RNA-Seq and qPCR Fold Change Correlation: A Comprehensive Guide for Rigorous Gene Expression Validation

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on correlating fold change measurements between RNA-Seq and qPCR.

RNA-Seq and qPCR Fold Change Correlation: A Comprehensive Guide for Rigorous Gene Expression Validation

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on correlating fold change measurements between RNA-Seq and qPCR. It covers the foundational principles explaining the relationship between these techniques, state-of-the-art methodological pipelines for data analysis, troubleshooting strategies for common discordance issues, and a modern framework for experimental validation. By synthesizing findings from recent large-scale consortium studies and current best practices, this resource aims to empower scientists to design more robust gene expression studies, improve reproducibility, and make informed decisions about when and how to validate high-throughput transcriptomic data.

Understanding the Relationship: Why RNA-Seq and qPCR Fold Change Measurements Correlate

Quantifying gene expression is fundamental to molecular biology, with quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) serving as cornerstone technologies. While both methods measure RNA transcript abundance, they differ profoundly in their technical principles, capabilities, and the nature of the expression data they generate. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers designing experiments, particularly in studies correlating fold-change (FC) measurements between techniques. qPCR, also known as RT-qPCR, is a targeted, low-to-medium throughput method that provides highly sensitive and precise quantification of a predefined set of genes [1]. In contrast, RNA-Seq is a comprehensive, high-throughput approach that enables genome-wide expression profiling without requiring prior knowledge of the transcriptome, offering both quantitative expression data and insights into transcript diversity [2] [1]. The extreme polymorphism of certain gene families, such as the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci, presents unique challenges for RNA-Seq quantification due to difficulties in aligning short reads to a reference genome that doesn't capture full allelic diversity, potentially affecting expression estimation accuracy [3]. This guide objectively compares the technical foundations of these methods, explores the correlation in their expression measurements, and provides experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals working within the broader context of RNA-Seq and qPCR fold-change correlation research.

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

The core processes of qPCR and RNA-Seq involve converting RNA into a measurable signal, but their pathways diverge significantly after initial RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

qPCR Workflow: Amplification and Detection in Real Time

In qPCR, the analysis targets specific, known sequences. After reverse transcribing RNA into cDNA, gene-specific primers amplify the target sequences. The key to quantification is monitoring the amplification process in real-time using fluorescent dyes or probes. The cycle at which the fluorescence crosses a threshold (Cq value) is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target transcript, enabling relative or absolute quantification [1].

RNA-Seq Workflow: High-Throughput Sequencing and Mapping

RNA-Seq is a more complex process that sequences the entire transcriptome population. After cDNA synthesis, fragments are sequenced en masse using high-throughput platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, Element Biosciences AVITI), generating millions of short reads [2] [4]. These reads are then computationally aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome, and the number of reads mapping to each gene or transcript is counted. This raw count data forms the basis for expression quantification, such as in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) or Counts Per Million (CPM), which must be normalized to account for factors like sequencing depth and gene length [2] [5].

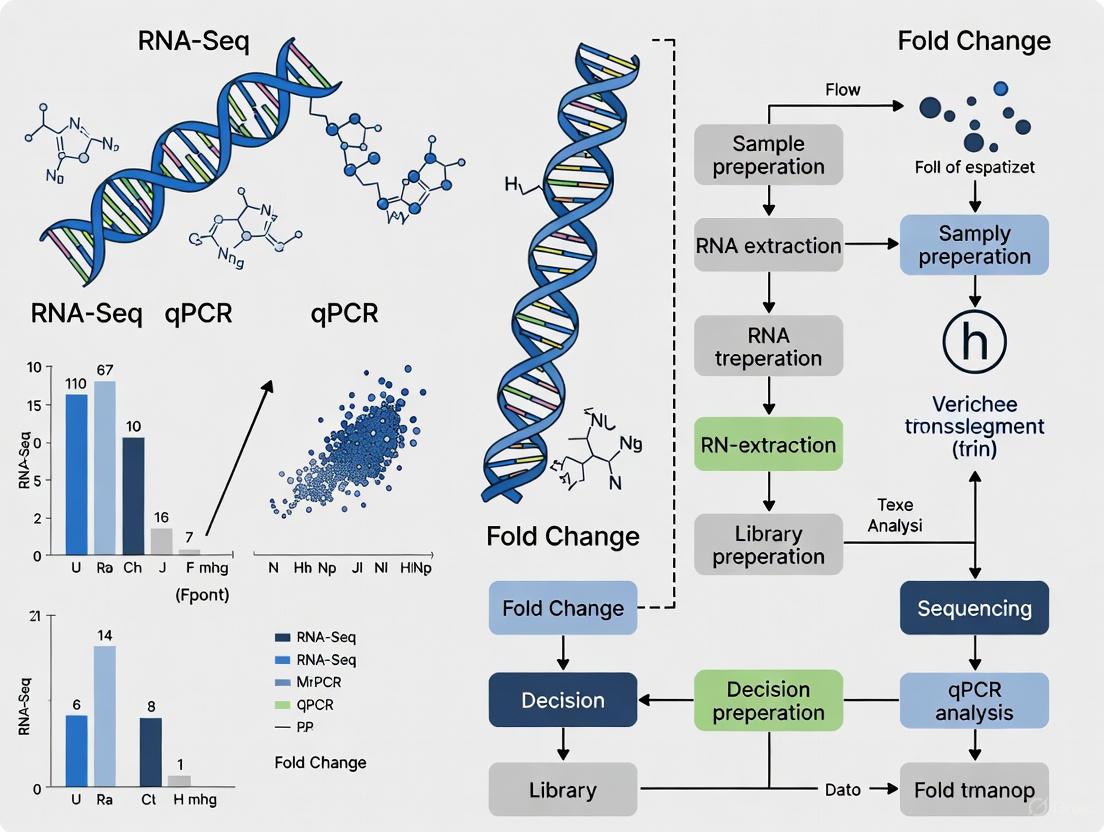

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in a typical RNA-Seq analysis workflow, from raw data to interpretation:

Direct Technical Comparison

The table below provides a systematic, side-by-side comparison of the fundamental technical characteristics of qPCR and RNA-Seq.

Table 1: Fundamental technical characteristics of qPCR and RNA-Seq

| Feature | qPCR (RT-qPCR) | RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Targeted, low to medium (typically < 100 genes) [1] | Genome-wide, high-throughput (all expressed genes) [2] [1] |

| Principle of Quantification | Fluorescence detection during PCR amplification (Cq value) | Counting of sequencing reads mapped to genomic features [2] |

| Dynamic Range | ~7-8 logs of dynamic range | >5 logs of dynamic range, can be influenced by sequencing depth [1] |

| Sensitivity | High, can detect low-abundance transcripts (down to a few copies) | Good, but detection of very low-abundance transcripts requires sufficient sequencing depth [6] |

| Normalization | Relies on stable reference genes for relative quantification | Requires statistical normalization (e.g., TMM, median-of-ratios) for sequencing depth and composition [7] [5] |

| Discoverability | None; requires prior sequence knowledge for primer/probe design | Can identify novel transcripts, isoforms, gene fusions, and SNPs [1] |

| Key Technical Biases | Primer/probe efficiency, RNA quality, reference gene stability | GC content, gene length, mapping biases, PCR amplification duplicates [3] [4] |

Performance and Correlation Data

Empirical studies have directly compared expression measurements from qPCR and RNA-Seq to evaluate their correlation, a critical consideration when validating findings or integrating data from these platforms.

