Sanger Sequencing for NGS Validation: A Definitive Guide to Accurate SNP Confirmation in Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) calls from Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data using Sanger sequencing.

Sanger Sequencing for NGS Validation: A Definitive Guide to Accurate SNP Confirmation in Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) calls from Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data using Sanger sequencing. It covers the foundational principles establishing Sanger sequencing as the gold standard, detailed methodological workflows for orthogonal verification, practical troubleshooting for common technical challenges, and a critical evaluation of validation needs in the era of high-accuracy NGS. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to empower scientists to design robust validation strategies that ensure data integrity for critical applications in clinical diagnostics, pharmacogenomics, and biomedical research.

Why Sanger Sequencing Remains the Gold Standard for NGS Validation

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genetics, but the raw data it produces is not perfect. Accurate single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling relies on understanding the distinct types of errors introduced at various stages of the NGS workflow and how they confound the separation of true genetic variation from technical artifacts. This guide examines the sources and implications of these errors, providing a structured comparison of how different bioinformatics strategies and validation techniques perform in practice.

The journey from sample to SNP call is a multi-step process, and each step introduces specific biases and errors. Understanding this workflow is foundational to diagnosing issues in downstream analysis.

From Sample to Sequence: A Multi-Step Process

The transformation of a biological sample into analyzable sequence data involves a coordinated series of wet-lab and computational steps, each with its own error profile [1] [2]. The major stages are:

- Sample Preparation: DNA is fragmented, and platform-specific adapters are ligated. DNA damage during sample handling, such as oxidation or deamination, can introduce artifactual variants, particularly C>A/G>T substitutions [2].

- Library Preparation: This stage often involves PCR amplification. Polymerase errors during this enrichment PCR can introduce substitutions and indels, with one study noting it led to a ~6-fold increase in the overall error rate [2].

- Sequencing-by-Synthesis: This is the core of NGS, where fluorescently-tagged nucleotides are incorporated and imaged. Errors arise from issues like phasing (desynchronization of the synthesis process) in Illumina platforms or homopolymer length miscalculation in 454 sequencing [1].

- Base Calling & Alignment: Computational algorithms interpret fluorescence images into nucleotide sequences (base calling) and map short reads to a reference genome. Misalignments, especially around indels or highly polymorphic regions, are a major source of error [1].

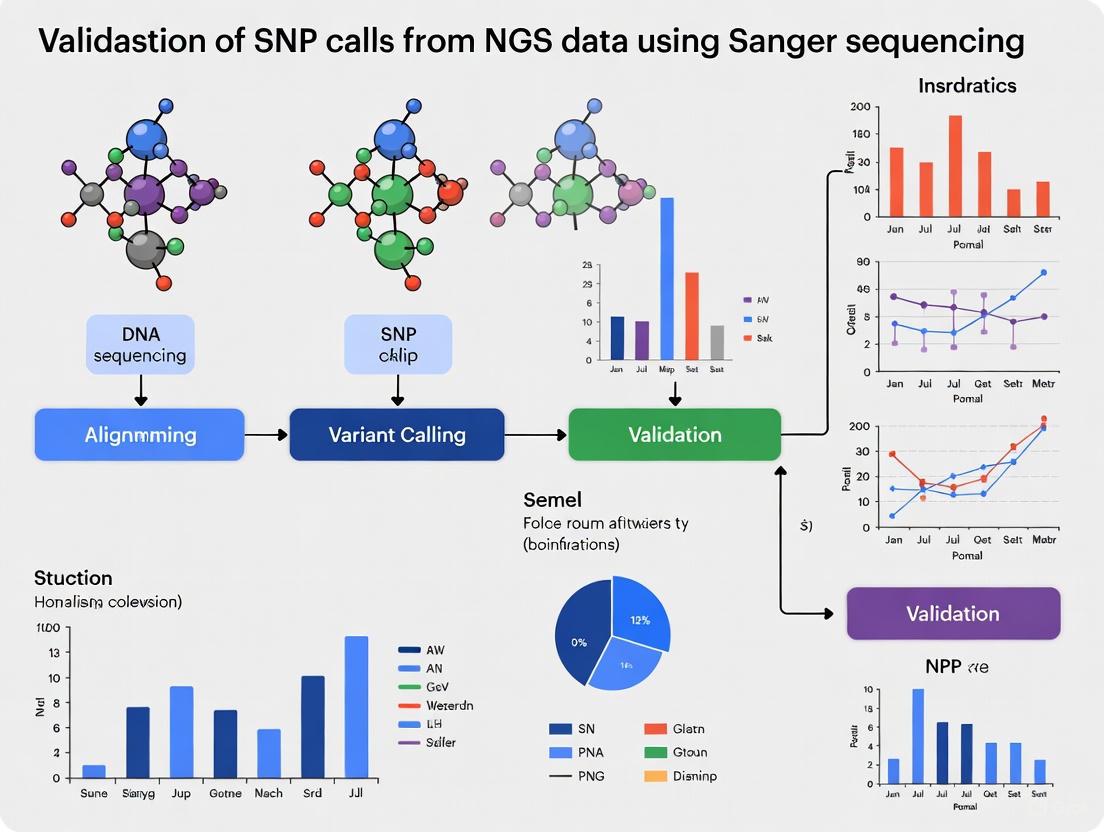

The following diagram illustrates this workflow and its primary error sources:

Quantifying Substitution Error Profiles

Not all sequencing errors are equally likely. Different chemical and enzymatic processes create distinct signatures. A comprehensive analysis of deep sequencing data revealed that error rates differ significantly by nucleotide substitution type [2]. Some errors are more common and can be mistaken for true variants, especially in low-frequency variant detection.

Table 1: Substitution Error Rates by Type in Conventional NGS

| Substitution Type | Reported Error Rate | Primary Contributing Factor |

|---|---|---|

| A>G / T>C | ~10-4 | Sequencing process itself [2] |

| C>T / G>A | ~10-5 to ~10-4 | Spontaneous cytosine deamination; strong sequence-context dependency [2] |

| A>C / T>G, C>A / G>T, C>G / G>C | ~10-5 | Sample-specific effects (e.g., oxidative damage) dominate C>A/G>T errors [2] |

Experimental Data: Benchmarking Variant Calling Pipelines

Choosing and optimizing a bioinformatics pipeline is critical for accurate SNP calling. Comparative studies have systematically evaluated the performance of different tools and procedures against gold-standard data.

GATK vs. SAMtools: A Head-to-Head Comparison

A critical validation study compared two widely used variant callers—GATK and SAMtools—using Sanger sequencing of 700 variants as a gold standard [3]. The study employed a unified pipeline for 130 whole exome samples, encompassing mapping with BWA, duplicate marking, local realignment, and base quality score recalibration (BQSR).

Experimental Protocol:

- Mapping: BWA (v0.7.0) was used to align reads to the reference genome (hg19).

- Post-Alignment Processing: Duplicate fragments were marked with Picard, and low-quality mapped reads were filtered.

- Recalibration & Realignment: GATK's Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR) and local realignment were performed.

- Variant Calling: SNVs were called using both GATK UnifiedGenotyper (v2.6) and SAMtools mpileup (v0.1.18).

- Validation: A random selection of variants was validated via Sanger sequencing on an ABI capillary platform.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GATK vs. SAMtools

| Metric | GATK | SAMtools |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 92.55% [3] | 80.35% [3] |

| True-Positive Rate (from Sanger validation) | 95.00% [3] | 69.89% [3] |

| Impact of Realignment/Recalibration | Positive Predictive Value of calls unique to the pipeline with realignment/recalibration was 88.69%, versus 35.25% for the pipeline without [3]. |

Establishing Quality Thresholds for High-Confidence Variants

To reduce the burden of Sanger validation, researchers have sought to define quality thresholds that distinguish high-confidence variants. A 2025 study analyzed 1,756 WGS variants from 1,150 patients, each validated by Sanger sequencing, to establish such thresholds [4]. The mean coverage of the samples was 34.1x, and variants had a mean quality (QUAL) score of 492.

