Pathway Enrichment Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications in Biomedicine

This article provides a complete guide to pathway enrichment analysis (PEA), a foundational bioinformatics method for interpreting gene lists from omics experiments.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Advanced Applications in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to pathway enrichment analysis (PEA), a foundational bioinformatics method for interpreting gene lists from omics experiments. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers core concepts, statistical methods, and practical workflows. Readers will learn to define gene lists, select appropriate enrichment tools like g:Profiler and GSEA, and interpret results using visualization platforms such as Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. The guide also addresses common pitfalls, optimization strategies for robust results, and advanced applications in drug repositioning and biomarker discovery, empowering users to confidently apply PEA in their research.

Understanding Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Pathway Enrichment Analysis? Defining the Method and Its Purpose

Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) is a core bioinformatic technique used to interpret lists of genes derived from genome-scale experiments. It identifies biological pathways—structured series of molecular interactions that lead to a cellular product or change—that are statistically overrepresented in a gene list, thereby transforming large, complex omics datasets into mechanistically interpretable biological insights [1] [2]. Its primary purpose is to help researchers move beyond a gene-by-gene interpretation of their data and instead understand the coordinated activity of genes within established biological systems, which is crucial for uncovering disease mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets [1] [3].

Core Principles and Definitions

At its heart, pathway enrichment analysis addresses a fundamental challenge in modern biology: how to extract meaningful biological understanding from long lists of genes, often comprising thousands of entries, generated by technologies like RNA sequencing or genome sequencing [1] [3].

- Pathway: A pathway is a model describing a series of interactions among molecules in a cell that leads to a certain product or a change. It is not a simple list but a structured network that captures knowledge about mechanisms, interactions, and dependencies, such as those found in KEGG or Reactome databases [3].

- Gene Set: In contrast, a gene set is an unordered and unstructured collection of genes, defined by a shared biological property, such as involvement in a specific biological process (e.g., cell cycle) or location on a chromosome. A pathway can be represented as a gene set, but this conversion loses all the topological and interaction information [3] [2].

- Gene List of Interest: This is the input for the analysis—a set of genes derived from an omics experiment, such as differentially expressed genes from an RNA-seq study or somatically mutated genes from cancer sequencing [1].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: This method identifies pathways that are statistically enriched in the gene list more than would be expected by chance alone. For example, if an experimental dataset contains 40% cell cycle genes, this would be surprisingly enriched given that only about 8% of human protein-coding genes are involved in this process [1].

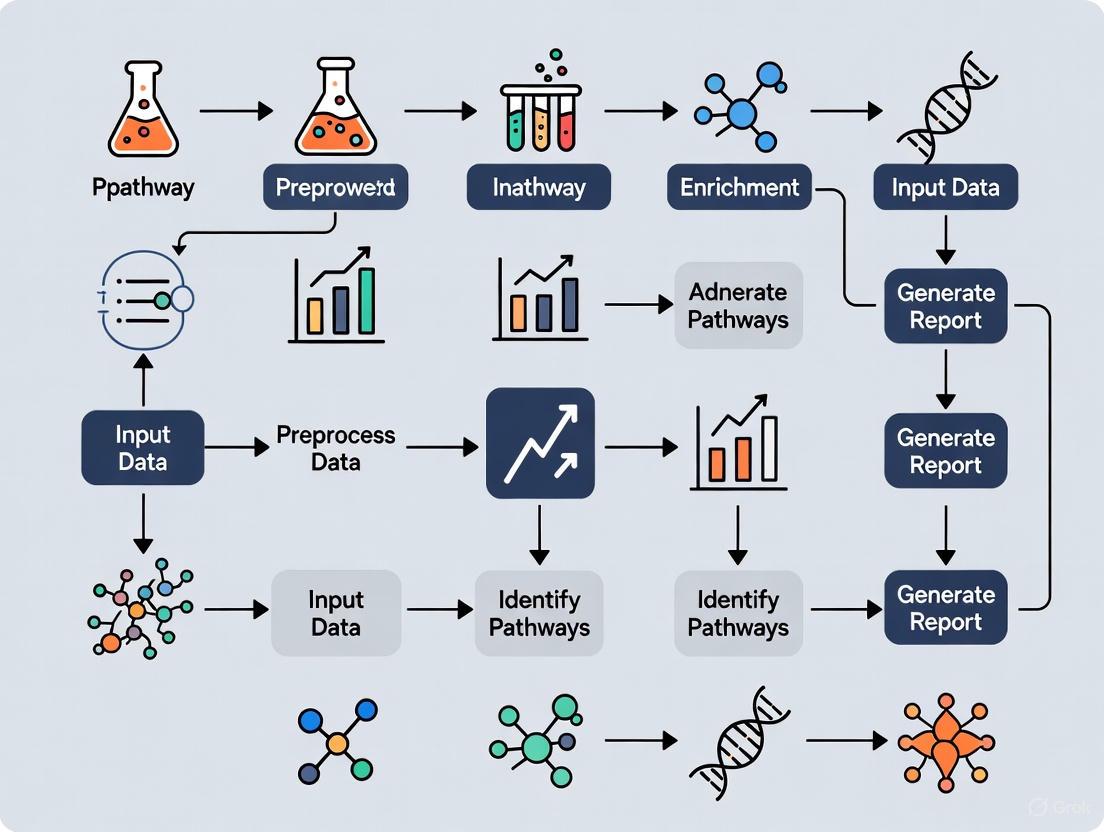

The following diagram illustrates the foundational concept of how a structured pathway is often simplified into a gene set for enrichment analysis, a process that discards valuable topological information.

The Analytical Workflow: From Data to Discovery

A standard protocol for pathway enrichment analysis comprises three major stages, which can be performed in approximately 4.5 hours using freely available software [1].

Stage 1: Definition of a Gene List from Omics Data

The first step involves processing raw omics data to create a gene list suitable for analysis. The input can take one of two primary forms:

- Gene List: A simple set of genes, such as all somatically mutated genes in a tumor identified by exome sequencing. This is suitable for direct input into tools like g:Profiler [1].

- Ranked Gene List: A list of all genes measured in an experiment, ranked by a score such as the level of differential expression or a p-value. This format preserves more information and is the required input for methods like Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [1].

Stage 2: Determination of Statistically Enriched Pathways

A statistical method is applied to identify pathways that are significantly overrepresented in the gene list. There are three general methodological approaches, each with its own strengths.

Stage 3: Visualization and Interpretation

The final stage involves making sense of the list of enriched pathways, which often includes many related terms. Visualization tools like Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap help identify the main biological themes and their relationships for in-depth study and experimental validation [1].

The complete workflow, integrating these stages, is visualized below.

Key Methodological Approaches

Researchers can choose from several methodological approaches for enrichment analysis, each with distinct underlying principles and data requirements.

| Method | Description | Input Required | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) [2] | Statistically tests if a pathway contains more genes from the input list than expected by chance. | A list of genes (e.g., differentially expressed genes). | Simple, intuitive, and requires only gene identifiers. |

| Functional Class Scoring (FCS) [2] | Considers the full ranked list of genes to identify pathways where members are clustered at the top or bottom. | A ranked list of all genes from the experiment. | More sensitive; does not require an arbitrary significance cutoff for individual genes. |

| Pathway Topology (PT) [3] | Incorporates the pathway structure (interactions, positions, and roles of genes) into the analysis. | A gene list or ranked list, plus pathway topology data. | Uses more biological knowledge; can predict downstream effects and pathway activity. |

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) is often the simplest starting point. It uses statistical tests like the hypergeometric test to ask whether the number of genes from a particular pathway found in the experimental list is larger than what would be expected if genes were selected at random from the background genome [2]. Its main limitation is its dependence on an often-arbitrary threshold to define the input gene list [3].

