How to Detect Batch Effects in RNA-seq Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This comprehensive guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with current methodologies for detecting, troubleshooting, and correcting batch effects in RNA-seq data.

How to Detect Batch Effects in RNA-seq Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with current methodologies for detecting, troubleshooting, and correcting batch effects in RNA-seq data. Covering both foundational concepts and advanced techniques, the article explores visual detection methods like PCA, statistical approaches including machine learning-based quality assessment, and comparative analysis of correction tools like ComBat-ref, Harmony, and sysVI. With practical implementation guidance and validation strategies, this resource addresses the critical challenge of distinguishing technical artifacts from true biological signals to ensure reliable transcriptomic analysis and reproducible research findings.

Understanding Batch Effects: Sources, Impact, and Detection Fundamentals

In molecular biology, a batch effect occurs when non-biological factors in an experiment cause systematic technical variations in the produced data. These effects can lead to inaccurate conclusions when their causes are correlated with one or more outcomes of interest and are particularly common in high-throughput sequencing experiments like RNA-seq [1]. Batch effects represent a critical challenge in genomics research because they can obscure true biological signals and result in spurious findings if not properly addressed [2]. The term "batch effect" encompasses the systematic technical differences when samples are processed and measured in different batches, unrelated to any biological variation recorded during the experiment [1].

Batch effects in RNA-seq experiments originate from multiple technical sources throughout the experimental workflow. Understanding these sources is essential for both preventing and correcting batch effects.

Common causes include:

- Different sequencing runs or instruments across experiments

- Variations in reagent lots or manufacturing batches [1] [2]

- Changes in sample preparation protocols between processing batches

- Personnel differences when different technicians handle samples [1]

- Environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity fluctuations [2]

- Time-related factors when experiments span weeks or months [2]

- Laboratory conditions where the experiment was conducted [1]

- Atmospheric factors such as ozone levels that may affect certain measurements [1]

These technical variations can create significant artifacts in data that may be mistakenly interpreted as biological signals if not properly addressed [2]. In the context of sequencing data, even two runs at different time points can already show a batch effect [3].

Impact on RNA-seq Data Analysis

The presence of batch effects has profound implications for RNA-seq data analysis and interpretation, potentially compromising research validity.

Key impacts include:

- Differential expression analysis may identify genes that differ between batches rather than between biological conditions [2]

- Clustering algorithms might group samples by batch rather than by true biological similarity [2]

- Pathway enrichment analysis could highlight technical artifacts instead of meaningful biological processes [2]

- Meta-analyses combining data from multiple sources become particularly vulnerable to batch effects [2]

- Reduced statistical power to detect truly differentially expressed genes [4]

- False discoveries where technical variations are misinterpreted as biological findings [3] [5]

Batch effects are known to interfere with downstream statistical analysis by introducing differentially expressed genes between groups that are only detected between batches but have no biological meaning. Conversely, careless correction of batch effects can result in loss of biological signal contained in the data [3].

Detection Methods for Batch Effects

Visualization Approaches

Effective detection of batch effects begins with visualization techniques that reveal systematic technical variations.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is performed on raw single-cell data to identify batch effects through analysis of the top principal components. The scatter plot of these top PCs reveals variations induced by the batch effect, showcasing sample separation attributed to distinct batches rather than biological sources [5].

t-SNE/UMAP Plot Examination involves performing clustering analysis and visualizing cell groups on a t-SNE or UMAP plot. This visualization includes labeling cells based on their sample group and batch number before and after batch correction. The rationale is that, in the presence of uncorrected batch effects, cells from different batches tend to cluster together instead of grouping based on biological similarities. After batch correction, the expectation is a cohesive clustering without such fragmentation [5].

Quantitative Assessment Metrics

Quantitative metrics provide objective measures for evaluating batch effect presence and correction efficacy.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) | Compares clustering similarity to known batches | Values closer to 0 indicate better batch mixing [6] [5] |

| Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | Measures similarity between two data clusterings | Higher values indicate better biological preservation [5] |

| kBET | k-nearest neighbor batch effect test | Tests whether batches are well-mixed in local neighborhoods [5] |

| Graph iLISI | Graph-based integrated local similarity inference | Evaluates batch composition in local neighborhoods of cells [6] |

| PCR_batch | Percentage of corrected random pairs within batches | Measures integration of batches [5] |

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances include machine learning-based quality assessment for detecting batch effects. Researchers have developed statistical guidelines and a machine learning tool to automatically evaluate the quality of a next-generation-sequencing sample. This approach leverages quality assessment to detect and correct batch effects in RNA-seq datasets with available batch information [7] [3].

The workflow involves deriving features from FASTQ files using multiple bioinformatic tools, then using a random forest classifier to compute Plow (the probability of a sample to be of low quality). This quality score can distinguish batches and be used to correct batch effects in sample clustering [7].

Batch Effect Correction Methods

Computational Correction Algorithms

Multiple computational methods have been developed specifically for batch effect correction in RNA-seq data.

Table 2: Batch Effect Correction Methods for RNA-seq Data

| Method | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-seq [8] [4] | Empirical Bayes with negative binomial model | Preserves integer count data; uses empirical Bayes framework | Bulk RNA-seq count data |

| ComBat-ref [8] [4] | Enhanced ComBat-seq with reference batch | Selects batch with smallest dispersion as reference; adjusts other batches toward it | Bulk RNA-seq with improved sensitivity |

| removeBatchEffect (limma) [2] | Linear model adjustment | Works on normalized expression data; integrated with limma-voom workflow | Bulk RNA-seq with normalized data |

| Harmony [5] | Iterative clustering with PCA | Iteratively removes batch effects by clustering similar cells across batches | Single-cell and bulk RNA-seq |

| Seurat 3 [5] | Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) and MNN | Uses CCA to project data into subspace; MNN as anchors to correct batches | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| sva package [1] [3] | Surrogate variable analysis | Detects and corrects effects from unknown sources of variation | Bulk RNA-seq with unknown batch sources |

Reference-Based Correction with ComBat-ref

ComBat-ref represents an advanced batch effect correction method that builds upon ComBat-seq but incorporates key improvements. It employs a negative binomial model for count data adjustment but innovates by selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion, preserving count data for the reference batch, and adjusting other batches toward the reference batch [4].

The method models RNA-seq count data using a negative binomial distribution, with each batch potentially having different dispersions. For a gene g in batch j and sample i, the count nijg is modeled as:

nijg ~ NB(μijg, λig)

where μijg is the expected expression level of gene g in sample j and batch i, and λig is the dispersion parameter for batch i [4].

ComBat-ref demonstrates superior performance in both simulated environments and real-world datasets, significantly improving sensitivity and specificity compared to existing methods. By effectively mitigating batch effects while maintaining high detection power, ComBat-ref provides a robust solution for improving the accuracy and interpretability of RNA-seq data analyses [8] [4].

Integration in Differential Expression Analysis

Rather than correcting the data before analysis, a statistically sound approach is to incorporate batch information directly into differential expression models.

Including batch as a covariate in differential expression analysis frameworks like DESeq2 and edgeR is a common approach that accounts for batch effects without transforming the underlying data [2] [4].

Surrogate variable analysis is particularly useful when batch information is incomplete or unknown, as it can detect and adjust for unknown sources of technical variation [3] [2].

Experimental Design Considerations

Proactive Batch Effect Prevention

Proper experimental design can significantly reduce batch effects before computational correction becomes necessary.