Correlation in Expression Levels and Fold Changes

A benchmark study using the well-characterized MAQC samples compared RNA-Seq workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 13,000 genes. It reported high expression correlations, with Pearson correlation coefficients (R²) ranging from 0.798 to 0.845 for different RNA-Seq analysis workflows (e.g., Tophat-HTSeq, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) [7]. When comparing the more biologically relevant metric of fold-change between samples (MAQCA vs. MAQCB), the correlations were even stronger, with R² values between 0.927 and 0.934 [7]. This indicates that while absolute expression estimates may vary, RNA-Seq is highly reliable for quantifying relative expression differences.

However, correlation can be lower for specific gene families. A 2023 study focusing on the challenging HLA class I genes found only a moderate correlation between qPCR and RNA-seq expression estimates for HLA-A, -B, and -C, with Spearman's rho (ρ) ranging from 0.2 to 0.53 [3]. This highlights how technical factors like extreme polymorphism can impact RNA-Seq quantification accuracy.

Concordance in Differential Expression Calls

Beyond correlation coefficients, the agreement in identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) is a key performance metric. The MAQC benchmark study found that approximately 85% of genes showed consistent differential expression status (either significant or not significant in both methods) between RNA-Seq and qPCR [7]. The remaining ~15% of genes where the methods disagreed (non-concordant genes) were typically lower expressed, had fewer exons, and were smaller in size, suggesting these factors may contribute to technical discordance [7].

Table 2: Summary of key correlation studies between qPCR and RNA-Seq

| Study Focus | Reported Correlation (Expression) | Reported Correlation (Fold-Change) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Transcriptome Benchmarking [7] | R²: 0.798 - 0.845 (Pearson) | R²: 0.927 - 0.934 (Pearson) | ~85% concordance in DE calls. Discrepancies often involve low-expressed, smaller genes. |

| HLA Gene Expression [3] | ρ: 0.2 - 0.53 (Spearman) | Not Specified | Moderate correlation attributed to technical challenges in aligning reads to highly polymorphic HLA genes. |

| Online Community Example [8] | R²: 0.95 (for 8 genes) | Some FC differences noted | While overall correlation can be high for a small gene set, qPCR fold changes may not be as high as in RNA-Seq. |

Experimental Protocols and Technical Considerations

Detailed qPCR Validation Protocol

A robust qPCR validation of RNA-Seq data involves several critical steps [7] [8]:

- Gene Selection: Select target genes based on RNA-Seq results, including both significantly differentially expressed genes and control genes.

- Primer Design: Design and validate primers with high amplification efficiency (90–110%) and specificity, confirmed by a single peak in the melt curve. Amplicon length should be kept short (80–150 bp) for optimal efficiency.

- RNA and cDNA: Use the same RNA samples that were subjected to RNA-Seq. Perform reverse transcription under controlled conditions.

- qPCR Run: Run reactions in technical replicates (e.g., triplicates) [8]. Include no-template controls (NTCs). Use a reliable fluorescence chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan).

- Data Analysis: Calculate Cq values. Use stable reference genes for normalization (e.g., GeNorm or NormFinder algorithms). Calculate relative fold changes using the 2^(-ΔΔCq) method.

- Correlation Analysis: Compare log2(fold-change) values from qPCR and RNA-Seq for the selected genes.

Key RNA-Seq Analysis Workflows for Expression Quantification

For RNA-Seq, the choice of bioinformatics workflow can influence the expression estimates and their correlation with qPCR [7]:

- Alignment-Based workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq): Reads are first aligned to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner like STAR. Tools like HTSeq-count or featureCounts are then used to count the number of reads overlapping each gene.

- Pseudoalignment workflows (e.g., Kallisto, Salmon): These tools avoid base-by-base alignment. Instead, they rapidly assign reads to transcripts by comparing k-mers against a reference transcriptome, directly providing transcript abundance estimates. These methods are generally faster and require less memory.

The MAQC study found that all tested workflows showed high correlation with qPCR data, with pseudoaligners like Salmon and Kallisto performing on par with alignment-based methods [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key solutions and materials required for conducting qPCR and RNA-Seq experiments, based on protocols cited in the search results.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for qPCR and RNA-Seq

| Item | Function/Application | Example Kits/Chemicals |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from cells or tissues. Essential for both techniques. | RNeasy kits (Qiagen) [3] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates. First step in both workflows. | Components of library prep kits (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II) [4] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescence dye for amplification and detection. | SYBR Green or TaqMan master mixes |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Prepares cDNA fragments for sequencing by adding adapters and performing amplification. | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, NuGEN Ovation v2, TaKaRa SMARTer [9] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes added to RNA fragments to accurately identify and count PCR duplicates. | Incorporated in some library prep kits (e.g., NEBNext) [4] |

| RNA Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA sequences added to samples to assess technical performance and normalization. | ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) ExFold RNA Spike-In mixes [9] |

qPCR and RNA-Seq are powerful but technically distinct methods for gene expression quantification. qPCR remains the gold standard for sensitive, precise, and targeted validation of a limited number of genes. In contrast, RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide discovery platform that can reveal the full complexity of the transcriptome. Empirical data shows that fold-change measurements from well-executed RNA-Seq experiments correlate very highly with qPCR data for most protein-coding genes, though challenges remain for specific genomic regions like HLA. The choice between them—or the decision to use them in concert—should be guided by the research question, required throughput, budgetary constraints, and available bioinformatics expertise. For the most rigorous validation, qPCR of key targets following RNA-Seq discovery is a recommended strategy, provided that best practices for both technologies are meticulously followed.

In RNA-Seq and qPCR fold change correlation research, accurately interpreting correlation coefficients is paramount. A "strong" correlation in one biological context may be only "moderate" in another, and understanding the nuances behind these numbers is essential for validating findings and selecting appropriate analytical methods.

Quantitative Interpretation of Correlation Coefficients

There is no universal standard for interpreting correlation coefficients; acceptable values depend heavily on the research context and field-specific conventions [10]. The table below synthesizes interpretation guidelines from three different scientific disciplines, illustrating how the same coefficient can be labeled differently.

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | Psychology (Dancey & Reidy) [10] | Political Science (Quinnipiac University) [10] | Medicine (Chan YH) [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ±0.9 | Strong | Very Strong | Very Strong |

| ±0.8 | Strong | Very Strong | Very Strong |

| ±0.7 | Strong | Very Strong | Moderate |

| ±0.6 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| ±0.5 | Moderate | Strong | Fair |

| ±0.4 | Moderate | Strong | Fair |

| ±0.3 | Weak | Moderate | Fair |

| ±0.2 | Weak | Weak | Poor |

| ±0.1 | Weak | Negligible | Poor |

This comparison underscores the importance of explicitly reporting the strength and direction of a correlation coefficient in manuscripts, rather than relying solely on qualitative terms [10].

Types of Correlation Coefficients and Their Applications

Choosing the correct correlation coefficient is a critical step in analysis, as each type is designed for specific data structures and relationships.

Figure 1: A workflow for selecting the appropriate correlation coefficient based on data characteristics and research goals.

Pearson's r: The Standard for Linear Relationships

Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables [11] [12]. Its values range from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlation), with 0 indicating no linear relationship [13].

- Assumptions: For reliable inference, data should be approximately normally distributed, with no significant outliers, and the relationship should be linear [12].

- Invariance: A key property is its invariance to location and scale changes. Transforming your data (e.g., (X^* = aX + b)) does not change the value of Pearson's r [14].

Spearman's Rho and Kendall's Tau: For Non-Linear and Ranked Data

When data are ordinal, or when the relationship between continuous variables is monotonic but not linear, non-parametric rank correlation coefficients are appropriate [14] [12].

- Spearman's Rho: This coefficient is essentially Pearson's r calculated on the rank orders of the data. It assesses how well the relationship between two variables can be described by a monotonic function [13] [14].

- Kendall's Tau: Unlike Spearman's rho, which assesses the difference in rank, Kendall's tau is based on the number of concordant and discordant pairs between two variables [10] [14]. It is often preferred for smaller sample sizes and is less sensitive to errors [10] [12].

