Low Abundance Gene Quantification: RNA-Seq vs qPCR - A Researcher's Guide to Accuracy and Application

Accurately quantifying low-abundance transcripts is critical for advancing research in drug development, biomarker discovery, and understanding complex disease mechanisms.

Low Abundance Gene Quantification: RNA-Seq vs qPCR - A Researcher's Guide to Accuracy and Application

Abstract

Accurately quantifying low-abundance transcripts is critical for advancing research in drug development, biomarker discovery, and understanding complex disease mechanisms. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists comparing two cornerstone technologies: quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq). We explore the foundational principles of each method, detail their specific applications and methodologies for challenging targets, address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate technical artifacts and enhance sensitivity, and present a direct comparative analysis to guide technology selection for validation studies. By synthesizing current evidence and best practices, this review empowers professionals to make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and impact of their gene expression studies.

The Critical Challenge of Low-Abundance Transcripts in Biomedical Research

Low-abundance genes, while challenging to detect and quantify, play disproportionately significant roles in cellular regulation, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting. Their expression profiles offer critical insights into pathological states and represent promising biomarker candidates for early disease detection. This technical review examines the comparative capabilities of RNA-Seq and qPCR for quantifying low-abundance transcripts, evaluating methodological precision, experimental requirements, and analytical considerations. We synthesize evidence from recent studies that benchmark these technologies across various applications, from single-cell analysis to clinical biomarker discovery. The findings indicate that method selection profoundly impacts detection reliability for low-expression genes, with implications for research validity and clinical translation. We provide evidence-based guidelines for optimizing experimental designs to accurately capture the biological significance of these molecularly elusive yet functionally critical genetic elements.

Low-abundance transcripts, often expressed at mere copies per cell, constitute a substantial portion of the transcriptome with outsized functional importance. These genes frequently encode key regulatory molecules including transcription factors, signaling receptors, and non-coding RNAs that govern critical cellular processes. Their expression patterns provide sensitive indicators of pathological states, yet their quantification presents substantial technical challenges due to their low expression levels and susceptibility to technical noise.

The detection of low-abundance genes has profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms. In oncology, minority alleles and mutation-bearing transcripts present at low frequencies can signal emergent treatment resistance [1]. In immunology, differential expression of HLA genes at low levels significantly modifies disease outcomes for HIV, autoimmune conditions, and cancer [2]. Furthermore, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies reveal that low-abundance transcripts enable fine discrimination of cell states and types, but require specialized approaches for reliable quantification [3].

Accurate measurement of these genes is technically demanding. Research indicates that low-abundance RNAs exhibit high missing rates in sequencing data - approximately 90% at single-cell level and 40% even in pseudo-bulk analyses [3]. This detection failure stems from methodological limitations rather than biological absence, underscoring the critical importance of selecting appropriate quantification strategies for research and clinical applications.

Technical Challenges in Quantifying Low-Abundance Genes

Fundamental Detection Limitations

Quantifying low-abundance genes presents distinct challenges that differ significantly from measuring moderately or highly expressed transcripts. The dominant source of error for low-abundance RNAs in RNA-Seq is Poisson sampling noise due to finite read depth [4]. This stochastic sampling variation means that insufficient reads map to these transcripts for reliable quantification, leading to high measurement variability and reduced statistical power for detecting differential expression.

The relationship between gene expression level and measurement precision demonstrates that lower expression correlates strongly with higher relative error [4]. While highly expressed transcripts can be measured with relative errors of 20% or less, only 41% of all transcript targets achieve this precision level across technical replicates. For the 41% most strongly expressed transcripts, 84% can be measured reliably, indicating a strong expression-level bias in quantification accuracy.

Platform-Specific Constraints

RNA-Seq Limitations

In RNA-Seq, increased sequencing depths yield diminishing returns for low-abundance transcript detection. While 100 million reads generally detect most expressed genes, approximately 500 million reads are needed to accurately quantify 72% of gene expression levels [4]. Beyond this point, additional sequencing provides minimal gains for low-abundance targets because high-abundance transcripts dominate sequencing capacity - 7% of abundant transcripts consume over 75% of all read alignments [4]. Extrapolation studies suggest a maximum of 60% of all known transcripts can be measured reliably even at theoretically impractical depths of 10 billion reads [4].

Additional RNA-Seq complications include:

- Normalization artifacts: RPKM and TPM assume constant total RNA content across samples, causing distortion in low-abundance transcript comparisons when overall RNA composition differs [4]

- Library preparation biases: PCR amplification preferentially amplifies certain sequences, while GC content and sequence composition affect reverse transcription efficiency [5]

- RNA degradation effects: Degradation underrepresents longer transcripts and overrepresents 3' ends, disproportionately affecting already scarce targets [5]

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Considerations

scRNA-seq exhibits particularly pronounced challenges for low-abundance genes, with average missing rates of 90% at the single-cell level [3]. This "dropout" phenomenon results from technical factors including low mRNA input, capture efficiency, amplification bias, and limited sequencing depth. Precision and accuracy are generally low at single-cell resolution, with reproducibility strongly influenced by cell count and RNA quality [3].

Comparative Analysis of Quantification Platforms

RNA-Seq Versus qPCR: Performance Benchmarks

Multiple studies have systematically compared RNA-Seq and qPCR for gene expression quantification, revealing method-specific strengths and limitations particularly relevant for low-abundance genes.

Table 1: RNA-Seq vs. qPCR Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | RNA-Seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Higher dynamic range [5] | Limited dynamic range |

| Sensitivity | Can detect low-abundance transcripts but with precision limitations [4] | Highly sensitive and specific, suitable for validating RNA-seq results [5] |

| Throughput | Genome-wide, unbiased approach [5] | Practical for small-to-medium gene sets [6] |

| Low-Abundance Precision | Struggles with accurate quantification of low-abundance transcripts [4] | High precision for targeted low-abundance genes [2] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Essentially unlimited | Limited to few targets per reaction without extensive optimization [6] |

| Novel Feature Discovery | Detects novel transcripts, isoforms, and variants [5] | Restricted to known sequences |

A comprehensive benchmarking study using the MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples demonstrated high gene expression correlations between RNA-Seq and qPCR data across five processing workflows (Pearson correlation R² = 0.798-0.845) [7]. However, when comparing fold changes between samples, approximately 15-19% of genes showed inconsistent differential expression calls between RNA-Seq and qPCR [7]. These inconsistent genes were typically shorter, had fewer exons, and were lower expressed compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [7].

For HLA gene quantification, a specialized comparison revealed only moderate correlation between qPCR and RNA-Seq (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53 for HLA-A, -B, and -C) despite using HLA-tailored bioinformatic pipelines [2]. This highlights the particular challenges in quantifying polymorphic low-abundance genes.

Microarray Capabilities for Low-Abundance Transcripts

Despite being an older technology, microarrays demonstrate particular advantages for low-abundance RNA profiling. In contrast to RNA-Seq, where high-abundance RNAs consume disproportionate sequencing capacity, microarray hybridization minimizes cross-target competition - the presence of unrelated high-abundance sequences little affects detection of poorly-expressed transcripts [4].

This technical difference translates to practical sensitivity advantages. For long non-coding RNAs, microarrays routinely detect 7,000-12,000 species compared to only 1,000-4,000 detectable by RNA-Seq even with >120 million reads [4]. This superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets has led researchers to select microarrays over RNA-Seq in clinical studies where detection sensitivity is paramount [4].

Emerging Platforms and Methodological Innovations

Digital PCR

Digital PCR (dPCR) provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids by partitioning reactions into thousands of individual amplifications. Recent comparisons of droplet-based (ddPCR) and nanoplate-based (ndPCR) systems show both platforms achieve high precision across most analyses with similar detection and quantification limits [8]. dPCR demonstrates particular advantages for quantifying targets present in low abundances and is less susceptible to inhibition from sample matrix effects compared to qPCR [8].

