Machine Learning for Cancer Classification: A Comparative Review of Algorithms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms for cancer classification, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning for Cancer Classification: A Comparative Review of Algorithms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms for cancer classification, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles driving the adoption of AI in oncology, detail a wide array of methodological approaches from ensemble systems to multiomics integration, and address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges such as high-dimensional data and model interpretability. The scope culminates in a rigorous validation and comparative analysis of algorithm performance, synthesizing current evidence to guide model selection and benchmark future innovations in precision medicine.

The Rise of AI in Oncology: Core Concepts and Data Types for Cancer Classification

Cancer remains one of the foremost causes of mortality worldwide, with early and accurate diagnosis being a critical determinant of patient outcomes [1]. The complex, multidimensional nature of cancer data—spanning genomics, transcriptomics, imaging, and clinical records—presents analytical challenges that transcend the capabilities of traditional statistical methods. Machine learning (ML), particularly its subset deep learning (DL), is emerging as a transformative force in cancer diagnostics by detecting subtle patterns within large, heterogeneous datasets that often elude human perception [2] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of ML algorithms used in cancer classification, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and the essential tools driving this diagnostic revolution.

Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms in Cancer Diagnostics

The selection of an appropriate ML algorithm is pivotal to the success of a diagnostic model. Performance varies significantly based on the cancer type, data modality, and specific diagnostic task. The following table synthesizes quantitative results from recent studies to facilitate comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Algorithm | Accuracy | AUC | Key Data Modality | Source (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers(5 common types in Saudi Arabia) | Stacking Ensemble (SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF) | 98% | N/R | Multiomics (RNA-seq, Methylation, Somatic Mutation) | [4] (2025) |

| Brain Tumor | Random Forest | 87% | N/R | MRI-based Radiomic Features | [5] (2025) |

| Brain Tumor | Simple CNN | 70% | N/R | MRI | [5] (2025) |

| Brain Tumor | VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50 | 47-66% | N/R | MRI | [5] (2025) |

| Skin Cancer | CNN | 92.5% | N/R | Dermoscopic Images | [6] (2025) |

| Skin Cancer | Vision Transformer (ViT) & EfficientNet Ensemble | 95.05% | N/R | Dermoscopic Images | [7] (2025) |

| Skin Cancer | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | <92.5% | N/R | Dermoscopic Images | [6] (2025) |

| Skin Cancer | Random Forest | <92.5% | N/R | Dermoscopic Images | [6] (2025) |

| Breast Cancer | SGA-RF (with feature selection) | 99.01% | N/R | Gene Expression | [8] (2025) |

| Breast Cancer | Random Forest (NK cell gene signature) | High (Best among 12 models) | High | Gene Expression (Transcriptomic) | [9] (2025) |

| Breast Cancer | Logistic Regression, SVM, KNN | <99.01% | N/R | Gene Expression | [8] (2025) |

| Microarray-based Cancer Classification | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | N/R | 0.787 | Gene Expression (Microarray) | [10] (2008) |

| Microarray-based Cancer Classification | Random Forest | N/R | 0.759 | Gene Expression (Microarray) | [10] (2008) |

Key Insights from Comparative Data:

- Ensemble Methods Dominate: Stacking multiple models or using sophisticated ensembles like ViT with CNNs consistently achieves top-tier performance (95-98% accuracy) by leveraging the strengths of individual algorithms [4] [7].

- Data Modality Dictates Optimal Algorithm: For complex image data (e.g., dermatology, radiology), deep learning models like CNNs and Vision Transformers excel [7] [6]. For structured, high-dimensional data like gene expression, tree-based ensembles like Random Forest can be superior, especially when paired with robust feature selection [5] [9] [8].

- The Random Forest Paradox: While Random Forest can outperform complex deep learning models in specific contexts (e.g., brain tumor classification from radiomic features) [5], it is generally outperformed by SVMs on microarray gene expression data [10] and by CNNs on raw image data [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

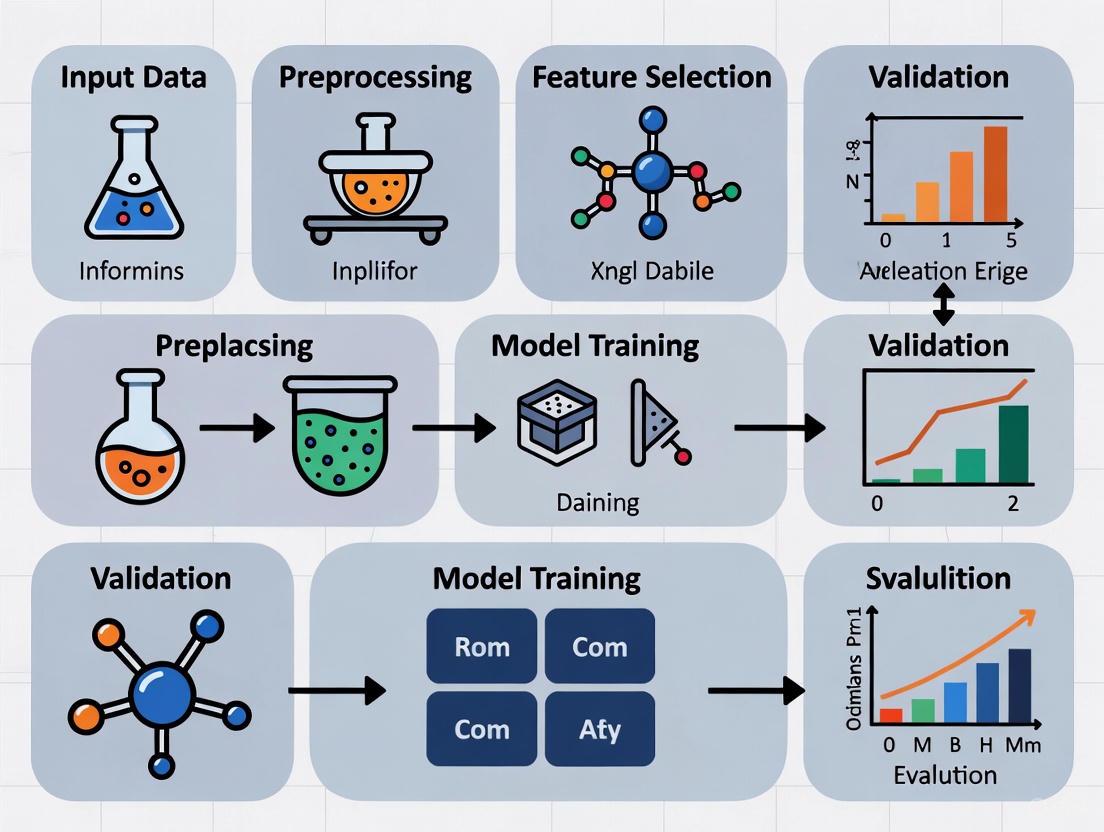

Understanding the experimental workflow is essential for evaluating and replicating ML diagnostics research. The following diagram and description outline a standard pipeline.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for developing machine learning models in cancer diagnostics.

Detailed Protocol Breakdown

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The first phase involves gathering and curating high-quality datasets, which form the foundation of any robust ML model.

- Data Sources: Publicly accessible repositories like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) are primary sources for genomic and transcriptomic data [4] [9]. For imaging, datasets such as BraTS (for brain tumors) and ISIC (for skin lesions) are widely used [7] [5].

- Preprocessing Steps:

- Genomic/Transcriptomic Data: Normalization is critical. For RNA sequencing data, methods like Transcripts Per Million (TPM) are used to eliminate technical variation and bias. The formula is:

TPM = (Reads Mapped to Transcript / Transcript Length) / (Sum of (Reads Mapped / Transcript Length)) * 10^6[4]. - Image Data: Preprocessing often involves resizing, noise reduction, and contrast enhancement techniques like Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) [5].

