Optimizing ChIP-seq Protocols for Histone Marks: A Comprehensive Guide for Epigenetic Research

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the cornerstone technique for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications, yet protocol optimization remains critical for data quality and biological relevance.

Optimizing ChIP-seq Protocols for Histone Marks: A Comprehensive Guide for Epigenetic Research

Abstract

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the cornerstone technique for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications, yet protocol optimization remains critical for data quality and biological relevance. This article provides a systematic comparison of ChIP-seq methodologies tailored to different histone marks, addressing foundational principles, practical applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks. We explore mark-specific considerations for abundant promoter marks like H3K4me3 versus broad repressive domains like H3K27me3, detail low-input and tissue-optimized protocols, and present quality control metrics essential for reproducible research. Targeting experimental biologists and drug discovery scientists, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enable robust epigenetic profiling across diverse biological systems from cell cultures to clinical specimens.

Understanding Histone Mark Diversity and Its Impact on ChIP-seq Experimental Design

In the field of epigenomics, histone modifications do not exist as a monolithic entity but rather display distinct spatial patterns across the genome that reflect their diverse functional roles. These patterns are broadly categorized into point source (or narrow) and broad domain modifications, each with unique characteristics, regulatory mechanisms, and biological implications. Understanding this dichotomy is crucial for researchers investigating gene regulation, cell identity, and disease mechanisms, particularly as it influences experimental design and data analysis choices in ChIP-seq workflows.

The fundamental difference between these categories lies in their genomic distribution. Point source marks, such as H3K4me3 at most active promoters, typically manifest as sharp, well-defined peaks spanning less than 1 kilobase, often flanking transcription start sites (TSSs) [1]. In contrast, broad domain marks, including H3K27me3 (associated with Polycomb-mediated repression) and a specialized subset of H3K4me3, can extend over kilobase- to megabase-scale regions, forming expansive epigenetic domains that cover entire gene bodies and beyond [2] [1]. This review systematically compares these histone mark categories, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate analytical approaches and interpreting their biological significance in the context of gene regulation and cell identity.

Characterizing Histone Mark Categories

Point Source Histone Marks

Point source histone modifications are characterized by their highly localized distribution at specific genomic landmarks. These narrow peaks typically mark regulatory elements with precise functions and exhibit strong correlation with defined chromatin states.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Point Source Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Typical Genomic Location | Associated Function | Peak Width | Chromatin State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcription Start Sites (TSS) | Promoter of active genes | < 1-2 kb [1] | Active |

| H3K9ac | Transcription Start Sites (TSS) | Promoter of active genes | Narrow [3] | Active |

| H3K27ac | Active enhancers and promoters | Enhancer/Promoter activity | Narrow [4] | Active |

| H3K4me1 | Enhancers | Enhancer activity | Narrow [4] | Primed/Active |

The functional role of point source marks is exemplified by H3K4me3, which integrates various signaling pathways involved in transcription initiation, elongation, and RNA splicing [1]. At most active genes, H3K4me3-marked nucleosomes form sharp, narrow peaks flanking TSSs, with peak intensity often correlating with transcriptional activity [1]. The highly localized nature of these marks makes them particularly amenable to analysis with standard peak-calling algorithms.

Broad Domain Histone Marks

Broad domain histone modifications cover extensive genomic regions and are associated with more complex regulatory functions, particularly in defining chromatin states and cell identity.

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Broad Domain Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Typical Genomic Location | Associated Function | Domain Width | Chromatin State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb target genes | Developmental gene repression | Up to megabases [5] | Repressed (Facultative Heterochromatin) |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Transcriptional repression | Broad (~megabases) [2] | Repressed (Constitutive Heterochromatin) |

| H3K36me3 | Gene bodies of active genes | Transcriptional elongation | Broad [3] | Active |

| Broad H3K4me3 | Cell identity genes | Transcriptional consistency | > 4 kb [1] | Active |

A particularly significant broad domain is the broad H3K4me3 domain, which extends beyond the typical narrow promoter peak to cover extensive regions downstream into gene bodies [1]. These broad epigenetic domains mark genes essential for cell identity and function, exhibiting a lower signal intensity than sharp H3K4me3 peaks but covering significantly larger genomic regions [2] [6]. Unlike typical point source H3K4me3, these broad domains do not simply correlate with higher expression levels but rather with enhanced transcriptional consistency - reduced cell-to-cell variation in gene expression - at key cell identity genes [2] [6].

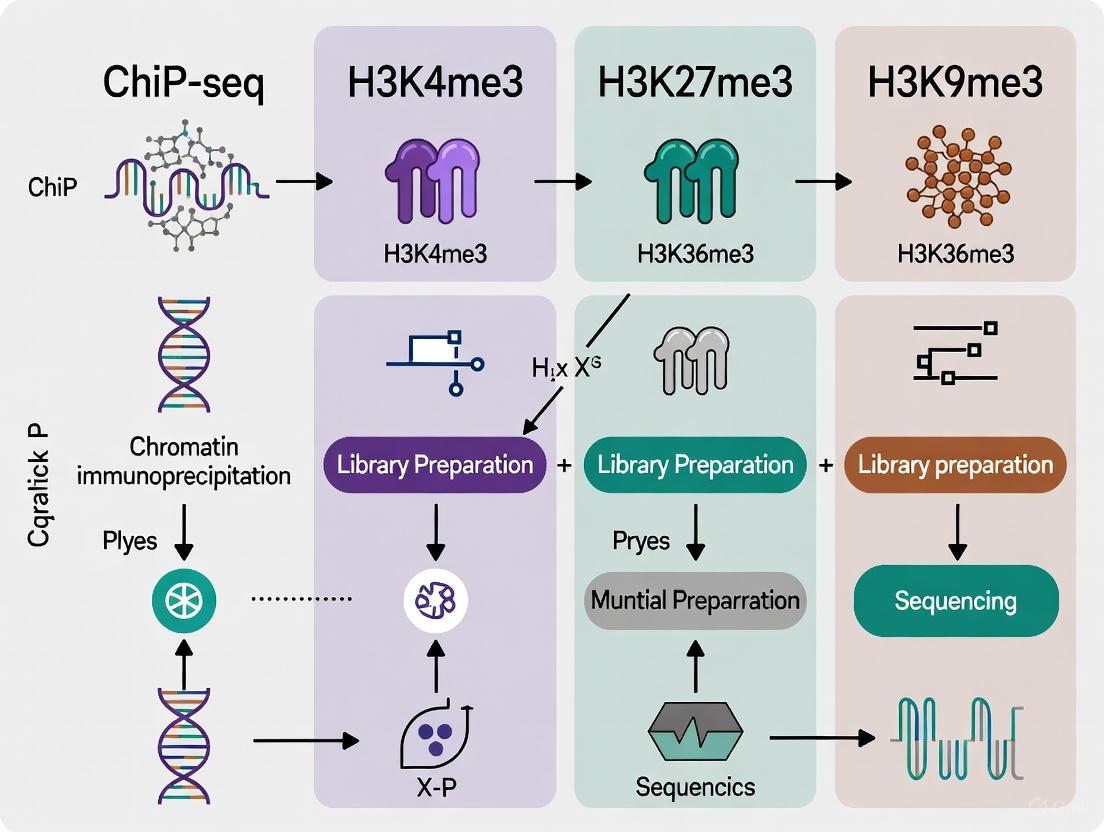

Figure 1: Classification and functional outcomes of major histone H3 modifications categorized by their genomic distribution patterns.

Experimental and Analytical Considerations

Peak Calling Performance Across Histone Mark Types

The categorical differences between point source and broad histone modifications necessitate specialized analytical approaches. Comparative studies of peak calling algorithms have revealed significant performance variations depending on the mark type being analyzed.

Table 3: Peak Caller Performance for Different Histone Mark Types

| Peak Calling Program | Performance on Point Source Marks | Performance on Broad Marks | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACS2 (with broad option) | Good for narrow peaks [3] | Improved performance with broad settings [3] | General purpose, flexible |

| CisGenome | Good performance [3] | Variable performance | Narrow marks only |

| PeakSeq | Good performance [3] | Variable performance | Narrow marks only |

| SISSRs | Lower performance on some marks [3] | Not recommended | Limited applications |

When analyzing point source histone modifications such as H3K4me3, H3K9ac, and H3K27ac, most peak callers show consistent performance with minimal differences between algorithms [3]. However, for broad marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, the choice of algorithm significantly impacts results, with specialized approaches or broad peak settings required for accurate domain identification [3]. This distinction is critical for researchers designing ChIP-seq experiments, as the analytical pipeline must be tailored to the specific histone mark being studied.