Functional Class Scoring (FCS) methods, such as the widely used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), address this limitation. GSEA uses a ranked list of all genes and a Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistic to determine if members of a predefined gene set are randomly distributed throughout the list or found primarily at the top or bottom [1] [2]. A positively enriched pathway has its genes clustered at the top of the ranked list (e.g., highly upregulated), while a negatively enriched pathway has its genes clustered at the bottom [1].

Pathway Topology (PT) methods represent a more advanced approach. They leverage the detailed knowledge embedded in pathway diagrams, such as activation/inhibition relationships and signal flow. For example, if a pathway is triggered by a single receptor and that gene is not expressed, the entire pathway may be shut off. Conversely, changes in downstream genes might have less impact. Methods like Impact Analysis use this information to calculate a pathway perturbation score, producing more biologically accurate results [3].

Essential Databases and Research Toolkit

The utility of any enrichment analysis is directly tied to the quality and comprehensiveness of the pathway databases used. The table below summarizes key resources.

| Database | Type | Description & Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology (GO) [1] | Gene Set | A hierarchically organized set of thousands of standardized terms for biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Biological Process terms are most commonly used. |

| MSigDB [1] | Gene Set | A large, curated database of gene sets from various sources, including GO, pathways, and published studies. Its "Hallmark" gene set collection is a relatively non-redundant, useful resource. |

| Reactome [1] | Detailed Pathway | An actively updated, general-purpose public database of human pathways with detailed biochemical reactions and regulatory events. |

| KEGG [1] | Detailed Pathway | Provides intuitive pathway diagrams for metabolism, signaling, and disease. Licensing restrictions can affect free access to up-to-date files. |

| WikiPathways [1] | Meta-Database | A community-driven, open-source platform that collects and creates pathways from various sources. |

| PFOCR [4] | Novel Database | Uses machine learning to extract pathway information and gene sets directly from published pathway figures in the literature, offering exceptional breadth and direct literature support. |

Beyond databases, a successful analysis relies on a toolkit of software and platforms.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| g:Profiler [1] | Enrichment Analysis Tool | A free web tool for ORA, known for ease of use, extensive documentation, and up-to-date databases. |

| GSEA [1] | Enrichment Analysis Software | The original software for FCS, widely used for analyzing ranked gene lists against gene sets, notably from MSigDB. |

| Cytoscape & EnrichmentMap [1] | Visualization | Free, open-source platforms for visualizing molecular interaction networks and enrichment results, helping to identify overarching themes. |

| STAGEs [5] | Integrated Web Tool | A web-based platform that integrates data visualization (e.g., volcano plots) with pathway enrichment analysis using Enrichr and GSEA, simplifying the workflow. |

| PEANUT [6] | Network-Based Tool | A newer tool that enhances traditional analysis by integrating protein-protein interaction networks to amplify signals from connected gene sets. |

| QIAGEN IPA [7] | Commercial Platform | A comprehensive, commercial software built on an expert-curated knowledge base, offering causal reasoning and upstream regulator analysis. |

Purpose and Impact in Biomedical Research

The core purpose of pathway enrichment analysis is to add mechanistic insight and biological context to observational gene lists. It is a critical step in translating data into discovery.

- Gaining Mechanistic Insight: PEA helps answer the question, "What biological processes are most relevant to my experimental condition?" It shifts the focus from individual genes to systems-level biology, revealing the orchestrated activity that underlies phenotypes [1] [3].

- Prioritizing Findings: By providing a statistical framework, PEA allows researchers to prioritize pathways, rather than individual genes, for further experimental investigation. This is especially valuable in drug repurposing efforts, where analyzing shared mechanisms of action across multiple drugs can increase on-target signal and reduce false leads [8].

- Generating Testable Hypotheses: The list of enriched pathways serves as a source of new, testable hypotheses about disease mechanisms or treatment effects. For instance, identifying histone and DNA methylation as an enriched pathway in childhood ependymoma led to the rational therapeutic use of 5-azacytidine, which stopped rapid metastatic tumor growth in a terminally ill patient [1].

Pathway Enrichment Analysis is an indispensable bioinformatic method for interpreting high-throughput biological data. By statistically evaluating the collective behavior of genes within the context of predefined biological pathways, it provides a powerful lens through which researchers can discern meaningful patterns and mechanisms in complex datasets. The field continues to evolve with the integration of network biology, more sophisticated topological analyses, and the development of expansive new resources like PFOCR. For researchers in basic science, translational medicine, and drug development, a firm grasp of PEA's principles, methods, and tools is fundamental to transforming genomic data into actionable biological knowledge and therapeutic advances.

Pathway enrichment analysis is a cornerstone of functional genomics, enabling researchers to move beyond a simple list of differentially expressed genes to a mechanistic understanding of the biological processes underlying their experimental data. This analytical approach statistically evaluates whether pre-defined sets of genes (pathways or gene sets) are over-represented in an experimentally derived gene list more than would be expected by chance [2] [9]. By harnessing prior biological knowledge, pathway analysis increases statistical power, eases interpretation, and helps predict new roles for genes, making it particularly valuable for studying complex diseases where individual genetic effects may be modest but concerted pathway-level effects are substantial [2] [9].

The fundamental motivation for pathway analysis stems from observations that multiple disease-associated genetic variants often impinge on a limited number of common pathways or interacting networks. Notable examples include synaptic biology in schizophrenia, cytokine pathways in immune diseases, and complement pathways in age-related macular degeneration [9]. This approach stands in contrast to single-locus analysis, as it takes a multilocus strategy that capitalizes on biological knowledge, thereby increasing discovery power while facilitating biological interpretation of statistical associations [9].

Core Statistical Frameworks in Pathway Analysis

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA)

Over-Representation Analysis represents the first generation of pathway analysis methods. ORA statistically evaluates whether the fraction of genes in a particular pathway found among a set of differentially expressed genes is greater than what would be expected by random chance [2]. The method begins with a list of differentially expressed genes, typically identified using an arbitrary threshold (e.g., p-value < 0.05, fold change > 2), and then identifies pathways that are over- or under-represented in this gene list [2] [3].

The statistical foundation of ORA typically relies on the hypergeometric distribution, Fisher's exact test, chi-square test, or binomial distribution. These tests determine the probability that the number of genes from a particular pathway observed in the differentially expressed gene list would occur by random chance [2]. The hypergeometric test is conceptually equivalent to the "urn problem": if you have a total of N genes in the genome, with K genes belonging to a pathway of interest, and you draw n genes (your list of differentially expressed genes), what is the probability that k or more of these drawn genes belong to the pathway of interest?

Key assumptions and limitations of ORA include:

- It requires an appropriate background gene set for comparison, which could be all genes in the organism, all protein-coding genes, or only genes measured/expressed in the experiment [2]

- It depends heavily on the arbitrary threshold used to select differentially expressed genes [3]

- It assumes independence between genes [2]

- It discards quantitative information about the magnitude of expression changes [3]

Functional Class Scoring (FCS) Methods

Functional Class Scoring methods represent a second generation of pathway analysis approaches designed to overcome some limitations of ORA. Rather than relying on an arbitrary threshold to select differentially expressed genes, FCS methods consider all measured genes and their expression values [2] [3]. The fundamental hypothesis behind these methods is that small but coordinated changes in sets of functionally related genes may be biologically important, even if individual genes do not show large expression changes [3].

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) is arguably the most prominent FCS method. Instead of pre-selecting genes based on significance thresholds, GSEA uses all genes ranked by the magnitude of their expression change between conditions [2]. The ranking is typically based on a combination of fold change and statistical significance, with the most strongly upregulated and significant genes at the top and the most strongly downregulated and significant genes at the bottom [2]. GSEA then determines whether members of a predefined gene set are randomly distributed throughout this ranked list or primarily found at the top or bottom, suggesting coordinated differential expression [2].