- Handling Data Imperfections: Addressing class imbalance is achieved through techniques like the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) or downsampling [4].

- Genomic/Transcriptomic Data: Normalization is critical. For RNA sequencing data, methods like Transcripts Per Million (TPM) are used to eliminate technical variation and bias. The formula is:

Feature Engineering and Selection

This step reduces data dimensionality and highlights the most informative variables.

- Feature Extraction: For image data, CNNs automatically learn relevant features [6]. For genomic data, autoencoders (a type of neural network) can be used to compress high-dimensional input into a lower-dimensional, meaningful representation [4].

- Feature Selection: Algorithms like the Boruta algorithm [9] or nature-inspired optimizers like the Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SGA) [8] systematically explore the feature space to identify the most informative genes or biomarkers, reducing overfitting and computational cost.

Model Training, Validation, and Evaluation

The core of the experimental protocol involves building and assessing the model.

- Training with Cross-Validation: Models are typically trained using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 10-fold) to ensure that performance is not dependent on a particular split of the data [9].

- Algorithm Selection: A diverse set of algorithms is often compared. These can range from traditional models like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests (RF) to advanced deep learning architectures like Vision Transformers (ViT) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [4] [7] [5].

- Performance Metrics: Models are evaluated based on a suite of metrics, including Accuracy, Area Under the Curve (AUC), Sensitivity, Specificity, and F1-Score [10] [9].

Successful development of ML diagnostics requires a suite of data, software, and computational tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Cancer Diagnostics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Provide large-scale, well-annotated genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data for model training and validation. Essential for developing molecular diagnostic models [4] [9]. |

| Medical Image Datasets | ISIC (Skin Cancer), BraTS (Brain Tumors) | Curated collections of medical images (dermoscopy, MRI) that serve as benchmarks for developing and testing image-based DL models [7] [5]. |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SGA), Boruta Algorithm | Identify the most predictive biomarkers from thousands of genes, improving model accuracy and interpretability while reducing complexity [9] [8]. |

| Ensemble & Advanced DL Models | Stacking Ensemble (SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF), Vision Transformer (ViT) | Combine the predictive power of multiple base models or use attention mechanisms to achieve state-of-the-art classification accuracy [4] [7]. |

| High-Performance Computing | Aziz Supercomputer, GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) | Provide the massive computational power required for training complex models, especially deep learning networks on large datasets [4] [1]. |

Advanced Architectures: Inside the Vision Transformer for Cancer Imaging

Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture has shown remarkable success in medical image analysis. The following diagram illustrates how its attention mechanism functions as a performance booster.

Figure 2: Vision Transformer workflow for multi-scale skin cancer analysis.

This innovative approach leverages the self-attention mechanism of Transformers to highlight diagnostically relevant regions in an image [7]. By generating attention maps, the model identifies and isolates critical areas, such as specific patterns within a skin lesion. These regions are then cropped and analyzed at a higher resolution alongside the original full image. This multi-scale analysis allows the model to capture both the broader context and fine-grained details, significantly boosting diagnostic accuracy. The final prediction is often made by an ensemble of different models (e.g., ViT and various EfficientNet versions) using a majority voting system, which enhances robustness and reliability [7].

The integration of machine learning into cancer diagnostics is no longer a speculative future but an active and transformative frontier. As the comparative data shows, there is no single "best" algorithm; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific clinical question, the nature of the available data, and the diagnostic task at hand. Ensemble methods and advanced deep learning architectures are pushing the boundaries of classification accuracy, enabling a level of precision that was previously unattainable. While challenges remain—including model interpretability, data standardization, and integration into clinical workflows—the continued development of sophisticated computational tools and expansive biological datasets promises to further solidify ML's role as an indispensable ally in the fight against cancer. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these tools and methodologies is becoming imperative to drive the next wave of innovations in precision oncology.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in biomedical research has revolutionized approaches to complex challenges, particularly in cancer classification. As high-throughput technologies generate vast amounts of molecular and clinical data, researchers require sophisticated computational methods to extract meaningful patterns. Three fundamental AI concepts—neural networks (NNs), deep learning (DL), and ensemble methods—form the cornerstone of modern computational biology approaches in oncology. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their performance in cancer type classification, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate algorithms for their specific biomedical applications.

Core Terminology and Definitions

Neural Networks (NNs)

Neural Networks are computational models inspired by the human brain's network of neurons. The smallest unit of a neural network is an artificial neuron (or perceptron), which receives input, processes it through a weighted sum plus a bias term, and passes the result through an activation function to determine output [11] [12]. These neurons are organized into interconnected layers: an input layer that accepts raw data, one or more hidden layers that transform the data, and an output layer that produces the final prediction [12] [13]. In biomedical contexts, NNs excel at identifying complex, non-linear relationships in diverse data types, from genomic sequences to histological images [11] [14].

Deep Learning (DL)

Deep Learning refers to neural networks with multiple hidden layers (making them "deep") that can automatically learn hierarchical representations of data [12]. Unlike traditional machine learning that requires manual feature engineering, DL models learn relevant features directly from raw data through training [13]. The "deep" architecture enables these models to capture increasingly abstract patterns—from simple edges in early layers to complex structures in later layers—making them particularly powerful for analyzing biomedical images, genomic sequences, and other complex biomedical data [12] [13]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), a specialized DL architecture, have revolutionized image analysis in biomedicine through their use of small kernels that scan across input data to detect spatially local patterns [12].

Ensemble Methods

Ensemble Methods combine multiple machine learning models (called "base learners" or "weak learners") to obtain better predictive performance than could be obtained from any constituent model alone [15]. The fundamental principle is that a collection of models working together can compensate for individual biases and errors, resulting in more robust and accurate predictions [15] [16]. These methods are particularly valuable in biomedical applications where data complexity, heterogeneity, and noise can challenge individual models. The three main ensemble paradigms are:

- Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): Trains multiple models in parallel on different random subsets of the training data and combines their predictions through voting or averaging [15] [16].

- Boosting: Trains models sequentially, with each new model focusing on correcting errors made by previous models [15] [16].

- Stacking: Combines predictions from multiple different types of models using a meta-model that learns how to best integrate their outputs [15] [4].

Experimental Protocols in Cancer Classification

Deep Learning Protocol: The GraphVar Framework

The GraphVar framework exemplifies a sophisticated DL approach for multicancer classification using somatic mutation data [17].

Data Preparation:

- Data Source: Somatic variant data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) encompassing 10,112 patient samples across 33 cancer types.

- Data Curation: Removal of duplicate patient entries followed by stratified partitioning into training (70%), validation (10%), and test sets (20%) to preserve proportional cancer type representation.

Multi-Representation Feature Engineering:

- Variant Map Construction: Genes harboring variants were organized into an N×N matrix based on genomic loci. Different variant types (SNPs, insertions, deletions) were encoded as different color channels (blue, green, red) with pixel intensities representing variant categories [17].

- Numeric Feature Extraction: A 36-dimensional feature matrix capturing population allele frequencies and six predefined somatic variant spectra was constructed for each sample.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Dual-Stream Network: Employed a ResNet-18 backbone (pretrained on ImageNet) to extract spatial features from variant images and a Transformer encoder to capture patterns in numeric features [17].

- Feature Fusion: Extracted features from both streams were concatenated into a comprehensive feature vector and passed to a fully connected classification head.

- Implementation: Python 3.10 with PyTorch 2.2.1; training leveraged cross-entropy loss with Adam optimizer and early stopping based on validation performance.

Ensemble Method Protocol: Performance-Weighted Voting

This ensemble approach demonstrates how combining multiple classifiers improves cancer type prediction [18].

Data Preparation:

- Data Source: TCGA somatic mutation data from 6,249 samples across 14 cancer types.

- Feature Engineering: Mutation count per gene served as input features for all classifiers.

Base Classifier Training:

- Model Selection: Five diverse classifiers were implemented: Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and Multilayer Perceptron Neural Networks (MLP-NN) [18].

