Molecular Replacement Success: A Practical Guide to Assessing and Optimizing Search Model Quality

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, accounting for approximately 80% of deposited structures.

Molecular Replacement Success: A Practical Guide to Assessing and Optimizing Search Model Quality

Abstract

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, accounting for approximately 80% of deposited structures. However, its success critically depends on the quality of the search model. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on assessing model quality for MR. We cover foundational concepts, including the key metrics of sequence identity and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), and explore traditional and modern methodological approaches from homology modeling to machine learning-enhanced structure prediction. The guide also details advanced troubleshooting strategies for problematic cases and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques and quality assessment programs to ensure model reliability. By synthesizing established practices with recent advances, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to systematically evaluate and optimize models, thereby increasing the success rate of their MR experiments.

The Pillars of Success: Understanding How Model Quality Dictates Molecular Replacement Outcomes

Why Model Quality is the Critical Bottleneck in Molecular Replacement

Molecular replacement (MR) is a primary method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography by placing a known, structurally similar model into the unit cell of an unknown target structure [1]. The success of MR is critically dependent on the quality of the search model, which remains a significant bottleneck. Even with the ever-increasing number of structures in the Protein Data Bank, the generation of a suitable search model is a complex task, primarily due to the sensitivity of MR to the dissimilarity between the search model and the target protein [2]. Model quality encompasses the accuracy of the atomic coordinates, the degree of structural conservation, and the correct representation of oligomeric states and domain architectures. This article details the quantitative impact of model quality on MR success and provides structured protocols for model assessment and preparation.

The Critical Link Between Model Quality and MR Success

The relationship between model quality and the likelihood of a successful molecular replacement solution is direct and quantifiable. MR is fundamentally a six-dimensional problem searching for the correct orientation and placement of a model within a crystallographic unit cell [3]. The effectiveness of this search is highly sensitive to the divergence between the search model and the true target structure.

Quantitative Impact of Model Accuracy

Extensive empirical evidence has established clear thresholds for model quality that correlate with successful MR. The following table summarizes the key parameters and their impact:

Table 1: Model Quality Parameters and Their Impact on MR Success

| Parameter | Threshold for MR Success | Impact on Molecular Replacement |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity | >25-30% [1] | Higher identity produces a more accurate model, increasing the signal in rotation and translation functions. |

| C⍺ RMS Deviation | <2.0 Å [1] | Lower RMSD indicates closer structural alignment to the target, facilitating correct placement. |

| Model Completeness | Should match expected oligomeric/domain state [2] | Incomplete models lack sufficient scattering mass, weakening the signal in Patterson-based functions. |

When sequence identity falls below approximately 20%, standard model correction techniques based on sequence alignment become unreliable and may even decrease the probability of finding a solution by removing too many buried atoms, resulting in a sparse model that is treated poorly during surface modification steps [2]. Furthermore, if a model is expected to have a large RMS error, high-resolution data will not contribute significant signal. In such cases, the resolution used for the MR search should be limited to about 1.8 times the estimated RMS error of the model to capture the majority of the achievable log-likelihood gain (LLG) [4].

Consequences of Poor Model Quality

Suboptimal search models lead to specific, identifiable failures in the MR process:

- Low Signal-to-Noise in Searches: The correct solution in rotation and translation functions is characterized by its Z-score, a measure of standard deviations above the mean of a random set. For a translation function, a correct solution will generally have a Z-score (TFZ) over 5 and be well-separated from incorrect peaks [4]. Poor models produce weak signals, making correct solutions indistinguishable from noise.

- Packing Clashes: Correct MR solutions must pack reasonably within the crystal lattice. Phaser defaults allow up to 5% of C-alpha atoms to be involved in clashes. Solutions with more clashes are typically rejected, though these clashes may arise from minor differences in surface loops rather than a fundamentally incorrect solution [4].

- Domain Rearrangements: A common cause of MR failure even with apparently good models is that multi-domain proteins may have undergone conformational changes. In these cases, using a single rigid model for the entire structure is ineffective, and the structure must be split into individual domains for separate MR searches [1].

Model Quality Assessment and Preparation Protocols

Pre-MR Assessment Workflow

A systematic approach to model assessment significantly increases the probability of MR success. The following workflow should be implemented before initiating MR calculations:

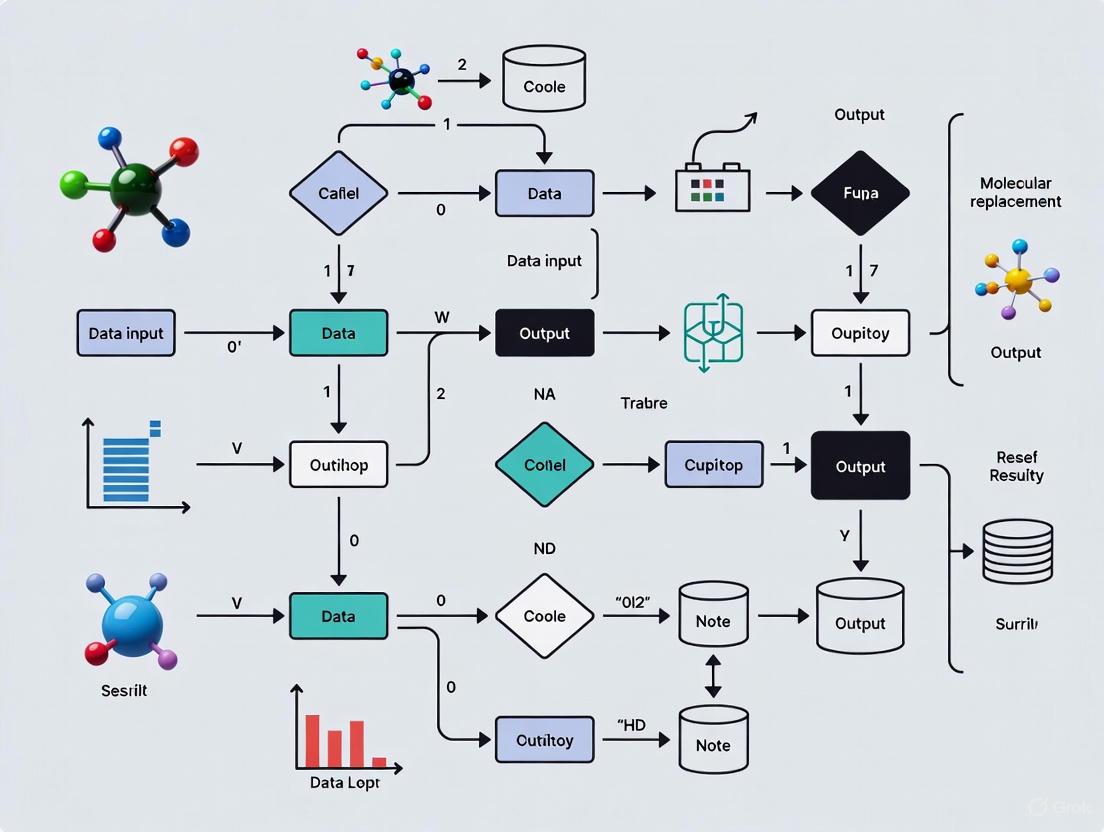

Model Quality Assessment Workflow

Detailed Model Preparation Methodology

Model preparation is a critical step that can substantially improve MR performance. The following protocols are adapted from established MR programs and integrated pipelines:

Sequence-Based Model Correction

The MOLREP program implements a conservative model correction approach based on amino acid sequence alignment:

- Input Requirements: A file containing the target protein sequence and the search model coordinates.

- Alignment Algorithm: A modified dynamic alignment algorithm that considers the three-dimensional structure of the search model, giving greater weight to buried residues than surface residues in the total alignment score [2].

- Modification Rules:

- Residues aligning with gaps in the target sequence are deleted.