The method creates a running sum statistic (enrichment score) that increases when a gene in the set is encountered and decreases when genes not in the set are encountered. The enrichment score is then normalized and assessed for statistical significance using a permutation-based approach [2]. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) is a curated resource of thousands of gene sets specifically designed for use with GSEA and similar methods [2].

Pathway Topology-Based Methods

Pathway Topology methods represent the third generation of pathway analysis approaches that aim to incorporate the rich biological knowledge embedded in pathway structures. While both ORA and FCS methods treat pathways as simple gene sets (unordered collections of genes), topology-based methods recognize that pathways are complex models describing biological processes, mechanisms, and interactions [3].

These methods utilize prior knowledge about pathway topology - including the positions and roles of genes, types of interactions (activation, repression, phosphorylation), direction of signal propagation, and other relational information - to derive more biologically meaningful assessments of pathway perturbation [2] [3]. Impact Analysis, for example, constructs a mathematical model that captures the entire topology of a pathway and uses it to calculate perturbations for each gene, which are then combined into a total perturbation for the entire pathway [2].

Key advantages of topology-based methods include:

- They account for the type and direction of interactions within pathways [3]

- They consider the positions and roles of genes within pathways [3]

- They can predict or explain downstream or pathway-level effects [3]

- They help identify specifically affected mechanisms in an experiment [3]

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Analysis Methodologies

| Feature | Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) | Functional Class Scoring (FCS) | Pathway Topology (PT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | List of differentially expressed genes | All genes with expression values | All genes with expression values plus pathway structure |

| Statistical Basis | Hypergeometric, Fisher's exact test | Kolmogorov-Smirnov, permutation tests | Network perturbation models |

| Handles Subtle Effects | No | Yes | Yes |

| Uses Pathway Structure | No | No | Yes |

| Key Advantage | Simple, intuitive | No arbitrary threshold needed | Biologically realistic |

| Key Limitation | Depends on arbitrary threshold | Ignores pathway structure | Requires curated pathway data |

The Multiple Testing Problem in Pathway Analysis

Understanding the Multiple Comparisons Problem

In pathway analysis, researchers typically test hundreds or thousands of gene sets simultaneously, which creates a substantial multiple testing problem. When conducting multiple independent statistical tests, the probability of obtaining at least one false positive result increases dramatically with the number of tests performed [10]. For example, if 20 independent tests are conducted with a significance level (α) of 0.05, the probability of observing at least one false positive is approximately 64% [10].

The multiple comparisons problem arises because the significance level α represents the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true (Type I error). When conducting m independent tests, the probability of making at least one Type I error (called the family-wise error rate or FWER) is given by:

1 - (1 - α)^m

For m = 20 tests with α = 0.05, this becomes 1 - (0.95)^20 ≈ 0.64, meaning there's a 64% chance of at least one false positive [10] [11]. In pathway analysis, where the number of tests can be much larger, this problem becomes even more pronounced, making multiple testing correction an essential step in the analytical workflow [9].

Correction Methods

Bonferroni Correction

The Bonferroni correction is the simplest and most conservative method for multiple testing correction. It controls the family-wise error rate (FWER), which is the probability of making at least one Type I error across all tests [10] [11]. The method works by dividing the desired significance level (α) by the number of tests performed (m):

Adjusted significance threshold = α/m

For example, with an original α of 0.05 and 20 tests, the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold would be 0.05/20 = 0.0025 [10]. Any p-value below this adjusted threshold would be considered statistically significant after correction.

The Bonferroni correction is based on the union bound, which states that the probability of at least one false positive is less than or equal to the sum of the individual false positive probabilities [10]. While this method provides strong control over false positives, it can be overly conservative, especially when dealing with many tests or correlated hypotheses, leading to increased Type II errors (false negatives) and reduced statistical power [10] [11].

False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control

As an alternative to the conservative Bonferroni approach, methods controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR) have gained popularity in genomic applications. The FDR is the expected proportion of false positives among all significant tests [10]. Unlike the FWER, which controls the probability of at least one false positive, FDR methods allow a small proportion of false positives while maintaining higher statistical power [10].

The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure is the most widely used FDR-controlling method. It works by:

- Sorting all p-values from smallest to largest: p(1) ≤ p(2) ≤ ... ≤ p(m)

- Finding the largest k such that p(k) ≤ (k/m) × α

- Declaring the tests corresponding to p(1), p(2), ..., p(k) as significant

This approach is less conservative than Bonferroni correction and is particularly useful in high-throughput genomic studies where researchers are willing to tolerate some false positives in exchange for greater power to detect true effects [10].

Table 2: Multiple Testing Correction Methods

| Method | Controls | Approach | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni | Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) | Divide α by number of tests (α/m) | When false positives are very costly; small number of tests |

| Holm-Bonferroni | FWER | Step-down procedure: order p-values and compare to α/(m+1-i) | Less conservative than Bonferroni; general FWER control |

| Benjamini-Hochberg | False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Step-up procedure controlling expected proportion of false discoveries | Genomic studies; large number of tests; balance of power and precision |

Experimental Design and Workflow

Pathway Analysis Workflow

A comprehensive pathway analysis involves multiple critical steps, each requiring careful consideration to ensure biologically meaningful and statistically valid results. The major analytical procedures include hypothesis selection, SNP-to-gene mapping (for genetic data), enrichment testing, and multiple testing correction [9].

Pathway Analysis Workflow

Critical Experimental Considerations

Several key decisions throughout the pathway analysis workflow can significantly impact results and interpretation:

Gene Set Selection: The choice of gene set database fundamentally shapes analytical outcomes. Major categories include functional annotation-based sets (Gene Ontology, KEGG, Reactome), disorder-based sets, and high-throughput data-derived sets [9]. Each database has different coverage, curation standards, and biological emphasis, making database selection a critical consideration.

Background Set Definition: The appropriate background set for comparison must reflect the experimental context. Options include all genes in the genome, all protein-coding genes, only genes measured on the specific platform used, or only genes expressed in the experimental system [2]. An improperly specified background can introduce substantial bias.

SNP-to-Gene Mapping (for GWAS): When analyzing genetic variation data, the strategy for connecting genetic variants to genes significantly influences results. Approaches include mapping to the nearest gene, using a specific window size, incorporating regulatory information, or employing chromatin interaction data [9].

Handling Gene Length and GC Content Bias: Certain analysis methods may be susceptible to biases related to gene length or GC content, particularly for RNA-seq data. These technical artifacts can disproportionately influence results if not properly addressed [9].

Key Databases and Knowledgebases

Successful pathway analysis relies heavily on high-quality, curated biological knowledge resources. These databases provide the gene sets and pathway information that form the foundation of enrichment analysis.

Table 3: Essential Pathway Analysis Resources

| Resource | Type | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Functional Annotation | Three domains: Molecular Function, Cellular Component, Biological Process; species-agnostic | General functional enrichment; ORA analysis |

| KEGG | Pathway Database | Curated biological pathways; molecular interaction networks; pathway maps | Metabolic and signaling pathway analysis |

| Reactome | Pathway Database | Human-specific; curated signaling, metabolic processes; disease pathways | Detailed pathway analysis; visualization |

| MSigDB | Gene Set Collection | 34,837+ gene sets; curated for GSEA; hallmark collections with reduced redundancy | GSEA analysis; immunological research |

| PANTHER | Classification System | Protein families and phylogenetic trees; evolutionary relationships | Evolutionarily informed analysis |

| WikiPathways | Pathway Database | Community-curated; continuously updated; diverse pathways | Novel pathway discovery; less established mechanisms |

Analytical Tools and Software

The pathway analysis landscape includes numerous software tools and packages implementing various statistical approaches:

Web-Based Tools: DAVID, Qiagen IPA, and WebGestalt provide user-friendly interfaces for ORA and basic enrichment analysis, making them accessible to wet-lab researchers without programming expertise [2].