- Cross-Validation: Each classifier underwent cross-validation to obtain predicted probabilities and assess individual performance.

Ensemble Construction:

- Weight Optimization: Classifier weights were determined based on predictive performance by solving linear regression functions, assigning higher weights to better-performing models [18].

- Weighted Voting: Final prediction probability was computed as the summation of each classifier's weight multiplied by its predicted probability.

- Comparison Models: Performance was compared against hard-voting (equal weights, majority vote) and soft-voting (equal weights, probability average) ensembles.

Stacked Deep Learning Ensemble for Multiomics Data

This protocol integrates multiple data types using a stacking ensemble architecture [4].

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Multiomics Data: RNA sequencing data from TCGA; somatic mutation and DNA methylation data from LinkedOmics.

- Normalization: RNA sequencing data normalized using transcripts per million (TPM) method to eliminate technical variation.

- Feature Extraction: Autoencoders with five dense layers (500 nodes each, ReLU activation, dropout 0.3) reduced dimensionality while preserving biological properties.

Ensemble Architecture:

- Base Models: Five diverse algorithms: Support Vector Machine, k-Nearest Neighbors, Artificial Neural Network, Convolutional Neural Network, and Random Forest [4].

- Stacking Framework: Predictions from base models served as input features to a meta-model that learned optimal combination weights.

- Class Imbalance Handling: Addressed through downsampling and Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE).

Performance Comparison in Cancer Classification

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AI Approaches in Cancer Classification

| Model | Cancer Types | Accuracy | Data Modality | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GraphVar (DL) [17] | 33 | 99.82% | Somatic mutations | 10,112 |

| Stacked Ensemble [4] | 5 | 98% | Multiomics (RNA-seq, methylation, mutations) | 3,980 |

| Performance-Weighted Voting [18] | 14 | 71.46% | Somatic mutations | 6,249 |

| CPEM (DL) [17] | 31 | 84% | Somatic alterations | Not specified |

| MuAt (DL) [17] | 24 | 89% | Simple & complex somatic alterations | Not specified |

Table 2: Strengths and Limitations of AI Approaches in Biomedical Research

| Approach | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | Automatic feature extraction; Handles raw, unstructured data; State-of-the-art accuracy with sufficient data [17] [13] | High computational requirements; Need for large datasets; "Black box" interpretability challenges [13] | Image-based diagnostics; Genomic sequence analysis; Multi-representation data integration |

| Ensemble Methods | Robust to noise and outliers; Reduces overfitting; Works well with diverse feature types; Often more interpretable [15] [16] [18] | Increased computational complexity; Model management overhead; Performance gains diminish beyond optimal ensemble size [15] | Multiomics integration; Modest dataset sizes; Heterogeneous data sources |

| Neural Networks | Captures complex nonlinear relationships; Flexible architecture designs; Good performance on diverse data types [11] [12] | Prone to overfitting with small datasets; Requires careful parameter tuning; May struggle with very high-dimensional data [11] | Traditional biomarker analysis; Structured biomedical data; Moderate-dimensional feature sets |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for AI-Based Cancer Research

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch [17] [12] | Deep learning framework with GPU acceleration | Implementing custom neural network architectures; Transfer learning |

| TensorFlow [11] [12] | End-to-end machine learning platform | Production-grade model deployment; TensorBoard visualization |

| scikit-learn [11] [16] | Machine learning library for classical algorithms | Preprocessing; Traditional ML models; Ensemble implementations |

| TCGA Data Portal [17] [4] | Repository of cancer genomic and clinical data | Accessing standardized multiomics datasets for model training |

| LinkedOmics [4] | Multiomics data resource from TCGA and CPTAC | Integrating across genomic, proteomic, and clinical dimensions |

| Google Cloud Platform [12] | Cloud computing with pre-configured AI services | Scalable training of large models; Collaborative research environments |

| Autoencoder Networks [4] | Dimensionality reduction while preserving biological properties | Handling high-dimensional omics data; Feature extraction |

The comparison of AI methodologies for cancer classification reveals a complex landscape where each approach offers distinct advantages. Deep learning architectures, particularly multi-representation frameworks like GraphVar, achieve remarkable accuracy by automatically learning discriminative patterns from raw data. Ensemble methods provide robust performance gains through strategic model combination, especially valuable when integrating diverse data modalities or working with smaller sample sizes. Neural networks serve as the foundational technology enabling both approaches, with their ability to model complex, non-linear relationships in biomedical data. The selection of an appropriate methodology depends on multiple factors including data volume and complexity, computational resources, and interpretability requirements. Future directions point toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of each paradigm, ultimately accelerating precision oncology through more accurate and biologically interpretable classification systems.

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are revolutionizing oncology by providing powerful tools for cancer classification, risk assessment, and treatment personalization. These technologies excel at identifying complex patterns within high-dimensional biological data, enabling advancements that traditional statistical methods cannot achieve. By integrating diverse data types—from genomic sequences and epigenetic markers to medical imagery and lifestyle factors—ML algorithms are accelerating the transition toward precision oncology. This paradigm shift allows researchers and clinicians to move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches, instead leveraging computational models that account for the unique molecular and clinical characteristics of individual patients and their cancers. This guide objectively compares the performance of various machine learning approaches across key applications in cancer research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with validated experimental data and methodologies to inform their work.

Performance Comparison of ML Approaches in Oncology

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for various machine learning approaches across different cancer research applications, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models in Cancer Applications

| Application Area | Best-Performing Model(s) | Reported Accuracy | Data Types Used | Cancer Types Studied | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Cancer Classification | Stacking Ensemble (SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF) | 98% | RNA sequencing, DNA methylation, Somatic mutations | Breast, Colorectal, Thyroid, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Corpus Uteri | [4] |

| Multicancer Classification from Genomic Data | GraphVar (ResNet-18 + Transformer) | 99.82% | Somatic mutation profiles (MAF files) | 33 cancer types from TCGA | [17] |

| Cancer Risk Prediction | Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) | 98.75% | Lifestyle factors, Genetic risk, Clinical parameters | Structured patient records | [19] |

| Brain Tumor Classification from MRI | Random Forest | 87% | MRI scans (T1c, T2w, FLAIR) | Brain tumors (BraTS 2024 dataset) | [5] |

| Pan-Cancer & Subtype Classification | XGBoost, SVM, Random Forest, DeepCC | Varies by cancer type | mRNA, miRNA, Methylation, Copy Number Variation | 32 TCGA cancer types, including BRCA, COAD, GBM, LGG, OV | [20] [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Omics Integration with Stacking Ensemble Learning

A 2025 study developed a stacking ensemble model to classify five common cancer types in Saudi Arabia by integrating three omics data types. The methodology involved a rigorous two-stage process to ensure robust performance [4].

Data Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Data Source: RNA sequencing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and somatic mutation/methylation data from LinkedOmics.

- Normalization: Transcripts per million (TPM) normalization for RNA-seq data to eliminate technical bias.

- Feature Extraction: Autoencoder technique with five dense layers (500 nodes each, ReLU activation) and 0.3 dropout to reduce high-dimensional data while preserving biological properties.

- Class Imbalance Handling: Downsampling and Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to address unequal class distribution.

Ensemble Architecture: The stacking model integrated five base learners:

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Random Forest (RF)

These models were combined using a deep learning-based meta-learner that learned to optimally weight predictions from the base models. The experiment was implemented in Python 3.10 on the Aziz Supercomputer, demonstrating the computational requirements for such integrative analyses [4].

Key Finding: Multiomics integration (98% accuracy) significantly outperformed single-omics approaches (RNA sequencing and methylation individually achieved 96%, while somatic mutations alone reached 81%), highlighting the value of combining complementary data types [4].

GraphVar Framework for Multicancer Classification

The GraphVar framework, introduced in a 2025 study, represents a novel approach to multicancer classification by integrating multiple representations of genomic data [17].

