RNA-seq Normalization Methods: A Practical Guide for Exploratory Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq normalization, a critical step for ensuring the biological validity of exploratory transcriptomic analysis.

RNA-seq Normalization Methods: A Practical Guide for Exploratory Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq normalization, a critical step for ensuring the biological validity of exploratory transcriptomic analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we demystify the core principles, practical applications, and common pitfalls of normalization methods. Starting with foundational concepts, we progress through a detailed comparison of within-sample and between-sample techniques like TPM, FPKM, TMM, and RLE, highlighting their suitability for different analytical goals. The guide further covers troubleshooting for complex datasets, including those with global expression shifts or copy number variations, and outlines best practices for validation. By integrating methodological insights with benchmarks from recent studies, this resource empowers scientists to confidently select and apply normalization strategies that enhance the reliability and interpretability of their exploratory RNA-seq findings in disease research and therapeutic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Why RNA-seq Normalization is Essential for Exploratory Analysis

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the journey from raw data to biological insight is fraught with technical challenges. Technical variability introduced during library preparation, sequencing, and data processing can obscure true biological signals, leading to inaccurate conclusions in exploratory research and drug development [1] [2]. Normalization serves as a critical statistical correction process that adjusts raw count data to account for these non-biological artifacts, enabling meaningful comparison of gene expression levels within and between samples [1]. Without appropriate normalization, even well-designed studies may generate false positives or miss genuine differential expression, compromising research validity and therapeutic discovery efforts.

The fundamental sources of technical variability in RNA-seq data include:

- Sequencing depth: Variation in the total number of sequenced reads across samples [1]

- Gene length bias: Longer transcripts generating more reads independent of actual expression levels [1]

- GC-content effects: Sequence-specific biases where guanine-cytosine content influences read count efficiency [2]

- Batch effects: Systematic technical variations introduced when samples are processed at different times, locations, or by different personnel [1]

- Library composition differences: Varying expression profiles between samples affecting relative abundance measurements [1]

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for addressing these challenges through appropriate normalization strategies, with specific protocols and analytical tools tailored for research scientists in pharmaceutical and academic settings.

Understanding Normalization Stages

RNA-seq normalization methods can be categorized into three distinct stages, each addressing different aspects of technical variability. The appropriate application of these stages depends on the specific biological questions being addressed and the nature of the sample comparisons required.

Within-Sample Normalization

Within-sample normalization enables meaningful comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample. This stage addresses two primary technical variables: transcript length and sequencing depth [1]. Longer genes naturally produce more sequencing fragments than shorter genes at identical expression levels, creating a length bias that must be corrected for accurate intra-sample gene comparison [1]. Common methods for within-sample normalization include:

Table 1: Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Description | Formula | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts Per Million) | Normalizes for sequencing depth only | CPM = (Reads mapped to gene / Total mapped reads) × 10^6 |

Preliminary data screening; requires additional between-sample normalization for comparisons [1] | Does not account for gene length differences [1] |

| FPKM/RPKM (Fragments/Reads Per Kilobase per Million) | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length | FPKM = (Reads mapped to gene / (Gene length in kb × Total mapped reads in millions)) |

Single-end (RPKM) or paired-end (FPKM) data; within-sample gene expression comparison [1] | Values depend on total transcript population; problematic for between-sample comparisons [1] |

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) | Normalizes for sequencing depth and gene length with different calculation order | TPM = (Reads mapped to gene / Gene length in kb) / (Sum of length-normalized counts) × 10^6 |

Within-sample comparisons; preferred over FPKM/RPKM as sum of TPMs is consistent across samples [1] | Still requires between-sample normalization for cross-sample comparisons [1] |

Between-Sample Normalization

Between-sample normalization addresses technical variations when comparing the same gene across different samples. This stage is essential for differential expression analysis and assumes that most genes are not differentially expressed between samples [1]. These methods calculate sample-specific scaling factors to remove distributional differences while preserving biological signals.

Table 2: Between-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Description | Algorithm | Advantages | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Uses a reference sample and calculates scaling factors based on fold changes after trimming extreme values [1] | 1. Select reference sample; 2. Calculate log fold changes (M-values) and absolute expression levels (A-values); 3. Trim extreme values; 4. Compute weighted mean of M-values; 5. Calculate scaling factors [1] | Robust to differentially expressed genes; performs well with compositionally different samples [1] | Available in edgeR package [3] |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) | Calculates median ratio of each gene to a pseudo-reference sample | 1. Create pseudo-reference sample from geometric means of all genes; 2. Calculate ratio of each gene to pseudo-reference; 3. Compute median ratio for each sample; 4. Use as scaling factor [3] | Effective for large datasets; stable performance across various conditions [3] | Available in DESeq2 package [3] |

| Quantile | Forces the distribution of gene expression to be identical across samples | 1. Rank genes by expression in each sample; 2. Calculate average expression for each rank across samples; 3. Replace original values with rank averages; 4. Restore original gene order [1] | Removes global distribution differences; standardizes expression profiles [1] | Available in various packages including limma |

Cross-Dataset Normalization

Cross-dataset normalization becomes necessary when integrating RNA-seq data from multiple independent studies, sequencing batches, or experimental platforms. Batch effects often represent the greatest source of variation in combined datasets and can completely obscure true biological differences if left uncorrected [1]. These methods adjust for both known (e.g., sequencing date, facility) and unknown technical variables.

Table 3: Cross-Dataset Normalization Methods

| Method | Description | Approach | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes batch effect correction | Uses parametric empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects while preserving biological signals; works well with small sample sizes by "borrowing" information across genes [1] | Requires pre-specified batch variables; assumes batch effects are systematic and additive |

| Limma | Linear models with empirical Bayes moderation | Fits linear models to expression data and applies empirical Bayes moderation to variance estimates; includes functions for removing batch effects [1] | Flexible framework for complex experimental designs; can incorporate multiple batch variables |

| SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis) | Correction for unknown sources of variation | Identifies and estimates surrogate variables that represent unmodeled technical variation; particularly useful when batch information is incomplete or unknown [1] | Does not require pre-specification of batch variables; may capture biological variation if not carefully implemented |