R/Bioconductor Packages: Tools like clusterProfiler, fgsea, and SPIA offer programmatic access to advanced analysis methods, enabling customized workflows and integration with other bioinformatics analyses [2].

Specialized Software: GSEA from the Broad Institute provides a standalone desktop application specifically optimized for gene set enrichment analysis, with tight integration to MSigDB [2].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Pathway analysis continues to evolve with methodological advancements and expanding applications. Integrative approaches that combine multiple data types (genetic variation, gene expression, epigenetic modifications) represent the cutting edge of pathway analysis methodology [9]. These methods leverage complementary information to provide more comprehensive biological insights than single-data-type analyses.

Emerging applications include:

- Multi-omics pathway analysis integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data

- Cell-type-specific pathway analysis using single-cell sequencing data

- Cross-disorder pathway analysis identifying shared biological mechanisms

- Pharmacogenomic pathway analysis for drug target identification

As pathway analysis methodologies mature, considerations of power, sample size, and analytical validity become increasingly important. Future developments will likely focus on improving statistical power for detecting pathway-level signals, enhancing methods for multi-omics integration, and developing more sophisticated approaches for modeling pathway dynamics and interactions [9].

Integrative Multi-omics Pathway Analysis

Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) is a cornerstone bioinformatics method for interpreting the results of genome-scale experiments. It helps researchers move from seemingly impenetrable lists of genes to a mechanistic understanding of the underlying biology by identifying predefined sets of biologically related genes that are statistically overrepresented [12] [1]. In modern research, technologies like RNA-seq, proteomics, and genome sequencing comprehensively measure cellular molecules but often produce lists of hundreds or thousands of significant genes. Manually sifting through these lists is impractical [1]. PEA addresses this challenge by summarizing large gene lists into a smaller, more interpretable set of biological pathways or processes, effectively translating data into biological insight [1]. For instance, it has been used to identify histone and DNA methylation as a therapeutic target in a childhood brain cancer, leading to a compassionate treatment that stopped tumor growth [1]. This protocol is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to understand complex disease mechanisms, identify novel therapeutic targets, and generate testable hypotheses from high-throughput omics data.

Core Terminology and Definitions

A precise understanding of the key terms is fundamental to correctly applying and interpreting pathway enrichment analysis. The following table structures and defines the essential vocabulary in this field.

Table 1: Essential Terminology in Pathway Enrichment Analysis

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Set | An unordered, unstructured collection of genes grouped by a shared biological property, location, or involvement in a pathway [3] [13]. | Lacks internal structure; a simple list. Examples: genes on chromosome 1, genes from a KEGG pathway. |

| Pathway | A series of interactions among molecules in a cell that leads to a product or change, describing specific mechanisms, phenomena, and dependencies [3]. | A model with structure, interactions, and directionality (e.g., KEGG, Reactome pathways). |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) | A statistical technique to identify pathways significantly overrepresented in a gene list more than expected by chance [12] [1]. | An umbrella term; sometimes used interchangeably with Functional Enrichment Analysis. |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) | A specific computational method determining if a predefined gene set shows significant, concordant differences between two biological states [14]. | Both an analysis type (see below) and a specific software tool from Broad Institute [14]. |

| Enrichment Score (ES) | A statistic quantifying the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the extremes (top or bottom) of a ranked gene list [15]. | A Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like statistic; core to the GSEA method. |

| Leading Edge Genes | A subset of genes in an enriched set that appear at the start of the enrichment peak and are considered the primary drivers of the enrichment signal [1]. | Often account for a pathway being defined as enriched. |

Pathways vs. Gene Sets: A Critical Distinction

While the terms "pathway" and "gene set" are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent fundamentally different concepts. A pathway is a detailed model that describes a biological process, such as a signaling cascade or a metabolic reaction. It contains crucial information about the roles, interactions, and directionality between genes and gene products. For example, the KEGG MAPK signaling pathway shows which genes activate others, the location of interactions, and the flow of information [3].

In contrast, a gene set is simply the list of genes involved in that pathway, stripped of all its structural and relational context [3]. Treating a pathway as a mere gene set discards valuable biological knowledge about how genes interact. This distinction is critical because topology-based analysis methods that use full pathway information can produce more accurate and biologically meaningful results than those that use gene sets alone [3] [13].

Key Methodological Approaches

There are three primary methodological approaches to functional enrichment analysis, each with its own strengths, limitations, and statistical foundations.

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA)

Concept: Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) is the simplest and most straightforward approach. It tests whether genes from a pre-defined gene set are present in a submitted list of interesting genes more than would be expected by chance [13].

Workflow and Statistical Foundation:

- Input: A list of significant genes derived from an omics experiment, typically created by applying a cutoff (e.g., adjusted p-value < 0.05 and fold-change > 2) [1] [13].

- Statistical Test: A Fisher's exact test or a hypergeometric test is commonly used to calculate the probability (p-value) of observing the overlap between the submitted list and the gene set by random chance [12] [16] [13].

- Output: A list of gene sets that are statistically overrepresented in the submitted gene list.

Limitations: ORA is sensitive to the arbitrary cutoff used to create the input gene list and assumes gene independence, which is often biologically unrealistic [13]. It also ignores the magnitude of gene expression changes [3].

Functional Class Scoring (FCS) / Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Concept: Functional Class Scoring (FCS) methods, most famously Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), were designed to overcome the cutoff dependency of ORA. Instead of a simple list, these methods use a ranked list of all genes from an experiment (e.g., ranked by differential expression statistic) to identify gene sets enriched at the top or bottom of the list [15] [13].

Workflow and Statistical Foundation (GSEA):

- Input: A ranked list of all genes from an omics dataset [1].

- Enrichment Score (ES) Calculation: The ES is the primary statistic. It is calculated by walking down the ranked list, increasing a running sum when a gene is in the set (S) and decreasing it when it is not. The increment is based on the gene's correlation with the phenotype. The ES is the maximum deviation from zero encountered [15].

- Phit(S,i) = ∑ (|rj|^p / NR) for genes gj in S, j ≤ i

- Pmiss(S,i) = ∑ (1/(N-NH)) for genes gj not in S, j ≤ i

- ES = max|Phit(S,i) - Pmiss(S,i)|, where rj is the gene's correlation, p is a weighting exponent, NR is a normalization factor, N is the total genes, and NH is genes in the set [15].

- Significance Estimation: The significance of the ES is estimated by comparing it to a null distribution generated by permuting the phenotype labels [15].

- Multiple Testing Correction: The final step adjusts for testing multiple gene sets simultaneously, typically by controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [15].

Advantages: GSEA is more sensitive than ORA because it can detect subtle but coordinated changes in a group of genes, where individual genes may not be significant on their own [15] [13].

Pathway Topology (PT) Methods

Concept: Pathway Topology (PT) methods, also known as topology-based (TB) or "pathway analysis," represent a more advanced approach that moves beyond simple gene sets. They incorporate the detailed structure of pathways, including the positions of genes, the types of interactions (e.g., activation, inhibition), and the direction of signal flow [3] [13].

Workflow and Statistical Foundation:

- Input: Gene expression data and a structured pathway model from databases like KEGG or Reactome.

- Analysis: The method considers how measured gene expression changes propagate through the pathway's network structure. For example, the absence of an upstream receptor (e.g., INSR in the insulin pathway) would have a much greater impact than a change in a downstream component [3].

- Output: A ranked list of pathways whose overall activity is deemed significantly perturbed, considering the network topology.

Advantages: PT methods can more accurately model biological reality and predict the functional impact of expression changes, potentially leading to more relevant and robust results [3]. Limitations: They require high-quality, detailed pathway models, which are not available for all organisms or processes [13].

Diagram: Three primary methodological approaches for enrichment analysis, highlighting their distinct inputs and key characteristics.

Quantitative Foundations: Enrichment Scores and Statistics

The core of any enrichment method is its statistical engine. The following table compares the quantitative foundations of the major approaches.

