RNA-Seq Validation with qPCR: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of qPCR in validating RNA-Seq data.

RNA-Seq Validation with qPCR: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of qPCR in validating RNA-Seq data. It explores the foundational reasons for validation, from confirming subtle gene expression changes in heterogeneous diseases like osteoarthritis to meeting publication requirements. The content delves into methodological best practices, including robust experimental design and the use of novel bioinformatics tools for reference gene selection. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies, supported by recent large-scale benchmarking studies. Finally, the article offers a balanced perspective on when validation is essential versus when it may be redundant, empowering scientists to make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and clinical translatability of their transcriptomic findings.

The Unavoidable Why: Core Reasons for qPCR Validation in the RNA-Seq Era

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has become a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, offering an unbiased, genome-wide view of RNA expression. However, the sophisticated nature of this technology means its results are not infallible; they are contingent upon a complex chain of technical steps, each a potential point of failure. This guide examines the critical technical limitations that can compromise RNA-Seq data reliability and underscores the necessity of orthogonal validation, particularly with qPCR, to ensure robust and reproducible findings, especially in critical fields like drug discovery and clinical diagnostics.

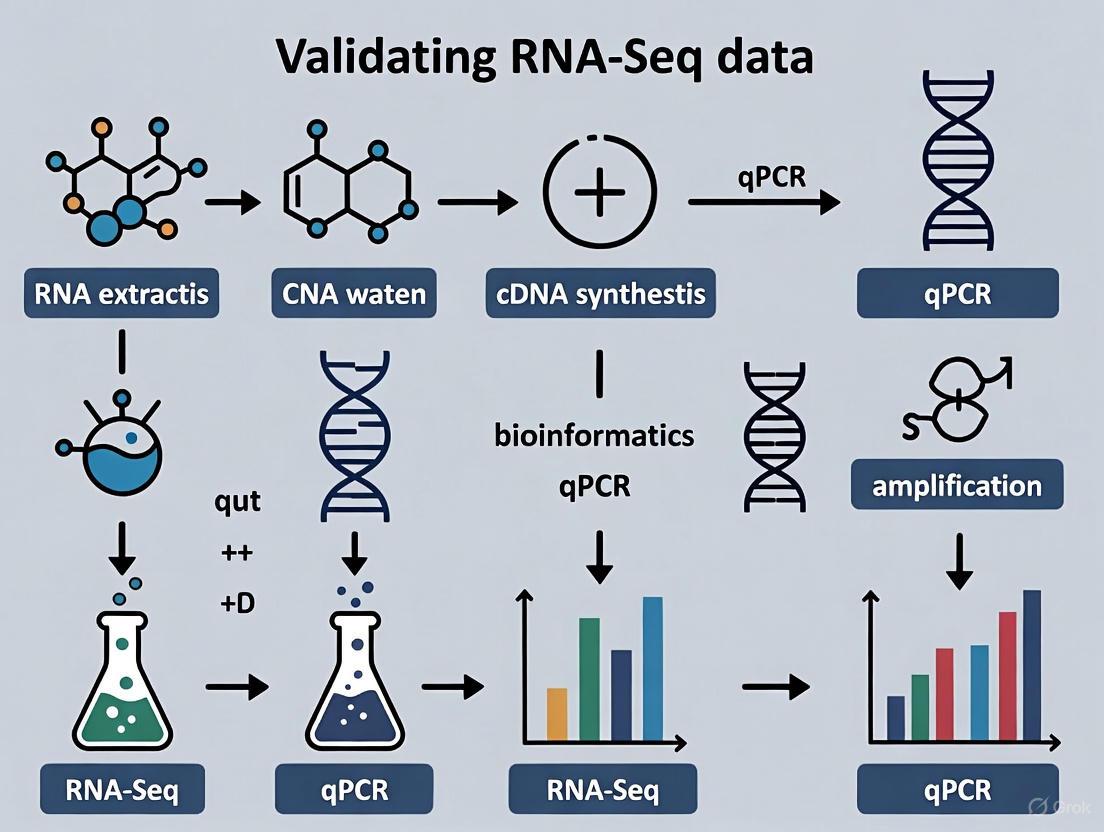

The RNA-Seq Workflow and Its Inherent Vulnerabilities

The process of transforming biological RNA into interpretable sequencing data is a multi-stage pipeline where technical artifacts can be introduced at every step. Understanding these vulnerabilities is the first step toward mitigating their impact. The following diagram outlines a typical bulk RNA-Seq workflow and highlights key points where reliability can falter.

Critical Technical Limitations and Failure Points

RNA-Seq data can be skewed by numerous factors, from the initial sample quality to the final computational decisions. This section details the primary sources of technical bias and error.

Sample Quality and RNA Integrity

RNA quality is the foundational element of a successful sequencing study, and its degradation is a problem that cannot be rectified in downstream analysis [1].

- RNA Integrity Number (RIN): A commonly used metric for RNA quality. While a RIN greater than 7 is generally recommended for high-quality sequencing, this can be challenging to achieve with certain sample types like blood [1]. Degraded RNA, with a low RIN, leads to 3' bias in transcript coverage and poor detection of longer transcripts.

- Impact on Poly-A Selection: Standard mRNA sequencing workflows that use oligo-dT beads to capture polyadenylated RNA are particularly unsuitable for degraded samples, as they rely on an intact poly-A tail [1]. For such samples, methods utilizing random priming and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion are preferred.

- Contamination: The accuracy of RNA quantification and sequencing can be severely affected by contaminants. The 260/280 and 260/230 ratios should be assessed during extraction to ensure minimal protein or DNA contamination [1].

Library Preparation Biases

The process of converting RNA into a sequenceable library is a major source of technical variability.

- Stranded vs. Unstranded Libraries: A key early decision is whether to use a stranded protocol. Stranded libraries preserve the information about which DNA strand was transcribed, which is critical for identifying overlapping genes on opposite strands and for accurate annotation of long non-coding RNAs [1]. While unstranded protocols are simpler and cheaper, they discard this valuable information.

- rRNA Depletion and Off-Target Effects: Ribosomal RNA can constitute up to 80% of cellular RNA. If sequenced, it consumes most of the sequencing reads, dramatically increasing the cost to obtain meaningful data on messenger and non-coding RNAs [1]. Depletion techniques (e.g., using RNAseH) are used to remove rRNA. However, this step is not without its own issues; it can be highly variable between labs and may have off-target effects, inadvertently depleting some genes of interest while enriching others [1].

- Input Material and PCR Amplification: Low input RNA can lead to over-amplification during the library construction PCR. This results in a high duplication rate, where many sequencing reads are PCR copies of the same original fragment, reducing the complexity of the library and potentially skewing quantitative measurements [2].

Normalization and Analytical Challenges

After sequencing, the raw data must be processed and normalized, a step fraught with statistical pitfalls that can lead to incorrect biological conclusions.

- The Normalization Imperative: Raw read counts from RNA-Seq are not directly comparable between samples because the total number of sequenced reads (sequencing depth) varies. A gene in a sample with more total reads will naturally have a higher count, even if its true expression level is identical [3]. Normalization is the mathematical process of correcting for this and other biases.

- Common Normalization Methods: Different methods correct for different types of biases. Simple methods like Counts per Million (CPM) only correct for sequencing depth, while RPKM/FPKM and Transcripts per Million (TPM) correct for both sequencing depth and gene length, making expression levels comparable between different genes within a sample [3]. For differential expression analysis, more advanced methods like the median-of-ratios (DESeq2) and TMM (edgeR) are designed to be robust against the presence of a few highly expressed genes that can distort the count distribution [3].

- Inadequate Experimental Design: The reliability of differential expression analysis is strongly dependent on thoughtful experimental design. A lack of sufficient biological replicates is a common weakness. While three replicates per condition is often considered a minimum, this may be insufficient if biological variability is high [3]. With only two replicates, the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced, and a single replicate does not allow for any robust statistical inference [3].