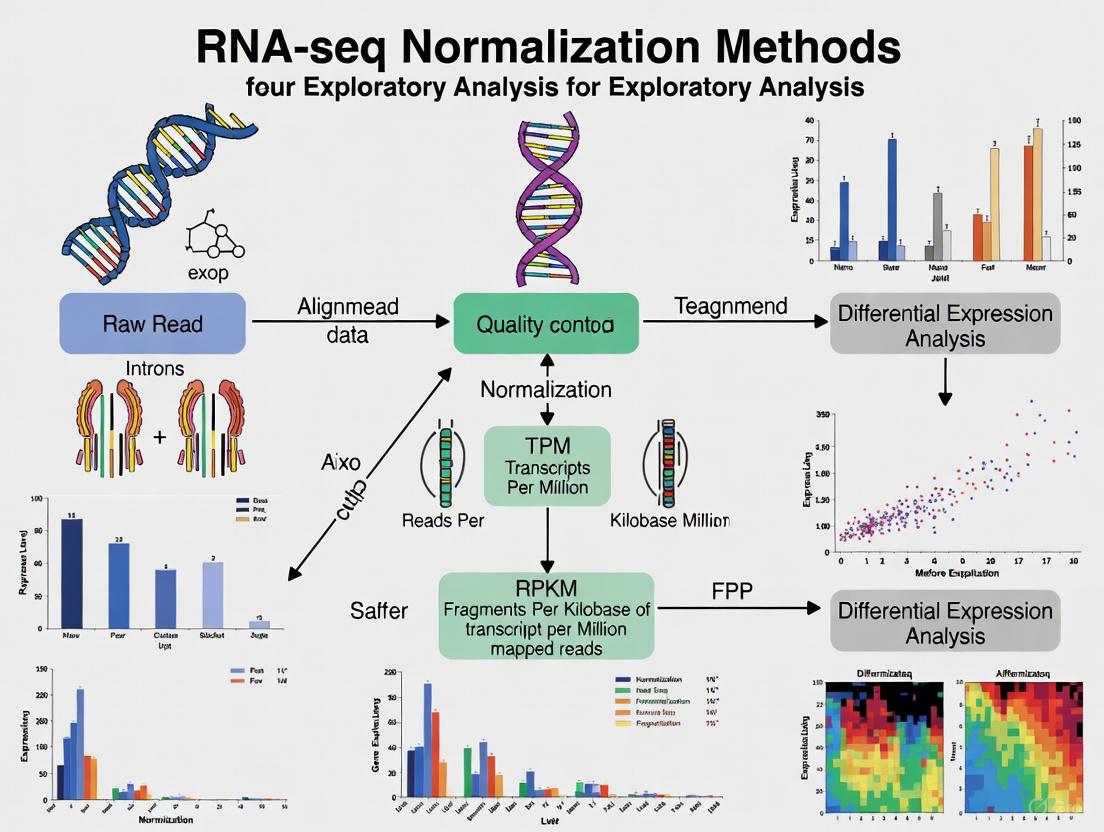

Figure 1: RNA-seq Normalization Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential approach to addressing technical variability through three normalization stages.

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Methods

Performance Benchmarking in Metabolic Modeling

Recent benchmarking studies provide empirical evidence for normalization method performance in specific applications. A 2024 study published in npj Systems Biology and Applications evaluated five normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, and RLE) for transcriptome mapping on human genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) using iMAT and INIT algorithms [3].

The research demonstrated that between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) enabled production of condition-specific metabolic models with significantly lower variability in the number of active reactions compared to within-sample methods (FPKM, TPM) [3]. Specifically:

- Models generated with TPM and FPKM normalized data showed high sample-to-sample variability in reaction counts

- RLE, TMM, and GeTMM approaches produced more consistent model sizes with lower variability

- Between-sample methods demonstrated superior accuracy in capturing disease-associated genes (~0.80 for Alzheimer's disease and ~0.67 for lung adenocarcinoma)

- All methods showed improved accuracy when covariate adjustment was applied for age, gender, and post-mortem interval [3]

Table 4: Benchmark Results of Normalization Methods in Metabolic Modeling

| Normalization Method | Model Variability | AD Gene Accuracy | LUAD Gene Accuracy | Reaction Detection | Covariate Adjustment Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM | High | Moderate | Moderate | High false positives | Significant improvement |

| FPKM | High | Moderate | Moderate | High false positives | Significant improvement |

| TMM | Low | High (~0.80) | Moderate (~0.67) | Balanced | Moderate improvement |

| RLE | Low | High (~0.80) | Moderate (~0.67) | Balanced | Moderate improvement |

| GeTMM | Low | High (~0.80) | Moderate (~0.67) | Balanced | Moderate improvement |

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate normalization method depends on experimental design, sample characteristics, and analytical goals:

- For single-sample analyses (e.g., pathway enrichment within one condition): TPM provides appropriate within-sample comparability [1]

- For differential expression across conditions: TMM or RLE offer robust performance, particularly with compositionally different samples [1] [3]

- For multi-study integrations: Sequential application of within-sample, between-sample, and cross-dataset normalization is recommended [1]

- For metabolic modeling applications: RLE, TMM, or GeTMM are preferred to minimize false positive predictions [3]

- When covariates are influential: Apply covariate adjustment after normalization to remove age, gender, or technical effects [3]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive RNA-seq Normalization Workflow

Objective: Implement a complete normalization pipeline for differential expression analysis from raw count data.

Materials:

- RNA-seq count matrix (genes × samples)

- Sample metadata (experimental conditions, batches, covariates)

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- Required R packages: edgeR, DESeq2, limma, sva

Figure 2: Experimental Normalization Protocol. This workflow guides method selection based on experimental design and data characteristics.

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Load count matrix and metadata into R

- Filter low-expressed genes (recommended: require >1 count per million in at least X samples, where X is the size of the smallest group)

- Examine sample relationships with PCA to identify potential batch effects and outliers

Within-Sample Normalization (TPM)

Between-Sample Normalization (TMM)

Batch Effect Correction (ComBat)

Covariate Adjustment

Validation Steps:

- Post-normalization PCA should show clustering by biological condition rather than technical batches

- Distribution of expression values should be similar across samples after normalization

- Positive control genes with known expression patterns should maintain expected behavior

Protocol 2: Conditional Quantile Normalization for GC Content Bias

Objective: Address sequence-specific biases, particularly GC-content effects, that impact counting efficiency [2].

Background: GC-content has been shown to strongly influence gene expression measurements in RNA-seq data, creating sample-specific effects that can generate false positives if uncorrected [2]. This protocol combines robust generalized regression to remove GC-content bias with quantile normalization to correct global distortions.

Materials:

- RNA-seq count matrix

- Gene-level GC content values (can be calculated from reference sequences)

- R packages: preprocessCore, dplyr

Procedure:

Calculate GC Content for Each Gene

Perform Conditional Quantile Normalization

Validate GC Bias Reduction

- Plot expression values against GC content before and after correction

- Correlation between GC content and expression should be minimized after correction

- Check preservation of biological signals using positive control genes

Performance Notes: This approach has been shown to improve measurement precision by 42% without loss of accuracy in benchmark studies [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-seq Normalization

| Category | Item/Resource | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Packages | edgeR (R package) | Implementation of TMM normalization and related differential expression methods [1] [3] | Between-sample normalization; differential expression analysis |

| DESeq2 (R package) | Implementation of RLE normalization and negative binomial-based differential expression [3] | Between-sample normalization; large dataset analysis | |

| limma (R package) | Linear modeling framework with empirical Bayes moderation; batch correction tools [1] | Cross-dataset normalization; complex experimental designs | |

| sva (R package) | Surrogate variable analysis for unknown batch effects; ComBat for known batches [1] | Batch effect correction; multi-study integrations | |

| Reference Materials | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Synthetic exogenous RNA controls with known concentrations | Normalization quality assessment; technical variability monitoring |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Reference genome sequences and annotations | Gene length information; GC content calculation | |

| Quality Assessment Tools | FastQC | Quality control metrics for raw sequencing data | Pre-normalization data quality evaluation |

| MultiQC | Aggregate results from multiple bioinformatics tools across all samples | Comprehensive quality assessment pre- and post-normalization | |

| Data Resources | GENCODE | Comprehensive human and mouse gene annotations | Accurate gene model definitions for length normalization |

| Sequence Read Archive (SRA) | Public repository of raw sequencing data | Access to data for method validation and comparison |

Effective correction of technical variability through appropriate normalization remains a cornerstone of robust RNA-seq analysis in exploratory research and drug development. The hierarchical approach addressing within-sample, between-sample, and cross-dataset variability provides a systematic framework for generating reliable transcriptional profiles. Method selection should be guided by experimental design, with between-sample methods (TMM, RLE) generally preferred for differential expression analysis and cross-sample comparisons. As demonstrated in recent benchmarking studies, these methods reduce variability in downstream applications while maintaining sensitivity to true biological signals. Implementation of the protocols outlined herein will enhance data quality, improve reproducibility, and strengthen biological conclusions derived from RNA-seq experiments in pharmaceutical and basic research settings.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for transcriptome profiling, but the raw data generated contains technical biases that must be corrected through normalization to reveal true biological signals. These technical variations originate from multiple sources, including sequencing depth (number of reads per sample), gene length (longer genes accumulate more reads), and sample-to-sample variability introduced during library preparation and sequencing runs. Effective normalization is therefore essential for accurate biological interpretation [1].

