-wide signal intensity that would otherwise be obscured by standard read-depth normalization, which assumes total read count is constant between samples. [17]

When should I use spike-in normalization versus input DNA for normalization?

Spike-in normalization and input DNA normalization serve different functions and are not interchangeable. The table below outlines their distinct purposes:

| Normalization Type | Primary Function | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Normalization | Accounting for global changes in signal between samples (e.g., overall increase in a histone mark). [17] [31] | Comparing samples where the global abundance of the target protein or histone modification is expected to change. |

| Input DNA Normalization | Identifying localized enrichment and controlling for technical biases like open chromatin and background noise. [31] | Peak calling within a condition to distinguish true binding sites from background. |

Spike-in normalization is crucial for detecting an overall increase in a mark like H3K9me3 where the distribution is unchanged, while input normalization is targeted to local differences and helps exclude false-positive peaks. [31]

Improper implementation of spike-in normalization can create erroneous biological interpretations. Common pitfalls include: [17]

- Lack of critical quality control (QC) steps, leading to large variability between the ratios of spike-in to sample chromatin.

- Unsuccessful ChIP of the spike-in itself, which invalidates the control.

- Deviations from original method recommendations, such as using alternative alignment strategies.

- Absence of true biological replicates, which could otherwise reveal unexpected variation.

Which spike-in chromatin and antibodies should I use?

The choice depends on the specific method. Ideal spike-in methods account for as many potential sources of experimental variation as possible. The best strategy uses a spike-in containing the epitope of interest from biological material resembling the sample (e.g., cells or chromatin). [17]

Overview of Common Spike-in Methods: [17]

| Normalization Tool / Method | Source of Exogenous Chromatin | Antibody Strategy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Rx | Biological material (e.g., D. melanogaster) | Common antibody for sample and spike-in | Assumes linear behavior of signal to epitope abundance. |

| Egan et al. | Biological material (e.g., D. melanogaster) | Spike-in specific antibody | Assumes procedures do not affect spike-in and target IP differently. |

| ICeChIP | Synthetic nucleosomes | Common antibody for sample and spike-in | Limited to study of histone marks and common epitope tags. |

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: High Variability in Spike-in Normalization Factors

Possible Causes and Recommendations:

- Cause: Inconsistent spike-in to sample chromatin ratios. The basic assumption of spike-in normalization is that the ratio between the spike-in and sample chromatin is identical between conditions. [17]

- Recommendation: Incorporate proper quality control steps to verify this ratio. Precisely measure the amount of sample chromatin and add a consistent, defined amount of spike-in chromatin to each sample. Do not trust the assumption without QC.

- Cause: Low spike-in read depth. If the number of sequencing reads aligning to the spike-in genome is too low, the normalization factor will be inaccurate. [17]

- Recommendation: Ensure sufficient sequencing depth for the spike-in. One surveyed study had spike-in reads that varied by ~10 fold and were too low for accurate quantification. [17]

- Cause: Inappropriate alignment of sequencing reads. Some studies erroneously align reads to the spike-in and target genomes separately, which can create errors. [17]

- Recommendation: Follow the original alignment recommendations of the chosen spike-in method, which often involve a combined reference genome.

Problem: Poor Chromatin Preparation for Sample or Spike-in

The quality of your starting chromatin is critical for any ChIP-seq experiment, including spike-in protocols. Below are common issues and optimizations.

Expected Chromatin Yields from Different Tissues (for 25 mg tissue or 4x10^6 cells): [32]

| Tissue / Cell Type | Total Chromatin Yield (Enzymatic) | Total Chromatin Yield (Sonication) |

|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 20–30 µg | Not Tested |

| Liver | 10–15 µg | 10–15 µg |

| HeLa Cells | 10–15 µg | 10–15 µg |

| Brain | 2–5 µg | 2–5 µg |

| Heart | 2–5 µg | 1.5–2.5 µg |

- Cause: Concentration of fragmented chromatin is too low. [32]

- Recommendation: If the DNA concentration is low but close to 50 µg/ml, add more chromatin to each IP to reach at least 5 µg. Confirm accurate cell counting before cross-linking and ensure complete cell or tissue lysis by visualizing nuclei under a microscope before and after sonication. [32]

- Cause: Chromatin is under-fragmented. Large chromatin fragments lead to increased background and lower resolution. [32]