Concordance Correlation: Measuring Agreement

While Pearson's r measures correlation, the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) measures agreement—how well pairs of observations conform to a 45-degree line (the line of perfect agreement) [10] [14]. In RNA-Seq benchmarking, this is crucial for comparing a new method's measurements to a gold standard.

- Interpretation: Values of Lin's CCC can be interpreted similarly to Pearson's r, with values below 0.90 often considered "Poor," and above 0.99 "Almost Perfect" [10].

Experimental Protocols for Correlation Analysis in RNA-Seq

Robust correlation analysis in RNA-Seq requires meticulous experimental design and execution. The following protocols are derived from large-scale, multi-center benchmarking studies.

Reference Material and Study Design

A multi-center study involving 45 laboratories established a robust protocol for assessing RNA-Seq performance, particularly in detecting subtle differential expression critical for clinical applications [15].

- Sample Panel: The study used a panel of well-characterized RNA reference materials. This included four Quartet RNA samples from a family cohort (with small biological differences), MAQC RNA samples with large biological differences, and artificially mixed samples (T1 and T2) with known mixing ratios [15].

- Spike-in Controls: External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) synthetic RNAs were spiked into specific samples to provide a built-in truth for absolute expression accuracy [15].

- Replication: Each sample was processed with three technical replicates, resulting in 1,080 RNA-seq libraries for a comprehensive dataset [15].

Data Generation and Analysis Workflow

Participating laboratories used their in-house experimental protocols and bioinformatics pipelines, reflecting real-world variability. The subsequent analysis focused on identifying sources of technical variation [15].

Figure 2: An overview of the multi-center RNA-Seq benchmarking study design, highlighting the major sources of variation investigated.

- Performance Metrics: The study used a comprehensive framework to assess performance [15]:

- Data Quality: Measured using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR).

- Expression Accuracy: Assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between RNA-Seq data and "ground truth" datasets from TaqMan assays and reference datasets.

- Differential Expression Accuracy: Evaluated the correct identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) against reference DEG lists.

- Variation Analysis: The influence of 26 different experimental factors and 140 bioinformatics pipelines was systematically evaluated to determine best practices [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in the featured RNA-Seq benchmarking study, which are fundamental for conducting similar correlation analyses.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Correlation Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet RNA Reference Materials | RNA derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family [15]. | Provides samples with small, known biological differences, enabling assessment of "subtle differential expression" detection, which is highly relevant for clinical diagnostics [15]. |

| MAQC RNA Reference Materials | RNA from a pool of ten cancer cell lines (MAQC A) and human brain tissue (MAQC B) [15]. | Provides samples with large biological differences, traditionally used for RNA-Seq quality control and benchmarking [15]. |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | 92 synthetic RNA transcripts with known concentrations spiked into samples [15]. | Serves as a built-in "ground truth" for evaluating the accuracy of absolute gene expression measurements from RNA-Seq data [15]. |

| TaqMan Assay Datasets | A gold-standard gene expression quantification method using qPCR [15]. | Provides an independent, high-confidence reference dataset for validating the accuracy of gene expression levels measured by RNA-Seq. Correlation with TaqMan data is a key performance metric [15]. |

Navigating the Nuances: Context is King

A statistically significant correlation does not automatically imply a strong relationship. A correlation of 0.31 can have a highly significant p-value (p < 0.0001) yet still be considered a weak association [10]. Therefore, researchers must report and interpret the actual value of the correlation coefficient, not just its statistical significance.

Furthermore, correlation does not imply causation [11] [10]. An observed association, no matter how strong, can be driven by a third, unmeasured variable. Establishing causality typically requires controlled experimentation beyond correlational analysis [11].

Finally, while quantitative measures are essential, visualizing data with scatterplots is a critical step that should never be omitted. Scatterplots can reveal outliers, non-linear relationships, or heteroscedasticity that a single correlation coefficient might miss [11] [16]. For a comprehensive analysis, graphs and statistical measures should be used in tandem [11].

In the field of genomics research, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has long been considered the gold standard for gene expression validation due to its high sensitivity and specificity. However, with the advent of high-throughput technologies, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for transcriptome-wide expression analysis. A critical area of investigation focuses on the correlation of fold-change measurements—the key metric in differential expression analysis—between these two platforms. Understanding the factors that influence this correlation is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who integrate data from multiple platforms in their experimental workflows. This guide objectively compares the performance of these technologies and examines how expression level, gene length, and transcript complexity affect the concordance of their measurements, supported by experimental data from controlled studies.

Experimental Protocols for Concordance Studies

To ensure the validity of comparisons between RNA-seq and qPCR, researchers follow standardized experimental protocols. The methodologies below are derived from established benchmarking studies that systematically evaluate platform performance.

Benchmarking Study Design

- Sample Selection: Well-characterized RNA reference samples are used to provide a consistent benchmark. The MAQC (MicroArray Quality Control) project's Universal Human Reference RNA (MAQCA) and Human Brain Reference RNA (MAQCB) are frequently employed as they represent distinct transcriptomic profiles [17].

- Platform Processing: The same RNA samples are processed in parallel using multiple platforms. For RNA-seq, this involves library preparation followed by sequencing on an appropriate platform. For qPCR, it requires reverse transcription followed by amplification using target-specific assays [17] [18].

- Data Processing and Normalization: RNA-seq reads are processed through multiple bioinformatic workflows (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) to generate expression estimates. qPCR data undergoes normalization using stable reference genes identified through statistical approaches such as Coefficient of Variation analysis and NormFinder [17] [19].

Concordance Assessment Methodology

- Expression Correlation: Researchers calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson or Spearman) between normalized qPCR quantification cycle (Cq) values and log-transformed RNA-seq expression values (e.g., TPM - Transcripts Per Million) across all measured genes [17].

- Fold Change Correlation: The correlation of gene expression fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples is calculated for both platforms. This is often considered the most relevant comparison for differential expression studies [17].

- Discrepancy Analysis: Genes with inconsistent measurements between platforms are identified through metrics such as expression rank differences and fold change deviations. These genes are then analyzed for common characteristics including expression level, gene length, and exon count [17].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for an experimental comparison between qPCR and RNA-seq:

Quantitative Comparison of Platform Concordance

The tables below summarize key findings from major comparative studies, providing quantitative evidence of how different factors influence measurement concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR.

| Metric | Range Across Studies | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Correlation (R²) | 0.798 - 0.845 | Pearson correlation between normalized qPCR Cq-values and log-transformed RNA-seq values [17] |

| Fold Change Correlation (R²) | 0.927 - 0.934 | Pearson correlation of expression fold changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples [17] |

| Non-concordant Genes | 15.1% - 19.4% | Percentage of genes with inconsistent differential expression calls between platforms [17] |

| High ΔFC Genes | 7.1% - 8.0% | Percentage of non-concordant genes with fold change differences >2 between platforms [17] |

Table 2: Impact of Gene Characteristics on Concordance

| Gene Characteristic | Impact on Concordance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Low Expression Level | Lower concordance | 83-85% of rank outlier genes had significantly lower expression levels [17] |

| Smaller Gene Size | Lower concordance | Inconsistent genes were typically smaller with fewer exons [17] |

| Fewer Exons | Lower concordance | Genes with fewer exons showed higher rates of discordance [17] |

| Transcript Complexity | Lower concordance at isoform level | Isoform expression correlations (median R=0.55-0.68) were lower than gene-level correlations (median R=0.68-0.82) [18] |

Key Factors Influencing Concordance

Expression Level

Experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that expression level significantly impacts measurement concordance. Genes with lower expression levels show substantially higher rates of discordance between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements. In benchmarking studies, approximately 83-85% of "rank outlier" genes—those with large differences in expression ranking between platforms—exhibited significantly lower expression levels in qPCR measurements [17]. This pattern can be attributed to the different detection sensitivities of each platform and their varying susceptibility to technical noise at low expression ranges.

