Optimizing RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis: A Practical Guide for Parameter Selection and Pipeline Configuration

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of parameter optimization in RNA-Seq differential expression analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

Optimizing RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis: A Practical Guide for Parameter Selection and Pipeline Configuration

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of parameter optimization in RNA-Seq differential expression analysis for researchers and drug development professionals. With numerous available tools and workflows, selecting appropriate methods and parameters significantly impacts the accuracy and biological relevance of results. The article systematically explores foundational RNA-Seq concepts, methodological comparisons of popular tools, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and validation approaches for pipeline optimization. By synthesizing current evidence from comparative studies, we provide actionable recommendations for constructing robust analysis pipelines tailored to specific experimental designs, sample sizes, and biological questions, ultimately enhancing the reliability of transcriptomic insights in biomedical research.

Understanding the RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow: From Raw Reads to Expression Matrix

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Should I always trim my RNA-Seq reads before alignment? While trimming can remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences to improve mapping accuracy, it must be applied with caution. Aggressive trimming can severely shorten reads and introduce unpredictable biases in gene expression estimates. It is recommended to use trimming non-aggressively and in conjunction with a minimum read length filter (e.g., retaining only reads longer than 50 bp) to prevent spurious mapping of short reads that disproportionately affect expression levels [1] [2].

Q2: I get a "no valid exon lines in the GTF file" error during alignment. How can I fix it? This is a common error indicating a problem with your annotation file. The solution is to ensure that the chromosome identifiers in your GTF file exactly match those in the reference genome you are mapping against. For example, if your genome uses "chr1" and your GTF uses "1", they will not match [3]. You can fix this by:

- Easier option: Downloading a GTF file from the same data provider (e.g., UCSC) as your reference genome [3].

- Alternative option: Converting the chromosome identifiers in your GTF file to match the genome using tools like

Replace columnin Galaxy, though this is more complex [3].

Q3: My alignment tool reports a "quality string length is not equal to sequence length" error. What does this mean? This error typically means that one of your FASTQ read files is truncated, or corrupted. The tool expects the sequence and quality score lines to be of equal length for every read. You should not proceed with the analysis, as the tool may produce incomplete and misleading results. Re-upload your data or re-run the file transfer to ensure the FASTQ files are intact [3].

Q4: What is the minimum number of biological replicates needed for a differential expression analysis? While it is technically possible to run an analysis with only two replicates, this greatly reduces your ability to estimate biological variability and control false discovery rates. A minimum of three replicates per condition is often considered the standard for hypothesis-driven experiments. However, more replicates are strongly recommended when biological variability is expected to be high, as they provide greater statistical power to detect true differences in gene expression [4].

Q5: Why is normalization of read counts necessary? Raw read counts are not directly comparable between samples because the total number of sequenced reads (the sequencing depth) can vary. A sample with more total reads will naturally have higher counts for most genes. Normalization adjusts these counts mathematically to remove this technical bias, allowing for meaningful comparisons of gene expression levels across different samples [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Alignment Rate After Trimming

- Problem: After running a trimming tool, a very low percentage of your reads successfully align to the reference.

- Investigation & Solution:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly aggressive trimming | Check the length distribution of reads after trimming. | Apply less stringent quality thresholds and always use a minimum length filter (e.g., discard reads < 50 bp) [1] [2]. |

| Incorrect adapter sequences | Use FastQC to check if adapter content is still high after trimming. | Ensure the correct adapter sequences were provided to the trimming tool (e.g., Trimmomatic, Cutadapt) [4]. |

Issue: Gene Expression Quantification Errors for Gene Families

- Problem: Genes with high sequence similarity to other genes (e.g., gene families) may have their expression levels severely underestimated or overestimated.

- Background: This is caused by "multi-mapped" reads—reads that can align equally well to multiple locations in the genome. Different quantification tools handle these reads differently, leading to systematic biases. Many of these genes are relevant to human disease [5].

- Solution Strategy: Consider using a two-stage analysis where multi-mapped reads are uniquely assigned to a group of genes (e.g., the entire gene family) rather than being discarded or randomly assigned. This allows you to extract biological signal from otherwise lost data and analyze expression at the gene-group level [5].

Issue: Choosing a Quantification Method

- Problem: With many tools available, it is difficult to choose a method for quantifying gene expression from aligned reads.

- Guidance: The choice depends on your goals and computational constraints. The table below summarizes the core approaches:

| Method Type | Description | Common Tools | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-Based Counting | Reads are aligned to a genome, then assigned to genes. | STAR, HISAT2, featureCounts, HTSeq-count [4] [1]. | More computationally intensive. Better for discovering novel transcripts or splice junctions [5]. |

| Pseudoalignment | Faster method that estimates abundance without full base-by-base alignment. | Kallisto, Salmon [4]. | Much faster and less memory-intensive. Well-suited for large datasets and standard differential expression analysis [4]. |

A systematic study comparing 192 analysis pipelines found that pipelines utilizing Salmon (a pseudoaligner) generally demonstrated high accuracy for raw gene expression quantification [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and computational tools essential for an RNA-Seq experiment.

| Item | Function | Example Tools / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA, crucial for samples with low mRNA integrity or bacterial RNA. | Ribo-Zero, NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit |

| Stranded cDNA Library Kit | Creates a sequencing library that preserves the original strand information of RNA, which is vital for identifying antisense transcripts. | Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit |

| Quality Control Tool | Assesses raw sequence data for quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences. | FastQC [6] [4], NGSQC [6], multiQC [4] |

| Trimming Tool | Removes low-quality bases and adapter sequences from raw sequencing reads. | Trimmomatic [6] [1], Cutadapt [1], fastp [4] |

| Alignment Tool | Maps sequenced reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. | STAR [4] [5], HISAT2 [4] |

| Quantification Tool | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript to generate expression values. | featureCounts [4], HTSeq-count [4], Kallisto [4], Salmon [4] [1] |

