Interpreting PCA Plots in Transcriptomics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots in transcriptomics studies.

Interpreting PCA Plots in Transcriptomics: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots in transcriptomics studies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational concepts with practical applications—from exploratory data analysis and quality control to troubleshooting common pitfalls and validating findings through integrative approaches. By synthesizing best practices and current methodologies, this guide empowers researchers to extract meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional transcriptomic data and make informed decisions in experimental design and analysis.

Understanding PCA Fundamentals: From Variance to Biological Insight

What PCA Reveals About Your Transcriptomic Dataset Structure

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental exploratory tool in transcriptomics research, transforming high-dimensional gene expression data into a lower-dimensional space that reveals underlying biological structure. This technical guide examines how PCA uncovers sample clustering, batch effects, and biological variability within transcriptomic datasets. We detail standardized protocols for implementing PCA in RNA-seq analysis, address critical methodological considerations including normalization strategies and dimensionality interpretation, and explore advanced applications integrating machine learning. For drug development professionals and research scientists, proper interpretation of PCA plots provides essential quality control and biological insights that guide subsequent analytical decisions in transcriptomic studies.

Transcriptomic technologies, including microarrays and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), generate high-dimensional data where thousands of genes represent variables across typically far fewer samples [1]. This dimensionality presents significant challenges for visualization and interpretation. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) addresses this by performing a linear transformation that converts correlated gene expression variables into a set of uncorrelated principal components (PCs) that successively capture maximum variance in the data [2]. The resulting low-dimensional projections enable researchers to identify patterns, clusters, and outliers within their datasets based on transcriptome-wide similarities.

In practical terms, PCA reveals the dominant directions of variation in gene expression data, allowing scientists to determine whether samples cluster by biological group (e.g., disease state, tissue type, treatment condition) or by technical artifacts (e.g., batch effects, RNA quality) [3] [4]. The unsupervised nature of PCA makes it particularly valuable for quality assessment before proceeding to supervised analyses like differential expression testing. When properly executed and interpreted, PCA provides critical insights into dataset structure that guide analytical strategy throughout the transcriptomics research pipeline.

Theoretical Foundations of PCA

Mathematical Principles

PCA operates through an eigen decomposition of the covariance matrix or through singular value decomposition (SVD) of the column-centered data matrix [2]. Given a data matrix X with n samples (rows) and p genes (columns), where the columns have been centered to mean zero, the covariance matrix S is computed as S = (1/(n-1))X'X. The principal components are derived by solving the eigenvalue problem:

Sa = λa

where λ represents the eigenvalues and a represents the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix S [2]. The eigenvectors, termed PC loadings, indicate the weight of each gene in the component, while the eigenvalues quantify the variance captured by each component. The projections of the original data onto the new axes, called PC scores, position each sample in the reduced dimensional space and are computed as Xa [2].

Geometric Interpretation

Geometrically, PCA performs a rotation of the coordinate system to align with the directions of maximal variance [5]. The first principal component (PC1) defines the axis along which the projection of the data points has maximum variance. The second component (PC2) is orthogonal to PC1 and captures the next greatest variance, with subsequent components following this pattern while maintaining orthogonality [5]. This geometric transformation allows researchers to view the highest-variance aspects of their high-dimensional transcriptomic data in just two or three dimensions while preserving the greatest possible amount of information about sample relationships.

Practical Implementation for Transcriptomic Data

Standardized PCA Workflow

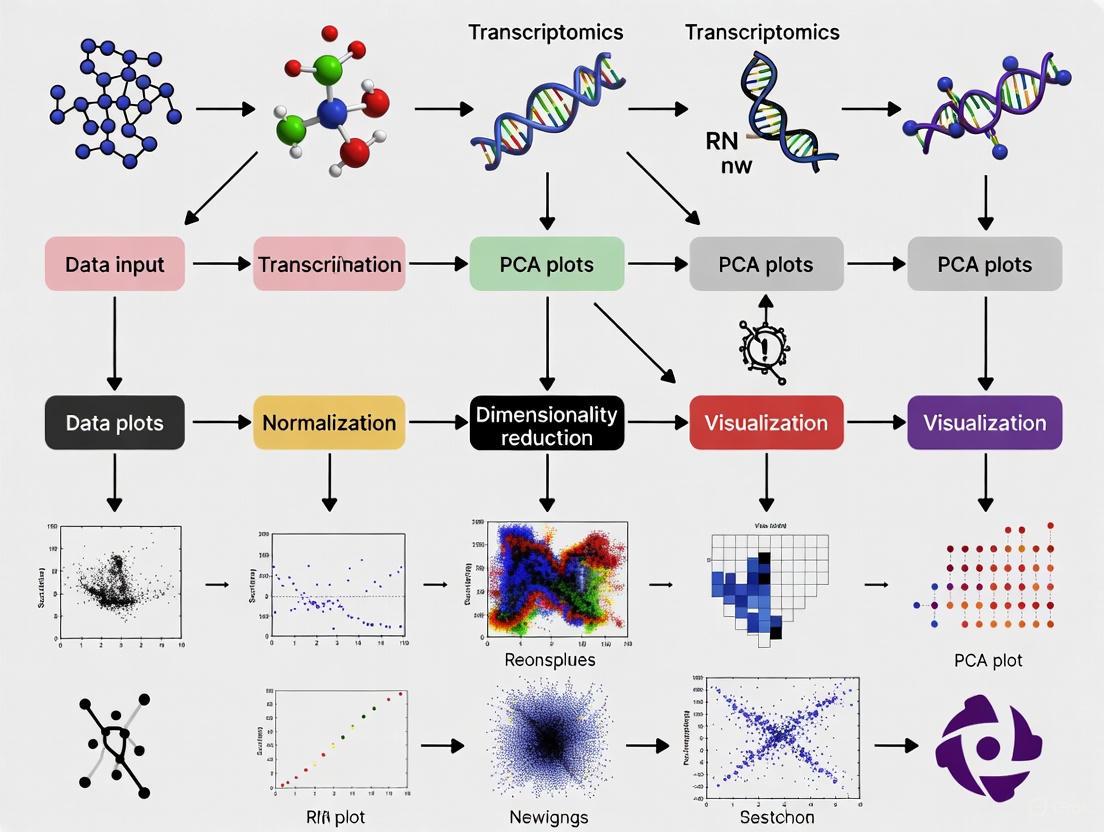

Figure 1: PCA workflow for transcriptomic data analysis showing key steps from raw data to interpretation.

Data Preprocessing Protocols

Normalization Methods

Normalization is a critical preprocessing step that ensures technical variability does not dominate biological signal in PCA. Different normalization methods can significantly impact PCA results and interpretation [6]. For RNA-seq count data, effective normalization must account for library size differences and variance-mean relationships. A comprehensive evaluation of 12 normalization methods found that the choice of normalization significantly influences biological interpretation of PCA models, with certain methods better preserving biological variance while others more effectively remove technical artifacts [6].

Data Filtering and Transformation

Prior to PCA, genes with low counts across samples should be filtered to reduce noise. A common approach is to retain only genes with counts per million (CPM) > 1 in at least the number of samples corresponding to the size of the smallest group. Following normalization and filtering, variance-stabilizing transformations such as log2(X+1) are typically applied to count data to prevent a few highly variable genes from dominating the PCA results [3].

Computational Execution

In R, PCA can be performed using the prcomp() function, which accepts a transposed normalized count matrix with samples as rows and genes as columns [3]. The function centers the data by default, and the scale parameter can be set to TRUE to standardize variables, which is particularly recommended when genes exhibit substantially different variances [3]. The computational output includes the PC scores (sample_pca$x), eigenvalues (sample_pca$sdev^2), and variable loadings (sample_pca$rotation) that can be extracted for further analysis and visualization [3].