Gene Length and Exon Count

Gene structural characteristics, particularly length and exon count, systematically influence concordance. Studies analyzing inconsistent genes between RNA-seq and qPCR found these genes were "typically smaller, had fewer exons" compared to genes with consistent measurements [17]. The fundamental difference in measurement principles between the technologies contributes to this effect—qPCR typically targets specific regions of a transcript, while RNA-seq must reconstruct full transcript information from fragments, making shorter genes with fewer exons more challenging for accurate quantification in sequencing-based approaches.

Transcript Complexity

The complexity of transcript architecture represents a major challenge in cross-platform concordance. While gene-level expression correlations between RNA-seq and qPCR are generally high (median Spearman correlation R=0.68-0.82), agreement drops significantly at the isoform level (median Spearman correlation R=0.55-0.68) [18]. This discrepancy arises because isoform quantification requires resolving reads from shared exon regions among alternative transcripts, introducing additional computational challenges and potential for ambiguity. The more recently developed NanoString platform also demonstrates lower consistency with both RNA-seq and Exon-array for isoform quantification, confirming this as a fundamental challenge across multiple technologies [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

This table details key platforms and reagents used in gene expression analysis, along with their primary functions and considerations for use.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Analysis

| Platform/Reagent | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq | Transcriptome-wide expression profiling | Detects known and novel features; sensitive to transcript length bias [18] |

| qPCR | Targeted gene expression validation | High sensitivity and specificity; requires stable reference genes [19] |

| NanoString nCounter | Targeted expression without reverse transcription | Digital counting of transcripts; avoids enzymatic amplification biases [18] |

| Reference RNAs (MAQCA/MAQCB) | Benchmarking and standardization | Well-characterized transcriptomes for platform comparison [17] |

| Stable Reference Genes | qPCR normalization | Identified through statistical approaches (CV analysis, NormFinder); essential for reliable quantification [19] |

RNA-seq Analysis Workflows and Their Performance

Different RNA-seq quantification methods show varying levels of consistency with qPCR measurements, particularly for isoform expression estimation. The following diagram illustrates the relationships between major RNA-seq analysis approaches and their performance characteristics:

When comparing RNA-seq workflows, studies have found that alignment-based methods like STAR-HTSeq and Tophat-HTSeq generally show slightly higher consistency with qPCR fold changes compared to pseudoalignment methods such as Kallisto and Salmon [17]. For isoform-level quantification specifically, Net-RSTQ and eXpress demonstrate better agreement with orthogonal validation methods compared to other quantification tools [18].

The correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR fold change measurements is systematically influenced by specific gene characteristics. Lower expression levels, smaller gene size, fewer exons, and higher transcript complexity all contribute to reduced concordance between these platforms. These factors should be carefully considered when designing experiments that integrate data from multiple technologies or when selecting genes for cross-platform validation. Researchers should be particularly cautious when interpreting results for low-expressed genes or when working at the isoform level rather than the gene level, as these contexts show higher rates of discordance. Understanding these key factors enables more informed experimental design and data interpretation, ultimately strengthening the reliability of gene expression studies in basic research and drug development.

The transition from microarray technology to next-generation sequencing has revolutionized transcriptome analysis, with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) emerging as the dominant method for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification. However, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) has remained the gold standard for gene expression validation due to its well-established precision and reliability. The relationship between these two technologies—specifically the correlation of fold-change measurements derived from each method—has therefore become a critical focus of genomic research. Large-scale consortium-led studies have been instrumental in providing comprehensive, unbiased assessments of this relationship, offering insights that individual laboratory studies cannot achieve due to limitations in scale, scope, and resources.

The Sequencing Quality Control (SEQC) project, also known as MAQC-III, represents one of the most ambitious efforts to date to characterize the performance of RNA-seq technologies, building upon the foundation established by the earlier MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) projects. These consortium efforts have generated massive datasets comprising hundreds of billions of reads from well-characterized reference samples, enabling systematic evaluation of RNA-seq accuracy, reproducibility, and information content across multiple platforms and laboratory sites. This review synthesizes evidence from these and other large-scale comparison studies to assess the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR fold-change measurements, examining the technical variables that affect concordance and providing guidance for optimal experimental design and data analysis in genomic research.

The SEQC/MAQC Consortium Projects: Design and Scope

Project Architecture and Experimental Design

The SEQC/MAQC consortium projects were coordinated by the US Food and Drug Administration to address growing concerns about the reproducibility and reliability of genomic measurements across different platforms and laboratories. The SEQC project, as a continuation of the MAQC initiative, specifically focused on assessing RNA-seq performance using reference RNA samples with built-in controls [20]. The experimental design employed well-characterized reference RNA samples: Sample A (Universal Human Reference RNA) and Sample B (Human Brain Reference RNA), with additional samples C and D created by mixing A and B in known ratios of 3:1 and 1:3, respectively [21]. This controlled design enabled researchers to assess both absolute and relative quantification accuracy, as the expected fold changes between samples were predetermined.

The scale of the SEQC project was unprecedented in transcriptomics research. The consortium generated over 100 billion reads (10 terabytes) of data from multiple sequencing platforms, including Illumina HiSeq, Life Technologies SOLiD, and Roche 454 GS FLX, across multiple laboratory sites [20] [22]. This massive dataset provided a unique resource for evaluating RNA-seq analyses for both research and regulatory applications, allowing for systematic assessment of cross-platform and cross-site reproducibility using standardized reference materials.

Key Methodological Approaches

A critical aspect of the SEQC/MAQC projects was the implementation of standardized protocols and reference materials to enable valid comparisons across technologies. The consortium utilized the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) spike-in controls, which consist of synthetic transcripts at known concentrations, to evaluate technical performance [20]. These controls allowed researchers to assess accuracy by comparing measured values to expected values across the dynamic range of expression.

The analytical approaches employed in these studies encompassed multiple bioinformatic pipelines for read alignment and quantification. Commonly evaluated workflows included alignment-based methods such as Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, and STAR-HTSeq, as well as alignment-free methods such as Kallisto and Salmon [7]. For differential expression analysis, popular tools like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma were compared [21] [23]. This comprehensive approach to methodology enabled researchers to assess not only the performance of sequencing technologies themselves but also the impact of computational choices on downstream results.

Correlation Between RNA-seq and qPCR Fold Changes

Multiple large-scale studies have demonstrated generally high correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR fold change measurements, though with important limitations. In a comprehensive benchmarking study that compared five RNA-seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes, high fold change correlations were observed across all methods, with Pearson correlation coefficients (R²) ranging from 0.927 to 0.934 depending on the workflow [7]. This indicates that approximately 85-90% of the variance in RNA-seq fold changes can be explained by qPCR measurements, suggesting generally strong concordance between the technologies for differential expression analysis.

The alignment-based algorithms (Tophat-HTSeq and STAR-HTSeq) showed slightly better performance compared to pseudoalignment methods (Salmon and Kallisto) in terms of the fraction of non-concordant genes, with alignment methods having approximately 15% non-concordance versus 19% for pseudoaligners [7]. Despite these differences in specific metrics, the overall conclusion across studies is that RNA-seq and qPCR show substantial agreement in relative expression measurements when properly conducted.

Analysis of Discordant Findings

While overall correlation is high, a significant fraction of genes show discordant fold change measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR. The benchmarking study by Everaert et al. revealed that approximately 15-20% of genes showed non-concordant results when comparing RNA-seq and qPCR fold changes [24]. However, the majority of these discordances (93%) involved fold changes lower than 2, and approximately 80% showed fold changes lower than 1.5 [24]. This pattern suggests that most discrepancies occur when expression differences are subtle, which represents a challenging scenario for any quantification technology.