Key strategies include:

- Randomization of samples across processing batches to avoid confounding biological conditions with technical batches

- Balanced design ensuring each biological group is represented in each processing batch

- Quality control of reagents and consistency in protocol application across batches

- Metadata collection of detailed information about processing conditions for each sample

While these effects can be minimized by good experimental practices and a good experimental design, batch effects can still arise regardless and it can be difficult to correct them [3].

Quality Control Integration

Integrating quality control metrics with batch effect correction enhances the effectiveness of both processes. Studies have shown that batch effects correlate with differences in quality metrics, though they also arise from other artifacts [7] [3].

The transcript integrity number (TIN) is a widely used measure of RNA integrity, representing the percentage of transcripts that have uniform read coverage across the genome. The median TIN score across all transcripts is commonly used to indicate the RNA integrity of each sample, and low-quality samples with low integrity should be removed before downstream analysis [9].

Validation and Overcorrection Risks

Assessing Correction Effectiveness

After applying batch effect correction methods, validation is essential to ensure technical artifacts have been removed without eliminating biological signals.

Effective validation approaches include:

- Visual inspection of PCA and t-SNE/UMAP plots post-correction

- Quantitative metrics calculation before and after correction

- Biological validation confirming known biological signals persist after correction

- Differential expression analysis to ensure expected biological differences remain detectable

Recognizing and Avoiding Overcorrection

Overcorrection represents a significant risk in batch effect correction, where true biological variation is inadvertently removed along with technical artifacts.

Signs of overcorrection include:

- A significant portion of cluster-specific markers comprising genes with widespread high expression across various cell types, such as ribosomal genes [5]

- Substantial overlap among markers specific to clusters [5]

- Notable absence of expected cluster-specific markers; for instance, the lack of canonical markers for a particular T-cell subtype known to be present in the dataset [5]

- The scarcity or absence of differential expression hits associated with pathways expected based on the composition of samples in terms of cell types and experimental conditions [5]

The single-cell community is moving towards large-scale atlases that aim to combine a broad set of data, which complicates integration due to increasing data complexity and substantial batch effects. Thus, it is crucial to assess how different integration strategies perform in specific experimental contexts [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Batch Effect Management

| Item | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [4] | Software package | Differential expression analysis with batch covariate inclusion | Bulk RNA-seq analysis |

| edgeR [4] | Software package | Differential expression analysis accounting for batch effects | Bulk RNA-seq analysis |

| sva package [1] [3] | R/Bioconductor package | Surrogate variable analysis for unknown batch effects | Bulk RNA-seq with unknown batches |

| Harmony [5] | Integration algorithm | Iterative batch effect removal using clustering | Single-cell and bulk RNA-seq |

| Seurat [5] | Software suite | Single-cell analysis with CCA and MNN-based integration | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| STAR [9] | Alignment software | Read alignment with quality metrics output | RNA-seq preprocessing |

| RseQC [9] | Quality control package | RNA-seq quality metrics including TIN scores | Quality assessment |

| ComBat-seq [8] [4] | Batch correction | Empirical Bayes method for count data | Bulk RNA-seq count correction |

Batch effects represent a fundamental challenge in RNA-seq experiments that can compromise data reliability and lead to inaccurate biological conclusions. Effective management of batch effects requires a comprehensive approach spanning experimental design, detection methods, computational correction, and validation. While methods like ComBat-ref, sva, and Harmony offer powerful correction capabilities, researchers must remain vigilant about overcorrection risks that might remove biological signals along with technical noise. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and datasets grow in complexity, robust batch effect management will remain essential for generating biologically meaningful and reproducible results in transcriptomics research.

Batch effects are systematic, non-biological variations introduced into RNA-seq data during the experimental workflow, which can confound downstream analysis and lead to irreproducible results [10]. These technical artifacts arise from various sources, including differences in reagent lots, sequencing runs, and environmental conditions, creating patterns in the data that can be mistakenly interpreted as biological signals [2] [10]. The profound negative impact of batch effects extends to virtually all aspects of RNA-seq analysis, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions in differential expression analysis, clustering artifacts in dimensionality reduction, and false discoveries in pathway enrichment studies [2] [10]. In translational research settings, undetected batch effects have resulted in serious consequences, including incorrect patient classifications and unnecessary treatments [10]. Understanding these sources is therefore fundamental to ensuring data reliability and biological validity in transcriptomics research.

Reagent-Related Batch Effects

Reagent-related variations represent one of the most prevalent sources of batch effects in RNA-seq workflows. Different lots of common reagents, including reverse transcription enzymes, purification kits, and buffer solutions, can introduce systematic technical variations due to manufacturing inconsistencies [2] [11]. These differences in chemical purity, enzymatic efficiency, and buffer composition ultimately affect cDNA synthesis, library preparation efficiency, and sequencing output [11]. In single-cell RNA-seq, these effects are further amplified due to lower RNA input requirements and higher sensitivity to technical variations [10] [5]. The impact of reagent batch effects can be substantial, with documented cases where changes in RNA-extraction solutions resulted in significant shifts in gene expression profiles, leading to incorrect clinical interpretations [10].

Table 1: Common Reagent-Related Batch Effects and Their Impacts

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Impact | Applicable RNA-seq Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Batches | Reverse transcriptase, Polymerases | cDNA yield, amplification bias | Bulk & single-cell RNA-seq |

| Nucleotide Mixes | dNTPs, modified nucleotides | Incorporation efficiency, error rates | Bulk & single-cell RNA-seq |

| Library Prep Kits | Isolation, purification, quantification kits | Library complexity, insert size distribution | Primarily bulk RNA-seq |

| Chemical Reagents | Buffer solutions, purification beads | Recovery efficiency, sample purity | All types |

| Single-cell Specific | Barcoding reagents, cell lysis solutions | Cell recovery, mRNA capture efficiency | scRNA-seq & spatial transcriptomics |

Sequencing Run-Related Batch Effects

Sequencing platform variations introduce another major category of batch effects in RNA-seq data. These effects manifest through differences between instruments, flow cell lots, sequencing chemistries, and software versions [2] [11]. Instrument-specific variations include calibration differences, optical sensor variations, and lane effects within flow cells, which collectively contribute to non-biological variability across sequencing runs [12]. The timing of sequencing runs also plays a crucial role, as even the same instrument used at different time points can generate batch effects due to maintenance procedures, aging components, or environmental fluctuations [12]. In single-cell RNA-seq, these effects are compounded by higher technical variations, including lower RNA input, increased dropout rates, and greater cell-to-cell variability compared to bulk RNA-seq [10]. The combinatorial nature of these technical variations creates complex batch effect patterns that require sophisticated detection and correction strategies.

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Batch Effects and Characteristics

| Sequencing Factor | Technical Variations | Data Impact | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument Type | Machine model, manufacturing specifications | Base calling differences, quality score variation | Inter-platform comparisons, PCA |

| Flow Cell Lots | Manufacturing batch, quality control metrics | Cluster density variations, signal intensity differences | Lane-specific clustering, quality metrics |

| Sequencing Chemistry | Reagent versions, kit lots | Read length distribution, error profiles | Quality control plots, error rate analysis |

| Software Versions | Base calling algorithms, processing pipelines | Read mapping rates, quantification differences | Version-controlled reanalysis, data reprocessing |

| Run Timing | Maintenance cycles, component aging | Quality score decay, increasing error rates | Time-series analysis, control sample monitoring |

Environmental and Operational Batch Effects

Environmental conditions and human operational factors constitute a third major category of batch effect sources in RNA-seq studies. Temperature and humidity fluctuations during sample processing can affect enzyme kinetics and reaction efficiencies, particularly during critical steps like cDNA synthesis and library amplification [2] [11]. Temporal factors are equally important, as experiments conducted over extended periods (weeks or months) often exhibit time-dependent technical variations, even when using identical protocols and reagents [2]. Personnel-related variations represent another significant source, where differences in technical expertise, pipetting techniques, and protocol adherence among laboratory staff can introduce operator-specific batch effects [2] [11]. These environmental and operational factors often interact in complex ways, creating batch effects that are challenging to model and correct in downstream analyses.