Table 1: Common Normalization Methods and Their Properties

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling; heavily affected by highly expressed genes [3]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No | Allows within-sample gene comparison; not ideal for cross-sample comparison [3]. |

| TPM | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | An improvement over RPKM/FPKM; better for cross-sample comparisons [3]. |

| median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust against composition bias; used for differential expression [3]. |

| TMM (edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust against composition bias; used for differential expression [3]. |

Limitations in Transcriptome Characterization

Despite its power, standard short-read RNA-Seq has inherent limitations in resolving complex aspects of transcriptome biology.

- Incomplete Transcriptome Annotation: Probe-based methods (like microarrays) and short-read sequencing can only detect RNAs that have been previously annotated and for which specific probes exist. Novel RNAs, such as those appearing in intergenic and intronic regions, may be sequenced but remain unannotated [1].

- The Isoform Resolution Problem: A significant limitation of short-read RNA-Seq is its difficulty in accurately resolving full-length splice isoforms. While it can detect alternative splicing events, short reads (typically 50-300 bp) must be computationally assembled to reconstruct the complete transcript, which is error-prone for long or complex isoforms [4]. This is a key area where long-read RNA sequencing (e.g., from PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) is transformative, as it enables the end-to-end sequencing of full-length transcripts, providing unambiguous isoform information [4].

The Indispensable Role of qPCR Validation

Given the multitude of technical vulnerabilities in the RNA-Seq pipeline, validation of key results is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for rigorous science.

qPCR serves as a robust orthogonal method to confirm RNA-Seq findings. Its strengths lie in its high sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic range. Unlike RNA-Seq, which provides a relative snapshot of the entire transcriptome, qPCR can be optimized for absolute quantification of a smaller set of critical targets with high precision. Validating a subset of differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-Seq using qPCR boosts confidence in the overall dataset and helps filter out false positives arising from the technical issues described above [5].

A Protocol for Orthogonal Validation

A structured approach to validation ensures that results are comparable and meaningful.

- Gene Selection: Select a panel of target genes (e.g., 5-10) from the RNA-Seq results, including both significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes.

- Reference Gene Validation: The accuracy of qPCR relies on stable reference genes for normalization. Do not assume traditional "housekeeping" genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) are stable under your specific experimental conditions. Their expression can vary, leading to inaccurate results [5]. Stability should be determined empirically using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder. RNA-Seq data itself can be mined to identify new, more stable candidate reference genes for a given study context [5].

- cDNA Synthesis: Use the same RNA samples that were submitted for RNA-Seq (or aliquots from the same extraction) to reverse-transcribe RNA into cDNA. This controls for variability originating from the biological source itself.

- qPCR Execution: Perform qPCR in technical replicates for each biological sample. The use of probe-based chemistry (e.g., TaqMan) can offer greater specificity than intercalating dyes.

- Data Analysis and Correlation: Calculate relative expression changes (e.g., using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method) normalized to the validated reference genes. A strong positive correlation between the fold-change values obtained by RNA-Seq and qPCR confirms the technical reliability of the primary sequencing data.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials used in RNA-Seq and validation workflows, along with their critical functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for RNA-Seq and Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity immediately upon sample collection (e.g., PAXgene for blood) [1]. | Essential for preserving high-quality RNA, especially from sensitive tissues; prevents degradation-driven bias. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for coding and non-coding RNAs of interest [1]. | Choice between probe-based (magnetic beads) and RNase H-based methods involves trade-offs in enrichment efficiency and reproducibility [1]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Create libraries that retain strand-of-origin information for transcripts [1]. | Preferred for most applications, especially when studying anti-sense transcription or complex genomes. |

| Spike-in Control RNAs | Exogenous RNA added to samples in known quantities [6]. | Used to monitor technical performance, assess dynamic range, sensitivity, and normalize for sample-specific biases. |

| qPCR Assays | Target-specific primers and probes for validating gene expression [5]. | Design should be optimized for efficiency and specificity. Probe-based assays are generally more specific. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Genes with stable expression used for qPCR normalization [5]. | Must be empirically validated for each experimental condition; failure to do so is a major source of error. |

RNA-Seq is a powerful but imperfect tool. Its reliability can falter due to factors ranging from degraded starting material and biased library preparation to improper statistical normalization and inadequate experimental design. In a research landscape increasingly driven by genomic data, particularly in drug discovery and clinical applications, these technical limitations carry significant consequences. Therefore, orthogonal validation of RNA-Seq results, primarily through qPCR, is a non-negotiable step in the scientific process. It transforms a potentially noisy high-throughput dataset into a verified, trustworthy foundation for biological discovery and translational application.

The Imperative for Orthogonal Confirmation in Peer-Reviewed Publication

Next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has unequivocally established itself as the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression analysis in research and clinical applications. Its unparalleled capacity for novel transcript discovery, detection of splice variants, and broad dynamic range has positioned it as a superior alternative to microarray technology [7] [8]. However, this technological supremacy raises a critical methodological question: in an era of sophisticated sequencing platforms, does orthogonal confirmation—particularly through quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)—remain an essential requirement for peer-reviewed publication? The scientific community exhibits divided opinions on this issue; some researchers consider validation an indispensable step for verifying key findings, while others view it as an unnecessary relic from the microarray era [9]. This guide examines the technical and methodological evidence supporting the continued necessity of orthogonal confirmation, providing researchers with a structured framework for determining when validation is imperative and how to execute it with scientific rigor.

The Concordance Debate: Quantitative Evidence from Platform Comparisons

Establishing the Baseline Correlation Between Platforms

Multiple independent studies have systematically evaluated the correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR expression measurements, revealing generally high but imperfect concordance. A comprehensive benchmark analysis utilizing whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes demonstrated high expression correlation across five common RNA-Seq workflows, with Pearson correlation coefficients (R²) ranging from 0.798 to 0.845 [7]. Fold-change correlations between RNA-Seq and qPCR were even stronger, with R² values between 0.927 and 0.934, indicating excellent agreement when comparing expression differences between sample conditions [7].

However, these encouraging overall correlations mask critical discrepancies in specific gene subsets. The same study revealed that 15-19% of genes showed non-concordant differential expression results between RNA-Seq and qPCR [7]. While most discrepancies occurred with low fold changes (<2), approximately 1.8% of genes exhibited severe non-concordance, with these problematic genes typically being shorter, having fewer exons, and showing lower expression levels [7].

Comparative Analysis of RNA-Seq and qPCR Performance

Table 1: Concordance Analysis Between RNA-Seq and qPCR Technologies

| Performance Metric | Concordance Level | Problematic Gene Characteristics | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Expression Correlation | R² = 0.80-0.85 [7] | Lower expressed genes | Consider platform-specific bias |

| Fold-Change Correlation | R² = 0.93-0.93 [7] | Genes with FC < 2 | Interpret small fold-changes cautiously |

| Differential Expression Concordance | 81-85% of genes [7] | Shorter genes with fewer exons | Prioritize validation for key short genes |

| Severe Non-Concordance | ~1.8% of genes [7] | Low expression + short length | Essential validation for story-critical genes |

Recent technological comparisons extend beyond qPCR. When evaluating RNA-Seq against established NanoString technology in Ebola-infected non-human primates, researchers observed strong correlation with Spearman coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.88 across most samples [10]. This demonstrates that discordance issues are not unique to qPCR but represent broader challenges in transcriptomic measurement consistency.

When Is Orthogonal Confirmation Non-Negotiable?

High-Risk Scenarios Mandating Validation

The collective evidence supports a nuanced, risk-based approach to validation rather than a universal mandate. The following scenarios represent circumstances where orthogonal confirmation becomes essential:

Low-Expression Genes with Critical Findings: When a study's central conclusion depends on differential expression patterns in low-abundance transcripts, qPCR validation is strongly recommended. The benchmark study by Everaert et al. revealed that approximately 93% of non-concordant genes between RNA-Seq and qPCR exhibited fold changes lower than 2, with the most severely discordant genes typically expressed at low levels [9] [7].

