Navigating the Multiple Testing Maze: Strategies for False Discovery Control in High-Throughput Genomics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on correcting for multiple testing in high-throughput genomics experiments.

Navigating the Multiple Testing Maze: Strategies for False Discovery Control in High-Throughput Genomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on correcting for multiple testing in high-throughput genomics experiments. It explores the foundational statistical challenges posed by genome-wide association studies (GWAS), RNA-seq, and other omics technologies, where millions of correlated tests are performed simultaneously. The content details established and emerging methodological approaches—from Bonferroni to FDR control and advanced resampling techniques—for controlling false discoveries. It further offers practical troubleshooting advice for optimizing statistical power and addresses common pitfalls in datasets with strong intra-correlations. Finally, the article presents a comparative framework for validating results and discusses the implications of these methods for achieving reliable, reproducible findings in biomedical and clinical research.

The Multiple Testing Problem: Why Genomics Data Demands Special Attention

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the multiple testing problem and why is it critical in high-throughput genomics?

In high-throughput genomics, researchers often perform millions of simultaneous statistical tests on the same dataset (e.g., identifying differentially expressed genes or genetic variants). Each test carries its own chance of a false positive (Type I error). As the number of tests increases, so does the probability that at least one false positive will occur. If you perform 1,000,000 tests at a significance level of α=0.05, you would expect 50,000 false positives by chance alone. This inflation of false positives without proper correction is the core of the multiple testing problem, and it can lead to invalid biological conclusions [1] [2].

2. What is the difference between a p-value, a corrected p-value (e.g., Bonferroni), and a q-value?

- P-value: The probability of observing a result at least as extreme as the one you obtained, assuming the null hypothesis is true. In the context of multiple tests, this is often called the "nominal p-value" and does not account for the number of tests performed [1].

- Corrected p-value (e.g., Bonferroni): An adjusted p-value that controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER)—the probability of making at least one false discovery. The Bonferroni correction is calculated by dividing your significance threshold (α) by the number of tests (α/m). A result is significant if its nominal p-value is less than α/m. This method is very strict and can lead to many false negatives [1] [2].

- Q-value: This is the p-value analogue for the False Discovery Rate (FDR). The q-value of a test measures the proportion of false discoveries you are willing to tolerate among all discoveries called significant. A q-value of 0.05 means that 5% of the significant results in your list are expected to be false positives. Controlling the FDR is generally less stringent than controlling the FWER and is often more appropriate for exploratory genomic studies [1].

3. When should I use FWER correction versus FDR control?

The choice depends on the goal of your study and the cost of a false positive.

- Use FWER control (e.g., Bonferroni, Holm): When you need to be extremely confident that none of your declared discoveries are false positives. This is crucial in confirmatory studies or when follow-up validation is extremely expensive or difficult [2].

- Use FDR control (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg): In exploratory research where you are generating candidate hypotheses for future validation. The FDR approach is more powerful (less likely to produce false negatives) and allows you to identify a larger set of candidates, accepting that a small proportion of them will be incorrect [1] [2].

4. What are common data quality issues in HTS that can affect my statistical tests?

High-Throughput Sequencing data can contain various "pathologies" that introduce errors and biases, which in turn can distort p-values and lead to spurious findings. Common issues include:

- Sequence Read Errors: Incorrect base calls, particularly in regions with high or low GC content.

- Batch Effects: Technical variations introduced by processing samples on different days, by different personnel, or using different reagent batches.

- Library Preparation Biases: Artefacts from PCR amplification or adapter contamination.

- Alignment Artefacts: Reads that are incorrectly mapped to the reference genome.

These issues must be diagnosed and treated through rigorous quality control (QC) procedures before proceeding to statistical testing. Failure to do so can invalidate your results [3].

5. How do I determine the correct multiple testing method for my specific HTS application?

The optimal method can vary based on your experimental design and the specific HTS application. The table below summarizes recommended practices for common scenarios.

Table: Guide to Multiple Testing Correction for Common HTS Applications

| HTS Application | Typical Analysis Goal | Recommended Correction Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) | Identify genetic variants associated with a trait/disease. | Bonferroni (FWER control) | The number of independent tests is high but finite. The severe penalty is accepted as a standard to ensure robust, replicable hits. |

| RNA-Seq (Differential Expression) | Identify genes that are differentially expressed between conditions. | Benjamini-Hochberg (FDR control) | A large number of tests are performed on often correlated genes. FDR provides a good balance between discovery and false positive control. |

| ChIP-Seq (Peak Calling) | Identify genomic regions enriched for protein binding (peaks). | FDR control on peak scores | The comparison is often against a background model or control sample. FDR is well-suited for generating a list of candidate peaks. |

| Metagenomic Analysis | Identify differentially abundant taxa or pathways. | FDR control | The data is high-dimensional and compositional. FDR is commonly used, sometimes alongside specific methods for compositional data. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High False Discovery Rate Even After Correction

Symptoms: After applying FDR correction, a functional validation assay shows that a large percentage of your "significant" hits are not real.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Quality Control (QC). Low-quality sequence data or batch effects are inflating test statistics for non-biological reasons.

- Solution: Re-inspect your raw data. Use tools like FastQC and check for batch effects with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Consider using linear models that can incorporate and adjust for known batch effects [3].

- Cause: Violation of Test Assumptions. The statistical test you used (e.g., t-test) may rely on assumptions (like normality of data) that are not met by your dataset.

- Solution: Use non-parametric tests (e.g., Wilcoxon rank-sum test) or data transformation (e.g., VST for RNA-seq counts) to ensure your data better meets the test's assumptions.

- Cause: Weak Biological Effect and/or Underpowered Study.

- Solution: Increase your sample size to improve the power of your experiment. If this is not possible, use a less stringent FDR threshold, but clearly acknowledge this in your reporting and interpret results with caution.

Problem: Overly Stringent Correction Yields No Significant Hits

Symptoms: After applying a multiple testing correction (especially Bonferroni), no results remain statistically significant.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The Bonferroni Correction is Too Conservative. Bonferroni assumes all tests are independent, which is rarely true in genomics, leading to a loss of statistical power.

- Cause: The Experimental Effect is Subtle.

- Solution: As above, increasing sample size is the most reliable solution. You can also focus your hypothesis by pre-defining a smaller set of genes/pathways of interest based on prior literature, thereby reducing the number of tests performed.

Problem: Inconsistent Replication of Results in a Follow-up Study

Symptoms: Significant hits from your initial HTS experiment fail to validate in a new, independent dataset.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete Multiple Testing Correction in the Initial Study. The original findings may have been false positives that slipped through due to an inappropriate or poorly applied correction method.

- Solution: Ensure both the initial and follow-up studies use rigorous, well-accepted multiple testing corrections. Report the specific method and threshold used [4].

- Cause: Differences in Experimental Conditions or Populations.

- Solution: Carefully control and document all experimental protocols. Standardize sample processing, library preparation, and sequencing platforms across studies where possible. Ensure the clinical or biological cohorts are well-matched.

