How to Calculate RMSD for Protein Structure Comparison: A Guide for Structural Biologists and Drug Developers

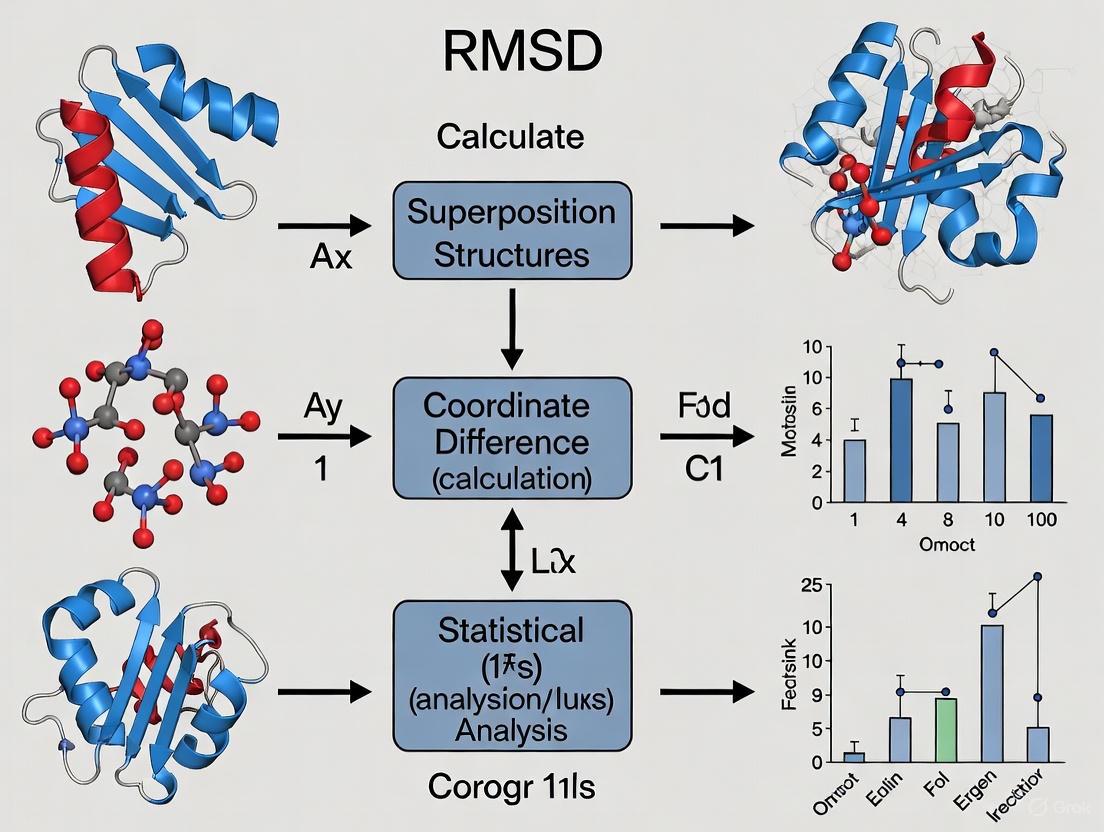

This article provides a comprehensive guide to calculating and interpreting the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for protein structure comparison, a fundamental task in structural biology, drug discovery, and protein...

How to Calculate RMSD for Protein Structure Comparison: A Guide for Structural Biologists and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to calculating and interpreting the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for protein structure comparison, a fundamental task in structural biology, drug discovery, and protein modeling. It covers the foundational principles and mathematical formula of RMSD, detailed methodologies for practical calculation using common tools and algorithms, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls and optimizing alignments, and a comparative analysis of RMSD against other similarity metrics like TM-score and GDT. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enable accurate quantification of structural similarities and differences.

What is RMSD? Understanding the Core Concepts of Protein Structural Similarity

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in structural biology and computational chemistry for quantifying the average distance between the atoms of two superimposed molecular structures. It provides a single, quantitative measure of structural similarity, serving as an essential tool for comparing three-dimensional protein conformations. The RMSD value, typically expressed in Angstroms (Å), is defined as the square root of the average squared distance between corresponding atoms in two optimally aligned structures. A value of 0 indicates identical structures, while increasing values reflect greater structural divergence [1] [2].

The significance of RMSD extends across multiple scientific domains, from assessing protein flexibility and conformational changes to evaluating the performance of computational modeling methods. In drug discovery, RMSD calculations help researchers understand ligand-binding interactions, analyze molecular dynamics trajectories, and validate structural predictions against experimental data. Its mathematical simplicity and intuitive interpretation have established RMSD as the gold standard for structural comparison, despite the development of complementary metrics [3] [4].

Mathematical Foundation and Calculation

The mathematical formulation of RMSD centers on the calculation of the root mean square of the minimal distances between corresponding atoms in two aligned structures. For two sets of atomic coordinates representing different conformations of the same molecule, the RMSD is calculated after optimal superposition to minimize the overall deviation [1].

Core Mathematical Formula

The standard RMSD formula for comparing two superimposed structures with n equivalent atoms is:

RMSD = √[ (1/n) × Σ(d_i)² ]

Where:

- n = number of atom pairs compared

- d_i = distance between the i-th pair of corresponding atoms

- Σ = summation over all n atom pairs [1] [3]

This calculation requires prior optimal superposition of the two structures, typically achieved through rotational and translational adjustments that minimize the RMSD value itself, a process known as the Kabsch algorithm [5].

Key Properties and Characteristics

RMSD possesses several mathematical properties that influence its application and interpretation:

- Non-negativity: RMSD values are always zero or positive, with zero representing perfect congruence [1]

- Sensitivity to outliers: Due to the squaring of distances, larger deviations contribute disproportionately to the final value [1] [3]

- Scale dependence: RMSD values are directly expressed in distance units (typically Å), making them dependent on the scale of the structures being compared [1]

- Dimensionality dependence: For proteins of different sizes, RMSD values are affected by the number of atoms included in the calculation [5]

Applications in Structural Biology and Drug Discovery

RMSD analysis provides critical insights across numerous research domains, serving as a versatile tool for structural comparison and validation.

Protein Structure Analysis

In structural bioinformatics, RMSD quantifies conformational differences between protein structures. This includes measuring structural divergence in homologous proteins, assessing conformational changes upon ligand binding, and evaluating protein flexibility through molecular dynamics simulations. The root mean square deviation of atomic positions represents the standard measure of the average distance between atoms of superimposed proteins [1] [5].

Drug Discovery and Development

RMSD plays several crucial roles in structure-based drug design:

- Docking validation: Comparing predicted ligand binding poses to experimental crystallographic data [1] [2]

- Molecular dynamics: Tracking conformational stability and changes during simulations of drug-receptor interactions [4]

- Virtual screening: Assessing structural similarity between candidate compounds and known active molecules [2]

Modeling Assessment

Community-wide initiatives such as CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) and GPCR Dock employ RMSD as a primary metric for evaluating the accuracy of computational models against experimental reference structures [3].

Table 1: RMSD Interpretation Guidelines in Protein Studies

| RMSD Range (Å) | Structural Relationship | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 1.0 | Very high similarity | Alternative conformations of the same protein; different experimental conditions |

| 1.0 - 2.0 | High similarity | Close homologs; different crystallization conditions |

| 2.0 - 3.5 | Moderate similarity | Distant homologs; conformational changes |

| > 3.5 | Low similarity | Different folds; major conformational transitions |

Normalization and Advanced RMSD Metrics

A significant limitation of standard RMSD is its dependence on protein size, making comparisons across different-sized structures problematic. A normalized RMSD metric was developed to address this issue, enabling more meaningful comparisons between proteins of varying lengths [5].

