qPCR Validation for Transcriptomics: When It's Required and When It's Not

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the role of qPCR validation in transcriptomics studies.

qPCR Validation for Transcriptomics: When It's Required and When It's Not

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the role of qPCR validation in transcriptomics studies. With the rise of RNA-seq as the primary tool for gene expression profiling, the necessity of orthogonal validation with qPCR is frequently debated. We synthesize current evidence and expert recommendations to outline clear scenarios where qPCR validation is essential—such as when a study's conclusions hinge on a few key genes with small expression changes or low expression levels—and situations where it may be redundant. The article also delivers a robust methodological framework for selecting stable reference genes, designing and validating qPCR assays, and troubleshooting common pitfalls to ensure rigor and reproducibility in gene expression analysis.

The Great Validation Debate: Is qPCR Still Necessary in the RNA-seq Era?

Gene expression profiling represents a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex mechanisms underlying health and disease. The evolution of this field has been marked by two dominant technological paradigms: microarray hybridization and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Each technology has brought distinct advantages and challenges, particularly regarding the need for validation of results using orthogonal methods like quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Historically, qPCR validation was considered an essential step for confirming transcriptomic data, a practice that originated during the microarray era due to technological limitations of early platforms [1]. However, with the advent and maturation of RNA-seq, the scientific community has been compelled to re-evaluate this requirement, moving toward a more nuanced, context-dependent approach.

This evolution reflects a broader shift in transcriptomics from targeted gene expression analysis to comprehensive, discovery-driven science. The question of when qPCR validation is required now demands a sophisticated understanding of experimental goals, methodological robustness, and the intended use of the generated data. This review examines the technical foundations of this transition, assesses the current state of validation requirements, and provides evidence-based guidance for researchers navigating transcriptomic validation in the age of RNA-seq.

Technological Foundations: From Hybridization to Sequencing

Microarray Technology and Its Limitations

Microarray technology revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling simultaneous measurement of thousands of pre-defined transcripts. The methodology relies on hybridization-based detection, where fluorescently labeled cDNA from experimental samples binds to complementary DNA probes fixed on a solid surface [2]. The signal intensity at each probe location correlates with the abundance of the corresponding transcript. Despite its transformative impact, this approach suffered from several inherent limitations that necessitated rigorous validation.

Key constraints included a limited dynamic range (approximately 3.6×10³) due to background noise at low expression levels and signal saturation at high abundances [2]. Furthermore, microarrays were restricted to detecting only known sequences for which probes had been designed, preventing discovery of novel transcripts or isoforms [3]. Cross-hybridization artifacts, where closely related sequences bound to the same probe, also compromised specificity and accuracy [1]. These technical shortcomings created widespread skepticism about microarray data reliability, establishing qPCR validation as a de facto requirement for publication.

The RNA-seq Revolution

RNA-seq represents a fundamental shift from hybridization-based to sequencing-based transcriptome assessment. This next-generation sequencing technology involves converting RNA into a library of cDNA fragments, followed by high-throughput sequencing to generate short reads that are computationally mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome [3]. Digital quantification of these mapped reads provides a direct measure of transcript abundance.

This approach offers several transformative advantages. RNA-seq boasts a vastly expanded dynamic range (>10⁵), enabling accurate quantification of both lowly and highly expressed genes from the same sample [2]. It provides unbiased detection of any transcribed sequence, including novel genes, splice variants, fusion transcripts, and non-coding RNAs [4]. The technology also demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity, particularly for genes with low expression levels [3]. These technical improvements have fundamentally altered the validation paradigm, as RNA-seq data often demonstrates sufficient intrinsic reliability for many applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Microarray and RNA-Seq Technical Capabilities

| Feature | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-based |

| Dynamic Range | ~3.6×10³ [2] | >2.6×10⁵ [2] |

| Transcript Discovery | Limited to pre-designed probes | Unbiased; detects novel transcripts [3] |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | Lower; suffers from cross-hybridization | Higher; digital quantification [3] |

| Input RNA Requirement | Higher | Lower (can work with ≤100 ng total RNA) [5] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; simpler analysis | Higher; requires specialized bioinformatics [2] |

The Validation Debate: Evidence-Based Perspectives

The Microarray Era: Mandatory Validation

During the peak of microarray utilization, validation with qPCR was considered essential due to persistent concerns about reproducibility and technical artifacts [1]. Studies consistently revealed discrepancies between microarray results and other expression measures, with some reports indicating that up to 30% of differentially expressed genes identified by microarrays could not be confirmed by qPCR. This validation deficit stemmed from the fundamental limitations of hybridization kinetics, probe design flaws, and the technology's constrained ability to detect subtle expression changes, especially for low-abundance transcripts.

The microarray validation paradigm typically involved selecting a subset of significant results (often 10-20 genes) for confirmation using qPCR on the same RNA samples. While this approach strengthened confidence in specific findings, it created a circular validation system that primarily verified that both techniques could detect large expression differences rather than establishing absolute accuracy.

RNA-seq Reliability: Rethinking Validation Needs

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have revealed generally high concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR, challenging the notion that universal validation is necessary. A landmark study by Everaert et al. compared five RNA-seq analysis pipelines against qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes [1]. The results demonstrated that only approximately 1.8% of genes showed severe non-concordance (defined as opposing differential expression directions or disagreement on statistical significance), with these problematic genes typically being shorter and expressed at lower levels [1].

Another systematic evaluation found that approximately 85% of genes showed consistent fold-change measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR across multiple analysis workflows [6]. The small subset of genes with inconsistent results (15-20%) predominantly exhibited low fold changes (<2) and low expression levels, suggesting that discordance primarily affects genes with minimal biological impact or borderline statistical significance [6].

Table 2: Concordance Between RNA-seq and qPCR in Differential Expression Analysis

| Concordance Metric | Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | ~85% of genes show consistent DE calls between RNA-seq and qPCR [6] | High general reliability of RNA-seq |

| Severe Non-concordance | ~1.8% of genes show opposing DE directions [1] | Affects small subset of genes |

| Non-concordant Features | 93% have fold change <2; 80% have fold change <1.5 [1] | Discordance primarily affects genes with small expression changes |

| Problematic Genes | Typically shorter, lower expressed genes [1] [6] | Technical rather than biological limitations |

Contemporary Validation Guidelines

The current scientific consensus, reflected in recent editorial recommendations, suggests that RNA-seq data generated with sufficient biological replication and state-of-the-art methodologies may not require routine qPCR validation [1]. However, specific scenarios still warrant orthogonal verification:

- Critical Gene Validation: When research conclusions hinge on expression patterns of a small number of genes, particularly those with low expression levels or small fold changes [1].

- Insufficient Replication: Studies with limited biological replicates that preclude robust statistical analysis [7].

- Extended Experimental Validation: Using qPCR to confirm key findings in additional samples, conditions, or model systems not included in the original RNA-seq experiment [1].

- Methodological Comparisons: When introducing novel RNA-seq protocols or analysis pipelines, where benchmarking against established methods is prudent [6].

This evolving perspective represents a significant shift from the mandatory validation culture of the microarray era toward a more nuanced, context-dependent approach that recognizes the inherent reliability of properly executed RNA-seq studies.