Minimal Expression Differences with Biological Significance: Genes displaying small but biologically crucial fold changes (typically <1.5) represent high-risk candidates for misinterpretation without orthogonal confirmation [9].

Foundation of Entire Narratives on Few Genes: When a research story depends entirely on expression patterns of a limited number of genes—particularly if they exhibit the problematic characteristics outlined in Table 1—validation becomes indispensable [9].

Extension to Additional Samples/Conditions: qPCR provides an efficient method to verify RNA-Seq-identified expression patterns across expanded sample sets, additional time points, or related experimental conditions not included in the original sequencing [9].

Validation Exceptions: When RNA-Seq Stands Alone

In contrast, orthogonal confirmation may be unnecessary under these conditions:

State-of-the-Art Experimental and Computational Workflows: When RNA-Seq experiments employ rigorous methodologies, adequate biological replication, and validated analysis pipelines, the resulting data is generally reliable without confirmation [9].

Genome-Wide Discovery Studies: Research focusing on overall transcriptomic patterns rather than individual genes may not require validation, particularly when findings are supported by strong statistical evidence across gene sets [9].

High-Expression Genes with Large Fold Changes: Genes with robust expression levels and substantial differential expression (typically >4-fold) demonstrate high inter-platform concordance and may not necessitate confirmation [7].

Methodological Framework for Technically Sound Validation

Reference Gene Selection: Moving Beyond Traditional Housekeeping Genes

The critical foundation of reliable qPCR validation rests on appropriate reference gene selection. Traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) often demonstrate unacceptable expression variability across biological conditions, potentially introducing systematic errors [11] [12]. A superior approach leverages RNA-Seq data itself to identify optimally stable reference genes.

The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software implements a rigorous filtering algorithm to identify optimal reference genes based on five criteria applied to Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values from RNA-Seq data [11]:

- Expression >0 TPM across all samples

- Standard variation of log₂(TPM) <1

- No exceptional expression (>2× average of log₂ expression)

- Average log₂ expression >5

- Coefficient of variation <0.2

This methodology successfully identified STAU1 as the most stable reference gene for endometrial decidualization studies, outperforming conventionally used references like β-actin [5]. Similarly, in canine gastrointestinal tissue research, ribosomal protein genes RPS5 and RPL8 demonstrated superior stability compared to traditional references [12].

Table 2: Strategic Selection of Reference Genes for qPCR Normalization

| Selection Method | Advantages | Limitations | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq Based Selection (GSV) | Data-driven, condition-specific | Requires computational processing | Identified STAU1 for decidualization studies [5] |

| Traditional Housekeeping | Familiar, established | Often unstable across conditions | GAPDH, ACTB frequently variable [11] |

| Global Mean Normalization | No single gene bias | Requires large gene sets (>55 genes) | Optimal for profiling 81 genes in canine tissue [12] |

| Ribosomal Proteins | Often highly stable | Potential co-regulation | RPS5, RPL8 best in canine GI study [12] |

Technical Execution of qPCR Validation

The following protocol outlines a rigorous approach for validating RNA-Seq results via qPCR:

Sample Preparation:

- Use identical RNA samples for both RNA-Seq and qPCR validation to eliminate preparation variability [13].

- For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, use specialized extraction kits (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit) with integrated DNase digestion [14].

- Rigorously assess RNA quality using metrics such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN) prior to analysis [14].

cDNA Synthesis and qPCR Setup:

- Reverse transcribe 0.5μg total RNA using oligo(dT) primers and Supreme Script II reverse transcriptase in 10μL reactions: 42°C for 60 minutes, 70°C for 15 minutes [13].

- Dilute cDNA to 25μL and store at -20°C [13].

- Perform qPCR reactions in 20μL volumes containing: 10μL 2× SYBR Green PreMix, 0.6μL each forward/reverse primer (10μM), 8.7μL RNase-free water, and 0.7μL cDNA template [13].

- Implement three technical replicates for each biological sample to assess technical variability [13].

Primer Design and Validation:

- Design primers with melting temperatures of 57-63°C (optimized to 60°C) and amplicon sizes of 90-180bp [13].

- Validate primer specificity through melt curve analysis, accepting only primers producing single peaks [13].

- Calculate PCR efficiency via standard curve using serial cDNA dilutions [13].

Data Analysis:

- Apply the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method for relative quantification using stable reference genes identified through RNA-Seq analysis [13] [11].

- For large gene sets (>55 genes), consider global mean normalization as a superior alternative to reference genes [12].

Integrated Workflow for Validation Decision-Making

The diagram below illustrates a systematic approach to determining when orthogonal confirmation is necessary:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Critical Reagents for RNA-Seq Validation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA (Qiagen), EZ1 Advanced XL | Nucleic acid isolation with DNA contamination control | Assess DNA contamination via RSeQC percentage of sense strand reads [14] |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq Stranded mRNA (Illumina), SureSelect XTHS2 (Agilent) | RNA-Seq library construction | Quality control via TapeStation, Qubit, LightCycler [14] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Talent qPCR Premix (SYBR Green) | Amplification detection with SYBR Green chemistry | Verify PCR efficiency (80-110%) [13] [12] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Superscript II (Thermo Fisher) | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Use oligo(dT) priming for mRNA [13] |

| NMD Inhibitors | Cycloheximide (CHX) | Block nonsense-mediated decay for truncating variants | Confirm efficacy via SRSF2 NMD-sensitive transcript [15] |

| Reference Gene Software | GSV, NormFinder, GeNorm | Identify stable reference genes from RNA-Seq data | Apply multiple algorithms for consensus [11] [12] |

Orthogonal confirmation of RNA-Seq findings represents a fundamental principle of rigorous scientific methodology rather than a redundant technical exercise. The evidence clearly demonstrates that while RNA-Seq technologies have achieved remarkable sophistication, strategic validation remains essential for specific high-risk scenarios—particularly when research narratives hinge on few genes, low-expression transcripts, or minimal fold changes with biological significance. By implementing the structured framework, methodological protocols, and analytical tools outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and credibility of their transcriptomic findings. In an era of increasing scrutiny regarding scientific reproducibility, targeted orthogonal confirmation stands as a hallmark of rigorous, publication-ready research.

Bolstering Findings from Small-Scale or Low-Replicate RNA-Seq Studies

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the cornerstone technology for transcriptome-wide gene expression profiling. However, studies conducted with a small number of biological replicates or on a limited scale present unique challenges for reliable data interpretation. Such studies are often constrained by sample availability, technical resources, or cost, leading to potential issues with statistical power and reproducibility. Within the broader thesis on why validate RNA-Seq with qPCR research, this guide addresses the critical methodologies for bolstering confidence in findings from such constrained experimental designs. The fundamental rationale for validation stems from the distinct technical biases and limitations inherent in both RNA-seq and qPCR methodologies. While RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide snapshot of transcription, its accuracy can be compromised by factors like alignment errors, sequencing depth, and normalization methods, particularly when biological replication is low. qPCR validation serves as an independent verification using a different technical principle, thereby strengthening the biological conclusions drawn from the initial RNA-seq discovery phase.

Why Validation is Crucial for Underpowered Studies

The Perils of Low Replication

RNA-seq experiments with a small number of biological replicates suffer from reduced statistical power, making it difficult to distinguish true biological variation from technical noise. One study demonstrated that when replication is low, the false-negativity rates of some differential expression analysis methods, such as DESeq2 and the Two-stage Poisson Model (TSPM), can be exceptionally high [16]. This means truly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are often missed. Conversely, other tools like Cuffdiff2 showed a high false-positivity rate, leading to erroneous identification of DEGs [16]. Validation with qPCR on independent biological samples is the preferred method to confirm true-positive DEGs between biological conditions, as it moves beyond in silico analyses or technical replication using the same RNA samples [16].