Only a small fraction (approximately 1.8%) of genes showed severe non-concordance with fold changes greater than 2 [24]. These severely discordant genes were typically characterized by lower expression levels and shorter transcript length, highlighting the technical challenges in quantifying such transcripts regardless of the method used. These findings emphasize that while RNA-seq and qPCR generally agree for strongly differentially expressed genes, caution is warranted when interpreting subtle expression changes, particularly for low-abundance transcripts.

Table 1: Correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR Fold Change Measurements Across Studies

| Study | Number of Genes | Overall Correlation (R²) | Concordance Rate | Key Factors Affecting Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everaert et al. [7] | 18,080 | 0.927-0.934 | 80.6-84.9% | Expression level, transcript length |

| SEQC/MAQC-III [20] | 55,674 | N/R | >80% (with filters) | GC content, platform-specific biases |

| Aguiar et al. [3] | HLA genes | 0.2-0.53 (rho) | Moderate | Extreme polymorphism, paralog similarity |

Factors Influencing RNA-seq and qPCR Correlation

Technical and Analytical Variables

Several technical factors significantly impact the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements. The SEQC project identified that measurement performance depends substantially on both the sequencing platform and the data analysis pipeline used, with particularly large variation observed for transcript-level profiling compared to gene-level analysis [20]. The consortium also found that RNA-seq and microarrays do not provide accurate absolute measurements, and gene-specific biases are observed for all examined platforms, including qPCR itself [20] [22]. This highlights that no technology is free from methodological artifacts, and each approach has its own limitations and biases.

The MAQC/SEQC consortium emphasized that reproducibility across platforms and sites is acceptable only when specific filters are used [20]. These filters typically exclude genes with low expression levels or extreme base composition, which are particularly prone to technical artifacts. Factor analysis approaches, such as surrogate variable analysis (SVA), have been shown to substantially improve the empirical false discovery rate by identifying and correcting for hidden confounders in the data [21]. After such corrections, the reproducibility of differential expression calls between RNA-seq and established methods typically exceeds 80% for genome-scale surveys [21].

Biological and Genomic Context Considerations

The genomic context of specific genes also significantly influences the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR measurements. A recent study focusing on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes found only moderate correlation between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq for HLA-A, -B, and -C genes (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) [3]. This relatively poor correlation was attributed to the extreme polymorphism at HLA genes and the high similarity between paralogs, which complicates both qPCR assay design and RNA-seq read alignment [3]. These challenges are particularly pronounced for RNA-seq, as the alignment of short reads to a reference genome that does not completely represent HLA allelic diversity can lead to mapping errors and quantification biases.

Similar issues likely affect other multigene families with high sequence similarity, suggesting that correlation between technologies may be gene-specific rather than uniform across the transcriptome. This has important implications for studies focusing on such challenging gene families, as additional validation may be necessary despite generally good genome-wide concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR.

Table 2: Factors Affecting RNA-seq and qPCR Correlation and Recommended Mitigation Strategies

| Factor | Impact on Correlation | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Low expression levels | Higher discordance, especially for fold changes <2 | Apply expression filters (e.g., TPM > 0.1) |

| Short transcript length | Reduced correlation for shorter transcripts | Consider transcript length in interpretation |

| High GC content | Platform-specific biases | GC content adjustment in normalization |

| Sequence polymorphism | Reduced correlation for highly polymorphic genes | Use personalized reference genomes |

| Paralogous genes | Cross-mapping and quantification errors | Improve read assignment with specialized tools |

| Library preparation | Introduces technical variability | Standardize protocols across samples |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

The large-scale comparisons conducted by the SEQC/MAQC consortium and other groups have helped establish best practices for RNA-seq analysis when comparing with qPCR data. A typical workflow begins with quality control of raw sequencing reads using tools such as FastQC, followed by read alignment to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or TopHat2 [21]. For quantification, both alignment-based methods (e.g., HTSeq-count, featureCounts) and alignment-free methods (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto) have been shown to provide accurate results, with the latter generally offering improved speed and resource efficiency [7] [25].

A critical step in ensuring accurate comparison with qPCR data is the appropriate normalization of count data. The median-of-ratios method used in DESeq2, trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) used in edgeR, and transcripts per million (TPM) are commonly employed approaches, each with specific strengths and limitations [23] [26]. For differential expression analysis, methods that incorporate shrinkage estimation for dispersions and fold changes, such as DESeq2 and edgeR, have demonstrated improved stability and interpretability of estimates, particularly for studies with small sample sizes [23].

Figure 1: Standardized RNA-seq analysis workflow for comparison with qPCR data, highlighting essential steps (red), optional quality enhancement steps (green), and input/output elements (yellow and blue).

qPCR Validation Methodology

For qPCR experiments designed to validate RNA-seq results, the MAQC consortium established rigorous protocols that have been widely adopted. These include the use of multiple reference genes for normalization, efficiency correction for amplification, and adherence to MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines to ensure experimental quality and reproducibility [24]. The whole-transcriptome qPCR dataset used in benchmarking studies typically employs assays that detect specific subsets of transcripts that contribute proportionally to the gene-level quantification cycle (Cq) value [7].

To enable valid comparisons between RNA-seq and qPCR data, careful alignment of transcripts detected by qPCR with those quantified in RNA-seq analysis is essential. For transcript-level RNA-seq workflows (e.g., Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon), gene-level TPM values are calculated by aggregating transcript-level TPM values of those transcripts detected by the respective qPCR assays [7]. For gene-level RNA-seq workflows (e.g., HTSeq), gene-level counts are converted to TPM values to enable comparison across technologies and experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq and qPCR Comparisons

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in Consortium Studies |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA transcripts at known concentrations | Assessment of technical performance and accuracy [25] |

| MAQC Reference RNA Samples | Well-characterized human reference RNA | Inter-platform and inter-site comparisons [20] |

| Universal Human Reference RNA | Pool of 10 cell lines (Sample A) | Evaluation of expression profiling accuracy [7] |

| Human Brain Reference RNA | Brain-specific reference (Sample B) | Assessment of tissue-specific expression [7] |

| RNA Spike-in Mixes | Known ratio mixtures (Samples C & D) | Fold change accuracy assessment [21] |

| qPCR Assay Panels | Whole-transcriptome expression profiling | Benchmark standard for RNA-seq validation [7] |

Implications for Research and Regulatory Applications

Best Practices for Experimental Design

The evidence from large-scale consortium studies supports several key recommendations for researchers designing experiments involving RNA-seq and qPCR. First, for genome-scale surveys where the goal is to identify differentially expressed genes across the transcriptome, the added value of validating RNA-seq results with qPCR is likely to be low, provided that all experimental steps and data analyses are carried out according to state-of-the-art protocols [24]. The high concordance rates observed in benchmarking studies (approximately 85% for differentially expressed genes) suggest that RNA-seq alone can provide reliable results for such exploratory studies.

However, situations where entire biological conclusions are based on differential expression of only a few genes, particularly if these genes have low expression levels or show small fold changes, warrant orthogonal validation by qPCR [24]. In such cases, qPCR provides an independent verification that observed differences are real and not attributable to technical artifacts specific to RNA-seq methodology. Additionally, qPCR remains valuable for measuring expression of selected genes in additional samples beyond those included in the RNA-seq experiment, extending the validation to different conditions or genetic backgrounds.

Considerations for Regulatory Settings

The SEQC project specifically addressed the requirements for clinical and regulatory applications of RNA-seq data, highlighting the importance of reproducibility and accuracy standards in these contexts. The consortium found that with artifacts removed by factor analysis and additional filters, the reproducibility of differential expression calls typically exceeds 80% for all tool combinations examined, which directly reflects the robustness of results across different studies [21]. This level of reproducibility may be acceptable for many regulatory purposes, provided that appropriate quality control measures are implemented.