Detection Methodologies for Batch Effects

Visualization-Based Detection Approaches

Visualization methods provide powerful, intuitive approaches for detecting batch effects in RNA-seq data. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) represents the most widely used technique, where samples are projected into a low-dimensional space based on their global gene expression patterns [2] [5] [13]. In the presence of batch effects, samples typically cluster by technical factors (e.g., sequencing run or reagent lot) rather than biological conditions in the PCA plot [2] [13]. For example, a PCA analysis of public RNA-seq data (GSE48035) clearly demonstrated that samples separated primarily by library preparation method (ribo-depletion vs. polyA-enrichment) rather than biological condition (UHR vs. HBR), revealing a pronounced batch effect [13]. More advanced visualization techniques include t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), which are particularly valuable for single-cell RNA-seq data [5] [11]. These nonlinear dimensionality reduction methods can reveal complex batch effect patterns that might be obscured in PCA visualizations, especially in high-dimensional single-cell datasets characterized by significant technical noise and dropout events [5].

Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

Quantitative metrics provide objective, statistical measures for assessing batch effect severity and evaluating correction efficacy. The k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET) quantifies batch mixing by testing whether the local neighborhood composition of batches matches the global expected distribution [5] [14]. The Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI) measures both batch mixing (batch LISI) and cell-type separation (cell-type LISI), with higher values indicating better integration and biological preservation [14]. Additional metrics include the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which assesses clustering similarity before and after correction, and the Average Silhouette Width (ASW), which evaluates separation quality between biological groups while accounting for batch mixing [11]. These quantitative approaches are particularly valuable for large-scale studies and method comparisons, as they provide standardized, reproducible measures of batch effect impact independent of visual interpretation biases. For example, benchmark studies evaluating 14 different batch correction methods on single-cell data from the Mouse Cell Atlas utilized these metrics to objectively compare method performance across multiple datasets [11].

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| kBET (k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test) | Tests local batch distribution against expected global distribution | Rejection rate indicates batch effect severity | Lower rejection rate = better mixing |

| LISI (Local Inverse Simpson's Index) | Measures diversity of batches in local neighborhoods | Higher values indicate better batch mixing | Higher score = better integration |

| ARI (Adjusted Rand Index) | Compares clustering similarity with known biological labels | Measures biological structure preservation | Higher value = better biological preservation |

| ASW (Average Silhouette Width) | Computes average distance between similar vs dissimilar clusters | Assesses both batch mixing and biological separation | Higher absolute value = better separation |

| Normalized Mutual Information | Measures information sharing between batch and cluster assignments | Quantifies batch contribution to clustering | Lower value = less batch influence |

Experimental Controls for Batch Effect Detection

Well-designed experimental controls provide critical reference points for detecting and quantifying batch effects. The inclusion of technical replicates across batches allows researchers to distinguish technical variations from biological signals by measuring expression differences in genetically identical samples processed separately [11]. Reference samples, such as standardized RNA controls or commercially available reference materials (e.g., Universal Human Reference RNA), enable direct comparison across batches, platforms, and laboratories by providing a constant benchmark against which technical variations can be quantified [13]. Balanced experimental designs, where biological conditions are evenly distributed across batches, facilitate proper statistical modeling of batch effects by ensuring that technical factors are not confounded with biological variables of interest [11] [13]. For example, in the ABRF Next-Generation Sequencing Study, the use of standardized UHR and HBR reference samples across multiple platforms and laboratories enabled systematic quantification of batch effects arising from different sequencing technologies and library preparation methods [13].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Reagents and Materials

Successful management of batch effects requires careful selection and consistent application of laboratory reagents and materials throughout the RNA-seq workflow. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions and their specific functions in mitigating batch effects.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Mitigation

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Batch Effect Considerations | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from samples | Use single manufacturing lot for entire study; validate performance | Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN); quantify yield |

| Library Preparation Kits | cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, library amplification | Standardize using kits from single lot; avoid version changes | Assess library complexity; verify size distribution |

| Quantification Reagents | Fluorometric or spectrophotometric nucleic acid quantification | Use consistent quantification method and reagents | Include standard curves; use multiple quantification methods |

| Enzyme Batches | Reverse transcription, amplification, fragmentation | Aliquot and use single batches across experiments | Test enzyme activity with control RNA |

| Sequencing Flow Cells | Platform for cluster generation and sequencing | Distribute samples randomly across flow cells and lanes | Monitor cluster density; track quality metrics |

| Buffer Solutions | Reaction environments for various workflow steps | Prepare master mixes from single component lots | pH verification; conductivity testing |

| Barcoding Reagents (scRNA-seq) | Cell-specific labeling in single-cell experiments | Use consistent barcode lots to minimize batch-specific effects | Assess multiplet rates; check barcode distribution |

| Control RNA Samples | Reference standards for cross-batch normalization | Use commercially available standardized reference materials | Monitor expression stability of housekeeping genes |

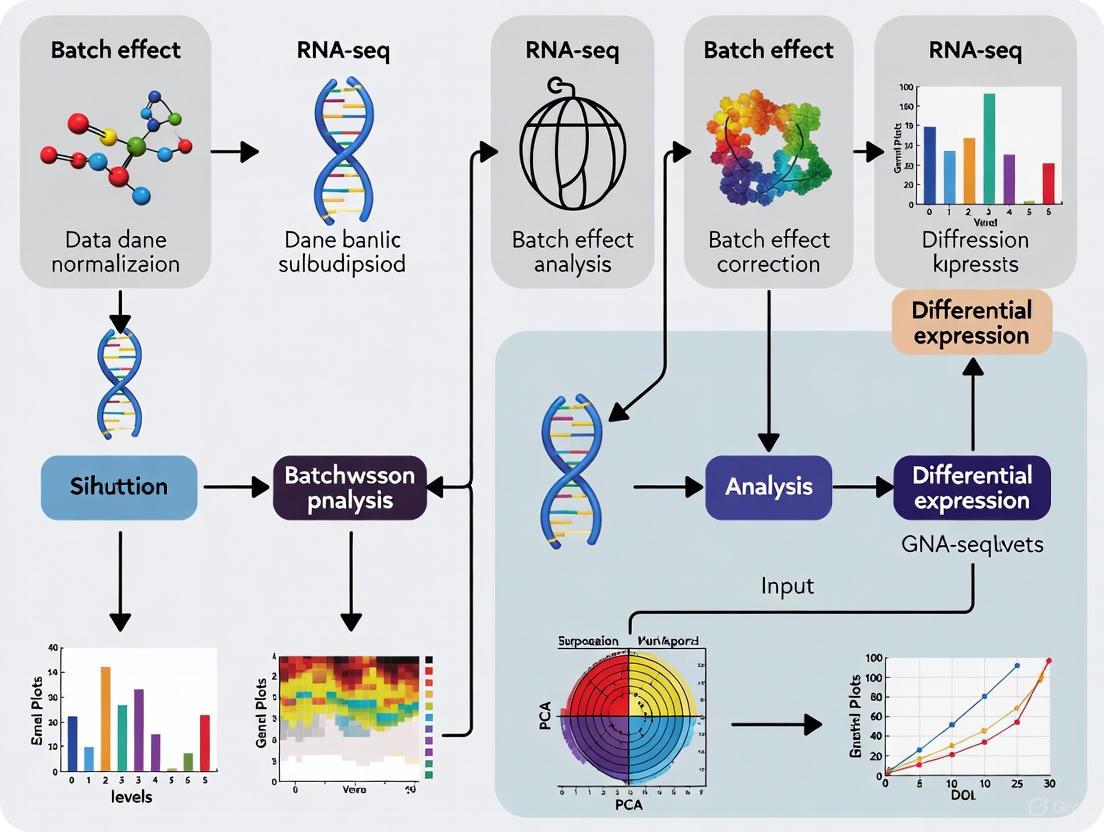

Integrated Workflow for Batch Effect Management

A comprehensive approach to batch effect management requires integration of preventive experimental design with rigorous analytical validation. The following workflow diagram illustrates the interconnected processes for addressing batch effects throughout the RNA-seq experimental pipeline.