Normalization Approaches

Several normalization strategies have been developed to enhance the comparability of RMSD values:

- Length-dependent normalization: Adjusts RMSD values to equivalent statistical significance for different protein lengths, such as the RMSD100 approach which normalizes to the value expected for a 100-residue protein [5] [6]

- Range normalization: Divides RMSD by the range of the observed data (NRMSD) [1]

- Mean normalization: Expressed as a percentage of the mean observed value (CV(RMSD)) [1]

- Interquartile range normalization: Divides RMSD by the interquartile range to reduce sensitivity to extreme values [1]

Table 2: Normalized RMSD Variants and Applications

| Metric | Formula | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| NRMSD | RMSD / (yₘₐₓ - yₘᵢₙ) | Comparison across different scales |

| CV(RMSD) | RMSD / ȳ | Percentage-based comparison |

| RMSD100 | Normalized to 100 residues | Comparing proteins of different lengths |

| RMSDIQR | RMSD / IQR | Reduced sensitivity to outliers |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for RMSD Calculation Between Two Protein Structures

Objective: Calculate the backbone RMSD between two conformations of the same protein to quantify structural differences.

Materials and Software Requirements:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PyMOL | Visualization software | Structure visualization and analysis |

| MAMMOTH | Structural alignment algorithm | Optimal structure superposition |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics package | Trajectory analysis and RMSD calculation |

| RCSB PDB | Structural database | Source of experimental reference structures |

| ChimeraX | Molecular visualization | Interactive structure comparison |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Structure Preparation

- Obtain atomic coordinates for both structures in PDB format

- Remove heteroatoms (water, ions, ligands) unless specifically relevant to analysis

- Ensure identical atom selection and numbering between structures

Atom Selection

- Select equivalent atoms for comparison (typically Cα atoms for backbone RMSD)

- Verify sequence correspondence between structures

- Note the number of atom pairs (n) included in the calculation

Optimal Superposition

- Apply the Kabsch algorithm for rotational and translational alignment

- Minimize the sum of squared distances between corresponding atoms

- Iteratively refine alignment if using outlier-resistant methods

Distance Calculation and RMSD Computation

- Calculate Euclidean distances between all corresponding atom pairs

- Square each distance value

- Compute the mean of squared distances

- Take the square root to obtain the final RMSD value

Validation and Interpretation

- Visually inspect the quality of structural alignment

- Compare RMSD value to appropriate benchmarks for the system

- Consider complementary metrics (GDT, MaxSub) for full assessment

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High RMSD values may indicate poor alignment rather than true structural differences

- Mismatched atom selections will produce artificially elevated RMSD

- Flexible regions disproportionately influence global RMSD; consider core-only analysis

Protocol for Time-Resolved RMSD Analysis in Molecular Dynamics

Objective: Monitor conformational stability and changes throughout MD simulations.

Procedure:

- Trajectory Preparation: Align all simulation frames to a reference structure (usually the initial frame or average structure) to remove global translation and rotation

- Reference Selection: Choose an appropriate reference structure for comparison (typically the starting structure or a representative conformation)

- Frame-by-Frame Calculation: Compute RMSD between each trajectory frame and the reference structure

- Time Series Analysis: Plot RMSD as a function of simulation time to identify equilibration, stability, and conformational transitions

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate average RMSD, fluctuations, and distribution characteristics for stable simulation segments

Limitations and Complementary Metrics

While RMSD remains the most widely used structural comparison metric, several limitations necessitate complementary approaches:

Key Limitations

- Sensitivity to outliers: A small number of highly deviating regions can dominate the RMSD value, obscuring overall similarity [3]

- Size dependence: Larger proteins tend to have higher RMSD values, complicating cross-protein comparisons [5]

- Global measure: RMSD may poorly represent local similarities, especially in flexible proteins with domain movements [3]

- Alignment dependence: Results are highly sensitive to the quality and method of structural alignment [3] [6]

Alternative and Complementary Metrics

- Global Distance Test (GDT): Measures the largest set of residues that superimpose under defined distance cutoffs, more focused on common core than outliers [6]

- MaxSub: Identifies the largest well-overlapped subset of the protein [6]

- Template Modeling Score (TM-score): Size-independent metric that emphasizes spatial proximity of closer residues [7]

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): Residue-based evaluation without requiring superposition [3]

Root Mean Square Deviation remains an indispensable tool for quantifying structural relationships in macromolecular research. Its mathematical clarity, computational efficiency, and intuitive interpretation have secured its position as the gold standard for structural comparison across diverse applications from basic structural biology to drug discovery. While aware of its limitations, researchers continue to rely on RMSD as a primary metric, enhanced by normalization approaches and complementary measures when appropriate. As structural biology advances with cryo-EM and AI-based structure prediction, RMSD maintains its fundamental role in validating and comparing three-dimensional molecular architectures.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a foundational metric in computational structural biology, providing a quantitative measure of the average distance between atoms in superimposed protein structures. For researchers and drug development professionals, RMSD serves as a crucial tool for assessing structural similarity, evaluating protein structure predictions, analyzing molecular dynamics simulations, and understanding ligand-induced conformational changes. The RMSD value, expressed in Angstroms (Å), offers a single numerical representation of structural differences, where a value of 0 indicates perfect superposition and increasing values reflect greater structural divergence [1] [3]. In the context of protein structure comparison research, accurately calculating and interpreting RMSD is essential for validating computational models, assessing docking predictions, and understanding structure-function relationships that underpin drug discovery efforts.

The importance of RMSD extends across multiple domains within structural biology. In protein structure prediction assessments like CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction), RMSD provides an objective standard for evaluating model accuracy against experimental reference structures [3]. In structure-based drug design, RMSD calculations help quantify how closely a docked ligand conformation matches experimental observations, guiding lead optimization efforts [1] [8]. Furthermore, in molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD analysis tracks conformational changes over time, revealing insights into protein flexibility, folding pathways, and functional mechanisms [2]. Despite the development of alternative metrics such as TM-score and GDT, RMSD remains widely used due to its mathematical simplicity, intuitive interpretation, and historical establishment within the structural biology community [9] [10].

Mathematical Foundation of RMSD

Core RMSD Formula

The Root Mean Square Deviation represents the square root of the arithmetic mean of the squares of the deviations between corresponding atomic positions. For two superimposed sets of atomic coordinates, the RMSD is mathematically defined as:

RMSD = √[ (1/n) × Σᵢ(Δxᵢ² + Δyᵢ² + Δzᵢ²) ]

Where:

- n represents the total number of atom pairs included in the calculation

- Σᵢ denotes the summation over all n atom pairs

- Δxᵢ, Δyᵢ, Δzᵢ represent the differences in x, y, and z coordinates between the i-th pair of corresponding atoms after optimal superposition [1] [11]

This formula can be equivalently expressed in terms of the Euclidean distances between corresponding atom pairs:

RMSD = √[ (1/n) × Σᵢ(dᵢ²) ]

Where dᵢ represents the Euclidean distance between the i-th pair of corresponding atoms after superposition [3]. This formulation highlights that RMSD essentially measures the root mean square of the straight-line distances between equivalent atoms in the two structures being compared.

Calculation Methodology

The computation of RMSD between two protein structures involves a systematic multi-step process that ensures accurate and meaningful comparison:

Atom Selection and Correspondence: The first critical step involves identifying which atoms to include in the calculation and establishing one-to-one correspondence between equivalent atoms in the two structures. For protein backbone comparisons, this typically involves Cα atoms, while all-atom RMSD includes all non-hydrogen atoms [3] [10].

Structural Superposition: The two structures are optimally aligned through translation and rotation to minimize the RMSD value itself. This is typically achieved using algorithms like the Kabsch method, which finds the optimal rotation matrix that minimizes the sum of squared distances between corresponding atoms [2].

Distance Calculation: After superposition, the Euclidean distances between each pair of corresponding atoms are calculated using the standard distance formula in three-dimensional space.

Averaging and Root Extraction: The squared distances are summed, averaged by dividing by the number of atom pairs, and the square root of this average provides the final RMSD value [1] [11].

The following workflow illustrates the complete RMSD calculation process:

Research Applications in Protein Science

Protein Structure Comparison and Model Validation

RMSD serves as a fundamental metric for comparing experimental protein structures and validating computational models. In the protein structure prediction assessment (CASP), RMSD provides an objective measure to evaluate the accuracy of predicted models against experimentally determined reference structures [3]. Similarly, when comparing different experimental structures of the same protein determined under varying conditions (e.g., with different ligands, pH, or crystal forms), RMSD quantifies conformational changes and flexibility. The distribution of backbone RMSD values for experimentally determined structure pairs of identical proteins typically ranges from 0 to 1.2 Å, reflecting inherent protein flexibility and experimental resolution limits [3]. For homology modeling, RMSD values below 2.0 Å for Cα atoms generally indicate high-quality models, particularly when closely related structural templates are available [9].

