Resolving the Discord: Technical Causes and Solutions for RNA-Seq and qPCR Data Discrepancies

The comparison of gene expression data generated by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) often reveals discrepancies that can challenge data interpretation and validation, particularly in biomedical and clinical...

Resolving the Discord: Technical Causes and Solutions for RNA-Seq and qPCR Data Discrepancies

Abstract

The comparison of gene expression data generated by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) often reveals discrepancies that can challenge data interpretation and validation, particularly in biomedical and clinical research. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical foundations behind this discordance, exploring inherent methodological differences in amplification, alignment, and normalization. It delves into application-specific challenges, such as profiling complex gene families like HLA, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for experimental design and bioinformatic analysis. Furthermore, it examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative studies, synthesizing key takeaways to guide researchers and drug development professionals toward more robust and reproducible transcriptomic analyses.

The Fundamental Divide: Core Technical Principles Driving RNA-Seq and qPCR Discordance

A clear understanding of the inherent methodological biases in qPCR and RNA-seq is crucial for the accurate interpretation of gene expression data. This guide details the technical origins of discordance between these methods, providing troubleshooting protocols and reagent solutions to enhance the reliability of your research.

Core Technological Differences and Their Biases

The journey from a biological sample to quantifiable gene expression data involves distinct processes for qPCR and RNA-seq, each introducing specific biases. The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these two methodologies.

| Feature | qPCR | RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Quantification of known sequences [1] | Hypothesis-free discovery of known and novel transcripts [1] |

| Throughput | Low to medium (best for ≤ 20 targets) [2] [1] | High (can profile thousands of targets simultaneously) [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Wide, with low limits of quantification [2] | Very wide, capable of detecting subtle changes (down to 10%) [1] |

| Key Strengths | Gold standard for validation; simple workflow; highly sensitive [2] [3] | Detects novel transcripts, splice variants, and sequence variants [1] |

| Inherent Biases | Amplification efficiency; reference gene selection [4] | Alignment errors due to polymorphism; GC content; library prep batch effects [5] [6] |

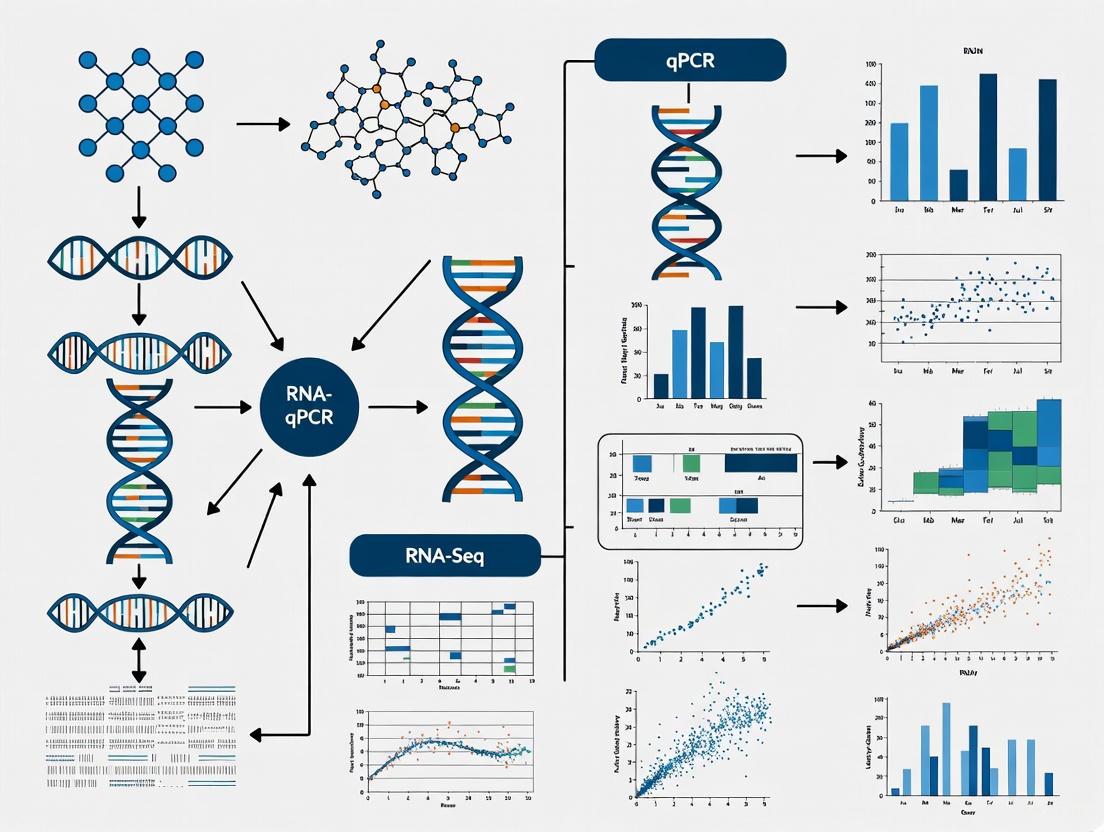

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the distinct steps and potential failure points in each method.

qPCR Analysis Workflow

RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is there a poor correlation between my qPCR and RNA-seq results for the same samples?

Discordance often stems from fundamental technical biases. A study comparing HLA class I gene expression found only moderate correlations (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between qPCR and RNA-seq estimates [5]. The table below outlines primary causes and solutions.

| Cause of Discordance | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Gene Instability (qPCR) | Using reference genes whose expression varies across experimental conditions severely skews normalized expression [4]. | Validate reference gene stability with algorithms like NormFinder; avoid using RNA-seq to pre-select reference genes [4]. |

| Alignment Ambiguity (RNA-seq) | The extreme polymorphism of genes like HLA complicates read alignment, leading to mis-mapping and inaccurate quantification [5]. | Use HLA-tailored bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., from Aguiar et al. 2019) that account for allelic diversity, rather than a standard reference genome [5]. |

| Transcript Length & Expression Level Bias | RNA-seq normalization methods can be biased toward longer transcripts, and lowly expressed genes are harder to quantify accurately [4]. | For qPCR validation, prioritize genes with longer transcripts and higher expression levels to improve concordance [4]. |

| Library Preparation Batch Effects | Technical variation from library prep is a major source of bias in RNA-seq, affecting expression estimates [6]. | Randomize samples during preparation, use multiplexing, and include samples from all experimental groups on each sequencing lane [6]. |

FAQ 2: How can I improve the accuracy of RNA-seq read alignment for polymorphic or highly homologous gene families?

Alignment to a standard reference genome is often inadequate for gene families with high sequence similarity, such as HLA or KIR.

- Use Specialized Alignment Tools: Standard RNA-seq aligners like STAR or HISAT2 may not handle colorspace data from older technologies (e.g., SOLiD). Ensure you use a mapper designed for your specific data type [7].

- Leverage Custom Reference Pipelines: Implement bioinformatic methods designed specifically for polymorphic loci. These tools incorporate known allele sequences into the alignment process, which dramatically improves accuracy [5].

- Verify Annotation Compatibility: A common alignment failure occurs when the chromosome identifiers in your annotation file (GTF) do not match those in your reference genome (e.g., "chr1" vs. "1"). Always use a GTF file from the same data provider as your reference genome [8].

FAQ 3: My RNA-seq data has a high proportion of multi-mapped reads. What does this mean and how should I handle it?

A high rate of multi-mapping is expected when sequences are present in multiple genomic locations.

- Identify the Source: Multi-mapped reads often originate from repetitive regions, gene families with high sequence homology (e.g., HLA, rRNA), or transposable elements [7].

- Filter rRNA Reads: Use tools like SortMeRNA to identify and remove reads derived from ribosomal RNA, which is a common source of multi-mapping [7].

- Context-Dependent Decision: There is no universal solution for multi-mapped reads. For differential expression analysis of single-copy genes, they can often be excluded. However, for studies of gene families, specialized statistical models are needed to proportionally assign these reads.

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Protocol: Direct Comparison of qPCR and RNA-seq for HLA Gene Expression

This protocol is adapted from a study that systematically compared expression estimates from qPCR, RNA-seq, and cell surface expression [5].

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction:

- Obtain PBMCs from healthy donors with written informed consent.

- Extract total RNA using a kit such as the RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen).