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

RNA-seq Experimental Workflow

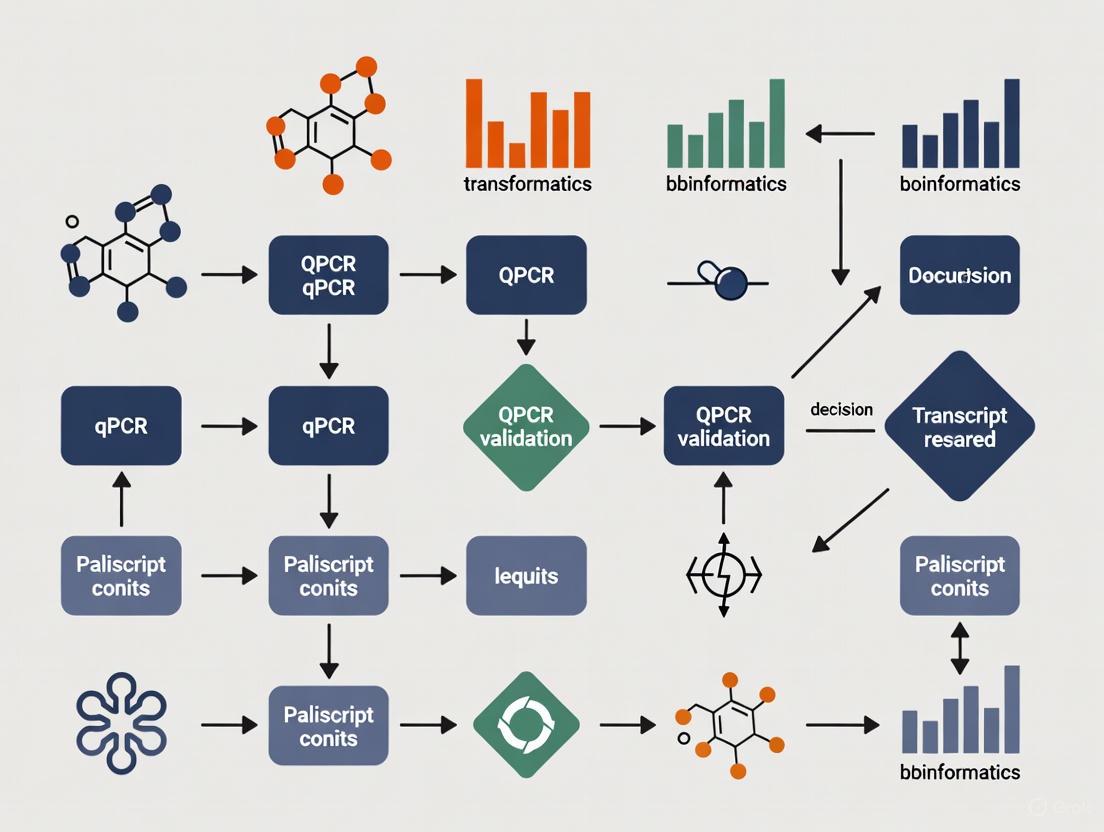

Diagram 1: RNA-seq workflow with optional validation

qPCR Experimental Design and Validation Guidelines

For studies requiring qPCR validation, rigorous experimental design is essential to ensure meaningful results. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for conducting and reporting qPCR experiments [1]. Key considerations include:

- RNA Quality: Use RNA with high integrity (RIN > 8.0) and verify quality using appropriate methods [5].

- Reverse Transcription: Employ consistent priming methods (oligo-dT vs. random hexamers) across all samples to minimize technical variability.

- Assay Design: Ensure high amplification efficiency (90-110%) and specificity for each qPCR assay through proper validation [8].

- Reference Gene Selection: Identify and use multiple stable reference genes appropriate for the specific experimental context, as traditional "housekeeping" genes may exhibit variable expression [9].

When designing validation experiments, it is critical to use independent biological samples rather than simply repeating measurements on the same RNA used for sequencing. This approach confirms both the technical accuracy and biological reproducibility of findings [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Transcriptomic Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA | Include DNase treatment; assess RIN [5] |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Strand-specificity; ribosomal RNA depletion [5] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification and detection | Efficiency validation; compatible with detection chemistry [8] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA | Consistent priming method; high efficiency [8] |

| Reference Genes | Normalization of qPCR data | Stability across experimental conditions; multiple genes [9] |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Evaluation of RNA integrity | RIN measurement; spectrophotometric analysis [5] |

Application Contexts and Future Perspectives

Context-Dependent Validation Strategies

The decision to validate RNA-seq results varies significantly across research contexts:

- Exploratory/Discovery Research: When RNA-seq serves as a hypothesis-generating tool to identify candidate genes or pathways for further investigation, validation may be unnecessary as subsequent functional studies will naturally confirm key findings [7].

- Clinical Biomarker Development: In diagnostic or prognostic applications where results directly impact patient management, rigorous validation using independent cohorts and orthogonal methods remains essential [8].

- Regulatory Toxicology: For applications like transcriptomic benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling in chemical risk assessment, both microarray and RNA-seq show comparable performance in identifying points of departure, suggesting platform choice may not significantly impact outcomes [5].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field continues to evolve with several emerging trends influencing validation practices:

- Single-Cell RNA-seq: The unique technical challenges of single-cell sequencing, including sparsity and amplification bias, may necessitate renewed emphasis on validation for specific applications.

- Third-Generation Sequencing: Long-read technologies offer improved isoform resolution but present distinct analytical challenges that may require specialized validation approaches.

- Multi-Omics Integration: As transcriptomic data increasingly integrates with other molecular profiling techniques, validation may shift toward confirming systems-level biological models rather than individual gene expression changes.

The evolution from microarrays to RNA-seq has fundamentally transformed transcriptomic validation requirements. While qPCR remains a valuable tool for specific applications, reflexive validation of all RNA-seq findings is no longer scientifically justified. Instead, researchers should adopt a context-dependent approach that considers experimental goals, methodological rigor, and intended applications. As transcriptomic technologies continue to advance, validation practices will likely continue evolving toward integrated quality assessment throughout the entire experimental workflow rather than focusing solely on post-hoc confirmation of results.

In the field of transcriptomics, RNA-seq has emerged as a powerful tool for profiling gene expression on a genome-wide scale. However, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating results due to its superior sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. The question of how often these two techniques produce concordant results is not merely technical—it strikes at the heart of experimental reliability. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the frequency and causes of divergence is critical for determining when qPCR validation is an essential step in the research pipeline. This article examines the evidence behind RNA-seq and qPCR concordance, explores the technical factors driving discrepancies, and provides a framework for deciding when validation is necessary.

Quantitative Comparison: How Well Do RNA-seq and qPCR Agree?

Direct head-to-head comparisons reveal that the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR is variable and influenced by multiple factors. A 2023 study focusing on the challenging human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I genes—notorious for their extreme polymorphism—found only a moderate correlation between expression estimates derived from qPCR and RNA-seq. The reported Spearman's correlation coefficients (rho) ranged from 0.2 to 0.53 for HLA-A, -B, and -C genes [10]. This indicates that for complex gene families, results can frequently diverge.

A broader assessment comes from a 2020 systematic comparison study, which validated RNA-seq findings for 32 genes using qPCR. This research concluded that RNA-seq offers a "high degree of agreement" with qPCR, but it also highlighted that the specific computational pipeline used to analyze RNA-seq data significantly impacts the accuracy of the final results [11]. The following table summarizes key comparative findings:

Table 1: Key Findings from RNA-seq and qPCR Concordance Studies

| Study Focus | Reported Correlation | Main Factors Influencing Concordance |

|---|---|---|

| HLA Class I Gene Expression [10] | Moderate (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) | Extreme genetic polymorphism of HLA genes. |

| Gene Expression in Cell Lines [11] | High degree of agreement | Algorithm choice for alignment, counting, and differential expression. |

| Differential Expression Calls [12] | Varies with experimental design | Biological effect size, number of replicates, and statistical method used. |

Beyond overall correlation, the reliability of detecting differential expression (DE) is a key metric. Research shows that the concordance in DE calls is heavily dependent on biological effect size and replicate number. When the biological effect is strong (i.e., large fold-changes in gene expression), methods like NOISeq and GFOLD can effectively identify DEGs for validation even in unreplicated experiments. However, when the effect size is mild, RNA-seq experiments require at least triplicate samples to yield DEG candidates with a good potential for qPCR validation [12].