Key dPCR performance characteristics:

- Limit of Detection: 0.17 copies/µL for ddPCR, 0.39 copies/µL for ndPCR [8]

- Limit of Quantification: 4.26 copies/µL for ddPCR, 1.35 copies/µL for ndPCR [8]

- Precision: Coefficient of variation 6-13% for ddPCR, 7-11% for ndPCR [8]

Targeted RNA-Seq Approaches

Targeted sequencing methods focusing on specific gene subsets address some limitations of whole transcriptome RNA-Seq. However, primer amplification-based targeted approaches face development challenges and typically content limits of 500-1000 genes [6]. These methods still require RNA extraction and reverse transcription but can enhance sensitivity for predetermined target sets.

Single-Cell and Single-Nucleus RNA-Seq

scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq enable resolution of low-abundance transcripts at cellular resolution but require specialized experimental designs. Evidence-based guidelines recommend at least 500 cells per cell type per individual to achieve reliable quantification [3]. The signal-to-noise ratio is a key metric for identifying reproducible differentially expressed genes in single-cell studies [3].

Experimental Design Considerations for Low-Abundance Gene Analysis

RNA-Seq Optimization Strategies

Table 2: RNA-Seq Experimental Design Recommendations

| Parameter | Recommendation | Impact on Low-Abundance Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | 20-30 million reads for standard applications; >100 million for rare transcripts [5] | Higher depth improves low-abundance detection but with diminishing returns [4] |

| Biological Replicates | Minimum 3 per condition [5] | Critical for statistical power to detect differential expression of low-abundance genes |

| RNA Quality | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment; DNase treatment [5] | Prevents degradation artifacts and genomic DNA contamination |

| Library Preparation | Consistent methods across samples; PCR-free options available [5] | Reduces technical variability and amplification biases |

| Multiplexing | Unique barcodes for sample pooling [5] | Enables cost-effective deeper sequencing |

Method Selection Guidelines

Research objectives should drive platform selection for low-abundance gene studies:

- Hypothesis-free discovery: RNA-Seq provides unbiased genome-wide coverage but requires validation of low-abundance findings [5]

- Targeted quantification of known genes: qPCR or dPCR offer superior sensitivity and precision for defined gene sets [2] [8]

- Clinical biomarker applications: Microarrays or targeted RNA-Seq may provide better sensitivity for specific low-abundance targets [4]

- Single-cell resolution: scRNA-seq requires specialized normalization and sufficient cell numbers (≥500 per cell type) [3]

For RNA-Seq data processing, quantification methods show varying performance for low-abundance genes. Studies evaluating isoform expression quantification found Net-RSTQ and eXpress provide more consistent results across platforms compared to Cufflinks, RSEM, or Kallisto [9].

Applications in Disease Research and Biomarker Development

Cancer Genomics

Low-abundance gene mutations serve as critical biomarkers in oncology. Detection of EGFR mutations (L747_S752 del, G719A, T790M) present at frequencies as low as 1% enables identification of resistant subclones in non-small cell lung cancer [1]. Novel enrichment methods like combined polymerase and ligase chain reaction can selectively amplify these minority alleles from background wild-type sequences, dramatically improving detection sensitivity [1].

Immunology and Infectious Disease

HLA expression levels quantitatively influence disease outcomes, with low-level variations significantly modifying HIV progression, autoimmune risk, and viral control [2]. These effects persist despite modest expression differences, highlighting the functional importance of precise low-abundance quantification. For example, higher HLA-C expression associates with better HIV control, while elevated HLA-A expression impairs it [2].

Neurological Disorders

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing of brain tissues reveals cell-type-specific low-abundance transcripts with implications for neurological diseases. However, studies consistently show inadequate cell numbers for specific neuronal subtypes in even large-scale datasets, limiting detection power for rare transcripts in functionally important cell populations [3].

Accurate quantification of low-abundance genes remains technically challenging but biologically essential. Method selection should be guided by research objectives, with RNA-Seq providing discovery potential and targeted approaches (qPCR, dPCR) offering validation rigor. No single platform currently optimizes all parameters - sensitivity, precision, throughput, and cost must be balanced based on experimental needs.

Emerging methodologies including molecular indexing, unique molecular identifiers, and partitioned amplification strategies show promise for enhancing low-abundance detection. Additionally, cross-platform validation remains critical for studies where low-abundance genes drive primary conclusions. As evidence accumulates regarding the functional significance of precisely tuned low-level gene expression, methodological rigor in quantifying these molecularly elusive targets becomes increasingly fundamental to biological insight and clinical translation.

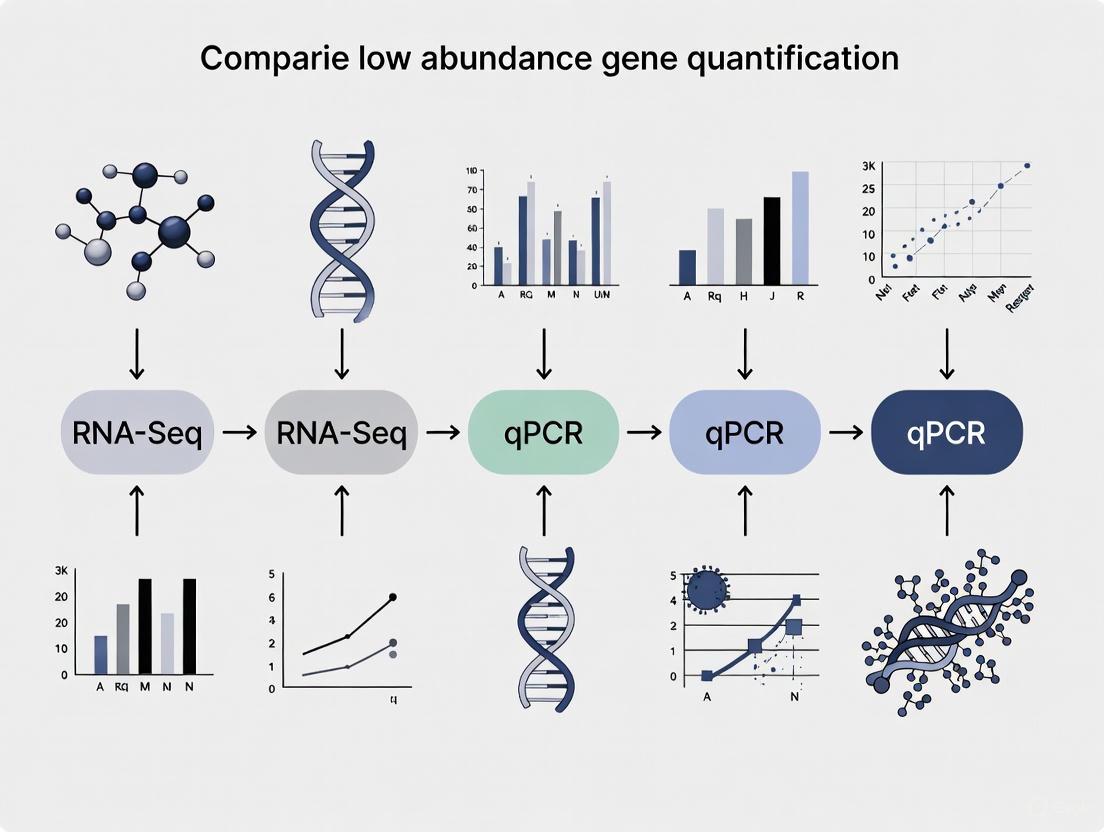

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Low-Abundance Gene Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Low-Abundance Gene Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | RNAlater, PAXgene | Preserves RNA integrity, critical for low-abundance targets |

| Reverse Transcriptase | SuperScript IV, LunaScript | High efficiency reverse transcription maximizes cDNA yield |

| Target Enrichment | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNAs, enhancing detection sensitivity |

| Library Preparation | SMARTer Stranded, KAPA HyperPrep | Minimizes bias in RNA-Seq library construction |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | IDT UMI Adapters | Distinguishes biological signal from amplification noise |

| Digital PCR Reagents | ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix, QIAcuity PCR Master Mix | Enables absolute quantification of rare targets |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Ambion Nuclease-Free Water | Prevents RNA degradation during experimental procedures |

The accurate quantification of gene expression is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, with critical applications in basic research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. Among the various technologies available, quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) have emerged as two principal methods for measuring transcript abundance. While qPCR is widely recognized for its sensitivity, accuracy, and low cost, RNA-seq provides a comprehensive, genome-wide view of the transcriptome [10]. The selection between these methods becomes particularly crucial when investigating low-abundance transcripts, which often include key regulatory genes, transcription factors, and non-coding RNAs. Understanding the fundamental principles, technical requirements, and limitations of each technology is essential for designing robust experiments and generating reliable data, especially when quantifying rare transcripts that may drive important biological processes or serve as biomarkers in disease states.