- Atoms in the search model that have no counterpart in the target residue are deleted (e.g., for Val corresponding to Leu, CD1 and CD2 atoms are removed).

- Preserved atoms are renamed and renumbered according to the target sequence.

- Critical Threshold: This correction is automatically applied only when sequence identity exceeds 20%, as correction below this threshold often removes too many buried atoms, creating a sparse model that performs poorly [2].

Surface Accessibility Modification

Surface residues are typically less conserved and have higher mobility. MOLREP's default preparation scheme accounts for this by:

- Calculating the accessible surface area for each atom using a fast algorithm.

- Computing new atomic displacement parameters (ADPs) using the empirical formula:

ADP = U + V*S, whereU = 15 Ų,V = 20, andSis the accessible surface area of the atom [2]. - This modification effectively smears the electron density of solvent-exposed atoms, better approximating their behavior in the crystallographic environment.

Advanced Model Optimization for Challenging Cases

For difficult MR problems where standard model preparation is insufficient, several advanced techniques can be employed:

- Model Trimming and Sculpting: Removing variable polypeptide segments identified through three-dimensional superposition of homologous structures can be critical for MR success. Programs like phenix.sculptor can systematically improve models by trimming poorly conserved regions [2] [1].

- Ensemble Creation: Combining multiple structurally related models into an ensemble can enhance the signal in MR searches. phenix.ensembler automates the process of superimposing models using a conserved structural core [1].

- Normal-Mode Analysis: Scanning possible conformations of the unknown protein using normal-mode analysis can generate alternative models that better match the target conformation [2].

Model Quality Assessment in the AlphaFold Era

Recent advances in protein structure prediction, particularly AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, have transformed the landscape of model availability for MR. The CASP16 evaluation of model accuracy experiment highlighted that methods incorporating AlphaFold3-derived features—particularly per-atom pLDDT (predicted local distance difference test)—performed best in estimating local accuracy [5]. This per-residue confidence metric provides invaluable guidance for model preparation before MR:

- High pLDDT Regions: Structurally conserved cores with high confidence scores can be used as initial search models or weighted more heavily in MR searches.

- Low pLDDT Regions: Flexible loops and low-confidence regions may be trimmed prior to MR to reduce noise, similar to the handling of variable regions in homology-based models.

- Multimeric Assemblies: For complex targets, predicted interfaces and assembly quality scores help in constructing appropriate oligomeric search models, which is particularly crucial for CASP16's emphasis on multimeric targets [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software for MR

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Model Preparation and Molecular Replacement

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| MOLREP [2] | Integrated MR and model preparation | Performs automated sequence-based model correction and surface accessibility modification. |

| Phaser [1] [4] | Maximum-likelihood molecular replacement | Uses LLG and Z-scores to objectively assess model quality during MR search. |

| phenix.sculptor [1] | Model preparation for MR | Improves models by trimming poorly conserved regions based on sequence and structural analysis. |

| phenix.ensembler [1] | Ensemble model creation | Prepares ensembles of related structures for MR to enhance signal through structural averaging. |

| BALBES [2] | Automated molecular replacement pipeline | Integrates model selection, modification, and MR in a unified framework trained on known structures. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common MR Failures

Even with careful model preparation, MR can fail. The following table outlines common failure modes and evidence-based solutions:

Table 3: Troubleshooting Molecular Replacement Failures

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| No solutions found | Conformational change in multi-domain protein | Split structure and perform MR on individual domains [1] | Clear solution for individual domains with subsequent rebuilding |

| High TFZ but rejected for packing | Clashes from divergent surface loops | Edit model to remove problematic loops or increase allowed clashes [4] | Acceptance of correct solution with minor clashes |

| Weak rotation function signal | Low sequence identity or structural divergence | Trim variable surface regions or use ensemble of models [2] | Improved signal-to-noise in rotation function |

| Correct orientation not identified | Special position in Eulerian angles (β = 0° or 180°) | Examine peaks with lower significance (Z-scores down to 4) [4] | Identification of correct orientation through translation function |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized MR Procedure

The following step-by-step protocol ensures systematic handling of model quality issues during MR:

Step 1: Model Identification and Quality Assessment

- Identify potential search models using sequence and structure databases.

- Calculate sequence identity and align structures to assess structural conservation.

- Verify oligomeric state compatibility with self-rotation function results.

Step 2: Initial Model Preparation

- Apply sequence-based correction if sequence identity >20%.

- Perform surface accessibility modification to account for solvent-exposed atoms.

- Trim obviously disordered regions or low-confidence loops.

Step 3: MR Search with Phaser

- Input experimental data, prepared model(s), and target sequence.

- Use automated molecular replacement mode initially.

- Monitor TFZ scores (>8 definitive, 7-8 probable, 6-7 possible, <5 unlikely) [4].

Step 4: Solution Validation and Iteration

- If no clear solution, examine lower significance peaks (down to 75% of top peak).

- For promising solutions rejected for packing, reconsider clash tolerance or further model editing.

- If partial solution found, add remaining components with improved signal.

Step 5: Model Improvement

- Use phenix.morphmodel or phenix.mrrosetta to improve initial MR solutions [1].

- Perform iterative rebuilding and refinement to converge on the final structure.

The logical relationships and decision points in this protocol are visualized below:

Molecular Replacement Experimental Protocol

Model quality remains the critical bottleneck in molecular replacement, directly determining success through quantifiable parameters of sequence identity, structural conservation, and proper oligomeric representation. Systematic model assessment and preparation—including sequence-based correction, surface accessibility modification, and strategic trimming of variable regions—are essential prerequisites for successful MR. The integration of AlphaFold-derived models with per-residue confidence metrics provides powerful new opportunities for addressing this persistent challenge. By implementing the structured protocols and quality thresholds outlined in this article, researchers can systematically overcome the model quality bottleneck and expand the boundaries of solvable structures in macromolecular crystallography.

In molecular replacement (MR), the most common method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, the success of the experiment critically depends on the quality of the search model used. MR involves placing a known molecular model within the unit cell of an unknown crystal structure to derive initial phase estimates, a method that currently solves up to 70% of deposited macromolecular structures [6] [7]. Assessing the potential utility of a model prior to embarking on computationally intensive MR searches requires a firm understanding of three key metrics: sequence identity, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), and Global Distance Test Total Score (GDT_TS). This application note defines these metrics, details protocols for their calculation, and frames their interpretation within the context of model quality assessment for molecular replacement research, providing a critical toolkit for structural biologists and drug development professionals.

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Sequence Identity

Sequence identity is a measure of the evolutionary relatedness between the amino acid sequences of a target protein and a potential structural template. It is calculated as the percentage of identical amino acids at aligned positions in an optimal sequence alignment.

For MR, sequence identity serves as a primary, readily available proxy for estimating expected structural similarity. A general empirical rule suggests that MR is most straightforward when sequence identity is at least 30-35% [8] [9]. Below this "twilight zone" of ~25-30% identity, sequence alignment becomes error-prone, and structural conservation can no longer be assumed, making MR increasingly challenging [9].

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD)

The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) quantifies the average distance between the atoms of two superimposed protein structures after optimal rigid-body superposition. It provides a measure of the global, atomic-level accuracy of a model.

The RMSD is calculated using the formula:

RMSD = √[ (1/N) * Σ(δ_i)² ]

where N is the number of equivalent atoms, and δ_i is the distance between the i-th pair of atoms after superposition [10]. The calculation is typically performed on the backbone heavy atoms (C, N, O, Cα) or sometimes only the Cα atoms [10]. A lower RMSD indicates a closer match to the target structure. However, RMSD is highly sensitive to local large errors and can be dominated by the most variable regions of the structure.

