Homology Modeling Programs in 2025: A Comprehensive Performance Review for Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

This article provides a contemporary analysis of the performance and practical application of homology modeling programs, a cornerstone technique in computational biology.

Homology Modeling Programs in 2025: A Comprehensive Performance Review for Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

Abstract

This article provides a contemporary analysis of the performance and practical application of homology modeling programs, a cornerstone technique in computational biology. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of homology modeling, details the methodologies of leading programs like I-TASSER and Modeller, and offers troubleshooting guidance for common challenges. A central focus is the comparative validation of program accuracy against benchmarks like CASP and specialized datasets, including insights on the integration of deep learning in tools like D-I-TASSER and AlphaFold. The review synthesizes key performance indicators to guide tool selection for specific research scenarios, from membrane protein studies to short peptide modeling.

Homology Modeling Fundamentals: From Core Principles to the Modern Deep-Learning Era

Article Contents

- Introduction: The Enduring Value of a Classic Technique

- Performance Showdown: Homology Modeling vs. Modern Alternatives

- Inside the Black Box: Key Protocols for Robust Modeling

- The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Homology Modeling

- Conclusion: Strategic Role in the Modern Computational Workflow

In the rapidly evolving field of computational structural biology, deep learning-based models like AlphaFold2 have demonstrated unprecedented accuracy, reshaping the landscape of protein structure prediction [1]. Despite this revolutionary progress, homology modeling—a classic computational technique also known as comparative modeling—retains its status as a gold standard for reliable 3D structure prediction, particularly in applications where accuracy, reliability, and experimental concordance are paramount. Homology modeling predicts the three-dimensional structure of a target protein by leveraging its sequence similarity to one or more known template structures [2]. This method is grounded in the fundamental observation that similar sequences from the same evolutionary family often adopt similar protein structures [2] [3].

The reliability of homology modeling is well-established; it is generally accurate when a good template exists, and its computational cost is significantly lower than that of de novo methods [3]. While deep learning excels for proteins without clear homologs, homology modeling remains indispensable for practical applications like drug discovery, where its reliance on evolutionarily conserved structural templates provides a layer of validation that purely algorithmic methods may lack [4] [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of its performance against modern alternatives and details the experimental protocols that underpin its enduring value.

Performance Showdown: Homology Modeling vs. Modern Alternatives

Benchmarking studies consistently show that the practical performance of homology modeling is robust, especially when high-quality templates are available. The following table summarizes a quantitative comparison based on data from recent evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Structure Prediction Methods on a Benchmark of Short Peptides

| Modeling Method | Approach Type | Reported Strength | Notable Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling (MODELLER) | Template-based | Provides nearly realistic structures when templates are available [4]. | Accuracy is highly dependent on template availability and quality [4]. |

| AlphaFold | Deep Learning | Produces compact structures for most peptides [4]. | Can lack the stability of template-based models in molecular dynamics simulations [4]. |

| PEP-FOLD3 | De Novo | Provides compact structures and stable dynamics for most short peptides [4]. | Performance can vary with peptide length and complexity [4]. |

| Threading | Fold Recognition | Complements AlphaFold for more hydrophobic peptides [4]. | Limited by the repertoire of known folds in databases [4]. |

The table reveals that different algorithms have distinct strengths, often dictated by the target's properties. A study on short antimicrobial peptides found that AlphaFold and Threading complement each other for more hydrophobic peptides, whereas PEP-FOLD and Homology Modeling complement each other for more hydrophilic peptides [4]. This suggests an integrated approach, using multiple methods, may be optimal.

Beyond single proteins, homology modeling's principles are being adapted to improve predictions for complexes. For instance, DeepSCFold, a 2025 pipeline for protein complex structure prediction, uses sequence-derived structural complementarity to build better paired multiple sequence alignments. In benchmarks, it achieved an 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and a 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 for CASP15 multimer targets [5]. This demonstrates that the core logic of homology modeling—leveraging evolutionary and structural relationships—continues to drive advances even in the most challenging prediction scenarios.

Table 2: Advanced Complex Prediction Performance (CASP15 Benchmarks)

| Prediction Method | Key Innovation | Reported Improvement | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | Integrates predicted structural similarity & interaction probability into paired MSA construction. | TM-score improved by 11.6% over AlphaFold-Multimer [5]. | Protein complex structure modeling. |

| AlphaFold3 | End-to-end deep learning for biomolecular complexes. | Baseline for comparison [5]. | Complexes of proteins, nucleic acids, ligands. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Extension of AlphaFold2 for multimers. | Baseline for comparison [5]. | Protein-protein complexes (multimers). |

Inside the Black Box: Key Protocols for Robust Modeling

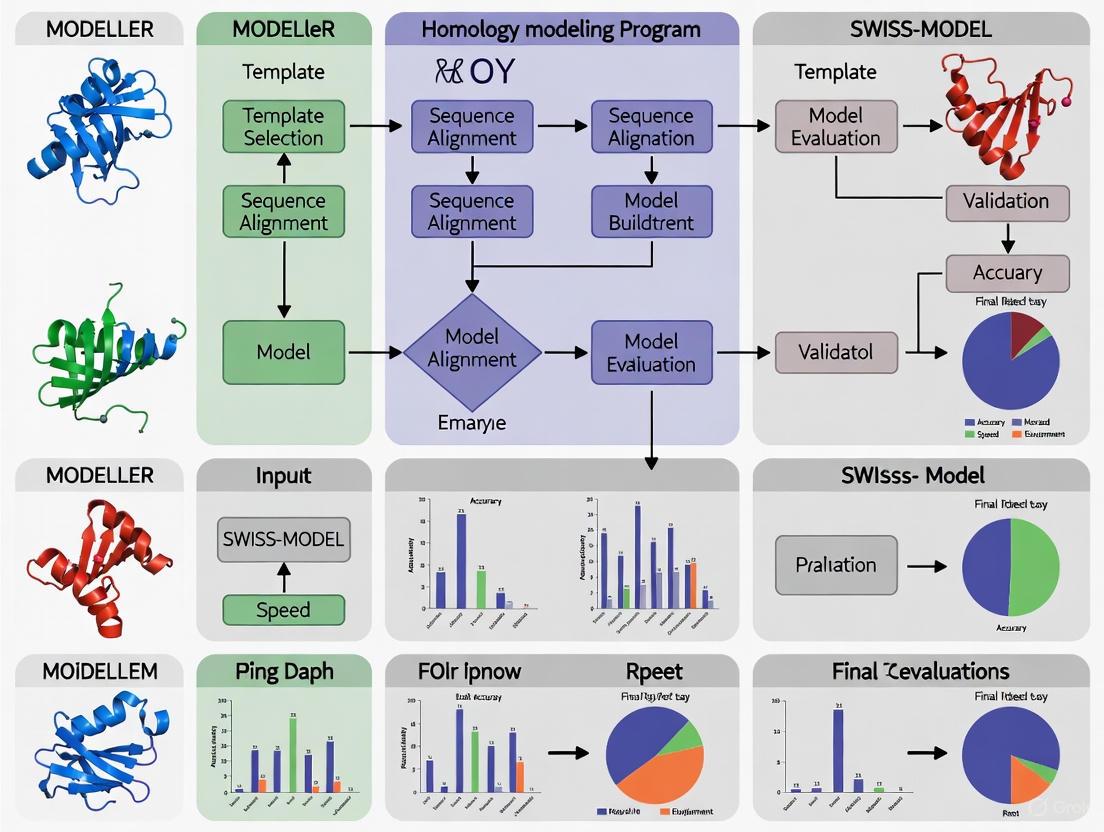

The reliability of homology modeling is underpinned by standardized, rigorous protocols. The following workflow diagram and detailed methodology explain how high-quality models are generated and validated.