Molecular Dynamics and Conformational Analysis

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, RMSD analysis tracks structural evolution and stability over time. By calculating RMSD between simulation frames and a reference structure (typically the initial minimized structure), researchers monitor conformational sampling, convergence, and structural deviations. This application reveals protein folding pathways, functional motions, and ligand-induced conformational changes [2]. Time-resolved RMSD analysis can identify stable conformational states, transition points, and equilibrium behavior, providing insights into the relationship between protein dynamics and biological function. The sensitivity of RMSD to larger structural changes makes it particularly valuable for detecting major conformational transitions in simulated systems.

Drug Discovery and Docking Assessment

In structure-based drug design, RMSD calculations play a crucial role in evaluating docking predictions and virtual screening results. For protein-ligand docking, heavy-atom RMSD between predicted and experimental ligand conformations assesses docking accuracy and scoring function performance [1] [8]. Lower ligand RMSD values indicate more reliable pose predictions, with values below 2.0 Å generally considered successful in virtual screening applications. Additionally, RMSD analysis of protein binding sites helps quantify backbone and sidechain rearrangements upon ligand binding, revealing induced-fit mechanisms and allosteric effects that influence drug binding and specificity [8].

Table 1: RMSD Interpretation Guidelines in Protein Structure Comparison

| RMSD Range | Structural Interpretation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 Å | Very high similarity; minimal structural differences | Same protein under different conditions; high-quality model validation |

| 1.0 - 2.0 Å | High similarity; minor conformational variations | Close homologs; accurate homology models; ligand-induced changes |

| 2.0 - 3.0 Å | Moderate similarity; significant local differences | Distant homologs; medium-quality models; domain movements |

| > 3.0 Å | Low similarity; major structural differences | Different folds; poor models; substantial conformational changes |

Experimental Protocol for RMSD Calculation

Structure Preparation and Preprocessing

Proper structure preparation is essential for meaningful RMSD calculations. Begin by selecting appropriate protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or computational models. Remove heteroatoms including water molecules, ions, and small molecules unless specifically relevant to the analysis. Ensure both structures contain identical atom sets with consistent atom naming and numbering conventions. For protein backbone RMSD, select Cα atoms exclusively; for all-atom RMSD, include all non-hydrogen atoms. Identify and handle missing residues or atoms appropriately, either by excluding incomplete regions or using modeling tools to reconstruct missing coordinates. Verify that both structures have the same number of atoms selected for comparison to ensure valid one-to-one correspondence [2] [10].

Structural Alignment Procedures

Structural alignment optimizes the superposition of two structures to minimize the RMSD value. Implement the Kabsch algorithm for optimal rigid-body alignment, which involves:

- Translation: Center both structures at the origin by subtracting their centroids from all atomic coordinates.

- Covariance Matrix Calculation: Compute the covariance matrix H between the two centered coordinate sets.

- Rotation Matrix Determination: Perform singular value decomposition (SVD) of H to obtain the optimal rotation matrix.

- Coordinate Transformation: Apply the rotation matrix to the second structure to align it with the first structure.

For complex structural comparisons involving domain movements or flexible regions, consider iterative superposition methods that assign lower weights to highly deviating regions. Alternatively, use flexible alignment algorithms like FATCAT that introduce twists between rigid domains to better align structures with internal flexibility [10]. Visually inspect the aligned structures to verify the biological reasonableness of the superposition before proceeding with RMSD calculation.

RMSD Computation and Validation

After optimal superposition, calculate the RMSD using the standard formula. Compute both global RMSD (all selected atoms) and regional RMSD values for specific structural elements (e.g., binding sites, secondary structure elements) to gain comprehensive insights. Validate RMSD calculations by comparing results from multiple software packages (PyMOL, ChimeraX, VMD) to ensure consistency. Perform sensitivity analysis by testing how RMSD values change with different atom selections or alignment methods. Cross-reference RMSD values with other similarity metrics like TM-score or GDT for a more comprehensive assessment of structural similarity [9] [10].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RMSD Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in RMSD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Software | PyMOL, ChimeraX, VMD | Visualization, structural alignment, and RMSD calculation |

| Web-Based Platforms | RCSB PDB Pairwise Alignment, CSAlign | Accessible RMSD calculation without local software installation |

| Programming Libraries | BioPython, MDAnalysis | Automated, high-throughput RMSD analysis in scripts |

| Specialized Algorithms | Kabsch, FATCAT, CE | Optimal structural superposition for RMSD minimization |

| Structure Datasets | PDB, AlphaFold Database | Source of experimental and predicted structures for comparison |

Interpretation and Limitations

Contextual Interpretation of RMSD Values

Interpreting RMSD values requires careful consideration of biological context, comparison scale, and research objectives. For global protein structure comparisons, RMSD values below 2.0 Å typically indicate highly similar structures, while values exceeding 3.0 Å suggest significant structural differences [9]. However, these thresholds vary depending on protein size, comparison scope, and scientific question. Regional RMSD analysis often provides more biologically relevant insights than global RMSD alone, particularly when comparing specific functional domains or binding sites. Additionally, consider inherent protein flexibility—regions with high conformational variability (e.g., surface loops) naturally exhibit higher RMSD values without necessarily indicating poor model quality or biological insignificance [3].

The relationship between RMSD and structural similarity is not linear, and RMSD values should be interpreted relative to protein size. For large proteins or complexes, slightly higher RMSD values may still represent biologically relevant similarities, while for small proteins or ligands, even sub-Angstrom differences might be significant. Always correlate RMSD findings with visual inspection of aligned structures and complementary metrics like TM-score, which normalizes for protein size and provides a more intuitive similarity score between 0 and 1 [9] [10].

Limitations and Complementary Metrics

Despite its widespread use, RMSD has several limitations that researchers must acknowledge. RMSD is highly sensitive to outliers—a small number of highly deviating regions can disproportionately increase the global RMSD, masking overall structural similarity [1] [3]. This outlier sensitivity makes RMSD less suitable for comparing structures with localized flexibility or conformational changes. Additionally, RMSD is scale-dependent, making comparisons across different proteins or datasets problematic. RMSD also decreases with increasing number of atoms included in calculations, potentially leading to misleading comparisons between analyses with different atom selections [12].

To address these limitations, complement RMSD with alternative metrics:

- TM-score: Provides length-independent structural similarity assessment, with values above 0.5 indicating same fold and below 0.17 indicating random similarity [9] [10].

- GDT (Global Distance Test): Measures the percentage of residues within specified distance cutoffs, offering a more robust assessment of global fold similarity [9].

- LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test): Evaluates local structural quality by comparing distance maps, remaining reliable even with domain movements [9].

The following decision tree guides the selection of appropriate structural similarity metrics:

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Normalization Strategies for Enhanced Comparability

Normalizing RMSD values facilitates more meaningful comparisons across different protein systems and scales. Common normalization approaches include dividing RMSD by the range of the measured data (maximum minus minimum values) or by the mean of the observed values [1]. The Normalized RMSD (NRMSD) is calculated as:

NRMSD = RMSD / (yₘₐₓ - yₘᵢₙ)

Alternatively, researchers may calculate the Coefficient of Variation of RMSD:

CV(RMSD) = RMSD / ȳ

Where ȳ represents the mean of the observed values [1]. For structural comparisons, normalization by protein length or diameter provides more comparable metrics across different sized proteins. Another robust approach divides RMSD by the interquartile range (IQR) to reduce sensitivity to extreme values:

RMSD/IQR = RMSD / (Q₃ - Q₁)

Where Q₁ and Q₃ represent the first and third quartiles of distance distributions [1]. These normalization strategies enhance the comparability of RMSD values across different studies, protein systems, and experimental conditions.