- Treat RNA with RNAse-free DNAse to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quantify RNA using a method like the HT RNA Lab Chip (Caliper, Life Sciences).

qPCR Analysis:

- Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Perform qPCR using assays specific for HLA-A, -B, and -C genes.

- Follow the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines to ensure reliability, including controls and PCR efficiency checks [2].

- Normalize Cq values using reference genes validated as stable for your experimental system [4].

RNA-seq Analysis:

- Prepare RNA-seq libraries from the same RNA samples. A strand-specific library preparation protocol is recommended.

- Sequence the libraries on a platform such as an Illumina HiSeq, aiming for sufficient depth (e.g., 50-100 million paired-end reads per sample).

- Process the data using an HLA-tailored pipeline, not a standard alignment workflow. This involves:

- Quality control with FastQC.

- Using a specialized aligner or workflow that incorporates a database of HLA alleles.

- Quantifying expression with tools that accurately assign reads to specific HLA genes.

Validation: Compare RNA-seq and qPCR expression estimates using correlation analysis (e.g., Spearman's rho). A subset of samples can also be analyzed by flow cytometry for HLA cell surface expression to provide a third data dimension [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their critical functions for experiments comparing qPCR and RNA-seq.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality RNA extraction from PBMCs. | Ensures intact, DNA-free RNA as a starting point for both methods [5]. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Sequence-specific detection and quantification in qPCR. | Available for most exon-exon junctions; select assays that are variant-specific if necessary [3]. |

| Stranded mRNA Prep (Illumina) | Library preparation for RNA-seq. | A simple, scalable solution for analyzing the coding transcriptome [1]. |

| HLA-Tailored Pipeline (e.g., from Aguiar et al.) | Bioinformatics software for accurate HLA expression quantification. | Corrects for alignment biases in polymorphic genes that plague standard methods [5]. |

| NormFinder Algorithm | Statistical tool for identifying stable reference genes from qPCR data. | More effective for qPCR normalization than pre-selecting genes from RNA-seq data [4]. |

| SortMeRNA | Bioinformatics tool for filtering ribosomal RNA reads from RNA-seq data. | Reduces a major source of multi-mapped reads and improves usable sequence depth [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the core differences in how qPCR and RNA-seq perform quantification?

- qPCR typically uses relative quantification, where the expression of a target gene is measured relative to a control (often a housekeeping gene) present in the same sample. The result is a fold-change value, not an absolute molecular count [9] [10].

- RNA-seq provides a genome-wide estimate of transcript abundance for all detected genes. Quantification is often expressed as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) or similar metrics, which normalize for sequencing depth and gene length [11].

Why might the expression values for the same gene differ between qPCR and RNA-seq? Technical and biological factors contribute to this discordance [5]:

- Normalization Strategy: qPCR relies on one or a few stable reference genes, while RNA-seq uses global normalization across all mapped reads. If the qPCR reference gene's expression varies, it skews the results [10].

- Sequence-Specific Biases: The extreme polymorphism of genes like HLA can cause RNA-seq alignment issues, where reads fail to map correctly to a reference genome, leading to underestimation. Specialized bioinformatic pipelines are needed for accurate quantification of such genes [5].

- Technical Sensitivity: Each method has different sensitivities to factors like RNA integrity, GC content, and amplification efficiency [5] [12].

When designing an RNA-seq experiment, what steps can I take to improve the accuracy of gene expression estimates?

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality RNA with a RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 8 [12].

- Read Depth: Aim for sufficient sequencing depth; typically 20-30 million reads per sample for large genomes (e.g., human, mouse) is recommended [11].

- Spike-in Controls: Use External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) synthetic RNA spike-ins to help standardize quantification across samples and runs [11].

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during library preparation to correct for PCR amplification bias and duplicates [11].

My qPCR and RNA-seq data show a weak correlation. How should I troubleshoot? Begin by systematically checking the following areas:

- Verify qPCR Assay Quality: Confirm that your primer sets have high and nearly equal amplification efficiencies (90-110%). A difference of more than 5% requires the use of efficiency-corrected models (like the Pfaffl method) instead of the 2-^ΔΔCt^ method [10].

- Inspect RNA Integrity: Check the quality of the RNA used in both assays. Degraded RNA can disproportionately affect different transcripts in each technology [13].

- Check for Genomic DNA Contamination: In qPCR, ensure samples are treated with DNase. Primers should span exon-exon junctions to minimize amplification of genomic DNA [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Correlation Between qPCR and RNA-seq Data

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Underlying Technical Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal qPCR Reference Gene | Test multiple candidate reference genes and use an algorithm (e.g., geNorm, NormFinder) to identify the most stably expressed gene(s) for your specific experimental conditions [10]. | Housekeeping gene expression can vary with treatment or tissue type. Normalizing to an unstable reference gene introduces systematic error in relative quantification [10]. |

| RNA-seq Misalignment | For highly polymorphic gene families (e.g., HLA), use HLA-tailored RNA-seq bioinformatic pipelines that account for individual allelic diversity rather than aligning to a single reference genome [5]. | Standard RNA-seq alignment tools may fail to correctly map reads from polymorphic regions, leading to inaccurate quantification [5]. |

| Different Molecular Phenotypes | Acknowledge that qPCR (mRNA level) and antibody-based assays (cell surface protein level) measure different stages of gene expression. They are not directly equivalent [5]. | Post-transcriptional regulation (e.g., translation efficiency, protein degradation) causes discordance between transcript abundance and protein presentation [5]. |

Problem 2: High Variability in qPCR Replicates

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Underlying Technical Principle |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Inhibition or Pipetting Error | Dilute the template to reduce inhibitor concentration and ensure proficient pipetting technique with fresh standard curves and technical triplicates [13]. | Inhibitors in the reaction reduce amplification efficiency, leading to late Ct values. Pipetting errors create well-to-well concentration differences [13]. |

| Inconsistent PCR Consumables | Select qPCR plates with thin-walled, white wells for improved thermal conductivity and signal consistency. Ensure seals are optically clear and properly applied [14]. | Suboptimal plates cause uneven heat transfer. Poor seals lead to evaporation and well-to-well contamination, increasing data variability [14]. |

| Amplification in No Template Control (NTC) | Decontaminate workspaces and pipettes. Prepare fresh primer dilutions. Include a dissociation curve to check for primer-dimer formation [13]. | Primer-dimers are short, nonspecific PCR products that amplify efficiently in the absence of target template, yielding false-positive signals [13]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Comparing HLA Expression by qPCR and RNA-seq

This protocol is adapted from a study that directly compared these techniques [5].

1. Sample Preparation

- Source: Obtain Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors with informed consent.

- RNA Extraction: Use a kit such as the RNeasy Universal kit (Qiagen). Treat extracted RNA with RNase-free DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quality Control: Quantify total RNA using a method like the HT RNA Lab Chip (Caliper). Assess RNA integrity (RIN >8 is ideal) before proceeding.

2. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

- Assay Design: Design primers for HLA class I genes (HLA-A, -B, -C) and reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin).

- Efficiency Test: Perform a 10-fold serial dilution of cDNA to generate a standard curve. Calculate primer efficiency using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope). Only use primers with 90-110% efficiency [10].

- Relative Quantification: Run qPCR reactions for all samples. Analyze data using the 2-^ΔΔCt^ method if primer efficiencies are nearly equal, or the Pfaffl method if they differ [10].

3. RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries. Select rRNA depletion over poly-A selection for comprehensive inclusion of coding and non-coding RNA species [11].

- Sequencing: Use an Illumina platform to generate single-end or paired-end reads. Target a minimum depth of 20-30 million reads per sample [11].

4. Bioinformatic Analysis of RNA-seq Data

- HLA-Specific Quantification: Do not use a standard alignment pipeline. Instead, use an HLA-tailored computational tool (e.g., as used in [5]) that incorporates personal allelic variation for accurate expression estimation.

- Standard Gene Quantification: For all other genes, align reads to a reference genome and generate a count matrix using a tool like STAR or HISAT2.

5. Data Comparison

- Perform correlation analysis (e.g., Spearman's rank) between the qPCR-derived expression values and the RNA-seq-derived counts for the HLA class I genes. A moderate correlation (e.g., 0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) is commonly observed, highlighting the inherent technical differences [5].