Batch effects arising from reagents, sequencing runs, and environmental factors represent significant challenges in RNA-seq research that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological conclusions. Through systematic detection employing both visualization techniques and quantitative metrics, researchers can identify these technical artifacts and implement appropriate correction strategies. The integration of careful experimental design with computational correction approaches provides a comprehensive framework for managing batch effects throughout the RNA-seq workflow. As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve, particularly with the growing adoption of single-cell and multi-omics approaches, vigilant attention to batch effects remains essential for ensuring biological validity and reproducibility in genomic research.

Batch effects are systematic non-biological variations that arise during sample processing and sequencing across different batches, representing a significant challenge in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses [13]. These technical artifacts can be introduced by various sources, including different handlers, experiment locations, reagent batches, library preparation protocols, and sequencing runs conducted at different time points [3]. In the context of sequencing data, two runs at different time points can already show a batch effect [3].

When batch effects confound RNA-seq data, they compromise data reliability and obscure true biological differences, potentially having detrimental impacts on downstream analyses such as differential expression (DE) testing and sample clustering [4] [13]. Batch effects can introduce differentially expressed genes between groups that are only detected between batches but have no biological meaning, leading to false discoveries and irreproducible research findings [3]. Conversely, careless correction of batch effects can result in the loss of legitimate biological signal contained in the data, highlighting the critical need for appropriate batch effect management strategies [3].

How Batch Effects Artificially Influence Differential Expression Analysis

Mechanisms of Impact

Batch effects compromise differential expression analysis by introducing systematic noise that can be confounded with biological signals of interest. The presence of batch effects can lead to both false positives and false negatives in DE analysis, as these technical variations can be on a similar scale or even larger than the biological differences under investigation [4]. This significantly reduces the statistical power to detect genuinely differentially expressed genes [4].

The problem extends beyond simple mean shifts in expression levels. Different batches may exhibit varying dispersion parameters in their count distributions, further complicating DE analysis [4]. When batches with different dispersion parameters are pooled without proper correction, the resulting DE analysis suffers from reduced sensitivity and specificity, potentially missing true biological effects while highlighting batch-specific artifacts [4].

Empirical Evidence

Studies have demonstrated that batch effects can substantially impact DE results. In one analysis comparing the performance of batch correction methods, uncorrected data showed significantly compromised power in DE detection, particularly when using false discovery rate (FDR) for statistical testing [4]. The number of falsely identified differentially expressed genes can increase dramatically in the presence of batch effects, leading to incorrect biological interpretations [3].

Simulation studies have further quantified this impact, showing that as batch effects increase in magnitude (both in terms of mean fold change and dispersion differences between batches), the true positive rates for DE detection decrease substantially without appropriate correction [4]. This effect is particularly pronounced when there are limited replicates within each batch-condition combination, a common scenario in real-world experimental designs.

How Batch Effects Induce Clustering Artifacts

Distortion of Multidimensional Patterns

Clustering analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), are highly susceptible to batch effects because these methods rely on global patterns of similarity in gene expression profiles. Batch effects can introduce systematic covariance structures that dominate the true biological signal, leading to clusters that represent technical artifacts rather than biological reality [3] [13].

In one demonstration using public RNA-seq data, PCA clearly separated samples by library preparation method (ribosomal reduction vs. polyA enrichment) rather than by the biological condition of interest (Human Brain Reference vs. Universal Human Reference) [13]. This illustrates how batch effects can create the illusion of distinct clusters where none exist biologically, or alternatively, can obscure true biological clusters by introducing technical variance that drowns out the biological signal.

Quality-Confounded Clustering

Batch effects often correlate with differences in sample quality, further complicating clustering analyses. Research has shown that sample quality metrics (Plow scores) can significantly differ between batches, and these quality differences can drive apparent clustering patterns [3]. In datasets with strong quality-based batch effects, samples may cluster by quality metrics rather than by biological group, creating artifacts that persist even after attempts at conventional normalization [3].

The relationship between quality and batch effects is particularly problematic because it represents a confounding factor that can be difficult to disentangle. In some cases, the observable batch effect is not directly related to quality, while in others, quality differences are the primary driver of batch effects [3]. This multifaceted nature of batch effects necessitates specialized approaches for detection and correction that can account for both quality-associated and quality-independent technical artifacts.

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Quality-Aware Machine Learning Detection

Protocol Overview: This methodology uses a machine-learning-based quality classifier (seqQscorer) to detect batches from differences in predicted sample quality [3].

Table 1: Workflow for Quality-Aware Batch Effect Detection

| Step | Procedure | Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Subsampling | Download max 10 million reads per FASTQ file; subset to 1,000,000 reads for feature extraction | Subset size: 1,000,000 reads | Reduced computing time without significant impact on predictability |

| 2. Feature Extraction | Derive quality features using bioinformatics tools | Use features with explanatory power over quality | Quality feature set for each sample |

| 3. Quality Prediction | Apply machine learning classifier (seqQscorer) | Grid search of multiple algorithms | Plow score (probability of low quality) for each sample |

| 4. Batch Detection | Test for significant differences in Plow between batches | Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05 threshold) | Identification of quality-associated batches |

Implementation Details: The machine learning classifier was developed using 2,642 quality-labeled FASTQ files from the ENCODE project, with a grid search of multiple algorithms including logistic regression, ensemble methods, and multilayer perceptrons [3]. The resulting classifier uses quality features as input to provide a robust prediction of quality in FASTQ files, which can then be leveraged to detect quality-associated batch effects [3].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Detection Protocol

Protocol Overview: PCA serves as a powerful visual and analytical tool for identifying batch effects by revealing whether sample grouping is driven by technical rather than biological factors [13].

Table 2: PCA-Based Batch Effect Detection Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Parameters | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preparation | Load uncorrected count data; simplify sample names | Protein-coding genes only | Reduced complexity for clearer signal |

| 2. Condition Annotation | Define biological conditions and batch groups | UHR/HBR for conditions; Ribo/Poly for batches | Framework for color-coding in visualization |

| 3. PCA Computation | Perform principal component analysis | Use prcomp() function in R | Principal components capturing variance |

| 4. Variance Calculation | Determine percentage variance explained | (sdev^2 / sum(sdev^2)) * 100 | Identify most informative PCs |

| 5. Visualization | Plot PC1 vs. PC2 with batch/condition coloring | Color by condition and library method | Visual identification of batch-driven clustering |

Implementation Details: The PCA approach requires a balanced experimental design where each biological condition is represented in each batch. Without this balance, it becomes impossible to distinguish batch effects from biological signals [13]. The method is particularly effective when batch effects are strong enough to create visible separation between batches in the reduced-dimensionality space of the first two principal components [13].

Correction Approaches and Their Impact on Downstream Analyses

ComBat-ref Correction Method

Protocol Overview: ComBat-ref is a refined batch effect correction method that builds on ComBat-seq but innovates by selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion and preserving its count data while adjusting other batches toward this reference [4] [8].