Emerging Methodologies and Future Developments

The field of structural comparison continues to evolve with emerging methodologies enhancing RMSD analysis and application. Machine learning approaches increasingly incorporate RMSD-derived features for protein structure prediction and quality assessment [2]. Artificial intelligence-powered alignment algorithms can identify optimal superpositions more efficiently than traditional methods, while ensemble-based RMSD calculations account for structural dynamics by comparing multiple conformational states simultaneously [2].

Advances in structural biology techniques, particularly cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), present new opportunities and challenges for RMSD applications. As cryo-EM structures often exhibit regional resolution variations, development of resolution-weighted RMSD calculations represents an active research direction [2]. Similarly, integrative structural biology approaches that combine data from multiple experimental sources (X-ray crystallography, NMR, cryo-EM, cross-linking mass spectrometry) require specialized RMSD approaches that accommodate different uncertainty characteristics across structural regions [2]. Future RMSD methodologies will likely incorporate Bayesian frameworks to explicitly account for positional uncertainties, providing more statistically rigorous structural comparisons that reflect the inherent limitations of both experimental and computational structural models.

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in structural biology that quantifies the average distance between atoms of two superimposed three-dimensional structures. For proteins, this typically involves calculating the displacement between equivalent Cα atoms after optimal rigid-body superposition. The mathematical formulation for RMSD is expressed as RMSD = √[Σ(di)²/N], where di represents the distance between the i-th pair of equivalent atoms and N is the total number of atom pairs compared [3] [13]. Despite its apparent simplicity, the problem of quantifying differences between protein structures is non-trivial and continues to evolve with new methodologies [3]. RMSD provides a single summary value measured in Ångströms (Å), where 0 indicates identical structures and increasing values reflect greater structural dissimilarity [13] [9].

The significance of RMSD extends beyond mere geometric comparison. As articulated by, two protein conformations can be considered intrinsically similar only if their RMSD is smaller than that obtained when one structure is mirror-inverted [14]. This conceptual framework establishes RMSD as a meaningful indicator of overall chain folding patterns and structural conservation. While RMSD remains the most popular measure for structural comparison, it is dominated by the largest errors present in compared structures, which has led to the development of complementary metrics and methods to address its limitations [3].

Key Applications of RMSD

Assessment of Computational Models in Structure Prediction

RMSD serves as a primary validation metric in community-wide blind assessments of protein structure prediction methods such as CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) and GPCR Dock [3]. In these evaluations, computational models are compared to experimentally determined reference structures using RMSD among other measures. The distribution of backbone RMSD values for accurate models typically ranges around 2.3 Å for homology modeling cases with close sequence relatives (~40% identity), with values increasing for more distantly related templates [3]. The Global Distance Test (GDT), a derivative metric, calculates the percentage of residues within certain distance cutoffs (typically from 0.5 Å to 10.0 Å) after superposition, providing a more robust assessment of model quality than RMSD alone, particularly for proteins with conformational flexibility [9].

Table 1: RMSD Interpretation Guidelines for Model Assessment

| RMSD Value | Interpretation | Model Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| <2 Å | High atomic-level accuracy | Very similar or identical structures; successful prediction |

| 2-4 Å | Moderate residue-level accuracy | Structurally similar but not identical; quality depends on required resolution |

| >4 Å | Low domain-level accuracy | Structurally different; generally unacceptable for most applications |

Analysis of Protein Flexibility and Conformational Changes

RMSD analysis reveals fundamental insights into protein dynamics and flexibility by quantifying conformational differences between structures of identical proteins determined under varying conditions. Experimental evidence from the Protein Data Bank shows that the majority of identical protein pairs exhibit RMSD values ranging from 0 to 1.2 Å due to inherent protein flexibility and experimental resolution limits [3]. Significantly higher RMSD values indicate substantial conformational rearrangements, such as those occurring between active and inactive states of receptors. For example, the active and inactive conformations of estrogen receptor α exhibit large global backbone RMSD values despite differing primarily in the position of a single helix, demonstrating how RMSD can capture functionally relevant structural transitions [3].

Evaluation of Protein-Ligand Docking Results

In molecular docking assessments, RMSD provides a crucial measure of docking accuracy by quantifying the spatial proximity between predicted and experimentally determined ligand binding poses. The CAPRI (Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions) community experiment employs RMSD among other metrics to evaluate docking predictions [3]. For protein-drug complexes in molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD analysis tracks the stability of protein structures across different ligand interactions, revealing how identical proteins can exhibit varying RMSD profiles when complexed with different drugs due to simulation randomness and specific interaction patterns [15]. This application is particularly valuable in drug discovery for comparing how a common protein target responds to different therapeutic compounds.

Evolutionary Studies and Structural Genomics

While sequence similarity traditionally guides evolutionary studies, RMSD-based structural comparisons often reveal conserved folds and functional relationships even when sequence identity falls below 25% [9]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying distant evolutionary relationships that are undetectable through sequence analysis alone. Structural comparison tools like FoldSeek and SARST2 leverage RMSD-like metrics to identify proteins with similar folds despite minimal sequence similarity, enabling more comprehensive evolutionary analyses [16] [9]. The TM-score, which normalizes RMSD by protein length, provides a more reliable measure for detecting common folds across evolutionarily related proteins, with scores above 0.5 indicating generally the same fold [9].

Experimental Protocols for RMSD Calculation

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithm Selection

The standard protocol for RMSD calculation involves three critical steps: structural alignment, optimal superposition, and distance calculation. The Kabsch algorithm provides the mathematical foundation for determining the optimal rotation matrix that minimizes the RMSD between two sets of coordinate points [13]. This algorithm operates through a sequence of steps: (1) translation of both structures to place their geometric centers at the origin (x=0, y=0, z=0), (2) computation of the covariance matrix between the two coordinate sets, and (3) derivation of the optimal rotation matrix through singular value decomposition [13]. The quaternion algorithm represents an alternative approach for solving the same superposition problem [13].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function in RMSD Analysis |

|---|---|

| PDB Structure Files | Source of atomic coordinates for reference and model structures (e.g., 1Y3N, 1Y3Q) |

| Cα Atom Selection | Standard reference points for backbone structure comparison |

| Kabsch Algorithm | Computational method for optimal rigid-body superposition |

| Molecular Visualization Software | Visual assessment of structural alignment quality |

| Molecular Dynamics Trajectories | Time-dependent structural data for RMSD fluctuation analysis |

Practical Implementation Using Python and NumPy

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for calculating RMSD between two protein structures:

Structure Preparation: Obtain PDB files for both reference and model structures. Select equivalent atoms for comparison (typically Cα atoms for backbone analysis).

Coordinate Extraction: Parse PDB files to extract Cartesian coordinates for selected atoms using a PDB reader module.

Centering Structures: Translate both structures to place their centroids at the coordinate origin:

Calculate Covariance Matrix:

Singular Value Decomposition:

Ensure Proper Rotation (remove mirroring):

Apply Rotation and Calculate RMSD:

This implementation produces both the RMSD value and the aligned coordinates for visualization [13].

Workflow for Comparative Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete RMSD calculation workflow:

Complementary Metrics and Methodological Considerations

Limitations of RMSD and Alternative Approaches

Despite its widespread use, RMSD has significant limitations that researchers must consider. RMSD is highly sensitive to outliers, meaning that a small number of deviating regions can disproportionately influence the overall value [3]. This is particularly problematic when comparing structures with flexible termini, loops, or relative domain movements. Additionally, RMSD values are length-dependent, making comparisons across different-sized proteins challenging. To address these limitations, several complementary metrics have been developed:

- TM-score: A length-normalized metric that provides a more balanced assessment of global fold similarity, with scores ranging from 0 to 1 (where >0.5 indicates the same fold) [9].

- GDT (Global Distance Test): Calculates the percentage of residues within specified distance cutoffs, offering a more robust measure for model quality assessment [9].

- LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test): Evaluates local structural quality by comparing distance distributions in a superposition-independent manner, making it particularly valuable for assessing structures with domain movements [9].