Interpreting PCA Results in Transcriptomics

Variance Explained and Component Significance

Table 1: Typical variance distribution across principal components in transcriptomic data

| Principal Component | Percentage of Variance Explained | Cumulative Variance | Typical Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 15-40% | 15-40% | Major biological signal (e.g., tissue type) |

| PC2 | 10-25% | 25-65% | Secondary biological signal or major batch effect |

| PC3 | 5-15% | 30-80% | Additional biological signal or technical factor |

| PC4+ | <5% each | 80-100% | Minor biological signals, noise, or stochastic effects |

The variance explained by each principal component is calculated from the eigenvalues (λ) as λi/Σλ × 100% [3]. A scree plot visualizes the eigenvalues in descending order and helps determine the number of meaningful components; a sharp decline ("elbow") typically indicates transition from biologically relevant components to noise [3] [7]. In large heterogeneous transcriptomic datasets, the first 3-6 components often capture the majority of structured biological variation, though the specific number depends on dataset complexity and effect sizes [4].

Interpreting Sample Patterns in Score Plots

PC score plots reveal sample relationships and cluster patterns. Samples with similar expression profiles cluster together in the projection, while outliers appear separated from main clusters. When biological groups form distinct clusters in PC space, this indicates that inter-group differences exceed intra-group variability. Strong batch effects often manifest as clustering by processing date, sequencing lane, or other technical factors, potentially obscuring biological signals [4]. Color-coding points by experimental factors (treatment, tissue type) and technical covariates (batch, RNA quality metrics) facilitates identification of variance sources.

Extracting Biological Meaning from Loadings

Gene loadings indicate each gene's contribution to components. Genes with large absolute loadings (positive or negative) for a specific PC strongly influence that component's direction. Loading analysis can reveal biological processes driving sample separation; for example, if PC1 separates tumor from normal samples, genes with high PC1 loadings likely include differentially expressed genes relevant to cancer pathology [3]. Functional enrichment analysis of high-loading genes provides biological interpretation of components, connecting mathematical transformations to biological mechanisms.

Key Insights from PCA in Transcriptomic Studies

Intrinsic Dimensionality of Gene Expression Data

The intrinsic dimensionality of transcriptomic data—the number of components needed to capture biologically relevant information—has been debated. Early studies of large heterogeneous microarray datasets suggested surprisingly low dimensionality, with the first 3-4 principal components capturing major biological axes like hematopoietic lineage, neural tissue, and proliferation status [4]. However, subsequent work revealed that higher components frequently contain additional biological signal, particularly for comparisons within similar tissue types [4]. The apparent dimensionality depends heavily on dataset composition; larger sample sizes representing more biological conditions increase the number of meaningful components.

Sample Composition Effects

PCA results are strongly influenced by sample composition within the dataset. Studies have demonstrated that sample size disparities across biological groups can skew principal components toward representing the largest groups [4]. In one computational experiment, reducing the proportion of liver samples from 3.9% to 1.2% eliminated the liver-specific component, while increasing liver sample representation strengthened this signal [4]. This underscores that PCA reveals dominant variance sources in the specific dataset analyzed, which may reflect technical artifacts, sampling bias, or true biological signals.

Information Distribution Across Components

While early components capture the largest variance sources, biologically relevant information distributes across multiple components. Analysis of residual information after removing the first three components shows that tissue-specific correlation patterns persist [4]. The information ratio criterion quantifies phenotype-specific information distribution between projected and residual spaces, revealing that comparisons within large groups (e.g., different brain regions) retain substantial information in higher components [4]. This explains why focusing exclusively on the first 2-3 components may miss biologically important signals, particularly for subtle phenotypic differences.

Advanced Applications and Integration

Integration with Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning enhances PCA applications in transcriptomics through several advanced frameworks. Gene Network Analysis methods like Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) group genes into modules based on expression pattern similarity, with PCA sometimes applied to reduce dimensionality before network construction [8]. Biomarker discovery pipelines combine PCA for dimensionality reduction with machine learning classifiers (e.g., LASSO, support vector machines) to identify compact gene signatures predictive of disease states or treatment responses [8]. These approaches leverage PCA's ability to distill thousands of genes into manageable components while preserving essential biological information.

Drug Connectivity Mapping

The Drug Connectivity Map (cMap) resource applies PCA-like dimensionality reduction to gene expression profiles from drug-treated cells, creating signature vectors that enable comparison across compounds [8]. Researchers can project their own transcriptomic data into this space to identify drugs that reverse disease signatures—for example, finding compounds that shift expression toward normal patterns. Similar approaches using the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) databases help connect transcriptomic profiles to therapeutic sensitivity [8].

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), PCA represents a standard step in preprocessing before nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques (t-SNE, UMAP) that visualize cell clusters [8]. PCA denoises expression data and reduces computational requirements for subsequent analyses. For spatial transcriptomics, PCA helps identify spatial expression patterns by reducing dimensionality while maintaining spatial relationships, revealing gradients and regional specifications in tissue contexts.

Experimental Considerations and Best Practices

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools for PCA in transcriptomics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| prcomp() (R function) | PCA computation | Standard PCA implementation from centered/transformed count matrices |

| DESeq2 (R package) | Data normalization and transformation | Variance-stabilizing transformation of count data prior to PCA |

| edgeR (R package) | Data normalization and filtering | TMM normalization and low-expression gene filtering |

| SCONE (R package) | Normalization assessment | Evaluation of multiple normalization methods for optimal PCA performance |

| Omics Playground (platform) | Interactive analysis | GUI-based PCA with integration of multiple normalization approaches |

| Drug cMap Database | Reference data | Comparison of study data with drug perturbation signatures |

Methodological Limitations and Alternatives

PCA has several limitations that researchers should consider. As a linear method, PCA may fail to capture complex nonlinear relationships in gene expression data [7]. When biological effects are small relative to technical noise, PCA may not reveal relevant clustering without prior supervised adjustment [4]. Additionally, PCA assumes that high-variance directions correspond to biological signals, which may not hold if technical artifacts introduce substantial variance [6].

Several methodological adaptations address these limitations. Kernel PCA extends the approach to capture nonlinear structures [7]. Robust PCA methods reduce sensitivity to outliers [2]. For datasets with known batch effects, * supervised normalization* or batch correction methods should be applied before PCA to prevent technical variance from dominating components [6]. When PCA fails to reveal expected biological structure despite evidence from other analyses, nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques may better capture the underlying data geometry.

Validation and Reproducibility

To ensure PCA results reflect biological truth rather than dataset-specific artifacts, several validation approaches are recommended. Subsampling validation assesses stability of principal components across dataset variations. Independent replication confirms that similar components emerge in comparable datasets. Biological validation through experimental follow-up of loading-based hypotheses provides the strongest evidence for correct interpretation. For method selection, objective criteria such as the ability to recover known biological groups should guide choice of normalization and preprocessing strategies [6].