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping Histone Modifications

Traditional chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the cornerstone of histone modification mapping, but recent technological advances have addressed several limitations of conventional approaches.

Micro-C-ChIP represents a significant innovation that combines Micro-C with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [5]. This approach profiles mark-specific 3D genome architecture while maintaining a high ratio of informative reads (42% compared to 37% in genome-wide Micro-C), making it particularly valuable for studying the spatial organization of both point source and broad domain marks [5].

CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) and CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation) technologies represent advances over traditional ChIP-seq, enabling detection of protein-DNA interactions at approximately 20 bp resolution with lower background noise and reduced input requirements [4]. These techniques avoid the epitope masking and false positive binding sites generated by crosslinking in standard ChIP-seq, making them particularly valuable for mapping broad histone domains where precise boundary definition is challenging [4].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow evolution and their optimal applications for different histone mark types.

Biological Significance and Functional Implications

Distinct Roles in Gene Regulation and Cell Identity

The categorical distinction between point source and broad histone marks reflects their fundamentally different biological roles in genome regulation and cellular function.

Point source marks operate as precision regulatory tools that fine-tune gene expression at specific genomic loci. The narrow H3K4me3 peaks at most active promoters facilitate transcription initiation through recruitment of the basal transcription machinery, including TFIID via its TAF3 subunit that recognizes H3K4me3 [1]. This mechanism enables rapid, precise responses to cellular signals at individual genes.

In contrast, broad domain marks implement higher-order chromosomal programming. Broad H3K4me3 domains, which cover approximately 5% of genes in any given cell type, specifically mark genes essential for cellular identity and function [2] [6]. In neural progenitor cells, these broad domains identify key regulators of neural development, while in embryonic stem cells, they mark pluripotency factors [2]. Rather than simply increasing transcription levels, broad H3K4me3 domains ensure transcriptional consistency - reduced cell-to-cell variation in expression - at these critical cell identity genes [6]. This precision maintenance function is distinct from the on/off regulatory role of narrow H3K4me3 peaks.

Similarly, broad H3K27me3 domains establish stable, heritable repression of developmental gene regulators through Polycomb complex activities, maintaining cellular identity by repressing alternative lineage genes [5]. These broad repressive domains can span large genomic regions, often encompassing multiple genes in coordinated regulatory units.

Dynamics in Development and Disease

The different behaviors of point source and broad domain histone marks during cellular differentiation and transformation further highlight their distinct biological roles.

Point source marks typically display dynamic redistribution during differentiation, changing rapidly in response to altered transcriptional programs. These changes reflect the immediate regulatory needs of cells as they transition between states.

Broad H3K4me3 domains, however, exhibit programmed stability during lineage commitment. As cells differentiate, specific genes gain or lose broad H3K4me3 domains in a coordinated manner: genes acquiring broad domains during differentiation enrich for terminally differentiated cell functions, while genes losing broad domains enrich for progenitor cell functions [2]. This programmed reorganization of broad domains underscores their role in establishing and maintaining cell identity.

In disease contexts, particularly cancer, the distinction between point source and broad domains has clinical implications. Broad epigenetic domains mark essential genes with potential as biomarkers for patient stratification [1]. Reducing expression of genes marked by broad epigenetic domains may increase metastatic potential in cancer cells, suggesting these domains maintain transcriptional programs that suppress malignant progression [1]. The specialized machinery governing broad H3K4me3 domains, including KMT2F/G (SETD1A/SETD1B) methyltransferase complexes with their CXXC1 subunit that targets CpG islands, represents potential therapeutic targets when dysregulated in disease [1].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Mark Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of point source marks | Critical for ChIP-seq; check specificity due to cross-reactivity issues [1] |

| H3K27me3 Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of broad repressive domains | Essential for mapping Polycomb target regions [5] |

| KMT2F/G (SETD1A/B) Inhibitors | Perturbation of H3K4me3 deposition | Specifically affect broad H3K4me3 domains [1] |

| CXXC1 Affinity Reagents | Disruption of broad H3K4me3 targeting | Interfere with recruitment to CpG islands [1] |

| Micro-C-ChIP Reagents | Mapping 3D architecture of specific marks | Superior for capturing genuine 3D interactions [5] |

| MACS2 Software | Peak calling for both narrow and broad marks | Use broad peak setting for domain analysis [3] |

The categorical distinction between point source and broad domain histone modifications represents a fundamental organizational principle of epigenetic regulation. Point source marks, characterized by narrow peaks, enable precise regulatory control at individual promoters and enhancers, while broad domains implement higher-order chromosomal programming that defines cell identity and ensures transcriptional fidelity. This dichotomy extends to experimental methodologies, requiring researchers to select specialized protocols and analytical approaches tailored to their specific mark of interest. As epigenetic therapies advance, understanding these distinct categories and their biological significance will be crucial for developing targeted interventions in cancer and other diseases involving epigenetic dysregulation.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of epigenetic regulation and gene expression. As histone modification research becomes increasingly critical for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutics, selecting appropriate experimental protocols presents significant challenges. Technical variations across methods directly impact data quality, reproducibility, and biological interpretation. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of established and emerging ChIP-seq protocols, focusing on three critical technical considerations: antibody validation, cell number requirements, and control experiments. By objectively evaluating these parameters across methodologies, we empower researchers to select optimal approaches for their specific histone mark research applications.

Methodologies for Histone Mark Profiling: A Technical Comparison

The evolving landscape of epigenomic profiling now offers researchers multiple methodological pathways for investigating histone modifications. Each technique carries distinct advantages, limitations, and technical requirements that must be carefully considered during experimental design.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the established standard for mapping DNA-protein interactions genome-wide. In this protocol, chromatin is cross-linked, fragmented (typically via sonication), and immunoprecipitated using an antibody specific to the histone mark of interest. The co-precipitated DNA is then purified and sequenced, revealing enriched genomic regions. The ENCODE consortium has extensively optimized and provided guidelines for ChIP-seq, making it a well-characterized reference method with abundant publicly available data for comparison [7]. However, traditional ChIP-seq requires substantial starting material—typically 1-10 million cells per immunoprecipitation—creating limitations when working with rare cell populations or primary tissue samples [8]. Additionally, the procedure involves multiple steps that can introduce biases, including cross-linking artifacts, uneven chromatin fragmentation, and low signal-to-noise ratios that demand high sequencing coverage [7].

Cleavage Under Targets & Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) has emerged as a promising alternative that addresses several ChIP-seq limitations. This enzyme-tethering approach utilizes permeabilized nuclei, allowing antibodies to bind chromatin-associated factors before recruiting a Protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein (pA-Tn5). Upon activation, pA-Tn5 cleaves intact DNA and inserts adapters exclusively in antibody-bound regions, a process known as tagmentation [7]. CUT&Tag offers dramatic improvements in signal-to-noise ratio, operates at approximately 200-fold reduced cellular input (down to ~5,000 cells), and requires 10-fold reduced sequencing depth compared to ChIP-seq while maintaining compatibility with standard analysis pipelines [7]. Benchmarking studies indicate CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of known ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks, primarily capturing the strongest peaks while maintaining similar functional and biological enrichments [7].