Experimental Protocols

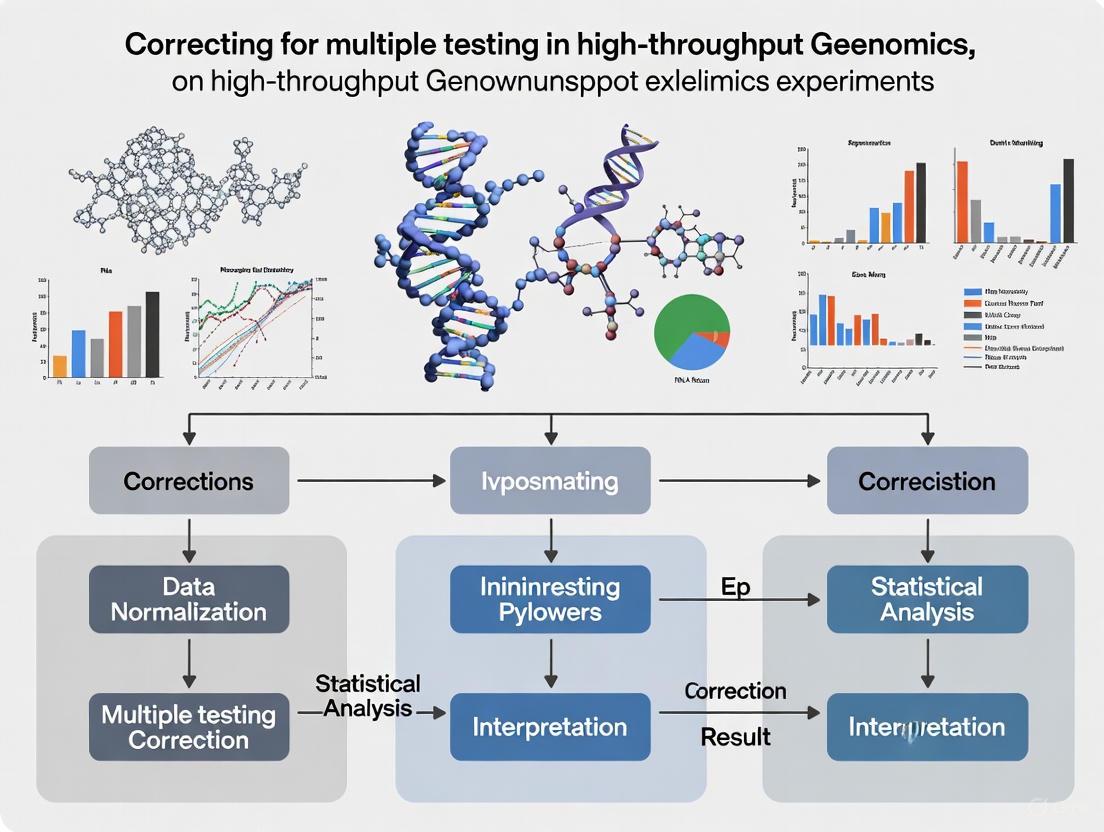

Protocol 1: Basic Workflow for Multiple Testing Correction in an HTS Experiment

This protocol outlines the standard bioinformatic steps for statistical testing and correction in a typical HTS analysis, such as a differential expression RNA-seq study.

1. Primary & Secondary Analysis: - Perform sequencing and generate raw reads (FASTQ files). - Align reads to a reference genome. - Generate a count matrix (e.g., reads per gene per sample) [5].

2. Statistical Testing: - For each feature (e.g., gene), perform a statistical test comparing conditions. This generates a test statistic and a nominal p-value for every feature.

3. Apply Multiple Testing Correction:

- Compile all nominal p-values from your tests into a list.

- Choose a correction method based on your experimental goal (see FAQ #5).

- For FDR Control (Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure):

a. Sort the p-values from smallest to largest.

b. Assign a rank (r) to each p-value (1 for the smallest).

c. Calculate the adjusted p-value (q-value) for each original p-value (p) as: q = (p * m) / r, where m is the total number of tests.

d. To identify significant hits at a given FDR (e.g., 5%), find all genes where their q-value < 0.05 [1].

4. Interpretation and Reporting: - Report the list of significant features, their test statistics, nominal p-values, and corrected q-values (or FWER-adjusted p-values). - Clearly state the multiple testing correction method and significance threshold used in your methodology [4].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in this workflow.

Protocol 2: Quality Control to Mitigate Multiple Testing Problems

Robust QC is essential to prevent technical artefacts from causing false positives, which multiple testing corrections alone cannot fully resolve [3].

1. Pre-Sequencing QC: - Assess DNA/RNA quality using instruments like Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to ensure high-quality input material [6]. - Quantify nucleic acids accurately using fluorescence-based assays (e.g., Qubit).

2. Post-Sequencing QC: - Use tools like FastQC to evaluate read quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences. - Check alignment metrics (e.g., mapping rate, duplication rate, insert size).

3. Detect and Correct for Batch Effects: - Perform PCA or other clustering methods on the experimental data. - If batches are evident, include "batch" as a covariate in your statistical model to adjust for its effect during testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Materials for High-Throughput Sequencing Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Kits contain enzymes, buffers, and adapters to convert RNA/DNA into a sequenceable library. | Protocol depends on application (e.g., RNA-seq, ChIP-seq). Kits are platform-specific (Illumina, PacBio) [5] [7]. |

| Indexes (Barcodes) | Short, unique DNA sequences added to each sample's library during preparation. Allows pooling and sequencing of multiple libraries in one run, then computationally deconvoluting the data. | Submitted in i7-i5 format (e.g., CCGCGGTT-AGCGCTAG). Critical for multiplexing [6]. |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess the quality, size distribution, and concentration of nucleic acids before and after library prep. | TapeStation, Bioanalyzer, LabChip (for fragment analysis); Qubit (for accurate concentration) [6]. |

| PhiX Control | A well-characterized viral genome spiked into sequencing runs (often 1%). Serves as a quality control for cluster generation, sequencing, and alignment. Essential for low-diversity libraries [6]. | |

| Custom Sequencing Primers | Specialized primers required for certain library preparation protocols (e.g., Nextera). | Must be provided to the sequencing facility if the protocol deviates from standard ones [6]. |

| Clonal Amplification Reagents | For second-generation sequencing (Illumina, Ion Torrent): reagents for bridge PCR or emulsion PCR to amplify single DNA fragments into clusters. | Included in platform-specific sequencing kits [7]. |

| SMRTbell Templates | For PacBio SMRT sequencing: hairpin adapters are ligated to DNA fragments to create circular templates that enable real-time, long-read sequencing. | Key reagent for third-generation sequencing [7]. |

| Flow Cells | The solid surface (glass slide for Illumina, semiconductor chip for Ion Torrent) where clonal amplification and sequencing occur. | The type of flow cell determines the total data output of a run [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing an Unacceptably High Number of False Positives

Problem: After running thousands of statistical tests, a surprisingly large number of significant results appear, many of which are likely false positives.

Diagnosis: This is the classic multiple testing problem. When you perform a large number of hypothesis tests (e.g., for 10,000 genes), using a standard significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.05) will yield approximately 500 false positives even if no true differences exist [8]. Your analysis is likely missing a proper correction for multiple comparisons.

Solution: Apply a multiple testing correction procedure.

- If you cannot tolerate any false positives in your entire study (e.g., in a safety-critical validation), use a method that controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), such as the Bonferroni correction [9] [10].

- If you are conducting an exploratory analysis (e.g., identifying candidate genes for further study) and can accept a small proportion of false discoveries, use a method that controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR), such as the Benjamini-Hochberg (B-H) procedure [11] [12] [8].

Guide 2: Choosing Between FWER and FDR Control

Problem: You are unsure whether to control the FWER or the FDR for your specific high-throughput experiment.

- Diagnosis: The choice depends on the goal and context of your research [12] [13].

- Solution: Use the following decision workflow:

Guide 3: My FDR-Adjusted Results Are Too Conservative

Problem: After applying a multiple testing correction, notably the stringent Bonferroni method, no results remain significant, and you suspect true positives are being missed (false negatives).

Diagnosis: The Bonferroni correction is highly conservative, especially when testing a very large number of hypotheses or when tests are correlated [8] [10] [14]. It controls the FWER but leads to a substantial loss of statistical power.

Solution:

- Switch to FDR Control: For most high-throughput genomics experiments (e.g., RNA-seq, GWAS), FDR control is the more appropriate standard as it offers a better balance between discovering true positives and limiting false positives [12] [15].

- Use a More Powerful FWER Method: If FWER control is mandatory, consider Holm's step-down procedure, which is uniformly more powerful than Bonferroni while still providing strong FWER control [16] [9].

- Use Modern Covariate-Informed Methods: If you have additional information about your tests (e.g., gene expression level, prior probability of association), use modern FDR methods like Independent Hypothesis Weighting (IHW) or FDR Regression (FDRreg). These methods can increase power by incorporating informative covariates without sacrificing FDR control [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between FWER and FDR?

- FWER is the probability of making at least one false discovery (Type I error) among all the hypotheses tested in a family or experiment. Controlling it means you are 95% confident that there are zero false positives in your results [9] [13].

- FDR is the expected proportion of false discoveries among all the hypotheses you reject. An FDR of 5% means that you can expect that 5% of the items you call "significant" are, in fact, false positives [11] [12].