Workflow Diagram: qPCR vs. RNA-seq Normalization

Diagram: Technical Challenges in RNA-seq

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment | Technical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Total RNA | The starting template for both qPCR and RNA-seq. | Critical: Quality must be verified via RIN >8. Degraded RNA is a major source of technical variation and discordant results [12]. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Degrades contaminating genomic DNA during RNA purification to prevent false amplification in qPCR. | Essential for accurate qPCR, especially if primers do not span an exon-exon junction [5] [13]. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | A set of synthetic RNA controls of known concentration added to samples before RNA-seq library prep. | Used to monitor technical variation, determine the sensitivity, and standardize quantification across experiments [11]. |

| Unique Molecular Indexes (UMIs) | Short nucleotide barcodes added to each cDNA molecule during library prep. | Allows for bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification bias and accurate counting of original mRNA molecules, crucial for low-input RNA-seq [11]. |

| qPCR Plates, White Wells | The reaction vessel for qPCR. | White wells reduce signal crosstalk and enhance fluorescence reflection to the detector, improving well-to-well consistency and data quality [14]. |

| Optically Clear Seals | Used to seal qPCR plates. | Prevents sample evaporation and cross-contamination. Optical clarity is essential to avoid distortion of fluorescence signals [14]. |

| HLA-Tailored Bioinformatics Pipeline | Software for quantifying expression from RNA-seq data. | Necessary for accurate estimation of HLA and other polymorphic gene expression, overcoming limitations of standard alignment to a single reference [5]. |

Table 1: Impact of Transcript Characteristics on RNA-Seq and qPCR Quantification

| Transcript Characteristic | Impact on RNA-Seq | Impact on qPCR | Potential for Discordance | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript Length | Quantification biased towards longer transcripts due to transcript-length bias in common normalization strategies (e.g., RPKM) [4]. | No significant length bias when primers are designed to short, specific amplicons [15]. | High | Genes with shorter transcript lengths show discordant results between RNA-Seq and qPCR [4]. |

| GC Content | GC content can influence sequencing efficiency and coverage uniformity, impacting quantification [16]. | High GC content can lead to inefficient amplification, primer-dimer formation, and non-specific binding if not optimized [17] [18]. | Moderate | Primer design guidelines explicitly recommend 40-60% GC content to ensure efficient amplification and avoid artifacts [17] [18] [19]. |

| Expression Level | Discrimination against lowly expressed genes; a small set of highly expressed genes consumes most sequencing reads [4]. | Highly sensitive and accurate for low-abundance transcripts, provided robust reference genes are used [20]. | High | Discordance is more pronounced for genes with lower expression levels [15]. |

| Transcript Integrity (RNA Quality) | Sample degradation causes widespread effects on gene expression measurements, with a loss of library complexity [21]. | Generally more robust to moderate RNA degradation, though severe degradation affects all transcripts [21]. | High | Microarray and RNA-Seq data are more sensitive to RNA quality variations compared to qPCR [21]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Normalization Strategies for qPCR

| Normalization Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations / Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Reference Gene | Normalizes target gene expression to one internal control gene (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB). | Simple, cost-effective. | Error-prone; housekeeping gene expression can vary significantly across tissues and experimental conditions, leading to large errors [20]. |

| Multiple Reference Genes | Normalizes target gene expression to the geometric mean of multiple, validated reference genes [20]. | More robust and accurate; accounts for variation in a single gene. | Requires validation of gene stability for each specific experimental condition [22] [20]. |

| Global Mean (GM) | Normalizes to the average expression of a large set of genes (e.g., >55) profiled in the experiment [22]. | Does not rely on pre-selected genes; can be superior when profiling many genes. | Requires high-throughput qPCR to profile a large number of genes; minimum gene set not firmly established [22]. |

| RNA-Seq Pre-Selection | Using RNA-Seq data to pre-select "stable" genes for qPCR normalization. | Intrinsically data-driven. | Offers no significant advantage over using conventional reference genes paired with a robust statistical validation method [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Reference Genes for qPCR Normalization

Objective: To identify the most stably expressed reference genes for a specific experimental condition to ensure reliable qPCR normalization [22] [20].

Methodology:

- Select Candidate Genes: Choose a panel of 8-10 candidate reference genes from different functional classes to minimize co-regulation. Common candidates include ACTB, GAPD, B2M, HMBS, HPRT1, RPL13A, SDHA, TBP, UBC, and YWHAZ [20].

- qPCR Profiling: Perform qPCR on all test samples (including all experimental conditions and tissues under study) for each candidate gene. Record the quantification cycle (Cq) values.

- Stability Analysis: Analyze the Cq data using dedicated algorithms to rank the genes by their expression stability.

- geNorm: Ranks genes based on their average pairwise variation with all other genes. The stepwise exclusion of the least stable gene yields a stability measure (M-value); lower M-values indicate greater stability [22].

- NormFinder: A model-based approach that estimates intra- and inter-group variation, providing a stability value for each gene. It is also capable of identifying the best pair of genes [22].

- Determine the Number of Genes: Use the geNorm algorithm to calculate the pairwise variation (V) between sequential normalization factors (NFn and NFn+1). A value of V < 0.15 indicates that n genes are sufficient for a reliable normalization factor [20].

- Apply the Normalization Factor: For each sample, calculate the normalization factor as the geometric mean of the Cq values of the selected, most stable reference genes. Use this factor to normalize the expression of your target genes [20].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking RNA-Seq Workflows with qPCR

Objective: To assess the accuracy of RNA-Seq differential expression analysis by comparing it with qPCR data for protein-coding genes [15].

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Use well-characterized RNA reference samples (e.g., MAQC-I MAQCA and MAQCB) [15].

- Data Generation:

- RNA-Seq: Process samples using multiple RNA-Seq data processing workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon). Generate gene-level expression values (e.g., TPM or counts).

- qPCR: Perform a whole-transcriptome qPCR analysis on the same samples using wet-lab validated assays for all protein-coding genes.

- Data Alignment: For a fair comparison, align the transcripts detected by qPCR with the transcripts quantified by RNA-Seq. For transcript-based workflows (Kallisto, Salmon), aggregate transcript-level TPM values to the gene level based on the qPCR assay targets [15].

- Correlation Analysis:

- Expression Correlation: Calculate the correlation (e.g., Pearson R²) between normalized qPCR Cq-values and log-transformed RNA-Seq expression values across all genes.

- Fold-Change Correlation: Calculate the gene expression fold changes between sample groups (e.g., MAQCA vs. MAQCB) for both technologies. Assess the correlation of these log fold changes [15].

- Identify Discrepancies: Define genes with large absolute differences in fold change (ΔFC > 2) between RNA-Seq and qPCR as non-concordant. Characterize these genes for features like transcript length, exon count, and expression level [15].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My RNA-Seq and qPCR results show conflicting fold-changes for a key gene. What are the primary technical causes I should investigate? A: The most common technical causes are:

- Poor qPCR Normalization: The use of a single, unvalidated reference gene is a major source of error. Always validate multiple reference genes for your specific experimental conditions [20].

- Transcript Characteristics: Investigate the characteristics of the discordant gene. Genes that are short, have low expression, or are prone to degradation are frequently implicated in such discordance [4] [15] [21].

- RNA-Seq Biases: RNA-Seq normalization methods can be biased by transcript length, and library preparation can discriminate against low-abundance transcripts [4].

Q2: Is it necessary to use RNA-Seq data to pre-select the best reference genes for my qPCR experiments? A: No. Recent studies demonstrate that with a robust statistical approach (e.g., using NormFinder or geNorm) for reference gene selection, using conventional candidate genes provides results just as reliable as using genes pre-selected from RNA-Seq data. This is also more cost-effective and feasible when RNA is limited [4].

Q3: How does RNA quality (RIN) specifically impact the agreement between RNA-Seq and qPCR? A: RNA degradation has a widespread and significant effect on RNA-Seq gene expression measurements, often overwhelming biological signals. Principal component analysis shows that a large proportion of variation in RNA-Seq data can be associated with RIN. While qPCR is also affected by severe degradation, it is generally more robust to moderate degradation. Differences in RNA quality between samples can therefore be a major confounder, leading to discordant results [21].

Q4: What are the critical parameters for designing a qPCR assay to minimize technical artifacts? A: Follow these key design rules [17] [18] [19]:

- Primer Length: 18-30 nucleotides.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 60-65°C for primers, with forward and reverse primers within 2°C of each other.

- GC Content: 40-60%. Avoid runs of 4 or more G/C bases.