For clinical applications where individual gene expression measurements may inform diagnostic or treatment decisions, the SEQC project recommended careful consideration of platform-specific biases and implementation of gene-specific bias corrections [20]. The consortium also emphasized that RNA-seq does not provide accurate absolute measurements, suggesting that relative expression changes between conditions rather than absolute expression levels should form the basis for clinical interpretations [22]. These insights have important implications for the developing standards in precision medicine and molecular diagnostics.

Large-scale consortium studies, particularly the SEQC/MAQC projects, have provided comprehensive evidence regarding the correlation between RNA-seq and qPCR fold change measurements. The overall conclusion from these efforts is that RNA-seq and qPCR show strong concordance for differential gene expression analysis, with approximately 85% of genes showing consistent results between the technologies. This high level of agreement, coupled with the broader dynamic range and additional information provided by RNA-seq (e.g., alternative splicing, novel transcripts), supports the position of RNA-seq as the current gold standard for transcriptome-wide expression profiling.

Nevertheless, important limitations remain. Correlation between the technologies is influenced by multiple factors, including expression level, transcript length, genomic context, and the specific bioinformatic pipelines employed. For genes with low expression levels or high sequence similarity to other genomic regions, and for subtle expression changes (fold change < 2), discordances between RNA-seq and qPCR are more common. In these cases, and when critical biological conclusions rely on specific gene expression changes, orthogonal validation by qPCR remains warranted. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and analytical methods improve, the correlation between RNA-seq and established methods like qPCR will likely strengthen further, eventually potentially eliminating the need for systematic validation in most research contexts.

Best Practices for Pipeline Design: From Sequencing Reads to qPCR Validation

Within the context of a broader thesis on RNA-Seq qPCR fold change correlation research, this guide objectively compares the performance of various RNA-Seq analysis pipelines. A primary focus is assessing how choices in read mapping, expression quantification, and data normalization impact the accuracy of log2 fold change (log2FC) estimation, a critical metric for downstream biological interpretation [27]. The reliability of this estimation directly influences the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the validation of findings through qPCR, a common confirmatory step in transcriptomics studies.

Robust differential expression (DE) analysis is foundational to applications across biomedicine and drug development, from biomarker discovery to understanding disease mechanisms [28]. However, the complexity of RNA-Seq data analysis, involving multiple steps with numerous available tools, introduces potential for variability [29]. This comparison leverages recent benchmarking studies to evaluate pipelines based on empirical data, providing a resource for researchers to make informed, evidence-based decisions in their experimental workflows.

RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow: Core Steps and Key Alternatives

The transformation of raw sequencing reads into biologically meaningful insights involves a sequential pipeline where choices at each stage can influence final outcomes [5]. The core steps are preprocessing, alignment, quantification, normalization, and differential expression analysis.

Figure 1. RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow and Common Tool Alternatives. The diagram outlines the key stages of a bulk RNA-Seq analysis pipeline, from raw data to differential expression results, along with commonly used software and methods at each step [5] [30].

Core Workflow Breakdown

- Preprocessing: The initial step involves quality control (QC) and trimming of raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files). Tools like FastQC and MultiQC generate QC reports, while Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, and fastp remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [5] [31]. This step is critical for increasing mapping rates and the reliability of downstream analysis [29].

- Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome. Common aligners include STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 [5]. Performance varies, with studies noting that HISAT2 is fast with low memory requirements, while STAR is highly accurate [5] [30].

- Quantification: This step counts the number of reads mapped to each genomic feature (gene or transcript). It can be done via traditional alignment-based counting with tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count [5]. Alternatively, pseudoalignment tools like Salmon and Kallisto perform quantification directly from raw reads, offering speed advantages [5] [30].

- Normalization: Technical artifacts like differing sequencing depths and library compositions are adjusted. Common methods include Counts per Million (CPM), Transcripts per Million (TPM), and the methods integrated into DE tools like the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) from

edgeRand the Relative Log Expression (RLE) fromDESeq2[5] [30]. - Differential Expression Analysis: This final step identifies statistically significant differences in expression between conditions. Widely used tools include DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom [32] [27] [30]. The choice of tool can significantly impact the number and accuracy of identified DEGs [27].

Performance Comparison of Tools and Pipelines

Impact of Tool Selection on Fold Change Estimation

The choice of software at each stage can cumulatively affect the precision and accuracy of the final gene expression measurements. A comprehensive study evaluating 192 distinct analysis pipelines revealed substantial differences in their performance for gene expression quantification [29]. The accuracy and precision of these pipelines were validated using qRT-PCR measurements for a set of 32 genes, establishing a benchmark for comparison.

Table 1. Performance of Top-Ranked RNA-Seq Pipelines for Gene Expression Quantification. This table summarizes the top-performing pipelines from a benchmark of 192 alternatives, ranked by their accuracy and precision against qRT-PCR validation data [29].

| Overall Rank | Trimming Tool | Alignment Tool | Quantification Method | Normalization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BBDuk | STAR | featureCounts | TPM |

| 2 | BBDuk | STAR | featureCounts | UQ |

| 3 | Cutadapt | STAR | featureCounts | TPM |

| 4 | Cutadapt | STAR | featureCounts | UQ |

| 5 | BBDuk | HISAT2 | featureCounts | TPM |

The alignment and quantification steps were identified as particularly influential. Pipelines utilizing STAR for alignment and featureCounts for quantification consistently achieved high accuracy in raw gene expression signal quantification [29]. For normalization, TPM and Upper Quartile (UQ) normalization were among the top performers in this specific benchmark. The consistency of these top methods provides a data-driven starting point for pipeline selection.

Comparative Performance of Differential Expression Tools

The final and most critical step for most studies is the identification of differentially expressed genes. Different DE tools employ distinct statistical models and normalization approaches, which can lead to varying results, especially for genes with low expression or high variability [27] [33].

Table 2. Comparison of Differential Expression Analysis Tools. This table compares the performance of popular DE tools based on benchmarking studies using simulated and spike-in datasets [32] [27].

| DE Tool | Statistical Basis | Recommended Context | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model with shrinkage estimation | Standard experiments; often a top performer in benchmarks | Showed highest F-measure in spike-in studies; can be sensitive to high variability [27]. |

| edgeR | Negative binomial model | Standard experiments; offers robust options for complex designs | Comparable performance to DESeq2; reliable with TMM normalization [32]. |

| limma-voom | Linear modeling with precision weights | Studies with small sample sizes or low effect sizes | Good control of false discovery rate (FDR); estimates lower logFC values versus others [27] [33]. |

| dearseq | Non-parametric, variance-focused testing | Small sample sizes; complex experimental designs | Identified as robust in benchmarks with limited replicates [32]. |

A key finding from benchmark analyses is that no single tool uniformly outperforms all others in every scenario [27]. Performance is influenced by factors such as the number of biological replicates, the strength of the expression fold change, and the inherent variability of the data. For instance, while DESeq2 performed well in a spike-in experiment, limma-voom demonstrated superior FDR control in other settings, particularly for lowly expressed genes like long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [33]. Notably, different tools can estimate substantially different log2FC values for the same gene, highlighting the importance of method selection and potential consensus approaches [27].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of pipeline comparisons, benchmarking studies employ rigorous experimental and computational protocols.

Data Simulation and Validation

A common approach involves using simulated data where the "true" differential expression status is known. One protocol generates synthetic RNA-seq datasets based on real experimental data (e.g., from rare disease studies or model organisms like A. thaliana) [27]. Parameters such as the number of genes, replicates, fraction of DEGs, and log2FC effect sizes are systematically varied. Performance is then evaluated by measuring how well each pipeline recovers the simulated truth, using metrics like precision, recall, and F-measure.