Key Findings:

- Caller-Agnostic Thresholds: Using parameters like depth of coverage (DP) and allele frequency (AF), the study found that variants with DP ≥ 15 and AF ≥ 0.25 achieved 100% concordance with Sanger data in their dataset. Applying these thresholds would have reduced the number of variants requiring validation to only 4.8% of the initial set [4].

- Caller-Specific Thresholds: Using GATK HaplotypeCaller's QUAL score alone, a threshold of QUAL ≥ 100 also achieved 100% concordance, drastically reducing the validation set to 1.2% of the original calls [4].

Sanger Sequencing as a Validation Tool: Utility and Limits

Sanger sequencing has long been the "gold standard" for validating NGS-derived variants. However, as NGS technology has matured, the necessity of this costly and time-consuming step is being re-evaluated.

High Concordance Challenges Routine Validation

Large-scale studies have demonstrated exceedingly high concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing. One major study from the ClinSeq project compared over 5,800 NGS-derived variants across five genes in 684 participants against high-throughput Sanger data [5]. The results challenge the need for universal validation.

Experimental Protocol:

- NGS: Solution-hybridization exome capture was performed using Agilent SureSelect or Illumina TruSeq kits. Sequencing was on Illumina GAIIx or HiSeq 2000. Reads were aligned with NovoAlign, and variants were called with the Most Probable Genotype (MPG) caller.

- Sanger Sequencing: A large set of 308 genes was sequenced using 16,371 primer pairs in an automated pipeline (PrimerTile). Genotypes were verified by manual observation of fluorescence peaks in Consed.

- Discrepancy Resolution: Variants not validated by initial Sanger data were re-tested with newly designed primers.

Results: Of the 5,800+ NGS variants, only 19 were not initially validated by Sanger. Upon re-sequencing with optimized primers, 17 of these were confirmed as true positives, while the remaining two had low-quality scores from exome sequencing. This resulted in a final validation rate of 99.965% for NGS variants [5]. The study concluded that a single round of Sanger sequencing is more likely to incorrectly refute a true positive NGS variant than to correctly identify a false positive.

Decision Framework: When is Sanger Validation Necessary?

The collective evidence supports a more nuanced approach to Sanger validation, moving away from a universal requirement. The following decision pathway can help laboratories optimize their validation strategy:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Tools for Robust SNP Calling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Role in Error Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Materials | Well-characterized human genomic DNA samples (e.g., RM 8398) with high-confidence "truth set" variants from multiple technologies [6]. | Provides a benchmark for evaluating the accuracy (sensitivity, precision) of any sequencing assay or bioinformatics pipeline. |

| Base Caller (e.g., Ibis, BayesCall) | Software that converts raw fluorescence images from the sequencer into nucleotide sequences and quality scores [1]. | Improved base-calling algorithms can reduce error rates by 5-30% compared to manufacturer's software, directly lowering false-positive SNPs [1]. |

| Aligners (e.g., BWA, Stampy) | Maps short sequencing reads to a reference genome. BWA is BWT-based and fast; Stampy is hash-based and more sensitive to variation [1]. | Accurate alignment is crucial. Misaligned reads, especially around indels, create false-positive variant calls. More sensitive aligners help in diverse regions [1]. |

| Variant Caller (e.g., GATK HaplotypeCaller) | A statistical model that differentiates true genetic variants from sequencing errors using genotype likelihoods and prior probabilities [1] [3]. | The core software for SNP calling. Advanced callers use local re-assembly (haplotyping) and model sequencing errors to quantify and minimize calling uncertainty [3]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines (e.g., GATK Best Practices) | A standardized workflow including steps like Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR) and indel realignment [3]. | BQSR corrects for systematic inaccuracies in per-base quality scores; local realignment corrects misalignments around indels. These steps are crucial for accurate calling [3]. |

In the era of next-generation sequencing (NGS), the validation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) remains a critical step in genetic analysis. Within this context, Sanger sequencing maintains its indispensable role as the gold standard for verification, providing a level of accuracy that NGS approaches have not yet surpassed for confirmatory testing. This guide objectively compares the performance of Sanger sequencing against NGS alternatives, focusing on their respective error rates and applications in validating SNP calls, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data necessary to inform their genomic validation strategies.

Historical Context and Technical Evolution

Developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977, Sanger sequencing method revolutionized molecular biology by introducing the chain-termination principle, earning Sanger his second Nobel Prize [7] [8]. For approximately 40 years, this technology served as the primary workhorse for DNA sequencing, playing a central role in milestone projects like the Human Genome Project [8].

The method relies on the random incorporation of dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) during in vitro DNA replication. These chain-terminating nucleotides lack a 3'-OH group, preventing further elongation and producing DNA fragments of varying lengths that can be separated by capillary electrophoresis [7] [9]. The introduction of fluorescent labeling and capillary array electrophoresis transformed Sanger sequencing into an automated, high-throughput process while maintaining its exceptional accuracy [7] [8].

Despite the rise of NGS technologies that offer massively parallel sequencing, Sanger sequencing maintains a vital position in modern genomics laboratories, particularly for targeted confirmation of genetic variants [9] [10]. Its resilience in the genomic toolkit stems from technical advantages that remain relevant decades after its development.

Quantitative Comparison of Sequencing Accuracy

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for Sanger sequencing and NGS, highlighting the complementary strengths of each technology:

| Performance Metric | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Error Rate | 0.001% (approximately 1 error in 100,000 bases) [11] [12] | ~0.1–15% raw error rate (platform-dependent) [11] |

| Per-Base Accuracy | 99.99% (Phred score Q40) to 99.999% [7] [9] [13] | Varies by platform; typically lower than Sanger for single reads [13] |

| Variant Detection Limit | ~15-20% allele frequency [14] [10] | As low as 1-5% allele frequency with sufficient coverage [9] [10] |

| Typical Read Length | 500-1000 bp [7] [9] [15] | 50-300 bp (short-read platforms) [9] |

| Primary Error Type | Minimal when optimized [8] | Substitution errors, platform-specific patterns [13] |

This quantitative comparison reveals a fundamental distinction: while NGS provides superior sensitivity for low-frequency variants due to its deep sequencing capability, Sanger sequencing offers superior per-base accuracy for confirming variants once discovered [9] [10].

Experimental Evidence: Sanger Sequencing for SNP Validation

Case Studies in Clinical Genomics

A 2020 study addressing validation of NGS variants provides compelling evidence for Sanger's ongoing role. Researchers performed Sanger validation on 945 rare genetic variants initially identified by NGS in a cohort of 218 patients [12]. While the majority of "high quality" NGS variants were confirmed, three cases showed discrepancies between NGS and initial Sanger results [12].

Upon deeper investigation, these discrepancies were attributed not to NGS errors but to limitations of the Sanger process itself, including allelic dropout (ADO) during polymerase chain reaction or sequencing reactions, often related to incorrect variant zygosity calling [12]. This study highlights that while Sanger sequencing remains the validation gold standard, it is not entirely error-free, and discrepancies require careful methodological investigation.

HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutation Detection

A 2024 study compared Sanger sequencing with two NGS systems (homemade amplicon-based and AD4SEQ kit) for identifying HIV-1 drug resistance mutations. Both NGS systems identified additional low-frequency mutations below Sanger's detection threshold, demonstrating NGS's superior sensitivity [14].

However, researchers noted instances where mutations detected by Sanger were missed by one NGS system, and these discrepancies occasionally led to differences in drug susceptibility interpretation, particularly for NNRTIs [14]. This illustrates the critical balance between sensitivity (NGS) and reliability (Sanger) in clinical contexts where treatment decisions depend on accurate variant detection.

Experimental Protocols for SNP Validation

Standard Sanger Sequencing Protocol for NGS Validation

For researchers validating NGS-derived SNPs, the following protocol provides a robust methodological framework:

Primer Design: Design oligonucleotide primers flanking the SNP of interest using tools like Primer3 [12]. Amplicon size should be optimized for Sanger sequencing (typically 500-800 bp).

PCR Amplification: Amplify the target region from 50-100 ng of genomic DNA using high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize PCR errors [14]. Include positive and negative controls.

PCR Product Purification: Treat amplification products with enzymatic cleanup mixtures (e.g., ExoSAP-IT) to remove excess primers and dNTPs that could interfere with sequencing [12] [14].