Fundamental Principles of qPCR

Core Mechanism and Quantification

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, is a method for detecting and quantifying specific DNA sequences in real-time as amplification occurs. The fundamental principle relies on monitoring the fluorescence emitted during each PCR cycle, which is directly proportional to the amount of amplified product. The key quantification parameter is the quantification cycle (Cq), previously known as Ct or Cp value, which represents the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a predetermined threshold [11]. This threshold is set within the exponential phase of amplification, where the reaction efficiency is optimal. The Cq value is inversely correlated with the initial template concentration: a lower Cq indicates a higher starting amount of the target sequence, while a higher Cq corresponds to a lower initial abundance [11]. According to the MIQE guidelines, Cq values above 30-35 are often considered unreliable for quantification due to poor reproducibility, presenting a significant challenge for low-abundance transcripts [12].

Detection Chemistry and Signal Generation

qPCR utilizes various fluorescence-based detection chemistries, with the two most common being:

- DNA-binding dyes: Non-specific intercalating dyes like SYBR Green that fluoresce when bound to double-stranded DNA.

- Fluorogenic probes: Sequence-specific probes such as TaqMan probes that utilize fluorescence resonance energy transfer and provide higher specificity through an oligonucleotide probe with a reporter and quencher dye.

The fluorescence signal is captured by specialized instruments during each amplification cycle, generating amplification plots that track fluorescence versus cycle number. Proper baseline correction and threshold setting are critical for accurate Cq determination, as incorrect settings can significantly alter calculated Cq values and subsequent quantification [11].

Quantitative Analysis Methods

qPCR data can be analyzed using two primary quantification strategies:

- Absolute quantification: Determines the exact copy number of the target sequence by comparison to a standard curve of known concentrations.

- Relative quantification: Compares the expression level of a target gene between different samples after normalization to one or more reference genes. The efficiency-adjusted model (Pfaffl method) accounts for variations in amplification efficiency between different targets, providing more accurate results than methods that assume 100% efficiency [11].

Diagram 1: qPCR Workflow and Quantification Principle. This diagram illustrates the multi-step process from RNA sample to quantitative results, highlighting the critical role of proper threshold setting and baseline correction during data analysis.

Fundamental Principles of RNA-Seq

High-Throughput Sequencing Approach

RNA-seq is a comprehensive, high-throughput method that utilizes next-generation sequencing technologies to profile the entire transcriptome. Unlike qPCR, which targets specific known sequences, RNA-seq provides an unbiased view of RNA populations without prior knowledge of gene sequences. The core principle involves converting RNA populations into a library of cDNA fragments with adapters attached to one or both ends, followed by sequencing these fragments in a massively parallel manner to generate short reads [13]. These reads are then mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome, and the expression level for each gene is quantified based on the number of reads that map to its exonic regions. Normalization methods such as FPKM or TPM account for gene length and sequencing depth, enabling comparisons between genes within a sample and across different samples.

Bioinformatics Processing and Challenges

The analysis of RNA-seq data involves multiple computational steps that present unique challenges, particularly for complex gene families like the Human Leukocyte Antigen system. Standard alignment approaches that rely on a single reference genome often fail to accurately represent the extreme polymorphism and sequence similarity between paralogs at HLA loci, leading to misalignment and biased quantification [2]. This has motivated the development of specialized computational pipelines that account for known HLA diversity during the alignment step, significantly improving expression estimation accuracy for these challenging genes [2]. Additional technical biases in RNA-seq can arise from batch effects, library preparation protocols, and GC content variations, which must be carefully controlled during experimental design and data analysis ['t Hoen et al. 2013 as cited in citation:1].

Visualization and Interpretation

Advanced visualization approaches are essential for interpreting the complex data generated by RNA-seq, particularly for analyzing transcript isoforms and splice variants. While traditional tools like the Integrative Genomics Viewer display reads stacked onto a genomic reference, graph-based visualization methods offer complementary insights into transcript diversity [13]. These methods represent RNA-seq assemblies as networks where nodes correspond to reads and edges represent sequence similarity, enabling better appreciation of complex transcript topology in 3D space. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying issues in assembly, detecting repetitive sequences within transcripts, and characterizing splice variants that might be missed by reference-based methods [13].

Diagram 2: RNA-seq Workflow and Analysis Pipeline. This diagram outlines the key steps in RNA-seq processing, highlighting both standard procedures and specialized approaches needed for accurate analysis of complex gene families and transcript isoforms.

Comparative Analysis: qPCR vs. RNA-Seq

Technical Performance and Applications

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of qPCR and RNA-seq is essential for selecting the appropriate method for specific research applications, particularly when investigating low-abundance transcripts.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of qPCR and RNA-Seq Technologies

| Parameter | qPCR | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High sensitivity for known targets; limited for Cq >30-35 [12] | Variable sensitivity; requires sufficient sequencing depth for low-abundance targets |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Traditionally limited to 4-6 targets; advanced methods like CCMA enable higher multiplexing [14] | Genome-wide; profiles all transcripts simultaneously |

| Throughput | Low to medium throughput; limited by reaction number | High throughput; sequences millions of fragments in parallel |

| Dynamic Range | ~7-8 log range; suitable for abundant and moderate targets | ~5 log range; limited for very low and very high expression |

| Target Requirement | Requires prior sequence knowledge for primer/probe design | No prior knowledge needed; enables novel transcript discovery |

| Quantitative Accuracy | High accuracy for proper targets; gold standard for validation [10] | Moderate accuracy; subject to various technical biases |

| Cost per Sample | Low to moderate | Moderate to high, especially with deep sequencing |

| Turnaround Time | Fast (<2 hours after cDNA synthesis) [12] | Moderate to long (days to weeks including data analysis) |

| Data Complexity | Simple; direct Cq interpretation | Complex; requires advanced bioinformatics expertise |

Correlation Between Technologies

Direct comparisons between qPCR and RNA-seq have revealed important insights about their correlation and appropriate applications. A 2023 study analyzing HLA class I gene expression found only moderate correlation between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq, with correlation coefficients (rho) ranging from 0.2 to 0.53 for HLA-A, -B, and -C genes [2]. This moderate correlation highlights the technical challenges in comparing results across these different platforms, including differences in what each method actually measures (specific amplicons vs. overall gene representation) and the various normalization strategies employed. However, RNA-seq has been shown to accurately estimate gene expression means compared to qPCR when appropriate bioinformatic approaches are used, though measures of expression variability may differ significantly, particularly across different environmental conditions [10].

Advanced Methodologies for Low-Abundance Transcript Detection

Enhancing qPCR Sensitivity

The inherent sensitivity limitation of conventional qPCR for low-abundance transcripts (Cq >30) has prompted the development of innovative pre-amplification strategies. The STALARD method provides a targeted approach that selectively amplifies polyadenylated transcripts sharing a known 5'-end sequence before quantification [12]. This two-step process involves reverse transcription using a gene-specific primer-tailed oligo(dT) primer, followed by limited-cycle PCR using only the gene-specific primer. This approach minimizes amplification bias caused by differential primer efficiency when comparing similar transcripts, a common challenge in isoform-specific qPCR. When applied to the low-abundance VIN3 transcript in Arabidopsis thaliana, STALARD successfully amplified the target to reliably quantifiable levels that conventional RT-qPCR failed to detect [12].