Theoretical Foundation: ComBat-ref models RNA-seq count data using a negative binomial distribution, with each batch potentially having different dispersions. For a gene g in batch j and sample i, the count n~ijg~ is modeled as:

n~ijg~ ~ NB(μ~ijg~, λ~ig~)

where μ~ijg~ is the expected expression level and λ~ig~ is the dispersion parameter for batch i [4].

The expected gene expression level is modeled using a generalized linear model:

log(μ~ijg~) = α~g~ + γ~ig~ + β~c~j~g~ + log(N~j~)

where α~g~ represents the global background expression of gene g, γ~ig~ represents the effect of batch i, β~c~j~g~ denotes the effects of the biological condition c~j~, and N~j~ is the library size of sample j [4].

Algorithm Implementation: The key innovation of ComBat-ref lies in its reference batch selection and adjustment procedure:

- Estimate batch-specific dispersion parameters λ~i~ for each batch

- Select the batch with the smallest dispersion as the reference batch (e.g., batch 1)

For non-reference batches (i ≠ 1), compute the adjusted gene expression level:

log(μ~∼~ijg~) = log(μ~ijg~) + γ~1g~ - γ~ig~

Set the adjusted dispersion to λ~∼~i~ = λ~1~

- Calculate adjusted counts n~∼~ijg~ by matching cumulative distribution functions while ensuring zero counts remain zeros and preventing infinite adjusted counts [4]

Quality-Based Correction with Outlier Removal

Protocol Overview: This approach leverages automated quality assessment to correct batch effects by incorporating quality scores directly into the correction framework, optionally coupled with strategic outlier removal [3].

Implementation Details: The method uses machine-learning-derived probability scores (Plow) for each sample to be of low quality. These scores are then incorporated into the batch correction process, either as standalone correction factors or in combination with known batch information [3].

The approach involves:

- Computing quality-aware correction factors based on Plow scores

- Optionally identifying and removing outlier samples that disproportionately influence batch effects

- Applying correction to expression data using quality-based adjustments

- Validating correction effectiveness through clustering metrics and differential expression analysis [3]

Performance Evidence: Empirical evaluation across 12 publicly available RNA-seq datasets demonstrated that Plow-based correction was comparable to or better than reference methods using a priori knowledge of batches in 10 of 12 datasets (92%) [3]. When coupled with outlier removal, the correction was more frequently evaluated as better than the reference (comparable or better in 5 and 6 datasets of 12, respectively; total = 92%) [3].

Performance Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

Table 3: Batch Effect Correction Performance Comparison

| Method | Statistical Foundation | Key Innovation | DE Analysis Performance | Clustering Improvement | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-ref [4] | Negative binomial model | Reference batch with smallest dispersion | Superior TPR, controlled FPR with FDR | Significant improvement in clustering metrics | Slightly elevated FPR in some scenarios |

| ComBat-seq [4] | Negative binomial model | Preserves integer count data | Good TPR, higher FPR than ComBat-ref | Moderate clustering improvement | Reduced power with dispersed batches |

| Quality-Aware ML [3] | Machine learning quality prediction | Uses quality scores for correction | Comparable to reference methods | Better than reference when combined with outlier removal | Dependent on quality-batch correlation |

| NPMatch [4] | Nearest-neighbor matching | Non-parametric adjustment | Good TPR but consistently high FPR (>20%) | Limited documentation | Unacceptably high false positive rates |

TPR = True Positive Rate; FPR = False Positive Rate; FDR = False Discovery Rate

Impact on Differential Expression Analysis

Rigorous simulation studies have demonstrated that ComBat-ref maintains exceptionally high statistical power comparable to data without batch effects, even when there is significant variance in batch dispersions [4]. In challenging scenarios with high dispersion fold changes (dispFC = 4) and mean fold changes (meanFC = 2.4) between batches, ComBat-ref maintained true positive rates similar to those observed in cases without batch effects, outperforming all other methods [4].

The performance advantage is particularly evident when using false discovery rate (FDR) for statistical testing, as recommended by edgeR and DESeq2 [4]. ComBat-ref outperforms other methods in this context, making it particularly suitable for modern RNA-seq analysis pipelines where FDR control is standard practice.

Impact on Clustering Artifacts

Batch effect correction methods show variable effectiveness in mitigating clustering artifacts. Quality-aware methods have demonstrated an ability to deconvolute PCA plots where strong outliers skew the distribution, scattering points as expected biologically rather than technically [3]. In some cases, correction based on quality scores improved clustering when traditional batch correction did not, while in other scenarios, the opposite pattern was observed, highlighting the context-dependent nature of batch effect correction [3].

The combination of traditional batch correction with quality-aware approaches sometimes yields further improvements, particularly when there is low imbalance of quality between sample groups (low designBias) [3]. This suggests that a tailored approach to batch correction, potentially incorporating multiple correction strategies, may be necessary for optimal clustering results across diverse datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Batch Effect Management

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-ref [4] | Batch effect correction | RNA-seq count data | Reference batch selection; negative binomial model; preserved count data |

| seqQscorer [3] | Quality assessment | FASTQ file quality evaluation | Machine-learning-based; uses ENCODE-trained classifier; Plow scores |

| singleCellHaystack [15] | DEG identification without clustering | Single-cell RNA-seq data | Clustering-independent; Kullback-Leibler divergence; fast runtime |

| ArtifactsFinder [16] | Artifact variant filtering | NGS library preparation artifacts | Identifies inverted repeat and palindromic sequence artifacts |

| ClusterDE [17] | Post-clustering DE validation | Single-cell RNA-seq | Controls FDR regardless of clustering quality; synthetic null data |

| sva Package [3] [13] | Surrogate variable analysis | Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq | Detects and corrects multiple sources of unwanted variation |

Best Practices and Implementation Guidelines

Experimental Design Considerations

Proper experimental design represents the most effective strategy for managing batch effects. Whenever possible, biological conditions of interest should be balanced across batches, ensuring that each batch contains representatives of each condition [13]. This design enables statistical methods to distinguish biological signals from technical artifacts more effectively.

For projects involving multiple sequencing runs, library preparations, or processing dates, intentional blocking and randomization should be employed. Specifically, samples from each biological group should be distributed across processing batches, and processing order should be randomized to avoid confounding technical trends with biological factors [3] [13].

Method Selection Framework

Selecting an appropriate batch effect management strategy depends on multiple factors:

For known batches with balanced design: ComBat-ref demonstrates superior performance for differential expression analysis, particularly when dispersion differences exist between batches [4]

For unknown batches or quality-driven effects: Quality-aware machine learning approaches can detect and correct batches without prior knowledge of batch labels [3]

For single-cell RNA-seq data: Clustering-independent DEG detection methods like singleCellHaystack avoid double-dipping issues associated with cluster-based DE analysis [15]

For validating clustering results: Post-clustering DE methods like ClusterDE help control false discovery rates regardless of clustering quality [17]

Validation and Quality Control

After applying batch correction methods, rigorous validation is essential. PCA visualization should be repeated to confirm that batch-driven clustering has been reduced while biologically relevant patterns persist [13]. Differential expression analysis should be performed using both corrected and uncorrected data to assess the impact on identified gene lists [4].

Quality metrics should be monitored throughout the analysis pipeline, with particular attention to the relationship between quality scores and residual batch effects [3]. When employing aggressive correction methods, negative control genes (those not expected to show biological variation) can be used to verify that technical artifacts have been reduced without introducing new distortions [4].

