MIQE Guidelines for qPCR Validation: Ensuring Reproducibility in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines, a critical framework for ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of qPCR...

MIQE Guidelines for qPCR Validation: Ensuring Reproducibility in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines, a critical framework for ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of qPCR data. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of MIQE, including the recent MIQE 2.0 update. It offers detailed methodological advice for assay design and application in regulated environments like cell and gene therapy, outlines best practices for troubleshooting and optimization, and establishes a rigorous approach for assay validation. By demystifying these standards, the article aims to empower scientists to produce robust, transparent, and publication-ready qPCR results that uphold the integrity of scientific literature and regulatory submissions.

Understanding MIQE: The Foundation of Reproducible qPCR Science

In the world of molecular biology, the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) emerged as a transformative technology, becoming a ubiquitous mainstay of research laboratories worldwide. By the early 2000s, qPCR had progressed from its first-generation PCR roots to become the "Gold standard" for nucleic acid quantification [1]. However, this rapid adoption and the technique's perceived maturity concealed a growing problem. The relegation of qPCR materials and methods to online supplements in scientific papers was becoming commonplace, leading to publications containing insufficient technical information for work to be reproduced [2]. This lack of transparency, combined with the frequent use of flawed protocols, created an environment where the publication of technically questionable and irreproducible results was increasingly likely [2]. The scientific community needed a corrective measure, a set of standards that would restore rigor and credibility to qPCR experiments. This set of standards would become known as the MIQE guidelines.

The Catalyzing Event: Unreproducible Science and the Measles Virus Controversy

The direct impetus for creating the MIQE guidelines was a specific scientific controversy that exposed critical flaws in how qPCR experiments were being conducted and reported. In 2002, a paper was published that claimed to have detected measles virus in children with autism using RT-qPCR [3]. This finding was significant and, if true, would have had major implications for public health and autism research.

However, when other scientists attempted to verify these results, they proved to be completely unreproducible [3]. Further scrutiny revealed that the authors of the original study had not themselves attempted to reproduce their results. Moreover, the raw data was found to contain a large amount of errors and basic mistakes in analysis [3]. This incident highlighted a broader crisis in qPCR-based research: the low quality of data being submitted to academic journals, which was increasingly common as Next Generation Sequencing technologies made such experiments more affordable and widespread [3]. The measles virus controversy demonstrated that without strict standards, even high-impact claims could be built on unreliable foundations, ultimately wasting scientific resources and potentially misdirecting entire research fields.

The Formulation of a Solution: Birth of the MIQE Guidelines

In response to these challenges, Stephen Bustin led an international consortium of scientists in 2009 to devise the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments, or MIQE, guidelines [3] [4]. The primary objective was to provide a standardized framework for conducting and reporting qPCR experiments, thereby ensuring a baseline level of quality and transparency [3]. The guidelines were not intended to point out pitfalls but to help researchers publish high-end, reproducible papers [1].

The MIQE guidelines were structured as a comprehensive checklist covering all aspects of a qPCR experiment, from initial sample acquisition to final data analysis [3] [2]. To prioritize requirements, items were categorized as either Essential (E) for publication or Desirable (D) for best practice [3]. The guidelines emphasized that full disclosure of all reagents, sequences, and analysis methods was non-negotiable for independent verification and reproducibility [4].

Core Philosophical Framework of MIQE

The driving philosophy behind MIQE can be summarized by a quote from PCR's inventor, Kary Mullis: "Law shuttles between freeing us and enslaving us" [1]. The MIQE guidelines represent the law for qPCR technique. They enslave molecular biologists into a strict path with financial burdens, but they free us from the 'human-errors' that can compromise our results [1]. By imposing a rigorous standard, the guidelines seek to make PCR a more infallible tool, which is especially critical when research findings impact human health and clinical decision-making [1].

Evolution and Adoption: The Journey Following the 2009 Publication

After their publication in Clinical Chemistry in 2009, the MIQE guidelines began to influence the scientific community, though adoption faced initial hurdles.

Refinements and Expansions

Recognizing that the comprehensive guidelines could be daunting, a MIQE précis was published in 2010, offering an abridged set of recommendations for reporting key parameters of established assays [2]. This was followed by the development of specialized guidelines for emerging technologies, including digital PCR (dPCR) and single-cell qPCR [3]. The guidelines have continued to evolve, with a new MIQE 2.0 version announced to address advances in reagents, methods, and instrumentation [5].

Impact and Challenges in the Scientific Community

An analysis on the tenth anniversary of MIQE revealed that while qPCR had become a truly global technique with publications from 184 countries, the adoption of MIQE guidelines was uneven [1]. Despite over 5,977 citations of the original MIQE publication by 2018, compliance remained a challenge [1]. A key finding, however, was that researchers who followed the MIQE guidelines had better chances of publishing in higher-impact, highly-cited journals [1]. This demonstrated a clear value proposition for adherence to the standards.

Commercial manufacturers also responded by aligning their products with MIQE. Bio-Rad created a mobile app for tracking MIQE checklist compliance, and New England Biolabs designed their "Dots in Boxes" qPCR systems around the guidelines [3]. Furthermore, Thermo Fisher Scientific provided resources for their TaqMan assays to facilitate compliance with MIQE sequencing disclosure requirements [6].

Table: Key Milestones in the Development and Adoption of MIQE Guidelines

| Year | Milestone | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Paper claims measles virus detection in autism with RT-qPCR | Later found unreproducible; catalyzed MIQE creation [3] |

| 2009 | Original MIQE guidelines published in Clinical Chemistry | Established first minimum standards for qPCR experiments [4] |

| 2010 | MIQE précis published | Provided simplified, abridged guidelines for routine reporting [2] |

| 2013 | dPCR MIQE guidelines released | Extended principles to digital PCR technology [3] |

| 2014-2017 | Bustin notes ongoing reproducibility issues | Highlighted continued need for stricter adherence [3] |

| 2020 | 10th anniversary analysis shows MIQE papers have higher impact | Demonstrated value of compliance via higher CiteScores [1] |

| 2024/2025 | MIQE 2.0 guidelines announced | Updated recommendations for modern technologies and applications [5] |