Sequencing Reaction: Prepare sequencing reactions using fluorescent dye-terminator chemistry (e.g., BigDye Terminator kits). Standard reaction conditions include:

Thermal Cycling: 25 cycles of: 50°C for 1 min, 68°C for 4 min, and 94°C for 1 min [14].

Post-Reaction Purification: Remove unincorporated dye terminators using purification systems (e.g., X-Terminator kit) [12].

Capillary Electrophoresis: Analyze purified reactions on automated genetic analyzers (e.g., Applied Biosystems 3500xL) [12] [14].

Data Analysis: Compare sequence chromatograms with reference sequences using specialized software. Manually inspect SNP positions for clear, unambiguous peaks and appropriate background signal [7].

NGS Validation Protocol for Comparative Studies

For laboratories conducting formal comparisons between NGS and Sanger:

Library Preparation: Use target enrichment approaches (e.g., Haloplex/SureSelect) for specific gene panels [12].

Sequencing: Perform on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq with minimum 30× coverage depth [12].

Variant Calling: Implement standardized pipelines (e.g., BWA-MEM for alignment, GATK HaplotypeCaller for variant calling) with quality filters (Phred score ≥30) [12].

Variant Selection for Validation: Prioritize variants based on quality metrics, including allele balance >0.2 and MAF <0.01 [12].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for validating NGS-derived variants using Sanger sequencing:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents required for Sanger sequencing validation workflows and their specific functions in the experimental process:

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Validation Protocol |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification of target regions with minimal introduction of errors during amplification [8]. |

| BigDye Terminator Kit | Fluorescently labeled ddNTPs for cycle sequencing reactions; provides chain termination with fluorescent detection [12] [14]. |

| ExoSAP-IT / Purification Kits | Enzymatic cleanup of PCR products; removes excess primers and dNTPs that interfere with sequencing reactions [12]. |

| X-Terminator Purification Kit | Post-sequencing reaction cleanup; removes unincorporated dye terminators before capillary electrophoresis [12]. |

| Capillary Array Electrophoresis | Automated size-based separation of DNA fragments with fluorescence detection; core technology of modern Sanger sequencers [7] [8]. |

Technical Innovations and Future Directions

Sanger sequencing continues to evolve through technical improvements. Recent innovations include:

- Microfluidic Sanger sequencing: Integrates thermal cycling, sample purification, and capillary electrophoresis on a wafer-scale chip using nanoliter-scale volumes, reducing reagent consumption and increasing throughput [7] [8].

- Enhanced detection systems: New optical systems with single-photon detectors and AI algorithms improve signal detection and base calling accuracy [8].

- Process automation: Integration and automation of sample processing, reaction setup, and analysis reduce human error and improve reproducibility [8].

These advancements ensure Sanger sequencing maintains its relevance by addressing limitations in cost, throughput, and efficiency while preserving its foundational advantage in accuracy.

Sanger sequencing's unmatched accuracy, demonstrated by its 99.99% base-calling precision and 0.001% theoretical error rate, secures its ongoing role as the gold standard for validating SNP calls from NGS data [11] [7] [9]. While NGS provides unparalleled throughput and sensitivity for variant discovery, the technologies maintain a complementary relationship in modern genomic workflows [9] [10].

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise error profiles, detection limitations, and appropriate applications of each technology is essential for designing robust validation pipelines. Sanger sequencing remains indispensable for confirming clinically relevant mutations, verifying gene editing outcomes, and validating NGS-derived variants where the highest confidence in sequence accuracy is required [12] [14] [8].

Orthogonal confirmation is a fundamental principle in scientific research and clinical diagnostics, referring to the use of an independent methodology to verify results obtained from a primary method. In the context of genetic analysis, this typically involves confirming next-generation sequencing (NGS) variant calls with an alternative technology such as Sanger sequencing. The practice is mandated by guidelines from organizations like the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG), which recommend orthogonal or companion technologies to ensure variant call accuracy [16]. While NGS technologies have revolutionized genetic medicine by enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions of DNA fragments, they remain susceptible to platform-specific errors, including base-calling inaccuracies, amplification artifacts, and mapping errors in complex genomic regions [16] [17].

The necessity for orthogonal confirmation must be balanced against the dramatically improved accuracy of modern NGS platforms and bioinformatics pipelines. Recent large-scale studies have demonstrated exceptionally high concordance rates (exceeding 99.9%) between NGS and Sanger sequencing for single nucleotide variants (SNVs), challenging the notion that universal orthogonal confirmation remains necessary [5] [18]. This evolving landscape necessitates a nuanced approach to orthogonal confirmation that considers application-specific requirements, variant type, and genomic context. This review examines the key scenarios where orthogonal confirmation provides maximum value across clinical diagnostics, pharmacogenomics, and basic research, with a specific focus on validating SNP calls from NGS data.

Orthogonal Confirmation Methodologies and Performance

Established and Emerging Confirmation Technologies

Orthogonal validation employs methodologies with fundamentally different principles than the primary detection method. The following technologies are commonly used for confirming NGS-derived variants:

- Sanger Sequencing: Traditionally considered the gold standard for confirming variants identified by NGS, this method provides high accuracy for targeted regions but is low-throughput and labor-intensive [5] [8].

- Orthogonal NGS Platforms: Using a different NGS platform with complementary chemistry and target capture methods (e.g., Illumina reversible terminator sequencing combined with Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing) provides confirmation at genomic scale [16].

- Microarray Technologies: SNP microarrays offer a cost-effective solution for verifying known variants, though they are limited to predefined positions and less effective for novel variants [19].

- CRISPR-Based Modulation: In functional research, technologies like CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) can orthogonally validate gene function without introducing double-strand breaks [20].

- Non-Sequencing Methods: Techniques including RNA sequencing, in situ hybridization, and mass spectrometry can provide protein-level or expression-based confirmation of NGS findings [21].

Performance Comparison of Validation Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different orthogonal confirmation approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Orthogonal Confirmation Methods

| Method | Throughput | Cost Efficiency | Best Application Context | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Low (single fragments) | High for few targets, poor for many | Clinical reporting of limited variants; validation of critical findings | Low throughput; does not scale for genome-wide studies [16] |

| Orthogonal NGS Platforms | High (genomic scale) | Moderate to high | Research validation; clinical exome confirmation | Higher cost than single-platform; computational complexity [16] |

| SNP Microarrays | Medium to High | High for known variants | Kinship testing; pharmacogenomic panels | Limited to predefined variants; poor for novel discoveries [19] |

| Machine Learning Triaging | High (computational) | Very high after validation | Reducing confirmation burden for high-confidence SNVs | Requires extensive training and validation; limited for indels/complex variants [18] |

Key Application Scenarios for Orthogonal Confirmation

Clinical Diagnostic Applications

In clinical diagnostics, where results directly impact patient management, orthogonal confirmation plays a crucial role in ensuring result accuracy. The dual-platform NGS approach exemplifies this strategy, combining bait-based hybridization capture (e.g., Agilent SureSelect) with Illumina sequencing alongside amplification-based capture (e.g., AmpliSeq) with Ion Torrent sequencing [16]. This methodology achieves orthogonal confirmation of approximately 95% of exome variants while simultaneously improving overall variant sensitivity, as each method covers thousands of coding exons missed by the other [16].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Orthogonal NGS in Clinical Diagnostics

| Metric | Illumina NextSeq Alone | Ion Torrent Proton Alone | Orthogonal Combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNV Sensitivity | 99.6% | 96.9% | 99.88% |

| Indel Sensitivity | 95.0% | 51.0% | Not specified |

| Positive Predictive Value (SNVs) | ~99.9% | ~99.9% | ~99.9% |

| Exome Coverage | 4.7% exons covered only by this method | 3.7% exons covered only by this method | ~95% of exome variants orthogonally confirmed |

The clinical implementation of orthogonal confirmation must consider the specific variant type and genomic context. Studies demonstrate that SNVs in high-complexity regions with high-quality metrics show concordance rates exceeding 99.9% with Sanger sequencing, suggesting limited utility for routine confirmation in these cases [5] [18]. Conversely, insertion-deletion variants (indels), variants in low-complexity regions, and those with borderline quality metrics benefit substantially from orthogonal verification [16] [18].