Recent methodological innovations continue to expand the epigenomic toolbox. Micro-C-ChIP combines Micro-C with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications, offering insights into chromatin architecture beyond simple mark localization [5]. PerCell chromatin sequencing integrates cell-based chromatin spike-ins from orthologous species with a flexible bioinformatic pipeline, enabling highly quantitative comparisons of protein-genome binding across experimental conditions and cellular contexts [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Histone Profiling Methodologies

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Cell Input | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | Cross-linking, sonication, immunoprecipitation | 1-10 million cells | Established standard, extensive benchmarks & guidelines (ENCODE) | High cell input, cross-linking artifacts, lower signal-to-noise |

| CUT&Tag | Antibody-directed tagmentation in permeabilized nuclei | ~5,000 cells | Low cell input, high signal-to-noise, cost-effective sequencing | Recovers ~54% of ENCODE peaks, newer method with fewer reference datasets |

| Micro-C-ChIP | Combines Micro-C with ChIP for 3D architecture | Research-scale | Nucleosome resolution for specific histone modifications, reveals 3D interactions | Specialized application, complex data analysis |

| PerCell | Cross-species chromatin spike-in with bioinformatic normalization | Research-scale | Enables quantitative cross-condition comparisons | Requires specialized spike-in materials |

Antibody Validation: The Foundation of Reliable Data

Antibody specificity remains the cornerstone of all chromatin profiling experiments, as non-specific antibodies can generate false-positive signals and compromise data interpretation. The ongoing reproducibility crisis in epigenetics underscores the critical importance of rigorous antibody validation [10] [11].

Validation Strategies and Pitfalls

Effective antibody validation requires a multi-faceted approach. Recombinant protein validation via Western blot provides initial specificity assessment but can be misleading if not interpreted cautiously. Dr. Joanna Porankiewicz-Asplund cautions that "researchers might expect to see a very intense band on a Western blot, not realizing that it is impossible to achieve this in an endogenous extract, for a target of low abundance" [11]. The recommended practice involves consulting protein abundance databases like PaxDb to establish realistic expectations before experimental implementation [11].

For histone modification studies, peptide competition assays offer superior validation by demonstrating that binding signals are specifically abolished by the target peptide but not by non-specific alternatives. Additional validation strategies include correlation with orthogonal methods (e.g., mass spectrometry) and genetic knockout controls where feasible. As noted in recent antibody characterization insights, "many antibodies used in research do not recognize their targets or bind to undesired molecules, compromising study findings, wasting resources, producing irreproducible data, and delaying drug development" [10].

Platform-Specific Antibody Considerations

Antibody performance varies significantly across platforms, necessitating method-specific validation. CUT&Tag benchmarking reveals that even ChIP-seq-grade antibodies require optimization for tagmentation-based approaches. Systematic evaluation of H3K27ac antibodies for CUT&Tag tested multiple ChIP-grade antibody sources across various dilutions (1:50, 1:100, 1:200), identifying significant performance variations despite comparable ChIP-seq efficacy [7]. Similar optimization is crucial for H3K27me3 profiling, where Cell Signaling Technology-9733 antibody at 1:100 dilution has demonstrated reliable performance in CUT&Tag applications [7].

For complex antibody formats targeting specific histone modifications, advanced characterization techniques are essential. As noted in recent technical analyses, "high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) offers unmatched precision in identifying post-translational modifications and estimating molecular weights" to ensure antibody specificity [10]. Similarly, "hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) provides insights into the stability and conformational dynamics of antibody-antigen complexes" [10].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Antibody Validation Workflow. This workflow outlines the critical steps for validating antibodies for histone mark research, from initial specificity checks to method-specific optimization.

Cell Number Requirements: Balancing Sensitivity and Practicality

Cell input requirements represent a critical practical consideration in experimental design, particularly for clinical samples or rare cell populations where material is limited. Significant methodological advances have dramatically reduced the cellular material needed for robust histone mark profiling.

Method-Specific Input Requirements

Traditional ChIP-seq protocols typically require 1-10 million cells per immunoprecipitation, creating a substantial barrier for studies involving primary tissues, rare cell populations, or developmental models [8] [7]. Protocol optimizations have enabled low-cell-number ChIP-seq with inputs as low as 100,000 cells, representing a 200-fold reduction compared to early implementations [8]. However, pushing toward this lower limit introduces technical challenges, including "increased levels of unmapped and duplicate reads [that] reduce the number of unique reads generated, and can drive up sequencing costs and affect sensitivity" [8].

CUT&Tag achieves a remarkable advancement in sensitivity, requiring only ~5,000 cells for robust histone mark profiling—approximately 200-fold fewer cells than standard ChIP-seq protocols [7]. This dramatically reduced input requirement makes CUT&Tag particularly valuable for stem cell research, clinical biopsies, and single-cell applications where material is severely limited. The enhanced sensitivity stems from CUT&Tag's fundamentally different biochemistry: "The increased signal-to-noise ratio of CUT&Tag for histone marks is attributed to the direct antibody tethering of pA-Tn5 and its integration of adapters in situ while it stays bound to the antibody target of interest during incubation" [7].

Technical Implications of Low-Input Protocols

Reducing cell input introduces specific technical considerations that impact experimental outcomes. As cell numbers decrease, PCR duplicate rates increase substantially—CUT&Tag datasets show duplication rates ranging from 55.49% to 98.45% (mean: 82.25%) [7]. These elevated duplication rates can necessitate adjustments to PCR cycling parameters during library preparation and increase sequencing depth requirements to obtain sufficient unique reads.

Low-input methods also face molecular complexity limitations. With fewer starting cells, the diversity of unique chromatin fragments decreases, potentially limiting detection of lower-abundance histone modifications or weaker binding events. Researchers must therefore carefully balance input requirements with desired genomic coverage, particularly when studying subtle epigenetic changes or heterogeneous cell populations.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison: CUT&Tag vs. ChIP-seq

| Performance Metric | CUT&Tag | Traditional ChIP-seq | Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cell Input | ~5,000 cells | 1-10 million cells | CUT&Tag enables rare sample studies |

| Sequencing Depth | 10-fold lower requirement | Higher depth required | CUT&Tag reduces per-sample sequencing costs |

| ENCODE Peak Recovery | ~54% for H3K27ac/H3K27me3 | 100% (reference) | CUT&Tag captures strongest peaks |

| Duplicate Read Rate | 55-98% (mean: 82%) | Typically lower | Higher duplication may impact complexity |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Superior | Standard | CUT&Tag provides cleaner signal |

Control Experiments and Normalization Strategies

Appropriate experimental controls and normalization methods are essential for distinguishing technical artifacts from biological signals in histone mark profiling. The choice of controls and normalization strategy depends heavily on the specific research question and methodology employed.

Method-Specific Control Requirements

Effective ChIP-seq experiments incorporate multiple control elements to ensure data quality. Input DNA (non-immunoprecipitated genomic DNA) controls for technical biases introduced during chromatin fragmentation, sequencing, and mapping. IgG controls (immunoprecipitation with non-specific antibody) identify regions of non-specific antibody binding and background signal. For perturbation studies, genetic knockout controls provide the most rigorous validation of antibody specificity, though these are not always experimentally feasible.

CUT&Tag protocols benefit from similar control strategies but require additional considerations due to their unique biochemistry. The use of negative control primers targeting genomic regions devoid of the histone mark of interest helps establish background signal levels during initial optimization [7]. Additionally, positive control primers designed against strong ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks enable rapid protocol validation via qPCR before committing resources to full sequencing [7]. For H3K27ac CUT&Tag, researchers have tested whether histone deacetylase inhibitors (TSA, sodium butyrate) improve data quality, though results indicate "addition of TSA did not consistently increase total peak detection" or improve ENCODE capture rates [7].

Normalization Approaches for Differential Binding

Between-sample normalization presents particular challenges in histone mark studies, as inappropriate normalization can introduce false positives or obscure true biological differences. Researchers must select normalization methods based on their underlying technical assumptions, which include balanced differential DNA occupancy, equal total DNA occupancy across states, and equal background binding [12].

Spike-in normalization methods using exogenous chromatin (e.g., Drosophila chromatin added to human samples) enable precise quantification of cell-to-cell variations in histone mark abundance [9]. The PerCell methodology exemplifies this approach, combining "well-defined cellular spike-in ratios of orthologous species' chromatin and a bioinformatic analysis pipeline to facilitate highly quantitative comparisons of 2D chromatin sequencing across experimental conditions" [9]. This strategy is particularly valuable when comparing samples with expected global changes in histone modification levels.

Background-bin methods assume that most genomic regions show no difference in occupancy between conditions, while peak-based methods normalize using only confidently bound regions. When uncertainty exists about which technical conditions are satisfied, researchers can employ a high-confidence peakset approach—"the intersection of the differentially bound peaksets obtained from using different between-sample normalization methods" [12]. Experimental analyses indicate that "roughly half of the called peaks were called as differentially bound for every normalization method," providing a robust foundation for biological interpretation [12].