Reference Gene Selection Strategies

Accurate normalization is crucial for both qPCR and RNA-seq data interpretation, particularly for low-abundance targets where technical variation can have substantial effects. Traditional housekeeping genes often exhibit unexpectedly high expression variance across different conditions, compromising their utility as normalizers [10]. RNA-seq enables a whole-transcriptome approach to reference gene selection, identifying stably expressed genes that outperform classical housekeeping genes. Recent research demonstrates that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform single reference genes for qPCR data normalization [15]. This approach identifies a fixed number of genes whose individual expressions balance each other across experimental conditions, providing more robust normalization than single reference genes.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TaqPath ProAmp Master Mix | Enzyme mix for robust amplification | qPCR reactions, including CCMA [14] |

| HiScript IV 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | High-efficiency reverse transcription | cDNA synthesis for both qPCR and RNA-seq library prep [12] |

| AMPure XP SPRI magnetic beads | Nucleic acid purification and size selection | Library cleanup for RNA-seq; PCR product purification [14] [12] |

| Gene-Specific Primers with Tailored Thermodynamics | Target-specific amplification | STALARD method for low-abundance transcripts [12] |

| HLA-Tailored Bioinformatics Pipelines | Accurate alignment of polymorphic sequences | RNA-seq analysis of extreme polymorphism at HLA loci [2] |

| Graphia Professional | Network-based visualization of transcript assemblies | RNA-seq data interpretation and isoform analysis [13] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Optimizing experimental design is particularly critical when studying low-abundance transcripts. For qPCR, the MIQE guidelines provide a framework for ensuring data quality, including proper validation of amplification efficiency, determination of the lower limit of quantification, and selection of appropriate reference genes [11] [12]. When using RNA-seq for low-abundance targets, sufficient sequencing depth must be prioritized to ensure adequate coverage of rare transcripts. Specialized library preparation methods, such as those incorporating targeted enrichment or ribosomal RNA depletion, can significantly improve detection of low-abundance targets. Additionally, experimental conditions significantly impact expression variability measures, suggesting that reference genes should be selected using transcriptome data that either specifically matches the study conditions or covers a broad range of biological and environmental diversity [10].

Both qPCR and RNA-seq offer powerful but distinct approaches to gene expression quantification, with complementary strengths that can be strategically leveraged in research and diagnostic applications. qPCR remains the gold standard for sensitive, accurate quantification of known targets, while RNA-seq provides an unparalleled comprehensive view of the transcriptome. For low-abundance gene quantification, methodological innovations like STALARD for qPCR and specialized bioinformatic pipelines for RNA-seq are pushing the boundaries of what these technologies can detect. The selection between these methods should be guided by the specific research question, target abundance, required throughput, and available resources. As both technologies continue to evolve, their synergistic application—using RNA-seq for discovery and qPCR for validation—will continue to drive advances in our understanding of gene regulation in health and disease.

The accurate quantification of gene expression, especially for low-abundance transcripts, is a cornerstone of modern molecular research in fields like drug development and clinical diagnostics. The choice of technology directly influences the biological conclusions that can be drawn. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison between two cornerstone technologies—quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)—focusing on their sensitivity, dynamic range, and their consequent impact on reliable detection.

While RNA-seq is often considered the gold standard for whole-transcriptome analysis, its performance is highly dependent on sequencing depth and data processing workflows [16]. In contrast, qPCR remains the benchmark for sensitive and precise quantification of specific targets [17] [18]. Understanding the technical boundaries of each method is essential for designing robust experiments, interpreting data correctly, and ultimately, for making confident decisions in research and development.

Quantitative Face-Off: qPCR vs. RNA-Seq

Direct comparisons between qPCR and RNA-Seq reveal a complex performance landscape. The following tables summarize key comparative data and technical specifications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of qPCR and RNA-Seq from Benchmarking Studies

| Metric | qPCR | RNA-Seq (Various Workflows) | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Correlation | Benchmark | R²: 0.798 - 0.845 [16] | Pearson correlation to qPCR data for protein-coding genes. |

| Fold-Change Correlation | Benchmark | R²: 0.927 - 0.934 [16] | Correlation of MAQCA/MAQCB fold changes with qPCR. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | Well-defined (e.g., 0.003 pg/reaction) [19] | Read-count dependent (e.g., ~20 counts) [20] | RNA-Seq's LoD is probabilistic and varies with sequencing depth. |

| Limit of Quantification (LoQ) | Defined via standard stats (e.g., 0.03 pg/reaction) [19] | Not strictly defined | RNA-Seq quantification reliability is a gradient [20]. |

| Impact on Differential Expression | N/A | ~85% concordance with qPCR; 15% non-concordant genes [16] | Inconsistent genes are often lower expressed, smaller, with fewer exons [16]. |

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Dynamic Range

| Characteristic | qPCR | Bulk RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Dynamic Range | Up to 9 logs [18] | Dependent on read depth [20] |

| Effective Dynamic Range | Constrained by sample quality, RT efficiency [18] | ~10,000 genes detectable at 10 million reads [20] |

| Key Precision Metric | Coefficient of Variation (CV) [18] | Reproducibility between replicates [16] [20] |

| Primary Normalization | Fundamental (absolute) or relative units [18] | Counts, TPM, FPKM [20] |

| Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Targets | Very high for targeted assays [19] [17] | Lower for genes with counts <20; improved with greater depth [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking and Validation

Protocol for qPCR Assay Validation for Residual DNA Detection

This protocol, adapted from a study validating a test for residual Vero cell DNA in vaccines, outlines the key steps for establishing a sensitive and precise qPCR assay [19].

Step 1: Target and Primer/Probe Design

- Select a target sequence unique to the genome of interest, with a high copy number to enhance sensitivity. For Vero cells, a 172 bp tandem repeat sequence (~6.8x10^6 copies/haploid genome) was used [19].

- Design primers and probes for a short amplicon (e.g., 99 bp) to maximize amplification efficiency and robustness.

- Example Sequences: [19]

- Forward Primer:

5′-CTGCTCTGTGTTCTGTTAATTCATCTC-3′ - Reverse Primer:

5′-AAATATCCCTTTGCCAATTCCA-3′ - Probe:

5′-CCTTCAAGAAGCCTTTCGCTAAG-3′(FAM-labeled)

- Forward Primer:

Step 2: Reaction Setup

- Prepare a master mix containing buffer, enzymes, dNTPs, primers, and probe.

- Use a total reaction volume of 30 µL, adding 10 µL of DNA standard or sample.

- Critical: Use low-binding tubes and dedicated, nuclease-free pipettes to prevent adsorption and contamination.

Step 3: Thermal Cycling

- Perform amplification on a real-time PCR instrument with the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes.

- 40 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute.

- Perform amplification on a real-time PCR instrument with the following program:

Step 4: Validation and Data Analysis

- Linearity and Range: Run a standard curve with a 10-fold dilution series of known DNA standards (e.g., from 0.3 fg/µL to 30 pg/µL). The assay should demonstrate a linear response across the intended range [19].

- Limit of Detection (LoD) & Quantification (LoQ): Determine LoD and LoQ using standard statistical methods. The described Vero DNA assay achieved an LoD of 0.003 pg/reaction and an LoQ of 0.03 pg/reaction [19].

- Precision: Assess repeatability by testing multiple replicates across different runs. The coefficient of variation (CV) should be within acceptable limits (e.g., 12.4%-18.3%) [19].

Protocol for Validating RNA-Seq Workflows Against qPCR

This protocol is based on benchmarking studies that compare different RNA-Seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data [16].

Step 1: Sample Selection and RNA Preparation

- Use well-characterized RNA reference samples (e.g., MAQCA and MAQCB from the MAQC consortium) [16].

- Isolve high-quality total RNA using a method that preserves RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0). Treat samples with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

Step 2: Data Generation

- qPCR Data: Perform whole-transcriptome qPCR for all protein-coding genes. Use multiple technical replicates to ensure precision [16] [18].

- RNA-Seq Data: Sequence the same RNA samples. Include biological and technical replicates. Process the data through multiple common workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) for comparison [16].

Step 3: Data Alignment and Normalization

- Align qPCR assays to the transcripts detected in the RNA-seq data to ensure comparability [16].

- For RNA-Seq, filter genes based on a minimal expression level (e.g., 0.1 TPM in all replicates) to avoid bias from low-expressed genes.

- Convert gene-level counts to TPM for correlation analysis with qPCR Cq values [16].

Step 4: Correlation and Discrepancy Analysis

- Expression Correlation: Calculate Pearson correlation between log-transformed RNA-Seq TPM values and normalized qPCR Cq values for each workflow [16].

- Fold-Change Correlation: Calculate gene expression fold changes between sample groups (e.g., MAQCA vs. MAQCB) and correlate these between RNA-Seq and qPCR [16].