Global Distance Test Total Score (GDT_TS)

The Global Distance Test Total Score (GDT_TS) is a more robust measure of global structural similarity, designed to be less sensitive to outlier regions than RMSD. It evaluates the model by determining the largest set of equivalent Cα atoms that lie within a defined distance cutoff of the corresponding atoms in the target structure.

The GDTTS is calculated as the average of the percentages of Cα atoms that can be superimposed under four different distance cutoffs:

GDT_TS = (GDT_1Å + GDT_2Å + GDT_4Å + GDT_8Å) / 4

where GDT_XÅ is the percentage of residues whose Cα atoms are within X Ångströms of their correct position after optimal superposition [8]. A higher GDTTS indicates a better model. Research has shown that GDT_TS is a better indicator of a model's utility for MR than RMSD [8].

Quantitative Data and Interpretation for Molecular Replacement

The following tables consolidate critical thresholds and relationships between metrics to guide model selection for MR experiments.

Table 1: Metric Thresholds and Their Implications for Molecular Replacement Success

| Metric | General "Easy MR" Threshold | Interpretation in MR Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity | ≥ 30-35% [8] [9] | Predicts high likelihood of conserved fold. Below this, alignment errors and structural divergence risk MR failure. |

| RMSD | Lower is better (Model-dependent) | Measures average atomic deviation. Sensitive to small, variable regions; can be misleading if local errors are large. |

| GDT_TS | > 80-84 [8] | Strongly correlates with MR success. Models below ~80 GDT_TS are rarely successful, while scores >84 often guarantee success [8]. |

Table 2: Inter-metric Relationships and Comparative Utility

| Aspect | Sequence Identity | RMSD | GDT_TS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Utility | Preliminary model screening | Quantifying atomic-level precision | Assessing overall fold correctness |

| Sensitivity to Outliers | N/A (Sequence-based) | High | Low |

| MR Predictive Power | Indirect, correlative | Good, but can be misleading | Superior direct predictor [8] |

| Calculation Prerequisite | Target sequence | Target 3D structure | Target 3D structure |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Sequence Identity

This protocol details the steps to determine the sequence identity between a target protein and a potential template.

- Input Data: Obtain the amino acid sequence of your target protein and the template protein (e.g., from UniProt).

- Sequence Alignment: Perform a pairwise sequence alignment using a tool like BLASTP or Clustal Omega. Use default parameters initially.

- Identify Aligned Residues: From the alignment output, identify the positions where the amino acids are identical.

- Calculation:

- Count the number of aligned positions with identical residues.

- Count the total number of aligned positions (including gaps).

- Calculate percentage identity:

(Number of identical residues / Total number of aligned positions) * 100.

Protocol 2: Calculating RMSD and GDT_TS

This protocol requires the known three-dimensional structure of the target and the model to be assessed.

- Input Data: Obtain the atomic coordinate files (PDB format) for the target structure and the model structure.

- Structural Superposition:

- Use a structural alignment tool such as LGA (Local-Global Alignment) [8], SSM, or PyMOL's

aligncommand. - Superpose the model onto the target structure using Cα atoms. The algorithm will find the optimal rotation and translation to minimize the distances between equivalent atoms.

- Use a structural alignment tool such as LGA (Local-Global Alignment) [8], SSM, or PyMOL's

- RMSD Calculation:

- The superposition tool will typically output the RMSD value directly, calculated over the defined set of equivalent Cα atoms.

- GDTTS Calculation:

- Use a dedicated program like LGA or the service provided by the CASP Prediction Center.

- Input the two PDB files. The algorithm will report the GDTTS as the average of the fractions of Cα atoms within 1, 2, 4, and 8 Å distance cutoffs after optimal superposition [8].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing model quality using the three key metrics, from initial screening to final evaluation for molecular replacement.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Metric Calculation and MR

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in MR/QA |

|---|---|---|

| BLASTP | Software Suite / Web Server | Performs sequence alignment to identify homologous templates and calculate sequence identity. |

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Software Program | Performs structural superpositions and calculates key metrics including RMSD and GDT_TS [8]. |

| MolProbity | Web Server / Software | Provides all-atom contact analysis and validation, including Ramachandran plots and clashscores, to assess local model quality [11]. |

| MetaMQAPclust | Software | A Model Quality Assessment Program (MQAP) that predicts local accuracy of theoretical models, improving MR success rates [8]. |

| Phaser | Software | A leading MR program that uses maximum-likelihood methods for rotation and translation searches [7] [4]. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository for experimental structures used as templates and for validation of final models. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Resource for high-accuracy computational models that can be used as search models in MR [5]. |

The integrated use of sequence identity, RMSD, and GDTTS provides a powerful framework for evaluating search models in molecular replacement. While sequence identity offers an initial filter, the three-dimensional metrics RMSD and, most importantly, GDTTS provide a more direct and reliable prediction of MR success. By adhering to the protocols and thresholds outlined in this document, researchers can make informed decisions in model selection and preparation, thereby increasing the efficiency and success rate of their molecular replacement experiments, a critical step in accelerating structural biology and structure-based drug design.

The 30-35% Sequence Identity Threshold and Its Implications

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, provided a structurally homologous model is available. The technique involves positioning a search model within the asymmetric unit of the target crystal to derive initial phase information [12]. The success of MR is critically dependent on the quality of the search model, which has historically been quantified by its sequence identity to the target protein. The 30-35% sequence identity threshold represents a critical frontier in MR, separating straightforward problems from challenging ones. Below this range, the success rate of molecular replacement drops considerably, demanding sophisticated modeling and search strategies to achieve a solution [13]. This application note explores the theoretical and practical implications of this threshold and provides detailed protocols for successful structure determination in low-sequence-identity scenarios, framed within a broader research context focused on assessing model quality for molecular replacement.

The Theoretical Basis of the Sequence Identity Threshold

The Relationship Between Sequence and Structure

The empirical link between sequence identity and structural similarity was first established decades ago, forming the foundation for modern MR practices. Chothia and Lesk demonstrated that the Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between two protein structures correlates with their percentage sequence identity [13]. In successful MR cases, the template and target typically share at least 35% sequence identity, corresponding to a Cα RMSD of approximately 1.5 Å [13]. This relationship underpins the 30-35% threshold, as structural deviations beyond this range generally become too substantial for standard MR protocols to handle effectively.

The accuracy of the search model remains the paramount factor for MR success. When sequence identity falls below 35%, the overall protein fold is often conserved, but accumulating differences in loop regions, side-chain orientations, and subtle domain shifts reduce the model's ability to generate usable phase information [12] [14].

Quantitative Impact on Molecular Replacement Success

Table 1: Relationship Between Sequence Identity and MR Success Indicators

| Sequence Identity | Cα RMSD (Å) | Expected MR Outcome | Required Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| >35% | <1.5 Å | Straightforward | Standard MR protocols usually sufficient |

| 20-35% | 1.5-2.5 Å | Challenging | Model optimization, advanced search algorithms |

| <20% | >2.5 Å | Very Difficult | Ensemble modeling, deep learning models, extensive optimization |

Statistical evidence from large-scale MR trials confirms this relationship. Tramontano and coworkers demonstrated that theoretical models with a Global Distance Test (GDTTS) score below 80 were rarely successful in MR, while a GDTTS above 84 generally guaranteed success [14]. Since GDT_TS correlates with sequence identity, this provides a complementary metric for assessing MR potential.

Practical Implications for Molecular Replacement

Challenges Below the Threshold

When sequence identity falls below the 30-35% threshold, several specific challenges emerge that complicate the MR process. The accuracy of the model becomes increasingly uncertain, particularly in loop regions and solvent-exposed areas where evolutionary pressure is reduced. Domain movements present another significant challenge, as relative orientations of structural domains may differ between template and target despite conservation of the individual domains themselves [12].