- Amplicon Length: 70-150 bp is ideal.

- Specificity: Design primers to span an exon-exon junction to avoid genomic DNA amplification.

- Secondary Structures: Check for and avoid primer-dimer formation and hairpins.

Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting RNA-Seq qPCR Discordance

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Human Reference RNA | A standardized RNA pool from multiple cell lines used as a benchmark for platform comparisons [15]. | MAQCA sample in the MAQC consortium studies; ideal for benchmarking RNA-Seq workflows against qPCR [15]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater) | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues by immediately stabilizing cellular RNA, preventing degradation [21]. | Critical for field or clinical sampling where immediate freezing is not possible. Mitigates RIN-related biases [21]. |

| Exon-Spanning qPCR Assays | qPCR primers designed to bind across two exons, with the probe spanning the junction. | Ensures amplification is specific to processed mRNA and not contaminating genomic DNA, improving quantification accuracy [18]. |

| Pre-designed qPCR Assays | Predesigned, validated primer and probe sets for specific gene targets in model organisms. | Saves time and optimization; providers like IDT and Thermo Fisher offer extensive panels for human, mouse, and rat [18]. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Algorithm-based assignment of RNA quality (1-10) from an Agilent Bioanalyzer trace. | Standardized metric to assess sample quality. Low RIN (<6) is associated with significant bias in RNA-Seq [21]. |

| Statistical Algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder) | Software tools to analyze Cq data and determine the most stable reference genes from a candidate set. | Essential for robust qPCR normalization. geNorm provides M-values and determines optimal gene number; NormFinder estimates intra-/inter-group variation [22] [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is RNA-seq analysis of HLA genes particularly challenging? HLA genes are exceptionally polymorphic, meaning they have an extreme number of different sequence versions (alleles) in the human population. Standard RNA-seq analysis involves aligning short sequence reads to a single reference genome. For HLA genes, an individual's specific alleles often differ substantially from this reference, causing reads to misalign or fail to align entirely. Furthermore, the high similarity between different HLA genes (paralogs) can cause reads to map to the wrong gene, biasing expression estimates [5].

My RNA-seq and qPCR results for HLA gene expression are inconsistent. What could be the cause? Moderate correlation between these techniques is a known issue. A 2023 study found correlations (rho) between qPCR and RNA-seq for HLA class I genes ranging from 0.2 to 0.53 [5]. Discordance can arise from:

- Technical Biases: RNA-seq involves library preparation, GC content biases, and alignment issues specific to polymorphic regions [5]. qPCR can have different amplification efficiencies for different alleles.

- Multi-mapping Reads: Short RNA-seq reads that originate from a conserved region of an HLA gene may align equally well to several HLA loci or alleles. Standard pipelines might discard these reads, leading to under-quantification [23].

- PCR Duplicates: In RNA-seq library preparation, PCR amplification can over-represent some transcripts. If not corrected, this can skew expression counts [23].

What are the solutions for accurate HLA expression quantification from RNA-seq? Specialized computational and experimental methods have been developed to address these challenges:

- HLA-Tailored Bioinformatics Pipelines: Tools like seq2HLA and others use custom reference databases containing thousands of known HLA alleles rather than a single genome reference. This improves alignment accuracy for both HLA typing and expression estimation [5] [24].

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporating UMIs during library preparation labels each original mRNA molecule with a unique barcode. This allows bioinformatics pipelines to count only original transcripts and correct for PCR amplification bias, providing more accurate expression levels [23].

- Long-Read Sequencing: Using sequencing technologies that produce longer reads can help because a single read is more likely to cover multiple polymorphic sites, making its alignment to a specific allele more unambiguous [23].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Read Alignment | Low mapping rate to HLA region; multi-mapping reads | Use HLA-specific aligners & customized reference databases of allelic sequences [5] [24]. |

| Expression Quantification | Inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR; allele-specific bias | Employ UMI-based RNA-seq protocols to control for PCR duplicates and improve transcript counting accuracy [23]. |

| Experimental Design | Inability to detect allele-specific expression | Utilize long-read sequencing platforms to span multiple polymorphic sites within a single read [23]. |

| Data Interpretation | Discordant results with published literature or other techniques | Correlate findings with multiple data types (e.g., cell surface protein expression) and account for moderate correlations between techniques [5]. |

The following table summarizes a direct comparison of HLA class I gene expression measurements from a 2023 study that utilized matched samples [5].

| HLA Locus | Correlation (rho) between qPCR & RNA-seq | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-A | 0.53 | Weakest correlation observed among class I genes [5]. |

| HLA-B | 0.36 | Moderate correlation [5]. |

| HLA-C | 0.20 to 0.41 | Range reported; generally shows a moderate correlation [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Method 1: HLA Typing and Expression from Standard RNA-seq Data

This protocol is adapted from the seq2HLA tool, which uses standard RNA-seq fastq files as input [24].

- Input: Obtain RNA-seq reads in fastq format.

- Reference Database: Download a comprehensive database of known HLA allele sequences (e.g., from the ImMunoGeneTics/HLA database). Focus on exons 2 and 3 for class I and exon 2 for class II, as they encode the peptide-binding groove and are most polymorphic.

- Alignment: Map the RNA-seq reads against the HLA reference database using an aligner like Bowtie. Optimize parameters to allow for a limited number of mismatches (e.g., one) to account for sequencing errors while maintaining specificity.

- HLA Typing & Expression: Determine the most likely HLA alleles by analyzing the distribution of reads across possible alleles. A confidence score (P-value) is calculated for each call. Expression is quantified based on the number of reads uniquely mapping to each locus [24].

Method 2: Allele-Specific Expression Quantification Using UMIs

This protocol, based on a 2021 study, uses UMIs for precise, bias-corrected quantification [23].

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from fresh PBMCs or other tissues. Assess RNA quality (e.g., using RIN score).

- Reverse Transcription with Template Switching: Synthesize first-strand cDNA using a primer that binds to the poly-A tail and includes a UMI. A template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) is used to ensure full-length transcript representation. At this stage, every original mRNA molecule is tagged with a unique UMI.

- cDNA Amplification & HLA Target Enrichment: Amplify the cDNA using PCR. Then, use a set of gene-specific primers for HLA class I (A, B, C) and class II (DRA, DRB1, DPA1, DPB1, DQA1, DQB1) genes to perform a target enrichment PCR.

- Sequencing & Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence the enriched HLA amplicons. In the bioinformatics pipeline, group reads by their UMI to identify and collapse PCR duplicates. Align the unique reads to an HLA reference to calculate the number of original mRNA molecules for each allele [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| HLA Allele Database (e.g., IMGT/HLA) | A curated collection of all known HLA sequences; essential as a reference for alignment and typing [24]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to tag individual mRNA molecules; enables correction for PCR amplification bias [23]. |

| Template-Switching Oligo (TSO) | Used in reverse transcription to ensure full-length cDNA synthesis, improving coverage of the 5' end of transcripts [23]. |

| STRT-V3-T30-VN Oligo | A primer used in the first-strand cDNA synthesis; designed to bind to the poly-A tail and anchor the reverse transcription [23]. |

| HLA-Specific Bioinformatics Pipelines (e.g., seq2HLA) | Computational tools designed specifically to handle the alignment and quantification challenges posed by polymorphic genes like HLA [5] [24]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The diagram below illustrates the core problem of analyzing HLA genes with RNA-seq and the two main methodological solutions.

The diagram below outlines the specific steps for the UMI-based wet-lab protocol, a key solution for allele-specific expression quantification.

Navigating Technical Pitfalls: Method-Specific Challenges in Complex Applications

RNA-seq Alignment Issues in Polymorphic Regions and Gene Families

Why does RNA-seq alignment fail in polymorphic regions and gene families, and how can this lead to discordant results with qPCR?

RNA-seq alignment in polymorphic regions and gene families is challenging due to the fundamental limitations of aligning short reads to a single reference genome. These challenges can create a systematic technical bias that explains discordance between RNA-seq and qPCR results.

The primary issues are:

- Reference Bias and Missing Features: Standard RNA-seq pipelines align all data to a single reference genome, which does not represent the genetic diversity of a species. If a gene that is transcribed is not represented in the reference genome, the RNA-seq reads from that gene can misalign to the closest available gene, inflating its counts and providing misleading data. Conversely, genes present in the sample but missing from the reference will have no counts [25].