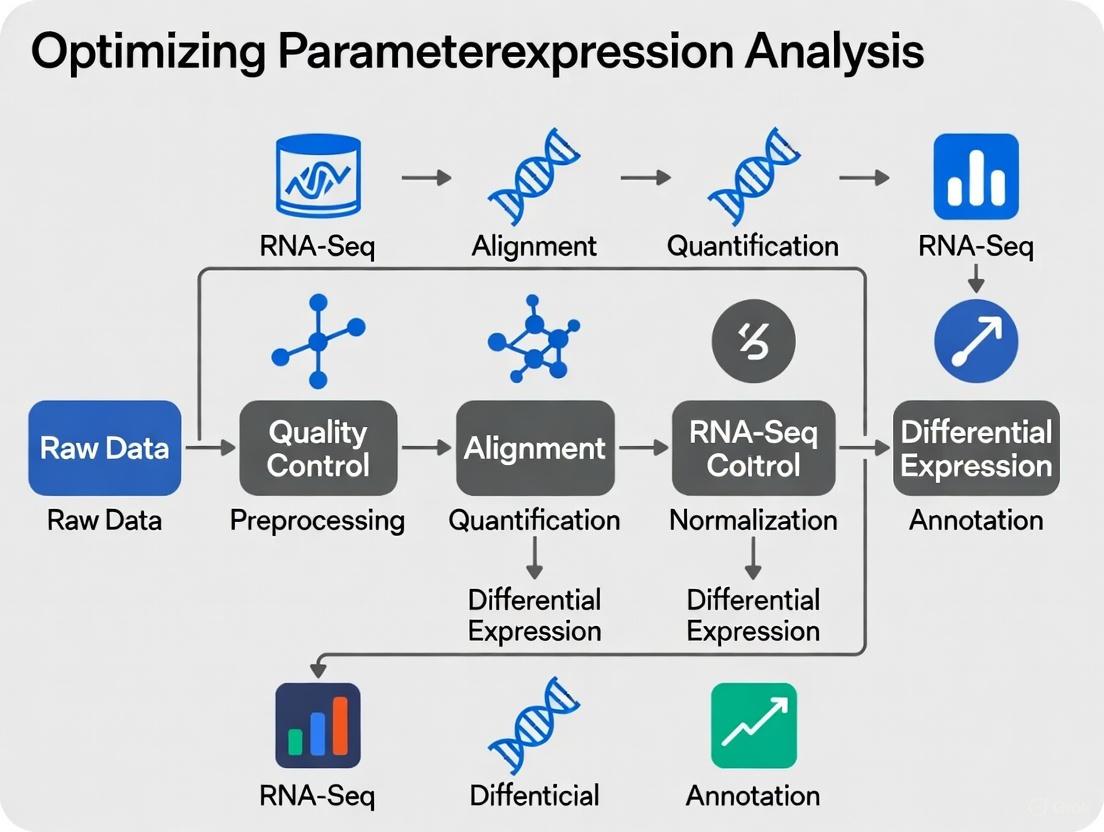

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core steps in an RNA-Seq data analysis pipeline, from raw data to functional interpretation, including key decision points and outputs.

Normalization Techniques for Read Counts

Normalization is critical for correcting biases that make counts from different samples non-comparable. The table below summarizes common techniques.

| Method | Principle | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Total Count (TC) | Scales counts by the total number of reads (library size) in each sample. | Simple but highly sensitive to a few highly expressed genes [4]. |

| Upper Quartile (UQ) | Uses the upper quartile of counts (non-zero genes) as a scaling factor. | More robust than TC, but performance can vary [1]. |

| Median of Ratios (DESeq2) | Estimates size factors based on the median of gene-wise ratios between sample and a pseudo-reference sample. | Robust to the presence of many differentially expressed genes [7]. |

| Trimmed Mean of M (TMM) | Uses a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios (M-values) between samples. | A widely used robust method, implemented in edgeR [7]. |

| Transcripts Per Million (TPM) | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length. | Suitable for within-sample comparisons of transcript isoforms [5]. |

A systematic assessment of normalization methods as part of a larger pipeline comparison found that methods like TMM and those used by DESeq2 performed well in generating accurate raw gene expression signals [1].

In RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) differential expression analysis, two fundamental technical uncertainties directly impact the reliability of your results: the uncertainty in read assignment (determining the genomic origin of each sequencing fragment) and the uncertainty in count estimation (quantifying gene expression levels from these assignments). These challenges are present in every RNA-Seq experiment, whether you're working with bulk or single-cell data, and they propagate through your analysis pipeline, potentially affecting downstream biological interpretations.

Read assignment uncertainty arises from factors such as ambiguous alignment of reads to multiple genomic locations, the presence of paralogous genes with similar sequences, and the challenges of accurately assigning reads to specific transcript isoforms. Count estimation uncertainty stems from technical variations in library preparation, sequencing depth, and normalization methods, which can obscure true biological differences [8] [9].

This guide addresses these challenges through practical troubleshooting advice and frequently asked questions, helping you optimize your experimental design and analytical approach for more robust differential expression results.

What is read assignment uncertainty and what causes it?

Read assignment uncertainty occurs when sequencing fragments could potentially align to multiple locations in the reference genome or be assigned to multiple genes or transcripts. This problem is particularly pronounced in several scenarios:

- Genes with paralogs or gene families: Sequence similarity between duplicated genes makes it difficult to uniquely assign reads [9]

- Alternative splicing events: Reads from shared exonic regions can belong to multiple different transcript isoforms

- Repetitive genomic regions: Areas with low-complexity sequences or transposable elements

- Incomplete genome annotation: Regions where gene boundaries or novel transcripts haven't been fully characterized

The practical consequence of this uncertainty is that some reads are "multimapped" and may be excluded from analysis or proportionally assigned, potentially skewing expression estimates for genes with homologous sequences.

What is count estimation uncertainty and what causes it?

Count estimation uncertainty refers to the technical variability in quantifying gene expression levels, even when read assignments are correct. Principal sources include:

- Library preparation biases: Systematic errors introduced during RNA extraction, amplification, or adapter ligation [8] [10]

- Sequencing depth variations: Differences in total read counts between samples affect detection sensitivity [11] [12]

- RNA composition effects: Varying proportions of RNA types between samples can skew results [13]

- GC content bias: Non-uniform amplification and sequencing efficiency based on nucleotide composition [12]

These technical variations mean that raw read counts alone do not perfectly represent true RNA abundance, necessitating appropriate normalization and statistical modeling to distinguish technical artifacts from biological signals.

Experimental Design to Minimize Uncertainty

How can I optimize my experimental design to address these uncertainties?

Strategic experimental design provides the most effective approach to mitigating technical uncertainties in RNA-Seq analysis:

Prioritize biological replication over sequencing depth: Multiple studies have demonstrated that increasing the number of biological replicates provides greater statistical power than increasing sequencing depth [11] [14] [12]. For most experiments, at least 4-6 biological replicates per condition provides a good balance between cost and statistical power [11] [14].

Utilize appropriate sequencing depth: While requirements vary by organism and research question, 20-30 million reads per sample typically provides sufficient coverage for most differential expression studies while allowing for more biological replicates within the same budget [11] [12].

Implement blocking designs: When processing large numbers of samples, distribute samples from all experimental groups across library preparation batches and sequencing lanes to avoid confounding technical and biological effects [8].

Include control RNAs or spike-ins: For specialized applications where global changes in transcript abundance are expected, spike-in RNAs can help normalize for technical variation and improve count estimation accuracy [14].

Table 1: Impact of Experimental Design Choices on Different Types of Genes

| Gene Expression Level | Recommended Biological Replicates | Recommended Library Size | Primary Uncertainty Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly expressed genes | 4+ replicates [11] | 10-20 million reads [12] | Count estimation |

| Lowly expressed genes | 6+ replicates [11] | 20-30 million reads [11] | Both read assignment and count estimation |

| Genes with paralogs | 4+ replicates [11] | 20-30 million reads [11] | Read assignment |

What is the optimal balance between replicates and sequencing depth?

The relationship between biological replicates and sequencing depth represents a fundamental trade-off in experimental design, particularly when working with fixed budgets. Based on comprehensive power analyses:

Table 2: Power Analysis for Differential Expression Detection [11] [14] [12]

| Biological Replicates | Minimum Library Size | Expected DE Genes Detected | False Discovery Rate Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 replicates | 20-30 million reads | ~60-70% with large effect sizes | Suboptimal (FDR > 10%) |

| 4-6 replicates | 20 million reads | ~80-90% with moderate effects | Good (FDR ~5-10%) |

| 7+ replicates | 15-20 million reads | >90% with small effects | Excellent (FDR < 5%) |

Strikingly, one study found that sequencing depth could be reduced to as low as 15% of the original depth without substantial impacts on false positive or true positive rates when sufficient biological replicates were used [12]. This highlights the critical importance of biological replication over excessive sequencing depth for differential expression analysis.

Computational Strategies to Address Uncertainty

How do I minimize read assignment uncertainty in my analysis?

Computational approaches can significantly reduce read assignment uncertainty:

Implement splice-aware aligners: Tools like STAR, HISAT2, or TopHat2 account for splice junctions when mapping reads across exon boundaries [8] [9]

Utilize transcript quantification methods: Pseudoalignment tools such as Salmon, kallisto, or RSEM can improve assignment accuracy by considering all possible transcript origins for each read [15]. These methods are particularly valuable for:

- Estimating transcript-level expression

- Correcting for changes in gene length across samples

- Handling fragments that align to multiple genes with homologous sequence [15]

Apply appropriate multimapping strategies: Rather than discussing multimapped reads, some pipelines probabilistically assign them to potential genomic origins, preserving more information from your sequencing data

Leverage comprehensive annotation: Use the most current and comprehensive annotation files for your organism, as incomplete annotation is a major source of assignment uncertainty

What normalization methods best address count estimation uncertainty?