Methodological Foundations: Why Do the Techniques Diverge?

Understanding the sources of divergence requires a closer look at the technical and analytical underpinnings of each method.

Technical and Analytical Biases in RNA-seq

The process of converting RNA into measurable digital data introduces multiple potential sources of bias that are absent in qPCR. These include:

- Alignment and Mapping Issues: The short reads generated by RNA-seq must be aligned to a reference genome. This process is problematic for genes with high polymorphism (like HLA genes) or those with high similarity to paralogous genes, leading to misalignment and inaccurate quantification [10].

- Normalization Challenges: RNA-seq relies on statistical normalization to account for technical variations in library size and composition. These global normalization strategies can be skewed by a few highly expressed genes and do not always correct accurately for every transcript [13].

- Transcript-Length Bias: Longer transcripts generate more reads, which can lead to over-estimation of their abundance compared to shorter transcripts, independent of their actual expression level [13].

The qPCR Standard and Its Demands

While qPCR is less susceptible to the biases above, its accuracy is entirely contingent on proper experimental design.

- Reference Gene Selection: The use of inappropriate, unstable reference genes for normalization is a major source of error and irreproducibility in qPCR [8] [14]. Traditionally, housekeeping genes like GAPDH and ACTB were used, but it is now understood that their expression can vary significantly across different tissues and experimental conditions [15] [16].

- Assay Validation: The lack of technical standardization for qPCR-based tests is a significant obstacle to their clinical application and reliable research use. This includes variable RNA quality, cDNA synthesis efficiency, and primer design [8].

A Roadmap for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

Given the potential for divergence, a structured workflow is essential for deciding when and how to employ qPCR validation. The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to ensure the reliability of transcriptomics data, from experimental design to final validation.

Decision Factors for qPCR Validation

The decision to validate RNA-seq findings with qPCR should be guided by the following criteria:

- Goal of the Study: Is the aim to generate a systems-level hypothesis (where a list of DEGs is used for pathway analysis) or to confirm the specific behavior of a handful of key genes? For the former, rigorous RNA-seq with sufficient replication may be adequate. For the latter, qPCR validation is often required [12].

- Strength of the Biological Signal: Genes with very high fold-changes are more likely to be validated successfully. Findings centered on genes with mild but statistically significant expression changes require qPCR confirmation [12].

- Number of Biological Replicates: Studies with few or no biological replicates have low statistical power and are highly prone to false discoveries. Any DEGs from such studies must be validated [12].

- Nature of the Target Genes: Genes in complex genomic regions, such as the HLA locus or other gene families with high sequence similarity, are prone to quantification errors in RNA-seq and warrant qPCR validation [10].

Best Practices for Experimental Design and Validation

Designing a Robust RNA-seq Experiment

To maximize the initial reliability of RNA-seq data and minimize the need for extensive validation, consider these protocols derived from systematic assessments [11] [12]:

- Incorporate Biological Replicates: A minimum of triplicate samples per condition is essential for statistical power. The number of replicates is more critical than sequencing depth.

- Utilize a Trim-Galore-Correct Pipeline: Implement a rigorous bioinformatic workflow that includes:

- Trimming: Use tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases.

- Alignment: Choose an aligner (e.g., STAR, HISAT2) appropriate for your organism and reference genome.

- Gene Counting: Employ featureCounts or HTSeq to assign reads to genes.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Select a DEG tool matched to your experiment. For low-replicate studies, GFOLD or NOISeq are recommended; for well-replicated studies, DESeq2 or edgeR are robust choices [12].

Executing a Credible qPCR Validation

The following protocols are essential for generating reliable qPCR data [8] [14] [17]:

- Select Stable Reference Genes: Do not rely on traditional housekeeping genes without confirmation. Use RNA-seq data itself with tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) to identify genes with stable, high expression across your specific conditions [14]. Alternatively, use statistical algorithms like RefFinder (which integrates geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the Delta-Ct method) on qPCR data to validate the stability of candidate reference genes [15] [9].

- Validate Assay Performance: For each primer pair, confirm a single, specific amplification product via melt curve analysis and ensure amplification efficiency is between 90% and 110% [9] [17].

- Follow Reporting Guidelines: Adhere to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of your results [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and tools referenced in the literature for conducting these analyses.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Transcriptomics Validation

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic/Cutadapt [11] | Bioinformatics Tool | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases from RNA-seq raw reads to improve mapping rates. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR [12] | Bioinformatics Tool | Statistical software for differential expression analysis from RNA-seq count data in well-replicated experiments. |

| NOISeq / GFOLD [12] | Bioinformatics Tool | Algorithms for differential expression analysis effective with low or no biological replicates. |

| Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) [14] | Bioinformatics Tool | Identifies optimal, stable reference genes for qPCR directly from RNA-seq TPM data. |

| RefFinder [15] | Web Tool / Algorithm | Comprehensively ranks candidate reference genes by integrating results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and Delta-Ct. |

| Stable Reference Genes (e.g., ARD2, VIN3 in tomato [17]) | Biological Reagent | Species- and context-specific genes verified for stable expression, crucial for accurate qPCR normalization. |

| PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit [16] | Laboratory Kit | High-efficiency cDNA synthesis from RNA templates, a critical step for both RNA-seq and qPCR. |

The question of how often RNA-seq and qPCR results diverge does not have a single numerical answer. Evidence shows that while a high degree of agreement is possible, divergence is a frequent occurrence, particularly when studying genes with mild expression changes, when experimental design is suboptimal (e.g., low replication), or when analyzing genetically complex regions.

Therefore, qPCR validation remains a cornerstone of rigorous transcriptomics research. It is required when research aims to make definitive claims about the expression of specific candidate genes, especially when these findings inform downstream applications in drug development or clinical decision-making. For researchers, the strategic approach is not to view RNA-seq and qPCR as competing technologies, but as complementary parts of a pipeline where discovery is followed by rigorous, targeted confirmation.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating transcriptomics data, yet many researchers overlook critical red flags that compromise data integrity. This technical guide examines two primary indicators that necessitate rigorous qPCR validation: low expression levels and small fold-changes. We synthesize current evidence demonstrating how genes with low read counts and modest expression differences display poor concordance between RNA sequencing and qPCR results. The article provides detailed methodologies for identifying problematic genes, implementing orthogonal validation strategies, and applying statistical frameworks to distinguish technical noise from biological signal. For researchers and drug development professionals, these evidence-based protocols offer a critical pathway to enhanced reproducibility in gene expression studies, ensuring that conclusions drawn from transcriptomics research withstand scientific scrutiny.

The transition from discovery-based transcriptomics to targeted validation represents a critical juncture in gene expression research. While high-throughput technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provide comprehensive expression profiles, their findings require confirmation through highly sensitive and specific methods. Quantitative PCR has established itself as the preferred validation technology due to its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [1] [14]. However, the decision of when qPCR validation is mandatory remains a nuanced determination based on specific technical and biological parameters.

A growing consensus indicates that not all RNA-seq findings require qPCR confirmation. When RNA-seq experiments are performed with sufficient biological replicates and follow state-of-the-art protocols, the resulting data is generally reliable for most genes [1]. The critical exception arises with specific gene categories prone to technical artifacts or misinterpretation—particularly those with low expression levels or small reported fold-changes. These parameters serve as key indicators that the transcriptomics data may require orthogonal validation before drawing biological conclusions.

The reproducibility crisis in molecular biology has highlighted the consequences of inadequate validation. For instance, in cardiovascular disease biomarker research, numerous studies have reported contradictory results for the same microRNAs, with technical variability identified as a primary contributor to these discrepancies [8]. Such findings underscore the necessity of a strategic approach to validation that prioritizes resources toward the most problematic data points. This guide establishes a framework for identifying these red flags and implementing efficient, reliable validation protocols.