Diagram Title: Homology Modeling and Validation Workflow

Core Methodology

The standard workflow, as implemented in tools like MODELLER and the open-source tool Prostruc, involves several key stages [6] [2]:

Template Identification and Sequence Alignment: The target amino acid sequence is used to search for homologous structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) using tools like BLAST. Templates are selected based on sequence similarity (e.g., a minimum identity threshold of 30%) and statistical significance (e.g., e-value cutoff of 0.01) [2]. A pairwise sequence alignment between the target and the selected template is then generated.

Model Building: The alignment and template structure are used to calculate a 3D model for the target sequence. Software like MODELLER implements "comparative protein structure modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints" [6]. Open-source pipelines like Prostruc use engines like ProMod3 to perform this step [2].

Model Refinement and Validation: The initial model often requires refinement, particularly in flexible loop regions. MODELLER, for instance, can perform de novo modeling of loops to improve local accuracy [6]. Finally, the model's quality is rigorously assessed using metrics like:

This protocol ensures that the final model is not just a rough copy of the template, but a refined, physically realistic structure that can be used with confidence in downstream applications.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Homology Modeling

Successful homology modeling relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The table below lists key "research reagents" for a standard modeling project.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for a Homology Modeling Project

| Reagent Solution | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository of experimentally solved 3D structures used for template identification [2]. |

| BLAST (blastp) | Software | Finds regions of local similarity between the target sequence and template sequences in the PDB [2]. |

| MODELLER | Software | Builds 3D models of proteins from sequence alignments by satisfying spatial restraints [6]. |

| SWISS-MODEL | Software | Integrated web-based service for automated comparative modeling [4]. |

| Prostruc | Software | Open-source Python-based pipeline that automates template search, model building, and validation [2]. |

| QMEANDisCo | Validation Tool | Estimates the global and local quality of protein structure models [2]. |

| MolProbity | Validation Tool | Provides all-atom structure validation, checking for steric clashes, rotamer outliers, and geometry [7]. |

| TM-align | Validation Tool | Algorithm for comparing protein structures, calculating TM-score and RMSD [2]. |

In conclusion, homology modeling remains a gold standard not because it outperforms deep learning in every scenario, but because it provides a uniquely reliable and computationally efficient pathway to high-quality structures when suitable templates exist. Its strengths—deep roots in evolutionary principles, a transparent and controllable workflow, and proven performance in critical applications like drug design—ensure its continued relevance.

The future of structure prediction is not a contest between old and new methods, but a strategic integration of their respective strengths. As one review notes, the field has moved from an enduring grand challenge to a routine computational procedure, largely due to AI, but the need for reliable, validated models persists [1]. Homology modeling, especially as implemented in modern, accessible tools, provides a foundational and trustworthy technique that complements the powerful pattern-matching of deep learning, solidifying its place in the modern computational scientist's toolkit.

Homology modeling, also known as comparative modeling, is a foundational computational technique in structural biology that predicts the three-dimensional structure of a protein (the "target") from its amino acid sequence based on its similarity to one or more proteins of known structure (the "templates") [8] [9]. This method operates on the principle that evolutionary related proteins share similar structures, and that protein structure is more conserved than amino acid sequence through evolution [10]. The dramatic increase in sequenced genomes, contrasted with the slower pace of experimental structure determination via X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, has created a significant gap that homology modeling effectively bridges [9] [10]. For researchers in drug discovery and protein engineering, homology modeling provides indispensable structural insights for formulating testable hypotheses about molecular function, characterizing ligand binding sites, understanding substrate specificity, and annotating protein function [10].

The process is inherently multi-staged, requiring sequential execution and optimization of each step to generate high-quality models. The accuracy of the final protein model is directly influenced by the careful execution of each stage and, critically, by the degree of sequence similarity between the target and template proteins. As a general rule, models built with sequence identities exceeding 50% are typically accurate enough for drug discovery applications, those with 25-50% identity can guide mutagenesis experiments, while models with 10-25% identity remain tentative at best [10]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of how popular homology modeling software implements this classical multi-step process, delivering objective performance data to inform researchers' tool selection.

The Classical Multi-Step Process

The homology modeling workflow can be systematically broken down into five sequential steps, each with distinct objectives and methodological considerations [9] [10]. The following diagram visualizes this workflow and the key tools applicable at each stage.

Figure 1: The classical five-step workflow of homology modeling, from target sequence to validated 3D model.

Step 1: Template Identification and Selection

The initial stage involves identifying potential template structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) that show significant sequence similarity to the target sequence [9] [10]. This is typically performed using search tools like BLAST or PSI-BLAST, which identify optimal local alignments [9]. When sequence identity falls below 30%, more sensitive profile-based methods or Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) such as HHsearch and SAM-T98 become necessary to detect distant evolutionary relationships [9] [10]. Template selection requires expert consideration of factors beyond mere sequence similarity, including the template's experimental quality (resolution for X-ray structures), biological relevance, and the presence of bound ligands or cofactors [9].

Step 2: Target-Template Alignment

This critical step aligns the target sequence with the selected template structure(s). Alignment errors remain a major source of significant deviations in comparative models, even when the correct template is chosen [9]. While pairwise alignment methods suffice for high-sequence identity cases, multiple sequence alignments using tools like ClustalW, T-Coffee, or MUSCLE improve accuracy for distantly related proteins by incorporating evolutionary information [10]. The alignment process is often iterative, with initial alignments refined using structural information to correctly position insertions and deletions, typically within loop regions [9].

Step 3: Model Building

With a target-template alignment, the three-dimensional model is constructed using several methodological approaches [10]:

- Rigid-body assembly: Builds the model from conserved core regions of templates, then adds loops and side chains.

- Segment matching: Assembles the model from short, all-atom segments that fit guiding positions from templates.

- Satisfaction of spatial restraints: Generates models by satisfying spatial restraints derived from the template structure, including distances, angles, and dihedral restraints (employed by MODELLER) [8].

- Artificial evolution: Uses an evolutionary operator approach to mutate template residues to the target sequence.

Step 4: Model Refinement

The initial model typically contains structural inaccuracies, particularly in loop regions and side-chain orientations. Refinement employs energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields to remove steric clashes, followed by more sophisticated sampling techniques like molecular dynamics simulations or Monte Carlo methods to explore conformational space around the initial model [10]. This step remains computationally challenging, as it requires balancing extensive conformational sampling with the ability to distinguish near-native structures.

Step 5: Model Validation

The final essential step evaluates the model's structural quality and physical realism using computational checks [10]. This includes:

- Stereochemical quality: Assessing bond lengths, angles, and dihedral distributions using tools like PROCHECK and MolProbity.

- Fold assessment: Verifying the overall fold using knowledge-based potentials in programs like Verify3D and ProSA-web.

- Statistical checks: Identifying outliers in atomic interactions and packing.

Comparative Analysis of Homology Modeling Software

Various software tools automate the homology modeling process with different methodological approaches, accuracy, and usability characteristics. The table below provides a structured comparison of popular tools based on critical performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance comparison of popular homology modeling software tools

| Software | Primary Method | Accuracy (CASP Ranking) | Speed | Optimal Sequence Identity | User Interface | Cost/Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODELLER | Satisfaction of spatial restraints [8] | High [8] | Moderate [8] | Wide range, best >30% [8] [11] | Command-line [8] | Free academic [8] |

| I-TASSER | Iterative threading & assembly refinement [8] | Highest (Ranked #1 in CASP) [8] | Slow [8] | Effective even with low homology [8] | Command-line [8] | Free academic [8] |

| SWISS-MODEL | Automated comparative modeling [8] | High for close homologs [8] | Fast [8] | >30% [8] | Web-based [8] | Completely free [8] |

| Rosetta | Monte Carlo fragment assembly [8] | High [8] | Slow, resource-intensive [8] | Wide range, including ab initio [8] | Command-line & GUI [8] | Academic & commercial licenses [8] |

| Phyre2 | Homology & ab initio recognition [8] | High [8] | Fast [8] | >20% [8] | Web-based [8] | Free [8] |

Key Performance Insights

High-Accuracy Tools (I-TASSER, Rosetta): These methods consistently rank highly in CASP competitions but demand substantial computational resources and expertise [8]. I-TASSER's iterative threading approach proves particularly effective when no close homologs exist, while Rosetta's strength lies in its versatility across homology modeling and de novo design [8].