Normalization is crucial for addressing count estimation uncertainty. The choice of method depends on your experimental context:

Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM): Implemented in edgeR, this method assumes most genes are not differentially expressed and scales libraries based on a subset of stable genes [14] [13]

Relative Log Expression (RLE): Used in DESeq2, this method calculates scaling factors based on the geometric mean of read counts across all samples [14] [13]

Transcript-aware normalization: When using transcript quantifiers like Salmon or kallisto, the tximport package can generate offset matrices that correct for changes in effective transcript length across samples [15]

For most standard differential expression analyses, TMM and RLE normalization perform similarly well [14]. However, in experiments with global transcriptomic changes (e.g., cell differentiation), spike-in based normalization may be necessary.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

How do I diagnose and address high read assignment ambiguity?

Problem: A high percentage of reads that multimap to multiple genomic locations, leading to uncertain gene assignments.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check alignment statistics for multimapping rates (typically reported by aligners like STAR)

- Identify whether problematic genes belong to paralogous families or repetitive regions

- Verify the quality and completeness of your reference genome annotation

Solutions:

- For genes with paralogs: Consider analyzing at the gene family level rather than individual gene level

- Implement a transcript-level analysis with tools that handle fractional read assignment [15]

- Filter out genes with consistently ambiguous assignment if they're not biologically relevant to your study

- Ensure you're using the most recent genome assembly with comprehensive annotation

How do I troubleshoot count estimation problems?

Problem: Unexpected patterns in sample clustering or high technical variation between replicates.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Examine PCA plots colored by technical factors (batch, sequencing lane) rather than biological groups

- Check for correlations between sequencing depth and variance estimates

- Verify that normalization factors are appropriately calculated and applied

Solutions:

- For batch effects: Include batch as a covariate in your statistical model [8] [15]

- For library size differences: Ensure you're using appropriate normalization methods (TMM or RLE) rather than simple library size scaling [13]

- For overdispersion: Use statistical methods like DESeq2 or edgeR that explicitly model overdispersion in count data [14] [15] [13]

- For composition biases: Consider using spike-in normalization if you have global expression changes [14]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Addressing RNA-Seq Uncertainties

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Uncertainty Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike-in RNA controls | Wet-bench reagent | Normalization for technical variation | Count estimation |

| UMI barcodes | Molecular biology | Distinguishing biological duplicates from PCR duplicates | Count estimation |

| Strand-specific library kits | Wet-bench reagent | Determining transcript strand orientation | Read assignment |

| Salmon/kallisto | Computational tool | Transcript quantification with bias correction | Both |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Computational tool | Differential expression analysis | Count estimation |

| tximport/tximeta | Computational tool | Importing transcript-level estimates | Both |

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol: Read Assignment Improvement with Pseudoalignment

Purpose: To improve read assignment accuracy using transcript-aware quantification tools.

Steps:

- Download and prepare reference transcriptome: Obtain FASTA files for your organism of interest

- Build transcriptome index: Using Salmon or kallisto's indexing function

- Quantify transcript abundances: Run quantification directly from FASTQ files (skipping alignment)

- Import to differential expression framework: Use tximport in R to create gene-level count matrices with appropriate offsets

- Proceed with standard DE analysis: Using DESeq2 or edgeR with the imported counts

Key Parameters:

- For Salmon: Use

--gcBiasand--seqBiasflags to correct for systematic biases [15] - For kallisto: Specify appropriate fragment length and standard deviation for single-end data

- For tximport: Set

countsFromAbundance = "lengthScaledTPM"for gene-level summarization

Advantages: This approach corrects for potential changes in gene length across samples, increases sensitivity by considering multimapping reads, and typically requires less computational resources than traditional alignment [15].

Protocol: Count Estimation Validation

Purpose: To validate count estimation accuracy and identify potential technical artifacts.

Steps:

- Generate diagnostic plots:

- PCA plot colored by biological and technical factors

- Sample-to-sample distance heatmap

- Distribution of log fold changes across all genes

- Check normalization factors: Verify that size factors in DESeq2 or normalization factors in edgeR are within expected ranges (typically 0.5-2.0)

- Assess dispersion estimates: Plot dispersion estimates against mean expression to ensure proper modeling

- Validate with positive controls: If available, check expression patterns of genes expected to be differentially expressed based on prior knowledge

Interpretation:

- Strong batch effects in PCA: Include batch in design formula

- Extreme normalization factors: Investigate potential sample-specific issues

- Poor dispersion fit: Consider alternative analysis methods or filtering

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I use gene-level or transcript-level analysis for my experiment?

Answer: The choice depends on your biological question and the quality of your reference annotation:

Use gene-level analysis when:

- Your primary interest is in overall gene expression changes rather than isoform usage

- Working with organisms with incomplete transcriptome annotation

- Seeking more robust and reproducible results (gene-level counts typically have less uncertainty)

Use transcript-level analysis when:

- Studying biological processes known to involve alternative splicing

- Working with well-annotated model organisms

- Willing to accept higher uncertainty in exchange for isoform-resolution insights

For most differential expression studies, gene-level analysis provides a good balance between biological insight and technical robustness. If you choose transcript-level analysis, be sure to use methods like those implemented in DESeq2 or edgeR that can handle the increased statistical uncertainty [15].

How many biological replicates do I really need for my RNA-Seq experiment?

Answer: The optimal number of replicates depends on several factors:

- For pilot studies or when expecting large effect sizes: 3-4 biological replicates per condition may be sufficient

- For standard differential expression studies: 5-6 replicates provide good power to detect moderate effect sizes while controlling false discovery rates [11] [14]

- For detecting subtle expression changes (<1.5-fold): 7+ replicates are often necessary

If you have prior RNA-Seq data from similar experiments, tools like DESeq2's estimateSizeFactors and estimateDispersions can help perform power calculations for your specific experimental context. When in doubt, err on the side of more biological replicates rather than deeper sequencing [11] [12].

What quality control metrics specifically indicate problems with read assignment or count estimation?

Answer: Key quality metrics to monitor include:

For read assignment problems:

- Low alignment rates (<70-80% of reads mapping to the reference)

- High percentages of multimapping reads (>10-20%)

- Uneven coverage across transcript bodies

- Systematic differences in these metrics between experimental groups

For count estimation problems:

- Extreme library size differences between samples (>2-fold)

- Poor correlation between technical replicates

- Batch effects visible in PCA plots that correlate with processing date rather than biology

- Abnormal distribution of fold changes (not centered around zero for null comparisons)

Most RNA-Seq analysis pipelines provide these metrics, and tools like MultiQC can help aggregate them across multiple samples for easier identification of problematic samples.

In the context of optimizing parameters for RNA-Seq differential expression analysis, the hybrid approach combining STAR alignment with Salmon quantification leverages the respective strengths of both tools. STAR provides sensitive and accurate splice-aware alignment to the genome, while Salmon uses these alignments for fast, bias-aware transcript quantification [16] [17]. This method is particularly valuable when your research aims include both novel splice junction discovery and highly accurate transcript-level expression estimates for downstream differential expression testing.

The following workflow illustrates the complete process, from raw sequencing reads to a quantified transcriptome, highlighting the integration points between STAR and Salmon.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: RNA-seq Read Preprocessing and Alignment with STAR

Proper preparation of sequencing reads is a critical first step to ensure high-quality alignment and quantification [18] [19].

1. Quality Control and Trimming

- Tool: FastQC for quality control, followed by Cutadapt for trimming [18].