Essential MIQE Components: A Researcher's Checklist

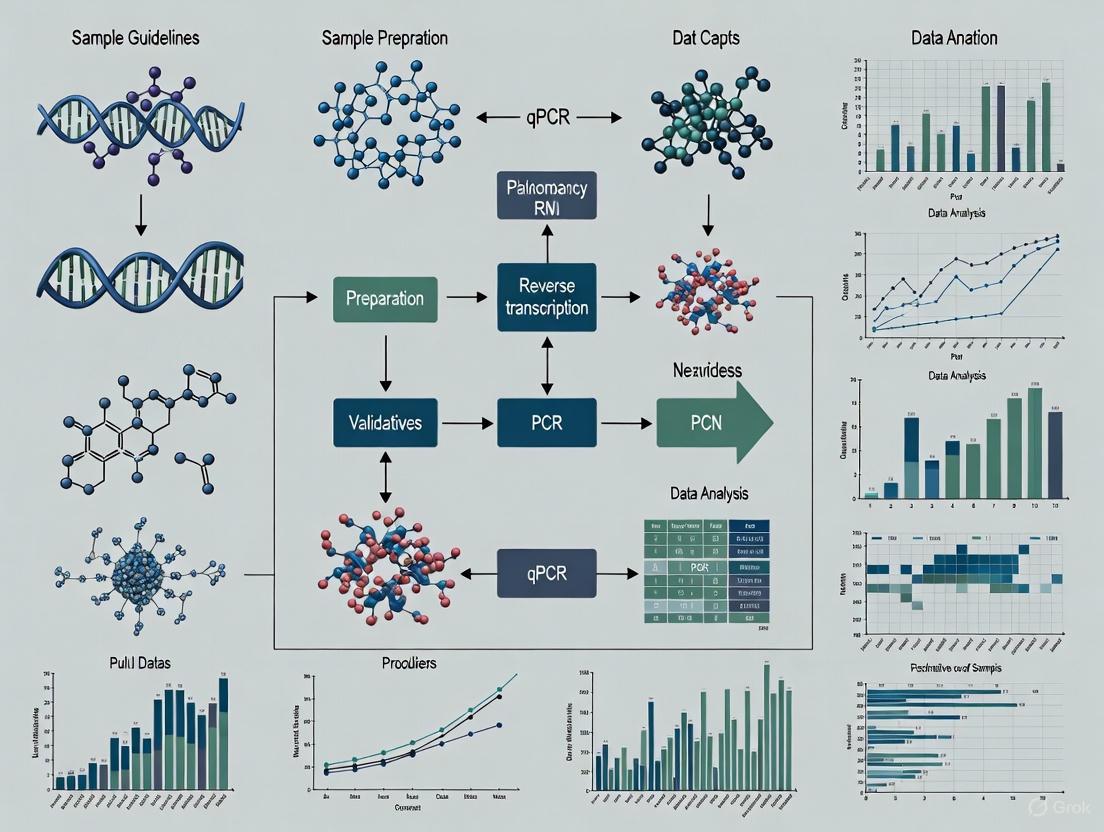

The MIQE guidelines are organized into several critical sections that form the backbone of a reliable qPCR experiment. The following workflow outlines the essential components and their relationships:

Sample and Nucleic Acid Integrity

The foundation of any reliable qPCR experiment begins with proper sample handling. Essential information includes a detailed description of the sample, dissection methods, processing procedures, and storage conditions [3]. For RNA templates, it is critical to report the RNA integrity number (RIN) or similar quality indicators, as comparing degraded and intact RNA yields misleading results [3] [2]. Furthermore, the absence of inhibitors must be tested using either an "alien" spike or a dilution series [2].

Assay Design and Validation

This is a cornerstone of MIQE compliance. Researchers must provide database accession numbers, amplicon size, and primer sequences for each target [2]. For newly designed assays, primer specificity must be validated both in silico (e.g., BLAST analysis) and empirically (e.g., via sequencing or melt curve analysis) [2]. Perhaps most critically, the PCR efficiency of each assay must be determined using a calibration curve, with reported slope, y-intercept, and correlation coefficient [3] [2]. The dynamic range and the limit of detection (LOD) should also be established [3].

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Protocol

The reverse transcription step requires full disclosure of reaction conditions, including the amount of RNA, primer type and concentration, reverse transcriptase used, and incubation times [3]. The qPCR protocol itself must detail all reaction conditions, reagents (including kits and manufacturers), and thermocycling parameters [3].

Data Analysis and Normalization

The final, and often most variable, phase is data analysis. MIQE mandates specifying the software and method used for quantification cycle (Cq) determination [3]. A crucial requirement is the justification for the choice and number of reference genes used for normalization, which must be experimentally validated for the specific experimental conditions [3] [2]. Normalization against a single, unvalidated reference gene is strongly discouraged. The handling of outliers and the statistical methods for evaluating precision must also be transparently reported [3] [2].

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant qPCR

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in MIQE Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Quantification Kits | Applied Biosystems TaqMan Assays | Provide unique Assay ID and amplicon context sequence for full disclosure [6] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Various manufacturer kits | Enable standardized cDNA synthesis; requires reporting of all components and conditions [3] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green I mixes, probe-based mixes | Core reaction components; concentration and manufacturer must be reported [3] |

| RNA Integrity Tools | Bioanalyzer systems, RIN algorithms | Assess sample quality (e.g., RIN/RQI values) to ensure comparable RNA integrity [2] |

| Oligonucleotide Design Tools | Primer design software, BLAST | Ensures specific assay design; requires reporting of in silico validation methods [2] |

| Data Analysis Software | Specialist qPCR analysis programs | Facilitates efficiency calculation, Cq determination, and outlier identification [3] [2] |

Fifteen years after their introduction, the MIQE guidelines have made an undeniable contribution to improving the trustworthiness, consistency, and transparency of published qPCR results [7]. They were born from a necessity to rescue a fundamental laboratory technique from a crisis of irreproducibility, triggered by a high-profile failure to detect measles virus in autism research. While challenges related to awareness, resources, and publication pressures continue to affect consistent application, the evidence is clear: MIQE compliance correlates with higher quality publications [1].

The philosophy underpinning MIQE is not one of restrictive bondage but of liberation from avoidable error. As the technology evolves with new applications in diagnostics, treatment, and basic research, the principles of MIQE—rigor, transparency, and reproducibility—remain as relevant as ever. The forthcoming MIQE 2.0 guidelines [5] promise to refine these principles for the next generation of qPCR applications, ensuring that this cornerstone molecular biology technique continues to yield reliable and impactful scientific discoveries.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) stands as one of the most pivotal technologies in molecular biology, forming the backbone of research and clinical diagnostics worldwide. The reliability of qPCR data, however, is entirely dependent on methodological rigor. To address this, the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines were established in 2009 to standardize the reporting and execution of qPCR experiments. After 16 years of widespread adoption and over 17,000 citations, an international consortium of experts has published MIQE 2.0 in 2025, a significant revision designed to address emerging technologies and applications [8] [9]. This in-depth technical guide explores the key advancements between these two versions, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear framework for implementing these updated standards in qPCR validation research.

The Evolution of MIQE: From 2009 to 2025

The original MIQE guidelines, published in Clinical Chemistry in 2009, were created to combat the troubling lack of reproducibility and transparency in qPCR-based publications [5]. They provided the scientific community with a standardized checklist of essential information required to assess and verify qPCR results. Their influence has been profound, shaping journal editorial policies and even contributing to the development of ISO standards for molecular diagnostics [8].

However, the technology and applications of qPCR have expanded dramatically into new domains. This evolution, coupled with persistent deficiencies in the quality of published qPCR data—a problem starkly highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic—necessitated a comprehensive update [8] [9]. MIQE 2.0, therefore, is not a mere revision but a critical response to the urgent need for enhanced reliability in molecular data that underpins decisions in biomedicine, pharmacology, and public health [8].

Core Conceptual Advancements in MIQE 2.0

The transition from MIQE to MIQE 2.0 reflects a shift in philosophy from establishing basic reporting standards to enforcing deeper methodological rigor and data integrity in the face of modern challenges.

- Emphasis on Reproducibility Over Speed: MIQE 2.0 confronts a persistent "complacency" surrounding qPCR, where the technique is often treated as an infallible "black box" [8] [9]. The updated guidelines reinforce that without full methodological rigor, data cannot be trusted, asserting that "if the data cannot be reproduced, they are not worth publishing" [9].

- Addressing Emerging Applications: The original MIQE was primarily geared toward gene expression analysis. MIQE 2.0 explicitly extends its scope to cover the complexities of new qPCR applications, such as advanced molecular diagnostics, requiring the entire workflow to adapt accordingly [8] [5].

- Streamlined and Clarified Reporting: While promoting completeness, MIQE 2.0 aims to reduce the burden on researchers by simplifying and clarifying reporting requirements. The goal is to encourage comprehensive disclosure without being unduly onerous, thus promoting wider adoption and more robust science [5].

The following table summarizes the major technical updates and advancements introduced in the MIQE 2.0 guidelines.

Table 1: Key Technical Differences Between MIQE (2009) and MIQE 2.0 (2025)

| Aspect | MIQE (2009) | MIQE 2.0 (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Focus | Established baseline reporting standards for qPCR experiments. | Enhances rigor for emerging applications; promotes a cultural shift towards transparency [8] [5]. |

| Data Analysis & Reporting | Emphasized reporting Cq (Ct) values and basic efficiency calculations. | Mandates conversion of Cq values into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reporting with prediction intervals. Requires disclosure of detection limits and dynamic range for each target [5]. |

| Raw Data | Encouraged provision of raw data. | Strongly encourages instrument manufacturers to enable raw data export to allow for independent re-analysis [5]. |

| Assay Validation | Outlined core validation parameters. | Provides clearer and more detailed recommendations for assay design, validation, and in-silico analysis tailored to modern applications [8] [5]. |

| Sample Handling & Technology | Covered sample handling and nucleic acid quality. | Explicitly explains how the entire qPCR workflow must adapt to new technologies, reagents, and consumables [5]. |

| Normalization | Established the importance of using validated reference genes. | Outlines strengthened best practices for normalization and quality control, criticizing the use of unvalidated reference genes [8] [9]. |

Detailed Methodologies for qPCR Assay Validation

Adherence to MIQE 2.0 requires rigorous validation of qPCR assays. The following detailed protocols are essential for generating trustworthy data, particularly in a drug development context.