PCA remains an indispensable tool for initial exploration of transcriptomic data, providing critical insights into data quality, batch effects, and biological group separation. When properly implemented with appropriate normalization and preprocessing, PCA reveals the intrinsic structure of gene expression data and guides subsequent analytical steps. As transcriptomic technologies evolve toward single-cell resolution and spatial profiling, PCA and its extensions continue to provide a mathematical foundation for reducing dimensionality while preserving biological information. For drug development and clinical translation, careful interpretation of PCA plots ensures that analytical decisions are grounded in a comprehensive understanding of dataset structure and variance components.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) stands as a cornerstone statistical technique in transcriptomics research, enabling researchers to reduce the overwhelming dimensionality of gene expression data and extract meaningful biological patterns. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of PCA plot interpretation, focusing on the core elements of scores, variance explained, and component meaning. Within the context of a broader thesis on multivariate data exploration in omics sciences, we detail how PCA reveals sample clustering, identifies outliers, and captures major sources of variation in high-throughput transcriptomics datasets. By synthesizing current methodologies and visualization approaches, this whitepaper equips researchers and drug development professionals with the analytical framework necessary to transform complex gene expression matrices into actionable biological insights.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is an unsupervised multivariate statistical technique that applies orthogonal transformations to convert a set of potentially intercorrelated variables into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs) [9]. In transcriptomics research, where expression data for thousands of genes can be overwhelming to explore, PCA serves as a vital tool for emphasizing variation and bringing out strong patterns in datasets [3] [10]. The technique distills the essence of complex datasets while maintaining fidelity to the original information, enabling the construction of robust mathematical frameworks that encapsulate characteristic profiles of biological samples [9].

PCA operates as a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms the original set of variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components [11]. This process involves calculating the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance or correlation matrix of the data, where the eigenvectors represent the directions of maximum variance in the data, and the corresponding eigenvalues represent the amount of variance explained by each eigenvector [11]. For transcriptome-wide studies, PCA provides a powerful approach to understand patterns of similarity between samples based on gene expression profiles, making high-dimensional data more amenable to visual exploration through projections onto the first few principal components [3].

Theoretical Foundations of PCA

Mathematical Underpinnings

The mathematical foundation of PCA involves solving an eigenvalue/eigenvector problem. Given a data matrix X with n samples (rows) and p variables (columns, e.g., genes), where the columns are centered to have zero mean, the principal components are derived from the covariance matrix S = (1/(n-1))X′X [2]. The PCA solution involves finding the eigenvectors a and eigenvalues λ that satisfy the equation:

Sa = λa

The eigenvectors, termed PC loadings, represent the axes of maximum variance, while the eigenvalues quantify the amount of variance captured by each corresponding principal component [2]. The full set of eigenvectors of S form an orthonormal set of vectors, and the new variables (PC scores) are obtained as linear combinations Xa of the original data [2]. PCA can also be understood through singular value decomposition (SVD) of the column-centered data matrix X*, providing both algebraic and geometric interpretations of the technique [2].

Key Components of PCA

- PC Loadings: The eigenvectors a_k, which represent the weight or contribution of each original variable to the principal component. These are sometimes called the "axis" or "direction" of maximum variance [3] [2].

- PC Scores: The values of the new variables for each observation, obtained by projecting the original data onto the principal components (Xa_k) [3] [2].

- Eigenvalues: Represent the variance explained by each principal component. The sum of all eigenvalues equals the total variance in the original dataset [3].

- Variance Explained: The proportion of total variance captured by each PC, calculated as λ_k/Σλ for each component k [3].

Table 1: Key Elements of a PCA Output

| Element | Description | Interpretation in Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| PC Loadings | Eigenvectors of covariance matrix | Weight of each gene's contribution to a PC |

| PC Scores | Projection of samples onto PCs | Coordinates of samples in PC space |

| Eigenvalues | Variance captured by each PC | Importance of each PC in describing data structure |

| Variance Explained | Percentage of total variance per PC | How much of the total gene expression variability a PC captures |

| Biplot | Combined plot of scores and loadings | Shows both samples and genes in PC space |

Interpreting PCA Results

Variance Explained and Scree Plots

The variance explained by each principal component is fundamental to interpreting PCA results. The first principal component (PC1) captures the most pronounced feature in the data, with subsequent components (PC2, PC3, etc.) representing increasingly subtler aspects [9]. A scree plot displays how much variation each principal component captures from the data, with the y-axis representing eigenvalues (amount of variation) and the x-axis showing the principal components in order [3] [12].

In an ideal scenario, the first two or three PCs capture most of the information, allowing researchers to ignore the rest without losing important information [12]. The scree plot should show a steep curve that bends at an "elbow" point before flattening out, with this elbow representing the optimal number of components to retain [12]. For datasets where the scree plot doesn't show a clear elbow, two common approaches are:

- Kaiser rule: Retain PCs with eigenvalues of at least 1 [12]

- Proportion of variance: Selected PCs should collectively describe at least 80% of the total variance [12]

Table 2: Methods for Determining Significant PCs in Transcriptomics

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scree Plot | Visual identification of "elbow" point | Intuitive, easy to implement | Subjective interpretation |

| Kaiser Rule | Keep PCs with eigenvalues ≥1 | Objective threshold | May retain too many or too few components |

| Variance Explained | Retain PCs that cumulatively explain >80% variance | Ensures sufficient information retention | Threshold is arbitrary; may miss biologically relevant subtle patterns |

| Parallel Analysis | Compare to PCA of random datasets | Statistical robustness | Computationally intensive |

Score Plots and Sample Patterns

The PCA score plot visualizes samples in the reduced dimension space of the principal components, typically showing PC1 versus PC2 [3] [9]. Each point in the score plot corresponds to an individual sample, with different colors representing distinct groups or experimental conditions [9]. Interpretation of score plots focuses on several key patterns:

- Clustering: Well-clustered biological replicates indicate good technical repeatability. Samples that cluster together have similar gene expression profiles across the most variable genes [9].

- Separation between groups: Distinct groupings along PC1 or PC2 may reflect treatment effects, genetic differences, or time points in an experiment [9].

- Outliers: Samples that deviate from their expected clusters may indicate poor sample quality, experimental artifacts, or biologically interesting anomalies [9].

- Gradients: Continuous distributions of samples along a PC may represent gradual changes in gene expression due to processes like development, time courses, or dose responses.

In transcriptomics, the first few PCs often capture major biological effects, with PC1 frequently separating samples based on the strongest source of variation, such as tissue type or major treatment effect, while subsequent PCs may capture more subtle biological signals or technical artifacts [13].

Loading Interpretation and Biplots

PC loadings indicate how strongly each original variable (gene) influences a principal component. The further away a loading vector is from the origin, the more influence that variable has on the PC [12]. Biplots combine both score and loading information in a single visualization, enabling researchers to see both samples and variables simultaneously [14] [12].

In a biplot:

- The bottom and left axes represent PC scores for the samples

- The top and right axes represent loadings for the variables [12]

- The angles between loading vectors indicate correlations between variables:

For transcriptomic data, loading interpretation helps identify genes that drive the separation observed in the score plot, connecting patterns in sample clustering to specific gene expression changes.

Practical Implementation for Transcriptomics

Data Preprocessing and PCA Computation

For RNA-seq data analysis, proper preprocessing is essential for meaningful PCA results. The standard approach involves:

- Data normalization: Account for sequencing depth and other technical biases

- Transformation: Often log-transformation of normalized counts to stabilize variance

- Centering and scaling: Variables (genes) are typically centered (mean-zero) and may be scaled to unit variance, especially when genes are measured on different scales [3]

In R, PCA can be computed using the prcomp() function:

The prcomp() function returns an object containing:

sdev: Standard deviations of principal componentsrotation: The matrix of variable loadingsx: The rotated data (scores) [3]

Visualization Workflow

The PCA visualization workflow in transcriptomics typically involves:

The Researcher's Toolkit for PCA in Transcriptomics

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for PCA in Transcriptomics Research

| Tool/Function | Application | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| prcomp() | PCA computation in R | Uses singular value decomposition, preferred for numerical accuracy [3] | Base R function |

| varianceExplained | Calculate PC contribution | Computes percentage and cumulative variance from PCA object [3] | pc_eigenvalues <- sample_pca$sdev^2 |

| Scree Plot | Determine significant PCs | Visualize variance explained by each component [3] [12] | qplot(x = PC, y = pct, data = pc_eigenvalues_df) |

| Score Plot | Visualize sample relationships | Scatterplot of PC1 vs PC2 with sample labels/colors [3] | ggplot(pc_scores_df, aes(PC1, PC2, color = group)) + geom_point() |

| Biplot | Combined scores and loadings | Overlay variable influence on sample projection plot [14] [12] | biplot(sample_pca, choices = c(1, 2)) |

| bigsnpr | Large-scale genetic PCA | Efficient PCA for very large datasets [13] | R package from CRAN |