- Command Example:

2. Genome Alignment with STAR

- Objective: Generate a BAM file containing reads aligned to the reference genome, which will be used by Salmon.

- STAR Command Example [18]:

Protocol 2: Transcript Quantification with Salmon (Alignment-Based Mode)

This protocol uses the BAM file from STAR for transcript-level quantification.

1. Prepare Transcriptome and Decoy File

- Obtain the transcriptome sequences (FASTA) and annotation (GTF) for your organism.

- Building a decoy-aware transcriptome is recommended to reduce spurious mapping of reads from unannotated genomic loci [20] [21]. Scripts like

generateDecoyTranscriptome.shcan automate this process.

2. Run Salmon Quantification

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: STAR alignment produces a very small BAM file. What could be wrong?

- A: This often indicates a fundamental issue preventing successful alignment.

- Verify Reference Genome: Ensure you are using the correct genome build and version for your species.

- Check Read Files: Confirm the paths to your input FASTQ files are correct and the files are not corrupted.

- Inspect Log File: STAR generates a detailed log file. Look for error messages or warnings.

- Check Quality Metrics: Use FastQC to ensure your reads are of sufficient quality and do not originate from a different species or are heavily contaminated.

- Output Unmapped Reads: Run STAR with

--outReadsUnmapped Fastxto output the unmapped reads and investigate them further [23].

Q2: Should I use the same reference genome for both STAR and Salmon?

- A: The references are related but different.

- STAR requires a reference genome (e.g.,

genome.fa) and often a gene annotation file (GTF) to build its index. - Salmon requires a transcriptome file (e.g.,

transcripts.fa), which is a FASTA file of all known transcript sequences. This can typically be generated from the same GTF file used for STAR.

- STAR requires a reference genome (e.g.,

Q3: Why are my transcript abundance estimates from Salmon inconsistent or inaccurate?

- A: This can stem from several factors related to the input data and parameters.

- Enable ValidateMappings: Always use the

--validateMappingsflag for more accurate and sensitive mapping during quantification [20] [21]. - Use a Decoy-aware Transcriptome: This prevents mis-mapping of reads that originate from non-transcribed regions and improves accuracy [20].

- Check Library Type: Incorrectly specifying the library type (e.g., stranded vs. unstranded) with the

-lparameter is a common source of error. Use tools likeSalmon quant -l Afor auto-detection or consult your library preparation protocol [22]. - RNA Integrity: Starting with high-quality RNA (RIN > 6) is crucial, as degraded RNA can lead to 3' bias and inaccurate quantification [19].

- Enable ValidateMappings: Always use the

Q4: When is this hybrid approach particularly advantageous over using either tool alone?

- A: The hybrid approach is recommended when your analysis has dual objectives [16]. The table below summarizes the strengths of each tool and the hybrid approach.

| Tool / Approach | Primary Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Alone | Sensitive alignment to the genome; novel splice junction discovery [16]. | Analyses requiring detection of novel isoforms, fusion genes, or genomic variation. |

| Salmon Alone (quasi-mapping) | Extremely fast transcript quantification directly from reads [16] [17]. | Large-scale studies where speed is critical and a well-annotated transcriptome exists. |

| STAR + Salmon (Hybrid) | Leverages STAR's alignment sensitivity and Salmon's bias-aware accurate quantification [16] [17]. | Optimal for differential expression analysis, especially when seeking a balance between novel feature discovery and quantification precision. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, software, and data resources required to implement the STAR+Salmon hybrid workflow.

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Sequence of the organism's genome for read alignment. | ENSEMBL, UCSC Genome Browser, NCBI. |

| Gene Annotation (GTF/GFF) | File containing genomic coordinates of genes, transcripts, and exons. | ENSEMBL, GENCODE (for human/mouse). |

| Transcriptome (FASTA) | Sequence file of all known transcripts for quantification. | Can be generated from the GTF and genome FASTA. |

| STAR Aligner | Software for splicing-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads to the genome [18]. | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| Salmon | Software for fast, bias-aware transcript quantification from alignments or reads [20] [17]. | https://github.com/COMBINE-lab/salmon |

| FastQC | Quality control tool for high-throughput sequence data [18]. | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| Cutadapt | Tool to find and remove adapter sequences, primers, and other unwanted sequences from reads [18]. | https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/ |

| High-Quality RNA | Input biological material. Integrity is critical for success (RIN > 6 recommended) [19]. | Extracted from tissue/cells using appropriate kits. |

| Conda/Bioconda | Package manager for easy installation of bioinformatics software like Salmon and STAR [18] [22]. | https://docs.conda.io/ |

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for troubleshooting the most common issues encountered during the alignment and quantification steps.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Biological Replicates

Q: What is the fundamental difference between biological and technical replicates? A: Biological replicates and technical replicates serve distinct purposes in experimental design:

- Biological Replicates: These are different biological specimens measured independently (e.g., three different mice from the same strain undergoing the same treatment). They account for the natural biological variation within a population [24] [25].

- Technical Replicates: These involve multiple measurements of the same biological specimen (e.g., taking the same RNA sample and processing it through three separate real-time PCR reactions). They primarily help assess measurement error or technical variability introduced by the experimental procedure itself [24] [25].

Q: Why are biological replicates considered non-negotiable in a robust RNA-Seq experimental design? A: Biological replicates are essential for several critical reasons [24] [25]:

- Estimation of Biological Variance: They allow researchers to measure the natural variation in gene expression that exists between individuals in a population. Without this, it is impossible to determine if an observed difference is due to the experimental condition or merely individual variation.

- Enhanced Statistical Power: Increasing the number of biological replicates strengthens the statistical power of differential expression analysis, making it more likely to detect true positive effects.

- Outlier Detection: They enable the identification of anomalous samples that might skew results. By calculating correlations between replicates, problematic samples can be identified and removed.

- Generalizable Conclusions: Results derived from multiple biological replicates are more likely to represent the true biological phenomenon in the broader population, rather than being an artifact of a single individual.

Q: How many biological replicates should I use for my RNA-Seq experiment? A: While more replicates are always better, practical constraints like cost must be considered. Here are the general guidelines [24] [25]:

- Minimum Recommendation: At least 3 biological replicates per condition is the widely accepted minimum for RNA-Seq experiments.

- Avoiding Two Replicates: Using only two replicates is generally discouraged. If the two results are inconsistent, there is no way to determine which one is reliable.

- Publication Standards: Experiments without biological replicates face significant challenges in publication, particularly in journals with an Impact Factor of 5 or higher.

Table 1: Recommended Number of Biological Replicates for Different Organisms

| Organism Type | Minimum Recommended Replicates | Notes on Biological Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotes & Fungi | 3 | Generally lower individual variability, leading to higher correlation between replicates [24] |

| Plants | 3 | Moderate variability; requires strict control over growth conditions and morphology during sampling [24] |

| Animals | 3 or more | Higher individual variability; requires strict control over genetic background, age, sex, and rearing conditions [24] |

Q: Can I pool multiple biological samples into one sequencing run instead of running them as individual replicates? A: No. Pooling multiple biological samples (e.g., mixing RNA from three individuals) and sequencing them as a single sample is not a substitute for proper biological replication [24] [25]. This practice only provides an average expression value for the group and destroys all information about inter-individual variation. Consequently, you lose the ability to perform statistical tests for differential expression, and the results cannot be generalized to the population.