Low Expression Levels: Amplification Challenges and Stochastic Effects

The Technical Limitations of Low-Abundance Transcripts

Genes with low expression levels present particular challenges for both RNA-seq and qPCR technologies, creating a convergence of technical limitations that threaten quantification accuracy. In RNA-seq, low read counts provide insufficient sampling for reliable quantification, while in qPCR, low template concentrations lead to stochastic amplification effects that compromise reproducibility [18].

The fundamental issue stems from molecular sampling statistics. At low concentrations, the random distribution of template molecules across replicate reactions creates substantial variation in amplification kinetics. This stochastic effect manifests as increased variability in quantification cycle (Cq) values, with standard deviations exceeding biologically meaningful differences [18]. When quantifying low-expression genes, this technical noise can easily obscure genuine biological signal, leading to both false positives and false negatives.

Empirical studies demonstrate that the limit of reliable detection for most qPCR assays typically falls between 20-50 copies per reaction, with performance being assay-dependent [18]. Below this threshold, the probability of false negatives increases dramatically, while the precision of quantification deteriorates. This has direct implications for validating RNA-seq findings, as genes with low transcripts per million (TPM) values often fall within this problematic concentration range when analyzed by qPCR.

Identification and Handling of Low-Expression Genes

Table 1: Expression Thresholds for Reliable qPCR Quantification

| Expression Category | TPM Range | Expected Cq Range | Technical Considerations | Validation Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High expression | >100 TPM | <25 | Low variability, high precision | qPCR validation optional with sufficient RNA-seq replicates |

| Medium expression | 20-100 TPM | 25-30 | Moderate variability, acceptable precision | qPCR recommended for definitive confirmation |

| Low expression | 5-20 TPM | 30-35 | Elevated variability, stochastic effects | qPCR essential with increased technical replicates |

| Very low expression | <5 TPM | >35 | High variability, frequent non-detection | Interpretation cautious; consider alternative methods |

Software tools now exist to identify low-expression genes from RNA-seq data before attempting qPCR validation. The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software applies specific filters to exclude genes with average log2(TPM) values below 5, ensuring selected reference and target genes express sufficiently for reliable qPCR detection [14]. This pre-screening step prevents futile validation attempts on genes that fall below the practical quantification limit of qPCR technology.

For genes that must be quantified despite low expression, specialized experimental approaches are necessary. Increasing technical replication to 5-7 replicates, rather than the standard 3, helps account for Poisson noise inherent in low template concentrations [18]. Reaction volumes should be maintained at ≥2.5μL to minimize pipetting error, and template input should be maximized within the assay's linear range [18]. Digital PCR may offer advantages for absolute quantification of rare targets, as its partitioning approach mitigates amplification stochasticity [19].

Small Fold-Changes: Distinguishing Biological Signal from Technical Noise

The Misleading Nature of Modest Expression Differences

Small fold-changes in gene expression present interpretative challenges that frequently necessitate qPCR validation. RNA-seq analysis pipelines demonstrate substantial discordance with qPCR for genes showing less than two-fold differential expression, with approximately 15-20% of genes showing non-concordant results (differential expression in opposing directions or significant in only one method) [1]. Critically, among these non-concordant genes, 80% display fold-changes lower than 1.5, indicating that modest expression differences are particularly prone to technical artifacts.

The interpretation of small fold-changes is further complicated by platform-specific variability. Inter-instrument comparisons reveal that ΔCq values between different qPCR platforms alone can correspond to 2.9-fold expression differences, exceeding the commonly used two-fold threshold for biological significance [18]. This finding underscores that technically derived variability can create the illusion of biologically meaningful expression changes where none exist.

The problem extends to statistical reporting practices. Few studies report confidence intervals for fold-changes, despite the importance of these measures for assessing biological relevance [18]. This reporting gap, combined with arbitrary replicate designs and validation bias, creates an environment where technical noise is frequently mistaken for genuine biological effect.

Methodological Considerations for Small Fold-Change Validation

Table 2: Experimental Design Requirements for Small Fold-Change Detection

| Fold-Change Range | Minimum Biological Replicates | Minimum Technical Replicates | Required CV Threshold | Statistical Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >2-fold | 3-5 | 3 | <25% | Standard deviation, p-values |

| 1.5-2 fold | 5-8 | 3-5 | <20% | 95% confidence intervals, effect size |

| <1.5 fold | 8-12 | 5-7 | <15% | Empirical confidence intervals, power analysis |

Robust experimental design is essential when validating small fold-changes. Statistical power must be increased through additional biological replicates, with 8-12 replicates recommended for detecting differences smaller than 1.5-fold [18]. Technical replication should also increase to 5-7 replicates per sample to better characterize measurement uncertainty [18].

Data normalization requires particular attention with small fold-changes. Traditional reference genes often demonstrate sufficient variation to obscure modest biological effects. A novel approach involves using stable combinations of non-stable genes, where the expression patterns of multiple genes balance each other across experimental conditions [20]. This method has demonstrated superiority over standard reference genes, particularly for detecting subtle expression differences.

The MIQE guidelines emphasize that qPCR data interpretation must include efficiency corrections and statistical measures of variability [21]. When validating small fold-changes, reporting empirically derived confidence intervals is essential for distinguishing reliable quantification from technical noise [18]. Without these rigorous approaches, the validation process itself may introduce sufficient variability to obscure the biological signal it seeks to confirm.

Integrated Experimental Protocols for Reliable Validation

Pre-Validation Bioinformatics Assessment

Before initiating qPCR experiments, a comprehensive bioinformatic assessment of RNA-seq data identifies targets most needing validation. The following workflow provides a systematic approach:

Figure 1: Bioinformatics workflow for identifying genes requiring qPCR validation.

Software tools like GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) automate the identification of problematic genes from transcriptomic data [14]. The tool applies multiple filters, including expression level (TPM > 5), variability between libraries (standard variation of log2(TPM) < 1), and absence of exceptional expression in any single library. This systematic approach identifies both stable reference candidates and highly variable targets requiring confirmation.

For the specific identification of reference genes, a combination approach using RNA-seq data has demonstrated enhanced performance. By finding optimal combinations of genes whose expressions balance each other across experimental conditions, researchers can achieve more reliable normalization than with traditional housekeeping genes [20]. This method leverages comprehensive RNA-seq databases to identify gene combinations with minimal collective variance.

Optimized qPCR Experimental Workflow

Once targets are identified, an optimized qPCR protocol ensures reliable detection of problematic genes:

Figure 2: Optimized qPCR workflow for validating challenging targets.