- Identify Non-Concordant Genes: Classify genes based on their differential expression status between the two methods. Investigate the characteristics (e.g., expression level, gene length, exon count) of genes where the methods disagree [16].

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for qPCR and RNA-Seq, highlighting steps that critically influence their sensitivity and detection limits.

High-Sensitivity qPCR Assay Workflow

RNA-Seq Dynamic Range and Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sensitive Nucleic Acid Detection

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Assay Reagents | Pre-designed primer/probe sets, master mix containing polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer. | Targeted quantification of specific genes or contaminants (e.g., residual host cell DNA) [19]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Reagents that immediately stabilize RNA at the point of sample collection to preserve integrity. | Critical for obtaining high RIN scores, ensuring accurate representation of the transcriptome. |

| Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kits | Kits for converting RNA into sequencing libraries, preserving strand-of-origin information. | Standard for bulk RNA-Seq; improves transcript annotation and detects antisense expression [21]. |

| Ultra-Low Input RNA Library Kits | Specialized kits using proprietary amplification (e.g., THOR technology) for minimal RNA input. | Enables RNA-Seq from single cells or rare samples by improving mRNA capture efficiency [22]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to tag individual RNA molecules before amplification. | Corrects for PCR amplification bias, improving quantification accuracy in both RNA-Seq and qPCR [22]. |

The accurate quantification of low-abundance genes is a critical challenge in molecular biology with profound implications for understanding immune regulation, cancer progression, and autoimmune diseases. This whitepaper examines the technical considerations of RNA-Seq versus qPCR methodologies for measuring lowly expressed genes, focusing on their application to key immunoregulatory molecules. We explore how precise measurement of low-expression genes, particularly in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and immune checkpoint pathways, provides crucial insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic development. The content is framed within a broader thesis on methodological comparisons, providing researchers with actionable protocols, analytical frameworks, and practical tools for advancing research in immuno-genomics.

Gene expression profiling represents a fundamental tool for elucidating biological processes in health and disease. While highly expressed genes often dominate transcriptomic analyses, low-abundance transcripts frequently encode critical regulatory proteins with disproportionate biological impact. This is particularly evident in immunology, where precisely controlled expression of antigen presentation machinery, immune checkpoints, and regulatory molecules determines the balance between effective immunity and pathological autoimmunity [23] [24].

The technical challenges associated with accurately quantifying low-expression genes necessitate rigorous methodological comparisons. Traditional qPCR has served as the gold standard for targeted gene expression analysis due to its sensitivity and reproducibility. However, the emergence of high-throughput RNA-Seq offers comprehensive transcriptome-wide profiling capabilities. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method is essential for researchers investigating the subtle gene expression changes that underlie immune dysregulation in cancer and autoimmune conditions [2].

Biological Significance of Lowly Expressed Genes

MHC Class I Expression in Immune Surveillance and Evasion

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules play an indispensable role in cellular immunity by presenting intracellular peptides to CD8+ T cells. Despite their critical function, these genes often demonstrate modest expression levels that are precisely regulated. Downregulation of MHC class I represents a common immune evasion mechanism across multiple cancer types, enabling tumors to escape CD8+ T cell-mediated destruction [24].

Table 1: Mechanisms of Low MHC I Expression in Cancer and Functional Consequences

| Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Alterations | Gene deletion, loss-of-function mutations | Complete absence of antigen presentation machinery |

| Transcriptional Inhibition | Epigenetic silencing, transcription factor dysregulation | Reduced mRNA synthesis |

| Post-transcriptional Regulation | Reduced mRNA stability, microRNA targeting | Altered transcript abundance despite normal transcription |

| Protein Degradation | Enhanced ubiquitin-proteasome pathway activity | Reduced cell surface presentation despite adequate mRNA |

| Defective Trafficking | Disruption of endocytic recycling | Impaired antigen loading and surface expression |

The biological significance of MHC expression extends beyond absolute levels to include allele-specific variation. For instance, higher HLA-C expression associates with better control of HIV-1, while elevated HLA-A expression impairs HIV control [2]. These nuanced relationships highlight the importance of precise, allele-specific quantification methods that can resolve subtle expression differences with potentially opposing functional consequences.

Immune Checkpoint Regulation in Autoimmunity and Cancer

Immune checkpoint receptors and ligands represent another class of immunologically critical genes that often exhibit low to moderate expression levels under physiological conditions. These molecules, including PD-1, CTLA-4, and others, maintain self-tolerance by modulating T cell activation thresholds. In autoimmunity, insufficient checkpoint expression may contribute to loss of tolerance, while in cancer, excessive checkpoint expression in the tumor microenvironment facilitates immune evasion [23] [25].

Therapeutic manipulation of immune checkpoints through antibody-mediated blockade has revolutionized cancer treatment. However, response variability remains substantial, partly due to differences in baseline and induced expression of checkpoint genes. Similarly, in autoimmune diseases, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) that modify checkpoint gene expression may influence disease susceptibility and progression [23].

Regulatory T Cell Function and Low-Abundance Transcripts

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) characterized by expression of the transcription factor FOXP3 maintain immune tolerance through multiple mechanisms. The FOXP3 gene itself is typically expressed at moderate levels, and its precise regulation is essential for immune homeostasis. Germline or transient deletion of FOXP3+ Tregs unleashes fatal multiorgan autoimmunity in mice, while humans with FOXP3 mutations develop IPEX syndrome [23].

Treg cells harbor a TCR repertoire skewed toward self-antigen recognition that overlaps substantially with autoreactive conventional CD4+ T cells. The functional specialization of these cells depends on the precise expression of key regulatory genes, many of which are low-abundance transcripts that present quantification challenges [23].

Technical Considerations for Quantifying Low-Abundance Genes

Methodological Comparison: qPCR versus RNA-Seq

The accurate quantification of low-expression genes presents distinct technical challenges that differ significantly between qPCR and RNA-Seq approaches. Understanding these methodological differences is essential for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation in immunology research.

Table 2: Comparison of qPCR and RNA-Seq for Low-Abundance Gene Quantification

| Parameter | qPCR | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (can detect single copies) | Variable (depends on sequencing depth) |

| Dynamic Range | ~7-8 logs | ~5 logs for standard depths |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low (typically 1-6 targets per reaction) | High (entire transcriptome) |

| Normalization Requirements | Critical, requires stable reference genes | Less dependent on single reference genes |

| Allele-Specific Resolution | Requires specialized assay design | Possible with appropriate bioinformatics |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate to high | Lower for standard workflows |

| Cost Per Sample | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Technical Variability | Low (when optimized) | Moderate to high |

Normalization Strategies for Low-Abundance Targets

Normalization represents a particularly critical consideration when quantifying low-expression genes, as technical variability can disproportionately affect measurements. For qPCR, the use of multiple reference genes with demonstrated stability across experimental conditions is essential. Recent evidence suggests that combinations of non-stable genes may outperform traditional "housekeeping" genes when carefully selected [15].

For RNA-Seq, normalization approaches include DESeq2's median-of-ratios method, TPM (transcripts per million), and others that minimize the impact of technical artifacts such as GC content, transcript length, and library size. These methods generally show better performance for low-abundance genes compared to simple normalization approaches [26].