Balanced Approach (MODELLER): As one of the older, established tools, MODELLER provides an excellent balance of accuracy and flexibility, with extensive customization options through Python scripting. However, it presents a steeper learning curve, making it less accessible to computational beginners [8].

Accessibility-Focused (SWISS-MODEL, Phyre2): These web servers offer user-friendly interfaces and rapid results, making homology modeling accessible to non-specialists. Their automation comes at the cost of limited customization options, and they require stable internet connectivity [8].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Rigorous assessment of homology modeling software relies on standardized experimental protocols that evaluate performance across diverse protein targets. The following diagram illustrates the typical benchmarking workflow used in community-wide evaluations.

Figure 2: Standardized experimental protocol for benchmarking homology modeling software performance.

Benchmark Dataset Construction

Comparative studies typically employ carefully curated benchmark datasets representing various protein families and difficulty levels [11]. These datasets include:

- High-identity targets (>50% sequence identity to templates) to assess performance under ideal conditions.

- Medium-identity targets (30-50%) representing typical modeling scenarios.

- Low-identity targets (<30%) testing the ability to model distant homologs.

- Diverse structural classes (α-helical, β-sheet, mixed) to evaluate method generalizability.

- Specialized targets like membrane proteins or protein-ligand complexes for specific applications [11].

Quantitative Assessment Metrics

Performance evaluation employs multiple complementary metrics:

Global Structure Measures:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures overall Cα atomic distance between model and native structure.

- TM-score: Template Modeling score that provides a more robust global measure, with values >0.5 indicating correct fold and >0.8 indicating high accuracy.

Local Structure Measures:

- Loop RMSD: Specifically assesses accuracy of modeled insertion/deletion regions.

- Side-chain χ-angle accuracy: Evaluates correct placement of rotameric states.

- Interface accuracy: For complexes, measures correct prediction of binding interfaces.

Statistical Analysis:

- Success rates across different sequence identity bins.

- Paired t-tests to determine significant performance differences between methods.

- Correlation analysis between model quality and sequence identity [11].

Table 2: Essential computational resources for homology modeling research

| Resource Category | Tool Name | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Search | BLAST/PSI-BLAST [9] [10] | Identify homologous templates | Web/Standalone |

| HHpred [12] | Remote homology detection | Web server | |

| MUSTER [9] | Thread-based template identification | Web server | |

| Sequence Alignment | ClustalW [9] [10] | Multiple sequence alignment | Web/Standalone |

| T-Coffee [10] | Advanced multiple alignment | Web/Standalone | |

| MUSCLE [9] | Multiple sequence alignment | Web/Standalone | |

| Model Building | MODELLER [8] [12] | Comparative modeling | Standalone |

| I-TASSER [8] [12] | Threading & structure assembly | Web/Standalone | |

| SWISS-MODEL [8] [12] | Automated comparative modeling | Web server | |

| Rosetta [8] [12] | Comparative & de novo modeling | Standalone | |

| Loop Modeling | ModLoop [12] | Loop region modeling | Web server |

| ArchPRED [9] | Loop prediction server | Web server | |

| Side-Chain Modeling | SCWRL [9] | Side-chain placement | Standalone |

| SCRWL [12] | Rotamer-based modeling | Standalone | |

| Model Validation | PROCHECK [9] [10] | Stereochemical quality | Web/Standalone |

| MolProbity [12] | All-atom contact analysis | Web server | |

| ProSA-web [9] | Energy profile validation | Web server | |

| Verify3D [9] | Structure-sequence compatibility | Web server | |

| Model Databases | SWISS-MODEL Repository [12] | Pre-computed models | Database |

| ModBase [12] | Comparative models | Database | |

| Protein Model Portal [12] | Unified model access | Database portal |

The comparative analysis reveals that while high-accuracy tools like I-TASSER and Rosetta consistently perform well in community-wide assessments, the optimal software choice depends heavily on the specific research context [8] [11]. For routine modeling of close homologs (>30% sequence identity), automated servers like SWISS-MODEL and Phyre2 provide excellent accuracy with significantly reduced time investment [8]. Conversely, for challenging targets with low sequence identity or specialized requirements like protein-ligand complexes, the advanced sampling and customization capabilities of MODELLER and Rosetta become indispensable despite their steeper learning curves [8] [13].

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning methods. Recent advances in contact prediction using deep neural networks have significantly enhanced the accuracy of template-free modeling [14]. Furthermore, the development of AlphaFold2 and its derivatives represents a paradigm shift in protein structure prediction, although traditional homology modeling remains crucial for many applications, particularly when experimental templates exist or when studying specific conformational states [5]. The emerging trend of combining collective intelligence initiatives like CASP, Folding@Home, and RosettaCommons with machine learning approaches continues to push the boundaries of what's achievable in computational protein structure prediction [14].

For researchers, this comparative analysis underscores the importance of selecting homology modeling software based on specific project requirements, considering the trade-offs between accuracy, computational resources, and usability. The experimental protocols and benchmarking data provided here offer a foundation for making informed decisions in tool selection and implementation for drug discovery and protein engineering applications.

The field of protein structure prediction has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the integration of deep learning methodologies. For decades, the scientific community grappled with the protein folding problem—predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence—an challenge that remained largely unsolved for over 50 years [15]. Traditional approaches relied heavily on physical force field-based simulations or homology modeling, which often struggled with accuracy, particularly for proteins without close evolutionary relatives in structural databases [16] [17]. The advent of AlphaFold marked a watershed moment, demonstrating that artificial intelligence could achieve accuracy competitive with experimental methods [15]. Subsequent developments, including the hybrid approach D-I-TASSER, have further advanced the field by integrating deep learning with physics-based simulations, creating a new paradigm for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals [17] [18].

This comparative guide examines the performance, methodologies, and applications of these two leading approaches—AlphaFold and D-I-TASSER—within the broader context of homology modeling programs. By presenting objective experimental data and detailed protocols, we provide researchers with the analytical framework needed to select appropriate tools for their specific structural biology and drug discovery projects.

Methodology and Technological Innovation

AlphaFold: End-to-End Deep Learning Architecture

AlphaFold employs a novel end-to-end deep learning approach that directly predicts the 3D coordinates of all heavy atoms for a given protein using primarily the amino acid sequence and multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of homologs as inputs [15]. Its architecture consists of two main components: the Evoformer and the structure module. The Evoformer is a novel neural network block that processes inputs through attention-based mechanisms to generate both an MSA representation and a pair representation that encodes relationships between residues [15]. The structure module then introduces an explicit 3D structure using rotations and translations for each residue, rapidly refining these from an initial trivial state into a highly accurate protein structure with precise atomic details [15]. A key innovation is "recycling," an iterative refinement process where outputs are recursively fed back into the network, significantly enhancing accuracy [15].

D-I-TASSER: Hybrid Integration Approach

D-I-TASSER represents a hybrid methodology that combines multi-source deep learning potentials with iterative threading assembly simulations [17]. Unlike AlphaFold's end-to-end learning, D-I-TASSER employs replica-exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) simulations to assemble template fragments from multiple threading alignments guided by a highly optimized deep learning and knowledge-based force field [17]. A distinctive innovation is its domain splitting and assembly module, which iteratively creates domain boundary splits, domain-level MSAs, and spatial restraints, enabling more accurate modeling of large multidomain proteins [17] [18]. This approach allows the implementation of full physics-based force fields for structural optimization alongside deep learning restraints [18].