The Limits of Sample Pooling

In an effort to reduce costs, some researchers pool biological replicate RNA samples before sequencing. However, experimental evidence has shown that this strategy can introduce a "pooling bias" and often results in a low positive predictive value for the DEGs identified [16]. While pooling may retain biological averaging, it eliminates the ability to estimate biological variance from the sequencing data itself. Compared to sequencing individual biological replicates, analyses of RNA-pools showed weak agreement, undermining their ability to reliably predict true-positive DEGs [16]. Therefore, validation becomes paramount when pooling is used as a cost-saving measure in a study.

Designing a Robust Validation Experiment

When is qPCR Validation Appropriate?

qPCR validation is particularly critical in two key scenarios common to small-scale RNA-seq studies. First, it is essential when a second method is necessary to confirm an observation for which there may be skepticism, such as during the peer-review process for publication. Second, it is highly appropriate when the RNA-seq data is based on a small number of biological replicates where proper statistical tests cannot be robustly applied [17]. In this "cost-savings" mindset, using qPCR to focus on a few interesting targets across more samples is an excellent method for validating the RNA-seq results and building out the study.

The Gold Standard: Independent Biological Replication

The most powerful validation design involves performing qPCR on a new set of RNA samples derived from independent biological replicates, not the same samples used for the RNA-seq [18] [17]. Performing qPCR on the same RNA samples only validates the technology, confirming that two different techniques yield the same result from the same source material. In contrast, performing qPCR on a new set of samples validates not only the technology but also the underlying biological response, providing significantly more confidence in the findings [17].

Table 1: Key Considerations for qPCR Validation of RNA-seq Results

| Consideration | Suboptimal Approach | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Selection | Using the same RNA samples for both RNA-seq and qPCR. | Using independent biological replicate samples for qPCR validation [18]. |

| Reference Genes | Selecting traditional "housekeeping" genes (e.g., Actin, GAPDH) based on convention. | Systematically identifying stable, highly-expressed reference genes from the RNA-seq data itself [11]. |

| Candidate Gene Choice | Validating only the most significantly differentially expressed genes. | Including a random selection of DEGs to avoid cherry-picking and assess the false discovery rate [16]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Selecting Optimal Reference Genes for qPCR

A critical, often neglected step in qPCR validation is the selection of appropriate reference genes (also known as endogenous controls). Traditionally, housekeeping genes (e.g., actin and GAPDH) and ribosomal proteins have been used based on their presumed stable expression. However, recent work shows these genes can be modulated depending on the biological condition, leading to misinterpretation of results if they are unstable [11]. The development of software like "Gene Selector for Validation" (GSV) allows researchers to systematically identify the most stable and highly expressed genes directly from their RNA-seq dataset to serve as optimal reference genes [11]. The GSV algorithm uses TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values from the RNA-seq data and applies a series of filters to identify genes that are consistently expressed across all samples with low variation, while also filtering out stable genes with low expression that might fall below the detection limit of qPCR [11].

Workflow for End-to-End Validation

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for validating a small-scale RNA-seq study, from initial sequencing to final confirmation, incorporating best practices for qPCR validation.

Prioritizing Candidate Genes for Validation

With a typically limited budget for qPCR assays, prioritizing which genes to validate is essential. A novel pipeline has been developed that uses evolutionary conservation and preferential expression of genes across brain tissues to prioritize candidate genes, increasing the translational utility of RNA-seq in model organisms [19]. Furthermore, when selecting variable genes for validation, tools like GSV can filter for genes that are within the detection limit of RT-qPCR and show a considerable difference between samples, ensuring that the chosen candidates are suitable for downstream experimental confirmation [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Differential Gene Expression (DEG) Analysis Methods for Low-Replicate Studies

| Method | Reported Performance in Low-Replicate Scenarios | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | High sensitivity and specificity; overall agreement with qPCR was good with a false positivity rate of ~9% [16]. | 76.67% | ~91% | Considered a robust choice for studies with limited replicates [16]. |

| Cuffdiff2 | High false-positivity rate; contributed 87% of false positive DEGs in one validation study [16]. | 51.67% | N/A | Use with caution; high risk of identifying false DEGs [16]. |

| DESeq2 | High specificity but very low sensitivity; identified only a single DEG in one 8-replicate study [16]. | 1.67% | 100% | High false-negativity rate; may miss many true DEGs [16]. |

| TSPM | High false-negativity rate; performance is highly dependent on the number of replicates [16]. | ~5% | ~91% | Not recommended for studies with very low replication [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Validation

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA Isolation Kit | Extraction of high-quality RNA from biological samples. | Ensure high RNA Integrity Number (RIN >7.0) [20]. Use kits that effectively remove genomic DNA. |

| mRNA Enrichment Kit | Selection of polyadenylated mRNA for RNA-seq library prep. | Poly(A) selection is common but can introduce 3' bias. rRNA depletion provides broader transcriptome coverage. |

| Stranded cDNA Library Prep Kit | Construction of sequencing-ready libraries from RNA. | Stranded protocols preserve information on the originating strand of the transcript. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Amplification and fluorescence-based quantification of cDNA. | Use kits with high efficiency and a wide dynamic range. SYBR Green or probe-based chemistries are standard. |

| Molecular Grade Water | A nuclease-free solvent for preparing RNA and PCR reagents. | Essential for preventing RNase-mediated degradation and ensuring reaction specificity. |

| Validated Primers or Probes | Sequence-specific amplification of target and reference genes. | Design for high amplification efficiency (~90-110%). Test for specificity (e.g., single peak in melt curve). |

Findings from small-scale or low-replicate RNA-seq studies can be significantly bolstered through a rigorous and well-designed qPCR validation strategy. This involves moving beyond the same samples used for sequencing to test independent biological replicates, systematically selecting stable reference genes from the transcriptomic data, and being aware of the performance characteristics of different DEG analysis tools. By integrating these practices, researchers can enhance the reliability, credibility, and translational potential of their research, transforming a preliminary transcriptomic finding into a robust biological conclusion.

Enhancing Confidence for Clinical Application and Drug Development

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a foundational tool in biomedical research for genome-wide expression profiling. However, its transition from a research tool to a method informing clinical decisions and drug development pipelines demands rigorous validation to ensure results are reliable, reproducible, and actionable. Orthogonal validation, particularly using reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), provides this critical confidence. While RNA-seq is robust, studies reveal that a small but significant fraction of results can be non-concordant with RT-qPCR findings, especially for lowly expressed genes or those with small fold-changes [9]. This technical guide outlines the necessity, frameworks, and methodologies for validating RNA-seq data, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a roadmap to enhance the credibility of their transcriptomic findings for preclinical and clinical applications.

Why Validate RNA-Seq? Evidence from the Field

The assumption that RNA-seq is inherently reliable requires careful examination, as the consequences of inaccurate data are magnified in clinical and drug development contexts. A comprehensive benchmark study analyzing over 18,000 human genes found that depending on the bioinformatics pipeline, 15–20% of genes were "non-concordant" between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR results [9]. Although the vast majority of these non-concordant cases involved genes with low expression or small fold-changes (<2), approximately 1.8% of genes showed severe discrepancies. This evidence underscores that RNA-seq, while powerful, is not infallible.

Validation becomes paramount in specific scenarios:

- For Key Findings: When a biological conclusion or clinical hypothesis rests on the differential expression of a handful of genes.

- For Low-Abundance Transcripts: When targeting genes with low expression levels, where technical noise is more pronounced.

- For Small Fold-Changes: When biological effects are subtle but purported to be significant.

- For Bridging Studies: When RNA-seq findings from discovery cohorts need to be confirmed in larger validation cohorts using a more accessible and cost-effective method [9].