The normalization process occurs across three distinct hierarchical stages: within-sample (enabling gene expression comparison within a single sample), between-sample (enabling comparison across multiple samples within a dataset), and across datasets (enabling integration of data from different studies or batches). Each stage addresses specific technical challenges and employs different mathematical approaches to ensure data reliability [1]. This protocol outlines comprehensive methodologies for each normalization stage, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these techniques in exploratory transcriptome analysis.

The Three Stages of Normalization

Within-Sample Normalization

Purpose and Applications: Within-sample normalization methods adjust for technical variations that affect gene expression measurements within individual samples. The primary goals are to correct for gene length bias (longer genes naturally have more mapped reads) and sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample) to enable meaningful comparisons of expression levels between different genes within the same sample [1]. These normalized values are particularly valuable for assessing the relative abundance of various transcripts within a single biological specimen.

Commonly Used Methods:

- FPKM/RPKM: Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) for paired-end data and reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (RPKM) for single-end data correct for both library size and gene length. These units are appropriate for comparing gene expression within a single sample but have limitations for between-sample comparisons because the expression of a gene in one sample can appear different from its expression in another sample even at identical true expression levels [1].

- TPM: Transcripts per million (TPM) is considered an improvement over FPKM/RPKM. It represents the relative number of transcripts you would detect for a gene if you had sequenced one million full-length transcripts. The calculation involves dividing the number of reads mapped to a transcript by the transcript length, then dividing this value by the sum of mapped reads to all transcripts after normalization for transcript length, and multiplying by one million. A key advantage is that the sum of all TPMs in each sample is the same, reducing variation between samples [1].

Table 1: Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Correction Factors | Primary Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Counts Per Million | Sequencing depth | Preliminary normalization | Does not correct for gene length; requires additional between-sample normalization [1] |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Gene length & sequencing depth | Within-sample comparisons | Paired-end data; sample-specific relative abundance affects comparisons [1] |

| RPKM | Reads Per Kilobase Million | Gene length & sequencing depth | Within-sample comparisons | Single-end data; similar limitations to FPKM [1] |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Gene length & sequencing depth | Within-sample comparisons | Sum of TPMs consistent across samples; preferred over FPKM/RPKM [1] |

Within a Dataset (Between-Sample) Normalization

Purpose and Applications: Between-sample normalization addresses technical variations that occur between different samples within the same dataset. These methods enable valid comparisons of gene expression levels for the same gene across different samples or experimental conditions. Without this crucial step, differences in library size and composition could masquerade as biological effects [1]. These methods typically operate on count matrices after within-sample normalization has been applied.

Commonly Used Methods:

- TMM: The Trimmed Mean of M-values method, implemented in the edgeR package, operates on the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed. TMM calculates scaling factors to adjust library sizes by first selecting a reference sample, then computing fold changes and absolute expression levels of other samples relative to this reference. The method strategically "trims" the data to remove genes with extreme fold changes or high expression, and the trimmed mean of the fold changes is used to scale read counts [1].

- RLE: The Relative Log Expression method, used by DESeq2, similarly assumes that most genes are non-differential. RLE calculates a correction factor as the median of the ratios of all genes in a sample compared to a geometric mean reference sample. This correction factor is then applied to the read counts of individual genes [3].

- GeTMM: Gene length corrected Trimmed Mean of M-values represents a newer approach that combines gene-length correction with between-sample normalization, effectively bridging within-sample and between-sample normalization paradigms [3].

- Quantile: This method aims to make the distribution of gene expression levels identical for each sample in a dataset. It assumes global distribution differences between samples are technical in origin. The method ranks genes by expression level for each sample, calculates average values across all samples for genes of the same rank, and replaces original values with these averages before returning genes to their original order [1].

Performance Considerations: Benchmark studies comparing these normalization methods have demonstrated that between-sample methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) produce condition-specific metabolic models with considerably lower variability compared to within-sample methods (FPKM, TPM) when mapping RNA-seq data to genome-scale metabolic models. Specifically, between-sample methods more accurately capture disease-associated genes, with average accuracy of approximately 0.80 for Alzheimer's disease and 0.67 for lung adenocarcinoma in one comprehensive benchmark [3].

Across Datasets Normalization

Purpose and Applications: Also known as batch correction, across-datasets normalization addresses technical variations introduced when integrating RNA-seq data from multiple independent studies, sequencing centers, or time points. These "batch effects" can become the dominant source of variation in combined datasets, potentially masking true biological differences and leading to incorrect conclusions if not properly addressed [1]. This stage is particularly crucial for meta-analyses that combine publicly available datasets or for large studies conducted across multiple sequencing facilities.

Commonly Used Methods:

- ComBat: Part of the sva package, ComBat employs empirical Bayes methods to adjust for batch effects while preserving biological signals. The method works well even with small sample sizes because it "borrows" information across genes in each batch to create more robust adjustments. ComBat requires that batch variables are known in advance [1].

- Limma: The removeBatchEffect function in the limma package uses a linear modeling framework to eliminate technical batch effects from the expression data. Like ComBat, it requires known batch variables and should be applied after within-dataset normalization to ensure gene expression values are on the same scale between samples [1].

- Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA): For cases where batch effects or other unknown sources of technical variation are present, SVA can identify and estimate these hidden factors. The method does not require prior knowledge of all batch variables and can effectively adjust for both known and unknown technical variations [1].

Table 2: Across-Datasets Normalization Methods

| Method | Implementation | Batch Information Requirement | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | sva R package | Known batches | Empirical Bayes framework; robust for small sample sizes [1] |

| Limma | limma R package | Known batches | Linear modeling framework; includes removeBatchEffect() function [1] |

| SVA | sva R package | Known or unknown batches | Identifies surrogate variables; corrects for hidden factors [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Within-Sample Normalization

Required Materials and Software:

- Raw count matrix from RNA-seq alignment (e.g., from STAR/Salmon pipeline)

- R or Python environment with appropriate packages

- Gene annotation file with transcript lengths

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load the raw count matrix into your analytical environment, ensuring proper formatting with genes as rows and samples as columns.

- Calculate Normalization Factors:

- For TPM: Divide each gene count by its transcript length in kilobases to obtain reads per kilobase (RPK). Sum all RPK values in a sample and divide by 1,000,000 to obtain per-million scaling factor. Divide each RPK value by this scaling factor to generate TPM values [1].

- For FPKM: Similar to TPM but with different order of operations - first normalize for sequencing depth then gene length.

- Validation: Verify that the sum of all TPM values for each sample equals 1,000,000, confirming correct calculation.

- Downstream Application: Use normalized values for within-sample analyses such as identifying highly expressed genes or pathway activity within individual samples.

Protocol 2: Implementing Between-Sample Normalization with TMM

Required Materials and Software:

- Within-sample normalized count matrix

- R statistical environment with edgeR package installed

- Experimental design metadata

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Input: Create a DGEList object in edgeR containing your count data and sample information.

- Calculate Normalization Factors: Apply the

calcNormFactors()function with method="TMM" to compute scaling factors for each sample. - Data Transformation: Convert normalized counts to log2-counts-per-million (logCPM) using the

cpm()function with normalized library sizes. - Quality Assessment: Examine the distribution of samples using PCA plots or multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots to verify reduction of technical variability between replicates.

- Differential Expression: Proceed with differential expression analysis using the normalized counts as input to statistical models.