- Cause: Chromatin is over-fragmented. [33] [32]

- Recommendation (Enzymatic): If you observe only a single band around 150 bp (mono-nucleosome) on an agarose gel, the chromatin is over-digested. Use less micrococcal nuclease or increase the amount of starting material. [33]

- Recommendation (Sonication): Use the minimal number of sonication cycles required. Over-sonication, where >80% of fragments are shorter than 500 bp, can damage chromatin and lower IP efficiency. [32]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Chromatin | Serves as the internal control for normalization. | D. melanogaster chromatin is commonly used for human samples. Synthetic nucleosomes (e.g., for ICeChIP) are an alternative. [17] |

| Validated Antibodies | Specifically immunoprecipitate the target protein or histone modification. | Use ChIP-validated antibodies when possible. For non-validated antibodies, select ones validated for normal IP and use 0.5–5 µg per IP reaction. [33] |

| Magnetic Beads | Facilitate the immunoprecipitation and washing steps. | Protein G Magnetic Beads are easier to use and better for ChIP-seq than agarose beads because they are not blocked with DNA, preventing contamination of sequencing reads. [33] |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatically fragments chromatin for "Native" or "Enzymatic" ChIP protocols. | Gently fragments chromatin, preserving integrity. Ideal for transcription factors and cofactors. The ratio of MNase to cell number is critical. [33] [34] |

| Spike-in Normalization Kit | Commercial solution providing optimized reagents and protocols. | Active Motif offers a spike-in normalization kit (Cat #61686, #53083) adapted from published methods. [17] |

Experimental Workflow: Implementing a Spike-in ChIP-seq Experiment

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a spike-in ChIP-seq experiment, highlighting stages critical for successful normalization.

Spike-in ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

Detailed Protocol for Key Steps

Chromatin Preparation and Quality Control: Prepare your sample chromatin from cells or tissue, using either sonication or enzymatic digestion (e.g., Micrococcal nuclease) to fragment DNA to an ideal size of 150-900 base pairs. [33] [32] It is critical to run an aliquot of the fragmented chromatin on a 1% agarose gel to confirm the fragment size distribution before proceeding to the IP. [33] This is a key QC check for both your sample and your spike-in chromatin.

Spike-in Addition and Immunoprecipitation: Add a consistent, pre-determined amount of spike-in chromatin to each sample of prepared sample chromatin. [17] Then, perform the immunoprecipitation using an antibody specific to your histone mark of interest. The choice of beads (e.g., magnetic vs. agarose) can impact ease of use and suitability for sequencing. [33]

Sequencing and Bioinformatic QC: After library preparation and sequencing, the first bioinformatic step is to check that the read depth aligning to the spike-in genome is sufficient and consistent across samples. [17] Low or highly variable spike-in reads will lead to an inaccurate normalization factor.

Data Normalization: Use an appropriate computational pipeline (e.g., ChIP-Rx, methods from Bonhoure et al., or tools like

ChIPSeqSpike) to calculate a normalization factor based on the spike-in reads. [17] [31] This factor is then applied to the sample data to correct for global changes in signal. Avoid misaligning reads by using a combined reference genome as the original method specifies植. [17]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental purpose of library size normalization in sequencing experiments? Library size normalization corrects for differences in sequencing depth between samples. When one sample has more total reads than another, non-differentially expressed features will tend to have higher raw counts in that sample, creating a technical bias that must be corrected before meaningful biological comparisons can be made [35] [36].

2. How does TMM normalization work, and what are its key assumptions? The Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method calculates scaling factors to adjust library sizes. It operates on the core assumption that the majority of features (e.g., genes) are not differentially expressed across samples. The method selects one sample as a reference and then, for every other sample, it trims away extreme log fold changes (M-values) and extreme absolute expression levels (A-values). A weighted average of the remaining M-values is then used to compute the scaling factor for that sample [35] [37]. The standard trimming parameters are often set to 30% for M-values and 5% for A-values, though adaptive methods to determine these parameters have been proposed [37].

3. I am using edgeR. How do I obtain TMM-normalized expression values from my count matrix?

According to the edgeR authors, the recommended way to export normalized expression values is to use the cpm() or rpkm() functions on your DGEList object after running calcNormFactors(). It is important to understand that TMM normalizes the library sizes to produce effective library sizes, and the cpm() function uses these effective library sizes to compute normalized counts per million. The concept of "TMM-normalized counts" is somewhat misleading, as the normalization affects the library sizes used in downstream calculations, not the counts directly [38].