FAQ 2: When should I use the Bonferroni correction versus the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure?

- Use Bonferroni when the consequences of a single false positive are severe and you need to be confident that not a single error exists in your list of findings. This is typical for confirmatory studies [10].

- Use Benjamini-Hochberg (B-H) in exploratory studies (e.g., target discovery), where the goal is to generate a list of candidates for future validation. The B-H procedure is less conservative and allows you to find more true positives while explicitly controlling the proportion of false ones (FDR) [11] [12] [8].

FAQ 3: What are q-values, and how do they relate to p-values and FDR?

- A p-value measures the probability of observing your data if the null hypothesis is true. A threshold of 0.05 controls the false positive rate for that single test [11] [1].

- A q-value is the FDR analogue of the p-value. It is the minimum FDR at which a specific test (e.g., for a given gene) may be called significant. For example, a gene with a q-value of 0.03 means that 3% of genes with q-values as small or smaller than this one are expected to be false positives [11] [1] [12].

FAQ 4: My statistical tests are correlated (e.g., due to linkage disequilibrium in GWAS). Do standard corrections still work?

- Bonferroni assumes independence and is often overly conservative when tests are positively correlated, leading to a loss of power [10] [14].

- Benjamini-Hochberg is valid under positive dependence and is generally robust for genetic data [15].

- For more accurate corrections that fully account for the complex correlation structure between markers (like in genome-wide association studies), specialized methods such as SLIDE have been developed. These methods are more accurate and powerful than Bonferroni or block-based approaches [14].

FAQ 5: What are "modern FDR methods," and when should I consider using them?

Modern FDR methods (e.g., IHW, BL, AdaPT) go beyond classic procedures by using an informative covariate to prioritize hypotheses. If you have data that predicts whether a test is likely to be a true positive (e.g., gene expression level, SNP functionality, prior p-values from another study), these methods can use it to weight the tests, increasing your power to make discoveries without inflating the FDR. They are particularly useful when you have prior biological knowledge about your tests [12].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Core Definitions and Error Rate Comparisons

| Feature | Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) | False Discovery Rate (FDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Probability of making one or more false discoveries | Expected proportion of false discoveries among all rejected hypotheses [11] [9] |

| Controls For | Any single false positive across the entire experiment | The rate of false positives within the set of discoveries [11] |

| Interpretation | "The probability that this list contains at least one false positive." | "On average, 5% of the items in this list are false positives." |

| Typical Use Case | Confirmatory studies, clinical trials, safety testing [10] | Exploratory data analysis, high-throughput genomics (e.g., RNA-seq, GWAS) [12] [15] |

| Common Methods | Bonferroni, Holm, Šidák [9] | Benjamini-Hochberg (BH), Storey's q-value [11] [12] |

| Conservatism | High (stringent) | Less conservative (more powerful) [12] |

Table 2: Overview of Key Multiple Testing Correction Procedures

| Method | Error Rate Controlled | Brief Methodology | Key Assumptions / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni | FWER | Rejects any hypothesis with ( p \leq \alpha/m ), where ( m ) is the total number of tests [9]. | Very conservative; assumes tests are independent. |

| Holm Step-Down | FWER | Orders p-values ( P{(1)}...P{(m)} ) and rejects hypotheses 1 to ( k-1 ), where ( k ) is the smallest rank at which ( P_{(k)} > \alpha/(m + 1 - k) ) [16] [9]. | More powerful than Bonferroni; strong FWER control. |

| Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) | FDR | Orders p-values. Finds the largest ( k ) where ( P_{(k)} \leq (k/m)\alpha ). Rejects all hypotheses 1 to ( k ) [16] [11] [15]. | Robust under positive dependence. Industry standard for FDR control. |

| Storey's q-value | FDR | Estimates the proportion of true null hypotheses (( \pi_0 )) from the p-value distribution and uses it to compute q-values, which are FDR analogues for each test [11] [12]. | Can be more powerful than BH, especially when many true alternatives exist. |

| Independent Hypothesis Weighting (IHW) | FDR | Uses an informative covariate to weight p-values, then applies a weighted BH procedure. More weight is given to hypotheses more likely to be alternative [12]. | Increases power when a informative covariate is available. Covariate must be independent of p-value under the null. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating FDR Methods Using DNA Methylation Datasets

This protocol is adapted from a study that used the known biology of X-chromosome inactivation to benchmark the performance of different multiple comparison procedures [16].

1. Experimental Rationale:

- Due to X-chromosome inactivation, CpG sites on the X chromosome show predictable differential methylation patterns between healthy males (one X chromosome, mostly unmethylated) and females (two X chromosomes, one heavily methylated) [16].

- This biological truth provides a "ground truth" for evaluating FDR/FWER methods: effective methods should correctly identify these X-linked sites as significant.

2. Required Materials and Data:

- Dataset: Publicly available high-throughput DNA methylation dataset (e.g., from Illumina's GoldenGate Methylation BeadArray or Infinium HumanMethylation27 assay) downloaded from a repository like Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [16].

- Samples: Must include normal, healthy subjects with accurately annotated gender.

- Software: Statistical computing environment (e.g., R/Bioconductor) with packages for applying multiple testing corrections.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Data Preparation: Preprocess the methylation dataset (normalization, quality control). Extract beta-values (measures of methylation level) for all CpG sites. 2. Hypothesis Testing: For each CpG site, perform a statistical test (e.g., t-test) to compare methylation levels between the male and female groups. Record the resulting p-value for all sites. 3. Apply Multiple Testing Corrections: Apply a set of multiple comparison procedures to the list of p-values. The evaluated methods should include: - FWER-control: Holm's step-down procedure. - FDR-control: Benjamini-Hochberg, Benjamini-Yekutieli, and the q-value method. 4. Performance Evaluation: Compare the output of each method against the biological ground truth. - True Positives (Sensitivity): Count the number of significant CpG sites located on the X chromosome. A higher count indicates better sensitivity. - False Positives (Specificity): Count the number of significant CpG sites located on autosomes (non-sex chromosomes). A lower count indicates better specificity. - Observed FDR: For the set of discoveries, calculate the proportion that are located on autosomes (which are presumed to be null in this specific gender comparison) [16].

4. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for the Methylation Benchmarking Experiment

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Methylation BeadArray | High-throughput profiling of DNA methylation levels at specific CpG sites across the genome. | Illumina GoldenGate Methylation Cancer Panel I or Infinium HumanMethylation27 [16]. |

| Gender-Annotated Samples | Provides the phenotypic groups (Male vs. Female) for the differential methylation analysis. | Must be from normal, healthy subjects to ensure the observed signal is due to X-inactivation. |

| Statistical Software (R/Bioconductor) | Provides the computational environment for data preprocessing, statistical testing, and application of multiple testing corrections. | Packages like limma for differential analysis and stats for p-value adjustment are essential. |

| Reference Genome Annotation | Allows for the mapping of CpG sites to their genomic locations (X chromosome vs. autosomes). | Required for classifying discoveries as true positives (X-linked) or false positives (autosomal). |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my analysis failing to find any significant hits?

Problem: You have applied a Bonferroni correction to your genome-wide association study (GWAS) or gene expression analysis and are observing no statistically significant results, even for effects you believe are biologically real.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of the Bonferroni correction's overly conservative nature. The correction is designed to stringently control Type I errors (false positives) but does so at the expense of severely inflating Type II errors (false negatives), meaning you are likely missing true positive findings [17] [18] [19].

Solution:

- Check Statistical Power: The Bonferroni correction can make it difficult to detect true effects, especially when sample sizes are small or the number of tests is very large [18]. In one scenario, with a sample size of 3,929 and 24 tests, an effect needed to pass the Bonferroni threshold was over 50% larger than that needed for a nominal threshold [20].

- Consider Alternative Methods: If controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR) is acceptable for your research question, switch to a less conservative method like the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure [19] [21]. For stricter control that is more powerful than Bonferroni, use the Holm-Bonferroni method, a step-up procedure that is uniformly more powerful [20] [22].

Why do my results seem to contradict established biology?

Problem: After applying a multiple testing correction, your list of significant genes or biomarkers does not include known players in the biological pathway you are studying.