Correlation Between Methodologies

Direct comparisons between qPCR and RNA-Seq for immunologically relevant genes reveal moderate correlations that vary by target. In studies comparing HLA class I expression quantification, correlations between qPCR and RNA-Seq ranged from 0.2 to 0.53 for HLA-A, -B, and -C [2]. These findings highlight the challenges in comparing absolute expression values across platforms and the importance of platform-specific validation.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflows for Gene Expression Quantification

Detailed Experimental Protocols

qPCR Protocol for Low-Abundance Immune Genes

Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

- Starting Material: 10-200 ng of high-quality RNA extracted using RNeasy or AllPrep DNA/RNA kits (Qiagen)

- RNA Quality Assessment: Qubit 2.0 for quantification, NanoDrop for purity (A260/280 ~2.0), TapeStation 4200 for RIN >7.0

- DNAse Treatment: Mandatory to remove genomic DNA contamination using RNAse-free DNAse

cDNA Synthesis

- Reverse Transcription: Use random hexamers and oligo-dT primers for comprehensive coverage

- Reaction Conditions: 25°C for 10 minutes, 37°C for 120 minutes, 85°C for 5 minutes

- Enzyme Selection: High-efficiency reverse transcriptase with RNase inhibitor

qPCR Reaction Setup

- Reaction Volume: 10-20 µl containing 1-10 ng cDNA equivalent

- Chemistry: SYBR Green or TaqMan probes depending on specificity requirements

- Primer Design: Amplicons of 70-150 bp spanning exon-exon junctions

- Validation: Efficiency curves (90-110%) with R² >0.98 for each assay

Data Analysis

- Quality Control: Melting curve analysis for SYBR Green, amplification efficiency validation

- Normalization: Minimum of three reference genes selected by stability algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder)

- Statistical Analysis: ΔΔCt method for relative quantification with technical replicates

RNA-Seq Protocol for Comprehensive Immune Profiling

Library Preparation

- RNA Input: 10-200 ng total RNA (quality and quantity similar to qPCR requirements)

- Library Kit: TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina) for FF samples; SureSelect XTHS2 for FFPE

- Capture Method: Whole exome capture using SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR (Agilent)

Sequencing and Quality Control

- Platform: NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina)

- Depth: Minimum 30 million reads per sample, 50+ million recommended for low-abundance targets

- Quality Metrics: Q30 >90%, PF >80%, assessment via FastQC and FastqScreen

Bioinformatic Processing

- Alignment: STAR aligner v2.4.2 against hg38 reference genome

- Deduplication: UMI-based deduplication with umitools for accurate quantification

- Quantification: Kallisto v0.44.0 with Ensembl GRCH37 reference transcriptome

- Batch Correction: ComBat or similar methods for technical batch effect correction

Special Considerations for HLA Genes

- Reference Selection: Use customized references incorporating HLA allele diversity

- Alignment Parameters: Adjust to accommodate high polymorphism regions

- Expression Estimation: HLA-tailored pipelines (e.g., OptiType, HLA-HD) for allele-specific quantification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Abundance Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit, AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit | Maintain RNA integrity, especially from challenging samples like FFPE |

| Reverse Transcriptases | High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Ensure efficient cDNA synthesis from low-input RNA |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix | Provide sensitive, specific detection with minimal background |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep | TruSeq Stranded mRNA, SureSelect XTHS2 RNA | Preserve strand information, efficient library construction from low-quality RNA |

| Target Enrichment | SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR | Comprehensive coverage of coding transcriptome including immune genes |

| Reference Materials | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Monitor technical variability, validate assay sensitivity |

| Quality Control Tools | Qubit RNA HS Assay, TapeStation High Sensitivity RNA ScreenTape | Accurate quantification and integrity assessment of limited samples |

| Bioinformatic Tools | STAR aligner, Kallisto, DESeq2, HLA-HD | Specialized analysis of immune genes, allele-specific expression |

Signaling Pathways Linking Low Expression to Disease Phenotypes

Diagram Title: Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in Cancer

The precise quantification of low-abundance genes encoding immunologically critical molecules represents both a technical challenge and a scientific opportunity. As methodologies continue to evolve, the research community must maintain rigorous standards for assay validation, normalization, and data interpretation. The complementary strengths of qPCR and RNA-Seq suggest that a hybrid approach—using RNA-Seq for discovery and qPCR for targeted validation—may offer the most robust framework for investigating the biological significance of low-expression genes in immune regulation.

Future methodological developments, including single-cell sequencing, digital PCR, and emerging third-generation sequencing technologies, promise to enhance our ability to resolve subtle expression differences in biologically critical low-abundance transcripts. These technical advances, coupled with improved bioinformatic tools for allele-specific and isoform-aware quantification, will deepen our understanding of how precise gene expression control shapes immune responses in health and disease.

Methodologies in Practice: Protocols for qPCR and RNA-Seq on Low-Abundance Targets

In the context of gene expression analysis, the accurate quantification of low-abundance transcripts presents a significant technical challenge. While next-generation sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a comprehensive, hypothesis-free view of the transcriptome, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for sensitive, specific, and cost-effective validation and targeted quantification of gene expression [27]. The reliability of qPCR data, especially for low-copy-number RNAs, is heavily dependent on rigorous experimental design, execution, and analysis. This guide details the core best practices for qPCR, framed within a modern research workflow that often uses RNA-Seq for discovery and qPCR for confirmation, with a particular emphasis on achieving rigor and reproducibility in quantifying challenging targets.

Assay Design for Specificity and Sensitivity

The foundation of a successful qPCR experiment is a well-designed assay. For low-abundance transcripts, maximizing sensitivity and specificity is paramount to distinguish a true signal from background noise.

Design Principles: Assays should be designed to be 70-200 base pairs in length to ensure efficient amplification [28]. Primers must be specific, ideally spanning an exon-exon junction to avoid amplification of genomic DNA contamination. The use of in silico tools like Primer-BLAST is recommended to verify specificity, and this should be confirmed empirically by sequencing the PCR product and checking for a single peak in the melting curve analysis [28].

Variant-Specific Quantification: When quantifying specific splice variants or isoforms, careful assay design is critical. Researchers should identify the NCBI RefSeq transcript accession number of the specific variant and use this to search for a predesigned assay that detects only that variant. If none are available, a custom assay must be designed to target the unique exon-exon boundary of the isoform [27].

Advanced Methods for Low-Abundance Targets: Conventional RT-qPCR often has limited sensitivity, with quantification cycle (Cq) values above 30-35 being considered unreliable [12]. To overcome this, novel methods like STALARD (Selective Target Amplification for Low-Abundance RNA Detection) have been developed. This two-step RT-PCR method uses a gene-specific primer tailed with an oligo(dT) sequence for reverse transcription, followed by a limited-cycle PCR using only the gene-specific primer. This selectively amplifies polyadenylated transcripts sharing a known 5'-end sequence, dramatically improving the detection and reliable quantification of low-abundance isoforms [12].

The following diagram illustrates the STALARD workflow for enhancing detection of low-abundance RNAs.

The MIQE Guidelines 2.0: Ensuring Reproducibility

The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines establish a standardized framework to ensure the transparency, reproducibility, and reliability of qPCR data. A updated version, MIQE 2.0, has been released to reflect advances in technology and the complexities of contemporary qPCR applications [29].

Core Philosophy: The fundamental principle is that a transparent, clear, and comprehensive description of all experimental details is necessary to ensure the repeatability and reproducibility of qPCR results. This allows other scientists to critically evaluate and replicate the work [29].

Key Reporting Requirements: MIQE 2.0 offers clarified and streamlined reporting requirements. Crucially, researchers are encouraged to export and provide raw fluorescence data to enable independent re-analysis [29] [30]. The guidelines emphasize that quantification cycle (Cq) values must be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities and should be reported with prediction intervals, not just as mean values [29]. Furthermore, the detection limit and dynamic range for each assay must be stated.

Assay Information Disclosure: For assay design, the guidelines require detailed disclosure. When using commercial assays like TaqMan, providing the unique Assay ID is typically sufficient, as this permanently links to a specific oligo sequence. For full compliance, the amplicon context sequence (the full PCR amplicon) can be provided, which is available in the Assay Information File or can be generated using the supplier's online tools [31].

Robust Normalization Strategies

Normalization is a critical step to control for technical variability introduced during sample processing, and the choice of strategy can dramatically impact data interpretation, particularly for subtle expression changes.

Reference Gene (RG) Normalization

This is the most common method, but it requires careful validation.

Gene Selection and Validation: The classical "housekeeping" genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) are not universally stable and their expression can vary with experimental conditions and pathologies [32]. Therefore, RGs must be validated for the specific sample type and condition under investigation. Algorithms like geNorm and NormFinder are used to rank candidate RGs based on their expression stability across all samples [32] [28]. The MIQE guidelines recommend using at least two validated reference genes [28].

Stability in Canine Models: A 2025 study on canine gastrointestinal tissues highlighted that the most stable RGs were RPS5, RPL8, and HMBS. The study also noted that ribosomal protein genes (RPS5, RPL8) tend to be co-regulated, so using RGs from different functional classes is advisable [32].