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison

| Feature | AlphaFold | D-I-TASSER |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | End-to-end deep learning | Hybrid deep learning & physics-based simulation |

| Key Innovation | Evoformer block & structure module | Domain splitting & replica-exchange Monte Carlo |

| MSA Utilization | Integrated via attention mechanisms | DeepMSA2 with meta-genomic databases |

| Refinement Process | Recycling (iterative network refinement) | Iterative threading assembly refinement |

| Multidomain Handling | Limited specialized processing | Dedicated domain partition & assembly module |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for both AlphaFold and D-I-TASSER, highlighting their distinct approaches to protein structure prediction:

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Single-Domain Protein Prediction Accuracy

Rigorous benchmarking against established datasets provides critical insights into the relative performance of these platforms. In assessments using 500 non-redundant "Hard" domains from SCOPe, PDB, and CASP experiments (with no significant templates detected), D-I-TASSER achieved an average TM-score of 0.870, significantly outperforming AlphaFold2.3's TM-score of 0.829 (P = 9.25 × 10⁻⁴⁶) [17]. The performance advantage was particularly pronounced for difficult targets where at least one method performed poorly, with D-I-TASSER achieving a TM-score of 0.707 compared to AlphaFold2's 0.598 (P = 6.57 × 10⁻¹²) [17]. This trend persisted across multiple AlphaFold versions, with D-I-TASSER maintaining superiority over AlphaFold3 (TM-score: 0.870 vs. 0.849) [17].

Table 2: Single-Domain Protein Prediction Performance

| Method | Average TM-score | Fold Coverage (TM-score >0.5) | Hard Target Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-I-TASSER | 0.870 | 480/500 (96%) | 0.707 |

| AlphaFold2.3 | 0.829 | 452/500 (90%) | 0.598 |

| AlphaFold3 | 0.849 | 465/500 (93%) | 0.634 |

| C-I-TASSER | 0.569 | 329/500 (66%) | N/A |

| I-TASSER | 0.419 | 145/500 (29%) | N/A |

Multidomain Protein Modeling Capabilities

Multidomain proteins present unique challenges as they constitute approximately two-thirds of prokaryotic and four-fifths of eukaryotic proteins, executing higher-level functions through domain-domain interactions [17]. D-I-TASSER's specialized domain-splitting protocol provides significant advantages in this arena. On a benchmark set of 230 multidomain proteins, D-I-TASSER produced full-chain models with an average TM-score 12.9% higher than AlphaFold2.3 (P = 1.59 × 10⁻³¹) [17]. In the blind CASP15 experiment, D-I-TASSER achieved the highest modeling accuracy in both single-domain and multidomain structure prediction categories, with average TM-scores 18.6% and 29.2% higher than AlphaFold2 servers, respectively [17].

Limitations and Specialized Application Performance

Despite their impressive capabilities, both platforms exhibit specific limitations. AlphaFold models have shown inconsistent performance in docking-based virtual screening, with "as-is" AF models demonstrating significantly lower performance compared to experimental PDB structures for high-throughput docking, even when the models appear highly accurate [19]. Small side-chain variations in binding sites can substantially impact docking performance, suggesting post-modeling refinement may be crucial for drug discovery applications [19]. Additionally, AlphaFold struggles with certain protein complexes, showing particularly low success rates for antibody-antigen complexes (11%) and T-cell receptor-antigen complexes [20].

D-I-TASSER, while demonstrating superior performance in many benchmarks, remains dependent on the quality of multiple sequence alignments. Proteins with shallow MSAs, particularly those from viral genomics with rapidly evolving sequences and broad taxonomic distribution, present ongoing challenges [18]. Furthermore, neither system currently provides comprehensive solutions for predicting protein-protein complexes, representing a significant area for future development [18].

Research Applications and Practical Implementation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Open access to ~200 million protein structure predictions | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [21] |

| D-I-TASSER Server | Modeling Suite | Hybrid deep learning/physics-based structure prediction | https://zhanggroup.org/D-I-TASSER/ [17] |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Experimental protein structures for validation | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| DeepMSA2 | Algorithm | Constructing deep multiple sequence alignments | Integrated in D-I-TASSER pipeline [17] |

| pLDDT | Metric | Local confidence measure for AlphaFold predictions | Provided with AlphaFold models [22] |

| TM-score | Metric | Global structural similarity metric | Used for model quality assessment [17] |

Experimental Protocol for Method Evaluation

Researchers conducting comparative assessments of protein structure prediction methods should adhere to standardized protocols to ensure reproducible results. For benchmark dataset construction, curate non-redundant protein sets with known experimental structures, ensuring no significant homology between test cases and training data (suggested sequence identity cutoff <30%) [17]. Include representatives from different structural classes and complexity levels (single-domain, multidomain). For model generation, run each method with default parameters, generating multiple models (typically 5) per target when possible. For accuracy assessment, utilize multiple complementary metrics: TM-score for global fold accuracy [17], RMSD for local atomic precision [22], and CAPRI criteria for protein complexes [20]. Additionally, compare models with experimental electron density maps where available to minimize potential biases in deposited PDB structures [22].

Application in Drug Discovery Pipeline

In structure-based drug discovery, the quality of predicted structures at binding sites is paramount. Studies evaluating AlphaFold models for docking-based virtual screening revealed that despite high global accuracy, the performance in high-throughput docking was consistently worse than using experimental structures across four docking programs and two consensus techniques [19]. This highlights the critical importance of binding site refinement when using AI-predicted models for virtual screening. Researchers should pay particular attention to side-chain conformations in binding pockets and consider targeted refinement using molecular dynamics or energy minimization before proceeding with docking studies [19].

The revolutionary impact of deep learning on protein structure prediction has created unprecedented opportunities for structural biology and drug discovery. Both AlphaFold and D-I-TASSER represent monumental achievements in the field, each with distinctive strengths and limitations. AlphaFold provides an exceptionally efficient, end-to-end solution with remarkable accuracy across broad protein families, while D-I-TASSER's hybrid approach offers superior performance particularly for challenging targets, multidomain proteins, and cases with limited evolutionary information.

For the research community, selection between these platforms should be guided by specific project requirements. For rapid proteome-scale annotation and general structural hypotheses, AlphaFold's extensive database and speed are advantageous. For detailed mechanistic studies, particularly involving multidomain proteins or difficult targets without close homologs, D-I-TASSER's enhanced accuracy may justify the additional computational requirements. Critically, both systems produce valuable hypotheses rather than definitive replacements for experimental determination [22], and researchers should consider confidence metrics and, where possible, experimental validation for structural details relevant to their specific biological questions.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of deep learning with physics-based simulations exemplified by D-I-TASSER points toward a promising future where the respective strengths of both approaches can be leveraged to address remaining challenges, including the prediction of protein complexes, conformational dynamics, and the effects of ligands and post-translational modifications.

In template-based protein structure prediction, or homology modeling, the accuracy of the generated 3D model is fundamentally linked to the evolutionary relationship between the target protein and the template structure. Sequence identity, which quantifies the percentage of identical amino acids in the aligned regions of two protein sequences, serves as a primary indicator of this relationship and a powerful predictor of final model quality. Understanding this relationship is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on computational models for tasks ranging from functional annotation to drug docking studies. This guide objectively compares the performance of different homology modeling methodologies by examining how their accuracy varies with sequence identity, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols from benchmark studies.

The Sequence Identity-Accuracy Relationship: Quantitative Analysis

Performance of Alignment Method Categories

A comprehensive benchmark study assessed 20 representative sequence alignment methods on 538 non-redundant proteins, categorizing targets by difficulty based on the confidence of template detection. The quality of the resulting structural models was measured by TM-score, a metric that quantifies structural similarity (where a score >0.5 indicates the same fold, and a score closer to 1 indicates higher accuracy). The following table summarizes the performance of different categories of alignment methods [23]:

| Alignment Method Category | Average TM-score | Relative Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Profile-Profile Alignment | 0.297 | Baseline |

| Sequence-Profile Alignment | 0.234 | 26.5% lower than Profile-Profile |

| Sequence-Sequence Alignment | 0.198 | 49.8% lower than Profile-Profile |

The data demonstrates the dominant advantage of profile-profile alignment methods, which leverage evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of both the target and template, resulting in models with significantly higher average TM-scores.