The wet-lab protocol proceeds as follows:

Sample Preparation and Reverse Transcription

- Extract high-quality RNA (RNA Integrity Number >8) using silica-membrane columns with DNase treatment

- Quantify RNA using fluorometric methods; avoid spectrophotometry due to impurity sensitivity

- Perform reverse transcription using random hexamers and oligo-dT primers (mixed approach)

- Include genomic DNA contamination controls using no-reverse-transcriptase (-RT) controls

- Use uniform RNA input across samples; normalize by RNA quantity rather than cell number [8]

Primer and Probe Design

- Design primers with melting temperatures of 58-60°C and amplicons of 70-150 bp

- Select exon-spanning assays to minimize gDNA amplification

- Validate primer specificity using in silico tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST) followed by empirical testing

- Test a minimum of 3 primer pairs per target to identify optimal performance [19]

- For probe-based detection, select hydrolysis probes with 5' fluorophores and 3' quenchers

- Verify amplification efficiency of 90-110% with R² > 0.99 in standard curves [19]

qPCR Amplification and Data Collection

- Perform reactions in technical replicates of 5-7 for low abundance targets [18]

- Maintain reaction volumes ≥2.5μL to minimize pipetting error [18]

- Include no-template controls (NTCs) and inter-run calibrators for plate-to-plate normalization

- Use a two-step amplification protocol with combined annealing/extension at 60°C

- Determine Cq values using derivative or curve-fitting methods rather than fixed thresholds

This comprehensive protocol addresses the major sources of variability in qPCR experiments, providing a foundation for reliable validation of transcriptomics findings.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function and Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Silica-membrane columns with DNase treatment | High-quality RNA extraction with genomic DNA removal | Essential for RNA integrity; required for MIQE compliance |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Mixed random hexamer/oligo-dT primers | cDNA synthesis with balanced 5' and 3' representation | Includes gDNA removal enzymes |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Probe-based or SYBR Green chemistry | Fluorescent detection of amplification | Probe-based offers better specificity; SYBR Green is more economical |

| Reference Gene Assays | Multi-analyte reference gene panels | Normalization of technical variability | Require prior stability validation across experimental conditions |

| Pre-Designed Assays | Commercial primer-probe sets | Standardized amplification assays | Ensure compatibility with chosen detection chemistry |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation | RNA integrity verification | RIN >8.0 required for reliable results |

| Digital PCR Systems | Droplet digital PCR, chip-based dPCR | Absolute quantification without standard curves | Particularly valuable for low-copy targets |

Low expression levels and small fold-changes serve as critical red flags in transcriptomics research that warrant thorough qPCR validation. The convergence of technical limitations in both RNA-seq and qPCR technologies at low abundance levels creates a reproducibility risk that researchers must actively address. Similarly, small fold-changes near the technical noise threshold of both platforms require rigorous experimental design and statistical treatment to distinguish biological signal from technical artifact.

By implementing the bioinformatic screening and optimized experimental protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can prioritize their validation efforts effectively. The integration of systematic pre-validation assessment, enhanced replicate strategies, appropriate reference gene selection, and comprehensive statistical reporting creates a robust framework for confirmatory gene expression studies. These practices ensure that the considerable investment in transcriptomics research yields biologically meaningful and reproducible insights rather than technical artifacts.

As molecular technologies continue to evolve, the principles of rigorous validation remain constant. The strategic application of qPCR validation to the most problematic findings from discovery transcriptomics represents a scientifically sound and resource-efficient approach to gene expression analysis. Through heightened attention to low expression levels and small fold-changes, the research community can advance biological understanding while maintaining the highest standards of methodological rigor.

In transcriptomics research, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating gene expression data due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [14] [22]. However, not all studies require the same level of assay validation. The context of use (COU)—a structured framework detailing what is being measured, the clinical or research purpose, and how the results will be interpreted—directly determines the necessary rigor and scope of qPCR validation [8]. Adhering to a fit-for-purpose (FFP) principle ensures that the validation level is sufficient to support the specific objectives of a study, whether it is basic research or informing clinical decisions [8]. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured approach to aligning qPCR validation with their study's context of use.

Defining Context of Use and Its Impact on Validation Strategy

The context of use is a formal definition that specifies the intended application of an assay or biomarker. According to consensus guidelines, COU elements include: (1) the specific aspect of the biomarker being measured and its form, (2) the clinical or research purpose of the measurements, and (3) the interpretation and decision-making actions based on those measurements [8]. The validation requirements for a qPCR assay will vary significantly depending on whether the goal is to publish preliminary research findings or to support a clinical trial endpoint.

The fit-for-purpose concept is central to this process. It is "a conclusion that the level of validation associated with a medical product development tool (assay) is sufficient to support its COU" [8]. This means that the analytical and clinical performance characteristics you validate should be tailored to your study's goals. For example, an assay used for absolute quantification of viral vector copies in a gene therapy biodistribution study demands a more stringent validation than one used for relative quantification of a candidate gene's expression in a preliminary research screen [23].

Table: Alignment of Context of Use with qPCR Validation Rigor

| Context of Use (COU) Category | Typical Application | Required Validation Level | Key Performance Parameters to Establish |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Use Only (RUO) | Discovery-phase research, preliminary biomarker identification, target validation [8]. | Basic assay optimization. | Specificity, amplification efficiency, dynamic range [24]. |

| Clinical Research (CR) Assays | Biomarker validation in clinical trials, patient stratification, therapeutic monitoring [8]. | Rigorous, FFP validation to bridge the gap between RUO and IVD. | Analytical specificity/sensitivity, precision, accuracy, robustness, LOD, LOQ [8] [23]. |

| In Vitro Diagnostics (IVD) | Clinical decision-making, diagnosis, prognosis [8]. | Full regulatory validation compliant with IVDR or FDA guidelines. | All analytical parameters plus extensive clinical validation (diagnostic sensitivity/specificity, PPV, NPV) [8]. |

Core Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

A qPCR assay's performance is characterized by a set of core parameters. The extent to which each parameter is formally validated depends on the COU. The following section details key experimental protocols for establishing these parameters.

Assay Specificity and In Silico Analysis

Purpose: To ensure the assay exclusively amplifies the intended target sequence and does not cross-react with non-targets, including homologous genes or splice variants [8] [23].

Detailed Protocol:

- In Silico Analysis: Before any wet-lab work, perform an in silico specificity check using BLAST programs against relevant genomic databases (e.g., NCBI, Ensembl) to ensure primer/probe sequences are unique to the target [23] [9].

- Experimental Validation: Run the qPCR assay and analyze the amplification curve and melting curve. For SYBR Green-based assays, a single peak in the melt curve indicates a single, specific amplification product [9]. For probe-based assays, confirm the amplicon size using gel electrophoresis [23].

- Exclusivity/Inclusivity Testing: Test the assay against a panel of genomic DNA or cDNA from closely related non-target species (exclusivity) and all known variants/strains of the target (inclusivity) to confirm specificity and breadth of detection [24].

Dynamic Range, Linearity, and Amplification Efficiency

Purpose: To determine the range of template concentrations over which the assay can provide reliable quantitative results and to calculate the efficiency of the amplification reaction [24].

Detailed Protocol:

- Preparation of Standard Curve: Prepare a serial dilution series of the target template (e.g., a known concentration of plasmid DNA, PCR product, or synthetic oligonucleotide). A seven 10-fold dilution series, each analyzed in triplicate, is recommended to cover 6-8 orders of magnitude [24] [23].

- qPCR Run and Data Analysis: Run the dilution series in the qPCR assay. Plot the Cq (quantification cycle) values against the logarithm of the starting template concentration.

- Calculation: The linear dynamic range is the concentration range over which this plot is linear. The amplification efficiency (E) is calculated from the slope of the standard curve using the formula: ( E = 10^{(-1/slope)} ). An ideal efficiency of 100% (E=2) corresponds to a slope of -3.32. Efficiencies between 90% and 110% (slope between -3.58 and -3.10) are generally considered acceptable [24] [25]. The coefficient of determination (R²) should be ≥0.980 [24].

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

Purpose: To establish the lowest concentration of the target that can be reliably detected (LOD) and quantified (LOQ) with acceptable accuracy and precision [23]. This is critical for applications like minimal residual disease monitoring or pathogen detection [22].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare multiple replicate dilutions (e.g., 20-24 replicates) of the template at concentrations near the expected detection limit, using a background of non-target DNA/RNA to mimic the sample matrix [23].

- LOD Determination: The LOD is typically defined as the lowest concentration at which 95% of the replicates return a positive result (amplification signal above the established threshold) [23].

- LOQ Determination: The LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be measured with defined accuracy (e.g., within ±0.5 log of the theoretical value) and precision (e.g., coefficient of variation <35%). This requires testing replicate dilutions and assessing both intra- and inter-run precision and accuracy [23].