- Multi-mapped Reads and Ambiguity: Gene families with high sequence similarity (e.g., Major Histocompatibility Complex or killer-immunoglobulin-like receptors) result in reads that can align equally well to multiple genomic locations. Most standard pipelines either discard these multi-mapped reads or assign them randomly, resulting in lost data and inaccurate quantification [25] [26].

- Alignment Errors Between Repeats: Splice-aware aligners like STAR and HISAT2 can introduce erroneous spliced alignments between nearby repeated sequences, creating falsely spliced transcripts or "phantom" introns. This is particularly problematic in genomes with high repetitive content [27].

- Annotation Incompleteness: Complex genomic regions are often difficult to assemble and annotate accurately. If a gene is not annotated in the reference, it will be systematically under-counted in RNA-seq analyses that rely on these annotations for read assignment [25].

These alignment issues can directly cause qPCR discordance because qPCR typically uses targeted primers that may successfully amplify sequences that are missed or misassigned during RNA-seq's genome-wide alignment process.

Which advanced algorithms and tools can resolve alignment ambiguities in complex genomic regions?

Table: Specialized Tools for Resolving RNA-seq Alignment Challenges

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Specific Problem Addressed | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| nimble [25] | Supplemental alignment and quantification | Complex immune genotyping, missing features | Uses pseudoalignment with customizable gene spaces and scoring criteria tailored to specific gene families. |

| EASTR [27] | Alignment error correction | Spurious spliced alignments in repeats | Detects falsely spliced alignments by analyzing sequence similarity between intron-flanking regions. |

| RUM [28] | Comprehensive alignment pipeline | Robust alignment across diverse challenges | Three-stage pipeline combining Bowtie (genome/transcriptome) and BLAT alignment, then merging results. |

| BEERS [28] | RNA-seq simulation and benchmarking | Algorithm evaluation and comparison | Simulates RNA-seq data with configurable error rates and polymorphisms for benchmarking aligners. |

Specialized algorithms like nimble address these limitations by moving away from the "one-size-fits-all" reference approach. Instead, nimble processes RNA-seq data using custom, focused gene spaces tailored to the biology of specific gene families. It can apply different scoring criteria to different gene sets, which is crucial for accurately quantifying highly variable gene families like MHC and immunoglobulin genes [25].

For correcting systematic alignment errors, EASTR (Emending Alignments of Spliced Transcript Reads) identifies and removes falsely spliced alignments that occur between repetitive sequences. It works by extracting sequences flanking splice junctions and assessing their similarity and frequency in the genome, effectively distinguishing true splicing events from alignment artifacts [27].

What is the step-by-step protocol for implementing a supplemental alignment pipeline?

The following workflow diagram illustrates a robust strategy that integrates standard RNA-seq alignment with specialized tools for handling problematic regions:

Detailed Protocol: Implementing nimble for Supplemental Alignment

Step 1: Define Custom Gene Spaces

- Compile reference sequences for problematic gene families not well-represented in the standard reference. For immunology research, this includes MHC class I and II alleles, KIR genes, and immunoglobulin chains [25].

- For non-model organisms or incomplete annotations, include genes known to be missing from the reference annotation. In rhesus macaque studies, this included adding CD27 and IGHD genes missing from the MMul_10 genome annotation [25].

- Format references as FASTA files, with each sequence representing a distinct gene or feature.

Step 2: Run nimble Supplemental Alignment

- Execute nimble using the custom gene spaces and the same BAM files from your standard alignment.

- Example command structure:

- nimble uses a pseudoalignment approach that processes either bulk- or single-cell RNA-seq data against these custom references with tailored scoring logic [25].

Step 3: Merge and Validate Results

- Combine counts from standard and supplemental pipelines, giving priority to nimble-derived counts for genes in custom spaces.

- Validate alignment improvement using positive controls: check for recovery of expression in previously missing genes and reduction in misalignment to homologous regions.

- For a comprehensive solution, apply EASTR to the standard BAM files before quantification to remove spurious spliced alignments [27].

Performance Considerations: A benchmark test aligning 491 million paired-end reads to a ~2,200-feature MHC reference completed in 225 minutes on 18 CPUs, sustaining approximately 36,000 reads/second [25].

How can I validate that alignment issues are causing my RNA-seq and qPCR discordance?

Table: Validation Strategies for Alignment-Related Discordance

| Validation Approach | Experimental Method | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Re-sequencing | Design qPCR assays for regions with suspected alignment issues. Compare results to RNA-seq counts. | Concordance after pipeline correction confirms alignment artifacts as the primary cause of discordance. |

| Spike-in Controls | Add synthetic RNA controls with known sequences to the sample before library prep. | Systematic under-counting of spike-ins with sequences absent from the reference indicates reference bias. |

| Orthogonal Alignment | Re-align problematic reads using a different algorithm (e.g., BLAT-based pipeline like RUM). | Recovery of "missing" expression with alternative aligners confirms algorithmic limitations in primary pipeline. |

| Long-Read Sequencing | Supplement with long-read RNA-seq (PacBio Iso-Seq) for problematic genes. | Long reads provide unambiguous alignment and can reveal missed isoforms or genes in short-read data. |

A robust validation strategy should include both computational and experimental approaches:

Computational Validation:

- Use the BEERS simulator [28] to create benchmark datasets with known polymorphisms and splice variants. Process these through your alignment pipeline and measure the false negative/positive rates for genes in polymorphic regions.

- Apply EASTR [27] to your alignment files and quantify how many splice junctions are flagged as potentially erroneous. A significant improvement in qPCR concordance after filtering indicates alignment artifacts were a major factor.

- Implement the nimble pipeline [25] with custom gene spaces for your problematic targets. Recovery of expression signals that were missing in standard alignment provides strong evidence of reference bias.

Experimental Validation:

- For genes showing discordance, design qPCR assays that target the exact regions where RNA-seq shows alignment problems. If qPCR detects expression where RNA-seq does not, this confirms technical rather than biological discordance.

- For critical experiments, consider PacBio Iso-Seq or Kinnex Full-Length RNA sequencing, which are superior for qualitative endpoints like alternative splicing and novel transcript detection, though more expensive than short-read approaches [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Mix [11] | External RNA controls for standardization | 92 synthetic transcripts at known concentrations; use to determine sensitivity, dynamic range, and technical variation. |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) [11] | Correct PCR bias and errors | Tag original cDNA molecules to identify and correct for amplification biases; recommended for deep sequencing (>50M reads/sample). |

| Ribo-Depletion Kits [29] | Remove ribosomal RNA | Essential for bacterial RNA-seq, degraded samples (FFPE), or when studying non-polyadenylated RNAs. |

| Strand-Specific Library Kits [29] | Preserve strand orientation | Critical for analyzing antisense transcription and overlapping genes; dUTP method is widely used. |

| iHSMGC (integrated Human Skin Microbial Gene Catalog) [30] | Skin-specific microbial gene reference | Example of a specialized reference catalog; demonstrates importance of domain-specific references. |

| Custom Nimble Gene Spaces [25] | Targeted alignment references | User-defined FASTA files containing sequences for problematic gene families or missing features. |

qPCR Primer/Probe Design Specificity and Amplification Efficiency

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I ensure my qPCR primers are specific and avoid amplifying genomic DNA?

Issue: Non-specific amplification or amplification from genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination leads to inaccurate quantification, a critical technical pitfall in validating RNA-Seq data.

Solutions:

- Design Primers Across Exon-Exon Junctions: This is the most effective strategy. By designing your amplicon to span the boundary between two exons, the primer pair will not efficiently bind to or amplify contaminating gDNA, which contains introns [31] [32] [33]. For even greater specificity, place the probe (rather than a primer) over the exon-exon junction [32].

- Perform a BLAST Analysis: Always check your primer and probe sequences for specificity using a tool like NCBI BLAST. This ensures the oligonucleotides are unique to your target transcript and will not anneal to homologous genes, pseudogenes, or other non-target sequences [32] [34] [33].

- Utilize Bioinformatics Pipelines: Use established design software (e.g., Primer-BLAST, OligoArchitect, Beacon Designer) that incorporates rigorous checks for sequence uniqueness and secondary structures [31] [32] [33].

- Include Proper Controls: Run a no-reverse transcription (No-RT) control for each sample to detect any residual gDNA amplification. A signal in the No-RT control indicates gDNA contamination [32].