Determining Amplification Efficiency and Dynamic Range

Purpose: To ensure the qPCR assay amplifies target DNA with high and consistent efficiency across a defined concentration range, which is fundamental for accurate quantification [10].

Protocol:

- Prepare a standard curve using a commercial standard or a sample of known concentration [10].

- Create a serial dilution series spanning at least 6 to 8 orders of magnitude (e.g., seven 10-fold dilutions) [10].

- Run each dilution in triplicate on the qPCR instrument.

- Plot the log of the starting template quantity against the Cq value obtained for each dilution.

- From the slope of the standard curve, calculate the amplification efficiency using the formula: ( E = (10^{-1/slope} - 1) \times 100\% ).

- MIQE 2.0 Compliance: The calculated efficiency must be between 90% and 110%, and the linearity of the standard curve (R²) should be ≥ 0.980 to be considered acceptable. The dynamic range defined by this curve must be reported [10].

Assessing Inclusivity and Exclusivity (Cross-reactivity)

Purpose: To verify that the assay reliably detects all intended target variants (inclusivity) and does not amplify non-targets (exclusivity), which is critical for diagnostic specificity and sensitivity [10].

Protocol:

- Inclusivity Testing:

- In-silico Analysis: Using genetic databases, check that the oligonucleotide, probe, and amplicon sequences are complementary to all known strains/isolates of the target. For example, an influenza A assay must be checked against H1N1, H3N2, etc. [10].

- Experimental Validation: Test the assay against a panel of up to 50 well-defined, certified strains that represent the genetic diversity of the target organism. The assay must produce a positive signal for all [10].

- Exclusivity Testing:

- In-silico Analysis: Check for sequence similarities between the assay oligonucleotides and genetically related non-target organisms (e.g., ensuring an influenza A assay does not match influenza B sequences) [10].

- Experimental Validation: Test the assay against a panel of closely related non-target species and common contaminants. The assay must yield no amplification signal from these samples [10].

Establishing Limits of Detection and Quantification

Purpose: To define the lowest amount of target that can be reliably detected (LoD) and accurately quantified (LoQ), which is essential for assessing assay sensitivity, especially for low-abundance targets like biomarkers or trace pathogens [10].

Protocol:

- Prepare multiple replicates (e.g., n≥12) of samples with low target concentrations.

- The Limit of Detection (LoD) is defined as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of replicates test positive [10].

- The Limit of Quantification (LoQ) is defined as the lowest concentration at which the target can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy, typically with a coefficient of variation (CV) < 25-35% [10].

- MIQE 2.0 Compliance: Both the LoD and LoQ must be determined and reported for each target, as these values are now explicit requirements under the updated guidelines [5].

The qPCR Experimental Workflow under MIQE 2.0

The following diagram illustrates the critical stages of a qPCR experiment, highlighting key control points mandated by the MIQE 2.0 guidelines to ensure data reliability and reproducibility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of MIQE 2.0-compliant qPCR requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details key components for robust assay validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Item | Function & Importance in Validation | MIQE 2.0 Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Samples with known, certified concentrations of the target used to generate standard curves for determining efficiency, dynamic range, LoD, and LoQ [10]. | Essential for traceable and accurate quantification. The source and provenance of standards must be documented. |

| Validated Primer/Probe Sets | Oligonucleotides designed for high specificity and efficiency. Predesigned assays (e.g., TaqMan) must be properly annotated. | Must provide the Assay ID and amplicon context sequence for full compliance [6]. In-house designs require full in-silico and experimental validation. |

| Nucleic Acid Quality Assessment Kits | Kits (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) to quantitatively assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DNA Integrity Number (DIN). | Mandatory for reporting sample quality. Prevents inaccurate results from degraded samples [8] [9]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | High-efficiency enzymes for cDNA synthesis in RT-qPCR. | A major source of variability. The enzyme and reaction conditions must be specified to ensure reproducibility [8]. |

| Validated Reference Gene Panels | A set of candidate reference genes tested for stable expression under specific experimental conditions. | Prevents normalization errors. Genes must be validated for stability; using a single, unvalidated "housekeeping" gene is unacceptable [8] [9]. |

The advent of MIQE 2.0 represents a pivotal evolution in the standards governing quantitative PCR. It moves beyond the foundational reporting framework of the original MIQE to address the pressing need for unwavering methodological rigor in an era of expanded qPCR applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting MIQE 2.0 is not merely about complying with a publication checklist; it is about embracing a culture of transparency and robustness that is fundamental to generating trustworthy data. The credibility of molecular diagnostics and the integrity of the research that supports it now depend on the collective will to implement these updated guidelines as a standard in practice, not just in name [8] [9]. By integrating the detailed protocols, workflows, and reagent considerations outlined in this guide, scientists can ensure their qPCR data are robust, reproducible, and reliable, thereby upholding the highest standards of scientific inquiry.

The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines are a standardized framework designed to ensure the integrity, consistency, and transparency of quantitative PCR (qPCR) results [4]. Established in 2009 and recently updated, these guidelines provide a set of core principles that are critical for advancing reproducible science [4] [5]. The necessity for such guidelines arose from a widespread lack of consensus on how to optimally perform and interpret qPCR experiments, a problem exacerbated by insufficient experimental detail in many publications, which impedes critical evaluation and replication of results [4]. The core principles of Transparency, Standardization, and Reproducibility form the foundation of the MIQE guidelines. By mandating comprehensive disclosure of all relevant experimental conditions, reagents, and analysis methods, the guidelines empower reviewers and other scientists to assess the validity of the protocols used and reproduce the findings with confidence [4] [5]. Adherence to MIQE is therefore not merely a bureaucratic hurdle for publication; it is a fundamental practice for ensuring the reliability and credibility of scientific data in molecular biology, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

The Evolution of MIQE: From 2009 to MIQE 2.0

The MIQE guidelines were first published in 2009 to address the critical lack of standardization in qPCR experiments [4]. The original publication highlighted how the sensitivity of qPCR to subtle experimental variations made it particularly vulnerable to irreproducible results if essential experimental details were omitted [4] [11]. The primary goal was to provide a checklist for authors, reviewers, and editors to ensure that all necessary information was provided to evaluate the quality of qPCR data. The original guidelines successfully established a new norm for rigorous reporting in the field.

Building on this foundation, the MIQE 2.0 guidelines were released to maintain relevance amid technological advancements [5]. The expansion of qPCR into new domains has driven the development of new reagents, methods, and instruments, necessitating revised best practices [5]. MIQE 2.0 incorporates updates, simplifications, and new recommendations tailored to these evolving complexities. A key advancement in MIQE 2.0 is the emphasis on data analysis and reporting. The guidelines now strongly recommend that instrument manufacturers enable the export of raw data to facilitate thorough re-evaluation [5]. Furthermore, they stipulate that quantification cycle (Cq) values should be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reported with prediction intervals [5]. The guidelines also clarify and streamline reporting requirements to encourage comprehensive disclosure without imposing an undue burden on researchers, thereby promoting more rigorous and reproducible qPCR research [5].