Table 2: Statistical Foundations of Enrichment Methods

| Method | Core Statistical Test | Key Metrics & Scores | Data Input Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORA | Fisher's Exact Test / Hypergeometric Test [12] [16] | P-value, Odds Ratio, Enrichment Score (Observed/Expected) [16] | List of significant genes (uses a cutoff) [13] |

| GSEA | Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like statistic with permutation testing [15] | Enrichment Score (ES), Normalized ES (NES), False Discovery Rate (FDR), Leading-edge genes [15] [1] | Ranked list of all genes (no cutoff) [1] |

| Topology-Based | Varies by method (e.g., Impact Analysis) [3] | Pathway Impact P-value, Perturbation Statistic | Gene expression data and a structured pathway model [3] |

The GSEA Enrichment Score in Detail

The GSEA Enrichment Score (ES) is a pivotal statistic in modern enrichment analysis. It is calculated by walking down a ranked list of genes (e.g., ranked by correlation with a phenotype) and evaluating the distribution of genes in a set S [15].

- Enrichment Score (ES): The maximum deviation from zero of a running sum statistic, Phit - Pmiss [15].

- Phit(S,i): Increases when a gene in the set S is encountered. The increment is proportional to |rj|^p, where rj is the gene's correlation with the phenotype, allowing genes more strongly correlated with the phenotype to contribute more to the score [15].

- Pmiss(S,i): Increases when a gene not in the set S is encountered, ensuring sets that are randomly distributed receive a low score [15].

- Normalized ES (NES): The ES is normalized for the size of the gene set, allowing for comparison across gene sets of different sizes [15].

- Significance: The NES is compared to a null distribution generated by permuting phenotype labels, yielding a nominal p-value. This is then adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing across all gene sets, resulting in an FDR q-value [15].

Diagram: The workflow for calculating and evaluating the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Enrichment Score.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Databases and Software

Successful pathway enrichment analysis relies on using curated knowledge bases and robust software tools.

Essential Pathway and Gene Set Databases

Table 3: Key Databases for Pathway and Gene Set Information

| Database | Type | Scope and Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology (GO) [1] | Ontology | A hierarchically structured, standardized vocabulary of terms for Biological Processes, Molecular Functions, and Cellular Components [1]. |

| Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [14] [1] | Gene Set Database | A large, comprehensive collection of over 10,000 annotated gene sets, including those from GO, pathways, and literature signatures [14] [1]. |

| Reactome [1] | Pathway Database | An open-access, peer-reviewed database of detailed human biological pathways, actively curated and updated [1]. |

| KEGG [1] [3] | Pathway Database | Known for intuitive pathway diagrams; includes metabolic, signaling, and disease-related pathways [1] [3]. |

| WikiPathways [1] | Pathway Meta-Database | A community-driven, collaborative platform for pathway curation and collection [1]. |

Software Tools for Analysis

A wide array of tools exists, from web-based platforms to command-line packages.

- g:Profiler: A widely used tool for ORA, available as both a web server and an R package. It supports multiple organisms and statistical corrections [12] [1].

- Enrichr: A popular, user-friendly web tool that provides ORA against a vast and frequently updated collection of gene set libraries [15] [17].

- GSEA Software: The original desktop implementation of the GSEA algorithm from the Broad Institute, tightly integrated with the MSigDB [14].

- clusterProfiler: An R/Bioconductor package that is highly versatile and powerful, supporting both ORA and GSEA methods for comparative functional analysis [15] [13].

- Cytoscape & EnrichmentMap: A powerful visualization platform. The EnrichmentMap app can create network-based visualizations of enrichment results, helping to identify overarching biological themes [1].

- Topology-Based Tools: R packages like ROntoTools and TPEA implement various topology-based algorithms for a more in-depth pathway impact analysis [3] [13].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

This protocol, adapted from a Nature Protocols article, outlines a standard workflow for performing and visualizing a pathway enrichment analysis, suitable for data from RNA-seq or genome-sequencing experiments [1].

Stage 1: Define a Gene List of Interest

The first step is to process your omics data to create a gene list for analysis. The type of list depends on your data and chosen method [1].

- For ORA (e.g., using g:Profiler): Generate a list of significant genes. This typically involves applying a threshold to your data, such as an adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 and an absolute fold-change > 2, to define a set of differentially expressed genes [1] [13].

- For GSEA (e.g., using GSEA software): Create a ranked list of all genes. Genes are typically ranked by a metric that reflects their association with the phenotype, such as the signed -log10(p-value) (where the sign is taken from the fold-change) or the signal-to-noise ratio [1].

Stage 2: Perform Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Using g:Profiler (ORA):

- Access the g:Profiler web tool (g:GOSt) or R package.

- Input your list of significant genes.

- Select the organism and relevant data sources (e.g., GO:BP, KEGG, Reactome).

- Set the significance threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05) and run the analysis [1].

Using GSEA Software:

- Prepare your input files: a normalized gene expression dataset (.gct) and a phenotype labels file (.cls).

- Load your data and the desired gene set database (e.g., from MSigDB).

- Set the permutation type (usually phenotype) and the number of permutations (e.g., 1000).

- Run the GSEA analysis. The output will include the enriched gene sets, their ES, NES, FDR, and leading-edge genes [1].

Stage 3: Visualize and Interpret Results

Visualization is key to interpreting the often long list of enriched pathways.

- EnrichmentMap for Cytoscape: This is a highly effective visualization technique.

- Import your GSEA or g:Profiler results into Cytoscape via the EnrichmentMap app.

- The app automatically generates a network where nodes represent enriched gene sets and edges represent the overlap of genes between sets. This clusters related pathways (e.g., all immune-related processes), allowing you to see broad biological themes rather than isolated terms [1].

- Voronoi Maps (Reactome): Tools like Reactome provide alternative visualizations like Voronoi maps, which offer a tiled overview of analysis results, with tile size and color often representing the statistical significance of the enrichment [18].

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

As the field evolves, several advanced concepts are becoming critical for robust and cutting-edge research.

- Multi-Omics Integration: A major frontier is the integration of multiple omics datasets (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics) to gain a holistic understanding. Methods like ActivePathways and its extension Directional P-value Merging (DPM) allow for the fusion of p-values and directional changes (e.g., fold-changes) across datasets, prioritizing genes and pathways with consistent signals [19].

- Best Practices and Pitfalls: To ensure meaningful results:

- Clarify Your Analysis Type: Before starting, decide whether ORA, GSEA, or PT is most appropriate for your data and question [12].

- Ensure Input Data Quality: The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" applies. Use high-quality, well-processed input gene lists [12].

- Apply Multiple Testing Correction: Always use FDR or another correction method to account for the thousands of pathways tested, reducing false positives [1].

- Understand the Limitations: No single method is perfect. Be aware that gene set analysis does not inherently indicate if a pathway is activated or inhibited, and it relies on the completeness and accuracy of the underlying databases [12] [13].

Pathway Enrichment Analysis is an indispensable technique for translating high-throughput genomic data into biological insight. A firm grasp of the essential terminology—distinguishing a gene set from a pathway, and understanding what an enrichment score represents—is the foundation. By selecting the appropriate methodological approach (ORA, FCS/GSEA, or PT) and leveraging the powerful databases and software tools available, researchers can systematically uncover the functional themes and mechanistic underpinnings of their experiments. As the field moves towards multi-omics integration and more sophisticated topology-based models, these core concepts will continue to be vital for driving discovery in biology and drug development.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) is a foundational computational biology method used to interpret lists of genes or proteins derived from high-throughput omics experiments. It identifies biological pathways—predefined sets of genes that collectively perform a specific function—that are overrepresented in a gene list more than would be expected by chance [12]. This process helps researchers move from a simple list of differentially expressed genes to a functional understanding of the underlying biology, revealing the processes most affected in a given condition, such as disease states or drug treatments.