Advanced Considerations in Transcriptomics

Pitfalls and Limitations

While PCA is powerful, researchers must recognize its limitations:

- Linear assumptions: PCA assumes linear relationships between variables, while biological systems often exhibit nonlinear behaviors [11]

- No group awareness: As an unsupervised method, PCA doesn't use known group labels and may fail to differentiate predefined groups clearly [9]

- Interpretability challenges: Beyond the first few PCs, biological meaning becomes harder to extract [9]

- Horseshoe effect: An artifact where gradient data folds in on itself, potentially distorting ecological patterns [11]

- Sensitivity to preprocessing: Results can be heavily influenced by normalization, transformation, and scaling decisions

In genetics specifically, some PCs may capture linkage disequilibrium structure rather than population structure, requiring careful interpretation and potentially specialized LD pruning methods [13].

Comparison to Alternative Methods

For transcriptomics data, researchers should consider when PCA is the most appropriate tool versus alternative dimensionality reduction methods:

Table 4: PCA vs Alternative Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Transcriptomics

| Method | Type | Preserves | Best For | Transcriptomics Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Global structure [15] | Exploratory analysis, outlier detection [16] | Bulk RNA-seq QC, population structure [3] [16] |

| t-SNE | Non-linear | Local structure [15] | Cluster visualization [15] [16] | scRNA-seq cell type identification [15] [16] |

| UMAP | Non-linear | Local + some global [15] | Large datasets, clustering [15] | scRNA-seq, visualization of complex manifolds [15] |

For single-cell RNA-seq data, t-SNE and UMAP are often preferred over PCA because they better capture the complex manifold structures and distinct cell populations characteristic of single-cell datasets [16]. However, PCA is frequently used as an initial step before t-SNE or UMAP to reduce computational complexity [16].

Principal Component Analysis remains an essential exploratory tool in transcriptomics research, providing a robust framework for visualizing high-dimensional gene expression data. Through careful interpretation of variance explained, sample scores, and variable loadings, researchers can identify major patterns of biological variation, assess data quality, generate hypotheses, and guide subsequent analyses. While acknowledging its limitations and understanding when alternative methods might be more appropriate, mastering PCA plot interpretation provides drug development professionals and researchers with a fundamental skill for extracting meaningful insights from complex transcriptomics datasets. As omics technologies continue to evolve, the principles of PCA interpretation will remain relevant for transforming high-dimensional data into biological understanding.

The Critical Role of Variance Explained by PC1 and PC2

In high-dimensional biological data analysis, particularly in transcriptomics, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental dimensionality reduction technique. The variance explained by the first and second principal components (PC1 and PC2) provides critical insights into dataset structure, data quality, and underlying biological signals. This whitepaper explores the mathematical foundations, interpretation methodologies, and practical applications of PC1 and PC2 variance in transcriptomics research, emphasizing how these metrics guide experimental conclusions and analytical decisions in drug development pipelines. We demonstrate that proper interpretation of these components enables researchers to identify batch effects, detect outliers, uncover biological subtypes, and streamline subsequent analyses—all essential capabilities for advancing therapeutic discovery.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a linear dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional data into a new coordinate system defined by orthogonal principal components (PCs), where the first component (PC1) captures the maximum variance in the data, and each subsequent component captures the remaining variance under the constraint of orthogonality [17] [5]. In transcriptomics studies, where datasets often contain expression measurements for thousands of genes across multiple samples, PCA provides an indispensable tool for data exploration, quality control, and hypothesis generation.

The principal components are derived from the eigenvectors of the data's covariance matrix, with corresponding eigenvalues representing the amount of variance explained by each component [18] [19]. The variance explained by PC1 and PC2 is particularly crucial as these components typically capture the most substantial sources of variation in the dataset, potentially reflecting key biological signals, technical artifacts, or experimental batch effects that require further investigation.

Mathematical Foundations of Variance Explanation

Computational Framework

PCA operates through a systematic computational process that transforms original variables into principal components:

Data Standardization: Before performing PCA, continuous initial variables are standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one, ensuring that variables with larger scales do not dominate the variance structure [18] [5]. This is critical in transcriptomics where expression values may span different ranges. The standardization formula for each value is:

[ Z = \frac{X-\mu}{\sigma} ]

where (\mu) is the mean of independent features and (\sigma) is the standard deviation [18].

Covariance Matrix Computation: PCA calculates the covariance matrix to understand how variables vary from the mean relative to each other [18] [5]. For a dataset with (p) variables, this produces a (p \times p) symmetric matrix where the diagonal represents variances of each variable and off-diagonal elements represent covariances between variable pairs [5].

Eigen decomposition: The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix are computed, where eigenvectors represent the directions of maximum variance (principal components), and eigenvalues represent the magnitude of variance along these directions [18] [19]. The eigenvector with the highest eigenvalue becomes PC1, followed by PC2 with the next highest eigenvalue under the orthogonality constraint [17].

Quantifying Variance Explanation

The proportion of total variance explained by each principal component is calculated by dividing its eigenvalue by the sum of all eigenvalues [17]. For the (k^{th}) component:

[ \text{Variance Explained}(PCk) = \frac{\lambdak}{\sum{i=1}^p \lambdai} ]

where (\lambda_k) is the eigenvalue for component (k), and (p) is the total number of components [17]. PC1 and PC2 collectively often capture a substantial portion of total variance in high-dimensional transcriptomics data, making them particularly informative for initial data exploration.

Table 1: Variance Explanation Interpretation Guidelines in Transcriptomics

| Variance Distribution | Potential Interpretation | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| PC1 explains >40% of variance | Single dominant technical or biological effect (e.g., batch effect, treatment response) | Investigate sample metadata for correlates; consider correction if technical |

| PC1 & PC2 explain >60% collectively | Strong structured data with potentially meaningful biological subgroups | Proceed with subgroup analysis and differential expression |

| Multiple components with similar variance | Complex dataset with multiple contributing factors | Consider additional components in analysis; explore higher-dimensional relationships |

| No components with substantial variance | Unstructured data, potentially high noise | Quality control assessment; consider alternative experimental approaches |

Methodological Protocols for Variance Analysis

Experimental Workflow for PCA in Transcriptomics Studies

The following diagram illustrates the standard analytical workflow for conducting and interpreting PCA in transcriptomics research:

Variance Interpretation Protocol

Scree Plot Analysis: Create a scree plot displaying eigenvalues or proportion of variance explained by each component in descending order [19]. The "elbow" point—where the curve bends sharply—often indicates the optimal number of meaningful components to retain for further analysis [19].

Cumulative Variance Calculation: Compute cumulative variance explained by sequential components to determine the number needed to capture a predetermined threshold of total variance (typically 70-90% in exploratory analysis) [20].

Component Loading Examination: Identify variables (genes) with the highest absolute loadings on PC1 and PC2, as these contribute most significantly to these components' variance [19]. In transcriptomics, genes with high loadings often represent biologically meaningful pathways or responses.

Sample Projection Visualization: Project samples onto the PC1-PC2 plane and color-code by experimental conditions, batches, or biological groups to identify patterns, clusters, or outliers [18] [19].