Diagnosis: The Bonferroni correction applies the same stringent penalty to every test, regardless of the prior biological plausibility or importance of the hypothesis [23]. This can drown out signals from factors with established, albeit modest, effects.

Solution:

- Implement a Hierarchical Approach: Do not apply a single correction across all tests. Prioritize your analyses. Use a strict correction (like Bonferroni) for exploratory, hypothesis-free scans, but use more lenient corrections (or none at all) for testing specific, pre-specified hypotheses based on strong prior evidence [17].

- Report Effect Sizes: Always report and consider the effect sizes and confidence intervals alongside p-values. A result that is not statistically significant after correction may still have a meaningful effect size that warrants further investigation [19].

My analysis produces thousands of significant results with FDR correction. Is this reliable?

Problem: When using an FDR-controlling method like Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) on a dataset with highly correlated features (e.g., gene expression, methylation data), you get an unexpectedly high number of significant hits.

Diagnosis: In datasets with strong intra-correlations (e.g., due to linkage disequilibrium in genetics or co-regulation in transcriptomics), FDR methods can sometimes produce counter-intuitive results. While the average false discovery rate is controlled, in specific datasets where false positives do occur, they can occur in large, correlated clusters, leading to a high number of false findings in that particular analysis [21].

Solution:

- Use Dependency-Aware Methods: For genetic studies, use methods designed for correlated data, such as permutation testing or other LD-aware multiple testing corrections [21].

- Validate with Synthetic Null Data: Generate negative control datasets (e.g., by shuffling labels) to understand the behavior of your multiple testing procedure in the absence of any true effect. This helps identify the caveat of high false positives in correlated data [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental drawback of the Bonferroni correction?

The primary drawback is that it is overly conservative. It reduces the significance threshold so severely that it dramatically increases the chance of Type II errors (false negatives)—failing to detect genuine biological signals [17] [18]. This is because it controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), the probability of making even one false discovery, which is often an unnecessarily strict standard for exploratory high-throughput biology [19].

When is it appropriate to use the Bonferroni correction?

The Bonferroni correction is best suited for situations where:

- The universal null hypothesis (that all null hypotheses are true simultaneously) is of direct interest [17].

- You are testing a small to moderate number of hypotheses [20] [24].

- The cost of a single false positive discovery is exceptionally high, warranting strict control [20].

- The tests are independent, as it assumes no correlation between tests [23].

What are the best alternative methods for genomic studies?

The choice of alternative depends on your study's goal and the data's structure. The table below summarizes the most common alternatives to Bonferroni.

| Method | Controls | Best Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holm-Bonferroni [22] | FWER | When you need strict error control but more power than Bonferroni. | More powerful step-down procedure; uniformly superior to Bonferroni. |

| Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) [19] [21] | FDR | Exploratory studies where you can tolerate some false positives to find more true signals. | Less conservative; provides a better balance between false positives and negatives. |

| Benjamini-Yekutieli (BY) [19] | FDR | When tests are dependent or under any form of correlation. | Controls FDR under any dependency structure, but is more conservative than BH. |

| Permutation Testing [21] | FWER/FDR | Genetic studies with strong correlations (e.g., LD); considered a gold standard. | Accounts for the specific correlation structure of the dataset. |

How does multiple testing correction impact power and error rates?

Applying a correction like Bonferroni directly trades one type of error for another. The following table compares the effect of using a nominal threshold versus the Bonferroni correction on error rates.

| Scenario | Type I Error (False Positive) Risk | Type II Error (False Negative) Risk | Statistical Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction (e.g., p < 0.05) | High (e.g., 64% with 20 tests) [24] | Low | High (but results are unreliable) |

| Bonferroni Correction | Controlled to 5% Family-Wise [25] | High [17] [18] | Low, especially with many tests [18] |

| FDR Correction (e.g., BH) | Controls expected proportion of false positives to 5% [19] | Lower than Bonferroni | Higher than Bonferroni, better balance [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comparing Multiple Testing Methods on Simulated Data

Objective: To evaluate the performance of Bonferroni, Holm-Bonferroni, and Benjamini-Hochberg corrections in terms of false positives and false negatives using a simulated dataset with known true and null effects.

Materials:

- Statistical software (R or Python recommended)

statsmodelslibrary (Python) orp.adjustfunction (R)

Methodology:

- Data Simulation: Simulate a dataset with

mfeatures (e.g., m=10,000). For a small subset (e.g., 100) of these features, simulate a true effect by creating a systematic difference between two experimental groups. The remaining 9,900 features should have no true effect (null true). - Hypothesis Testing: Perform an independent two-sample t-test for each feature to compare the two groups, resulting in

mp-values. - Apply Corrections:

- Calculate Performance Metrics:

- False Positives: Count the number of null features declared significant.

- False Negatives: Count the number of true-effect features not declared significant.

- Sensitivity (Power): Proportion of true-effect features correctly identified.

- Validation: Repeat the simulation 100 times and average the results to get stable estimates of each method's performance.

This protocol allows researchers to visually confirm that Bonferroni typically yields the fewest false positives but also the most false negatives, while FDR methods offer a more balanced profile.

Workflow Diagram: Selecting a Multiple Testing Strategy

The diagram below outlines a decision workflow to help researchers select an appropriate multiple testing correction method.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key statistical "reagents" — the methods and concepts essential for properly handling multiple testing in genomics.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) | The probability of making one or more false discoveries among all hypotheses tested. Bonferroni and Holm-Bonferroni control this rate [25] [22]. |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | The expected proportion of false discoveries among all rejected hypotheses. Methods like Benjamini-Hochberg control this rate, offering a less strict alternative to FWER [19] [21]. |

| Holm-Bonferroni Method | A sequential step-down procedure that controls FWER but is uniformly more powerful than the standard Bonferroni correction [20] [22]. |

| Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) Procedure | A step-up procedure that controls the FDR. It is less conservative than FWER-controlling methods and is widely used in exploratory genomic analyses [19]. |

| Permutation Testing | A robust, non-parametric method that accounts for the specific correlation structure of the data by creating an empirical null distribution. Often considered a gold standard in genetics [21]. |

| Synthetic Null Data | Datasets generated by shuffling experimental labels or simulating data under the null hypothesis. Used to validate and understand the performance of multiple testing procedures [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inflated Type I Error in Multipoint Linkage Analysis

Problem: Multipoint linkage analysis is showing higher than expected false positive rates, potentially due to unaccounted linkage disequilibrium between markers.

Explanation: Most multipoint linkage analysis programs assume linkage equilibrium between markers when inferring parental haplotypes. When this assumption is violated due to LD between closely-spaced markers, it interferes with estimating Identity-by-Descent sharing, leading to increased false positive rates for linkage. This problem is exacerbated when parental genotypes are unavailable [26].

Solution: Implement the following workflow to identify and mitigate LD-induced false positives:

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Assess Marker Density: Evaluate your SNP density. Studies show markers more than 0.3 cM apart generally don't cause large Type I error inflation, but dense maps (e.g., 0.25 cM) show substantial inflation [26].

- Evaluate Missing Data Patterns: Check if missing founder genotypes or parental genotypes in middle generations are present, as these increase Type I error rates corresponding to the proportion of missing data [26].

- Identify High-LD Regions: Use software like SNPLINK to automatically detect and remove markers in high LD prior to analysis [26].

- Consider Alternative Software: Implement tools like MERLIN which offer haplotype sampling options to produce correct results in the presence of LD [26].

- Validate with Appropriate Controls: For case-control studies, ensure proper estimation of allele frequencies. Method L (which uses conditional distribution of genotypes) shows better performance than traditional methods for non-random samples [27].

Guide 2: Managing False Positives in sQTL Detection

Problem: Traditional sQTL detection methods are missing true disease-associated genetic variants due to statistical limitations.

Explanation: Existing sQTL detection methods have limitations in comprehensive splicing characterization, statistical model calibration, and consideration of covariates affecting detection power. This leads to both false positives and false negatives in identifying true splicing quantitative trait loci [28].

Solution: Implement the MAJIQTL statistical framework:

Implementation Steps:

- Comprehensive Splicing Characterization: Use MAJIQ splicing quantification integrated with Salmon transcript quantification to capture from classic splicing events to complex splicing patterns [28].