Precision (Repeatability and Reproducibility)

Purpose: To measure the assay's ability to yield consistent results within a run (repeatability) and between different runs, operators, or instruments (reproducibility) [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Experimental Design: Use at least three levels of positive quality control (QC) samples (low, medium, and high concentrations) that span the assay's dynamic range.

- Testing: Analyze these QC samples in multiple replicates (e.g., n=3) within the same run to assess repeatability. To assess reproducibility, repeat this process across multiple independent runs (e.g., 3 runs on different days), potentially with different operators or reagent lots.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (%CV) for the Cq values or calculated concentrations for each QC level. A lower %CV indicates higher precision.

Table: Key Performance Parameters and Their Validation Targets

| Performance Parameter | Experimental Method | Acceptance Criteria (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity & Inclusivity | In silico BLAST; testing against target variants and non-targets. | Single peak in melt curve; amplification of all intended targets [24] [9]. |

| Dynamic Range & Linearity | 7-point 10-fold serial dilution series in triplicate. | R² ≥ 0.980 [24]. |

| Amplification Efficiency | Standard curve from serial dilutions. | Efficiency = 90–110% [25]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Analysis of 20+ replicate low-concentration samples. | 95% hit rate at the LOD concentration [23]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Multiple replicates of QC samples within one run. | %CV < 10-25% (dependent on COU) [8]. |

A Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful qPCR validation relies on high-quality, well-characterized reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Predesigned Assays | Pre-optimized primer/probe sets for specific targets (e.g., TaqMan assays). | Save time and resources; ensure reproducibility across labs [25]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent dye that intercalates with double-stranded DNA. | Cost-effective; requires thorough specificity checks via melt curve analysis [25] [23]. |

| TaqMan Probe Master Mix | Reaction mix for use with sequence-specific, fluorophore-labeled probes. | Higher specificity; suitable for multiplexing [25] [23]. |

| Nucleic Acid Standards | Samples of known concentration (e.g., gBlocks, plasmid DNA). | Essential for generating standard curves for efficiency, LOD, and LOQ [24] [23]. |

| Commercial Reference Genes | Pre-formulated assays for common housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB). | Provide a starting point for normalization; stability must be validated for your specific conditions [25] [22]. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | A measure of RNA quality (1-10 scale) from systems like Bioanalyzer. | High-quality RNA (RIN > 8) is critical for accurate RT-qPCR results [8]. |

Visualizing the Context of Use and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a study's context of use and the subsequent qPCR validation workflow.

Validation Requirements Driven by Context of Use

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive qPCR assay validation, particularly for clinical research applications, involves multiple critical stages, as shown below.

qPCR Assay Validation Workflow

The validation of a qPCR assay is not a one-size-fits-all process. It is a strategic exercise dictated by the context of use, which defines the stakes and consequences of the data generated. A fit-for-purpose approach ensures that resources are allocated efficiently, validating only the necessary parameters to a level of rigor that supports the intended application—from early-stage discovery research to clinical diagnostics. By systematically defining the COU, implementing the appropriate experimental protocols for key performance parameters, and utilizing a robust toolkit of reagents, researchers can ensure their qPCR data is reliable, reproducible, and fit to support their scientific conclusions and clinical decisions.

A Robust Workflow: From Transcriptome Data to Validated qPCR Results

Leveraging RNA-seq Data for Intelligent Candidate Gene Selection

The transition from microarray to RNA-sequencing technologies has revolutionized transcriptomic analysis, offering an unprecedented view of cellular transcriptional activity without requiring prior knowledge of the transcriptome. However, this technology shift has introduced new challenges in data processing, analysis, and validation. This technical guide explores sophisticated computational approaches for identifying high-priority candidate genes from RNA-seq data and establishes a framework for determining when orthogonal validation using reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains necessary. By integrating benchmarked workflows, machine learning-assisted gene selection, and multi-optic validation strategies, researchers can optimize resource allocation while maintaining scientific rigor in transcriptomic studies.

RNA-sequencing has become the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification, replacing microarrays in most research applications [6]. This transition is largely driven by RNA-seq's broader dynamic range, increased sensitivity, and ability to detect novel transcripts and alternative splicing events [6]. However, the rapid evolution of RNA-seq technologies and analysis workflows has created a complex landscape where validation requirements must be continually reassessed.

A critical question facing researchers is whether RT-qPCR validation remains necessary for RNA-seq findings. While some argue that RNA-seq's direct sequencing approach provides sufficient inherent validity, benchmarking studies reveal that technical artifacts and workflow-specific biases can affect results for specific gene subsets [6] [26]. The emergence of large-scale multi-center studies has further demonstrated significant inter-laboratory variations in RNA-seq results, particularly when detecting subtle differential expression with potential clinical relevance [27].

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging RNA-seq data through intelligent candidate gene selection while establishing evidence-based criteria for RT-qPCR validation. By integrating computational benchmarking, machine learning approaches, and systematic quality assessment, researchers can optimize their transcriptomic workflows for both discovery and validation phases.

RNA-seq Workflow Benchmarking: Establishing a Foundation

Performance Comparison of Analysis Workflows

Multiple algorithms have been developed to derive gene counts from RNA-seq reads, each with distinct methodological approaches. Benchmarking studies using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR expression data have evaluated the performance of these workflows to establish their relative strengths and limitations [6] [28].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Analysis Workflows Against RT-qPCR Benchmark

| Workflow | Methodology | Expression Correlation (R²) | Fold Change Correlation (R²) | Non-concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | Pseudoalignment | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% |

| Kallisto | Pseudoalignment | 0.839 | 0.930 | 18.2% |

| Tophat-HTSeq | Alignment-based | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | Alignment-based | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | Alignment-based | 0.798 | 0.927 | 17.8% |

These benchmarking results reveal several critical patterns. First, all methods show high correlation with RT-qPCR data for both expression quantification and fold-change calculations. Second, alignment-based methods (particularly Tophat-HTSeq and STAR-HTSeq) demonstrate slightly lower rates of non-concordant genes compared to pseudoalignment approaches [6]. Notably, the almost identical results between Tophat-HTSeq and STAR-HTSeq (R² = 0.994 for expression, R² = 0.996 for fold changes) suggest minimal impact of the mapping algorithm on quantification accuracy [6].

Characteristics of Problematic Genes

Benchmarking studies have identified a consistent set of gene characteristics associated with discrepant results between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. Method-specific inconsistent genes are typically smaller, have fewer exons, and show lower expression levels compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [6] [28]. These problematic genes represent a small but significant subset where additional validation is most warranted.

Diagram 1: Standard RNA-seq analysis workflow with key validation decision point

Machine Learning-Assisted Gene Selection

Predictive Gene Selection Frameworks

Traditional approaches to candidate gene selection often rely on statistical cutoffs (fold-change and p-value thresholds) or prior biological knowledge. Machine learning (ML) methods offer a powerful alternative by learning complex patterns from existing data to identify genes of interest that might be overlooked by conventional approaches [29].

The PERSIST (PredictivE and Robust gene SelectIon for Spatial Transcriptomics) framework represents a sophisticated approach to gene selection using deep learning [30]. This method identifies informative gene targets by leveraging reference single-cell RNA-seq data to select minimal gene panels that optimally reconstruct entire expression profiles. The framework employs a custom selection layer that applies a learned binary mask to gradually sparsify inputs down to a user-specified number of genes [30].

Another ML approach, described in the RNA-seq Assistant study, identified top informative features through comprehensive assessment of three feature selection algorithms combined with five classification methods [29]. This research demonstrated that a model based on InfoGain feature selection and Logistic Regression classification effectively predicted differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were missed by traditional RNA-seq analysis in studies of ethylene-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis [29].

gSELECT: A Pre-analysis Machine Learning Library

For researchers seeking to implement ML approaches without extensive computational expertise, tools like gSELECT provide accessible solutions [31]. This Python library evaluates classification performance of both automatically ranked and user-defined gene sets, supporting hypothesis-driven testing without data-derived selection bias.