Model Accuracy Across Target Difficulty and Sequence Identity

The benchmark further revealed that model accuracy is highly dependent on the "difficulty" of the target, which is intrinsically linked to the available sequence identity between the target and the best possible template [23]:

| Target Difficulty | Description | Approx. Sequence Identity Range | Average TM-score (Best Methods) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Strong template hits detected by all threading programs | Higher | ~0.7 - 0.9 |

| Medium | Limited or weaker template hits | Medium | ~0.4 - 0.6 |

| Hard | No strong template hits detected by any program | Low (<15-20%) | ~0.3 - 0.4 |

For Hard targets, which typically have sequence identities below 15-20% to their best templates, the TM-scores from even the best profile-profile methods remain around 0.3-0.4. This is 37.1% lower than the accuracy achieved by a pure structure alignment method (TM-align), indicating that the fold-recognition problem for distant-homology targets cannot be solved by sequence alignment improvements alone [23].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Modeling Accuracy

Standardized Benchmarking of Alignment Methods

The quantitative data presented above was derived from a rigorous benchmark designed to ensure a fair comparison among methods [23]:

- Dataset: 538 non-redundant proteins with pair-wise sequence identity <30% were randomly collected from the PDB. The set was balanced to include 137 Easy, 177 Medium, and 224 Hard targets.

- Template Library: A uniform template library was constructed for all tested methods using a non-redundant set of PDB proteins with a pair-wise sequence identity cutoff of 70%, ensuring all methods were searching the same structural space.

- Evaluation Protocol: For each target protein, each alignment method was used to identify a template and generate a sequence-structure alignment. A 3D model was built by copying the coordinates from the template based on this alignment. Model quality was assessed by comparing the predicted model to the experimentally solved native structure using TM-score and RMSD.

Benchmarking Advanced Deep Learning Methods

Recent methods like DeepSCFold and DeepFold-PLM are evaluated through community-wide blind assessments like CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction). The protocol for DeepSCFold is illustrative of this process [5]:

- Dataset: The method is tested on multimeric targets from the CASP15 competition and on antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database.

- Temporal Holdout: For CASP15, complex models are generated using protein sequence databases available only up to May 2022, ensuring a temporally unbiased assessment of predictive capability.

- Comparison to State-of-the-Art: Predictions are compared against those from other top methods, such as AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, which are either retrieved from the official CASP website or generated via their online servers.

- Accuracy Metrics: For global structure accuracy, TM-score improvement is reported. For binding interfaces, the success rate of predicting antibody-antigen interfaces is measured.

Visualizing the Workflow for Determining Model Accuracy

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key factors involved in establishing the relationship between sequence identity and model accuracy, as implemented in the benchmark studies.

To conduct rigorous comparisons of homology modeling programs, researchers require a suite of computational tools, datasets, and metrics. The table below details key resources referenced in the featured experiments.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| CASP Datasets [5] [24] | Benchmark Dataset | Provides standardized, blind test sets for evaluating the accuracy of protein structure prediction methods. |

| SAbDab [5] | Specialized Database | A database of antibody-antigen complexes used for testing performance on challenging interfaces with low co-evolution. |

| TM-score [23] | Assessment Metric | A metric for measuring the structural similarity of two protein models, more robust than RMSD for global fold assessment. |

| MMseqs2 [24] | Software Tool | A fast and sensitive tool for generating multiple sequence alignments (MSAs), used for constructing profile inputs. |

| JackHMMER [24] | Software Tool | A profile HMM-based tool for deep homology search, used for constructing MSAs in standard AlphaFold pipelines. |

| UniRef50 [24] | Sequence Database | A clustered set of protein sequences from UniProt, used for MSA construction and profile generation. |

| PDB70 [24] | Template Library | A curated subset of the PDB with maximum 70% sequence identity, used for template-based structure prediction. |

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biennial community experiment that objectively evaluates the state of the art in protein structure modeling. The CASP16 assessment, conducted in 2024, demonstrates that deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold-based systems, continue to dominate protein structure prediction. However, significant challenges remain in accurately modeling protein complexes, especially antibody-antigen interactions, higher-order oligomers, and complexes involving nucleic acids or small molecules. This assessment reveals that while monomer domain prediction has reached high reliability, key frontiers for development include effective model ranking strategies, stoichiometry prediction, and specialized approaches for difficult targets that evade standard AlphaFold-based pipelines.

CASP16 Experimental Design

CASP16 introduced several innovative experimental phases designed to address specific challenges in protein complex prediction:

- Phase 0: Required predictors to model protein complexes without prior knowledge of stoichiometry, simulating real-world scenarios where complex composition is unknown [25].

- Phase 1: The standard assessment where stoichiometry was provided to participants, enabling evaluation of modeling accuracy under ideal conditions [25].

- Phase 2: Provided predictors with thousands of pre-generated models from MassiveFold (typically 8,040 per target) to accelerate progress in model selection and quality assessment methods, particularly for resource-limited groups [25].

Additionally, CASP16 introduced a "Model 6" submission category that required all participants to use multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) generated by ColabFold, enabling researchers to isolate the influence of MSA quality from other methodological advances [25].

Assessment Metrics and Targets

The assessment employed multiple quantitative metrics to evaluate prediction accuracy:

- Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1): Measures accuracy at protein-protein interfaces [25]

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): Evaluates local structure quality [25]

- Template Modeling (TM)-score: Assesses global fold similarity [5]

- DockQ: Quantifies interface quality in protein complexes [25]

The CASP16 oligomer prediction category included 40 targets in Phase 1, comprising 22 hetero-oligomers and 18 homo-oligomers [25]. More than half (21 of 40) of the target structures were determined by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), with the remainder solved by X-ray crystallography [25]. The target set included particularly challenging categories such as antibody-antigen complexes, host-pathogen interactions, and higher-order assemblies.

Performance Comparison of Leading Methods

Quantitative Assessment of Protein Complex Prediction

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Leading Methods on CASP15-CASP16 Targets

| Method/Pipeline | Core Approach | TM-score Improvement vs. AF-Multimer | Antibody-Antigen Success Rate | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Deep learning (AF2 architecture) | Baseline | Baseline | Re-trained on protein assemblies [25] |

| AlphaFold3 | Deep learning (expanded biochemical space) | Not quantified | Not quantified | Models proteins, DNA, RNA, small molecules [25] |

| DeepSCFold | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | 11.6% higher TM-score (CASP15) | 24.7% higher than AF-Multimer [5] | pSS-score & pIA-score for MSA pairing [5] |

| MULTICOM series | Enhanced AF-Multimer pipeline | Moderate improvement over baseline | Moderate improvement | Customized MSAs, massive sampling [25] |

| Kiharalab | Enhanced AF-Multimer pipeline | Moderate improvement over baseline | Moderate improvement | Construct refinement, model selection [25] |

| kozakovvajda | Traditional protein-protein docking | Not directly comparable | >60% success rate (CASP16) [25] | Extensive sampling without AFM/AF3 [25] |

| Yang-Multimer | Enhanced AF-Multimer pipeline | Moderate improvement over baseline | Moderate improvement | Construct refinement, MSA optimization [25] |

Performance Across Target Categories

The assessment revealed significant variation in method performance across different target categories:

- Standard Oligomers: AlphaFold-based methods with enhanced pipelines (MULTICOM, Kiharalab) achieved the best performance for standard homo- and hetero-oligomers [25].

- Antibody-Antigen Complexes: The kozakovvajda group achieved exceptional performance (>60% success rate) using traditional protein-protein docking with extensive sampling, significantly outperforming AlphaFold-based approaches on these challenging targets [25].

- Host-Pathogen Interactions: Performance was moderate (95th percentile DockQ ~0.5-0.6), reflecting the challenge of capturing coevolutionary signals across species [25].

- Higher-Order Assemblies: Stoichiometry prediction remained challenging for high-order assemblies, with Phase 0 results significantly worse than Phase 1 where stoichiometry was provided [25].