Protocol 3: Batch Correction Using ComBat

Required Materials and Software:

- Between-sample normalized expression matrix

- R environment with sva package installed

- Batch information metadata (sequencing date, facility, etc.)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Ensure expression data has been previously normalized using between-sample methods. Log2-transform the data if not already transformed.

- Model Specification: Define a model matrix representing the biological groups of interest, and a separate vector indicating batch membership.

- Batch Correction: Execute the

ComBat()function with the expression data, batch vector, and model matrix as inputs. - Validation: Visualize corrected data using PCA plots to confirm reduction of batch-associated clustering while maintaining biological separation.

- Downstream Analysis: Use batch-corrected data for integrated analyses combining multiple datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Normalization

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Bioconductor package implementing TMM normalization | Between-sample normalization for differential expression [3] |

| DESeq2 | Bioconductor package implementing RLE normalization | Between-sample normalization for differential expression [3] |

| sva | Bioconductor package with ComBat and SVA functions | Across-datasets batch effect correction [1] |

| limma | Bioconductor package with removeBatchEffect() function | Across-datasets normalization for linear models [1] |

| FastQC | Quality control tool for raw sequencing data | Initial data quality assessment before normalization [4] |

| Salmon | Alignment-free quantification of transcript abundance | Generation of count matrices for normalization [5] |

| STAR | Spliced-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads | Generation of alignment files for count quantification [5] |

| nf-core/rnaseq | Comprehensive RNA-seq analysis pipeline | Automated workflow including normalization steps [5] |

Workflow Visualization

Three-Stage RNA-seq Normalization Workflow

Covariate Adjustment Considerations

In complex datasets, particularly those from human studies, biological covariates such as age, gender, and post-mortem interval can significantly influence transcriptomic measurements. Recent research demonstrates that adjusting for these covariates during normalization can improve the accuracy of downstream analyses. For example, in studies of Alzheimer's disease and lung adenocarcinoma, covariate adjustment increased the accuracy of capturing disease-associated genes across all normalization methods [3].

The covariate adjustment process typically involves including these variables as covariates in the statistical models used for normalization. For between-sample normalization, this can be implemented through the design matrix in linear models, while for across-datasets normalization, known biological covariates should be included in the model to prevent their removal during batch correction procedures.

The three-stage framework for RNA-seq normalization provides a systematic approach to addressing technical variations at different levels of experimental design. Within-sample normalization enables accurate gene comparison within individual samples, between-sample normalization facilitates valid comparisons across experimental conditions, and across-datasets normalization allows integration of diverse data sources. Benchmark studies indicate that between-sample methods such as RLE, TMM, and GeTMM generally produce more reliable results for differential expression analysis compared to within-sample methods alone [3].

Implementation of this hierarchical normalization approach, with appropriate consideration of biological covariates, ensures that RNA-seq data accurately reflects biological truth rather than technical artifacts. This protocol provides the necessary foundation for researchers to make informed decisions about normalization strategies based on their specific experimental designs and analytical goals.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, raw read counts serve as the fundamental data for transcriptome quantification. However, these counts are influenced by multiple technical biases that can obscure true biological signals if not properly addressed. Sequencing depth refers to the total number of reads sequenced per sample, which directly affects count magnitudes, while library composition describes the transcriptional makeup of each sample, where highly abundant transcripts can skew count distributions for less prevalent species [1] [6]. These biases represent significant challenges for exploratory analysis and differential expression studies, as they introduce systematic variations that are unrelated to biological conditions [7] [8]. Understanding and correcting for these technical artifacts is a prerequisite for obtaining biologically meaningful results from RNA-seq experiments, particularly in drug development contexts where accurate transcript quantification is essential for biomarker identification and therapeutic target validation [9]. This protocol examines the nature of these biases and provides methodological frameworks for their identification and correction within the broader context of RNA-seq normalization for exploratory analysis research.

Understanding Sequencing Depth Bias

Characteristics and Impact

Sequencing depth bias arises from fundamental properties of RNA-seq technology, where the total number of sequenced reads varies substantially between samples. This variation introduces technical noise that must be distinguished from biologically relevant expression differences.

Definition and Mechanism: Sequencing depth refers to the total number of reads obtained per sample, which directly influences raw count magnitudes. Samples with greater sequencing depth naturally yield higher counts for equivalently expressed genes, creating artificial differences that do not reflect true biological variation [1] [9]. This occurs because RNA-seq provides relative, rather than absolute, measures of transcript abundance, where each count represents a proportion of the total sequenced molecules in a library [6].

Impact on Downstream Analysis: Without appropriate correction, sequencing depth variation can severely compromise differential expression analysis. Statistical models in widely used tools like DESeq2 and edgeR rely on raw count distributions that assume library size differences have been accounted for in their internal normalization procedures [10] [11]. When depth biases remain uncorrected, they inflate variance estimates, reduce statistical power for detecting truly differentially expressed genes, and increase false discovery rates [9] [12].

Visual Identification: Exploratory data analysis provides effective methods for detecting sequencing depth biases. Simple diagnostic plots, such as boxplots of log-transformed counts per sample or principal component analysis (PCA) plots colored by total read depth, can reveal systematic patterns correlated with sequencing depth rather than experimental conditions [13] [12]. These visualizations serve as crucial quality control checkpoints before proceeding with formal statistical testing.

Practical Demonstration

The following example illustrates how sequencing depth bias manifests in real datasets and demonstrates appropriate normalization strategies:

Data Inspection: Begin by examining column sums across samples, which reveal substantial differences in total read counts. For example, in the Hammer et al. dataset, column sums range from approximately 4.5 million to 23.5 million reads, indicating nearly a 5-fold difference in sequencing depth between samples [12].

Normalization Implementation: Apply size factor estimation using the median-of-ratios method in DESeq2, which calculates scaling factors centered around 1. These factors represent robust estimates of relative sequencing depth that are less influenced by extremely highly expressed genes than simple total counts [12]. The resulting size factors can vary significantly; in the Hammer dataset, they range from 0.45 to 2.41, confirming substantial depth differences [12].

Visual Validation: Create diagnostic plots comparing raw library sizes to size factors, which should approximately follow a linear relationship. After normalization, PCA plots and sample clustering diagrams should show reduced grouping by sequencing batch and improved clustering by biological conditions, indicating successful mitigation of depth-related artifacts [13] [12].

Table 1: Common Normalization Methods Addressing Sequencing Depth Bias

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counts Per Million (CPM) | Scales counts by total library size multiplied by 1 million | Simple, intuitive calculation | Fails to correct for composition effects; unsuitable for between-sample comparison [1] | Basic arithmetic on count matrix |

| DESeq2 Median-of-Ratios | Uses geometric mean across samples to estimate size factors | Robust to highly expressed genes; integrated into DESeq2 workflow [12] | Assumes most genes not differentially expressed | DESeq2::estimateSizeFactors() |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Trims extreme log fold-changes and library sizes | Robust for between-sample normalization; implemented in edgeR [1] | Sensitive to the proportion of differentially expressed genes | edgeR::calcNormFactors() |

| Transcripts Per Million (TPM) | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length | Suitable for within-sample comparisons [1] | Sums to constant across samples; not recommended for differential expression | Length-normalized counts divided by total length-scaled counts |

Understanding Library Composition Bias

Theoretical Foundation

Library composition bias represents a more subtle challenge than sequencing depth effects, arising from the relative nature of RNA-seq measurements and the finite sampling capacity of sequencing platforms.

Fundamental Principle: RNA-seq measures transcript abundance in relative terms, where each count reflects the proportion of that transcript within the total RNA pool rather than its absolute cellular concentration [6]. This proportional relationship means that changes in the abundance of a few highly expressed genes can create apparent changes in all other genes, even when their absolute expression remains constant [6] [9].