Two primary computational approaches are used: Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). ORA uses statistical tests like the hypergeometric test or Fisher's exact test to determine if certain pathways contain a disproportionately high number of genes from an input list, typically a set of differentially expressed genes identified using a significance cutoff [20] [12]. In contrast, GSEA considers the entire ranked list of genes (e.g., by expression fold-change or p-value) without requiring an arbitrary cutoff. It identifies pathways where genes are concentrated at the extreme ends (top or bottom) of the ranked list, detecting subtle but coordinated changes in expression that might be missed by ORA [14] [20] [12]. The choice between these methods depends on the research question and data type, a critical decision point for generating robust results [12].

Core Pathway Databases

Several curated databases provide the biological pathway and gene set definitions essential for enrichment analysis. The table below summarizes the key features of five major resources.

Table 1: Core Features of Major Pathway Databases

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Features & Content | Species Coverage | Update Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology (GO) [12] | Structured, hierarchical vocabulary (ontologies) for gene function. | Three independent aspects: Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Cellular Component. | Extensive, many species | Continuously updated |

| KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) [12] | Reference knowledge on biological pathways and systems. | Well-known pathway maps for metabolism, genetic information processing, and human diseases. | Extensive, many species | Updated regularly (e.g., Nov 2023) [21] |

| Reactome [22] [23] | Expert-authored, detailed molecular pathways. | ~2,825 human pathways with 16,002 reactions; includes detailed pathway topology and expression overlay. | Extensive, but projects other species to human by default [22] | Version 94 (Sept 2025) [23] |

| MSigDB (Molecular Signatures Database) [14] | Broad collection of annotated gene sets for GSEA. | Includes Hallmark sets, curated pathways, GO terms, and computational signatures from published studies. | Human, mouse, rat [24] | MSigDB 2025.1 (Jun 2025) [14] |

| WikiPathways [12] | Collaborative, community-curated pathway resource. | Diverse pathway content curated by researchers; pathways are editable and versioned. | Extensive, many species | Continuously updated [25] |

Detailed Database Profiles

Gene Ontology (GO): GO is not a pathway database in the traditional sense but a comprehensive, structured vocabulary that describes the roles of genes and gene products. Its value in enrichment analysis lies in its ability to provide a deep functional context. An enrichment result for a term like "positive regulation of cell migration" (a Biological Process) can offer a more granular understanding of phenotype than a broader pathway might [12].

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes): KEGG provides manually drawn reference pathway maps that are widely recognized in the scientific community. It is particularly strong in metabolic pathways and disease-related pathways. The KEGG Mapper Color tool allows users to visualize their own data (e.g., gene identifiers with color specifications) directly onto these pathway maps for intuitive interpretation [21].

Reactome: Reactome is an open-access, peer-reviewed database known for its highly detailed and accurate molecular pathways. A key strength is its powerful analysis toolkit, which supports not only standard over-representation analysis but also pathway topology analysis, which considers the connectivity between molecules in a pathway. Furthermore, Reactome allows the overlay of expression data or other numerical values onto its pathway diagrams, enabling powerful visualization of experimental results [22] [23].

MSigDB (Molecular Signatures Database): MSigDB is a massive, diverse collection of gene sets designed specifically for use with GSEA software. Its collections extend beyond canonical pathways to include gene sets derived from perturbation studies, genetic signatures, and immunologic signatures. A notable feature is the "Hallmark" gene sets, which summarize and represent specific well-defined biological states or processes, reducing redundancy and simplifying interpretation [14].

WikiPathways: As a wiki-based platform, WikiPathways leverages the power of community curation to keep pathways current with the latest research. This model allows for rapid updates and the creation of highly specialized pathways that might not be available in other databases. The platform provides detailed curation guidelines to ensure the quality and consistency of its content [25] [12].

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Enrichment Analysis

This section provides detailed methodologies for performing enrichment analysis using both ORA and GSEA approaches, which represent the two primary paradigms in the field.

Protocol A: Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) with g:Profiler

ORA is used when the input is a flat, unordered list of genes, typically a set of significantly differentially expressed genes.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ORA with g:Profiler

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Input Gene List | A list of significant genes (e.g., DEGs). | A single-column text file with gene identifiers (HGNC symbols, Ensembl IDs, etc.). |

| Background Gene Set | The set of all genes considered in the experiment. | Often implied by the tool; can be set to all genes in the genome. |

| Pathway Gene Sets (GMT File) | The database of pathways used for the enrichment test. | A GMT file containing pathways from GO, Reactome, etc. [20]. |

| g:Profiler Web Tool | The ORA software tool for performing the analysis. | Accessible at http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/ [20]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Prepare Input Data: Compile your list of significant genes (e.g., differentially expressed genes with p-value < 0.05) into a single-column plain text file. Ensure gene identifiers are consistent with the database being used (e.g., HGNC symbols) [20].

Access g:Profiler: Open a web browser and navigate to the g:Profiler website (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/) [20].

Input Data and Set Parameters:

- Paste the gene list into the "Query" field.

- Check the box for "Ordered query" if your list is ranked.

- Check "No electronic GO annotations" to increase result reliability.

- Click "Show Advanced Options" [20].

Configure Advanced Options:

- Data Sources: In the legend, select the pathway databases for the analysis. For an initial analysis, it is recommended to select Biological Processes (BP) from GO and pathways from Reactome [20].

- Pathway Size Filtering: Set the minimum size of a functional category to

5and the maximum to350. This filters out overly broad pathways and those that are too small for meaningful statistical testing [20]. - Statistical Threshold: Set the "Size of query/term intersection" to

3, meaning a pathway will only be considered if it shares at least 3 genes with your input list [20].

Execute and Retrieve Results:

- Click "g:Profile!" to run the analysis. The results will be displayed as a heatmap.

- To prepare results for visualization in tools like Cytoscape, change the "Output type" to "Generic Enrichment Map (TAB)" and run the analysis again.

- Download the results file in this format for the next steps [20].

Protocol B: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) with the GSEA Software

GSEA is applied when the input is a ranked list of all genes from an experiment, as it does not require a pre-defined significance cutoff.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GSEA

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Ranked Gene List (RNK File) | A genome-wide list of genes ranked by a metric of differential expression. | A two-column text file: Gene ID and ranking metric (e.g., log2 fold-change). |

| Gene Set Database (GMT File) | A collection of gene sets (e.g., from MSigDB) against which the RNK file is tested. | A GMT file from MSigDB or Baderlab [20]. |

| GSEA Desktop Application | The Java-based software used to perform the GSEA algorithm. | Downloaded from the GSEA-MSigDB website [14] [20]. |

| Java Runtime Environment | Required to run the GSEA application. | Version 8 or higher must be installed [20]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Software and Data Setup:

- Install the latest version of Java if not already present.

- Download and launch the GSEA desktop application from the official GSEA-MSigDB website (registration is free) [14] [20].

- Prepare your ranked gene list (.rnk file), a two-column text file where the first column contains gene identifiers and the second contains the ranking metric (e.g., signal-to-noise ratio, fold-change). The file should have a header row starting with

#[20].

Load Data into GSEA:

- In the GSEA application, click "Load Data" in the "Steps in GSEA Analysis" section.

- Use the file browser to select your

.rnkfile and your pathway gene set (.gmt) file. Click "Choose" to load them. A success message will appear once the files are processed [20].

Run GSEA Preranked:

- In the left-hand sidebar, under "Tools," click "Run GSEAPreranked".

- In the form that appears:

- Select your

.rnkfile for the "Gene expression dataset" parameter. - Select your

.gmtfile for the "Gene sets database" parameter. - Leave other parameters at their defaults for an initial run.

- Select your

- Click "Run" to start the analysis [20].

Interpret Results:

- GSEA generates a detailed HTML report. The key result is the Enrichment Score (ES), which reflects the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the top or bottom of your ranked list.