FAQ 2: What are the key design parameters for achieving high amplification efficiency?

Issue: Low amplification efficiency results in inaccurate quantification, poor replicate consistency, and reduced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts, directly contributing to technical discordance with RNA-Seq data.

Solutions: Adhere to the following design parameters for both primers and probes to ensure efficiency between 90–110% [35]:

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for qPCR Oligonucleotides

| Parameter | Primer Specification | Probe Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 15–30 nucleotides [35] | 15–30 nucleotides [35] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 58–60°C [32] [34] | ~10°C higher than primers [35] [34] |

| Tm Difference (Fwd vs Rev) | Within 1–3°C [31] [35] | - |

| GC Content | 40–60% [31] [35] [33] | 40–60% [35] |

| Amplicon Length | 70–150 base pairs is ideal [31] [35] [32] | - |

| 3' End | Avoid runs of G/C; no more than 2 G/C in last 5 bases [32] | - |

Additional critical considerations:

- Avoid Secondary Structures: Ensure primers and probes do not form hairpins or self-dimers, and that primer pairs do not form dimer complexes [35] [33].

- Optimize Concentrations: Use recommended concentrations (e.g., 100–500 nM for primers in dye-based assays; 200–900 nM for probe-based assays) and perform optimization if necessary [35] [32].

- Check Sequence Quality: Avoid templates with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or repetitive sequences at the binding sites [32] [34] [33].

FAQ 3: My no-template control (NTC) shows amplification. What went wrong?

Issue: Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination or primer-dimer formation, compromising the integrity of the entire dataset.

Solutions:

- Prevent Contamination:

- Prevent Primer-Dimer:

- Redesign primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity between the forward and reverse primers [35].

- Optimize primer concentrations to the lowest effective level [35].

- Include a melt curve analysis at the end of the run. Primer-dimer formation typically appears as a peak with a lower melting temperature than the specific product [13].

FAQ 4: My assay has high Ct values and poor efficiency. How can I optimize it?

Issue: High Ct values and efficiency outside the 90–110% range indicate suboptimal assay performance, reducing the reliability of quantitative data.

Solutions:

- Verify Template Quality: Use high-quality, pure RNA/DNA. Assess RNA integrity and purity (A260/A280 ratio of ~1.9–2.0) before reverse transcription [36] [13].

- Check Reagent Integrity: Ensure reagents are fresh and have not undergone excessive freeze-thaw cycles. Degraded primers or probes can cause late amplification [36].

- Validate Primer Efficiency Empirically: Test your primers by running a standard curve with a serial dilution (at least 3 logs) of template. Calculate efficiency using the formula: Efficiency % = (10[−1/slope] − 1) × 100. Aim for an R² value ≥ 0.99 [35].

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Perform a temperature gradient PCR to determine the ideal annealing temperature that maximizes specificity and yield [37].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Standard Workflow for qPCR Assay Design and Validation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for designing and validating a specific and efficient qPCR assay.

Objective: To design, optimize, and validate a primer/probe set for accurate gene expression quantification.

Workflow Diagram: qPCR Assay Design and Validation Workflow

Materials:

- Template: High-quality cDNA or gDNA.

- Oligonucleotides: Synthesized forward primer, reverse primer, and probe (if using probe-based chemistry).

- qPCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts. For SYBR Green or probe-based detection.

- qPCR Instrument: A real-time PCR cycler with appropriate detection channels.

- Software: Sequence analysis software (e.g., Primer-BLAST), instrument control and analysis software.

Procedure:

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the correct mRNA reference sequence (RefSeq) for your gene and organism from a curated database like NCBI Gene [31].

- In-silico Design:

- Input the sequence into a primer design tool (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST).

- Apply the parameters listed in Table 1. Crucially, select the option "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" [31].

- The tool will output several candidate primer pairs. Select one where the 3' ends avoid G/C runs and the sequences have minimal self-complementarity.

- Specificity Check: Perform a BLAST search on the selected primer and probe sequences to confirm they are unique to the target gene [32] [33].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Order the selected primers and probe. Resuspend them accurately in sterile water or TE buffer to create concentrated stock solutions (e.g., 100 µM for primers, 10 µM for probe). Dilute to working concentrations based on master mix recommendations [34].

- Empirical Validation:

- Standard Curve: Prepare a 5- or 10-fold serial dilution of a template known to contain the target sequence (e.g., a high-quality cDNA pool). Run the qPCR assay with these dilutions in triplicate.

- Melt Curve (for SYBR Green assays): After the amplification cycles, run a melt curve to check for a single, specific product.

- Data Analysis:

- Efficiency and Linear Dynamic Range: The instrument software will generate a standard curve. Calculate the PCR efficiency from the slope. Acceptable criteria: Efficiency = 90–110%; R² ≥ 0.99 [35].

- Specificity: The melt curve should show a single, sharp peak. The presence of multiple peaks indicates non-specific amplification or primer-dimer [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for qPCR Assay Development

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Predesigned TaqMan Assays | Pre-optimized, highly specific primer/probe sets; save time and minimize optimization efforts [32] [34]. |

| Custom Assay Design Services | Bioinformatics-driven custom design (e.g., Thermo Fisher's Custom Plus); ensures optimal Tm, GC content, and specificity checks [32]. |

| Hot-Start PCR Master Mix | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by inhibiting polymerase activity at low temperatures [37]. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Treats RNA samples to remove genomic DNA contamination prior to reverse transcription, preventing false positives [32] [13]. |

| UDG (Uracil-DNA Glycosylase) Treatment | Prevents carryover contamination from previous PCR products by degrading uracil-containing DNA prior to thermocycling [35]. |

| High-Quality Nucleic Acid Purification Kits | Ensures high-purity RNA/DNA templates free of inhibitors, which is critical for robust and reproducible amplification [36] [37]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Discordance Between qPCR and RNA-Seq for HLA Gene Expression Quantification

Problem: Measurements of HLA gene expression levels show inconsistent or conflicting results when comparing qPCR and RNA-seq data from the same sample.

Explanation: The extreme polymorphism of HLA genes presents unique technical challenges for each method. qPCR relies on pre-designed primers that may have variable hybridization efficiency across different HLA alleles. RNA-seq involves aligning short reads to a reference genome that does not fully represent HLA allelic diversity, causing mapping errors and cross-alignments between paralogs [5].

Solution:

Table 1: Key Challenges and Solutions for HLA Expression Quantification

| Challenge | Impact on qPCR | Impact on RNA-seq | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Polymorphism | Primer-binding efficiency varies by allele, reducing accuracy [5]. | Short reads fail to align or misalign to reference [5]. | Use allele-specific qPCR primers. For RNA-seq, use HLA-tailored pipelines (e.g., HLAProfiler, OptiType) that incorporate known HLA diversity [5]. |

| Sequence Similarity (Paralogs) | Potential for cross-amplification of related HLA genes [5]. | Reads cross-align between related genes (e.g., HLA-A, -B, -C), biasing quantification [5]. | Design primers/probes in highly divergent gene regions. Employ bioinformatic tools that minimize cross-mapping. |

| Data Correlation | Moderate correlation with RNA-seq (e.g., Spearman's rho 0.2–0.53 for HLA class I) [5]. | Moderate correlation with qPCR; different molecular phenotypes [5]. | Interpret results with caution; neither method is a "gold standard." Correlate with cell surface expression (e.g., flow cytometry) when possible [5]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Validating HLA Expression with an Integrated Approach

- Sample Preparation: Extract high-quality RNA from PBMCs using a kit such as RNeasy, including a DNase treatment step to remove genomic DNA [5].

- qPCR Analysis:

- Use validated, allele-specific primers and probes where possible.

- Run reactions in replicates and use a data handling pipeline that categorizes results as "valid," "invalid," or "undetectable" to improve robustness, especially for low-abundance targets [38].

- RNA-seq Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Prepare libraries using standard protocols (e.g., Illumina).

- Sequence to sufficient depth to capture low-expressed alleles.

- Bioinformatic Analysis with HLA-Tailored Pipeline:

- Do not rely on standard RNA-seq alignment alone.

- Use a specialized tool like

HLAProfilerorArcasHLAto accurately quantify allele-specific expression [5].

- Correlation and Validation:

- Statistically compare expression estimates (e.g., Spearman correlation) for HLA-A, -B, and -C from qPCR and RNA-seq.