- Weighted Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Gaussian process regression to model the relationship between detection power covariates and local false discovery rate, then reallocate family-wise error rate budget accordingly [28].

- β-Binomial Regression Modeling: Replace traditional linear models with β-binomial regression which better handles discreteness and heteroscedasticity of splicing data [28].

- Composite Testing Strategy: Test H0: |β| ≤ θ vs H1: |β| > θ where θ is an effect size threshold, creating nonlinear decision boundaries that require stricter evidence for high-variance estimates [28].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the minimum safe distance between SNP markers to avoid LD-induced false positives in linkage analysis?

A: Research indicates that SNP markers more than 0.3 cM apart generally do not cause large increases in Type I error rates. However, in dense maps (e.g., 0.25 cM), removing genotypes on founders and/or parents in the middle generation causes substantial inflation of Type I error rates. Long high-LD blocks have severe effects on Type I error rates regardless of distance [26].

Q2: How does missing parental genotype data affect false positive rates?

A: Missing parental genotypes substantially increase Type I error rates in the presence of LD. Studies show that removing genotypes on founders and/or parents in the middle generation causes substantial inflation, which corresponds to the increasing proportion of persons with missing data. Adding either flanking markers in equilibrium or additional unaffected siblings may decrease but not eliminate this inflation [26].

Q3: What statistical methods can improve sQTL detection while controlling false positives?

A: The MAJIQTL framework addresses three key limitations: comprehensive splicing characterization, weighted multiple testing correction using Gaussian process regression, and β-binomial regression models for effect size inference. This approach detected 87% more Alzheimer's disease and 92% more Parkinson's disease GWAS signal colocalizations compared to traditional methods [28].

Q4: How should researchers handle non-random samples in LD analysis?

A: Traditional methods like Hill's "chromosome counting" method assume random sampling and can produce severely biased estimates with non-random samples. Method L, which uses information from conditional distribution of genotypes at one locus given genotypes at the other, shows robustness to non-random sampling and provides more accurate estimates of disequilibrium parameters [27].

Table 1: Effects of SNP Density and Missing Data Patterns on Type I Error Rates

| SNP Density | Missing Data Pattern | Type I Error Inflation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 cM | Founders and parents in middle generation removed | Substantial inflation | Increase marker spacing >0.3 cM or use LD-pruning tools |

| 0.3 cM | Most patterns | No large increase | Generally safe for analysis |

| 0.6 cM | All patterns | Minimal effect | Standard density for linkage panels |

| 1-2 cM | Any pattern | No significant inflation | Lower density but less informative |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of LD Estimation Methods with Non-Random Samples

| Method | Sampling Scheme | Bias | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hill's Method (H) | Random samples | Minimal bias | Only with truly random samples |

| Hill's Method (H) | Case-control (non-random) | Seriously biased, estimates outside theoretical boundaries | Not recommended for non-random samples |

| Method L | Random samples | Minimal bias, smaller standard deviations | Preferred for all sample types |

| Method L | Case-control (non-random) | Adequate estimates in all simulated situations | Recommended for non-random samples |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Managing LD and Multiple Testing

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SNPLINK Software | Automatically removes markers in LD prior to analysis | Multipoint linkage analysis with dense SNP markers |

| MERLIN v1.0.0 | Haplotype sampling option for correct results in LD presence | Family-based linkage analysis |

| MAJIQTL Framework | Comprehensive sQTL detection with improved multiple testing | RNA splicing QTL studies |

| DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform | Ultra-rapid secondary genomic analysis (~30x human genome in ~25 min) | High-throughput sequencing data analysis |

| Illumina Connected Analytics | Cloud-based data management for multi-omics data | Large-scale genomic studies requiring multiple testing correction |

A Practical Toolkit: Key Methods for Multiple Testing Correction in Genomic Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core problem that Bonferroni and Šidák corrections aim to solve? When you perform multiple statistical tests simultaneously on a high-throughput genomics dataset (e.g., testing thousands of genes or methylation sites), the probability of incorrectly flagging at least one non-significant result as significant (a Type I error or false positive) increases dramatically. This is known as the multiple comparisons problem [2]. For example, if you run 1,000 independent tests at a significance level (α) of 0.05, you can expect approximately 50 false positives by chance alone [2] [29]. Bonferroni and Šidák corrections adjust the significance threshold to control this inflated risk of false positives.

2. How do the Bonferroni and Šidák corrections work mathematically? Both methods adjust the significance level (α) or the p-values based on the total number of tests performed (m). The table below summarizes the key formulas.

| Method | Adjusted Significance Level (α_adj) | Adjusted P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni | ( \alpha_{adj} = \frac{\alpha}{m} ) [30] [31] | ( p_{adj} = \min(p \times m, 1) ) [29] |

| Šidák | ( \alpha_{adj} = 1 - (1 - \alpha)^{1/m} ) [30] [32] | ( p_{adj} = 1 - (1 - p)^{m} ) [33] |

3. What is the key difference between controlling the FWER and the FDR?

- Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER): This is the probability of making at least one false discovery (Type I error) among all the hypotheses tested. Both Bonferroni and Šidák corrections are designed to control the FWER, making them very stringent [2] [29].

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): This is the expected proportion of false discoveries among all the tests declared significant. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure controls the FDR, which is generally less conservative than FWER-controlling methods and allows for more discoveries at the cost of a slightly higher false positive rate [30] [32] [2].

4. When should I use Bonferroni or Šidák over FDR methods? The choice depends on the goal and context of your study:

- Use Bonferroni or Šidák in confirmatory studies where the cost of a single false positive is very high, such as in clinical trial validation or when reporting a final, limited set of candidate biomarkers [29]. They are best suited when the number of tests is not extremely large (e.g., from dozens to a few hundred) [29].

- Use FDR-controlling methods (like BH) in exploratory studies where the goal is to identify a larger set of potential candidates for future validation, such as in initial genome-wide screens [30] [29]. FDR is preferred when analyzing tens of thousands of features (e.g., in transcriptomics) [34].

5. What are the main limitations of these corrections?

- Over-Conservatism & Loss of Power: The primary criticism, especially of the Bonferroni method, is that it can be overly strict. By drastically lowering the significance threshold, it increases the risk of Type II errors (false negatives), meaning you might miss truly important biological signals [31] [33].

- Assumption of Independence: Both methods assume that the statistical tests are independent of one another [30] [32]. This assumption is often violated in genomics data where variables are frequently correlated (e.g., due to linkage disequilibrium in genetics, or co-regulation in gene expression) [30] [33]. When tests are positively correlated, these corrections become even more conservative [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Overly Conservative Results and Loss of Power

Symptoms: After applying a Bonferroni or Šidák correction, no results remain significant, even though you have strong prior biological evidence that effects should exist.

Solutions:

- Switch to FDR Control: For exploratory analyses, consider using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the False Discovery Rate instead of the FWER. This method is less stringent and typically yields more discoveries while still providing a meaningful error rate metric [30] [29].

- Use a Stepwise Correction: Apply a sequentially rejective method like the Holm-Bonferroni correction (a step-down method). This method offers more power than the single-step Bonferroni correction while still controlling the FWER. It adjusts p-values in a stepwise fashion from smallest to largest, making it less conservative [31] [32] [29].

- Incorporate Correlation Structure: If your data features highly correlated variables (e.g., CpG sites in a gene, or SNPs in LD), consider methods that estimate the "effective number of independent tests." The Li and Ji (LJ) or Gao et al. (GEA) methods use the correlation matrix's eigenvalues to compute a reduced number of tests (m_eff) for use in Bonferroni or Šidák corrections [33].

- Employ Permutation-Based Methods: Use permutation testing, which is often considered the gold standard as it empirically derives the null distribution of your test statistics while preserving the correlation structure of the data. However, this can be computationally intensive for very large datasets [33] [14].

Problem 2: Handling Non-Independent Tests in Genomic Data

Symptoms: Your data involves correlated features (e.g., genes in a pathway, SNPs in linkage disequilibrium, or correlated methylation sites), and you are concerned that standard corrections are inappropriate.