Diagram 2: Normalization Strategy Selection for Differential Binding Analysis. This decision framework illustrates how experimental assumptions guide normalization method selection, with the high-confidence peakset approach providing robustness when assumptions are uncertain.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful histone mark profiling requires careful selection of core reagents matched to methodological requirements. The following essential materials represent critical components for reliable epigenomic studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Mark Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | H3K27ac: Abcam-ab4729, Diagenode C15410196H3K27me3: Cell Signaling Technology-9733 | Specifically recognizes target histone modification; primary determinant of data quality | Verify ChIP-seq-grade validation; test multiple sources/dilutions for tagmentation methods |

| Tagmentation Enzymes | Protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein (pA-Tn5) | CUT&Tag-specific enzyme that cleaves and adapts target DNA in situ | Commercial preparations vary in efficiency; requires titration for optimal performance |

| Chromatin Spike-ins | Drosophila chromatin (PerCell), defined cellular spike-in ratios | Enables quantitative cross-condition comparisons by normalizing technical variations | Species orthology ensures non-crossreacting but biologically comparable reference |

| Library Preparation | DNA extraction kits, end-polishing enzymes, PCR barcodes | Converts immunoprecipitated DNA into sequenceable libraries | Method-specific optimization needed (e.g., reduced PCR cycles for CUT&Tag) |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Control primers (e.g., ARGHAP22, COX4I2-positive; KLHL11-negative) | Benchmarks protocol performance against known targets/backgrounds | Design based on ENCODE peaks for standardized comparison |

Integrated Workflow for Method Selection

Selecting the optimal histone mark profiling strategy requires systematic consideration of experimental goals, sample limitations, and technical constraints. The following workflow provides a structured approach to method selection.

For studies requiring maximum sensitivity with limited material, CUT&Tag offers compelling advantages with its 5,000-cell requirement and superior signal-to-noise ratio. When comprehensive peak recovery is prioritized over sensitivity, traditional ChIP-seq with its higher ENCODE concordance may be preferable. In scenarios demanding precise quantification across conditions, spike-in normalized approaches like PerCell provide the rigorous normalization needed for confident differential analysis.

Emerging methodologies continue to expand the experimental toolbox. Micro-C-ChIP enables detailed investigation of histone modification patterns within 3D chromatin architecture, while improved low-cell-number ChIP-seq protocols bridge the gap between sensitivity and comprehensive coverage [5] [8]. Regardless of the selected method, rigorous antibody validation, appropriate controls, and thoughtful normalization strategies remain fundamental to generating biologically meaningful data.

As the field advances, ongoing benchmarking efforts and consortium-led standardization (exemplified by ENCODE for ChIP-seq) will be crucial for establishing best practices for newer methodologies. By carefully matching technical capabilities to biological questions, researchers can leverage these powerful tools to uncover novel insights into epigenetic regulation across diverse biological systems and disease contexts.

The choice of chromatin fragmentation method is a critical step in any Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) experiment, directly impacting data quality, specificity, and the biological interpretations drawn. For researchers investigating histone modifications and DNA-protein interactions, the decision between mechanical sonication and enzymatic micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion hinges on multiple factors, including the mark type, desired resolution, and available cell numbers. Sonication, the traditional approach, uses high-frequency sound waves to randomly shear chromatin, while MNase digestion enzymatically cleaves linker DNA between nucleosomes. Understanding their performance characteristics for different biological targets enables scientists to select the optimal protocol, conserving valuable time and resources while generating more reliable data. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison to inform these experimental decisions, framed within the broader context of optimizing ChIP-seq protocols for epigenetics research.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Sonication vs. MNase

The performance of sonication and MNase digestion varies significantly across different experimental goals. The following table summarizes key comparative metrics based on recent experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sonication vs. MNase Digestion in ChIP-seq

| Performance Metric | Sonication-Based ChIP | MNase-Based ChIP | Supporting Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP Efficiency & Sensitivity | Lower enrichment at target loci [13] | Increased IP efficiency; greater sensitivity with lower background [13] | qPCR on active genes (GAPDH, c-MYC) showed better enrichment with enzyme-digested chromatin [13] |

| Resolution | Fragment size range 150-700 bp (1-5 nucleosomes) [13] | Nucleosome-scale resolution; ideal for mapping fine-scale organization [14] | Micro-C-ChIP maps 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [14] |

| Epitope Preservation | Harsh process can damage chromatin and antibody epitopes [13] | Milder digestion better preserves chromatin integrity and antibody epitopes [13] | Preserved epitope structure leads to increased IP efficiency for targets like transcription factors [13] |

| Input Material Requirements | Conventional protocols require >10 million cells [15] | Suitable for low-input protocols (1,000–50,000 cells) [15] | nMOWChIP-seq generates high-quality data for Pol II from 1,000 cells, TFs from 5,000 cells [15] |

| Applicability to Non-Histone Targets | Standard for transcription factors (TFs) and RNA Polymerase II [15] | Effective for Pol II, TFs (EGR1, MEF2C), and enzymes (HDAC2) [15] | High-quality binding profiles reflective of functional tissue differences achieved in mouse brain [15] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MNase-Based Low-Input ChIP-seq (nMOWChIP-seq)

The native MOWChIP-seq (nMOWChIP-seq) protocol demonstrates the application of MNase digestion for profiling non-histone targets with low cell inputs. The following workflow outlines the key steps for a successful experiment.

Figure 1: MNase-based low-input ChIP-seq workflow. RT: Room Temperature.

Core Methodology [15]:

- Cell/Nuclei Input: The protocol is scalable but typically starts with 400,000 cells or nuclei suspended in Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS).

- Lysis and Permeabilization: Cells are treated with a lysis buffer containing 4% Triton X-100, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 30 mM MgCl2, and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- MNase Digestion: 10 µL of 100 mM CaCl2 and 2.5 µL of 100 U/µL MNase are added to the mixture, followed by vortexing and incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes. This digests chromatin to primarily dinucleosome-sized fragments.

- Immunoprecipitation: The digested chromatin is then processed using a microfluidics-based MOWChIP-seq platform, which enables highly efficient IP from small volumes and low cell numbers.

- Application: This protocol has been successfully used to profile RNA Polymerase II (with 1,000 cells), transcription factor EGR1 (with 5,000 cells), and HDAC2 (with 50,000 cells) from mouse brain tissues, revealing binding profiles that reflect functional differences between brain regions.

Micro-C-ChIP for Histone-Mark-Specific 3D Architecture

Micro-C-ChIP is an advanced strategy that combines MNase digestion with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization for specific histone modifications at nucleosome resolution.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Micro-C-ChIP and Enzyme-Based ChIP

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Feature | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit [13] | Contains all buffers/reagents for enzymatic IP; uses Protein G beads. | General ChIP for endogenous protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications in mammalian cells. |

| MNase (Micrococcal Nuclease) [14] [15] | Enzymatically digests chromatin; preserves nucleosomes for high-resolution fragmentation. | Core enzyme for Micro-C-ChIP and nMOWChIP-seq; enables nucleosome-scale mapping. |

| pA-Tn5 Transposase [7] | Enzyme-tethering for tagmentation in CUT&Tag; enables in-situ fragmentation and tagging. | Used in CUT&Tag as an alternative to ChIP-seq for high-sensitivity profiling. |

| H3K27ac Antibodies (e.g., Abcam-ab4729) [7] | ChIP-grade antibody for immunoprecipitation of specific histone marks. | Critical for targeting active enhancers and promoters in mark-specific protocols. |

| Dual Crosslinkers (Formaldehyde/DSG) [14] | Stabilizes protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions in situ before fragmentation. | Used in Micro-C-ChIP to capture genuine 3D chromatin interactions. |

Core Methodology [14]:

- Crosslinking: Cells are dually crosslinked to preserve chromatin interactions.

- Chromatin Digestion and Processing: Nuclei are isolated and digested with MNase. The DNA ends are biotin-labeled, and proximity ligation is performed in situ to capture 3D interactions.