Implementing the Core Principles in qPCR Workflows

Principle 1: Transparency

Transparency in MIQE requires the full disclosure of all reagents, sequences, analysis methods, and raw data to enable independent verification of experimental results [4] [5]. This principle is foundational to the scientific method, as it allows for the critical assessment and replication of work. For assay design, this means providing the exact primer and probe sequences or, for commercially available assays like TaqMan, the unique Assay ID and the corresponding amplicon context sequence [6]. Thermo Fisher Scientific supports this by providing an Assay Information File (AIF) for each predesigned assay, which contains the required context sequence [6]. Furthermore, MIQE 2.0 encourages instrument manufacturers to enable the export of raw data files, allowing reviewers and other researchers to perform their own analyses and confirm reported findings [5]. Transparency extends to the analysis phase, where the guidelines recommend reporting Cq values as efficiency-corrected target quantities with associated prediction intervals, rather than just raw Cq values [5]. This level of disclosure ensures that every step of the qPCR process, from sample to result, is open for scrutiny.

Principle 2: Standardization

Standardization involves adhering to consistent, well-defined experimental and analytical protocols across laboratories to minimize technical variability and enable direct comparison of results between different studies [4]. The MIQE guidelines provide a detailed checklist that covers every aspect of a qPCR experiment, creating a common language and set of practices for the field. Key areas for standardization include:

- Sample Quality: Documenting sample collection, storage, and nucleic acid extraction methods, as well as providing quality metrics like RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for RNA samples.

- Assay Validation: For each primer pair, providing information on PCR efficiency, correlation coefficient, and dynamic range [5].

- Data Analysis: Using standardized methods for quantification, such as the efficiency-corrected comparative Cq method, and clearly defining normalization strategies with validated reference genes [5].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow encompassing these standardized steps, from sample preparation to final result reporting, ensuring consistency and reliability throughout the qPCR process.

Principle 3: Reproducibility

Reproducibility is the ultimate goal of the MIQE guidelines, ensuring that experiments can be reliably repeated within the same laboratory and independently verified by other research groups [4]. Reproducibility is achieved through the combined application of transparency and standardization. Key to this is the comprehensive reporting of experimental details, which allows other scientists to recreate the exact conditions of the experiment. The guidelines emphasize that full disclosure of all reagents, sequences, and analysis methods is necessary to enable other investigators to reproduce results [4]. MIQE 2.0 further strengthens this by outlining best practices for normalization and quality control, and by requiring that detection limits and dynamic ranges for each target are reported based on the chosen quantification method [5]. A novel experimental design proposed in research, which uses dilution-replicates instead of identical replicates, can also enhance reproducibility by allowing for more robust estimation of PCR efficiency across all test samples, thereby accounting for inter-run variation without the need for a common control in every run [11]. This design takes advantage of the fact that each qPCR reaction yields a Cq value reflecting both initial target gene quantity and reaction efficiency, providing a more resilient framework for obtaining consistent results [11].

Experimental Design and Analysis Protocols

Efficient Experimental Design with Dilution Replicates

Traditional qPCR experimental design involves running multiple identical replicates of each sample to account for technical variation, alongside separate standard curves on diluted samples to determine PCR efficiency for each primer pair. However, this approach can be costly and labor-intensive, especially with a large number of samples and targets [11]. An efficient alternative design employs dilution-replicates instead of identical replicates [11]. In this design, a single reaction is performed on several dilutions for every test sample, similar to a standard curve but without identical replicates at each dilution [11]. This design is based on the mathematical relationship of the qPCR amplification curve, described by the equation:

Cq = -log(d)/log(E) + log(T/Q(0)) / log(E) [11]

Where:

- Cq is the quantification cycle

- d is the dilution factor

- E is the PCR efficiency

- T is the threshold

- Q(0) is the initial quantity

A plot of Cq versus log(d) produces a straight line with a slope of -1/log(E), from which efficiency (E) can be calculated. The y-intercept, log(T/Q(0)) / log(E), provides an estimate of the initial quantity, Q(0) [11]. This means that each sample's dilution series simultaneously provides an estimate of both the PCR efficiency and the initial target quantity, eliminating the need for separate efficiency determination. This design can result in fewer total reactions while also providing a built-in mechanism to identify and exclude outliers from the analysis, as anomalies at high dilutions become apparent in the standard curve plot [11].

Robust Data Analysis and Efficiency Estimation

Accurate data analysis is critical for reliable qPCR results. The MIQE 2.0 guidelines emphasize that Cq values should be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reported with prediction intervals [5]. This is crucial because small variations in the estimated PCR efficiency (E) can lead to large errors in the calculated initial quantity. For example, a 0.05 error in E (where E=2 represents 100% efficiency) can result in a 53–110% misestimate of the initial quantity after 30 cycles [11]. The dilution-replicate experimental design enables a robust method for efficiency estimation called the collinear fit of standard curves [11]. By assuming that the PCR efficiency for a given primer pair is constant across all samples, the standard curves from all samples can be fit simultaneously with the constraint of equal slopes. This provides a globally estimated PCR efficiency (E) with a high degree of freedom, making it more accurate and reliable than estimates from a single, separately run standard curve [11]. This global efficiency is then used to calculate the efficiency-corrected relative quantities for each sample, leading to more robust and reproducible gene expression quantification. The following table summarizes the key differences between the traditional and dilution-replicate experimental designs.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Dilution-Replicate qPCR Experimental Designs

| Aspect | Traditional Design | Dilution-Replicate Design |

|---|---|---|

| Replicate Strategy | Multiple identical replicates per sample [11] | Multiple dilutions per sample (dilution-replicates) [11] |

| Efficiency (E) Determination | Separate standard curves from 2-3 independent samples [11] | Estimated from each sample's dilution series [11] |

| Handling of Inter-Run Variation | Requires a common control sample in each run [11] | Built-in efficiency estimation in each run makes a common control less critical [11] |

| Outlier Management | Difficult; may require repeating entire reactions [11] | Easier; outliers can be identified in the standard curve plot and excluded [11] |

| Total Number of Reactions | Can be high due to technical replicates and separate standard curves [11] | Can be reduced by integrating efficiency estimation into sample analysis [11] |

Successful and MIQE-compliant qPCR experiments rely on a suite of essential reagents and resources. The following table details key components of the research reagent solutions, their specific functions, and their role in adhering to the core principles of the MIQE guidelines.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant qPCR

| Reagent / Resource | Function | MIQE Compliance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Nucleic Acids | Template for the qPCR reaction. | Sample quality and integrity must be documented (e.g., with RIN for RNA). Foundational for reproducibility [4] [5]. |

| Validated Primers & Probes | Sequence-specific amplification and detection. | Transparency requires disclosure of sequences or Assay ID with context sequence [6]. Assays must be validated for efficiency and dynamic range [5]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | For RNA templates, synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA). | The kit and reaction conditions must be fully reported to ensure standardization and reproducibility [4]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, buffers, and salts for efficient amplification. | The specific master mix and volume used in the reaction must be stated to enable experimental replication [4] [6]. |

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned, optimized assays for specific targets. | Provide a unique Assay ID; the associated amplicon context sequence is provided for full sequence disclosure compliance [6]. |

| Assay Information File (AIF) | Document provided with TaqMan assays. | Contains the amplicon context sequence, essential for complying with MIQE guidelines on assay sequence disclosure [6]. |

The relationships between these core components and the MIQE principles are visualized in the following diagram, which shows how standardized reagents and transparent reporting converge to generate reproducible results.

The MIQE guidelines, built upon the core principles of Transparency, Standardization, and Reproducibility, provide an indispensable framework for conducting and reporting rigorous qPCR experiments. From their initial introduction to the recent MIQE 2.0 update, these guidelines have evolved to address the complexities of modern qPCR applications, offering clear recommendations for sample handling, assay validation, and data analysis [4] [5]. By diligently following these guidelines, researchers can avoid common pitfalls that lead to irreproducible results, thereby ensuring the integrity of their data and the credibility of their conclusions. The adoption of efficient experimental designs, such as the dilution-replicate method, and robust analysis techniques, like global efficiency calculation, further enhances the reliability of qPCR findings [11]. Ultimately, the consistent application of the MIQE principles across basic research and drug development is not just about meeting publication requirements—it is a fundamental commitment to scientific excellence and the advancement of reliable knowledge.