Subsampling Analysis for Replicability

To assess the impact of cohort size on result stability, a resampling protocol is used. This involves taking large RNA-seq datasets (e.g., from TCGA or GEO with 40+ replicates per condition) and repeatedly drawing random subsamples of smaller sizes (e.g., 3, 5, or 10 replicates) [34]. For each subsample, DEG analysis is performed. The overlap of results across these iterations (replicability) and with the full dataset (precision/recall) is measured. This procedure helps estimate the expected performance and reliability of studies constrained by small sample sizes.

qRT-PCR Validation Protocol

Wet-lab validation remains a gold standard. In one comprehensive study, RNA from the same samples used for RNA-seq was reverse-transcribed to cDNA [29]. Taqman qRT-PCR assays were then performed in duplicate on 32 selected genes. To ensure accurate normalization for qPCR data, the global median normalization method was employed, using the median Ct value of all genes with Ct < 35 in a sample as the normalization factor. The resulting expression values served as a benchmark to evaluate the accuracy of the RNA-seq pipelines.

Table 3. Key Research Reagents and Resources for RNA-Seq Benchmarking. This table lists essential materials and datasets used in the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Control RNAs | External RNA controls with known concentrations used to assess technical accuracy and quantify expression. | Sequins (V1, V2), ERCC, SIRVs (E0, E2) are mixed with sample RNA prior to library prep to evaluate pipeline performance [35]. |

| Reference Gene Sets | A set of genes with stable expression used for validation and normalization. | 107 housekeeping genes (HKg) constitutively expressed across 32 healthy tissues and cell lines were used to benchmark pipeline precision [29]. |

| Public Data Repositories | Sources of large, well-annotated RNA-seq datasets for subsampling analysis and method development. | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) provide data from thousands of samples for robust benchmarking [34]. |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Gold-standard method for independent validation of gene expression levels from RNA-seq. | Taqman qRT-PCR mRNA assays were used to validate 32 genes, with global median normalization of Ct values [29]. |

The choice of tools in an RNA-Seq analysis pipeline, from alignment and quantification to normalization and differential expression, has a measurable impact on the accuracy of fold change estimation. Benchmarking studies consistently show that pipelines utilizing aligners like STAR, quantifiers like featureCounts or Salmon, and differential expression tools like DESeq2 or limma-voom demonstrate robust performance, though the optimal choice can depend on specific data characteristics [29] [27] [30].

A critical, overarching finding is the profound influence of biological replication on result reliability. Studies with fewer than five replicates per condition are highly prone to generating irreproducible results, regardless of the pipeline used [34]. For research and drug development professionals, the path to reliable conclusions involves two key strategies: first, prioritizing adequate sample sizes whenever possible, and second, adopting a consensus or classifier-based approach that integrates results from multiple DE tools to enhance robustness and confidence in the identified biomarkers and differentially expressed genes [27].

Selecting Optimal Reference Genes for qPCR Using RNA-Seq Data with Tools like GSV

The transition from large-scale RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) discovery to targeted validation via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) remains a cornerstone of gene expression analysis in molecular biology and drug development. This process is critical for confirming transcriptomic findings, such as those investigating RNA-seq qPCR fold change correlation, yet its accuracy hinges entirely on a often-overlooked factor: the selection of optimal reference genes. Reference genes, or housekeeping genes, serve as internal controls to normalize RT-qPCR data, correcting for variations in RNA quality, cDNA synthesis efficiency, and pipetting inaccuracies [36] [37]. The use of an unstable reference gene can lead to erroneous normalization, fundamentally compromising the validity of gene expression data and subsequent scientific conclusions [38] [39].

Traditionally, reference genes were selected from constitutively expressed cellular maintenance genes. However, numerous studies have demonstrated that the expression of classic housekeeping genes like GAPDH, ACTB (β-actin), and 18S rRNA can vary significantly across different tissue types, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [38] [40] [39]. This variability has driven the development of systematic, data-driven approaches for identifying stable reference genes, with RNA-seq data emerging as a powerful resource for this selection process. By leveraging the comprehensive expression profiles provided by RNA-seq, researchers can now make informed decisions about the most stable reference genes for their specific experimental systems, thereby enhancing the reliability of RT-qPCR validation [41] [42].

Computational Tools for Reference Gene Selection

The challenge of reference gene selection has spurred the development of specialized computational tools. These algorithms analyze expression stability from RNA-seq data to recommend optimal reference genes, moving beyond traditional assumptions to data-driven selections.

Table 1: Comparison of Tools for Reference Gene Selection

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Data | Key Features | Platform/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) [41] [43] [42] | Selection of reference and variable genes from RNA-seq | TPM values from bulk RNA-seq (via .csv, .xlsx, or Salmon .sf files) | Filters genes based on expression level (TPM) and stability (SD, CV); suggests both stable reference and variable validation genes | Windows 10 executable (.exe) |

| EndoGeneAnalyzer [44] | Analysis of RT-qPCR data to validate reference genes | Cq values from RT-qPCR experiments | Web-based; integrates NormFinder; allows outlier removal and differential expression analysis | Open-source web tool |

| geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper [38] [40] | Stability analysis of candidate reference genes from RT-qPCR data | Cq values from RT-qPCR | Model-based and pairwise comparison approaches; typically used in tandem for cross-validation | Various standalone algorithms |

Among these, the Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) represents a specialized approach designed specifically to bridge RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. GSV employs a filtering-based methodology that uses Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values across RNA-seq samples to identify genes with high expression and minimal variation as candidate reference genes, while also flagging highly variable genes for validation studies [41] [43]. Its logic filters out lowly expressed genes (TPM > 0), selects for stable expression (SD of Log₂TPM < 1), and ensures consistent high expression (average Log₂TPM > 5) for reference candidates [42]. This direct processing of RNA-seq data makes GSV particularly valuable for designing validation experiments at the project's inception.

Experimental Protocol: From RNA-Seq Data to Reference Gene Validation

Selecting candidate genes via computational tools is only the first step. A rigorous experimental protocol is required to validate their stability in the specific RT-qPCR context. The following workflow outlines this comprehensive process.

Step 1: Candidate Gene Selection Using GSV

Begin by exporting TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values from your RNA-seq analysis pipeline. This can be a single table containing genes and their TPM values across all libraries for .csv or .xlsx input, or a set of direct output files from quantification tools like Salmon (.sf format) [43]. Load the data into the GSV software and apply its default filters, which are designed to remove unstable or lowly expressed genes. The software will generate two key outputs: a list of stable, highly expressed genes ideal as reference candidates, and a list of highly variable genes that can serve as positive controls for validation experiments [41] [42].

Step 2: RT-qPCR Assay Design and Validation

Select 3-5 of the top candidate genes from GSV for experimental validation. Design primers with the following criteria: amplicon size of 90-180 bp, primer length of 20-21 bp, and GC content of 45-60% [40]. It is critical to verify primer specificity by ensuring a single peak in the melting curve and a single band of expected size on an agarose gel [38]. Determine PCR efficiency for each primer set using a standard curve of serial cDNA dilutions. The acceptable range is typically 90-110%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.995 [38] [36].

Step 3: Expression Stability Analysis

Amplify your candidate reference genes across all experimental samples (including different tissues, treatments, or developmental stages) via RT-qPCR. Analyze the resulting quantification cycle (Cq) values using at least two algorithm-based software packages such as geNorm and NormFinder [38] [39]. These programs use different statistical approaches to rank genes by expression stability. geNorm calculates a stability measure (M) through pairwise comparisons, while NormFinder uses a model-based approach to estimate intra- and inter-group variation [38] [44]. The final reference gene(s) should be those consistently ranked as most stable across these different algorithms.

Case Studies and Supporting Experimental Data

Case Study: Application in Aedes aegypti Research

A study on Aedes aegypti mosquitoes exemplifies the practical application of GSV. Researchers used the tool to analyze a transcriptome dataset and identified eiF1A and eiF3j as the most stable reference genes. Subsequent RT-qPCR validation confirmed that these GSV-selected genes outperformed traditionally used reference genes for the samples analyzed. This finding was particularly significant as it highlighted the potential fallibility of conventional choices and demonstrated GSV's ability to identify more reliable, context-specific internal controls [41] [42].