Alternative Normalization Methods

For larger profiling studies, other methods can be more robust.

Global Mean (GM) Normalization: This method uses the geometric mean of the expression of a large set of genes (e.g., >55) as the normalization factor. In the canine study, the GM method was the best-performing strategy for reducing technical variability across tissues and disease states when a large set of genes was profiled [32].

Algorithm-Only Approaches: Methods like NORMA-Gene provide a normalization factor calculated via least squares regression using the expression data of at least five genes, without the need for predefined RGs. A 2025 study in sheep showed that NORMA-Gene was better at reducing variance in target gene expression than using traditional reference genes and requires fewer resources [28].

The table below summarizes and compares these key normalization methods.

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR Normalization Strategies

| Method | Principle | When to Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genes (RG) | Normalizes to the geometric mean of 2+ validated, stably expressed endogenous genes. | Targeted gene expression studies with a small number of targets. | Well-established; MIQE-recommended; cost-effective for few targets. | Requires extensive validation; no universally stable RGs; potential for co-regulation. |

| Global Mean (GM) | Normalizes to the geometric mean of all expressed genes in the assay. | High-throughput studies profiling tens to hundreds of genes. | Highly robust; no need for RG validation; outperforms RG in some complex designs [32]. | Requires a large number of genes (>55) for reliability [32]. |

| NORMA-Gene | Algorithm calculates a normalization factor from all provided gene expression data. | Studies with at least 5 target genes; limited resources for RG validation. | Reduces variance effectively; no prior RG validation needed [28]. | Less familiar to some researchers; requires a minimum number of genes. |

Data Analysis and Adherence to FAIR Principles

Moving beyond the traditional 2−ΔΔCT method is key to improving statistical rigor and reproducibility.

Beyond 2−ΔΔCT: The widespread reliance on the 2−ΔΔCT method often overlooks variability in amplification efficiency, which can introduce significant bias. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) is a flexible multivariable linear modeling approach that offers greater statistical power and robustness, as its P-values are not affected by variations in qPCR amplification efficiency [30].

Promoting Reproducibility with FAIR Data: To facilitate rigor, researchers are encouraged to share raw qPCR fluorescence data alongside detailed analysis scripts that take the raw data through to the final figures and statistical tests. Using general-purpose data repositories (e.g., figshare) and code repositories (e.g., GitHub) promotes transparency and allows others to verify and build upon the findings [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for qPCR Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Predesigned, optimized probe-based assays for specific gene targets. | Gold-standard for target quantification and verification of RNA-Seq results [27]. |

| TaqMan Array Cards | 384-well microfluidic cards pre-spotted with assays for high-throughput profiling. | Profiling a focused panel of targets (12-384 genes) with minimal reagent use and a streamlined workflow [27]. |

| HiScript IV 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | High-efficiency reverse transcriptase for converting RNA to cDNA. | First-strand cDNA synthesis in the STALARD method and conventional RT-qPCR [12]. |

| SeqAmp DNA Polymerase | PCR enzyme used in pre-amplification protocols. | Limited-cycle, target-specific pre-amplification in the STALARD method [12]. |

| Oligo(dT) Primers & Gene-Specific Primers (GSP) | Primers for cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification. | Reverse transcription of polyadenylated RNA and specific amplification of target cDNA. |

qPCR and RNA-Seq: A Complementary Workflow

The choice between qPCR and RNA-Seq is not a binary one; they are highly complementary technologies.

Defining the Roles: RNA-Seq is ideal for discovery-based research, such as detecting novel transcripts, identifying differentially expressed genes without prior knowledge, and analyzing transcript isoform diversity [27]. qPCR is the preferred method for targeted, high-precision quantification, verification of RNA-Seq results, and follow-up studies on a defined panel of genes [27].

Integrated Workflow: In a robust experimental pipeline, qPCR is used both upstream and downstream of RNA-Seq. Upstream, qPCR can check cDNA library quality and integrity before costly sequencing [27]. Downstream, qPCR is the gold-standard method for validating key findings from the RNA-Seq dataset [27] [32]. This combined approach ensures data integrity from start to finish.

The following chart summarizes this complementary relationship and the standard workflow for low-abundance transcript analysis.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with finer resolution, improved accuracy, and lower background noise compared to earlier methods like microarrays [33]. For researchers investigating low-abundance genes—a critical challenge in fields from Mendelian disease diagnostics to drug mechanism discovery—thoughtful experimental design is paramount. The choice between library preparation methods, sequencing depth, and coverage parameters directly determines an experiment's power to detect and quantify rare transcripts accurately. This guide provides a detailed framework for optimizing these key decisions, with a specific focus on challenges relevant to researchers comparing RNA-Seq to qPCR for low-abundance targets, where conventional RT-qPCR often reaches its sensitivity limits with quantification cycle (Cq) values above 30-35 considered unreliable [12].

Library Preparation Strategies: Poly-A Selection vs. Ribosomal RNA Depletion

The initial library preparation method fundamentally defines the transcriptome you will measure, influencing which RNA species are captured and how effectively sequencing reads are utilized [34].

Poly-A Enrichment: Targeted Capture of Mature mRNA

Mechanism: Poly(A) enrichment uses oligo(dT) primers attached to magnetic beads to capture RNA molecules containing poly(A) tails, primarily enriching for mature messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and many polyadenylated long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [34] [35].

Key Advantages:

- High Exonic Read Yield: Delivers 70-71% usable exonic reads, dramatically focusing sequencing power on protein-coding regions [35].

- Cost Efficiency for mRNA Studies: Requires fewer total reads to achieve sufficient exonic coverage—approximately 13.5 million poly(A)-selected reads can detect as many genes as a typical microarray, compared to 35–65 million reads with ribodepletion methods [35] [36].

- Reduced Background: Effectively removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and other non-informative RNA classes without requiring species-specific probes [37] [38].

Critical Limitations:

- Incompatibility with Degraded Samples: Heavily relies on intact poly(A) tails, making it suboptimal for degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE samples) where it produces strong 3' bias [34] [35].

- Exclusion of Non-polyadenylated Transcripts: Completely misses important RNA species including replication-dependent histone mRNAs, many non-coding RNAs, and bacterial transcripts [34].

- Potential Capture Bias: May preferentially capture mRNAs with longer poly(A) tails, potentially misrepresenting transcript abundances [35].

Ribosomal RNA Depletion: Comprehensive Transcriptome Capture

Mechanism: rRNA depletion uses sequence-specific DNA probes that hybridize to cytosolic and mitochondrial rRNAs, which are then removed via RNase H digestion or affinity capture, preserving both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs [34] [38].

Key Advantages:

- Broad Transcriptome Coverage: Captures diverse RNA types including pre-mRNA, lncRNAs, snoRNAs, and non-polyadenylated transcripts [35].

- Compatibility with Challenging Samples: Performs robustly with degraded, fragmented, or FFPE RNA where poly(A) tails may be compromised [34] [35].

- Uniform Coverage: Provides more even 5'-to-3' coverage across transcripts, valuable for splicing and isoform analysis [35].

Critical Limitations:

- Lower Efficiency for mRNA Studies: Yields significantly fewer exonic reads (22-46%), requiring 50-220% more sequencing to achieve equivalent exonic coverage compared to poly(A) selection [35].

- Species-Specific Probes: Requires matched depletion probes for different organisms; incomplete rRNA removal leads to wasted sequencing capacity [34] [35].

- Increased Bioinformatics Complexity: Higher proportions of intronic and intergenic reads increase data volume and analytical demands [35].