In high-throughput RNA-seq research, batch effects represent a significant challenge, introducing non-biological technical variations that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous conclusions. These systematic biases emerge from various technical sources, including different sequencing runs, reagent lots, preparation protocols, personnel, instrumentation, and temporal factors [2]. In the context of genomic studies, batch effects can manifest as expression differences correlated with processing batches rather than biological conditions, potentially obscuring true biological signals and reducing statistical power in downstream analyses [3] [13].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a powerful dimensionality reduction technique that transforms potentially linear-related variables into a set of linearly uncorrelated principal components, enabling researchers to visualize high-dimensional data in lower-dimensional spaces [18] [19]. This transformation makes PCA particularly valuable for batch effect detection, as it reveals underlying data structures and patterns that might indicate technical artifacts. When applied to RNA-seq data, PCA can effectively distinguish whether sample clustering is driven by biological conditions or technical batches, providing critical insights for quality assessment and experimental validation [20] [21].

The fundamental value of PCA in batch effect identification lies in its ability to maximize variance capture, where the first principal component (PC1) accounts for the largest possible variance in the data, followed by subsequent components that capture decreasing amounts of variance while remaining orthogonal to previous components [18]. This variance decomposition enables researchers to determine whether the dominant sources of variation in their datasets stem from biological factors of interest or from technical artifacts requiring correction before meaningful biological interpretations can be made.

Theoretical Foundations of PCA for Batch Effect Detection

Mathematical Principles of PCA

Principal Component Analysis operates on the fundamental principle of orthogonal transformation, converting a set of observations of possibly correlated variables into a set of values of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components [18] [19]. This transformation is achieved through several key mathematical operations:

- Covariance Matrix Computation: PCA begins by calculating the covariance matrix of the original data, which captures the relationships between all pairs of variables (genes in RNA-seq data).

- Eigenvalue Decomposition: The covariance matrix undergoes eigenvalue decomposition, where eigenvectors represent the principal components (directions of maximum variance), and eigenvalues indicate the magnitude of variance along each component.

- Dimensionality Reduction: By projecting the original data onto a subset of principal components, high-dimensional data can be visualized in two or three dimensions while preserving the most significant patterns.

For RNA-seq data analysis, this process enables researchers to transform thousands of gene expression measurements into a simplified representation where samples can be visualized as points in a reduced-dimensional space, with distances between points reflecting overall expression similarities and differences [18].

PCA Interpretation in the Context of Batch Effects

The interpretation of PCA results for batch effect detection relies on understanding several key concepts:

- Variance Explanation: Each principal component accounts for a percentage of the total variance in the dataset, typically displayed on PCA plot axes [13]. Batch effects often appear as strong separation along one or more principal components, with the percentage of explained variance indicating the magnitude of the effect.

- Sample Clustering Patterns: In the absence of batch effects, samples should cluster primarily by biological conditions or experimental groups. When batch effects are present, samples from the same processing batch may cluster together regardless of biological group [20] [21].

- Component Loading Analysis: The contribution of individual genes to each principal component (loadings) can reveal whether specific gene sets are driving the observed patterns, helping distinguish technical from biological effects.

The theoretical foundation of PCA ensures that the largest sources of variation in the data will be captured in the first few principal components. Since batch effects often introduce substantial systematic variation, they frequently appear as dominant patterns in initial components, making PCA particularly effective for their visual identification [21].

Practical Implementation of PCA for Batch Effect Identification

Experimental Design Considerations

Effective batch effect detection begins with proper experimental design that anticipates and minimizes technical variability. Several design strategies can reduce batch effect magnitude and facilitate their detection:

- Balanced Design: Distributing samples from all biological conditions across all processing batches ensures that batch effects can be distinguished from biological effects [20]. This approach allows statistical methods to separate technical artifacts from true biological signals.

- Batch Metadata Collection: Comprehensive documentation of all potential batch variables (sequencing date, reagent lots, personnel, instrumentation) is essential for interpreting PCA results and applying corrective measures [2].

- Quality Control Integration: Incorporating RNA quality metrics, sequencing depth statistics, and other quality measures helps distinguish batch effects from quality-related artifacts [3].

Data Preprocessing Pipeline

Proper data preprocessing is crucial for meaningful PCA results and accurate batch effect detection. The following pipeline represents essential preprocessing steps:

- Raw Data Quality Control: Assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overall read composition using tools like FastQC.

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Map reads to a reference genome and generate count matrices using standardized pipelines.

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods (e.g., TMM, RLE) to account for library size differences and other technical variations [2].

- Filtering: Remove lowly expressed genes that contribute mostly noise rather than biological signal.

- Transformation: Convert counts to log2-scale to stabilize variance across the dynamic range of expression.

These preprocessing steps help ensure that the input data for PCA reflects biological reality rather than technical artifacts, improving the sensitivity and specificity of batch effect detection.

PCA Workflow for Batch Effect Detection

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for PCA-based batch effect detection:

Step-by-Step Protocol for PCA Implementation

Data Preparation: Organize your RNA-seq data into a samples-by-genes count matrix, ensuring proper labeling of both samples and genes. The data should be properly normalized to account for library size differences [2].

PCA Computation: Use the

prcomp()function in R or equivalent implementations in other languages:Visualization Generation: Create PCA plots colored by both batch and biological condition:

Pattern Interpretation: Analyze the clustering patterns to identify potential batch effects, looking specifically for:

- Separation of samples by processing batch rather than biological condition

- High percentage of variance explained by early PCs correlated with batch variables

- Distinct clusters corresponding to different technical batches

This protocol provides a standardized approach for implementing PCA-based batch effect detection in RNA-seq studies, enabling consistent application across different datasets and experimental designs.

Interpretation Framework for PCA Results

Visual Patterns Indicating Batch Effects

Interpreting PCA plots for batch effect identification requires recognizing specific visual patterns that indicate technical artifacts:

Batch-Clustered Patterns: When samples cluster predominantly by processing batch rather than biological condition, this represents a clear indicator of batch effects [20] [21]. For example, in a study comparing tumor and normal tissues, if all samples from one dataset form a distinct cluster separate from another dataset, this suggests strong batch effects related to dataset origin.

Variance Distribution: The percentage of variance explained by the first few principal components provides quantitative evidence of batch effect magnitude. When early PCs explain unusually high proportions of variance (e.g., PC1 > 30-40%), this often indicates dominant technical effects [13].

Vector Directionality: In PCA biplots that show both samples and variable contributions, the direction of maximum variance (PC1 axis) may align with batch variables rather than biological conditions of interest.

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for interpreting PCA results:

Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

Beyond visual inspection, several quantitative metrics can enhance the objectivity of PCA-based batch effect detection:

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for PCA-Based Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Threshold Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained by Batch | Percentage of variance in early PCs correlated with batch variables | Higher values indicate stronger batch effects | >20% in PC1 suggests concerning batch effect |

| Cluster Separation Index | Distance between batch centroids in PC space | Measures degree of batch separation | >2 SD indicates significant separation |

| Within-Batch Similarity | Average pairwise correlation of samples within batches | High values indicate batch-specific patterns | >0.8 suggests batch homogeneity |

| Between-Batch Distance | Mean distance between samples from different batches | Lower values indicate successful integration | Should approximate within-batch distances after correction |

These metrics provide objective criteria for assessing batch effect severity and prioritizing datasets for correction, complementing visual pattern recognition in PCA plots.

Case Study: PCA Revealing Batch Effects in Published Data

A compelling example of PCA-based batch effect detection comes from a reanalysis of a PNAS study comparing transcriptional landscapes between human and mouse tissues [20]. The original analysis suggested that tissue-specific expression patterns were more conserved within species than across species for the same tissues—a potentially paradigm-shifting finding.