Pharmacogenomic Testing Applications

Pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing represents a specialized application where orthogonal confirmation strategies must balance comprehensive genotyping with practical clinical implementation. PGx testing analyzes genetic variants that influence drug metabolism, transport, and targets to guide medication selection and dosing [22] [23]. The clinical implications of these results necessitate high accuracy, particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows or severe adverse event profiles.

Current PGx implementation utilizes multiple technologies depending on the clinical scenario:

- NGS-based Panels: Utilize both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (PacBio) sequencing for comprehensive variant detection across multiple pharmacogenes [22].

- qPCR and Targeted Approaches: Provide rapid, cost-effective confirmation for specific high-priority variants (e.g., CYP2C19*2 for clopidogrel response) [22].

- Microarray Technologies: Offer an efficient solution for profiling known pharmacogenomic variants across multiple gene-drug pairs [23].

The turnaround time requirements for PGx testing vary from 3-5 days for urgent applications (e.g., fluorouracil toxicity testing) to several weeks for more comprehensive panels, reflecting the different confirmation strategies employed [22]. For clinical PGx testing, orthogonal confirmation is particularly valuable for variants with established dosing guidelines from organizations like the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) [23].

Research Applications

In basic and translational research, orthogonal validation extends beyond sequence confirmation to include functional validation of findings. The principles remain similar—using independent methods to verify results—but the applications are more diverse:

- Genome Editing Verification: Sanger sequencing serves as the gold standard for confirming CRISPR-Cas9 editing outcomes, accurately detecting successful edits and characterizing the specific mutation types (insertions, deletions, or point mutations) [8].

- Functional Genomics: In loss-of-function screens, researchers may use multiple independent technologies (e.g., CRISPR knockout, RNA interference, and CRISPRi) to verify gene-phenotype relationships, reducing the likelihood that observed effects result from technical artifacts [20].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomic findings with transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomic data provides biological validation of mechanisms [21].

A representative example from cancer research utilized both shRNA and CRISPR knockout screens to identify genes essential for β-catenin-active cancers, followed by proteomic profiling and genetic interaction mapping to orthogonally validate candidates [20]. This approach identified new regulators that would have been lower-confidence hits with a single methodology.

Experimental Protocols for Orthogonal Confirmation

Dual-Platform NGS Confirmation Protocol

The orthogonal NGS approach for clinical exome sequencing employs these key methodological steps:

- Sample Preparation: DNA is extracted from patient samples (blood or saliva) using automated systems (e.g., Autogen FlexStar or QiaCube) [16].

- Parallel Library Preparation:

- Platform A: DNA is targeted using bait-based hybridization capture (Agilent Clinical Research Exome kit) and prepared for sequencing on Illumina platforms (MiSeq or NextSeq) [16].

- Platform B: DNA is targeted using amplification-based capture (Life Technologies AmpliSeq Exome kit) and prepared for sequencing on Ion Torrent platforms (Proton sequencer) [16].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Variant Integration: A custom algorithm compares variants across platforms, grouping them into classes based on attributes including variant type, zygosity concordance, and coverage quality [16].

This protocol yields thousands of orthogonally confirmed variants while simultaneously expanding the covered exome space through the complementary strengths of each platform.

Machine Learning-Based Triaging Protocol

Emerging approaches use machine learning to reduce orthogonal confirmation burden while maintaining accuracy:

- Training Data Curation: Variant calls from GIAB reference samples with established truth sets provide labeled training data [18].

- Feature Selection: The model incorporates quality metrics including allele frequency, read depth, mapping quality, sequence context, and homopolymer proximity [18].

- Model Training: Multiple algorithms (logistic regression, random forest, gradient boosting) are trained to classify variants as high or low-confidence [18].

- Pipeline Implementation: A two-tiered confirmation bypass system with guardrail metrics allows high-confidence variants to bypass orthogonal confirmation while flagging lower-confidence variants for additional verification [18].

This approach achieved 99.9% precision and 98% specificity in identifying true positive heterozygous SNVs, dramatically reducing confirmation requirements while maintaining accuracy [18].

Visualization of Orthogonal Confirmation Workflows

Decision Framework for Orthogonal Confirmation

The following diagram illustrates a strategic approach to determining when orthogonal confirmation provides maximum value:

Diagram 1: Orthogonal Confirmation Decision Framework

Dual-Platform NGS Confirmation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for dual-platform orthogonal confirmation:

Diagram 2: Dual-Platform NGS Confirmation Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing orthogonal confirmation protocols:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal Confirmation

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome | Hybridization-based target capture | Clinical exome sequencing on Illumina platforms [16] |

| Ion AmpliSeq Exome Kit | Amplification-based target capture | Exome sequencing on Ion Torrent platforms [16] |

| Kapa HyperPlus Library Prep Reagents | Enzymatic fragmentation and library preparation | Whole exome library construction [18] |

| Twist Biotinylated DNA Probes | Target capture for exome sequencing | Custom panel hybridization and enrichment [18] |

| Genome in a Bottle Reference Materials | Benchmarking and validation | Training machine learning models; establishing performance metrics [18] |

| CRISPRmod Reagents (CRISPRi/a) | Gene modulation without double-strand breaks | Functional orthogonal validation [20] |

Orthogonal confirmation remains an essential component of rigorous genomic analysis, but its application requires careful consideration of the specific scientific or clinical context. In clinical diagnostics, dual-platform NGS approaches provide the most comprehensive confirmation while simultaneously expanding variant detection sensitivity. For pharmacogenomic applications, targeted confirmation of clinically actionable variants balances accuracy with practical implementation. In research settings, orthogonal validation extends beyond sequence confirmation to include functional verification using complementary technologies.

The evolving landscape of NGS technologies and computational methods is reshaping orthogonal confirmation practices. Machine learning approaches now enable strategic triaging of variants, reserving costly confirmation for those with borderline quality metrics or in challenging genomic regions. As NGS platforms continue to improve in accuracy and bioinformatic methods become more sophisticated, the paradigm is shifting from universal orthogonal confirmation to risk-based approaches that maintain the highest standards of accuracy while optimizing resource utilization across clinical, pharmacogenomic, and research applications.

The adoption of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in clinical and research settings has revolutionized genomic medicine, enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions of genetic variants. However, this powerful technology introduces significant complexities in validation, quality control, and interpretation, necessitating robust guidelines from leading professional organizations. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) have each developed frameworks and recommendations to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and clinical utility of NGS testing.

Within the specific context of validating single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calls from NGS data, orthogonal confirmation with Sanger sequencing remains a critical consideration, despite advancements in NGS technology. This guide objectively compares the recommendations from these three key organizations, with a focused lens on the evidence and methodologies supporting the validation of variant calls, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for implementing these standards in their practice.

The table below summarizes the core focus, key documents, and applicability of the guidelines from the ACMG, CDC, and ASCP.

Table 1: Overview of Guidelines from ACMG, CDC, and ASCP

| Organization | Core Focus & Scope | Key Documents & Resources | Primary Audience & Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACMG | - Reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome/genome sequencing- Standards for interpretation of sequence variants- Clinical laboratory standards for NGS | - ACMG SF v3.2 for secondary findings [24]- Standards for variant interpretation [25]- ACMG clinical laboratory standards for NGS [25] | - Clinical laboratories- Geneticists- Focus on germline inherited disease and reporting |

| CDC (NGS Quality Initiative) | - Quality Management Systems (QMS) for NGS- Tools for CLIA compliance and method validation- Addressing personnel, equipment, and process management | - NGS Method Validation Plan & SOP [26]- Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators SOP [26]- Over 105 free customizable tools and resources [25] | - Public health and clinical laboratories- Wet and dry lab personnel and leadership- Broadly applicable regardless of platform or application |

| ASCP | - Continuing education and professional development- Practical, actionable learning for pathologists and lab professionals- Molecular pathology practice | - Workshops (e.g., "Genomics 101: Practical Information for Patient Care") [27]- Professional competency and training resources | - Pathologists and laboratory professionals- Focus on practical implementation and career enhancement |

Analytical Validation and Sanger Sequencing Concordance

A cornerstone of clinical NGS implementation is the analytical validation of the wet-lab and bioinformatics workflows. A critical question in this process, and central to our thesis on validating SNP calls, is the requirement for orthogonal confirmation of variants, typically by Sanger sequencing.