- Solubilization and Immunoprecipitation: The ligated chromatin is sonicated to solubilize heavily cross-linked material before immunoprecipitation with antibodies against specific histone marks like H3K4me3 or H3K27me3.

- Validation: The protocol has been benchmarked in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and human retinal pigment epithelial cells, revealing extensive promoter-promoter contact networks and distinct 3D architecture of bivalent promoters. It validates that the detected features are genuine 3D interactions and not ChIP-enrichment biases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental for successful ChIP experiments. The following table details key solutions used in the methodologies discussed.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Fragmentation and IP

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Feature | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit [13] | Contains all buffers/reagents for enzymatic IP; uses Protein G beads. | General ChIP for endogenous protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications in mammalian cells. |

| MNase (Micrococcal Nuclease) [14] [15] | Enzymatically digests chromatin; preserves nucleosomes for high-resolution fragmentation. | Core enzyme for Micro-C-ChIP and nMOWChIP-seq; enables nucleosome-scale mapping. |

| pA-Tn5 Transposase [7] | Enzyme-tethering for tagmentation in CUT&Tag; enables in-situ fragmentation and tagging. | Used in CUT&Tag as an alternative to ChIP-seq for high-sensitivity profiling. |

| H3K27ac Antibodies (e.g., Abcam-ab4729) [7] | ChIP-grade antibody for immunoprecipitation of specific histone marks. | Critical for targeting active enhancers and promoters in mark-specific protocols. |

| Dual Crosslinkers (Formaldehyde/DSG) [14] | Stabilizes protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions in situ before fragmentation. | Used in Micro-C-ChIP to capture genuine 3D chromatin interactions. |

Decision Framework and Concluding Insights

The choice between sonication and MNase digestion is not one-size-fits-all but should be guided by the specific research question. The following diagram synthesizes the experimental data into a decision framework to help researchers select the optimal fragmentation strategy.

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting a chromatin fragmentation method.

In conclusion, MNase digestion presents significant advantages for projects requiring nucleosome-resolution mapping of histone modifications, low-input workflows, and studies of fine-scale chromatin architecture [14] [15]. Sonication remains a robust and widely adopted method for standard transcription factor ChIP-seq. However, with the development of optimized protocols like nMOWChIP-seq, MNase is proving to be a versatile tool capable of handling a broad spectrum of targets, including non-histone proteins [15]. By aligning the fragmentation method with the experimental objectives outlined in this framework, researchers can maximize data quality and biological insight from their ChIP-seq studies.

Sequencing Depth and Coverage Requirements for Comprehensive Epigenome Mapping

In the field of epigenomics, sequencing depth and coverage are two fundamental metrics that determine the quality and reliability of generated data. While often used interchangeably, these terms describe distinct concepts. Sequencing depth, also called read depth, refers to the average number of times a specific nucleotide in the genome is read during the sequencing process [16]. It is typically expressed as a multiple (e.g., 30x), and a higher depth increases confidence in base calling, which is particularly important for detecting rare variants or working with heterogeneous samples [16] [17]. In contrast, sequencing coverage refers to the percentage of the target genome or region that has been sequenced at least once [16] [17]. This metric, usually expressed as a percentage (e.g., 95%), indicates the comprehensiveness of the sequencing effort and helps identify gaps in the data [16].

The relationship between depth and coverage is crucial for experimental design in epigenome mapping. In theory, increasing sequencing depth can also improve coverage, as more reads enhance the likelihood of covering more genomic regions [16]. However, due to technical biases in library preparation or sequencing, certain regions may remain underrepresented regardless of depth [16]. A successful sequencing project must strike a balance between sufficient depth to confidently detect variants and comprehensive coverage to ensure the entire target region is represented [16] [17]. This balance is especially critical in epigenomics, where many marks of interest occur in challenging genomic regions with high GC content, repetitive elements, or other complexities [16].

Key Metrics and Their Impact on Data Quality

Quantitative Requirements for Epigenomic Applications

Different epigenomic applications have varying requirements for sequencing depth and coverage, driven by their specific biological questions and technical considerations. The table below summarizes recommended sequencing parameters for major epigenomic approaches:

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth and Coverage for Epigenomic Applications

| Application | Recommended Depth | Recommended Coverage | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | 5×-30× [18] | Varies with depth [18] | 5×-10× sufficient for large DMRs; 15×+ for single CpG resolution; Balance with biological replicates [18] |

| ChIP-seq (Transcription Factors) | 10-50 million reads [17] | Dependent on antibody efficiency [19] | Lower depth may suffice for strong, focal binding sites [19] |

| ChIP-seq (Histone Marks) | 10-50 million reads [17] | Dependent on mark distribution [19] | Broad domains (H3K27me3) require more sequencing; Sharp marks (H3K4me3) need less [19] |

| Micro-C-ChIP | Varies by target [14] | Focused on specific histone marks [14] | Enriches for specific PTMs (H3K4me3, H3K27me3); Reduces sequencing burden [14] |

| CUT&RUN/CUT&Tag | Lower than ChIP-seq [20] | High with proper optimization [20] | Lower background noise allows reduced sequencing depth [20] |

For WGBS, the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Project recommends a combined total coverage of 30× across replicates [18]. However, studies have demonstrated that for differential methylated region (DMR) discovery, the gains in true positive rate (TPR) increase sharply up to 8×-10× coverage, with diminishing returns at higher levels [18]. This relationship holds true even for comparisons between closely related cell types, where methylation differences are relatively small [18]. Importantly, the number of CpGs covered by at least one read drops rapidly from 90% to 50% as coverage decreases from 5× to 1×, directly contributing to sensitivity loss in poorly covered regions [18].

For ChIP-seq applications, requirements vary significantly based on the target. Transcription factor binding sites typically require 10-50 million reads, while histone mark mapping needs similar depth but is influenced by the nature of the mark [17]. Sharp, punctate marks like H3K4me3 require less sequencing than broad domains like H3K27me3 [19]. Newer methods like CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag generally require lower sequencing depth than traditional ChIP-seq due to their higher signal-to-noise ratio [20].

Impact on Variant Detection and Data Completeness

Both sequencing depth and coverage directly impact the ability to detect true biological signals while minimizing false positives. Higher sequencing depth provides greater statistical confidence in variant calling, as multiple reads allow for correction of potential sequencing errors [16] [17]. This is particularly crucial for clinical applications where missing a variant or falsely identifying one can have significant consequences [16]. In cancer genomics, for example, detecting low-frequency mutations may require sequencing depths of 500× to 1000× to identify rare variants within heterogeneous tumor samples [17].

Coverage uniformity is equally important, as it ensures equitable sampling of all genomic regions [17] [21]. Two genomes could be sequenced to the same average coverage (e.g., 30×), but one might have low uniformity with some regions uncovered and others covered 60 times, while the second has highly uniform coverage with every region covered 25-35 times [21]. The second genome provides more reliable biological interpretation despite having the same average coverage [21]. Regions with extreme GC content, repetitive elements, or secondary structures often exhibit coverage dropouts that can lead to missed biological insights [16] [17].

Experimental Design and Protocol Comparison

ChIP-seq Methodology and Optimization

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) remains a cornerstone technology for epigenome mapping, particularly for histone modifications [22] [4] [19]. The standard ChIP-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps that influence the final data quality and necessary sequencing depth:

Table 2: Key Optimization Parameters in ChIP-seq Experiments

| Parameter | Optimization Considerations | Impact on Depth/Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Number | Minimum 500,000 cells; typically millions per ChIP [19] | Lower cell numbers may require increased sequencing depth |

| Cross-linking | Formaldehyde concentration and time course optimization [19] | Excessive cross-linking reduces efficiency, requiring more sequencing |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Sonication or MNase to 150-300 bp fragments [19] | Larger fragments lower resolution; excessive fragmentation reduces yields |

| Antibody Selection | Specificity and efficiency critical [19] | Poor antibodies increase background, requiring greater depth for signal |

| Replicates | Minimum 3 biological replicates recommended [19] | More replicates reduce required depth per sample for statistical power |

The success of a ChIP experiment heavily depends on antibody specificity, particularly for histone modifications where cross-reactivity can significantly mislead biological conclusions [19]. The recent development of SNAP-ChIP spike-in technology uses DNA-barcoded designer nucleosomes to assess histone PTM antibody performance directly in ChIP experiments, providing more reliable validation than surrogate assays [19].