The limitations of traditional template-based modeling (TBM) become pronounced in this regime. TBM relies on identifying and using known protein structures as templates through sequence or structural homology, typically requiring at least 30% sequence identity between target and template for reliable results [15]. Below this threshold, sequence-based alignment methods struggle to generate accurate models, necessitating more sophisticated approaches.

Assessment of Model Quality

Accurately assessing model quality is essential for successful MR when working with low-identity templates. Model Quality Assessment Programs (MQAPs) have been developed to predict both global and local accuracy of theoretical models without knowledge of the true structure [14]. These programs fall into two main categories:

- "True MQAPs" - Methods capable of assessing quality for single models without using alternative decoys

- "Clustering MQAPs" - Methods that rely on structural comparisons between multiple alternative models

Research has demonstrated that incorporating predicted local accuracy from MQAPs significantly improves MR success rates. For a dataset of 615 search models, utilizing real local accuracy increased the MR success ratio by 101% compared to polyalanine templates. When predicted local accuracy from clustering MQAPs was used, the workflow found 45% more correct solutions than polyalanine templates [14].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Molecular Replacement with Low-Identity Models

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application in Low-Identity MR |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaspR Server | Homology Modeling | Automated MR using multiple alignment | Generates chimeric models from best-aligned regions |

| MetaMQAPclust | Quality Assessment | Predicts local model accuracy | Identifies reliable regions for use in MR |

| AMPLE | Ab Initio Modeling | Uses predicted secondary structure | Generates models when templates are unavailable |

| Phaser | MR Software | Likelihood-based MR search | Optimized for difficult cases with low LLG |

| AlphaFold 3 | Deep Learning | Predicts protein structures | Generates accurate models without templates |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Replacement with Low-Identity Templates

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for molecular replacement when working with templates sharing 20-35% sequence identity with the target protein.

Materials and Reagents:

- Processed crystallographic data (MTZ format)

- Target protein sequence

- Homology models or template structures

- Computing infrastructure with MR software (e.g., CCP4, Phenix)

Procedure:

Template Identification and Model Generation

Model Quality Assessment and Optimization

- Assess global and local model quality using MetaMQAPclust or similar MQAPs.

- Convert predicted Cα deviations to B-factors using the relationship:

B = 8π²〈u²〉, where〈u²〉is the mean-square displacement [14]. - Consider generating a polyalanine version of the model for initial searches.

Molecular Replacement Search Strategy

- Begin with automated MR in Phaser, providing all likely space groups in the same point group.

- If automated MR fails, run Phaser components separately, starting with the largest or most reliable domain.

- For translation function Z-scores (TFZ) between 5-7, proceed with caution and validate results meticulously [4].

Solution Validation and Model Building

- Examine the summary logfile and solution file for annotation of RFZ, TFZ, packing clashes, and LLG scores.

- Calculate maximum-likelihood-weighted difference electron-density maps to identify areas for model improvement.

- Iteratively rebuild the model, focusing on regions with poor fit to the electron density.

Protocol 2: Model Preparation Using the CaspR Server

For cases with particularly low sequence identity (<25%), the CaspR server provides a specialized approach to model generation.

Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Provide crystallographic data (symmetry, reflections, molecules per asymmetric unit)

- Submit a FASTA file with the target sequence and a set of reference sequences

- Include 1-6 PDB files as reference structures

Model Generation Process

- The server uses Expresso software to create a robust multiple alignment with CORE index information

- MODELLER generates models with random initial perturbations, using CORE index to define reliable regions

- Unreliable parts of the alignment are truncated, potentially creating chimeric models from different templates

MR Search and Solution Ranking

- Molecular replacement is performed for each model using AMoRe

- The best solutions are refined using CNS and ranked by Rfree/Rwork values

- Successful solutions typically correspond to the core structures most likely to provide MR solutions [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Molecular Replacement

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TwistAmp Liquid Basic Kit | Isothermal DNA amplification | Enables RPA amplification for STR genotyping; operates at 37-42°C |

| AmpFlSTR Identifiler Plus PCR Kit | Conventional PCR amplification | Gold standard for STR analysis; requires thermal cycling |

| DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit | DNA extraction from samples | High-quality DNA purification for downstream applications |

| PDB Database | Repository of protein structures | Primary source of search models for MR |

| HHpred/PHMMER | Remote homology detection | Identifies structural homologs with low sequence identity |

Workflow Visualization

Low-Identity MR Workflow

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Recent advances in deep learning-based structure prediction are fundamentally changing the landscape of molecular replacement, particularly for low-sequence-identity scenarios. AlphaFold 2 and its successors have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in protein structure prediction, often generating models suitable for MR even without clear structural homologs [16]. These methods effectively bypass the traditional sequence identity threshold by leveraging co-evolutionary information and physical principles learned from known structures.

The integration of these AI-based models with traditional MR workflows shows particular promise. Unlike traditional template-based modeling, which requires at least 30% sequence identity for reliable performance, deep learning methods can generate accurate models for proteins with no close structural homologs [15] [16]. This capability is revolutionizing the MR process, making previously intractable problems solvable.

Long-read sequencing technologies also contribute to this evolving landscape by improving genome assembly and enabling more accurate gene models, particularly in repetitive regions [17]. While not directly related to MR, these advances support the overall goal of determining accurate macromolecular structures by providing better initial sequences.

The 30-35% sequence identity threshold remains a significant consideration in molecular replacement, demarcating the boundary between routine and challenging structure determinations. Below this threshold, success requires sophisticated model generation, rigorous quality assessment, and specialized MR strategies. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a framework for navigating this difficult territory. Furthermore, emerging technologies, particularly deep learning-based structure prediction, are reshaping what is possible in MR, potentially rendering the traditional sequence identity threshold less relevant over time. Nevertheless, understanding the implications of this threshold and mastering the techniques to overcome its limitations remains essential for structural biologists working at the frontiers of macromolecular crystallography.

The Impact of Model Completeness and Domain Architecture

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, accounting for over 70% of structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank [7]. The success of MR hinges critically on the quality of the search model, with model completeness and domain architecture representing two pivotal factors. Model completeness refers to the fraction of the target structure's electron density that can be explained by the search model, while domain architecture concerns the spatial arrangement of structurally distinct regions within a protein. Inappropriate treatment of either factor can derail the MR process, as an incomplete model may lack sufficient signal for detection, and incorrect assumptions about domain arrangements can position structural elements in physically implausible orientations. This application note examines the quantitative impact of these factors and provides structured protocols to optimize MR success rates for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Framework

The Molecular Replacement Principle

Molecular replacement solves the crystallographic phase problem by positioning a known structural model within the unit cell of an unknown target structure. The method is fundamentally a six-dimensional search problem requiring determination of three rotational and three translational parameters [3]. In practice, this search is typically divided into sequential rotation and translation functions to reduce computational complexity. The rotation function identifies the correct orientation of the search model by comparing its Patterson function (which maps interatomic vectors) with the Patterson function calculated from experimental diffraction data. Once oriented, the translation function locates the model's position within the unit cell by testing different translational vectors while maintaining the established orientation [3] [18].

The Patterson function, calculated directly from measured diffraction intensities without phase information, is central to MR. It represents a map of all interatomic vectors within the crystal, containing both intramolecular vectors (which rotate with the molecule) and intermolecular vectors (which depend on molecular position) [3]. This property enables the separation of rotational and translational searches. The critical relationship between model quality and MR success emerges because inaccuracies in the search model introduce errors in the calculated Patterson function, reducing its correlation with the experimental Patterson and diminishing the signal-to-noise ratio in both rotation and translation searches.

Critical Quality Metrics for Search Models

The utility of a search model in MR is quantified through several key metrics. The log-likelihood gain (LLG) has emerged as the primary scoring function in maximum-likelihood MR implementations like Phaser, with a value greater than 40-60 generally indicating a correct solution [4]. The translation function Z-score (TFZ) provides a measure of signal-to-noise, where values above 8 almost certainly indicate a correct solution, while values between 6-7 suggest only a possible solution [4].