Decision Framework: Choosing the Optimal Method

Table 1: Method Selection Guide Based on Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Recommended Method | Rationale | Sequencing Depth Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality eukaryotic RNA (RIN ≥8) | Poly-A selection | Maximizes exonic read yield and cost-efficiency for mRNA studies | Standard depth (20-60 million reads) typically sufficient |

| Degraded/FFPE samples | rRNA depletion | Does not rely on intact poly(A) tails; more resilient to fragmentation | May require 50-100% additional reads for equivalent exon coverage |

| Non-coding RNA discovery | rRNA depletion | Captures both polyA+ and non-polyA transcripts (lncRNAs, snoRNAs, etc.) | 30-100% more reads than poly-A studies due to diverse transcript types |

| Prokaryotic transcriptomics | rRNA depletion | Bacterial mRNAs lack poly(A) tails; poly-A capture is ineffective | Varies by species and depletion efficiency |

| Low-abundance mRNA quantification | Poly-A selection | Concentrates sequencing power on target molecules | May require elevated depth (>100 million reads) for rare transcripts |

| Alternative splicing analysis | rRNA depletion (paired-end) | Provides more uniform transcript coverage for isoform resolution | Higher depth (60-150 million reads) improves splice junction detection |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Tissue Types (Based on Zhao et al. Data) [35]

| Performance Metric | Blood Tissue | Colon Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-A Exonic Reads | 71% | 70% |

| rRNA Depletion Exonic Reads | 22% | 46% |

| Extra Reads Needed with Depletion | +220% | +50% |

Sequencing Depth and Coverage: Optimizing for Low-Abundance Transcripts

Depth Requirements for Different Research Applications

Sequencing depth—typically defined as the total number of mapped reads rather than average base coverage—must be matched to experimental goals [39].

Table 3: Recommended Sequencing Depth by Research Application [37]

| Research Goal | Recommended Reads | Low-Abundance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gene expression profiling | 5-25 million | May miss low-expression genes; suitable only for highly expressed targets |

| Standard differential expression | 30-60 million | Detects moderately expressed genes; minimum for publication-quality DGE |

| Alternative splicing analysis | 60-100 million | Improves splice junction coverage; enables isoform quantification |

| Transcriptome assembly | 100-200 million | Captures more transcript diversity; improves novel isoform discovery |

| Low-abundance & rare transcript detection | 200 million - 1 billion | Essential for comprehensive capture of rare splicing events and low-expression genes |

Ultra-Deep Sequencing for Critical Applications

For diagnostic applications and challenging detection scenarios, ultra-deep sequencing provides remarkable benefits. Recent research demonstrates that while standard depths (50-150 million reads) miss critical information, increasing depth to 200 million reads reveals pathogenic splicing abnormalities invisible at lower depths, with further improvements up to 1 billion reads [39]. This ultra-deep approach achieves near-saturation for gene detection, though isoform detection continues to benefit from additional depth [39].

The relationship between sequencing depth and low-abundance transcript detection follows a logarithmic pattern—initial depth increases capture abundant transcripts efficiently, while progressively deeper sequencing is required for increasingly rare transcripts. For Mendelian disorder diagnostics, this means that variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) with subtle splicing effects may only be detectable at depths exceeding 200 million reads [39].

Experimental Protocols for Low-Abundance Transcript Detection

Standard RNA-Seq Workflow for Low-Abundance Targets

For comprehensive transcriptome analysis with sensitivity to low-abundance transcripts, the following protocol is recommended:

Sample Preparation:

- Input Material: 100ng - 1μg total RNA (quality-dependent)

- RNA Integrity: RIN ≥8 for poly-A selection; RIN ≥5 for rRNA depletion

- Replicates: Minimum 3 biological replicates per condition; increased replicates improve power more than excessive depth when biological variability is high [33]

Library Preparation (rRNA Depletion for Maximum Sensitivity):

- rRNA Removal: Use species-matched ribodepletion probes (e.g., RiboCop) [38]

- Library Construction: Fragment RNA, synthesize cDNA with random primers

- Adapter Ligation: Use unique dual indexing to enable sample multiplexing

- Quality Control: Verify library size distribution and concentration

Sequencing Parameters:

- Depth: 100-200 million reads per sample for low-abundance targets [37]

- Read Type: Paired-end (2×100 bp or 2×150 bp) for improved mapping and isoform resolution [37]

- Platform: Illumina for standard applications; Ultima for cost-effective ultra-deep sequencing [39]

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: FastQC/multiQC for quality metrics [33]

- Adapter Trimming: Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [33]

- Alignment: STAR or HISAT2 to reference genome [33]

- Quantification: featureCounts or HTSeq-count for gene-level analysis; Salmon or Kallisto for transcript-level analysis [33]

- Normalization: DESeq2's median-of-ratios or edgeR's TMM for differential expression [33]

Targeted Methods for Extreme Low-Abundance Challenges

When conventional RNA-Seq remains insufficient for extremely rare transcripts, specialized targeted approaches offer alternatives:

STALARD (Selective Target Amplification for Low-Abundance RNA Detection): This two-step RT-PCR method selectively amplifies polyadenylated transcripts sharing a known 5'-end sequence before quantification, dramatically improving sensitivity for predefined targets [12].

Workflow:

- Reverse Transcription: Use gene-specific oligo(dT) primer to incorporate adapter sequence

- Limited-Cycle PCR: 9-18 cycles with gene-specific primer only

- Quantification: Standard qPCR or sequencing analysis

Advantages:

- Overcomes sensitivity limitations of conventional RT-qPCR (Cq >30)

- Avoids amplification biases from different primer efficiencies

- Compatible with both qPCR and long-read sequencing validation [12]

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RiboCop rRNA Depletion | Bead-based removal of rRNA | Preserves expression profiles; 1.5-hour protocol; compatible with various library preps [38] |

| Poly(A) RNA Selection Kit | Oligo(dT) bead-based mRNA enrichment | High stringency; part of CORALL mRNA-Seq bundle; efficient cytoplasmic rRNA removal [38] |

| CORALL Total RNA-Seq | Whole transcriptome library prep | Works with both poly-A selection and ribodepletion; enables full transcriptome analysis [40] |

| QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq | 3'-end focused library prep | Streamlined workflow; 1-5 million reads/sample; ideal for degraded/FFPE samples [40] |

| STALARD Reagents | Targeted pre-amplification | Standard lab reagents; SeqAmp DNA polymerase; gene-specific primers for low-abundance targets [12] |

| HiScript IV cDNA Synthesis Kit | High-efficiency reverse transcription | Used for first-strand cDNA synthesis in standard and specialized protocols [12] |

Workflow Visualization and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for designing an RNA-Seq experiment optimized for low-abundance transcript detection:

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq Experimental Design Decision Pathway

Optimizing RNA-Seq workflows for low-abundance gene quantification requires careful balancing of library preparation methods, sequencing depth, and application-specific considerations. Poly-A selection provides the most cost-effective approach for high-quality samples targeting protein-coding genes, while ribosomal RNA depletion offers broader transcriptome coverage and compatibility with challenging sample types. For rare transcript detection, ultra-deep sequencing (200 million to 1 billion reads) reveals biological signals inaccessible at standard depths, though targeted methods like STALARD provide alternatives for predefined targets. By matching these strategic decisions to specific research goals and sample constraints, researchers can maximize their potential to uncover meaningful biological insights in the challenging realm of low-abundance transcription.

The accurate quantification of gene expression, particularly for low-abundance transcripts, is a fundamental challenge in molecular biology research, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and drug development. Traditional methods like quantitative PCR (qPCR) face limitations in sensitivity and scalability, especially when targeting rare RNA species [2] [12]. Low-abundance transcripts, often characterized by quantification cycle (Cq) values above 30-35, are notoriously difficult to measure reliably with conventional RT-qPCR due to poor reproducibility at these levels [12]. Furthermore, studying alternative splicing isoforms or non-coding RNAs adds another layer of complexity, as isoform-specific qPCR is often confounded by differential primer efficiency when comparing similar transcripts [12].

The emergence of Targeted RNA Sequencing (Targeted RNA-Seq) and novel enrichment techniques represents a paradigm shift in low-abundance RNA detection. These methods bridge the gap between the highly focused but limited qPCR and the comprehensive but resource-intensive whole transcriptome sequencing. Targeted RNA-Seq enables researchers to deeply sequence specific transcripts of interest, providing both quantitative and qualitative information with enhanced sensitivity [41]. By concentrating sequencing power on predefined genes, these approaches achieve a higher sequencing depth for the targets of interest, making them particularly suited for detecting and quantifying rare transcripts that might be missed in broader transcriptomic surveys [41] [42]. This technical guide explores the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and research applications of these advanced techniques within the context of low-abundance gene quantification, providing researchers with the framework to select and implement optimal strategies for their specific investigative needs.

Core Technologies and Principles

Targeted RNA Sequencing (Targeted RNA-Seq)