Q: What are the critical factors for selecting appropriate biological replicates? A: To ensure that your replicates truly measure biological variance related to your experiment, you must control for other sources of variation. The following table outlines key criteria [24] [25]:

Table 2: Sampling Requirements for High-Quality Biological Replicates

| Organism | Key Controlled Variables |

|---|---|

| Plants | Same field/plot, uniform growth, identical external morphology, same developmental stage [24] |

| Animals | Identical genetic background, same rearing conditions, same age, same sex, uniform external morphology [24] |

| Cell Cultures | Same passage number, identical culture conditions, harvested at the same confluence [25] |

Sequencing Depth and Data Analysis

Q: What are the essential steps in a standard RNA-Seq data analysis workflow? A: A typical RNA-Seq data analysis involves a series of sequential steps, from raw data to biological interpretation. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow

1. Raw Data Acquisition: Download sequencing data (in SRA format) from public repositories like NCBI GEO using tools like prefetch and fasterq-dump/fastq-dump [26] [27].

2. Quality Control (QC): Assess the quality of the raw sequence files (FASTQ) using FastQC. This checks for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content, etc. MultiQC can summarize results from multiple samples [26] [28] [27].

3. Read Trimming/Filtering: Remove low-quality bases, adapter sequences, and other artifacts using tools like fastp, Trimmomatic, or trim_galore based on the QC report [26] [28].

4. Alignment to Reference Genome: Map the high-quality reads to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as HISAT2 (commonly used) or STAR [26] [28] [27].

5. Quantification of Gene/Transcript Expression: Generate count matrices (the number of reads mapped to each gene) using StringTie + Ballgown or featureCounts. These raw counts are the primary input for differential expression analysis. Normalized expression values like FPKM, RPKM, or TPM can also be calculated for within-sample comparisons [26] [28].

6. Differential Expression Analysis: Identify genes that are statistically significantly expressed between conditions using specialized R/Bioconductor packages like DESeq2, edgeR, or limma [26] [28].

7. Downstream Analysis: Interpret the biological meaning of the differentially expressed genes through functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) using tools like clusterProfiler or GSEA [26] [28].

Q: What are the key quantification metrics for gene expression, and how do they differ? A: Expression levels can be normalized in different ways to account for technical biases. The table below compares common metrics [29] [26]:

Table 3: Common Gene Expression Quantification Metrics in RNA-Seq

| Metric | Full Name | Formula / Principle | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | - | Raw number of reads mapping to a gene/transcript. | The direct input for most statistical differential expression tools (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR). |

| CPM | Counts Per Million | (Count / Total Counts) * 10^6 | Simple normalization for total library size, useful for within-sample comparisons. Does not account for gene length. |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads | (Count / (Gene Length/1000 * Total Counts/10^6)) | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length. Suitable for comparing expression of different genes within the same sample. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | (Count / (Gene Length/1000)) then normalized to per million. | Similar to FPKM but with a different calculation order. Considered more stable for cross-sample comparisons [28]. |

Q: What tools and reagents are essential for a successful RNA-Seq experiment and analysis? A: The following toolkit is critical for generating and processing RNA-Seq data:

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit for RNA-Seq Research

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | RiboMinus Kit / rRNA Depletion Probes | Removal of abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA [27]. |

| SOLiD / Illumina Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from RNA samples [27] [30]. | |

| QC & Preprocessing | FastQC, MultiQC | Quality control assessment of raw and processed sequencing data [26] [28]. |

| Trimmomatic, fastp | Trimming of adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads [26] [28]. | |

| Alignment | HISAT2, STAR | Splice-aware alignment of RNA-Seq reads to a reference genome [26] [28] [27]. |

| Quantification | StringTie, featureCounts | Assembly of transcripts and generation of raw count matrices [26] [27]. |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma (R/Bioconductor) | Statistical identification of differentially expressed genes [26] [28]. |

| Functional Analysis | clusterProfiler, GSEA, DAVID | Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway (KEGG) enrichment analysis [26] [28]. |

Advanced Applications and Protocols

Q: How does single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) differ from bulk RNA-Seq in its experimental design and application? A: Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a major technological shift with distinct design considerations, particularly in the context of complex systems like the tumor microenvironment (TME) [31].

- Objective: While bulk RNA-seq profiles the average gene expression of a population of cells, scRNA-seq measures the transcriptome of individual cells. This allows for the dissection of cellular heterogeneity, identification of rare cell types, and characterization of novel cell states and trajectories [31].

- Application Example: In lung cancer research, scRNA-seq has been used to:

- Discover new malignant cell subpopulations (e.g., TM4SF1+/SCGB3A2+ cells) and immune cell subsets [31].

- Reveal specific cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) subsets that correlate with poor prognosis [31].

- Analyze cell-cell communication networks using tools like CellPhoneDB and CellChat to understand mechanisms of immune suppression and therapy resistance [31].

- Design Implication: The unit of biological replication shifts from a tissue sample to an individual cell. However, technical replicates (multiple libraries from the same cell pool) and biological replicates (samples from different individuals or conditions) remain crucial for validating findings. High cell numbers (thousands per sample) are often needed to adequately capture population diversity.

Q: Can you outline a generalized experimental protocol for an RNA-Seq study? A: The following diagram and steps summarize a general protocol, adaptable from a non-model organism study [30]:

General RNA-Seq Experimental Protocol

1. Define Experimental Groups and Apply Treatment: Establish clear control and experimental groups (e.g., short-day vs. long-day photoperiod to induce diapause). Ensure adequate biological replication (n>=3 per group) from the outset [30] [32]. 2. Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect tissues or whole organisms under standardized conditions. Immediately stabilize RNA by flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen or using preservative solutions like RNAlater [30]. 3. RNA Extraction and Quality Assessment: Extract total RNA using reliable kits (e.g., phenol-chloroform based). Assess RNA integrity and purity using instruments like the Bioanalyzer; an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.0 is often recommended for high-quality libraries [30]. 4. Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use a standardized protocol, for example: - Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich for polyadenylated mRNA. - Fragment RNA and synthesize cDNA. - Add sequencing adapters and amplify the library. - Perform quality control on the final library before sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) to a sufficient depth (e.g., 20-40 million reads per sample for standard bulk RNA-Seq) [27] [30]. 5. Bioinformatic Analysis: Follow the workflow outlined in the previous section, from QC to differential expression and enrichment analysis [26] [28].

By adhering to these fundamental principles of experimental design—incorporating sufficient biological replicates, understanding sequencing depth needs, and following a robust analytical workflow—researchers can generate reliable, statistically sound, and biologically meaningful RNA-Seq data.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a state-of-the-art method for quantifying gene expression and performing differential expression analysis at high resolution. A number of factors influence gene quantification in RNA-seq, such as sequencing depth, gene length, RNA composition, and sample-to-sample variability [33]. Normalization is the essential process that adjusts raw transcriptomic data to account for these technical factors, ensuring that differences in normalized read counts accurately represent true biological expression rather than technical artifacts [34]. Without proper normalization, researchers risk drawing incorrect biological conclusions due to technical biases inherent in the sequencing process [35].

This guide provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers navigating the complexities of RNA-seq normalization. Within the broader context of optimizing parameters for differential expression analysis, we compare method assumptions, applications, and limitations through structured comparisons, troubleshooting guides, and practical protocols to support robust experimental design and analysis.