Global model accuracy is frequently assessed through GDTTS (Global Distance Test) and Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Research indicates that models with GDTTS below 80 rarely succeed in MR, while those with GDT_TS above 84 almost always produce solutions [14]. Sequence identity between the search model and target structure provides a rough guide for expected model accuracy, with identities above 25-30% and Cα RMSD below 2.0 Å generally required for successful MR [1].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Molecular Replacement Success

| Metric | Threshold for Success | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| LLG | >40-60 | Indicates correct solution |

| TFZ | >8 (definite), 6-7 (possible) | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| GDT_TS | >84 (guaranteed), <80 (rare) | Global model accuracy |

| Sequence Identity | >25-30% | Expected homology |

| Cα RMSD | <2.0 Å | Structural deviation |

Quantitative Impact of Model Completeness

Minimum Completeness Requirements

Model completeness directly determines what fraction of the target structure's scattering power can be explained during MR searches. While even partial models can sometimes succeed, the completeness threshold depends on the biological context. For single-domain proteins in the asymmetric unit, the search model should ideally represent a substantial portion of the target. For multi-component complexes, the situation is more complex—the initial component placed may represent only a fraction of the total scattering mass, but successive placements should progressively increase the explained density [4].

Research demonstrates that the relationship between completeness and MR success is not linear. The initial components placed in a complex structure may yield relatively low LLG scores, but as correct components are added, the LLG should increase significantly with each addition [4]. This progressive signal enhancement underscores the importance of completeness in multi-component searches.

Local Error Estimation and Model Optimization

Beyond global completeness, local model accuracy significantly impacts MR success. Modern model quality assessment programs (MQAPs) like ProQ3D predict local error and enable optimization of search models by converting predicted Cα deviations to B-factors (temperature factors), effectively smearing atoms over their range of possible positions [19].

The impact of this approach is substantial. In a study of 431 homology models for difficult MR targets, models with ProQ3D error estimates achieved an LLG >50 (indicating ~90% success probability) in 48.5% of cases, compared to only 17.2% for models without error estimates [19]. This represents a nearly threefold improvement in success rate, highlighting the critical importance of local error estimation.

Table 2: Impact of Local Error Estimation on MR Success

| Error Treatment | Models with LLG>50 | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|

| No error estimates | 74/431 | 17.2% |

| ProQ2 error estimates | 175/431 | 40.6% |

| ProQ3D error estimates | 209/431 | 48.5% |

B-factor optimization follows the relationship between positional uncertainty and B-factor: B = 8π²⟨u²⟩, where ⟨u²⟩ represents the mean-square displacement of an atom from its average position [14]. By setting B-factors according to predicted local errors, the model more accurately represents the true probability distribution of atomic positions, improving the agreement between calculated and observed structure factors.

Domain Architecture Challenges and Solutions

Domain Rearrangements and Conformational Flexibility

Proteins frequently undergo domain rearrangements between different crystal forms or functional states, creating substantial challenges for MR. When domains have shifted relative to their positions in the search model, treating the protein as a single rigid body will fail because no single orientation places all domains correctly [1]. This problem is particularly common in proteins with flexible hinges, such as antibody Fab fragments where the variable and constant domains can adopt different "elbow angles" [7].

The signal suppression caused by domain movements can be severe enough to preclude solution even with otherwise excellent models. Research indicates that domain movements represent one of the most common causes of MR failure when good search models are available [1]. This underscores the importance of analyzing potential conformational differences before initiating MR searches.

Strategic Deconstruction into Structural Units

The most effective strategy for handling domain rearrangements is structural deconstruction—splitting multi-domain proteins into individual domains or rigid bodies and searching for them separately [1]. This approach transforms an intractable single-placement problem into a series of simpler placements, each with higher probability of success.

For proteins of unknown domain architecture, tools like CONCOORD or Normal Mode Analysis can suggest plausible rigid body divisions based on predicted flexibility. Alternatively, examining multiple homologous structures can reveal conserved domain boundaries and highlight potentially flexible regions.

Table 3: Domain Processing Strategies for Molecular Replacement

| Scenario | Recommended Strategy | Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Known domain boundaries | Split into individual domains | CHAINSAW, Sculptor |

| Unknown domain architecture | Analyze homologous structures or predicted flexibility | DynDom, CONCOORD |

| Flexible linkers | Remove or truncate non-conserved loops | CHAINSAW |

| Multi-domain with conserved orientation | Test both single-body and divided approaches | Phaser, Molrep |

After successful placement of individual domains, the complete structure can be reconstructed through rigid-body refinement, which optimizes the positions and orientations of the domains relative to each other while maintaining their internal coordinates. This process typically improves the electron density map and facilitates subsequent model building and refinement.

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Pre-MR Analysis Workflow

Before initiating molecular replacement, thorough analysis of both the search model and experimental data is essential. The following protocol ensures optimal preparation:

Model Quality Assessment

Domain Architecture Analysis

- Identify domain boundaries using domain databases or structural analysis tools

- Compare with homologous structures to identify potential conformational differences

- Split multi-domain proteins into individual structural units if rearrangements are suspected [1]

Data Preparation and Validation

- Process diffraction data to the highest possible resolution

- Analyze anisotropy with Xtriage or similar tools

- Verify space group assignment through systematic absence analysis

Molecular Replacement Execution Protocol

The actual MR search should follow a structured approach:

Initial Low-Resolution Search

- Begin with data truncated to 3.5-4.0 Å resolution to enhance signal

- Use the highest-quality search model or domain first

- In Phaser, allow the program to automatically select resolution limits based on expected LLG [4]

Multi-Component Placement

- For multiple copies or domains, add components sequentially

- Monitor LLG increase with each addition—significant improvement indicates correctness

- For ambiguous solutions, test multiple peaks from rotation and translation functions

Solution Validation

- Verify TFZ > 6-8 for the complete solution [4]

- Check packing with default clash criteria (up to 5% Cα clashes allowed)

- Examine electron density maps for coherent density and model fit

Post-MR Model Improvement

After obtaining an MR solution:

Initial Refinement

- Perform rigid-body refinement of domains or subunits

- Run several cycles of positional and B-factor refinement with moderate restraints

Map Improvement

- Calculate maximum-likelihood weighted maps

- Use automated model building with Buccaneer or ARP/wARP

Model Completion

- Manually rebuild problematic regions in Coot

- Add water molecules and ligands in well-defined density

- Validate geometry with MolProbity

Visualization and Decision Support

Molecular Replacement Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete MR process with emphasis on handling model completeness and domain architecture:

Domain Splitting Strategy

This diagram details the decision process for handling multi-domain proteins:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phaser | Software | Maximum-likelihood MR | Handles difficult cases with ensembles and multi-component searches [1] [4] |

| Molrep | Software | Automated MR | User-friendly alternative with automated features [18] |

| ProQ3D | Software | Local quality prediction | Predicts local model errors for B-factor optimization [19] |

| Sculptor | Software | Model preparation | Trims non-conserved regions and optimizes models for MR [1] |

| Phenix | Software suite | Comprehensive structure solution | Provides end-to-end solution from MR to refinement [1] |

| Modeller | Software | Comparative modeling | Generates homology models when experimental structures unavailable [14] |

| Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (CCP4) | Software suite | Crystallographic computation | Standard environment for macromolecular structure solution [18] |

Model completeness and domain architecture fundamentally influence molecular replacement outcomes. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that local error estimation through tools like ProQ3D can nearly triple MR success rates for challenging targets, while appropriate handling of domain rearrangements through strategic splitting often transforms impossible MR problems into tractable ones. By adopting the integrated protocols and decision frameworks presented herein, structural biologists can systematically address these critical factors, enhancing the efficiency and success of structure determination efforts. This approach is particularly valuable in drug discovery contexts where rapid structure determination of target proteins facilitates structure-based drug design.