Integration with Contact-Based Measures

Contact-based measures offer a superposition-independent alternative to RMSD by quantifying the similarity of residue-residue contact patterns between structures [3]. These methods are often more robust against structural outliers and better capture the fundamental nature of protein folding determinants. Modern structural alignment tools like SARST2 integrate multiple approaches, combining primary sequence, secondary structure elements, and tertiary contact information to achieve both accuracy and efficiency in massive database searches [16]. The integration of RMSD with contact-based measures provides a more comprehensive framework for structural comparison in evolutionary studies and model assessment.

RMSD remains an indispensable tool in structural biology, providing a straightforward, interpretable measure of structural similarity with critical applications across protein modeling, docking, dynamics analysis, and evolutionary studies. While its limitations necessitate complementary approaches like TM-score and contact-based measures, RMSD continues to offer fundamental insights into protein structure and function. As structural databases expand with AI-predicted models, efficient RMSD calculation and interpretation will remain essential skills for researchers navigating the era of structural big data. The protocols and applications outlined herein provide a foundation for the rigorous application of RMSD in scientific research and drug development.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in structural biology for quantifying the similarity between two protein structures. The utility and interpretation of an RMSD value are profoundly influenced by the selection of atoms used in the calculation. This application note provides a detailed protocol for researchers, focusing on the strategic selection of atoms—from the common Cα and backbone atoms to more specialized subsets—to ensure that RMSD measurements are both accurate and biologically meaningful. Proper atomic selection is critical for applications ranging from assessing protein folding and conformational changes to validating computational models against experimental structures.

Core Concepts of RMSD

The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) provides a quantitative measure of the average distance between the atoms of two superimposed protein structures. The standard formula for calculating RMSD between two sets of coordinates, ( v ) and ( w ), for ( n ) equivalent atoms is:

[ \mathrm{RMSD} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}\|vi - wi\|^2} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}((v{ix}-w{ix})^2+(v{iy}-w{iy})^2+(v{iz}-w{iz})^2)} ]

The result is expressed in length units, typically Ångströms (Å), where 1 Å equals 10^(-10) m [17]. Before calculating RMSD, the two structures must be optimally superimposed via a rigid body transformation (translation and rotation) that minimizes this very RMSD value. Algorithms such as the Kabsch algorithm or quaternion-based methods are commonly used for this purpose [17].

Atomic Selection Strategies

The choice of which atoms to include in the RMSD calculation is a critical methodological decision that can define the metric's relevance to the biological question at hand. The table below summarizes the common atomic selections and their primary applications.

Table 1: Standard Atomic Selections for RMSD Calculation

| Atomic Selection | Atoms Included | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cα Atoms | Cα only | Global fold comparison, protein folding studies, model validation in CASP [17]. | Simplified backbone representation; reduces noise from flexible side chains. | Insensitive to changes in side-chain orientations or backbone details. |

| Backbone Atoms | N, Cα, C, O | Refined backbone conformation analysis, loop modeling assessment. | More detailed description of the backbone geometry than Cα alone. | Can be skewed by mobile termini or flexible loops. |

| All Heavy Atoms | All non-hydrogen atoms | High-resolution comparison, ligand-binding site analysis, side-chain packing evaluation. | Most comprehensive structural assessment. | Highly sensitive to side-chain rotamer changes; can overstate differences. |

| Specific Subsets | User-defined (e.g., binding pocket residues, transmembrane helices) | Local structure validation, functional site analysis, domain movement studies [3]. | Directly targets a relevant region; minimizes dilution of signal by irrelevant regions. | Requires careful definition of the subset; results are specific to that region. |

Quantitative Comparison of Selection Impact

The choice of atomic selection directly influences the magnitude of the RMSD value and its statistical distribution. The following table synthesizes quantitative data from large-scale analyses to guide the interpretation of RMSD values.

Table 2: Interpretation of RMSD Values Based on Atomic Selection and Context

| Context | Cα RMSD Range (Å) | Interpretation | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Noise & Native Flexibility | 0 - 1.2 Å | Very similar structures; differences likely due to inherent flexibility or experimental resolution limits [3]. | Distribution for pairs of identical experimental PDB structures. |

| High-Quality Homology Models | ~2.3 Å | Representative of good model accuracy when a close homolog template is available (>40% sequence identity) [3]. | Comparison of best GPCR Dock 2010 models to experimental answers. |

| Structurally Similar Pairs | 1.0 - 3.0 Å | Moderate structural differences, potentially indicating biologically relevant conformational changes [2]. | General guidance for comparative analysis. |

| Substantial Structural Differences | >3.0 Å | Large conformational changes or potentially different folds [2]. | General guidance for comparative analysis. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Global RMSD for Model Validation

This protocol is designed for a standard assessment of a computational model against a reference experimental structure, commonly used in initiatives like CASP.

Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the PDB files for the reference structure and the model.

- Using a tool like MOPAC or a Python script, ensure both structures contain the same protein chain and residues. Remove non-protein atoms (water, ions, ligands) unless they are the specific focus of the study [18] [2].

- Verify that the sequence of residues is identical and the atom naming conventions are consistent between the two files.

Atomic Selection:

- For a global Cα RMSD, extract the coordinates of all Cα atoms from both structures.

- For a global backbone RMSD, extract the coordinates of the N, Cα, C, and O atoms for all residues.

Structure Superimposition:

- Apply an algorithm (e.g., Kabsch) to perform optimal rigid body superposition of the model onto the reference structure, using the selected atoms. The goal is to find the rotation and translation that minimizes the RMSD between the two sets of coordinates [17].

RMSD Calculation:

- Using the superimposed coordinates, calculate the RMSD via the standard formula.

- The final RMSD value is a single number representing the average distance between the selected atoms in the two structures after optimal alignment.

Protocol 2: Calculating Local RMSD for Functional Analysis

This protocol is used to focus on a specific, functionally important region of the protein, such as an active site or a binding pocket.

Region Definition:

- Identify the residues that constitute the region of interest (e.g., catalytic triad, ligand-binding pocket, a specific loop).

Structure Preparation and Trimming:

- Prepare the structures as in Protocol 1.

- Trim the structures to include only the defined subset of residues. Some tools automatically handle this when a residue list is provided [3].

Local Superimposition and Calculation:

- Option A (Recommended for local similarity): Superimpose the entire structures using the global method (Protocol 1), then calculate the RMSD only for the atoms in the local subset using the resulting coordinates.

- Option B (For isolated local comparison): Superimpose the structures using only the atoms in the local subset, then calculate the RMSD for that same subset. This ensures the alignment is optimized for the local region, ignoring the rest of the structure.

Interpretation:

- Compare the local RMSD to the global RMSD. A significantly lower local RMSD indicates that the region of interest is more accurately modeled or more structurally conserved than the protein as a whole.

Decision Workflow for Atomic Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate atoms for their RMSD calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Protein Structure Comparison and RMSD Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualization & Analysis Software | GUI-based structure visualization, superposition, and RMSD calculation. | Ideal for interactive analysis, visual inspection of alignments, and calculating RMSD on user-selected subsets. |

| GraSR [19] | Alignment-free Graph Neural Network | Fast protein structure comparison via learned representations. | Useful for extremely large-scale comparisons where traditional alignment is too slow; provides an alternative similarity metric. |

| SARST2 [16] | Structural Alignment Search Algorithm | Accurate and rapid alignment against massive databases. | Employs a filter-and-refine strategy, integrating primary to tertiary features for efficient database searches on ordinary computers. |

| EnsembleFlex [20] | Ensemble Analysis Suite | Analyzes conformational heterogeneity from structural ensembles. | Performs backbone and side-chain flexibility analysis via RMSD and RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) across multiple structures. |

| BioPython | Python Library | Programmatic parsing of PDB files and basic RMSD calculation. | Provides flexibility for custom analysis pipelines and batch processing of multiple structures. |

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) [3] | Superimposition Algorithm | Iterative method to find the largest superimposable core. | Attenuates the effect of outlier regions by focusing on locally similar segments, addressing a key drawback of global RMSD. |

Advanced Considerations and Complementary Metrics

While RMSD is a ubiquitous measure, it has known limitations. It is dominated by the largest errors in the structure, meaning that a single deviating loop can result in a high global RMSD, obscuring the high accuracy of the remainder of the model [3]. This is illustrated by pairs of structures like the active and inactive conformations of estrogen receptor α, which have a high global RMSD due to the movement of a single helix, making them indistinguishable by this metric alone from pairs with many small, scattered errors [3].