Applications in Transcriptomics Research

Spatial Transcriptomics and Domain Identification

In spatial transcriptomics, PCA-based approaches have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in identifying biologically meaningful spatial domains. The NichePCA algorithm exemplifies how a reductionist PCA approach can rival more complex methods in unsupervised spatial domain identification across diverse single-cell spatial transcriptomic datasets [21]. In this context, variance explained by PC1 and PC2 often corresponds to:

- Spatial gene expression gradients that define tissue architecture

- Cell-type-specific expression programs that segregate within complex tissues

- Regional microenvironment signatures that influence cellular function

The exceptional execution speed, robustness, and scalability of PCA-based methods make them particularly valuable for large-scale spatial transcriptomics studies in drug development contexts [21].

Quality Control and Batch Effect Detection

PC1 and PC2 frequently capture technical artifacts and batch effects that must be identified before biological interpretation:

- Batch Effects: When samples cluster by processing date, sequencing lane, or preparation batch along PC1 or PC2, this indicates technical variance dominating biological signals [19].

- Outlier Detection: Samples that appear as extreme outliers along major components often indicate quality issues requiring further investigation.

- Library Size Confounds: PCA can reveal associations between principal components and technical covariates like library size, which may confound biological interpretations if unaddressed [21].

Biological Discovery and Subtype Identification

When technical artifacts are properly accounted for, variance in PC1 and PC2 often reveals meaningful biological structure:

- Disease Subtypes: Distinct sample clusters along PC1/PC2 may represent molecularly distinct disease subtypes with therapeutic implications.

- Treatment Response: Separation of treated vs. control samples along major components suggests strong transcriptional responses to interventions.

- Developmental or Temporal Trajectories: Ordered progression of samples along PC1 may reflect continuous biological processes such as development, differentiation, or disease progression.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PCA in Transcriptomics

| Research Reagent | Function in PCA Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq kits (10x Genomics) | Generate high-dimensional transcript count data for PCA input | Single-cell spatial transcriptomics studies [21] |

| Universal Sentence Encoder (Google) | Text-to-numeric transformation for text mining integration | Converting textual metadata for integrated analysis [22] |

| Normalization algorithms (e.g., SCTransform) | Standardize library sizes before PCA | Removing technical variation that could dominate PC1 [21] |

| Spatial barcoding oligonucleotides | Enable spatial transcriptomic profiling | PCA-based spatial domain identification [21] |

| Dimensionality reduction libraries (Scikit-learn) | Perform efficient PCA computation on large matrices | Standardized implementation of PCA algorithm [18] |

Case Study: NichePCA for Spatial Domain Identification

Experimental Protocol

The following case study exemplifies the application of PCA variance analysis in spatial transcriptomics:

- Data Collection: Acquire spatial transcriptomics data using established platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics Visium, MERFISH, or Slide-seq) [21].

- Data Preprocessing: Perform standard quality control, normalization, and log-transformation of gene expression counts to minimize technical artifacts.

- PCA Implementation: Apply PCA to the normalized expression matrix using efficient computational frameworks capable of handling large-scale transcriptomic data.

- Component Selection: Retain the top k principal components based on scree plot analysis, typically capturing 50-80% of total variance in spatial transcriptomics datasets.

- Spatial Domain Assignment: Project spatial transcriptomics spots onto PC1 and PC2, using their coordinates to identify spatially coherent domains through clustering.

- Biological Validation: Validate identified domains using known marker genes and histological features to confirm biological relevance.

Interpretation Framework

The analytical process for interpreting PC1 and PC2 in spatial transcriptomics can be visualized as follows:

Performance Outcomes

In benchmark evaluations across six single-cell spatial transcriptomic datasets, the NichePCA approach demonstrated that simple PCA-based algorithms could rival the performance of ten competing state-of-the-art methods in spatial domain identification [21]. Key findings included:

- Computational Efficiency: Significantly faster execution compared to more complex neural network-based methods.

- Robust Performance: Consistent accuracy across diverse tissue types and technological platforms.

- Intuitive Interpretation: Direct mapping between component loadings and biologically meaningful gene programs.

Advanced Considerations in Variance Interpretation

Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

While PC1 and PC2 variance explanation provides valuable insights, researchers must consider several limitations:

- Non-Linear Relationships: PCA captures linear relationships only; non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE) may be required for complex datasets [19].

- Interpretation Challenges: Principal components are mathematical constructs that may not always align with discrete biological categories [18].

- Scale Sensitivity: PCA results are sensitive to data scaling decisions, requiring careful normalization approaches tailored to transcriptomic data [18].

- Information Loss: Over-reliance on only PC1 and PC2 may miss biologically important signals captured in higher components [18].

Integration with Complementary Methods

For comprehensive transcriptomics analysis, PCA should be integrated with other analytical approaches:

- Differential Expression Analysis: Use PC-defined sample groupings to guide focused differential expression testing.

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Apply gene set enrichment to high-loading genes on PC1 and PC2 to identify biological processes.

- Multi-Omics Integration: Correlate transcriptional principal components with similar components from other data modalities (e.g., epigenomics, proteomics).

The variance explained by PC1 and PC2 serves as a critical gateway to understanding high-dimensional transcriptomics data, providing a powerful framework for identifying both technical artifacts and biologically meaningful patterns. Through proper standardization, computational implementation, and interpretive protocols, researchers can leverage these components to enhance data quality assessment, reveal novel biological insights, and guide therapeutic development decisions. The continued development of PCA-based methodologies, exemplified by approaches like NichePCA in spatial transcriptomics, ensures that these fundamental dimensionality reduction techniques will remain essential tools in the evolving landscape of transcriptional research and drug development.

Identifying Sample Clustering and Biological Replicate Consistency

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a fundamental dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional transcriptomic data into a set of orthogonal variables called principal components (PCs), which capture maximum variance in the data [5] [9]. This method is particularly valuable for exploring sample clustering and assessing biological replicate consistency in RNA-seq experiments, serving as a critical first step in quality control and data exploration [23] [9].

In transcriptomics, where datasets typically contain thousands of genes (variables) measured across relatively few samples, PCA helps mitigate the "curse of dimensionality" by reducing data complexity while preserving essential patterns [24]. By projecting samples into a lower-dimensional space defined by the first few principal components, researchers can visually assess technical variability, biological consistency, and potential batch effects [23]. The application of PCA following Occam's razor principle—as demonstrated by the NichePCA algorithm for spatial transcriptomics—shows that simple PCA-based approaches can rival complex methods in performance while offering superior execution speed, robustness, and scalability [21].

Methodological Protocols for PCA in Transcriptomics

Experimental Design and RNA-seq Processing

Proper experimental design is paramount for meaningful PCA results. Biological replicates (distinct biological samples) rather than technical replicates are essential for assessing true biological variation [25] [26]. The ENCODE consortium standards recommend a minimum of two biological replicates for RNA-seq experiments, with replicate concordance measured by Spearman correlation of >0.9 between isogenic replicates [27].

For bulk RNA-seq experiments, libraries should be prepared from mRNA (polyA+ enriched or rRNA-depleted) and sequenced to a depth of 20-30 million aligned reads per replicate [27]. The ENCODE Uniform Processing Pipeline utilizes STAR for read alignment and RSEM for gene quantification, generating both FPKM and TPM values for downstream analysis [27]. To minimize batch effects, researchers should process controls and experimental conditions simultaneously, isolate RNA on the same day, and sequence all samples in the same run [23].

PCA Computational Workflow

The computational implementation of PCA follows a standardized five-step process adapted for transcriptomic data [5]:

Step 1: Data Standardization Prior to PCA, raw count data (e.g., TPM or FPKM values) must be standardized and centered to ensure each gene contributes equally to the analysis. This involves subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each gene across samples. Standardization prevents genes with naturally larger expression ranges from dominating the variance structure [5].