Solutions:

- Estimate the Effective Number of Tests: For candidate gene or region-based analyses, use methods like Li and Ji (LJ) or Gao et al. (GEA). These methods calculate an effective number of independent tests (meff) based on the correlation matrix between your variables. You can then use this meff in a Šidák correction [33].

- Protocol Outline: a. Calculate the correlation matrix (e.g., Pearson) for your genomic features (e.g., M-values for CpG sites) [33]. b. Compute the eigenvalues of this correlation matrix. c. Apply the LJ or GEA formula to estimate meff. d. Perform the Šidák correction using meff instead of the total number of features.

- Use Advanced Correlation-Aware Frameworks: For genome-wide association studies (GWAS), consider tools like SLIDE (Sliding-window approach for Locally Inter-correlated markers). SLIDE uses a multivariate normal framework and a sliding-window approach to account for all local correlations between markers, providing accurate corrected p-values without the need for computationally expensive permutations [14].

- Apply Extreme Tail Theory (ETT): For candidate gene methylation studies, the ETT method has been shown to appropriately correct for multiple testing in the presence of substantial correlation, as it explicitly calculates the Type I error rate given the observed correlation between test statistics [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Applying Šidák Correction in a Candidate Gene Methylation Study

This protocol is adapted from methods used to control the family-wise error rate in studies analyzing multiple correlated CpG sites within a candidate gene [33].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Dataset | The primary data input, typically from Illumina BeadChips (450K or EPIC), providing beta-values (β) for each CpG site. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Used for all data transformation, correlation calculation, eigenvalue computation, and statistical testing. |

| Correlation Matrix | A matrix (e.g., Pearson) quantifying the relationships between methylation levels (M-values) of all CpG site pairs within the gene. |

| Eigenvalue Calculator | A function (e.g., eigen in R, numpy.linalg.eig in Python) to derive eigenvalues from the correlation matrix, informing the effective number of tests. |

2. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Data Preparation and Transformation: Extract beta-values (β) for all CpG sites within your candidate gene or region of interest. Log-2 logit transform the beta-values to M-values using the formula: ( M = \log_2\left(\frac{\beta}{1-\beta}\right) ). M-values are more suitable for statistical tests that assume homoscedasticity [33].

- Calculate Correlation Structure: Compute the Pearson correlation matrix for all pairwise combinations of the M-values for the K CpG sites in your gene. This results in a K x K correlation matrix.

- Estimate Effective Number of Tests: Calculate the eigenvalues (ei) of the correlation matrix. Apply the Li and Ji (LJ) method to estimate the effective number of independent tests (effLJ): ( \text{eff}\text{LJ} = \sum{i=1}^{K} f(|e_i|) ), where ( f(x) = I(x \geq 1) + (x - [x]) ) and ( I ) is the indicator function [33].

- Perform Hypothesis Testing: Run your association test (e.g., linear regression of M-values on a phenotype) for each CpG site to obtain a pointwise p-value for each of the K sites.

- Apply Šidák Correction: Use the effective number of tests (effLJ) to compute the Šidák-corrected significance threshold: ( \alpha{\text{Šidák}} = 1 - (1 - \alpha)^{1/\text{eff}\text{LJ}} ), where α is your desired FWER (e.g., 0.05). Alternatively, directly adjust the p-values: ( p{\text{adj}} = 1 - (1 - p)^{\text{eff}_\text{LJ}} ) [33].

- Interpret Results: Declare sites with adjusted p-values (p_adj) less than α as statistically significant, controlling the FWER while accounting for the internal correlation of your data.

Protocol 2: Synthetic Data Simulation for Method Comparison

This protocol outlines the generation of synthetic data to evaluate and compare the performance of multiple testing corrections, as described in search results [30].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Data Simulation Software (R/MATLAB) | Used to generate synthetic high-dimensional datasets with controllable parameters. |

| Parameter Set | Predefined values for key variables: number of features, proportion of significant features, and degree of inter-feature correlation. |

| Performance Metrics | Criteria for evaluation, such as False Discovery Rate (FDR), Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), and statistical power (1 - False Negative Rate). |

2. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Define Simulation Parameters: Systematically vary the following parameters to create a range of experimental conditions:

- Total number of variables (features) to test (e.g., from hundreds to thousands).

- Proportion of variables that are truly statistically significant between groups.

- Degree of correlation between the variables (from independent to highly correlated) [30].

- Data Generation: For each combination of parameters, generate synthetic datasets. This typically involves sampling data from defined distributions (e.g., multivariate normal) for two or more groups, introducing controlled effect sizes for the "significant" variables, and imposing a correlation structure on the variables.

- Run Multiple Testing Methods: Apply the multiple testing procedures of interest (e.g., Bonferroni, Šidák, Benjamini-Hochberg, Leave-n-Out) to each generated dataset and record the outcomes (number of significant findings, true positives, false positives) [30].

- Evaluate Performance: Average the results over multiple simulation runs (e.g., 10 runs). Calculate performance metrics for each method across the different experimental conditions [30]:

- FWER: The proportion of simulated experiments where at least one false positive occurred.

- FDR: The average proportion of false positives among all discoveries.

- Power: The average proportion of truly significant variables that were correctly identified.

- Compare and Contrast: Analyze the results to determine under which data conditions (e.g., high correlation, low proportion of true signals) each multiple testing method performs best, informing future methodological choices for real datasets.

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

Diagram 1: Selection Workflow for Multiple Testing Corrections

Core Concept and Definition FAQs

What is the False Discovery Rate (FDR), and why has it become the modern standard in high-throughput genomics?

The False Discovery Rate (FDR) is a statistical metric defined as the expected proportion of false discoveries among all rejected hypotheses. In practical terms, if you run 100 tests and your FDR is controlled at 5%, you expect about 5 of your significant findings to be false positives [35] [11]. FDR control has become the standard in genomics because it offers a more balanced alternative to highly conservative methods like the Bonferroni correction, which controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER)—the probability of making at least one false discovery [12] [10]. In high-throughput experiments involving thousands of tests (e.g., gene expression, GWAS), FWER control is often too strict, leading to many missed true findings (low statistical power). FDR control allows researchers to identify more potential leads for follow-up studies while maintaining a quantifiable and acceptable level of error [35] [11] [36].

How does the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure control the FDR?

The BH procedure is a step-up method that controls the FDR by using an adaptive significance threshold. Instead of using a fixed p-value cutoff (e.g., 0.05), it orders all p-values from smallest to largest and compares each one to a sliding scale. This scale is determined by the formula (i/m) * Q, where i is the p-value's rank, m is the total number of tests, and Q is your desired FDR level (e.g., 0.05 for 5% FDR) [35] [37]. The procedure automatically becomes more stringent when there are fewer true positives and less stringent when there are many, effectively adapting to the underlying structure of your data [36].

When should I use the BH procedure over other multiple testing corrections?

The table below summarizes key considerations for choosing the BH procedure.

Table 1: Choosing the Right Multiple Testing Correction Method

| Method | Best Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| BH Procedure (FDR) | Exploratory high-throughput studies (e.g., genomics, screening) where some false positives are acceptable. | Greater statistical power than FWER methods while still providing meaningful error control [12] [36]. | Less stringent than FWER control; not suitable when any false positive is unacceptable. |

| Bonferroni (FWER) | Confirmatory studies or when testing a small number of pre-specified hypotheses where any false positive has severe consequences. | Strong control over the probability of any false positive. | Highly conservative, leading to a substantial loss of power in high-dimensional settings [12] [10]. |

| Benjamini-Yekutieli | Use when tests are negatively correlated or the dependency structure is unknown and potentially arbitrary. | Controls FDR under any dependency structure [35]. | Even more conservative than the standard BH procedure, resulting in lower power. |

Protocol and Implementation FAQs

What is the step-by-step protocol for applying the BH procedure?

Follow this detailed workflow to manually implement the BH procedure. Most statistical software packages can automate these steps.