Core Normalization Methods

Table 1: Core Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Normalization Factors | Primary Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM/RPM | Counts/Reads Per Million | Sequencing depth | Sequencing protocols where read count is independent of gene length [33] | Simple, intuitive calculation [36] | Does not account for gene length [36] |

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads | Gene length & sequencing depth | Within-sample comparisons in single-end (RPKM) or paired-end (FPKM) experiments [33] | Enables comparison of expression levels within a sample [34] | Not recommended for between-sample comparisons; sum of normalized counts varies between samples [33] [37] |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Gene length & sequencing depth | Within-sample comparisons with improved between-sample comparability [33] | Constant sum across samples facilitates proportion-based comparisons [37] [38] | Still affected by RNA composition differences between samples [38] |

Table 2: Advanced Between-Sample Normalization Methods for Differential Expression

| Method | Full Name | Normalization Approach | Key Assumptions | Best For | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Between-sample scaling using a reference sample [34] | Most genes are not differentially expressed [36] | Datasets with different RNA compositions or containing highly expressed genes [36] | edgeR package [39] |

| RLE/DESeq2 | Relative Log Expression | Between-sample scaling based on geometric means [39] | Most genes are not differentially expressed [36] | Datasets with substantial library size differences or where some genes are only expressed in subsets [36] | DESeq2 package [39] |

| Quantile | Quantile Normalization | Makes expression distributions identical across samples [36] | Observed distribution differences are primarily technical [36] | Complex experimental designs with multiple samples; reduces technical variation [36] | Limma-Voom package [36] |

Choosing the Right Normalization Method

The selection of an appropriate normalization method depends on your experimental design and research questions. For within-sample comparisons (comparing expression of different genes within the same sample), RPKM/FPKM or TPM are appropriate as they account for gene length differences [33] [34]. For between-sample comparisons (comparing the same gene across different samples) or differential expression analysis, more advanced between-sample normalization methods like TMM (edgeR) or RLE (DESeq2) are recommended [33] [34]. When integrating multiple datasets, batch correction methods like ComBat or Limma should be applied to remove technical artifacts introduced by different sequencing runs or facilities [34].

Troubleshooting Common Normalization Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't I directly compare RPKM/FPKM or TPM values across different samples or studies?

While RPKM/FPKM and TPM are normalized units, they represent the relative abundance of a transcript within the specific population of sequenced RNAs in each sample [38]. When sample preparation protocols or RNA populations differ significantly between samples (e.g., poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion), the proportion of gene expression is not directly comparable [38]. For example, in samples prepared with rRNA depletion, small RNAs may dominate the sequencing library, artificially deflating the TPM values of protein-coding genes compared to the same sample prepared with poly(A)+ selection [38].

What should I do when my negative controls indicate significant batch effects after normalization?

Batch effects often account for the greatest source of differential expression when combining data from multiple experiments [34]. When significant batch effects persist after standard normalization:

- Apply dedicated batch correction methods such as ComBat or Limma, which use empirical Bayes statistics to adjust for known batch variables (e.g., sequencing center, date) [34].

- Perform surrogate variable analysis (sva) to identify and estimate unknown sources of variation [34].

- Ensure proper experimental design by including technical replicates and randomizing samples across sequencing batches when possible.

How does transcriptome size variation impact single-cell RNA-seq normalization and how should I address it?

In single-cell RNA-seq, cells of different types have significantly different "true" transcriptome sizes (total mRNA molecules per cell) [40]. Standard normalization methods like CP10K (counts per 10,000) assume constant transcriptome size across all cells, which removes biological variation in total mRNA content [40]. This scaling effect causes problems when comparing different cell types or using scRNA-seq data as a reference for bulk RNA-seq deconvolution [40]. To address this, consider:

- Using specialized methods like CLTS (Count based on Linearized Transcriptome Size) that preserve transcriptome size variation [40].

- Being cautious when using CP10K-normalized scRNA-seq data as reference for bulk deconvolution, as it may lead to underestimation of rare cell type proportions [40].

What are the implications of having a large proportion of differentially expressed genes between my conditions?

Many between-sample normalization methods, including TMM and DESeq2, assume that most genes are not differentially expressed [36]. When this assumption is violated:

- TMM normalization may perform poorly as the trimming process could remove too many genes [36].

- Consider using quantile normalization or non-parametric methods that make fewer assumptions about the distribution of differentially expressed genes [36].

- Evaluate the use of spike-in controls as external standards for normalization [35].

Why am I getting different results when using the same data normalized with different methods?

Different normalization methods rely on different statistical approaches and assumptions, which can lead to varying results, particularly for low-count genes or genes with extreme expression values [41] [42]. To address this:

- Understand the assumptions of each method in relation to your data [35].

- Perform sensitivity analyses by testing multiple appropriate normalization methods and comparing consistent findings.

- Validate key results using alternative experimental approaches like qPCR for critical genes [42].

Experimental Protocols for Normalization Assessment

Protocol 1: Systematic Evaluation of Normalization Methods

This protocol is adapted from Abrams et al. (2019) for evaluating normalization efficacy in preserving biological signal while reducing technical noise [42].

Materials Needed:

- RNA-seq count matrix from a standardized dataset with known biological groups and technical replicates

- Computational environment with R/Bioconductor and appropriate normalization packages (edgeR, DESeq2, etc.)

- qPCR validation data for selected genes (optional but recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load your count matrix and ensure proper sample annotation including biological groups and technical batches.

- Normalization Application: Apply multiple normalization methods to your dataset (CPM, TPM, TMM, RLE, Quantile, etc.).

- Variance Decomposition: For each normalized dataset, perform ANOVA to decompose variability into:

- Biological variability (attributable to experimental conditions)

- Technical variability (attributable to sequencing site/batch)

- Residual variability (unexplained noise)

- Linearity Validation: Select genes with known linear relationships (e.g., from mixture designs) and verify that normalization preserves these expected linear relationships.

- Result Interpretation: Compare the proportion of biological variability retained by each method, prioritizing methods that maximize biological signal while minimizing residual noise.

Expected Outcomes: A successful normalization method should increase the proportion of variability attributable to biology compared to raw data while maintaining expected linear relationships between samples [42]. Based on systematic evaluations, TPM often performs well by increasing biological variability from 41% (raw) to 43% while reducing residual variability from 17% to 12% [42].

Protocol 2: Assessing Impact of Normalization on Differential Expression

This protocol evaluates how normalization choices affect differential expression results.

Materials Needed:

- RNA-seq count data from at least two biological conditions with replicates

- R/Bioconductor with edgeR, DESeq2, and limma packages

- Benchmark set of known differentially expressed genes (optional)

Procedure:

- Multiple Normalizations: Apply TMM, RLE, and TPM normalization to your count data.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform DE analysis using each normalized dataset with corresponding statistical methods (edgeR for TMM, DESeq2 for RLE).

- Result Comparison: Compare the lists of significantly differentially expressed genes identified by each method, noting:

- Consistency in top differentially expressed genes

- Variation in false discovery rates

- Sensitivity to outliers or highly expressed genes

- Method Validation: If available, compare results to qPCR validation data or known benchmark genes to assess accuracy.

Troubleshooting Notes: Substantial discrepancies between methods often indicate violations of methodological assumptions [35]. If results vary dramatically, investigate whether your data contains extensive global expression shifts or a high proportion of differentially expressed genes, which may require specialized normalization approaches [35].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Reagents | Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Poly(A)+ RNA selection | Enriches for mRNA by selecting polyadenylated transcripts [38] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Alternative to poly(A)+ selection; preserves non-polyadenylated transcripts [38] | |

| Spike-in Control RNAs | External RNA controls | Provides known quantities of exogenous transcripts for normalization quality control [35] | |

| Software Packages | edgeR (R/Bioconductor) | TMM normalization & differential expression | Implements TMM normalization for RNA-seq data [39] |

| DESeq2 (R/Bioconductor) | RLE normalization & differential expression | Implements median ratio normalization for DE analysis [39] | |

| Limma (R/Bioconductor) | Quantile normalization & linear modeling | Provides quantile normalization and batch correction methods [34] | |

| Reference Data | SEQC/MAQC-III Dataset | Standardized reference data | Large-scale benchmark dataset for normalization method evaluation [42] |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

As RNA-seq technologies evolve, normalization methods continue to improve. Emerging approaches include:

- Beta-Poisson Normalization: Initially designed for single-cell RNA-seq, this model-based method considers both technical noise and biological variability [36].