4. Why should I avoid subsetting my data before TMM normalization? Subsetting the dataset (e.g., analyzing only a specific set of genes) before normalization can violate the core assumption of TMM that most genes are not differentially expressed. Artificially creating a gene list that is enriched for differentially expressed features can lead to incorrect normalization factors and may cause true biological differences to be normalized away [39].

5. How is normalization for histone ChIP-seq different from RNA-seq? In histone ChIP-seq, standard library size normalization can be problematic because the IP channel is a mixture of specific signal and background noise. Normalizing by total read count can artificially inflate the background. Advanced methods like CHIPIN have been developed that leverage gene expression data, operating on the principle that regulatory regions of genes with constant expression should, on average, show no difference in ChIP-seq signal across samples [40]. Other methods, like Signal Extraction Scaling (SES), aim to normalize the background component of the IP data separately from the enriched signal [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Results After Normalization

Problem: Downstream analysis (e.g., differential expression or binding) yields unexpected or biologically implausible results after TMM normalization.

Solutions:

- Verify Assumptions: Check if the assumption that most features are non-differential holds for your experiment. In cases of global transcriptional shifts or widespread changes in histone marks, TMM's assumptions may be violated [36].

- Inspect Scaling Factors: Examine the TMM scaling factors calculated by

calcNormFactors(). Factors that deviate significantly from 1.0 may indicate a problem with one or more samples. - Consider Alternative Controls: For histone ChIP-seq, if spike-in controls are not available, consider methods like CHIPIN that use genes with invariant expression across conditions to derive a normalization baseline [40].

Issue 2: Confusion About Normalized Count Values in edgeR

Problem: Uncertainty about how to extract and interpret normalized counts from an edgeR analysis pipeline.

Solutions:

- Use

cpm(): As per the developers, to obtain normalized expression values, use thecpm()function on yourDGEListobject after applyingcalcNormFactors(). Specifylog=FALSEto get CPM values normalized by the effective library sizes [38]. - Understand the Output: Recognize that these are not "normalized counts" but rather counts per million mapped reads that have been scaled using the TMM-derived effective library sizes. They are suitable for visualization and inter-sample comparison [38] [35].

Comparison of Normalization Methods

The table below summarizes key read-depth based normalization methods and their characteristics.

Table 1: Common Read-Depth Based Normalization Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Assumptions | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count (TC) | Scales counts by the total number of reads (library size). | The total RNA output (or total IP-able material) is constant across samples. | A simple baseline method; can perform poorly if a few features are highly abundant [37]. |

| Upper Quartile (UQ) | Scales counts using the 75th percentile of counts. | Reduces the influence of very highly expressed features compared to TC. | An improvement over TC when a small subset of features is extremely abundant [37]. |

| TMM | Trims extreme fold-changes and expression levels to compute a robust scaling factor. | The majority of features are not differentially expressed. | Robust between-sample normalization for RNA-seq and other sequencing assays where the core assumption holds [35] [37]. |

| DESeq | Estimates size factors based on the median of ratios of counts to a geometric mean reference. | Similar to TMM, assumes that most features are not DE. | A widely used and robust method for RNA-seq data normalization [37]. |

| SES (ChIP-seq) | Normalizes the Input control to the background component of the IP sample, not the total IP. | The IP sample is a mixture of specific signal and non-specific background. | ChIP-seq normalization to avoid inflating background noise when using an Input control [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Normalization with RNA-seq

This protocol outlines how to perform and assess TMM normalization using gene expression data, a principle that can be extended to other sequencing types.

1. Data Preparation:

- Obtain a raw count matrix from your RNA-seq alignment pipeline (e.g., from HTSeq-count or featureCounts).

- In R, create a

DGEListobject containing the count matrix and sample information.

2. Normalization Execution:

- Apply the TMM method using the

calcNormFactors()function from the edgeR package [38] [39]. - The function will calculate a scaling factor for each sample, which is incorporated into the

DGEListobject as thenorm.factorscomponent.

3. Extraction of Normalized Values:

- Use the

cpm()function, supplying the normalizedDGEListobject, to compute counts per million. The function internally uses the effective library size (original library size * normalization factor) [38]. - For a log-transformed output, which can stabilize variance for visualization, use

cpm(..., log=TRUE).