Table 2: Step-by-Step BH Procedure Protocol

| Step | Action | Example from a 6-Gene Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conduct all m hypothesis tests and obtain their raw p-values. |

P-values: 0.01, 0.001, 0.05, 0.20, 0.15, 0.15 (m=6) [38]. |

| 2 | Order the p-values from smallest to largest and assign ranks (i). |

Ordered p-values: 0.001 (rank 1), 0.01 (rank 2), 0.05 (rank 3), 0.15 (rank 4), 0.15 (rank 5), 0.20 (rank 6). |

| 3 | For each ordered p-value, calculate its BH critical value: (i / m) * Q. Let's use Q=0.05. |

Critical values: (1/6)0.05≈0.0083, (2/6)0.05≈0.0167, (3/6)0.05=0.025, (4/6)0.05≈0.033, (5/6)0.05≈0.0417, (6/6)0.05=0.05. |

| 4 | Find the largest p-value where p-value ≤ critical value. Reject the null hypothesis for this test and all tests with smaller p-values. |

Compare: 0.001<0.0083, 0.01<0.0167, 0.05>0.025. The largest p-value meeting the criterion is rank 2 (0.01). |

| 5 | Declare the top 2 tests (with p-values 0.001 and 0.01) as statistically significant discoveries. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision flow of the BH procedure.

How do I implement the BH procedure in R or Python?

Implementation is straightforward using built-in functions.

In R, use the

p.adjust()function.The

adjusted_pvector will contain the BH-adjusted p-values (e.g., 0.03, 0.006, 0.10, ...). Any value less than your FDR threshold (e.g., 0.05) is significant [38].In Python, use

statsmodels.stats.multitest.fdrcorrectionorscipy.stats.false_discovery_control(version 1.11+).The result is an array of adjusted p-values [38].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

What should I do if my tests are not independent? The BH procedure assumes independence or positive dependency.

This is a common concern in genomics, where tests on nearby genomic loci are correlated due to linkage disequilibrium, or genes in the same pathway are co-expressed [10]. While the BH procedure is robust to certain types of positive dependency, it may not control the FDR accurately under arbitrary or negative dependency structures [35]. If you suspect your data violate the independence assumption, you have two main options:

- Use the Benjamini-Yekutieli (BY) Procedure: This is a more conservative variant of BH that guarantees FDR control under any dependency structure. The calculation is similar to BH, but the critical value is divided by a harmonic number:

(i / (m * c(m))) * Q, wherec(m) = sum(1/i)for i from 1 to m [35]. In R, this isp.adjust(p_values, method = "BY"). - Use Permutation-Based Methods: These methods empirically estimate the null distribution of your test statistics by randomly shuffling your phenotype labels many times. This approach naturally accounts for the underlying correlation structure of your data. While computationally intensive, it is a highly respected approach for complex genomic data [34].

How do I interpret results when working with genomic regions versus individual windows/variants?

A significant challenge in analyses like ChIP-seq is the difference between a window-based FDR and a region-based FDR. You might control the FDR at 10% across all windows in the genome, but if you then merge adjacent significant windows into regions, your actual FDR across regions could be much higher [39].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Scenarios and Errors

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No significant results after BH correction. | Low statistical power; effect sizes are too small relative to sample size and noise. | Increase sample size if possible. Consider using modern FDR methods that incorporate an informative covariate (e.g., IHW, AdaPT) to boost power [12] [40]. |

| Difficulty interpreting the biological unit of discovery (window vs. region). | The unit of testing (window) does not match the unit of biological interpretation (region) [39]. | Group windows into biologically relevant regions (e.g., genes, peaks) first, then compute a combined p-value per region using Simes' method, and finally apply the BH procedure to these regional p-values [39]. |

| Results are too conservative even with BH. | The tests may be highly correlated, violating the positive dependency assumption. | Validate FDR control using the more conservative BY procedure or permutation tests. If results hold, you can have greater confidence in your findings. |

How can I increase power while still controlling the FDR?

If the standard BH procedure yields too few discoveries, consider "modern" FDR methods that use an informative covariate. These methods prioritize hypotheses that are a priori more likely to be true discoveries, increasing overall power without sacrificing FDR control [12] [40].

- Examples of Informative Covariates:

- In an eQTL study: The distance between a genetic variant and a gene's transcription start site. Local associations are more likely to be real [40].

- In an RNA-seq study: The average read count or expression level of a gene. Genes with higher counts often have better power to detect differential expression [40].

- In a GWAS: Prior information from a linkage study or functional annotation of the variant.

Methods like Independent Hypothesis Weighting (IHW) and AdaPT can use these covariates to improve power. Crucially, if the covariate is completely uninformative, these methods default to performance similar to the classic BH procedure, so there is little to lose in trying them [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for FDR-Controlled Genomic Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Open-source environment for statistical computing. The primary platform for implementing multiple testing corrections. | Running p.adjust() for the BH procedure or using the IHW package for covariate-weighted FDR control. |

| Python (SciPy/Statsmodels) | General-purpose programming language with extensive statistical and scientific computing libraries. | Using scipy.stats.false_discovery_control for FDR adjustment in a Python-based bioinformatics pipeline. |

| q-value / STAN | Software and packages for calculating q-values, which are FDR analogues of p-values. | Using the qvalue R package to estimate the proportion of true null hypotheses (π₀) and compute q-values. |

| GenomicRanges (R/Bioconductor) | A Bioconductor package for representing and manipulating genomic intervals. | Defining and managing genomic windows and regions before and after performing multiple testing correction [39]. |

| Permutation Framework | A resampling technique that creates an empirical null distribution by shuffing labels. | Assessing the true FDR in datasets with complex correlation structures where theoretical assumptions may be violated [34]. |

Q1: In high-throughput genomics, why are standard multiple testing corrections like the Bonferroni method often problematic?

Standard corrections like Bonferroni control the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), which is the probability of making at least one false positive discovery. While this is strict, it is often too conservative when testing thousands of genes simultaneously. This conservatism leads to greatly reduced power, meaning many true positive findings (e.g., genuinely differentially expressed genes) are missed. In genomics, where we often expect many true signals, this is a significant limitation [12] [11].

Q2: What is the False Discovery Rate (FDR), and how does it offer an improvement?

The False Discovery Rate (FDR) is the expected proportion of false positives among all discoveries declared significant. An FDR of 5% means that among all genes called differentially expressed, approximately 5% are expected to be false positives. Controlling the FDR, instead of the FWER, provides a more balanced approach for large-scale experiments, allowing researchers to tolerate a few false positives in order to dramatically increase the number of true positives identified [12] [11].

Q3: What is the fundamental difference between the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure, Benjamini-Yekutieli (BY) procedure, and Storey's q-value?

The core difference lies in their statistical assumptions and how they estimate the proportion of true null hypotheses.

- BH procedure: The first and most widely used method for FDR control. It is powerful but relies on the assumption that the test statistics are independent or positively dependent [41] [42].

- BY procedure: A modification of the BH procedure that guarantees FDR control under any dependency structure between tests. This makes it more robust but also more conservative than BH [41] [42].

- Storey's q-value: This is an estimation-based approach that often provides more power. It directly estimates the positive FDR (pFDR) and the proportion of true null hypotheses (π₀) from the data, making it particularly adaptive to the specific dataset [41] [12] [11].

The following workflow helps in selecting the appropriate method based on your data's characteristics:

Method Selection and Troubleshooting FAQ

Q4: I am analyzing RNA-seq data from a single-cell experiment where gene expression is highly correlated. Which FDR method should I use and why?

For data with complex and unknown dependency structures, such as correlated gene expression in single-cell RNA-seq, the Benjamini-Yekutieli (BY) procedure is the safest choice. It provides guaranteed FDR control regardless of the dependency structure between your tests. Be aware that this robustness comes at the cost of reduced power compared to BH or Storey's method. If you are willing to accept a slight risk of FDR inflation for greater power, the BH procedure is often applied in practice, though its theoretical assumptions may be violated [41] [42].

Q5: When using Storey's q-value, my results seem too liberal, reporting many false positives in validation. What could be the issue?

Storey's q-value method relies on accurately estimating the proportion of true null hypotheses (π₀). This estimation can be biased in low-dimensional settings where the number of hypotheses tested is small (e.g., only a few dozen or hundreds). The method requires a sizeable number of tests (typically thousands) for a reliable estimate. If your replication study or targeted experiment tests only a small number of hypotheses, Storey's method can become anti-conservative. In such low-dimensional situations, FWER methods (like Bonferroni) or the more conservative BY procedure are preferred to maintain high specificity [41].