- The report includes Normalized Enrichment Score (NES), which allows for comparison across gene sets, and the False Discovery Rate (FDR),- which indicates statistical significance. An FDR < 0.25 is often considered significant in GSEA [20].

Visualization and Interpretation of Results

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the complex results of an enrichment analysis. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points involved in a typical PEA.

Diagram 1: PEA Workflow and Method Selection

The relationships between core databases, analysis tools, and the biological concepts they represent can be visualized as a network.

Diagram 2: Database and Concept Relationships

Advanced Visualization with Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap

For complex analyses involving many enriched pathways, tools like the EnrichmentMap app for Cytoscape are invaluable. EnrichmentMap creates a network visualization of enrichment results where each node represents a significantly enriched pathway, and edges connect pathways that share a significant number of genes. This helps researchers see functional clusters and themes, such as a large cluster of related immune response pathways, rather than interpreting a long, flat list of results [20].

The major pathway databases—GO, KEGG, Reactome, MSigDB, and WikiPathways—each offer unique content and perspectives, making them collectively indispensable for modern biological research. The choice of database and analytical method (ORA vs. GSEA) should be guided by the specific biological question and the nature of the available data. A well-executed pathway enrichment analysis, following established protocols and leveraging robust visualization, transforms raw gene lists into coherent biological narratives, directly fueling hypothesis generation and accelerating discovery in biomedical research and drug development.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) is a cornerstone bioinformatics method for interpreting the complex data generated by modern omics technologies. By contextualizing long lists of genes, proteins, or metabolites within predefined biological pathways, PEA transforms statistical results into mechanistically meaningful insights [26] [1]. In practice, omics experiments such as RNA sequencing or mass spectrometry-based proteomics generate extensive datasets that quantify molecular abundance across different experimental conditions. The initial analysis typically identifies differentially expressed genes or significantly altered proteins—a molecular signature of the phenomenon under study [1] [27]. PEA then examines these signature molecules against knowledge bases of established biological pathways to determine which cellular processes are statistically overrepresented compared to chance occurrence [26]. This process effectively distills thousands of molecular measurements into a focused set of biologically relevant pathways, enabling researchers to formulate testable hypotheses about underlying mechanisms driving observed phenotypes, from disease progression to treatment response [1].

The fundamental value of PEA lies in its systems-level perspective. Rather than considering individual genes or proteins in isolation, PEA recognizes that cellular functions emerge from complex networks of molecular interactions [27]. For example, while a single differentially expressed gene might hint at relevant biology, the coordinated enrichment of multiple genes operating within the same pathway provides compelling evidence for the pathway's activation or repression [1]. This approach has proven instrumental across diverse applications, from identifying histone and DNA methylation by the polycomb repressive complex as a therapeutic target in childhood brain cancer to unraveling pathway dysregulation in autism spectrum disorder through copy-number variant analysis [1]. As omics technologies continue to evolve, generating increasingly complex and multidimensional data, PEA remains an essential tool for extracting biological insight from molecular signatures.

Core Methodologies and Statistical Foundations

Pathway enrichment analysis encompasses several distinct methodological approaches, each with specific statistical foundations and optimal use cases. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for selecting appropriate analytical strategies for different omics data types and research questions. The three primary categories of PEA methods include over-representation analysis, functional class scoring, and pathway topology-based approaches, each with particular strengths and considerations for implementation [26].

Over-representation analysis (ORA), the most established approach, tests whether genes of interest are overrepresented in predefined pathway gene sets more than would be expected by chance [26] [1]. ORA typically uses hypergeometric, chi-square, or Fisher's exact tests to calculate statistical significance, comparing the proportion of pathway genes in the target list against their proportion in a appropriate background set [26]. While straightforward to implement and interpret, ORA has limitations including dependence on arbitrary significance thresholds for creating gene lists and disregard for gene interactions and pathway topology [26]. Functional class scoring (FCS) methods, such as Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), address some limitations by considering all measured genes ranked by their association with a phenotype rather than relying on arbitrary thresholds [1]. FCS methods evaluate whether members of a gene set tend to appear toward the top or bottom of the ranked list, identifying pathways where coordinated but potentially subtle changes might be biologically important [1]. Topology-based methods incorporate information about pathway structure, including the positions of genes within pathways and their relationships, to provide more biologically contextualized enrichment scores [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Pathway Enrichment Analysis Methodologies

| Method Type | Statistical Approach | Key Advantages | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over-representation Analysis (ORA) | Hypergeometric, Fisher's exact tests | Simple implementation, intuitive interpretation, works with simple gene lists | g:Profiler, DAVID |

| Functional Class Scoring (FCS) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistics | Uses full gene rankings, no arbitrary thresholds, detects subtle coordinated changes | GSEA, GSVA |

| Pathway Topology-Based | Impact analysis incorporating pathway structure | Accounts for gene interactions and positions, more biological context | PathwayMapper, SPIA |

The statistical rigor of PEA requires careful consideration of multiple testing correction, as thousands of pathways are typically tested simultaneously [1]. Without appropriate correction, false positive results become likely. Common correction methods include Bonferroni (stringent) and Benjamini-Hochberg (false discovery rate) approaches [1] [27]. Additionally, proper definition of the background gene set is essential, as it represents the universe of possible genes from which the target list was drawn [26]. For RNA-seq experiments, this should typically include all genes detected above a minimum expression threshold, rather than the entire genome [26].

Experimental Design and Workflow Implementation

Implementing a robust pathway enrichment analysis requires careful attention to experimental design and computational workflow. The following diagram illustrates the standard PEA workflow, from raw omics data processing through biological interpretation:

Figure 1. Standard PEA workflow from data to interpretation

Stage 1: Input Preparation from Omics Data

The initial stage involves processing raw omics data into a gene list suitable for enrichment analysis. For RNA-seq data, this typically includes quality control, read alignment, quantification, and differential expression analysis to identify genes associated with the experimental condition [1]. The resulting output can be either a simple list of significant genes (e.g., FDR < 0.05 and fold-change > 2) or a ranked list of all genes sorted by a measure of association with the phenotype (e.g., t-statistic or fold-change) [1]. Proper definition of the background set is crucial—it should reflect all genes detectable in the experimental system, as this represents the statistical universe from which the gene list was drawn [26]. For example, in an RNA-seq experiment, the background should include all genes expressed above a minimum threshold across samples, rather than the entire genome [26].

Stage 2: Database Selection and Enrichment Calculation

Selecting appropriate pathway databases significantly influences PEA results. Commonly used resources include Gene Ontology (GO) for biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components; Reactome for detailed human biological pathways; Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) for curated gene sets; and KEGG for metabolic and signaling pathways [1]. The emerging Pathway Figure OCR (PFOCR) database offers exceptional breadth, covering 77% of human genes through automated extraction of pathway figures from literature, providing unique depth with multiple pathway instances for biological processes typically represented by single canonical pathways in other databases [4]. Each database has distinct strengths—GO offers extensive coverage, Reactome provides mechanistic detail, while PFOCR excels in disease-specific pathway diversity [4].

Stage 3: Results Interpretation and Visualization

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting PEA results, which often include dozens of significantly enriched pathways. Enrichment maps create network visualizations where nodes represent enriched pathways and edges indicate gene overlap, helping identify broader biological themes [1] [27]. The Hyperpathway tool introduces innovative hyperbolic embedding of pathway-molecule bipartite networks, where radial positions indicate hierarchical importance and angular positions reflect functional similarity, effectively revealing modular organization of biological processes [27]. Directional enrichment methods like DPM (Directional P-value Merging) incorporate directional relationships between omics layers, such as the expected negative correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression, to prioritize genes with consistent directional changes across datasets [19].