The Shift in Validation Paradigms

Historically, ACMG guidelines required orthogonal validation for all reported variants [4]. As NGS technologies have matured, this recommendation has been relaxed, allowing laboratories to define a confirmatory testing policy for high-quality variants that may not require Sanger confirmation [4]. This shift is supported by accumulating evidence showing high concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing.

Key Experimental Data on WGS and Sanger Concordance

A 2025 study published in Scientific Reports provides crucial quantitative data on this concordance, specifically for Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [4]. The researchers analyzed 1,756 WGS variants from 1,150 patients, with each variant validated by Sanger sequencing. The overall concordance was exceptionally high at 99.72% (only 5 mismatches). The study's goal was to establish quality thresholds to define "high-quality" variants that could be reported without Sanger validation, thereby reducing time and cost.

Table 2: Key Experimental Data from WGS-Sanger Concordance Study [4]

| Parameter | Study Findings | Implication for Validation Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | 99.72% (5/1756 variants unconfirmed) | Demonstrates the high inherent accuracy of WGS data. |

| Previously Suggested Thresholds | FILTER=PASS, QUAL ≥100, DP ≥20, AF ≥0.2: 100% sensitivity (all 5 unconfirmed variants filtered out), but low precision (2.4%) | These thresholds safely identify false positives but mandate Sanger validation for a large number of true variants. |

| Caller-Agnostic Thresholds (DP & AF) | DP ≥15 and AF ≥0.25: 100% sensitivity, precision increased to 6.0% | Effectively filters all false positives into "low-quality" bin while reducing the number of variants requiring validation by 2.5x. |

| Caller-Specific Threshold (QUAL) | QUAL ≥100: 100% sensitivity, precision of 23.8% | Drastically reduces variants requiring Sanger validation to only 1.2% of the initial set. Not directly transferable between bioinformatic pipelines. |

Application to Different Sequencing Methods

The study also applied the caller-agnostic thresholds (DP ≥15, AF ≥0.25) to a published panel/exome dataset [4]. The performance varied with the enrichment panel size, with best results for a hereditary deafness panel (96.7% sensitivity) and worse for an exome panel (75.0% sensitivity). This highlights that validation thresholds are context-dependent and must be established for specific assay types (e.g., panels, exomes, genomes) and wet-lab protocols.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

The guidelines provide concrete recommendations for the validation of NGS assays. The Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) joint consensus recommendation offers a detailed error-based approach for validating NGS oncology panels [28].

Sample Preparation and Assessment

- Microscopic Review: For solid tumors, a certified pathologist must review the sample to ensure the correct tumor type and sufficient non-necrotic tumor content. This often involves macrodissection or microdissection to enrich tumor fraction [28].

- Tumor Purity Estimation: The tumor cell fraction must be estimated, as it critically impacts the interpretation of mutant allele frequencies and copy number alterations. This estimation is correlated with sequencing results for verification [28].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Two major library preparation methods are used, each with implications for validation:

- Hybrid Capture-Based Methods: Use longer, biotinylated probes to capture regions of interest. Tolerate mismatches better, reducing the risk of allele dropout [28].

- Amplicon-Based Methods: Use PCR primers to amplify target regions. Can be susceptible to allele dropout from polymorphisms in primer binding sites [28].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Validation

The NGS Quality Initiative provides specific tools for this phase, including a "Bioinformatics Employee Training SOP" and a "Bioinformatician Competency Assessment SOP" [26]. The bioinformatics pipeline must be rigorously validated for its ability to accurately detect different variant types (SNVs, indels, CNAs, etc.) [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for NGS validation and the decision point for Sanger sequencing based on established quality thresholds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and tools essential for implementing NGS validation protocols as per the discussed guidelines.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Validation

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Relevant Context from Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Biotinylated Capture Probes | For hybrid capture-based library preparation; enriches target regions of interest for sequencing. | A major method for targeted NGS library preparation [28]. |

| Reference Cell Lines & Materials | Well-characterized controls for assay validation, optimization, and ongoing quality monitoring. | Recommended for establishing assay performance characteristics during validation [28]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Gold-standard orthogonal method for validating variants called by NGS. | Required for variants not meeting "high-quality" thresholds; used in concordance studies [4]. |

| NGS Method Validation Plan Template | A structured document outlining the scope, approach, and acceptance criteria for test validation. | A key resource provided by the CDC NGS QI to guide laboratories through CLIA-compliant validation [26]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines & Software | Tools for sequence alignment, variant calling, annotation, and filtration (e.g., using QUAL, DP, AF). | Critical for analysis; pipelines must be rigorously validated. Competency assessment is essential [26] [4]. |

| Key Performance Indicator (KPI) SOP | Standard procedure for monitoring ongoing quality of NGS testing (e.g., read metrics, QC rates). | A widely used document from the NGS QI for quality management and continuous monitoring [26]. |

The guidelines from ACMG, CDC, and ASCP, while differing in their primary focus, provide a complementary and comprehensive framework for ensuring the quality of NGS testing in clinical and public health domains. The ACMG offers critical standards for variant interpretation and reporting, the CDC's NGS QI delivers an extensive, practical toolkit for building a robust Quality Management System, and ASCP supports the ongoing education of the workforce implementing these technologies.

The decision to use Sanger sequencing for orthogonal confirmation is no longer a blanket requirement but a nuanced decision based on rigorous assay validation. As the experimental data shows, laboratories can define evidence-based, data-driven quality thresholds—such as read depth (DP ≥15), allele frequency (AF ≥0.25), and variant quality (QUAL ≥100)—to identify a subset of high-quality NGS variants that can be reported without confirmatory Sanger sequencing. This approach maintains the highest standards of accuracy while optimizing resource utilization, a balance crucial for both clinical diagnostics and efficient drug development.

A Step-by-Step Workflow for Validating NGS-Detected SNPs with Sanger Sequencing

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genetic analysis by enabling the simultaneous interrogation of millions of DNA fragments, providing unprecedented scale and speed for genomic studies [9]. Despite the advanced capabilities of NGS technologies, the confirmation of detected variants using Sanger sequencing remains a critical practice in many clinical and research settings to ensure the highest level of accuracy in genetic testing [29]. This practice is particularly important for variants that will inform clinical decision-making, therapeutic strategies, or patient care, where false positives could have significant consequences [28] [29]. However, the validation of all NGS variants with Sanger sequencing considerably increases the turnaround time and costs of clinical diagnosis, creating a need for strategic approaches to variant prioritization [30].

The prevailing concept in modern molecular diagnostics is that laboratories can establish quality thresholds for "high-quality" variants that may not require orthogonal validation, thereby optimizing resource allocation while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [4]. This approach recognizes that while Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for DNA sequence analysis due to its exceptional accuracy for short to medium reads, its application can be strategically targeted to variants that carry greater uncertainty or clinical importance [9] [31]. The development of evidence-based criteria for selecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for Sanger confirmation represents an essential component of efficient and reliable genomic analysis workflows in both research and clinical environments.

Analytical Frameworks for Variant Prioritization

Quality Metrics and Threshold Determination

The establishment of quality thresholds for designating "high-quality" variants that may not require Sanger confirmation is fundamental to efficient variant prioritization. Research indicates that specific quality parameters can effectively distinguish reliable variant calls from those needing confirmation. Based on validation studies comparing NGS and Sanger sequencing results, the following quality thresholds have demonstrated effectiveness for identifying high-quality variants:

- Depth of Coverage (DP) ≥ 20x: Adequate read depth at the variant position ensures sufficient sampling of the locus [30] [4].

- Variant Allele Frequency (AF) ≥ 20%: For heterozygous variants in pure samples, this threshold ensures the variant is represented in an appropriate fraction of reads [30] [4].

- Quality Score (QUAL) ≥ 100: This caller-dependent metric reflects the probability that a variant exists at that position [30] [4].

- Filter Status = PASS: Variants should pass all internal filter flags of the variant calling pipeline [30] [4].