Emerging Technologies and Their Advantages

Several emerging technologies have improved upon traditional ChIP-seq, offering enhanced resolution with reduced sequencing requirements:

CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) and CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation) are increasingly popular alternatives to ChIP-seq [4] [20]. These techniques immobilize cells on magnetic beads and use a protein A-MNase fusion (CUT&RUN) or protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion (CUT&Tag) to cleave or tag DNA at specific binding sites [4]. Both methods offer higher resolution (~20 bp for CUT&RUN), lower background noise, and require significantly less sequencing depth than ChIP-seq [4] [20]. CUT&Tag further simplifies library construction by combining fragmentation and adapter incorporation into a single step [4].

Micro-C-ChIP represents another advancement that combines Micro-C with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [14]. This approach specifically enriches for histone mark-associated interactions, dramatically reducing sequencing costs compared to genome-wide methods [14]. While conventional Hi-C or Micro-C may require over a billion sequencing reads to achieve nucleosome-scale resolution, Micro-C-ChIP achieves high-resolution interaction mapping with substantially fewer reads by focusing on epigenetically defined regions [14].

ChIP-seq Workflow

Technology Performance Comparison

Sequencing Platform Considerations

The choice of sequencing technology significantly impacts the required depth and coverage for epigenomic studies. Different platforms offer distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 3: Sequencing Platform Comparison for Epigenomic Applications

| Platform | Read Length | Advantages | Limitations | Impact on Depth/Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Short (50-300 bp) [22] | High accuracy, low cost per base [21] | Limited in complex regions [21] | Standard for ChIP-seq; may require higher depth for complex areas |

| PacBio HiFi | Long (10-20 kb) [21] | High accuracy, resolves repetitive regions [21] | Higher cost per sample [21] | 20× coverage often sufficient for variant calling [21] |

| Nanopore | Long (varies) [21] | Real-time sequencing, detects modifications [21] | Higher error rate [21] | May require greater depth for accurate base calling |

Studies have demonstrated that 20× coverage with highly accurate PacBio HiFi reads can exceed the utility of 20× (and even 80×) coverage using nanopore sequencing for applications like de novo assembly [21]. Similarly, for variant calling, 20× HiFi genome sequencing achieves over 99% of the 30× F1 score for SNVs and structural variants [21]. This highlights how read accuracy and uniformity can reduce overall sequencing requirements while maintaining data quality.

Cost-Benefit Analysis and Optimization Strategies

Effective experimental design requires balancing sequencing costs with scientific requirements. Several strategies can optimize this balance:

First, clearly define study objectives, as this dramatically influences depth requirements [16] [17]. Whole-genome sequencing typically needs higher depth (e.g., 30×) to avoid data gaps, while targeted approaches may function well with lower depth (10×-20×) [17]. Studies investigating rare variants or heterogeneous samples often demand greater depth (50×+) [17].

Second, consider the trade-off between sequencing depth and biological replicates. For DMR identification using WGBS, sensitivity is maximized by maintaining coverage between 5× and 10× per sample and increasing biological replicates rather than sequencing individual libraries more deeply [18]. With a fixed total sequencing budget, dedicating resources to more replicates typically provides better statistical power than increasing depth per sample beyond 10×-15× [18].

Third, leverage targeted approaches when possible. Methods like Methyl-seq (for DNA methylation) or Micro-C-ChIP (for 3D chromatin structure) enrich for specific regions or modifications of interest, dramatically reducing sequencing costs while maintaining high resolution in relevant genomic areas [14] [20].

Epigenomic Technology Comparison

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful epigenome mapping requires carefully selected reagents and controls at each experimental stage. The following table outlines key solutions for robust epigenomic studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenomic Mapping

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9ac, H3K36me3 [22] [23] | Target-specific enrichment; Quality critical for signal-to-noise ratio [19] |

| Validation Tools | SNAP-ChIP spike-in controls [19] | Assess antibody performance directly in ChIP experiments [19] |

| Fragmentation Enzymes | Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) [19] | Digest chromatin to mononucleosome-sized fragments [19] |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Formaldehyde, DSG [19] | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions [19] |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina-compatible kits [22] | Prepare sequencing libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA [22] |

| Control Antibodies | Normal IgG [19] | Assess non-specific background signal [19] |

| Spike-in Chromatin | Drosophila chromatin [23] | Normalize across samples and detect global changes [23] |

Antibody quality remains particularly crucial for histone modification studies. Histone PTM antibodies are notorious for cross-reactivity, which can significantly mislead biological conclusions [19]. SNAP-ChIP Certified Antibodies, validated for high specificity and efficiency directly in ChIP assays, provide more reliable results than those tested only with surrogate assays like peptide arrays or immunoblotting [19]. For chromatin-associated proteins, sourcing 3-5 antibodies from different vendors that target distinct epitopes is recommended when ChIP-grade validated antibodies are unavailable [19].

Sequencing depth and coverage requirements for comprehensive epigenome mapping vary significantly across applications, with WGBS typically requiring 5×-30× coverage depending on the study goals [18], while ChIP-seq needs 10-50 million reads based on the target [17]. Emerging technologies like CUT&Tag and Micro-C-ChIP offer paths to reduced sequencing burdens through improved signal-to-noise ratios and targeted enrichment strategies [14] [20]. As sequencing technologies evolve with improved accuracy and read lengths, the established standards for adequate depth and coverage continue to be redefined [21]. However, the fundamental principle remains: optimal experimental design must balance technical requirements with biological questions, always considering the critical trade-off between sequencing depth and the number of biological replicates [18]. By applying the guidelines and comparisons presented herein, researchers can design more efficient and effective epigenomic studies that maximize insights while optimizing resource utilization.

Practical Protocol Selection and Optimization for Specific Histone Marks

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become the cornerstone method for genome-wide profiling of histone modifications, providing critical insights into the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Histone post-translational modifications represent a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that regulates chromatin structure and transcriptional accessibility without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications exhibit distinct genomic distributions and functional consequences, necessitating optimized experimental protocols for accurate mapping. The dynamic nature of the epigenome means that these chromatin states are distinctive for different tissues, developmental stages, and disease states and can also be altered by environmental influences [22].

This guide objectively compares ChIP-seq protocols for five key histone marks: H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3. We present summarized quantitative data from published studies, detailed methodologies for key experiments, and essential reagent specifications to assist researchers in selecting and optimizing protocols for their specific experimental needs. Understanding the precise relationship between local patterns of histone mark enrichment and regulatory consequences requires robust and mark-specific methodological approaches [24].

Biological Functions and Genomic Distributions

Each histone modification occupies specific genomic territories and performs unique regulatory functions, which directly influence experimental design considerations for their successful profiling.

H3K4me3 is predominantly enriched at transcription start sites (TSSs) of actively transcribed genes or genes poised for transcription. This mark is recognized as a hallmark of promoter regions and is strongly associated with active transcription initiation. In HIV-infected individuals, for example, high levels of H3K4me3 in neutrophils lead to dysregulation of DNA transcription, with spectacular abnormalities observed in exons, introns, and promoter-TSS regions [25].

H3K27ac is a marker of active enhancers and promoters, distinguishing actively used regulatory elements from their inactive counterparts. This highly cell type-specific histone modification has been implicated in complex diseases, including neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders [7]. H3K27ac characterizes what are known as "stretch" enhancers, which are particularly important in defining cell identity.

H3K4me1 primarily marks enhancer regions, both poised and active. While traditionally associated with KMT2C/D (MLL3/4) catalytic activity, recent research indicates that a majority of enhancers retain H3K4me1 in KMT2C/D catalytic mutant cells, with KMT2B contributing to H3K4me1 at KMT2C/D-independent candidate enhancers [26]. This modification facilitates promoter-enhancer interactions and gene activation during cellular differentiation.

H3K27me3, catalyzed and maintained by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), is associated with transcriptional repression in a cell type-specific manner [24]. This mark can exhibit three distinct enrichment profiles: broad domains across gene bodies (canonical repression), peaks around TSSs of bivalent genes (co-occurring with H3K4me3), and surprisingly, peaks in promoters of actively transcribed genes in specific contexts.