Mathematical Basis: The finite nature of sequencing resources creates a competitive relationship between transcripts. When one transcript population dramatically increases in abundance, it necessarily reduces the sequencing "budget" available for all other transcripts, creating artificial suppression effects for genes that are not truly differentially expressed [6]. This composition effect violates the assumption that total RNA content is constant across samples, which underpins simpler normalization approaches.

Biological Consequences: In treatment experiments where fundamental cellular processes are altered, total RNA output may change substantially between conditions. For example, drug treatments that affect metabolic activity or proliferation rates can globally impact transcription, creating systematic composition differences that complicate direct sample comparisons [6] [9]. These scenarios require specialized normalization approaches that can distinguish technical artifacts from biological effects.

Concrete Example and Implications

A hypothetical scenario illustrates how composition bias distorts expression measurements:

Table 2: Library Composition Bias Example (Read Counts)

| Gene | Group A | Group B | True Expression Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene1 | 500 | 0 | Differentially expressed |

| Gene2 | 500 | 0 | Differentially expressed |

| Gene3 | 500 | 1000 | Not differentially expressed |

| Gene4 | 500 | 1000 | Not differentially expressed |

| Total | 2000 | 2000 |

In this example, both groups have identical total reads (2000), but Genes 1 and 2 are exclusively expressed in Group A, while Genes 3 and 4 show identical expression in both groups. Without composition-aware normalization, all four genes would appear differentially expressed due to the redistribution of sequencing resources, leading to false conclusions [6]. Advanced normalization methods like TMM and median-of-ratios address this by identifying invariant genes across samples and using them to calculate scaling factors that adjust for composition effects [1] [6].

Integrated Experimental Protocol for Bias Identification and Correction

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The initial experimental phases introduce biases that propagate through subsequent analysis stages. Implementing standardized protocols during these steps minimizes technical variability.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Begin with high-quality RNA extraction using silica-gel-based column procedures (e.g., mirVana miRNA isolation kit), which provide superior yield and quality compared to TRIzol-based methods, especially for non-coding RNAs [7]. Assess RNA integrity using appropriate methods (e.g., RIN scores), acknowledging that degraded samples require higher input amounts to compensate for fragment loss. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, employ specialized protocols that minimize cross-linking and chemical modifications during nucleic acid extraction [7].

Library Preparation Considerations: During library construction, select fragmentation methods that minimize sequence-specific biases. Chemical fragmentation (e.g., zinc-based) demonstrates superior randomness compared to enzymatic approaches (e.g., RNase III) [7]. For mRNA enrichment, consider ribosomal RNA depletion rather than poly-A selection to avoid 3'-end capture bias, particularly when working with degraded samples or non-polyadenylated transcripts [7]. Employ adapter ligation strategies that incorporate random nucleotides at ligation junctions to reduce sequence-specific preferences of T4 RNA ligases [7].

Amplification Controls: Implement careful PCR amplification protocols using high-fidelity polymerases (e.g., Kapa HiFi) and minimize cycle numbers to reduce duplication biases and GC-content effects [7]. For extreme GC-rich or AT-rich genomes, incorporate PCR additives like TMAC or betaine, and optimize extension temperatures and denaturation times to ensure uniform amplification across different transcript types [7].

Bioinformatic Processing and Quality Assessment

Following sequencing, computational methods identify and quantify residual biases, enabling appropriate normalization strategy selection.

Read Alignment and Quantification: Process raw FASTQ files through quality control using FastQC or multiQC to identify adapter contamination, unusual base composition, or other technical artifacts [9]. Perform adapter trimming with tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt, avoiding over-trimming that unnecessarily reduces usable read depth [9]. Align reads to reference genomes using splice-aware aligners (STAR, HISAT2) or employ alignment-free quantification methods (Salmon, kallisto) that incorporate sequence-specific bias correction directly in abundance estimation [11] [9].

Bias Detection and Diagnostic Visualization: Generate diagnostic plots to identify systematic biases before normalization. Create density plots of log-counts per sample to detect distributional differences related to sequencing depth [13]. Plot GC content versus gene expression to identify sequence composition biases, where specific GC ranges show consistently elevated or depressed expression across samples [8]. Implement correlation heatmaps of samples to identify batch effects and outliers that may indicate technical artifacts rather than biological variation [13].

Normalization Strategy Selection: Based on diagnostic results, select appropriate normalization methods. For datasets with balanced library composition and minimal global expression shifts, standard depth-based methods (CPM, TPM) may suffice [1]. When composition biases are evident, employ advanced methods (TMM, median-of-ratios) that explicitly account for these effects [1] [6]. For experiments with extreme differential expression or expected global transcriptional changes, consider using spike-in controls or housekeeping gene-based normalization to establish absolute scaling factors [6] [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for addressing both sequencing depth and library composition biases:

Diagram 1: Bias Correction Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential process for identifying and correcting sequencing depth and library composition biases in RNA-seq data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful management of RNA-seq biases requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The following table catalogues essential materials for implementing the protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Bias Mitigation

| Category | Item/Resource | Specific Example | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | Column-based kits | mirVana miRNA isolation kit | High-yield RNA purification with preservation of small RNAs | Superior to TRIzol for non-coding RNA analysis [7] |

| RNA Quality Control | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA kits | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment | Critical for evaluating input RNA quality [7] |

| Library Preparation | rRNA depletion kits | Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus | Removal of ribosomal RNA without 3' bias | Preferred over poly-A selection for degraded samples [7] |

| Fragmentation Reagents | Chemical fragmentation | Zinc-based fragmentation | Random fragmentation minimizing sequence bias | Alternative to enzymatic (RNase III) methods [7] |

| Amplification Enzymes | High-fidelity polymerases | Kapa HiFi Polymerase | Reduced amplification bias in GC-rich regions | Superior to Phusion for problematic genomic regions [7] |

| Computational Tools | Quality control | FastQC, MultiQC | Sequence quality assessment and report generation | Essential first step in processing pipeline [9] |

| Alignment Tools | Splice-aware aligners | STAR, HISAT2 | Accurate mapping across splice junctions | Critical for eukaryotic transcriptomes [10] [9] |

| Quantification Tools | Alignment-free methods | Salmon, kallisto | Rapid quantification with bias correction | Incorporates GC-bias and sequence-specific corrections [11] [9] |

| Normalization Software | Differential expression | DESeq2, edgeR | Statistical normalization accounting for multiple biases | Implements median-of-ratios (DESeq2) or TMM (edgeR) [10] [12] |

Sequencing depth and library composition biases represent fundamental challenges in RNA-seq analysis that systematically distort raw count data if left uncorrected. Through implementation of the standardized protocols and quality control measures outlined in this document, researchers can effectively distinguish technical artifacts from biological signals, substantially improving the reliability of downstream analyses. The integrated approach—combining careful experimental design with appropriate computational normalization strategies—ensures that conclusions regarding differential expression reflect true biological differences rather than methodological artifacts. As RNA-seq applications continue to expand in drug development and clinical research contexts, rigorous bias correction remains an essential prerequisite for generating biologically meaningful and reproducible transcriptomic insights.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a fundamental tool for profiling transcriptomes, enabling researchers to explore gene expression across diverse biological conditions. A critical, yet often undervalued, step in this process is data normalization, which adjusts raw sequencing data to account for technical variations that can mask true biological signals. The choice of normalization method is not one-size-fits-all; it must be strategically aligned with the specific exploratory goals of the research. Incorrect normalization can introduce biases, leading to inaccurate biological interpretations and false discoveries. This Application Note provides a structured framework for selecting appropriate RNA-seq normalization methods based on distinct research objectives, complete with comparative data, experimental protocols, and decision-support tools for researchers and drug development professionals.