Q6: How do I know if my dataset is suitable for Storey's q-value instead of the standard BH procedure?

Storey's q-value is particularly advantageous in high-dimensional settings (e.g., genome-wide studies) where the proportion of true alternatives is non-negligible. It shines when you have a large number of tests and expect a decent number of true hits, as its adaptive nature provides a power boost. The following table summarizes the key decision factors:

| Feature | Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) | Storey's q-value |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Step-up procedure controlling FDR | Estimation of FDR using empirical Bayes |

| Key Assumption | Independent or Positive Dependent tests [41] [42] | Independent tests for provable control [41] |

| Power | High | Higher than BH when π₀ < 1 [12] |

| Best Use Case | Standard high-throughput data with positive dependency | High-dimensional data with many tests and non-null hypotheses [41] |

| Low-Dimensional Warning | Less powerful but controls FDR under its assumptions | Can be biased, leading to inflated FDR [41] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementing the Benjamini-Yekutieli Procedure in R

The BY procedure is a direct modification of the BH method, adding a correction factor to account for dependencies.

1. Compute p-values: First, perform all your statistical tests (e.g., t-tests for differential expression) to obtain a vector of p_values.

2. Define the correction factor: Calculate the harmonic sum: ( c(m) = \sum{i=1}^{m} 1/i ), where ( m ) is the total number of tests.

3. Apply the BY procedure:

* Order the p-values from smallest to largest: ( p{(1)} \leq p{(2)} \leq \ldots \leq p{(m)} ).

* Find the largest ( k ) such that ( p{(k)} \leq \frac{k}{m \cdot c(m)} \alpha ).

* Reject all null hypotheses for ( p{(1)}, \ldots, p_{(k)} ).

R Code Snippet:

Protocol 2: Implementing Storey's q-value in R

Storey's method involves estimating the proportion of null hypotheses and then calculating q-values for each hypothesis.

1. Compute p-values: Obtain a vector of p_values from your tests.

2. Estimate π₀ (proportion of nulls): This is done by choosing a tuning parameter lambda (often λ=0.5) and calculating:

( \hat{\pi}0(\lambda) = \frac{#{pi > \lambda}}{m(1 - \lambda)} )

3. Calculate q-values:

* For each ordered p-value, ( p{(i)} ), compute:

( q(p{(i)}) = \min{t \geq p{(i)}} \frac{ \hat{\pi}0 \cdot m \cdot t }{ #{pj \leq t} } )

R Code Snippet (using the qvalue package):

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table lists key computational tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for implementing advanced FDR controls in genomic research.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Software | The primary platform for statistical computing; hosts the necessary packages for FDR analysis [15]. |

qvalue Package |

Software/R Library | Directly implements Storey's q-value method, providing robust estimation of q-values and π₀ [12]. |

| Benjamini-Yekutieli (BY) Correction | Software/Algorithm | Available in base R via p.adjust(p_values, method="BY"); the go-to solution for data with arbitrary dependencies [41] [42]. |

| Negative Control Probes | Experimental Reagent | Used in spatial transcriptomics and other imaging technologies to empirically estimate the background false discovery rate, allowing for direct assessment of assay specificity [43]. |

| Informed Covariate | Data/Conceptual | A variable independent of the p-value under the null but informative of power or prior probability of being non-null (e.g., gene expression level). Can be used with modern FDR methods (IHW, AdaPT) to further increase power beyond classic methods [12]. |

FAQs on Dependence and Multiple Testing Corrections

1. Why is accounting for dependence between tests crucial in genomics? In high-throughput genomics, tests on genetic markers are not independent due to Linkage Disequilibrium (LD), the non-random association of alleles at different loci [44]. LD induces correlation between test statistics for nearby genes or SNPs [44]. If standard multiple testing corrections like Bonferroni assume independence, they can be overly conservative, potentially missing true associations. Methods that account for this dependence provide more accurate error control and improve power [44] [45].

2. What is the difference between FWER and FDR, and when should I use each? The Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) is the probability of making at least one Type I error (false positive) across all tests. Controlling it is stringent and best suited when testing only a few hypotheses or when the cost of a single false positive is very high [46]. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) is the expected proportion of false discoveries among all rejected hypotheses. It is less conservative and is recommended when testing hundreds or thousands of hypotheses, as it offers greater power, which is common in genomics [46].

3. My Q-Q plot shows severe genomic inflation. What does this indicate? A severely inflated Q-Q plot, where observed p-values deviate from the null expectation across the entire distribution, often indicates a systematic issue. While it can signal widespread polygenicity, it is frequently a sign of unaccounted-for dependence or population structure within your data. This suggests that the null distribution of your test statistics is incorrect, and methods that explicitly model this dependence (like the agglomerative algorithm or permutation tests) should be employed [44].

4. How do resampling techniques help account for dependence? Resampling techniques like permutation tests do not rely on asymptotic theory or assumptions of independence between tests. By randomly shuffling labels (e.g., case/control) and recalculating test statistics many times, they empirically generate a null distribution that preserves the correlation structure of the underlying data. This allows for valid significance testing even when tests are dependent [47].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: A known causal locus is not reaching significance after multiple testing correction.

- Potential Cause: Overly conservative correction methods like Bonferroni are being applied to highly correlated tests, drastically reducing statistical power [46] [24].

- Solution:

- Switch to an FDR-based procedure like the Benjamini-Hochberg method, which is more powerful in a high-dimensional setting [46].

- Apply a resampling technique like a permutation test to generate empirical p-values that account for the LD structure [47].

- Use a method that agglomerates correlated features. For gene-based tests, group genes with highly correlated test statistics into LD loci and test the locus as a whole [44].

Issue: Inconsistent gene-based test results between different studies of the same phenotype.

- Potential Cause: The studies may be using different SNP-to-gene assignment rules (e.g., positional only vs. positional plus cis-eQTL), different LD reference panels, or different schemes for handling correlated gene-based statistics [44].

- Solution:

- Standardize the SNP-to-gene assignment protocol. Consider incorporating functional genomics data, such as eQTLs, to assign SNPs to genes more accurately [44].

- Ensure both studies use a similar LD reference panel from a genetically matched population.

- Implement an agglomerative algorithm that formally accounts for correlation between gene-based test statistics to ensure the results are robust and interpretable [44].

Issue: How to validate findings from a high-throughput experiment with a small sample size?

- Potential Cause: Small sample sizes lead to low power and unstable estimates.

- Solution:

- Use the Bootstrap: Resample your data with replacement to generate thousands of bootstrap samples. Calculate your statistic of interest (e.g., odds ratio, effect size) on each sample. This provides empirical confidence intervals for your estimates, assessing their stability [47] [48].

- Apply Cross-Validation: If building a predictive model, use cross-validation to assess its performance. Randomly divide the data into k folds, train the model on k-1 folds, and validate it on the left-out fold. Repeating this process provides a robust estimate of how the model will generalize to independent data [47].

Methodologies for Key Experiments

1. Agglomerative LD Loci Testing for Gene-Based Analysis This methodology groups correlated genes into loci to account for dependence from LD that crosses gene boundaries [44].

- Workflow Overview:

- Detailed Protocol:

- SNP Assignment and Initial Test Statistics: Assign SNPs to genes based on their genomic position (and optionally, cis-eQTL data). Calculate an initial gene-based test statistic (e.g., a quadratic statistic like in VEGAS or MAGMA) for each gene [44].

- Compute Pairwise Correlation: For all pairs of genes within a specified window (e.g., 2 megabases), compute the LD-induced correlation between their test statistics using a known LD reference matrix (e.g., from the 1000 Genomes Project) [44]. The formula for the correlation between two gene sets A and B is derived from the covariance:

cov(t_A, t_B) = Σ_{i in A} Σ_{j in B} cov(z_i, z_j)^2 + 2 * Σ_{i,k in A} Σ_{j in B} cov(z_i, z_j) * cov(z_k, z_j)[44]. - Agglomerate Correlated Genes: Identify the pair of genes (or gene loci) with the highest correlation above a pre-specified threshold (e.g., r > 0.8). Merge them into a single locus.