- Where feasible, validate key findings by measuring HLA cell surface protein expression using flow cytometry with specific antibodies [5].

Guide 2: Detecting Fusion Genes and Isoforms in Oncology

Problem: Low sensitivity for detecting rare fusion transcripts or inability to resolve the full structure and sequence of fusion isoforms, particularly when they are lowly expressed or present in a background of non-cancerous cells.

Explanation: Conventional methods like FISH and RT-PCR are highly sensitive but typically target only one specific fusion, potentially missing novel or unexpected events. Standard RNA-seq offers unbiased discovery but may lack the sensitivity to detect fusions expressed at low levels or in heterogeneous tumor samples [39]. Precise determination of fusion junctions and full-length isoform sequences is challenging with short-read sequencing [40].

Solution:

Table 2: Comparison of Fusion Gene Detection Methods

| Method | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Isoform Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| FISH / RT-PCR | High sensitivity for known fusions [39]. | Targeted; cannot discover novel fusions [39]. | Low (RT-PCR can detect known isoforms). |

| Standard RNA-seq | Genome-wide, unbiased discovery [39]. | Low sensitivity for rare fusions; short reads cannot resolve complex isoforms [39] [40]. | Limited to fusion junction; not full-length. |

| Targeted RNA-seq | Enriches for genes of interest; greatly increases sensitivity for low-abundance fusions [39]. | Panel design dictates scope of discovery. | Limited to fusion junction; not full-length. |

| Hybrid Sequencing (IDP-fusion) | Uses long reads to span full-length transcripts and short reads for accuracy; provides isoform-level resolution [40]. | Higher cost and computational burden. | High. Identifies and quantifies specific fusion isoforms. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Fusion Gene Detection via Targeted RNA-Seq [39]

- Panel Design: Design biotinylated oligonucleotide capture probes targeting exons of hundreds of genes known to be involved in fusion events in your cancer of interest (e.g., 188 genes for hematological malignancies, 241 for solid tumors).

- Library Preparation and Capture:

- Convert total RNA to a sequencing library.

- Hybridize the library to the custom probe panel and perform capture (a double-capture can increase the on-target rate to >90%).

- Sequence the enriched library.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align reads to the reference genome.

- Use a fusion detection pipeline that employs multiple algorithms (e.g., STAR-Fusion and FusionCatcher) and require calls to be supported by both to reduce false positives [39].

- Manually review integrated genomics viewer (IGV) plots for validation.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Characterizing Fusion Isoforms with Hybrid Sequencing (IDP-fusion) [40]

- Sequencing: Generate both long-read (PacBio) and short-read (Illumina) sequencing data from the same sample.

- Fusion Detection:

- Align long reads to the reference genome using an aligner like GMAP.

- Identify "fusion long reads" that can be split and mapped to two different genes.

- Precise Junction Calling:

- Construct "Artificial Reference Sequences" (ARSs) around the candidate fusion junction from the long-read data.

- Re-map high-accuracy short reads to the ARS to determine the precise fusion site at single-nucleotide resolution.

- Isoform Identification and Quantification:

- Use the IDP-fusion tool to integrate long- and short-read data.

- Reconstruct full-length fusion transcripts and quantify their abundance (e.g., in RPKM).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why might my qPCR results show high mRNA levels for an HLA gene, but Western blot shows low protein? A: This is a common biological discrepancy, not necessarily a technical failure. Key reasons include:

- Temporal Delay: Transcription (mRNA) precedes translation (protein). An mRNA peak at 6 hours post-stimulus may not result in detectable protein until 24 hours [41].

- Translational Regulation: miRNA-mediated repression or global suppression under stress can inhibit mRNA translation [41].

- Protein Degradation: Short-lived proteins may be rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, preventing accumulation despite high mRNA levels [41].

Q2: My single-cell RNA-seq experiment on a non-model organism yielded very different results when I aligned to two different genome assemblies. Why? A: This is a critical, often-overlooked issue. Discordant genome assemblies can drastically alter scRNAseq interpretation [42]. Differences in assembly completeness, contiguity, and especially annotation quality (e.g., of 3' UTRs, critical for scRNAseq) can cause:

- Varying numbers of cells and genes detected.

- Assembly-specific "marker" genes.

- Differential expression patterns for the same gene [42].

- Solution: Align your data to each available assembly separately, then use integration tools (e.g., Seurat) to combine the resulting datasets for a more accurate and complete analysis [42].

Q3: Targeted RNA-seq for fusions didn't find a fusion that was previously suspected. What could be wrong? A:

- Panel Design: Verify that both partner genes of the suspected fusion are covered by the capture probes in your panel.

- Expression Level: The fusion transcript might be expressed at very low levels. Check the sensitivity (limit of detection) of your panel and consider diluting the sample with a fusion-positive cell line (e.g., K562 for BCR-ABL1) to establish this [39].

- Sample Quality: Ensure the RNA integrity is high and the tumor content in the sample is sufficient.

- Bioinformatics: Check the raw data and alignment in a genome browser to see if there is any supporting evidence that might have been filtered out by stringent algorithms.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-Tailored Bioinformatics Pipelines | Accurately quantify allele-specific expression from RNA-seq data by accounting for polymorphism [5]. | HLAProfiler, ArcasHLA, OptiType. |

| Targeted RNA-seq Panels | Sensitive detection of fusion transcripts by enriching for hundreds of cancer-related genes prior to sequencing [39]. | Custom panels for hematological malignancies or solid tumors. |

| Hybrid Sequencing Analysis Tools | Integrate long-read and short-read data to accurately detect fusion genes and identify full-length fusion isoforms [40]. | IDP-fusion. |

| Fusion Gene Detection Algorithms | Identify fusion events from RNA-seq data; using multiple tools increases confidence [39]. | STAR-Fusion, FusionCatcher. |

| Spike-In Controls | Quantify sensitivity, enrichment efficiency, and detection limits of sequencing assays [39]. | ERCC RNA spike-ins, fusion sequins. |

| Cell Lines with Known Fusions | Positive controls for validating fusion detection methods [39] [40]. | K562 (BCR-ABL1), RDES (EWSR1-FLI1). |

| HLA-Fc Fusion Proteins | Investigate antigen-specific immune modulation; potential for therapeutic application in transplantation [43]. | Recombinant proteins combining HLA extracellular domains with IgG Fc. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated HLA Expression Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Fusion Gene & Isoform Detection via Hybrid Sequencing

The Role of Long-Read RNA-seq in Mitigating Short-Read Limitations

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has transformed molecular biology, but short-read RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has inherent limitations that long-read technologies are uniquely positioned to address [44]. Short-read platforms (e.g., Illumina) generate fragments of 50-300 base pairs, which is significantly shorter than the average human mRNA (approximately 3 kb) [45]. This fundamental discrepancy means short-read workflows must fragment mRNA molecules before sequencing, losing connectivity between distant exons and making it challenging to reconstruct full-length transcript isoforms [45]. The inability to directly sequence complete transcripts has been a major bottleneck in transcriptomics.

Long-read RNA-seq platforms, primarily Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), enable end-to-end sequencing of full-length mRNA molecules in a single read [45] [46]. By capturing complete transcripts without fragmentation, long-read technologies provide a transformative approach for investigating RNA species and features that cannot be reliably interrogated by short-read methods [45] [47]. This capability is particularly crucial for resolving the complex landscape of human transcriptomes, where an estimated 300,000 unique protein isoforms can be encoded from approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes [45].

Table 1: Core Technological Differences Between Sequencing Platforms

| Feature | Illumina Short-Read RNA-seq | PacBio Long-Read RNA-seq | ONT Long-Read RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50–300 bp [45] | Up to 25 kb [45] | Up to 4 Mb [45] |

| Base Accuracy | 99.9% [45] | 99.9% (HiFi) [45] | 95%–99% (R10.4 chemistry) [45] |

| Throughput | 65–3,000 Gb per flow cell [45] | Up to 90 Gb per SMRT cell [45] | Up to 277 Gb per PromethION flow cell [45] |

| Key Strength | High throughput, low cost per base | High-fidelity consensus sequences | Direct RNA sequencing, detection of modifications |

| Primary Limitation Addressed | N/A (baseline) | Resolves isoform ambiguity | Captures full-length transcripts and modifications |

Technical FAQs: Resolving Experimental Challenges and Discordance

FAQ 1: How does long-read RNA-seq help resolve discrepancies between qPCR and Western blot results?