The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines establish a standardized framework for the design, execution, and reporting of qPCR assays, with the primary goal of ensuring the reproducibility and credibility of experimental results [6]. In 2025, the MIQE 2.0 revision was published to address the expansion of qPCR into new domains and the development of new reagents, methods, and instruments [5]. Transparent, clear, and comprehensive description of all experimental details is necessary to ensure the repeatability and reproducibility of qPCR results [5]. Non-compliance with these guidelines poses a significant threat to data integrity, leading to irreproducible findings, wasted resources, and erroneous conclusions that can misdirect scientific progress and clinical decision-making.

This guide outlines the concrete consequences of non-compliance, provides validated protocols to adhere to MIQE standards, and presents a practical toolkit for researchers to safeguard the integrity of their qPCR data.

The Consequences of Non-Compliance

Failure to adhere to MIQE guidelines can lead to catastrophic failures in data interpretation at multiple levels, from basic research to clinical application.

Scientific and Clinical Consequences

- Irreproducible Results and Retractions: The powerful, exponential nature of PCR amplification means that without proper validation, minor contaminants or assay inefficiencies can be dramatically amplified, leading to false results. Historically, this has led to severe misinterpretations, such as the erroneous belief in the 1990s that DNA had been extracted from dinosaur bones, when in fact modern contaminating DNA was being amplified [10].

- Misdiagnosis and Poor Patient Management: In a clinical context, an unvalidated qPCR assay can have direct consequences for patient care. For example, a test for influenza A that lacks proper inclusivity validation might fail to detect the H3N2 variant, leading to misdiagnosis. Similarly, if exclusivity (cross-reactivity) is not validated, an influenza A assay might also detect influenza B, causing patients infected with influenza B to be misdiagnosed as positive for influenza A [10].

- Stalled Drug Development and Wasted Resources: The misuse of qPCR in clinical and pre-clinical research can result in investing millions of dollars in a drug candidate that only seemed promising due to faulty qPCR data [10]. This wastes immense resources and delays the development of effective therapies.

Economic and Regulatory Costs

The economic impact of non-compliance extends beyond wasted research funds.

- Direct Financial Costs: Core facilities charge substantial set-up fees to cover the necessary regulatory, quality control, and validation work required for compliant qPCR services. For instance, an annual viral load set-up fee per target can be over $5,000 for internal academic users and over $8,000 for external users [12]. These costs represent the minimal investment for generating reliable data; skipping this validation leads to far greater costs downstream.

- Regulatory Rejection: Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA recommend qPCR for critical safety assessments of gene and cell therapies, such as biodistribution and vector shedding studies [13]. However, a guidance void exists for parameters like accuracy, precision, and repeatability, leading to conflicting institutional interpretations. A lack of consensus on "best practices" for assay validation can result in regulatory rejection of submitted data [13]. The lack of technical standardization remains a huge obstacle in the translation of qPCR-based tests from research to the clinic [14].

Table 1: Economic Costs of qPCR Compliance vs. Non-Compliance

| Aspect | Compliance Cost (Investment) | Non-Compliance Cost (Consequence) |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Setup | ~$5,265 annual set-up fee per target [12] | Data rejection by regulators; need for complete re-analysis |

| Sample Analysis | ~$230 per clinical sample for 5 targets [12] | Misdiagnosis leading to patient mismanagement and liability |

| Research & Development | Investment in robust validation protocols | Wasted millions on misguided drug candidates [10] |

| Publication | Transparent reporting of all MIQE elements | Retraction of publications; loss of scientific credibility |

Essential Methodologies for MIQE-Compliant qPCR

Core Validation Parameters and Protocols

To avoid the consequences of non-compliance, key assay performance characteristics must be rigorously validated.

Table 2: Essential qPCR Validation Parameters and Protocols

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusivity | Assess the ability to detect all intended target strains/isolates. Test against a panel of up to 50 well-defined (certified) strains reflecting the genetic diversity of the target species. Perform both in silico analysis (checking sequence databases) and experimental validation [10]. | The assay must reliably detect all target variants (e.g., Influenza A H1N1, H1N2, H3N2) without failure [10]. |

| Exclusivity (Cross-reactivity) | Assess the ability to exclude genetically similar non-targets. Test against a panel of common cross-reactive species that are not of interest. Perform both in silico analysis and experimental bench testing [10]. | The assay must not amplify non-targets (e.g., an Influenza A assay must not amplify Influenza B) [10]. |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Prepare a seven 10-fold dilution series of a DNA standard of known concentration, run in triplicate. Plot the resulting Ct values against the logarithm of the template concentration [10]. | The plot should fit a straight line over 6–8 orders of magnitude. Linearity (R²) values of ≥ 0.980 are typically acceptable [10]. |

| Amplification Efficiency (E) | Calculate from the slope of the standard curve generated in the linear dynamic range experiment using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [13]. | A slope between -3.6 and -3.1, corresponding to an efficiency of 90%–110%, is generally acceptable [13]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) / Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Determine the minimum detectable concentration (LOD) and the minimum concentration that can be accurately quantified (LOQ) through serial dilution of the target [10]. | LOD and LOQ must be established and reported for each target, based on the chosen quantification method [5]. |

Data Analysis and Reporting Standards

MIQE 2.0 provides updated and clarified recommendations for data analysis and reporting to ensure transparency.

- Raw Data: Instrument manufacturers are encouraged to enable the export of raw data to facilitate thorough analyses and re-evaluation by manuscript reviewers and other researchers [5].

- Cq Value Conversion: Quantification cycle (Cq) values should not be reported as an endpoint. They must be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reported with prediction intervals [5].

- Normalization: Best practices for normalization and quality control are outlined, and reporting requirements have been clarified and streamlined to encourage researchers to provide all necessary information without undue burden [5].

- Assay Disclosure: To fully comply with MIQE guidelines, providing the probe or amplicon context sequence is required in addition to a unique assay identifier. For commercially available assays like TaqMan, the Assay Information File (AIF) contains this required context sequence [6].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the critical path for establishing a MIQE-compliant qPCR assay, highlighting key decision points and validation steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents and understanding their function is fundamental to generating reliable data.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for qPCR Validation

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probe | Binds specifically to the target DNA sequence for amplification and detection. The probe contains a reporter dye for real-time detection [13]. | Design and test at least three unique sets. Probe-based qPCR (e.g., TaqMan) offers superior specificity over dye-based methods (e.g., SYBR Green) [13]. |

| Master Mix | Provides the optimal buffer, salts, dNTPs, and DNA polymerase for efficient amplification [13]. | Use a master mix compatible with your chemistry (probe vs. dye). A hot-start enzyme is often recommended to reduce non-specific amplification. |

| Reference Standard DNA | A sample of known concentration used to generate the standard curve for absolute quantitation of target copy number [13]. | Should be highly pure and accurately quantified. Used to define the linear dynamic range and calculate amplification efficiency [10] [13]. |

| Matrix/Background DNA | Genomic DNA extracted from naive (untreated) animal tissues. Added to standard and QC samples to mimic the composition of actual biodistribution samples [13]. | Ensures that the PCR efficiency calculated from the standard curve is representative of the efficiency in the sample context, checking for inhibition [13]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Serves as the solvent for reactions, ensuring no enzymatic degradation of reagents. | Critical for preventing the degradation of primers, probes, and templates, which would compromise sensitivity and efficiency. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known copy numbers run alongside unknowns on every qPCR plate to monitor inter-assay precision and accuracy. | Typically include high, mid, and low concentration QCs. They are essential for validating each run [13]. |

Adherence to MIQE guidelines is not a bureaucratic hurdle but a fundamental prerequisite for data integrity in qPCR research. The high cost of non-compliance—manifesting as irreproducible science, clinical misdiagnoses, and massive financial waste—far outweighs the investment in rigorous assay validation. As qPCR technology continues to evolve and find new applications, the principles enshrined in MIQE 2.0 provide a critical roadmap for researchers to generate reliable, trustworthy data that can confidently advance scientific knowledge and patient care.