Understanding RNA-Seq Normalization Stages and Objectives

Normalization is essential because RNA-seq data contains technical biases from factors like sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample), gene length (longer genes accumulate more reads), and RNA composition (differences in the transcript population between samples) [1]. Failure to correct for these variables can lead to misleading conclusions when comparing gene expression.

RNA-seq normalization methods can be categorized into three main stages, each serving a distinct purpose in the analytical pipeline [1]:

- Within-sample normalization enables the comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample. This is crucial for analyses such as identifying the most highly expressed genes in a single condition. Methods in this category correct for the fact that longer genes will naturally have more mapped reads than shorter genes expressed at the same actual level.

- Between-sample normalization enables the comparison of the expression of the same gene across different samples. This is the foundational step for differential expression analysis, where the goal is to find genes that are expressed at different levels between two or more conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy). These methods correct for differences in sequencing depth and composition across samples.

- Across-datasets normalization, or batch correction, is applied when integrating data from multiple independent studies sequenced at different times or facilities. This process removes technical "batch effects" that can be the largest source of variation, thereby masking true biological differences.

The following workflow outlines the logical decision process for selecting a normalization method based on the specific exploratory goal of your research.

A Comparative Guide to Normalization Methods

Different normalization methods employ distinct algorithms and assumptions, making them suitable for specific analytical scenarios. The table below summarizes the key methods, their formulas, primary applications, and important considerations for researchers.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Formula / Core Principle | Primary Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) [1] | ( \text{TPM}i = \frac{ \frac{\text{Reads}i}{\text{Transcript Length}i} }{ \sumj \frac{\text{Reads}j}{\text{Transcript Length}j} } \times 10^6 ) | Within-sample comparisons; active pathway identification. | Sum is constant across samples, allowing for better cross-sample comparison than FPKM. | Not sufficient for differential expression analysis without between-sample methods. |

| FPKM/RPKM [1] | ( \text{FPKM}i = \frac{\text{Reads}i}{(\text{Transcript Length}_i \times \text{Total Fragments})} \times 10^9 ) | Within-sample comparisons. | Corrects for both gene length and sequencing depth. | Values are not directly comparable between samples due to compositional bias. |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) [3] [1] | Trims extreme log-fold changes (M-values) and absolute expression (A-values) to compute a scaling factor relative to a reference sample. | Between-sample comparisons; differential expression analysis. | Robust to a high proportion of differentially expressed genes. | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed. |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) [3] | Calculates a scaling factor as the median of the ratios of each gene's count to its geometric mean across all samples. | Between-sample comparisons; differential expression analysis. | Implemented in DESeq2; performs well even with many zeros. | Sensitive to outliers; assumes few genes are differentially expressed. |

| GeTMM (Gene length corrected TMM) [3] | Applies TMM normalization to counts that have first been adjusted for gene length (like in TPM). | Combines within- and between-sample comparisons. | Allows for comparison of expression levels both within and across samples. | A newer method with less established benchmarks across diverse datasets. |

The choice between these methods has a demonstrable impact on downstream biological conclusions. A 2024 benchmark study systematically evaluated normalization methods in the context of building condition-specific metabolic models using the iMAT algorithm [3]. The study revealed that:

- Between-sample methods (TMM, RLE, GeTMM) produced metabolic models with considerably lower variability in the number of active reactions compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [3].

- Models derived from RLE, TMM, or GeTMM normalized data more accurately captured disease-associated genes, with an average accuracy of ~0.80 for Alzheimer's disease and ~0.67 for lung adenocarcinoma [3].

- Covariate adjustment (e.g., for age, gender) further increased the accuracy of models for all normalization methods, highlighting the importance of accounting for known biological confounders [3].

Experimental Protocols for Normalization and Evaluation

Protocol 1: Generating a Count Matrix for Downstream Normalization

Objective: To process raw RNA-seq FASTQ files into a gene-level count matrix, which serves as the input for all downstream normalization and differential expression analyses [14].

Materials:

- Computing Environment: Unix/Linux server or high-performance computing cluster.

- Software:

- FastQC: For initial quality control of raw FASTQ files.

- Trimmomatic or fastp: For adapter trimming and quality filtering.

- STAR aligner: For splicing-aware alignment of reads to a reference genome.

- featureCounts or HTSeq: For quantifying reads that map to genes.

Procedure:

- Quality Control: Run FastQC on all raw FASTQ files to assess per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and other potential issues.

- Trimming and Filtering: Use Trimmomatic or fastp to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases. Example command for fastp:

fastp -i input_R1.fastq.gz -I input_R2.fastq.gz -o clean_R1.fastq.gz -O clean_R2.fastq.gz - Alignment: Align the cleaned reads to the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using STAR.

STAR --genomeDir /path/to/GenomeDir --readFilesIn clean_R1.fastq.gz clean_R2.fastq.gz --runThreadN 12 --outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate --outFileNamePrefix sample_aligned. - Quantification: Generate the gene-level count matrix by counting the number of reads overlapping each gene's exons using featureCounts.

featureCounts -T 8 -p -a annotation.gtf -o counts.txt *.bam

Output: A counts matrix file (counts.txt) where rows are genes, columns are samples, and values are raw integer counts. It is critical to use these raw counts, not pre-normalized values, as input for between-sample normalization methods in differential expression tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [14].

Protocol 2: Implementing and Evaluating Normalization Methods

Objective: To apply different normalization methods to the count matrix and evaluate their performance in a differential expression workflow.

Materials:

- Computing Environment: R statistical software environment.

- R/Bioconductor Packages:

DESeq2(for RLE),edgeR(for TMM),tximportorlimma.

Procedure:

- Data Input: Load the raw count matrix and sample metadata into R.

- Apply Normalization Methods:

- For RLE: Create a

DESeqDataSetobject and useestimateSizeFactors()to calculate RLE normalization factors. Thecounts()function withnormalized=TRUEreturns normalized counts. - For TMM: Create a

DGEListobject in edgeR and usecalcNormFactors()to calculate TMM scaling factors. - For TPM: Calculate using the formula in Table 1. Note that gene lengths must be estimated, often from the genomic annotations (GTF file) used in alignment.

- For RLE: Create a

- Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA): Evaluate the effect of normalization.

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize sample-to-sample distances. Well-normalized data should show clear separation by experimental condition, not by technical batch.

- Check for the presence of batch effects using PCA and sample distance heatmaps. If batches are present, proceed to batch correction.

- Batch Effect Correction: For data integration across studies, use the

removeBatchEffect()function in thelimmapackage or theComBat()function in thesvapackage on normalized (e.g., log-transformed TMM or RLE) data [1]. - Downstream Analysis: Proceed with differential expression testing using the appropriate statistical models in

DESeq2oredgeR, which incorporate their respective normalization factors internally.

Evaluation Checkpoint: A key indicator of successful normalization is reduced technical variability in EDA plots. Between-sample normalization methods like TMM and RLE are expected to produce more tightly clustered replicates in PCA plots compared to unnormalized data or within-sample methods when the goal is cross-sample comparison [3].