Step 2: Covariance Matrix Computation The standardized data is used to compute a covariance matrix that captures how all gene pairs vary together. This p×p symmetric matrix (where p equals the number of genes) identifies correlated genes that may represent redundant information [5].

Step 3: Eigen Decomposition Eigenvectors and eigenvalues are computed from the covariance matrix. The eigenvectors represent the directions of maximum variance (principal components), while eigenvalues indicate the amount of variance explained by each component [5].

Step 4: Component Selection Researchers select the top k components that capture sufficient variance (typically 70-90% cumulative variance). The feature vector is formed from the eigenvectors corresponding to these selected components [5].

Step 5: Data Projection The original data is projected onto the new principal component axes to create transformed coordinates for each sample, which are then visualized in 2D or 3D PCA plots [5].

The diagram below illustrates this workflow in transcriptomics data analysis:

Interpreting PCA Plots for Biological Replicates

Quality Assessment and Outlier Detection

PCA plots serve as powerful tools for quality assurance in transcriptomics. When analyzing biological replicates, researchers should initially examine the clustering pattern of quality control (QC) samples, which are technical replicates prepared by pooling sample extracts. These QC samples should cluster tightly on the PCA plot, indicating analytical consistency [9].

Biological replicates from the same experimental group should demonstrate intra-group similarity, appearing as clustered patterns on the PCA plot. Samples that deviate significantly from their group clusters, particularly those outside the 95% confidence ellipse, may represent outliers requiring further investigation [9]. In datasets with sufficient sample sizes, such outliers are typically excluded from subsequent analysis [9].

Assessing Replicate Consistency and Group Separation

The interpretation of PCA plots for biological replicates follows a systematic approach [9]:

Check Variance Explained: Examine how much variation PC1 and PC2 account for individually and cumulatively. Higher percentages (typically >70% combined) indicate better representation of the dataset's structure.

Assess Replicate Clustering: Well-clustered biological replicates indicate good biological repeatability and technical consistency. Dispersion within a group reflects biological variability.

Evaluate Group Separation: Distinct groupings along PC1 or PC2 suggest strong treatment effects, genetic differences, or temporal changes. Overlap between groups may indicate weak effects or the need for supervised methods.

Identify Patterns and Trends: Regular patterns across components may reveal underlying experimental factors influencing gene expression.

Table 1: Interpretation Framework for PCA Plots of Biological Replicates

| Pattern Observed | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Tight clustering of replicates within groups | High replicate consistency, low technical variation | Proceed with differential expression analysis |

| Discrete separation between experimental groups | Strong biological effect of treatment/condition | Investigate group-specific expression patterns |

| Overlapping group clusters with no clear separation | Weak or no group differences | Consider increased replication or alternative methods |

| Single outlier sample distant from group cluster | Potential sample quality issue | Examine QC metrics, consider exclusion |

| QC samples dispersed rather than clustered | Technical variability in processing | Troubleshoot experimental protocol |

Research shows that with only three biological replicates, most differential expression tools identify just 20-40% of significantly differentially expressed genes detected with higher replication [26]. This substantially rises to >85% for genes changing by more than fourfold, but to achieve >85% sensitivity for all genes requires more than 20 biological replicates [26].

Quantitative Benchmarks and Performance Metrics

Replication Guidelines from Empirical Studies

Empirical studies provide specific guidance on biological replication requirements for RNA-seq experiments. With three biological replicates, most tools identify only 20-40% of significantly differentially expressed genes detected with full replication (42 replicates), though this rises to >85% for genes with large expression changes (>4-fold) [26]. To achieve >85% sensitivity for all differentially expressed genes regardless of fold change magnitude, more than 20 biological replicates are typically required [26].

For standard transcriptomics experiments, a minimum of six biological replicates per condition is recommended, increasing to at least 12 when identifying differentially expressed genes with small fold changes is critical [26]. These guidelines ensure sufficient statistical power while considering practical constraints.

Table 2: Biological Replication Guidelines for RNA-seq Experiments

| Experimental Goal | Minimum Replicates | Sensitivity Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot studies/large effect sizes | 3-5 | 20-40% for all DE genes; >85% for >4-fold changes | Limited power for subtle expression differences |

| Standard differential expression | 6-12 | ~60-85% for all DE genes | Balance of practical constraints and statistical power |

| Comprehensive detection including subtle effects | >20 | >85% for all DE genes | Required for detecting small fold changes with high confidence |

| ENCODE standards | ≥2 | Spearman correlation >0.9 between replicates | Minimum standard for consortium data generation |

Benchmarking Clustering Performance

Recent benchmarking of 28 single-cell clustering algorithms on transcriptomic and proteomic data reveals that methods like scDCC, scAIDE, and FlowSOM demonstrate top performance across multiple metrics including Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), and clustering accuracy [28]. These methods show consistent performance across different omics modalities, suggesting robust generalization capabilities.

For assessing replicate consistency in clustering results, the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) serves as a primary metric, quantifying clustering quality by comparing predicted and ground truth labels with values from -1 to 1 [28]. Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) measures the mutual information between clustering and ground truth, normalized to [0,1], with values closer to 1 indicating better performance [28].

Implementation and Practical Applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA-seq and PCA Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | External RNA controls for normalization | Creates standard baseline for RNA quantification; Ambion Mix 1 at ~2% of final mapped reads [27] |

| Poly(A) Selection Kits | mRNA enrichment from total RNA | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA magnetic isolation kits provide high-fidelity selection [23] |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Maintain transcriptional directionality | Critical for accurately quantifying overlapping transcripts |

| CD45 Microbeads | Immune cell enrichment | Magnetic-activated cell sorting for specific cell populations [23] |

| Collagenase D | Tissue dissociation | Enzymatic digestion for single-cell suspensions [23] |

| PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | RNA extraction from sorted cells | Maintains RNA integrity from low-input samples [23] |

Troubleshooting Common PCA Challenges

Several common challenges arise when interpreting PCA plots for biological replicate consistency:

Mixed Group Clustering: When sample groups intermingle without distinct separation, reevaluate grouping criteria to ensure they represent the primary factors influencing transcriptomic profiles [9]. Consider whether other uncontrolled factors (e.g., lineage, batch effects) might be dominating the variance structure.

High Intra-group Variability: Excessive dispersion within biological replicates suggests either technical artifacts or genuine biological heterogeneity. Examine sample-level quality metrics (RNA integrity numbers, alignment rates) and consider whether the biological system inherently exhibits high variability [23] [9].

Low Cumulative Variance: When the first two principal components explain only a small percentage of total variance (<50%), the data may contain numerous technical artifacts or highly heterogeneous samples. In such cases, examine higher components (PC3, PC4) for group separation or apply batch correction methods before re-running PCA [9].

The limitations of PCA must be acknowledged in transcriptomics research. As an unsupervised method, PCA does not incorporate known group labels and may fail to highlight biologically relevant separations that are minor compared to other sources of variation [9]. When clear group differences are expected but not apparent in PCA plots, supervised methods like PLS-DA (Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis) may provide better separation [9].

PCA remains an indispensable tool for evaluating sample clustering and biological replicate consistency in transcriptomics research. By following standardized protocols for experimental design, data processing, and interpretation, researchers can extract meaningful insights from high-dimensional gene expression data. The quantitative benchmarks and methodological frameworks presented here provide actionable guidance for implementing PCA in diverse transcriptomic applications, from quality control to exploratory data analysis. As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve, PCA will maintain its role as a foundational approach for visualizing and validating the consistency of biological replicates in gene expression studies.