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Multi-omics Integration

Pathway enrichment analysis has evolved to address the challenges and opportunities presented by multi-omics experiments. The DPM (Directional P-value Merging) method enables directional integration of multiple omics datasets by incorporating user-defined constraints based on biological relationships between data types [19]. For example, when integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data, researchers can specify an expected positive correlation between mRNA and protein expression, prioritizing genes with consistent up- or down-regulation across both molecular layers while penalizing those with discordant directions [19]. This approach increases power to detect coordinated biological events while filtering out inconsistent signals. The method can be represented as:

Figure 2. Directional multi-omics data integration

For complex longitudinal omics studies, linear mixed models (LMM) and generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) account for within-subject correlations and time-varying covariates, enabling identification of pathways with dynamic activity patterns over time [28]. These approaches are particularly valuable in clinical development for tracking pathway modulation in response to therapeutic interventions.

Machine Learning Enhancement

Machine learning (ML) approaches are increasingly integrated with pathway analysis to handle the high-dimensional, nonlinear relationships prevalent in multi-omics data [29]. ML models can capture complex interactions between pathway components that traditional statistical methods might miss, potentially improving prediction accuracy for clinical endpoints [29]. In vaccine development, multi-omics data integration using ML frameworks like MOFA has identified key pathway signatures correlated with immunogenicity, informing vaccine design and efficacy assessment [30]. The combination of ML and pathway enrichment creates a powerful framework for biomarker discovery and mechanism elucidation, particularly for complex traits like disease resistance in crops or drug response in oncology [29] [31].

Table 2: Pathway-Centric Machine Learning Applications in Biology

| Application Domain | ML Approach | Pathway Integration | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Improvement | Random Forest, Multilayer Perceptron | Multi-trait performance pathways | Identification of climate-resilient genotypes [31] |

| Vaccine Development | MOFA, Stabl Algorithms | Immune response pathways | Prediction of immunogenicity and vaccine response [30] |

| Disease Resistance | Multi-omics ML integration | Plant-pathogen interaction pathways | Accurate prediction of resistance mechanisms [29] |

| Cancer Subtyping | Classification algorithms | Cancer hallmark pathways | Improved subtype prediction and biomarker discovery [4] |

Single-Cell and Spatial Resolution

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics technologies has necessitated adaptation of PEA methods to address data sparsity and cellular heterogeneity [32]. GSDensity represents a novel pathway-centric approach that bypasses conventional clustering by directly evaluating pathway activity heterogeneity across cells using graph-based modeling [32]. This method projects both cells and genes into a shared latent space using multiple correspondence analysis, then quantifies pathway coordination through kernel density estimation of pathway genes in this space [32]. For spatial transcriptomics, GSDensity calculates spatially weighted pathway activity, identifying pathways with non-random spatial expression patterns that may reflect tissue organization and cell-cell communication networks [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of pathway enrichment analysis requires both computational tools and conceptual understanding of key resources. The following table summarizes essential components of the PEA research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Pathway Enrichment Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Databases | Gene Ontology, Reactome, KEGG, WikiPathways, PFOCR | Provide curated gene-pathway associations | Coverage, curation quality, update frequency [1] [4] |

| Enrichment Tools | g:Profiler, GSEA, Enrichr, clusterProfiler | Perform statistical enrichment calculations | Method suitability, visualization options [1] |

| Visualization Platforms | Cytoscape, EnrichmentMap, Hyperpathway | Visualize results and pathway relationships | Interpretability, customization options [1] [27] |

| Multi-omics Integrators | DPM, ActivePathways, MOFA | Combine multiple omics datasets | Directional constraints, data compatibility [19] |

| Specialized Environments | GSDensity (single-cell), Longitudinal LMM | Handle specific data types and designs | Accounting for data structure and dependencies [32] [28] |

Pathway Enrichment Analysis has evolved from a simple over-representation method to a sophisticated framework for biological mechanism elucidation. By contextualizing omics signatures within known biological processes, PEA bridges the gap between statistical associations and testable hypotheses about underlying biology. The continuing development of directional integration methods for multi-omics data, ML-enhanced pathway analysis, and specialized approaches for emerging technologies like single-cell and spatial transcriptomics ensures that PEA will remain an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking mechanistic insights from complex biological data. As pathway resources continue to expand in both breadth and depth, and analytical methods become increasingly refined, the power of PEA to reveal meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional data will only continue to grow.

Executing PEA: A Step-by-Step Guide to Methods and Real-World Applications

Pathway enrichment analysis is a cornerstone of modern computational biology, providing researchers with a powerful method to extract mechanistic insight from large-scale omics data. By interpreting gene lists generated from genome-scale experiments (e.g., RNA-seq, proteomics) in the context of existing biological knowledge, this approach helps identify underlying biological processes, pathways, and molecular functions that are systematically altered in a given condition [1]. The core premise is to determine whether defined sets of genes, representing specific pathways or biological themes, are over-represented in an experimental gene list more than would be expected by chance [1] [2]. This technique has proven invaluable in diverse applications, from identifying rational therapeutic targets in childhood brain cancers to unraveling the complex genetics of neurodevelopmental disorders [1]. Over time, the methodologies have evolved from simple over-representation tests to more sophisticated frameworks that incorporate gene expression magnitudes and, most recently, pathway topology, each paradigm offering distinct advantages and addressing specific analytical challenges [33] [34].

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

- Pathway: A series of interactions among molecules in a cell that leads to a certain product or a change in the cell. Pathways are models describing the interactions of genes, proteins, or metabolites within cells, tissues, or organisms, not simple lists of genes [3].

- Gene Set: An unordered and unstructured collection of genes formed on the basis of shared biological or functional properties as defined by a reference knowledge base [2] [13].

- Gene List of Interest: The list of genes derived from an omics experiment that serves as input to pathway enrichment analysis [1].

- Ranked Gene List: In many omics datasets, genes can be ranked according to a score (e.g., level of differential expression) to provide more information for pathway enrichment analysis [1].

- Multiple Testing Correction: A statistical technique to correct the P values from individual enrichment tests to reduce the chance of false-positive enrichment, necessary when thousands of pathways may be individually tested [1].

The Three Analytical Paradigms

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA)

Core Principle and Workflow Over-representation Analysis represents the first generation of pathway analysis methods. ORA statistically evaluates the fraction of genes in a particular pathway found among a set of genes showing significant changes in expression, typically determined by an arbitrary threshold [2] [13]. The method operates by asking a straightforward question: "Are there more annotations in the gene list than expected by chance?" [2]

The standard ORA workflow involves three key steps:

- Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs): From the full dataset, select genes that meet specific significance thresholds (e.g., adjusted p-value < 0.05 and fold-change > 2) [35].

- Check for Pathway Over-Representation: For each predefined gene set (pathway), examine whether the DEGs are disproportionately represented compared to a background set [35].

- Perform Statistical Testing: Calculate the probability (p-value) that the observed overlap between DEGs and pathway genes occurred by chance using statistical tests like Fisher's exact test or hypergeometric distribution [35].

Mathematical Foundation and Key Assumptions ORA methods typically employ tests based on hypergeometric, Fisher's exact, chi-square, or binomial distributions [2]. These tests determine the probability that the number of genes in a experimental gene list found in a given gene set would be observed by chance, considering the size of the pathway and the background gene set [2]. A crucial requirement for ORA is defining an appropriate background gene set for comparison, which could include all genes in the organism, all protein-coding genes, only genes measured on a specific platform, or only genes expressed in the experiment [2]. The method assumes independence between genes, a condition that rarely holds true in biological systems where genes often function in coordinated networks [13].

Table 1: Characteristics of Over-Representation Analysis (ORA)

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Statistical Test | Hypergeometric test, Fisher's exact test [2] |

| Input Requirements | List of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on arbitrary threshold [13] |

| Key Assumptions | Gene independence; appropriate background definition [2] |

| Strengths | Conceptually easy to understand; fast computation; requires only gene identifiers, not full dataset [2] [35] |