Data Preparation:

- Cohort: 10,112 patient samples across 33 cancer types from TCGA.

- Data Curation: Rigorous multi-step pipeline removing duplicate patient entries with stratified sampling (70% training, 10% validation, 20% testing).

- Input Representations:

- Variant Maps: Spatial representation with gene-level variant categories encoded as pixel intensities (SNPs=blue, insertions=green, deletions=red).

- Numeric Feature Matrix: 36-dimensional matrix capturing population allele frequencies and six predefined somatic variant spectra.

Model Architecture:

- Dual-Stream Design:

- ResNet-18 Backbone: Processes variant maps to extract spatial features and visual patterns.

- Transformer Encoder: Models contextual relationships within numeric feature matrices.

- Fusion Module: Concatenates features from both streams for final classification.

- Interpretability: Gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) localizes influential genomic regions, while KEGG pathway enrichment validates biological relevance.

Performance: The framework achieved exceptional performance (99.82% accuracy) by leveraging complementary data representations, demonstrating how specialized architectures can exploit different aspects of genomic information [17].

GraphVar Multi-Representation Framework for Cancer Classification

Traditional vs. Deep Learning for Medical Imaging

A 2025 comparative analysis on the BraTS 2024 dataset revealed surprising performance patterns between traditional and deep learning approaches for brain tumor classification [5].

Experimental Setup:

- Dataset: BraTS 2024 MRI dataset (T1c, T2w, FLAIR sequences).

- Preprocessing: Tumor volume computation from segmentation masks, binary labeling (high/low tumor burden based on median volume).

- Model Comparison:

- Traditional ML: Random Forest with PCA feature reduction.

- Deep Learning: Simple CNN, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, Inception-ResNetV2, EfficientNet.

Unexpected Result: Random Forest (87% accuracy) significantly outperformed all deep learning models (47-70% accuracy), challenging the conventional wisdom that DL universally surpasses traditional ML for image analysis tasks. This highlights the importance of matching model selection to specific dataset characteristics and clinical requirements [5].

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Machine Learning in Cancer Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Function and Utility | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Databases | MLOmics Database [20] [21] | Preprocessed, ML-ready multi-omics data | 8,314 samples across 32 cancer types; mRNA, miRNA, methylation, CNV data; Original, Aligned, and Top feature versions |

| Genomic Data Portals | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [4] [17] | Primary source of cancer genomic data | 20,000+ primary cancer samples across 33 cancer types; Multiple omics data types |

| LinkedOmics [4] | Multi-omics data integration | Multi-omics data from 32 TCGA cancer types; Linked with clinical proteomic data | |

| Analysis Frameworks | GraphVar [17] | Multi-representation cancer classification | Integrates variant maps and numeric features; ResNet-18 + Transformer architecture |

| Stacking Ensemble Framework [4] | Multi-omics data integration | Combines SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF; Handles class imbalance | |

| Biological Knowledge Bases | STRING Database [20] [21] | Protein-protein interaction networks | Supports biological interpretation; Integrated in MLOmics |

| KEGG Pathways [20] [17] | Pathway enrichment analysis | Functional validation of model findings; Biological relevance assessment |

MLOmics Database: A Closer Look

The MLOmics database addresses a critical bottleneck in cancer ML research by providing standardized, analysis-ready datasets [20] [21].

Feature Processing Tiers:

- Original Features: Complete feature sets directly extracted from source data.

- Aligned Features: Intersection of features present across all sub-datasets (shared genes).

- Top Features: Most significant features selected via ANOVA testing (p<0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction).

Available Task Types:

- Pan-cancer Classification: Identifying specific cancer types across 32 classes.

- Golden-standard Subtype Classification: Recognizing established molecular subtypes.

- Cancer Subtype Clustering: Discovering novel subtypes in unlabeled data.

- Omics Data Imputation: Handling missing data in multi-omics datasets.

This resource significantly reduces the preprocessing burden on researchers and enables fair model comparisons through standardized benchmarking [20].

The experimental data and methodologies presented in this comparison guide demonstrate that optimal algorithm selection for cancer classification depends heavily on data type, cancer spectrum, and clinical context. While complex deep learning architectures like GraphVar achieve remarkable performance on genomic data, traditional ensemble methods like Random Forest can surprisingly outperform them on specific imaging tasks. The consistent theme across applications is that multi-modal data integration—whether combining omics types or merging genomic with clinical data—consistently enhances predictive accuracy and clinical utility. As these technologies mature, addressing challenges related to interpretability, dataset bias, and computational requirements will be essential for translating machine learning advancements into tangible improvements in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection.

A Toolkit of Algorithms: From Classical Machine Learning to Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

The application of machine learning (ML) in oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer classification research, offering powerful tools for early detection and diagnostic precision. Among the diverse ML landscape, three classical supervised learners—Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees (DT), and Logistic Regression (LR)—have established themselves as foundational algorithms with distinct methodological advantages and practical utility. These algorithms serve as critical benchmarks against which more complex ensemble and deep learning approaches are measured in cancer prediction tasks [22] [23].

The performance of these classical learners is extensively documented across multiple cancer types, with breast cancer classification serving as a particularly rich domain for comparative analysis due to the widespread availability of standardized datasets and the critical importance of diagnostic accuracy. Similarly, in lung cancer prediction, these algorithms form the foundational layer upon which more specialized imaging analysis systems are built [24]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of SVM, DT, and LR through the lens of experimental cancer classification research, detailing their respective performance characteristics, optimal application contexts, and implementation considerations for researchers and clinical professionals.

Performance Comparison in Cancer Classification

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Studies

Experimental evaluations across multiple cancer types and datasets reveal distinct performance patterns for each classical supervised learner. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics from recent studies focused on breast cancer classification, where comparative data is most abundant.

Table 1: Performance comparison of classical supervised learners in breast cancer classification

| Algorithm | Reported Accuracy | Precision | Recall/Sensitivity | F1-Score | Dataset/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 97.07% [22], 97.9% [22], 98.25% [23], 99.51% (with feature selection) [23] | 84.72% [23] | 92.42% [23] | Not specified | Wisconsin Breast Cancer Dataset [22] [23] |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 98% [25], 96.9% (with neural network) [23], 99.12% (as AdaBoost-Logistic) [25] | 83.33% [23] | 90.91% [23] | 86.96% [23] | Wisconsin Breast Cancer Dataset [25], Fine needle aspiration cytology data [23] |

| Decision Tree (DT) | 97.7% [23], 88.0% (Decision Stump variant) [23] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Dataset with 569 cases (357 benign, 212 malignant) [23] |

For lung cancer classification, although direct comparisons of these specific algorithms are less frequently documented, they often serve as baseline models in larger comparative studies. One comprehensive evaluation of nine ML classifiers for lung cancer prediction positioned these classical learners within a broader performance spectrum, with ensemble methods generally achieving superior results [24]. The Random Forest classifier, an ensemble extension of Decision Trees, achieved remarkable performance with 0.9893 accuracy, 0.99 precision, and 0.99 F1-score in lung cancer detection using synthetic data augmentation [24].

Relative Strengths and Limitations

Each algorithm demonstrates characteristic strengths that make it suitable for specific research contexts and data characteristics:

Support Vector Machines excel in high-dimensional feature spaces, effectively handling datasets with numerous predictive variables. Their ability to find optimal separation hyperplanes makes them particularly valuable when clear margin separation exists between classes [23]. The consistent high accuracy across multiple breast cancer studies positions SVM as a robust choice for binary classification tasks with complex feature relationships.

Logistic Regression provides probabilistic interpretations and model transparency, valuable when researchers require both prediction and explanatory insights [26] [23]. Its performance in multiple studies, particularly when enhanced with ensemble methods like AdaBoost (achieving 99.12% accuracy), demonstrates its continued relevance despite being one of the oldest classification techniques [25].