Studies have demonstrated that variants meeting these strict quality thresholds show 100% concordance with Sanger sequencing results. One comprehensive analysis of 1,109 variants from 825 clinical exomes found no false-positive SNPs or indel variants among those classified as high-quality using similar parameters [30]. This suggests that Sanger sequencing, while invaluable as an internal quality control measure, adds limited value for verification of high-quality single-nucleotide and small insertion/deletion variants that meet established thresholds [30].

Context-Based Prioritization Criteria

Beyond technical quality metrics, certain variant characteristics and genomic contexts necessitate Sanger confirmation regardless of quality scores. These circumstances typically involve factors that potentially compromise variant calling accuracy or elevate clinical importance:

- Variants in clinically actionable genes: Any variant that will directly impact patient management decisions warrants confirmation [29].

- Variants with uncertain significance: Those requiring careful interpretation for potential clinical implications often benefit from orthogonal validation [28].

- Variants in complex genomic regions: Areas with high homology, repetitive sequences, or extreme GC content pose challenges for accurate variant calling [29].

- Variants with borderline quality metrics: Those approaching but not fully meeting high-quality thresholds should be prioritized for confirmation [4].

- Novel pathogenic variants: Previously unreported variants predicted to be pathogenic require confirmation before reporting [28].

- Variants from samples with low tumor purity or quality: Suboptimal samples introduce additional uncertainty in variant calling [28].

The specific application of these criteria may vary depending on the test's intended use, the clinical context, and laboratory-specific requirements. Professional guidelines emphasize the role of the laboratory director in implementing an error-based approach that identifies potential sources of errors throughout the analytical process and addresses these through test design, method validation, or quality controls [28].

Comparative Performance Data: NGS vs. Sanger Sequencing

Concordance Studies Across Sequencing Platforms

Multiple large-scale studies have systematically evaluated the concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing to validate the accuracy of variant calling and establish evidence-based thresholds for confirmation protocols. The findings from these studies provide critical insights into the reliability of NGS for different variant types and quality categories.

Table 1: Concordance Rates Between NGS and Sanger Sequencing in Major Validation Studies

| Study Scope | Sample Size | Variant Types | Overall Concordance | High-Quality Variant Concordance | Key Quality Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Exomes [30] | 825 exomes, 1,109 variants | SNVs, Indels, CNVs | 100% for high-quality variants | 100% | FILTER=PASS, QUAL≥100, DP≥20, AF≥0.2 |

| Whole Genome Sequencing [4] | 1,150 WGS, 1,756 variants | SNVs, Indels | 99.72% | 100% | QUAL≥100 or (DP≥15, AF≥0.25) |

| Forensic MT-DNA [32] | 17 samples | Mitochondrial variants | High concordance with additional heteroplasmy detection by NGS | N/A | Coverage >20x, variant frequency thresholds |

| Plant Population Genetics [33] | 3 populations, 9 SNPs | SNP allele frequencies | <4% average difference | Highly significant correlation | Coverage 55-284x |

The data consistently demonstrate that well-validated NGS assays can achieve exceptionally high concordance with Sanger sequencing, particularly when appropriate quality thresholds are applied. The study on clinical exomes concluded that Sanger sequencing may not be necessary as a verification method for high-quality single-nucleotide and small insertion/deletion variants, though it remains valuable as an internal quality control measure [30]. The slightly lower overall concordance in the WGS study (99.72%) can be attributed to the inclusion of lower-quality variants that would typically be filtered out or flagged for confirmation in clinical workflows [4].

Impact of Variable Thresholds on Validation Workflow Efficiency

The selection of specific quality thresholds directly influences the proportion of variants requiring Sanger confirmation, with significant implications for laboratory workflow efficiency and operational costs. Research has quantified how different threshold stringencies affect the variant confirmation burden.

Table 2: Impact of Quality Thresholds on Variant Confirmation Rates

| Threshold Criteria | Application Context | Variants Requiring Sanger Confirmation | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUAL ≥100 [4] | WGS (HaplotypeCaller) | 1.2% of initial variant set | 100% sensitivity, 23.8% precision |

| DP≥20, AF≥0.2 [30] [4] | Clinical Exomes | 2.4% precision (210/1109 variants) | 100% sensitivity |

| DP≥15, AF≥0.25 [4] | WGS | 4.8% of initial variant set | 100% sensitivity, 6.0% precision |

| Laboratory-established thresholds [30] | Clinical diagnostics | Variable by laboratory | Customized based on validation data |

These findings highlight the efficiency gains achievable through evidence-based threshold implementation. The WGS study noted that applying a QUAL ≥100 threshold reduced the number of variants requiring Sanger confirmation to just 1.2% of the initial set while maintaining 100% concordance for variants above this threshold [4]. This represents a substantial reduction in confirmation workload without compromising result accuracy. Similarly, the clinical exome study demonstrated that with appropriate quality thresholds, Sanger confirmation could be strategically targeted rather than universally applied [30].

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Methodological Framework for NGS-Sanger Concordance Studies

The establishment of reliable variant prioritization criteria requires carefully designed validation studies that directly compare NGS and Sanger sequencing results. The following methodological framework has been employed in major concordance studies:

Sample Selection and DNA Preparation

- Studies should include a representative set of samples spanning the expected quality spectrum encountered in routine testing [30] [4].

- DNA extraction should follow standardized protocols appropriate for the sample type (e.g., whole blood, tissue, amniotic fluid) [30] [32].

- DNA quantity and quality assessment should be performed using spectrophotometric or fluorometric methods [32].

NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library preparation should utilize established target enrichment methods (hybrid capture or amplicon-based) appropriate for the application [28].

- Sequencing should be performed on validated NGS platforms with sufficient average coverage (typically >100x for exomes, >30x for WGS) [30] [4].

- The sequencing run should include appropriate controls to monitor performance and detect potential contamination [32].

Variant Calling and Quality Filtering

- Bioinformatic analysis should align reads to an appropriate reference genome using standardized pipelines (e.g., BWA, GATK) [30] [34].

- Variant calling should be performed with established algorithms appropriate for the variant types of interest [28].

- Initial variant sets should be filtered using quality metrics (depth, allele fraction, quality scores) to categorize variants as high or low quality [30] [4].

Sanger Sequencing Validation

- Primers should be designed to amplify regions containing candidate variants, with careful attention to avoid common SNPs in primer binding sites [30].

- PCR amplification should be optimized for specificity and efficiency [29].

- Bidirectional Sanger sequencing should be performed using capillary electrophoresis instruments [30] [32].

- Sequence analysis should compare results to reference sequences to confirm variant presence/absence [32].

Concordance Assessment

- Variant calls from NGS and Sanger sequencing should be systematically compared [30] [4].

- Discrepancies should be investigated through repeat testing or alternative methods [30].

- Concordance rates should be calculated separately for high-quality and low-quality variant categories [30] [4].

This methodological framework provides the foundation for generating robust data on NGS accuracy and establishing laboratory-specific thresholds for Sanger confirmation.

Decision Workflow for Variant Confirmation

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for determining whether Sanger confirmation is required for specific variants identified through NGS analysis:

Diagram 1: Variant Prioritization Workflow for Sanger Confirmation. This workflow systematically evaluates variants based on quality metrics and clinical context to determine the need for Sanger confirmation.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of robust variant validation workflows requires specific laboratory reagents and materials that ensure the reliability and reproducibility of both NGS and Sanger sequencing processes. The following table details key components essential for conducting validation studies and routine confirmation protocols:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NGS Validation and Sanger Confirmation

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Preparation | TruSight One Panel, Clinical Exome Solution Panel, Precision ID Panels [30] [35] | Target enrichment for specific genomic regions | Panel design comprehensiveness, capture efficiency, uniformity of coverage |

| NGS Sequencing Reagents | Illumina NextSeq 500 reagents, Ion PGM/PGM SS Kit, Ion 530 Chip [30] [35] | Cluster generation and sequencing-by-synthesis | Read length, error rates, output capacity |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | BigDye Terminator Kit v1.1, ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer reagents [32] | Chain termination and fragment separation | Signal intensity, termination efficiency, resolution |

| DNA Amplification | PCR master mixes, specific primers for target regions [30] [29] | Target amplification for Sanger validation | Primer specificity, amplification efficiency, fidelity |

| Quality Control | EZ1 DNA Investigator Kit, QuantStudio systems, TaqMan assays [32] [35] | DNA quantification and quality assessment | Accuracy, sensitivity, dynamic range |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BWA, GATK, Ion Torrent Suite, Sophia Genetics pipeline [30] [34] | Read alignment, variant calling, and quality metric generation | Algorithm accuracy, parameter optimization |

These essential reagents form the foundation of reliable validation workflows. The selection of appropriate reagents should align with the specific technical requirements of the laboratory's sequencing platforms and the clinical or research applications. Regular quality control of these materials is essential for maintaining the accuracy and reproducibility of both NGS and Sanger sequencing results.