Detailed Methodologies of Leading Approaches

AlphaFold-Based Pipelines

The majority of top-performing groups in CASP16 relied on AlphaFold-Multimer (AFM) or AlphaFold3 (AF3) as their core modeling engines, but significantly enhanced these base systems through several key strategies:

- MSA Optimization: Top groups employed customized MSA construction protocols beyond default settings, including iterative database searches and coevolutionary analysis [25] [26].

- Construct Refinement: Groups like Yang-Multimer refined modeling constructs using partial rather than full sequences, improving accuracy for specific interfaces [25].

- Massive Model Sampling: Successful pipelines generated thousands of models per target through variations in network dropout, recycling counts, and random seeds [25].

- Model Selection: Enhanced quality assessment methods were developed to identify the best models from large ensembles, though this remained a significant challenge [25].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for State-of-the-Art Structure Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Prediction Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | UniRef30/90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB | Provides evolutionary information via multiple sequence alignments [5] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | AlphaFold-Multimer, AlphaFold3, DeepSCFold, ESMFold | Core structure prediction engines [25] [5] |

| Model Sampling Systems | MassiveFold, AFsample | Generates structural diversity through parameter variation [25] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | DeepUMQA-X, built-in confidence metrics | Estimates model accuracy and selects best predictions [25] [5] |

| Specialized Protocols | DiffPALM, ESMPair, DeepMSA2 | Constructs paired MSAs for complex prediction [5] |

DeepSCFold Methodology

DeepSCFold introduced a novel approach based on sequence-derived structure complementarity, with a workflow comprising several innovative components:

DeepSCFold Workflow for Protein Complex Prediction

The DeepSCFold protocol employs two key sequence-based deep learning models:

- pSS-score: Predicts protein-protein structural similarity purely from sequence information, enhancing ranking and selection of monomeric MSAs [5].

- pIA-score: Estimates interaction probability between sequences from distinct subunit MSAs, enabling biologically relevant pairing [5].

This approach captures intrinsic and conserved protein-protein interaction patterns through sequence-derived structure-aware information, rather than relying solely on sequence-level co-evolutionary signals. This proves particularly advantageous for targets lacking strong coevolutionary signals, such as antibody-antigen complexes [5].

Traditional Docking Approach (kozakovvajda)

The kozakovvajda group demonstrated exceptional performance on antibody-antigen targets using a traditional protein-protein docking approach rather than AlphaFold-based methods. Their methodology included:

- Extensive Conformational Sampling: Generating a large diversity of potential binding poses [25]

- Sophisticited Scoring Functions: Effectively identifying native-like complexes from decoys [25]

- Specialized Refinement: Optimizing interface regions for specific complex types [25]

This success with non-AlphaFold methodology highlights that alternative approaches remain competitive for specific challenging categories, encouraging methodological diversity in the field [25].

Critical Challenges and Future Directions

Key Limitations Identified in CASP16

Despite overall progress, CASP16 highlighted several persistent challenges:

- Model Ranking Bottleneck: Even the best groups selected their optimal model as their first submission for only approximately 60% of targets, indicating that quality assessment remains a major limitation [25].

- Stoichiometry Prediction: Phase 0 revealed that predicting complex composition without prior knowledge remains challenging, particularly for higher-order assemblies and targets without homologous templates [25].

- Antibody-Antigen Complexes: These targets represented the most challenging category, with most groups achieving only approximately 25% success rates before the exceptional kozakovvajda performance [25].

- Nucleic Acid Modeling: RNA structure prediction accuracy lagged behind proteins, with reliable models dependent on the availability of good templates [26].

Emerging Frontiers

The CASP16 assessment points to several critical frontiers for future development:

- Beyond AlphaFold Paradigms: The success of alternative approaches like kozakovvajda's docking method suggests value in developing non-AlphaFold-based solutions for challenging targets [25].

- Integrated Multi-scale Modeling: Combining atomic-level structure prediction with lower-resolution data from cryo-EM, mass spectrometry, and cross-linking [27].

- Expanded Biochemical Space: Improving accuracy for nucleic acids, post-translational modifications, and small molecule interactions [25] [26].

- Dynamic Complexes: Moving from static structures to modeling conformational heterogeneity and binding dynamics.

Key Challenges and Future Research Directions

The CASP16 assessment demonstrates that protein structure prediction has reached unprecedented accuracy, particularly for monomeric domains, but significant challenges remain for complex quaternary structures. The field continues to be dominated by AlphaFold-based approaches, but with important innovations in MSA construction, model sampling, and specialized pipelines for particular target classes. The surprising success of traditional docking methods for antibody-antigen complexes highlights the value of methodological diversity. Future progress will depend on addressing key bottlenecks in model ranking, stoichiometry prediction, and expanding capabilities to more complex biomolecular systems including nucleic acids and small molecules. As methods continue to evolve, integration of experimental data with computational predictions appears poised to further extend the boundaries of what is predictable in structural biology.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications: From Server Workflows to Drug Discovery

Protein structure prediction is a cornerstone of computational structural biology, bridging the critical gap between the vast number of known protein sequences and the relatively small number of experimentally determined structures [28]. Among the various computational approaches, homology modeling stands out for its ability to generate high-resolution 3D models when evolutionarily related template structures are available [29]. However, as sequence identity between the target and template decreases into the "twilight zone" (below 30%), traditional comparative modeling methods struggle, necessitating more sophisticated algorithms that can leverage weaker structural signals [30]. I-TASSER (Iterative Threading ASSEmbly Refinement) represents a hierarchical approach that has consistently ranked as one of the top-performing automated methods in the community-wide Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments [28] [31] [32].

The fundamental paradigm underpinning I-TASSER is the sequence-to-structure-to-function pathway. Starting from an amino acid sequence, I-TASSER generates three-dimensional atomic models through multiple threading alignments and iterative structural assembly simulations. Biological function is then inferred by structurally matching these predicted models with other known proteins [28]. This integrated platform has served thousands of users worldwide, providing valuable insights for molecular and cell biologists who have protein sequences of interest but lack structural or functional information [28] [32]. The method's robustness stems from its ability to combine techniques from threading, ab initio modeling, and atomic-level refinement, creating a unified approach that transcends traditional boundaries between protein structure prediction categories [28].

The I-TASSER Hierarchical Workflow: A Stage-by-Stage Breakdown

Stage 1: Template Identification and Threading

The initial stage of the I-TASSER workflow focuses on identifying structurally similar templates from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The query sequence is first matched against a non-redundant sequence database using PSI-BLAST to identify evolutionary relatives and build a sequence profile [28]. This profile is also used to predict secondary structure using PSIPRED [28]. Assisted by both the sequence profile and predicted secondary structure, the query is then threaded through a representative PDB structure library using LOMETS (Local Meta-Threading Server), a meta-threading algorithm that combines several state-of-the-art threading programs [28] [30]. These may include FUGUE, HHSEARCH, MUSTER, PROSPECT, PPA, SP3, and SPARKS [28].

Each threading program ranks templates using a variety of sequence-based and structure-based scores. The top template hits from each program are selected for further consideration, with the quality of template alignments judged based on statistical significance (Z-score) [28]. This meta-threading approach is particularly valuable for recognizing correct folds even when no evolutionary relationship exists between the query and template protein [28] [30]. For targets with very low sequence similarity to known structures, this step provides the crucial initial fragments that guide subsequent assembly stages.

Stage 2: Structural Assembly through Fragment Reassembly

In the second stage, continuous fragments from the threading alignments are excised from the template structures and used to assemble structural conformations for well-aligned regions [28]. The unaligned regions—primarily loops and terminal tails—are built using ab initio modeling techniques [28] [30]. To balance efficiency with accuracy, I-TASSER employs a reduced protein representation where each residue is described by its Cα atom and side-chain center of mass [28].