However, when researchers examined the data using PCA colored by sequencing batch, they discovered that samples clustered predominantly by sequencing instrument and flow cell channel rather than by tissue type or species [20]. This batch-clustered pattern revealed that technical factors, rather than biological reality, drove the apparent conservation of expression patterns within species.

After applying batch effect correction methods, the PCA plot showed a complete reorganization, with samples clustering primarily by tissue type regardless of species—supporting the conventional understanding of tissue-specific expression conservation across species [20]. This case demonstrates how PCA can reveal confounding batch effects that might otherwise lead to erroneous biological conclusions.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for PCA-Based Batch Effect Detection

| Tool/Package | Application Context | Key Functions | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| stats (R base) | Core PCA computation | prcomp(), princomp() functions |

R |

| ggplot2 | PCA visualization | Create publication-quality PCA plots | R |

| ggfortify | Enhanced PCA plotting | Streamlined PCA visualization with automatic labeling | R |

| sva | Batch effect correction and detection | ComBat, ComBat-seq for count data |

R/Bioconductor |

| limma | Differential expression with batch adjustment | removeBatchEffect() function |

R/Bioconductor |

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis | Built-in support for batch covariates | R/Bioconductor |

| edgeR | RNA-seq analysis | Support for batch terms in model design | R/Bioconductor |

| FactoMineR | Advanced multivariate analysis | Enhanced PCA with supplementary variables | R |

| scatterplot3d | 3D visualization | Three-dimensional PCA plots | R |

These tools collectively provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing PCA-based batch effect detection, from core computation to advanced visualization and integration with downstream statistical analyses.

Integration with Downstream Analysis and Batch Effect Correction

Connecting PCA Findings to Correction Methods

Once PCA analysis identifies significant batch effects, researchers can select appropriate correction methods based on the specific nature of the observed effects:

Strong Batch Effects with Known Batches: When PCA shows clear clustering by known batch variables, methods like ComBat [22], ComBat-seq [2], or limma's

removeBatchEffect()[2] can be applied directly using the known batch information.Subtle or Complex Batch Effects: For more nuanced patterns where batch effects interact with biological variables, surrogate variable analysis (SVA) or factor analysis methods may be more appropriate, as they can detect and adjust for unknown sources of technical variation [3].

Single-Cell RNA-seq Data: For scRNA-seq datasets, specialized methods like Harmony [22] have demonstrated superior performance in correcting batch effects while preserving biological heterogeneity, particularly when cell type composition differs between batches.

Validation of Correction Effectiveness

After applying batch correction methods, PCA should be repeated to validate effectiveness:

- Visual Assessment: Post-correction PCA plots should show reduced clustering by batch variables and enhanced clustering by biological conditions.

- Quantitative Metrics: The quantitative metrics described in Section 4.2 should show improved values, with between-batch distances decreasing and biological separation becoming more prominent.

- Biological Preservation: Correction should not eliminate legitimate biological variation; positive controls (known biological differences) should remain detectable.

This integrated approach ensures that batch effect correction successfully addresses technical artifacts without compromising the biological signals of interest, maintaining both data quality and biological validity in downstream analyses.

Principal Component Analysis represents a fundamental and powerful approach for detecting batch effects in RNA-seq research, providing both visual and quantitative insights into technical artifacts that might otherwise confound biological interpretation. By implementing the standardized protocols, interpretation frameworks, and validation approaches outlined in this guide, researchers can consistently identify batch-related patterns in their data and make informed decisions about appropriate correction strategies.

The integration of PCA-based batch effect assessment into routine RNA-seq analysis workflows strengthens research reproducibility and validity, ensuring that conclusions reflect biological reality rather than technical artifacts. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and datasets grow in complexity, PCA will remain an essential tool for quality assessment and technical artifact detection in genomic research.

In RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) research, batch effects represent systematic technical variations that are not rooted in the experimental design, potentially confounding downstream statistical analyses and leading to erroneous biological conclusions [3]. These effects can arise from various sources, including different handlers, experiment locations, reagent batches, or sequencing runs performed at different times [3]. The challenge is particularly pronounced because dedicated bioinformatics methods designed to detect these unwanted sources of variance can sometimes mistakenly identify real biological signals as batch effects, thereby removing meaningful information [23] [3].

Machine learning (ML) offers a promising solution through automated quality assessment. By leveraging statistical features derived from sequencing data, ML models can predict sample quality and use these predictions to intelligently detect and correct for batch effects [23] [3]. This quality-aware approach is grounded in the understanding that while batch effects often correlate with differences in technical quality, they are multifaceted and may also arise from other artifacts [3]. The integration of automated quality assessment in batch effect detection is particularly valuable when batch information is not explicitly known or recorded, which is often the case in public datasets [7].

Machine Learning Foundations for Quality Assessment

Feature Engineering for Sequence Quality

The foundation of any effective machine learning approach is robust feature engineering. For RNA-seq quality assessment, informative features are typically derived from raw FASTQ files using established bioinformatics tools [3] [7]. These feature sets comprehensively capture different aspects of data quality:

- RAW Features: Basic sequence quality metrics including Phred quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and nucleotide distribution patterns [7].

- MAP (Mapping) Features: Alignment statistics such as mapping rates, properly paired reads for paired-end data, and insert size distributions [7].

- LOC (Genomic Location) Features: Genomic distribution metrics including coverage uniformity and the distribution of reads across genomic features [7].

- TSS (Transcription Start Site) Features: Metrics specifically capturing enrichment around transcription start sites, which can indicate library preparation quality [7].

These features serve as input to machine learning classifiers trained on large, labeled datasets such as those from the ENCODE project, where samples have been manually classified by quality [3].

Machine Learning Algorithms and Implementation

Various machine learning algorithms have been employed for quality prediction, with random forest classifiers demonstrating particular effectiveness [3] [7]. The training process typically involves a grid search of multiple algorithms—from logistic regression to ensemble methods and multilayer perceptrons—to identify the optimal approach for robust quality prediction [3].

The output is typically a quality score, such as Plow (the probability of a sample being of low quality), which has demonstrated explanatory power for detecting batches in public RNA-seq datasets [3]. This ML-derived probability score can distinguish batches based on quality differences and serves as a basis for subsequent batch effect correction [3].

Table 1: Machine Learning Algorithms for Quality Assessment

| Algorithm Category | Specific Examples | Key Advantages | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forest | Robust to noise, handles high-dimensional data well | Used in seqQscorer's generic model [7] |

| Linear Models | Logistic Regression | Computational efficiency, interpretability | Evaluated in grid search [3] |

| Neural Networks | Multilayer Perceptrons | Captures complex non-linear relationships | Evaluated in grid search [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Workflow for Batch Effect Detection

The standard workflow for ML-based batch effect detection begins with raw FASTQ files from RNA-seq experiments. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

Subsampling: To reduce computational time, randomly subsample a maximum of 10 million reads per FASTQ file, or approximately 1 million reads for certain feature calculations, noting that random subsampling does not strongly impact the predictability of quality scores [3].

Feature Extraction: Process the (subsampled) FASTQ files using multiple bioinformatic tools to derive the four feature sets: RAW, MAP, LOC, and TSS [7]. This can be achieved through tools like:

- FastQC for basic sequence quality metrics

- RSeQC for RNA-seq specific metrics

- Alignment tools (e.g., HISAT2, STAR) to generate mapping statistics [24]

Quality Prediction: Input the extracted features into a pre-trained model (e.g., seqQscorer) to compute Plow values for each sample [3] [7].