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography. The technique relies on placing a known, structurally similar model—the "search model"—into the crystallographic unit cell of the unknown target structure to derive initial phase information [20]. For decades, the primary source of search models has been experimentally determined structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). However, the persistent challenge has been the lack of suitable homologs for many target proteins, particularly those with novel folds or low sequence similarity to known structures.

Recent breakthroughs in computational protein structure prediction, exemplified by tools like AlphaFold2, have fundamentally expanded the universe of available search models [21] [22]. These advances have enabled the generation of accurate theoretical models for nearly the entire proteome, dramatically increasing the success rate of MR for previously intractable targets. This Application Note details the protocols and metrics for leveraging these computational models effectively within the context of molecular replacement, providing a framework for assessing model quality and utility in phasing experiments.

Key Advances in Computational Model Quality

The accuracy of computational models has improved to the point where they now rival some experimental structures. The CASP14 assessment demonstrated that models from leading groups, particularly AlphaFold2, could successfully phase targets that had resisted solution using traditional methods [21].

Quantitative Metrics for Model Utility in MR

The relative-expected Log-Likelihood Gain (reLLG) has been established as a key metric for predicting MR success. Unlike traditional metrics that require diffraction data, reLLG is a crystal-form-independent measure calculated directly from model and target coordinates, enabling a priori assessment of model quality [22].

Table 1: Model Quality Metrics Correlated with MR Success

| Metric | Threshold for MR Success | Calculation Method | Utility in MR |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | >80 [14] | Global Distance Test measuring Cα atomic distances | Strong indicator of overall model quality |

| reLLG | >60 [22] | Relative expected Log-Likelihood Gain from coordinates | Predicts MR success without diffraction data |

| RMSD | <2.0 Å [14] | Root Mean Square Deviation of Cα atoms | Measures overall model accuracy |

| pLDDT | >70 [23] | Predicted Local Distance Difference Test | Per-residue confidence score from AlphaFold |

Impact of Advanced Prediction Methods

AlphaFold2 models have demonstrated remarkable success in CASP14, solving four previously intractable targets. In the case of target T1058 (FoxB), an AlphaFold2 model achieved an overall Cα RMSD of 0.97 Å to the final experimental structure, enabling molecular replacement where traditional homology models had failed [21]. The model correctly positioned even functionally critical residues, such as the histidine residues coordinating heme groups, despite being generated from sequence information alone.

Application Notes: Successful Implementations

Case Study 1: Solving the FoxB Membrane Reductase Structure

The inner membrane reductase FoxB (CASP target T1058) represents a classic example where computational models enabled structure determination after experimental methods stalled.

Experimental Challenge: Initial molecular replacement attempts using distant homologs and conventional homology models failed. Experimental phasing using Se-Met and Fe-edge anomalous data provided only partial phase information, allowing building of just 60-70% of the backbone [21].

Computational Solution: The AlphaFold2 model (T1058TS427_3) generated a clear MR solution with translation function Z-score (TFZ) of 18.9 and log-likelihood gain (LLG) of 324. Subsequent MR-SAD phasing and refinement produced a high-quality electron density map for the entire protein [21].

Key Insight: The success was attributed to the model "getting the details right," including correct registration of transmembrane helices and accurate positioning of periplasmic domains with multiple loops.

Case Study 2: Multi-Model Approach for Antiviral Mini-Protein LCB2

A recent study demonstrated the utility of using multiple computer-predicted structures as MR models for the small antiviral protein LCB2, a three-helix bundle of 58 residues [24].

Experimental Design: Models from six different prediction programs (AlphaFold3, AlphaFold2, MultiFOLD, Rosetta, RoseTTAFold, and trRosetta) were used independently as MR search models.

Results: All six models produced successful MR solutions, converging to structures within 0.25 Å all-atom RMSD of each other. The structural variations observed between solutions, particularly in surface side-chain conformations, were interpreted as representing legitimate conformational dynamics rather than mere model bias [24].

Advanced Application: Combining the six structures into a multiconformer ensemble significantly improved R-work and R-free compared to individual solutions, providing insights into protein dynamics directly from crystallographic data.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Molecular Replacement with Computational Models

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for molecular replacement using computationally predicted models.

Figure 1: Standard workflow for molecular replacement using computational models. The process begins with data preparation and model selection, proceeds through rotation and translation functions, and culminates in phase generation, model building, and refinement.

Step 1: Data Preparation

- Process diffraction data with Aimless to scale and merge reflections [23]

- Estimate asymmetric unit content using Matthews coefficient calculations

- Confirm space group assignment

Step 2: Model Selection and Retrieval

- For novel targets: Generate AlphaFold2 model using ColabFold or local installation

- For targets with known homologs: Retrieve pre-computed models from AlphaFold Database

- Assess global model quality using pLDDT scores and predicted aligned error

Step 3: Model Preparation

- Prune low-confidence regions (typically pLDDT < 70) using Slice or similar tools [23]

- Convert pLDDT confidence scores to B-factor estimates using the relationship: B-factor ≈ 100 × (1 - pLDDT/100)

- Remove obviously disordered loops or termini that may hinder MR search

Step 4: Molecular Replacement Search

- Perform rotation function search using Phaser or Molrep

- Execute translation function with the correctly oriented model

- For multi-chain structures, employ locked rotation function or ensemble MR approaches

Step 5: Phase Generation and Model Building

- Generate experimental phases from the placed model

- Calculate initial electron density maps

- Perform automated model rebuilding with ModelCraft or similar tools [23]

- Manual inspection and adjustment in Coot, focusing on low-confidence regions

Step 6: Refinement and Validation

- Iterative refinement with Refmac or Phenix.refine

- Validate geometry using MolProbity or PDB Validation Report [23]

- Cross-validate with free R-factor throughout refinement

Protocol 2: Automated MR with AlphaFold Models in CCP4 Cloud

The CCP4 Cloud platform provides predefined workflows that streamline molecular replacement with computational models.

Figure 2: Automated molecular replacement workflow for AlphaFold models in CCP4 Cloud. The workflow integrates model generation, molecular replacement, and automated rebuilding in a single pipeline.

Step 1: Input Preparation

- Provide merged or unmerged reflection data in MTZ or similar format

- Input protein sequence in FASTA format

- Optionally provide ligand description for complex structures

Step 2: Automated Execution

- Launch the af-MR workflow in CCP4 Cloud [23]

- The system automatically:

- Processes and scales reflection data with Aimless

- Generates AlphaFold2 model using ColabFold integration

- Prunes low-confidence regions and converts pLDDT to B-factors

- Performs molecular replacement with Phaser

- Conducts automated model rebuilding with ModelCraft

Step 3: Post-MR Processing

- For ligand-containing structures: Automated ligand fitting with Coot

- Solvent addition using FindWaters utility

- Iterative refinement cycles with Refmac

Step 4: Validation and Output

- Generation of comprehensive PDB Validation Report

- Assessment of model quality metrics

- Final refined structure output

Protocol 3: Multi-Model Molecular Replacement

For challenging targets, using multiple prediction models can improve success rates and provide insights into conformational dynamics.

Step 1: Model Generation

- Generate structural models using multiple prediction servers (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, Rosetta, etc.)