The fragment assembly process is driven by a modified replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulation, which runs multiple parallel simulations at different temperatures and periodically exchanges temperatures between replicas [28]. This technique helps flatten energy barriers and speeds up transitions between different energy basins. The simulation is guided by a composite knowledge-based force field that incorporates: (1) general statistical terms derived from known protein structures (C-alpha/side-chain correlations, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobicity); (2) spatial restraints from threading templates; and (3) sequence-based contact predictions from SVMSEQ [28] [30]. The consideration of hydrophobic interactions and bias toward radius of gyration in the energy force field helps ensure physically realistic assemblies.

Stage 3: Cluster Analysis and Model Selection

Following the assembly simulations, the generated structure decoys are clustered using SPICKER, which identifies the largest density basins in the conformational space [32] [30]. The cluster centroids are obtained by averaging the coordinates of all structures within each cluster [32]. To address potential steric clashes in these centroid structures and enable further refinement, I-TASSER initiates a second round of fragment assembly simulation [32]. This iterative refinement step starts from the cluster centroids of the first simulation but incorporates additional spatial restraints extracted from both the centroids themselves and from PDB structures identified through structural alignment using TM-align [32].

The final models are selected by clustering the second-round decoys and identifying the lowest energy structure from each of the top clusters [32]. These models have Cα atoms and side-chain centers of mass specified, with full atomic details added later using Pulchra for backbone atoms and Scwrl for side-chain rotamers [32] [30]. This hierarchical clustering and selection process ensures that the final output includes not just a single prediction, but up to five structurally distinct models that represent the most stable and populated conformational states identified during the simulations.

Stage 4: Structure-Based Function Annotation

A distinctive capability of I-TASSER is its extension to functional annotation, based on the principle that protein function is determined by 3D structure [28]. The predicted models are structurally matched against known proteins in function databases such as BioLiP to infer functional insights [31]. This enables I-TASSER to predict ligand-binding sites, Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, and Gene Ontology (GO) terms [28] [31]. This structure-based function prediction approach can identify functional similarities even when the proteins share no significant sequence homology, overcoming a key limitation of sequence-based functional annotation methods [28].

Figure 1: The four-stage I-TASSER workflow for protein structure prediction and function annotation.

Performance Comparison with Other Homology Modeling Tools

Comparative Methodologies in Homology Modeling

To contextualize I-TASSER's performance, it is essential to understand the methodological landscape of homology modeling algorithms. Homology modeling programs generally fall into three categories: (1) rigid-body assembly methods, which assemble models from conserved core regions of templates; (2) segment matching approaches, which use databases of short structural segments; and (3) satisfaction of spatial restraints methods, which derive restraints from alignments and build models to satisfy these restraints [29]. MODELER exemplifies the spatial restraints approach, while SWISS-MODEL and ROSETTA represent rigid-body assembly and fragment-based methods, respectively [29] [8].

I-TASSER distinguishes itself through its composite approach that integrates multiple methodologies. Unlike programs that rely solely on one technique, I-TASSER combines threading with both template-based and ab initio fragment assembly [28]. This hybrid strategy enables it to handle a broader range of prediction challenges, from easy targets with clear templates to hard targets in the twilight zone. The iterative refinement process, where initial template structures are repeatedly reassembled and refined, allows I-TASSER to consistently generate models closer to native structures than the initial templates [28].

Quantitative Performance Metrics and Benchmarking Results

Multiple independent studies have benchmarked I-TASSER against other homology modeling tools. In the CASP experiments, I-TASSER (participating as "Zhang-Server") has been consistently ranked as the top automated server through multiple iterations of the competition [31] [32]. Quantitative analysis demonstrates that I-TASSER's inherent template fragment reassembly procedure drives initial template structures closer to native conformations. In CASP8, for example, final I-TASSER models had lower RMSD to native structures than the best threading templates for 139 out of 164 domains, with an average RMSD reduction of 1.2 Å (from 5.45 Å in templates to 4.24 Å in final models) [28].

Table 1: Comparative performance of homology modeling programs across different scenarios

| Program | Methodology | <30% Sequence Identity | >30% Sequence Identity | Function Prediction | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-TASSER | Composite threading/fragment assembly | Good performance on twilight-zone targets [30] | High accuracy [8] | Integrated function prediction [28] | CASP top performer; handles diverse target difficulties [28] [31] |

| MODELER | Satisfaction of spatial restraints | Struggles with low identity [11] | Excellent results [8] | Limited | High customization; reliable with good templates [8] |

| SWISS-MODEL | Rigid-body assembly | Limited success [11] | Fast and accurate [8] | No | Web-based ease of use [8] |

| ROSETTA | Fragment assembly + Monte Carlo | Good ab initio capability [8] | High accuracy [8] | Limited | Versatile; strong physics forcefield [8] |

| Phyre2 | Threading + fragment assembly | Moderate success [8] | Good results [8] | Limited | User-friendly web interface [8] |

For twilight-zone proteins with sequence identity below 30%, where traditional homology modeling methods face significant challenges, I-TASSER's composite approach provides distinct advantages. Benchmark tests demonstrate that I-TASSER can frequently generate models with correct topology even when sequence similarity is minimal [30]. The method's success in CASP experiments extends across various target difficulty categories, including free modeling targets that lack identifiable templates [32] [33].

Accuracy Assessment Through Confidence Scoring

A critical innovation in I-TASSER is its integrated confidence scoring system (C-score), which helps users assess prediction reliability without requiring external validation tools [32]. The C-score is calculated based on the significance of threading template alignments and the convergence of the assembly simulations:

Where M is the number of structures in the SPICKER cluster, Mtot is the total number of decoys, ⟨RMSD⟩ is the average RMSD to the cluster centroid, Z(i) is the highest Z-score from the i-th threading program, and Z0(i) is a program-specific Z-score cutoff [32].

This C-score shows a strong correlation with actual model quality, with a correlation coefficient of 0.91 to TM-score (a structural similarity measure) [32]. Models with C-score > -1.5 generally have correct topology with both false positive and false negative rates below 0.1 [32]. This built-in quality assessment provides researchers with practical guidance on how much trust to place in the predictions for their specific applications.

Table 2: I-TASSER performance metrics across different accuracy levels

| Model Resolution | RMSD Range | Typical Generation Scenario | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-resolution | 1-2 Å | Comparative modeling with close homologs | Computational ligand-binding studies, virtual compound screening [28] |

| Medium-resolution | 2-5 Å | Threading/CM with distant homologs | Identify spatial locations of functionally important residues [28] |

| Low-resolution | >5 Å (but correct topology) | Ab initio or weak threading hits | Protein domain boundary identification, topology recognition, family assignment [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Large-Scale Benchmarking Methodology

The performance claims for I-TASSER and comparative tools are derived from rigorous large-scale benchmarking studies. The standard protocol involves testing algorithms on diverse sets of protein targets with known structures but where these structures are withheld during the prediction process [29] [32]. The Community Wide Experiment on the Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) provides the most authoritative benchmarking framework, conducted biennially with blind predictions on previously unsolved structures [28] [32].

In these assessments, predictions are evaluated using multiple metrics including Global Distance Test (GDTTS), Template Modeling Score (TM-score), and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) [32]. GDTTS measures the percentage of Cα atoms under certain distance cutoffs after optimal superposition, while TM-score is a recently developed metric that is more sensitive to global fold similarity than local errors [32]. RMSD remains commonly used but can be disproportionately affected by small variable regions [32].

Protocol for User-Defined Alignment Testing

Some comparative studies employ user-defined alignments to isolate the model building component from template identification and alignment variations [11]. In this protocol, the same target-template alignment is provided to different modeling programs, and the resulting models are compared against the known native structure [11]. This approach directly tests each program's ability to convert alignment information into accurate 3D coordinates.

Studies using this methodology have revealed that while most programs produce similar results at high sequence identities (>30%), performance diverges significantly in the twilight zone [11] [29]. I-TASSER demonstrates particular advantages under these challenging conditions due to its iterative refinement approach, which can correct initial alignment errors and improve model quality beyond the starting template [28] [30].