Batch Detection: Statistically compare Plow scores across suspected batches using tests such as the Kruskal-Wallis test to identify significant quality differences between processing groups [3].

Validation: Validate detected batch effects through principal component analysis (PCA) and clustering evaluation metrics (Gamma, Dunn1, WbRatio) to confirm that sample grouping correlates with quality differences rather than biological conditions [3].

Performance Benchmarks and Validation Metrics

The performance of ML-based batch detection must be rigorously validated against known batch information. In validation studies using 12 publicly available RNA-seq datasets with available batch information, the approach demonstrated significant ability to distinguish batches based on quality scores [3].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for ML-Based Batch Detection and Correction

| Evaluation Method | Metric | Performance Outcome | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clustering Evaluation | Gamma, Dunn1, WbRatio | Improvement after correction in majority of datasets | Higher values indicate better clustering for Gamma and Dunn1; lower for WbRatio [3] |

| Differential Expression | Number of DEGs | Increased DEG detection after quality-aware correction | True biological signals preserved while batch effects removed [3] |

| Manual Evaluation | Comparative assessment | 92% success rate (comparable or better than reference method) | Against reference method using a priori batch knowledge [3] |

| Concordance Correlation | CCC | 61% of genes showed CCC > 0.8 after Procrustes correction | For cross-platform batch effect correction [25] |

Advanced Machine Learning Approaches for Batch Effect Correction

Quality Score-Based Correction Methods

Once batch effects are detected using quality scores, several correction approaches can be applied:

Quality-Based Covariate Adjustment: Include the Plow score as a covariate in statistical models for differential expression analysis, thereby accounting for quality-related variance [3].

Outlier Removal and Quality Weighting: Identify and remove extreme outliers based on quality scores before proceeding with standard batch correction methods [3].

Integrated Correction Frameworks: Apply correction methods that simultaneously account for both known batch information and quality scores, which has shown improved results in datasets with quality imbalances between sample groups [3].

In practice, when coupled with outlier removal, quality-aware correction was more often evaluated as better than reference methods that use only a priori knowledge of batches (comparable or better in 11 of 12 datasets) [3].

Deep Learning Architectures for Batch Integration

For complex batch effect scenarios, particularly in single-cell RNA-seq data, more sophisticated deep learning architectures have been developed:

Conditional Variational Autoencoders (cVAE): These are popular for batch correction due to their ability to handle non-linear batch effects and flexibility in incorporating batch covariates [26]. However, standard cVAEs may insufficiently integrate datasets with substantial technical and biological differences [26].

sysVI Framework: This advanced approach employs VampPrior and cycle-consistency constraints to improve integration across challenging scenarios like cross-species data or different protocols (e.g., single-cell vs. single-nuclei RNA-seq) [26].

Adversarial Learning: Some models incorporate adversarial components to encourage batch-invariant latent representations, though these approaches risk removing biological signals when batch effects are strong [26].

Procrustes Algorithm: A specialized ML approach designed to remove cross-platform batch effects, particularly between exome capture-based and poly-A RNA-seq protocols, enabling the projection of individual samples to larger cohorts [25].

Implementation Considerations and Research Toolkit

Practical Implementation Guide

Successful implementation of ML-based batch detection requires careful attention to several practical aspects:

Data Preprocessing Requirements:

- Ensure consistent read depth across samples, potentially through subsampling

- Generate comprehensive quality metrics using established pipelines

- Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., rlog in DESeq2) before batch assessment [7]

Model Selection and Training:

- For standard RNA-seq data, random forest models provide robust performance

- For complex integration tasks (cross-species, different protocols), consider deep learning approaches like sysVI

- When working with single samples for projection to a cohort, Procrustes offers specific functionality [25]

Validation Framework:

- Always compare multiple correction approaches using both quantitative metrics and biological plausibility

- Assess preservation of known biological signals after correction

- Examine clustering patterns with both technical and biological covariates

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| seqQscorer | ML Quality Tool | Derives Plow (probability of low quality) | Uses random forest classifier; pre-trained model available [3] |

| FastQC | Quality Control | Assesses raw sequence quality | Standard first step in QC pipeline [27] |

| RSeQC | RNA-seq QC | Provides RNA-seq specific metrics | Evaluates mapping rates, gene body coverage [24] |

| Procrustes | Batch Correction | ML algorithm for cross-platform effects | Specifically designed for EC vs. poly-A protocol differences [25] |

| sysVI | Integration Framework | cVAE-based with VampPrior + cycle consistency | For substantial batch effects (e.g., cross-species) [26] |

| ENCODE Database | Training Data | Source of quality-labeled samples | 2642 labeled samples used to train seqQscorer [3] |

| ArrayExpressHTS | Analysis Pipeline | Automated processing and QC | R/Bioconductor-based; generates ExpressionSet objects [28] |

Machine learning approaches for automated quality assessment represent a powerful paradigm for batch effect detection in RNA-seq research. By leveraging quality scores derived from intrinsic data features, these methods can identify and correct for technical artifacts while preserving biological signals. The integration of quality-aware correction with traditional batch effect removal methods has demonstrated superior performance in multiple benchmarking studies, achieving successful correction in 92% of evaluated datasets [3].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: improved deep learning architectures that better distinguish technical artifacts from biological variation; extension to emerging sequencing technologies and multi-omics integration; and enhanced methods for single-sample analysis to facilitate clinical applications. As RNA-seq continues to evolve as a critical tool in both basic research and clinical contexts, robust ML-based batch detection and correction will remain essential for generating reliable, reproducible biological insights.

Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced during experimental processes that are unrelated to the biological factors of interest. In RNA-seq data, these non-biological variations can compromise data reliability, obscure true biological differences, and lead to misleading conclusions if not properly addressed [10]. This guide provides a technical framework for understanding, detecting, and correcting for these confounding influences in genomic research.

Batch effects represent a significant challenge in high-throughput genomic studies, particularly in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). These technical variations arise from differences in experimental conditions such as reagent lots, instrumentation, personnel, processing time, or sequencing centers [10]. When batch effects correlate with biological outcomes, they can artificially create false positives in differential expression analysis or mask genuine biological signals, ultimately compromising scientific validity and reproducibility [10].

The fundamental issue stems from the basic assumption in quantitative omics profiling that instrument readout intensity (I) has a fixed, linear relationship with analyte concentration (C). In practice, fluctuations in this relationship across different experimental conditions create inherent inconsistencies in the data, leading to batch effects that can be on a similar scale or even larger than the biological differences of interest [10] [4]. This systematic noise reduces statistical power and can substantially impact downstream analyses, including differential expression testing and predictive modeling [10].

Batch effects can originate at virtually every stage of a high-throughput study, from initial study design to final data processing. The table below categorizes major sources of batch effects across the research workflow.

Table: Major Sources of Batch Effects in Omics Studies

| Source Category | Specific Examples | Affected Omics Types |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Flawed or confounded design; Minor treatment effect size | Common across omics types [10] |

| Sample Preparation | Differences in centrifugation; Varying storage conditions | Common across omics types [10] |

| Experimental Processing | Different sequencing centers; Reagent batch variations; Handling personnel | Transcriptomics, Genomics [10] [29] |

| Instrumentation | Scanner types; Resolution settings; Platform differences | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Histopathology [10] [30] |

In large, multi-institutional projects like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), samples processed in different locations and at different times become vulnerable to systematic noise, including both batch effects (unwanted variation between batches) and trend effects (unwanted variation over time) [29]. Similar challenges affect histopathology image analysis, where inconsistencies in staining protocols, scanner types, and tissue preparation introduce technical variations that can mask biological differences [30].

Profound Consequences of Uncorrected Batch Effects