Decision Trees offer superior interpretability with visual decision pathways that can be valuable in clinical settings where model transparency impacts adoption [23]. However, their performance variability (evident in the 88-97.7% accuracy range) suggests sensitivity to dataset characteristics and implementation specifics, with simpler variants like Decision Stumps exhibiting notably lower performance [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Rigorous experimental protocols underlie the performance metrics reported in comparative studies. The following workflow visualization represents a consolidated research methodology for evaluating classical supervised learners in cancer classification.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comparing classical supervised learners in cancer classification

Critical Methodological Components

The experimental protocols referenced in performance comparisons share several standardized components that ensure rigorous evaluation:

Data Preprocessing Procedures: Studies consistently apply feature scaling and normalization to address dimensional inconsistencies among predictive variables [25] [23]. Techniques for handling missing values are implemented to preserve dataset integrity, with some researchers employing statistical tests like the Wilcoxon rank sum test to identify significant feature distributions between classes [25].

Feature Selection Techniques: Dimensionality reduction is frequently employed to enhance model performance and interpretability. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is commonly implemented to transform features into orthogonal components that capture maximum variance [23]. Correlation analysis, particularly Spearman correlation for non-normally distributed data, helps identify and retain the most predictive features while eliminating redundancy [25].

Validation Methodologies: To ensure robust performance estimation, studies employ stratified k-fold cross-validation (typically with k=5 or k=10) that maintains class distribution across folds [22]. An 80/20 split for training and validation subsets is also commonly implemented, with the validation cohort representing approximately 20% of the total dataset [26]. These approaches mitigate overfitting and provide realistic performance expectations for clinical deployment.

Hyperparameter Optimization: Grid search algorithms with cross-validation are systematically applied to identify optimal hyperparameter configurations [26]. For SVM, parameters including regularization (C), kernel coefficient (γ), and degree are tuned; Decision Trees undergo optimization for maximum depth, minimum samples per split, and leaf size; Logistic Regression primarily focuses on regularization strength and type (L1/L2) [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental comparisons of classical supervised learners rely on both data resources and computational tools that constitute essential infrastructure for cancer classification research.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and resources for cancer classification studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Datasets | Wisconsin Breast Cancer Diagnostic (WBCD) [25] [22] [23], Breast Cancer Coimbra Dataset [22], PLCO Lung Datasets [27], NLST LDCT Images [28] | Provide benchmark data for algorithm comparison and validation | Model training, performance benchmarking, methodological reproducibility |

| Computational Frameworks | Python Scikit-learn [26] [29], WEKA [23], Anaconda Environment [29] | Implement algorithms, preprocessing, and evaluation metrics | Algorithm development, hyperparameter tuning, performance assessment |

| Data Augmentation Tools | SMOTE [23], CTGAN [24], Gaussian Copula [22] | Address class imbalance and expand training data | Enhancing model robustness, mitigating overfitting, improving minority class prediction |

| Visualization & Interpretation | SHAP [30], 3D Slicer [28] | Model interpretation and medical image analysis | Feature importance analysis, clinical validation, result explanation |

Comparative Analysis and Discussion

Performance Interpretation and Contextual Factors

While quantitative metrics provide straightforward performance comparisons, several contextual factors significantly influence the practical utility of each algorithm:

The dataset characteristics substantially impact relative algorithm performance. Studies utilizing the Wisconsin Breast Cancer Dataset consistently report higher accuracy scores across all three algorithms compared to more complex clinical datasets [25] [22] [23]. This suggests that curated datasets with well-engineered features may inflate performance expectations compared to real-world clinical data with greater heterogeneity and noise.

Feature selection and engineering dramatically influence outcomes, with studies implementing strategic feature reduction often achieving superior performance. The SVM algorithm achieved 99.51% accuracy with only five carefully selected features, outperforming implementations using the full feature set [23]. Similarly, Logistic Regression benefited from feature elimination prior to classification, achieving 96.9% precision when combined with neural networks [23].

The computational efficiency of these algorithms varies substantially, with Decision Trees generally offering faster training times but potentially lower predictive consistency. Logistic Regression provides the most efficient parameter estimation, while SVM, particularly with non-linear kernels, demands greater computational resources for large datasets [23].

Integration Trends and Ensemble Applications

A prominent trend in recent cancer classification research involves integrating classical learners into ensemble frameworks that leverage their complementary strengths:

The AdaBoost-Logistic hybrid model demonstrates how classical algorithms can be enhanced through ensemble methods, achieving 99.12% accuracy by sequentially focusing on misclassified instances [25]. This represents a significant improvement over standard Logistic Regression implementation while maintaining model interpretability.

Random Forest, as an ensemble extension of Decision Trees, consistently ranks among top performers in comparative studies, achieving 99.3% accuracy on test datasets and outperforming its individual tree components [23]. In lung cancer detection, Random Forest achieved remarkable performance (0.9893 accuracy, 0.99 precision and F1-score) when combined with synthetic data generation using CTGAN [24].

Deep learning-based multi-model ensembles represent the current frontier, with stacked ensembles incorporating SVM, Random Forest, Naive Bayes, and Logistic Regression with Convolutional Neural Networks for feature extraction [22]. These approaches acknowledge that classical supervised learners retain value even alongside more complex deep learning architectures.

The comparative analysis of Support Vector Machines, Decision Trees, and Logistic Regression in cancer classification reveals a nuanced performance landscape where each algorithm exhibits distinct advantages depending on research objectives, data characteristics, and implementation context. SVM demonstrates consistent predictive power for complex feature relationships, Logistic Regression offers balanced performance with interpretability, and Decision Trees provide transparent decision pathways valuable for clinical explanation.

Rather than a definitive superiority of any single algorithm, the experimental evidence suggests that context-dependent selection and strategic integration through ensemble methods yield optimal results. As cancer classification research evolves toward more complex multi-modal data and personalized prediction tasks, these classical supervised learners continue to serve as essential benchmarks, component algorithms in ensemble systems, and accessible entry points for methodological development in computational oncology. Their enduring relevance underscores the importance of mastering these fundamental tools while innovating toward increasingly sophisticated analytical frameworks.

Ensemble methods represent a cornerstone of modern machine learning, operating on the principle that multiple models working in concert can achieve superior accuracy and robustness compared to any single algorithm [31] [32]. These methods are particularly valuable in high-stakes domains like medical diagnostics and cancer classification, where improved prediction accuracy can directly impact patient outcomes [33]. For researchers and clinicians working in oncology, selecting the appropriate ensemble algorithm is crucial for developing reliable classification systems.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three powerful ensemble techniques—Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and CatBoost—within the context of cancer classification research. We examine their underlying architectures, performance metrics, and implementation considerations through the lens of recent experimental studies, enabling informed algorithm selection for medical prediction tasks.

Understanding Ensemble Methods and Their Significance

Ensemble methods combine multiple machine learning models to produce more accurate and stable predictions than individual models. Their effectiveness stems from the mathematical principle of the bias-variance tradeoff, where combining models helps balance oversimplification (high bias) and overfitting to noise (high variance) [32]. In healthcare applications like cancer classification, this translates to more reliable models that generalize better to new patient data.

The three main families of ensemble methods are:

- Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): Trains multiple models in parallel on different data subsets and aggregates their predictions, effectively reducing variance [31].

- Boosting: Trains models sequentially, with each new model focusing on correcting errors made by previous ones, reducing both bias and variance [32].

- Stacking: Combines predictions from multiple different models using a meta-learner that learns optimal weighting schemes [34].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between the bagging and boosting approaches, which form the basis for the algorithms discussed in this guide.

Algorithm Deep Dive: Architectures and Mechanisms

Random Forest: The Democratic Approach

Random Forest employs a bagging methodology where multiple decision trees are constructed in parallel, each trained on a random subset of the training data and features [31] [35]. This enforced diversity prevents individual trees from becoming too specialized and ensures the collective "forest" possesses robust predictive capabilities. For classification tasks like cancer detection, the final prediction is determined by majority voting across all trees in the forest [35].