Implementing MIQE: A Step-by-Step Guide to qPCR Assay Design and Execution

In the framework of the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines, the integrity of the initial sample and the extracted nucleic acids is not merely a preliminary step but the foundational determinant of experimental success [4] [6]. The MIQE guidelines were established to address a lack of consensus and insufficient experimental detail in qPCR publications, thereby ensuring the reliability, integrity, and reproducibility of results [4]. Within this context, the pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, nucleic acid extraction, and quality assessment—is critical. High-quality nucleic acid preparation is universally acknowledged as the single most important step for ensuring successful PCR [15]. Contaminants or degradation at this stage can irreversibly compromise data fidelity, leading to inaccurate quantification and erroneous biological conclusions. This guide details the protocols and metrics essential for validating sample and nucleic acid integrity, aligning with the rigorous reporting standards mandated by MIQE for qPCR validation research.

Nucleic Acid Quality Assessment: Quantitative Metrics and Methods

The assessment of nucleic acid quality involves specific quantitative benchmarks. Adherence to these metrics is a core requirement for MIQE-compliant reporting, providing reviewers and other scientists with the necessary information to evaluate the validity of the protocols used [4].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Nucleic Acid Quality Assessment

| Metric | Target Value for High Quality | Measurement Technique | Interpretation and Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 Ratio | 1.8 - 2.0 [15] | UV Spectrophotometry | Indicates protein contamination. A ratio significantly lower than 1.8 suggests residual phenol or protein, while a ratio higher than 2.0 may indicate RNA contamination in a DNA sample or solvent issues. |

| A260/A230 Ratio | > 2.0 | UV Spectrophotometry | Suggests the presence of contaminants such as salts, EDTA, or carbohydrates. A low ratio can signal the presence of reaction inhibitors. |

| PCR Efficiency | 90% - 110% [16] | qPCR Standard Curve | Calculated via a standard curve of serial dilutions. Efficiency outside this range can lead to inaccurate quantification and must be reported. Lower efficiencies suggest the presence of inhibitors or poor assay design. |

For RNA expression analysis via RT-qPCR, the process begins with extracting high-quality RNA and reverse transcribing it to complementary DNA (cDNA) [17]. The integrity of the RNA template is paramount for the reverse transcription enzyme to produce a cDNA yield that is both high and proportional to the starting RNA amount, ensuring accurate downstream quantification [15]. Furthermore, when the starting material is RNA, specific steps like DNase I treatment are recommended to reduce potential false-positive signals from genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination [15].

Experimental Protocols for Integrity Verification

Protocol: Assessment of Nucleic Acid Purity via Spectrophotometry

Principle: This method utilizes UV absorbance to quantify nucleic acid concentration and detect common contaminants based on their specific absorbance profiles.

Materials:

- Purified DNA or RNA sample

- UV-transparent cuvette

- UV/Vis Spectrophotometer

- Nuclease-free water (diluent)

Methodology:

- Blank the spectrophotometer using nuclease-free water.

- Dilute a small aliquot (typically 1-2 µL) of the nucleic acid sample in nuclease-free water. A 1:20 or 1:50 dilution is often appropriate.

- Measure the absorbance at 230 nm, 260 nm, and 280 nm.

- Record the values and calculate the following:

- Nucleic Acid Concentration: For DNA, A260 of 1.0 ≈ 50 µg/mL. For RNA, A260 of 1.0 ≈ 40 µg/mL.

- Purity Ratios: A260/A280 and A260/A230.

Data Interpretation: Compare the calculated ratios to the target values listed in Table 1. Any significant deviation indicates potential contamination that must be addressed before proceeding with qPCR.

Protocol: Validation of PCR Efficiency

Principle: PCR amplification efficiency is calculated from a standard curve generated by serially diluting a known amount of DNA template [16]. This is a critical assay validation step required by MIQE.

Materials:

- Template DNA (or cDNA) of known concentration

- qPCR master mix (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan)

- Target-specific primers

- Real-time PCR instrument

Methodology:

- Prepare a stock solution of your DNA template and then create a serial dilution series (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10000) [16].

- Perform qPCR for each dilution, ideally with three technical replicates.

- The qPCR instrument software will plot the log of the starting template quantity (or its dilution factor) against the Ct (Threshold Cycle) value for each dilution.

- Obtain the slope of the resulting standard curve.

Calculation:

- Apply the slope to the efficiency formula [16]:

Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) x 100

Interpretation: An efficiency between 90% and 110% is considered acceptable [16]. Lower values suggest inhibition or suboptimal reaction conditions, while values exceeding 110% may indicate pipetting errors, inhibitor presence, or non-specific amplification.

Workflow Diagram: From Sample to Quantifiable Data

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for ensuring sample and nucleic acid integrity, from collection to the final verifiable data, incorporating key quality control checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Integrity

| Item | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades trace amounts of genomic DNA during RNA purification. This step is crucial for preventing false-positive signals in gene expression analysis (RT-qPCR) [15]. |

| URacil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) | An enzyme used in qPCR master mixes to prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR products. It cleaves DNA strands containing dUTP (which is incorporated in place of dTTP), which are then unable to be amplified [15]. |

| Hot-Start Taq DNA Polymerase | A modified polymerase that remains inactive at room temperature. This prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup, thereby improving assay specificity, sensitivity, and overall efficiency [15]. |

| ROX Passive Reference Dye | A dye included in some qPCR master mixes to normalize for non-PCR-related fluctuations in fluorescence between wells. This corrects for pipetting inaccuracies or well-to-well volume differences and is required for certain instrument platforms [15]. |

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned probe-based assays that provide high specificity by utilizing a gene-specific probe in addition to primers. They are available with detailed annotation and amplicon context sequences, facilitating compliance with MIQE guidelines on assay disclosure [6]. |

Within the MIQE framework, the journey to robust and publishable qPCR data unequivocally begins at the very first step: safeguarding sample and nucleic acid integrity. By meticulously following the documented protocols for quality assessment, rigorously validating PCR efficiency, and fully disclosing all relevant experimental conditions as outlined in the MIQE checklist, researchers can ensure the credibility and reproducibility of their findings. This commitment to rigor from sample collection onwards is what ultimately fortifies the scientific literature and enables true scientific progress.

Within the framework of MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines, robust quantitative PCR (qPCR) validation research demands assays that are specific, sensitive, and efficient [4] [2]. The exquisite specificity and sensitivity that make qPCR a powerful technique are fundamentally controlled by the properties of the primers and probes used [18]. Poor design, combined with a failure to optimize reaction conditions, is a primary source of reduced technical precision and can lead to both false-positive and false-negative results, ultimately compromising the integrity of scientific data [18]. The MIQE guidelines were established to provide a standardized framework for documenting all aspects of qPCR experiments, from sample preparation to data analysis, thereby ensuring the reproducibility and credibility of research findings [6] [4]. This guide details the strategies for achieving optimal primer and probe specificity, a core requirement for any qPCR assay that aims to be MIQE-compliant and yield biologically relevant results.

Core Principles of Primer and Probe Design

The journey to a specific qPCR assay begins with adhering to foundational design principles. These parameters govern the binding efficiency and selectivity of your oligonucleotides, forming the basis for a successful experiment.

Primer Design Guidelines

Primers are the cornerstone of any PCR assay, and their careful design is non-negotiable for specificity. The following table summarizes the key characteristics to target:

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for PCR Primers

| Parameter | Recommended Ideal | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 bases [19] | Balances specificity with adequate melting temperature. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–64°C (ideal 62°C) [19] | Optimized for typical cycling conditions and enzyme function. |

| Tm Difference Between Primers | ≤ 2°C [19] | Ensures both primers bind simultaneously and efficiently. |

| GC Content | 35–65% (ideal 50%) [19] | Provides sufficient sequence complexity while avoiding stable secondary structures. |

| 3' End Sequence | Avoid regions of 4 or more consecutive G residues [19] | Prevents the formation of stable, non-specific G-quadruplex structures. |

Probe Design Guidelines

For hydrolysis probe-based assays (e.g., TaqMan), the probe must meet its own set of criteria to ensure specific detection of the amplicon.