The transition of RNA-seq into the clinical diagnostic arena further highlights its validated utility. For instance, in oncology, combining RNA-seq with whole exome sequencing (WES) in a cohort of 2,230 tumor samples improved the detection of clinically actionable gene fusions and recovered variants missed by DNA-only testing [14]. In rare Mendelian disorders, clinical RNA-seq tests have been developed that can provide a functional basis for reclassifying variants of uncertain significance, thereby increasing diagnostic yields [21] [22]. These advanced clinical applications were contingent upon extensive analytical and clinical validation, establishing a precedent for any serious translational research endeavor.

Clinical Validation Frameworks for RNA-Seq

Implementing RNA-seq in a regulated environment requires a structured validation framework that moves beyond simple correlation studies. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and benchmarks from established clinical RNA-seq studies:

Table 1: Analytical Performance Benchmarks from Clinical RNA-Seq Validations

| Validation Component | Sample Type(s) | Key Metrics and Benchmarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Diagnostic Test | Fibroblasts, Blood (130 samples) | Established gene-/junction-specific reference ranges from control data; tested on 40 positive controls with known diagnostic findings. | [22] |

| Integrated Tumor Portrait | Fresh Frozen and FFPE Tumors (2230 samples) | Analytical validation using reference samples with 3042 SNVs and 47,466 CNVs; orthogonal confirmation in patient samples. | [14] |

| Minimally Invasive Rare Disease | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Expression of ~80% of intellectual disability/epilepsy panel genes; ability to detect splicing defects and NMD. | [21] |

These studies demonstrate that a robust clinical validation strategy typically involves multiple steps:

- Analytical Validation: Using reference materials and cell lines to determine the accuracy, precision, and sensitivity of the assay in detecting expression outliers and splicing defects [14] [22].

- Orthogonal Confirmation: Using an independent method (like RT-qPCR) on a subset of patient samples to verify key findings [14].

- Clinical Utility Assessment: Applying the assay to large, real-world patient cohorts to demonstrate its ability to uncover biologically and clinically relevant alterations that would have been missed otherwise [14] [21].

A critical challenge in diagnostic RNA-seq is tissue-specific gene expression. For example, one study found that even in commonly used clinically accessible tissues like blood and fibroblasts, over 37% and 48% of coding genes, respectively, can have low expression (TPM < 1), potentially limiting their assessability [22]. This underscores the need for validation studies to be performed in the specific tissue relevant to the disease or drug target.

A Technical Protocol for RT-qPCR Validation

RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for gene expression validation due to its high sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and wide adoption in clinical settings [23] [9]. The following workflow outlines the key steps for a robust validation experiment.

Selection of Reference and Target Genes

The selection of appropriate genes is the most critical step for a successful validation.

- Reference Gene Selection: Traditional housekeeping genes (e.g.,

GAPDH,ACTB) are often unstable across different biological conditions. Software tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) can systematically identify the most stable and highly expressed reference genes directly from the RNA-seq dataset itself [11]. Ideal reference genes should have low variability (standard deviation of log2(TPM) < 1), high expression (average log2(TPM) > 5), and a low coefficient of variation (< 0.2) across all samples in the study [11]. - Target Gene Selection: For validating differentially expressed genes, select candidates that represent a range of expression levels and fold-changes. The GSV tool can also identify highly variable genes suitable for validation [11]. In a colorectal cancer study, the genes

HPGD,PACS1, andTDP2were selected from RNA-seq data and successfully validated using Taqman qPCR as prognostic biomarkers in patient plasma [23].

Detailed Experimental Workflow

- RNA Extraction and QC: Use dedicated kits for your sample type (e.g., miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit for cell-free RNA [23], RNeasy kits for tissues/cells [24] [22]). Assess RNA quantity and quality using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and an instrument like the TapeStation to ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 7 [24] [22].

- Reverse Transcription: Synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) from 500 ng of total RNA using a high-quality kit like the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit, which includes primers for random hexamers and oligo(dT) to ensure comprehensive coverage [25].

- qPCR Reaction:

- Chemistry: Use either SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry. SYBR Green is more cost-effective but requires careful optimization and validation of primer specificity. TaqMan probes offer greater specificity and are preferred in clinical settings [23].

- Protocol: Perform reactions in a 20-μL volume using a master mix like PowerUp SYBR Green or TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix. Run samples in technical replicates on a real-time PCR instrument (e.g., QuantStudio 3) [25].

- Primers/Probes: Use commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays or carefully designed, validated primers [23] [25].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The standard method for analysis is the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method [23] [25]:

- Calculate ΔCt = Ct(target gene) - Ct(reference gene)

- Calculate ΔΔCt = ΔCt(test sample) - ΔCt(control sample)

- The fold change is expressed as 2^(-ΔΔCt)

Finally, use statistical tests (e.g., one-sample t-tests on log2 fold-change values against a test value of zero) to determine if the observed expression changes are significant [23]. A successful validation is demonstrated by a strong correlation between the fold-changes observed in RNA-seq and those confirmed by RT-qPCR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Validation

| Item | Function | Example Products & Kits |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from diverse sample types. | RNeasy Mini/Fibrous Tissue Kits (Qiagen) [24] [22], miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen) [23], AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [14] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Synthesize stable cDNA from RNA templates for downstream qPCR. | SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher) [25], PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara) [23] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Provide optimized buffers, enzymes, and dyes for efficient and specific amplification. | PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) [25], TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) [23] |

| Gene Expression Assays | Ensure specific detection and quantification of target transcripts. | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) [23], designed primer pairs for SYBR Green |

| Nucleic Acid QC Instruments | Accurately assess RNA concentration, purity, and integrity. | Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher) [14] [22], TapeStation System (Agilent) [14] [24], Fragment Analyzer (Agilent) [24] |

In the high-stakes fields of clinical application and drug development, assuming the absolute accuracy of a single omics technology is a significant risk. A robust framework that integrates RNA-seq discovery with RT-qPCR confirmation creates a foundation of verifiable data upon which sound biological conclusions, diagnostic tests, and therapeutic decisions can be built. By adhering to structured validation protocols, leveraging appropriate bioinformatic tools for gene selection, and utilizing trusted reagent solutions, researchers can enhance confidence in their data, ultimately accelerating the translation of genomic discoveries into tangible clinical benefits.

From Data to Validation: A Methodological Roadmap for Reliable qPCR

The emergence of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics, providing an unprecedented platform for genome-wide expression profiling without the probe-specific biases that historically limited microarray technologies [26] [9]. However, this powerful technique introduces new analytical challenges, particularly regarding the validation of findings through orthogonal methods like quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). While some researchers argue that RNA-seq's probe-independent nature eliminates the need for validation, evidence indicates that significant technical variability can occur throughout the extended RNA-seq workflow, from sample preparation through data analysis [26] [9]. This variability necessitates a rigorous approach to confirming results, especially when studies rely on the differential expression of a limited number of genes or when findings have substantial clinical or therapeutic implications.

Within this validation framework, the selection of appropriate reference genes (also termed housekeeping genes) for qPCR normalization emerges as a critical pre-analytical step that fundamentally determines the reliability and interpretability of validation results. Reference genes serve as internal controls to correct for technical variations in RNA integrity, cDNA synthesis efficiency, and enzymatic amplification [27] [28]. The fundamental assumption is that these genes maintain constant expression across all experimental conditions and tissue types. However, numerous studies have conclusively demonstrated that no single reference gene displays universal stability [29] [28]. The expression of commonly used housekeeping genes, such as β-actin (ACTB) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), can vary significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [30] [28]. Consequently, the improper selection of reference genes represents a pervasive source of inaccuracy that can compromise the validation of RNA-seq data, potentially leading to false conclusions and irreproducible findings.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for the identification and validation of stable reference genes derived directly from RNA-seq data, ensuring the reliability of downstream qPCR validation experiments. By establishing rigorous pre-validation protocols, researchers can enhance the credibility of their transcriptomic studies and strengthen the biological conclusions drawn from integrated genomic analyses.