Key characteristics of Random Forest include:

- Parallel Training: All trees are built independently, enabling potential parallelization [31].

- Feature Randomness: At each split, the algorithm randomly selects a subset of features for consideration, further decorrelating the trees [35].

- Built-in Validation: Each tree is trained on approximately two-thirds of the data, with the remaining "out-of-bag" samples serving as natural validation sets [35].

Gradient Boosting: The Sequential Learner

Gradient Boosting builds models sequentially, with each new tree specifically trained to correct the errors made by its predecessors [32] [35]. Unlike Random Forest's democratic approach, boosting employs a mentorship model where successive models focus on challenging instances that previous models misclassified. This sequential error correction makes boosting algorithms particularly powerful for capturing complex patterns in data.

The algorithm works by:

- Fitting an initial weak learner to the data

- Computing the residuals (errors) between predictions and actual values

- Training subsequent models to predict these residuals

- Combining all models in a weighted manner to form the final predictor [35]

CatBoost: The Categorical Data Specialist

CatBoost is a recent gradient boosting variant specifically designed to handle categorical features efficiently [36]. It modifies the standard gradient boosting approach to avoid prediction shift and employs an innovative method called "Ordered Boosting" that processes data in a permuted order to reduce overfitting [36]. For healthcare datasets containing mixed data types (including categorical variables like patient demographics, symptom categories, and diagnostic codes), CatBoost's specialized handling can provide significant advantages.

CatBoost's distinctive features include:

- Ordered Target Statistics: Effectively encodes categorical features without manual preprocessing [36].

- Prediction Shift Reduction: Implements ordered boosting to prevent target leakage [36].

- Efficient GPU Support: Optimized for accelerated training on graphics processing units [36].

Performance Comparison in Cancer Classification

Experimental Framework from Lung Cancer Classification Study

A rigorous 2024 study directly compared CatBoost and Random Forest for lung cancer classification using a Bayesian Optimization-based hyperparameter tuning approach [33]. The experimental methodology consisted of:

- Data Collection: Acquisition of lung cancer patient medical records and diagnostic data

- Data Preprocessing: Handling missing values, normalization, and feature engineering

- Data Partitioning: 10-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation

- Model Training: Implementation of CatBoost and Random Forest with both default and tuned hyperparameters

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Bayesian Optimization to efficiently explore hyperparameter spaces

- Performance Evaluation: Comprehensive assessment using multiple classification metrics [33]

The following diagram illustrates this experimental workflow, which is typical in medical classification research:

Quantitative Performance Results

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ensemble Methods for Lung Cancer Classification [33]

| Algorithm | Hyperparameter Tuning | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Default | 0.94462 | 0.94885 | 0.94652 | 0.94425 | 0.99859 |

| Random Forest | Bayesian Optimization | 0.97106 | 0.97339 | 0.97185 | 0.97011 | 0.99974 |

| CatBoost | Default | 0.94585 | 0.95001 | 0.94725 | 0.94559 | 0.99861 |

| CatBoost | Bayesian Optimization | 0.96142 | 0.96389 | 0.96205 | 0.96078 | 0.99915 |

Table 2: Broader Algorithm Comparison Across Multiple Datasets [36]

| Algorithm | Training Speed | Generalization Accuracy | Categorical Feature Handling | Hyperparameter Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Medium | High | Requires encoding | Low |

| XGBoost | Medium | Very High | Requires encoding | High |

| LightGBM | Very Fast | High | Requires encoding | Medium |

| CatBoost | Slow | Very High | Native handling | Low |

The results demonstrate that Random Forest with Bayesian Optimization achieved the highest performance across all metrics for lung cancer classification, slightly outperforming CatBoost [33]. Both algorithms significantly benefited from hyperparameter tuning, with Random Forest showing a 2.8% improvement in accuracy and CatBoost a 1.6% improvement after optimization [33].

Notably, the study found that hyperparameter tuning was more crucial for gradient-boosting variants than for Random Forest, with default CatBoost performing competitively with tuned versions of other algorithms [36]. This has practical implications for researchers with limited computational resources for extensive hyperparameter optimization.

Implementation Considerations for Medical Research

Hyperparameter Tuning with Bayesian Optimization

The significant performance gains observed in the lung cancer classification study highlight the importance of proper hyperparameter tuning [33]. Bayesian Optimization has emerged as a superior approach for this task, as it builds a probabilistic model of the objective function to direct the search toward promising hyperparameters more efficiently than random or grid search [33] [34].

Key hyperparameters for each algorithm include:

- Random Forest: Number of trees, maximum depth, minimum samples split, and minimum samples leaf [33] [35]

- Gradient Boosting variants: Learning rate, number of trees, maximum depth, and subsampling rate [36]

The following workflow illustrates the Bayesian Optimization process for hyperparameter tuning:

The Research Toolkit for Cancer Classification

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Framework | Efficient hyperparameter tuning | BayesianOptimization Python package [33] |

| Cross-Validation Strategy | Robust performance estimation | 10-fold cross-validation [33] |

| Data Preprocessing Pipeline | Handling missing values, normalization, feature engineering | Scikit-learn preprocessing modules [37] |

| Ensemble Algorithm Libraries | Implementation of Random Forest, CatBoost, and other ensemble methods | Scikit-learn, CatBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM [32] [35] |

| Model Interpretation Tools | Feature importance analysis, model explainability | SHAP, LIME, built-in feature importance [35] |

Ensemble methods—particularly Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and its variant CatBoost—offer powerful approaches for cancer classification tasks. The experimental evidence demonstrates that:

Random Forest with Bayesian Optimization currently delivers state-of-the-art performance for lung cancer classification, achieving an accuracy of 0.97106, precision of 0.97339, and AUC of 0.99974 [33].

Hyperparameter tuning is essential for maximizing performance, with Bayesian Optimization providing an efficient framework for this process [33] [34].

Algorithm selection involves trade-offs: While Random Forest excelled in the specific lung cancer classification task, CatBoost offers advantages for datasets rich in categorical features, and LightGBM provides exceptional training speed for large-scale datasets [36].

For medical researchers developing cancer classification systems, we recommend implementing a comparative approach that tests multiple ensemble methods with rigorous hyperparameter tuning. The choice of algorithm should consider dataset characteristics, computational resources, and interpretability requirements. As ensemble methods continue to evolve, their application in oncology promises to enhance early detection, improve diagnostic accuracy, and ultimately contribute to better patient outcomes.

In the field of cancer research, the accurate classification of cancer types is a critical step toward personalized treatment and improved patient outcomes. Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing complex medical data. These architectures leverage different strengths: CNNs excel at identifying spatial hierarchies in data, making them ideal for image analysis, while RNNs handle sequential information, capturing temporal dependencies and context. This guide provides an objective comparison of CNN and RNN performance, supported by experimental data from recent cancer classification studies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and applying these algorithms effectively.

CNNs and RNNs are founded on distinct architectural principles, making them suited to different types of data and analytical tasks.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): CNNs are primarily designed for processing spatial data with a grid-like topology, such as images. Their architecture is built around convolutional layers that use filters to scan input data and detect local patterns—such as edges, colors, and textures—at various levels of abstraction. Through operations like convolution and pooling, CNNs progressively build up a hierarchy of features, from simple to complex, which allows them to excel in tasks like image recognition and classification [38]. This makes them exceptionally well-suited for analyzing medical images, including computed tomography (CT) scans and dermoscopic images.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): RNNs are specialized for sequential data or time-series data. Their core feature is a feedback loop within the network's nodes (recurrent cells), which allows them to maintain a 'memory' of previous inputs in the sequence. This architecture enables RNNs to model temporal dynamics and contextual relationships where the order of information is critical. However, basic RNNs can struggle with long-range dependencies due to issues like vanishing gradients. Advanced variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks address this by using gating mechanisms to preserve information over longer sequences, making them powerful for tasks like natural language processing, speech recognition, and analyzing genetic sequences [38] [39].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architectural differences and data flow in CNNs and RNNs:

Performance Comparison in Cancer Classification

Empirical studies across various cancer types demonstrate the performance of CNNs and RNNs, both as standalone models and in hybrid configurations.