Cross-Species Gene Stability in Anopheles Mosquitoes

Research on six species within the Anopheles Hyrcanus Group further underscores that reference gene stability is not guaranteed across species boundaries, even for closely related organisms. This study evaluated eight candidate genes across five developmental stages and found that optimal reference genes differed by species and life stage. For example, RPL8 and RPL13a were most stable at the larval stage, while RPS17 was stable across adult stages in several species [40]. These results emphasize the necessity of empirical validation, even when studying phylogenetically similar species, and demonstrate the type of cross-species comparative data that GSV-like analysis could generate from RNA-seq data.

Table 2: Expression Stability of Candidate Reference Genes in Different Organisms

| Organism/Context | Most Stable Reference Genes | Traditional but Unstable Genes | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aedes aegypti (GSV-identified) [41] [42] | eiF1A, eiF3j | Traditionally used mosquito reference genes | RT-qPCR validation |

| Anopheles Hyrcanus Group [40] | RPL8, RPL13a (larvae);RPS17 (adults) | Varies by species and developmental stage | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder |

| Peach (Prunus persica) [38] | TEF2, UBQ10, RP II | 18S rRNA, RPL13, PLA2, GAPDH, ACT | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper |

| Cultured Ocular Surface Epithelia [39] | YWHAZ, EIF4A2, UBC | Varies by cell type and culture duration | geNorm, NormFinder |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from samples | Prioritize kits with DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [40]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA | Use a consistent enzyme and priming method (e.g., oligo-dT and/or random hexamers) across all samples [36]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent detection of amplified DNA during qPCR | Contains passive reference dye for signal normalization; opt for mixes with robust hot-start polymerases [38] [36]. |

| GSV Software [43] | Computational selection of candidate genes from RNA-seq TPM data | Windows-compatible executable; accepts output from Salmon or tabular TPM data. |

| Stability Analysis Software (geNorm, NormFinder) | Statistical ranking of candidate genes based on Cq value stability | Using multiple algorithms provides cross-validation for more reliable results [38] [44]. |

The selection of optimal reference genes is a critical, non-negotiable step in the RT-qPCR workflow that directly impacts data reliability and experimental conclusions. The integration of RNA-seq data analysis using tools like GSV provides a powerful, data-driven foundation for this selection process, moving the field beyond reliance on potentially unstable traditional housekeeping genes. By following the outlined experimental protocol—which combines computational pre-screening with rigorous wet-lab validation—researchers can significantly enhance the accuracy of their gene expression studies. As the field advances, this systematic approach will be essential for producing reproducible, publication-quality data that faithfully reflects biological reality, particularly in critical applications like drug development and diagnostic biomarker discovery.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold-standard method for validating gene expression findings from high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). However, its apparent simplicity often leads to treatment as a mere "quick confirmation" tool rather than a quantitative measurement system demanding analytical scrutiny equivalent to microarrays or next-generation sequencing [45]. This complacency is particularly problematic in the context of RNA-seq qPCR fold change correlation research, where technical variability in qPCR can easily obscure genuine biological signals. The widespread assumption that qPCR outputs are intrinsically reliable, coupled with inconsistent adherence to best-practice guidelines, has exacerbated issues of reproducibility and contributed to misleading conclusions that undermine correlation studies [45] [46].

The core challenge lies in qPCR's measurement uncertainty, especially at low target concentrations where stochastic amplification, efficiency fluctuations, and technical variability confound quantification [45]. When qPCR is used to confirm RNA-seq results, these technical artifacts can distort perceived correlation strength and lead to overinterpretation of small fold changes. Recent systematic evaluations demonstrate that variability at low input concentrations often exceeds the magnitude of biologically meaningful differences, highlighting the critical need for methodological rigor in experimental design [45]. Within this context, the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide an essential framework for achieving the reproducibility and transparency required for reliable RNA-seq qPCR correlation research.

Core Principles of the MIQE Guidelines

The MIQE guidelines, established in 2009 and recently updated to MIQE 2.0, create a standardized framework for executing and reporting qPCR experiments to ensure reproducibility and credibility [47] [48] [46]. These guidelines cover all experimental aspects—from sample preparation and assay validation to data analysis and reporting—providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with tools to comprehensively document their qPCR workflows.

A fundamental MIQE principle is comprehensive transparency that enables independent verification of results. This includes full disclosure of all reagents, sequences, and analysis methods [48]. For assay design, the guidelines emphasize the importance of providing either a unique identifier (such as the TaqMan Assay ID) or the complete probe and amplicon context sequences to ensure experimental reproducibility [47]. The recent MIQE 2.0 revision extends these principles to address emerging applications and technological advances while reinforcing why methodological rigor is non-negotiable for trustworthy data [46].

Despite widespread awareness of MIQE, compliance remains problematic. Common deficiencies include poorly documented sample handling, unvalidated assays, inappropriate normalization, missing efficiency calculations, and insufficient statistical justification [46]. These failures are not marginal oversights but fundamental methodological problems that compromise data integrity, particularly in diagnostic settings and fold-change correlation studies where distinguishing technical noise from biological signal is paramount.

Experimental Design: MIQE-Compliant qPCR Workflows

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Proper sample preparation begins with rigorous assessment of nucleic acid quality and integrity, as these factors significantly impact quantification accuracy [46]. RNA quality directly affects reverse transcription efficiency and subsequent quantification in RT-qPCR experiments. The MIQE guidelines recommend using automated electrophoresis systems such as Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to generate RNA Integrity Number (RIN) scores, with appropriate thresholds established for specific applications.

For sample input, consistency in DNA quantity across reactions is crucial. Experiments demonstrate that adding variable amounts of sample/matrix DNA can inhibit PCR amplification, though careful primer and probe design can mitigate these effects [49]. Maintaining uniform DNA input (e.g., 1,000 ng per reaction as used in biodistribution studies) across standard curve, quality control, and experimental samples ensures comparable reaction conditions and reduces technical variability [49].

Assay Design and Validation

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Probe-Based vs. Dye-Based qPCR Detection Methods

| Feature | Probe-Based qPCR (e.g., TaqMan) | Dye-Based qPCR (e.g., SYBR Green) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Superior due to sequence-specific binding of primer and probe [49] | Lower; prone to false positives from non-specific amplification [49] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Yes; multiple targets with different fluorophores [49] | No; limited to single target per reaction [49] |

| Development Complexity | Higher initial development but more efficient optimization [49] | Lower initial development but more extensive optimization needed [49] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher reagent cost but lower labor hours [49] | Lower reagent cost but higher optimization labor [49] |

| Required Validation | Melting curve analysis not required | Essential melting curve analysis to confirm specificity [49] |

Probe-based qPCR systems, particularly TaqMan assays, offer significant advantages for MIQE-compliant research due to their superior specificity and multiplexing capabilities [49]. These assays utilize forward and reverse primers with a sequence-specific fluorescent probe, typically with a 5' reporter dye and a 3' quencher. During the exponential amplification phase, the probe is cleaved, separating the reporter from the quencher and generating fluorescence proportional to accumulated PCR product.

A critical validation step involves efficiency determination through standard curves with serial dilutions of known template concentrations. The slope of the plot of Ct values versus the logarithm of template concentration determines PCR efficiency (E), calculated as E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [49]. Optimal efficiency falls between 90%-110% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1), with 100% efficiency (slope of -3.32) indicating perfect doubling of product each cycle [49]. This efficiency calculation is essential for accurate quantification but is frequently overlooked or assumed in non-compliant studies [46].

Technical Replicates and Statistical Considerations