- Collect models with diverse architectures and confidence patterns

Step 2: Model Preparation

- Assign B-factors using predictor confidence scores or calculate from accessible surface area (ASA) values [24]

- Trim regions with consistently low confidence across all models

- Generate ensemble models for regions with high conformational variability

Step 3: Multi-Model MR Search

- Perform MR searches with each model independently

- Compare solutions for consistency in core regions

- Note variations in surface loops and side-chain conformations

Step 4: Ensemble Analysis

- Superpose all successful solutions

- Identify regions of structural consensus versus variation

- Interpret variable regions as potential conformational states [24]

Step 5: Validation

- Calculate multi-conformer ensemble statistics

- Compare R-work and R-free for individual versus ensemble models

- Validate against biochemical and biophysical data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Molecular Replacement with Computational Models

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in MR | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | Protein structure prediction | Generate search models from sequence | Server/cloud or local installation |

| Phaser | Maximum likelihood MR | Rotation/translation searches | CCP4 Suite |

| MoRDa | Database MR search | Automatic domain-based MR | CCP4 Cloud/Web service |

| MrBUMP | Automated MR pipeline | Template search and model preparation | CCP4 Suite |

| CCP4 Cloud | Web-based crystallography | Integrated automated workflows | Cloud service |

| ModelCraft | Automated model building | MR model rebuilding and refinement | CCP4 Suite |

| Coot | Model visualization and editing | Manual model adjustment and validation | Standalone application |

| Phenix | Comprehensive refinement | Iterative structure refinement | Standalone suite |

The paradigm of molecular replacement has been fundamentally transformed by the availability of high-accuracy computational models. The integration of tools like AlphaFold2 into standardized crystallographic workflows has dramatically increased the success rate for structure determination, particularly for targets that lack close structural homologs. By following the protocols outlined in this Application Note and utilizing the appropriate metrics for model quality assessment, researchers can reliably leverage computational models to expand the scope of their structural studies. The emerging approach of using multiple models offers additional opportunities not only for solving challenging structures but also for gaining insights into protein dynamics directly from crystallographic data.

From Theory to Practice: A Toolkit for Building and Preparing High-Quality Search Models

Leveraging Homology Modeling with Tools like MODELLER and CaspR

Homology modeling is a foundational technique in structural biology that predicts the three-dimensional structure of a target protein based on its sequence similarity to one or more template proteins of known structure. When integrated with molecular replacement (MR), a primary method for solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography, homology modeling significantly expands the range of structures that can be determined experimentally. MR relies on placing a known structural model (the search model) within the crystallographic unit cell to approximate phase information. The success of MR is critically dependent on the accuracy of this search model. While traditional MR uses experimentally determined structures as templates, homology modeling allows researchers to generate search models for targets where only distantly related structures are available, effectively pushing the boundaries of what is solvable by crystallography.

The integration of automated bioinformatics tools and quality assessment protocols has transformed homology modeling from a specialized manual process into a robust, scalable pipeline for structural genomics. This application note details how the combined use of MODELLER for model generation and the CaspR web server for automated molecular replacement creates a powerful workflow for determining protein structures, particularly in cases where standard MR approaches fail.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Benchmarks

The Critical Link Between Model Quality and MR Success

The utility of a homology model in molecular replacement is quantitatively determined by its accuracy relative to the true, experimentally determined structure. Research has demonstrated that the Global Distance Test Total Score (GDTTS) serves as a reliable predictor of MR success. Models with GDTTS > 84 are generally sufficient to guarantee a successful MR solution, whereas those with GDT_TS < 80 rarely succeed [8]. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of C-α atoms is another key metric, with lower values indicating higher model quality.

Beyond global measures, local model accuracy is equally critical. The implementation of Model Quality Assessment Programs (MQAPs) that predict local deviations, such as MetaMQAPclust, can dramatically increase MR success rates. One study showed that while using comparative models alone provided only a 4.5% improvement in MR success over simple polyalanine templates, incorporating knowledge of the real local accuracy of the model boosted the success ratio by 101%. Using predicted local accuracy from MQAPs still yielded a substantial 45% improvement [8]. This underscores the importance of local quality assessment in preparing effective MR search models.

Performance Comparison of Homology Modeling Programs

A benchmark study evaluating six different homology modeling programs—Modeller, SegMod/ENCAD, SWISS-MODEL, 3D-JIGSAW, nest, and Builder—revealed that no single program outperforms all others in every test. However, Modeller, nest, and SegMod/ENCAD consistently performed better overall [25]. The performance characteristics of these tools are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Homology Modeling Programs

| Modeling Program | Modeling Approach | Relative Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODELLER | Satisfaction of spatial restraints | Top Tier | Fast; free for academic use; handles non-optimal alignments well |

| SegMod/ENCAD | Segment matching | Top Tier | Performs well despite being over 10 years old without development |

| nest | Rigid-body assembly | Top Tier | Uses stepwise approach changing one evolutionary event at a time |

| SWISS-MODEL | Rigid-body assembly | Middle Tier | Better for core regions; fast and free for academic use |

| 3D-JIGSAW | Rigid-body assembly | Middle Tier | Uses mean-field minimization methods for loops and side chains |

| Builder | Rigid-body assembly | Middle Tier | Uses mean-field minimization methods |

The selection of an appropriate modeling program should consider the specific requirements of the project. For challenging cases with potential alignment errors, MODELLER often demonstrates advantages due to its method of satisfying spatial restraints, which makes it more robust to alignment imperfections compared to rigid-body assembly methods [25].

Integrated Protocol: From Sequence to Molecular Replacement

This section provides a detailed workflow for leveraging homology modeling in molecular replacement, combining MODELLER for model construction with the CaspR server for automated MR screening.

The diagram below illustrates the complete integrated workflow from template identification through structure solution:

Stage 1: Template Identification and Alignment (Pre-Modeling)

Objective: Identify suitable structural templates and create a high-quality alignment for model building.

Procedure:

- Template Identification: Using the target protein sequence, search the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for structural homologs using tools like DALI (for structural similarity) or sequence-based methods like BLAST or HHblits. Select templates based on criteria including:

- Sequence identity (higher generally better, but models with >30% identity can be useful)

- Coverage of the target sequence

- Structural resolution and quality of the template

- Biological relevance (e.g., same protein family, similar ligands)

- Multiple Structure-Sequence Alignment: Generate a refined alignment using T-COFFEE (or its structure-enhanced version, 3D-COFFEE). This tool is critical as it:

- Combines sequence and structural information from multiple templates

- Computes a CORE index for each residue position, indicating alignment reliability (scale 0-100) [26]

- Provides the foundation for high-quality model generation in MODELLER

Technical Note: The CORE index from T-COFFEE is later used to identify and excise unreliably aligned regions before MR, a key step in the CaspR protocol.

Stage 2: Model Generation with MODELLER

Objective: Generate multiple high-quality homology models from the alignment.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare the alignment file in a format readable by MODELLER (e.g., PIR or FASTA format) and ensure template structures are in PDB format.

Model Generation Script: Create a MODELLER Python script with the following key parameters [27]:

Model Selection: Evaluate generated models using the DOPE-HR (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy - High Resolution) score or other MQA methods. Select the model with the lowest DOPE-HR score for subsequent steps [27].

Model Editing: Before proceeding to MR, excise unreliably aligned regions, particularly:

- Long insertions (typically >8 residues) in the target sequence

- Regions with low CORE index from the T-COFFEE alignment

- Flexible loops and terminal regions with high predicted deviation

Troubleshooting Tip: Generating a large number of models (100+) increases the probability of obtaining at least one model with sufficient accuracy for successful MR, especially for difficult targets with low sequence similarity to templates.