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches for Gene Selection

| Method | Selection Approach | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PERSIST | Deep learning with binary mask | Technology transfer capability, Hurdle loss function for dropouts | Spatial transcriptomics, Cell type identification |

| RNA-seq Assistant | Feature selection + classification | Uses epigenetic features, Logistic regression | Predicting stress-responsive genes |

| gSELECT | Mutual information ranking | Hypothesis testing, Combinatorial gene effects | Pre-analysis evaluation, Candidate validation |

| scGeneFit | Linear programming | Manifold preservation, Label-aware selection | Cell type classification |

gSELECT operates on .csv or .h5ad expression matrices with group labels and can be integrated into existing analysis pipelines [31]. Gene selection can be based on mutual information ranking, random sampling, or custom input, enabling researchers to directly evaluate known or candidate markers before committing to resource-intensive downstream analyses [31].

Diagram 2: Machine learning workflow for candidate gene selection

Reference Gene Selection for Validation Studies

GSV: Gene Selector for Validation Software

Appropriate selection of reference genes is critical for accurate RT-qPCR validation, as improperly chosen reference genes can lead to misinterpretation of results [14]. The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software addresses this challenge by systematically identifying optimal reference and validation candidate genes from RNA-seq data [14].

GSV applies a filtering-based methodology using TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values to compare gene expression between RNA-seq samples. For reference gene identification, the software implements five sequential filters [14]:

- Expression greater than zero in all libraries

- Low variability between libraries (standard deviation of log₂(TPM) < 1)

- No exceptional expression in any library (maximum twice the average of log₂ expression)

- High expression level (average log₂(TPM) > 5)

- Low coefficient of variation (< 0.2)

For validation candidate genes (variable genes), GSV applies modified filters focused on identifying genes with sufficient expression that show considerable differences between samples [14]. This approach represents a significant improvement over traditional methods that often rely on presumed housekeeping genes without empirical validation of their stability in specific experimental conditions.

Practical Implementation of GSV

GSV was developed using Python and leverages Pandas, Numpy, and Tkinter libraries to create a user-friendly graphical interface that accepts multiple file formats (.xlsx, .txt, .csv) without requiring command-line interaction [14]. In a real-world application using Aedes aegypti transcriptome data, GSV identified eiF1A and eiF3j as the most stable reference genes, while confirming that traditional mosquito reference genes were less stable in the analyzed samples [14].

When is qPCR Validation Required? An Evidence-Based Framework

Multi-center Studies and Real-world Performance

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the reliability of RNA-seq data and the continuing need for validation. The Quartet project, a multi-center study involving 45 laboratories using Quartet and MAQC reference samples, revealed significant inter-laboratory variations in RNA-seq results [27]. This extensive analysis generated over 120 billion reads from 1080 libraries, representing the most comprehensive evaluation of real-world RNA-seq performance to date [27].

A key finding was the greater inter-laboratory variation in detecting subtle differential expression among Quartet samples compared to the more distinct MAQC samples [27]. Experimental factors including mRNA enrichment and strandedness, along with each bioinformatics step, emerged as primary sources of variation in gene expression measurements [27]. These results underscore the importance of validation for studies focusing on subtle expression differences with potential clinical significance.

Decision Framework for qPCR Validation

Based on current evidence, we propose the following decision framework for determining when qPCR validation is required:

Table 3: qPCR Validation Decision Framework

| Scenario | Validation Recommended? | Rationale | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtle differential expression | Required | Higher inter-laboratory variation, Lower SNR | Multiple reference genes, Technical replicates |

| Low-expression genes | Conditionally required | Higher technical variability, Dropout effects | Digital PCR for very low expression |

| Genes with specific characteristics | Conditionally required | Small size, Few exons show inconsistencies | Prioritize from benchmarking studies |

| Large-fold change differences | Optional | High correlation with qPCR, Reproducible | Spot-checking approach |

| Clinical/regulatory applications | Required | Regulatory requirements, Clinical impact | Full validation following guidelines |

| Novel findings without prior support | Required | Lack of corroborating evidence | Orthogonal validation methods |

This framework recognizes that while RNA-seq has remarkable accuracy for many applications, specific scenarios warrant the additional rigor provided by RT-qPCR validation. Factors such as effect size, gene characteristics, intended application, and novelty of findings should inform validation decisions.

Integrated Workflow for Candidate Gene Selection and Validation

Comprehensive Experimental Protocol

Based on the analyzed studies, we propose the following integrated workflow for leveraging RNA-seq data with intelligent candidate gene selection and validation:

Phase 1: Experimental Design and RNA-seq

- Sample Preparation: Implement rigorous RNA quality control (RIN > 8)

- Library Preparation: Select strand-specific protocols with UMIs

- Sequencing: Minimum 30 million reads per sample, appropriate read length

Phase 2: Computational Analysis

- Quality Control: FastQC, MultiQC

- Alignment: STAR or HISAT2 with appropriate annotation

- Quantification: Salmon or Kallisto for gene-level counts

- Differential Expression: DESeq2 or edgeR

- Machine Learning Screening: gSELECT or custom ML approach

Phase 3: Validation Strategy

- Reference Gene Selection: GSV software or similar approach

- Candidate Prioritization: Focus on genes with characteristics prone to discrepancies

- Experimental Validation: RT-qPCR with minimum three reference genes

- Data Normalization: GeNorm or NormFinder for reference gene stability

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Benchmarking and QC | MAQCA, MAQCB, Quartet samples |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Technical variability assessment | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix |

| Stranded RNA-seq Kits | Library preparation | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra II |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Validation experiments | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays |

| Reference Gene Panels | qPCR normalization | Commercially available panels |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data analysis | GSV, gSELECT, PERSIST |

RNA-sequencing technologies have fundamentally transformed transcriptomic research, enabling comprehensive gene expression profiling at unprecedented scale and resolution. However, the demonstrated variability across laboratories and the specific technical challenges associated with particular gene subsets indicate that RT-qPCR validation remains an essential component of rigorous transcriptomic research, particularly for studies with clinical applications, subtle expression differences, or novel findings.

By integrating the computational approaches outlined in this whitepaper—including benchmarked analysis workflows, machine learning-assisted gene selection, and systematic reference gene identification—researchers can significantly enhance their candidate gene selection process while making informed decisions about validation requirements. The continued development of sophisticated computational methods promises to further refine this process, potentially reducing but not eliminating the need for orthogonal validation in carefully defined scenarios.

As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and multi-optic integration becomes standard practice, the principles of rigorous validation and intelligent candidate selection will remain fundamental to generating reliable, reproducible transcriptomic insights with potential translational impact.

The transition from microarray and RNA-seq technologies to quantitative PCR (qPCR) validation represents a critical bottleneck in transcriptomics research. A foundational, yet often overlooked, step in this process is the rigorous identification of stably expressed reference genes, which are essential for reliable qPCR normalization. This whitepaper delineates the scenarios mandating qPCR confirmation of transcriptomic data and provides a comprehensive guide on leveraging bioinformatics tools to select optimal reference genes. By integrating modern computational approaches with established experimental protocols, we present a robust framework to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of gene expression analysis, thereby strengthening the pipeline from high-throughput discovery to targeted validation.

Despite the ascendancy of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) as the capstone technology for gene expression profiling, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validation. The persistence of qPCR is rooted in its superior sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and the maturity of its technology, which has withstood the test of time [14] [7]. The central question for researchers is not if, but when this validation is required.