Computational Identification of Candidate Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

The initial phase of selecting stable reference genes begins with a systematic computational analysis of RNA-seq data. This process leverages the comprehensiveness of transcriptomic datasets to identify genes with inherently stable expression patterns across the specific experimental conditions under investigation.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Before evaluating gene expression stability, raw RNA-seq data must undergo stringent quality control and processing. The standard workflow includes adapter trimming, quality filtering, and alignment of reads to a reference genome using tools such as STAR aligner [22] [14]. Following alignment, gene-level quantification is performed using tools like HTSeq or RNA-SeQC to generate raw count data or normalized expression values such as Transcripts Per Million (TPM) [20] [22]. These steps are crucial for ensuring that subsequent stability analyses are based on accurate and reliable expression measurements. Researchers should also assess RNA integrity numbers (RIN), sequence coverage depth, and alignment rates to confirm data quality before proceeding to stability analysis [22].

Selection Criteria for Candidate Genes

When identifying potential reference genes from RNA-seq data, several key characteristics should be considered:

Moderate Expression Levels: Candidates should exhibit neither extremely high nor extremely low expression, as both extremes can introduce normalization artifacts. Genes with average TPM values between 100 and 1000 often represent suitable candidates [27].

Low Inter-Sample Variation: Look for genes with consistently stable expression across all samples in the dataset, as measured by low coefficient of variation (CV) in TPM or count values.

Established Housekeeping Genes: Include traditionally used reference genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH, ribosomal proteins) for comparative analysis, while recognizing they may not be optimal in all contexts [30] [29].

Biological Function: Prefer genes involved in core cellular processes such as cytoskeletal maintenance, basic metabolism, or protein synthesis, as these are more likely to maintain stable expression [29].

Table 1: Example Candidate Reference Genes Identified from RNA-Seq Studies Across Species

| Organism | Stable Genes Identified | Unstable Genes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet Potato | IbACT, IbARF, IbCYC | IbGAP, IbRPL, IbCOX | [27] |

| Honeybee | arf1, rpL32 | α-tubulin, GAPDH, β-actin | [30] |

| Guava | PgTUB1, PgEF1a, PgEF2 | PgRBP47 | [29] |

| Human PBMCs | RPL13A, S18, SDHA | IPO8, PPIA | [31] |

| Small Ruminants | B2M, PPIB, BACH1, ACTB | RPS15, RPLP0, TBP | [28] |

Statistical Analysis for Stability Ranking

After identifying an initial set of candidate genes, researchers should employ dedicated algorithms to quantitatively assess and rank their expression stability. The following statistical tools are widely used in combination for this purpose:

GeNorm: This algorithm calculates a gene expression stability measure (M) for each candidate gene based on the average pairwise variation between all genes in the analysis. Genes with lower M values demonstrate higher stability. GeNorm also determines the optimal number of reference genes required for accurate normalization [27] [29].

NormFinder: This method employs a model-based approach to evaluate expression stability while considering both intra-group and inter-group variations, making it particularly valuable for studies involving multiple sample groups or treatments [27] [28].

BestKeeper: This algorithm utilizes pairwise correlation analysis to assess the stability of candidate genes based on the geometric mean of their Cq values, providing a complementary perspective to variance-based methods [27] [31].

ΔCt Method: This comparative approach evaluates expression stability by calculating the pairwise variability between different candidate genes, with lower variability indicating higher stability [31] [30].

RefFinder: This comprehensive tool integrates results from all the aforementioned algorithms (GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and ΔCt method) to generate a overall stability ranking, providing a robust consensus for candidate gene selection [27] [30].

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational workflow for identifying candidate reference genes from raw RNA-seq data:

Experimental Validation of Selected Reference Genes

Following the computational identification of candidate reference genes, laboratory-based validation is essential to confirm their stability under specific experimental conditions. This multi-stage process transitions from in silico predictions to empirical verification.

Primer Design and Validation

The initial wet-lab phase requires careful primer design and validation for each candidate reference gene:

Design Specifications: Primers should amplify 80-200 bp products spanning exon-exon junctions where possible to minimize genomic DNA amplification. The amplicon should have a Tm of approximately 60°C with minimal primer-dimer formation or secondary structure [29].

Validation Protocol: Each primer pair requires validation through a standard curve analysis using serial dilutions of cDNA. Key parameters include:

- Amplification Efficiency: Ideally between 90-110% [29]

- Correlation Coefficient (R²): >0.980 indicating linearity

- Specificity: Confirmed by melt curve analysis with a single peak

Documentation: Comprehensive records of primer sequences, amplification conditions, and validation parameters should be maintained in accordance with MIQE guidelines [9].

qPCR Experimental Design and Execution

The validation experiment must be carefully designed to accurately assess reference gene stability:

Sample Selection: Include representative samples spanning all experimental conditions, tissues, and time points relevant to the planned studies. Biological replicates are essential – typically at least three independent replicates per condition [26].

qPCR Protocol: Perform qPCR reactions using consistent thermal cycling conditions across all candidate genes. Include appropriate controls (no-template controls, reverse transcription controls) to identify potential contamination or amplification artifacts.

Data Collection: Record quantification cycle (Cq) values using consistent threshold settings across all plates. Manual inspection of amplification curves is recommended to identify any irregularities that might affect Cq accuracy [27] [29].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), AllPrep DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen), PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher) | High-quality RNA extraction from various sample types including cells, tissues, and FFPE samples [20] [22] [14] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module, High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates with high efficiency and reproducibility [20] [22] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix | Fluorescence-based detection of amplified DNA during qPCR cycles [31] [28] |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit (Illumina), NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries for RNA-seq analysis [20] [14] |

Stability Confirmation and Final Selection

The final validation stage involves analyzing the qPCR data to confirm the stability of candidate reference genes:

Re-analysis with Validation Algorithms: Process the experimentally derived Cq values using the same stability algorithms employed for the RNA-seq data (GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder) [27] [31]. This generates an empirical stability ranking based on actual qPCR data.

Concordance Assessment: Compare the computationally predicted stability rankings from RNA-seq data with the experimentally derived rankings from qPCR. High concordance between these datasets validates the computational approach and confirms the suitability of selected reference genes.

Validation with Target Genes: As a functional test, use the top-ranked reference genes to normalize the expression of target genes with known expression patterns. Successful reproduction of expected expression patterns confirms the utility of the selected reference genes [30] [28].

The following workflow diagram outlines the complete experimental validation process:

Implementation Guidelines for Reliable Gene Expression Studies

The successful identification and validation of stable reference genes culminates in their practical implementation for normalizing qPCR data in target gene expression studies. This section outlines evidence-based recommendations for optimal utilization of reference genes across diverse research contexts.

Determining the Optimal Number of Reference Genes

A critical consideration in reference gene implementation is determining how many are necessary for reliable normalization. The geNorm algorithm provides a systematic approach to this question by calculating the pairwise variation (Vn/Vn+1) between sequential normalization factors [27] [29]. A commonly applied threshold is V < 0.15, indicating that the inclusion of an additional reference gene does not significantly improve normalization accuracy. Most studies find that 2-3 validated reference genes are sufficient for robust normalization across diverse experimental conditions [27] [28]. Using a single reference gene is generally discouraged unless its stability has been extensively documented in the specific experimental system under investigation.

Context-Dependent Selection and Application

Reference gene stability is inherently context-dependent, necessitating careful consideration of experimental variables:

Tissue-Specific Considerations: Genes stable in one tissue type may be unsuitable for others. For example, in sweet potato, IbACT demonstrated high stability across multiple tissues, while IbCOX showed significant variability [27]. Similarly, different gene combinations were optimal for antennae, hypopharyngeal glands, and brains in honeybee studies [30].