Stage 3: Automated Molecular Replacement with CaspR

Objective: Systematically screen homology models to identify MR solutions.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation for CaspR: Gather the required inputs:

- Target protein sequence in FASTA format

- Crystallographic structure factors in MTZ format (from CCP4)

- PDB identifiers of structural templates used in modeling

- Crystallographic information (space group, expected molecules per asymmetric unit)

CaspR Job Submission: Submit the job through the CaspR web server (http://igs-server.cnrs-mrs.fr/Caspr/). The server automatically executes:

- Model processing: Excises unreliable regions based on alignment quality

- MR screening: Tests multiple models (typically 10-100) using AMoRe

- Solution refinement: Pre-refines potential solutions using CNS

- Solution ranking: Ranks solutions by convergence of free and working R-factors

Result Interpretation: Monitor the CaspR progress report, which provides:

- Hierarchically organized summary sheets with increasing detail

- AMoRe statistics for all tested models

- Download links for the 10 highest-scoring pre-refined structures

Validation: In test cases, CaspR successfully found MR solutions where standard procedures with the original templates failed, including structures with less than 25% sequence identity between target and template [26]. For example, the structure of YecD (PDB: 1J2R) was solved exclusively using the CaspR procedure after standard MR failed.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Homology Modeling and Molecular Replacement

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Role in Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODELLER | Homology model building | Generates 3D models from sequence-structure alignments | Free for academic use [28] |

| CaspR | Automated molecular replacement | Integrated workflow from modeling to MR solution | Freely available web server [26] |

| T-COFFEE/3D-COFFEE | Multiple sequence-structure alignment | Produces reliable alignments with quality scores (CORE index) | Open source [26] |

| AMoRe | Molecular replacement | Performs MR searches with generated models | Part of CCP4 suite [26] |

| CNS | Crystallographic refinement | Pre-refines potential MR solutions | Freely available [26] |

| DALI | Structural similarity search | Identifies remote structural homologs for templating | Web server and standalone [8] |

| MetaMQAPclust | Model quality assessment | Predicts local accuracy to improve MR success | Available through GeneSilico Fold Prediction Metaserver [8] |

The integration of MODELLER and CaspR creates a powerful pipeline for extending the reach of molecular replacement in structural biology. By systematically generating and screening homology models, this approach can solve structures where conventional MR fails, particularly in the challenging 20-35% sequence identity range. The key to success lies in the rigorous application of quality assessment throughout the process—from alignment evaluation with T-COFFEE to model selection with DOPE-HR and local quality estimation with MQAPs.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several areas:

- Integration of deep learning-based MQA methods that show promise in outperforming traditional statistical potentials [29]

- Standardized benchmark datasets for evaluating MR performance with homology models, such as the newly proposed HMDM (Homology Models Dataset for Model Quality Assessment) [29]

- Improved template selection leveraging the growing PDB and more sensitive remote homology detection methods

- Automated model improvement cycles incorporating experimental density information

For researchers, this protocol demonstrates that investing in rigorous homology modeling and systematic screening can ultimately save considerable time and resources in structural determination, accelerating drug discovery and functional characterization of novel proteins.

In molecular replacement (MR), the success of phasing a target crystal structure is critically dependent on the quality of the search model used. Even minor errors in a model's atomic coordinates can significantly reduce the probability of obtaining a correct solution. The process of strategically identifying and removing unreliable regions of a model—trimming and pruning—has emerged as a fundamental step in preparing search models for MR. This approach transforms potentially unusable models into effective tools for structure determination by enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio in MR searches.

The expected log-likelihood gain (eLLG) provides a quantitative framework for predicting MR outcomes. The eLLG represents the log-likelihood gain on intensity expected from a correctly placed model and is calculated as a sum over reflections, dependent on the fraction of scattering accounted for by the model, the estimated model coordinate error, and measurement errors in the data [30]. Research has established that for non-polar space groups, most solutions with an LLG of 60 or greater are correct, while thresholds of 50 and 30 are sufficient for polar space groups and space group P1, respectively [30]. By removing poorly predicted regions, trimming and pruning directly improves the key parameters that contribute to eLLG, thereby increasing the probability of successful structure determination.

Quantitative Foundations for Trimming Decisions

Success Criteria for Molecular Replacement

Table 1: Molecular Replacement Success Criteria Based on LLG and TFZ Scores

| Confidence Level | Translation-Function Z-score (TFZ) | Log-Likelihood Gain (LLG) | Space Group Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| No solution | <5 | <25 | Applies to non-polar space groups |

| Unlikely | 5–6 | 25–36 | Applies to non-polar space groups |

| Possibly | 6–7 | 36–49 | Applies to non-polar space groups |

| Probably | 7–8 | 49–64 | Applies to non-polar space groups |

| Definitely | >8 | >64 | Lower thresholds apply to polar space groups and P1 |

The relationship between model quality and MR success has been quantitatively established through large-scale database studies. For the placement of the first model in molecular replacement, an LLG value approximately ten times the number of degrees of freedom is sufficient to be confident of success [30]. These LLG thresholds provide critical guidance for determining how extensively a model needs to be trimmed—models falling below these thresholds are strong candidates for pruning interventions.

Impact of Quality Assessment on MR Success

Table 2: Impact of Local Error Estimates on Molecular Replacement Success Rates

| Error Estimation Method | Models with LLG >50 | Success Rate | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| No error estimates | 74/431 | 17.2% | Baseline performance |

| ProQ2 error estimates | 175/431 | 40.6% | 136% increase over baseline |

| ProQ3D error estimates | 209/431 | 48.5% | 182% increase over baseline |

The implementation of local error estimates dramatically improves MR success rates. In a comprehensive study of 431 homology models for difficult MR targets, nearly half (48.5%) of models with ProQ3D error estimates achieved an LLG greater than 50, compared to only 17.2% of models without error estimates [31]. This represents a 182% improvement in success rate, clearly demonstrating the value of incorporating quality assessment in MR model preparation. Furthermore, adjusting B factors using quality estimates has been shown to improve LLG scores by over 50% on average [31].

Experimental Protocols for Model Trimming and Pruning

Protocol 1: Local Error Estimation with ProQ3D

Purpose: To predict residue-specific error estimates for protein models to guide trimming decisions.

Materials and Reagents:

- ProQ3D software (available from https://proq3.bioinfo.se/)

- Protein structural models in PDB format

- Target protein sequence in FASTA format

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare your protein model in PDB format. Ensure all atoms are properly formatted and residues are correctly numbered.

- ProQ3D Execution: Run ProQ3D on your model using either the web server or standalone version. The analysis typically takes several minutes depending on model size.

- Output Interpretation: ProQ3D outputs a quality score (S-score) between 0 and 1 for each residue, where 1 represents perfect quality.

- Score Transformation: Convert S-scores to predicted local error estimates (di) using the formula: di = d0(1/Si - 1)^1/2, where d0 = 3.0 Å [31].

- Error Threshold Application: Set a threshold for acceptable error (typically 3-6 Å) and flag residues exceeding this threshold for trimming.

- B-Factor Assignment: Insert predicted error estimates into the B-factor column of the output PDB file for use in molecular replacement.

Validation: The correlation between predicted and actual model quality (GDT_TS) should exceed 0.66 for ProQ3D [31]. Models with error estimates should show improved LLG scores during molecular replacement trials.

Protocol 2: AlphaFold Model Processing and Domain Splitting

Purpose: To optimize AlphaFold predictions for molecular replacement through confidence-based trimming and domain splitting.

Materials and Reagents:

- AlphaFold2 or ColabFold access

- Slice'N'Dice software for domain splitting

- Phaser MR software (within CCP4 or PHENIX)

Procedure:

- Model Generation: Generate protein structure predictions using AlphaFold2 or ColabFold with default parameters.

- Confidence Assessment: Extract per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT scores) from the model output. Residues with pLDDT < 70 are considered low confidence.

- Initial Trimming: Remove regions with consistently low confidence scores (pLDDT < 50-60).

- Domain Identification: For multi-domain proteins, use Slice'N'Dice to identify potential domain boundaries based on structural compactness.

- Domain Splitting: Separate the model into individual structural domains, creating separate PDB files for each domain.

- Independent MR Trials: Attempt molecular replacement with individual domains before proceeding with the full model.

- Complex Reconstruction: After placing individual domains, reconstruct the full structure through rigid-body refinement.