- SCnorm: Addresses the varying dependencies of counts on sequencing depth across different genes by estimating scale factors separately for groups of genes with similar dependence patterns [36].

- Machine Learning-Based Methods: Deep learning architectures like autoencoders show promise for learning data transformations that normalize technical variation while preserving biological information [36].

When working with specialized RNA-seq applications such as single-cell sequencing or isoform-level analysis, consult method-specific best practices and consider these emerging normalization approaches that address the unique characteristics of these data types.

Selecting Differential Expression Tools: Performance Comparisons and Best Use Cases

This technical support guide provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis and troubleshooting resource for researchers performing differential expression (DE) analysis with RNA-Seq data. Within the broader context of optimizing parameters for RNA-Seq research, we evaluate four popular tools: DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom, and EBSeq. Each tool employs distinct statistical approaches for addressing common challenges in RNA-Seq data, including overdispersion, small sample sizes, and varying library sizes. This guide synthesizes performance characteristics based on published studies and community experiences to help you select appropriate tools and troubleshoot common issues during experimental analysis. The FAQuantitative benchmarking reveals that proper tool selection and parameter optimization significantly impact detection power and false discovery rate control, making this guidance essential for robust differential expression analysis.

Tool Comparison & Performance Benchmarking

Statistical Foundations and Ideal Use Cases

Table 1: Core Methodologies and Performance Characteristics of DE Tools

| Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma-voom | EBSeq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation of log-CPM values | Bayesian modeling with posterior probabilities for DE |

| Default Normalization | Median ratio (RLE) | Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Weighted log-CPM transformation (voom) | GetNormalizedMat() function |

| Variance Handling | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion and fold changes | Common, trended, or tagwise dispersion options | Precision weights unlock linear models | Models across-condition vs within-condition variability |

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs better with more [43] | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples [43] | ≥3 replicates per condition [43] | Not specified in results |

| Best Use Cases | Moderate to large samples, high biological variability, strong FDR control [43] | Very small sample sizes, large datasets, technical replicates [43] | Multi-factor experiments, time-series, complex designs [44] [43] | Genes with large within-condition variation [45] |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be intensive for large datasets [43] | Highly efficient, fast processing [43] | Very efficient, scales well with large datasets [43] | Not specified in results |

| Special Features | Automatic outlier detection, independent filtering, visualization tools [43] | Multiple testing strategies, quasi-likelihood options, fast exact tests [43] | Handles complex designs elegantly, integrates with other omics [44] [43] | Provides posterior probabilities for DE (PPDE), less extreme FC estimates for low expressers [45] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Normalization and Statistical Test Performance Across Conditions

| Normalization Method | Statistical Test | Recommended Sample Size | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| UQ-pgQ2 | Exact test (edgeR) | Small samples | Better power and specificity, controls false positives [46] |

| UQ-pgQ2 | QL F-test (edgeR) | Large samples (n=5,10,15) | Better type I error control in intra-group analysis [46] |

| RLE (DESeq2) | Wald test (DESeq2) | Large sample sizes | Better performance than exact test with large replicates [46] |

| TMM (edgeR) | QL F-test (edgeR) | Any sample size | Best performance across sample sizes for any normalization [46] |

| RLE/TMM/UQ | Various | Varies | Similar performance given desired sample size [46] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Experimental Design and Setup

FAQ: How many biological replicates and what sequencing depth do I need for adequate power?

The number of biological replicates has a larger impact on detection power than library size, except for low-expressed genes where both parameters are equally important [11]. For a standard experiment, we recommend at least four biological replicates per condition and 20 million reads per sample to confidently detect approximately 1000 differentially expressed genes if they exist [11]. For studies with limited resources, edgeR performs reasonably well with only two replicates, while DESeq2 and limma-voom benefit from three or more replicates [43].

Troubleshooting Guide: No DE genes found in analysis

If your analysis returns zero differentially expressed genes despite expecting biological differences:

- Check statistical power: Ensure you have sufficient biological replicates. With small sample sizes, true differences may not reach statistical significance [47]. Consider using edgeR with its exact test or quasi-likelihood F-test for better performance with limited replicates [46] [43].

- Verify experimental design: When comparing multiple groups (e.g., before/after treatment vs. control), include all samples in a single analysis with a properly specified design matrix rather than analyzing subsets separately [47].

- Adjust significance thresholds: Relax adjusted p-value and fold change thresholds initially to check if any genes approach significance, then investigate why effect sizes might be smaller than expected.

- Confirm data integrity: Check that sample groupings and metadata are correctly specified in your analysis code.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

FAQ: How should I filter low-expressed genes?

Filtering low-expressed genes improves detection power by reducing multiple testing burden and focusing on biologically meaningful signals. For limma-voom, keep genes expressed in at least 80% of samples with a count per million (CPM) cutoff of 1 [44] [43]. EBSeq employs an automatic filter, excluding genes with more than 75% of values below 10 by default to ensure better model fitting [45]. You can disable this filter in EBSeq by setting Qtrm=1 and QtrmCut=0 if you need to retain low-count genes [45].

Troubleshooting Guide: Input file errors with DESeq2

When DESeq2 reports errors about "repeated input file" or "different number of rows":

- Verify replicate structure: DESeq2 and most DE tools require biological replicates and cannot run with only one sample per condition [48].

- Check feature consistency: Ensure all count files have the same number of rows (genes) in the same order. This indicates whether the same reference annotation was used for all samples [48].

- Validate upstream analysis: If counts have different numbers of features, review your alignment and quantification steps (e.g., featureCounts, HTSeq) to ensure consistency in reference annotations [48].

- Inspect data manipulation: Avoid modifying count files after generation, as this can introduce inconsistencies [48].

Tool-Specific Issues

FAQ: Why does EBSeq assign high PPDE to genes with small fold changes, and vice versa?

EBSeq calls a gene as differentially expressed (assigning high posterior probability of DE or PPDE) when across-condition variability is significantly larger than within-condition variability. A gene with large fold change might not be called DE if it also has large biological variation within conditions, as this variation could explain the across-condition difference [45]. Conversely, genes with smaller fold changes but consistent patterns across replicates may receive higher PPDE values.

FAQ: Can I use TPM/FPKM/RPKM values directly for differential expression analysis?

No, cross-sample comparisons using TPM, FPKM, or RPKM without further normalization is generally not appropriate [45]. These normalized values assume symmetric distribution of differentially expressed genes across samples, which rarely holds true in real experiments. Instead, use raw counts with library size factors or normalized counts from tool-specific functions like GetNormalizedMat() in EBSeq [45].

Troubleshooting Guide: NA values in EBSeq posterior probabilities

If your EBSeq results show "NoTest" status with NA values for posterior probabilities:

- Check default filters: EBSeq excludes genes with >75% of values <10 by default. Adjust with

Qtrm=1andQtrmCut=0parameters to disable this filter [45]. - Address numerical overflow: For genes with extremely large or small within-condition variance, numerical issues can occur. Try adjusting the

ApproxValparameter inEBTest()orEBMultiTest()(default is 10^-10) [45]. - Verify input data: Ensure count data contains appropriate variability and no extreme outliers that could cause computational issues.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Comprehensive RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis Workflow

Tool Selection Decision Guide

Diagram 2: Differential Expression Tool Selection Guide

Detailed DESeq2 Protocol

Methodology for DESeq2 Analysis:

- Data Preparation: Create a count matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns, plus a metadata table with sample information.

- Create DESeq2 Object:

- Pre-filtering: Remove genes with very low counts (e.g., <10 reads across all samples).