Experimental Conditions: Environmental factors, treatments, and developmental stages profoundly influence gene stability. In hypoxic conditions, RPL13A, S18, and SDHA emerged as stable reference genes for PBMCs, while IPO8 and PPIA performed poorly [31]. Physiological adaptations in small ruminants reared at high-altitudes necessitated distinct reference gene panels (B2M, PPIB, BACH1, ACTB) compared to traditional options [28].

Species-Specific Factors: Cross-species application of reference genes requires validation. While some genes (e.g., elongation factors, ribosomal proteins) frequently demonstrate stability across taxa, empirical confirmation is essential [30] [29] [28].

Integration with RNA-Seq Validation Frameworks

The selection of stable reference genes represents a foundational element in comprehensive RNA-seq validation protocols. When determining whether qPCR validation is necessary for RNA-seq findings, researchers should consider these evidence-based guidelines:

Validation Recommended: When studies rely on a limited number of key genes for biological conclusions; when RNA-seq identifies subtle expression changes (less than 2-fold); when investigating low-abundance transcripts; or when extending findings to additional sample types not included in the original RNA-seq experiment [26] [9].

Validation Optional: When RNA-seq data are derived from multiple biological replicates (minimum of three) showing strong concordance; when studying highly abundant transcripts with large expression differences; or when conducting purely exploratory analyses without immediate functional implications [26] [9].

Recent comprehensive analyses indicate that approximately 1.8% of genes show severe non-concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR results, with these typically being lower expressed, shorter transcripts [9]. This underscores the particular importance of validation for studies focusing on such problematic genes.

The systematic approach to selecting and validating stable reference genes outlined in this technical guide provides a critical foundation for robust gene expression studies. By leveraging RNA-seq data as a starting point for identifying candidate genes, followed by rigorous experimental validation using multiple algorithmic approaches, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of qPCR-based confirmation of transcriptomic findings. This pre-validation paradigm represents a essential component of methodologically sound molecular research, ensuring that biological conclusions rest upon technically solid analytical frameworks. As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve and find new applications in both basic research and clinical diagnostics, the principles of rigorous reference gene selection will remain fundamental to generating reproducible, scientifically valid gene expression data.

The reliability of any RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) study, and by extension the justification for its validation via quantitative PCR (qPCR), rests upon a foundation of rigorous experimental design. A poorly designed RNA-Seq experiment can yield misleading results, rendering subsequent qPCR validation inefficient or scientifically questionable. This guide details the core principles of experimental design power—specifically focusing on biological replication, controls, and sample splitting—to ensure that RNA-Seq data is robust, reproducible, and worthy of downstream validation. The relationship between RNA-Seq and qPCR is not merely sequential but deeply interconnected; a well-powered RNA-Seq experiment provides the credible differential expression targets that make qPCR validation a meaningful confirmatory step [32]. Challenges such as technical biases in RNA-seq [32] and the inherent complexity of transcriptome-wide data [3] make a strategic design not just beneficial, but essential for generating actionable biological insights, particularly in critical fields like drug discovery [6].

The Cornerstone of Power: Biological Replication

Why Biological Replicates Are Non-Negotiable

In the context of RNA-Seq, a "biological replicate" is defined as an RNA sample collected from an independently processed biological unit within a treatment group. For example, cells from different animals, separately passaged cell cultures, or distinct human donors all constitute biological replicates [6] [33]. Their primary purpose is to capture the natural biological variability that exists within the population being studied, allowing researchers to distinguish consistent treatment effects from random individual variation [6] [33].

The power of a statistical test is its probability of correctly detecting a true effect, such as a genuinely differentially expressed gene. Underpowered experiments, often due to insufficient replication, are a primary cause of false negatives and irreproducible results [34]. Biological replication is the single most critical factor for improving statistical power in RNA-Seq experiments [35]. Simulations and empirical studies have consistently shown that allocating resources to increase the number of biological replicates provides a greater boost to power than increasing sequencing depth beyond a reasonable level [35]. One study found that sequencing depth could be reduced to as low as 15% in some scenarios without a substantial negative impact on false positive or true positive rates, provided sufficient biological replication was maintained [35].

Determining the Number of Biological Replicates

The choice of the number of biological replicates is a balance between statistical ideals and practical constraints. While two replicates per condition is the absolute minimum for any statistical comparison, it provides very low power and poor estimation of variability [3]. As shown in the table below, a minimum of three biological replicates is often considered a baseline, but larger numbers are strongly recommended for reliable results.

Table 1: Guidelines for Biological Replication in RNA-Seq Experiments

| Scenario | Recommended Minimum Replicates | Rationale and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| General Standard/Pilot Studies | 3-5 per condition [3] [6] | Provides a baseline for estimating variability and enables rudimentary statistical testing. |

| Experiments with High Biological Variability | 6-12 per condition [6] | Necessary for complex tissues, human patient samples, or heterogeneous cell populations to achieve sufficient power. |

| Experiments with Low Variability | 4-8 per condition [6] | Inbred animal models, cell lines, or clonal populations may require fewer replicates, but more is always beneficial. |

| For Robust Detection of Small Effect Sizes | 10+ per condition [33] | Detecting subtle expression changes requires greater power, which is directly achieved by increasing replicates. |

Control Strategies and Sample Splitting

Designing Effective Experimental Controls

Controls are the benchmark against which experimental effects are measured. A carefully considered control strategy is vital for attributing observed changes in gene expression to the experimental intervention rather than confounding factors.

- Treatment vs. Control Groups: The most fundamental design compares a treated group to an untreated control. "No treatment" controls should be handled identically to the treated samples, while "mock" controls (e.g., adding a solvent like DMSO) account for the vehicle's effects [6].

- Spike-In Controls: Synthetic RNA molecules (e.g., SIRVs) added in known quantities to each sample before library preparation are invaluable. They serve as an internal standard to monitor technical performance across the entire workflow, allowing for assessment of sensitivity, dynamic range, and quantification accuracy [6]. This is particularly crucial for large-scale studies where batch effects are a concern.

- Pilot Studies: A small-scale pilot experiment is highly recommended before committing to a full-scale study. It provides critical preliminary data on biological variability, which is essential for performing a formal sample size calculation. It also allows for validation of wet-lab and data analysis workflows [6] [33].

Sample Splitting, Randomization, and Batch Effects

How samples are assigned to processing groups and sequenced is as important as the samples themselves. Failure to properly split and randomize samples can introduce "batch effects"—systematic technical variations that are confounded with biological groups and can utterly invalidate results.

- Randomization: The assignment of samples to treatment groups, as well as the order of all downstream processes (library preparation, sequencing lane assignment), must be randomized [33]. For example, all control samples should not be processed on one day and all treated samples on another. Bench scientists must randomize the order of sample processing in the lab to avoid confounding effects with time or location (e.g., well position in a multi-well plate) [33].

- Blocking and Batch Correction: When full randomization is impossible (e.g., due to large sample numbers), a blocked design should be used. This involves distributing samples from all experimental groups evenly across processing batches (e.g., different sequencing lanes or days). This design allows for statistical methods to later "correct" for the technical batch effect during data analysis [6].