4. Validation of Results:

- Data Exploration: Create exploratory plots, such as MA plots (log-ratio vs. mean-average) or PCA plots, using the normalized

log-CPMvalues. These plots should ideally show a cloud of non-DE features centered around zero on the log-fold-change axis [35]. - Assumption Check: Investigate whether any known, massive global shifts in expression violate TMM's core assumption. If so, consider alternative strategies, such as using spike-in controls if available [36].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for applying read-depth normalization methods, particularly in the context of a ChIP-seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq Normalization

| Item | Function in Context of Normalization |

|---|---|

| Input (WCE) DNA | A "whole cell extract" control sample. It is sheared chromatin taken prior to immunoprecipitation and is used to estimate the background distribution of reads for ChIP-seq normalization [41] [22]. |

| Spike-in Chromatin | Chromatin from a different organism (e.g., Drosophila) spiked into your samples. It provides an external standard to which signals can be normalized, accounting for differences in ChIP efficiency, and is considered a robust method for cross-sample normalization [40]. |

| Histone H3 Antibody | An alternative control for histone mark ChIP-seq. An H3 pull-down maps the underlying distribution of all nucleosomes, which can be a more appropriate background for normalizing specific histone modifications than WCE [41]. |

| CHIPIN R Package | A computational tool for normalizing ChIP-seq signals across conditions when spike-ins are unavailable. It uses gene expression data to identify invariant genes and normalizes signals in their regulatory regions [40]. |

| deepTools | A suite of computational tools that includes bamCompare and computeMatrix. It can be used for standard read-depth normalization and generating signal profiles, which are useful for both standard analysis and methods like CHIPIN [40]. |

For researchers focusing on histone modifications, automated web-based platforms significantly reduce the technical barriers associated with end-to-end ChIP-seq analysis. These tools are particularly valuable for implementing robust background correction methods, a critical aspect of histone ChIP-seq research. They eliminate the need for local software installation, command-line expertise, and manual file processing, making high-quality epigenomic analysis more accessible to scientists in drug development and basic research [42].

A key platform in this space is H3NGST (Hybrid, High-throughput, and High-resolution NGS Toolkit), a fully automated, web-based system. Its design is especially pertinent for histone mark studies, as it automatically adjusts downstream parameters for optimal analysis of broad histone modification domains. The platform can initiate a complete analysis pipeline—from raw data retrieval to peak annotation—using only a public BioProject accession number, requiring no file uploads or user registration [42].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using a web-based platform like H3NGST over a local installation pipeline for histone ChIP-seq?

Web-based platforms offer several key advantages, especially for researchers who may not have extensive bioinformatics support:

- No Installation or Programming Required: They provide a user-friendly web interface, removing the need for local software installation, dependency management, or command-line skills [42].

- Full Workflow Automation: The entire process, from raw data retrieval via BioProject ID to quality control, alignment, peak calling, and genomic annotation, is automated [42].

- Mobile Accessibility and Ease of Use: Analyses can be initiated and results retrieved through a web browser on various devices, enhancing flexibility [42].

- Built-in Best Practices: These platforms often incorporate established tools and parameters, ensuring high-quality, reproducible results that align with field standards, such as those from the ENCODE consortium [42] [4].

Q2: My histone ChIP-seq experiment yielded very few peaks. What are the common causes and potential solutions?

Low peak enrichment often stems from issues related to experimental execution or data quality:

- Insufficient Sequencing Depth: Histone marks, especially broad ones like H3K27me3, require significant sequencing depth. The ENCODE consortium recommends 45 million usable fragments per replicate for broad histone marks and 20 million for narrow histone marks [4]. Verify that your data meets these targets.

- Poor Antibody Quality or Specificity: The antibody is critical for success. Ensure your antibody has been rigorously validated for ChIP-seq specificity and efficiency. Adhere to characterization standards, such as those provided by the ENCODE consortium [4].

- Suboptimal Peak Calling Parameters: Using peak calling algorithms designed for transcription factors (which produce "narrow" peaks) on histone data (which often produces "broad" domains) can miss true signals. Ensure your platform or pipeline uses appropriate algorithms for histone modifications, such as those in the ENCODE histone pipeline or HOMER with broad peak settings [42] [4].

- Inadequate Quality Control (QC): Check standard QC metrics. A low FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) score indicates poor enrichment. Also, assess library complexity using metrics like Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF > 0.9) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 10) [4] [43].