- Specify Reference Level:

- Run DESeq Analysis:

- Extract Results:

Detailed edgeR Protocol with QL F-test

Methodology for edgeR Quasi-Likelihood Analysis:

- Create DGEList Object:

- Normalization: Calculate normalization factors using TMM method

- Filter low-expressed genes:

- Design Matrix and Dispersion Estimation:

- QL Framework:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastP, TrimGalore, Trimmomatic | Adapter trimming, quality filtering | FastP offers speed and simplicity; TrimGalore provides integrated QC reports [9] |

| Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 | Read alignment to reference genome | STAR provides high accuracy; HISAT2 is efficient for spliced alignment [46] |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq, RSEM | Generate count matrices from aligned reads | featureCounts is fast and efficient; RSEM estimates transcript abundances [46] [9] |

| DE Analysis | DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom, EBSeq | Identify differentially expressed genes | Choice depends on experimental design, sample size, and biological question [43] |

| Functional Analysis | GO enrichment, GSEA | Biological interpretation of DE results | Provides pathway analysis and functional annotation of results [11] |

Normalization Methods Reference

Table 4: Comparison of RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Description | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) | Median-based method in DESeq2 | Performs well with moderate to large sample sizes | Can be conservative with small samples [46] |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Weighted trimmed mean in edgeR | Robust to highly differentially expressed genes | Can be too liberal with some data types [46] |

| Upper Quartile (UQ) | Scales using 75th percentile | Simple and intuitive | Performance varies with expression distribution [46] |

| UQ-pgQ2 | Two-step per-gene Q2 after UQ scaling | Controls false positives with small samples | Recently developed, less widely tested [46] |

| Voom Transformation | Converts counts to log-CPM with precision weights | Enables linear modeling of RNA-seq data | Requires TMM, CPM, or Upper Quartile normalization [49] |

FAQ: How does sample size impact my RNA-Seq study?

The choice of sample size, specifically the number of biological replicates per group, is one of the most critical decisions in an RNA-Seq experimental design. It directly affects the accuracy of biological variance estimation and the statistical power to detect differential expression (DE). Biological replication measures the variation within the target population and is essential for robust statistical inference that can be generalized to the entire population under study [12] [8].

- Small Sample Sizes (e.g., n=3): While n=3 is a common starting point, it often provides limited power to detect anything but the most pronounced expression differences. With only three replicates, the estimation of biological variance can be unstable, which may lead to an increased number of both false positives and false negatives unless tools with specific conservative properties are used [50].

- Larger Sample Sizes (e.g., n≥6): Increasing the number of biological replicates significantly improves the power and reliability of your study. Research has shown that power to detect DE improves markedly when the number of biological replicates is increased [12]. A study with n≥6 replicates allows for a more accurate estimation of the natural variation in gene expression, enabling the confident identification of more subtle, yet biologically important, changes [8].

Table 1: Impact of Sample Size on RNA-Seq Experimental Outcomes

| Factor | Small Samples (n=3) | Larger Samples (n≥6) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Variance Estimation | Less accurate and stable | More accurate and reliable |

| Statistical Power | Lower; detects only large effect sizes | Higher; can detect subtler expression changes |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control | More challenging; higher risk of false positives/negatives | Better controlled; more robust and trustworthy results |

| Cost Efficiency | Lower per-experiment cost, but higher risk of failed or non-reproducible studies | Higher initial cost, but much better value and reproducibility for the investment |

FAQ: Which differential expression analysis tools are best for small sample sizes (n=3)?

When working with a limited number of replicates like n=3, the primary challenge is controlling false positives due to unstable variance estimates. The choice of software is crucial to mitigate this issue.

Recommendation: For studies with n=3, DESeq (and its successor, DESeq2) is often the recommended tool. It performs more conservatively than other methods, which helps to reduce the number of false positive findings when replicate numbers are low [12] [50].

Table 2: Tool Recommendations for Small vs. Larger Sample Sizes

| Sample Size | Recommended Tools | Key Rationale | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (n=3) | DESeq/DESeq2 | Conservative approach, better control of false positives. | Performs more conservatively than edgeR and NBPSeq at small sample sizes [12]. |

| Larger (n≥6) | edgeR | High power to uncover true positives. | Slightly better than DESeq and Cuffdiff2 at uncovering true positives, though potentially with more false positives [50]. |

| Larger (n≥6) | Intersection of Tools | Maximizes confidence in results. | Taking the intersection of DEGs from two or more tools (e.g., DESeq & edgeR) is recommended if minimizing false positives is critical [50]. |

Decision Workflow for Tool Selection Based on Sample Size

Given budget constraints, researchers often face the decision of whether to sequence each sample more deeply or to include more biological replicates.

Strong Recommendation: The evidence strongly suggests that greater power is gained through the use of biological replicates than through increasing sequencing depth or using technical (library) replicates [12]. One study even found that sequencing depth could be reduced to as low as 15% in a multiplexed design without substantial impacts on the false positive or true positive rates, underscoring the superior value of additional biological replication [12].

Practical Protocol: Implementing a Multiplexed Design

- Library Preparation: During the library preparation step, ligate distinct indexing barcodes (short, unique DNA sequences) to the cDNA fragments of each biological sample [12].

- Pooling: Combine the individually barcoded libraries into a single pool.

- Sequencing: Sequence the pooled libraries in a single sequencing lane or reaction on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq) [12].

- Demultiplexing: After sequencing, use computational tools to allocate the generated reads back to their original samples by identifying the unique barcodes [12].

This protocol allows for the profiling of multiple samples simultaneously, dramatically reducing the cost per sample and making studies with higher biological replication (n≥6) more feasible and cost-effective [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Barcodes/Indexes | Short DNA sequences ligated to samples for multiplexing, allowing multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced in one lane [12]. |

| DESeq / DESeq2 | A software package for DE analysis that uses a negative binomial model and is known for its conservative performance, ideal for low-replicate studies [12] [50]. |

| edgeR | A software package for DE analysis that also uses a negative binomial model and is noted for its high power to detect true positives with sufficient replication [12] [50]. |

| Negative Binomial Model | The statistical distribution used by most modern DE tools to model RNA-Seq count data and account for technical and biological variation (overdispersion) [50]. |

| Biological Replicates | Independent samples taken from different biological units (e.g., different animals, plants, or primary cell cultures) to measure natural variation within a population [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. For a short time course experiment with only 4 time points, should I use specialized time course tools or standard pairwise comparison methods? For short time series (typically <8 time points), standard pairwise comparison approaches often outperform specialized time course tools. Research has demonstrated that classical pairwise methods show better overall performance and robustness to noise on short series, with one notable exception being ImpulseDE2. Specialized time course tools tend to produce higher numbers of false positives in these scenarios. For longer time series, however, specialized tools like splineTC and maSigPro become more efficient and generate fewer false positives [51].

2. What is the fundamental statistical reason for choosing pairwise methods over temporal tools for short series? Specialized time course tools must account for temporal dependencies between time points, which requires estimating more complex statistical models with additional parameters. With limited time points (short series), these models can be underpowered and overfit the data, leading to increased false positives. Pairwise methods, building separate models for each comparison, have a simpler statistical structure that is more robust with limited data points [51] [52].

3. How does the number of biological replicates impact my choice of analysis method for time course data? The number of biological replicates significantly influences analysis power more than sequencing depth. For time course experiments, sufficient replicates are crucial for both pairwise and specialized temporal methods to accurately capture biological variation. When resources are limited, prioritizing more replicates over deeper sequencing or more time points generally provides better detection power for differentially expressed genes [11] [53] [54].

4. Can I use standard RNA-seq tools like DESeq2 or edgeR for time course experiments? Yes, both DESeq2 and edgeR can be applied to time course data. These tools can perform pairwise comparisons between individual time points or to a reference time point (typically time zero). They can also model time as a continuous variable in generalized linear models to test for expression trends over time. These packages use negative binomial distributions to model count data, which appropriately handles biological variation [55] [56] [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High False Positive Rates in Short Time Course Analysis