- Sample Splitting Diagram: The following workflow visualizes the key steps for properly splitting and processing samples to minimize bias.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Experimental Design

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit (e.g., RNeasy, AllPrep) [32] [22] | Isolation of high-quality RNA from cells or tissues. | The choice of kit depends on sample type (e.g., FFPE, blood, cells) and whether concurrent DNA extraction is needed. Consistent use is critical. |

| Spike-In RNA Controls (e.g., SIRVs, ERCC) [6] | Exogenous RNA transcripts added to each sample. | Provides an internal standard for normalizing technical variation and assessing assay performance across batches and runs. |

| Stranded mRNA/Total RNA Library Prep Kit [14] [22] | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready library. | Selection depends on RNA integrity (e.g., FFPE vs. fresh frozen), need for ribosomal RNA depletion, and the RNA species of interest (e.g., mRNA vs. non-coding). |

| Quality Control Instruments (Qubit, TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) [14] [22] | Quantifies and assesses the integrity of nucleic acids. | Essential quality gates before proceeding to costly library preparation; ensures input material is of sufficient quality and quantity. |

| Statistical Power Analysis Software (e.g., Scotty, pwr) [3] [35] | Calculates necessary sample size prior to the experiment. | Uses pilot data or estimates of effect size and variability to determine the number of biological replicates needed to avoid underpowered studies. |

Connecting Experimental Design to qPCR Validation

The ultimate test of RNA-Seq data quality is often its concordance with an orthogonal, sensitive method like qPCR. The correlation between RNA-Seq and qPCR expression estimates is not always perfect, with studies reporting moderate correlations (e.g., Spearman's rho between 0.2 and 0.53 for HLA genes) [32]. This highlights that technical differences between the platforms can influence results.

A powerful and well-controlled RNA-Seq design directly addresses these challenges and strengthens the validation phase in several ways:

- Identifying True Positives: By adequately powering the study with biological replicates, the list of differentially expressed genes sent for qPCR validation is enriched with true biological effects, rather than technical artifacts or false discoveries.

- Providing a Biological Context: The replication and blocking design that captures biological variability ensures that the expression changes measured by qPCR are representative of the population, not just idiosyncratic to a single sample.

- Informing qPCR Design: The RNA extraction methods, sample types, and biological conditions optimized for the RNA-Seq study can be directly mirrored in the qPCR validation, ensuring a fair and meaningful comparison between the two platforms.

In conclusion, a rigorous focus on biological replication, strategic controls, and unbiased sample splitting is not merely a preliminary step but the very foundation upon which credible RNA-Seq results are built. This robust foundation is what makes the subsequent investment in qPCR validation a scientifically justified and valuable endeavor, ultimately leading to more reliable and translatable biological conclusions.

In the modern genomics landscape, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has become the cornerstone technology for comprehensive gene expression profiling. However, the journey from raw biological sample to robust, interpretable data begins long before sequencing commences. The initial wet lab phase—encompassing RNA extraction, handling, and quality control (QC)—is a critical determinant of success for all downstream applications, from discovery-phase RNA-Seq to targeted validation using quantitative PCR (qPCR). This foundational stage establishes the integrity of the transcriptional snapshot, ensuring that the resulting data accurately reflects the biological state under investigation.

The imperative for rigorous QC is further amplified when research aims to bridge high-throughput discovery with focused validation. Within the context of a broader thesis on validating RNA-Seq with qPCR, the reliability of the initial RNA sample is the common thread that unites these techniques. High-quality RNA extracted with precision provides a solid substrate not only for a successful RNA-Seq library but also for the subsequent qPCR assays that will confirm key findings. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core principles and practices for navigating the wet lab workflow from RNA extraction to quality assessment, providing researchers with the knowledge to generate data that is both technically sound and biologically meaningful.

RNA Quality Metrics: RIN and DV200

The assessment of RNA integrity is a non-negotiable first step in any transcriptomic study. Two primary metrics, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and the DV200 value, are routinely used to quantify RNA quality, each with distinct strengths and optimal applications.

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is an algorithm-assigned score ranging from 1 (completely degraded) to 10 (perfectly intact). It is generated by an Agilent Bioanalyzer system and evaluates the entire electrophoretic trace of an RNA sample, including the presence and ratios of ribosomal RNA peaks. Traditionally, a RIN value greater than 7.0 is considered suitable for standard RNA-Seq workflows [36].

The DV200 metric represents the percentage of RNA fragments that are longer than 200 nucleotides. This metric has gained prominence, particularly for partially degraded samples, such as those derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues or post-mortem sources, because it focuses on the size distribution of fragments that are actually usable in library construction [36] [37]. Recent research highlights DV200 as a more accurate predictor of successful RNA-seq outcomes in degraded or post-mortem samples compared to RIN [36].

The table below summarizes the typical quality thresholds for different downstream applications:

Table 1: RNA Quality Thresholds for Downstream Applications

| Application | Recommended RNA Input | Recommended Quality Metric | Minimum Threshold | Ideal Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stranded mRNA Seq | ≥800 ng total [38] | RIN [38] | RIN > 5.5 [38] | RIN > 7.0 [38] |

| Total RNA Seq | ≥500 ng total [38] | RIN [38] | RIN > 3.5 [38] | Not Specified |

| Transcriptome Capture(e.g., for FFPE/low-quality RNA) | ≥1 µg total [38] | DV200 [38] | DV200 > 30% [38] | Higher DV200 values correlate with greater sequencing output [36] |

A comparative study on post-mortem human liver tissue demonstrated that samples with a mean DV200 of 63.81% and a mean RIN of 7.14—harvested within 10 hours post-mortem—were consistently suitable for next-generation RNA sequencing [36]. Furthermore, the study found a significant positive correlation between higher DV200 values (70-80%) and the total number of bases sequenced, highlighting its utility as a predictive metric for sequencing efficiency [36].

RNA Extraction and QC: Detailed Experimental Protocols

RNA Extraction Methodologies

A robust RNA extraction protocol is fundamental. The methodology must be tailored to the sample type (e.g., fresh tissue, blood, FFPE). Below is a generalized protocol, with notes on adaptations.

Protocol: Guanidinium-Thiocyanate Phenol-Chloroform Extraction (e.g., TRIzol)

This method is effective for a wide variety of sample types, including cells and tissues, due to its ability to rapidly inactivate RNases.

- Homogenization: Homogenize 50-100 mg of tissue or cell pellet in 1 mL of TRIzol reagent. Use a mechanical homogenizer for tough tissues. For liquid samples like plasma, a dedicated kit like the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit is more appropriate [23].

- Phase Separation: Incubate the homogenate for 5 minutes at room temperature to dissociate nucleoprotein complexes. Add 0.2 mL of chloroform per 1 mL of TRIzol used. Cap the tube securely, shake vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate at room temperature for 2-3 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The solution will separate into three phases: a red organic phase (phenol-chloroform), an interphase (DNA), and a colorless upper aqueous phase (RNA).

- RNA Precipitation: Carefully transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube without disturbing the interphase. Precipitate the RNA by mixing with 0.5 mL of isopropyl alcohol per 1 mL of TRIzol used. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- RNA Pellet: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The RNA will form a gel-like pellet on the side and bottom of the tube.

- Wash: Carefully remove the supernatant. Wash the RNA pellet with 1 mL of 75% ethanol (in RNase-free water) per 1 mL of TRIzol used. Vortex briefly and centrifuge at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Redissolution: Air-dry the pellet briefly for 5-10 minutes (do not let it dry completely, as this reduces solubility). Dissolve the RNA in 20-50 µL of RNase-free water.

Quality Control Assessment Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing RNA quality post-extraction, leading to the decision on its suitability for downstream applications.

Determining DV200 Values

The DV200 value is calculated using automated electrophoresis systems from Agilent Technologies. The general procedure is as follows [37]:

Protocol: DV200 Determination on Agilent Systems

- System Setup: Use either the 2100 Bioanalyzer system (with 2100 Expert software), TapeStation systems (with TapeStation Analysis software), or the Fragment Analyzer systems (with ProSize data analysis software).

- Load and Run Sample: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the specific RNA assay (e.g., RNA Nano, RNA Pico) to load the RNA sample and run the analysis.

- Apply DV200 Calculation:

- For Bioanalyzer: Import the appropriate DV200 assay file (.xsy) into the software to apply the calculation to your data file. The DV200 value will be displayed in the results [37].

- For TapeStation: In the "Regions" settings, define a new region with a lower limit of 200 nucleotides and an upper limit (e.g., 10,000 nt). Name the region "DV200". The value is provided as a percentage of the total signal in this region [37].