H3K36me3 is enriched across the transcribed regions of actively expressed genes, with its presence correlating with transcriptional elongation. This mark plays crucial roles in coupling transcription with RNA processing mechanisms [22].

Table 1: Biological Functions and Genomic Distributions of Key Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Primary Genomic Location | Transcriptional Association | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcription start sites (TSSs) | Active/poised transcription | Promoter marker; transcription initiation |

| H3K27ac | Active enhancers and promoters | Active transcription | Distinguishes active regulatory elements; cell identity |

| H3K4me1 | Enhancer regions (poised and active) | Variable (enhancer activity) | Enhancer marking; facilitates promoter-enhancer contacts |

| H3K27me3 | Broad domains or focused peaks | Repressed transcription | Polycomb-mediated repression; developmental regulation |

| H3K36me3 | Gene bodies | Active transcription | Elongation marker; transcription-coupled processes |

Comparative Analysis of Protocol Parameters

Crosslinking and Chromatin Preparation

The initial steps of ChIP-seq protocols significantly impact data quality across different histone marks. For standard ChIP-seq, proteins are covalently crosslinked to their genomic DNA substrates in living cells using formaldehyde, typically at a concentration of 1% for 10 minutes at room temperature [24] [22]. The crosslinking reaction is stopped using glycine, followed by cell lysis and chromatin fragmentation.

Chromatin shearing represents a critical parameter that varies depending on the histone mark being studied. For most histone modifications, sonication parameters are optimized to produce DNA fragments between 200-500 bp, balancing resolution and immunoprecipitation efficiency. An optimized protocol for Chromochloris zofingiensis established that 6-10 seconds of sonication (1 second ON/1 second OFF, amplitude 50%) using a Sonic Dismembrator System achieved optimal fragmentation for H3K4me3 profiling [27]. The Bioruptor UCD-200 (Diagenode) or equivalent systems are commonly used for this purpose.

For challenging samples like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, additional optimization is required. A 2025 protocol established that single-cell preparation from FFPE tissues requires deparaffinization, rehydration, mechanical disruption, and 0.3% collagenase/dispase digestion, followed by heat treatment at 50°C for 60 min in TE buffer to enhance antigen retrieval [28].

Immunoprecipitation and Sequencing

Antibody selection and immunoprecipitation conditions represent the most mark-specific aspects of ChIP-seq protocols. The following table summarizes key experimental parameters for each histone modification based on published studies and optimized protocols:

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Parameters for Histone Mark ChIP-seq

| Histone Mark | Recommended Antibodies | Cell Input Requirements | Sequencing Depth | Key Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys4) (C42D8) rabbit mAb (CST #9751S) [22] | 1-10 million cells [22] [7] | 10-20 million reads | Sharp peaks at TSSs; high signal-to-noise |

| H3K27ac | Abcam-ab4729 (1:100) [7] | 1-10 million cells [22] [7] | 15-25 million reads | Defined enhancer peaks; cell type-specificity |

| H3K4me1 | Anti-Mono-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys4) rabbit Ab (Diagenode #pAb-037-050) [22] | 1-10 million cells [22] | 15-25 million reads | Broad enhancer domains; correlation with H3K27ac |

| H3K27me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) (C36B11) rabbit mAb (CST #9733S) [22] | 1-10 million cells [22] [7] | 20-30 million reads | Broad domains; appropriate signal breadth |

| H3K36me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys36) rabbit Ab (CST #9763S) [22] | 1-10 million cells [22] | 20-30 million reads | Gene body enrichment; correlation with expression |

For H3K27ac, systematic benchmarking has tested multiple ChIP-grade antibody sources including Abcam-ab4729 (used in ENCODE), Diagenode C15410196, Abcam-ab177178, and Active Motif 39133 at various dilutions (1:50, 1:100, 1:200) [7]. The addition of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) like Trichostatin A (TSA; 1 µM) or sodium butyrate (NaB; 5 mM) to stabilize acetyl marks during CUT&Tag showed no consistent improvement in total peak detection or signal-to-noise ratio [7].

For all marks, sequencing depth requirements vary based on the genomic distribution characteristics. Sharp, focused marks like H3K4me3 require less sequencing depth than broad marks like H3K27me3 and H3K36me3, which spread across large genomic regions.

Benchmarking Against Alternative Methods

CUT&Tag as an Emerging Alternative

Cleavage Under Targets & Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) has emerged as a promising alternative to ChIP-seq, particularly for limited cell numbers. Comprehensive benchmarking of CUT&Tag against established ENCODE ChIP-seq profiles in K562 cells for H3K27ac and H3K27me3 reveals that CUT&Tag recovers an average of 54% of known ENCODE peaks for both histone modifications [7]. This performance represents the strongest ENCODE peaks, with functional and biological enrichments equivalent to ChIP-seq.

The key advantages of CUT&Tag include substantially reduced cellular input requirements (approximately 200-fold reduction, to about 200 cells) and 10-fold reduced sequencing depth requirements compared to ChIP-seq [7]. The method utilizes permeabilized nuclei where antibodies bind chromatin-associated factors, tethering protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein (pA-Tn5) that cleaves intact DNA and inserts adapters for sequencing.

However, CUT&Tag optimization requires careful parameter adjustment. Initial analyses revealed high duplication rates across samples (55.49%-98.45%, mean: 82.25%), necessitating optimization of PCR cycle numbers to reduce duplication rates [7]. Peak calling also requires mark-specific optimization, with MACS2 and SEACR representing the most commonly used algorithms.

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice between ChIP-seq and CUT&Tag depends on multiple experimental factors:

- Sample availability: CUT&Tag is strongly preferred for low cell numbers (<50,000 cells)

- Antibody quality: Both methods require high-quality antibodies, but CUT&Tag may be more sensitive to antibody specificity

- Budget constraints: CUT&Tag requires less sequencing depth, reducing costs

- Established benchmarks: ChIP-seq has more established benchmarks and reference datasets

- Broad domains: Both methods perform well for broad marks like H3K27me3, with CUT&Tag showing excellent performance

For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, ChIP-seq protocols have been successfully adapted. A 2025 study established a robust ChIP-seq protocol for FFPE lymphoid tissue that includes single-cell preparation, heat treatment for antigen retrieval, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate specific cell populations, chromatin shearing, and immunoprecipitation [28]. This protocol successfully profiled H3K27ac in nodal T follicular helper cell lymphoma, demonstrating that cell sorting prior to ChIP-seq removes interference signals from non-target cell components.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard ChIP-seq Protocol

The fundamental ChIP-seq workflow involves multiple standardized steps with mark-specific optimizations:

Diagram 1: Core ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

Step 1: Cell Crosslinking - Crosslink proteins to DNA using 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Quench with glycine [24] [22].

Step 2: Chromatin Preparation and Shearing - Resuspend cell pellet in cell lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 1% igepal) with protease inhibitors. Pellet nuclei and resuspend in nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) with protease inhibitors. Sonicate using a Bioruptor UCD-200 or equivalent to achieve 200-500 bp fragments [22]. For specific marks like H3K4me3 in green algae, optimal shearing was achieved with 6-10 seconds of sonication (1s ON/1s OFF, amplitude 50%) [27].

Step 3: Immunoprecipitation - Dilute chromatin 3-fold with IP dilution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% igepal, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitors. Incubate with mark-specific antibodies (see Table 2 for recommendations) overnight at 4°C with rotation. Add protein A/G beads and incubate 2 hours. Wash beads sequentially with low salt, high salt, and LiCl wash buffers, followed by TE buffer [22].

Step 4: DNA Purification and Library Preparation - Elute ChIP DNA with elution buffer (50 mM NaHCO3, 1% SDS). Reverse crosslinks by adding NaCl to 200 mM and incubating at 65°C overnight. Treat with RNase A and proteinase K, then purify DNA using QIAquick PCR purification kit or equivalent. Prepare sequencing libraries using Illumina-compatible protocols [22].

CUT&Tag Protocol for Histone Modifications

For CUT&Tag, the protocol differs significantly from ChIP-seq:

Diagram 2: CUT&Tag Workflow for Histone Modifications

Step 1: Cell Permeabilization - Bind concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads to cells. Permeabilize cells with digitonin-containing buffer.