Performance on Medical Imaging Data

CNNs are the established standard for image-based cancer diagnosis. Their performance is benchmarked in the table below, which compiles results from recent studies on lung and skin cancer classification.

Table 1: CNN Performance in Image-Based Cancer Classification

| Cancer Type | Data Modality | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | CT Scans (2D) | Multiple 2D CNNs (e.g., InceptionV3) | Best AUROC: 0.79 | [40] |

| Lung Cancer | CT Scans (3D) | Multiple 3D CNNs (e.g., ResNet) | Best AUROC: 0.86 | [40] |

| Lung Cancer | CT Scans | Custom CNN | Accuracy: 99.27%, Precision: 99.44%, Recall: 98.56% | [41] |

| Skin Cancer | Dermoscopic Images | CNN-based Classifiers | Performance equivalent or superior to human experts | [42] |

Performance on Sequential and Genomic Data

RNNs and hybrid models demonstrate strong capabilities in classifying non-image data, such as gene expression sequences.

Table 2: RNN and Hybrid Model Performance in Genomic Cancer Classification

| Cancer Type | Data Modality | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Cancer | Gene Expression Data | 1D-CNN + RNN | Accuracy: 90% | [43] |

| Brain Cancer | Gene Expression Data | BO + 1D-CNN + RNN | Accuracy: 100% | [43] |

| Skin Cancer | Dermoscopic Images | Hybrid CNN-LSTM | High accuracy across precision, recall, and F1-score | [44] |

| Skin Cancer | Dermoscopic Images | CNN-RNN with ResNet-50 backbone | Average Recognition Accuracy: 99.06% | [45] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section details the experimental setups from key studies cited in this guide, providing a blueprint for reproducible research.

Protocol 1: Lung Cancer Classification from CT Scans

A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated 2D and 3D CNNs for lung cancer risk prediction (malignant-benign classification) using a subset of the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) dataset [40].

- Dataset: 253 participants from the NLST LDCT arm, with CT scans preprocessed into 2D-image and 3D-volume formats based on radiologist-annotated nodules. The cohort was split into 150 patients for training and 103 for testing.

- Model Training: The study implemented and compared ten 3D models (e.g., ResNet, R2Plus1D) and eleven 2D models (e.g., InceptionV3, ViTs). Models were pretrained on large-scale datasets like ImageNet and Kinetics, then fine-tuned on the NLST data.

- Evaluation: Performance was measured using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). The study concluded that 3D CNNs generally outperformed 2D models, with the best 3D model achieving an AUROC of 0.86.

Protocol 2: Brain Cancer Classification from Gene Expression Data

A study on brain cancer classification employed a hybrid 1D-CNN and RNN model on gene expression data from the Curated Microarray Database (CuMiDa) [43].

- Dataset: The GSE50161 brain cancer dataset from CuMiDa, containing 130 samples with 54,676 genes each, categorized into five classes (including healthy tissue).

- Model Architecture and Training:

- 1D-CNN Layer: Processed the raw gene expression sequences to extract local, high-level features.

- RNN Layer (LSTM/GRU): Analyzed the feature sequences captured by the CNN to model long-range dependencies and contextual information within the genomic data.

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): A hyperparameter tuning strategy was applied to optimize the model, significantly boosting performance.

- Evaluation: The hybrid model achieved 90% accuracy. When enhanced with Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, the model's accuracy reached 100%, surpassing traditional machine learning models.

Protocol 3: Skin Cancer Classification via Hybrid LSTM-CNN

A novel approach for skin cancer classification used a hybrid model that integrated LSTM networks with CNNs on the HAM10000 dataset of 10,015 skin lesion images [44].

- Data Preprocessing: Each skin lesion image was divided into a sequence of patches. This patching technique allowed the model to treat the image as a sequence of spatial segments.

- Model Architecture and Training:

- LSTM Component: Processed the sequence of image patches to capture temporal dependencies and relationships between different spatial regions.

- CNN Component: Applied time-distributed convolutional layers to extract spatial features (e.g., texture, edges, color) from each individual patch.

- Classification: A final Softmax layer provided a probability distribution over the possible skin cancer classes.

- Evaluation: The model's performance was evaluated using accuracy, recall, precision, F1-score, and ROC curve analysis, demonstrating superior results compared to models using only CNN or LSTM.

The workflow for a typical hybrid CNN-RNN model in medical data analysis is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key resources and computational tools essential for conducting deep learning research in cancer classification.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CuMiDa | A curated benchmark of cancer gene expression datasets for evaluating machine learning algorithms. | Contains 78 datasets across 13 cancer types; ideal for genomic classification tasks [43]. |

| NLST Dataset | A large, annotated dataset of low-dose CT scans from a lung cancer screening trial. | Essential for training and validating lung cancer detection models; includes nodule annotations [40]. |

| HAM10000 | A large, public collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of skin lesions. | Contains 10,015 images; used for training and benchmarking skin cancer classification models [44]. |

| ISIC Archive | An extensive repository of dermoscopic images for skin cancer analysis. | Provides thousands of images with metadata; supports algorithm development and testing [45]. |

| Bayesian Hyperparameter Optimization | An automated strategy for selecting optimal model parameters to maximize performance. | Used to fine-tune deep learning models, significantly improving accuracy as demonstrated in [43]. |

| ResNet-50 | A deep CNN architecture known for its effectiveness in feature extraction from images. | Often used as a backbone or feature extractor in hybrid models for medical imaging [45]. |

| Data Augmentation | Techniques to artificially expand the size and diversity of a training dataset. | Mitigates overfitting in medical image analysis where data can be limited [44] [45]. |

CNNs and RNNs offer complementary strengths for cancer classification. CNNs are the undisputed choice for spatial data analysis, such as interpreting CT scans or identifying skin lesions from images, with 3D CNNs showing a distinct performance advantage for volumetric data. In contrast, RNNs, particularly in hybrid models with CNNs, unlock the potential of sequential and structured data like gene expression profiles, achieving remarkable accuracy. The emerging trend of hybrid architectures, which leverage CNN for spatial feature extraction and RNN for sequential modeling, consistently delivers state-of-the-art performance across diverse data types. For researchers, the selection between a CNN, RNN, or a hybrid model should be guided by the fundamental nature of the data—spatial or sequential—and the specific clinical question at hand.

The integration of multiomics data—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics—has become a cornerstone in advancing cancer classification research. This integration presents a significant computational challenge due to the high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and complex interdependencies of the data types. Machine learning (ML) provides powerful tools to address these challenges, with stacking ensemble methods and advanced fusion techniques emerging as state-of-the-art approaches for building comprehensive and accurate classification models. These methods move beyond single-omics or single-model analyses by strategically combining multiple data types and algorithms to capture a more holistic view of cancer biology, leading to improved diagnostic and prognostic capabilities for researchers and clinicians. This guide objectively compares the performance, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of these leading methodologies within the context of cancer classification.

Performance Comparison of Multiomics Integration Techniques

Different multiomics integration strategies offer distinct advantages and trade-offs in performance, complexity, and biological interpretability. The table below provides a comparative overview of three primary integration paradigms.