To address these issues, researchers should consider:

- Iterative Superimposition Methods: Algorithms like LGA (Local-Global Alignment) assign lower weights to the most deviating fragments, iteratively finding the largest superimposable core. This provides a more robust measure of similarity for proteins with localized flexibility [3].

- Complementary Metrics:

- TM-score: A superposition-based metric that is less sensitive to local errors and provides a more global measure of fold similarity.

- GDT (Global Distance Test): Measures the average percentage of residues under a specified distance cutoff, favored in CASP for model assessment [17] [3].

- Contact-Based Measures: These superimposition-independent methods quantify similarity based on residue-residue contact maps, making them robust against local structural variations [3].

The precise selection of atoms is not merely a technical prelude but the foundation of a biologically insightful RMSD analysis. A deliberate strategy—choosing Cα atoms for global fold assessment, backbone atoms for detailed backbone conformation, specific subsets for functional regions, and employing advanced methods to handle flexibility—ensures that the calculated RMSD accurately reflects the structural features of interest. By integrating these atomic selection protocols with an understanding of complementary metrics, researchers can leverage RMSD as a powerful, precise tool in structural biology and drug development.

The Critical Role of Optimal Superposition in RMSD Calculation

The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions is the cornerstone metric for quantifying geometric differences between two protein structures. Its calculation, however, is not merely a direct measurement of distances. It critically depends on first achieving an optimal superposition of the two structures, a process that aligns them in three-dimensional space to minimize the measured deviations between equivalent atoms [21]. This preliminary alignment is essential for ensuring that the resulting RMSD value reflects genuine structural differences rather than arbitrary rotational or translational orientations. Without this optimal superposition, RMSD values are mathematically inflated and biologically meaningless, as they include the distances required to move one structure onto the other.

The importance of this metric extends far beyond simple structure comparison. It is fundamental for understanding protein function, elucidating evolutionary relationships, analyzing molecular dynamics simulations, and aiding in drug design by comparing ligand-bound and unbound conformations [21]. This application note details the core principles, key methodologies, and practical protocols for performing optimal superposition to calculate RMSD, providing researchers with the tools to apply this technique accurately in their work.

Fundamental Principles and Analytical Solutions

The Mathematical Foundation of RMSD

For two sets of corresponding points (e.g., C-alpha atoms) from two protein structures, designated as the mobile set (\mathbf{A} = {\mathbf{a}1, \mathbf{a}2, ..., \mathbf{a}N}) and the reference set (\mathbf{B} = {\mathbf{b}1, \mathbf{b}2, ..., \mathbf{b}N}), the RMSD is formally defined after a rigid-body transformation is applied to (\mathbf{A}). This transformation consists of a rotation matrix (R) and a translation vector (\mathbf{t}). The RMSD is given by the formula:

[ \text{RMSD}(R, \mathbf{t}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} \| (R\mathbf{a}i + \mathbf{t}) - \mathbf{b}_i \|^2 } ]

The objective of optimal superposition is to find the specific rotation (R) and translation (\mathbf{t}) that globally minimize the value of this RMSD function [21]. The solution to this minimization problem is a well-established computational procedure.

The Kabsch Algorithm

The Kabsch algorithm provides an elegant, closed-form analytical solution to this minimization problem [21]. It is a deterministic and computationally efficient method that guarantees finding the optimal rotation and translation. The procedure follows these steps:

- Centering: Translate both the mobile set (\mathbf{A}) and the reference set (\mathbf{B}) so that their geometric centroids coincide at the origin of the coordinate system. This yields the centered coordinate sets (\mathbf{A}c) and (\mathbf{B}c), and solves for the optimal translation (\mathbf{t}) [21].

- Covariance Matrix Calculation: Compute the (3 \times 3) covariance matrix (\mathbf{H}) using the centered coordinates: (\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{A}c^T \mathbf{B}c) [21].

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): Perform SVD on the covariance matrix (\mathbf{H}), which decomposes it into three matrices: (\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{U} \Sigma \mathbf{V}^T) [21].

- Optimal Rotation Calculation: Calculate the optimal rotation matrix (R) as (R = \mathbf{V} \mathbf{U}^T). A critical check is performed on the determinant of (R) to ensure a proper rotation is obtained. If (\det(R) = -1), indicating a reflection, the sign of the last column of (\mathbf{V}) is inverted before recalculating (R) [21].

This algorithm serves as the gold standard for RMSD minimization and is embedded in countless structural bioinformatics software packages.

Advanced Superposition Frameworks

While the Kabsch algorithm is perfect for minimizing standard RMSD, modern computational challenges have spurred the development of more flexible frameworks.

A Gradient-Based Framework Using Lie Algebra

The Lie-RMSD framework reformulates the superposition problem to leverage modern gradient-based optimization [21]. Its key innovation is representing the rigid-body transformation (rotation and translation) as a single 6-dimensional vector in the Lie algebra (\mathfrak{se}(3)), which is the tangent space of the Special Euclidean group (SE(3)). This representation is fully differentiable, allowing the RMSD to be treated as a loss function that can be minimized by gradient-based optimizers like SGD, Adam, AdamW, and Sophia [21]. Although computationally more intensive than the analytical Kabsch solution, this framework's primary strength is its extensibility. It establishes a foundation for minimizing more complex, biologically relevant scoring functions (e.g., TM-score) that lack closed-form analytical solutions [21].

Handling Flexibility with Gaussian-Weighted RMSD

Standard RMSD is highly sensitive to outliers and local structural variations, such as flexible loops or hinged domain movements. To address this, the Gaussian-Weighted RMSD (wRMSD) method was developed [22]. Instead of selecting a subset of rigid residues, this method performs a superposition using all atoms. However, it assigns a weight to each atom based on its displacement between the two conformations. The weighting function ensures that atoms which move very little (the "static core") have a greater influence on the final superposition than atoms with large displacements [22]. This results in an alignment that better highlights the rigid-body relationship between two structures and the true range of flexibility in mobile regions.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Superposition Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of the Lie-RMSD framework, which uses gradient-based optimization, compared to the analytical Kabsch algorithm when aligning the allosteric conformations of Adenylate Kinase (PDB: 4AKE vs. 1AKE) [21].

Table 1: Benchmarking Results for Protein Structural Alignment (Adenylate Kinase)

| Method | Final RMSD (Å) | Difference from Kabsch (Å) | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kabsch (Ground Truth) | 7.130699 | — | 0.51 |

| Adam | 7.130700 | +0.000001 | 557.67 |

| SGD | 7.130702 | +0.000003 | 549.55 |

| Sophia | 7.130710 | +0.000011 | 587.31 |

| AdamW | 7.130717 | +0.000018 | 582.88 |

The data shows that all gradient-based optimizers successfully converged to the global minimum found by the Kabsch algorithm, achieving effectively identical precision. The minor deviations are attributable to floating-point precision and iterative termination conditions [21]. The key trade-off is computational time, with the gradient-based methods taking three orders of magnitude longer than the analytical method for this specific task.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic RMSD Calculation Using the Kabsch Algorithm

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for calculating the optimal RMSD between two protein structures with predefined atom correspondences.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protocol 1

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| C-alpha Atoms | Backbone atoms used to represent the protein fold; the most common choice for global structure comparison. |

| 3D Coordinate Sets | The input data: two sets of Cartesian coordinates for the mobile (A) and reference (B) structures. |

| Computational Environment | A scripting environment (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy) capable of linear algebra operations, particularly SVD. |

Input Preparation:

- Obtain the two protein structures (e.g., from PDB files).

- Select equivalent atoms (e.g., C-alpha atoms for backbone comparison).

- Ensure the two sets of coordinates (\mathbf{A}) and (\mathbf{B}) contain the same number of atoms (N) and are in the same sequential order.

Centering (Optimal Translation):

- Calculate the centroid for the mobile structure: (\text{centroid}A = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} \mathbf{a}_i).