Discordance between qPCR (measuring mRNA levels) and Western blot (measuring protein levels) is a common experimental challenge with multiple potential causes [41]. Long-read RNA-seq provides crucial insights that help explain these discrepancies by revealing transcript isoform diversity that short-read methods and qPCR cannot detect.

Key resolution mechanisms:

- Isoform-specific effects: Different transcript isoforms may have varying translational efficiencies, stability, or subcellular localization [45]. Long-read sequencing can identify which specific isoforms are present and quantify their expression.

- Non-functional transcripts: qPCR may detect mRNA isoforms that appear present but contain features preventing efficient translation (e.g., retained introns, premature stop codons) [45] [48]. Long-read sequencing can identify these non-productive isoforms.

- Alternative splicing impact: The protein product detected by Western blot may derive from a specific isoform that qPCR assays cannot distinguish from other splice variants [41]. Long-read sequencing provides full-length context to correlate protein products with specific mRNA isoforms.

FAQ 2: What are the main experimental considerations when implementing long-read RNA-seq?

Successful long-read RNA-seq requires attention to several technical aspects that differ from short-read approaches:

Sample Quality and Handling:

- RNA Integrity: Use high-quality, intact RNA without degradation [49]. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and RNase contamination.

- Sample Preparation: Optimize homogenization conditions and use appropriate TRIzol volumes to prevent incomplete RNA precipitation or DNA contamination [49].

Platform Selection Criteria:

- PacBio HiFi: Choose for applications requiring high base accuracy (99.9%), such as small variant detection or when exceptional consensus accuracy is needed [45] [46].

- Oxford Nanopore: Select for direct RNA sequencing, detection of RNA modifications, or when ultra-long reads are prioritized [45] [46]. ONT also offers higher throughput at lower cost [45].

Experimental Design:

- Coverage Depth: Long-read sequencing typically requires less depth than short-read for isoform discovery because each read represents a full-length transcript [45].

- Replication: Maintain appropriate biological replicates despite higher cost per sample to ensure statistical robustness [45].

FAQ 3: What computational tools are available for long-read RNA-seq analysis, and how do I choose?

Multiple computational tools have been developed specifically for long-read RNA-seq data analysis, each with different strengths [45] [50].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Long-Read RNA-Seq Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLAIR [50] | Transcript reconstruction & quantification | Four-step pipeline: align, correct, collapse, quantify | Users seeking a complete, benchmarked workflow |

| IsoQuant [45] [50] | Isoform discovery & quantification | High accuracy for known and novel isoforms | Projects requiring precise isoform identification |

| StringTie2 [45] | Transcript assembly & quantification | Improved assembly with long reads | Users familiar with short-read transcript assembly |

| ESPRESSO [45] | Transcript discovery | Aggregates information across reads to refine alignments | Reliable discovery of novel transcript isoforms |

| Bambu [45] | Transcript discovery | Uses machine learning to identify novel transcripts | Reference-based novel transcript discovery |

Selection Guidance:

- For comprehensive analysis: FLAIR provides an end-to-end solution from alignment to quantification [50].

- For maximum accuracy: IsoQuant performs well in benchmarks for both known and novel isoform detection [45] [50].

- For novel isoform discovery: ESPRESSO and Bambu specialize in identifying previously unannotated transcripts [45].

- The LRGASP Consortium benchmark found no single tool excels in all scenarios; choice depends on specific study objectives [45].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Long-Read Transcriptomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Long-Read RNA-Seq

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Sequel II/IIe [45] [46] | High-fidelity long-read sequencing | Provides 99.9% accuracy with 15-25 kb reads; ideal for variant detection and isoform validation |

| Oxford Nanopore PromethION [45] [46] | High-throughput long-read sequencing | Enables direct RNA sequencing and modification detection; higher throughput at lower cost |

| TRIzol/RNA Extraction Reagents [49] | High-quality RNA isolation | Critical for obtaining intact, non-degraded RNA; must be RNase-free |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | mRNA enrichment | Isulates polyadenylated transcripts for cDNA synthesis |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | Library preparation | Creates full-length cDNA for sequencing; critical for capturing complete transcripts |

| RNase Inhibitors [49] | Sample protection | Prevents RNA degradation during sample processing and storage |

| FLAIR Pipeline [50] | Computational analysis | Complete workflow for transcript identification and quantification from long reads |

| SQANTI3 [50] | Quality control & curation | Filters and characterizes transcript models based on multiple quality metrics |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Yield in Long-Read RNA Sequencing

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: RNA degradation [49]

- Solution: Use RNase-free reagents and equipment, wear gloves, work in dedicated clean areas, and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles

- Cause: Incomplete solubilization of RNA [49]

- Solution: Control ethanol drying time to avoid over-drying, heat at 55-60°C for 2-3 minutes, or increase dissolution time

- Cause: Genomic DNA contamination [49]

- Solution: Reduce starting sample volume, increase lysis reagent volume, use reverse transcription reagents with genome removal modules

Problem: High Error Rates in Sequence Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Platform-specific error profiles [45]

- Solution: Choose PacBio HiFi for high-accuracy applications or apply circular consensus sequencing to generate consensus reads

- Cause: Library preparation artifacts

- Solution: Optimize PCR cycles to reduce amplification bias, use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish biological variants from technical artifacts

Problem: Difficulty Identifying True Transcript Isoforms

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Computational pipeline limitations [45] [50]

- Solution: Implement orthogonal validation using short-read data or reference annotations in tools like FLAIR-correct

- Cause: Inadequate read depth for low-abundance isoforms [45]

- Solution: Increase sequencing depth or use targeted approaches to enrich for specific transcripts of interest

- Cause: Artifactual transcripts from library preparation [50]

- Solution: Use SQANTI3 to filter transcripts based on multiple quality metrics and orthogonal support data

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Technical Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Flow cell variability (ONT) or SMRT cell variability (PacBio)

- Solution: Process replicates using the same flow cell/SMRT cell when possible, or normalize across runs using control RNAs

- Cause: RNA quality differences between samples [49]

- Solution: Standardize RNA extraction protocols, use quality control metrics (RIN scores) to ensure consistent input quality

Advanced Applications: Leveraging Long-Read RNA-seq for Complex Biological Questions

Long-read RNA-seq enables several advanced applications that are challenging or impossible with short-read approaches:

Full-Length Transcript Discovery and Quantification

Long-read RNA-seq directly sequences complete transcripts, eliminating the need for computational assembly and enabling precise characterization of alternative splicing events, alternative transcriptional start sites, and alternative polyadenylation sites [45]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying complex gene families and poorly annotated genomes where transcript diversity remains incompletely characterized.

Detection of Novel RNA Species and Features

The technology enables comprehensive discovery of various RNA features that are difficult to detect with short reads:

- Circular RNAs: Formed through back-splicing of pre-mRNAs [45]

- Chimeric RNAs: Generated from trans-splicing between distant genes or readthrough transcription [45]

- Transposable element-derived transcripts: Activated under specific physiological or pathological conditions [45]

- RNA modifications: ONT's direct RNA sequencing can detect various chemical modifications including m6A, m5C, and pseudouridine without additional chemical treatments [45]

Resolving Genetic Regulation in Disease

Long-read RNA-seq has proven particularly valuable in disease research. For example, the isoform-centric microglia genomic atlas (isoMiGA) project used long-read sequencing to identify 35,879 previously unknown microglia isoforms and discovered associations between specific isoforms and genetic risk loci for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [48]. This demonstrates how long-read sequencing can reveal disease mechanisms hidden from short-read technologies.

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

In clinical settings, long-read RNA-seq enables:

- Fusion transcript detection in cancer research with precise breakpoint identification [46]

- Complete isoform characterization for biomarker discovery [44]

- Allele-specific expression analysis through haplotype phasing [46]

- Antigen receptor and biomarker isoform discovery for immunotherapy development [46]

Long-read RNA-seq represents a foundational shift in transcriptomics, providing unprecedented capability to explore the full complexity of transcriptomes in health and disease. By addressing the fundamental limitations of short-read approaches, it enables researchers to move beyond gene-level expression analysis to comprehensive isoform-level understanding, ultimately helping to resolve longstanding experimental discrepancies and uncover new biological mechanisms.