Detecting Outliers and Quality Control Assessment

In transcriptomic research, outliers are observations that lie outside the overall pattern of a distribution, posing significant challenges for data interpretation and analysis [29]. The high-dimensional nature of RNA sequencing data, where thousands of genes (variables) are measured across typically few biological replicates (observations), creates a classic "curse of dimensionality" problem that makes outlier detection particularly challenging [24]. In this context, outliers may arise from technical variation during complex multi-step laboratory protocols or from true biological differences, necessitating accurate detection methods to ensure research validity [29].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental tool for dimensionality reduction and quality control assessment in transcriptomics [9]. This unsupervised multivariate statistical technique applies orthogonal transformations to convert potentially intercorrelated variables into a set of linearly uncorrelated principal components (PCs), with the first component (PC1) capturing the most pronounced variance in the dataset [9]. The visualization of samples in reduced dimensional space (typically PC1 vs. PC2) enables researchers to assess sample clustering, identify outliers, and evaluate technical reproducibility [9]. However, traditional PCA is highly sensitive to outlying observations, which can distort component orientation and mask true data structure [29].

PCA Fundamentals and Visualization in Transcriptomics

Theoretical Foundation of PCA

Principal Component Analysis operates by identifying the eigenvectors of the sample covariance matrix, creating new variables (principal components) that capture decreasing amounts of variance in the data [29] [9]. For a typical RNA-seq dataset structured as an N × P matrix, where N represents the number of samples (observations) and P represents the number of genes (variables), PCA distills the essential information into a minimal number of components while preserving data covariance [24] [30]. Each principal component represents a linear combination of the original variables, with the constraint that all components are mutually orthogonal, thereby eliminating multicollinearity in the transformed data [9].

Interpreting PCA Plots for Quality Assessment

The interpretation of PCA plots follows established guidelines focused on several key aspects. Researchers should first examine the percentage of variance explained by each principal component, as higher values indicate better representation of the dataset's structure [9]. Subsequent analysis involves assessing the clustering of biological replicates, where tight clustering indicates good technical repeatability, while dispersed patterns suggest potential issues [9]. The separation between experimental groups along principal components may reflect treatment effects or biological differences of interest [9]. Finally, samples that fall beyond the 95% confidence ellipse or show substantial distance from their group peers may be classified as outliers requiring further investigation [9].

Table 1: Key Elements for PCA Plot Interpretation in Transcriptomics

| Element | Interpretation | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained | Percentage of total data variance captured by each PC | Higher percentages (>70% combined for PC1+PC2) indicate better representation of data structure |

| Replicate Clustering | Proximity of biological replicates within experimental groups | Tight clustering indicates good technical reproducibility; dispersed patterns suggest issues |

| Group Separation | Distinct grouping of samples along principal components | May reflect treatment effects, biological differences, or batch effects |

| Outlier Position | Samples distant from main clusters or beyond confidence ellipses | Potential technical artifacts, biological extremes, or sample mishandling |

Robust PCA Methods for Advanced Outlier Detection

Limitations of Classical PCA

Classical PCA (cPCA) demonstrates high sensitivity to outlying observations, which can substantially distort the orientation of principal components and compromise their ability to capture the variation of regular observations [29]. This limitation is particularly problematic in transcriptomics, where the prevalence of high-dimensional data with small sample sizes increases the potential impact of outliers on analytical outcomes [29]. Furthermore, cPCA relies on visual inspection of biplots for outlier identification, an approach that lacks statistical justification and may introduce unconscious biases during data interpretation [29].

Robust PCA Algorithms and Implementation

Robust PCA (rPCA) methods address the limitations of classical approaches by applying robust statistical theory to obtain principal components that remain stable despite outlying observations [29]. These methods simultaneously enable accurate outlier identification and categorization [29]. Two prominent rPCA algorithms include PcaHubert, which demonstrates high sensitivity in outlier detection, and PcaGrid, which exhibits the lowest estimated false positive rate among available methods [29]. These algorithms are implemented in the rrcov R package, which provides a common interface for computation and visualization [29].

The application of rPCA methods to RNA-seq data analysis has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in multiple simulated and real biological datasets. In controlled tests using positive control outliers with varying degrees of divergence, the PcaGrid method achieved 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity across all evaluations [29]. When applied to real RNA-seq data profiling gene expression in mouse cerebellum, both rPCA methods consistently detected the same two outlier samples that classical PCA failed to identify [29]. This performance advantage positions rPCA as a superior approach for objective outlier detection in transcriptomic studies.

Table 2: Comparison of PCA Methods for Outlier Detection in Transcriptomics

| Method | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical PCA | Standard covariance decomposition; Sensitive to outliers | Subjective visual inspection; Prone to missed outliers | Various R packages (stats, FactoMineR) |

| PcaHubert | Robust algorithm with high sensitivity | High detection sensitivity; Moderate false positive rate | rrcov R package |

| PcaGrid | Grid-based robust algorithm | 100% sensitivity/specificity in validation studies; Low false positive rate | rrcov R package |

Experimental Protocols for Outlier Detection

Workflow for rPCA-Based Outlier Detection

Detailed Methodological Protocol

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Quality Control Begin with raw FASTQ files from RNA sequencing experiments. Perform quality control using FastQC to assess sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [31]. Process reads with Trimmomatic to remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases using the following command structure:

Align processed reads to the appropriate reference genome using HISAT2 with default parameters [31].

Step 2: Expression Quantification and Normalization Generate count data using featureCounts from the Subread package with the following command structure:

Normalize raw counts using appropriate methods such as transcripts per million (TPM) for cross-sample comparisons or variance-stabilizing transformations for differential expression analysis [32]. For TPM calculation, use the formula: TPM = (Reads per transcript × 10^6) / (Transcript length × Total reads).

Step 3: Robust PCA Implementation Install and load required R packages:

Execute robust PCA using the PcaGrid method:

Step 4: Outlier Identification and Validation Calculate statistical cutoffs for outlier classification based on robust distances. Implement Tukey's fences method using the interquartile range (IQR):

Validate identified outliers through biological investigation, including sample metadata review, experimental condition verification, and potential technical artifact assessment [29] [33].

Quantitative Assessment of Outlier Detection Methods

Performance Metrics and Statistical Cutoffs

The accurate identification of outliers requires establishing appropriate statistical thresholds that balance detection sensitivity with false positive rates. Research indicates that using interquartile ranges (IQR) around the median of expression values provides robust outlier identification less affected by data skewness and extreme values [32]. Tukey's fences method identifies outliers as data falling below Q1 - k × IQR or above Q3 + k × IQR, where Q1 and Q3 represent the 1st and 3rd quartiles, respectively [32]. For conservative outlier detection in transcriptomic data, a threshold of k = 5 (corresponding to approximately 7.4 standard deviations in a normal distribution) effectively minimizes false positives while maintaining detection capability [32].

Empirical studies demonstrate that at k = 3, approximately 3-10% of all genes (approximately 350-1350 genes) exhibit extreme outlier expression in at least one individual across various tissues [32]. These numbers continuously decline with increasing k-values without a clear natural cutoff, supporting the selection of more conservative thresholds for rigorous outlier detection [32]. The number of detectable outlier genes directly correlates with sample size, with approximately half of the outlier genes remaining detectable even with only 8 individuals sampled [32].

Impact of Outlier Removal on Downstream Analysis

The removal of technical outliers significantly improves the performance of differential gene expression detection and subsequent functional analysis [29]. Comparative studies evaluating eight different data analysis strategies demonstrated that outlier removal without batch effect modeling performed best in detecting biologically relevant differentially expressed genes validated by quantitative reverse transcription PCR [29]. In classification studies, the removal of outliers notably changed classification performance, with improvement observed in most cases, highlighting the importance of reporting classifier performance both with and without outliers for accurate model assessment [33].