Strategic variant prioritization for Sanger confirmation represents an essential component of efficient and accurate genomic analysis in the NGS era. Evidence from multiple large-scale studies demonstrates that implementing quality-based thresholds for variant confirmation can significantly reduce unnecessary Sanger validation while maintaining the highest standards of accuracy. The criteria outlined in this review—incorporating both technical quality metrics and contextual considerations—provide a framework for laboratories to optimize their validation workflows.

As NGS technologies continue to evolve and demonstrate increasingly robust performance, the requirements for orthogonal confirmation will likely continue to diminish for certain variant categories. However, Sanger sequencing will remain indispensable for validating variants with suboptimal quality metrics, those located in challenging genomic regions, and those with significant clinical implications. Laboratories should establish their own validation policies based on comprehensive performance data, ensuring that variant confirmation protocols are both efficient and rigorously protective of patient care and research integrity.

Primer Design Best Practices for Robust PCR Amplification

In the context of validating single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calls from next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, robust PCR amplification is a critical first step for successful Sanger sequencing confirmation. Orthogonal validation by Sanger sequencing remains a common practice, with studies demonstrating high concordance rates—up to 99.72%—between NGS and Sanger sequencing for high-quality variants [4] [5]. The reliability of this process is fundamentally dependent on effective primer design, which ensures specific amplification of target sequences for downstream sequencing. This guide outlines the essential factors for designing primers that yield specific, efficient, and reliable amplification, directly impacting the accuracy of your NGS validation pipeline.

Core Principles of Primer Design

Successful primer design balances multiple interdependent parameters to achieve specificity and efficiency during the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The following criteria are widely recommended for standard PCR and sequencing applications.

Primer Length

Primer length is a primary determinant of specificity.

- Optimal Range: Most sources recommend primers between 18 and 30 nucleotides [36] [37] [38].

- Specificity vs. Efficiency: Shorter primers (e.g., 18-22 bases) anneal more efficiently but may lack specificity, while longer primers (>30 bases) can be less efficient during annealing and may exhibit slower hybridization rates [36] [39].

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. It directly determines the annealing temperature (Ta) of the PCR reaction.

- Optimal Tm: Aim for a Tm between 60°C and 75°C [37] [38].

- Primer-Pair Compatibility: The Tm of the forward and reverse primers should be within 1-5°C of each other to ensure synchronized binding to the target template [36] [38].

- Annealing Temperature: The optimal annealing temperature is typically 2-5°C below the Tm of the primers [36] [38].

GC Content

The proportion of Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) bases affects primer stability due to the three hydrogen bonds in a G-C base pair, compared to two in an A-T pair.

- Ideal Range: Maintain a GC content between 40% and 60%, with an ideal of around 50% [36] [39] [38].

- GC Clamp: Include a G or C base at the 3' end of the primer (a "GC clamp") to strengthen binding. However, avoid more than three consecutive G or C residues at the 3' end, as this can promote non-specific binding [39] [37] [40].

Avoiding Secondary Structures

Primers must be screened for sequences that can interfere with proper annealing.

- Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers: These occur when primers hybridize to themselves or to each other instead of the template DNA. The delta G (ΔG) of any dimer formation should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [38].

- Hairpins: Intramolecular base pairing can form hairpin loops. The parameter "self 3′-complementarity" should be kept low [36].

- Repetitive Sequences: Avoid runs of four or more identical bases (e.g., AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT), as they can misprime or form secondary structures [37] [40].

The relationship between these core principles and their impact on PCR success is summarized in the workflow below.

Comparative Analysis of Primer Design Guidelines

The table below synthesizes quantitative recommendations from multiple authoritative sources to provide a consolidated view of best practices.

Table 1: Consolidated Primer Design Parameters from Various Sources

| Parameter | General PCR Guidelines | Sanger Sequencing Guidelines | qPCR Probe Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-30 nucleotides [36] [37] [38] | 18-24 nucleotides [39] [40] | 15-30 nucleotides [36] [38] |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 60°C - 75°C [37] [38] | >50°C, <65°C [40] | 5°C - 10°C higher than primers [38] |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% [36] [38] | 45% - 55% [39] [40] | 35% - 60% [36] [38] |

| GC Clamp | 1-2 G/C residues at 3' end [37] | G/C residue at 3' end [40] | Avoid 'G' at 5' end [36] |

| Key Specificity Tip | Avoid runs of 4+ identical bases [37] | Avoid homopolymeric runs [40] | Screen for cross-homology [38] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: In Silico Primer Validation and Screening

Before ordering primers, perform comprehensive computational checks to minimize experimental failure.

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the target DNA sequence from a reliable database (e.g., NCBI RefSeq). For SNP validation, ensure the sequence context is accurate and check for nearby polymorphisms that might affect primer binding.

- Primer Design: Use automated tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST, IDT PrimerQuest) to generate candidate primer pairs. Set parameters to reflect the guidelines in Table 1.

- Specificity Check: Use the NCBI BLAST tool to ensure the primer sequences are unique to your intended target, minimizing the risk of amplifying off-target genomic regions [38] [41].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Analyze primers using tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer to check for hairpins and self-dimers. Ensure the ΔG values for any structures are above -9.0 kcal/mol [38].

- Tm Calculation: Use the nearest-neighbor method in the OligoAnalyzer tool with your specific PCR buffer conditions (e.g., 50 mM K+, 3 mM Mg2+) for a realistic Tm calculation [38].

Protocol: Empirical Primer Testing and PCR Optimization

After in silico validation, wet-lab testing is essential.

- PCR Setup: Prepare a standard PCR reaction mix containing your template DNA (e.g., 50-100 ng genomic DNA), forward and reverse primers (0.1-1 µM each), dNTPs, reaction buffer, and DNA polymerase.

- Gradient PCR: If amplification is inefficient or non-specific, perform a thermal gradient PCR to determine the optimal annealing temperature (Ta). Set the gradient around the calculated Tm of your primers (e.g., from 5°C below to 2°C above the Tm) [38].

- Product Analysis: Analyze PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. A single, sharp band at the expected amplicon size indicates specific amplification. Smearing or multiple bands suggest non-specific binding or primer-dimer formation, necessitating primer redesign or further optimization [41].

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify the PCR product and submit it for Sanger sequencing. Analyze the chromatogram to confirm the precise sequence of the amplicon, including the presence of the target SNP.

Supporting Data from NGS Validation Studies

Recent large-scale studies provide a data-driven rationale for applying stringent quality filters to NGS data before committing resources to Sanger validation. Implementing these filters can drastically reduce the number of variants requiring confirmation.