Table 2: Key Software and Resources for RNA-seq Normalization

| Tool / Resource Name | Category | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [14] | R Package / Differential Expression | Performs RLE normalization and differential expression analysis using a negative binomial model. | Industry standard; highly robust for experiments with a small number of replicates. |

| edgeR [14] | R Package / Differential Expression | Performs TMM normalization and differential expression analysis. | Powerful for complex experimental designs and highly expressed genes. |

| STAR Aligner [14] | Read Alignment | Aligns RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, accounting for splice junctions. | Fast and accurate; generates the BAM files required for read counting. |

| fastp [15] | Quality Control | Performs rapid and integrated adapter trimming and quality filtering. | Improves mapping rates and data quality; user-friendly with comprehensive reporting. |

| limma [1] | R Package / Batch Correction | Removes known batch effects from normalized expression data. | Essential for meta-analyses combining public and in-house datasets. |

| Omics Playground [1] | Web Platform / Integrated Analysis | Provides a user-friendly interface for normalization and exploratory analysis. | Ideal for bench scientists without a coding background. |

A Practical Toolkit: Comparing and Applying Key Normalization Methods

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, raw read counts mapped to genes are influenced by technical factors that can mask true biological expression levels. Within-sample normalization is the critical first step that adjusts raw count data to account for two primary technical variables: transcript length and sequencing depth [1]. Longer genes naturally accumulate more reads than shorter genes at identical expression levels, while varying sequencing depths across samples cause differences in total read counts [1]. Without proper normalization, these technical artifacts prevent accurate comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample.

This protocol focuses on three fundamental within-sample normalization methods: CPM (Counts Per Million), FPKM/RPKM (Fragments/Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads), and TPM (Transcripts Per Million). These methods enable researchers to compare the relative abundance of different genes within a single sample, which is essential for exploratory analyses including expression profiling, clustering, and pathway analysis [1] [16]. Understanding the appropriate application of each method is crucial for generating biologically meaningful results from RNA-seq data.

Normalization Methods: Computational Foundations

CPM (Counts Per Million)

CPM (also known as RPM, Reads Per Million) represents the simplest normalization approach, adjusting solely for sequencing depth without accounting for gene length variations [17]. This method is suitable for sequencing protocols where read generation is independent of gene length, such as 3' tag sequencing [17].

Calculation Formula: CPM = (Reads mapped to gene / Total mapped reads) × 10^6 [17]

Key Characteristics:

- Normalizes only for sequencing depth

- Does not account for gene length bias

- Suitable for within-sample comparisons when gene length is not a concern

- Inappropriate for comparing expression across genes of different lengths [17]

Example Calculation: For a gene with 5,000 mapped reads in a library of 4 million total mapped reads: CPM = (5,000 / 4,000,000) × 10^6 = 1,250 [17]

RPKM and FPKM

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) and its paired-end equivalent FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped fragments) normalize for both sequencing depth and gene length, enabling more accurate within-sample gene expression comparisons [18] [16].

Calculation Formula: RPKM (or FPKM) = Reads (or fragments) mapped to gene / (Gene length in kb × Total mapped reads in millions) [18]

Step-by-Step Calculation:

- Divide read counts by the total reads in the sample and multiply by 1,000,000 to get "per million" scaling factor

- Divide this result by the length of the gene in kilobases [18]

Key Characteristics:

- Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length

- RPKM designed for single-end RNA-seq, FPKM for paired-end RNA-seq [18] [16]

- Enables comparison of expression levels between genes of different lengths within the same sample

- Sum of RPKM/FPKM values can differ between samples, complicating cross-sample comparisons [18]

TPM (Transcripts Per Million)

TPM represents an evolution in normalization methodology that addresses a key limitation of RPKM/FPKM by maintaining consistent sums across samples [18]. The calculation involves the same factors as RPKM/FPKM but applies them in reverse order.

Calculation Formula: TPM = (Reads mapped to gene / Gene length in kb) / (Sum of all length-normalized reads) × 10^6 [18]

Step-by-Step Calculation:

- Divide read counts by the length of each gene in kilobases → yields RPK (Reads Per Kilobase)

- Sum all RPK values in a sample and divide by 1,000,000 → "per million" scaling factor

- Divide RPK values by this scaling factor → TPM [18]

Key Characteristics:

- Normalizes for gene length first, then sequencing depth

- Sum of all TPMs in each sample is identical (1,000,000)

- Enables comparison of the proportion of reads mapped to a gene across samples

- Considered a more accurate measure of relative RNA molar concentration [18] [19]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Normalization Factors | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Sequencing depth only | Within-sample comparisons when gene length is uniform | Simple calculation | Fails to account for gene length bias [17] |

| RPKM/FPKM | Sequencing depth + Gene length | Gene expression comparisons within a single sample | Accounts for both technical variables | Sum varies between samples; problematic for cross-sample comparison [18] [1] |

| TPM | Gene length + Sequencing depth | Gene expression comparisons within and across samples | Constant sum across samples; better for proportions | Still sensitive to RNA population composition differences [18] [19] |

Table 2: Mathematical Formulae for Normalization Methods

| Method | Formula | Component Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| CPM | ( CPM = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{Total mapped reads}} \times 10^6 ) [17] | Total mapped reads: Sum of all reads aligned to the reference |

| RPKM/FPKM | ( RPKM = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{Gene length (kb)} \times \frac{\text{Total mapped reads}}{10^6}} ) [18] | Gene length: Total length of exons in kilobases |

| TPM | ( TPM = \frac{\frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{Gene length (kb)}}}{\sum(\frac{\text{All mapped reads}}{\text{Respective gene lengths (kb)}})} \times 10^6 ) [18] | Gene length: Total length of exons in kilobases |

Computational Workflows and Protocols

TPM Normalization Protocol

The following workflow illustrates the complete TPM calculation process for within-sample gene expression analysis:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Input Raw Read Counts: Begin with a count matrix containing raw read counts mapped to each gene for a single sample [18].

Calculate RPK Values: For each gene, divide the raw read count by the gene length in kilobases: RPK = Read count / Gene length (kb) [18]

Sum RPK Values: Calculate the sum of all RPK values for the sample.

Compute Scaling Factor: Divide the RPK sum by 1,000,000 to generate the sample-specific scaling factor [18].

Calculate TPM Values: For each gene, divide the RPK value by the scaling factor to obtain the final TPM value.

Quality Assessment: Verify that the sum of all TPM values in the sample equals approximately 1,000,000 [18].

Implementation in Python:

RPKM/FPKM Normalization Protocol

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Input Raw Read Counts: Start with raw read counts for each gene in a single sample.

Calculate RPM: Divide the read count for each gene by the total mapped reads in the sample, then multiply by 1,000,000: RPM = (Read count / Total mapped reads) × 10^6 [18]

Normalize for Gene Length: Divide the RPM values by the gene length in kilobases to obtain RPKM/FPKM values [18].

Verification: Unlike TPM, the sum of RPKM/FPKM values will vary between samples, which is expected behavior for this method.

Implementation in Python:

CPM Normalization Protocol

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Input Raw Read Counts: Begin with raw read counts for each gene.

Calculate Scaling Factor: Divide the total mapped reads by 1,000,000.

Compute CPM Values: Divide each gene's read count by the scaling factor [17].

Application: Use CPM values for within-sample comparisons when gene length bias is not a concern.

Implementation in Python:

Experimental Considerations and Best Practices

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate normalization method depends on the experimental design and analytical goals:

Use CPM when analyzing sequencing protocols where read count is independent of gene length, or when making within-sample comparisons where relative differences in expression are more important than absolute quantification [17].

Use RPKM/FPKM for traditional within-sample gene expression comparisons where both sequencing depth and gene length normalization are required. This method remains appropriate for comparing expression levels of different genes within the same sample [1] [16].

Use TPM when performing both within-sample and between-sample comparisons, or when the relative proportion of transcripts is biologically meaningful. TPM is particularly valuable when pooling data from multiple samples for integrated analysis [18] [20].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Despite their utility, within-sample normalization methods have important limitations:

RNA Population Composition: RPKM, FPKM, and TPM values represent relative abundance within the sequenced RNA population, which can vary significantly depending on sample preparation protocols (e.g., poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion) [19]. Comparing normalized values across studies using different protocols can be problematic.