Table 2: Key Design Parameters for qPCR Probes

| Parameter | Recommended Ideal | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Close to, but not overlapping, a primer-binding site [19] | Ensures efficient cleavage by the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of the polymerase. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 5–10°C higher than primers [19] | Guarantees the probe is fully bound before primer extension begins. |

| GC Content | 35–65%; avoid G at the 5' end [19] | Prevents quenching of the 5' fluorophore, which would reduce signal. |

| Quenching | Use of double-quenched probes is recommended [19] | Incorporation of an internal quencher (e.g., ZEN, TAO) lowers background and increases signal-to-noise ratio. |

Amplicon and Target Considerations

The characteristics of the amplified region itself are equally critical for assay specificity.

- Amplicon Length: Typically, 70–150 base pairs are ideal, as this length is easily amplified with standard cycling conditions and provides enough sequence space for designing primers and a probe with appropriate Tm [19].

- Amplicon Location: When working with RNA, design assays to span an exon-exon junction wherever possible. This dramatically reduces the risk of amplifying contaminating genomic DNA [19] [18].

- Target Identification: The first step in assay design is the unambiguous identification of the target sequence using curated databases (e.g., NCBI RefSeq with prefixes like NC, NG, NM_) [18]. It is crucial to account for known splice variants, paralogues, and pseudogenes to ensure the assay amplifies the intended target and nothing else. Always report the database accession number used for design in publications [18].

The Design Workflow: From Sequence to Specific Assay

Achieving a specific and robust assay requires a systematic workflow that combines in silico design with empirical validation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive process.

In Silico Design and Analysis

The initial phase involves computational steps to create and refine candidate oligonucleotides.

- Define Assay Properties: Before designing primers, determine the desired amplicon location and length based on the target transcript and the need to avoid genomic DNA amplification [18].

- Design Oligonucleotides: Use specialized software to generate candidate primers and probes that conform to the guidelines in Tables 1 and 2. The critical variable for primer performance is its annealing temperature (Ta), which must be established experimentally, not solely relied upon from in silico Tm calculations [18].

- Analyze Specificity and Secondary Structures:

- Specificity Check: Perform an in silico specificity check using BLAST to ensure the selected primers are unique to the desired target sequence [19] [2]. However, be aware that BLAST may miss thermodynamically important hybridisation events and is not infallible [18].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Screen all primers and probes for self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins. The free energy (ΔG) for any such structures should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol [19]. Tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer are essential for this purpose.

Experimental Validation and Optimization

A perfect in silico design does not guarantee wet-lab success. Empirical validation is a MIQE-mandated step [2].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Systematically optimize the concentrations of primers and MgCl₂, as well as the annealing temperature [2] [18]. A robust assay will perform well over a broad temperature range, whereas an assay with a narrow optimum is more susceptible to yielding variable results [18].

- Validate Assay Performance:

- Specificity: Validate primer specificity empirically, ideally by DNA sequencing of the amplicon, or at a minimum by gel electrophoresis or analysis of melting curves for SYBR Green assays [2].

- Efficiency and Dynamic Range: Construct a standard curve using a serial dilution (at least 5 orders of magnitude) of a known amount of template [2] [20]. The PCR efficiency is calculated from the slope of the standard curve using the formula: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) x 100 [20]. MIQE-compliant assays should have an efficiency between 90% and 110% [2] [20].

- Sensitivity and Linearity: Report the linear dynamic range and the limit of detection (LOD) based on the standard curve [2].

Successful qPCR assay design and validation rely on a suite of specific reagents and in silico tools. The following table details key resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for qPCR Assay Development

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic amplification of the target sequence. | Often purchased as a master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, and enzyme. |

| Optical Plates/Tubes | Compatible with real-time thermal cyclers for fluorescence detection. | Must be clear and free of auto-fluorescence. |

| Fluorogenic Probes & Dyes | Detection of accumulating amplicon in real-time. | Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan), intercalating dyes (e.g., SYBR Green). |

| Quenching Molecules | Suppress fluorophore emission until probe cleavage. | TAMRA, BHQ; double-quenched probes use an internal quencher (ZEN, TAO) [19]. |

| Primer Design Software | In silico generation and analysis of oligonucleotides. | IDT PrimerQuest, Primer3. |

| Oligo Analysis Tools | Analyze Tm, dimers, hairpins, and secondary structures. | IDT OligoAnalyzer, UNAFold [19]. |

| Sequence Databases | Source of curated target sequences for design. | NCBI RefSeq (e.g., NM_ accessions) [18]. |

| Specificity Check Tools | Verify oligonucleotide specificity against genomic databases. | NCBI BLAST [19]. |

MIQE Compliance: Reporting Your Assay

The MIQE guidelines are not just a laboratory practice but also a publication standard. Full disclosure enables critical evaluation and repetition of experiments [4]. The following diagram outlines the key reporting nodes for primer and probe design within the MIQE framework.

For primer and probe design, the following information is essential for MIQE compliance and should be included in publications, either in the main text or as supplementary data [6] [2]:

- Primer and Probe Sequences: Report the exact sequences and database accession numbers used for design. For commercially predesigned assays (e.g., TaqMan), providing the assay ID is typically sufficient, but the probe or amplicon context sequence must also be available to fully comply with MIQE [6].

- Amplicon Details: Include the amplicon size and location, specifying if it crosses an exon-exon junction [6] [2].

- In Silico Validation: Note the software used for design and the results of specificity checks (e.g., BLAST analysis) [2].

- Empirical Validation Data:

- PCR Efficiency and Linearity: Report the slope, y-intercept, PCR efficiency, and R² of the standard curve [2] [20].

- Specificity Evidence: Describe the method used to confirm specificity (e.g., sequencing, melt curve analysis) [2].

- Dynamic Range and LOD: State the linear dynamic range and the limit of detection [2].

By meticulously following these design strategies and adhering to MIQE reporting standards, researchers can develop qPCR assays with optimal specificity, ensuring the generation of reliable, reproducible, and credible data that advances scientific knowledge.

In the landscape of molecular biology, Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) stands as a cornerstone technique for precise gene expression analysis. Its significance in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development necessitates rigorous standardization to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of generated data. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide this critical framework [5] [9]. Originally published in 2009 and recently revised as MIQE 2.0, these guidelines establish a standardized set of recommendations for the design, execution, and reporting of qPCR experiments [5]. Adherence to MIQE principles is not merely a procedural formality but a fundamental aspect of scientific integrity, designed to combat methodological failures and build a foundation of trusted evidence for research and development decisions [9]. This guide details the essential components and conditions of the RT-qPCR protocol within the context of these vital validation standards.

Core Principles of RT-qPCR and MIQE

The RT-qPCR Workflow

RT-qPCR is a two-step process that first involves the reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by the quantitative amplification of this cDNA [21] [22]. The accuracy of the final quantitative data is contingent upon meticulous attention to every stage of this workflow, from sample acquisition to data analysis.

The Role of MIQE 2.0 Guidelines

The updated MIQE 2.0 guidelines address advances in technology and emerging applications, offering clear recommendations for sample handling, assay design, validation, and data analysis [5]. A core principle is the necessity of transparent and comprehensive reporting of all experimental details to ensure repeatability and reproducibility [5]. MIQE 2.0 emphasizes that quantification cycle (Cq) values should be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reported with prediction intervals [5]. Despite widespread awareness of MIQE, compliance remains patchy, a concerning issue given that qPCR results underpin decisions in diagnostics and public health [9].

Essential Components and Reagents

RNA Template: The Foundational Starting Material

The quality of the RNA template is the single most critical factor for successful RT-qPCR.

- Quality and Integrity: RNA must be free of degradation, which can be assessed via gel electrophoresis (showing intact 28S and 18S ribosomal RNAs with a 2:1 ratio) or more quantitatively using an RNA Integrity Number (RIN), where values of 8-10 indicate high-quality RNA [23].

- Purity Assessment: Absorbance ratios measured by UV spectroscopy are used to evaluate the presence of contaminants. Target ratios are A260/A280 ≈ 2.0 for pure RNA and A260/A230 > 1.8 to indicate minimal organic compound contamination [23]. Fluorometer-based methods (e.g., Qubit assays) offer greater accuracy for quantification [23].