- Calculate the centroid for the reference structure: (\text{centroid}B = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} \mathbf{b}_i).

- Center both sets by subtracting their respective centroids: (\mathbf{a}i^c = \mathbf{a}i - \text{centroid}A), (\mathbf{b}i^c = \mathbf{b}i - \text{centroid}B).

Optimal Rotation via Kabsch Algorithm:

- Compute the covariance matrix: (\mathbf{H} = (\mathbf{A}^c)^T \cdot \mathbf{B}^c).

- Perform Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on (\mathbf{H}): (\mathbf{U}, \Sigma, \mathbf{V}^T = \text{SVD}(\mathbf{H})).

- Calculate the optimal rotation matrix: (R = \mathbf{V} \cdot \mathbf{U}^T).

- Check for a reflection: if (\det(R) < 0), multiply the last column of (\mathbf{V}) by -1 and recalculate (R).

Transformation and RMSD Calculation:

- Apply the optimal transformation to the centered mobile coordinates: (\mathbf{A}^{\text{aligned}} = R \cdot \mathbf{A}^c + \text{centroid}_B).

- Calculate the final RMSD: (\text{RMSD} = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \| \mathbf{a}i^{\text{aligned}} - \mathbf{b}_i \|^2 }).

Protocol 2: Implementing the Lie-RMSD Framework

This protocol outlines the procedure for using the differentiable Lie-RMSD framework, which is particularly useful for testing custom loss functions [21].

Initialization:

- Represent the rigid-body transformation as a random or zero-initialized 6-dimensional vector (\mathbf{p} = (\boldsymbol{\omega}, \mathbf{u})) in (\mathfrak{se}(3)), where (\boldsymbol{\omega}) is rotation and (\mathbf{u}) is translation.

- Center the coordinate sets (\mathbf{A}) and (\mathbf{B}) as described in Protocol 1.

Optimization Loop:

- Transformation: For the current parameters (\mathbf{p}), compute the rotation matrix (R) via the exponential map of the skew-symmetric matrix ([\boldsymbol{\omega}]_{\times}). Generate transformed coordinates: (\mathbf{A}^{\text{transformed}} = R(\boldsymbol{\omega}) \cdot \mathbf{A}^c + \mathbf{t}).

- Loss Calculation: Compute the RMSD between (\mathbf{A}^{\text{transformed}}) and (\mathbf{B}^c), which serves as the loss function.

- Gradient Calculation: Use automatic differentiation (e.g., in PyTorch) to compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the parameters (\mathbf{p}).

- Parameter Update: Update the parameters (\mathbf{p}) using a gradient-based optimizer (e.g., Adam, SGD) for a specified number of steps or until convergence.

Validation:

- Validate the results by comparing the final RMSD and the superimposed structures against the output of the Kabsch algorithm.

The workflow below illustrates the logical relationship and decision path between the two protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for Protein Structural Alignment

| Tool/Algorithm | Type | Primary Function in Superposition |

|---|---|---|

| Kabsch Algorithm [21] | Analytical Solution | Provides a closed-form, optimal solution for RMSD minimization. |

| Lie-RMSD [21] | Differentiable Framework | Represents superposition as a differentiable optimization problem for flexibility. |

| Gaussian-wRMSD [22] | Weighted Alignment | Performs superposition weighted by structural conservation, reducing noise from flexible regions. |

| TM-align [16] | Advanced Heuristic | Uses heuristic iteration and dynamic programming to maximize TM-score, a different similarity metric. |

| GraSR [23] | Alignment-Free ML | Uses Graph Neural Networks to learn structural representations, bypassing superposition for rapid retrieval. |

| SARST2 [16] | Database Search | Employs a filter-and-refine strategy with machine learning for rapid large-scale structural similarity searches. |

Optimal superposition is not merely a preliminary step but the very foundation of a meaningful RMSD calculation. The Kabsch algorithm remains the gold standard for this task due to its precision and computational efficiency. However, emerging challenges in structural biology, such as the need to compare predicted models from AlphaFold DB and analyze flexible systems, demand more sophisticated tools [16] [22]. Modern frameworks like Lie-RMSD, which leverage automatic differentiation and Lie algebra, provide the flexibility to optimize beyond RMSD. Similarly, methods like wRMSD offer robust ways to handle conformational flexibility. As the volume of structural data continues to grow, the principles of optimal superposition will remain critical, even as they are embedded within faster, more powerful, and more biologically insightful structural comparison pipelines.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating RMSD: From Theory to Practice

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in structural biology for quantifying the similarity between two molecular structures by measuring the average distance between equivalent atoms after optimal superposition [17]. It is extensively used to compare protein conformations, assess the quality of predicted models against experimental structures, and analyze conformational changes in molecular dynamics simulations [24] [17]. This guide provides a standardized, step-by-step protocol for calculating RMSD, enabling researchers to consistently perform and interpret this essential structural analysis.

Theoretical Foundation of RMSD

Mathematical Definition

The standard RMSD calculation involves a rigid-body superposition of two sets of equivalent atomic coordinates, followed by the computation of the average atomic displacement. For two sets of points, v and w, each containing n equivalent atoms, the RMSD is defined as [17]:

RMSD(v,w) = √( (1/n) × Σ ||vᵢ - wᵢ||² )

This equation calculates the square root of the mean squared distance between corresponding atoms after the structures have been optimally aligned. The most common atoms used for this calculation in proteins are the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O) or specifically the Cα atoms [24] [17].

Key Concepts in Superposition

A critical prerequisite for RMSD calculation is the optimal rigid-body transformation—comprising rotation and translation—that minimizes the RMSD between the two structures. This is typically solved using established algorithms like the Kabsch algorithm or quaternion-based methods [17]. It is crucial to distinguish between the atoms used for the superposition (the fitting set) and the atoms used for the final RMSD calculation, which can be identical or different. For instance, a structure is often fitted on the backbone atoms, but the RMSD can be computed for the backbone or the entire protein [24].

Computational Protocols

A Generalized Workflow for RMSD Calculation

The following diagram outlines the core steps for calculating RMSD between two protein structures, from data preparation to interpretation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Input Structure Preparation

- Obtain Structures: Acquire 3D atomic coordinates in PDB or mmCIF format from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or homology modeling servers (e.g., SWISS-MODEL, AlphaFold) [10] [25].

- Select Chains and Residues: Specify the polymer chain(s) and residue ranges for comparison. The selected chain must be at least 10 residues long and contain coordinates for Cα atoms [10].

- Curate Atoms: Remove heteroatoms (water, ligands) and select relevant atoms for analysis (e.g., protein backbone, Cα only, or all atoms).

Step 2: Atom Selection and Correspondence

- Define Equivalent Atoms: Establish a residue-to-residue correspondence, which can be sequence-dependent (sequential) or independent (non-sequential) [26] [10].

- Choose Atom Set: Select the atomic coordinates for calculation. Using only Cα atoms is common for a global backbone comparison.

Step 3: Structural Superposition

- Center Structures: Translate both structures so their geometric centers (centroids) coincide at the origin.

- Compute Optimal Rotation: Apply the Kabsch algorithm to find the rotation matrix that minimizes the RMSD between the two coordinate sets [17].

Step 4: RMSD Computation

- Apply Transformation: Rotate the target structure using the optimal rotation matrix.

- Compute the Final Value: Use the standard RMSD formula to calculate the value, typically reported in Ångströms (Å).

Selecting an Appropriate Algorithm

Different alignment algorithms are suited for different scenarios. The table below summarizes common methods available through the RCSB PDB Pairwise Structure Alignment tool [10].