Table 3: Key computational tools and resources in the I-TASSER ecosystem

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Workflow | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOMETS | Meta-threading server | Identifies structural templates from PDB | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| SPICKER | Clustering algorithm | Groups similar decoy structures; identifies cluster centroids | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| TM-align | Structural alignment tool | Measures structural similarity; extracts spatial restraints | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| BioLiP | Protein function database | Annotates predicted models with functional information | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| Pulchra | Backbone reconstruction | Adds backbone atoms (N, C, O) to Cα models | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| Scwrl | Side-chain placement | Predicts and optimizes side-chain rotamers | Integrated into I-TASSER |

| I-TASSER Server | Web platform | Complete structure prediction and function annotation | http://zhang.bioinformatics.ku.edu/I-TASSER [28] |

Figure 2: Key computational resources and their interactions in the I-TASSER pipeline.

I-TASSER represents a sophisticated integration of multiple protein structure prediction methodologies into a unified hierarchical framework. Its consistent top performance in CASP experiments demonstrates the effectiveness of combining threading, fragment assembly, and iterative refinement for generating high-quality protein models [28] [31] [32]. The platform's ability to drive initial template structures closer to native conformations, with average RMSD improvements of 1.2 Å as observed in CASP8, highlights the power of its reassembly algorithms [28].

For researchers, I-TASSER offers particular advantages for challenging prediction scenarios involving twilight-zone proteins with low sequence similarity to known structures [30]. The integrated function annotation extends its utility beyond structural biology into functional genomics and drug discovery applications [28] [31]. While the method demands substantial computational resources, its availability as a web server makes it accessible to non-specialists [34] [8].

The continuing development of I-TASSER, including recent deep-learning enhanced versions like D-I-TASSER and C-I-TASSER, promises further improvements in accuracy and scope [31]. As structural genomics initiatives continue to expand the template library, and computational methods evolve, integrated platforms like I-TASSER will play an increasingly vital role in bridging the sequence-structure-function gap for the ever-growing universe of protein sequences.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute the largest and most frequently used family of molecular drug targets, with approximately 33% of FDA-approved small-molecule drugs targeting members of this protein family [35] [36]. Their critical role in cellular signaling and therapeutic intervention makes them prime targets for structure-based drug discovery. However, the structural elucidation of membrane proteins, including GPCRs, has historically presented significant challenges due to their complex transmembrane topology and conformational flexibility [37]. The recent convergence of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) with traditional physics-based computational methods has revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to generate highly accurate structural models and perform sophisticated virtual screening campaigns [36].

This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of specialized computational tools developed for modeling membrane proteins and GPCRs, framing the analysis within a broader thesis on comparative performance of homology modeling programs. We examine cutting-edge platforms including GPCRVS, DeepSCFold, Memprot.GPCR-ModSim, and AiGPro, focusing on their methodological approaches, accuracy metrics, and applicability to drug discovery pipelines. By providing structured performance comparisons and detailed experimental protocols, this guide serves as a strategic resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage computational approaches for membrane protein-targeted therapeutic development.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Specialized Modeling Platforms

Table 1: Overview of Specialized Platforms for Membrane Protein and GPCR Modeling

| Platform | Primary Function | Methodological Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCRVS [35] | Virtual screening & activity prediction | Combines deep neural networks (TensorFlow) & gradient boosting machines (LightGBM) with molecular docking | Validated on ChEMBL & Google Patents data; handles peptide & small molecule compounds | Class A & B GPCR targets; peptide-binding GPCRs |

| DeepSCFold [5] | Protein complex structure prediction | Integrates sequence-derived structural complementarity with paired MSA construction | 11.6% & 10.3% TM-score improvement over AlphaFold-Multimer & AlphaFold3 on CASP15 targets | Antibody-antigen complexes; multimeric protein assemblies |

| Memprot.GPCR-ModSim [37] | Membrane protein system modeling & simulation | Combines AlphaFold2 modeling with MODELLER refinement & GROMACS MD simulation | Best automated web-based environment in GPCR Dock 2013 competition | GPCRs, transporters, ion channels |

| AiGPro [38] | GPCR agonist/antagonist profiling | Multi-task deep learning with bidirectional multi-head cross-attention mechanisms | Pearson correlation: 0.91 across 231 human GPCRs | Multi-target GPCR activity profiling |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Benchmark Studies

| Platform | Benchmark Dataset | Accuracy Metric | Comparison to Alternatives | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCRVS [35] | ChEMBL, Google Patents-retrieved data | Multiclass classification validated for activity range prediction | Overcomes limitations of individual ligand-based or target-based approaches | Limited to class A and B GPCRs included in system |

| DeepSCFold [5] | CASP15 protein complexes | TM-score improvement: +11.6% vs AlphaFold-Multimer, +10.3% vs AlphaFold3 | Superior for targets lacking clear co-evolutionary signals | Requires substantial computational resources |

| Memprot.GPCR-ModSim [37] | GPCR Dock 2013 targets | Successfully recreates target structures in competition | Generalizes to any membrane protein system beyond class A GPCRs | Automated refinement may not capture all conformational states |

| AiGPro [38] | 231 human GPCR targets | Pearson correlation: 0.91 for bioactivity prediction | Outperforms previous RF, GCN, and ensemble models | Limited to bioactivity prediction without 3D structural output |

| AlphaFold2 [36] | 29 GPCRs with post-2021 structures | TM domain Cα RMSD: ~1 Å | More accurate than RoseTTAFold and conventional homology modeling | Tendency to produce "average" conformational states |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

AI-Driven Virtual Screening with GPCRVS

The GPCRVS platform employs a sophisticated multi-algorithm approach for virtual screening against GPCR targets. The methodology integrates two diverse machine learning algorithms: multilayer neural networks implemented in TensorFlow and gradient boosting decision trees using LightGBM [35]. The system was trained on carefully curated datasets retrieved from ChEMBL, with an 80/20% ratio between training and validation sets using random splitting.

A particularly innovative aspect of GPCRVS is its handling of peptide compounds, which are challenging for conventional virtual screening. The platform implements a six-residue peptide truncation approach, converting nearly 30-amino acid peptides to 6-residue-long N-terminal fragments that carry the activation 'message' for receptor binding [35]. These truncated peptides are then converted to SMILES notation and treated as small molecules in subsequent docking procedures. For molecular docking, GPCRVS implements the flexible ligand docking mode of AutoDock Vina, with receptor structures based on PDB entries or modeled using the Modeller/Rosetta CCD loop modeling approach for GPCR structure prediction [35].

Experimental validation of GPCRVS involved two distinct datasets: one with highly active compounds retrieved from ChEMBL and manually checked for target selectivity, and another containing 140 patent compounds obtained from Google Patents for various GPCR targets including CCR1, CCR2, CRF1R, GCGR, and GLP1R [35]. The platform demonstrated robust performance in activity class assignment and binding affinity prediction when compared against known active ligands for each included GPCR.

Sequence-Based Complex Structure Prediction with DeepSCFold

DeepSCFold introduces a novel protocol for protein complex structure prediction that relies on sequence-derived structural complementarity rather than solely on co-evolutionary signals. The method begins by generating monomeric multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) from diverse sequence databases including UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, and the ColabFold DB [5].

The core innovation of DeepSCFold lies in its two deep learning models that predict: (1) protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) purely from sequence information, and (2) interaction probability (pIA-score) based solely on sequence-level features [5]. These predicted scores enable the systematic construction of paired MSAs by integrating multi-source biological information, including species annotations, UniProt accession numbers, and experimentally determined protein complexes from the PDB.

The benchmark evaluation protocol for DeepSCFold utilized multimer targets from CASP15, with complex models generated using protein sequence databases available up to May 2022 to ensure temporally unbiased assessment. Predictions were compared against state-of-the-art methods including AlphaFold3, Yang-Multimer, MULTICOM, and NBIS-AF2-multimer [5]. When applied to antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, DeepSCFold significantly enhanced the prediction success rate for antibody-antigen binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, demonstrating particular strength for challenging cases that lack clear inter-chain co-evolution signals [5].