- gDNA Removal: Trace amounts of genomic DNA (gDNA) can cause high background and false positives. Treatment with a DNase is strongly recommended. ezDNase Enzyme is an example of a double-strand-specific DNase that offers a shorter workflow and less risk of RNA damage compared to traditional DNase I [23].

Reverse Transcription (RT) Reagents

The conversion of RNA to cDNA is a potential source of significant technical variation.

- Reverse Transcriptase Selection: Common enzymes include AMV RT, MMLV RT, and engineered MMLV RT (e.g., SuperScript IV). Key differentiators are RNase H activity (lower is better for synthesizing long cDNA), reaction temperature (higher temperatures help denature RNA with secondary structure), and reaction time. Engineered MMLV RT offers low RNase H activity, a high reaction temperature of 55°C, and a short 10-minute incubation [23].

- Primer Selection: The choice of primer for reverse transcription dictates cDNA representation and must be documented per MIQE guidelines.

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Consist of 12-18 deoxythymidines that anneal to the poly(A) tails of eukaryotic mRNAs. Ideal for full-length cDNA cloning but unsuitable for degraded RNA or RNAs without poly(A) tails (e.g., prokaryotic RNA, miRNAs). Can cause 3' end bias [23].

- Random Primers: Typically random hexamers that anneal anywhere on any RNA species. Suitable for degraded RNA, RNAs without poly(A) tails, and RNA with secondary structures. However, they yield shorter cDNA fragments and may overestimate mRNA copy number [23].

- Gene-Specific Primers: Offer the most specific priming but are limited to targeted genes [23]. A mixture of oligo(dT) and random hexamers is often used in two-step RT-qPCR to balance the benefits of each [23].

qPCR Reagents and Detection Chemistry

The qPCR reaction requires careful optimization and validation of its components.

- Master Mix: A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and cations (e.g., Mg2+). Using a commercial master mix saves time and improves reproducibility [24]. The master mix may also include a passive reference dye (e.g., ROX) to normalize for well-to-well signal variance [24].

- Detection Methods: The choice of chemistry balances specificity, cost, and flexibility.

- DNA Intercalating Dyes (e.g., SYBR Green): Bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). They are versatile and cost-effective but require post-amplification melt-curve analysis to confirm amplification specificity, as they will detect any dsDNA, including primer-dimers [25] [24] [22].

- Hydrolysis Probes (e.g., TaqMan Probes): Target-specific oligonucleotides with a 5' fluorescent reporter and a 3' quencher. The DNA polymerase's 5' exonuclease activity cleaves the probe during amplification, separating the reporter from the quencher and generating fluorescence. This method offers high specificity and enables multiplexing (detecting multiple targets in one reaction) but requires custom probe design [25] [22].

- Other Probe Types: Molecular beacons (hairpin-shaped probes) and locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes (with increased thermal stability) offer alternative high-specificity options [22].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | SuperScript IV, AMV RT | Synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template | RNase H activity, reaction temperature, processivity |

| RT Primers | Oligo(dT), Random Hexamers, Gene-Specific | Initiates cDNA synthesis from the RNA template | Defines cDNA representation; choice depends on RNA type and application |

| qPCR Master Mix | TaqMan Fast Advanced, SYBR Green Supermix | Provides core components for DNA amplification | Includes polymerase, dNTPs, buffer; may include dye or reference dye |

| Detection Chemistry | SYBR Green, TaqMan Probes | Generates fluorescent signal proportional to amplicon production | Specificity (probes) vs. flexibility (dyes); cost and multiplexing capability |

| gDNA Removal | DNase I, ezDNase Enzyme | Eliminates contaminating genomic DNA | Prevents false-positive amplification; specificity for dsDNA is beneficial |

Detailed Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Reverse Transcription Reaction

- Template Preparation: Use 10 ng–1 µg of high-quality, DNase-treated total RNA. The input amount should be consistent across samples and justified [23] [26].

- Reaction Setup: In a nuclease-free tube, combine RNA template, reverse transcriptase, reaction buffer, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor, and selected primers (e.g., 2.5 µM random hexamers and/or 2.5 µM oligo(dT) [23].

- Incubation Conditions:

- Annealing: Incubate at 25°C for 5-10 minutes for primer binding.

- Extension: Incubate at the enzyme's optimal temperature (e.g., 50–55°C for engineered MMLV RT) for 10-60 minutes.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Heat to 85°C for 5 minutes [23].

- Output: The resulting cDNA can be diluted and used immediately in qPCR or stored at -20°C.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Setup

- Reaction Assembly: Typically performed in a 96- or 384-well plate. A standard 20 µL reaction contains:

- Essential Controls:

- No-Template Control (NTC): Contains all components except template cDNA. Checks for contaminating DNA.

- No-Reverse Transcription Control (NRT): Contains RNA that was not reverse transcribed. Checks for gDNA contamination.

- Positive Control: A sample with a known expression level of the target.

- Endogenous Control: One or more validated reference genes for normalization [22].

Thermal Cycling Conditions

The cycling profile depends on the detection chemistry and polymerase used.

Table 2: Standard qPCR Thermal Cycling Protocols

| Step | Temperature | Duration | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 2–10 minutes | Activates hot-start polymerase; fully denatures complex templates | Duration depends on polymerase [25]. |

| Amplification Cycles (40-50 cycles) | ||||

| › Denaturation | 95°C | 10–15 seconds | Melts dsDNA into single strands | |

| › Annealing/Extension | 60°C | 30–60 seconds | Primers and probes bind; polymerase extends | Single step for hydrolysis probes; separate steps (e.g., 72°C) for some dyes [25]. |

Data Analysis and MIQE Compliance

- Quantification Cycle (Cq): The cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses the threshold. A lower Cq indicates a higher starting template concentration [25] [22].

- PCR Efficiency: Must be calculated from a standard curve of serial dilutions. The percent efficiency should be 90–110% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1), which equates to a doubling of product per cycle. Assumptions of 100% efficiency are invalid [24] [9].

- Quantification Methods:

- Absolute Quantification: Determines the exact copy number of the target by comparing Cq values to a standard curve of known concentrations.

- Relative Quantification: Determines the change in target expression relative to a control sample and a reference gene. The comparative ΔΔCq method is commonly used, where RQ (Relative Quantity) = 2^(-ΔΔCq) [22].

- Normalization: Must be performed against one or more validated reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) that are stably expressed across all experimental conditions. Normalization is non-negotiable for accurate relative quantification [9].

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the complete RT-qPCR workflow, highlighting critical checkpoints mandated by MIQE guidelines for ensuring data validity.

Diagram: The RT-qPCR Workflow and Critical MIQE Checkpoints. This diagram outlines the sequential steps of the RT-qPCR protocol, integrating essential quality control points (red diamonds) and methodological choices (green rectangles) required for generating MIQE-compliant, reproducible data.

The power of RT-qPCR as a tool for gene expression analysis is undeniable, but this power is contingent upon methodological rigor. The MIQE guidelines provide the essential framework for this rigor. By meticulously adhering to the protocols outlined here—prioritizing RNA quality, validating assays, including appropriate controls, employing proper normalization, and reporting with full transparency—researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their RT-qPCR data are robust, reproducible, and reliable. In an era where molecular data directly impact research credibility, therapeutic development, and diagnostic decisions, integrating MIQE principles into laboratory practice is not just best practice; it is a professional imperative.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has become a cornerstone technology in the development and regulatory bioanalysis of cell and gene therapies (CGTs). These advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) represent a paradigm shift in treating diseases by introducing genetic material or modified cells into a patient's body. Gene therapy works by introducing a normal copy of a defective gene into target cells, enabling them to produce functional proteins to combat diseases ranging from cancer and cystic fibrosis to diabetes and hemophilia [27]. The core of these therapies often involves viral vectors, with adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors being the most common delivery system, though other systems like replication-competent viral vectors and microbial vectors are also employed [27].