Table 2: Quality Thresholds for Filtering NGS Variants Before Sanger Validation

| Quality Parameter | Applied Threshold | Effect on Variant Set | Concordance with Sanger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage Depth (DP) | ≥ 15 [4] | Reduces number of variants needing validation | 100% concordance for variants meeting threshold [4] |

| Allele Frequency (AF) | ≥ 0.25 [4] | Significantly reduces validation pool | 100% concordance for variants meeting threshold [4] |

| Variant Quality (QUAL) | ≥ 100 [4] | Drastically reduces validation pool to ~1.2% of initial set [4] | 100% concordance for variants meeting threshold [4] |

| Combined Filter (DP+AF) | DP ≥ 15 and AF ≥ 0.25 [4] | Reduces validation pool with high precision [4] | All unconfirmed variants filtered out [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for PCR and Sanger Validation

| Item | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification; provides superior accuracy to minimize errors in the amplicon prior to sequencing. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for DNA synthesis during PCR. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST) | Free, web-based tool for designing and checking primer specificity against public databases [39] [41]. |

| Oligo Analysis Tool (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer) | Online tool for calculating precise melting temperatures and analyzing potential secondary structures like hairpins and dimers [38] [41]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard method for visualizing PCR products to confirm amplicon size, specificity, and yield before proceeding to sequencing. |

| Sanger Sequencing Service/Kit | The gold-standard method for orthogonal validation of NGS-derived variants, providing high-quality sequence data for a specific amplicon [4] [5]. |

Robust PCR amplification through meticulous primer design is a non-negotiable foundation for the reliable Sanger sequencing validation of NGS-derived SNPs. By adhering to the best practices outlined for primer length, Tm, GC content, and specificity, researchers can dramatically increase the efficiency and success rate of their validation workflows. Furthermore, integrating quality thresholds from NGS bioinformatics—such as coverage depth and allele frequency—allows for strategic selection of variants for confirmation, saving significant time and resources. As NGS technologies continue to mature, the principles of sound primer design remain a critical constant in ensuring genomic data accuracy.

Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for validating single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) discovered through next-generation sequencing (NGS), offering 99.99% base accuracy [42] [43]. This guide provides a detailed comparison between Sanger sequencing and NGS technologies, focusing on their respective roles in genomic research and variant confirmation. We present experimental protocols for executing Sanger sequencing reactions, from sample preparation through capillary electrophoresis, and provide supporting data on its performance in verifying NGS-derived SNP calls. By offering structured workflows, comparative performance tables, and reagent solutions, this article serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals requiring high-confidence validation of genetic variants.

In modern genomic research, a synergistic relationship exists between next-generation sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing. While NGS provides unprecedented throughput for discovering genetic variants across entire genomes or targeted regions, Sanger sequencing delivers the precision necessary for confirming these findings [44] [43]. This validation is particularly crucial in clinical diagnostics and drug development, where false positives can have significant implications. Sanger sequencing serves as an independent verification method for SNPs identified through NGS, ensuring the accuracy of reported variants [45] [10]. Its established protocols, cost-effectiveness for analyzing small numbers of targets, and ability to generate longer read lengths (typically 800-1000 base pairs) make it ideally suited for confirming variants in specific genomic regions of interest [42] [43].

The fundamental principle of Sanger sequencing, developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977, involves the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) during in vitro DNA replication [42] [46]. These ddNTPs lack a 3'-hydroxyl group, preventing further elongation of the DNA strand once incorporated. By using fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and separating the resulting DNA fragments by size, the sequence can be determined with high accuracy. This methodological robustness, combined with its straightforward workflow, maintains Sanger sequencing's relevance in contemporary genomic research, particularly for validating NGS findings [45].

Comparative Analysis: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS for SNP Validation

Performance Metrics and Applications

The selection between Sanger sequencing and NGS depends on research goals, scale, and required precision. For validating a limited number of SNP calls from NGS data, Sanger sequencing offers superior accuracy and cost-effectiveness, while NGS excels at comprehensive variant discovery across multiple genomic regions.

Table 1: Key Technical Comparisons Between Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 99.99% base accuracy [42] | High, but varies by platform and depth |

| Throughput | Low; sequences one fragment at a time [44] | High; massively parallel, sequencing millions of fragments simultaneously [44] |

| Read Length | 800-1000 bp [42] [43] | Varies by platform; typically shorter (e.g., 50-300 bp for Illumina) [42] |

| Cost-effectiveness | Ideal for 1-20 targets [44] [10] | Cost-effective for high-volume sequencing [44] |

| Variant Detection Sensitivity | ~15-20% limit of detection [44] | Can detect variants at frequencies as low as 1% [44] [10] |

| Primary Application in Validation | Confirmatory testing for known variants and NGS results [45] [43] | Discovery-based screening for novel variants [44] [10] |

| Turnaround Time | ~5 hours for a single run [45] | 1 day to 1 week, depending on throughput [45] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Relatively straightforward [42] [43] | Complex, requiring sophisticated bioinformatics [42] [43] |

Experimental Data Supporting Sanger for NGS Validation

Studies directly comparing variant calls between Sanger sequencing and NGS demonstrate their complementary roles. Sanger sequencing consistently provides high-confidence validation for SNPs initially identified by NGS, particularly for clinical applications where accuracy is paramount [43]. A comparative analysis of computational tools for Sanger sequencing analysis (TIDE, ICE, DECODR, and SeqScreener) demonstrated that these tools could estimate indel frequency with acceptable accuracy when indels were simple and contained only a few base changes, with DECODR providing the most accurate estimations for most samples [47]. This highlights the importance of analytical tool selection when using Sanger sequencing to validate NGS-based variant calls.

For specialized applications like knock-in efficiency estimation, TIDE-based TIDER outperformed other computational tools, indicating that the optimal validation approach may depend on the specific type of genome editing being performed [47]. The 15-20% detection limit of Sanger sequencing makes it well-suited for confirming heterozygous variants expected to be present at approximately 50% frequency in diploid organisms, but less ideal for detecting low-frequency mosaicism or somatic mutations present in only a subset of cells [44] [43].

Sanger Sequencing Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

The Sanger sequencing method consists of six fundamental steps that transform raw DNA samples into readable sequence data. The following workflow diagram illustrates this complete process:

DNA Template Preparation

The initial quality of DNA significantly impacts sequencing success. Optimal template preparation varies by source material:

- Plasmid DNA: Extract using alkaline lysis methods followed by phenol-chloroform purification or commercial silica column-based kits. Require high purity with OD260/OD280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 [48].

- PCR Products: Purify using spin columns, ethanol/EDTA precipitation, or enzymatic treatment to remove excess primers and nucleotides. Recommended concentration: 10-50 ng/μL with OD260/OD280 ≈ 1.8 [48] [46].

- Genomic DNA: Extract from tissues, blood, or cells using organic extraction (phenol-chloroform), silica columns, or magnetic beads. Require intact, non-degraded DNA with OD260/OD280 of 1.8-2.0 at 50-100 ng/μL concentration [48].

- cDNA: Synthesize from high-quality RNA using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) or random primers. Ensure RNA integrity prior to reverse transcription [48].

PCR and Sequencing Primer Design

Effective primer design is critical for successful sequencing:

- Length: 18-25 bases for optimal specificity and binding [48].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Calculate using Tm = 4×(G+C) + 2×(A+T). Design primers with Tm of 50-65°C, with annealing temperature typically 2-5°C below Tm [48].

- Specificity: Avoid secondary structures, primer dimers, and repetitive sequences. Ensure 3' end stability but avoid stretches of identical bases [48].

- Position: Bind upstream of the target region with an area of known sequence proximity [46].

PCR Amplification and Clean-up

Amplify the target region using:

- Reaction Composition: Template DNA, forward and reverse primers, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffer [46].

- Thermal Cycling: Initial denaturation (94-96°C for 2-5 min), followed by 25-35 cycles of denaturation (94-96°C for 30 sec), annealing (Tm-specific for 30 sec), and extension (60-72°C for 1 min/kb), with final hold at 4°C [48].

- Clean-up: Remove unincorporated primers using spin columns, ethanol/EDTA precipitation, or enzymatic treatment to prevent interference in subsequent sequencing reactions [46].

Cycle Sequencing Reaction

The core sequencing step utilizes:

- Reaction Composition: PCR product (10-50 ng), single sequencing primer (3:1 to 10:1 molar ratio to template), DNA polymerase (0.5-1U per 10μL reaction), buffer, dNTPs, and fluorescently labeled ddNTPs [48] [46].

- Termination Chemistry: Four ddNTPs (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, ddTTP), each labeled with a distinct fluorescent dye, randomly incorporate during synthesis to terminate chain elongation [42] [46].

- Thermal Cycling: Similar to PCR but with only one primer, generating DNA fragments of varying lengths that terminate with fluorescent ddNTPs [46].

Sequencing Clean-up and Capillary Electrophoresis