Step 2: Antibody Binding - Incubate with primary antibody against specific histone mark (optimized dilutions: 1:50-1:100) overnight at 4°C [7].

Step 3: pA-Tn5 Binding - Incubate with pA-Tn5 transposase (1:250 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature.

Step 4: Tagmentation - Wash unbound pA-Tn5, then activate tagmentation by adding Mg2+ and incubating for 1 hour at 37°C.

Step 5: DNA Extraction and Library Amplification - Extract DNA using SDS/proteinase K treatment. Purify and amplify libraries with optimized PCR cycles (typically 12-15 cycles to minimize duplicates) [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful profiling of histone modifications requires high-quality, specific reagents. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for histone mark ChIP-seq:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification Profiling

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application Notes | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | • H3K4me3: CST #9751S• H3K27ac: Abcam-ab4729• H3K4me1: Diagenode #pAb-037-050• H3K27me3: CST #9733S• H3K36me3: CST #9763S [22] [7] | Validate specificity with peptide competition; titrate for optimal signal | Western blot on cell lysates; peptide blocking assays |

| Cell Lysis & IP Buffers | • Cell lysis: 5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 1% igepal• Nuclei lysis: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS• IP dilution: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% igepal, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA [22] | Add fresh protease inhibitors; optimize SDS concentration for different marks | Fragment size analysis post-sonication; crosslinking reversal efficiency |

| Chromatin Shearing Systems | • Bioruptor UCD-200 (Diagenode)• Sonic Dismembrator System (Fisher Scientific) [27] [22] | Optimize time/amplitude for cell type; keep samples cold during sonication | Agarose gel electrophoresis (200-500 bp ideal) |

| DNA Purification & Library Prep | • QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN)• Illumina Library Prep Kits | Size selection critical for H3K27me3 broad domains; avoid over-amplification | Bioanalyzer/Fragment Analyzer for library quality |

| Positive Control Primers | • H3K4me3: Active promoters (e.g., ARGHAP22, COX4I2)• H3K27me3: Repressed promoters (e.g., HOX genes) [7] | Include negative control regions; validate in each cell type | qPCR enrichment compared to input (10-20x typical) |

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment

Peak Calling and Data Processing

The analysis of ChIP-seq data requires mark-specific parameters to account for their distinct genomic distributions. For sharp marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, MACS2 with standard peak calling parameters works effectively. For broad domains like H3K27me3, alternative approaches such as SICER or MACS2 with the --broad flag are recommended.

For CUT&Tag data, benchmarking indicates that both MACS2 (with parameters: q-value threshold 1×10-5, nolambda, nomodel) and SEACR (stringent settings with threshold 0.01) perform well for peak calling [7]. The evaluation of CUT&Tag data should include assessment of duplication rates (which ranged from 55.49% to 98.45% in initial studies), TSS enrichment scores, and FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) scores.

Quality Control Metrics

Quality assessment should include both general and mark-specific metrics:

- Sequencing depth: 10-30 million reads depending on the mark (see Table 2)

- Library complexity: Assessed by PCR bottleneck coefficient (PBC)

- Fragment size distribution: Confirm expected size ranges

- Enrichment at expected regions: TSS for H3K4me3, gene bodies for H3K36me3

- Reproducibility: High correlation between biological replicates (Pearson R > 0.9)

For H3K27me3 specifically, quality assessment should verify the presence of broad domains rather than sharp peaks, as this mark can exhibit three distinct enrichment profiles: broad domains across gene bodies corresponding to canonical repression, peaks around transcription start sites associated with bivalent genes, and promoter peaks associated with active transcription in specific contexts [24].

The comparative analysis of mark-specific protocol variations for H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 reveals both universal principles and mark-specific requirements. While the core ChIP-seq workflow remains consistent, critical variations in chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation conditions, antibody selection, and data analysis parameters significantly impact results quality.

The emergence of CUT&Tag as a viable alternative to ChIP-seq offers advantages for low-input applications, though with currently lower sensitivity (approximately 54% of ENCODE peaks recovered) [7]. The choice between methods should consider sample availability, experimental goals, and resource constraints.

As epigenetic profiling continues to advance into more complex samples including FFPE tissues [28] and single-cell applications, continued optimization of these mark-specific protocols will be essential for generating accurate, reproducible maps of the epigenome in health and disease.

Low-Input and Single-Cell ChIP-seq Methods for Rare Cell Populations and Clinical Samples

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become the foundational method for genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions and histone post-translational modifications (hPTMs). However, conventional ChIP-seq protocols require substantial input material (typically 0.5-1 million cells per immunoprecipitation), rendering them incompatible with rare cell populations, limited clinical samples, or heterogeneous tissues requiring single-cell resolution. The emergence of low-input and single-cell ChIP-seq technologies has revolutionized epigenomic research by enabling the exploration of epigenetic heterogeneity and the profiling of rare cell types that were previously inaccessible. These advanced methodologies overcome the limitations of traditional ChIP-seq through strategic innovations in microfluidics, molecular barcoding, enzymatic fragmentation, and automated sample processing. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of cutting-edge low-input and single-cell ChIP-seq methods, detailing their experimental workflows, performance characteristics, and optimal applications for different histone marks and research scenarios.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Micro-C-ChIP: Nucleosome Resolution 3D Genome Mapping

Experimental Protocol: Micro-C-ChIP combines micrococcal nuclease (MNase)-based chromatin fragmentation (Micro-C) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization for specific histone modifications at nucleosome resolution [5]. The protocol begins with dual crosslinking of cells using disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) followed by formaldehyde. Nuclei are then isolated and subjected to MNase digestion that cleaves accessible linker DNA while leaving nucleosomes intact. The digested DNA ends are biotin-labeled, and proximity ligation is performed in situ to capture chromatin interactions. Following ligation, chromatin is sonicated to solubilize heavily cross-linked fragments before immunoprecipitation with histone modification-specific antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) [5]. The optimal sonication conditions must be carefully determined to release proximity-ligated dinucleosomal-sized DNA fragments (∼300-500 bp) into the soluble fraction while maintaining epitope integrity for immunoprecipitation.

Key Advantages: Micro-C-ChIP achieves nucleosome-resolution mapping of histone mark-specific chromatin interactions while maintaining a high fraction (∼42%) of informative reads—significantly superior to alternative methods like MChIP-C (4%) [5]. The method preserves genuine 3D interactions through in situ proximity ligation prior to immunoprecipitation, avoiding non-specific ligation artifacts that plague other approaches. Input-based normalization using bulk Micro-C data as a reference accounts for chromatin accessibility biases, ensuring that observed interactions reflect true biological enrichment rather than technical artifacts [5].

Drop-ChIP: Single-Cell Epigenomic Profiling

Experimental Protocol: Drop-ChIP utilizes drop-based microfluidics (DBM) to process individual cells in ∼50 micron-sized aqueous drops [29]. The workflow involves several integrated steps: (1) A co-flow drop maker module mixes a suspension of dissociated cells with weak detergent and MNase milliseconds before encapsulating individual cells in drops; (2) A barcode library containing 1152 distinct oligonucleotide adaptors is prepared in separate drops, with each drop containing multiple copies of a single barcode; (3) A 3-point merging device fuses each nucleosome-containing drop with a single barcode-containing drop and enzymatic buffer containing DNA ligase; (4) Barcoded adaptors are ligated to both ends of nucleosomal DNA fragments, indexing them to their cell of origin; (5) Indexed chromatin from ∼100 cells is combined with carrier chromatin from a different organism before performing pooled ChIP and library preparation [29].

Critical Optimization Steps: Cell density must be titrated to ensure only 1 in 6 drops contains a cell, minimizing multiplets. Barcode assignment is controlled such that >95% of barcodes are unique to a single cell. Following sequencing, data is filtered to include only reads with symmetric barcodes on both sides of nucleosomal inserts and to exclude over-represented barcodes that may have labeled multiple cells [29]. The method typically yields 500-10,000 unique reads per cell, enabling identification of distinct epigenetic states and cellular heterogeneity patterns.

PnP-ChIP-Seq: Automated Low-Input Profiling