Table 1: Common Structural Alignment Algorithms for RMSD Calculation

| Algorithm | Alignment Type | Key Features | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| jFATCAT-rigid [10] | Rigid-body | Identifies largest structurally conserved core; sequence-order dependent. | Comparing closely related proteins with minimal conformational changes. |

| jFATCAT-flexible [10] | Flexible | Introduces twists (hinges) to align rigid domains independently. | Comparing proteins with large internal conformational changes (e.g., upon ligand binding). |

| jCE [10] | Rigid-body | Combines similar local structure segments to maximize aligned residues. | General-purpose, sequence-order dependent alignment of globular proteins. |

| jCE-CP [10] | Flexible | Allows for circular permutations and different loop topologies. | Comparing proteins with similar shapes but different backbone connectivity. |

| TM-align [10] | Rigid-body | Sequence-independent; sensitive to global topology. | Comparing proteins with similar folds, even with low sequence similarity. |

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful RMSD analysis relies on both reliable data and robust software tools.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Protein Structure Comparison and RMSD Calculation

| Resource Category | Example | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [10] | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. |

| Homology Modeling Servers | SWISS-MODEL [25] | Fully automated protein structure homology-modelling server for generating 3D models from amino acid sequences. |

| Predicted Structure Databases | AlphaFold DB [10] [25] | Database of highly accurate predicted protein structures generated by AlphaFold2, accessible as templates or for direct comparison. |

| Structure Alignment Tools | RCSB PDB Pairwise Structure Alignment [10] | Web-accessible interface providing multiple algorithms (jFATCAT, jCE, TM-align) for structural superposition and RMSD calculation. |

| Standalone Software | GROMACS (gmx rms) [24] |

Molecular dynamics package with built-in tools for calculating RMSD, including least-squares fitting and fit-free methods. |

Data Interpretation and Reporting

Interpreting RMSD Values

The absolute RMSD value provides a quantitative measure of structural similarity. Lower values indicate higher similarity. As a general guideline:

- RMSD < 1.0 - 2.0 Å: Often considered a high-quality match for closely related proteins or accurate model predictions, especially when superimposed on stable core regions [27] [28].

- RMSD ~ 2.0 - 4.0 Å: Typical for structures with the same overall fold but some structural variations, such as loop movements or differences between bound and unbound forms.

- RMSD > 4.0 Å: May suggest different folds or significant structural rearrangements, though contextual factors like the length and flexibility of the aligned region must be considered.

Complementary Metrics

While RMSD is a standard measure, it is sensitive to local errors and can be dominated by a small subset of poorly aligned residues. Reporting complementary metrics provides a more comprehensive assessment [10]:

- TM-score: A topology-based measure that is less sensitive to local variations. A score >0.5 generally indicates the same protein fold, while a score <0.2 suggests unrelated structures [10].

- Sequence Identity: The percentage of identical residues in the structural alignment.

- Number of Equivalent Residues: The count of residue pairs deemed structurally equivalent by the alignment algorithm.

Application Notes

Example: Benchmarking Model Accuracy

A primary application of RMSD is validating computationally predicted protein structures. For instance, the Protein Models Docking Benchmark 2 was created by generating protein models with Cα RMSD to native structures in the 1 to 6 Å range, providing a standardized set for testing docking methods [27]. In such a benchmark:

- Procedure: Generate a 3D model of a protein with a known experimental structure (the "native" or "target").

- Alignment: Superimpose the model onto the native structure using a rigid-body alignment on all Cα atoms.

- Calculation: Compute the Cα RMSD for the entire chain or a specific domain.

- Interpretation: A lower global Cα RMSD typically indicates a more accurate model, with values below ~2 Å often considered high-quality for the core structural regions [27].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- High RMSD Due to Flexible Regions: If a structure has highly flexible termini or loops, they can disproportionately inflate the RMSD. Consider calculating RMSD only on well-structured core regions.

- Effect of Alignment Size: The RMSD value is influenced by the number of atoms included. Always report the number of equivalent residues used in the calculation for context [10].

- Choice of Reference Atoms: Be consistent in the atoms selected for comparison (e.g., always Cα or always backbone) across different analyses to ensure results are comparable.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in structural biology and computational chemistry, providing a quantitative measure of the average distance between the atoms of two superimposed molecular structures [2]. The calculation of RMSD is a critical step in numerous research applications, including the analysis of protein conformational changes, validation of predicted protein models against experimental structures, assessment of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation trajectories, and evaluation of docking poses in drug design [2] [3]. The mathematical formula for RMSD is expressed as the square root of the average of the squared distances between corresponding atoms: RMSD = √[ (1/N) * Σ(d_i)² ], where N is the number of atoms, and d_i is the distance between the i-th pair of corresponding atoms [3] [29].

However, a raw RMSD calculation can be misleading unless the structures are optimally superimposed to minimize the influence of overall translation and rotation in 3D space [30] [31]. Furthermore, challenges such as differing atom ordering between structure files or the presence of symmetric atoms in ligands can artificially inflate RMSD values if not properly addressed [29]. Consequently, the choice of software is paramount, as robust tools automatically perform necessary pre-processing steps—including structural alignment, atom mapping, and symmetry correction—to ensure the resulting RMSD value accurately reflects genuine structural differences [30] [29]. This application note provides a structured overview of available software and servers, detailed protocols, and data interpretation guidelines to empower researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific research context.

Key Considerations and Limitations of RMSD

Before selecting a tool, researchers must understand both the power and the limitations of the RMSD measure. A significant drawback of global RMSD is its sensitivity to outliers; it is dominated by the largest deviations in the structure [3]. For instance, a single flexible loop or terminal region with high conformational freedom can disproportionately increase the global RMSD, masking a high degree of similarity in the structural core [3]. This makes global RMSD a potentially poor indicator of overall structural similarity, especially for flexible proteins or multi-domain proteins with relative domain movements.

To address this, researchers often employ alternative strategies. Local RMSD analysis can be performed on specific regions of interest, such as a binding pocket or a protein domain, to focus on functionally relevant areas [3]. Additionally, alternative metrics have been developed. Template Modeling Score (TM-score) and MaxSub are two such measures that are less sensitive to local errors because they are designed to identify the largest subset of residues that can be superimposed within a defined distance threshold [32]. The TM-score is particularly valuable as it is normalized by protein length, providing a more universal scale where a score above 0.5 generally indicates the same fold, and a score below 0.17 corresponds to random similarity [32].

Another critical consideration is molecular symmetry. For symmetric molecules, such as benzene or ibuprofen, multiple, chemically equivalent atomic mappings are possible [29]. A naïve RMSD calculation that relies on the atom order in the input files can yield an artificially high value. Specialized tools like DockRMSD are essential in these scenarios, as they solve the graph isomorphism problem to find the minimal RMSD based on all possible physically allowed atomic mappings that respect the molecular bonding network [29].

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for RMSD and Alternative Metrics

| Metric | Typical Range for Similar Structures | Interpretation and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Global Cα RMSD | 0 - 1.2 Å [3] | Values in this range often reflect inherent protein flexibility or minor experimental differences. Values > 2-3 Å typically indicate significant conformational changes or potential alignment issues [2] [3]. |

| Local RMSD | Varies by region | Focuses on a specific functional site (e.g., active site). Useful for docking validation when global RMSD is high due to flexible regions. |

| TM-score | 0.5 - 1.0 [32] | A score > 0.5 indicates the same fold; < 0.17 suggests random similarity. Length-normalized and more robust to local errors than RMSD. |

| MaxSub Score | 0.0 - 1.0 [32] | Identifies the largest subset of residues fitting under a distance cutoff. A value of 1 indicates an identical pair of structures. |

Software and Server Toolkit for RMSD Calculation

A wide array of tools is available for calculating RMSD, ranging from simple command-line scripts to complex visualization suites with integrated analysis. The choice depends on the user's specific task, such as comparing a few structures versus processing thousands, or working with simple proteins versus symmetric small molecules.

Table 2: Software Toolkit for RMSD Calculation

| Tool Name | Primary Use Case & Description | Key Features | Format Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| rmsd (Python) [30] [31] | Command-line tool for fast, optimal RMSD. Ideal for batch processing and scripts. | Handles translation/rotation; atom reordering; ignores hydrogens. | .xyz, .pdb |

| DockRMSD [29] | Specialized for symmetric ligands in docking poses. Critical for drug development. | Graph isomorphism for physical atom mapping; deterministic minimal RMSD. | .mol2 |

| MaxCluster [32] | Protein-specific comparison & clustering. Excellent for large-scale model assessment. | RMSD, TM-score, MaxSub; sequence-dependent/independent alignment; clustering. | .pdb |