Table 1: Comparison of Multiomics Integration Techniques for Cancer Classification

| Integration Type | Description | Reported Performance (Accuracy) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Simple concatenation of raw features from multiple omics into a single matrix prior to model training. | Varies widely; often lower than advanced methods due to the "curse of dimensionality." | Simple to implement; allows for immediate analysis of feature interactions. | Highly vulnerable to overfitting; requires robust feature selection to handle high dimensionality [46]. |

| Late Integration | Separate models are trained on each omics type, and their predictions are combined (e.g., by voting or averaging). | Generally strong, but dependent on the fusion method. | Leverages omics-specific patterns; modular and flexible design. | May fail to capture complex, non-linear interactions between different omics layers [47] [46]. |

| Middle Integration (Advanced Fusion) | Uses machine learning to integrate data without initial concatenation, often learning a joint representation. | Highest performing; e.g., Stacking Ensembles (98%) [4] [48] and GNNs (superior to baselines) [47] [49]. | Effectively captures complex, non-linear cross-omics interactions; robust to high-dimensional data. | Computationally intensive; complex model tuning and implementation [47] [49]. |

Middle integration techniques, particularly stacking ensembles and graph-based models, consistently demonstrate superior performance in comparative studies. For instance, a stacking ensemble model integrating RNA sequencing, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data achieved a remarkable 98% accuracy in classifying five common cancer types, outperforming models trained on individual omics data [4] [48]. Similarly, novel Graph Neural Network (GNN) frameworks have been shown to outperform other state-of-the-art baseline models in terms of accuracy, F1 score, precision, and recall on TCGA pan-cancer data [47].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data of Featured Techniques

This section details the methodologies and experimental outcomes of two leading middle-integration approaches: Stacking Ensembles and Graph Neural Networks.

Stacking Ensemble Techniques

Stacking, or stacked generalization, is an ensemble meta-learning technique that combines multiple base classifiers through a meta-learner.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Stacking Ensemble Models

| Study & Focus | Base Learners | Meta-Learner | Omics Data Types | Cancer Types / Task | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stacked Deep Learning Ensemble [4] [48] | SVM, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), CNN, Random Forest (RF) | Not Specified | RNA Sequencing, Somatic Mutation, DNA Methylation | 5 types (e.g., Breast, Colorectal) | Accuracy: 98% (Multiomics) vs. 96% (single-omics best) |

| MASE-GC for Gastric Cancer [50] | SVM, RF, Decision Tree, AdaBoost, CNN | XGBoost | Exon Expression, mRNA Expression, miRNA Expression, DNA Methylation | Gastric Cancer (TCGA-STAD) | Accuracy: 98.1%, Precision: 0.9845, Recall: 0.992, F1-Score: 0.9883 |

| Ensemble ML on Exome Data [51] | KNN, SVM, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Majority Voting | Exome Sequencing (Mutation Data) | 5 types (e.g., Ovarian, Pancreatic) | Accuracy: 82.91% (increased to 0.92 metric value with GAN-augmented data) |

Protocol Summary: A typical stacking ensemble workflow involves two main stages. First, in the base learning stage, multiple heterogeneous models (e.g., SVM, RF, CNN) are trained on the multiomics data. Second, in the meta-learning stage, the predictions (class probabilities or labels) from these base models are used as input features to train a meta-classifier (e.g., XGBoost, logistic regression), which makes the final prediction [4] [50]. Robust preprocessing is critical and often includes data normalization, feature extraction using autoencoders to reduce dimensionality, and handling class imbalance with techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) [4] [51] [50].

Diagram 1: Stacking ensemble workflow for multiomics data.

Graph-Based Fusion Techniques

Graph-based models represent multiomics data as a graph, where nodes can be patients, genes, or other biological entities, and edges represent relationships or similarities.

Protocol Summary: A prominent approach is the use of Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) or Graph Attention Networks (GATs). The workflow typically involves:

- Graph Construction: Building a patient similarity network (PSN) using algorithms like Similarity Network Fusion (SNF), which integrates multiple omics types to create a fused graph structure where nodes represent patients [49].

- Feature Learning: Using autoencoders to extract compact, latent feature representations from each high-dimensional omics dataset [49].

- Graph Neural Network Training: The latent features and the PSN are fed into a GCN or GAT. The GNN learns by propagating and transforming information across the graph, effectively capturing high-order relationships between patients and their multiomics profiles [47] [49]. Deep GCN architectures with residual connections can be used to overcome the over-smoothing problem of shallow GNNs and capture more complex relationships [49].

Table 3: Experimental Performance of Graph-Based Fusion Models

| Study & Model | GNN Type | Omics Data Types | Graph Structure | Cancer Types / Task | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal GNN Framework [47] | GCN & GAT | mRNA Expression, CNV, miRNA Expression | Heterogeneous multi-layer graph with intra-omic (GGI) and inter-omics (miRNA-gene) connections | Pan-cancer & Breast Cancer (BRCA) molecular subtype classification | Superior accuracy, F1, precision, and recall vs. baseline models. |

| DeepMoIC [49] | Deep GCN | Copy Number Variation, mRNA Expression, DNA Methylation | Patient Similarity Network (PSN) from SNF | Pan-cancer and 3 cancer subtype datasets | Consistently outperformed state-of-the-art models across all datasets. |

Diagram 2: Graph-based fusion with GNNs for multiomics data.

Successfully implementing multiomics integration models requires a suite of data, software, and computational resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Multiomics Cancer Classification

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Primary source of multiomics data from thousands of tumor samples across >30 cancer types. | [4] [47] [46] |

| LinkedOmics | Provides multiomics data from all 32 TCGA cancer types and CPTAC cohorts. | [4] [48] | |

| International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) | Complements TCGA with multiomics data from an international consortium. | [46] | |

| Biological Knowledge Bases | Gene-Gene Interaction (GGI) Networks | Provides intra-omic connections for constructing biological graphs (e.g., from BioGrid). | [47] |

| miRNA-Gene Target Networks | Provides inter-omics connections for constructing biological graphs (e.g., from miRDB). | [47] | |

| Computational Tools & Techniques | Python & Scikit-learn | Core programming language and library for implementing classic ML models and preprocessing. | [4] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Essential for building and training complex models like CNNs, Autoencoders, and GNNs. | [4] [49] | |

| Graph Neural Network Libraries (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | Specialized libraries for efficient implementation of GCNs, GATs, and other GNN variants. | - | |

| Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) | Algorithm to address class imbalance in datasets by generating synthetic minority class samples. | [4] [51] [50] | |

| Hardware | High-Performance Computing (HPC) / Cloud Platforms | Crucial for handling the computational load of deep learning models and large multiomics datasets. | [4] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores the transformative potential of advanced middle-integration techniques for multiomics cancer classification. Stacking ensembles excel through their model-agnostic flexibility, leveraging the strengths of diverse algorithms to achieve benchmark-setting accuracy, as demonstrated by results exceeding 98% [4] [50]. In parallel, graph-based fusion techniques, particularly GNNs, offer a powerful paradigm for directly modeling the complex, non-Euclidean relationships inherent in biological systems, leading to robust performance in subtype classification tasks [47] [49]. The choice between these leading approaches depends on the specific research objectives, available data structures, and computational resources. Stacking ensembles provide a powerful, general-purpose framework, while GNNs are particularly suited for investigations where the explicit modeling of biological networks is critical. Together, these methodologies are paving the way for more precise, reliable, and biologically insightful tools for cancer research and personalized medicine.

Navigating Practical Hurdles: Feature Selection, Imbalanced Data, and Model Explainability

The analysis of high-dimensional data presents a fundamental challenge in modern cancer research. Gene expression data from microarray technology, which allows simultaneous measurement of tens of thousands of genes across relatively few patient samples, epitomizes this curse of dimensionality [52]. The presence of numerous irrelevant, redundant, or noisy features can severely degrade the performance of classification algorithms, potentially obscuring critical biomarkers and reducing diagnostic accuracy [53] [54]. Feature selection (FS) addresses this challenge by identifying a compact subset of highly discriminative features, which not only improves classification performance but also reduces computational costs and enhances the interpretability of models—a crucial consideration for clinical applications [54] [55].