The process of validating high-throughput data with a low-throughput technique like qPCR is often driven by two primary needs: the "journal reviewer" mindset, where confirmation via a different technique bolsters the credibility of an observation for publication, and the "cost-savings" mindset, where initial RNA-seq data is generated with a small number of biological replicates, and qPCR is subsequently used to validate findings on a larger sample set [7]. However, validation is considered inappropriate when the RNA-seq data serves merely as a primary screen to generate new hypotheses for exhaustive testing at the protein level, or when the validation plan itself involves generating more RNA-seq data on a new, larger set of samples [7].

Crucially, the accuracy of any qPCR-based gene expression analysis hinges on normalization using stably expressed reference genes, also known as housekeeping genes. These genes control for technical variations in RNA integrity, cDNA synthesis, and PCR amplification efficiency [15] [32]. The erroneous selection of reference genes with variable expression can lead to significant misinterpretation of data, a problem exacerbated by the fact that traditional housekeeping genes like ACT (actin) and GAPDH are not universally stable across all biological conditions [32] [14] [33]. Therefore, the identification of validated, stable reference genes is not a mere procedural formality but a critical prerequisite for ensuring the fidelity of transcriptomics validation.

When is qPCR Validation Required? A Decision Framework

The decision to validate RNA-seq results with qPCR should be guided by the context of the research and the intended use of the data. The following table summarizes key decision criteria.

Table 1: Framework for Deciding When qPCR Validation is Required

| Scenario | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Confirming a pivotal finding | Appropriate | Builds credibility for manuscript publication by confirming an observation with an orthogonal technology [7]. |

| Underpowered RNA-seq study | Appropriate | Cost-effective method to verify differential expression on a larger, more statistically powerful sample set [7]. |

| RNA-seq as a hypothesis generator | Inappropriate | If subsequent work will focus on protein-level validation, qPCR adds little value [7]. |

| Resources for additional RNA-seq | Inappropriate | The most robust validation is replicating the findings with a new RNA-seq dataset [7]. |

For scenarios where qPCR validation is deemed appropriate, a rigorous workflow must be followed. The most robust approach involves performing qPCR not only on the original RNA samples used for RNA-seq (as a technology control) but also on a new, independent set of samples with proper biological replication. This strategy validates both the technology and the underlying biological response, providing a comprehensive "win-win" situation [7].

Beyond Traditional Housekeepers: A Bioinformatics-Driven Approach

The classical approach of selecting reference genes based solely on their known biological functions in basic cellular processes is fraught with risk. Transcriptomic studies have repeatedly demonstrated that the expression of traditional housekeeping genes can be modulated by specific biological conditions [14]. For instance, a stability analysis of ten candidate reference genes across different sweet potato tissues revealed that IbACT, IbARF, and IbCYC were the most stable, while IbGAP, IbRPL, and IbCOX were the least stable [15]. This highlights the perils of assuming the stability of genes like GAPDH without empirical validation.

Modern bioinformatics tools now enable a more rational and data-driven selection process by directly mining RNA-seq data itself to identify genes with high and stable expression. This represents a significant advance beyond tradition.

The GSV Software: A Tool for Bioinformatics-Based Selection

A key innovation in this field is the "Gene Selector for Validation" (GSV) software, a tool specifically designed to identify the best reference and variable candidate genes for qPCR validation from RNA-seq data [14].

GSV operates on Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values from RNA-seq quantification tables. Its algorithm applies a series of sequential filters to identify ideal reference gene candidates:

- Ubiquitous Expression: The gene must have a TPM > 0 in all analyzed libraries.

- Low Variability: The standard deviation of log2(TPM) across libraries must be < 1.

- No Exceptional Outliers: The log2(TPM) in any single library must not deviate by more than 2 from the mean log2(TPM).

- High Expression: The average log2(TPM) must be > 5, ensuring the gene is within easy detection limits of RT-qPCR.

- Low Coefficient of Variation: The coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean) must be < 0.2, confirming consistent expression relative to its abundance [14].

This multi-step filtering process ensures that the final list of candidate reference genes is not only stable but also highly expressed, thereby avoiding the common pitfall of selecting stable genes with low expression levels that are unsuitable for qPCR normalization.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Reference Gene Evaluation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Data | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) | Identifies stable reference & variable validation genes from RNA-seq data. | TPM values from RNA-seq. | Integrates stability and expression level filters; user-friendly GUI [14]. |

| RefFinder | Provides a comprehensive stability ranking by integrating multiple algorithms. | Cq values from qPCR. | Combines results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the Delta-Ct method [15] [32] [34]. |

| geNorm | Evaluates gene stability and determines the optimal number of reference genes. | Cq values from qPCR. | Calculates a stability measure (M) and performs pairwise comparison [15] [33] [35]. |

| NormFinder | Estimates expression variation and ranks candidate genes. | Cq values from qPCR. | Accounts for both intra- and inter-group variation [15] [33] [35]. |

| BestKeeper | Assesses gene stability based on raw Cq values and correlation analysis. | Raw Cq values from qPCR. | Uses pairwise correlation analysis to identify stable genes [15] [32] [34]. |

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow, from RNA-seq analysis to final qPCR validation, emphasizing the role of bioinformatics at each stage.

Integrated Workflow for Reference Gene Identification

Experimental Protocol: From Bioinformatics to Bench Validation

The following section provides a detailed, actionable protocol for transitioning from a bioinformatics-based candidate list to a set of wet-lab validated reference genes.

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Experimental Design: Collect samples encompassing all the biological conditions relevant to your study (e.g., different tissues, developmental stages, drug treatments). Use at least five biological replicates per condition to ensure statistical power [32].

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., TIANGEN RNAprep Plant Kit for plants, TransZol Up Plus RNA Kit for insects) [32] [33]. To ensure high-quality RNA, treat samples with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination. Assess RNA integrity using 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and determine concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio of ~2.0) using a spectrophotometer [33].

cDNA Synthesis and Primer Design

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 1 μg of total RNA using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (e.g., TransGen Biotech's EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix or TIANGEN's FastQuant RT Kit) [32] [33]. Include a gDNA wipe buffer step to ensure no genomic DNA remains.

- Primer Design: For the candidate genes identified by GSV, design primers using software such as Primer Premier 5.0 or Beacon Designer 8.0 [32] [33]. Key design criteria include:

- Amplicon length: 80-200 base pairs.

- Primer melting temperature (Tm): 58-62°C.

- Avoidance of secondary structures and primer-dimer formation.

- Primer Validation: Validate primer specificity by performing standard PCR, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm a single amplicon of the expected size. For absolute verification, the PCR product can be gel-purified, cloned into a vector (e.g., pGEM-T), and sequenced by Sanger sequencing [33]. For qPCR, generate a standard curve using serial dilutions of cDNA to calculate primer amplification efficiency (ideally 90-105%) and correlation coefficient (R² > 0.99) [33].

qPCR Amplification and Data Collection

- Reaction Setup: Perform qPCR reactions in a 20 μL volume containing 10 μL of 2x SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (e.g., ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix or TIANGEN's Talent qPCR PreMix), 0.6 μL of each primer (10 nM), 2 μL of diluted cDNA (1:5), and RNase-free water [32] [33].

- Thermocycling Conditions: A typical protocol is: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min [33]. Following amplification, perform a melt curve analysis (e.g., from 60°C to 95°C) to confirm the specificity of the amplification and the absence of primer dimers.

- Data Collection: For each reaction, record the quantification cycle (Cq) value. All reactions should be run in technical triplicates to account for pipetting errors.

Stability Analysis and Functional Validation

Once Cq data is collected, the expression stability of the candidate reference genes must be computationally assessed using multiple algorithms. The following diagram illustrates the analytical process within the RefFinder platform.

RefFinder Stability Analysis Workflow

Interpreting Stability Analysis