Q3: When and how should I use spike-in normalization for my histone ChIP-seq data?

Spike-in normalization is a powerful background correction method for assessing global changes in histone mark abundance between samples.

- When to Use: It is essential when your experimental conditions are expected to cause global changes in the total levels of the histone modification you are studying (e.g., comparing cells before and after treatment with a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor) [17].

- How It Works: Exogenous chromatin from another species (e.g., Drosophila) is added to each sample as an internal control before immunoprecipitation. Computational methods then normalize the sample data based on the read counts from this invariant spike-in chromatin [17].

- Critical Pitfalls to Avoid: Our survey of the literature revealed common misuses that can skew results [17]:

- Lack of QC: Failing to ensure consistent spike-in to sample chromatin ratios across experiments.

- Incorrect Alignment: Aligning reads separately to the spike-in and target genomes instead of using a combined reference genome, which can misassign reads.

- Ignoring Replicates: Proceeding without biological replicates, which are necessary to reveal unexpected technical variation.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Issue 1: High Background Noise in Genomic Regions

- Symptoms: A high proportion of reads are located outside of called peaks, leading to a low FRiP score and difficulty distinguishing specific enrichment.

- Solutions:

- Verify Your Input Control: Always use a matched input control (genomic DNA without immunoprecipitation) during peak calling to account for technical and biological background noise [44] [43].

- Filter Blacklisted Regions: Remove signals from "hyper-chippable" regions that produce artifactual signals regardless of the experiment. Standardized blacklists are available for reference genomes like hg38 and mm10 [45].

- Check Cross-Correlation Metrics: Calculate strand cross-correlation. A high-quality ChIP-seq experiment will show a strong correlation peak at a shift distance corresponding to the average DNA fragment length. The NSC (Normalized Strand Cross-correlation) should be > 1.05 and the RSC (Relative Strand Cross-correlation) should be > 0.8, with values above 1 indicating a strong, successful ChIP [45].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

- Symptoms: Poor overlap of peaks called from different biological replicates of the same experiment.

- Solutions:

- Follow Replication Standards: The ENCODE consortium mandates a minimum of two biological replicates for reliable ChIP-seq experiments [4] [43].

- Use IDR for Transcription Factors: For transcription factor data, use the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) framework to identify a consistent set of peaks across replicates. This method is a gold standard in the field [43].

- Assess Replicate Concordance Manually for Histones: For broad histone marks, where IDR is less standard, visualize the signal tracks of replicates in a genome browser (e.g., IGV or UCSC Genome Browser) and calculate Pearson correlations between their genome-wide coverage profiles to quantify reproducibility [42] [30].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized ENCODE Histone ChIP-seq Pipeline The ENCODE consortium provides a uniform processing pipeline specifically for histone modifications, which is suitable for proteins that associate with DNA over extended regions [4].

Table 1: Key Stages in the ENCODE Histone ChIP-seq Pipeline

| Stage | Description | Key Tools/Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Mapping | Aligning sequencing reads to the reference genome. | BWA (Bowtie in older versions) [4] [45]. |

| 2. Signal Track Generation | Creating normalized genome-wide signal tracks. | Fold-change over control and signal p-value tracks in BigWig format [4]. |

| 3. Peak Calling | Identifying significantly enriched regions. | Algorithm optimized for broad domains; relaxed thresholding to feed into replicate analysis [4]. |

| 4. Replicate Concordance | Deriving a final set of reproducible peaks. | For replicated experiments: peaks observed in both true biological replicates or pseudoreplicates [4]. |

| 5. Quality Control | Assessing the overall quality of the experiment. | Library complexity (NRF, PBC), read depth, FRiP score, and reproducibility [4]. |

Spike-in Normalization Protocol for Global Abundance Changes This protocol is critical for accurate quantification when global changes in histone mark levels are expected [17].

- Spike-in Addition: Add a fixed amount of exogenous chromatin (e.g., from Drosophila melanogaster) to each sample chromatin preparation prior to immunoprecipitation.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Proceed with the standard ChIP-seq protocol and sequence the libraries.

- Computational Normalization:

- Alignment: Map all sequencing reads to a combined reference genome containing both the target (e.g., human) and spike-in (e.g., fly) genomes. This is a critical step to avoid misalignment [17].