Cross-Sample Comparisons: While TPM improves comparability between samples, none of these within-sample methods adequately address biological variability or batch effects between samples [1]. For rigorous differential expression analysis, additional between-sample normalization methods such as TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) or DESeq2's median ratio method are recommended [20] [12].

Low Expression Genes: All within-sample normalization methods can be sensitive to technical noise for lowly expressed genes, particularly when gene length corrections are applied [20].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Normalization Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme variation in normalized values between samples | Different RNA population composition | Verify consistent sample preparation protocols; avoid comparing across different RNA enrichment methods [19] |

| Poor clustering in exploratory analysis | Inadequate normalization for experimental design | Apply between-sample normalization (TMM, DESeq2) after within-sample normalization [20] [12] |

| Inconsistent results for low-abundance transcripts | Technical noise amplified by normalization | Apply expression filters; use statistical methods designed for low-count genes [20] |

| Discrepancies between paired-end and single-end data | Use of RPKM for paired-end data | Use FPKM for paired-end data to account for fragment-based counting [18] [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Normalization Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| bioinfokit (Python) | CPM, RPKM, TPM normalization | Accessible normalization implementation with example datasets [17] |

| DESeq2 (R/Bioconductor) | Between-sample normalization using median ratio method | Differential expression analysis following within-sample normalization [12] |

| edgeR (R/Bioconductor) | TMM normalization for between-sample comparisons | RNA-seq analysis when composition bias is a concern [1] [12] |

| Salmon/Kallisto | Alignment-free transcript quantification | Rapid TPM calculation without generating BAM files [20] [19] |

| Scater/Scanpy | Single-cell RNA-seq normalization | Specialized methods for single-cell data (CP10K, deconvolution) [21] [22] |

Quality Control Metrics

Library Size: Total mapped reads should be consistent across samples; significant variations may require additional normalization [12].

Gene Length Distribution: Ensure consistent gene length annotations across all samples to prevent normalization artifacts.

TPM Sum Verification: Confirm that TPM values sum to approximately 1,000,000 per sample as a quality check [18].

Sequence Protocol Consistency: Validate that all samples were prepared using compatible RNA selection methods (e.g., all polyA+ selected or all rRNA-depleted) [19].

Within-sample normalization using CPM, RPKM/FPKM, and TPM provides the foundation for accurate gene expression analysis in RNA-seq experiments. While each method offers distinct advantages, TPM has emerged as the preferred approach for many applications due to its consistent sum across samples and more intuitive interpretation as a proportion of the total transcriptome [18] [20]. However, researchers must recognize that these within-sample methods represent only the first step in comprehensive RNA-seq data normalization, and should be complemented with appropriate between-sample normalization approaches when conducting comparative analyses. By implementing these protocols with attention to technical considerations and potential pitfalls, researchers can generate more reliable and biologically meaningful results from their transcriptomic studies.

In RNA-Seq differential expression analysis, normalization is a critical preprocessing step that ensures accurate comparison of gene expression levels between samples. Technical variations, particularly in sequencing depth and RNA composition, can introduce systematic biases that obscure true biological differences. Without proper normalization, these technical artifacts can lead to both false positives and false negatives in downstream differential expression testing. Between-sample normalization methods specifically address these issues by adjusting counts to make them comparable across different libraries. Among the various strategies developed, the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method implemented in the edgeR package and the Relative Log Expression (RLE) method used by DESeq2 have emerged as two of the most widely adopted and robust approaches [23] [24]. These methods operate on the fundamental assumption that in most RNA-Seq experiments, the majority of genes are not differentially expressed, allowing them to estimate technical biases from the data itself [25] [26]. This protocol provides detailed methodologies for implementing both TMM and RLE normalization, along with comparative analysis to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate method for their experimental context.

Theoretical Foundations

The Normalization Necessity: Accounting for Technical Biases

RNA-Seq count data is influenced by several technical factors that must be accounted for before meaningful biological comparisons can be made. Sequencing depth (library size) varies between samples, where samples with greater depth naturally yield higher counts for most genes regardless of true expression levels. Perhaps more subtly, RNA composition effects occur when a few highly expressed genes in one condition consume a substantial portion of the sequencing resources, thereby proportionally reducing the counts observed for all other genes in that sample [23] [26]. This composition effect can create the false appearance of differential expression for genes that are not truly differentially expressed. As highlighted by Robinson and Oshlack, without proper normalization, "if a large number of genes are unique to, or highly expressed in, one experimental condition, the sequencing 'real estate' available for the remaining genes in that sample is decreased" [26]. This fundamental understanding drives the need for sophisticated normalization methods that go beyond simple library size scaling.

TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) Method Theory

The TMM normalization method, implemented in the edgeR package, is based on the principle of relative scaling between samples. For each pair of samples, TMM calculates gene-wise log-fold-changes (M-values) and absolute expression levels (A-values), then computes a weighted trimmed mean of the M-values [27] [26]. The trimming process excludes the most extreme M-values (default: 30% from each end, 5% from the top) and the genes with very high or low expression levels, making the method robust to differentially expressed genes. The key biological assumption underlying TMM is that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed between samples [25]. Mathematically, TMM estimates the relative RNA production efficiency between samples, producing a normalization factor that converts observed library sizes into effective library sizes that account for RNA composition biases [28] [27]. These effective library sizes are then used to compute normalized counts, typically expressed as counts per million (CPM) [28].

RLE (Relative Log Expression) Method Theory

The RLE normalization method, used by DESeq2, employs a median-of-ratios approach that similarly assumes most genes are not differentially expressed [23]. The method operates through a multi-step process: first, it creates a pseudo-reference sample by calculating the geometric mean across all samples for each gene; second, it computes the ratio of each sample to this pseudo-reference; third, it takes the median of these ratios for each sample to derive the size factor (normalization factor) [23]. The RLE method is particularly robust to imbalances in up-/down-regulation and large numbers of differentially expressed genes, as the median ratio is less influenced by extreme values [23]. Unlike TMM, which typically compares samples to a single reference, RLE considers all samples simultaneously when creating the pseudo-reference, making it particularly suited for complex experimental designs with multiple conditions.

Table 1: Theoretical Comparison of TMM and RLE Normalization Methods

| Feature | TMM (edgeR) | RLE (DESeq2) |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Relative Log Expression |

| Key Assumption | Most genes are not DE | Most genes are not DE |

| Statistical Approach | Weighted trimmed mean of log expression ratios | Median of ratios to pseudo-reference sample |

| Primary Adjustment | Effective library size | Count scaling factors |

| Robustness Features | Trimming of extreme values, weighting by precision | Median-based central tendency |

| Implementation | Pairwise sample comparison | Global sample comparison |

Methodology and Protocols

TMM Normalization Protocol with edgeR

The TMM normalization protocol using edgeR follows a structured workflow that begins with data input and proceeds through normalization factor calculation to normalized count generation:

Step 1: Create DGEList Object

Step 2: Calculate TMM Normalization Factors

Step 3: Generate Normalized Expression Values

The calcNormFactors function performs the core TMM calculation, determining normalization factors that reflect compositional biases. These factors are incorporated into the effective library sizes (original library size × normalization factor), which are then used by the cpm function to generate normalized counts [28] [27]. It is important to note that edgeR does not store "TMM-normalized counts" internally, but rather uses the normalization factors during statistical testing for differential expression [28].

RLE Normalization Protocol with DESeq2

The RLE normalization protocol using DESeq2 follows a similarly structured approach but with different function calls and object types:

Step 1: Create DESeqDataSet Object

Step 2: Perform RLE Normalization

Step 3: Extract Normalized Counts