Table 3: Impact of Outlier Removal on Transcriptomics Analysis

| Analysis Type | Impact of Outlier Retention | Impact of Outlier Removal | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Decreased statistical power; Inflated variance | Improved detection of biologically relevant DEGs | qRT-PCR validation [29] |

| Classification Accuracy | Inflated or deflated performance estimates | More reproducible classifier performance | Bootstrap validation [33] |

| Pathway Analysis | Potentially spurious pathway identification | More biologically plausible functional enrichment | Literature consistency [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics Outlier Detection

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| rrcov R Package | Implementation of robust PCA methods | Primary package for PcaGrid and PcaHubert algorithms [29] |

| FastQC | Quality control of raw sequence data | Identifies potential technical issues in sequencing [31] |

| Trimmomatic | Read trimming and adapter removal | Improves data quality before alignment [31] |

| HISAT2 | Read alignment to reference genome | Generates BAM files for expression quantification [31] |

| featureCounts | Gene-level expression quantification | Generates count matrix from aligned reads [31] |

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis | Includes variance-stabilizing transformation for PCA input [32] |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Biological Significance of Expression Outliers

Emerging research challenges the conventional practice of automatically dismissing all outlier expression values as technical artifacts. Studies demonstrate that outlier gene expression patterns represent a biological reality occurring universally across tissues and species, potentially reflecting "edge of chaos" effects in gene regulatory networks [32]. These patterns manifest as co-regulatory modules, some corresponding to known biological pathways, with sporadic generation rather than Mendelian inheritance [32]. In rare disease diagnostics, transcriptome-wide outlier patterns have successfully identified individuals with minor spliceopathies caused by variants in minor spliceosome components, demonstrating the diagnostic value of systematic outlier analysis [34] [35].

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

While PCA and robust PCA provide powerful approaches for outlier detection, researchers should acknowledge their limitations. PCA represents an unsupervised method that does not incorporate known group labels, potentially limiting its ability to capture condition-specific effects [9]. The interpretability of principal components decreases substantially beyond the first few components, potentially burying important biological variation in lower dimensions [9]. Furthermore, concerns have been raised about the potential for PCA results to be manipulated through selective sample or marker inclusion, highlighting the importance of transparent reporting and methodological rigor [30]. These limitations emphasize the necessity of complementing PCA with other quality assessment methods and biological validation to ensure robust research conclusions.

Recognizing Batch Effects and Technical Artifacts

In high-throughput transcriptomics research, batch effects represent systematic technical variations introduced during experimental processes that are unrelated to the biological variables of interest. These artifacts arise from differences in technical conditions such as sequencing runs, reagent lots, personnel, or instruments and can profoundly distort downstream analysis if not properly identified and mitigated [36] [37]. The primary challenge lies in distinguishing these technical artifacts from true biological signals, as batch effects can masquerade as apparent biological patterns in unsupervised analyses [38].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as an indispensable tool for quality assessment and exploratory data analysis in transcriptomics. By transforming high-dimensional gene expression data into a lower-dimensional space defined by principal components (PCs), PCA reveals the major sources of variation across samples [38] [3]. When applied systematically, PCA provides critical insights into data structure, enabling researchers to identify batch effects, detect sample outliers, and uncover underlying biological patterns before proceeding with more specialized analyses [38]. This technical guide outlines comprehensive methodologies for recognizing and addressing batch effects within the context of PCA-based transcriptomics research.

Detecting Batch Effects via PCA Visualization

Fundamental Principles of PCA for Transcriptomics

PCA reduces the complexity of transcriptomic datasets containing thousands of gene expression measurements by identifying orthogonal directions of maximum variance, known as principal components. The algorithm decomposes the data matrix into PCs ordered by the amount of variance they explain, with the first PC (PC1) capturing the largest source of variation, the second PC (PC2) the next largest, and so on [3]. For gene expression data, samples are typically represented as rows and genes as columns in the input matrix, which is often centered and scaled to ensure all genes contribute equally to the analysis [38] [3].

The three key pieces of information obtained from PCA include:

- PC scores: Coordinates of samples in the new PC space

- Eigenvalues: Variance explained by each PC

- Variable loadings: Weight or correlation of each original variable with the PCs [3]

In transcriptomics, PCA enables researchers to project high-dimensional gene expression data onto 2D or 3D scatterplots using the first few PCs, making patterns of similarity and difference between samples visually accessible [3].

Interpreting PCA Plots for Batch Effect Identification

Batch effects in PCA plots manifest as distinct clustering of samples according to technical rather than biological variables. The table below outlines key visual indicators of batch effects in PCA visualizations:

Table 1: Identifying Batch Effects in PCA Plots

| Observation | Suggests Batch Effect | Suggests Minimal Batch Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Clustering by Color (Batch) | Different batches form separate, distinct clusters | Batches are thoroughly mixed together |

| Sample Separation by Shape (Biological Group) | No clear pattern by biological group | Clear separation according to biological conditions |

| Confidence Ellipses | Ellipses for different batches are separate with minimal overlap | Ellipses for biological groups are distinct, while batch ellipses overlap substantially |

| PC Variance Explanation | Very high percentage of variance explained by early PCs, potentially indicating technical dominance | Balanced variance distribution across PCs |

| Outlier Patterns | Samples cluster strictly by processing date, operator, or instrument | Outliers may exist but don't correlate with technical factors |

When examining PCA plots, researchers should follow a systematic approach: First, note the percentage of variance explained by each PC (higher values in early PCs may indicate dominant technical artifacts). Second, observe whether samples cluster by batch labels rather than biological groups. Third, assess whether within-batch distances are smaller than between-batch distances for similar biological samples [39].

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for detecting batch effects using PCA:

Quantitative Assessment of Batch Effects

Beyond visual inspection, several quantitative metrics help confirm the presence of batch effects:

- Percentage of Variance Explained: When PC1 explains an exceptionally high percentage of total variance (often >30-50%), this may indicate a dominant technical artifact [39]

- Distance Metrics: Mean distances between batches should be compared to mean distances within batches and between biological groups

- Standard Deviation Ellipses: Calculating multivariate standard deviation ellipses at 2.0 and 3.0 standard deviations helps identify outliers that may represent batch effects [38]

Table 2: Variance Patterns and Their Interpretation in PCA

| Variance Pattern | Potential Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| PC1 explains >50% variance | Strong batch effect or dominant technical factor | Investigate experimental processing dates and technical variables |

| Variance spread evenly across multiple PCs | Biological complexity or multiple biological factors | Proceed with biological interpretation |

| Early PCs show batch clustering | Significant batch effect requiring correction | Apply batch correction before biological analysis |

| Later PCs show biological patterns | Biological signal masked by technical variation | Use supervised approaches or batch correction |

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Assessment

PCA Computation and Visualization Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol outlines the standard methodology for performing PCA to assess batch effects in transcriptomic data using R:

Data Preprocessing: Begin with normalized count data. Filter out low-expressed genes (e.g., keeping genes expressed in at least 80% of samples). Transform the count matrix as needed (e.g., log transformation for RNA-seq data) [37].

Matrix Transformation: Transpose the filtered count matrix so that samples become rows and genes become columns, preparing for PCA computation [3].

PCA Computation: Use R's

prcomp()function, typically withscale. = TRUEto ensure all genes contribute equally regardless of their original expression levels [3].Variance Calculation: Compute the percentage of variance explained by each principal component to inform interpretation [3].

Visualization: Create a PCA plot colored by batch and shaped by biological condition using ggplot2 or similar packages [37].

Quality Control and Outlier Detection Protocol

Effective PCA-based quality assessment includes systematic outlier detection:

Standard Deviation Threshold Method: Calculate multivariate standard deviation ellipses in PCA space with common thresholds at 2.0 and 3.0 standard deviations, corresponding to approximately 95% and 99.7% of samples as "typical," respectively [38].